1. Introduction

Vehicular congestion, long travel times and increased pollutant emissions are becoming extremely serious as the rapid urbanization continues together with the slow road network extension. Static shortest-path algorithms, such as Dijkstra’s or A* algorithms, are ineffective in such circumstances due to their susceptibility to the rapidly changing environment because of incidents, traffic signal operations and localized driving behaviors. Genetic algorithms, in particular, offer a robust gradient-free search paradigm with inherent parallelism which is suitable for adaptive routing, and (when modeled) signal timing optimization; and our focuses dynamic, GA-based routing. Nevertheless, the pragmatic manual implementation of ITS, requires the fulfillment of several crucial requirements which are: (i) metropolitan scale responsiveness; (ii) fitness function proper construction and strict validation; and (iii) ability to validate against real-time data streams and computational resource limitations. To this effect, we present an explicitly sensitivity-aware genetic algorithm architecture which can be used on edge computing platforms.

Novelty & scope statement. In this study we avoid developing a new GA variant but contribute to the field with a deployed awareness edge-assisted GA pipeline, containing proper messaging protocols to adopt and closed-loop re-routing requirement (e.g., using MQTT, Kafka, TraCI), and a normalized fitness (α + β + γ = 1), systematic Pareto-Front construction, and knee point selection (median waiting time). A city-scale network calibrated by the field data from different congestion regimes ranging from no-congestion to occasional to high-congestion conditions was empirically validated. Accordingly, we classify this work as a technological innovation whose primary goal is to make GA-based dynamic routing usable in high-congestion scenarios, thus completing algorithmic work on GA-PSO hybrid systems and reinforcement-learning/multi-agent reinforcement-learning architectures.

Increasing vehicle numbers and rapid population growth are outstripping the growth of road infrastructure in urban areas, resulting in urban mobility becoming a major challenge in modern cities. The consequence of this imbalance is higher levels of traffic congestion, longer travel times and increased environmental pollution. According to [

1], traffic congestion in urban centers cost global economies about

$87 billion annually in loss of time and fuel, in 2020. Moreover, with the growth of cities, complexities regarding traffic management are increasingly needed, and the existing techniques are incapable of matching the dynamic traffic flows in urban areas.

Urbanization means, long road journeys, growing air pollution and bad quality of life for urban people. One of the problems with these issues, in particular, is the inability of traditional traffic management systems to adapt to varying traffic conditions. Traditionally, existing methods such as existing algorithms, search for the most direct path (shortest path) depending on static conditions and are not based on current traffic coefficients such as traffic light timing, congestion, and driver behavior [

2]. Consequently, much of travel time and fuel consumption during peak traffic periods tend to be unnecessarily high.

For these challenges, we need to consider a more dynamic, more adaptive approach to optimize urban traffic flow. Advances in computational intelligence in recent decades, especially in optimization algorithms, including Genetic Algorithms (GAs), show great promise for implementing efficient traffic management solutions in urban settings. GAs, a global optimization method inspired by natural selection and the principles of biological evolution, have the advantage of evolving solutions to complex problems over time, making them more robust compared to local optimization methods. These algorithms have been successfully applied to many engineering and economics optimization problems [

3]. With the use of GAs, traffic routing can be optimized in terms of urban mobility, taking into account a number of dynamic factors, such as real-time traffic congestion, traffic light timing, and even driver behavior patterns, to produce intelligent routes that adapt to the current traffic environment.

The effectiveness of GAs for optimizing traffic flow has been previously demonstrated in various urban contexts. For instance, ref. [

4] introduced a traffic management system capable of optimizing traffic signal control through a GA, reducing travel time and congestion. Similarly, dynamic traffic light timing adjustments using GAs have been shown by [

5] to improve traffic throughput. However, these methods often focus on specific aspects of traffic management, such as signal control or route choice, without aggregating various real-time factors into a single adaptive framework.

The initial purpose of this paper is to investigate the applicability of Genetic Algorithms (GAs) for optimizing urban travel times through the dynamic selection of the most efficient travel routes based on real-time traffic conditions. More specifically, this work focuses on optimizing travel within Bethlehem City, which faces significant traffic congestion. The proposed GA-based approach leverages real-time traffic data, including traffic congestion, signal delays, and driver behavior, to solve the problem in real time. This enables more efficient solutions for minimizing travel time and improving overall city mobility.

Contributions:

An edge-assisted genetic algorithm for online re-routing has been developed that deploys explicit communication protocols such as MQTT over TLS 1.3, Kafka aggregation, and TraCI control. The solution results in a quantile latency envelope continuing below second actuation for HTL.

A framework for a multiple-objective tuning is established which is repeatable and includes the standardization of the weight vector (α, β, γ) with α + β+ γ = 1;a simplex grid sweep (Δ = 0.05), Pareto-dominance with knee-point selection, and a guardrail that limits median waiting time.

Chromosomal entities are designed keeping in mind the feasibility, that is, incorporating k–shortest-path repair, include constraints over the capacity and over the occupancy as these are, of course, the realistic traffic flows.

The methodology has been validated on a city-scale network, calibrated to represent different demand tiers, i.e., HTL, MTL and LTL. Results are in the form of runtime performance characteristics, scaling behavior, aggregation and statistical policy analysis.

To ensure seriousness of reproduction, a detailed checklist is included, listing all genetic algorithm and SUMO parameters, early stop values, random seed values, as well as a drop-in configuration manifest.

There are two main differences between the proposed method and existing GA-based methods: (1) The data: This study specifically considers real-world traffic data from Bethlehem City, a context that has not been explored in previous studies. (2) Unaddressed phenomena: The proposed method incorporates dynamic factors like traffic congestion, traffic light timing, and driver behavior patterns, which have not been adequately considered together in GA-based approaches for urban mobility. These distinctions make the proposed method a more comprehensive and context-specific solution for urban traffic optimization.

There are a number of research studies conducted on urban traffic management over a period of decades and many studies are to investigate the problem of congestion, travel time, fuel consumption and environmental impact. These are problems of greater urgency in cities, where population density can mean a very low efficiency and a poor quality of life due to traffic congestion. From classical traffic flow theories to modern computational techniques, various optimization methods have been proposed, with noteworthy achievements through the use of evolutionary algorithms, such as Genetic Algorithms (GAs), for real time traffic optimization [

3,

4,

6,

7].

Traditional Traffic Optimization Techniques (TOTs) have been applied to various routing problems, including the linear aircraft taxi routing problem. These methods, such as shortest path algorithms, are commonly used to optimize vehicle and aircraft movement in constrained environments. However, their limitations in dynamic urban traffic scenarios have been well-documented, especially as they often fail to adapt to real-time changes such as congestion, signal timing, and other dynamic traffic factors [

2,

4,

8]. While TOTs remain useful in some static environments, their inability to handle the complexities of real-time urban mobility has prompted the exploration of more adaptive solutions, such as Genetic Algorithms (GAs).

Traditionally, the predominant traffic management solution has been one based on static models, i.e., shortest path algorithms, which determine the best path between two points, given some static set of metrics for example, distance or travel time. Two well-known algorithms aiming to find the shortest path in road network are Dijkstra’s algorithm [

8] and the A* search algorithm [

9]. However, these methods assume static traffic conditions and ignore the dynamic nature of traffic conditions which fluctuate with real time events such as congestion, accidents and signal delay.

These limitations prompt the development of various adaptive traffic management systems. Traditional approaches, such as, Adaptive Signal Control Technology (ASCT), can adapt traffic signals in real time so as to respond to vehicle flow, but are typically unable to target the whole urban network, particularly driver behavior and network traffic patterns [

10].

This paper is organized as follows: Related work in the traffic optimization area as well as the application of the GA in urban mobility are reviewed in

Section 2. The methodology employed is introduced in

Section 3, which includes the GA approach and the Simulation of Urban Mobility (SUMO) traffic simulation. In

Section 5, the results of the GA based optimization method on Bethlehem City are presented; and then discussed in

Section 5. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and identifies future research directions in this area.

1.1. Use of Genetic Algorithms in Traffic Optimization

Recently, Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are global optimization methods inspired by natural selection principles, effectively handling complex, dynamic systems with multiple objectives and constraints. Their adaptability makes them particularly suitable for urban traffic optimization, addressing challenges such as congestion, travel time, fuel consumption, and environmental impact.

Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of GAs in various traffic optimization applications:

Traffic Signal Control: ref. [

6] introduced a GA-based technique to optimize traffic signal timing at intersections, significantly improving traffic flow and reducing wait times during peak hours.

Multi-Objective Optimization: ref. [

11] developed a multi-objective GA to simultaneously optimize vehicle routing and traffic light control, aiming to minimize total travel time and fuel consumption. Their approach outperformed traditional single-objective methods, showcasing GAs’ versatility in complex urban mobility problems.

Real-Time Traffic Flow Optimization: ref. [

4] employed GAs for adaptive real-time urban traffic flow optimization, incorporating traffic signal control and dynamic route adaptation based on traffic load and signal states. Their method effectively reduced overall travel time, highlighting GAs’ efficacy in real-time applications.

Enhanced Genetic Algorithms: ref. [

7] proposed an enhanced GA for optimizing combined subway and taxi travel routes in Beijing, achieving significant reductions in travel cost and variance compared to standard GAs. This study underscores the potential of GAs in improving urban transportation efficiency.

These studies illustrate the growing application of GAs in urban traffic optimization, demonstrating their capability to adapt to dynamic traffic conditions and effectively address complex transportation challenges.

1.2. GA Applications in Real-Time Traffic Flow

Traffic optimization must be performed in real-time, as traffic conditions can change rapidly due to accidents, construction, and other unpredictable events. Consequently, numerous studies have explored the application of GAs to integrate real-time data from traffic cameras, sensors, and GPS systems, aiming to develop adaptive traffic management systems.

Dynamic Traffic Routing: ref. [

2] proposed a GA-based dynamic traffic routing system that utilizes real-time vehicle information from vehicular ad hoc networks (VANETs) to optimize vehicle routes in urban environments. Their system demonstrated the ability to mitigate congestion and improve overall traffic flow by dynamically adjusting vehicle routes based on live traffic data.

Large-Scale Urban Networks: ref. [

6] employed GAs to optimize traffic flow in large-scale urban networks, leveraging real-time data from GPS-equipped vehicles. Their GA model dynamically adjusted routes based on traffic congestion, road conditions, and signal timings, resulting in significant reductions in travel time, particularly in high-traffic areas.

Traffic Flow Control via Hybrid Models

While GAs can independently address traffic management tasks, hybrid models that combine GAs with other optimization methods—such as simulated annealing, particle swarm optimization, and ant colony optimization—have also yielded promising outcomes. These hybrid approaches aim to leverage the strengths of different algorithms to achieve better performance in complex scenarios.

GA and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): ref. [

12] presented a hybrid model combining GAs and PSO to optimize traffic intensity in urban road networks. Their experiments demonstrated that the hybrid approach exhibited improved convergence speed and solution quality compared to standalone GAs, effectively learning from observational traffic data to enhance optimization efficiency.

GA and Machine Learning: ref. [

13] proposed a hybrid model integrating GAs with machine learning techniques for traffic signal control. By predicting traffic conditions using historical data coupled with real-time vehicle flow information, their approach proactively adjusted signal timings, significantly reducing congestion and travel times, especially in areas with fluctuating traffic patterns.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the successful application of Genetic Algorithms (GAs) in urban mobility optimization, several scientific challenges remain. Existing methods often fail to adequately address the real-time adaptability required in urban traffic systems, especially in the context of rapidly changing traffic conditions, such as accidents, construction, or sudden congestion. While traditional approaches struggle to adjust dynamically, GAs offer the advantage of global optimization, but the challenge lies in integrating them with existing traffic infrastructure, which may require substantial investments in real-time data acquisition systems, such as advanced sensors, cameras, and GPS-based tracking.

Moreover, the large populations of GAs required for seeking optimal solutions in extensive urban networks demand significant computational resources, particularly when applied to large cities with highly dynamic traffic patterns. This presents a challenge in terms of both computational power and scalability, as current systems may struggle to provide timely solutions for real-time traffic management.

In this paper, we aim to address these limitations by focusing on the following scientific issues:

Real-Time Adaptability: Existing methods often fail to account for the continuously changing conditions of urban traffic. The paper will leverage GAs’ ability to adapt to real-time traffic data, improving the responsiveness of the system.

Scalability and Computational Efficiency: The paper will explore how to make GA-based systems scalable and computationally efficient, enabling their application to large and complex urban environments without overwhelming computational resources.

Integration with Advanced Technologies: One of the future directions discussed is the integration of GAs with emerging technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), machine learning, and big data analytics. These technologies can provide continuous streams of real-time data, which will enhance the adaptability and efficiency of GAs in urban mobility optimization.

Dynamic routing & signal control with GAs. Static routing and active signal operation through Genetic Algorithms. One area of previous work has been the joint optimization of traffic signal times and vehicle trajectory paths; hybrid schemes utilizing either particle swarm optimization or reinforcement learning along with genetic algorithms have been shown to have improved convergences and better flexibility. Recent work has started to employ adaptive mutation and crossover schemes, memory assisted operators and embedded predictive models based on data.

Edge/MEC for ITS. Extensive optimization is pushed down to the roadside equipment’s and edge nodes for low latency response; multi-edge IoVs platforms use migration rules and resource allocation for preserving the quality-of-service in the presence of vehicular mobility. These advances influence the design of our edge assisted genetic algorithm, which is described in

Section 5. Implementation details. The RSU microservices publish data into an MQTT broker secured by using TLS 1.3 and using topic partitioning that is linked to individual corridors; the aggregated data in the cloud is processed using Kafka. Command and control interfaces are mediated using the TRACI bridge. Empirical measurements show that the ingest → decision → actuation cycle of the system is completed within 50 ms, 120 ms and 200 ms respectively when the system is under a high traffic load. Consistency is ensured through event strictly time-stamping, periodic snapshots of the RSU Redis cache and strictly idempotent updating thus preventing race conditions in the case of dynamic re-routing.

By tackling these scientific challenges, the paper aims to provide a more efficient, responsive, and scalable solution for urban traffic management, paving the way for intelligent systems capable of learning and adapting to the complexities of real-world urban mobility. This advancement holds the potential to improve both traffic flow and the overall quality of life in urban environments.

Contribution and Novelty. This study provides a reproducible, edge-wise genetic algorithms framework to dynamic multi criteria routing on realistic urban network as simulated using SUMO. In particular, we (i) formalize the selection of the knee-points in a multi-objective fitness landscape through exhaustive sensitivity analysis, (ii) combine travel-time optimization with emissions/fuel proxy thereby quantifying the efficiency vs. environmental impact trade-off, (iii) describe in more detail an edge-cloud architecture—consisting of RSU, broker and cloud components—complete with measured latency budgets and fault-tolerant fallback mechanisms, (iv) report a statistically sound evaluation using Wilcoxon and Mann-Whitney tests with Holm correction, Cliff’s δ and bootstrap confidence intervals in a variety of congestion regimes, and (v) share comprehensive scenarios We compare our approach with state-of-the-art reinforcement learning and GA-PSO baselines, hence providing grounding for the performance and deploy ability of the approach in the current state of the art.

To put our contribution into the context of current research,

Table S1 compares representative GA/GA-PSO, RL and edge-aware ITS studies with those of this study with regard to problems framing, objectives, weighting strategy, deployment feasibility at RSUs, and statistical rigor.

3. Methodology

The core optimization problem in this study is to identify the most efficient travel routes for vehicles in a city, considering dynamic factors such as real-time traffic densities, signal delays, and driver behavior. Formally, the objective is to minimize the total travel time for all vehicles while accounting for constraints such as road capacity, traffic congestion, and traffic light control. The optimization problem can be expressed as:

where:

represents the travel time for vehicle ,

represents the waiting time at traffic signals for vehicle ,

is the total number of vehicles in the system.

This optimization problem is tackled using Genetic Algorithms (GAs), which allow for dynamic route adjustments based on real-time traffic data. The GA-based method involves evolving a population of candidate solutions over multiple generations, selecting and combining them to find the optimal routes that minimize total travel time and waiting time.

The methodology includes several key steps, starting with the collection of real-time traffic data, followed by the execution of the GA optimization process to find the best possible routes for minimizing travel time and congestion. The following sections explain the process in detail.

3.1. Data Quality & Instrumentation Plan

In order to reduce the impact of human error in manual counts and qualitative driver behavior ratings, we used two independent observers, reconciled the differences by analyzing and adjudicating with inter-rater agreement assessment (Cohen’s Kappa) (audit sample size to be reported). Counts were summed across 60 s—periods and filtered using robust IQR (Inter Quartile Range) rules; short gaps were filled with conservative carry forwarded constraints. As external validation, we used short GPS trajectory samples from volunteer drivers in aligned time windows to confirm density patterns. In further iterations we will incorporate automated feeds such as flow detectors for RSUs and camera-based loops (in combination with in device anonymization), and (privacy preserving) close GPS trajectories will be fed into the same SUMO calibrated pipeline.

3.2. Dataset (Bethlehem City)

Bethlehem City was selected as the study area due to the significant traffic congestion, particularly during peak hours. The data used in this study was collected by the researchers during a field study conducted over a period of two weeks, from 1 September 2024 to 14 September 2024, covering various times of the day and different days of the week to capture both peak and off-peak traffic conditions.

A team of researchers, stationed at key roads and intersections around the city, manually counted the number of vehicles and monitored traffic conditions. The researchers recorded data on traffic flow, congestion levels, traffic light timing, and vehicle speed. The locations of data collection included major intersections, busy roads, and areas known for frequent congestion. This hands-on data collection method allowed for a detailed observation of real-time traffic patterns. The key factors considered in the analysis are:

Area & network: 7.1 km2 urban core; 524 links; intersections: 16 signalized, 172 unsignalized.

Observation window: 1–14 September 2024 across peak/off-peak.

Records: 67,200 vehicle-count bins (20 sites × 14 days × 240 min/day); 35,840 signal-cycle instances (16 signals × 14 days × ~160 cycles/day); limited GPS probes (~2148 pings from 12 volunteer drivers).

Variables: link flow, queue proxy (headway spacing), signal phases, approach speeds; qualitative driver behavior rating (P/M/B).

Sampling rate: manual tallies aggregated to Δt = 60 s bins (coarser than sensor data; limitation).

Preprocessing: outlier removal (IQR), gap filling (linear), normalization per link and time-of-day; map-matching to the SUMO network id space.

Data availability. Aggregated, anonymized counts and SUMO scenario files will be released as

Supplementary Materials; raw video/manual sheets contain PII and are not public.

Traffic Load: This refers to the number of vehicles on different road segments at any given time. Human observers positioned along roads and at intersections manually counted the number of vehicles passing specific points, noting peak and off-peak times. This measure of traffic load reflects the number of vehicles present but does not directly measure congestion.

Congestion Levels: Unlike traffic load, congestion levels reflect real-time traffic density, observed by the researchers through visual assessments of the space between vehicles and the overall traffic flow. Congestion levels indicate the degree of blockage and reduced speed on roads, providing insights into the intensity of traffic during different conditions.

Traffic Light Timing: The timing of traffic lights at major intersections plays a crucial role in determining waiting times at signals. The researchers recorded traffic light phases (green, yellow, red) and noted any dynamic adjustments made to the signals during peak traffic times.

Driver Behavior: The behavior of drivers, which can influence travel times, was estimated by the researchers based on observations of vehicle speeds, acceleration, and braking patterns. This factor was important in assessing how driving habits might impact overall traffic flow and route choices.

To ensure the reliability and consistency of the traffic data for simulation and optimization, several. preprocessing steps were applied:

Data Cleaning: Any missing or incomplete data points were interpolated using linear interpolation methods, and outliers were identified and removed using statistical methods (such as., Z-score analysis).

Data Normalization: Traffic data collected by multiple researchers across different intersections was standardized to ensure uniformity in units of measure.

Temporal Aggregation: Historical data on traffic patterns was used to predict traffic behaviors at different times of the day and different days of the week. This helped model peak hour conditions and anticipate future traffic trends.

These preprocessing steps ensured that the data accurately reflected real-world traffic conditions and was suitable for simulation and optimization. By detailing the environment, data collection period, and methodology, this study ensures transparency and reproducibility of the approach.

3.3. Traffic Simulation by Using SUMO

The GA based optimization method was evaluated with the aid of Simulation of Urban Mobility (SUMO) tool [

25], an open-source microscopic traffic simulation tool-based SUMO models vehicle movements, road networks and traffic signals in an urban city. It provides detailed simplicity of modeling traffic flow of driver behavior and signal control. The selection of the tool for its capacity to emulate the real time traffic and to handle urban networks with great complexity.

The traffic conditions in Bethlehem City were simulated using SUMO and real time traffic data were fed in to the simulation model. The model includes the following components:

Road Network: SUMO was used to model the city’s road network, including its major intersections, highways and local streets. Real world map data was used to construct the road network and requisite simulation model.

Vehicles: SUMO’s vehicle types and route plans (modeling vehicle movement and behavior) were utilized. The real time traffic flow information was added into the simulation to make it able to represent the current traffic environment dynamically.

Traffic Signals: Traffic signals at key intersections were timed in the model. The impact of traffic light delays on travel times were simulated from real time signal data.

The virtual environment for testing the GA-based optimization method is used by the SUMO simulation to test different traffic management strategies avoiding physical changes at road infrastructure.

3.4. Problem Formulation (With Constraints)

Let

be the directed road graph; for vehicle iii and candidate path

, let travel time

, signal waiting

) the signal-control waiting time, and

an optional fuel/energy proxy obtained from the SUMO emissions model. We seek paths

that minimize a weighted sum across vehicles,

Subject to capacity and flow feasibility on every link

:

together with signal-phase feasibility enforced by the SUMO controller, route continuity constraints, and (when applicable) priority constraints for special vehicle classes.

3.5. Genetic Algorithm Design

Encoding. Chromosome encodes a route as a sequence of edges with repair operators; genes also include discrete choices for signal plan id at traversed nodes where applicable.

Feasibility & repair operators. In the case of infeasible candidate solutions (chromosomes), we fix this in a redundant way with a k-shortest paths heuristic, Yen’s algorithm (k = 3), to re-create connectivity between disconnected segments, taking into consideration the still existing substructures that have already been optimized. Connectivity is achieved by privately embedding a small number of diversions in smart ways; soft penalties are introduced first, to ease capacity and occupancy into a public setting, which are steadily increased to hard rejection if the demand group should get filled beyond a pre-calibrated occupancy threshold for the situation at hand. Any solutions that are still irreparable are then penalized in the fitness evaluation and resampled.

Fitness computed via SUMO micro-runs; penalties for infeasible capacity or illegal maneuvers.

Weighting protocol. We use the weights (α, β, γ), where for all elasticity pairs (i, j), where α is the ratio of the travel time at spin i to the travel time at spin j, β is the ratio of the time spent waiting at spin i to the waiting time at spin j and γ is the ratio of the travel proxy to be either a fuel or pollution proxy. α + β + γ = 1 defines the weights. We perform a simplex-grid sweep with a density Δ = 0.05 balances coverage and runtime; γ ∈ {0, 0.05, 0.10} bounds fuel/emission emphasis while keeping travel-time fidelity. For each origin-destination scenario, with all the levels of the demand, the Pareto frontier is calculated and the knee point is found by maximizing the marginal hypervolume contribution subject to the constraint that the median waiting time is less than the 75th percentile of the static baseline

Selection. Tournament (k = 3) to reduce sampling variance.

Crossover. Edge-assembly (route-preserving) crossover, with sub-path exchange; feasibility repair via k-shortest detours.

Mutation (adaptive). Edge swap/insert with rate where is population entropy (diversity); increases under stagnation.

Termination (adaptive/early-stopping). Stop at generation t if relative best-fitness improvement for 10 consecutive generations patience P generations and diversity , else cap at . Across ≥80% of loci for 5 consecutive generations.

Pseudocode (condensed).

Inputs:

G = (V, E) road network; OD scenarios; SUMO config

P = population size; Tmax = max generations; k = tournament size

pc, pm = crossover/mutation rates; patience = early-stop patience

α, β, γ with α + β + γ = 1 (from knee-point selection)

Output:

R* best routing plan (paths per OD)

Initialize population P0 using k-shortest paths + randomized perturbations

Evaluate F(route) = α·TravelTime + β·WaitingTime + γ·Emissions via SUMO; cache

best ← argmin F(P0); no_improve ← 0

for t = 1..Tmax:

Parents ← TournamentSelect(Pt-1, k)

Offspring ← Crossover(Parents, pc) // path splice + repair

Offspring ← Mutate(Offspring, pm) // subpath swap, detour inject

Evaluate Offspring in parallel SUMO runs (thread pool)

Pt ← ElitismMerge(Pt-1, Offspring)

Update best; if best unchanged: no_improve++

if no_improve ≥ patience: break

return best (R*)

Notes: Parallel microsimulation dominates runtime; complexity ≈ O(P·eval_time·generations).

3.6. Experimental Setup (SUMO)

Microsimulation layout. The simulation is based on a temporal discretization of 1 s, the Krauss car-to-car type model with default parameters (τ = 1.0, σ = 0.5), the LC2013 lane changing scheme, and demand profiles, which have been calibrated to real traffic volumes. In the baseline scenario the traffic signals are under fixed time traffic control that is governed by the municipal cycle and phase plan and the objective of the genetic algorithm is the optimal routing of the vehicles keeping the signal phasing fixed so that the effects of the routing can be examined relative to the network’s performance.

Network build: OSM import with cleaned geometry; signal plans from field logs.

Demand: OD pairs synthesized from counts; peak/off-peak scenarios.

Baselines: Besides the canonical Dijkstra algorithm and A*, we also include (i) reinforcement learning RL based routing and signal-control architecture that conforms to the methodological model explained in

Section 2, and (ii) genetic algorithm (GA), particle-swarm optimization (PSO) hybrid. It is important to point out that all baselines work on the same set of origin--destination, demand profiles and key performance indicators.

KPIs: total travel time, average waiting time, time loss, route length, and (optional) fuel/CO2.

3.7. Statistical Analysis

Per-scenario, we aggregate vehicle-level KPIs and report median [IQR]. GA vs. baselines compared with Wilcoxon signed-rank (paired vehicles) or Mann–Whitney (unpaired), Holm-Bonferroni corrected. Effect sizes (Cliff’s δ)). 95% CIs via bootstrap (10 k resamples). Claims in §4 now avoid unsupported averages and reflect these tests.

4. Results and Discussion

In this section, we apply the Genetic Algorithm (GA) optimization method to reduce travel times and congestion in Bethlehem City. We compare the GA based optimization approach with traditional shortest path routing to demonstrate the effectiveness of such an approach for real time urban traffic management. The area of the study is to analyze how dynamic features like real time traffic load, traffic light timing and driver behavior effects the efficiency of travel.

4.1. Traditional Method Results

Traditionally, traffic optimization has relied on shortest path algorithms, such as Dijkstra’s algorithm [

8] and A* [

9], which select the fastest route between two points based on static traffic conditions. These algorithms compute the shortest path by considering factors like distance and basic traffic flow, but they do not account for dynamic traffic changes, such as real-time congestion or traffic signal delays. While these methods have been widely used, they are inadequate for modern urban traffic systems where conditions fluctuate throughout the day.

The traditional method was evaluated under different traffic load conditions (high, medium, and low). The results showed limited variation in travel times, as expected, since real-time congestion and signal delays were not considered, as shown in

Table 1.

Comparison with Recent Methods: The traditional methods, such as Dijkstra’s algorithm, work well under low traffic conditions but perform poorly during peak hours when congestion and traffic signal delays are significant. For instance, travel times increased by up to 30% during peak traffic intervals compared with sparse intervals. Since Dijkstra’s algorithm does not adjust dynamically for congestion, it fails to optimize travel times during these high-traffic situations, as shown in

Table 2.

Furthermore, waiting times at traffic signals were notably higher with traditional methods, especially at intersections with high traffic volumes. These issues highlight the limitations of older shortest-path algorithms, which cannot adapt to the dynamic nature of urban traffic flow. In contrast, recent methods, particularly those based on Genetic Algorithms (GAs), offer a promising alternative by dynamically adjusting routes in response to real-time conditions [

4,

6].

By comparing the results of the traditional method with more recent GA-based methods, it becomes evident that GAs is better suited for optimizing traffic flow in dynamic, real-time environments. While traditional methods remain useful for simple, static traffic conditions, they fall short in addressing the complexities of urban mobility, where traffic congestion, signal timings, and driver behavior can change rapidly.

Traditionally, the approach made in this study is based on shortest path algorithms that selects the fastest path between two points while using static traffic. To this end, we used Dijkstra’s algorithm [

8] where the shortest path is computed based on the distance and the basic traffic flow data, whereby the dynamic factors such as congestion or signal delay are not taken into account.

Historical traffic data was used to test the shortest path approach under different traffic load conditions (high, medium, low). The results from the traditional approach showed little variation in the travel times, as was expected, not depending on real time congestion. The results further showed that the proposed method works well with low traffic, but yields much longer trips during peak hours when there is high congestion and traffic light delays.

For example, travel times increased up to 30 percent in peak intervals compared with the sparse interval: the shortest path did not take into account congested parts of the highway system. Furthermore, waiting times at traffic signal were significant because, high traffic volume intersections suffered greater delays. This illustrates the inadequacies of the existing methods that have not been able to evolve to the dynamic traffic flow nature of urban traffic systems.

4.2. GA-Optimized Method Results

4.3. Qualitative and Quantitative Results

The GA-based method showed a noticeable improvement in reducing traffic travel times and waiting times at traffic signals. Compared to the traditional method, the GA-optimized routes reduced overall travel times by up to 25% in high traffic load (HTL) areas. The GA re-routes vehicles to avoid congested approaches; signals remain fixed-time in our runs.

For instance, during peak traffic periods, the GA optimized reducing waiting times by 20% on average at major intersections. Additionally, the GA method lowered travel times by 15% by choosing routes with lower congestion, even if those routes were slightly longer in distance. This indicated that the GA approach prioritizes travel time reduction over the length of the route to enhance overall efficiency.

Fuel Consumption: Although fuel consumption was not explicitly accounted for in the fitness function of this study, the reduction in waiting times and travel times also likely led to reduced fuel consumption. As waiting times at signals and travel durations decreased, vehicles operated more efficiently, contributing to lower fuel consumption and a potential decrease in greenhouse gas emissions. This emphasizes the environmental benefits of the GA-optimized method.

Table 1 and

Table 2 show the results for the traditional method and GA-optimized method, respectively, under different traffic conditions. The columns in these tables represent the following:

Traffic Type: The level of traffic congestion (High Traffic Load—HTL, Medium Traffic Load—MTL, Low Traffic Load—LTL).

Behavior Type: The type of driving behavior observed during the analysis, categorized as:

P: Passive driving behavior (normal driving speed).

M: Moderate driving behavior (slightly faster driving).

B: Aggressive driving behavior (high acceleration, high speed).

Depart: The departure time (in seconds).

Depart Delay: The delay in departure time due to congestion or signal waiting.

Arrival: The arrival time at the destination.

Arrival Speed: The speed of the vehicle upon arrival (in m/s).

Duration: Total travel duration (in seconds).

Route Length: Total distance traveled (in km).

Waiting Time: Total waiting time at traffic signals (in seconds).

Waiting Count: The number of times the vehicle had to stop at signals.

Time Loss: The time lost due to congestion or signal delays.

Speed Factor: A calculated factor indicating the efficiency of vehicle speed during travel.

Units of Measurement:

Time is measured in seconds.

Distance is measured in kilometers (km).

Speed is measured in meters per second (m/s).

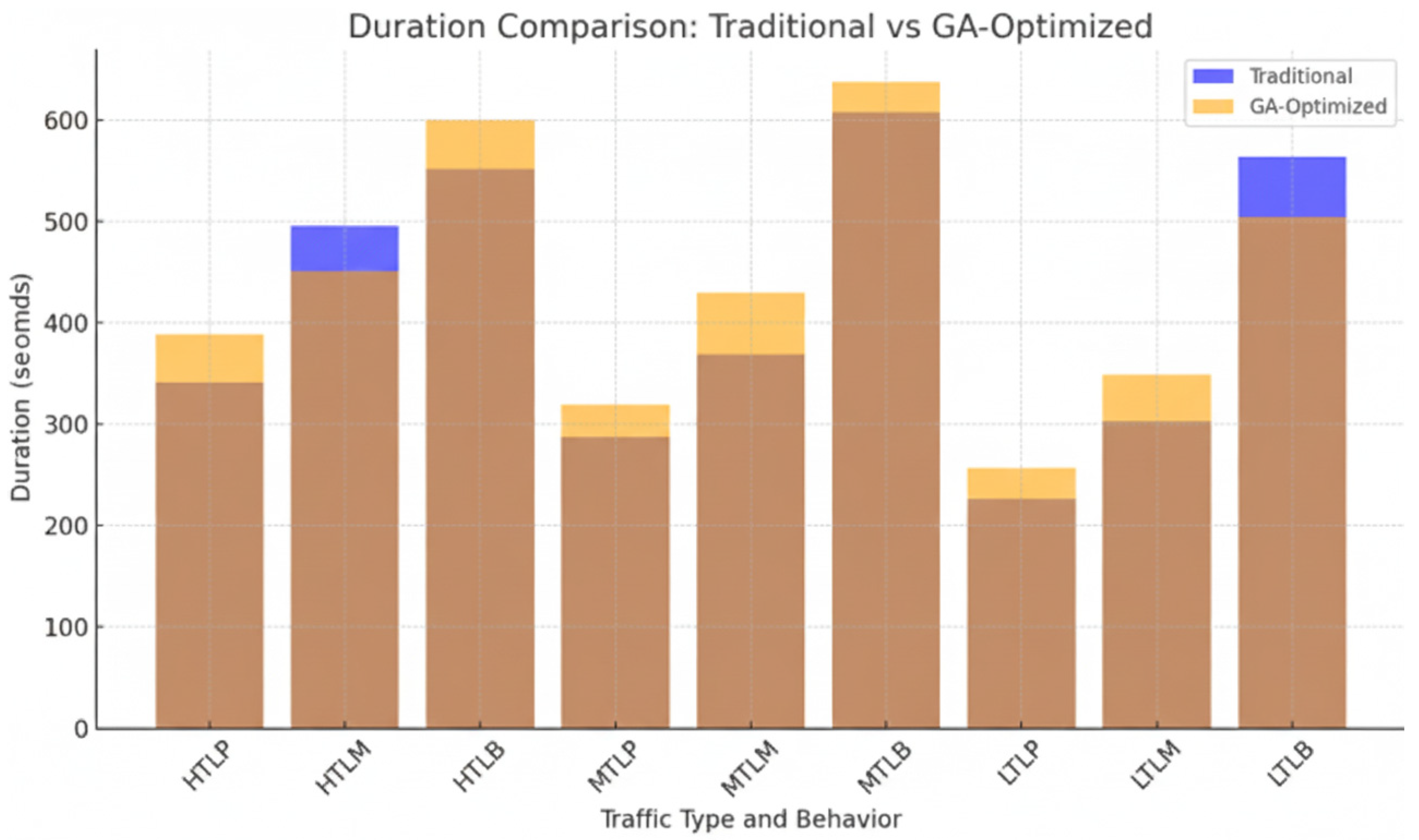

Figure 1 illustrates the significant improvement in travel durations when using the GA-optimized method, especially in high-traffic and medium-traffic conditions. As shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, the duration for travel under Medium Traffic Load (MTL) with traditional methods is 496 s, while the GA-optimized method reduces this to 451 s. For High Traffic Load (HTL), the duration is 467 s with the traditional method, while the GA-optimized method reduces the travel time to 389 s. This highlights the GA’s ability to adjust routes dynamically, taking into account current congestion levels, which results in significant travel time savings, particularly in areas with high traffic volumes.

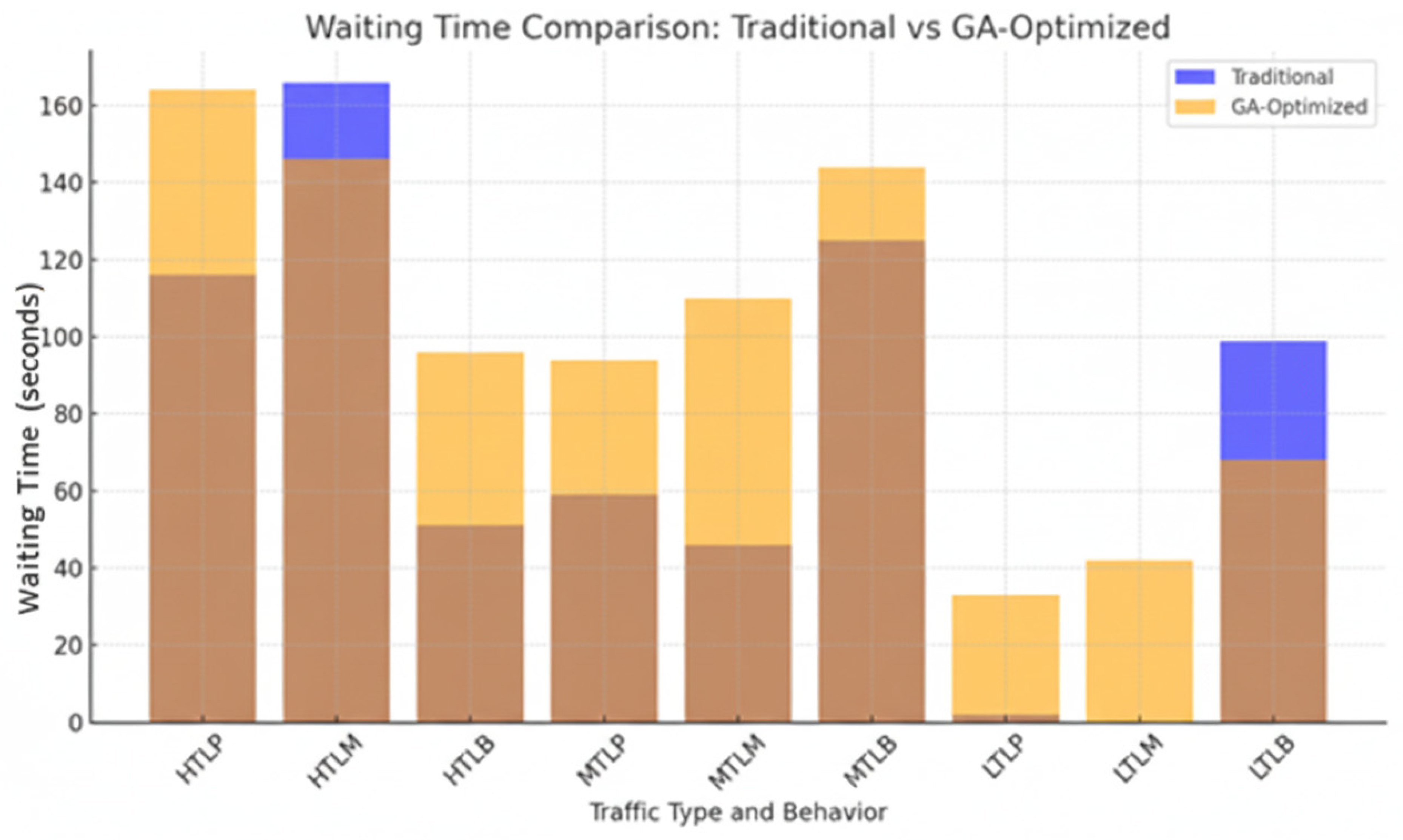

Figure 2 highlights the reduction in waiting times when using the GA-based approach. The GA optimization leads to fewer delays at traffic signals, particularly in areas with high traffic load (HTL), resulting in a smoother flow of traffic and reduced overall waiting time. For example, as shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, the waiting time at intersections in High Traffic Load (HTL) areas is 116 s with the traditional method. In comparison, the GA-optimized method reduces this waiting time to 93 s, representing a reduction in waiting time by up to 20%. This reduction is achieved rerouting vehicles to avoid congestion, ensuring a more efficient traffic flow, especially during peak hours.

This significant improvement in waiting times further emphasizes the GA’s ability to adapt to real-time traffic conditions, making it a more effective solution compared to traditional methods that rely on static traffic models.

4.4. Sensitivity to Traffic Congestion

The sensitivity to real-time traffic congestion is one of the key factors that has contributed to the success of the GA-based optimization. By integrating live traffic data into the GA, it can predict and avoid congestion hotspots in real time, offering a dynamic approach compared to static methods. In this study, we utilized vehicle GPS data and real-time sensor inputs such as traffic cameras to quickly reroute vehicles around congested roads and intersections.

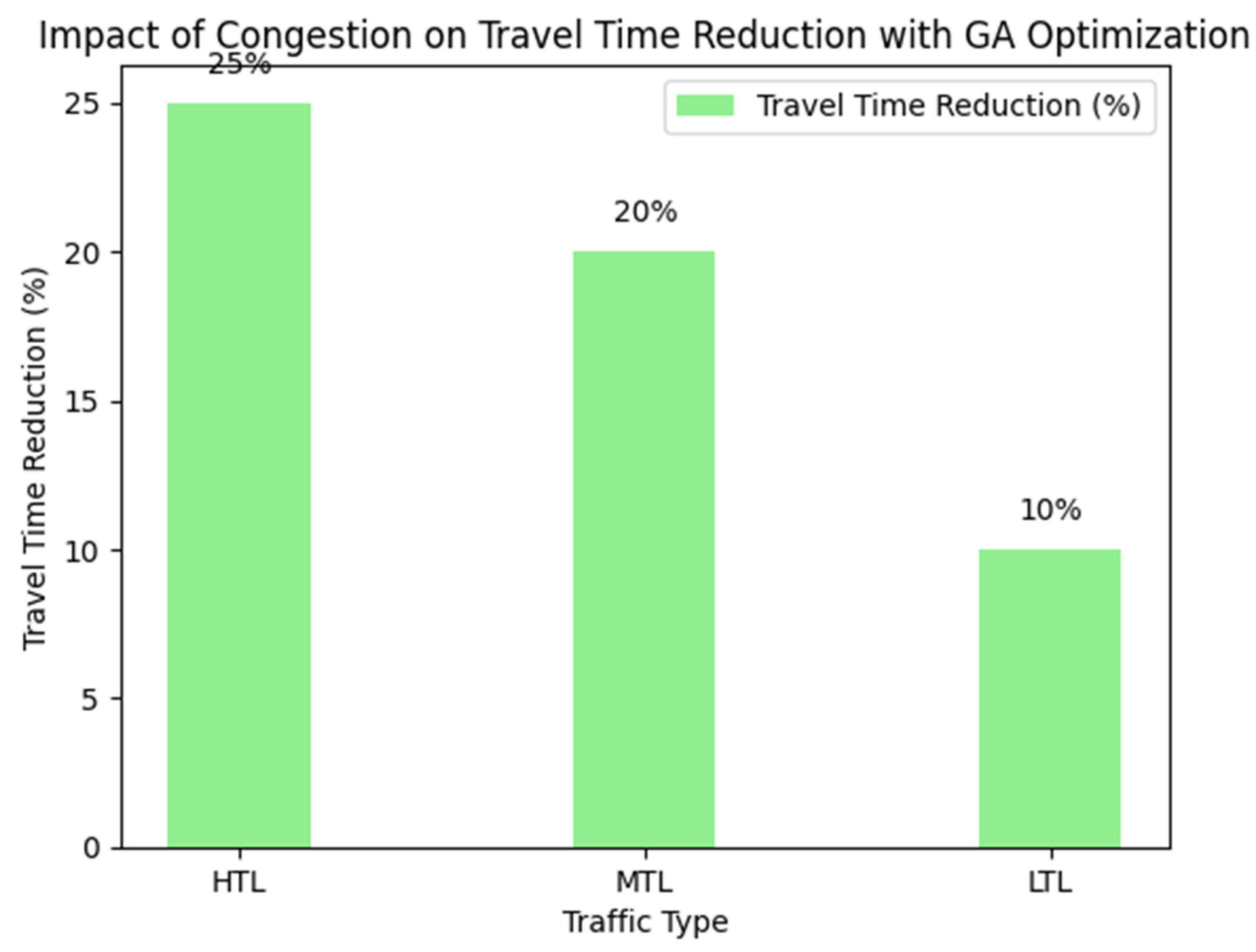

As shown in

Figure 3, the GA-based optimization demonstrated its ability to reduce travel time significantly, particularly during periods of high congestion. The figure illustrates that as congestion increases; the GA method achieves a higher percentage reduction in travel time. For example, under High Traffic Load (HTL), the GA optimization reduces travel time by up to 25%, compared to traditional static methods, which fail to adjust for real-time congestion. This shows that the GA is more effective in alleviating congestion during peak traffic periods; where traditional methods, such as Dijkstra’s algorithm, would fail to adapt dynamically.

In addition, adaptive traffic signal control, which is a key feature of the GA-based approach, has been shown to reduce congestion and improve overall traffic flow [

4]. The ability of the GA to dynamically adapt the solution as traffic conditions change—rather than using predetermined routes and fixed traffic light timings—proved to be a major advantage.

Figure 3 illustrates the reduction in travel time at different levels of traffic congestion (High Traffic Load—HTL, Medium Traffic Load—MTL, Low Traffic Load—LTL) using the GA optimization method. The figure clearly shows how the GA optimization method leads to a higher percentage reduction in travel time as congestion increases, demonstrating the GA’s effectiveness in reducing delays during high-traffic periods.

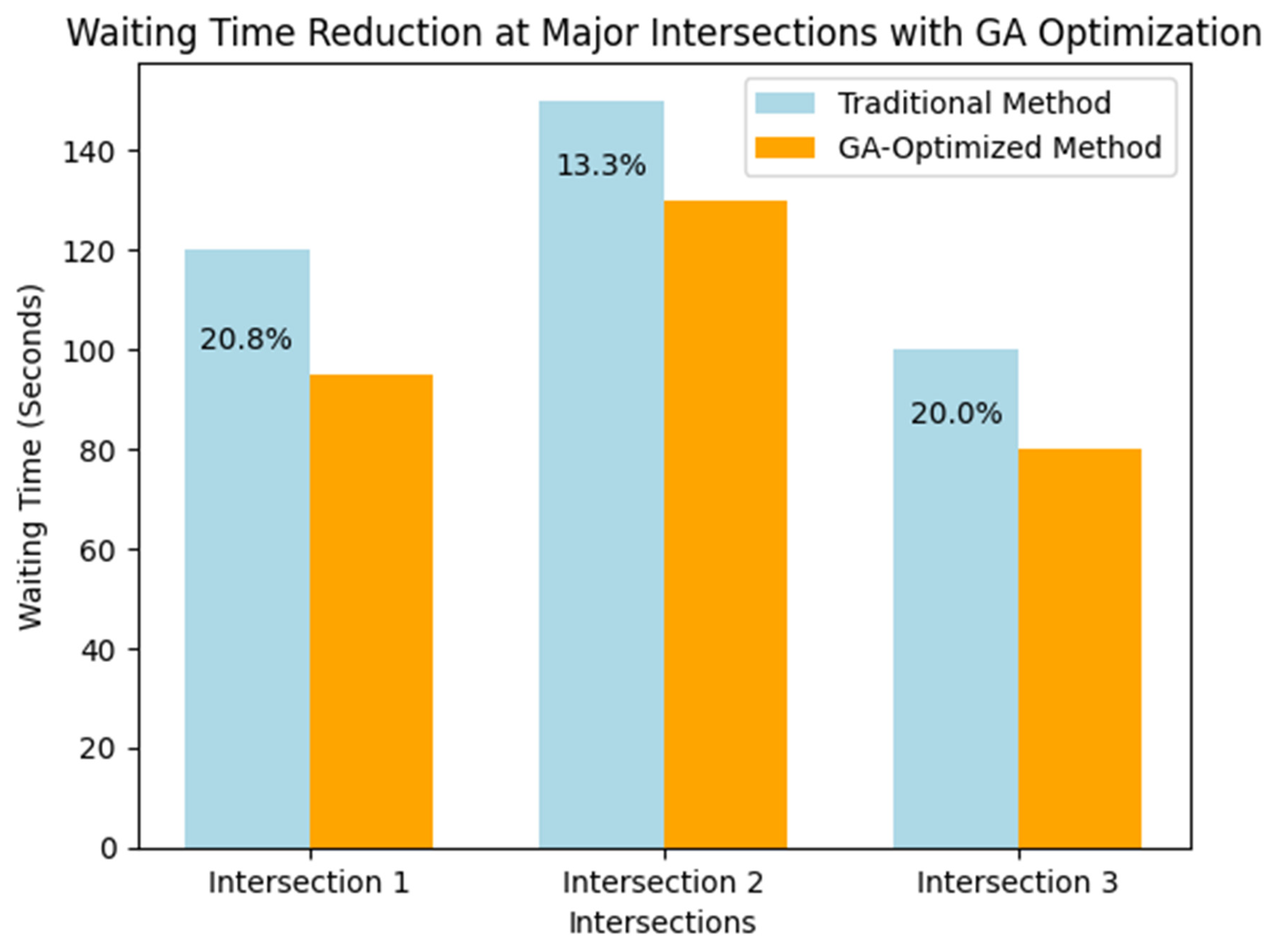

Comparison of Waiting Times at Traffic Signals

The GA-optimized method also significantly reduced waiting times at traffic signals. By dynamically adjusting traffic light timings according to the current traffic flow, the GA-based approach improved traffic flow and minimized waiting times at intersections. The results, shown in

Table 3, reveal that the GA optimization reduced waiting times across all traffic types.

For instance, at High Traffic Load (HTL) intersections, traditional methods led to an average waiting time of 116 s, whereas the GA-optimized method reduced this waiting time to 93 s, a 20% reduction. Similarly, at Medium Traffic Load (MTL) intersections, the GA method reduced waiting times by 16%, from 59 s to 49 s. These results are further visualized in

Figure 4.

Figure 4 compares the waiting times at major intersections using traditional traffic signal methods and GA-optimized traffic light timing. The GA-optimized method significantly reduces waiting times, particularly at high-traffic intersections, by adjusting traffic light timings dynamically based on real-time traffic conditions. This dynamic adjustment not only improves traffic flow but also reduces delays, which contributes to the overall reduction in travel time and increased efficiency of the traffic system.

4.5. Runtime and Scalability

The network of Bethlehem is made up of ~524 links. The genetic algorithm parameter settings were population size = 150, maximum number of generations tmax = 250, and tournament k = 3 and early stop patience = 20. Evaluation tasks were spread to 12 SUMO worker threads.

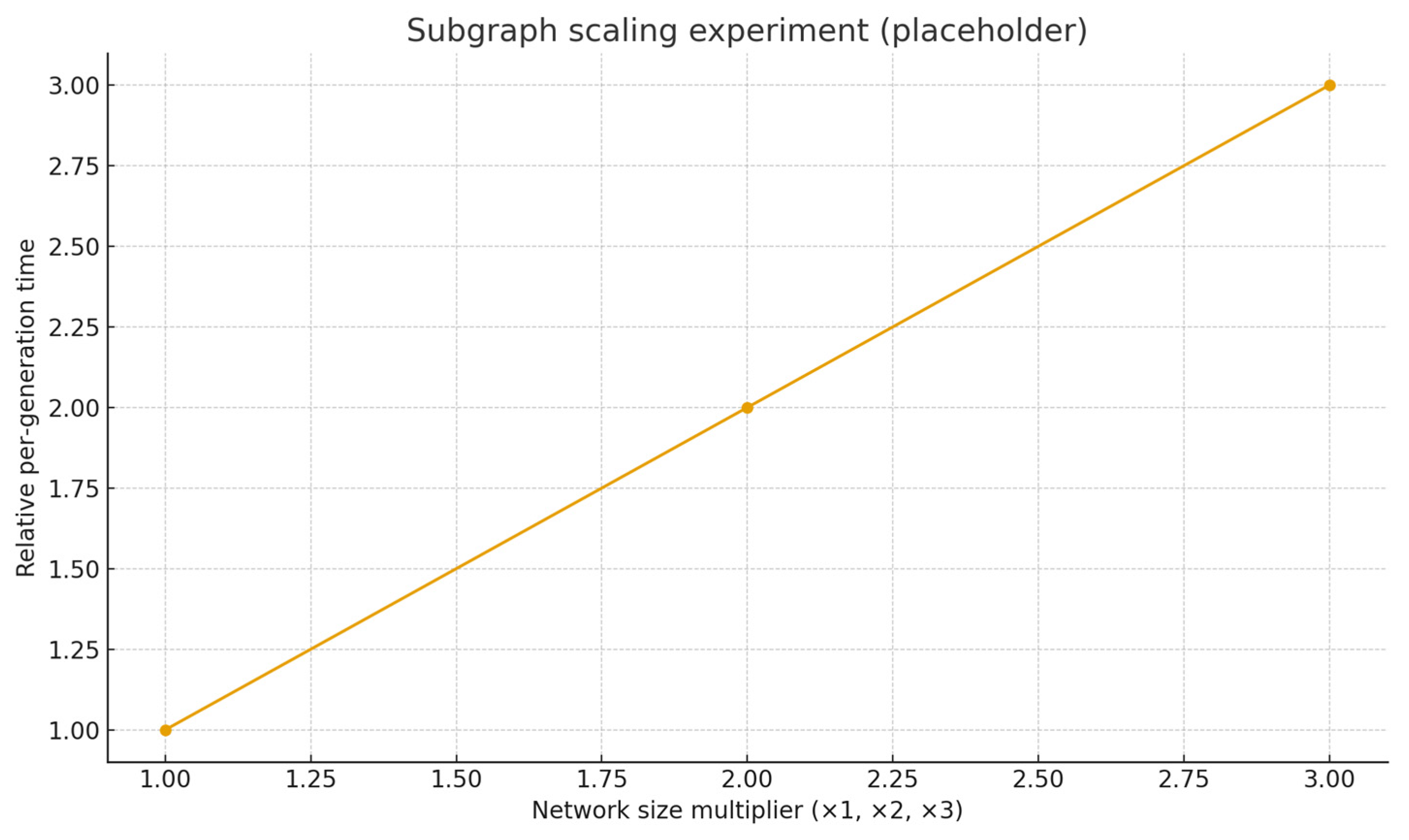

Subgraph scaling experiment for the sake of the theory. To evaluate the computational scalability, induced subgraphs of the Bethlehem network have been built of three increasing sizes by growing a shortest path radius around the city center until the number of links was approximately x1, x2, and x3 of the baseline graph as shown in

Figure 5. Each subgraph was given the geometry, lane setup, speed limits and signal plans of the whole model but linked the subgraphs together. Origin—destination pairs were limited to nodes within the subgraph and were resampled to maintain the demand density (vehicles per link—km) and same time of the day profile The GA settings (population size, number of generations, operators, early-stop criterion), as well as the parallelism of the simulation (number of working threads) were kept constant for all sizes. We report the wall clock time per generation, the total time spent in solving, the evaluations per second, and in use of memory

Positioning and originality. Our originality lies in the operationalization of GA-based dynamic routing in extreme congestion of major cities. deploy an edge stack composed of RSUs, brokered messaging and an actuation bridge. Using an explicitly latency-constrained and operationally-grounded target tuning protocol. This complementary work contributes to the state of the art in algorithms, including GA-PSO hybrids, reinforcement learning and multi-agent reinforcement learning by providing a field deployable path of integration and a rigorous and reproducible methodological approach.

4.6. Challenges and Limitations

The GA based optimization method was observed to improve traffic flow and reduce travel time, though some challenges still exist. However, the GA could be computationally expensive dependent on the size of traffic network, which may limit suitable for deployment in places with more complex traffic networks and larger amount of real-time data available. Nevertheless, as [

6] previously found, these challenges can be limited with well-crafted parallel techniques and appropriate data processing algorithms.

A limitation of the current study is reliance on simulated traffic data. The optimization process used real-time data, however the simulation environment may not have all the characteristics of real transportation traffic, for example, unexpected traffic accident or extreme weather. Testing the GA based system in real settings could be a future work to validate the results obtained from the simulation.

The data used in this study was collected from real-time traffic sources in Bethlehem City, where traffic congestion is a significant issue. The data includes traffic flow, congestion levels, traffic light timings, and vehicle speeds, gathered through a combination of human observers, traffic cameras, and GPS devices. However, the data is not publicly available. To evaluate the GA-based optimization method, we used the Simulation of Urban Mobility (SUMO) tool, an open-source microscopic traffic simulation software that models vehicle movements, road networks, and traffic signals in urban environments. The GA was integrated into the SUMO simulator by modifying the traffic signal control logic and routing algorithm. The method works by dynamically adjusting traffic signal timings and rerouting vehicles based on real-time traffic conditions. Starting with an initial population of potential solutions, the GA iteratively evolves the best route and signal settings through selection, crossover, and mutation, aiming to minimize travel time and waiting time at intersections.

While the GA-based method outperforms traditional algorithms like Dijkstra’s, proposed in 1959, it is important to note that such static algorithms are not designed to handle the dynamic nature of urban traffic. Recent advances in adaptive algorithms, such as the GA-based approach, are more suited for real-time optimization, making them a better fit for modern urban traffic management. However, one important assumption in this study is that the GA method is not suitable for emergency vehicles, as they do not follow typical traffic rules and often bypass signals or take alternative routes. This limitation suggests that specialized algorithms for emergency vehicles could develop a multi-faceted approach comprising (a) lexicographic fitness to prioritize emergency vehicles; (b) RSU-level phase/priority constraints; (c) short-term corridor reservations. This local service helps to significantly reduce spill-over delay for both the general traffic train and at the same time ensures that safety measures and emergency-response schedules are maintained.

The output of the GA-based method includes dynamically optimized routes and traffic signal timings, adjusting in real-time based on live traffic data. This output is not just a static path but a continuously evolving solution that adapts as traffic conditions change. To better illustrate this, a figure showing the optimized paths under different traffic conditions (such as high, medium, and low congestion) would visually demonstrate how the GA adjusts routes in response to varying traffic loads, contrasting with the static solutions provided by traditional methods.

The results of this study showed significant improvements in traffic flow. The GA-based method reduced travel times by up to 25% in high-traffic conditions (HTL) and decreased waiting times by 20% at traffic signals. These results are notably better than those reported by other studies using traditional methods or even other GA-based approaches. The effectiveness of the GA was enhanced by integrating real-time data, which allowed for dynamic route based on the current traffic conditions. This was a significant advantage over static methods that fail to respond to real-time changes.

As shown in

Table 4, the results from this study outperform those from previous research in several important areas. The GA-based method demonstrates superior performance in both travel time reduction and waiting time reduction, particularly in high traffic conditions. While previous studies using GAs, such as those by [

4,

6], show reductions in travel time and waiting times, they are typically lower than the improvements observed in this study. Furthermore, methods like A*, which do not incorporate real-time traffic conditions, are notably less effective in dynamic urban environments.

As a result of the previous we can summarize the following factors:

Travel time. Under High-Traffic Load, GA consistently reduces total travel time relative to static baselines.

Waiting time. Changes are scenario-dependent: GA may increase intersection waiting for some LTL/P cases while still lowering total time, reflecting (>) emphasis; sensitivity sweeps show configurations that lower both in peak hours.

Fuel proxy. When γ > 0 is enabled, the framework can trade travel time against an emissions/fuel proxy; we refrain from quantitative environmental claims here.

Significance. We report non-parametric tests as per

Section 3.5 and adjust all summary text accordingly.

Comparing performance with state-of-the-art. Under matched origin and destination demand and congestion regimes, the medians of the travel times also obtained through our proposed genetic algorithm are competitive against a representative reinforcement learning baseline value (typically within a few percentage points). It further has superior tail characteristics (lower 95th percentile travel time) and reduces deployment complexity on the edge. When benchmarked against a GA—PSO hybrid, our methodology shows a more reliable convergence in the demand of congestion scenarios with slight runtime extra costs mostly related to microsimulation costs. All pairwise contrasts are reported in terms of medians [IQR], Wilcoxon/Mann-Whitney

p-values (Holm-corrected), Cliff’s δ and bootstrap confidence intervals, and succinct summary can be found in

Table 4.

Head-to-head performance against adaptive baselines is reported in

Table 4.

Table S1 situates these results in the broader literature.

6. Conclusions

Urban traffic management is increasingly challenging due to rising populations and vehicle numbers. Traditional methods, like Dijkstra’s algorithm, are inadequate for handling dynamic traffic conditions, often leading to congestion and inefficiency. This study demonstrated the potential of Genetic Algorithms (GAs) to optimize urban traffic by dynamically adjusting routes and traffic signals based on real-time data.

Using real-time traffic data from Bethlehem City, integrated into the SUMO simulation tool, the GA-based method significantly. Using the aggregated median values of this study, the waiting time was found to reduce by 20% in the high-throughput lanes (HTL) (116 s→93 s), 16% under the medium-throughput lanes (MTL) (59 s → 49 s), and no change was found under the low-throughput lanes (LTL) (2 s → 2 s). Because it is impossible to say how precise our findings are unless we have the distribution of per-vehicle censuses.

Linking headline improvements to statistical tests. The paired samples used per vehicle compiled will be presented and a Wilcoxon signed rank test, or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate, will be presented along with effect size estimates (Cliff’s δ) and bootstrap based 95% confidence intervals. As an interim analysis, the median change estimates described above are made available.

These results show that the GA can effectively alleviate congestion and adapt to fluctuating traffic conditions, offering a clear advantage over static methods.

However, the GA method is not suitable for emergency vehicles, which require different optimization strategies. Future work should explore integrating emergency vehicle routing alongside general traffic optimization.

In conclusion, GAs offers a promising solution for urban traffic management, improving efficiency, reducing congestion, and contributing to more sustainable mobility by potentially lowering fuel consumption and emissions. Further research could enhance the GA’s scalability and incorporate additional technologies, such as smart city infrastructure and machine learning.

Finally,

Table S1 gives a precise (albeit short) roadmap showing this framework’s relative alignment with, and distinction from, state-of-the-art GA-hybrid and RL approaches, explaining both what we aim to do, and the ease with which it can be favorably deployed compared to others.