A Systematic Review of Urban Air Mobility Development: eVTOL Drones’ Technological Challenges and Low-Altitude Policies of Shenzhen

Highlights

- A systematic analysis of the multidimensional technical bottlenecks and systemic challenges for eVTOL drones in Urban Air Mobility (UAM) is conducted, identifying critical issues in aerodynamics, structure, energy, navigation, redundancy control, and safety.

- The complementary relationship between technological challenges and low-altitude policies in Shenzhen is revealed, highlighting its advantages in efficient flight approval and large-scale takeoff-landing infrastructure, leading to development suggestions from technology, infrastructure, industrial ecology, and regional coordination.

- Taking Shenzhen as an example, this paper explores the research progress and development trends of urban air mobility in big cities based on eVTOL, revealing the technical pain points and policy bottlenecks of urban air mobility, as well as their interrelationships. This can promote technological development of urban air mobility and shorten its path of commercialization expansion.

- A concrete development roadmap for Shenzhen is proposed, emphasizing coordinated advancement in technology R&D, infrastructure, regulation, and regional cooperation to establish a global benchmark for UAM implementation.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Low-Altitude Technology Challenges in Urban Air Mobility

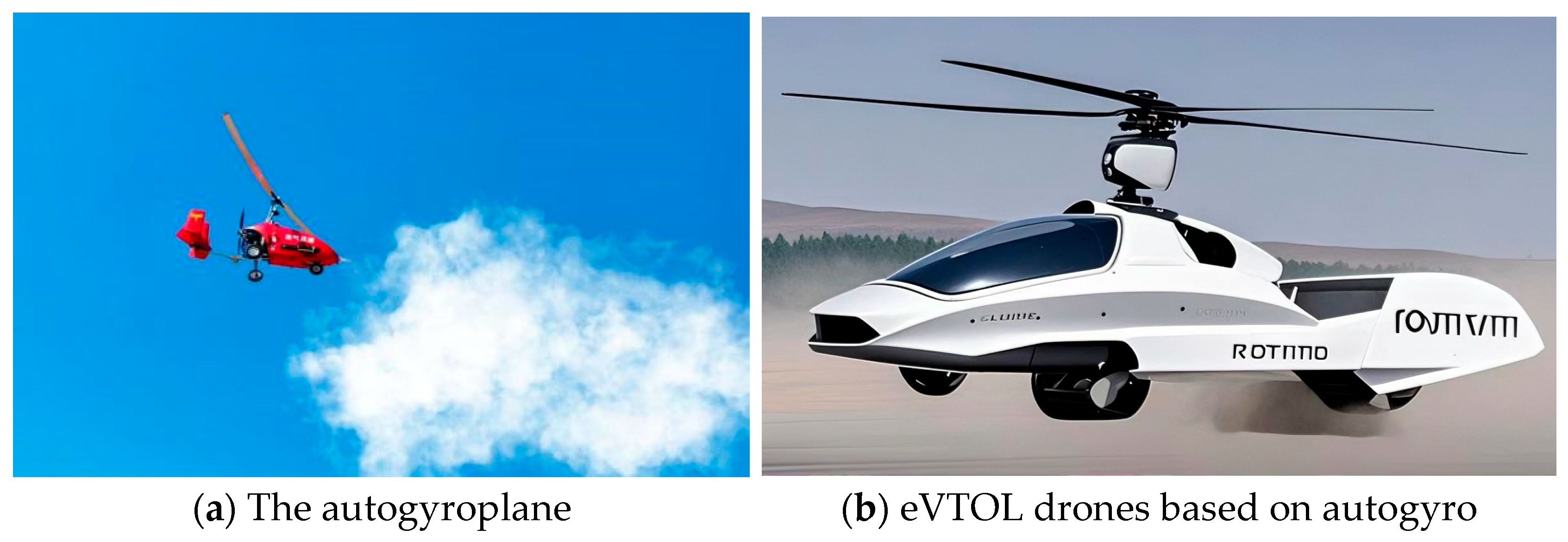

2.1. Technical Challenges of eVTOL Drones

2.1.1. Technical Challenges in eVTOL Drone Design and Development

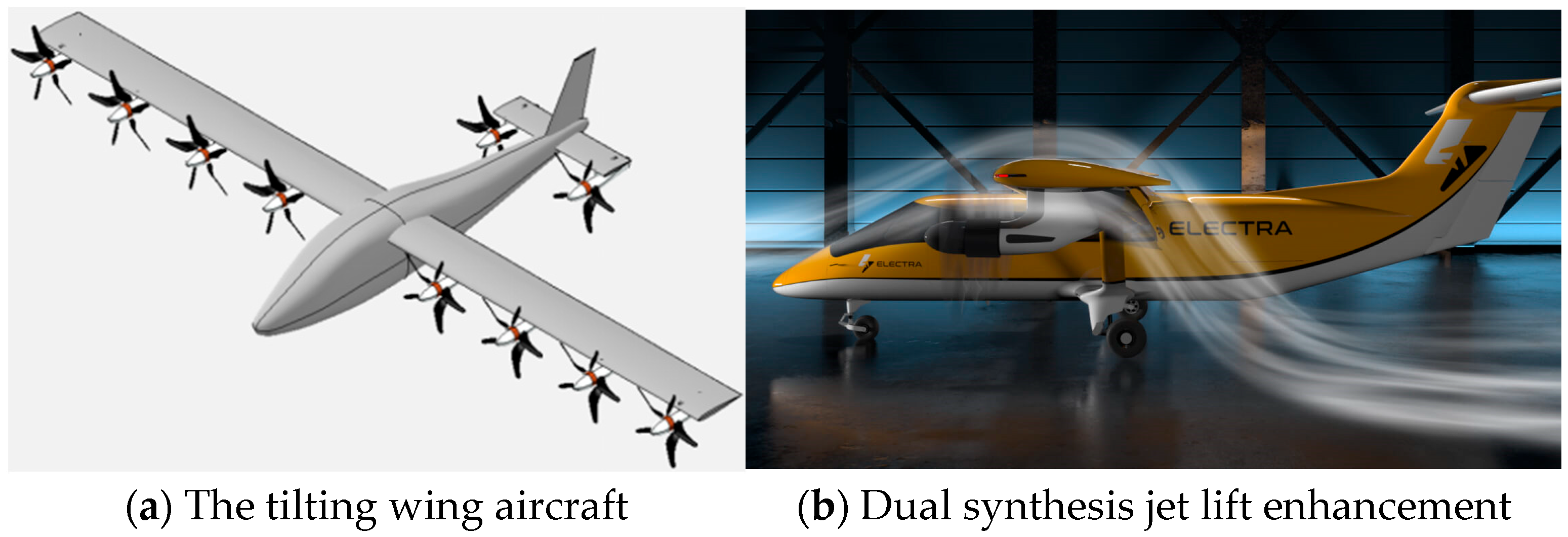

Efficient Aerodynamics of Distributed Power

Lightweight and High-Strength Multi-Rotor Structure

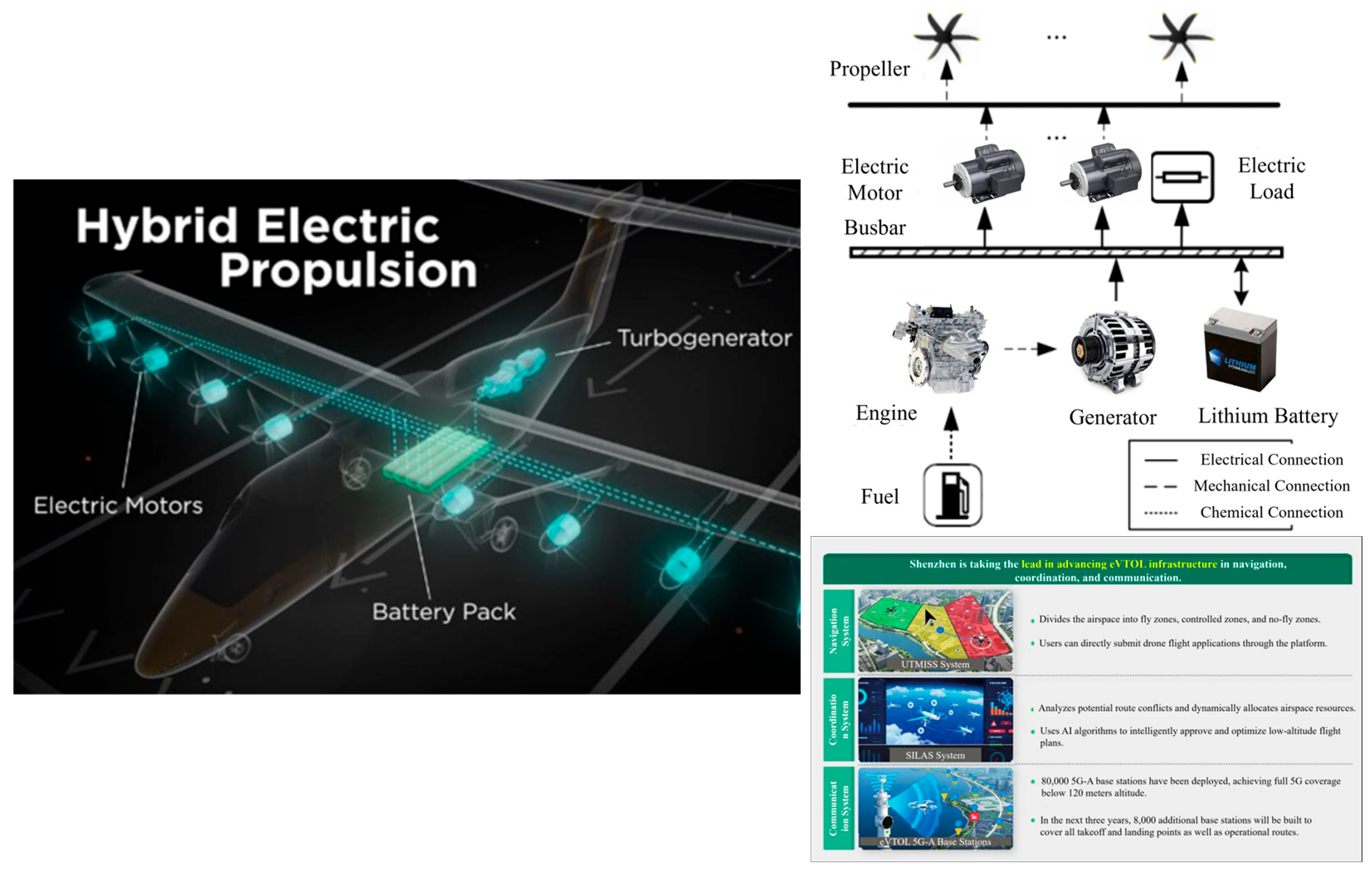

Efficient Motor/Propeller Power System Design

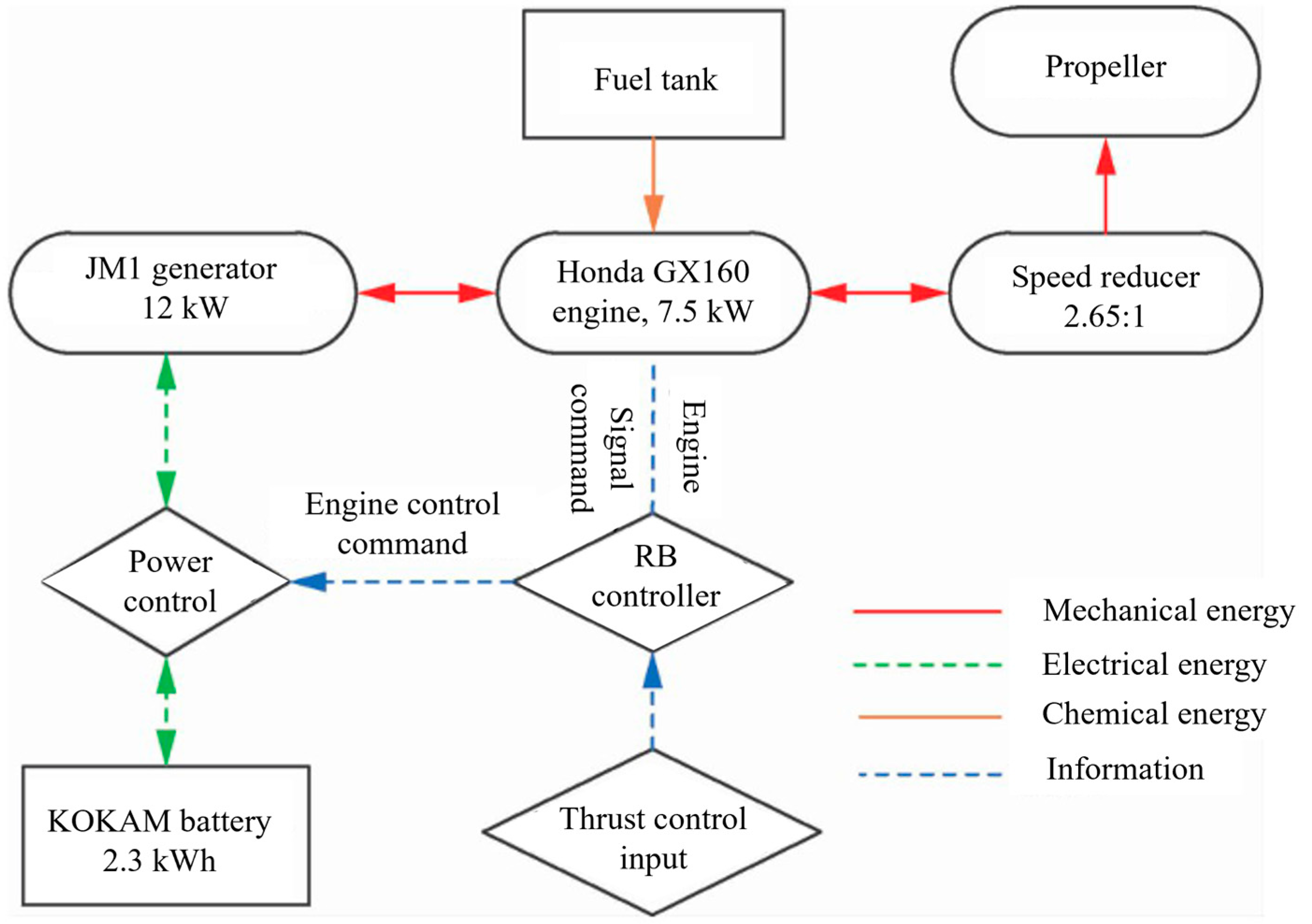

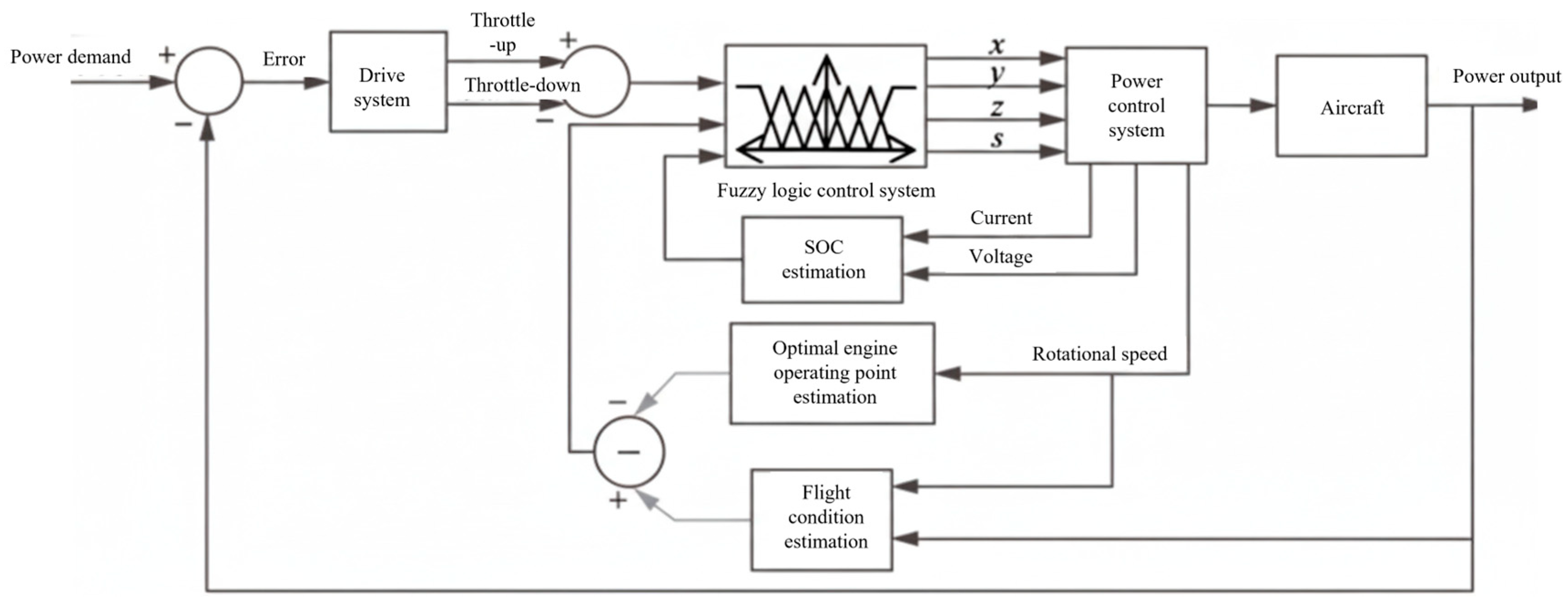

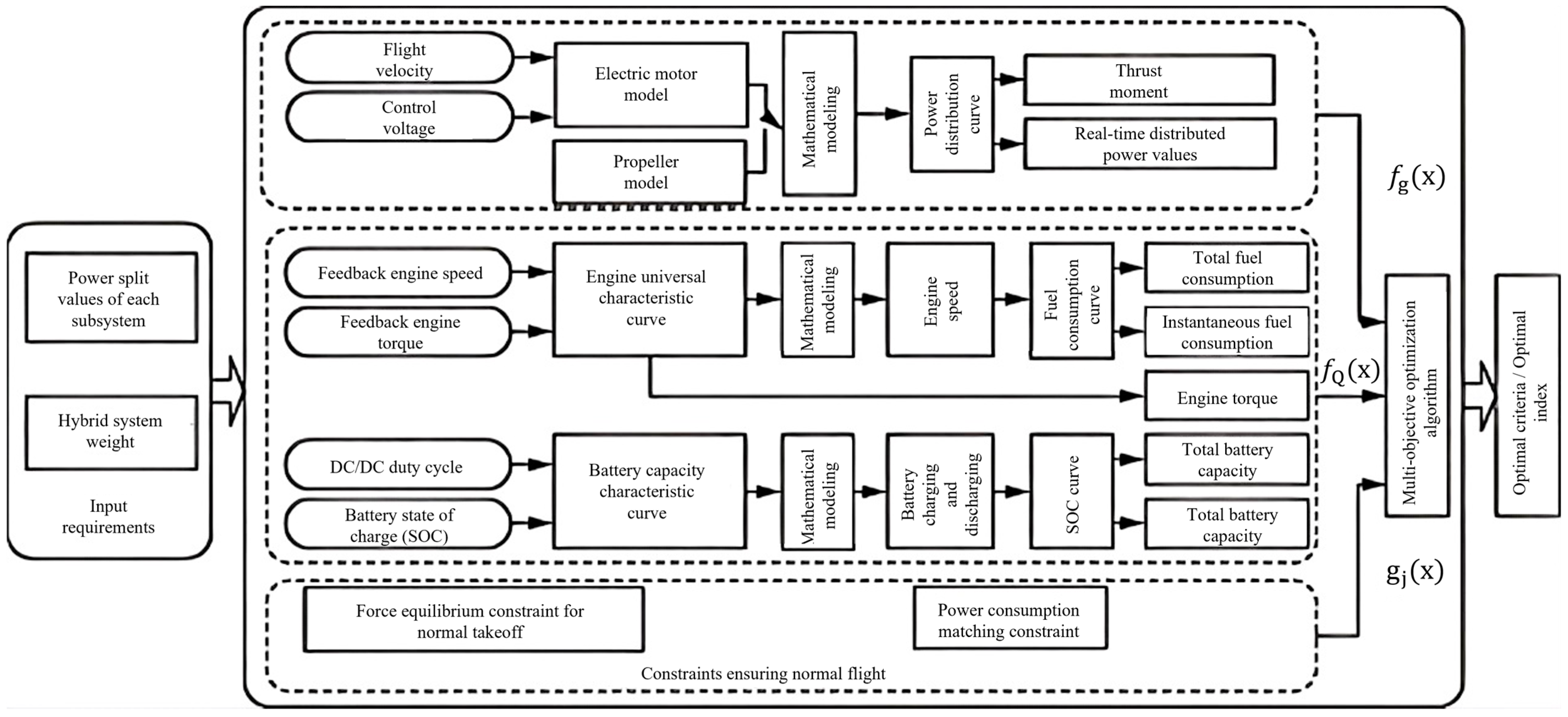

Energy Management and Optimization

2.1.2. Technical Focus Related to Flight Safety

Assessment and Application of Power Energy Security

Redundancy Flight Control

Efficient Autonomous Obstacle Avoidance

Maintenance Guarantee

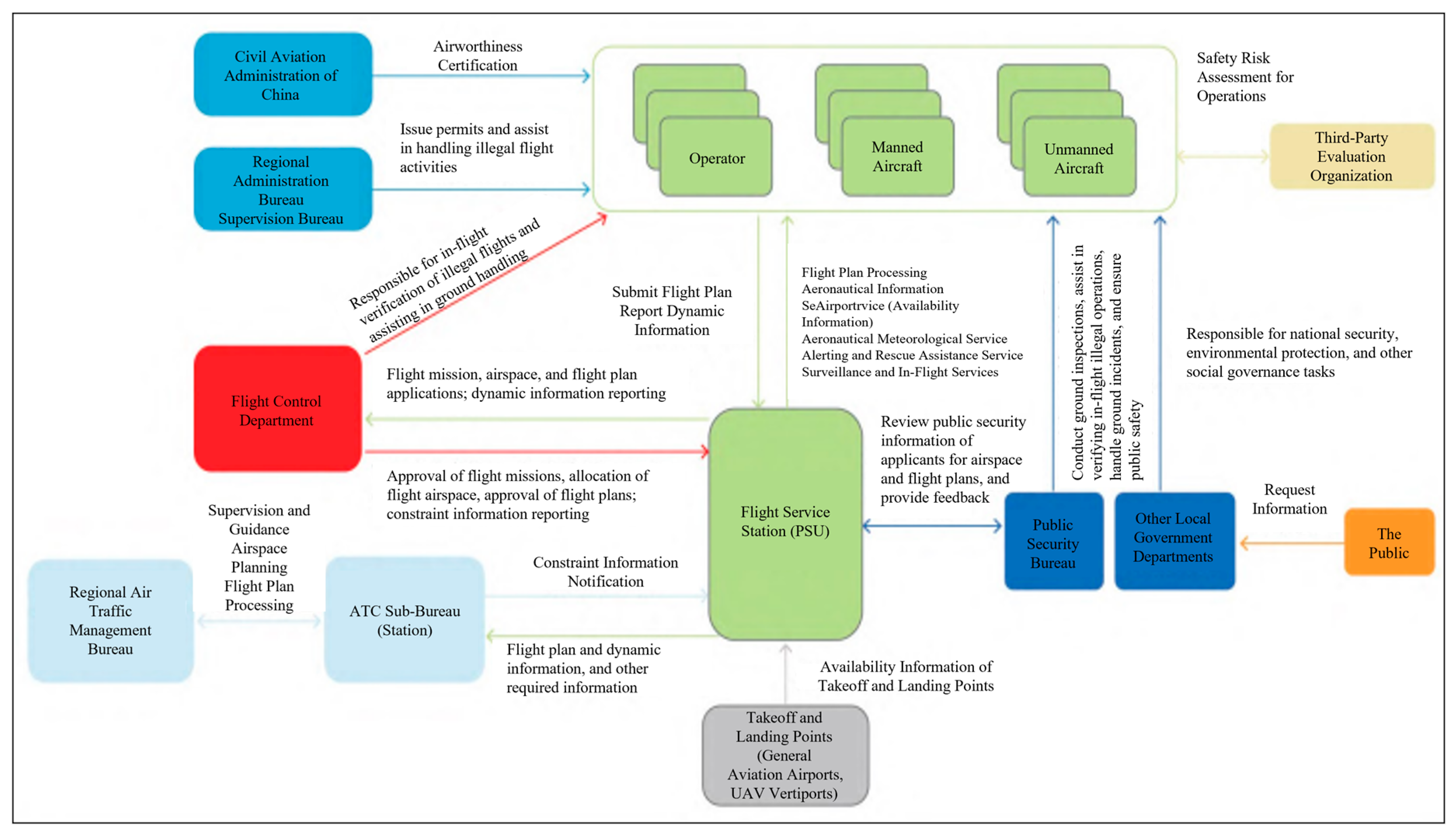

2.2. Supervision Technology for Urban Air Mobility

2.2.1. Technical Requirements for Regulatory System

2.2.2. Standards and Specifications for the Use of Various Low-Altitude Aircraft

2.2.3. Regulatory and Communication System Linkage Technology

2.2.4. Low-Altitude Route Management Technology

2.2.5. Rapid Scheduling Management Technology

2.3. Infrastructure Technology

2.3.1. Technological Progress in Design and Construction of Takeoff and Landing Sites

Technologies and Standards for Civil Engineering and Infrastructure Construction

- (1)

- Layout and Site Selection of Vertical Takeoff Airports

- (2)

- Design of Vertical Takeoff Airports

Landing Site Communication Technology

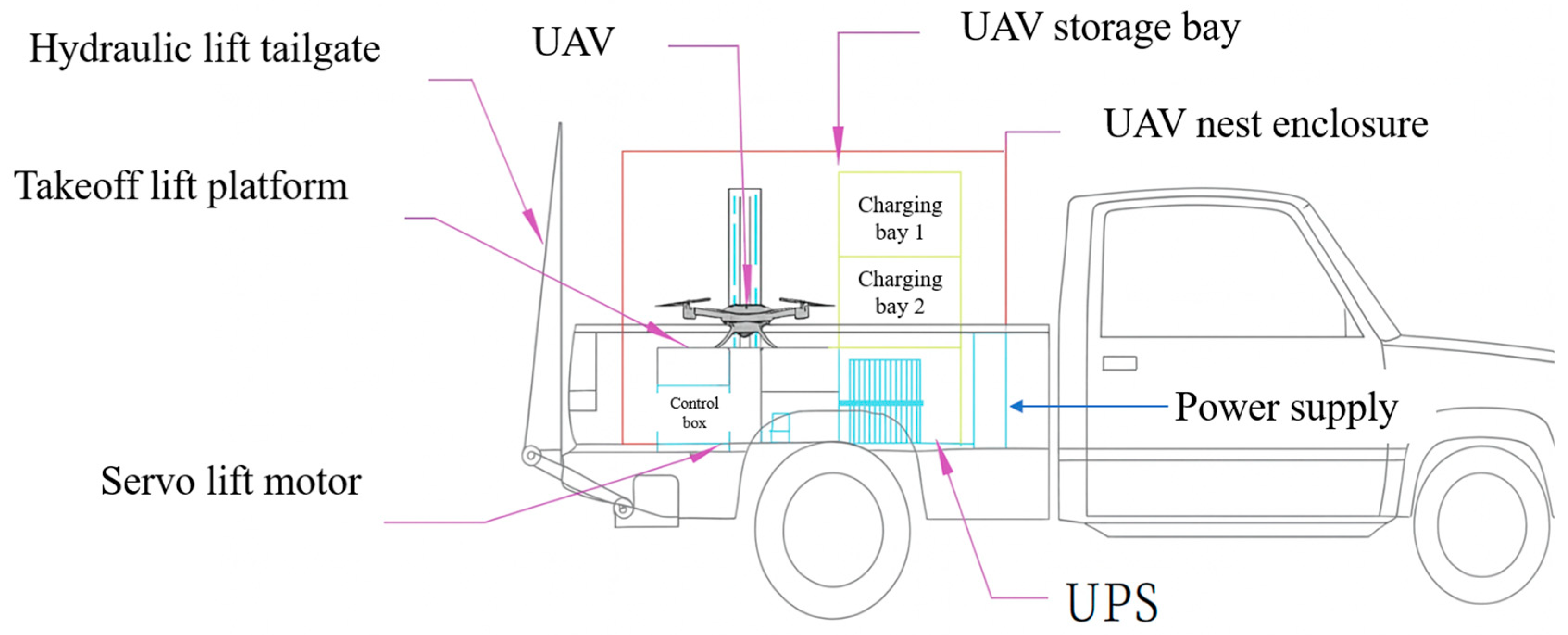

Design and Construction Technology of Machine Nest

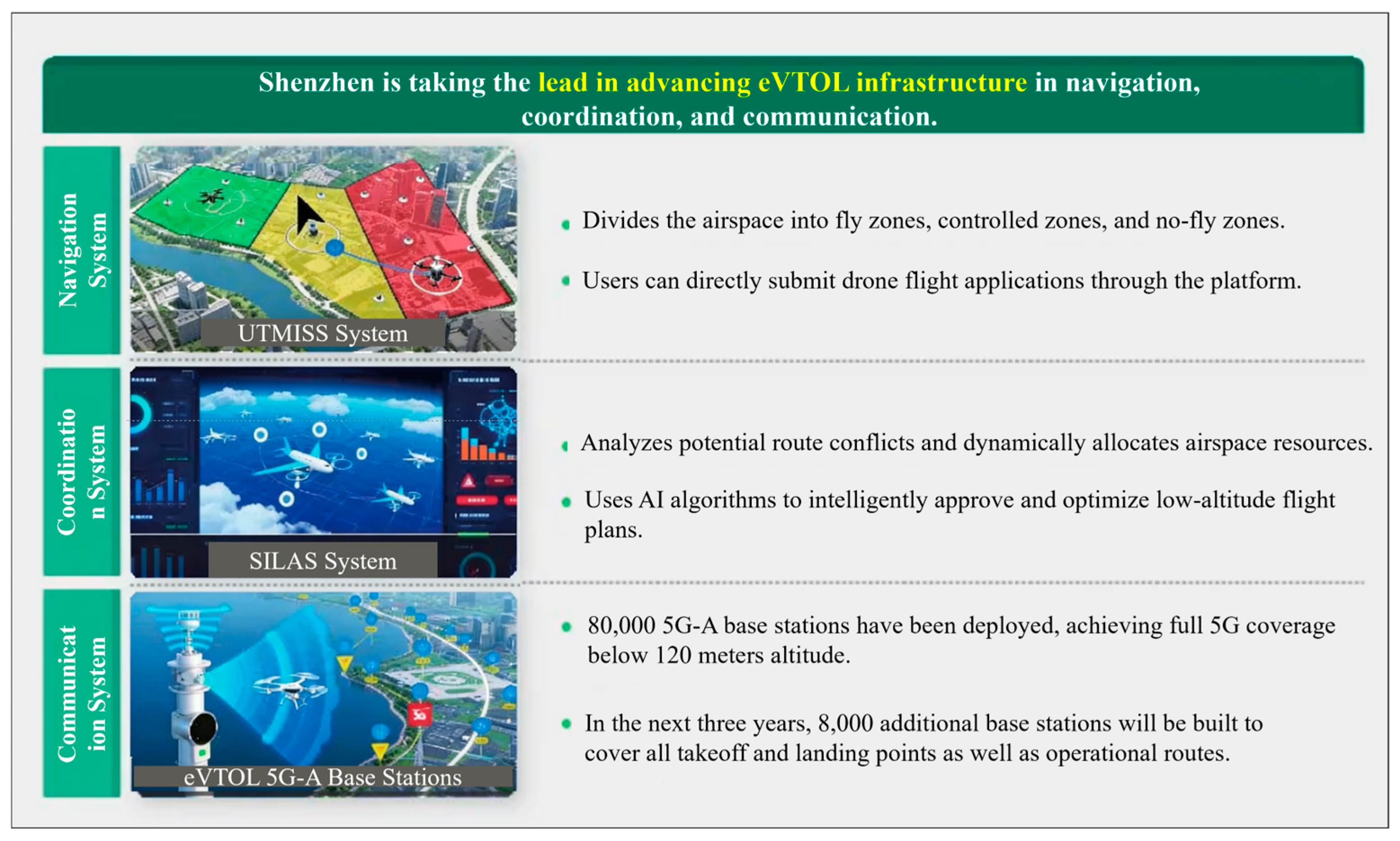

2.3.2. Progress of Urban Air Mobility Management System Infrastructure

3. Low-Altitude Economic Policy Advancement and Influence of Urban Air Mobility

3.1. Low-Altitude Economic Policies for Urban Air Mobility

3.1.1. Framework of Shenzhen’s Low-Altitude Economic Policy System

3.1.2. Progress of Policy Release in Core Areas

Aircraft Development and Support

Low-Altitude Infrastructure Construction

Low-Altitude Economic Supervision Mechanism

Cultivation of Low-Altitude Economic Industry Chain

3.2. Impact of Economic Policies on Low-Altitude Aircraft Technology and Industry Status

3.2.1. The Incubation Effect of UAM Policies on Enterprises

Multidimensional Incubation Support Driven by Policies

3.2.2. UAM Policy Promotes the Updating and Iteration of Technological Products

Corresponding Relationship Between Policy Guidance and Enterprise Technology Product Iteration

Supporting Achievements of Technological Iteration: Financing and Industrial Scale

Infrastructure Support for Takeoff and Landing Sites Under Policy Guidance

3.2.3. Policy Driven Regulatory Situation

Policy Driven Regulatory Policies Are Increasingly Improving

The Construction of Regulatory Standards Continues to Strengthen

- (1)

- Layout of New Infrastructure Construction

- (2)

- Promotion of Low-Altitude Air Route Planning

- (3)

- Improvement of Airspace Utilization Efficiency

3.2.4. UAM Policy and Commercialization Prospects and Model Insights

4. Outlook and Suggestions for Urban Air Mobility in Shenzhen

4.1. Efficient Takeoff and Landing/Endurance Design

4.2. Complex Environment Application Technology

4.3. Airworthiness and Regulatory Policy Trends

4.4. Suggestions for the Development of Urban Air Mobility in Shenzhen

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gipson, L. NASA Embraces Urban Air Mobility, Calls for Market Study; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Volume 7.

- Zhang, H. Development trends and application scenarios of eVTOL aircraft. Air Transp. Bus. 2022, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Qu, W.; Li, Y.; Haung, L.; Wei, P. Overview of traffic management of urban air mobility (UAM) with eVTOL aircraft. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2020, 20, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Chen, X. Key technological innovations and challenges in urban air mobility. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2024, 45, 730657. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S.; Yao, Y. Toward a Future Legal Regulatory Framework for Urban Air Mobility. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 38, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, Y.; Fan, X.; Li, D.; Sun, W.; Huang, L. Review of Research Progress on Electric Propulsion Systems for eVTOL Aircraft. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2025, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Bao, D.; Zhou, J.; Shang, J.; Zhang, Z. Research Status and Prospects of Low-altitude Airspace Planning. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2025, 46, 82–107. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, S.; Zhang, S.; Ding, D. From Low-altitude Management to Low-altitude Governance: Policy Evolution, Research Context, and Forward-looking Trends. J. Xinjiang Normal Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Xu, B. Legalization Path for High-quality Development of the Low-altitude Economy. Jiangsu Soc. Sci. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, W. Global Trends, China’s Status, and Promotion Strategies for Low-altitude Economy Development. Econ. Rev. 2024, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, B.; Xu, J.; Yuan, X.; Yu, S. Active disturbance rejection flight control and simulation of unmanned quad tilt rotor eVTOL drones based on adaptive neural network. Drones 2024, 8, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoser, J.; Cuadrat-Grzybowski, M.; Castro, S.G. Preliminary control and stability analysis of a long-range eVTOL drones aircraft. In Proceedings of the AIAA SCITECH 2022 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 3–7 January 2022; p. 1029. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, E.; German, B.J. Control allocation optimization for an over-actuated tandem tiltwing eVTOL drones aircraft considering aerodynamic interactions. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 155, 109595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, W.; Wang, H. Closed-loop dynamic control allocation for aircraft with multiple actuators. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2013, 26, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sheng, H.; Liu, S.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, H. Adaptive fault-tolerant control of distributed electric propulsion aircraft based on multivariable model predictive control. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Chen, S.; Liu, C. Model predictive control-based trajectory planning for quadrotors with state and input constraints. In Proceedings of the 2016 16th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, 16–19 October 2016; pp. 1618–1623. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, J.; Mei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Su, X. Modified central force optimization (MCFO) algorithm for 3D UAV path planning. Neurocomputing 2016, 171, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCID Research Institute. China Low-Altitude Economy Application Scenarios Research Report; CCID: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

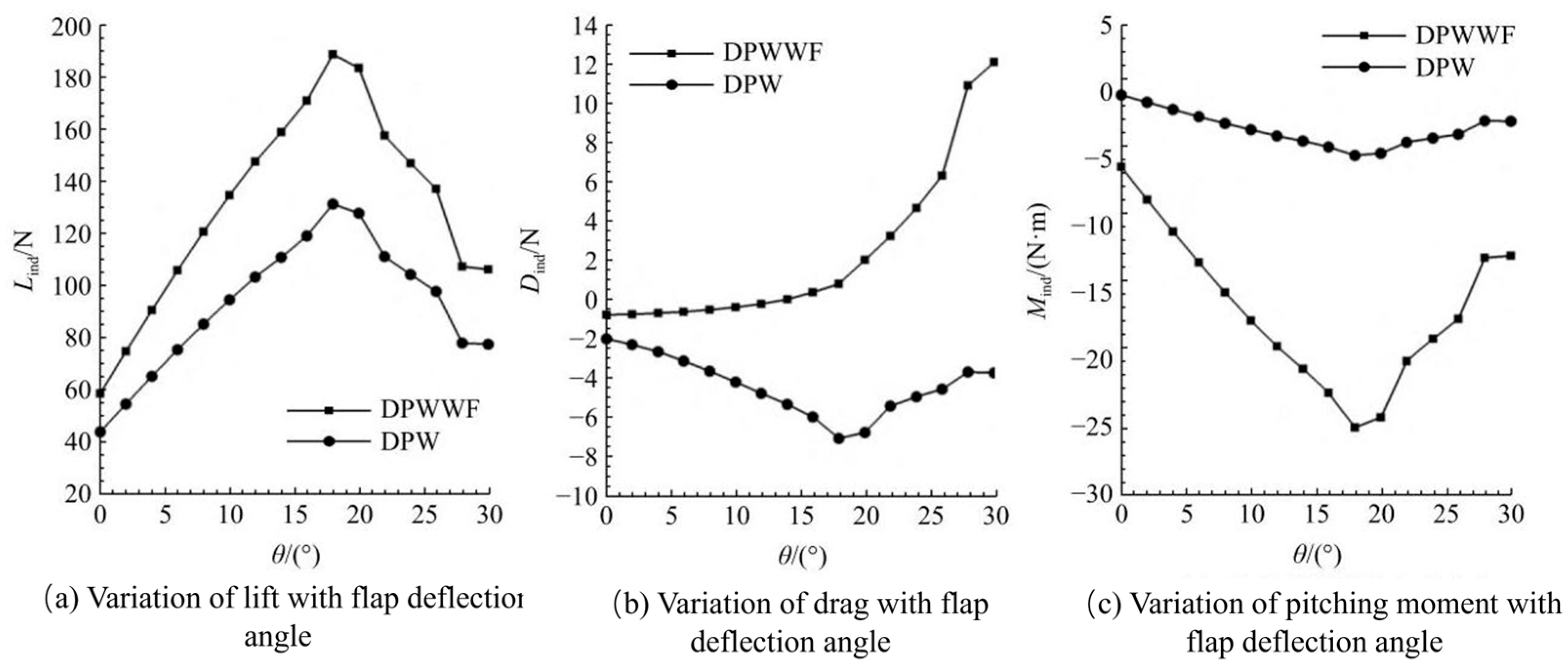

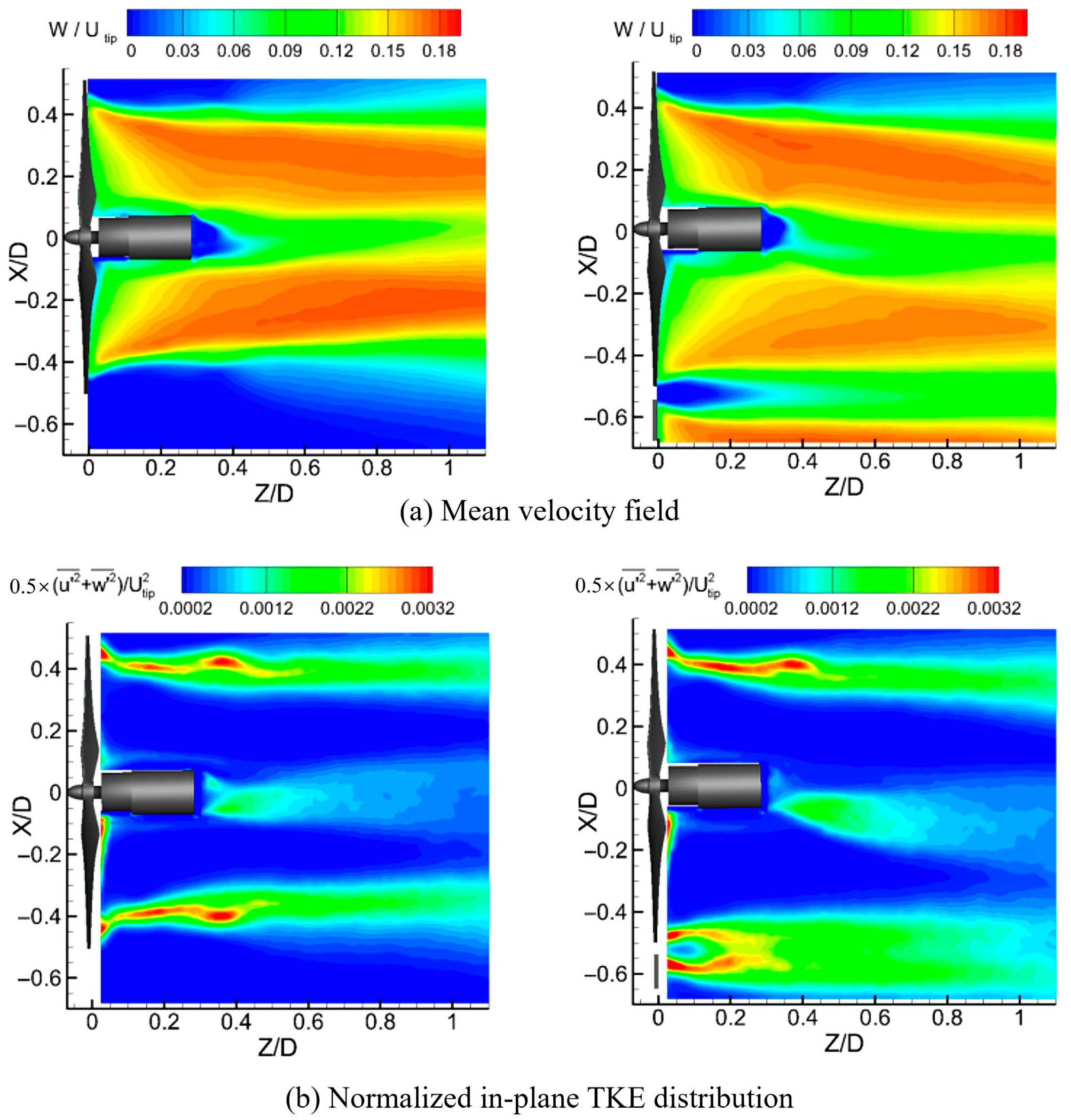

- Minervino, M.; Andreutti, G.; Russo, L.; Tognaccini, R. Drag reduction by wingtip-mounted propellers in distributed propulsion configurations. Fluids 2022, 7, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, R.; Brown, M.; Vos, R. Preliminary sizing method for hybrid-electric distributed-propulsion aircraft. J. Aircr. 2019, 56, 2172–2188. [Google Scholar]

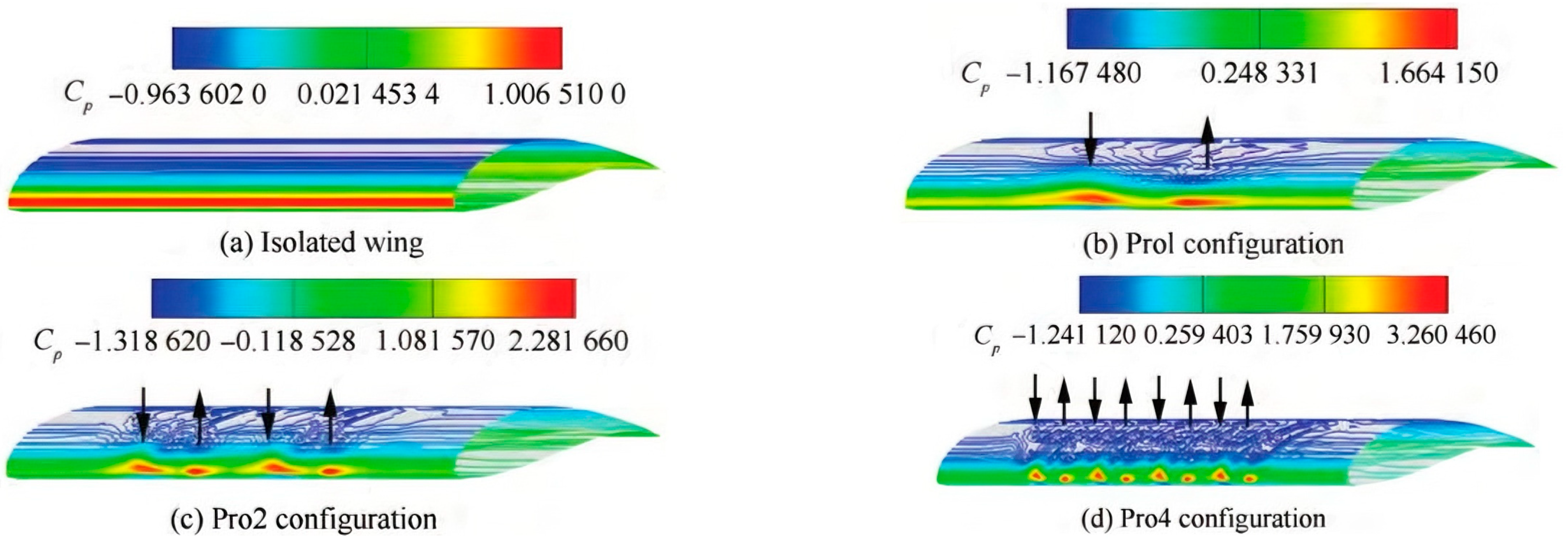

- Wang, K.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, H. Aerodynamic effects of low Reynolds number distributed propeller slipstream. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2016, 37, 2669–2678. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, L.; Zhong, B.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, G. Research on the influence of distributed ducted fans on the aerodynamic characteristics of BWB unmanned aerial vehicles. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

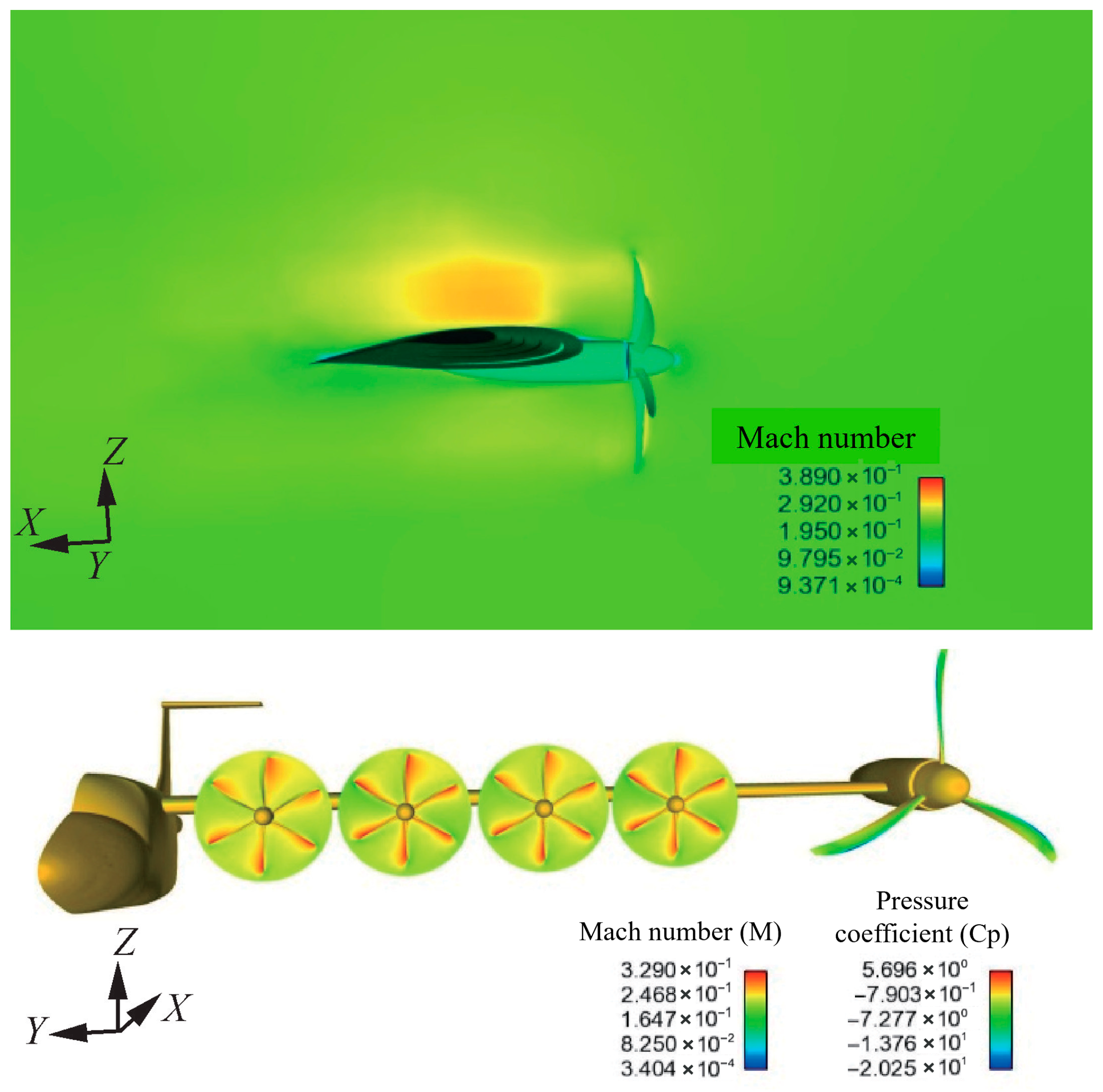

- Xu, D.; Xu, X.; Xia, J.; Zhou, Z. Pneumatic propulsion coupling characteristics of distributed electric propulsion system. J. Aerosp. Power 2024, 39, 188–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo, R.; Cardone, M.; Manna, M.; Vorraro, G. Ducted propeller flow analysis by means of a generalized actuator disk model. Energy Procedia 2014, 45, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Morandini, M.; Li, S. Viscous vortex particle method coupling with computational structural dynamics for rotor comprehensive analysis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kewalramani, P. Modelling of Rotor Wake using Viscous Vortex Particle Method. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.09587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzke, R.; Sebben, S.; Bark, T.; Willeson, E.; Broniewicz, A. Evaluation of the multiple reference frame approach for the modelling of an axial cooling fan. Energies 2019, 12, 2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Xiao, Z.; Ghazialam, H. Evaluation of the Multiple Reference Frame (MRF) model in a truck fan simulation. In SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, C.; Zhang, T.; Wei, C.; Liu, Y. A mechanism of distributed electric aircraft propeller slip influence. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2021, 42, 157–167. [Google Scholar]

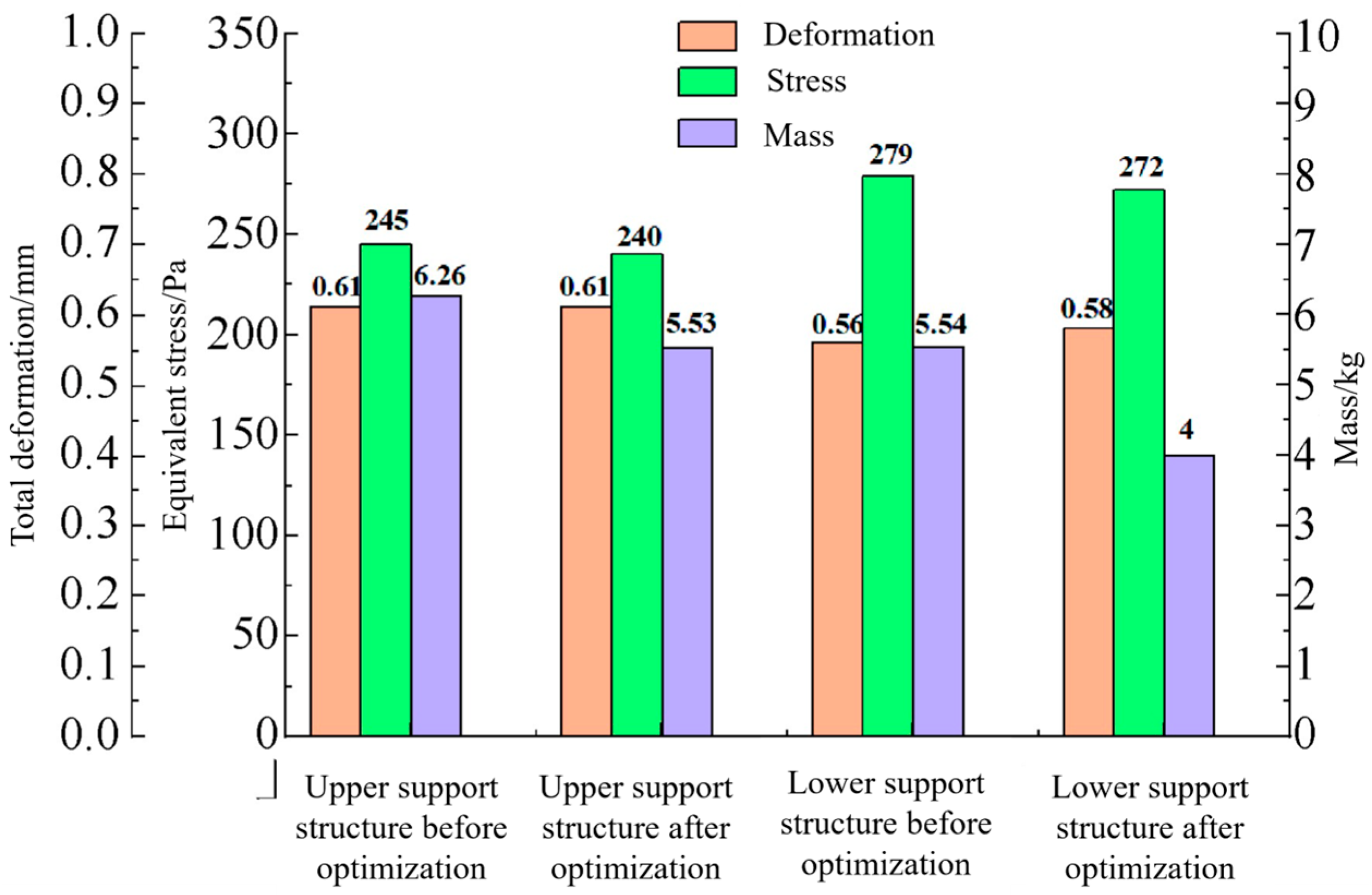

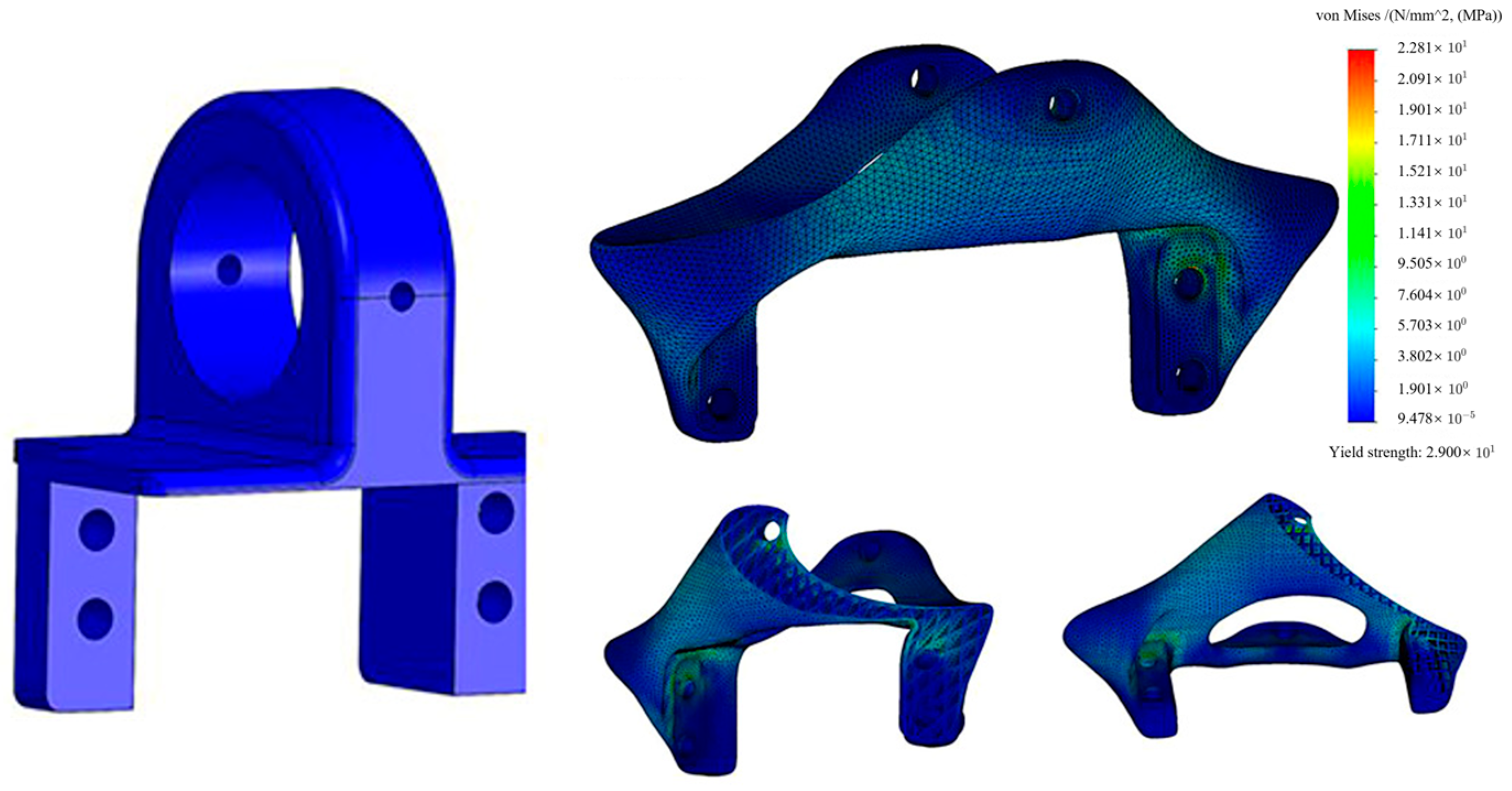

- Ren, S.; Gao, A.; Zhang, Y.; Han, W. Finite element analysis and topology optimization of the folding mechanism of a hexacopter crop protection unmanned aerial vehicle. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2021, 42, 53–58+194. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.; Gong, P.; Ji, S. Lightweight design of multi habitat unmanned aerial vehicle fuselage structure based on topology optimization. Mech. Des. 2024, 41, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, B.; Wu, X.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y. Topological Design of a Hinger Bracket Based on Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2023, 16, 4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klippstein, H.; Hassanin, H.; Diaz De Cerio Sanchez, A.; Zweiri, Z.; Seneviratne, L. Additive manufacturing of porous structures for unmanned aerial vehicles applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2018, 20, 1800290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

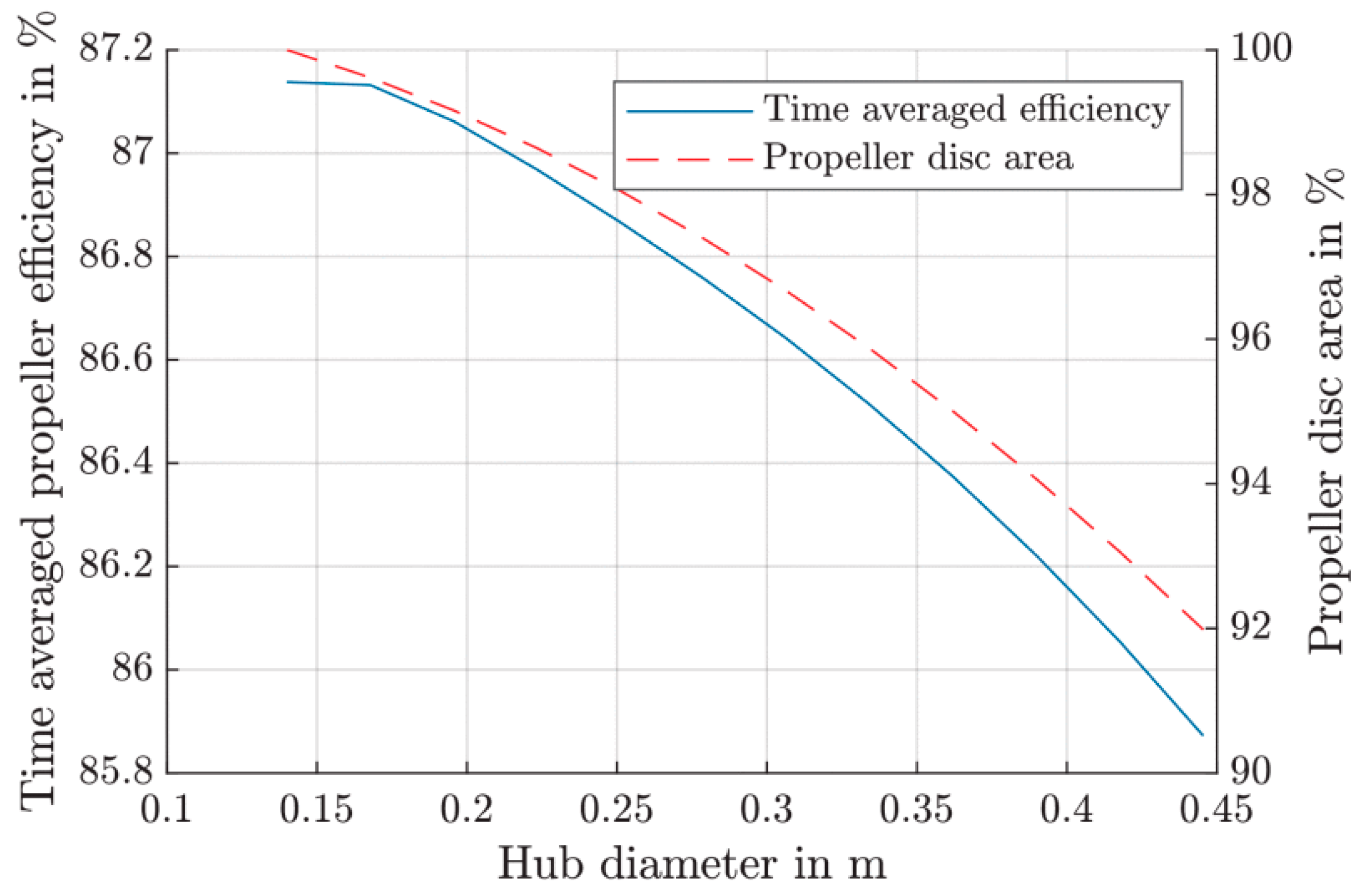

- Keuter, R.J.; Kirsch, B.; Friedrichs, J.; Ponick, B. Design Decisions for a Powertrain Combination of Electric Motor and Propeller for an Electric Aircraft. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 79144–79155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. Research on Optimization and Verification Technology of Efficient Propeller Design for Dynamic Glider. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang Aerospace University, Shenyang, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alba-Maestre, J.; Prud’homme van Reine, K.; Sinnige, T.; Castro, S.G.P. Preliminary propulsion and power system design of a tandem-wing long-range eVTOL drones aircraft. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Ning, Z.; Li, H.; Hu, H. An experimental investigation on rotor-to-rotor interactions of small UAV propellers. In Proceedings of the 35th AIAA Applied Aerodynamics Conference, Denver, CO, USA, 5–9 June 2017; p. 3744. [Google Scholar]

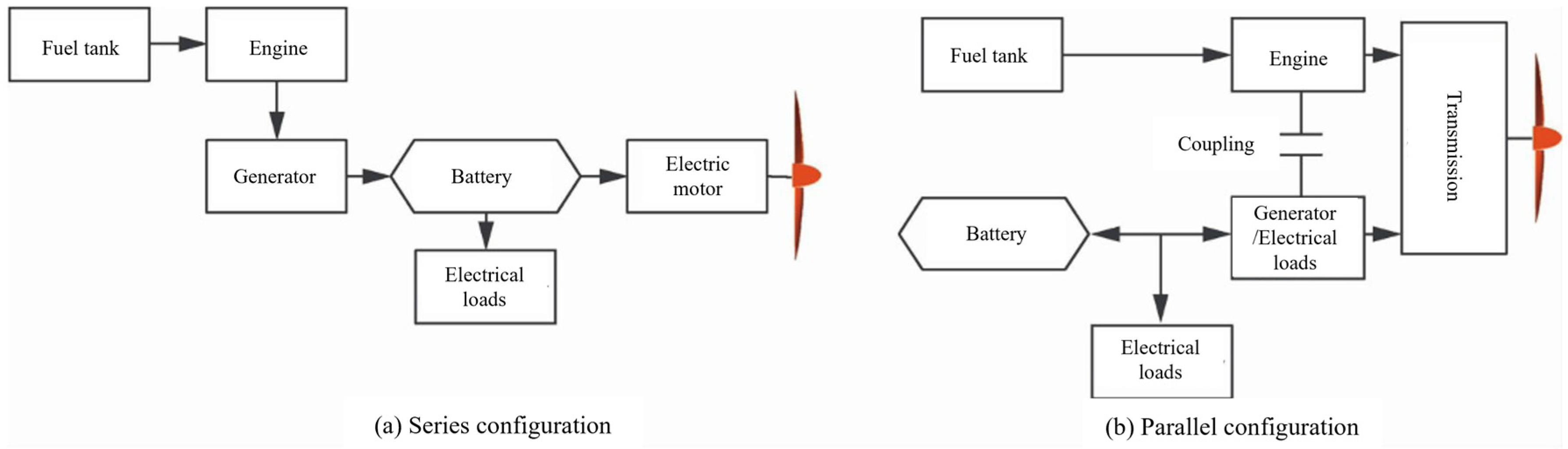

- Zhu, B.; Yang, X.; Zong, J.; Deng, X. Distributed hybrid electric propulsion aircraft technology. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2022, 43, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Hu, Y.; Song, B.; Tan, C. Optimization design and flight time evaluation of electric unmanned aerial vehicle power system. J. Aerosp. Power 2015, 30, 1834–1840. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, Z.J.; Hallock, T.J.; Ozoroski, T.A.; Chapman, J.W.; Kuhnle, C.A.; Frederic, P.C. Design Exploration of a Mild Hybrid Electrified Aircraft Propulsion Concept. In Proceedings of the AIAA AVIATION 2023 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–16 June 2023; p. 4226. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Du, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Xu, G.; Wang, Z. Conceptual design and energy management strategy for UAV with hybrid solar and hydrogen energy. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2016, 37, 144–162. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Qi, X.; Wang, P. EvaTOL aircraft level safety mitigation measures and effect analysis. Civ. Aircr. Des. Res. 2024, 1, 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, M. Balancing battery safety and performance for electric vertical takeoff and landing aircrafts. Device 2023, 1, 100006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, D. Characteristics of lithium batteries in multi-rotor unmanned aerial vehicle applications. Electron. Technol. Softw. Eng. 2018, 15, 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Yang, X.G.; Ge, S.; Leng, Y.; Wang, C. Ultrafast charging of energy-dense lithium-ion batteries for urban air mobility. ETransportation 2021, 7, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningappa, N.G.; Vishweswariah, K.; Ahmed, S.; Mohamed, D.B.; Kumar, M.R.A.; Zaghib, K. Sustainable propulsion and advanced energy-storage systems for net-zero aviation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2025, 18, 9786–9838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresk, E.; Nikolakopoulos, G.; Gustafsson, T. A generalized reduced-complexity inertial navigation system for unmanned aerial vehicles. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2016, 25, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, T.F.K.; da Costa, J.P.L.C.; Liu, K.; João, P.L.C.C.; Liu, K.; Borges, G.A. Kalman-based attitude estimation for an UAV via an antenna array. In Proceedings of the 2014 8th International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication Systems (ICSPCS), Gold Coast, Australia, 15–17 December 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, J.; Fourati, H.; Li, R. Fast complementary filter for attitude estimation using low-cost MARG sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 16, 6997–7007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

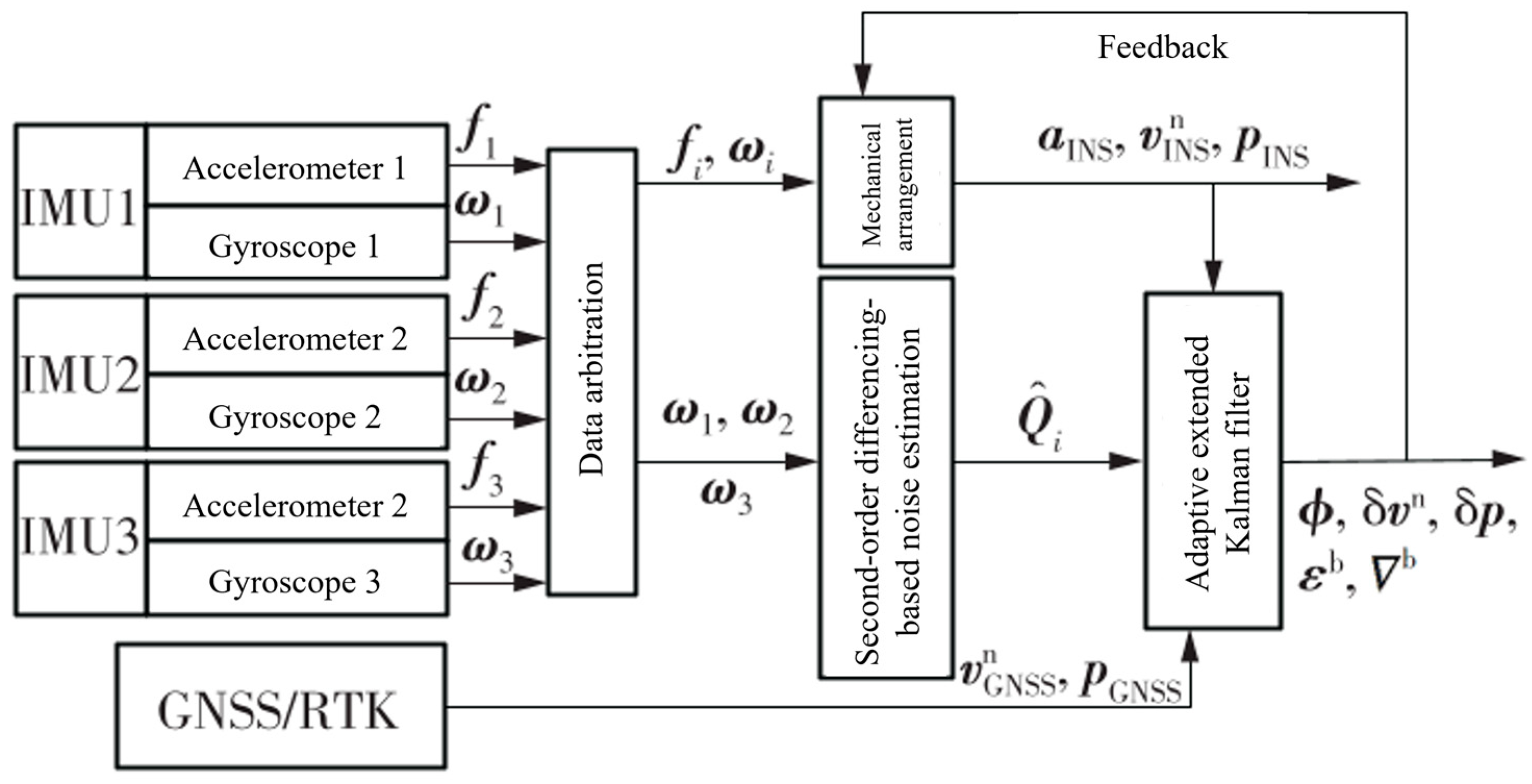

- Hu, Q.; Huang, S.; Chen, X.; Zhang, N.; Su, Q. Research on Redundant Strapdown Inertial Navigation Information Fusion of eVTOL drones Aircraft. J. South China Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2024, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Huang, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F. eVTOL drones performance analysis: A review from control perspectives. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 4877–4889. [Google Scholar]

- Ijaz, S.; Yan, L.; Hamayun, M.T.; Shi, C. Active fault tolerant control scheme for aircraft with dissimilar redundant actuation system subject to hydraulic failure. J. Franklin Inst. 2019, 356, 1302–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, W.; Lixin, W. Reconfigurable flight control design for combat flying wing with multiple control surfaces. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2012, 25, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, R.; Wei, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yan, Y. Architectural design space exploration of complex engineered systems with management constraints and preferences. J. Eng. Des. 2024, 35, 743–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z. Model free adaptive fault-tolerant tracking control for a class of discrete-time systems. Neurocomputing 2020, 412, 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy, S.; Sabatini, R.; Gardi, A.; Liu, J. LIDAR obstacle warning and avoidance system for unmanned aerial vehicle sense-and-avoid. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2016, 55, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasongko, R.A.; Rawikara, S.S.; Tampubolon, H.J. UAV obstacle avoidance algorithm based on ellipsoid geometry. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2017, 88, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tao, J.; Sun, G.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Y. A prognostic and health management framework for aero-engines based on a dynamic probability model and LSTM network. Aerospace 2022, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, K.; Sabatini, R.; Gardi, A.; Bijjahalli, S.; Kapoor, R.; Fahey, T.; Thangavel, K. Advances in Integrated System Health Management for mission-essential and safety-critical aerospace applications. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2022, 128, 100758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Avdelidis, N.P. Prognostic and health management of critical aircraft systems and components: An overview. Sensors 2023, 23, 8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monisha, M.; Blessed Prince, P. Predictive maintenance of aircraft components based on sensor data-driven approach: A review. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 11, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, F.; Qi, S. Preliminary analysis of airworthiness requirements standards for unmanned aerial vehicle systems. Flight Dyn. 2018, 36, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, S.; Liu, C. Interpretation and Reflection on NATO STANAG 4703 “Airworthiness Requirements for Light Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Systems”. Aviat. Stand. Qual. 2017, 4, 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H. Research on the regulatory system of unmanned aerial vehicles for the low-altitude economy industry: Based on the experience of the United States. China Circ. Econ. 2025, 39, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. Research on Safety Supervision and Risk Control Strategies in Low-altitude Economy. Civ. Aviat. Manag. 2024, 6, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, X.; Qu, W.; Xu, C.; He, H.; Wang, J. A review of research on low-altitude public air routes for urban air traffic and its new infrastructure. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2023, 44, 6–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, R. Research on Airspace Management and Safety Supervision in Low-altitude Economy. J. Chengdu Aviat. Vocat. Tech. Coll. 2024, 40, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, P.; Lu, Y. Research on the Design Method of Airspace Situation Monitoring System Based on ADS-B. China Equip. Eng. 2021, 22, 105–107. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z.; Deng, S.; Zheng, L.; Yang, Y.; Ji, J. Design and Implementation of Command and Operation Management Terminal Software Based on 1090ES ADS-B Aircraft. In Proceedings of the 9th China Command and Control Conference, Beijing, China, 5–7 July 2021; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Research on Aircraft Operation Safety Supervision Technology Based on ADS-B/5G. Master’s Thesis, Shenyang Aerospace University, Shenyang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xie, Z.; Liu, J. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Air Control Technology Based on Modern Communication Networks. Digit. Technol. Appl. 2022, 40, 16–18+35. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Ning, J.; Liu, H. Modeling and Simulation of the Space-Earth Link of Satellite-Based ADS-B System. J. Civ. Aviat. Univ. China 2024, 42, 37–42+63. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Integrated Network Design and Demand Forecast for On-Demand Urban Air Mobility. Engineering 2021, 7, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Yi, J.; Zhong, G. A review of research on urban low-altitude route planning. J. Nanjing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2021, 53, 827–838. [Google Scholar]

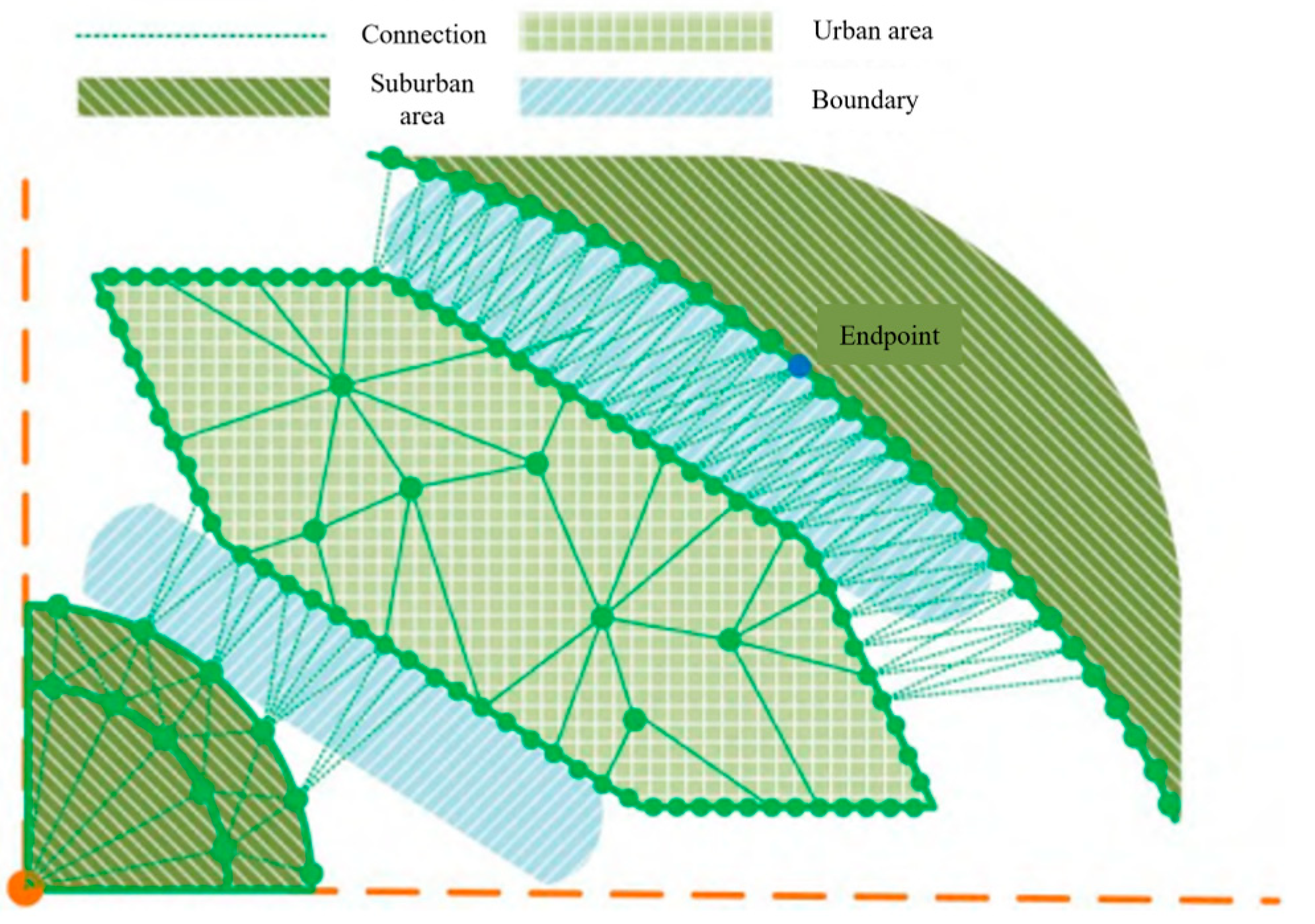

- Xu, C.; Ye, H.; Yue, H.; Tan, X.; Liao, X. Theoretical System and Technical Path for Iterative Construction of Low-altitude UAV Route Network in Urbanization Regions. J. Geogr. 2020, 75, 917–930. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Li, H.; Xia, L.; Zhou, H.; Liu, C. Design and Implementation of Xinjiang Civil Aviation Air Traffic Control System Based on Remote Sensing and GIS. Cent. Asia Inf. 2010, S1, 57–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Lv, D.; Qu, X. Urban Air Traffic: Reshaping the Future of Urban Transportation. Transp. Constr. Manag. 2023, 1, 56–59. [Google Scholar]

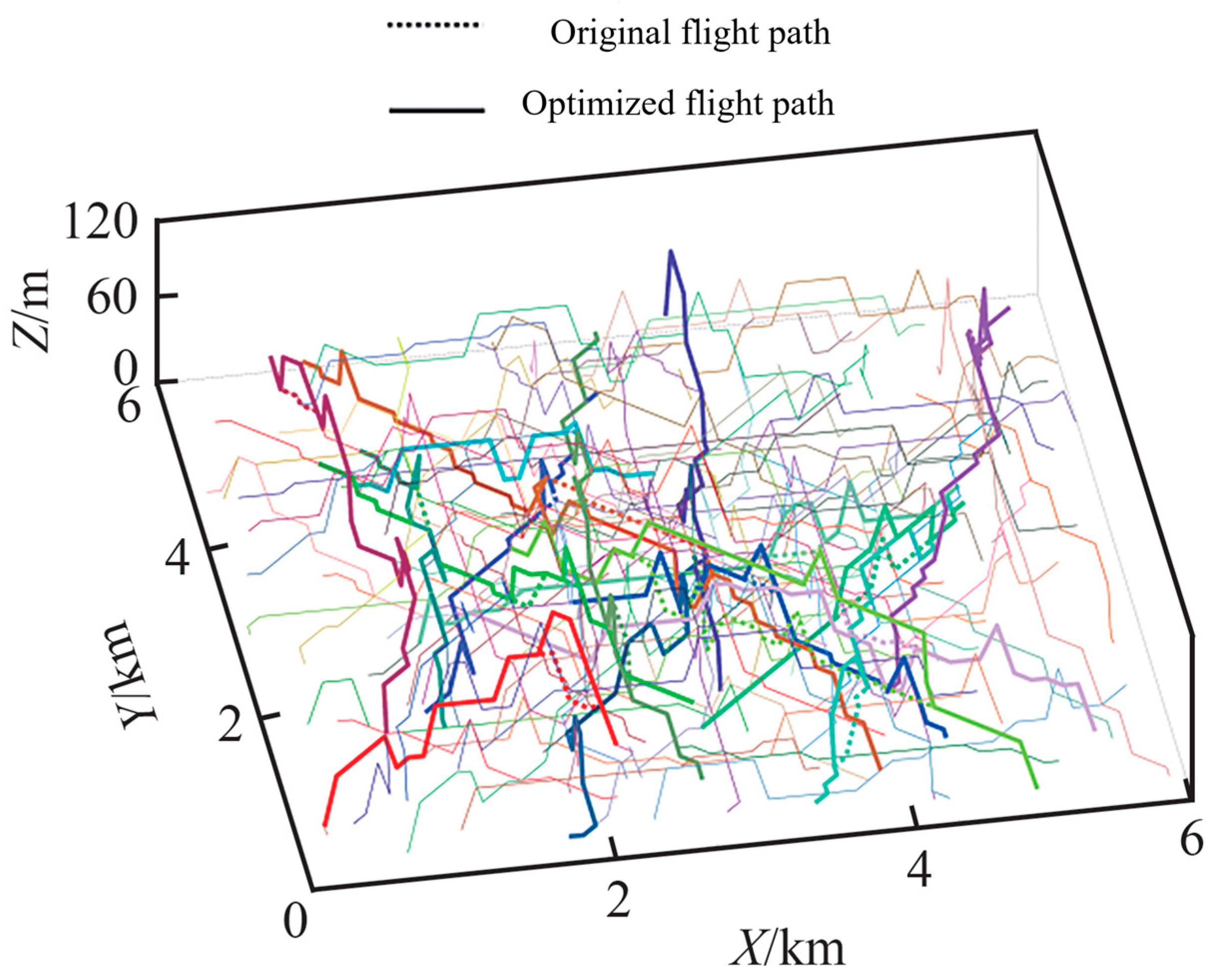

- Zhou, H.; Zhao, F.; Hu, X. Optimization of Vertical Takeoff and Landing Aircraft Paths in Urban Air Traffic Dynamic Airspace. J. Transp. Syst. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2024, 24, 295–308. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Xu, Y. Incorporating Optimization in Strategic Conflict Resolution for UAS Traffic Management. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 12393–12405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Wang, C.; Dou, S.; Li, Z. Application of JBPM in Emergency Dispatch Management of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing Network. Aerosp. Return Remote Sens. 2016, 37, 102–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, J. Assessment method for hazardous areas in the wake of urban air traffic drone swarms. Flight Dyn. 2024, 42, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Han, S.; Yin, J.; Ji, X.; Yang, Y. Collaborative deduction and optimization allocation method for urban low-altitude unmanned aerial vehicle flight plan. Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2024, 45, 269–291. [Google Scholar]

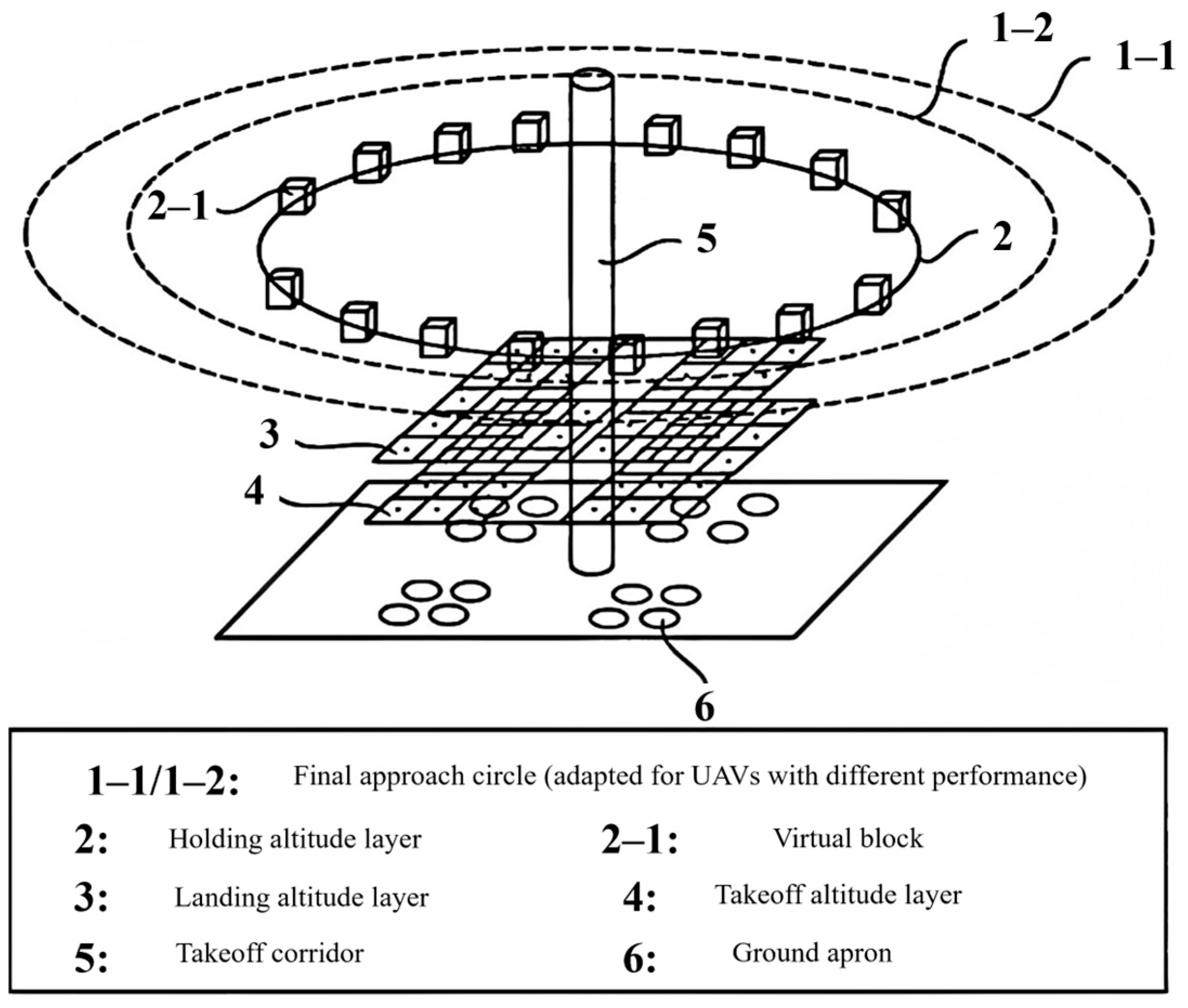

- Liu, D.; Jiang, B.; Zheng, Y.; Li, C. Urban air mobility Airspace Architecture and Trajectory Planning Method. Sci. Ind. 2023, 23, 268–273. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, G.; Hua, J.; Du, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B. Research on Optimization and Scheduling of Urban Low-altitude Flight Plans Based on Complex Networks. J. Aeronaut. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, J.; Goel, N. Fast-Forwarding to a Future of On-Demand Urban Air Transportation; Uber Elevate: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, T.; Wu, H.; Zame, S.I.; Antoniou, C. Data-driven vertiport siting: A comparative analysis of clustering methods for Urban Air Mobility. J. Urban Mobil. 2025, 7, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zeng, W.; Wei, W.; Wu, W.; Jiang, H. Vertiport Location Selection and Optimization for Urban Air Mobility in Complex Urban Scenes. Aerospace 2025, 12, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, K.; Qu, X. Urban air mobility (UAM) and ground transportation integration: A survey. Front. Eng. Manag. 2024, 11, 734–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadhil, D.N. A GIS-Based Analysis for Selecting Ground Infrastructure Locations for Urban Air Mobility. Master’s Thesis, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, 2018; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Rothfeld, R.L. Agent-Based Modelling and Simulation of Urban Air Mobility Operation. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, W. Research on Urban Air Traffic (UAM) Flow Demand Forecasting Based on Four Stage Method. Master’s Thesis, Civil Aviation Flight University of China, Guanghan, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency. Prototype Technical Specifications for the Design of VFR Vertiports for Operation with Manned VTOL-Capable Aircraft Certified in the Enhanced Category (PTS-VPT-DSN); EASA: Cologne, Germany, 2022; Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/downloads/136259/en (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration. Engineering Brief No. 105A, Vertiport Design, Supplemental Guidance to Advisory Circular 150/5390-2D, Heliport Design; FAA: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- ISO 5491:2023; Vertiports—Infrastructure and Equipment for Vertical Take-Off and Landing (VTOL) of Electrically Powered Cargo Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS). (International Organization for Standardization) ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Vascik, P.D.; Hansman, R.J. Development of Vertiport Capacity Envelopes and Analysis of Their Sensitivity to Topological and Operational Factors. In Proceedings of the AIAA Scitech 2019 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–11 January 2019; p. 0526. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, M.A.; Kramar, V.; Kaariaho, V.A.; Semkin, V.; Brilhante, D.; Alshaer, H.; Cleary, C.; Geraci, G. 5G Integrated Communications, Navigation, and Surveillance: A Vision and Future Research Perspectives. In Proceedings of the 2025 Integrated Communications, Navigation and Surveillance Conference (ICNS), Herndon, VA, USA, 21–23 April 2025; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, F.; Gollnick, V.; Schmitt, C. 5G-Enabled Architectural Imperatives and Guidance for Urban Air Mobility: Enhancing Communication, Navigation, and Surveillance. In Proceedings of the AIAA AVIATION FORUM and ASCEND 2024, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 12–16 August 2024; p. 3783. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, N.; Jamal, H.; Haque, J.; Magesacher, T.; Matolak, D.W. UAV command and control, navigation and surveillance: A review of potential 5G and satellite systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 2–9 March 2019; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Häckel, T.; Von Roenn, L.; Juchmann, N.; Fay, A.; Akkermans, R.; Tiedemann, T.; Schmidt, T.C. Coordinating cooperative perception in urban air mobility for enhanced environmental awareness. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.03290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Mo, W.; Hu, Y.; Tan, Y.; Chen, G.; An, K. Efficiently Optimizing Drone Nest Deployment for Transmission Line Inspection Based on Heuristic Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2023 China Automation Congress (CAC), Chongqing, China, 17–19 November 2023; pp. 9326–9331. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Lai, K.K.; Ram, B. Vehicle and UAV Collaborative Delivery Path Optimization Model. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Mohmoodian, V.; Charkhgard, H. Automated Flight Planning of High-Density Urban Air Mobility. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 131, 103324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Lee, S.; Abramson, M.; Phillips, J.D. Analysis of Conflicts among Urban Air Mobility Aircraft and with Traditional Aircraft. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/AIAA 41st Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), Portsmouth, VA, USA, 18–22 September 2022; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli, M.; Ditta, C.C.; Postorino, M.N. New Infrastructures for Urban Air Mobility Systems: A Systematic Review on Vertiport Location and Capacity. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2023, 112, 102460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascara, B.; Spencer, T.; DeGarmo, M.; Maroney, D.; Niles, R.; Vempati, L. Urban Air Mobility Airspace Integration Concepts; The MITRE Corporation: McLean, VA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.mitre.org/sites/default/files/publications/pr-19-00667-9-urban-air-mobility-airspace-integration.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Federal Aviation Administration. Airspace Classification—ASPMHelp. Available online: https://aspm.faa.gov/aspmhelp/index/Airspace_Classification.html (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Dai, W.; Pang, B.; Low, K.H. Conflict-Free Four-Dimensional Path Planning for Urban Air Mobility Considering Airspace Occupancy. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2021, 119, 107154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosson, C.; Lauderdale, T.A. Simulation Evaluations of an Autonomous Urban Air Mobility Network Management and Separation Service. In Proceedings of the 2018 Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 25–29 June 2018; p. 3365. [Google Scholar]

- Rothfeld, R.; Balac, M.; Ploetner, K.O.; Antoniou, C. Agent-Based Simulation of Urban Air Mobility. In Proceedings of the 2018 Modeling and Simulation Technologies Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 25–29 June 2018; p. 3891. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.N. Infrastructure and modernity: Force, time, and social organization in the history of sociotechnical systems. In Modernity and Technology; Misa, T.J., Brey, P., Feenberg, A., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 185–225. [Google Scholar]

- Shenfu Office. Implementation Plan for Innovative Development of Low-Altitude Economy Industry (2022–2025); Shenfu Office Document No. 130; Shenfu Office: Shenyang, China, 2022.

- Shenzhen Stock Exchange. Several Measures to Support High Quality Development of Low-Altitude Economy in Shenzhen; Shenzhen Stock Exchange Regulation No. 12; Shenzhen Stock Exchange: Shenzhen, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Standing Committee of the Shenzhen Municipal People’s Congress. Regulations on the Promotion of Low-Altitude Economic Industries in Shenzhen Special Economic Zone; Standing Committee of the Shenzhen Municipal People’s Congress: Shenzhen, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Civil Aviation Administration of China. Reply on Supporting Shenzhen to Create a National Low-Altitude Economic Industry Comprehensive Demonstration Zone; CAAC: Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shenzhen Development and Reform Commission. High-Quality Construction Plan for Low-Altitude Takeoff and Landing Facilities in Shenzhen (2024–2025); SZDRC: Shenzhen, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shenzhen Development and Reform Commission. Shenzhen Low-Altitude Infrastructure High Quality Construction Plan (2024–2026); SZDRC: Shenzhen, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shenzhen Market Supervision Administration; Shenzhen Transportation Bureau. Guidelines for the Construction of Low-Altitude Economic Standard System in Shenzhen (v1.0); Shenzhen Market Supervision Administration: Shenzhen, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- The People’s Government of Longhua District, Shenzhen. Measures to Promote High Quality Development of Low-Altitude Economy Industry in Longhua District; Shenlong Huafu Ban Gui [2023] No. 6; Longhua District Government: Shenzhen, China, 2023.

- The People’s Government of Longhua District, Shenzhen. Construction Plan for Longhua District Low-Altitude Economic Experimental Zone in 2024; Shenlong Huafu Letter [2024] No. 3; Longhua District Government: Shenzhen, China, 2024.

- The People’s Government of Dapeng New Area, Shenzhen. Several Measures to Promote High Quality Development of Low-Altitude Economy Industry in Dapeng New Area, Shenzhen; Shen Peng Ban Gui [2025] No. 1; Dapeng New Area Government: Shenzhen, China, 2025.

- The People’s Government of Longgang District, Shenzhen. Measures for Promoting the Development of Low-Altitude Economy Industry in Longgang District; Shenlong Gongxin Gui [2023] No. 14; Longgang District Government: Shenzhen, China, 2023.

- The People’s Government of Longgang District, Shenzhen. Implementation Rules for Supporting the Development of Low-Altitude Economic Industries with Special Funds for Industrial and Information Industry Development in Longgang District; Shenlong Gongxin Gui [2024] No. 4; Longgang District Government: Shenzhen, China, 2024.

- The People’s Government of Futian District, Shenzhen. Several Measures to Support High Quality Development of Low-Altitude Economy in Futian District, Shenzhen (Trial); Shenzhen Stock Exchange Futian Regulation [2024] No. 1; Futian District Government: Shenzhen, China, 2024.

- The People’s Government of Nanshan District, Shenzhen. Special Support Measures for Promoting Low-Altitude Economic Development in Nanshan District; Nanshan District Government: Shenzhen, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Boston Consulting Group (BCG). White Paper on China’s Manned eVTOL drones Industry 2025; BCG: Boston, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Airworthiness requirements | Airworthiness standards |

| Onboard equipment requirements | |

| Maintenance and support requirements | |

| Infrastructure requirements of regulatory system | Ground surveillance facilities |

| Air Mobility management automation system | |

| Flight service system | |

| Data communication network | |

| Information platform |

| Transport Mode | Commercial Aviation | Urban Air Mobility (UAM) |

|---|---|---|

| Communication Services | VHF ground transmitters provide VHF air-to-ground voice communication; ACARS VHF air-to-ground data link | 5G communication network provided by ground base stations (digital signals); onboard Ad Hoc network |

| Navigation Services | VOR/DME/NDB navigation stations provide radio navigation; ILS provides landing guidance; GNSS/IMU provides integrated navigation | GNSS/IMU integrated navigation; high-resolution 3D elevation maps of urban airspace; positioning and path planning services based on communication base stations; online visual recognition-assisted positioning |

| Surveillance Services | Primary radar, secondary radar surveillance; ADS-B | Centralized cooperative surveillance via ground 5G communication link; air-to-air surveillance via onboard Ad Hoc network |

| Control Services | Radar control commanded by air mobility controllers; procedural control (airways, approaches, airport areas, etc.) | Autonomous flight or coordinated scheduling underground control center instructions; human operators responsible for monitoring and emergency handling |

| Flight Information Services | ATS automatic information broadcasting; information includes local airport and en-route meteorological conditions | Full airspace traffic information; VTOL airport parking slot status; detailed urban airspace meteorological information; wake turbulence information along flight routes |

| Alert Services | When aircraft are in emergency, the control unit issues airspace alerts; alerts based on secondary transponder codes | Full-airspace alerts via 5G network; onboard devices actively broadcast when autonomous aircraft encounter malfunctions |

| Item | Parameter |

|---|---|

| Dimensions (closed) | 1020 mm × 1020 mm × 1345 mm |

| Dimensions (deployed) | 1836 mm × 1020 mm × 1246 mm |

| Effective landing platform size | 760 mm × 760 mm |

| Product weight | ≤560 kg |

| Standby operating power | ≤500 W |

| Peak operating power | ≤3000 W |

| Power supply requirements | AC 220 V, 16 A |

| Maximum effective signal range | 6 km (SRRC/unobstructed) |

| Battery swap time | <120 s |

| UPS endurance | 4 h (without battery charging) |

| Operating temperature | −5 to 45 °C |

| Operating humidity | ≤85% RH (non-condensing) |

| Policy Type | Release Date | Policy Title | Core Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| City-Level Comprehensive Policies | End of 2022 | Implementation Plan for Innovative Development of Low-Altitude Economy Industry (2022–2025) [112] | Defines overall development direction and objectives of low-altitude economy for 2022–2025 |

| 8 December 2023 | Several Measures to Support High-Quality Development of Low-Altitude Economy in Shenzhen [113] | Provides multidimensional policy support to promote high-quality development of the low-altitude economy | |

| Early 2024 | Regulations on the Promotion of Low-Altitude Economic Industries in Shenzhen Special Economic Zone [114] | Standardizes low-altitude economic activities in regulatory form, covering flight services, safety management, and other core areas | |

| Regulatory Policies | March 2024 | Reply of the Civil Aviation Administration of China on Supporting Shenzhen to Create a National Low-Altitude Economic Industry Comprehensive Demonstration Zone [115] | Grants Shenzhen pilot status for regulatory innovation in low-altitude economy and promotes breakthroughs in regulatory mechanisms |

| Infrastructure-Specific Policies | 2 August 2024 | High-Quality Construction Plan for Low-Altitude Takeoff and Landing Facilities in Shenzhen (2024–2025) [116] | Focuses on construction of takeoff and landing facilities, specifying quantitative targets and implementation paths |

| 31 July 2025 | Shenzhen Low-Altitude Infrastructure High-Quality Construction Plan (2024–2026) [117] | Accelerates deployment of low-altitude takeoff/landing, information, and innovation infrastructure; establishes global low-altitude economy HQ R&D center, high-end manufacturing center, full-scenario demonstration and verification center, and one-stop solution supply center; aims to build Shenzhen as the “World’s No.1 Low-Altitude Economy City” | |

| Standards and Norms Policies | 25 December 2024 | Guidelines for the Construction of Low-Altitude Economic Standard System in Shenzhen (v1.0) [118] | Introduces the “Four Networks”—Facility Network, Airspace Network, Air Route Network, Service Network; builds eight primary subsystems and unifies the low-altitude economic standard framework |

| District-Level Comprehensive Policies | March 2024 | Measures to Promote High-Quality Development of Low-Altitude Economy Industry in Longhua District [119] | Details regional low-altitude economy construction tasks and specifies project investment and implementation plans |

| 15 October 2023 | Construction Plan for Longhua District Low-Altitude Economic Experimental Zone in 2024 [120] | Provides specific support for regional enterprises, including settlement incentives and technology development | |

| 20 Mar 2025 | Several Measures to Promote High-Quality Development of Low-Altitude Economy Industry in Dapeng New District, Shenzhen [121] | Enhances industrial support environment, expands low-altitude flight applications, cultivates enterprises along the low-altitude economy chain, and encourages technological innovation | |

| 9 May 2024 | Measures for Promoting the Development of Low-Altitude Economy Industry in Longgang District [122] | Quantifies subsidies and incentives, mainly using an approval-based review process, and strengthens fund supervision | |

| 22 December 2023 | Implementation Rules for Supporting the Development of Low-Altitude Economic Industries with Special Funds for Industrial and Information Industry Development in Longgang District, Shenzhen [123] | Supports establishment of advanced low-altitude technology platforms, promotes settlement of complete aircraft development projects, supports manned low-altitude air routes, and UAV comprehensive test base operations | |

| 1 November 2024 | Several Measures to Support High-Quality Development of Low-Altitude Economy in Futian District, Shenzhen (Trial) [124] | Supports infrastructure construction (e.g., takeoff/landing sites, charging/swapping stations), expands application scenarios (e.g., logistics, manned transport), promotes industrial agglomeration (e.g., specialized building support), and provides detailed certification and operation subsidy standards | |

| 8 April 2024 | Special Support Measures for Promoting Low-Altitude Economic Development in Nanshan District [125] | Focuses on attracting large enterprises and cultivating new industries such as Urban Air Mobility (UAM); provides substantial financial support, with maximum rewards up to 100 million RMB |

| Influence Dimension | Mechanisms and Content |

|---|---|

| Contribution to Technology Reserve | Policies encourage core technology R&D, guiding enterprises to focus on key areas such as flight control, gimbal systems, and video transmission, forming reusable technological outcomes. Leading companies such as DJI have accumulated flight control stability and long-range video transmission technologies that can be directly applied to UAM aircraft’s autonomous driving systems and real-time monitoring modules, addressing critical technical challenges in flight safety and precise control, thus laying the foundation for UAM technology deployment. |

| Talent Training and Supply | Policies, through industrial support, encourage enterprises to expand R&D and production scale, indirectly promoting professional talent development. Under favorable policy conditions, leading enterprises establish full-chain talent cultivation systems covering R&D, production, testing, and operations. The resulting talent pool, equipped with expertise in aircraft design and airspace management, can quickly adapt to UAM technology development and industry operations, injecting innovative capabilities into UAM enterprises. |

| Industrial Agglomeration Effect | Policies guide upstream and downstream enterprise clustering by planning industrial parks and providing supporting services. Under policy support, leading companies such as DJI form industry cores that attract component suppliers (e.g., battery and sensor manufacturers), software developers (e.g., flight control system providers), and application service providers (e.g., low-altitude logistics operators), establishing a complete “R&D–production–application” industrial chain, This policy-induced clustering has materialized into a robust industrial chain ecosystem, which now encompasses over 1500 specialized enterprises in Shenzhen. The density and maturity of this ecosystem are further evidenced by an occupancy rate exceeding 95% in dedicated low-altitude industrial parks and the completion of tens of thousands of hours of UAS flight tests in the region. This vibrant agglomeration reduces collaboration costs and technical challenges for UAM enterprises, creating a self-reinforcing innovation cluster. |

| Demonstration and Leading Effect | Policies enhance the demonstration effect of leading enterprises by recognizing outstanding companies and promoting successful cases. DJI’s commercial model in the UAV sector (e.g., “technology R&D + scenario expansion + global marketing”) and its technological innovation path (e.g., iterative upgrading of core components) provide a replicable development paradigm for UAM companies, helping them avoid trial-and-error risks in technology selection and market promotion, thereby shortening commercialization timelines. |

| Manufacturer | Policy Guidance Background | Technological/Product Iteration Achievements |

|---|---|---|

| DJI, Shenzhen, China | Required to comply with national aviation regulatory policies (e.g., European UAV regulations limiting flight zones, changes in U.S. airspace usage rules); policies require enterprises to optimize product compliance based on “geospatial UAV data from national aviation authorities.” | Technical Level: Removed GEO system flight area restrictions to increase flight freedom within regulatory compliance, addressing users’ core pain point of “restricted flight zones.” Product Level: Launched “DJI Flip All-in-One Vlog UAV” to fill entry-level consumer drone market gaps, and released “O4 Video Transmission and Camera Modules” (advanced high-speed FPV modules), completing a full consumer drone product matrix from entry-level to flagship, enabling comprehensive scenario coverage. |

| Puzhou Aircraft Technology, Puzhou, China | Domestic policies position the low-altitude economy as a key form of new productive capacity, encouraging low-altitude applications (e.g., logistics, inspection) and technological innovation, with requirements for safe and efficient operations. | Product System: Released lightweight quadrotor S200 series, K02 small automatic battery-swapping hangar, and K03 lightweight automatic charging hangar, forming an integrated “UAV + hangar” operational solution. Core Technology: S200 series supports edge computing during flight and dual-edge computation; ensures operation continuity in no-signal areas via satellite short-message communication; uses national cryptography-level encryption for data security; upgraded imaging and gimbal configurations for multi-scenario operations. Hangar Functionality: K02 and K03 enable rapid jump-flight operations for high-frequency, high-safety missions, meeting policy-driven low-altitude efficient application scenarios. |

| Datuo Intelligent Aviation, Shenzhen, China | Policies promote technological innovation in aviation, encouraging enterprises to overcome communication technology bottlenecks to meet high-efficiency, long-range communication needs of low-altitude aircraft. | Technical Breakthrough: Obtained patent for “a type of antenna” capable of stable operation across a broader frequency range, enhancing signal stability and reliability, addressing UAV operation and aviation monitoring communication gaps. R&D Approach: Applied Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) models in antenna design, optimizing product performance via AI, reflecting the policy-driven path of “technology innovation driving industrial upgrading.” |

| EHang, Shenzhen, China | Global low-altitude economy policies facilitate eVTOL drone commercialization; domestic policies provide airworthiness certification and industrial support funds, encouraging enterprises to overcome eVTOL drone technology bottlenecks and start commercialization. | Product Certification: The EH216-S eVTOL drones obtained Type Certificate (TC), Airworthiness Certificate (AC), and Production Certificate (PC) in April 2024, becoming the world’s first eVTOL drones to complete all three certifications, confirming its technology meets commercial safety standards. Product Advantages: Compact, unmanned, integrated air-ground operations with cost-effectiveness, suitable for urban low-altitude mobility; orders and market demand continue to grow. Technology Iteration: From EHang 105 to EH216-S, achieved significant improvements in autonomous flight, safety, and reliability, guiding industry eVTOL drones R&D focus toward “safety and commercialization.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, J.; Guan, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Gan, W. A Systematic Review of Urban Air Mobility Development: eVTOL Drones’ Technological Challenges and Low-Altitude Policies of Shenzhen. Drones 2025, 9, 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120842

Xu J, Guan C, Wang Y, Zhuang J, Gan W. A Systematic Review of Urban Air Mobility Development: eVTOL Drones’ Technological Challenges and Low-Altitude Policies of Shenzhen. Drones. 2025; 9(12):842. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120842

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Jinhong, Chenxi Guan, Yunpeng Wang, Junjie Zhuang, and Wenbiao Gan. 2025. "A Systematic Review of Urban Air Mobility Development: eVTOL Drones’ Technological Challenges and Low-Altitude Policies of Shenzhen" Drones 9, no. 12: 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120842

APA StyleXu, J., Guan, C., Wang, Y., Zhuang, J., & Gan, W. (2025). A Systematic Review of Urban Air Mobility Development: eVTOL Drones’ Technological Challenges and Low-Altitude Policies of Shenzhen. Drones, 9(12), 842. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120842