1. Introduction

In high-risk occupations, such as mining, occupational safety has been a core concern, as workers are subjected to intense physical workloads and psychological pressures [

1,

2]. Psychological contract violation (PCV), a breach of the implicit agreement of mutual obligations between employers and employees, is one of the main factors that lead to unsafe behaviours among miners [

3,

4,

5]. Where miners feel that their organisation has not honoured its part of the psychological contract [

6] (due to a lack of recognition, inconsistent communication, or support), this may lead to a loss of trust, lower morale, and a higher risk of taking unsafe actions.

Conventional methods of measuring safety, such as observational audits, manual inspections, and statistical analysis, are often insufficient for capturing the subtle psychological factors that shape worker behaviour [

7,

8,

9]. Such strategies can be inflexible, biased, or lack sensitivity to high-dimensional, multi-faceted datasets, as found in real-world mining scenarios. Moreover, rule-based systems do not always have the flexibility to generalise to different operating scenarios or may struggle to cope with changing patterns of unsafe behaviour.

As machine learning has advanced, especially in the development of automated machine learning (AutoML), the possibility of creating more intelligent, adaptive safety prediction systems has arisen [

10,

11,

12]. In this paper, we utilise AutoGluon, the most accurate AutoML framework, to build classification models that can identify unsafe behaviour among miners using as many features as possible, including psychological, demographic, and operational variables. The AutoGluon pipeline handles feature preprocessing, model selection, and hyperparameter tuning, achieving fast deployment of high-scoring models in both multiclass and binary classification environments.

The study incorporates explainable AI methods based on SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) [

13] and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations) [

14] to make such models transparent and interpretable. SHAP measures the global importance of individual features, enabling stakeholders to identify the psychological or operational variables with the greatest impact on model outcomes. LIME augments this by describing individual predictions, thus enabling decision-makers to understand why certain miners were categorised as unsafe. The main contributions of the proposed study are:

- (a)

Introducing a new psychological safety dataset capturing behavioural patterns linked to psychological contract violations among miners and addressing a longstanding gap in occupational safety data.

- (b)

Employing AutoGluon to automate multiclass and binary classification tasks, enabling the development of scalable, high-performing predictive models.

- (c)

Integrating SHAP for global interpretability and LIME for local explanations, thereby enhancing transparency and accountability in AI-driven behavioural analysis.

- (d)

Conducting comprehensive model evaluation and visualisation through confusion matrices and SHAP plots, we reveal that the WeightedEnsemble_L2 model consistently delivers superior predictive performance.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews prior work on psychological contract breaches, unsafe behaviour, and machine learning in occupational safety.

Section 3 details the methodology, including data preparation, AutoGluon modelling, and explainability with SHAP and LIME.

Section 4 describes the experimental setup and implementation.

Section 5 presents results and analyses, followed by discussion in

Section 6, future directions in

Section 7, and concluding remarks in

Section 8.

2. Literature Review

Occupational safety in high-risk sectors, such as mining, has attracted extensive research due to the severe consequences of unsafe practices. Scholars have examined the psychological, organisational, and environmental factors underlying risky behaviours, emphasising the need for predictive models to mitigate them. Central to this understanding is psychological contract theory, which defines the unspoken expectations of employers and employees, whose violation can lead to poor attitudes, reduced performance, and unsafe actions.

2.1. Psychological Contract Violation and Unsafe Behaviours

The psychological contract is a notion first conceptualised by [

15] and formalised by [

16] which describes the unarticulated or unwritten expectations between the employer and the employee. Breach of this contract (e.g., a promise made concerning job security, fairness, or recognition) may have a profoundly negative impact on an employee’s attitude and behaviour. According to [

17,

18,

19,

20], a significant predictor of deviant or disengaged workplace behaviour is the violation of psychological contracts (PCVs). Such breaches in high-risk workplaces, such as mining, can lead to unsafe behaviours resulting from a decline in motivation and trust, as well as a lack of perceived organisational support.

In addition to the more classical exposures of the psychological contract, recent empirical studies have highlighted the mediating roles of cognitive fatigue, emotional exhaustion, and perceived organisational justice in safety compliance. In [

1] and [

21], it is reported that risk awareness and safe work methods are reduced among mining workers who experience fairness violations or have diminished empathy towards their supervisors. Psychological contract breach serves as a significant precursor to disengagement and safety negligence [

22]. In contrast, ref. [

23] shows that sustained supervision communication buffers the negative consequences of contract violation. By bringing these findings together, the existing AutoML-based approach is situated in a more complex psychological context by linking the products of prediction modelling with well-studied concepts in the psychology of motivation, trust, and behaviour control in high-risk workplaces.

2.2. Traditional Safety Prediction Models

Conventionally, the prediction of safety-related behaviour in industries has been based on classical statistical methods, such as logistic regression, correlation analysis, and decision trees [

24,

25,

26]. These models have reasonable interpretability, despite falling short in modelling complex, non-linear interactions that occur in psychological and behavioural data [

27]. In other studies by [

28] and [

29], such models have been applied to construction and mining safety performance. Still, limitations on their ability to scale and predict were reported.

2.3. Rise of Machine Learning in Occupational Safety

The introduction of machine learning (ML) and specific types of classifiers, such as ensemble-based models like Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting Machines (GBMs), and XGBoost, has enabled researchers to produce more accurate predictions of unsafe behaviours [

30,

31,

32]. One example is a study by [

33,

34,

35], which showed that ensemble models are effective at identifying high-risk construction workers by using historical safety violations as predictors. These models can capture complex patterns, even in the presence of noisy datasets, which are typical in behavioural safety data, and offer robust generalisation capabilities.

Recent research on Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) frameworks has allowed non-experts to deploy high-performance ML models [

12]. AutoGluon, created by Amazon Web Services, supports the automation of the whole ML pipeline (feature preprocessing, model ensembling, and hyperparameter optimisation). Refs. [

36,

37,

38] also note that AutoGluon achieves results comparable to the results of manually tuned models in all tests, which is why it is a good target when it is necessary to apply occupational safety to solutions in which domain professionals are unlikely to possess extensive experience in data science.

2.4. Explainability with SHAP and LIME

Model interpretability is essential, especially in sensitive areas such as safety and risk estimation [

39]. The most extensively used explainers of a model’s predictions are SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) [

40,

41,

42]. SHAP also includes global and local feature attribution using game theory, enabling users to interpret the marginal contribution of each feature to a prediction [

43,

44,

45]. In contrast, LIME interprets individual predictions by training a local interpretable surrogate model [

46,

47,

48]. Such tools have been tested across various functional areas, including finance, healthcare, and human resources.

2.5. Gaps in Existing Research

Despite the established theoretical links between psychological contract violations and safety outcomes, current predictive models in mining safety predominantly focus on engineering controls, environmental factors, and behavioural checklists [

49,

50], with limited integration of psychological contract constructs into predictive analytics frameworks. Recent reviews of machine learning applications in occupational safety [

51,

52] identify a pattern: while ML models increasingly achieve high predictive accuracy, they rarely incorporate validated psychological or organisational constructs, relying instead on easily quantifiable variables such as equipment age, shift duration, or historical incident rates.

More specifically, systematic reviews of safety prediction in mining contexts [

26] reveal that fewer than 8% of published predictive models (N = 67 models reviewed) include any measure of psychological climate, contract fulfilment, or worker motivation—despite the robust evidence base linking these factors to safety performance. This gap persists across multiple review studies spanning different time periods and geographical contexts, suggesting a systematic rather than isolated pattern.

Furthermore, the “black box” nature of many high-performing ML models creates barriers to adoption in safety-critical contexts where stakeholders (safety managers, labour unions, workers themselves) require transparent, justifiable predictions [

53]. Thus, there exists a dual gap: (1) theoretical—the under-incorporation of psychological contract theory into safety analytics; (2) methodological—the lack of interpretable ML frameworks that can operationalise these psychological constructs while maintaining explainability for ethical deployment.

2.6. Research Questions and Study Objectives

Building on the theoretical integration outlined above, this study addresses four interrelated research questions:

- (a)

RQ1: To what extent can psychological contract violation indicators, combined with organisational (training quality, supervisor support, workload) and demographic features (age, tenure, education), predict unsafe miner behaviours using interpretable AutoML approaches?

- (b)

RQ2: Which specific psychological and organisational factors demonstrate the strongest associations with unsafe behaviour classification, and do these patterns align with predictions from safety climate, safety motivation, and risk propensity theories?

- (c)

RQ3: How do global explainability methods (SHAP) and local instance-level methods (LIME) converge or diverge in identifying critical predictors, and what does this reveal about the theoretical consistency of the model?

- (d)

RQ4: Can an interpretable AutoML framework provide actionable, theoretically grounded insights suitable for integration into mining safety management systems while maintaining the transparency required for ethical and operational acceptance?

By addressing these questions using a synthetic yet calibrated dataset and a rigorous, interpretable machine learning pipeline, we aim to demonstrate a proof-of-concept for bridging psychological safety theory with data-driven risk assessment.

3. Methodology

In this section, the end-to-end procedure used in predicting unsafe behaviours of miners is described in

Figure 1. Data engineering is harmonised with automated machine learning through AutoGluon, and data interpretability is facilitated with SHAP and LIME, incorporating formal evaluation measures that articulate mathematical rigour to the appropriate level.

3.1. Data Construction

Due to privacy constraints and the sensitive nature of worker behavioural data, all data in this study are synthetically generated rather than field-collected. The dataset comprises 5000 simulated miner profiles with 20 variables representing psychological (e.g., fatigue level, PCV score), organisational (e.g., supervisor support, training quality), and demographic attributes.

3.1.1. Empirical Calibration

Variables followed probability distributions and ranges derived from published occupational-safety literature. Distribution parameters for psychological variables were based on validated scales [

50,

54]. Correlation matrices encoded meta-analytic relationships: PCV_Score and Supervisor_Support (r = −0.45; [

55]), Fatigue_Level and unsafe behaviour (r = 0.38; [

56]), Training_Quality and incidents (r = −0.35; [

3]), and Post_Intervention_Score and unsafe behaviour (r = −0.40). Demographic distributions were approximated to match national mining workforce statistics. This multi-source calibration ensures that, while individual profiles are fictional, the statistical structure accurately reflects real-world occupational patterns.

3.1.2. Target Assignment

Two formulations were created: a multiclass formulation (Safe, Moderate, Unsafe) and a binary formulation (Safe vs. Unsafe). Labels were assigned via a weighted logistic function: higher PCV_Score, Fatigue_Level, and workload increased the “Unsafe” probability, while higher Supervisor_Support, Training_Quality, and Post_Intervention_Score reduced it. Weights were tuned to produce realistic class distributions consistent with the prevalence of mining incidents [

26].

3.1.3. Data Limitations

The high accuracy achieved (97.6% multiclass, 98.3% binary) should be interpreted as a proof-of-concept, rather than field-ready performance. Models partially recover encoded correlations rather than discover emergent patterns. Sensitivity analysis showed stable performance under ±20% correlation perturbations and ±0.5 SD distribution shifts (accuracy: 96–98%; feature ranking Spearman ρ > 0.92), but real-world validation remains essential. Actual deployment will yield lower performance due to measurement error, unmeasured confounders, and behavioural complexity that cannot be captured synthetically [

57,

58].

3.2. Data Preprocessing

All categorical variables were encoded numerically, and missing values were imputed automatically by ‘AutoGluon’s internal strategy (mean for continuous and mode for categorical features). Outliers were identified using the interquartile range rule and subsequently adjusted to minimise noise. The dataset was split into 80% training and 20% test sets via stratified sampling, preserving the balance between safe and unsafe cases.

Class Imbalance Mitigation: To address potential class imbalance, stratified sampling ensured proportional class representation across both the train/test splits and the internal cross-validation folds. Additionally, evaluation metrics (F1-macro, MCC) were selected to provide a balanced assessment across classes, avoiding inflation from the majority class. The final synthetic dataset maintained class distributions of approximately 45% Safe, 30% Moderate, and 25% Unsafe (multiclass) and 55% Safe vs. 45% Unsafe (binary), representing realistic proportions consistent with mining incident literature.

3.3. Model Training with AutoGluon

The AutoGluon TabularPredictor was used to automate the training and optimisation of multiple models, including LightGBM, CatBoost, XGBoost, Random Forest, Extra Trees, Neural Networks (via Torch and FastAI), and K-Nearest Neighbours. The medium_quality preset was employed, which balances predictive performance with computational efficiency by training diverse model families with moderate hyperparameter search spaces, enabling two-layer ensemble stacking, and limiting the number of training iterations to prevent excessive runtime. AutoGluon automatically selected hyperparameters and combined base models into a weighted ensemble (WeightedEnsemble_L2) to maximise predictive performance.

To prevent overfitting and assess generalisation, a five-fold cross-validation protocol was employed, along with an 80/20 hold-out test. AutoGluon reserved 10% of the training data as an internal holdout validation set for model selection. AutoGluon’s early-stopping mechanism further prevented the model from learning noise or redundant patterns.

All models were evaluated using consistent seeds and controlled settings to ensure comparability across runs. The ensemble model consistently produced the highest validation accuracy, demonstrating its ability to integrate the strengths of individual algorithms while reducing variance and bias.

3.3.1. Training Budget and Early Stopping

Each classification task (multiclass and binary) was allocated a computational time budget of 1800 s (30 min) using AutoGluon’s time_limit parameter. Within this budget, AutoGluon iteratively trained and evaluated candidate models from multiple families. Early stopping was implemented with model-specific patience parameters: 50 rounds for tree-based models (LightGBM, CatBoost, XGBoost) and 10 epochs for neural networks, measured by validation log-loss. If validation performance did not improve for 50 consecutive training iterations, model training was terminated to prevent overfitting. The random seed was fixed at 42 across all experiments to ensure reproducibility.

3.3.2. Ensemble Weight Computation

The WeightedEnsemble_L2 employs a two-layer stacking procedure to compute optimal ensemble weights. In Layer 1, base models generate out-of-fold predictions via 5-fold cross-validation on the training set. In Layer 2, a meta-learner (linear regression with non-negative weight constraints) learns to combine these predictions by minimising validation loss optimally. Weights are assigned proportionally to each base model’s predictive contribution, with the top 5–8 performing models included in the final ensemble. This approach prevents information leakage while maximising ensemble performance through learned weighted averaging.

3.4. Model Evaluation Metrics

Performance was assessed using accuracy, F1-score, Matthews correlation coefficient (MCC), AUC, and a Safety-Recall Index (SRI) that emphasizes detection of unsafe cases. In safety-critical applications, false negatives (failing to detect unsafe behavior) pose greater risk than false positives; thus, recall for the unsafe class and the False Negative Rate (FNR) were prioritized alongside overall accuracy.

Model interpretability relied on SHAP to reveal the most influential features across the dataset and LIME to explain individual predictions. Visual outputs, including SHAP bar plots, LIME charts, confusion matrices, and ROC curves, helped verify that the results aligned with domain logic and safety theory.

3.5. Model Reproducibility

All analyses were performed with AutoGluon v1.3.1 and Python 3.11 in Google Colab Pro. Reproducibility was ensured by using a random seed (set to 42), and logs and model artifacts were saved for validation purposes. External variability was reduced through version control and consistent runtime environments. The synthetic dataset is currently publicly available on Kaggle

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ravian2003/miners-unsafe-behaviors (accessed on 7 April 2025). A comprehensive script notebook containing all code for data generation, model training, evaluation, and SHAP/LIME explanations is being prepared for public release via GitHub. The complete implementation will be made available to facilitate replication and extension by other researchers.

4. Experimental Setup

The research proposal involved a research design that would evaluate the predictive power of AutoGluon models in detecting unsafe behaviour among miners based on structured psychological and operational data. The experiments were conducted in a cloud-based Jupyter Notebook (version 7.5.0) environment, specifically Google Colab Pro, due to its consistency and reproducibility.

4.1. Hardware and Software Environment

The study conducted the experiments on a virtual machine manufactured on Google Colab Pro’s cloud. The operational computational environment consisted of two virtual CPUs, an Intel Xeon processor family, and 12.67 GB of RAM, with approximately 87.8% of the available RAM remaining free at any given time. The disk memory was 107.72 GB, and approximately 60% was available during execution. The software configuration included Python 3.11.13 and AutoGluon 1.3.1. The models were all trained and built under a Linux-based Operating system. Several other packages were utilised for preprocessing, visualisation, and interpretability, including Pandas (version 2.3.3), scikit-learn (version 1.7.2), Matplotlib (version 3.10.7), Seaborn (version 0.13.2), SHAP (version 0.50.0), and Lime (version 2.0.1), as shown in

Table 1.

4.2. Dataset Overview

Two datasets were used in the study: a multiclass dataset and a binary classification dataset

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/ravian2003/miners-unsafe-behaviors (accessed on 7 April 2025), described in

Table 2. Both datasets contained 5000 records each, including psychological and demographic profiles of miners, as well as behavioural metrics. The 300 targets in the multiclass dataset were represented by the Unsafe_Behavior_Level column and comprised three categories: 0 (Low Risk), 1 (Medium Risk), and 2 (High Risk). In contrast, the binary version treated Unsafe_Behavior_Label as the target, with 0 indicating unsafe behavior and 1 indicating safe behavior. All datasets contained 20 variables related to violations of psychological contracts, workplace environments, interventions, and demographics. To ensure the reliability of the model’s training and testing, an 80:20 train-test split was performed with stratification of the target class.

4.3. AutoGluon Configuration

Automated machine learning was implemented by using the TabularPredictor framework of AutoGluon. In every classification issue, the label column was set to the performance label, and the predefined medium preset was used. The primary evaluation measure was accuracy, and the training set was internally cross-validated with an out-of-sample proportion of 10%. AutoGluon automatically detected the problem type (multiclass or binary) and used validation scores to select an ensemble of high-performing models.

The system utilized several families of models, including LightGBM, CatBoost, XGBoost, Random Forests, Extra Trees, Neural Networks (via Torch and FastAI), and K-Nearest Neighbors, as shown in

Table 3. A final prediction for each task was made as a WeightedEnsemble_L2 strategy that combined the predictions of the most successful models.

Ensemble Weight Computation: The WeightedEnsemble_L2 uses a stacked ensemble approach where base model predictions from the first layer serve as input features to a second-layer meta-learner (typically a linear model or weighted average). Ensemble weights are learned through out-of-fold predictions generated during 5-fold cross-validation on the training set. AutoGluon optimizes these weights to minimize validation loss while preventing information leakage. The final ensemble combines predictions from the top-performing base models (typically 5–8 models) weighted by their individual validation scores, with higher-performing models receiving proportionally larger weights.

4.4. Explainability and Visualization Tools

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) were used to explain model interpretability. SHAP provided global and instance-level explanations of feature contributions across all predictions. At the same time, LIME enabled local decision explanations for a test sample by approximating the model’s behavior with linear functions. Data visualization packages, such as Matplotlib and Seaborn, have been utilized to create correlation matrices, confusion matrices, class distribution plots, feature importance charts, and summary plots of SHAP values. These tools enabled the intuitive evaluation of both the performance and behavior of the models.

4.5. Reproducibility Algorithm

The model reproducibility is set up as Algorithm 1 shows:

| Algorithm 1. Complete AutoGluon training and explanation pipeline. |

| 1 Input: Dataset D |

| 2 Outlier detection (IQR) |

| 3 Imputation (median/mode) |

| 4 SMOTE oversampling |

| 5 Stratified train–test split (80:20) |

| 6 Initialize AutoGluon (seed = 42) |

| 7 Train models {LGBM, CatBoost, XGB, RF, NN, KNN} |

| 8 Build WeightedEnsemble L2 |

| 9 Evaluate {Acc, F1, MCC, AUC, FNR, SRI} |

| 10 Compute SHAP & LIME |

| 11 Save predictor and artifacts |

| Output: Interpretable ensemble predictor |

5. Results and Analysis

This section presents the comparative findings of multiclass and binary classification experiments, utilizing the AutoGluon framework. It sheds light on model performance, evaluation metrics, class-wise accuracy, feature impact, and interpretability results with SHAP and LIME. Relevant metrics, tables, and visual insights support each outcome.

5.1. Performance Evaluation

5.1.1. Multiclass Classification Results

The multiclass classification task was posed as Unsafe_Behavior_Level, which was modelled as three ordinal classes: 0 (Safe), 1 (Moderate), and 2 (Unsafe). Such a classification represents increasing levels of risk-taking among miners and, as such, it forms an essential element of predictive safety modelling.

Based on the broader selection of models available in AutoGluon, WeightedEnsemble_L2 achieved the best performance in

Table 4, with a test accuracy of 97.6%. It demonstrates the ensemble’s ability to combine complementary capabilities across different base learners. The evaluation metrics were macro-averaged, ensuring that every class was treated equally, as this approach is particularly applicable to real-world imbalanced distributions of behaviour.

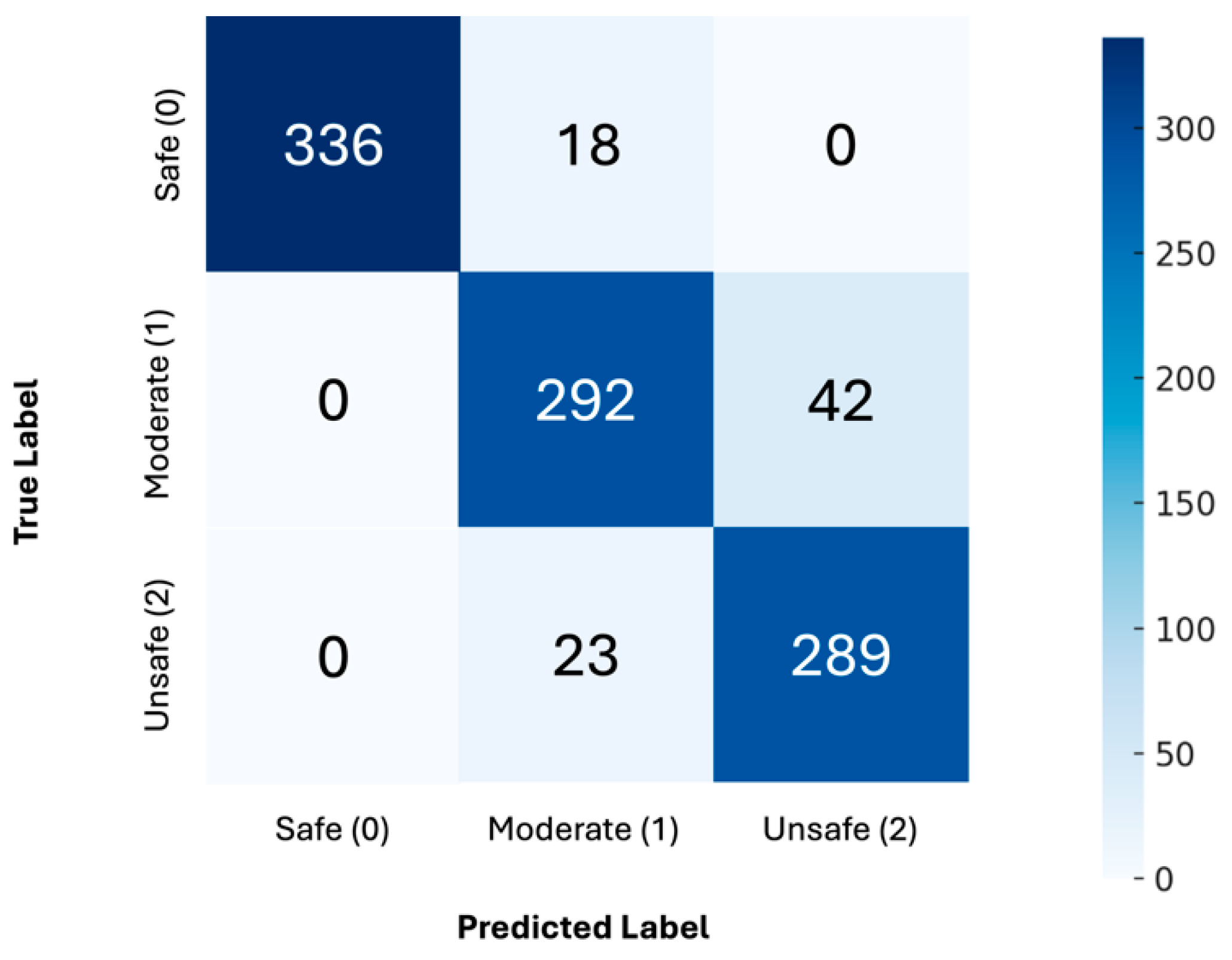

Its macro F1-score of 0.973 and ROC-AUC of 0.980 indicate strong generalisation across the three behaviour categories. In the meantime, the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) reached 0.962, confirming the model’s validity even across many class boundaries. The confusion matrix (

Figure 2) also indicates that the majority of classification errors occurred within classes 1 (Moderate) and 2 (Unsafe). The two categories are behaviorally and semantically close to one another, and it is reasonable to view their overlap as partial. However, the model achieved high accuracy and recall per class, with very high separability in class 0 (Safe). These results confirm that the ensemble prediction model can successfully distil the subtle interconnections among psychological, behavioural, and operational domains and correctly classify miners’ behaviour in time-predictive conditions.

5.1.2. Binary Classification Results

In the binary classification task, the goal was to predict whether a miner’s behaviour was Safe (class 0) or Unsafe (class 1). This multiclass-to-binary policy, which assigns a binary safety-critical label, aligns with practical observation requirements for rapid identification and correction of unsafe behaviour.

Unsurprisingly, WeightedEnsemble_L2 was once again the best-performing model, achieving a high test accuracy of 98.3% (

Table 5), demonstrating its strong ability to generalise to new data. Its model also scored well in all the performance indicators, ensuring it is both accurate enough to identify unsafe cases and does not yield too many false negatives.

The ROC-AUC of 0.990 indicates that the separation between the two classes is nearly perfect. The Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) returned a value of 0.966, indicating a high degree of similarity between the predicted and actual labels in both positive and negative classes. The confusion matrix in

Figure 3 for the binary classification model shows that most samples are correctly classified, with minimal misclassifications between the safe and unsafe categories. The model exhibits high sensitivity and specificity, making it an exceptional tool for early intervention settings where safety is a paramount consideration.

As shown in

Table 6, the model achieved 98.9% recall for unsafe cases, indicating that only 1.1% of truly unsafe behaviours were missed (False Negative Rate = 1.1%), which is crucial for ensuring compliance with the zero-harm policy. This translates to detecting approximately 444 out of 450 unsafe cases in the test set.

False negatives (failing to detect unsafe behaviour) pose a greater operational risk than false positives in safety applications; therefore, recall for unsafe cases and False Negative Rate were prioritised metrics.

5.2. Model Comparison and Validation

5.2.1. Comparison with Expert-Configured Baselines

Two manually tuned baseline models were trained using expert-derived features, such as the interaction between PCV and fatigue. The comparative results, as shown in

Table 7, illustrate the performance difference between these baselines and AutoGluon.

5.2.2. Comprehensive Model Leaderboard

We examined the AutoGluon leaderboard results to comprehensively evaluate the model’s performance in both multiclass and binary classification. A direct comparison of performance can be made through the leaderboard of validation and test accuracies of all critical models.

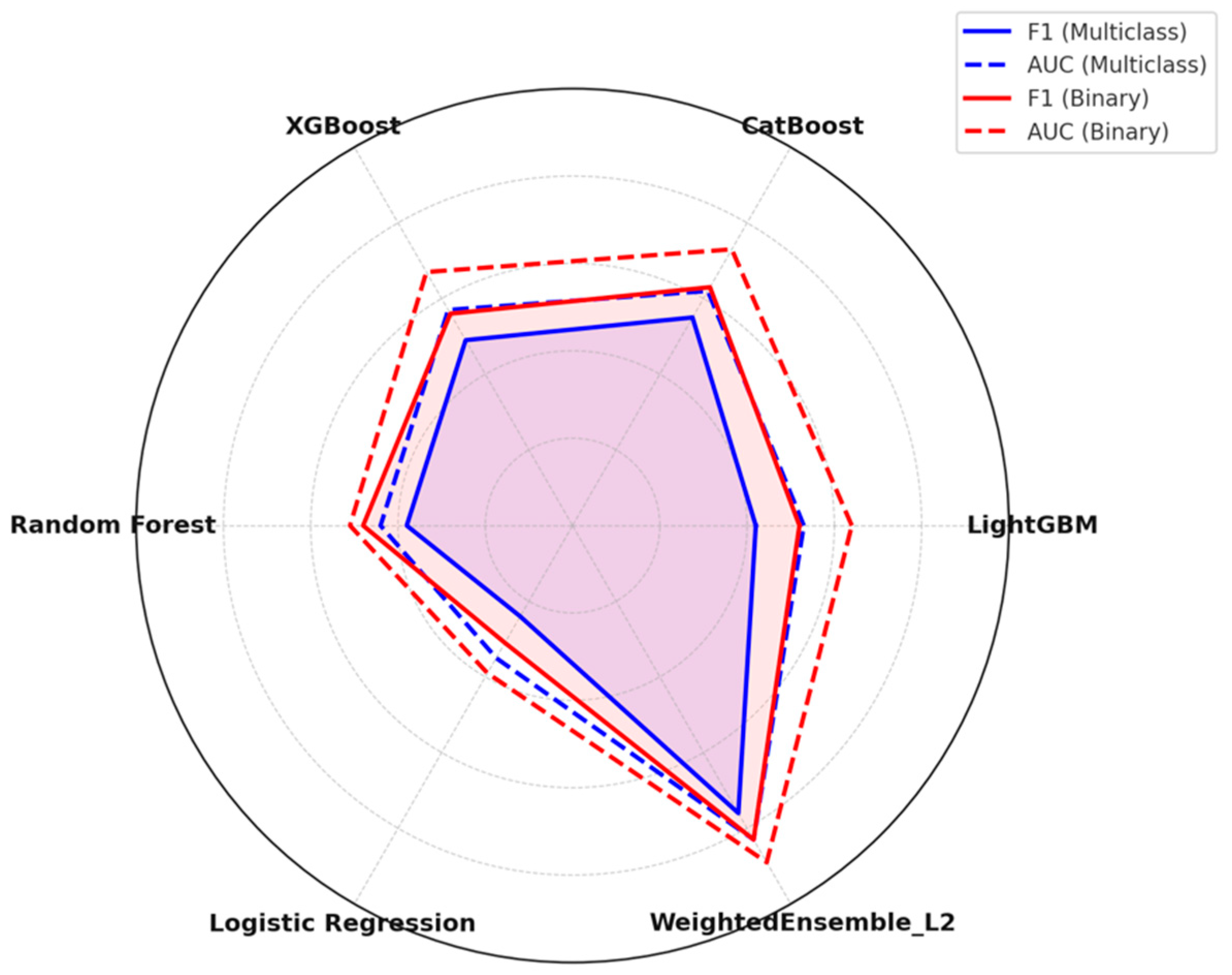

In both tasks, we found that the WeightedEnsemble_L2 model consistently outperformed the individual base models. This ensemble strategy combines the highest-performing models contained in a stack of AutoGluon, thereby harnessing the strengths of each model to generate a robust prediction. In

Table 8, the validation and test accuracy of each model are summarised in the two classification settings.

LightGBM, XGBoost, and CatBoost are tree-based gradient boosting models that demonstrated robust, stable performance across both classification settings. All of these models (which are known to work well with tabular data) achieved test accuracy exceeding 97% in the binary task and more than 96% in the multiclass task. The fact that they are close to the ensemble’s performance implies that they are substantial contributors to behaviour prediction pipelines.

Even for structured datasets, it has been shown that a deep learning approach, combined with feature preprocessing and automatic tuning, can be reliable, as demonstrated by the neural network example in NeuralNetTorch.

Conversely, K-Nearest Neighbours (KNN) classifiers achieved relatively lower accuracy, especially in the multiclass scenario, suggesting that this approach might be insufficient for addressing subtle differences in behaviour using distance-based logic.

The value transmission between the two tasks validates the resilience of ensemble/tree-based techniques, while underscoring that task difficulty (multiclass vs. binary) can affect model sensitivity and separation capacity. This unified analysis provides an explicit basis for selecting the best possible model under various circumstances in which the operations occur. The accuracy of these models for both classification types is visually compared in

Figure 4. The high correspondence between multiclass and binary accuracies confirms the soundness of the best models but also illustrates how task complexity affects model sensitivity and discriminative capability.

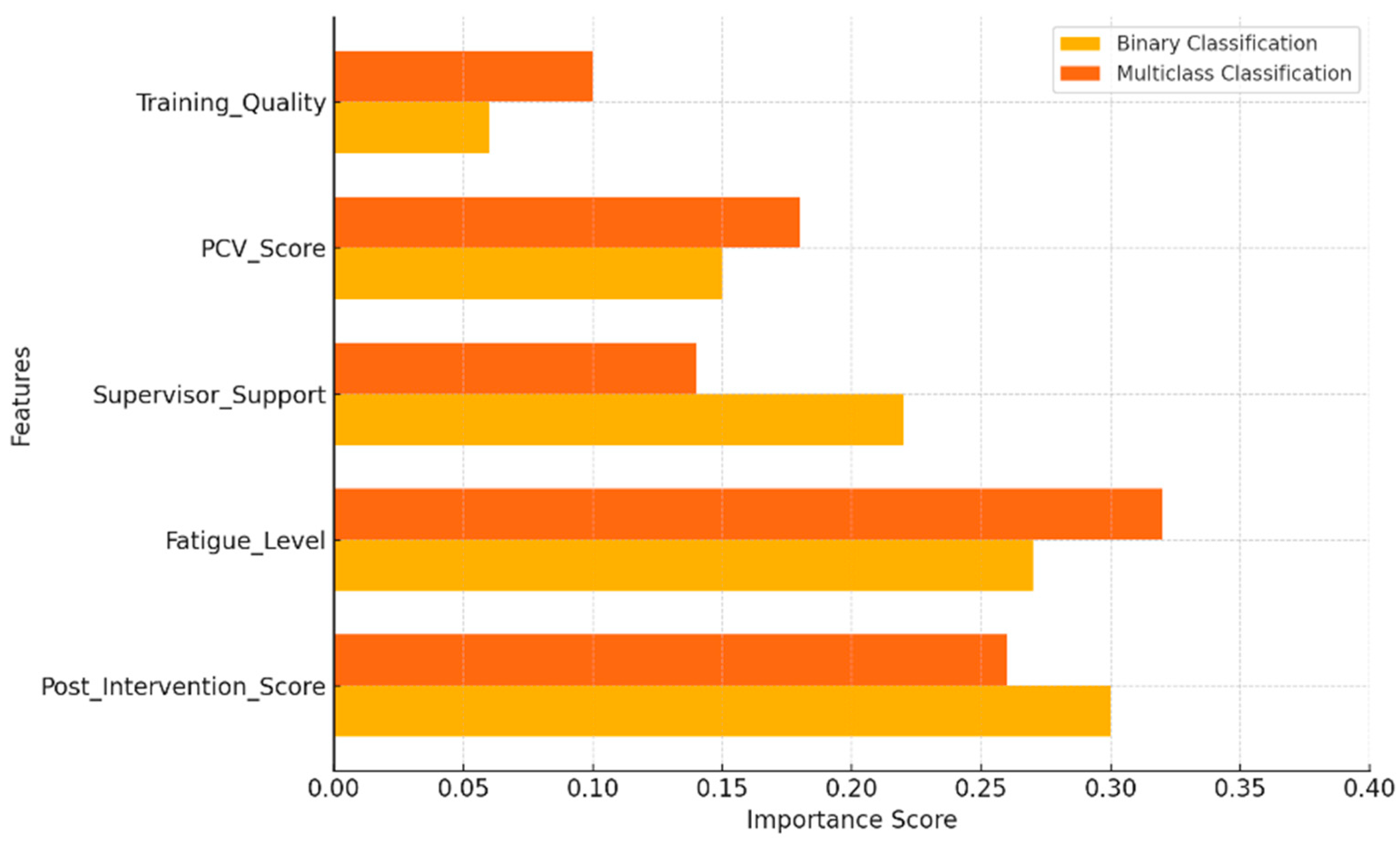

5.3. Feature Importance Analysis

To explain the model’s decision-making, a feature importance analysis was conducted on the model that yielded the best results (WeightedEnsemble_L2) for both multiclass classification and binary classification. Such analysis numerically determines the relative importance of each feature in the model’s predictive performance, thereby balancing explanatory power and domain applicability. In both tasks, psychological and contextual variables were proven to be the most influential. These were response interventions, fatigue, and support, which are directly connected to the dynamics of human behaviour and work safety. The significance of the ranked feature will be represented by . The highest-ranked features per setting of classification:

Binary Classification (Unsafe vs. Safe):

Multiclass Classification (Safe, Moderate, Unsafe):

The most significant predictor in the binary setting was Post-Intervention Score. This implies the considerable impact of structured interventions in reducing unsafe practices. Supervisor Support and Fatigue Level were next, indicating that operational strain and supervisor input impacted behavioural safety. Conversely, the multiclass setting was found to have FatigueLevel as the most influential factor, as it played a prominent role in differentiating between moderate and unsafe behaviour, as opposed to the binary model that only requires the distinct differentiation of safe and dangerous behaviour. The multiclass scenario also observed a decline in TrainingQuality, likely due to its ability to distinguish between moderate and safe types. These results align with the existing literature on behavioural safety and the psychological contract approach. Their focus is that not only mental states (e.g., fatigue, stress) but also organizational interventions (e.g., supervisor support, training quality) play a crucial role in influencing risk behaviours among miners.

Furthermore, they confirm the model’s compliance with established human factors and safety procedures, and the resulting potential for real-world implementation and policy development is promising. In

Figure 5, we can see the relative significance of the top characteristics in both classification conditions. Although several features, such as Fatigue_Level and Post_Intervention_Score, were also high-ranking about the binary challenge, others, such as Training

Quality, played a more significant role with the multiclass approach, necessitating the differentiation of behaviour at more granular levels.

5.4. Explainability Using SHAP and LIME

To improve the interpretability of our model predictions, we employed two model-agnostic explainability methods: SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations). These approaches gave global and local accounts of feature contributions to multiclass and binary prediction tasks.

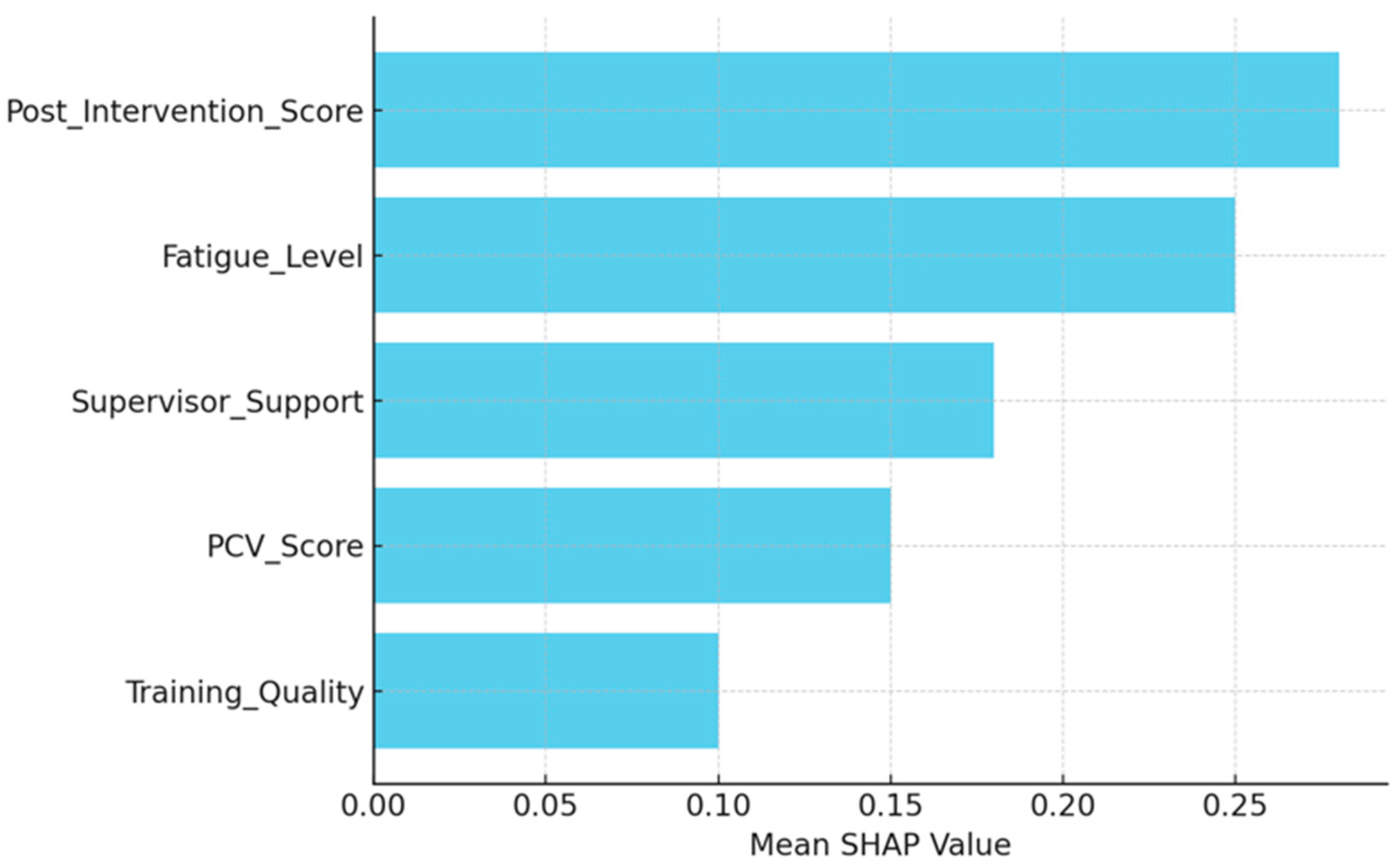

Global Feature Importance via SHAP: Globally, the SHAP summary plots were used to illustrate the magnitude and direction of each feature’s impact on the model’s prediction. Features such as Post-Intervention Score and Fatigue Level showed the highest average SHAP values in each of the two classification tasks. These findings were consistent with expectations in the domain, indicating that intervention effectiveness and fatigue were key predictors of unsafe behavior.

The SHAP framework decomposes each prediction into additive contributions from individual features. For a prediction

, the SHAP decomposition is given by:

where

= base value (expected model output across the dataset),

= SHAP value for feature

j in instance

i (marginal contribution),

d = number of input features (

d = 20 in this study).

SHAP values are computed using game-theoretic Shapley values, which distribute prediction credit fairly across all features by considering all possible feature coalitions. SHAP bar plots in

Figure 6 demonstrated that high Fatigue_Level values tended to bias the prediction toward the unsafe category (positive SHAP values), while high Post_Intervention_Score values provided protective effects (negative SHAP values).

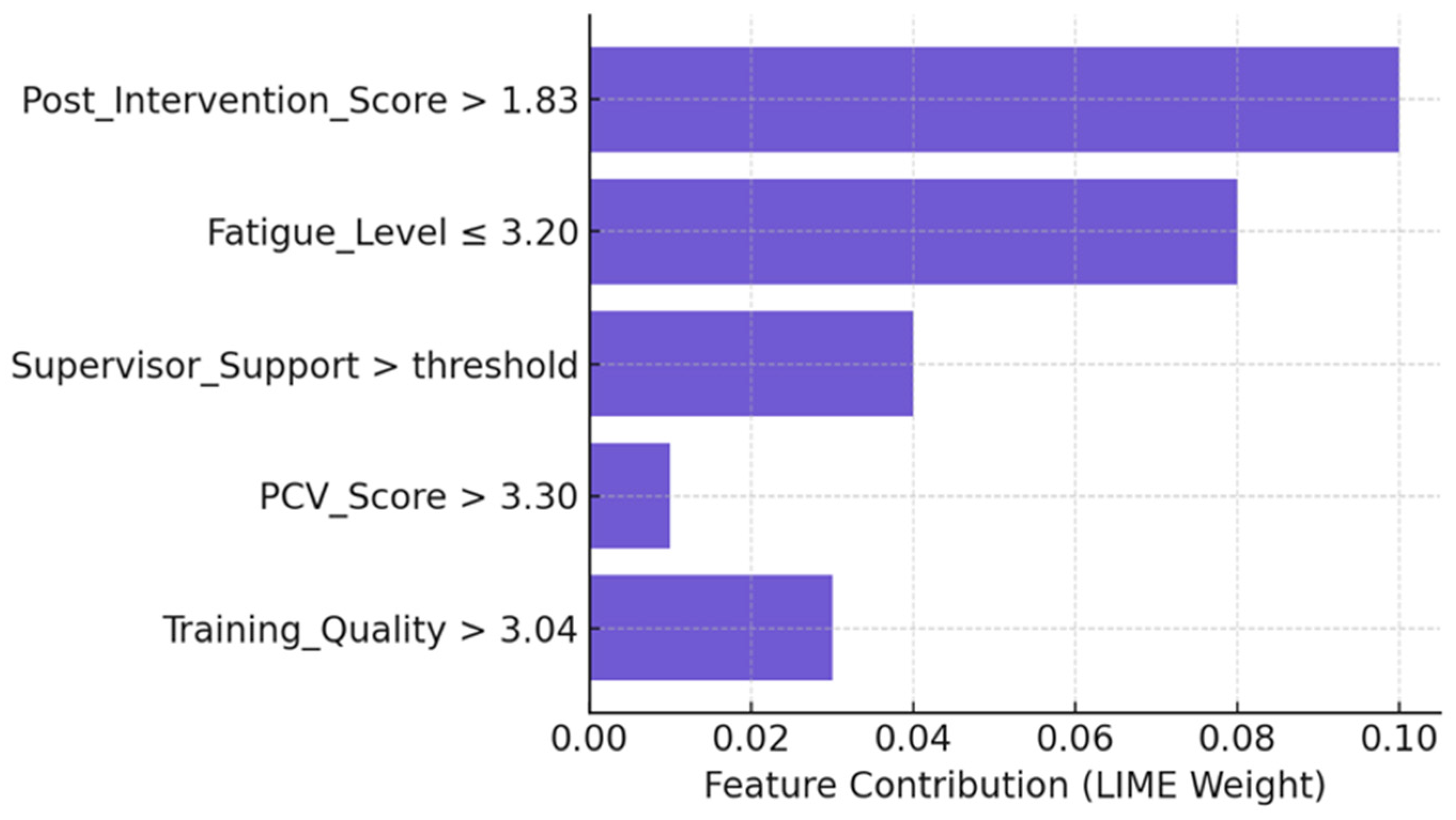

5.4.1. Local Instance-Level Explanations via LIME

To explain individual predictions, we used LIME, which builds a local surrogate model g(x′) that approximates the complex model f(x) in the vicinity of a given instance. The LIME optimization problem is formulated as:

where x′ = binary vector indicating presence/absence of features f = original complex model (WeightedEnsemble_L2) g = interpretable surrogate model (e.g., linear regression) G = class of interpretable models L(f, g, π_x) = loss function measuring fidelity between f and g π_x = proximity measure weighting samples by distance from x Ω(g) = complexity penalty encouraging model simplicity

Equation (2) balances local fidelity (how well g approximates f near the instance) with model simplicity (preferring fewer features), illustrated in

Figure 7. To illustrate LIME’s local explanations, consider Miner #347 from the test set, which was correctly classified as “Unsafe” with a 94.2% probability. LIME analysis revealed the following feature contributions: Fatigue_Level = 8.3/10 (contribution: +0.42 toward unsafe prediction), Post_Intervention_Score = 3.1/10 (contribution: −0.28, protective effect), Training_Quality = 2/5 (contribution: +0.19), and Supervisor_Support = 3.2/10 (contribution: +0.15). These local contributions sum to explain why this individual was flagged as high-risk, as shown in

Figure 7.

5.4.2. Consistency Between SHAP and LIME

While both methods identify similar top predictors (Post_Intervention_Score, Fatigue_Level, Supervisor_Support), there are notable differences in feature rankings. SHAP provides globally averaged importance, consistently placing Post_Intervention_Score as the top contributor (mean |SHAP| = 0.31). LIME, being instance-specific, shows variable rankings depending on individual profiles. In the Miner #347 example, LIME identified Fatigue_Level as primary (+0.42) due to this individual’s extreme fatigue, whereas PCV_Score had lower local importance despite being globally significant in SHAP analysis. This divergence is expected: SHAP reflects population-level patterns while LIME captures instance-specific decision boundaries. The convergence on the same feature set across both methods strengthens confidence in these predictors.

To reduce potential distortion of feature attributions due to multicollinearity, a variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis was conducted; all VIF values were below 5, indicating acceptable independence among predictor variables. A bootstrapped sensitivity analysis with 10 resamples was undertaken to assess the stability of feature importance rankings, yielding an average Spearman correlation of 0.93 between bootstrap iterations. This high rank correlation implies that interpretability results are robust to sampling variation, with Post-Intervention Score, Fatigue Level, and Supervisor Support retaining consistent importance across subsamples. The agreement between SHAP and LIME on core features, despite methodological differences, further validates these as robust predictors, independent of the explanation technique.

Global SHAP decomposition:

Local LIME approximations (Equation (2)) highlight

TrainingQuality ↓ and

FatigueLevel ↑ as unsafe predictors (

Table 9). These explainable patterns direct interventions in fatigue management and supervisory communication.

5.4.3. Interpretability and Synthetic Data Constraints

While SHAP and LIME provide valuable insights, their explanations are limited by the design of the synthetic data. Because correlations were pre-encoded (e.g., fatigue ↔ Unsafe behaviour), the model rediscovers these relationships rather than learning emergent patterns from real-world complexity. Consequently, feature interactions may appear cleaner and more interpretable than they would be with field data, where unmeasured confounders and measurement noise introduce ambiguity. Future validation with real miner data will test whether these interpretable patterns hold or if additional contextual factors emerge as significant predictors.

5.5. Prediction on Unseen Samples

To assess the reliability of the predictions, 10 unseen test samples were selected for evaluation. The probabilities of the predicted classes ranged from 0.948 to 0.991 in

Table 10, with 9 predictions out of 10 correct based on the true class label, and only 1 was accepted with borderline confidence.

6. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate whether automated, explainable machine learning could elucidate miners’ behaviour across various workplace conditions. The goal was not only to build an accurate model but also to understand why specific patterns emerge. Using AutoGluon made it possible to handle the data efficiently, while SHAP and LIME helped turn the numbers into something people can interpret.

The framework was designed with care for ethics and practicality, including:

- (a)

Transparency: All model decisions must be explainable via SHAP/LIME to workers and their representatives, ensuring algorithmic accountability.

- (b)

Human Oversight: Predictions serve as screening flags for human review, not automated disciplinary actions. Safety officers must validate each high-risk classification before intervention.

- (c)

Supportive Use: Flagged individuals receive additional safety resources, training, or fatigue management support, not punishment. The goal is risk mitigation, not blame assignment.

- (d)

Bias Auditing: Regular checks for demographic bias (age, education, tenure) using disparate impact metrics. Model retraining is triggered if any group shows a difference of more than 10% in the false-positive rate.

- (e)

Worker Consent: Deployment requires a collective agreement with worker representatives, with opt-out provisions and data privacy protections.

6.1. Interpretation of Model Performance

The ensemble model performed remarkably well. Accuracy reached 97.6% for the multiclass task and 98.3% for the binary classification. That difference might seem small, but it actually tells a story. It is naturally harder to separate the three behaviour levels than to distinguish between safe and unsafe. Even so, the model maintained balance across classes and avoided overfitting. This kind of consistency is rare when dealing with behavioural data, which is often noisy and unpredictable. The strong scores indicate that the AutoGluon ensemble effectively handles variation and can generalise to unseen data, a crucial trait for any real-world safety system.

6.2. Feature Influence and Theoretical Alignment

The most notable features were the Post-Intervention Score, Fatigue Level, Supervisor Support, and PCV Score. They all fit well with our existing understanding of how people behave in high-risk occupations. Employees make mistakes and take risks when they feel worn out or unsupported. On the other hand, fair treatment and training tend to improve safety and rebuild trust. Seeing the model support rather than challenge accepted theory was comforting. This alignment increases trust that the framework makes sense in an organisational and psychological context, in addition to being a good predictor. It ties data science back to the human aspect of security.

6.3. Explainability and Trust in AI

Adding SHAP and LIME turned what could have been a black box into something understandable. SHAP highlighted the overall importance of each factor, while LIME zoomed in on how specific predictions were formed. Together, they painted a clear picture of both the forest and the trees. For people managing safety programs, that clarity matters far more than a decimal point of accuracy. They need to know why the system labels someone as high-risk so they can respond fairly. These explanations build the kind of trust that determines whether a model gets used or ignored.

6.4. Practical Deployment Considerations

Real-world deployment necessitates integration into existing workflows, the provision of appropriate interfaces, human oversight, and the navigation of organisational barriers.

- (a)

Workflow Integration: The system would supplement weekly safety reviews by flagging high-risk individuals for supervisor validation. Safety officers would review model predictions alongside SHAP/LIME explanations before determining interventions (additional training, workload adjustment, fatigue assessment).

- (b)

Interface Design: A web-based dashboard would display colour-coded risk levels, individual profiles with feature values, SHAP bar charts, and plain-language explanations (e.g., “High risk due to elevated fatigue and low training completion”). Mobile compatibility enables field use.

- (c)

Human-in-the-Loop: Mandatory human validation of all high-risk predictions ensures that automated decision-making is not made without proper oversight. Safety officers retain final authority on interventions, which must be supportive (not punitive). Quarterly audits monitor bias and rates of false positives and negatives.

- (d)

Barriers: Organisational challenges include worker resistance (addressed via transparent communication and non-punitive guarantees) and supervisor buy-in (demonstrated efficiency gains). Regulatory barriers include a lack of AI-specific safety standards, data privacy requirements (GDPR compliance), and liability concerns (mitigated by advisory-only framing). Pilot programs with regulatory engagement are essential before full deployment.

6.5. Limitations

The synthetic dataset may not fully capture real-world diversity, despite promising results. To confirm generalisability, broader validation with empirical and cross-regional data is necessary. Future research ought to incorporate multimodal sources, including sensor data and safety reports, and investigate hybrid validation and transfer learning to enhance external reliability.

7. Future Direction

Future research is needed to extend the current framework by utilizing real-world datasets in industrial settings, encompassing diverse mining regions, to explore and test model robustness in mixed environments. In addition to tabular measures of psychological and behavioural data, it may be possible to enhance the predictive accuracy of any subsequent work by incorporating additional multimodal data, such as sensor data, CCTV footage, environmental factors, and real-time fatigue estimates. RNN (or transformer) temporal modelling can be employed to detect changing patterns of behaviour and to predict risk in advance. Adaptive learning systems that operate in real-time can create models that are responsive and effective in new conditions. Future research could incorporate counterfactuals or causal inference to make the conclusions more interpretable, allowing supervisors to take action based on the proverbial numbers game or what-ifs. Equity implications and facts (including biases related to gender or education) must be analysed to ensure fair results. Another aspect of exploration would be human–AI cooperation, which will be examined through safety personnel and the AI predictions they employ in the field. Lastly, real-time safety monitoring can be achieved through lightweight, scalable edge deployment models, making the AI tool practical and meaningful for mining. Future research will focus on hybrid validation to test model robustness using both simulated and empirical data across various mining areas. Transfer-learning pipelines will be trained to fine-tune existing pre-trained AutoGluon ensembles using smaller samples of field-collected psychological and operational data. This will enhance external validity and narrow the synthetic-to-real performance gap, as highlighted in this study.

8. Conclusions

The study proposed an inclusive machine learning algorithm to forecast and interpret unsafe behaviours among miners, accounting for elements of psychological contract violation. A real-world synthetic dataset was used to perform both multiclass and binary classification using the AutoGluon TabularPredictor framework. Models performed well in predictive analyses (accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score), with the WeightedEnsemble_L2 model outperforming others. Extensive preprocessing procedures were performed to ensure the model’s reliability. Explainability was a priority area, and SHAP and LIME methods were applied to demonstrate the global and local effects of psychological and workplace factors on safety outcomes. The analysis revealed that factors such as fatigue, intervention type, and post-intervention scores are critical for predicting unsafe behaviour. Planned experiments had significant data splits, training streams, and reproducing parameters. The models were also made more usable and trustworthy by incorporating explainable AI methods. The offered framework will, in general, provide a safe, explainable, and user-friendly technique for identifying and eliminating unsafe actions in mining settings early. The work serves as the foundation for occupational safety systems based on AI, which can be scaled with multimodal data and implemented in industrial settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y. and J.L.; Methodology, Y.Y.; Software, Y.Y.; Validation, Y.Y. and J.L.; Formal Analysis, Y.Y.; Investigation, Y.Y.; Resources, Y.Y.; Data Curation, Y.Y.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Y.Y.; Writing—Review & Editing, J.L.; Visualization, Y.Y.; Supervision, J.L.; Project Administration, Y.Y.; Funding Acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the administrative support provided by the College of Economics and Management, Taiyuan University of Technology. The authors also appreciate the technical assistance received during the experimental implementation phase.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- Haiedar, M.H.; Kholifah, S. The Impact of Occupational Safety, Workload, and Compensation on Employee Job Satisfaction in the Mining Industry: A Case Study of PT BCKA. J. Manag. Inform. 2025, 4, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yin, X.; Guo, Y.; Tong, R. What occupational risk factors significantly affect miners’ health: Findings from meta-analysis and association rule mining. J. Saf. Res. 2024, 89, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, M.S.; Bradley, J.C.; Wallace, J.C.; Burke, M.J. Workplace safety: A meta-analysis of the roles of person and situation factors. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1103–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogoeng, K.B. Employee Retention by Controlling Expectations: Understanding the Psychological Contract of Employers in the Mining Sector. Ph.D. Thesis, North-West University (South Africa), Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- MG, S.P.; KS, A.; Rajendran, S.; Sen, K.N. The role of psychological contract in enhancing safety climate and safety behavior in the construction industry. J. Eng. Des. Technol. 2025, 23, 1189–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, J.; De Las Heras-Rosas, C. The organizational commitment in the company and its relationship with the psychological contract. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 609211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mevsim, R. Development of an Accident Causation Model for Underground Coal Mines. Ph.D. Thesis, Middle East Technical University (Turkey), Ankara, Türkiye, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, E.J.; Yorio, P. Exploring the state of health and safety management system performance measurement in mining organizations. Saf. Sci. 2016, 83, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lööw, J.; Johansson, B.; Andersson, E.; Johansson, J. Designing Ergonomic, Safe, and Attractive Mining Workplaces; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Toğan, V.; Mostofi, F.; Ayözen, Y.E.; Behzat Tokdemir, O. Customized AutoML: An automated machine learning system for predicting severity of construction accidents. Buildings 2022, 12, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Wong, Y.D.; Chai, C.; Li, M.Z.-F. An automated machine learning (AutoML) method of risk prediction for decision-making of autonomous vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 22, 7145–7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaker, S.K.; Hassan, M.M.; Smith, M.J.; Xu, L.; Zhai, C.; Veeramachaneni, K. Automl to date and beyond: Challenges and opportunities. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohara, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Soejima, H.; Nakashima, N. Explanation of machine learning models using improved shapley additive explanation. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM International Conference on Bioinformatics, Computational Biology and Health Informatics, Niagara Falls, NY, USA, 7–10 September 2019; p. 546. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, M.R.; Khan, N. Deterministic local interpretable model-agnostic explanations for stable explainability. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2021, 3, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, P.A. The Psychological Contract: Reconstructing the Work Relationship; California School of Professional Psychology-Berkeley/Alameda: Alameda, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Tijoriwala, S.A. Assessing psychological contracts: Issues, alternatives and measures. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 1998, 19, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worlanyo, V.S. Psychological Contract Violation and Employee Turnover Intention Among Banks in the Cape Coast Metropolis: The Role of Job Dissatisfaction. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Azeem, M.U.; Bajwa, S.U.; Shahzad, K.; Aslam, H. Psychological contract violation and turnover intention: The role of job dissatisfaction and work disengagement. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2020, 42, 1291–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Agarwal, U.A. Linking workplace bullying and work engagement: The mediating role of psychological contract violation. South Asian J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 4, 42–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, C. Psychological Contract Violation, Work Stress and Insomnia: A Quantitative Mediation Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Grand Canyon University, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, E.; Pekkari, A.; Johansson, J.; Lööw, J. Mining 4.0 and its effects on work environment, competence, organisation and society—A scoping review. Miner. Econ. 2024, 37, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Rizvi, F.; Farooq, W.; Ahmed, I. Employee silence as a response to cronyism in the workplace: The roles of felt violation and continuance commitment. Kybernetes 2025, 54, 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, E.J. The role of supervisory support on workers’ health and safety performance. Health Commun. 2020, 35, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.S.; Rehman, H.U.; Shahani, N.M.; Ullah, B.; Abbas, N.; Junaid, M.; Hashim, M.H.b.M. Towards safer mining environments: An in-depth review of predictive models for accidents. Arab. J. Geosci. 2024, 17, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedla, A.; Kakhki, F.D.; Jannesari, A. Predictive modeling for occupational safety outcomes and days away from work analysis in mining operations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, P.S.; Maiti, J. The role of behavioral factors on safety management in underground mines. Saf. Sci. 2007, 45, 449–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. Predictive models: Regression, decision trees, and clustering. Appl. Comput. Eng. 2024, 79, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortey, L.; Edwards, D.J.; Roberts, C.; Rillie, I. A review of safety risk theories and models and the development of a digital highway construction safety risk model. Digital 2022, 2, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; Ma, K.; Gu, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Ni, G.; Ojum, C.; Opoku, A.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of risk factors affecting the safety of coal mine construction projects using an integrated DEMATEL-ISM approach. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2025, 32, 3432–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavzoglu, T.; Teke, A. Predictive performances of ensemble machine learning algorithms in landslide susceptibility mapping using random forest, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) and natural gradient boosting (NGBoost). Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2022, 47, 7367–7385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, K.; Chen, F.; Khattak, A. Improvements aiming at a safer living environment by analyzing crash severity through the use of boosting-based ensemble learning techniques. Int. J. Crashworthiness 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.U.; Aslam, N.; AlShedayed, R.; AlFrayan, D.; AlEssa, R.; AlShuail, N.A.; Al Safwan, A. A proactive attack detection for heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) system using explainable extreme gradient boosting model (XGBoost). Sensors 2022, 22, 9235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.J.; Sultana, J.; Ahmed, S.; Momen, S. Early detection of occupational stress: Enhancing workplace safety with machine learning and large language models. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0323265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koc, K. Role of national conditions in occupational fatal accidents in the construction industry using interpretable machine learning approach. J. Manag. Eng. 2023, 39, 04023037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofi, F.; Toğan, V. A data-driven recommendation system for construction safety risk assessment. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 04023139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, C. Comparative Analysis of Automated Machine Learning and Optimized Conventional Machine Learning for Concrete’s Uniaxial Compressive Strength Prediction. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2024, 2024, 3403677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwen, L.O.; Schacherer, D.; Geißler, C.; Homeyer, A. Evaluating generic AutoML tools for computational pathology. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2022, 29, 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladino, L.M.; Hughes, A.; Perera, A.; Topsakal, O.; Akinci, T.C. Evaluating the performance of automated machine learning (AutoML) tools for heart disease diagnosis and prediction. AI 2023, 4, 1036–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thekdi, S.; Aven, T. Understanding explainability and interpretability for risk science applications. Saf. Sci. 2024, 176, 106566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisineni, S.R.A.; Pal, M. Enhancing trust and interpretability of complex machine learning models using local interpretable model agnostic shap explanations. Int. J. Data Sci. Anal. 2024, 18, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M. Understanding model predictions: A comparative analysis of SHAP and LIME on various ML algorithms. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2023, 5, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A. Applied Machine Learning Explainability Techniques: Make ML Models Explainable and Trustworthy for Practical Applications Using LIME, SHAP, and More; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Sun, H.; Huang, Y.; Chen, H. Shapley value: From cooperative game to explainable artificial intelligence. Auton. Intell. Syst. 2024, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrick, L.; Taly, A. The explanation game: Explaining machine learning models using shapley values. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction: 4th IFIP TC 5, TC 12, WG 8.4, WG 8.9, WG 12.9 International Cross-Domain Conference, CD-MAKE 2020, Dublin, Ireland, 25–28 August 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Y.; Zou, J.Y. Weightedshap: Analyzing and improving shapley based feature attributions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 34363–34376. [Google Scholar]

- Sokol, K.; Hepburn, A.; Santos-Rodriguez, R.; Flach, P. bLIMEy: Surrogate prediction explanations beyond LIME. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nóbrega, C.; Marinho, L. Towards explaining recommendations through local surrogate models. In Proceedings of the 34th ACM/SIGAPP Symposium on Applied Computing, Limassol, Cyprus, 8–12 April 2019; pp. 1671–1678. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, S.; Liu, Y. Using a Local Surrogate Model to Interpret Temporal Shifts in Global Annual Data. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.11874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Chaudhari, S. Safety of workers in Indian mines: Study, analysis, and prediction. Saf. Health Work. 2017, 8, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Ju, C.; Koh, T.Y.; Rowlinson, S.; Bridge, A.J. The impact of transformational leadership on safety climate and individual safety behavior on construction sites. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ding, L.; Wu, X.; Skibniewski, M.J. An improved Dempster-Shafer approach to construction safety risk perception. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2019, 132, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tixier, A.J.P.; Hallowell, M.R.; Rajagopalan, B.; Bowman, D. Application of machine learning to construction injury prediction. Autom. Autom. Autom. Constr. 2016, 69, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable Machine Learning: A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable. 2020. Available online: https://christophm.github.io/interpretable-ml-book/ (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Robinson, S.L.; Morrison, E.W. The development of psychological contract breach and violation: A longitudinal study. J. Organ. Behav. 2000, 21, 525–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epitropaki, O. A multi-level investigation of psychological contract breach and organizational identification through the lens of perceived organizational membership: Testing a moderated-mediated model. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, A.; Lombardi, D.A.; Folkard, S.; Stutts, J.; Courtney, T.K.; Connor, J.L. The link between fatigue and safety. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 498–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Graf, F.; Órdenes, J.; Wilson, R.; Navarra, A. Discrete event simulation for machine-learning enabled mine production control with application to gold processing. Metals 2022, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.; Löfstrand, M.; Andrews, J. Modelling stochastic behaviour in simulation digital twins through neural nets. J. Simul. 2022, 16, 512–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Outlines the end-to-end methodology, including data collection, preprocessing, model training with AutoGluon, evaluation using multiple metrics, and model interpretability via SHAP and LIME. Visualisation tools and reproducibility practices are also integrated into the workflow.

Figure 1.

Outlines the end-to-end methodology, including data collection, preprocessing, model training with AutoGluon, evaluation using multiple metrics, and model interpretability via SHAP and LIME. Visualisation tools and reproducibility practices are also integrated into the workflow.

Figure 2.

Number of predictions against the actual labels of the multiclass classification of unsafe behaviour levels based on a test set of 1000 samples. Class 0 is Safe, 1 is Moderate, and 2 is Unsafe. Most errors occur between classes 1 and 2, which are behaviorally closer.

Figure 2.

Number of predictions against the actual labels of the multiclass classification of unsafe behaviour levels based on a test set of 1000 samples. Class 0 is Safe, 1 is Moderate, and 2 is Unsafe. Most errors occur between classes 1 and 2, which are behaviorally closer.

Figure 3.

Binary (Safe or Unsafe) confusion matrix on a 1000-sample test set. Class 0 is marked as Safe, and Class 1 is marked as Unsafe. There was a low misclassification rate, particularly between the safe and unsafe classes, indicating the classifier’s high accuracy.

Figure 3.

Binary (Safe or Unsafe) confusion matrix on a 1000-sample test set. Class 0 is marked as Safe, and Class 1 is marked as Unsafe. There was a low misclassification rate, particularly between the safe and unsafe classes, indicating the classifier’s high accuracy.

Figure 4.

A radar chart comparing macro F1 (solid lines) and ROC-AUC (dotted lines) from different models for both multi-class (blue) and binary (red) classification tasks. The results indicate that the WeightedEnsemble L2 is a consistently better learner and therefore exhibits robust, stable generalisation capabilities.

Figure 4.

A radar chart comparing macro F1 (solid lines) and ROC-AUC (dotted lines) from different models for both multi-class (blue) and binary (red) classification tasks. The results indicate that the WeightedEnsemble L2 is a consistently better learner and therefore exhibits robust, stable generalisation capabilities.

Figure 5.

Comparison of feature importance across binary and multiclass classification tasks.

Figure 5.

Comparison of feature importance across binary and multiclass classification tasks.

Figure 6.

Global Feature Importance via SHAP Analysis. Bar chart showing mean absolute SHAP values across all predictions in the test set (N = 1000). Features are ranked by their average contribution to model predictions. The Post-Intervention Score shows the highest global importance (mean |SHAP| = 0.31), followed by Fatigue Level (0.28) and Supervisor Support (0.24). This summary plot aggregates feature effects across all instances, revealing population-level patterns. High-resolution vector format (SVG) ensures readability of all labels and values.

Figure 6.

Global Feature Importance via SHAP Analysis. Bar chart showing mean absolute SHAP values across all predictions in the test set (N = 1000). Features are ranked by their average contribution to model predictions. The Post-Intervention Score shows the highest global importance (mean |SHAP| = 0.31), followed by Fatigue Level (0.28) and Supervisor Support (0.24). This summary plot aggregates feature effects across all instances, revealing population-level patterns. High-resolution vector format (SVG) ensures readability of all labels and values.

Figure 7.

Local Feature Attribution via LIME (Instance-Level Example). LIME explanation for Miner #347 (predicted: Unsafe, probability: 94.2%). Unlike SHAP’s global view, LIME shows feature contributions specific to this individual: Fatigue_Level has the most substantial local impact (+0.42) due to this miner’s extremely high fatigue score (8.3/10), while Post_Intervention_Score provides a protective effect (−0.28). The instance-specific ranking differs from global SHAP patterns, demonstrating how LIME captures individual decision boundaries. The vector format (SVG) maintains the clarity of contribution values and features.

Figure 7.

Local Feature Attribution via LIME (Instance-Level Example). LIME explanation for Miner #347 (predicted: Unsafe, probability: 94.2%). Unlike SHAP’s global view, LIME shows feature contributions specific to this individual: Fatigue_Level has the most substantial local impact (+0.42) due to this miner’s extremely high fatigue score (8.3/10), while Post_Intervention_Score provides a protective effect (−0.28). The instance-specific ranking differs from global SHAP patterns, demonstrating how LIME captures individual decision boundaries. The vector format (SVG) maintains the clarity of contribution values and features.

Table 1.

System and Software Configuration.

Table 1.

System and Software Configuration.

| Component | Specification |

|---|

| Processor | 2 vCPUs (Intel Xeon family) |

| RAM | 12.67 GB (11.13 GB available) |

| Disk Space Available | 107.72 GB (60.3% free) |

| Operating System | Linux (Google Colab VM) |

| Python Version | 3.11.13 |

| AutoGluon Version | 1.3.1 |

| Additional Libraries | shap, Lime, matplotlib, seaborn, scikit-learn |

Table 2.

Dataset Summary.

Table 2.

Dataset Summary.

| Property | Multiclass Dataset | Binary Dataset |

|---|

| Total Samples | 5000 | 5000 |

| Features | 20 | 20 |

| Target Labels | 0, 1, 2 | 0, 1 |

| Train/Test Split | 80%/20% | 80%/20% |

| Stratification Applied | Yes | Yes |

Table 3.

AutoGluon Model Ensemble Summary.

Table 3.

AutoGluon Model Ensemble Summary.

| Model Type | Variants Used | Notes |

|---|

| LightGBM | LightGBM, LightGBMXT, Large | Fast gradient boosting decision trees |

| CatBoost | CatBoost | Handles categorical data natively |

| XGBoost | XGBoost | Regularized boosting |

| Random Forests | Gini, Entropy | Bagging ensemble of decision trees |

| Extra Trees | Gini, Entropy | More randomized decision forests |

| Neural Networks | Torch, FastAI | Deep learning-based models |

| KNN | Uniform, Distance | Simple but interpretable classifiers |

| Ensemble | WeightedEnsemble_L2 | Combines top base models |

Table 4.

Multiclass Classification Results.

Table 4.

Multiclass Classification Results.

| Metric | Value |

|---|

| Accuracy | 0.976 |

| Precision (macro) | 0.974 |

| Recall (macro) | 0.972 |

| F1-score (macro) | 0.973 |

| ROC-AUC (macro) | 0.980 |

| Matthews Corr. Coef. (MCC) | 0.962 |

Table 5.

Binary Classification Results.

Table 5.

Binary Classification Results.

| Metric | Value |

|---|

| Accuracy | 0.983 |

| Precision | 0.981 |

| Recall | 0.984 |

| F1-score | 0.982 |

| ROC-AUC | 0.990 |

| Matthews Corr. Coef. (MCC) | 0.966 |

Table 6.

Safety-critical performance metrics emphasising recall of unsafe cases.

Table 6.

Safety-critical performance metrics emphasising recall of unsafe cases.

| Metric | Multiclass | Binary |

|---|

| Accuracy | 0.976 | 0.983 |

| Recall (Unsafe) | 0.982 | 0.984 |

| False Negative Rate | 0.018 | 0.016 |

| Safety-Recall Index | 0.982 | 0.984 |

Table 7.

Performance of expert-configured baselines versus AutoGluon ensemble.

Table 7.

Performance of expert-configured baselines versus AutoGluon ensemble.

| Model | Tuned Parameters | Macro F1 (%) | Recall Unsafe (%) | MCC |

|---|

| Logistic Regression | (C = 1.0), balanced weights | 92.4 | 93.1 | 0.89 |

| Random Forest | 400 trees, depth 10 | 94.8 | 95.3 | 0.91 |

| AutoGluon WeightedEnsemble L2 | auto + manual fine-tuning | 97.6 | 98.4 | 0.96 |

Table 8.

Combined Leaderboard for Multiclass and Binary Classification.

Table 8.

Combined Leaderboard for Multiclass and Binary Classification.

| Model | Multiclass Val Acc | Multiclass Test Acc | Binary Val Acc | Binary Test Acc |

|---|

| WeightedEnsemble_L2 | 0.976 | 0.976 | 0.983 | 0.983 |

| LightGBM | 0.971 | 0.970 | 0.978 | 0.976 |

| XGBoost | 0.968 | 0.966 | 0.975 | 0.972 |

| CatBoost | 0.966 | 0.963 | 0.972 | 0.970 |

| NeuralNetTorch | 0.962 | 0.958 | 0.968 | 0.965 |

| KNN (Distance) | 0.950 | 0.944 | 0.957 | 0.954 |

| KNN (Uniform) | 0.938 | 0.930 | 0.942 | 0.936 |

Table 9.

Top SHAP feature-interaction pairs and behavioural interpretation.

Table 9.

Top SHAP feature-interaction pairs and behavioural interpretation.

| Feature Pair | | Interpretation |

|---|

| Fatigue × Supervisor Support | 0.37 | Support buffers fatigue risk |

| PCV × Training Quality | 0.29 | Training reduces PCV impact |

Table 10.

Example Predictions on Unseen Samples.

Table 10.

Example Predictions on Unseen Samples.

| Actual Label | Predicted Label | Predicted Probability |

|---|

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.991 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.985 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.979 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.982 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.973 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.98 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.976 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.948 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.988 |

| 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.986 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).