Evaluation of Emission Reduction Systems in Underground Mining Trucks: A Case Study at an Underground Mine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Measurement Equipment

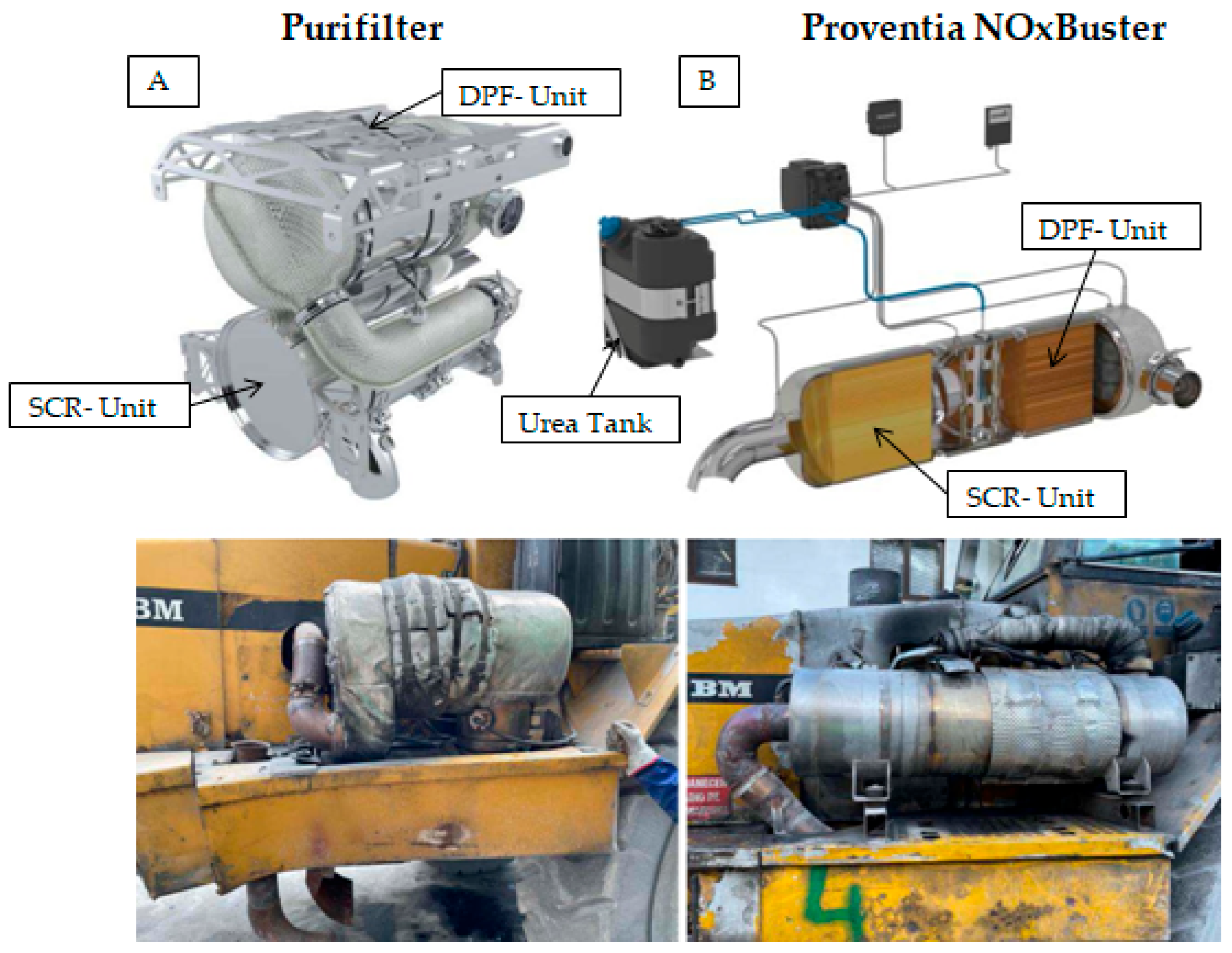

2.3. Emission Control Systems

- Proventia NOxBuster: This system integrates a Diesel Oxidation Catalyst (DOC), DPF, and SCR unit. The DOC neutralises CO and unburnt hydrocarbons, while the DPF captures soot and solid particles. Downstream, the SCR system reduces NOx through the injection of aqueous urea (AdBlue). Designed for engines rated between 50 and 383 kW, it operates effectively at exhaust temperatures ranging from 200 to 500 °C [31] (Figure 1).

- Purifilter: This system also integrates DPF and SCR technologies and is suitable for engines ranging from 75 to 450 kW. Its design and operational principles are similar to the Proventia system but are adapted for specific vehicle configurations.

2.4. Sampling Methodology

2.4.1. Gaseous Emissions Testing

- 0 to 1 min: Idling;

- 1 to 2 min: Acceleration to 3000 rpm;

- 2 to 3.5 min: Idling;

- 3.5 to 4 min: Second acceleration to 3000 rpm;

- 4 min onward: Idling.

2.4.2. Nanoparticle Measurement

3. Results

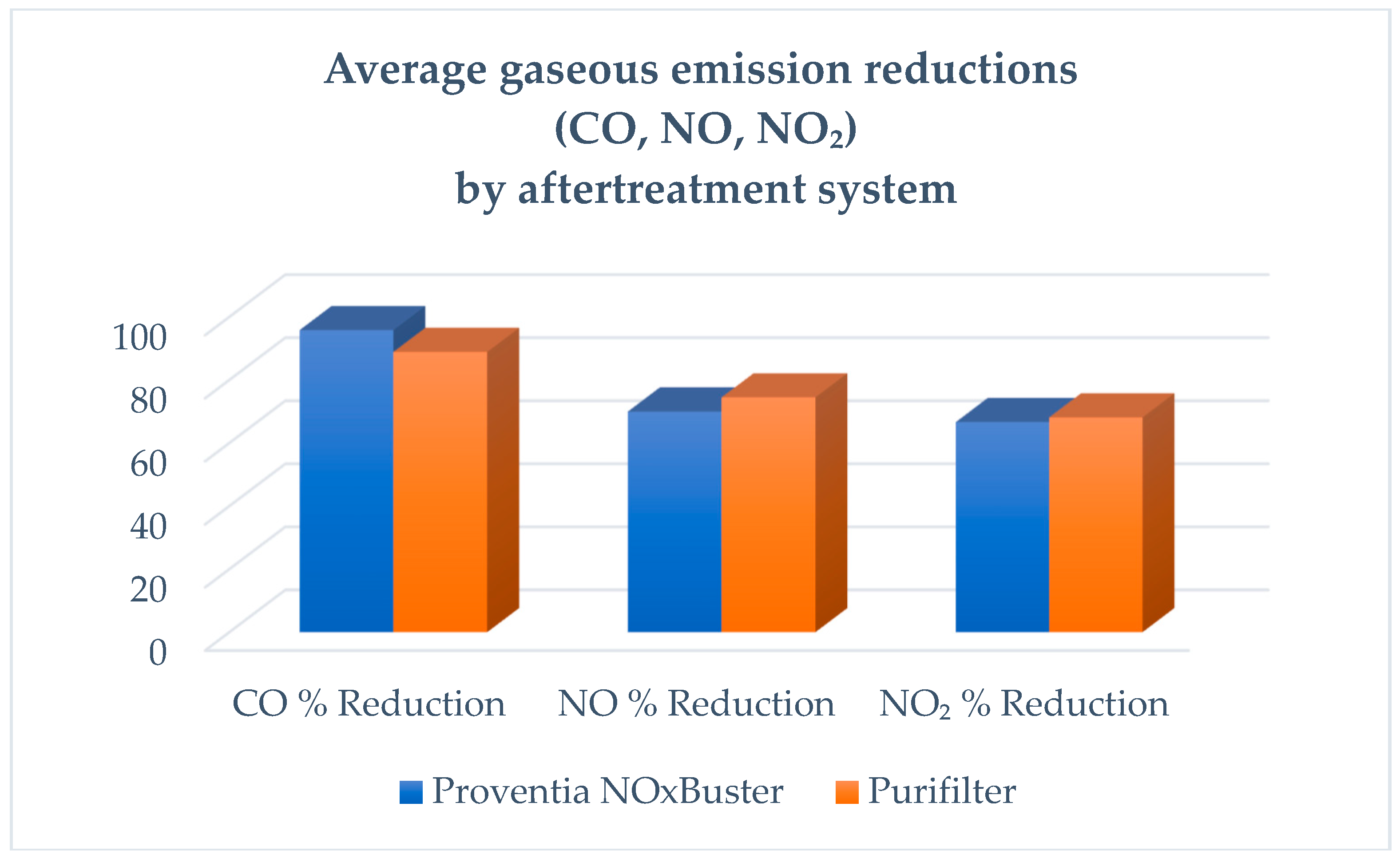

3.1. Gaseous Emissions

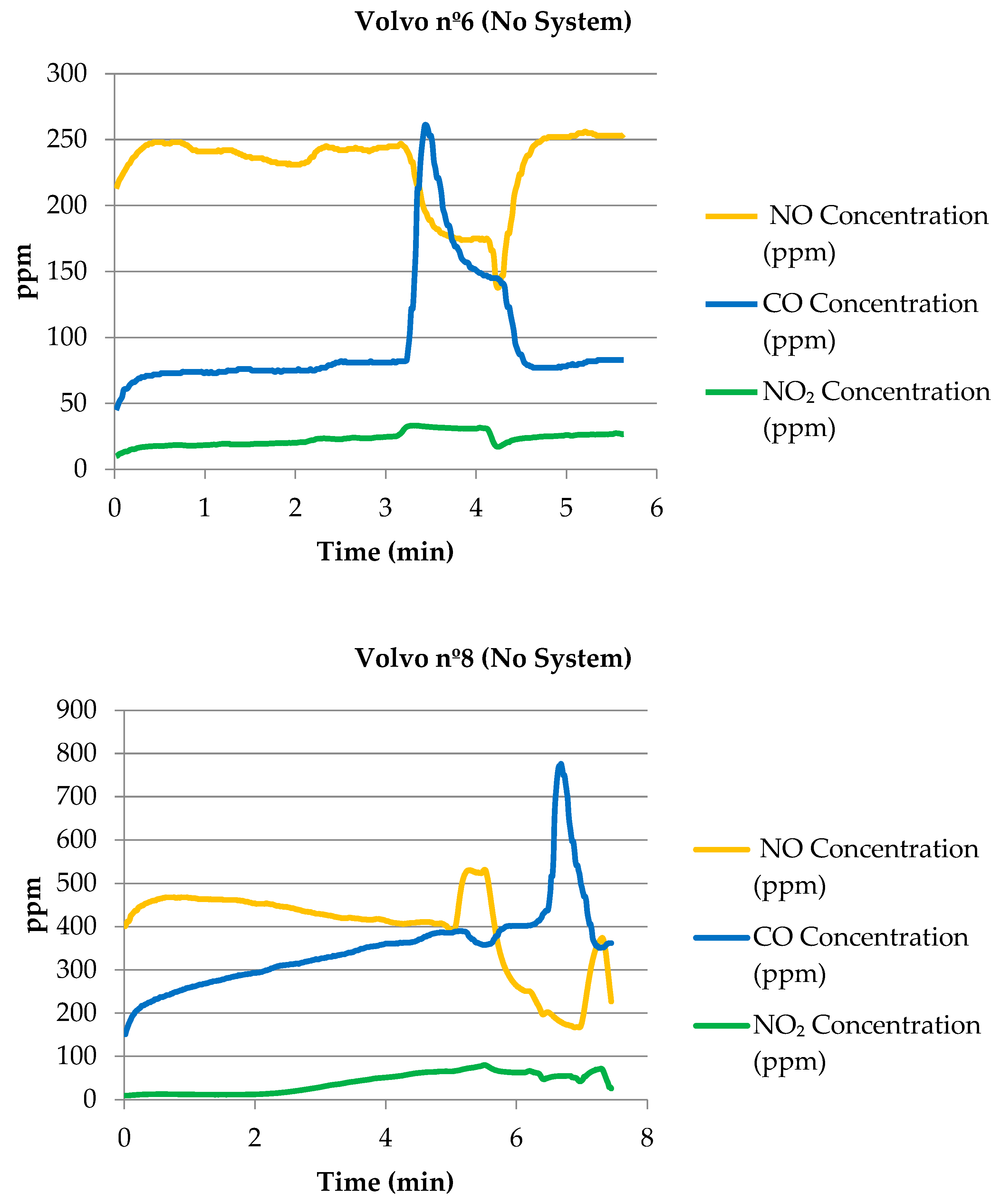

3.1.1. Trucks Without Emission Control Systems

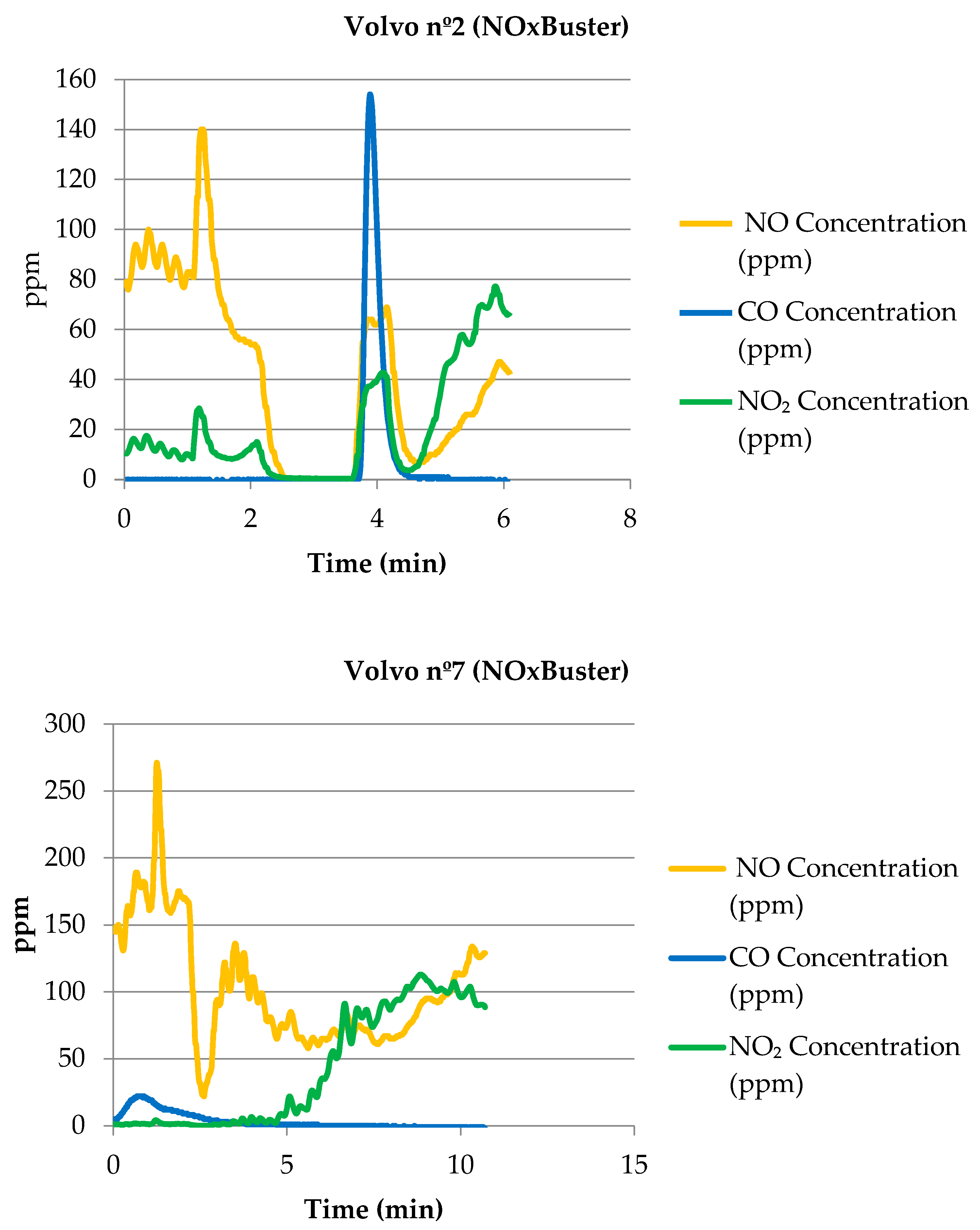

3.1.2. Proventia NOxBuster

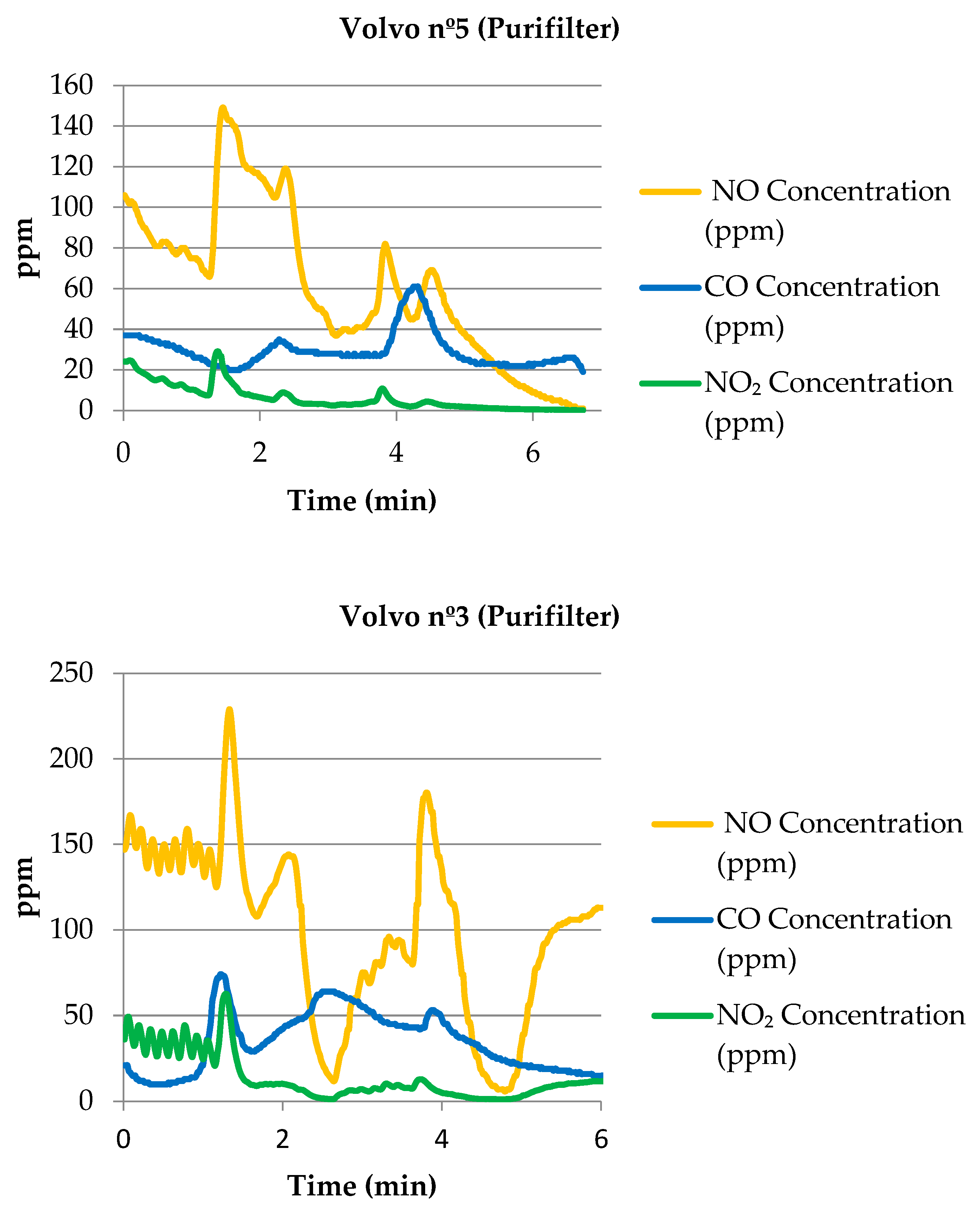

3.1.3. Purifilter

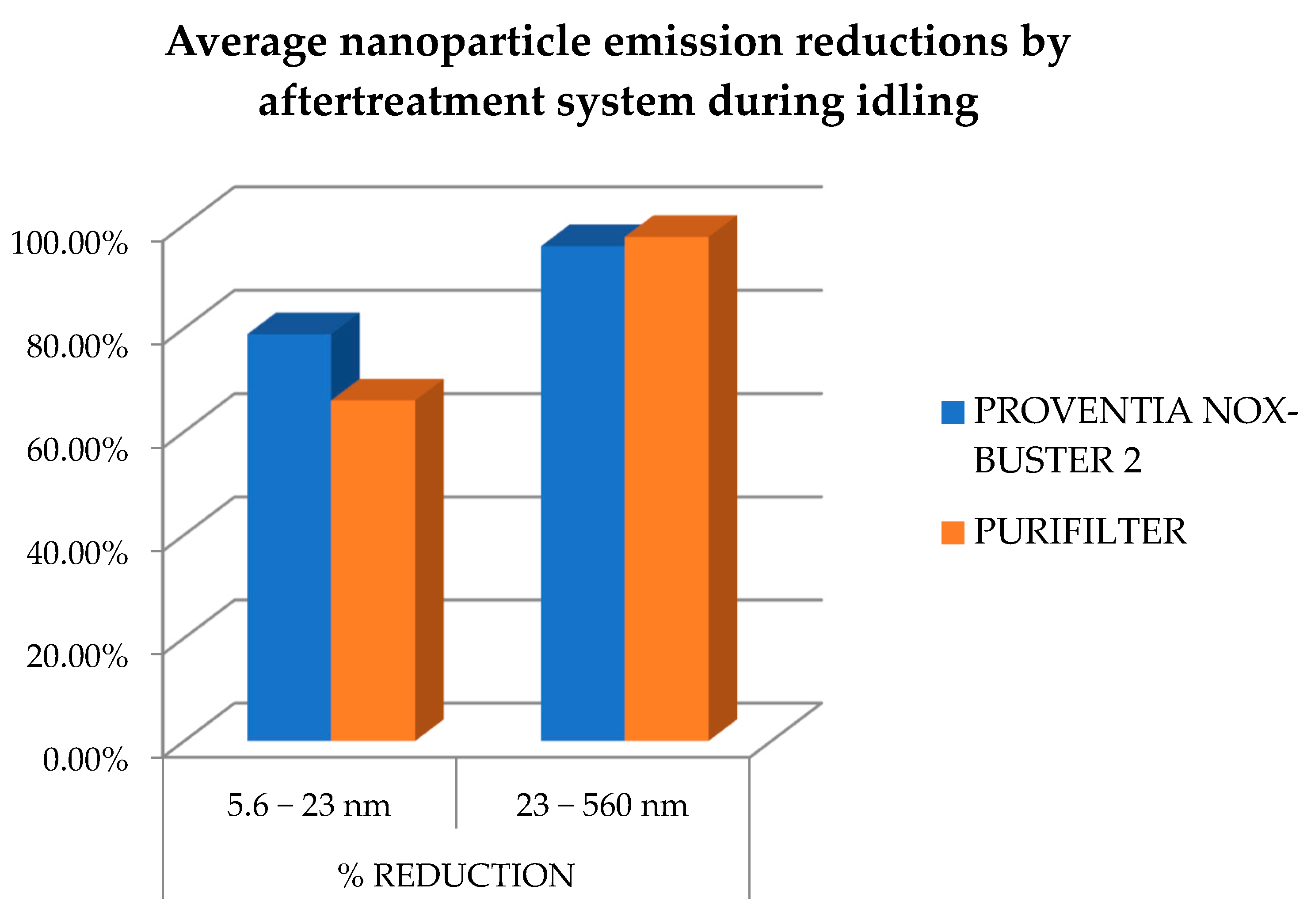

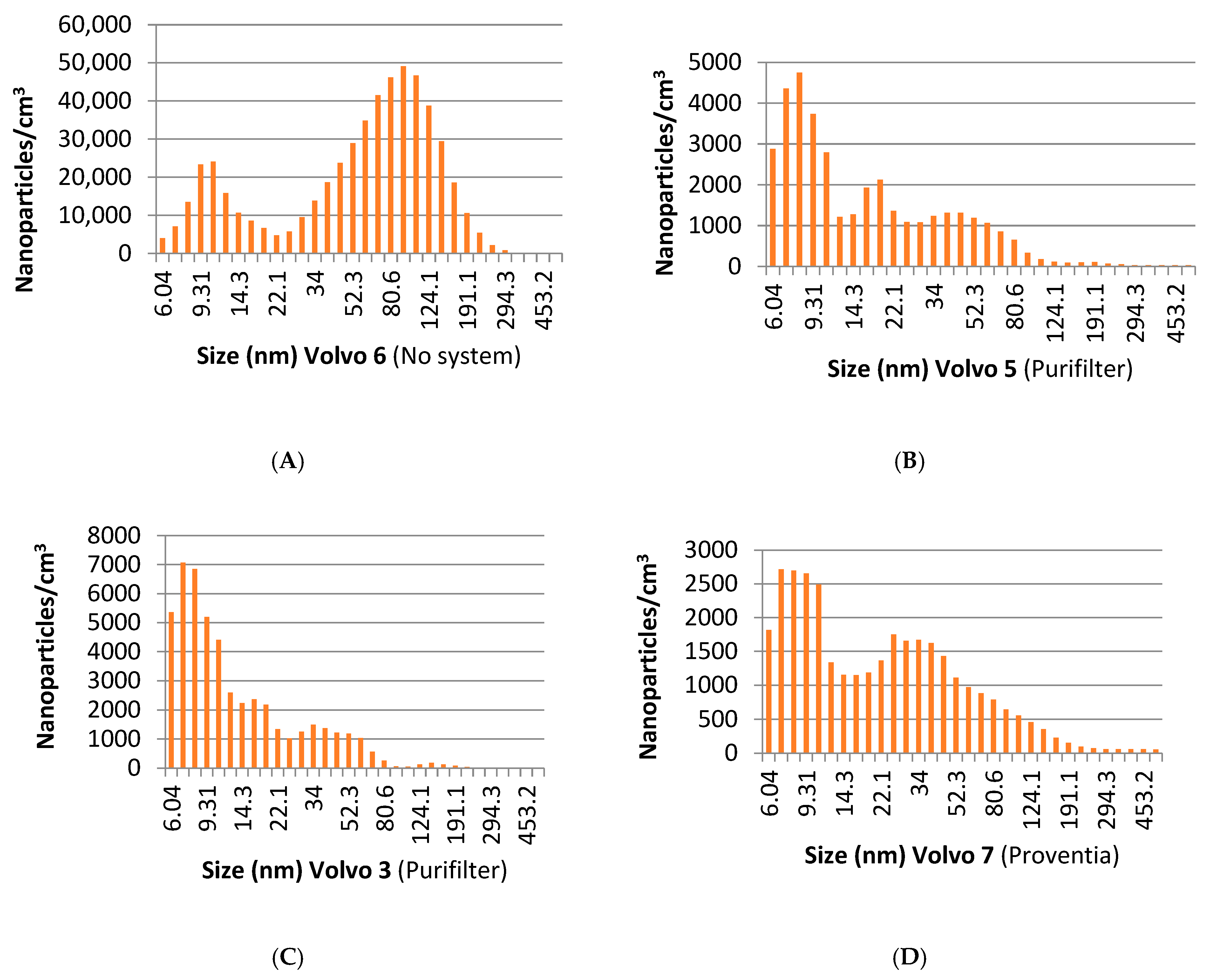

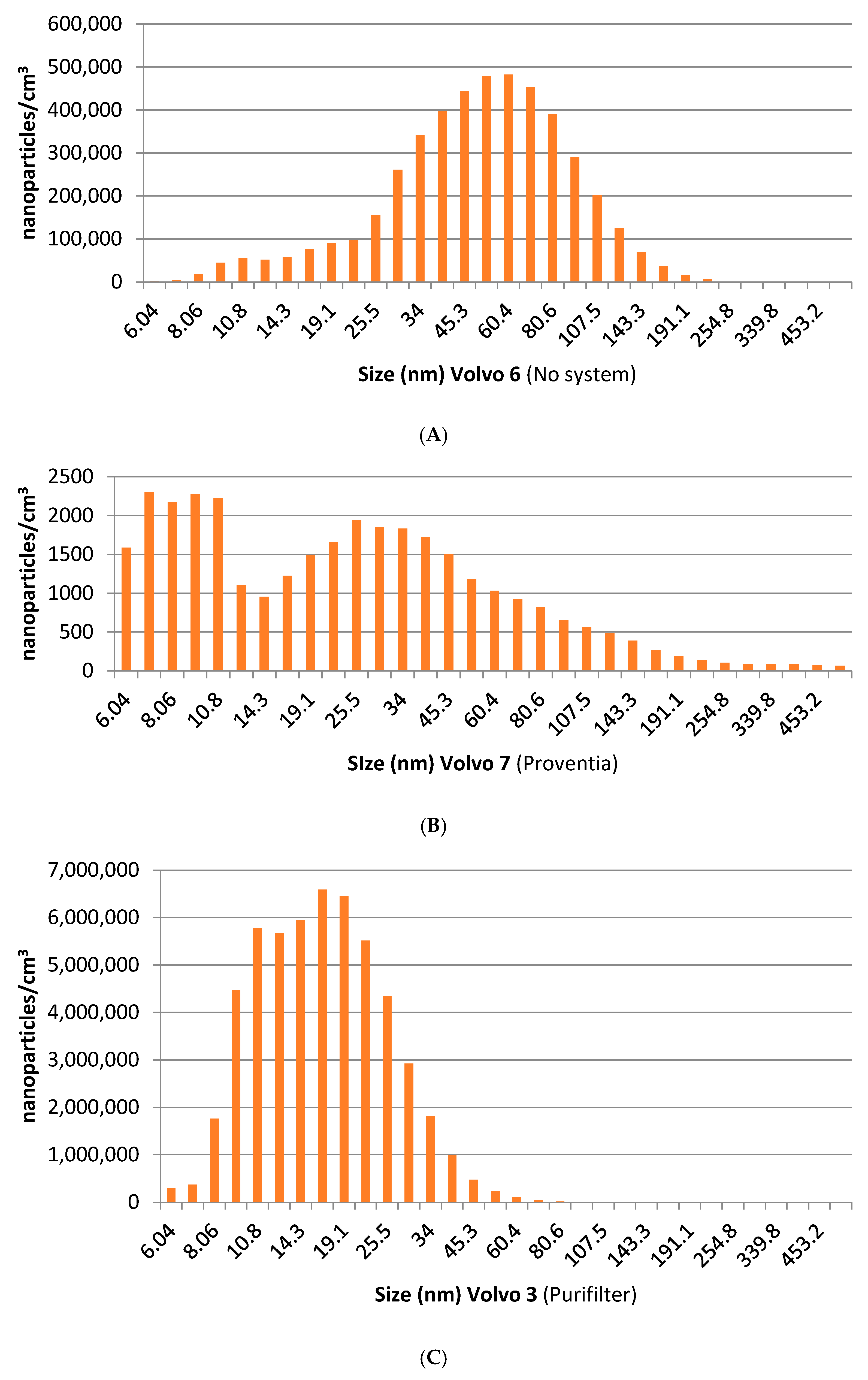

3.2. Nanoparticle Emissions

3.2.1. Idling Conditions

3.2.2. Acceleration Conditions

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CO | Carbon monoxide |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NO2 | Nitrogen dioxide |

| UFP | Ultrafine particle |

| SCR | Selective catalytic reduction |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| DPM | Diesel particulate matter |

| OEL | Occupational exposure limit |

| DPFs | Diesel particulate filters |

| NRMM | Non-road mobile machinery |

| PN | Particle number |

| LHD | Load–Haul–Dump |

| EC | Elemental carbon |

| PSD | Particle size distribution |

| DOC | Diesel Oxidation Catalyst |

| BC | Black Carbon |

Appendix A. Evolution of Gaseous Emissions During Standardised Testing

Appendix A.1. Trucks Without Any Emission Control System (Baseline Condition)

Appendix A.2. Trucks Retrofitted with the Purifilter System

Appendix A.3. Trucks Retrofitted with the Proventia NOxBuster System

References

- Sabanov, S.; Brune, J.; Wang, L.; Korshunova, R.; Qureshi, A.R.; Kuzembayev, N. Analysis of Black Carbon (BC) Concentration Distribution in Relation to Lung-Deposited Surface Area (LDSA) Measured in the Operational Drift of the Underground Metalliferous Mine. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantrel, B.; Rubow, K.; Watts, W.; Bagley, S.; Carlson, D. Pollutant Levels in Underground Coal Mines Using Diesel Equipment; Littleton: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. IARC Diesel Engine Exhaust Carcinogenic; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- Azam, S.; Liu, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Zheng, S. Assessing the Hazard of Diesel Particulate Matter (DPM) in the Mining Industry: A Review of the Current State of Knowledge. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2004/37/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the Protection of Workers from the Risks Related to Exposure to Carcinogens or Mutagens at Work (Sixth Individual Directive Within the Meaning of Article 16(1) of Council Directive 89/391/EEC) (Codified Version) (Text with EEA Relevance). 2004, Volume 158. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02004L0037-20220405&from=EN (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Directive (EU) 2019/130 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 January 2019 Amending Directive 2004/37/EC on the Protection of Workers from the Risks Related to Exposure to Carcinogens or Mutagens at Work (Text with EEA Relevance). 2019, Volume 030. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019L0130 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Commission Directive (EU) 2017/164 of 31 January 2017 Establishing a Fourth List of Indicative Occupational Exposure Limit Values Pursuant to Council Directive 98/24/EC, and Amending Commission Directives 91/322/EEC, 2000/39/EC and 2009/161/EU (Text with EEA Relevance). 2017, Volume 027. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2017/164/oj/eng (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Garcia-Gonzalez, H.; Rodriguez, R.; Bascompta, M. Nitrogen Dioxide Gas Levels in TBM Tunnel Construction with Diesel Locomotives Based on Directive 2017/164/EU. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.U.; Gillies, A.D.S. 11-Diesel Particulate Matter: Monitoring and Control Improves Safety and Air Quality. In Advances in Productive, Safe, and Responsible Coal Mining; Hirschi, J., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 199–213. ISBN 978-0-08-101288-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bugarski, A.D.; Hummer, J.A.; Vanderslice, S.; Barone, T. Retrofitting and Re-Powering as a Control Strategies for Curtailment of Exposure of Underground Miners to Diesel Aerosols. Min. Metall. Explor. 2020, 37, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Non-Road Mobile Machinery. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/automotive-industry/environmental-protection/non-road-mobile-machinery_en (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Hagan, R.; Markey, E.; Clancy, J.; Keating, M.; Donnelly, A.; O’Connor, D.J.; Morrison, L.; McGillicuddy, E.J. Non-Road Mobile Machinery Emissions and Regulations: A Review. Air 2023, 1, 14–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumah, E.A.; Fopa, R.D.; Harati, S.; Boadu, P.; Zohoori, F.V.; Pak, T. Human and Environmental Impacts of Nanoparticles: A Scoping Review of the Current Literature. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeom, S.; Kim, H.; Hong, T.; Jeong, K. Analysis of Ways to Reduce Potential Health Risk from Ultrafine and Fine Particles Emitted from 3D Printers in the Makerspace. Indoor Air 2022, 32, e13053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, V.; Pourchez, J.; Pélissier, C.; Audignon Durand, S.; Vergnon, J.-M.; Fontana, L. Relationship between Occupational Exposure to Airborne Nanoparticles, Nanoparticle Lung Burden and Lung Diseases. Toxics 2021, 9, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-003422-8.

- Kangas, A.; Kukko, K.; Kanerva, T.; Säämänen, A.; Akmal, J.S.; Partanen, J.; Viitanen, A.-K. Workplace Exposure Measurements of Emission from Industrial 3D Printing. Ann. Work Expo. Health 2023, 67, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gonzalez, H.; Lopez-Pola, M.T. Unlocking the Nanoparticle Emission Potential: A Study of Varied Filaments in 3D Printing. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 31188–31200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumchev, K.; Hoang, D.V.; Lee, A. Trends in Exposure to Diesel Particulate Matter and Prevalence of Respiratory Symptoms in Western Australian Miners. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gren, L.; Krais, A.M.; Assarsson, E.; Broberg, K.; Engfeldt, M.; Lindh, C.; Strandberg, B.; Pagels, J.; Hedmer, M. Underground Emissions and Miners’ Personal Exposure to Diesel and Renewable Diesel Exhaust in a Swedish Iron Ore Mine. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2022, 95, 1369–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, P.A.; Coble, J.B.; Vermeulen, R.; Schleiff, P.; Blair, A.; Lubin, J.; Attfield, M.; Silverman, D.T. The Diesel Exhaust in Miners Study: I. Overview of the Exposure Assessment Process. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2010, 54, 728–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, M.K.; Mensah-Darkwa, K.; Drebenstedt, C.; Annam, B.V.; Armah, E.K. Occupational Respirable Mine Dust and Diesel Particulate Matter Hazard Assessment in an Underground Gold Mine in Ghana. J. Health Pollut. 2020, 10, 200305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanatidis, S.; Ntziachristos, L.; Giechaskiel, B.; Bergmann, A.; Samaras, Z. Impact of Selective Catalytic Reduction on Exhaust Particle Formation over Excess Ammonia Events. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 11527–11534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herner, J.D.; Hu, S.; Robertson, W.H.; Huai, T.; Chang, M.-C.O.; Rieger, P.; Ayala, A. Effect of Advanced Aftertreatment for PM and NOx Reduction on Heavy-Duty Diesel Engine Ultrafine Particle Emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 2413–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, S.; Thomson, E.M.; Kumarathasan, P.; Guénette, J.; Rosenblatt, D.; Chan, T.; Rideout, G.; Vincent, R. Nitrogen Dioxide and Ultrafine Particles Dominate the Biological Effects of Inhaled Diesel Exhaust Treated by a Catalyzed Diesel Particulate Filter. Toxicol. Sci. 2013, 135, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugarski, A.D.; Ritter, D.A. Advanced Diesel Powertrains for Underground Mining Mobile Equipment. Min. Metall. Explor. 2025, 42, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, W. Urea-SCR Temperature Investigation for NOx Control of Diesel Engine. MATEC Web Conf. 2015, 26, 03002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Liu, J.; Sun, P.; Wan, Y.; Fan, Y.; Xiao, X. Experimental Investigation on Particle Number Emission from Diesel Engine with Bipolar Discharge Coagulation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D 2019, 233, 1524–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischman, R.; Amiel, R.; Czerwinski, J.; Mayer, A.; Tartakovsky, L. Buses Retrofitting with Diesel Particle Filters: Real-World Fuel Economy and Roadworthiness Test Considerations. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 67, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, N.; Godri Pollitt, K.J.; Jeong, C.-H.; Wang, J.M.; Jung, T.; Cooper, J.M.; Wallace, J.S.; Evans, G.J. Comparison of Three Nanoparticle Sizing Instruments: The Influence of Particle Morphology. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 86, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proventia. Emission Control, Thermal Components & Batteries; Proventia: Oulu, Finland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kotek, M. Analysis of Particulate Matter Production during DPF Service Regeneration. In Proceedings of the TAE 2019-Proceeding of 7th International Conference on Trends in Agricultural Engineering, Prague, Czech Republic, 17–20 September 2019; Volume 2019, pp. 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, O.P.; Lüers, B.; Heuser, B.; Holderbaum, B.; Pischinger, S. Fuel Formulation Effects on the Soot Morphology and Diesel Particulate Filter Regeneration in a Future Optimized High-Efficiency Combustion System. Int. J. Engine Res. 2017, 18, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guse, D.; Roehrich, H.; Lenz, M.; Pischinger, S. Influence of Vehicle Operators and Fuel Grades on Particulate Emissions of an SI Engine in Dynamic Cycles; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2018; p. 2018-01-0350. [Google Scholar]

- Boriboonsomsin, K.; Durbin, T.; Scora, G.; Johnson, K.; Sandez, D.; Vu, A.; Jiang, Y.; Burnette, A.; Yoon, S.; Collins, J.; et al. Real-World Exhaust Temperature Profiles of on-Road Heavy-Duty Diesel Vehicles Equipped with Selective Catalytic Reduction. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 909–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittelson, D.B.; Pipho, M.J.; Ambs, J.L.; Luo, L. In-Cylinder Measurements of Soot Production in a Direct-Injection Diesel Engine. SAE Trans. 1988, 97, 513–530. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, B.; Zhan, R.; Lin, H.; Huang, Z. Review of the State-of-the-Art of Exhaust Particulate Filter Technology in Internal Combustion Engines. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 154, 225–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Naseri, M.; Aydin, C. Demonstration of SCR on a Diesel Particulate Filter System on a Heavy Duty Application; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Noll, J.D.; Mischler, S.; Cauda, E.; Patts, L.; Janisko, S.; Grau, R. The Effects of Passive Diesel Particulate Filters on Diesel Particulate Matter Concentrations in Two Underground Metal/Non-Metal Mines. In Proceedings of the 13th United States/North American Mine Ventilation Symposium, Sudbury, ON, Canada, 13–16 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Damayanti, S.; Harrison, R.M.; Pope, F.; Beddows, D.C.S. Limited Impact of Diesel Particle Filters on Road Traffic Emissions of Ultrafine Particles. Environ. Int. 2023, 174, 107888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gas | Range | Accuracy | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO | 0–10,000 ppm | ±5% | 1 ppm |

| NO | 0–4000 ppm | ±5% | 1 ppm |

| NO2 | 0–500 ppm | ±5% | 0.1 ppm |

| SO2 | 0–5000 ppm | ±5% | 1 ppm |

| CO2 | 0–50% vol | ±0.3% vol | 0.01% vol |

| Truck ID | POWER (kW) | Year | System | CO | NO | NO2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ppm) [Range] | Reduction (%) * | (ppm) [Range] | Reduction (%) * | (ppm) [Range] | Reduction (%) * | ||||

| Volvo nº6 BM | 148 | 2001 | None | 96 [73–261] | - | 230 [138–256] | - | 23 [17–33] | - |

| Volvo nº8 BM | 148 | -- | None | 350 [151–776] | - | 397 [167–531] | - | 39 [9–80] | - |

| Volvo nº2 BM | 148 | 1990 | Proventia NOxBuster | 0 [0–4] | 100 | 51 [2–136] | 77.83 | 4 [1–25] | 82.61 |

| Volvo nº2 BM | 148 | 1990 | Proventia NOxBuster | 6 [0–154] | 93.75 | 44 [0–140] | 80.87 | 12 [0–77] | 47.83 |

| Volvo nº7 BM | 148 | 1990 | Proventia NOxBuster | 6 [0–22] | 93.75 | 112 [22–271] | 51.3 | 7 [0–56] | 69.57 |

| Volvo nº3 BM | 148 | 1991 | Purifilter | 20 [0–42] | 79.17 | 20 [0–136] | 91.3 | 3 [0–23] | 86.96 |

| Volvo nº3 BM | 148 | 1991 | Purifilter | 35 [10–74] | 63.54 | 100 [6–229] | 56.52 | 14 [1–63] | 39.13 |

| Volvo nº3 BM | 148 | 1991 | Purifilter | 18 [0–34] | 81.25 | 86 [0–215] | 62.61 | 18 [2–87] | 21.74 |

| Volvo nº5 BM | 148 | 1988 | Purifilter | 30 [19–61] | 68.75 | 61 [1–149] | 73.48 | 6 [0–29] | 73.91 |

| Year | Truck | System | Dilution Factor | Nanoparticles/cm3 | % Reduction | Engine Speed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.6–23 nm | 23–560 nm | Total | ||||||

| 2001 | Volvo nº6 BM | - | 49 | 542,400 | - | - | - | Idling |

| 1990 | Volvo nº7 | Proventia NOxBuster | 49 | 43,365 | 79.07% | 94.89% | 92.09% | Idling |

| 1990 | Volvo nº2 | Proventia NOxBuster | 49 | 34,955 | 78.63% | 96.85% | 93.62% | Idling |

| 1991 | Volvo nº3 | Purifilter | 49 | 49,691 | 59.24% | 97.76% | 90.94% | Idling |

| 1988 | Volvo nº5 | Purifilter | 49 | 37,472 | 72.79% | 97.55% | 93.16% | Idling |

| Year | Truck | System | Dilution Factor | Nanoparticles/cm3 | % Reduction | Engine Speed | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5.6–40 nm | 40–560 nm | Total | ||||||

| 2001 | Volvo nº6 BM | - | 49 | 4,645,965 | - | - | - | Accelerate |

| 1990 | Volvo nº7 | Proventia NOxBuster | 49 | 32,972 | 98.53% | 99.71% | 99.29% | Accelerate |

| 1990 | Volvo nº2 | Proventia NOxBuster | 49 | 184,701 | 90.14% | 99.28% | 96.02% | Accelerate |

| 1991 | Volvo nº3 | Purifilter | 49 | 53,794,388 | −3101.33% | 70.95% | −1057.9% | Accelerate |

| 1988 | Volvo nº5 | Purifilter | 49 | 6,931,970 | −313.62% | 96.86% | −49.20% | Accelerate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garcia-Gonzalez, H.; Menendez-Cabo, P. Evaluation of Emission Reduction Systems in Underground Mining Trucks: A Case Study at an Underground Mine. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040107

Garcia-Gonzalez H, Menendez-Cabo P. Evaluation of Emission Reduction Systems in Underground Mining Trucks: A Case Study at an Underground Mine. Clean Technologies. 2025; 7(4):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040107

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcia-Gonzalez, Hector, and Pablo Menendez-Cabo. 2025. "Evaluation of Emission Reduction Systems in Underground Mining Trucks: A Case Study at an Underground Mine" Clean Technologies 7, no. 4: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040107

APA StyleGarcia-Gonzalez, H., & Menendez-Cabo, P. (2025). Evaluation of Emission Reduction Systems in Underground Mining Trucks: A Case Study at an Underground Mine. Clean Technologies, 7(4), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040107