Human Machine Autonomy in Medical and Humanitarian Logistics in Remote and Infrastructure-Poor Settings

Highlights

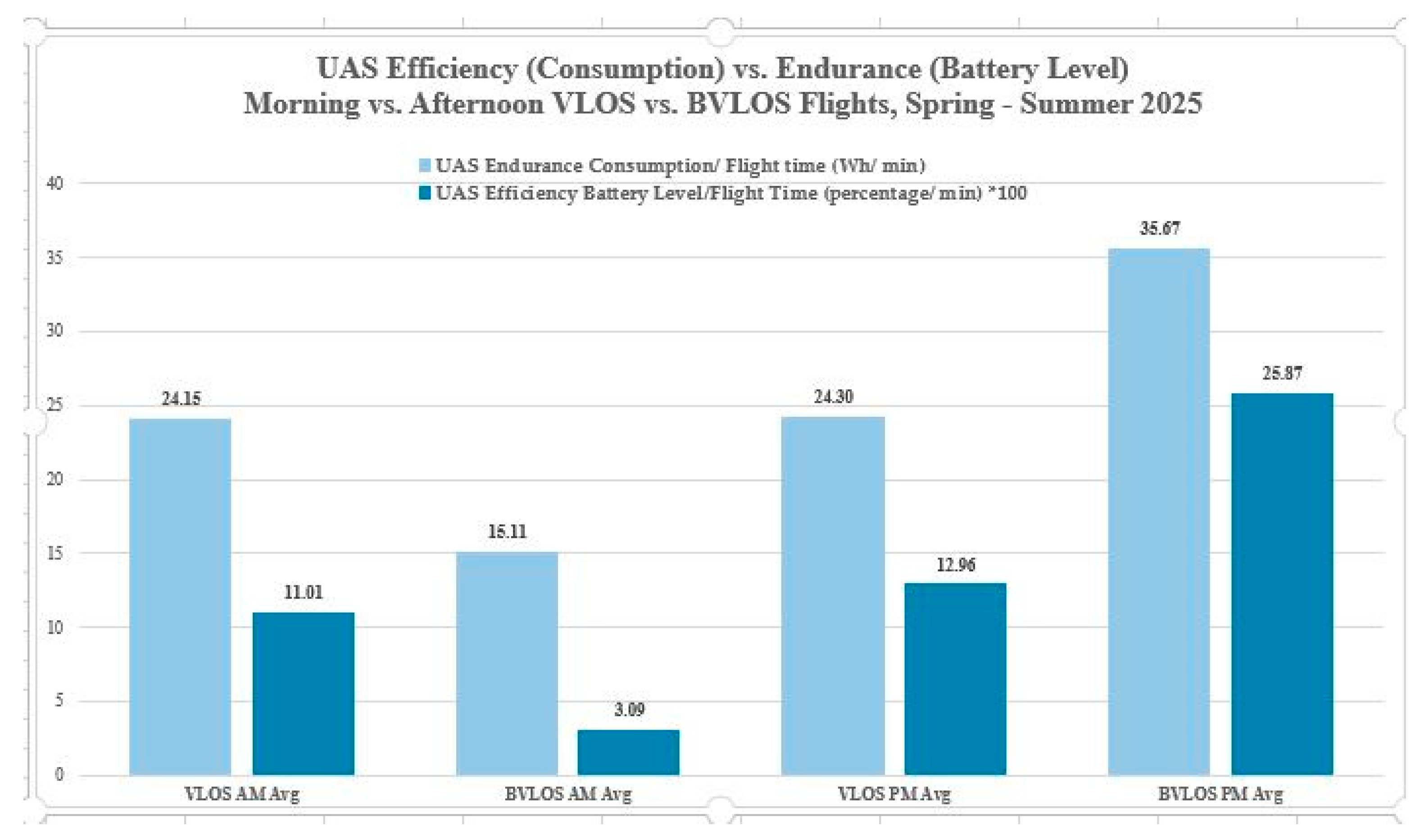

- Using initial empirical data from an on-going study in a resource-constrained environment, the limited data analysis suggested links between increased levels of uncrewed aerial systems’ autonomy and system performance, with higher endurance, lower speeds, and lower consumption per flight time and less waypoint deviation observed, although system efficiency was decreased with greater autonomy.

- Few operator performance differences in following system tracks or track-keeping, and in perceiving and comprehending unfolding situations, or situation awareness, were observed with increasing autonomy, perhaps due to the small subject pool and the homogeneity of the operator’s subject pool.

- This work proposes a framework for examining the impact of various levels of autonomy in human–autonomy teams operating in remote humanitarian logistics delivery systems.

- It highlights the importance of considering human and technological performance and perceptions together in human–autonomy teams, particularly in infrastructure-poor settings.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. UAS Autonomy

1.3. Impacts of Autonomy Levels

1.3.1. System Performance

1.3.2. Operator Performance

1.3.3. Situation Awareness

1.3.4. Moderating Variables

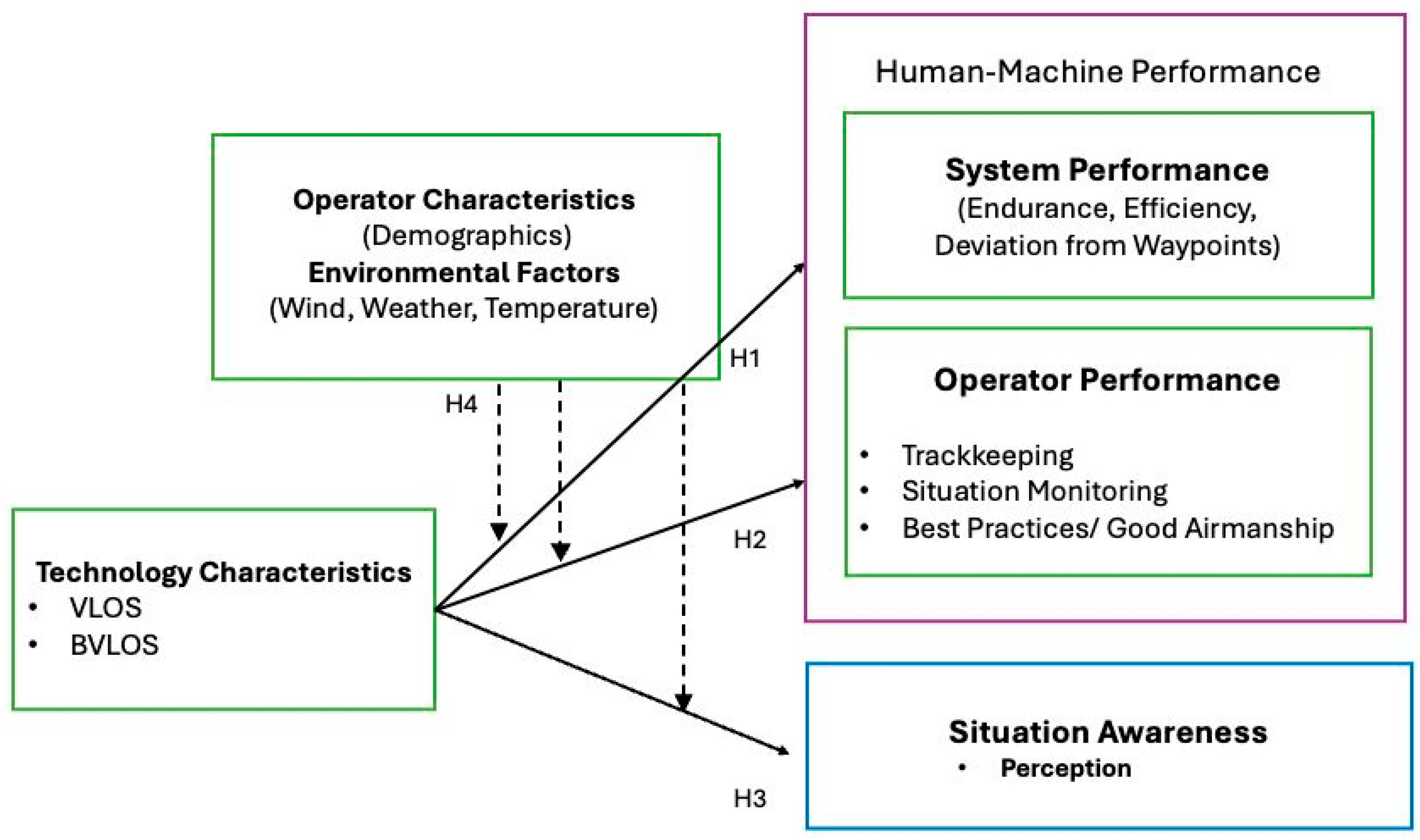

1.4. Research Model

1.5. Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Operational Setting: Medical and Humanitarian Logistics

2.2. Evaluation

2.2.1. Methods

2.2.2. Data

2.2.3. Procedure

2.2.4. Materials

2.3. Analysis

2.4. Informed Consent

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADAC ARCTIC | Arctic Domain Awareness Center—Addressing Rapid Changes Through Technology Innovation and Collaboration |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AM | Morning |

| BVLOS | Beyond Visual Line of Sight |

| DHS | U.S. Department of Homeland Security |

| FAA | U.S. Federal Aviation Administration |

| FMS | Flight Management System |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| GOM | U.S. Federal Aviation Administration’s General Operations Manual |

| HAT | Human–Autonomy Teams |

| HMT | Human Machine Teaming |

| ICAO | International Civil Aviation Organization |

| NASA | U.S. National Aviation and Space Administration |

| NNW | North–Northwest |

| NW | Northwest |

| PM | Afternoon |

| RPI | Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute |

| SA | Situation Awareness |

| SAGAT | Situation Awareness Global Assessment Technique |

| SART | Situation Awareness Rating Technique |

| SUNY | State University of New York |

| TLX | Task Load Index |

| UAA | University of Alaska Anchorage |

| UAS | Uncrewed Aerial System |

| USCG | U.S. Coast Guard |

| VLOS | Visual Line of Sight |

| VTOL | Vertical Take Off and Landing |

| W | West |

| WNW | West–Northwest |

| WSW | West–Southwest |

References

- Kannally, C.T.; Smith, J.R.; IJtsma, M. Human-AI teaming in the automotive and mobility industry: Guiding design to support joint activity. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 23–27 October 2023; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2023; Volume 67, pp. 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokadli, G.; Dorneich, M.C.; Matessa, M. Evaluation of playbook delegation approach in human-autonomy teaming for single pilot operations. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrak, A.E.; Gorsich, D.; Epureanu, B.I. Future of Autonomous High-Mobility Military Systems. SAE Int. J. Connect. Autom. Veh. 2020, 3, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Evans, H.; Porter, Z.; Graham, S.; McDermid, J.; Lawton, T.; Snead, D.; Habli, I. The Case for delegated AI Autonomy for Human AI teaming in Healthcare. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.18778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeese, N.; Demir, M.; Chiou, E.; Cooke, N.; Yanikian, G. Understanding the role of trust in human-autonomy teaming. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICCS), Maui, HI, USA, 8–11 January 2019; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10125/59466 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- O’Neill, T.; McNeese, N.; Barron, A.; Schelble, B. Human–autonomy teaming: A review and analysis of the empirical literature. Hum. Factors 2022, 64, 904–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norlander, A. Autonomy in Conflict: Technology, Complexity, Ethics, and Policy Implications. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 90489–90498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Gao, Z. Applying HCAI in developing effective human-AI teaming: A perspective from human-AI joint cognitive systems. Interactions 2024, 31, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebru, B.; Zeleke, L.; Blankson, D.; Nabil, M.; Nateghi, S.; Homaifar, A.; Tunstel, E. A review on human–machine trust evaluation: Human-centric and machine-centric perspectives. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 2022, 52, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Visser, E.J.; Pak, R.; Shaw, T.H. From ‘automation’ to ‘autonomy’: The importance of trust repair in human–machine interaction. Ergonomics 2018, 61, 1409–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawless, W.F.; Mittu, R.; Sofge, D.; Hiatt, L. Artificial intelligence, autonomy, and human-machine teams—Interdependence, context, and explainable AI. AI Mag. 2019, 40, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieba, S.; Polet, P.; Vanderhaegen, F.; Debernard, S. Principles of adjustable autonomy: A framework for resilient human–machine cooperation. Cogn. Technol. Work 2010, 12, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.; Duplessis, B.T.; Stoll, H.; Kelly, T.K.; Parker, T. Small Uncrewed Aircraft Systems (SUAS) in Divisional Brigades; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA2600/RRA2642-5/RAND_RRA2642-5.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Sauser, M.K. Unmanned Aircraft and the Revolution in Operational Warfare. Military Review. July–August 2025; pp. 54–64. Available online: https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/JA-25/Unmanned-Aircraft-Revolution/Unmanned-Aircraft-Revolution-ua.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Ray, H.M.; Laouar, Z.; Sunberg, Z.; Ahmed, N. Human-centered autonomy for UAS target search. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Yokohama, Japan, 13–17 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 9563–9570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Gupta, P.; Balaji, S.; Sharma, S.; Ghosh, A.K.; Simmy; Panda, S. Assessing the feasibility of drone-mediated vaccine delivery: An exploratory study. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, B. Human Factors Requirements for Human-AI teaming in Aviation. Future Transp. 2025, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, C.A.; Ruszkowski, L.K.M.; Borade, A.R.; Goodyear, M.T. BVLOS UAS Cargo Delivery Simulation–A DoD-Sponsored Operational Evaluation with NASA and Project ULTRA; NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS): Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20250002630 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Sajjadi, S.; Mehta, V.; Janabi-Sharif, F.; Mantegh, I. Cellular Connectivity Risk-Aware Flight Path Planning for BVLOS UAV Operations. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Charlotte, NC, USA, 14–17 May 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.C. Risk assessment for UAS logistic delivery under UAS traffic management environment. Aerospace 2020, 7, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Manen, B.R.; Ter Maat, G.; Boe, M.; Mersha, A.Y. The BEAST: Modular Open-Source Framework for BVLOS Drone Flights with Long-Term Autonomy. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Charlotte, NC, USA, 14–17 May 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wynsberghe, A.; Comes, T. Drones in humanitarian contexts, robot ethics, and the human–robot interaction. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2020, 22, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Duan, H. Hierarchical pigeon inspired optimization based Multi-UAV obstacle avoidance control. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 159, 109963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Gu, J.; Mou, J. UAV autonomous obstacle avoidance via causal reinforcement learning. Displays 2025, 87, 102966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleland-Huang, J.; Chambers, T.; Zudaire, S.; Chowdhury, M.T.; Agrawal, A.; Vierhauser, M. Human–machine teaming with small unmanned aerial systems in a mape-k environment. ACM Trans. Auton. Adapt. Syst. 2024, 19, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, K.; Kulić, D.; Chung, H. From Novice to Skilled: RL-Based Shared Autonomy Communicating with Pilots in UAV Multi-Task Missions. ACM Trans. Hum. Robot Interact. 2025, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieber, C.; Vieira da Silva, L.M.; Grünhagen, K.; Fay, A. Rule-based verification of autonomous unmanned aerial vehicles. Drones 2024, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Lin, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, X.; Huang, J.; Dai, X.; Wang, Y.; Tian, C.; et al. UAVs meet LLMs: Overviews and perspectives towards agentic low-altitude mobility. Inf. Fusion 2025, 122, 103158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, L.K.; Gram, J.K.B.; Grabmayr, A.J.; Højen, A.; Hansen, C.M.; Rostgaard-Knudsen, M.; Claesson, A.; Folke, F. Semi-autonomous drone delivering automated external defibrillators for real out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A Danish feasibility study. Resuscitation 2025, 208, 110544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Faridi, S.G.; Alghamdi, A.S.; Alosiml, F.K.; Alshammari, Z.K.T.; Alshammari, H.M.H.; Alsahmah, S.M.F.; Alotaibli, F.; Al-Faridi, S.G.; Aloufi, O.; Saqer, T.S.M.; et al. Drone-Assisted AED Delivery in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Systematic Review of Response Time, Feasibility, and Cost-Effectiveness. Integr. Biomed. Res. 2024, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jairoun, A.A.; Al-Hemyari, S.S.; Shahwan, M.; Al-Ghananeem, A.M.; El-Dahiyat, F.; Al-Salmi, S.; Babar, Z.U.D. The evolution of medication delivery via drones: Revolutionizing healthcare logistics. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2025, 18, 2519137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, M.; Mukkamala, R.; Olariu, S. Delivery of Medical Supplies to Remote Locations via Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: Approaches, Challenges, and Solutions. Transp. Res. Procedia 2025, 84, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Khan, A. Emergency Medical Supply Automatic Drone Evaluation: A Complete Review. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Res. Technol. 2025, 17, 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, G.; Manimaran, P.; Mishra, A.; Sapra, A. Unmanned aerial vehicles: An inevitable armamentarium in Armed Forces Medical Services. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, O.; Snowdon, K.; Lomzynska, S.; Ferraresi, D.; Norton, M.; Austin, D.; Gale C Wilkinson, C.; McClelland, G. The impact of drone delivery of an automated external defibrillator: A simulation feasibility study. Br. Paramed. J. 2025, 10, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enayati, S.; Bahmani, P. Collaborative Last-Mile Delivery with Drones in Rural America; No. 25-1121-3002-104; University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Mid-America Transportation Center: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2025. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Patel, R.R.; Parmar, P.J.; Sutariya, M.J. MedDrone Rescue: A Survey on Drones for Medical Supplies in Rural, Terrained Areas and Search & Rescue Operations. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Machine Learning and Autonomous Systems (ICMLAS), Prawet, Thailand, 10–12 March 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1682–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejeune, M.A.; Margot, F. Response Time Minimization for Cardiac Arrests. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2025, 34, 2618–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aretoulaki, E.; Ponis, S.T.; Plakas, G. Requirements Engineering for a Drone-Enabled Integrated Humanitarian Logistics Platform. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintanilla García, I.; Vera Velez, N.; Alcaraz Martínez, P.; Vidal Ull, J.; Fernandez Gallo, B. A quickly deployed and UAS-based logistics network for delivery of critical medical goods during healthcare system stress periods: A real use case in Valencia (Spain). Drones 2021, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, S.; Ivaki, N.; Barata, J. A Systematic Literature Review of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Healthcare and Emergency Services. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.08834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Wang, C.J.; Low, K.H. Framework of level-of-autonomy-based concept of operations: UAS capabilities. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/AIAA 40th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), San Antonio, TX, USA, 3–7 October 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/9594469/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Huang, H.M.; Pavek, K.; Ragon, M.; Jones, J.; Messina, E.; Albus, J. Characterizing Unmanned System Autonomy: Contextual Autonomous Capability and Level of Autonomy Analyses. In Unmanned Systems Technology IX; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2007; Volume 6561, pp. 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, R.; Roumeliotis, K.I.; Karkee, M. AI agents vs. Agentic AI: A conceptual taxonomy, applications and challenges. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.10468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrink, M.H.; Gregory, J.W. Design and development of a high-speed UAS for beyond visual line-of-sight operations. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2021, 101, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, P.J.; Gray, M.W. Levels of Autonomy and Autonomous System Performance Assessment for Intelligent Unmanned Systems; ERDC/GSLSR-14-1; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Research & Development Center (ERDC): Vicksburg, MI, USA, 2014; Available online: https://erdc-library.erdc.dren.mil/server/api/core/bitstreams/81b728f8-7609-4ef8-e053-411ac80adeb3/content (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Osborne, M.; Lantair, J.; Shafiq, Z.; Zhao, X.; Robu, V.; Flynn, D.; Perry, J. UAS operators’ safety and reliability survey: Emerging technologies towards the certification of autonomous UAS. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International IEEE Conference on System Reliability and Safety (ICSRS), Rome, Italy, 20–22 November 2019; pp. 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Pang, B.; Dai, F.; Low, K.H. Risk Assessment Model for UAV Cost-Effective Path Planning in Urban Environments. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 150162–150173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Tan, Q.; Ra, T.; Low, K.H. A Risk-based UAS Traffic Network Model for Adaptive Urban Airspace Management. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation 2020 Forum, Virtual, 15–19 June 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.H.J.; Tan, S.K.; Low, K.H. Three-dimensional (3D) Monte-Carlo modeling for UAS collision risk management in restricted airport airspace. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 105964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Su, X.; Gao, B. Dynamics modeling and Trajectory Optimization for unmanned aerial-aquatic vehicle diving into the water. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 89, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, L.; Wang, J. Multi-Strategy Improved Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Path Planning of UAV in 3-D Low Altitude Urban Environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 40470–40483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejias, L.; Diguet, J.P.; Dezan, C.; Campbell, D.; Kok, J.; Coppin, G. Embedded computation architectures for autonomy in unmanned aircraft systems (UAS). Sensors 2021, 21, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhuheir, M.; Erbad, A.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Hamdaoui, B.; Guizani, M. AoI-Aware Intelligent Platform for Energy and Rate Management in Multi-UAV Multi-RIS System. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2025, 22, 4376–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Peterson, T.; Vincenzi, D.; Doherty, S. Effect of time pressure and target uncertainty on human operator performance and workload for autonomous unmanned aerial system. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2016, 51, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.J.; Ng, E.M.; Low, K.H. Investigation and modeling of flight technical error (FTE) associated with UAS operating with and without pilot guidance. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 12389–12401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, T. Real-time drone surveillance system for violent crowd behavior unmanned aircraft system (uas)–human autonomy teaming (hat). In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/AIAA 40th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC) Conference, San Antonio, TX, USA, 3–7 October 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M.; McNeese, N.J.; Cooke, N.J. The evolution of human-autonomy teams in remotely piloted aircraft systems operations. Front. Commun. 2019, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutts, I.R.; Schall, M.C.; Matthews, J.; Gallagher, S.; Phillips, G.H.; Umphress, D. Human Performance in Highly Automated, Cyber Vulnerable Unmanned Aerial Systems: Effects of Operators’ Background and Task Load. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 2023, 53, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacher, A. Considerations for Airspace Integration Enabling Early Multi-Aircraft (m:N) Operations; No. NASA/TM-20250002264; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20250002264 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Grindley, B.; Parnell, K.J.; Cherett, T.; Scanlan, J.; Plant, K.L. Understanding the human factors challenge of handover between levels of automation for uncrewed air systems: A systematic literature review. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2024, 48, 1383–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhu, H.; Kim, M.; Cummings, M.L. The impact of different levels of autonomy and training on operators’ drone control strategies. ACM Trans. Hum. Robot Interact. (THRI) 2019, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhopatkar, R.A.; Howarter, J.A.; Ljungren, W. A Human Factors Assessment of Crew Mental Workload in m: N sUAS BVLOS Surveillance Operations. In Proceedings of the AIAA Aviation Forum and Ascend 2024, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 29 July–2 August 2024; p. 4317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickens, C.D. Situation awareness: Impact of automation and display technology. Situation awareness: Limitations and enhancement in the aviation environment, Report of the Advisory Group for Aerospace Research & Development, AGARD-CP-575, k2. In Proceedings of the Aerospace Medical Panel Symposium, Brussels, Belgium, 24–27 April 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tvaryanas, A.P. Human Systems Integration in Remotely Piloted Aircraft Operations. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2006, 77, 1278–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalouf, G.; Meier, K.; Richardson, T.; Guerin, D.; Watson, M.; Lundquist, U.P.S.; Afridi, S.; Rolland, E.G.; Jepsen, J.H.; Njoroge, W.; et al. Insights into Safe and Scalable BVLOS UAS Operations from Kenya’s OI Pejeta Conservancy. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Charlotte, NC, USA, 14–17 May 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohleber, R.W.; Matthews, G.; Lin, J.; Szalma, J.L.; Calhoun, G.L.; Funke, G.J.; Chiu, C.Y.P.; Ruff, H.A. Vigilance and automation dependence in operation of multiple unmanned aerial systems (UAS): A simulation study. Hum. Factors 2019, 61, 488–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M.R. Toward a theory of situation awareness in dynamic systems. Hum. Factors 1995, 37, 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, D.H.; Jewell, J.; Xu, H.H. Autonomous flight-test data in support of safety of flight certification. J. Air Transp. 2021, 29, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, D.; Cienfuegos, P.J.; Xu, H. Using Sensor Errors to Define Autonomous System Situational Awareness. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 193763–193781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, M.; Khosravian, E. A review of cognitive UAVs: AI-driven situation awareness for enhanced operations. AI Tech Behav. Soc. Sci. 2024, 2, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politowicz, M.S.; Chancey, E.T.; Glaab, L.J. Effects of autonomous sUAS separation methods on subjective workload, situation awareness, and trust. In Proceedings of the AIAA SciTech 2021 Forum, Virtual, 19–21 January 2021; p. 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinss, M.F.; Brock, A.M.; Roy, R.N. Cognitive effects of prolonged continuous human-machine interaction: The case for mental state-based adaptive interfaces. Front. Neuroergonomics 2022, 3, 935092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.D.; Seppelt, B.D. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Automation Design. In Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics, 4th ed.; Salvendy, G., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 1615–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cummings, M.L.; Welton, B. Assessing the impact of autonomy and overconfidence in UAV first-person view training. Appl. Ergon. 2022, 98, 103580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M.R. Supporting Human-AI Teams: Transparency, explainability, and situation awareness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 140, 107574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insaurralde, C.C.; Blasch, E. Ontological Airspace-Situation Awareness for Decision System Support. Aerospace 2024, 11, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAree, O.; Aitken, J.M.; Veres, S.M. Quantifying situation awareness for small, unmanned aircraft: Towards routine beyond visual line of sight operations. Aeronaut. J. 2018, 122, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, R.J.A.L.; Henderson, I.L.; Jackson, C.L. BVLOS unmanned aircraft operations in forest environments. Drones 2022, 6, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, V.; Pascarelli, C.; Colucci, M.; Afrune, P.; Corallo, A.; Avanzini, G. A Platform for Safe Operations of Unmanned Aircraft Systems in Critical Areas. Engineering 2025, 49, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emad Alfaris, R.; Vafakhah, Z.; Jalayer, M. Application of drones in humanitarian relief: A review of state of art and recent advances and recommendations. Transp. Res. Rec. 2024, 2678, 689–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanavino, M.; Avi, A.; Vilardi, A.; Guglieri, G. UAS testing in low pressure and temperature conditions. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Athens, Greece, 1–4 September 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1757–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highland, P.; Williams, J.; Yazvec, M.; Dideriksen, A.; Corcoran, N.; Woodruff, K.; Kirby, L.; Chun, E.; Kousheh HStoltz, J.; Schnell, T. Modelling of unmanned aircraft visibility for see-and-avoid operations. J. Unmanned Veh. Syst. 2020, 8, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.H.; Wang, D.B.; Ali, Z.A.; Ting Ting, B.; Wang, H. An overview of various kinds of wind effects on unmanned aerial vehicle. Meas. Control 2019, 52, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, L.; Kaabouch, N. Impact of weather factors on unmanned aerial vehicles’ wireless communications. Future Internet 2025, 17, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, T.; Starek, M.J.; Berryhill, J.; Quiroga, C.; Pashaei, M. Simulation and characterization of wind impacts on sUAS flight performance for crash scene reconstruction. Drones 2021, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalnysh, V.V.; Shvets, A.V.; Maltsev, O.V. Features of the influence of working conditions on psychophysiological functions of unmanned aircraft systems operators. Physiol. J. 2024, 70, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Irizarry, J. Human performance in UAS operations in construction and infrastructure environments. J. Manag. Eng. 2019, 35, 04019026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, J.C.; Mouloua, M.; Mangos, P.M.; Matthews, G. Gaming experience predicts UAS operator performance and workload in simulated search and rescue missions. Ergonomics 2022, 65, 1659–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancey, E.T.; Politowicz, M.S.; Ballard, K.M.; Unverricht, J.; Buck, B.K.; Geuther, S. Human-Automation Trust Development as a Function of Automation Exposure, Familiarity, and Perceived Risk: A High-Fidelity Remotely Operated Aircraft Simulation. J. Cogn. Eng. Decis. Mak. 2025, 19, 200–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharasees, O.; Kale, U. Human factors and AI in UAV systems: Enhancing operational efficiency through AHP and real-time physiological monitoring. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2024, 111, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atweh, J.; Riggs, S. Predicting Mental Demand of Teammates Using Eye Tracking Metrics: A Machine Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2025 HFES Symposium on Eye Tracking Research and Applications, Tokyo, Japan, 26–29 May 2025; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatcroft, J.M.; Jump, M.; Breckell, A.L.; Adams-White, J. Unmanned aerial systems (UAS) operators’ accuracy and confidence of decisions: Professional pilots or video game players? Cogent Psychol. 2017, 4, 1327628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouloua, M.; Ferraro, J.C.; Kaplan, A.D.; Mangos, P.; Hancock, P.A. Human factors issues regarding automation trust in UAS operation, selection, and training. In Human Performance in Automated and Autonomous Systems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.G.; Staveland, L.E. Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. Adv. Psychol. 1988, 52, 139–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). NASA Task Load Index (TLX) Paper and Pencil Package v. 1.0; Human Performance Research Group, NASA Ames Research Center: California, CA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20000021488/downloads/20000021488.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Atweh, J.A.; Riggs, S.L. Display Design Shapes How Eye Tracking, Workload, and Situation Awareness Predict Team Performance. In Proceedings of the 2025 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS), Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2 May 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostock, N.; Wickramasuriya, M.; Webster-Giddings, A.; Costello, D. Drone Operator Workload Analysis for Integration onto a Naval Vessel. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2025, 111, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnick, G.; Schulte, A. Scalable autonomy concept for reconnaissance UAVs on the basis of an HTN agent architecture. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Arlington, VA, USA, 7–10 June 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, B.; Donald, R.; Dumas, C.; Ahmadzadeh, S.R. Methods for combining and representing non-contextual autonomy scores for unmanned aerial systems. In Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Conference on Automation, Robotics and Applications (ICARA), Prague, Czech Republic, 18–20 February 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebensky, S.; Carroll, M.; Bennett, W.; Hu, X. Impact of heads-up displays on small, unmanned aircraft system operator situation awareness and performance: A simulated study. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2022, 38, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malyuta, D.; Brommer, C.; Hentzen, D.; Stastny, T.; Siegwart, R.; Brockers, R. Long-duration fully autonomous operation of rotorcraft unmanned aerial systems for remote-sensing data acquisition. J. Field Robot. 2020, 37, 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Chandramoorthy, N.; Swaminathan, K.; Chen, P.Y.; Reddi, V.J.; Raychowdhury, A. Berry: Bit error robustness for energy-efficient reinforcement learning-based autonomous systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 60th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 9–13 July 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaitzakis, M.; Vitzilaios, N. UAS Control under GNSS Degraded and Windy Conditions. Robotics 2023, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porat, T.; Oron-Gilad, T.; Rottem-Hovev, M.; Silbiger, J. Supervising and controlling unmanned systems: A multi-phase study with subject matter experts. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Merwe, K.; Mallam, S.; Nazir, S. Agent transparency, situation awareness, mental workload, and operator performance: A systematic literature review. Hum. Factors 2024, 66, 180–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Safany, R.; Bromfield, M.A. A human factors accident analysis framework for UAV loss of control in flight. Aeronaut. J. 2025, 129, 1723–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Li, K.W. Perceived difficulty, flight information access, and performance of male and female novice drone operators. Work 2022, 72, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Aviation Administration. Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge; FAA-H-8083-25C; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aviation/phak (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- ICAO. Annex 19, to the Convention on International Civil Aviation. Safety Management, 2nd ed.; EASA: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; Available online: https://elibrary.icao.int/reader/250466/&returnUrl%3DaHR0cHM6Ly9lbGlicmFyeS5pY2FvLmludC9wcm9kdWN0LzI1MDQ2NiUzRl9nbCUzRDEqMTc5ZmhtZypfZ2EqTWpFeU1ERXhPRFEyTnk0eE56SXdORFU0TmprMipfZ2FfOTkyTjNZRExCUSpNVGN5TXpZNU1UVTRNaTQzTGpBdU1UY3lNelk1TVRVNE1pNHdMakF1TUEuLg%3D%3D?productType=ebook (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Roth, G.; Schulte, A.; Schmitt, F.; Brand, Y. Transparency for a workload-adaptive cognitive agent in a manned–unmanned teaming application. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 2019, 50, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endsley, M.R. Design and evaluation for situation awareness enhancement. Proc. Hum. Factors Soc. Annu. Meet. 1988, 32, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fang, W.; Qiu, H.; Wang, Y. The Impact of Automation Failure on Unmanned Aircraft System Operators’ Performance, Workload, and Trust in Automation. Drones 2025, 9, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, M.; Martelli, P.F.; Roberts, K.H. Reliability-Seeking virtual organizations at the margins of systems, resources and capacity. Saf. Sci. 2023, 168, 106327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Autonomy Level | Description | Definition | Operationalization |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | No Autonomy | Operator is eyes on and hands on. Operator controls all aspects of flight in VLOS operations. | VLOS: Primary operational control is with the operator. No autonomous operations. |

| 1 | Assistive Autonomy | Operator is assisted with limited autonomous capabilities to perform actions such as altitude control or obstacle warning detection. | VLOS: Primary operational control is with the operator, with some autonomy. |

| 2 | Partial Autonomy | Operator is allowed temporary hands-off operations, but is eyes on to monitor operations. UAS has more operational capabilities, such as taking flight action, autonomous takeoff and landing, and medium-range detect and avoid operations. | VLOS: Operator has temporary hands-off operations but still has eyes on to monitor operations. |

| 3 | Conditional Autonomy | Operator temporarily takes eyes and hands off operations. The UAS’s flight management system (FMS) will start to take control of the operation. | BVLOS: Operator is temporarily eyes and hands off; UAS FMS starts to control UAS operations. |

| 4 | High Autonomy | Autonomy is the primary control method. The operator intervenes by exception or only in specific situations (e.g., emergencies). Most operational actions are controlled by the UAS FMS. | BVLOS: UAS FMS autonomy is the primary operational control, except in emergencies or specific situations. |

| 5 | Full Autonomy | Fully autonomous UAS operations. The human operator is by default eyes off and hands off. The UAS FMS conducts all actions to ensure the safety and efficiency of operations. | BVLOS: UAS operations are completely autonomous, driven by the UAS FMS. |

| Construct | Variable | Definition | Operationalization | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 | ||||

| System Performance | Endurance: | |||

| Distance Flown | UAS distance traveled from launch to landing [102] | UAS Distance Flown/Flight Time (km/min) | UAS | |

| Speed | Speed at which the UAS was flown [45] | UAS Speed/Flight Time (Km/hr)/min)) | UAS | |

| Consumption | Percentage of energy used by the UAS during the flight [51] | UAS Consumption Watt-hours (energy used)/Flight Time (Wh/min) | UAS | |

| Efficiency: | Percentage of battery power remaining [103] | Battery Level %/Flight Time (percentage/min) | UAS | |

| Waypoint Deviation: | Standard Deviation of UAS direction from predicted direction, driven by wind [56] | Standard Deviation of UAS direction from predicted direction (wind direction)/flight time (Deg/min) | UAS | |

| Hypothesis 2 | ||||

| Operator Performance | Track keeping: | Flight path Trackkeeping [67,101] | FAA General Operation Manual GOM/Observation Assessment 6: Monitoring Flight Path -Monitoring difference between defined route & UAS flight -Recognizing difference between defined route & UAS flight -Documenting difference between defined route & UAS flight HE (Highly Effective), E (Effective), NE (Not Effective), U (Unsatisfactory) | GOM Assessment, Observation |

| Hypothesis 3 | ||||

| Situation Awareness | Situation Monitoring: | Flight, system and environmental monitoring, Monitoring altitude of mission [25,55] | FAA General Operation Manual GOM/Observation Assessment 7: Situation Awareness –Mission structure followed –Monitoring waypoints –Monitoring altitude –Monitoring altitude consistency –Monitoring altitude relative to obstacles –Collisions avoided HE (Highly Effective), E (Effective), NE (Not Effective), U (Unsatisfactory) | GOM Assessment, Observation |

| Flight Type | UAS Endurance | UAS Endurance | UAS Endurance | UAS Efficiency | UAS Waypoint Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance Flown/Flight Time (km/min) | Speed/ Flight time (km/hr./min) | Consumption/ Flight time (Wh/min) | Battery Level/Flight Time (percentage/min) | Waypoint Standard Dev /Flight Time (Standard Dev in degrees/min) | |

| VLOS (n = 16) | 1.377826 | 1.279482 | 24.146681 | 12.23% | 1.827505 |

| BVLOS (n = 3) | 1.662027 | 0.996855 | 21.960982 | 10.68% | 0.523837 |

| % Difference | 20.63% | −22.09% | −9.05% | −12.65% | −71.34% |

| VLOS AM Avg | 1.438300 | 1.188411 | 24.146681 | 11.01% | 1.696643 |

| BVLOS AM Avg | 1.980919 | 0.374070 | 15.108140 | 3.09% | 0.52387 |

| % Difference | 37.73% | −68.52% | −31.35% | −71.96% | −69.13% |

| VLOS PM Avg | 1.341542 | 1.334125 | 24.302787 | 12.96% | 1.906022 |

| BVLOS PM Avg | 1.024242 | 2.242424 | 35.666667 | 25.87% | 4.818182 |

| % Difference | −23.65% | 68.08% | 46.76% | 99.65% | 152.79% |

| VLOS AM Avg | 1.438300 | 1.188411 | 23.886503 | 11.01% | 1.696643 |

| VLOS PM Avg | 1.341542 | 1.334125 | 24.302787 | 12.96% | 1.906022 |

| % Difference | 6.73% | −12.26% | −1.74% | 17.62% | −12.34% |

| BVLOS AM Avg | 1.980919 | 0.374070 | 15.108140 | 3.09% | 0.52387 |

| BVLOS PM Avg | 1.024242 | 2.242424 | 35.666667 | 25.87% | 4.818182 |

| % Difference | −48.29% | 499.47% | 136.08% | 737.58% | 819.79% |

| Flight Type | Wind Speed (m/sec) | Wind Direction (Direction, Degrees) | % Wind Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| VLOS (n = 16) | |||

| WNW | 25.00% | ||

| WSW | 25.00% | ||

| NNW | 50.00% | ||

| Average VLOS | 1.58 | 302.99 | WNW |

| BVLOS (n = 3) | |||

| WNW | 66.67% | ||

| WSW | 33.33% | ||

| Average BVLOS | 1.3 | 277.87 | W |

| % Difference Average VLOS vs. Average BVLOS | −17.62% | −8.29% |

| Statistical Power | Statistical Power | |

|---|---|---|

| System Performance | ||

| Operator Performance | ||

| Power | Low (Type II errors) | Low (Type II errors) |

| Flight Type | H2: Track-Keeping GOM Assessment 6 | H3: Situation Awareness GOM Assessment 7 | Number of Flights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scale for Averages: Highly Effective (HE) = 4, Effective I = 3, Not Effective (NE) = 2, Unsatisfactory (US) = 1 | Monitoring Flight Path —Monitoring difference between defined route and UAS flight —Recognition of difference between defined route and UAS flight —Documentation of differences between define route and UAS flight | Monitor Altitude —Mission structure followed —Monitoring waypoints —Monitoring altitude —Monitoring altitude consistency —Monitoring altitude relative to obstacles —Collisions avoided | Morning, Afternoon Flights |

| VLOS Average (n = 16) | 3.88 | 3.94 | |

| BVLOS Average (n = 3) | 3.67 | 4.000 | |

| % Difference | −5.38% | 1.59% | |

| VLOS HE % | 62.50% | 93.75% | |

| BVLOS HE% | 66.67% | 100% | |

| % Difference | 6.67% | 6.67% | |

| VLOS HE% AM | 83.3% | 83.33% | 6 Morning Flights |

| VLOS HE % PM | 90.00% | 100% | 10 Afternoon Flights |

| % Difference | 8% | 20% | |

| VLOS HE% AM | 83.3% | 83.3% | 6 Morning Flights |

| BVLOS HE % AM | 50.00% | 100% | 2 Morning Flights |

| % Difference | −20% | 20.0% | |

| VLOS HE % PM | 90.00% | 100% | 10 Afternoon Flights |

| BVLOS HE % PM | 100% | 100% | 1 Afternoon Flight |

| % Difference | 11.11% | 0.0 | |

| BVLOS HE % AM | 50.00% | 100% | 2 Morning Flights |

| BVLOS HE % PM | 100% | 100% | 1 Afternoon Flight |

| % Difference | 50% | 0.0% |

| Flight Type | Wind Direction | Average Wind Direction (Degrees) | Number of Flights Morning, Afternoon |

|---|---|---|---|

| VLOS AM | NW | 315.3 | 6 Morning Flights |

| BVLOS AM | W | 265.75 | 2 Morning Flights |

| % Difference | −15.72% | ||

| VLOS PM | WNW | 295.6 | 10 Afternoon Flights |

| BVLOS PM | WNW | 302.1 | 1 Afternoon Flight |

| % Difference | 2.2% | ||

| VLOS AM | NW | 315.3 | 6 Morning Flights |

| VLOS PM | WNW | 295.6 | 10 Afternoon Flights |

| % Difference | 6.25% | ||

| BVLOS AM | W | 265.75 | 2 Morning Flights |

| BVLOS PM | WNW | 302.1 | 1 Afternoon Flight |

| % Difference | 13.68% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grabowski, M.R.; Morgan, G.; McGarvey, J.; Roberts, S.; Squire, R.; Ibanez, S.; Bringsjord, S.; Rowen, A. Human Machine Autonomy in Medical and Humanitarian Logistics in Remote and Infrastructure-Poor Settings. Drones 2025, 9, 841. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120841

Grabowski MR, Morgan G, McGarvey J, Roberts S, Squire R, Ibanez S, Bringsjord S, Rowen A. Human Machine Autonomy in Medical and Humanitarian Logistics in Remote and Infrastructure-Poor Settings. Drones. 2025; 9(12):841. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120841

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrabowski, Martha R., Gwendolyn Morgan, James McGarvey, Steve Roberts, Robert Squire, Sebastian Ibanez, Selmer Bringsjord, and Aaron Rowen. 2025. "Human Machine Autonomy in Medical and Humanitarian Logistics in Remote and Infrastructure-Poor Settings" Drones 9, no. 12: 841. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120841

APA StyleGrabowski, M. R., Morgan, G., McGarvey, J., Roberts, S., Squire, R., Ibanez, S., Bringsjord, S., & Rowen, A. (2025). Human Machine Autonomy in Medical and Humanitarian Logistics in Remote and Infrastructure-Poor Settings. Drones, 9(12), 841. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120841