Abstract

This study systematically investigated the electrorheological (ER) behavior of four aqueous smectite clay dispersions—fluorinated hectorite (Ht-F), stevensite (Stv), hectorite (Ht), and saponite (Sap)—with emphasis on transparency, rheological responses, and interparticle interactions. Optical observations revealed that the transparency of the aqueous dispersions followed the order Ht-F > Stv > Ht > Sap, which corresponded well to the finer network structures previously observed in Cryo-SEM images. Whereas micrometer-sized poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) dispersions exhibited electrically induced rapid and reversible separation (ERS) due to sedimentation, the nanosized clays, which do not settle, developed ER effects through field-driven flocculation and subsequent network formation. Under low-frequency AC fields, Ht-F showed highly reversible responses similar to Stv, whereas Sap exhibited irreversible stress increases, accompanied by suspected ion release under the field. Dynamic rheological measurements showed that application of electric fields enhanced the loss modulus (G″) more prominently than the storage modulus (G′), clearly indicating a strengthening of viscous behavior. Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek theory (DLVO) potential analysis yielded a barrier-height sequence (Stv < Ht-F < Ht < Sap) that directly paralleled the order of ER responsiveness. These results demonstrate that the ER hierarchy of aqueous smectites can be rationalized by DLVO interactions and provide design guidelines for environmentally compatible ER fluids.

1. Introduction

Research on controlling the rheology of materials by external electric fields has been extensively conducted over the past several decades. The most widely recognized phenomenon in this context is the reversible increase in viscosity and elasticity upon application of a strong electric field, known as the electrorheological (ER) effect. Since the pioneering report by Winslow [1], the most common ER fluids have been systems in which fine particles are dispersed in highly insulating oils, such as silicone or mineral oils [2,3,4]. In such dispersions, when the electric field strength reaches several hundred V/mm to several kV/mm, the suspended particles undergo dielectric polarization, forming induced dipoles that align along the field direction. These dipoles assemble into chain- or column-like aggregates, often referred to as fibrous columns [5]. The columns bridge across the electrodes, leading to a sudden and dramatic increase in flow resistance, whereby the apparent viscosity and yield stress can rise by several orders of magnitude. Once the electric field is removed, these structures rapidly collapse, and the dispersion returns to its initial state. This process is both rapid and reversible, with typical response times on the order of 1–100 ms [6]. Because ER fluids enable instantaneous and reversible control of flow resistance by an applied electric field, a wide range of industrial applications has been explored. Representative examples include active shock absorbers and engine mounts with tunable damping properties [7], clutches, brakes, and control valves that regulate torque or flow electrically [8], and medical devices such as actuators and artificial joints [9].

Smectites are a family of layered silicate minerals that include montmorillonite and hectorite and are characterized by their ability to retain exchangeable cations in the interlayer spaces. In aqueous media, the layered structure delaminates to form primary nanosheet particles, which exhibit strong hydrophilicity, high cation exchange capacity (CEC), and flexible sheet-like morphology. Owing to these properties, smectites show distinctive rheological behavior and have been widely studied as representative colloidal particles. Smectite-based clay aqueous dispersions exhibit both quantitative rheological changes, such as variations in viscosity and yield stress, and qualitative changes, such as sol–gel transitions, depending on clay volume fraction and electrolyte concentration [10]. At sufficiently high clay volume fractions, dispersions remain in a sol state under low-salt conditions but undergo gelation at higher salt concentrations. Under all experimental conditions of this study, the dispersions were alkaline (pH 7.6–8.9) [11], and the edges of the clay nanosheets were negatively charged [12]. The permanent charges on the basal faces were also negative, rendering the entire disk surface negatively charged. Consequently, the rheological properties of these dispersions are governed by the balance between attractive van der Waals (London dispersion) forces and electrostatic repulsion between particles [13,14]. Our group has previously demonstrated that deionized dispersions of hectorite (Ht) and stevensite (Stv) exhibit clear electrorheological (ER) effects [15,16,17,18]. In this study, the term “deionized clay dispersion” refers to a hectorite aqueous dispersion in which soluble ions have been removed using an ion-exchange resin, resulting in an extremely low ionic strength. Compared with general non-aqueous systems, the clay-based ER fluids offer distinct advantages such as safety (low toxicity) and environmental compatibility, making them attractive candidates for biomedical and engineering applications. Clay minerals are widely recognized as environmentally friendly and low-toxicity inorganic materials and have been extensively used as adsorbents and environmental protection materials [19,20]. Recent review articles have further highlighted the growing interest in developing electrorheological (ER) and other smart fluids based on materials with low environmental impact and high biocompatibility [4,21]. These aqueous systems can be activated by remarkably low electric fields, on the order of only a few V/mm, in contrast to conventional nonaqueous ER fluids. Upon field application, clays are believed to undergo flocculation and simultaneously assemble into three-dimensional network structures. Since the manifestation of the ER effect requires deionization of the dispersion, it is evident that the electrical double layer (EDL) surrounding the clay particles plays a central role in the mechanism. The electrical double layer (EDL) surrounding smectite clay particles plays a central role not only in colloid and materials science but also in subsurface engineering. In particular, clay swelling, ion exchange, and dispersion stability—phenomena governed by the EDL—directly influence wellbore instability, formation damage, and fluid transport within shale reservoirs [22]. Deionized smectite dispersions exhibit viscoelastic changes under applied electric fields, offering significant potential as functional materials because their flow properties can be reversibly controlled in response to external stimuli. Rheological evaluation of field-induced flocculation and network formation provides critical insights not only for designing electrically responsive viscoelastic materials but also for applications in transport and separation processes, flow control in microchannels, environmentally compatible ER devices, and soft actuators. Therefore, quantifying the time dependence of viscosity and moduli during and after field application is essential for elucidating the response mechanisms and potential applications of clay-based ER fluids.

Interestingly, when aqueous dispersions of other micron-sized particles are subjected to electric fields of comparable strength (on the order of a few V/mm), their sedimentation or flotation velocities increase markedly depending on particle density, leading to rapid separation of particles from the medium [23,24,25,26,27,28]. After separation, gentle stirring readily restores the original dispersion. We refer to this reversible phenomenon as the electrically induced rapid/reversible separation (ERS) effect. As noted above, when comparable electric fields are applied to aqueous dispersions of nanosized clay particles, the response is not particle sedimentation or flotation but rather an increase in the viscosity of the dispersion. By contrast, the electrocoagulation (EC) effect, widely used in wastewater treatment [29,30,31,32,33], is fundamentally different from ERS. EC arises under DC fields in electrolysis cells with sacrificial metal electrodes (e.g., Fe or Al), where metal ions are released into solution, making the process irreversible. Our group has previously investigated the ERS effect for a range of micron-sized particles in water, including polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) [23,24], silica [25], and aluminosilicate-based hollow particles [26,27]. The ERS effect is most pronounced under deionized or low-electrolyte conditions, again highlighting the critical role of the electrical double layer (EDL) surrounding the particles. It is clear that this effect originates from floc formation among micron-sized particles under external fields. Another notable feature is its strong dependence on the field orientation [28]. When the field is tilted relative to the horizontal (θ = 0°), floc formation occurs below a critical angle θ* (≈30°), whereas above θ*, field-induced convection dominates, resulting in enhanced dispersion stability. The critical angle varies with field strength and other conditions. The ER effect in clay dispersions and the ERS effect in micron-sized particle dispersions thus share a common mechanistic basis: reversible modulation of particle dispersion states in response to field application and removal. In both cases, floc formation is involved; however, the much smaller size of primary clay particles (tens of nanometers) prevents sedimentation or flotation, enabling them to form three-dimensional networks upon flocculation and thereby exhibit ER effects. In contrast, micron-sized particles undergo size-dependent sedimentation or flotation during floc growth, leading to the manifestation of ERS effects.

The first aqueous ER fluid based on smectite clays was reported by our group using deionized hectorite (Ht) dispersions [15]. Under DC fields, the apparent viscosity increased with increasing field strength. When the field was switched off, the viscosity decreased but did not fully return to its original value. By contrast, under extremely low-frequency AC fields, the apparent viscosity varied with field strength, and stress recovery upon field removal was dramatically improved [16]. Subsequent studies revealed that the stress response depends strongly on the type of clay [17] as well as the waveform of the applied field [18]. Specifically, stevensite (Stv) dispersions exhibited superior reversibility of stress responses compared with Ht dispersions. Stv particles are smaller than Ht particles [11], and at the same clay volume fraction and electrolyte concentration, Stv dispersions—including those forming physical gels—are more transparent than Ht dispersions [34]. This suggests that the three-dimensional networks formed by Stv possess a higher density of physical crosslinks and a finer structural framework. Taken together, these findings imply that clay dispersions forming more transparent physical gels tend to exhibit improved reversibility of stress responses to field on–off cycling. In addition to Ht and Stv, our group has employed saponite (Sap) and fluorinated hectorite (Ht-F) as representative smectites. Although these clays all belong to the smectite family, they differ systematically in several structural and chemical characteristics, including primary particle size, cation exchange capacity (CEC), the origin of layer charge (octahedral vs. tetrahedral), and the presence or absence of F-substitution of terminal OH groups. Such differences directly influence the thickness of the electrical double layer formed in water, the zeta potential, the stability of the dispersion, and the degree of network development, ultimately giving rise to a clear hierarchy in their DLVO potential barriers. Accordingly, using these four smectites enables a systematic evaluation of the relationship between ER responsiveness and DLVO interactions, allowing the origin of the ER response hierarchy to be elucidated. In this study, we investigated the ER behavior of Ht-F and Sap aqueous dispersions for the first time and examined their stress–response characteristics under AC electric fields. Building on previous findings for stevensite (Stv) and hectorite (Ht), our objective was to clarify the relationship between the stress responsiveness of these four smectite dispersions and their corresponding DLVO potential barriers.

2. Experimental

2.1. Sample Preparation

Four types of synthetic smectite clays were used: fluorinated hectorite (Ht-F) and saponite (Sap), both supplied by Kunimine Industries Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), together with stevensite (Stv) and hectorite (Ht) for comparison. Their chemical compositions are as follows:

Ht-F: Na0.33(Mg2.67Li0.33)Si4O10(F,OH)2

Stv: Na0.16Mg2.92Si4O10(OH)2

Ht: Na0.33(Mg2.67Li0.33)Si4O10(OH)2

Sap: Na0.33Mg3(Si3.67Al0.33)O10(OH)2

All clays used in this study were lamellar in morphology. Ht-F is a variant of hectorite in which approximately 50% of the OH groups at the nanosheet edges are substituted by fluorine atoms. The particle sizes of Ht-F, Stv, Ht, and Sap were 40, 46, 79, and 108 nm, respectively, with a uniform single-layer thickness of 1 nm [11]. They are listed in order of increasing particle size. The density of all clays was 2.5 g/cm3. When estimated by assuming an ideal “single-layer nanosheet” (a thin disk), all clays exhibit a high specific surface area on the order of ~800 m2/g. Although specific surface area was not used in the calculation of the DLVO curves, this large surface area is an important factor because it enhances the effects associated with the electrical double layer. The cation exchange capacities (CEC) of Ht-F, Stv, Ht, and Sap are 70, 32, 49, and 70 meq/100 g, respectively, and their zeta potentials ζ are −54, −45, −48, and −45 mV, respectively [11]. The particle size and zeta potential of the clay samples were measured at different times during the course of the study, and therefore each measurement was performed using the most suitable instrument available at that time. The four smectite clays used in this study differ in the origin of their layer charges. Ht-F, Stv, and Ht possess octahedrally derived layer charges arising from the isomorphic substitution of Mg by Li within the octahedral sheet, whereas Sap carries a tetrahedrally derived layer charge resulting from the isomorphic substitution of Si by Al in the tetrahedral sheet.

Each clay was carefully dispersed in ultrapure water (Milli-Q Advantage A10, Millipore Co., Burlington, MA, USA), after which an ion-exchange resin (AG501-X8 (D), Bio-Rad Lab., Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) was added at approximately one-eighth of the total dispersion volume. After deionization for more than three months, the stock suspensions were obtained, with initial clay volume fractions of φ = 0.018–0.019. For rheological and transmittance measurements, the suspensions were diluted with ultrapure water to φ = 0.001. Smectite clay dispersions require an aging period for properties such as zeta potential and rheology to approach quasi-equilibrium [35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. After sample preparation, dispersions were allowed to stand for more than one day, and rheological measurements were carried out within one week. For macroscopic observations, dispersions were adjusted to φ = 0.01. To compare transmittance changes under electric fields, aqueous dispersions of monodisperse polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) particles (Sekisui Plastics Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) were also used. The PMMA particles had a diameter of 4.8 μm, density of 1.2 g/cm3, and zeta potential of −26 mV. For the PMMA particles, a laser diffraction particle-size analyzer and a zeta-potential analyzer available at the time of measurement were used. Stock suspensions were prepared by deionization for more than ten years using the same ion-exchange resin, and then diluted with ultrapure water to φ = 0.001. For transmittance measurements of Ht dispersions, φ was likewise adjusted to 0.001. All experiments in this study were conducted at 25 °C.

2.2. Particle Size and Zeta Potential Measurements

The particle sizes of the clays were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a nanoPartica SZ-100 Z2 (HORIBA, Kyoto, Japan) [11]. Each sample was diluted with distilled water to a clay concentration of 0.05 wt% and subjected to ultrasonic treatment at 40 kHz for 5 min prior to measurement. The measurements were conducted at a scattering angle of 90°, using a built-in 10 mW, 532 nm diode-pumped frequency-doubled laser as the light source. Cumulant analysis of the obtained correlation functions was used to determine the cumulant-averaged particle size. Each sample was measured three times, and the average values are reported. The zeta potentials ζ of the clays were measured using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, UK) in order to construct Derjaguin–Landau–Verwey–Overbeek (DLVO) potential curves. The volume fraction of the samples was φ = 0.001, and all dispersions were deionized. The particle size and zeta potential of PMMA were measured with a DLS-700 (Otsuka Electronics Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and an ELSZ 2000 (Otsuka Electronics Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan), respectively. Each measurement was repeated at least three times, and the average values are reported. The PMMA dispersions were prepared at a volume fraction of φ = 0.0005 and deionized prior to use.

2.3. Transmittance Measurements and Macroscopic Observations

Transmittance measurements were performed using a DU650 spectrophotometer (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA). Quartz cuvettes (Type F15-SQ-10, GL Sciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan) with a path length of 10 mm were used, in which platinum electrodes were placed in parallel with an interelectrode distance of 9.8 mm. A volume of 2.5 mL of sample dispersion was introduced into the cuvette, which was sealed with Parafilm to prevent contamination by airborne ions. After gentle mixing, the cuvette was set in the instrument, and approximately 30 s later, an electric field was applied and measurements were initiated immediately. The observation point was located 10 mm below the liquid surface and at the midplane between the electrodes. A light beam at 540 nm with a diameter of 2.0 mm was perpendicularly irradiated through the quartz cuvette. A function generator (FG110, Yokogawa Test & Measurement Co., Tokyo, Japan) was used to apply DC fields of E = 0.3 and 1.0 V/mm to the dispersions. For macroscopic observations, deionized clay dispersions were transferred into rectangular quartz cuvettes (10 mm × 10 mm × 45 mm) at 3.0 mL per cell using a micropipette. The cells were sealed with Parafilm to prevent drying, and a reference cell covered with white tape was placed adjacent to the samples. Images were captured under uniform white illumination from above using a digital single-lens reflex camera (DS126441, Canon Co., Tokyo, Japan). In addition to spectrophotometric transmittance, the apparent transparency of the dispersions was evaluated by calculating brightness ratios from captured images. The brightness ratio was defined as a relative index, with pure water taken as 100% and an opaque reference as 0%. While transmittance provides point information dominated by primary scattering near the optical path, brightness ratios reflect overall image-based information, including multiple scattering and turbidity, making them suitable for side-by-side comparison of multiple clay dispersions under identical imaging conditions. The images were analyzed with ImageJ 1.53 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) to quantify brightness values. To observe the inner-cylinder (positive electrode) surface after field application, dispersions were placed in the rheometer cell described below and subjected to an electric field for 2000 s under quiescent conditions. A DC field (E = 8.0 V/mm) or an AC field (effective strength Erms = 8.0 V/mm) was applied. After field removal, the inner cylinder was carefully taken out and photographed with a digital camera.

2.4. Rheological Measurements

Rheological measurements were performed using a double-cylinder rotational rheometer (Rheosol-G2000W-GF, UBM Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) in which both the inner and outer cylinders were made of stainless steel and simultaneously served as electrodes. The system was modified to allow the application of electric fields to the sample via the function generator described above. Steady shear flow and dynamic oscillatory deformations were imposed by rotation or oscillation of the outer cylinder, while torque was detected through the rotation of the inner cylinder connected to a torsion wire. The gap between the inner and outer cylinders was set to either 0.35 or 0.5 mm, depending on the experiment. Flow curves were obtained over a shear-rate range of

= 0.02–120 s−1. For monitoring the time dependence of shear stress, σ, the shear rate was fixed at

= 19 s−1. In dynamic rheological tests, the strain amplitude was set to γ = 0.1 and the angular frequency to

= 0.63 rad s−1. The strain amplitude was selected after confirming that it fell within the linear viscoelastic region (LVE) for all samples [11]. The angular frequency was chosen within the range used in our previous study (0.13–6.3 rad/s) [11], where the torque response of the instrument and the reproducibility of the measurements were most stable. Changes in the storage modulus G’ and loss modulus G” in response to field application and removal were recorded. For flow-curve and dynamic viscoelastic measurements, the maximum applied DC field strength was E = 8.0 V/mm. Under AC fields, both the field-strength dependence (up to an effective maximum of Erms = 20 V/mm) and frequency dependence (up to fE = 10 Hz) were examined. All measurements were performed on freshly prepared samples with no prior electric-field history. Before each measurement, all samples were subjected to a pre-shear at

for 60 s, followed by a 60 s rest period to allow equilibration under field-free conditions.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Transmittance Measurements and Macroscopic Observations

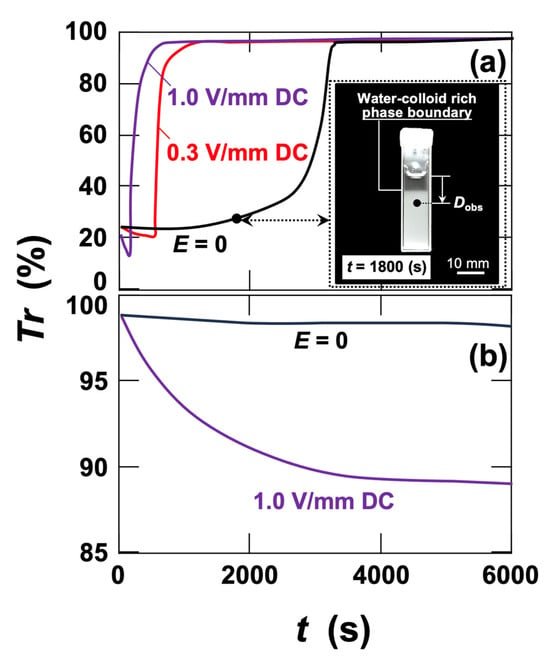

The transmittance of the PMMA particle dispersion (particle diameter: 4.8 µm) was measured for comparison with the clay dispersions (Figure 1a). This is because micron-sized dispersed particles exhibit the electrically induced rapid and reversible separation (ERS) effect under the same field conditions, as reported previously [23,24,25,26,27,28]. In the absence of an electric field, sedimentation of the particles produced a distinct boundary between the aqueous phase and a colloid-rich phase (inset of Figure 1a, taken at t = 1800 s). When this boundary passed through the observation point, a sharp change in transmittance was recorded. By comparing the time evolution of transmitted light intensity at different depths, the time lag of the intensity jump relative to the distance between observation points allowed the descent velocity of the boundary to be determined [24,25,28]. Under field-free conditions, the descent velocity of the boundary was nearly identical to the sedimentation velocity of individual PMMA particles calculated from Stokes’ law. Thus, the descent velocity reflects the settling velocity of either individual PMMA particles or PMMA flocs, and the same approach is applicable under applied fields. In this study, transmittance changes were monitored at a single observation point. Under DC fields, sharp increases in transmitted intensity occurred at earlier times, indicating accelerated settling due to floc formation of the PMMA particles. In contrast, no abrupt increase in transmitted intensity was observed in clay dispersions under field-free conditions (Figure 1b). This indicates that the nanosized clay particles do not undergo measurable sedimentation within the experimental time window. When a DC field of E = 1.0 V/mm was applied, the transmitted intensity gradually decreased from the beginning of measurement and reached a quasi-equilibrium level of approximately 89%. This behavior strongly suggests that clays form flocs under the electric field, leading to enhanced Mie scattering. As noted earlier, micron-sized silica particles, as well as micron-sized montmorillonite—despite also belonging to the smectite family—form flocs under applied electric fields and exhibit the ERS effect in a manner similar to PMMA [23,24,25,26,27,28]. At present, the mechanism of such field-induced floc formation remains unclear. What is important in the context of this study is that, because clay particles are nanosized, aqueous clay dispersions do not exhibit the ERS effect under DC fields. Instead, they remain homogeneously dispersed while developing the ER effect described later.

Figure 1.

Changes in transmittance (Tr) of aqueous dispersions of (a) poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) particles and (b) hectorite (Ht) under applied electric fields at 25 °C. The particle volume fraction was φ = 0.001. The observation position (Dobs) was set 10 mm below the liquid surface at the center between the electrodes.

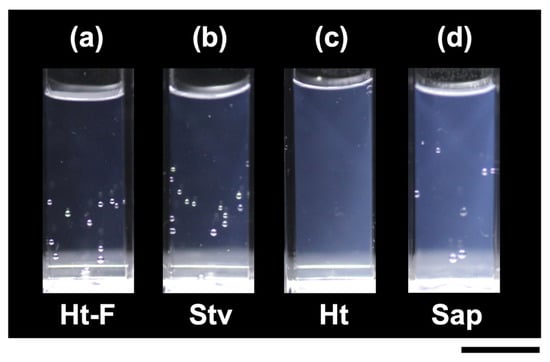

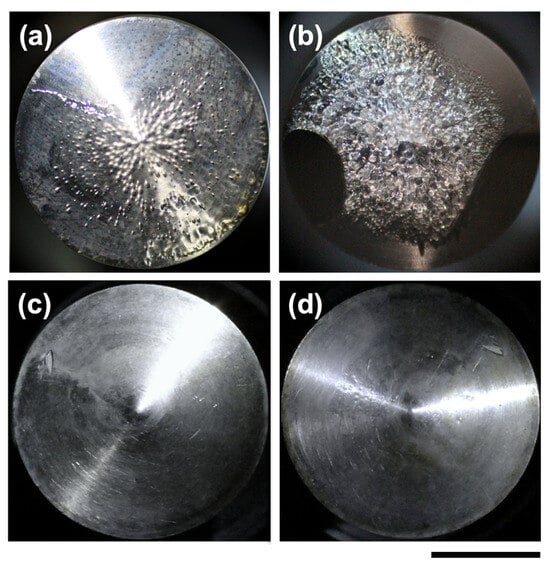

The appearances of the four clay dispersions were compared (Figure 2). Among the four dispersions, Ht-F exhibited the highest transparency (Figure 2a), followed by Stv (Figure 2b), whereas Sap (Figure 2d) was the most turbid. In our previous study [11], we concluded that differences in the zeta potential of clays in water significantly influence their aggregation state. The sequence of brightness ratios was as follows:

Ht-F (83%) > Stv (79%) > Ht (62%) > Sap (56%).

Figure 2.

Appearance of deionized clay aqueous dispersions at 25 °C. Clay volume fraction φ = 0.01. Scale bar = 10 mm. (a) Fluorinated hectorite (Ht-F), gel region; (b) stevensite (Stv), gel region; (c) hectorite (Ht), near the sol–gel transition region; (d) saponite (Sap), near the sol–gel transition region.

This sequence was consistent with the order of particle sizes. According to our previous Cryo-SEM observations [34], the skeleton thicknesses of the three-dimensional networks formed by clays under field-free conditions (at φ = 0.01, deionized) followed the sequence:

Ht-F ≈ Stv (0.35 µm) > Ht (0.48 µm) > Sap (0.63 µm).

This finding suggests that Ht-F forms a finer network in water with a greater number of physical crosslinking points, whereas Sap forms a rougher network with fewer crosslinking points. At lower volume fractions (φ), network structures are not formed and the dispersions remain in a sol state. Notably, the sequence of transmittance in these sol-state dispersions was confirmed to be the same as described above.

3.2. Rheological Measurements

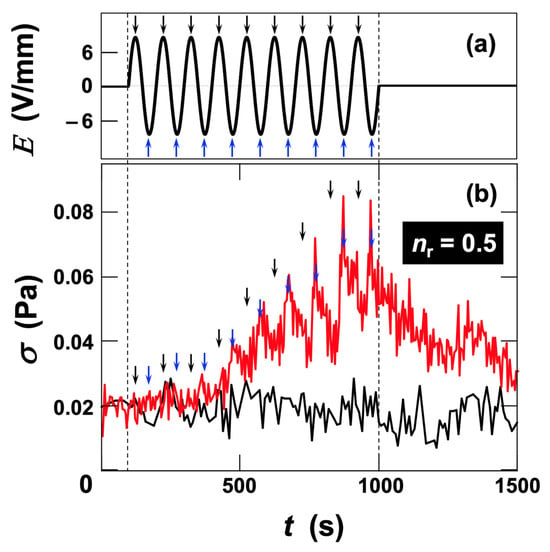

3.2.1. Stress Response of Ht-F Dispersions to AC Electric Fields

Although the rheological behavior of ultrapure water under electric fields was not independently measured in this study, our previous work demonstrated that water does not exhibit any viscosity change in response to applied electric fields [15]. In that study, no change in viscosity was detected even when a DC field of 6.0 V/mm was applied to ultrapure water, confirming that water does not show any ER response. When no viscosity change is observed under a DC field, it is physically reasonable that the viscosity of water remains unchanged under AC fields, because the alternating field direction further cancels any potential effect in a time-averaged manner. First, we focused on the stress response of the dispersion upon application and removal of an AC electric field at an effective field strength of Erms = 6.0 V/mm (Figure 3). In Figure 3, the maxima of the electric field are indicated by black arrows, and the minima (negative maxima) by blue arrows. After several hundred seconds from the onset of field application, stress variations synchronized with the electric field began to appear, although the amplitude of fluctuation was initially small. As time progressed, both the amplitude of stress variation and the median value of stress (midpoint between maximum and minimum) increased, approaching a steady level. Upon field removal, σ returned close to its initial value. The stress maxima appeared to lag significantly behind the positive field maxima, whereas no pronounced peaks corresponding to the negative field maxima were observed. Notably, shoulders following the stress maxima were evident, suggesting that the peaks corresponding to negative maxima were smaller and merged into a single maximum because of slower recovery of stress from the positive maxima. This polarity-dependent, asymmetric stress response indicates the involvement of electrokinetic effects such as electrophoresis. The ratio

, defined as the number of stress maxima () relative to the total number of electric-field maxima and minima (), was 0.5 in this regime. The fact that

was 0.5 rather than 1 corresponds to the absence of observable stress peaks at the electric-field minima.

Figure 3.

Time evolution of shear stress in deionized fluorinated hectorite (Ht-F) aqueous dispersion during application and removal of an AC electric field at 25 °C. Clay volume fraction φ = 0.001, shear rate

= 19 s−1. (a) Time variation in electric field strength. Field frequency fE = 0.01 Hz, effective field strength Erms = 6.0 V/mm. (b) Time variation in shear stress. Black line: without field; red line: under applied AC field. Black arrows denote the electric-field maxima, and blue arrows denote the minima. The same arrows are also shown near the shear stress maxima.

is the ratio of the total number of electric field maxima and minima () to the number of shear stress maxima (), i.e.,

=

/

.

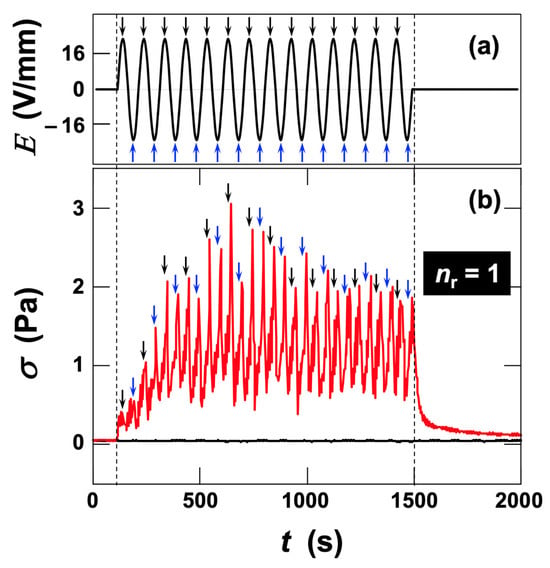

At a higher field strength of Erms = 16 V/mm, stress changes appeared immediately after field application (Figure 4). With increasing application time, both the amplitude of stress fluctuations and the median stress increased, reaching a steady value at approximately t = 500 s. Upon field removal, σ again returned close to its original value. Unlike the case at Erms = 6.0 V/mm, stress maxima corresponding to both the electric-field maxima and minima were observed, yielding

. This indicates that σ varied consistently with the electric field and followed the field changes more rapidly.

Figure 4.

Time evolution of shear stress in deionized fluorinated hectorite (Ht-F) aqueous dispersion during application and removal of an AC electric field at 25 °C. Clay volume fraction φ = 0.001, shear rate

= 19 s−1. (a) Time variation in electric field strength. Field frequency fE = 0.01 Hz, effective field strength Erms = 16 V/mm. (b) Time variation in shear stress. Black line: without field; red line: under applied AC field. Black arrows denote the electric-field maxima, and blue arrows denote the minima. The same arrows are also shown near the shear stress maxima.

is the ratio of the total number of electric field maxima and minima () to the number of shear stress maxima (), i.e.,

=

/

.

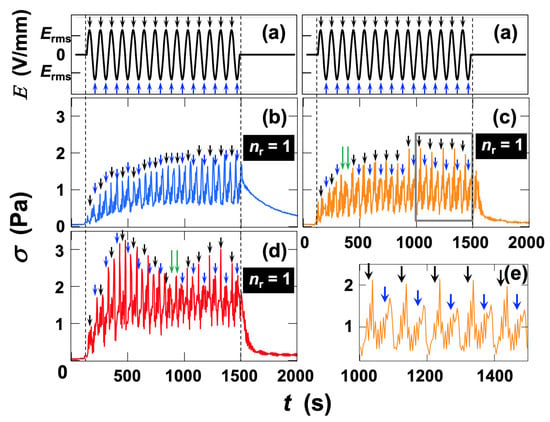

The field-strength dependence of the stress response of Ht-F dispersions was then examined at fE = 0.01 Hz in the higher-field region (Erms

8.0 V/mm) (Figure 5). In this region, the

value was consistently 1, independent of Erms. At Erms = 8.0 V/mm (Figure 5b), the median stress required approximately 1000 s to reach steady state, whereas at Erms = 12 V/mm (Figure 5c) and 20 V/mm (Figure 5d), steady state was attained within ~500 s. An expanded view of the stress response at Erms = 12 V/mm (Figure 5e) revealed more pronounced increases in stress corresponding to positive field maxima. With increasing field strength, the responsiveness of stress to the applied field became more evident. Furthermore, at Erms = 12 V/mm, the responsiveness accelerated after

s, while at Erms = 20 V/mm, a similar acceleration occurred after

s. During these transition periods (indicated by green arrows), the relationship between field strength and stress appeared complex. These results suggest that reversible clay flocs, formed under field application, gradually reorganize into more uniform network-like higher-order structures over time. A common feature across these ER behaviors was that stress remained elevated (corresponding to the minima of the fluctuating stress) even during the zero-field periods when the field polarity reversed. This implies that the higher-order structures of clay flocs induced by the field required a finite relaxation time to redisperse upon field removal. Although the detailed mechanism of stress response remains unclear, the results suggest that polarity-independent effects contribute to the increase in median stress, while polarity-dependent effects are superimposed on this baseline response.

Figure 5.

Dependence of shear stress response on effective electric field strength in deionized fluorinated hectorite (Ht-F) aqueous dispersion under AC electric fields at 25 °C. Clay volume fraction φ = 0.001, shear rate

= 19 s−1. (a) Time variation in electric field strength. Field frequency fE = 0.01 Hz. (b–e) Time variation in shear stress. (b) Erms = 8.0 V/mm; (c) 12 V/mm; (d) 20 V/mm; (e) enlarged view of the range t = 1000–1500 s in panel (c), indicated by the gray rectangle. Black arrows denote the electric-field maxima, and blue arrows denote the minima. The same arrows are also shown near the shear stress maxima.

is the ratio of the total number of electric field maxima and minima (

) to the number of shear stress maxima (

), i.e.,

=

/

.

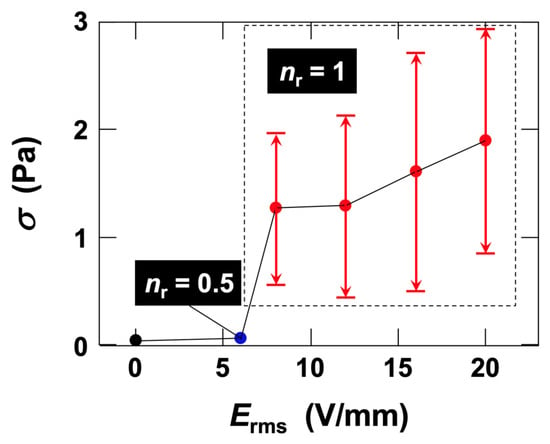

After σ reached a steady state under field application, the effects of Erms on the median as well as on the maximum and minimum values were summarized (Figure 6). ER effects were observed at Erms = 6.0 V/mm (Figure 3) and higher; however, the effects were very small, and the fluctuation amplitude of σ was also minimal. Therefore, only the median values are shown for this case. With increasing Erms, the median σ increased, and the amplitude of σ fluctuations associated with changes in Erms also expanded. It should be noted that the vertical arrows extending from the plots at Erms ≥ 8.0 V/mm indicate the fluctuation range of σ (difference between maximum and minimum values) corresponding to the field strength, and do not represent experimental errors.

Figure 6.

Dependence of the fluctuation range and median of shear stress on root-mean-square electric field strength in deionized fluorinated hectorite (Ht-F) aqueous dispersion under AC electric fields at 25 °C. Clay volume fraction φ = 0.001, shear rate

= 19 s−1, field frequency fE = 0.01 Hz. The fluctuation range represents the difference between maximum and minimum shear stress. Circles: median values of shear stress fluctuation range.

is the ratio of the total number of electric field maxima and minima () to the number of shear stress maxima (), i.e.,

=

/

.

In this study, the gap between the inner and outer cylinders was fixed at either 0.35 mm or 0.5 mm. In general, increasing the gap requires a higher applied voltage to achieve the same electric field strength, which can promote electrolysis in aqueous dispersions and consequently diminish or eliminate the ER response. Therefore, in water-based ER measurements, avoiding excessively large gaps and ensuring an appropriate gap width are essential for maintaining stable ER behavior. The influence of electric-field frequency on the stress response was investigated (Figure 7a). At the lowest frequency, fE = 0.01 Hz, both the median σ and the fluctuation amplitude of σ with changes in field strength were the largest among all tested fE values. At fE = 0.1 Hz, σ still increased under the field, but both the rate of increase and the fluctuation amplitude decreased markedly. A notable feature was the stress response to changes in field strength: at fE = 0.01 Hz, nr = 1, whereas at fE = 0.1 Hz, nr ≈ 0.5. This indicates that σ could not fully follow the speed of field variation. At a higher frequency of fE = 1.0 Hz, σ increased to a similar extent as at fE = 0.1 Hz, but without fluctuations, reaching a steady value. At fE = 10 Hz, no change in σ was observed under field application, i.e., no ER effect was detected. The effects of fE on both the fluctuation amplitude and the median σ were summarized (Figure 7b). Both values were determined as representative values in the steady state. With increasing fE, the fluctuation amplitude decreased, and at fE = 1.0 Hz, stress fluctuations disappeared, leaving only a steady increase in σ. At fE = 10 Hz, no increase in σ was observed under the applied field. The lowest fE at which stress fluctuations vanished was defined as the critical frequency fE*, indicated by gray vertical lines in the figure. Previously reported fE* values at Erms = 8.0 V/mm for Sap, Ht [16], Ht-F, and Stv [17] are also shown in the figure. At this field strength, fE* was 0.005 Hz for Sap and Ht, while it was 0.05 Hz for Ht-F and Stv, clearly demonstrating clay-type dependence of fE*. Moreover, for Ht-F, fE* increased significantly from 0.05 Hz to 1.0 Hz with increasing field strength. These results demonstrate that increasing fE leads to reductions in nr and in the amplitude of stress fluctuations. The fact that the ERS effect observed in micron-sized particle dispersions also disappears at fE ≈ 0.1 Hz or higher supports our interpretation that the ER effect in this study shares a common mechanism—namely, field-induced floc formation in water.

Figure 7.

(a) Frequency dependence of shear stress response in deionized fluorinated hectorite (Ht-F) aqueous dispersion during application and removal of an AC electric field at 25 °C. Clay volume fraction φ = 0.001, shear rate

= 19 s−1, Erms = 16 V/mm. Red line: fE = 0.01 Hz; orange line: 0.1 Hz; blue line: 1.0 Hz; black line: 10 Hz. (b) Frequency dependence of the fluctuation range and median of shear stress under applied AC electric fields. Circles: median values of shear stress fluctuation range.

is the ratio of the total number of electric field maxima and minima () to the number of shear stress maxima (), i.e.,

=

/

.

= n.a. indicates that no stress fluctuations were observed under the applied electric field. Gray vertical lines denote the critical electric field frequency fE* at which

disappeared for each sample and field strength.

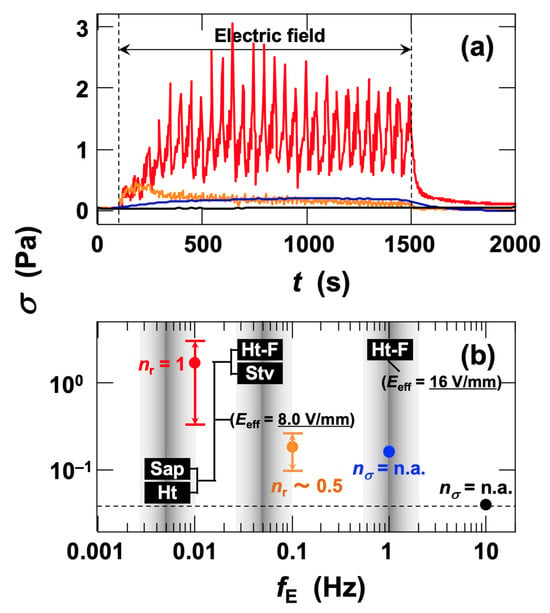

3.2.2. Stress Response of Sap Dispersions to AC Electric Fields

The frequency dependence of the stress response of Sap dispersions to AC electric fields was investigated (Figure 8). Because σ values exhibited large variations after field application, the vertical axis in the figure is shown on a logarithmic scale. At fE = 0.001 Hz (Figure 8a), σ fluctuated with changes in field strength, but nr = 0.5. Stress maxima were observed only when the electric field reached its positive maxima. Compared with Ht-F dispersions, the responsiveness of σ to the applied field was much poorer, even at this very low frequency. As the number of field cycles increased, the fluctuation of σ diminished and σ increased monotonically toward a constant value. These results suggest that irreversible clay aggregates formed over time in response to field application and removal. When the field frequency was increased to fE = 0.005 Hz (Figure 8b), σ increased monotonically to a constant value with almost no periodic fluctuations. In this case as well, clay aggregates induced by the electric field exhibited strongly irreversible behavior with respect to field application and removal. The irreversibility of the stress response of Sap dispersions under AC fields is a distinct feature of this system, and it is not limited to AC conditions. For dispersions of other clays, such as Ht [15] and Stv [17,18], σ tends to recover, albeit incompletely, toward its initial value after removal of a DC field. Therefore, the stress increase upon field application cannot be attributed to an increase in electrolyte concentration in the dispersion. In contrast, Sap dispersions maintained their σ values even after field removal. This observation is consistent with the irreversibility observed at fE = 0.001 Hz (Figure 8a), a condition essentially equivalent to a DC field.

Figure 8.

Time evolution of shear stress in deionized saponite (Sap) aqueous dispersion during application and removal of an AC electric field at 25 °C. Clay volume fraction φ = 0.001, shear rate

= 19 s−1, effective field strength Erms = 8.0 V/mm. (a) Field frequency fE = 0.001 Hz. (b) 0.005 Hz. Red arrows denote the electric-field maxima, and blue arrows denote the minima. The same arrows are also shown near the shear stress maxima.

is the ratio of the total number of electric field maxima and minima () to the number of shear stress maxima (), i.e.,

=

/

.

Photographs of the inner-cylinder (positive electrode) surface after application of a DC field are shown in Figure 9. Although only Ht-F and Sap are presented here, all four clay dispersions examined in this study tended to form thin, gel-like films on the positive electrode surface. This tendency was particularly pronounced for Sap, where the gel-like film exhibited numerous traces of bubbles generated by electrolysis (Figure 9b). During removal of the inner cylinder from the outer cylinder, a portion of the film at the lower left peeled off; however, the clear boundary remaining between the detached area and the residual film suggests that a relatively robust gel had been formed. Despite this observation, the electrical conductivity of deionized Sap dispersions was the lowest among the clays tested, suggesting that Sap should be less prone to electrolysis. For example, at φ = 0.001, the conductivities of deionized Stv, Ht-F, Ht, and Sap dispersions were 24.9, 9.54, 9.04, and 6.05 mS/m, respectively [11]. A plausible explanation for the ease of gel-film formation in Sap dispersions is ion release induced by DC fields. This idea is supported by the fact that Sap possesses the highest cation exchange capacity (CEC) among the four clays [11]. Indeed, smectite clays are known to retain exchangeable cations in their interlayer spaces, which can migrate into the bulk water under external fields. Previous studies have reported that application of DC fields to Na-montmorillonite and beidellite results in migration of exchangeable cations such as Na+ and Ca2+ toward the electrodes, leading to their release from clay samples [42,43,44]. Tracer experiments have further demonstrated the high electrophoretic mobility of Na+ [45,46], providing quantitative evidence for ion mobilization under conduction. Additionally, experiments involving the migration of Ca2+ and HCO3− into beidellite dispersions under electric fields confirmed precipitation of CaCO3 within the clay and concurrent release of exchangeable Na+ [47]. These findings collectively indicate that ion release from clays under DC fields is a general phenomenon. Because the dispersions in this study were highly deionized using ion-exchange resin, electrolysis should have been relatively suppressed even under DC fields, highlighting the singular behavior of Sap. The observed gel-film formation under DC fields may be partly attributable to excessive compression of clay particles onto the positive electrode surface by electrophoresis. At such high local concentrations, clays themselves could act as electrolytes, compressing the surrounding electrical double layers and inducing irreversible aggregation. This process would make electrolysis more likely near the electrode surface. Gadige and Bandyopadhyay [48] reported that non-deionized Laponite dispersions undergo irreversible gelation at the positive electrode surface under DC fields. Dynamic rheological measurements of gel-like materials scraped from the electrode surface using a Teflon spatula confirmed that G′ > G″. This irreversible gelation at the positive electrode surface closely resembles that observed for Sap in the present study. Importantly, however, dispersions of other clays retained relatively good reversibility of stress responses to field application and removal even under DC conditions, implying negligible ion release from these clays. Further detailed investigations of clay ion release under DC fields could be conducted using electrodes fabricated from noble metals (e.g., platinum or gold), carbon-based materials (e.g., carbon fibers, graphite), or conductive oxides (e.g., ITO). By contrast, under AC fields, no gel-like films were observed on the positive electrode surface (Figure 9c,d). It was striking that no such films appeared even at the extremely low frequency of fE = 0.01 Hz, where conditions are nearly equivalent to DC fields. This can also be attributed to the high degree of deionization of the dispersions employed in this study. As noted above, dispersions of Stv, Ht-F, and Ht exhibited reversible stress responses to AC field application and removal [16,17,18]. The fact that only Sap showed irreversible stress responses supports our hypothesis that Sap releases ions under applied fields. The irreversibility of Sap can be attributed to the formation of irreversible aggregates with respect to the field. In contrast, dispersions of Stv, Ht-F, and Ht form reversible flocs under AC fields.

Figure 9.

Images of the rheometer inner cylinder (positive electrode) surface after application of an electric field at 25 °C. Clay volume fraction φ = 0.001. (a,b) DC field, E = 8.0 V/mm; (c,d) AC field, fE = 0.01 Hz, Erms = 8.0 V/mm. The fields were applied for 2000 s to Ht-F and Sap dispersions. (a,c) Deionized Ht-F dispersion; (b,d) Deionized Sap dispersion. Scale bar = 10 mm.

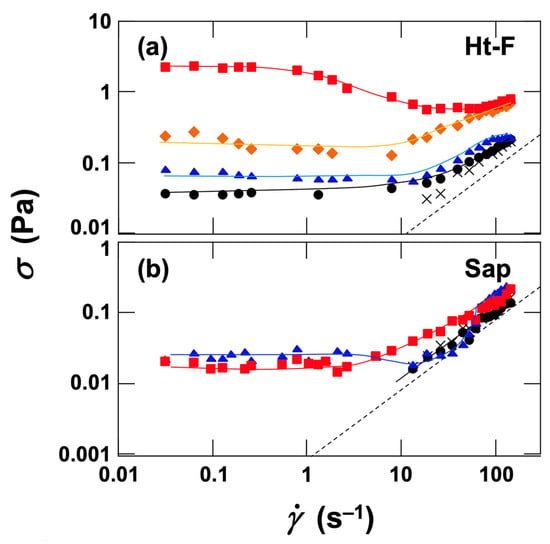

3.2.3. Flow Curves

To evaluate ER effects under steady flow, flow curves were obtained under DC fields (Figure 10). The values for water are shown as dotted lines for reference. Both Ht-F (Figure 10a) and Sap (Figure 10b) dispersions exhibited Newtonian behavior in the absence of electric fields. At shear rates

< 19 s−1, the torque transmitted to the inner cylinder of the rheometer was too small, and σ could not be detected. For Ht-F dispersions, σ increased with increasing field strength. At low shear rates, plastic flow behavior was observed, whereas at high shear rates, the response approached Newtonian behavior. In contrast, for Sap dispersions, σ did not increase up to E = 2.0 V/mm DC, but at E ≥ 4.0 V/mm DC, increases in σ were observed, particularly in the low-shear-rate region, showing plastic flow. Interestingly, at E = 8.0 V/mm DC, the stress values were lower than those at E = 4.0 V/mm DC. Moreover, the relative increase in stress under field application was considerably smaller for Sap dispersions than for Ht-F dispersions. These results suggest that the larger particle size of Sap led to lower number density compared with Ht-F, and that electrophoresis and gel-like film formation at the inner-cylinder (positive electrode) surface, associated with increased local ion concentration, also contributed to the observed behavior. It should be noted that the shear stresses of the dispersions under field application in this study represent apparent values. In particular, the stress increases observed for Sap dispersions were irreversible with respect to field application and removal; therefore, it is more appropriate to describe them simply as “stress increases under field application” rather than as ER effects in the strict sense.

Figure 10.

Flow curves of deionized (a) fluorinated hectorite (Ht-F) and (b) saponite (Sap) aqueous dispersions under applied DC electric fields at 25 °C. Clay volume fraction φ = 0.001. Dashed line: reference value for water. ×: without field; ●: 2.0 V/mm DC; ▲: 4.0 V/mm DC; ◆: 6.0 V/mm DC; ■: 8.0 V/mm DC.

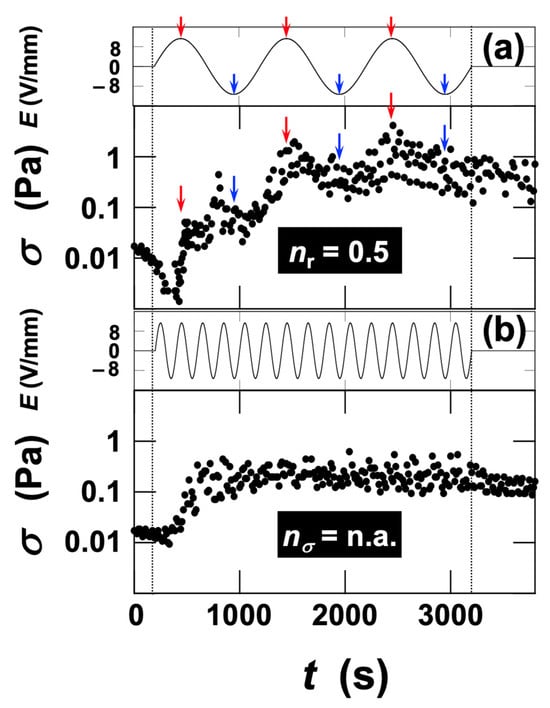

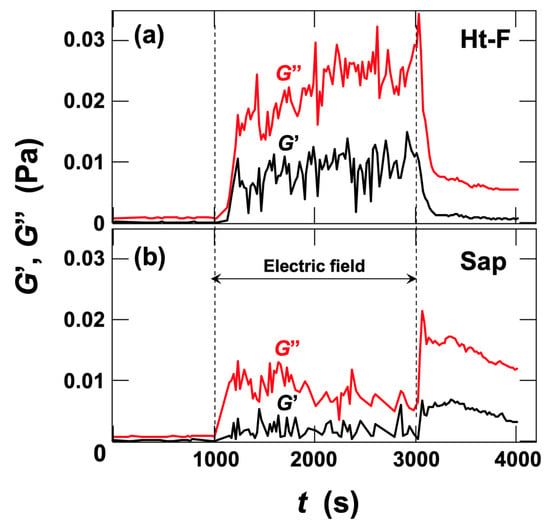

3.2.4. Rheological Measurements Under Dynamic Deformation

Dynamic rheological measurements under DC fields were performed for Ht-F and Sap dispersions (Figure 11). Upon application of a DC field, both G′ and G″ increased. Notably, the values of G″ greatly exceeded those of G′. This clearly demonstrated, for the first time, that the application of electric fields to clay dispersions predominantly enhances viscous properties. This finding suggests that the aggregates formed under the field are bound primarily through weak interactions such as van der Waals forces and induced dipole moments. When the field was removed, both G′ and G″ exhibited a sharp, transient increase, followed by a decrease. For Ht-F dispersions, G′ and G″ decreased toward their initial values, whereas for Sap dispersions, the decrease was much slower and the values remained higher than those under field application. The transient rise in G′ and G″ upon field removal can be interpreted as the relaxation of aggregates that had been biased toward the positive electrode (inner cylinder) under DC or very low-frequency AC fields [18]. In typical nonaqueous ER fluids, application of electric fields leads to a dominant increase in storage modulus G′, corresponding to a liquid-to-solid transition [5]. In contrast, for the clay dispersions studied here, the increase in loss modulus G″ was more pronounced than that of G′, revealing for the first time that their ER response is characterized primarily by an enhancement of viscous rather than elastic behavior.

Figure 11.

Time evolution of storage modulus G′ and loss modulus G″ in deionized (a) fluorinated hectorite (Ht-F) and (b) saponite (Sap) aqueous dispersions during application and removal of a DC electric field at 25 °C. Clay volume fraction φ = 0.001, E = 8.0 V/mm DC. Strain amplitude γ = 0.1, angular frequency

= 0.63 rad/s. Black line: G′; red line: G″.

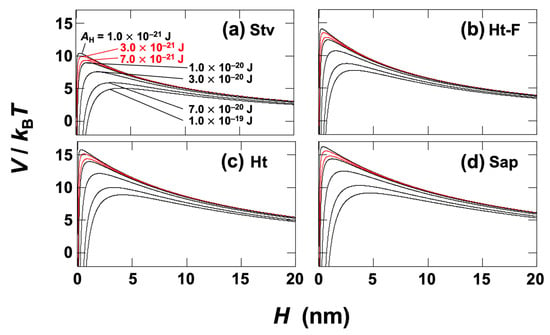

3.3. DLVO Potential Calculation

The formation of clay aggregates under electric fields is considered to result from changes in the balance between van der Waals attraction and electrostatic repulsion due to the presence of electrical double layers. To examine the electrostatic interactions between clays, DLVO potential curves were constructed. Because the dispersions were highly deionized over long periods, the clays in water were assumed to be dispersed as individual sheets. To approximate each disk-shaped sheet as a sphere, the Stokes diameter dS was calculated using the following equation [49].

Here, d is the diameter of the clay nanosheet, and ρ is the ratio of d to the sheet thickness. The dS values of Ht-F, Stv, Ht, and Sap were 9.6 nm, 10.3 nm, 13.6 nm, and 15.9 nm, respectively. The potential energy in DLVO theory is expressed as follows [50,51].

Here, V is the total potential energy, VR is the electrostatic repulsive potential, VA is the van der Waals attractive potential, d is the particle diameter, ε is the dielectric constant of water, Ψ0 is the surface potential of the particle, H is the interparticle distance, LD is the Debye length, and AH is the Hamaker constant. The expression for VR is applicable when d < LD [52]. In this study, d was replaced by the dS, and Ψ0 was replaced by the ζ potential. At 25 °C, the Debye length LD at an electrolyte concentration c (mol/L) is expressed as follows.

From the conductivity of the ultrapure water used, c was estimated to be 1.0 × 10−5 mol/L [18]. As a result, LD was calculated to be 96 nm. Several values of the AH were chosen from the typical range for general materials, 1.0 × 10−21–1.0 × 10−19 J. According to previous studies by other groups, the Hamaker constant of clays in water, including oxides and layered silicates, is on the order of 10−21 J [53], with many reports specifying a narrower range of approximately 3 − 7 × 10−21 J [54,55,56]. Therefore, in Figure 12, reference curves calculated with AH = 3 × 10−21 J and 7 × 10−21 J are shown in red. In Figure 12, the peak barrier heights of the potential curves increased in the order Stv < Ht-F < Ht < Sap. This sequence was identical to the order of dispersions showing superior to inferior stress responsiveness under applied fields. The peak barrier heights were relatively low, on the order of V/kBT ≈ 10–15, indicating that all clays studied here are dispersed in water as single particles or small, weakly associated aggregates. Assuming that application of an electric field introduces a secondary minimum in the potential curves, systems with lower barriers are expected to exhibit stronger van der Waals interactions between clays and thus greater viscous contributions from aggregates, leading to enhanced stress responsiveness to electric fields. Here, stress responsiveness refers to both the rate of stress adaptation to field changes and the magnitude of stress variations. This interpretation supports the observation that Ht-F, with its lower barrier, exhibits superior stress responsiveness, whereas Sap, with its higher barrier, shows poorer responsiveness. Indeed, previous studies [17,18] have demonstrated that the stress response of Stv dispersions is as good as or even better than that of Ht-F. For Sap, however, it should be noted that irreversible aggregate formation due to ion release under applied fields, as discussed above, may also contribute to its distinct behavior. As discussed in the Introduction, the ER effect is highly sensitive to the electrical double layer surrounding clay particles. In this context, it is particularly intriguing that even under field-free conditions, the rheological properties of clay dispersions—such as yield stress and elasticity—are strongly correlated with their zeta potential [11]. This observation further emphasizes the pivotal role of interfacial electrostatics in governing both the static and field-induced behaviors of smectite dispersions.

Figure 12.

DLVO potential curves between clay particles in water at 25 °C. Debye screening length LD = 96 nm. Several Hamaker constants AH were selected in the range of 1.0 × 10−21 to 1.0 × 10−19 J. Curves calculated with AH = 3.0 × 10−21 J and 7.0 × 10−21 J are shown in red for reference. (a) Stevensite (Stv), dS = 10.3 nm, ζ = −45 mV; (b) fluorinated hectorite (Ht-F), dS = 9.6 nm, ζ = −54 mV; (c) hectorite (Ht), dS = 13.6 nm, ζ = −48 mV; (d) saponite (Sap), dS = 15.9 nm, ζ = −45 mV.

In this study, four types of smectite aqueous dispersions—fluorinated hectorite (Ht-F), stevensite (Stv), hectorite (Ht), and saponite (Sap)—were systematically compared in terms of optical transparency, field responsiveness, dynamic rheological properties, and DLVO potential analysis. The results revealed that higher apparent transparency corresponded to finer network skeletons, and that dispersions with greater transparency exhibited higher reversibility to electric field on–off switching. A fundamental difference arising from particle size was also confirmed: whereas micron-sized particles exhibited the ERS effect accompanied by sedimentation or flotation, nanosized clays remained homogeneously dispersed and developed ER effects through floc formation and network structuring. Notably, Ht-F showed partially irreversible behavior under DC fields but, like Stv, maintained high reversibility and superior stress-following characteristics under low-frequency AC fields. In contrast, Sap exhibited irreversible stress increases, likely associated with ion release under applied fields. Furthermore, dynamic rheological measurements demonstrated that the application of electric fields enhanced G″ more prominently than G′, indicating a characteristic strengthening of viscous behavior that distinguishes these aqueous smectite systems from conventional nonaqueous ER fluids.

DLVO analysis revealed no distinct secondary minimum in the calculated potential curves. The primary potential barrier heights were arranged in the order Stv < Ht-F < Ht < Sap, and this hierarchy corresponded closely to the ease of field-induced flocculation and the strength of the ER response. For Stv, which possesses the lowest primary barrier, electric-field-induced particle approach occurs most readily, enabling rapid and reversible network formation. Ht-F exhibited the second-lowest barrier; although the rate of floc formation was somewhat slower than that of Stv, it maintained high reversibility under AC fields. Ht, with a higher barrier, required stronger field-induced dipolar attraction to overcome electrostatic double-layer repulsion, resulting in a slower onset of the ER response and reduced sensitivity to field modulation. Sap displayed the highest primary barrier, consistent with its experimentally observed tendency to undergo irreversible aggregation under DC fields. Furthermore, the reversible increase and decrease in viscosity upon field application and removal can be interpreted as the electric field locally generating an “effective attractive potential” analogous to a secondary minimum, enabling reversible floc formation and breakup. These results clarify the causal relationship whereby a lower primary potential barrier promotes rapid and reversible field-induced flocculation, demonstrating that the intrinsic DLVO interactions of smectites govern the hierarchical nature of their macroscopic ER responses.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated for the first time that the hierarchy of ER responses in smectite clay aqueous dispersions corresponds directly to the height of the DLVO potential barriers governing interparticle interactions. In particular, Stv and Ht-F, which possess relatively low potential barriers, exhibited excellent reversibility and strong stress-following characteristics under low-frequency AC electric fields. In contrast, Ht and Sap—with higher barriers—showed less pronounced field-induced structuring and a tendency toward partial irreversibility. These findings indicate that the electrorheological behavior of smectite dispersions can be predicted from their physicochemical properties, providing a foundation for the structural design of clay-based ER fluids and the development of new functional materials. Comparison with the ERS effect further revealed an important universal mechanism: both nanoscale clays and micron-sized particles share a common process of “electric-field-induced floc formation,” although the macroscopic manifestations differ because of the particle-size dependence of sedimentation or flotation. The results of this study also suggest several promising directions for future research. First, to understand the dynamic competition between induced dipolar attraction and electrostatic double-layer repulsion, systematic investigation of frequency dependence—including higher-frequency AC fields—is required. Second, extending the present framework to a broader range of smectites with different layer-charge magnitudes and origins may uncover new regimes of field-induced structuring. Third, integrating time-resolved observational techniques such as optical microscopy, light scattering, and X-ray measurements with DLVO-based interaction analysis could enable the development of quantitative models that bridge particle-scale interaction potentials with macroscopic rheological properties. The reversible and electrically tunable viscosity responses observed in aqueous smectite dispersions highlight their potential for environmentally compatible ER devices, soft actuators, and stimulus-responsive gel materials. Continued exploration of clay-based functional materials will therefore be an important avenue for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.K.; methodology, H.K.; validation, H.K. and A.I.; formal analysis, H.K. and A.I.; investigation, H.K. and A.I.; resources, H.K.; data curation, H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.K.; writing—review and editing, H.K.; supervision, H.K.; project administration, H.K.; funding acquisition, H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge KUNIMINE INDUSTRIES CO., LTD., the manufacturer of the clay, and express their sincere thanks to H. Tanabe and S. Shinoki for their insightful advice on the chemical composition of the clay minerals. Special thanks are extended to C. Deshun for his valuable assistance in performing the experiments. This study was partly supported by the Instrumental Analysis Division, Life Science Research Center, Gifu University. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or nonprofit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Winslow, W.M. Induced fibration of suspensions. J. Appl. Phys. 1949, 20, 1137–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, H.; Kelly, J.P. Electro-rheology. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1988, 21, 1661–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsey, T.C. Electrorheological fluids. Science 1992, 258, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, L.; Munteanu, A.; Sedlacik, M. Electrorheological fluids: A living review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2025, 151, 101421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, B.D.; Winter, H.H. Field-induced gelation, yield stress, and fragility of an electro-rheological suspension. Rheol. Acta 2002, 41, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, M.; Klingenberg, D.J. Electrorheology: Mechanisms and models. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 1996, 17, 57–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-B.; Hong, S.-R. Dynamic modeling and vibration control of electrorheological mounts. J. Vib. Acoust. 2004, 126, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.-A.; Jorgensen, S.J.; Ho, J.; Sentis, L. Characterization and testing of an electrorheological fluid valve for control of ERF actuators. Actuators 2015, 4, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitczuk, J.; Weinberg, B.; Canavan, P.K.; Mavroidis, C. Active knee rehabilitation orthotic device with variable damping characteristics implemented via an electrorheological fluid. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2010, 15, 952–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abend, S.; Lagaly, G. Sol–gel transitions of sodium montmorillonite dispersions. Appl. Clay Sci. 2000, 16, 201–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Tanabe, H.; Shinoki, S. Zeta potential as a key indicator of network structure and rheological behavior in smectite clay dispersions. Fluids 2025, 10, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombácz, E.; Ábrahám, I.; Gilde, M.; Szánto, F. The pH-dependent colloidal stability of aqueous montmorillonite suspensions. Colloid Surf. A 1990, 49, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, R.K. Ionic forces in thick films of liquid between charged surfaces. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1946, 42, B219–B225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, J.D.; Ramos-Tejada, M.M.; Arroyo, F.J.; González-Caballero, F. Rheological and electrokinetic properties of sodium montmorillonite suspensions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2000, 229, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Sugiyama, T.; Takahashi, S.; Tsuchida, A. Viscosity change in aqueous hectorite suspension activated by DC electric field. Rheol. Acta 2013, 52, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Ueno, M.; Takahashi, S.; Tsuchida, A.; Kurosaka, K. Electrically induced reversible viscosity change in hectorite aqueous dispersion under an AC electric field. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014, 99, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Nakashima, A.; Takahashi, S.; Tsuchida, A.; Kurosaka, K. Changes of viscosity in stevensite aqueous dispersions with application of an electric field of the order of a few V/mm. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 114, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H. Influence of alternating electric field on electrorheological effect of aqueous dispersions of stevensite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 254, 107393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels-Brito, P.H.; Malfatti-Gasperini, A.; Mayr, L.; Puentes-Martinez, X.; Tenorio, R.P.; Wagner, D.R.; Knudsen, K.D.; Araki, K.; Oliveira, R.G.; Breu, J.; et al. Unmodified clay nanosheets at the air–water interface. Langmuir 2021, 37, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worasith, N.; Goodman, B.A. Clay mineral products for improving environmental quality. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 242, 106980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Gao, C.Y.; Nam, J.D.; Choi, H.J. Cellulose-based smart fluids under applied electric fields. Materials 2017, 10, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Q.; Ranjith, P.G.; Long, X.; Kang, Y.; Huang, M. A review of shale swelling by water adsorption. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015, 27, 1421–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Takahashi, S.; Tsuchida, A. Rapid sedimentation of poly(methyl methacrylate) spheres and montmorillonite particles in water upon application of a DC electric field of the order of a few V/mm. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014, 101, 623–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Tsuchida, A. Sedimentation behavior of poly(methyl methacrylate) spheres in water upon application of a DC vertical electric field of the order of a few V/mm. Powder Technol. 2017, 320, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H. Co-flocculation of mixed-sized colloidal particles in aqueous dispersions under a DC electric field. Materials 2025, 18, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H. Rapid ascent of hollow particles in water induced by an electric field. Powders 2023, 2, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Sakakibara, M. Electric field-induced settling and flotation of flocs in mixed aqueous suspensions of poly(methyl methacrylate) and aluminosilicate hollow particles. Materials 2025, 18, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H. Impact of DC electric field direction on sedimentation behavior of colloidal particles in water. Materials 2025, 18, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollah, M.Y.A.; Morkovsky, P.; Gomes, J.A.G.; Kesmez, M.; Parga, J.; Cocke, D.L. Fundamentals, present and future perspectives of electrocoagulation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2004, 114, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, P.K.; Barton, G.W.; Mitchell, C.A. The future for electrocoagulation as a localised water treatment technology. Chemosphere 2005, 59, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamjomeh, M.M.; Sivakumar, M. Review of pollutants removed by electrocoagulation and electrocoagulation/flotation processes. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1663–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuokkanen, V.; Kuokkanen, T.; Rämö, J.; Lassi, U. Recent applications of electrocoagulation in treatment of water and wastewater—A review. Green Sustain. Chem. 2013, 3, 89–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.; Chaudhari, P.K.; Dubey, S.; Prajapati, A.K. Electrocoagulation treatment of electroplating wastewater: A review. J. Environ. Eng. 2020, 146, 03120009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H. Deionization-induced colorless transparency in physical gels formed by clay aqueous dispersions. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 249, 107261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, M.; Vos, W.L.; Wegdam, G.H. Structure and formation of a gel of colloidal discs. Phys. Rev. E 1998, 57, 1962–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, D.; Tanaka, H.; Wegdam, G.; Kellay, H.; Meunier, J. Aging of a colloidal “Wigner” glass. Europhys. Lett. 1998, 45, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourchid, A.; Levitz, P. Long-term gelation of laponite aqueous dispersions. Phys. Rev. E 1998, 57, R4887–R4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, H.Z. Liquid, glass, gel: The phases of colloidal laponite. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2007, 353, 3891–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Jdayil, B. Rheology of sodium and calcium bentonite–water dispersions: Effect of electrolytes and aging time. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2011, 98, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, P.-I.; Leong, Y.-K. Surface chemistry and rheology of laponite dispersions: Zeta potential, yield stress, ageing, fractal dimension and pyrophosphate. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 107, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Y.K.; Clode, P.L. Time-dependent clay gels: Stepdown shear rate behavior, microstructure, ageing, and phase state ambiguity. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 123329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, H.S.; Mortland, M.M. Ion movement in Wyoming bentonite during electroosmosis. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1959, 23, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashihara, T.; Kinoshita, K.; Sato, S.; Kozaki, T. Electromigration of sodium ions and electro-osmotic flow in water-saturated, compacted Na-montmorillonite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2004, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loch, J.P.G.; Lima, A.T.; Kleingeld, P.J. Geochemical effects of electro-osmosis in clays. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2010, 40, 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashihara, T.; Kinoshita, K.; Akagi, Y.; Sato, S.; Kozaki, T. Transport number of sodium ions in water-saturated, compacted Na-montmorillonite. Phys. Chem. Earth 2008, 33, S142–S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Noda, N.; Sato, S.; Kozaki, T.; Sato, H.; Hatanaka, K. Electrokinetic study of migration of anions, cations, and water in water-saturated compacted sodium montmorillonite. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmadetin, J.; Mizuto, M.; Tanaka, S.; Kozaki, T.; Watanabe, N. Calcium carbonate precipitation in compacted bentonite using electromigration reaction method and its application to estimate the ion activity coefficient in the porewater. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadige, P.; Bandyopadhyay, R. Electric field induced gelation in aqueous nanoclay suspensions. Soft Matter 2018, 14, 6974–6982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, B.R.; Parslow, K. Particle size measurement: The equivalent spherical diameter. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1988, 419, 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Derjaguin, B.; Landau, L.D. Theory of the stability of strongly charged lyophobic sols and of the adhesion of strongly charged particles in solutions of electrolytes. Acta Physicochim. URSS 1941, 14, 633–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verwey, E.J.W.; Overbeek, J.T.G. Theory of the Stability of Lyophobic Colloids; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, R.J. Foundations of Colloid Science, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bergström, L. Hamaker constants of inorganic materials. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 70, 125–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tester, C.C.; Aloni, S.; Gilbert, B.; Banfield, J.F. Short- and long-range attractive forces that influence the structure of montmorillonite osmotic hydrates. Langmuir 2016, 32, 12039–12046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, C.; Kaufhold, S. Hamaker functions for kaolinite and montmorillonite. Colloid Interface Sci. Commun. 2021, 43, 100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Bourg, I.C. Interaction between hydrated smectite clay particles as a function of salinity (0–1 M) and counterion type (Na, K, Ca). J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 20990–20997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).