Highlights

What are the main findings?

- A sliding mode controller integrated with a state compensation function observer (SCFO) is applied to a small tailless vertical take-off and landing uncrewed aerial vehicle (ST-VTOL UAV) to address instability under wind disturbances. By embedding derivative terms from the system dynamics, the SCFO improves disturbance estimation, enabling the controller to reduce pitch and altitude RMSE by up to 65% and 88% in simulation and to lower hovering RMSE by about 33% in experiments. Validation is performed using a programmable platform combining a fan-array wind generator, indoor motion capture, and a lightweight ST-VTOL prototype.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The proposed approach enhances hovering stability and wind-disturbance rejection for small VTOL UAVs while maintaining computational efficiency, offering a practical reference for observer-based anti-disturbance and trajectory-tracking control.

Abstract

As a classical disturbance observation method, the extended state observer (ESO) is commonly used in controllers for disturbance estimation and feedback control. However, the ESO relies mainly on input–output signals and does not fully utilize information from system derivatives and the system’s dynamic structure. This underuse limits its effectiveness for vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs). This limitation is especially problematic in small tailless VTOL UAVs (ST-VTOL UAVs). While these UAVs can switch modes and operate in confined spaces, they are highly susceptible to disturbances such as wind. To address this issue, this paper applies a novel disturbance rejection controller to an ST-VTOL UAV. Specifically, the controller replaces the traditional linear ESO with an enhanced state compensation function observer (SCFO) and integrates it with an equivalent sliding mode controller (ESMC). Simulation results demonstrate that the SCFO achieves substantially higher disturbance-estimation accuracy than both the classical ESO and its fal–function–enhanced variant. Flight experiments on the ST-VTOL UAV confirm that the proposed method reduces tracking error compared with a conventional PID controller and maintains stable hovering under external disturbances.

1. Introduction

In recent years, small vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) have attracted considerable attention due to their versatility [1]. Configurations like helicopter and compound rotorcraft suffer from poor forward flight performance, while the complex design of tilt-rotor wings makes them difficult to integrate into compact UAV platforms. Vectored-thrust, where the propulsion can be actively deflected to generate multi-axis control torques, enables high maneuverability. This enables rapid switching between flight modes and performing complex maneuvers that are not possible with fixed-wing aircraft. Furthermore, the tailless flying wing layout further reduces structural weight, reduces fuselage size, and improves aerodynamic efficiency, enabling the inclusion of more equipment and achieving superior forward flight performance. These characteristics reduce reliance on the take-off/landing environment, which offers potential for air combat, surveillance, and rescue missions [2]. However, the small tailless VTOL UAV (ST-VTOL UAV) faces stability challenges during take-off and landing. Although tailless vectored thrust configurations offer excellent maneuverability, they also increase the complexity of controller design. Therefore, it is necessary to design a controller that addresses the effects of wind disturbance.

Existing research has focused mainly on two directions to enhance the wind-disturbance rejection capability of small UAVs: perception-based methods and observer-based methods. Perception-based methods rely on additional airflow sensors to directly measure the surrounding wind field and feed the obtained information to the controller as a feedforward signal [3,4]. For example, a thermistor-based airflow sensing method was proposed, in which real-time wind speed measurements were combined with feedforward compensation, effectively improving the flight stability of small UAVs within a wind speed range of 0.5–1.2 m/s [5]. More recently, a skin-like airflow odometry framework was introduced for small UAVs, in which distributed thermal anemometers embedded in wingtips were fused with inertial data through a transformer-enhanced gated recurrent unit (GRU) network, thereby mitigating drift and improving state estimation accuracy under complex airflow conditions [6]. Nevertheless, such methods depend strongly on sensor accuracy and response speed. At the same time, their additional weight, power consumption, and integration complexity bring challenges for practical deployment on small UAV platforms.

In contrast, observer-based methods avoid direct wind sensing by treating the external wind field as an unknown disturbance, which is estimated and compensated through observers [7,8,9]. Representative approaches include the extended state observer (ESO) [10], the nonlinear disturbance observer (NDO) [11], and the unknown input observer (UIO) [12]. These frameworks can estimate and compensate for disturbances based solely on system input–output data, eliminating the need for airflow sensors. For example, a robust flight controller based on linear active disturbance rejection control was proposed to guarantee quadrotor stability under gusty conditions [13], and a disturbance rejection control scheme using multiple observers was designed to maintain stable flight under simultaneous wind and load-swing disturbances [14]. Such methods are attractive for small UAVs, although their effectiveness depends on the richness and observability of feedback signals.

Building upon disturbance estimation, researchers have further investigated how such information can be integrated into control laws. Classical proportional–integral–derivative (PID) control [15,16,17] is simple and widely adopted, but it performs poorly under strong nonlinearities and large disturbances. Model predictive control (MPC) [18,19] can explicitly handle constraints but incurs high computational cost; incremental nonlinear dynamic inversion (INDI) [20,21] improves adaptability under rapidly changing conditions; and intelligent control approaches [22,23] show promising adaptability but rely heavily on training data and computational resources. Sliding mode control (SMC) is widely applied due to its inherent robustness against uncertainties [24,25], yet the need for large switching gains often induces actuator chattering. To alleviate this issue, advanced variants such as non-singular terminal SMC and finite-time backstepping SMC have been proposed [26], while an adaptive fractional-order non-singular terminal SMC with a fixed-time disturbance observer has been demonstrated to significantly improve robustness for carrier-based UAVs with complex layouts under random disturbances [27].

Recent trends increasingly emphasize the combination of observer-based estimation with robust control to form dual-loop frameworks. The outer loop employs SMC to ensure global robustness, while the inner loop observer provides fast disturbance compensation [28]. Typical examples include ADRC frameworks based on ESO [29] and high-order ESOs with improved reaching laws [30]. However, ESO-based methods are limited by their reliance on single-channel output information, underutilization of structural dynamics, and reduced effectiveness when compensating for unknown nonlinearities [31]. In addition to ESO-based designs, several finite-time, fixed-time, and prescribed-time observers (FTO/FXTO/PTO) have been developed to achieve convergence within bounded or preassigned time intervals. FTO ensures rapid convergence but depends on initial conditions and often requires high observer gains [32]. FXTO removes the dependence on initial conditions by introducing homogeneous feedback with time-invariant settling times [33]. PTO further guarantees convergence within a user-defined duration through nonlinear or time-varying high-gain mechanisms [34,35]. However, these designs typically rely on strong homogeneity or nonlinear damping structures, which increase implementation complexity and amplify sensor noise in practice, especially for small UAVs subject to measurement disturbances.

To overcome these limitations, a disturbance rejection framework combining the state compensation function observer (SCFO) with an equivalent SMC (ESMC) has been introduced [10]. We call this framework SSMC. Unlike ESO- or high-gain-based designs, the SCFO maintains a linear-in-error structure while embedding model Jacobians and a dynamic compensation term to explicitly estimate the disturbance variation rate. This model-aware yet bandwidth-efficient formulation enables rapid disturbance reconstruction and smooth control action without the excessive gain tuning or noise amplification typical of nonlinear homogeneous observers. By incorporating disturbance derivative estimation and smooth switching mechanisms, the SSMC framework significantly improves the trajectory-tracking accuracy of small UAVs under wind disturbances, offering a practically robust solution for flight control in complex and uncertain environments.

In summary, while significant progress has been made in robust disturbance-aware control of UAVs, further research is needed to evaluate the performance of these approaches on novel platforms requiring high wind resistance, such as ST-VTOL UAVs. This study demonstrates the integration of SSMC on an ST-VTOL UAV. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

- The SSMC framework introduces an SCFO that embeds system-derivative and Jacobian information directly into the observer dynamics. This design enables faster and smoother disturbance reconstruction than classical ESO-based methods, while avoiding high-gain amplification and preserving robustness for small tailless VTOL UAVs with strong aerodynamic coupling.

- A programmable experimental platform was developed by integrating a reconfigurable fan-array wind generator (FAWG) with a motion-capture-based indoor testbed and a lightweight ST-VTOL prototype. This setup enables repeatable generation of spatial–temporal wind disturbances and provides a refined methodology for validating disturbance-aware controllers on miniature VTOL systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the dynamic modeling of the ST-VTOL UAV used in this paper. Section 3 introduces the proposed control framework. Section 4 provides both simulation and experimental results to demonstrate the feasibility of SSMC on ST-VTOL UAV. Finally, Section 5 concludes the study.

2. Dynamics Modeling

This section introduces the coordinate systems and establishes the six degrees of freedom (6-DOF) equations of motion for the ST-VTOL UAV. The equations are then simplified to a longitudinal three degrees of freedom (3-DOF) form, incorporating wind disturbances.

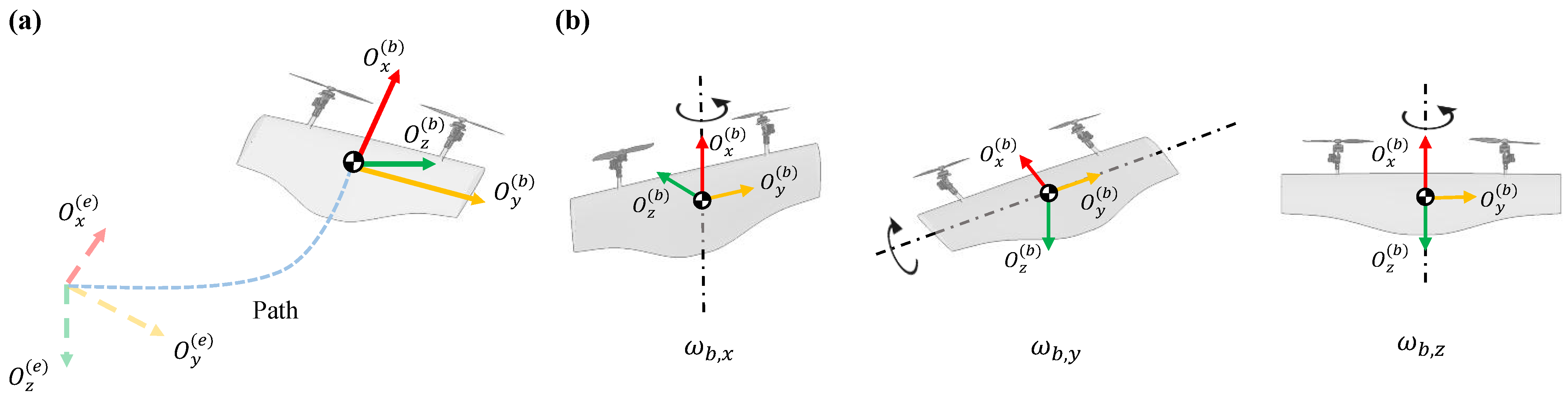

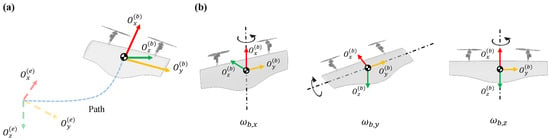

The definition of the coordinate system can be seen in Figure 1a. The inertial frame is fixed at the takeoff point and aligned with the North-East-Down (NED) directions. The body-fixed frame is attached to the ST-VTOL UAV’s center of gravity, with pointing forward, pointing downward, and completing the right-hand rule, as illustrated in Figure 1b. The rotation matrix from the body frame to the inertial frame [36] is:

where , , and denote the Euler angles corresponding to roll, pitch, and yaw, respectively. Specifically, is the angle between the UAV’s symmetry plane and the vertical plane containing the body axis , and it is defined as positive when the UAV rolls to the right. is the angle between the body axis and the horizontal plane –, defined as positive when the UAV pitches nose-up. is the angle between the projection of the body axis onto the horizontal plane – and the inertial axis , defined as positive when the UAV yaws to the right.

Figure 1.

Coordinate system definition: (a) Schematic of the flight transition from the inertial frame to the body frame . (b) The three rotational axes of the body frame. The half-black, half-white circle represents the center of gravity of the ST-VTOL UAV.

Additionally, the aerodynamic frame is defined along the direction of the relative airflow, where points opposite to the incoming airflow (aligned with the flight velocity vector), is perpendicular to and points upward in the lift direction, and completes the right-hand coordinate system. The rotation matrix from the aerodynamic frame to the body frame is:

where and denote the angle of attack and sideslip angle, respectively. Specifically, is defined as the angle between the projection of the velocity vector on the UAV’s symmetry plane and the body axis , and it is defined as positive when the projection lies above the -axis. is defined as the angle between the velocity vector and the UAV’s symmetry plane, and it is defined as positive when the velocity vector lies on the right-hand side of the symmetry plane.

These coordinate systems form the foundation for expressing the aerodynamic and propulsive forces acting on the ST-VTOL UAV.

In order to describe the relationship between the forces and moments acting on an ST-VTOL UAV and its flight state, the motion can be fully characterized by a 6-DOF equation, including three translational motions in the inertial frame and three rotational motions about the body axes. The dynamic equations can be derived from the Newton–Euler equations [36]:

where m is the mass of the ST-VTOL UAV, is the velocity vector in the inertial frame, g is the gravitational acceleration, is the unit vector of gravity in the inertial frame, is the external force acting on the ST-VTOL UAV in the body frame, is the inertia matrix where , , and are the principal moments of inertia about the , , and axes, respectively, is the angular velocity in the body frame, and is the external moment acting on the ST-VTOL UAV in the body frame.

There exists a linear relationship between the body angular velocity and the time derivatives of the Euler angles [37]:

The forces acting on the ST-VTOL UAV in the body frame mainly include the aerodynamic force and the thrust force , while the moments mainly consist of the aerodynamic moment and the thrust moment , which are expressed as follows:

2.1. Thrust and Thrust Moment Calculation

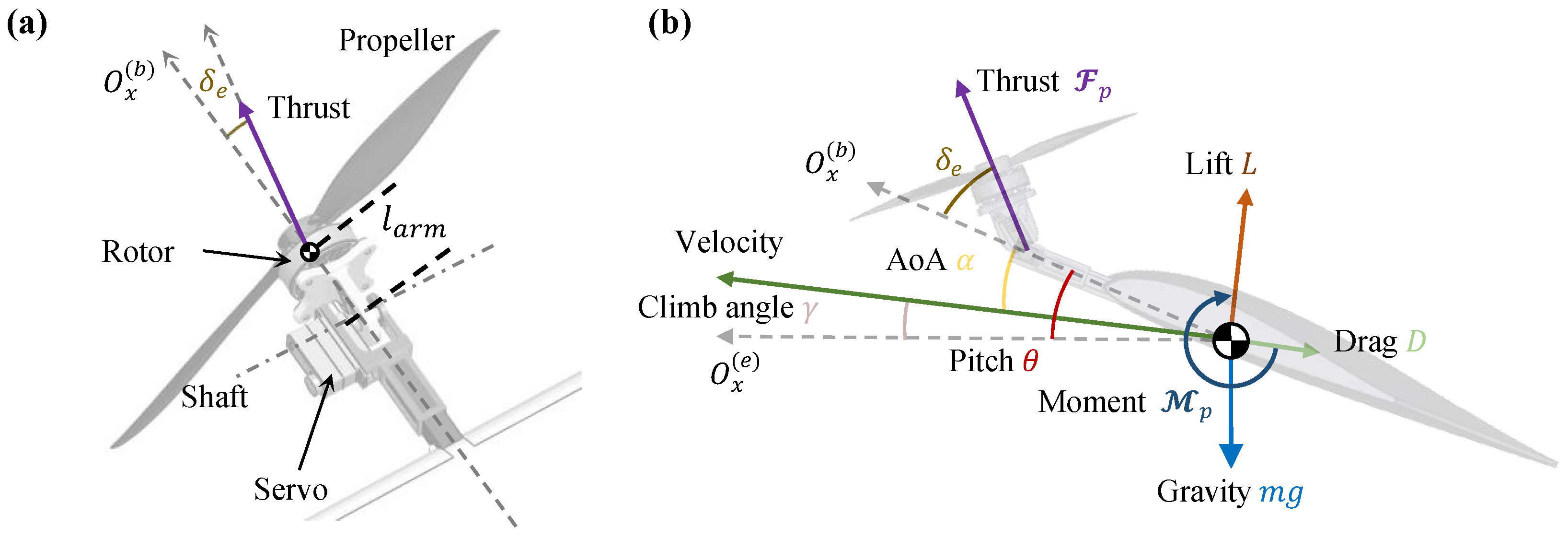

The ST-VTOL UAV consists of two servos and a motor propeller, which form a vector propulsion unit through a linkage mechanism to provide thrust and thrust moment, as illustrated in Figure 2a,b. Taking the left propeller as an example, the magnitudes of the thrust and torque are calculated as:

where and respectively denote the thrust and torque coefficients of the propeller, which are obtained from CFD analysis [38]. is the air density, n is the propeller rotational speed with the unit of revolutions per second (rps), and is the propeller diameter.

Figure 2.

Vector propulsion unit: (a) Vector-thrust mechanism. (b) Definition of angle and force.

When the propellers on both sides accelerate synchronously, the ST-VTOL UAV gains thrust for acceleration or climbing. Differential propeller speeds generate a yawing moment , while identical servo deflections produce a pitching moment . Conversely, opposite servo deflections induce a rolling moment . By vector summation of these components, the resultant thrust and thrust moment acting on the ST-VTOL UAV are obtained.

It should be noted that we define the angle between the thrust direction of the propeller and as the vectored thrust deflection angle , which is shown in Figure 2. The direction of the propeller thrust is related to the attitude and the . governs the decomposition of thrust into horizontal and vertical components and generates an additional pitching moment depending on the arm length between the thrust axis and the center of gravity. In addition, we define the throttle command as , which represents the percentage of the maximum available thrust.

2.2. Aerodynamic Force and Aerodynamic Moment Calculations

The aerodynamic model used in this paper is defined as follows [39]:

where is the airspeed of the ST-VTOL UAV, given by , and is the wind velocity expressed in the inertial frame. is the dynamic pressure, S is the wing reference area, and is the mean aerodynamic chord. , , and represent the lift, side force, and drag coefficients, respectively. The calculated values of L, Y, and D correspond to the three components of along the aerodynamic frame . The aerodynamic force can then be obtained through . , , and represent the rolling, pitching, and yawing moment coefficients, corresponding to the aerodynamic moments , , and about the three body axes. These components together constitute the aerodynamic moment vector in the body frame.

During the rotational motion of the ST-VTOL UAV, aerodynamic damping moments are generated, and the coupling between aerodynamic forces and rotational motion becomes significant. The open-source tool AVL can be utilized to compute the dynamic stability derivatives, such as . The nondimensional angular velocity is defined as .

Taking the pitching moment coefficient as an example, it can be expressed as:

where is the static pitching moment coefficient, which can be obtained from wind tunnel experiments [38]. The superscript denotes the components related to thrust effects. Other aerodynamic moment coefficients are defined in a similar manner.

2.3. Dynamics Simplification

In this paper, we focus primarily on the take-off and landing phases under wind disturbances. Inspired by the study in [40], the wind resistance of VTOL fixed-wing UAVs and similar platforms reaches its optimum when the wind direction is aligned with the heading direction. Due to the configuration characteristics, the main stability challenge introduced by the fixed wings lies in the longitudinal symmetric plane. Moreover, wind tunnel experiments have demonstrated that the ST-VTOL UAV exhibits lateral-directional stability [38]. Therefore, to achieve the theoretically optimal wind-resistance performance while reducing the complexity of controller design, the anti-disturbance control strategy adopted in this paper is mainly developed for the longitudinal dynamics.

Therefore, the 6-DOF dynamics in Equation (3) can be reduced to a 3-DOF model in the longitudinal plane. After simplification, in Equation (3), the translational equations retain only the terms related to and , while the rotational equation retains only the terms associated with the pitch angle .

By combining aerodynamic forces, propeller thrust, and gravity, and further incorporating wind-induced uncertainties, the longitudinal 3-DOF dynamics of the ST-VTOL UAV are formulated as:

where is the pitch-axis moment of inertia, is the flight path angle. The additive terms and represent the equivalent wind-induced disturbances on vertical and pitch accelerations.

2.4. Wind Disturbance Model Establishment

To make the wind field model more closely resemble the real environment, the designed wind field model requires a high wind speed and variable direction within the wind field. Strong winds and turbulent winds are superimposed to create a turbulent wind field with high wind speeds and uncertain wind directions. The wind field model is incorporated as an interference term into the dynamic model of the ST-VTOL UAV, and the controller is designed to compensate for this interference term, thereby achieving the goal of resisting wind disturbances.

The Dryden model is used to describe the turbulent wind field. A Gaussian-distributed random signal is generated by a computer. To output a suitable turbulent signal, the spatial and temporal spectra of the model are decomposed to obtain the shaping filter transfer functions in each direction. The white noise is then passed through the shaping filter to obtain the output of the turbulent wind field model, which is more closely aligned with the actual wind field. Atmospheric disturbances encompass a range of temporal and spatial scale motions, and their generation mechanisms and development processes differ. The Dryden atmospheric turbulence model passes a standard Gaussian white noise sequence through a shaping filter to form a colored noise sequence, completing the simulation of atmospheric turbulence [41]. The time spectrum function of the Dryden model is:

where denotes the temporal frequency, , , and are the turbulence scale lengths, and , , and are the turbulence intensities. The components u, v, and w represent the velocity vector along .

Since the flight altitude of the ST-VTOL UAV is limited, the turbulence intensity and turbulence scale under low-altitude conditions can be calculated as follows:

where h denotes the flight altitude, and represents the wind speed at a height of 6.096 m.

Decompose and simplify Equation (10) into first order, then the fixed frequency filter is:

In the subsequent simulations, the disturbances and will be generated based on the Dryden model.

In summary, the longitudinal model (9) explicitly incorporates aerodynamic, propulsive, and gravitational effects while representing wind disturbances through the additive terms and . This formulation provides a tractable yet sufficiently accurate foundation for subsequent controller design, where disturbances will be estimated and compensated in real-time.

3. Controller Design

Building on the dynamic model in Section 2, this section first presents the overall control architecture, then details lateral PID, horizontal position shaping, and a longitudinal ESMC enhanced by an SCFO.

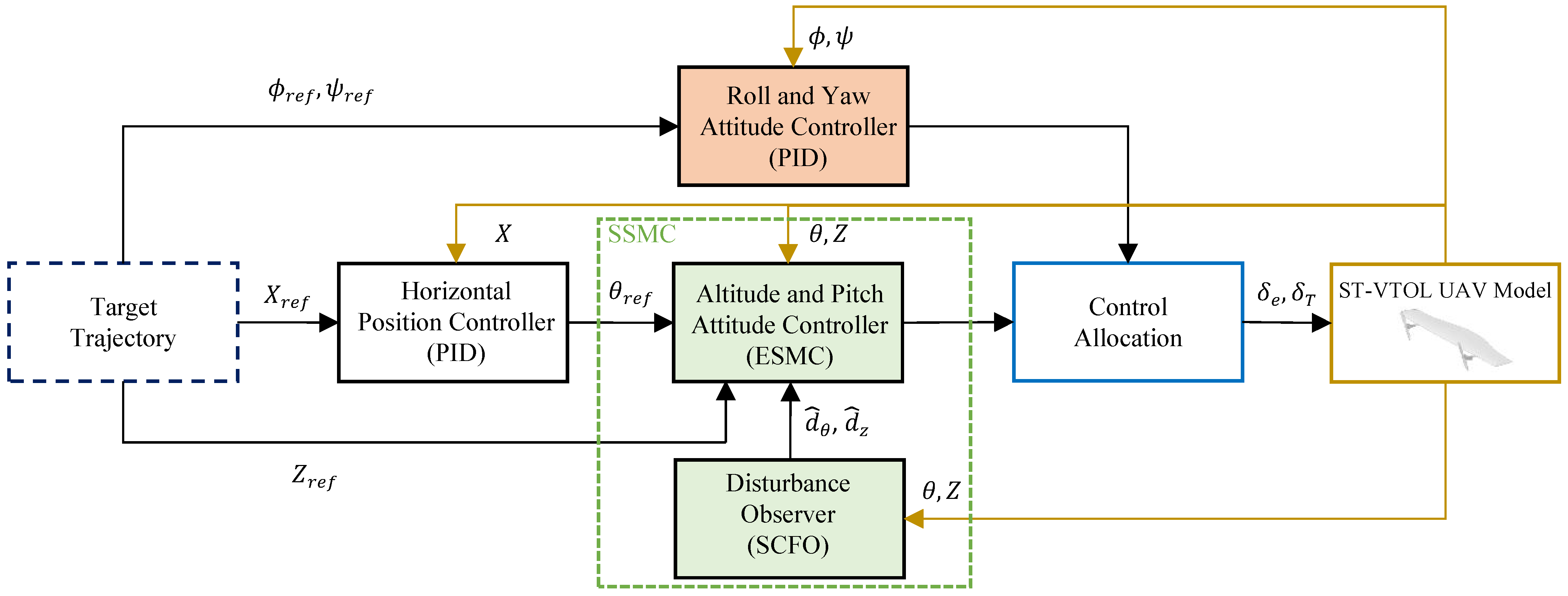

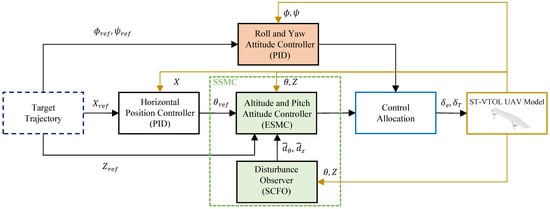

To achieve precise hovering under external wind disturbances, we use the new anti-disturbance control method—SSMC. Figure 3 shows its overall control structure. The position and attitude controllers are designed using a cascaded state feedback strategy. Specifically, the lateral control goal is to keep the roll and yaw angles of the ST-VTOL UAV at zero degrees, which a traditional PID controller achieves. For simplicity of notation, in the remainder of this section, X and Z refer to the corresponding variables and . The longitudinal control objective is to stabilize the ST-VTOL UAV at the reference position . First, the horizontal position controller uses a PID method to generate the desired pitch angle . Simultaneously, the desired altitude is also input into the ESMC and the desired pitch angle. Then, the ESMC tracks and concurrently. Finally, the outputs of the lateral and longitudinal controllers are mapped through the control allocation module. This module is responsible for calculating the actual torque and thrust commands applied to the drone. During this process, the ST-VTOL UAV model continuously updates the system states. These system states are fed back to each sub-controller to ensure closed-loop stability and robustness.

Figure 3.

Control logic and variable passing.

The proposed control framework satisfies the following properties: the high-bandwidth roll–yaw PID inner loops maintain lateral-directional stability and rapidly suppress small-angle deviations caused by crosswinds, while the low-bandwidth longitudinal SSMC governs pitch and altitude dynamics under dominant aerodynamic and thrust disturbances. Within the specified operating envelope—small attitude angles, unsaturated actuators, and weak cross-axis coupling—the outputs of both controllers can be linearly superposed through the control allocation module. This linear superposition ensures consistent torque and thrust distribution among actuators and allows the overall closed-loop system to maintain stability and robustness.

The following subsections provide more detailed calculations and derivations of each controller component.

3.1. Roll and Yaw Attitude Controller

The lateral control objective is to regulate the ST-VTOL UAV’s roll and yaw angles to their desired reference values, i.e., and . is derived from attitude control requirements. because the ST-VTOL UAV achieves its maximum wind resistance when its heading angle and wind speed are aligned, as described in Section 2. In this case, the dynamic model can also be simplified to 3 degrees of freedom. Furthermore, in Section 4.3, the direction of the maximum wind speed generated by the experimental equipment is parallel to the ST-VTOL UAV’s heading, which also ensures the rationality of the control target setting.

To this end, conventional PID controllers are implemented independently for the roll and yaw channels. The control laws are defined as follows.

For the roll channel:

where denotes the roll control input, is the roll tracking error, is its time derivative, and represents the time variable of integration. The parameters , , and are the proportional, integral, and derivative gains, respectively, tuned to ensure fast transient response and elimination of steady-state error.

For the yaw channel:

where is the yaw control input, denotes the yaw tracking error, and is its time derivative. Similarly, , , and are the PID gains governing the yaw loop.

By independently regulating roll and yaw angles, these PID controllers ensure that the ST-VTOL UAV maintains lateral stability and effectively suppresses deviations from the commanded attitude.

3.2. Horizontal Position Controller

The horizontal position controller generates , the input to the subsequent longitudinal control loop. This controller is designed to combine position and velocity feedback in a nested structure. The position error is defined as , and the velocity error is expressed as . The control law is given by:

where and are the proportional gains for position and velocity feedback, respectively. This formulation ensures that both the horizontal displacement and velocity are simultaneously regulated.

3.3. Attitude and Pitch Altitude Controller

The altitude and pitch attitude controller is implemented using an SSMC.

3.3.1. Control Model

The total disturbance term accounts for model errors resulting from uncertain wind direction and time-varying aerodynamic disturbances encountered during flight. This modeling approach simplifies subsequent controller design because any deviation from the nominal aerodynamic force calculation can be equivalently treated as an additional disturbance in the system dynamics. This paper reconstructs the dynamic model (9) and expresses it in state space form.

Since the primary control objective is to regulate pitch motion and altitude, the choice of system states is limited to the longitudinal channel. The state vector is defined as . This reduced-order representation captures the main dynamics relevant to the hovering task while neglecting the lateral states, which are independently stabilized by the roll-yaw control loop described earlier.

The state-space model is represented as follows:

where and are the system and input matrices obtained by linearizing the nonlinear ST-VTOL UAV dynamics near the hovering equilibrium point. The control input vector .

The disturbance term is defined as , where represents the concentrated disturbance acting on the pitch acceleration , and represents the concentrated disturbance acting on the vertical acceleration , as shown in Equation (9). In practice, and are time-varying and difficult to model explicitly. Therefore, an observer-based approach is necessary to estimate these disturbances in real-time and provide the necessary compensation in the control loop.

Based on this reconstructed model, the altitude and pitch controllers can be reformulated using a unified state-space representation, which facilitates the design of the robust disturbance rejection control law presented in the following sections.

3.3.2. State Observation and Disturbance Estimation

To enhance the disturbance rejection capability of the controller, the total disturbance is modeled as an extended state . The complete observer state is thus defined as , where , , and . The corresponding extended system derived from (16) is given by:

where represents the unknown but bounded disturbance vector, which is continuously differentiable in this context. The derivative matrix , , from and are as follows:

Based on Equation (17), this paper designs an SCFO. Unlike traditional ESOs, which directly enhance disturbances by adding states, SCFO adds to , and introduces a first-order integral in to follow the slowly varying/curvature of the unknown perturbation. The SCFO dynamic process is represented as follows:

where is the estimated value of . The error vector is defined as , in which . are the coefficients of the compensation function. Also, the observer gains .

Stability Analysis of the SCFO. The stability analysis proceeds by first establishing the uniform exponential stability of the nominal error dynamics, and then analysing the effect of perturbations.

The complete error vector is defined as:

The estimation error of the disturbance output is:

Subtracting the SCFO equations from the extended system yields:

which can be written in a compact LTV form as:

where , and:

The closed-loop matrix is:

which gives:

Next, we need to make several key assumptions:

Assumption 1.

(Bounded matrices) and are uniformly bounded: for all , ,.

Assumption 2.

(Uniform complete observability) The pair is uniformly completely observable.

For the ST-VTOL UAV model under consideration, the state matrices vary primarily with the flight speed and the angle of attack, both of which are physical quantities with bounded rates of change. Under these conditions, and given that the system is physically observable throughout all expected flight regimes, Assumption 2 is considered to hold. The gain matrices and are chosen to be sufficiently large so as to satisfy the observability Gramian condition over a finite interval.

Lemma 1.

If is uniformly completely observable, its dual is uniformly completely controllable. Hence, there exists a constant gain such that is uniformly exponentially stable [42].

Therefore, according to Lemma 1, we can choose constant gain matrices , , , and (which define the block structure of ) such that is uniformly exponentially stable.

Assumption 3.

(Bounded disturbance derivative) For all , the disturbance rate satisfies .

Under Assumptions 1–3, with the gains chosen as above, system (23) is input-to-state stable (ISS) and is uniformly ultimately bounded.

Consider the nominal case :

From Assumption 2 and Lemma 1, the matrix is uniformly exponentially stable.

Lemma 2.

A time-varying system is uniformly exponentially stable if and only if there exists a continuously differentiable symmetric matrix and constants such that and [43].

Although an explicit form of may not be readily available, Lemma 2 guarantees the existence of such a function, which is sufficient for the analysis. Accordingly, there exists a time-varying Lyapunov function:

satisfying:

Now consider the perturbed system with . Differentiating along trajectories of (23) yields:

By inequality (29) and applying the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, we obtain:

Since and , defining gives:

Lemma 3.

If there exists a Lyapunov function such that

then the system is uniformly ultimately bounded [43].

The inequality (32) satisfies the conditions for ISS. According to Lemma 3, system (23) is ISS, which implies uniform ultimate boundedness (UUB). Therefore, there exist constants and a class- function such that:

Since , , and are contained in and are constant, in (21) is also uniformly ultimately bounded. Therefore, under the given assumptions, the SCFO guarantees exponential convergence of in the nominal case () and uniform ultimate boundedness of both and the disturbance estimation error under bounded disturbance derivatives.

3.3.3. Equivalent Sliding Mode Controller Design

During the controller design, the improved SCFO is assumed to provide accurate estimates of the system states and disturbances, i.e., . Under this assumption, the ESMC law can be constructed by combining three mechanisms: equivalent dynamics cancellation, nonlinear switching, and disturbance compensation.

The sliding surface is designed as:

where is a user-defined weighting matrix and denotes the state tracking error. The matrix determines how each component of the error contributes to the sliding surface, and must satisfy that is nonsingular. This full-rank condition guarantees the existence of an equivalent control input. For the hovering control objective, the reference trajectory is constant, i.e., .

The time derivative of the sliding surface can be derived from the state-space dynamics as:

where . Once the sliding condition is satisfied, the system motion is constrained to the sliding manifold . On this manifold, the equivalent control is obtained by enforcing , leading to:

The equivalent control thus cancels the nominal system dynamics along the sliding surface, ensuring that the closed-loop trajectories remain confined to the manifold under ideal conditions.

To guarantee convergence toward the sliding manifold in the presence of uncertainties, a nonlinear switching term is introduced:

where is the switching gain matrix and is a small smoothing factor used to mitigate chattering. The function serves as a continuous approximation of the discontinuous function, ensuring smooth control behavior near the sliding surface. A sufficiently large is required to compensate for model uncertainties and external disturbances.

To further reduce the dependence on large switching gains, disturbance compensation is introduced based on the SCFO estimation:

where is the disturbance estimate provided by the observer.

Incorporating this compensation term effectively suppresses residual oscillations and improves steady-state accuracy. Consequently, the final control law of the ESMC is expressed as:

Stability Analysis of the ESMC. The stability of the composite system SSMC is analyzed. The analysis builds upon the established performance of the SCFO, which is formalized in the following assumption:

Assumption 4.

(Observer Performance) The SCFO guarantees that the state and disturbance estimation errors are uniformly ultimately bounded. Specifically, from the ISS result of the SCFO in (33), there exists a constant and a finite time such that the residual disturbance estimation error satisfies:

Consider the Lyapunov function candidate:

Differentiating along the trajectories of the system and substituting the control law (39) yields the sliding dynamics:

The derivative of the Lyapunov function is:

Applying the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality and the bound from Assumption 4:

Lemma 4.

The system is ISS if there exists a class function and a class function γ such that:

From inequality (44), we observe that satisfies the conditions for ISS. Therefore, the sliding mode dynamics are ISS with respect to the disturbance estimation error .

The composite observer–controller system can be viewed as a feedback interconnection:

Let be the ISS gain of the SCFO from to , and let be the ISS gain of the ESMC from to , which in turn affects the SCFO through the system dynamics. Furthermore, with the SCFO gains chosen sufficiently large to ensure a small disturbance estimation error bound , the overall system is uniformly ultimately bounded.

Under Assumptions 1–4, the ESMC ensures that the sliding variable converges to a residual set around the origin. Specifically, there exists a finite time and a constant such that:

where the ultimate bound is given by:

Proof.

Corollary 1.

In the ideal situation where the disturbance estimation is perfect () and the smoothing factor is removed (), the sliding variable converges asymptotically to the origin. Specifically, the closed-loop system satisfies

and the control law in (39) guarantees perfect tracking performance.

Design Guidelines. The stability analysis provides explicit criteria for selecting the ESMC parameters:

- Switching Gain Condition:To ensure robustness, the switching gain must dominate the worst-case disturbance estimation error, i.e.,

- Smoothing Factor: The parameter should be selected as a compromise between chattering suppression (larger ) and steady-state accuracy (smaller ).

- Observer–Controller Co-design: The ultimate accuracy is proportional to both and . Therefore, improving the observer’s estimation quality (reducing ) allows the designer to choose a larger to suppress chattering without degrading the tracking performance.

The complete execution process of the proposed disturbance rejection controller, including lateral stabilization, horizontal position regulation, state observation, and sliding mode compensation, is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Disturbance Rejection Control Process |

|

The control methodology and its implementation framework have now been fully established. Based on this, the following section evaluates the proposed design through simulation and flight experiments.

4. Simulation and Experiment

Simulation and experimental tests were conducted on an ST-VTOL UAV to verify the practicality and effectiveness of the method proposed in Section 3. Flight tests were conducted in a controllable wind matrix environment based on the determined system parameters.

4.1. Experimental Platform

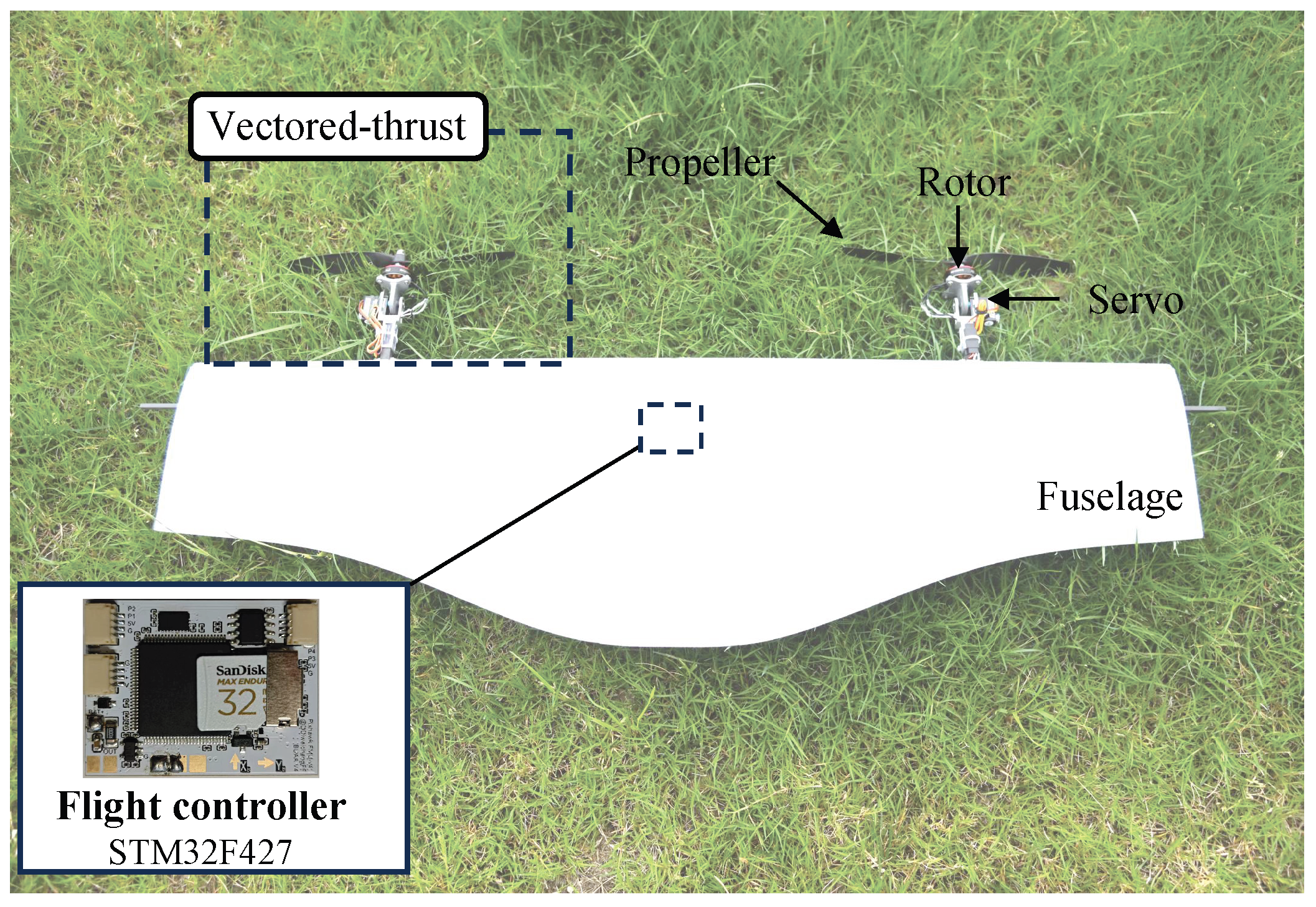

The physical model of the flight platform used in the experiment is shown in Figure 4. The ST-VTOL UAV has a total weight of 0.359 kg. The propulsion system consists of two rotors rated at 8 V, equipped with 8-inch propellers. Powered by lithium batteries, it provides stable energy for hovering and maneuvering. The rigid-body dynamics are characterized by the moments of inertia:

which were measured and used in the simulation model and control-law design.

Figure 4.

Physical prototype of ST-VTOL UAV. Detailed composition and definition can be found in previous work [38,44].

The autopilot system was developed based on the PX4 protocol and integrated multiple sensing and control units. Specifically, it includes a flight controller, an inertial measurement unit (IMU), a global navigation satellite system (GNSS) receiver, a compass, a data logger, and status indicators. These modules were installed on the ST-VTOL UAV to provide real-time state feedback, navigation, flight data logging, and safety monitoring during experiments. All components were fully integrated into the airframe to support seamless transitions between simulation and flight validation. This combined hardware and software setup formed the basis for subsequent experimental verification in controlled wind-field conditions.

4.2. Simulation Results

The tracking position target was a sine signal, and the initial 6-DOF state was configured as:

indicating that the ST-VTOL UAV started from the origin in a stationary vertical position with an upright pitch attitude, zero yaw and roll angles, and zero initial velocities and angular rates.

The parameter settings used in the simulation are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Simulation, observer, and controller parameters.

To emulate realistic atmospheric turbulence acting on the pitch and vertical channels, a Dryden-like disturbance model was employed. The instantaneous disturbance components are defined as:

where and denote the stochastic turbulence acting on the pitch-rate and vertical-velocity channels, respectively. Each component is generated through a first-order shaping filter that approximates the Dryden spectral characteristics:

where and m are the turbulence scale lengths associated with the pitch-rate and vertical channels, and are the corresponding turbulence intensities, and and are independent zero-mean unit Gaussian white-noise processes. This formulation produces exponentially correlated stochastic disturbances that preserve the main spectral properties of the Dryden model while ensuring computational efficiency for real-time simulation. The specific values are shown in Table 1. Since the Dryden model simulates continuous airflow fluctuations in a real environment, which is a continuous field disturbance, this paper does not explicitly define the time when the disturbance occurs. The perturbation curve is represented as .

Comparative simulations were conducted under three observer configurations: the proposed SCFO, the conventional LESO, and LESO enhanced by the fal nonlinear function (LESOF). All observers were embedded within the same cascaded controller architecture to ensure a fair comparison. LESOF replaced the linear proportional term in LESO with the nonlinear function:

where controls the nonlinearity and defines a threshold region. This modification adaptively scales the observer gain, accelerates convergence for small errors, and prevents instability for large errors.

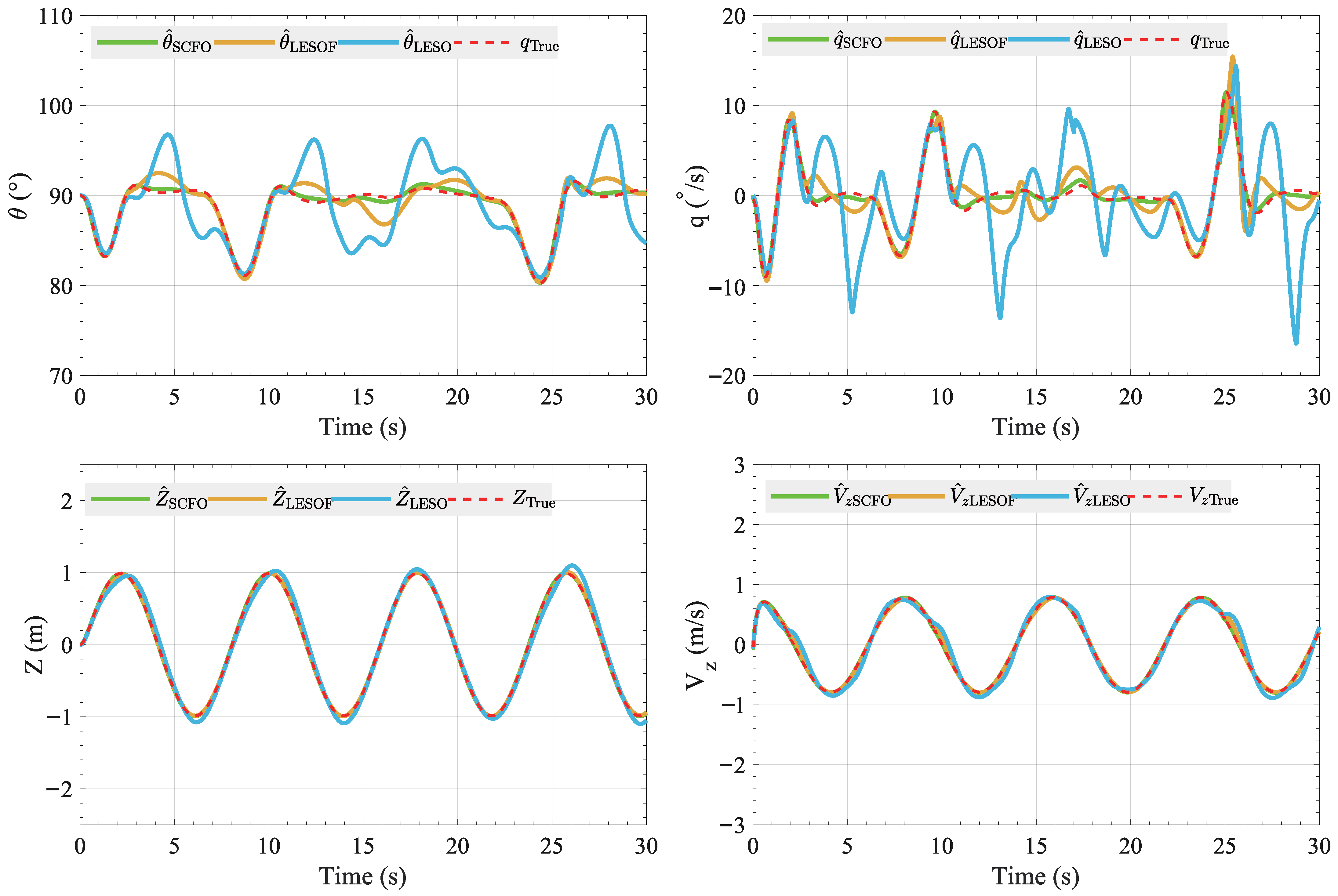

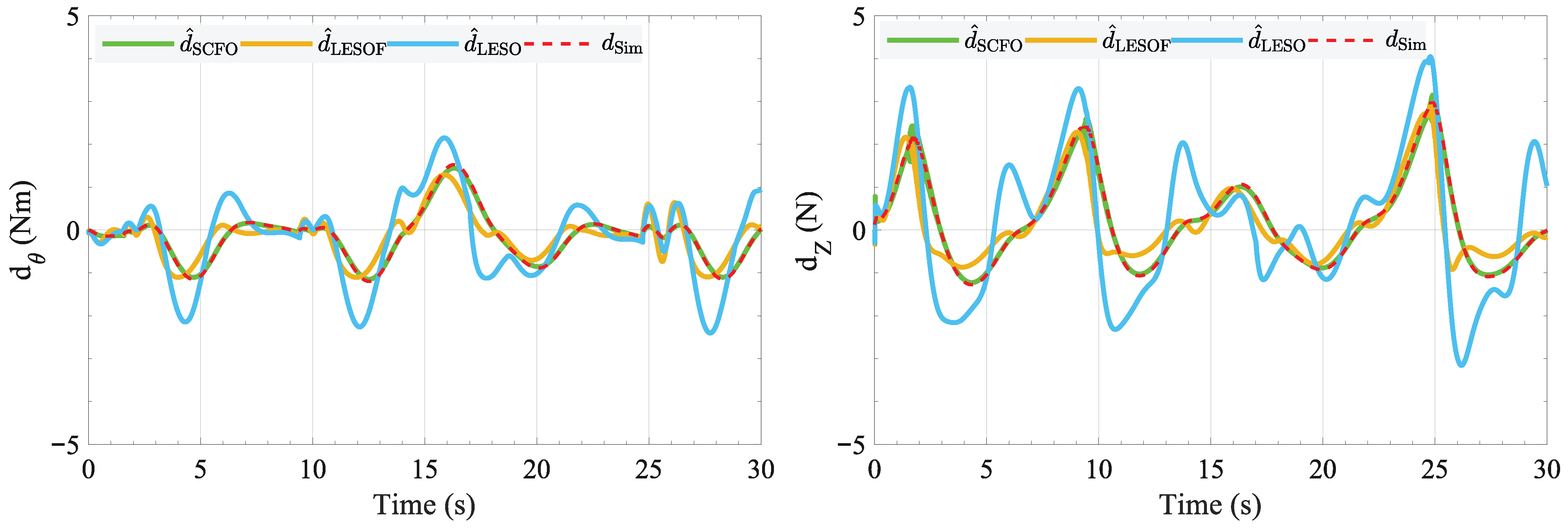

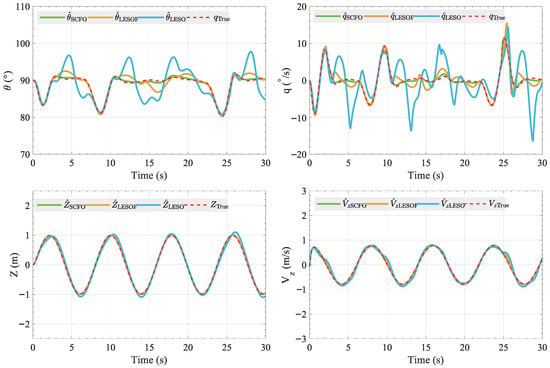

As shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6, the system states and disturbance estimates obtained by the SCFO, LESOF, and LESO are compared. It can be observed that the SCFO exhibits almost perfect overlap with the true system states, whereas the LESO produces noticeable tracking deviations. The corresponding root-mean-square error (RMSE) results are summarized in Table 2, showing that the SCFO consistently achieves the lowest tracking errors, with pitch-angle and altitude RMSE values of and m, respectively. In contrast, the LESO shows larger discrepancies under disturbances, reaching RMSE values of and m for pitch angle and altitude. The LESOF partially mitigates this deviation through nonlinear gain adaptation, reducing the errors to and m, though its estimation accuracy still remains inferior to that of the SCFO. Furthermore, based on Figure 6, a sliding-window RMSE was computed to evaluate the convergence behaviour of each observer. The results indicate that the SCFO achieves the fastest convergence and the most stable estimation performance, with the moving-average RMSE of the observed disturbances being for and for .

Figure 5.

Comparison between the simulated true states and the system states estimated by SCFO, LESOF, and LESO.

Figure 6.

Comparison between the simulated true disturbances and the disturbances estimated by SCFO, LESOF, and LESO.

Table 2.

Comparison of the state estimation errors and sliding RMSE for SCFO, LESOF, and LESO.

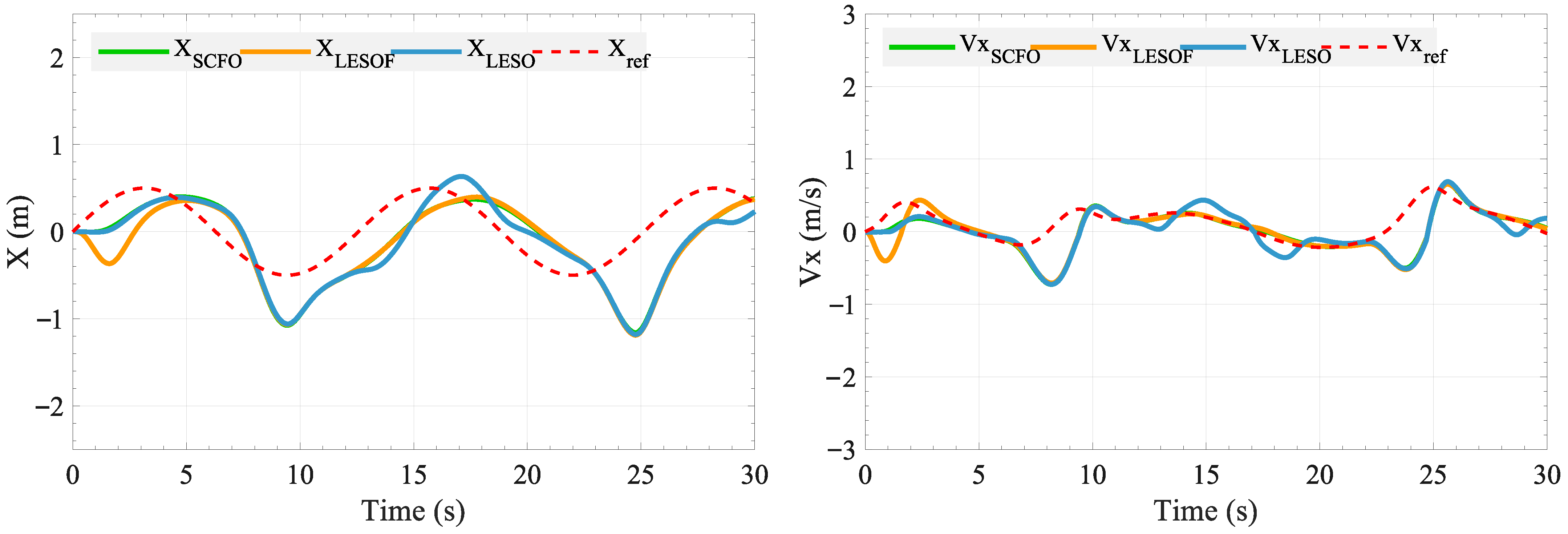

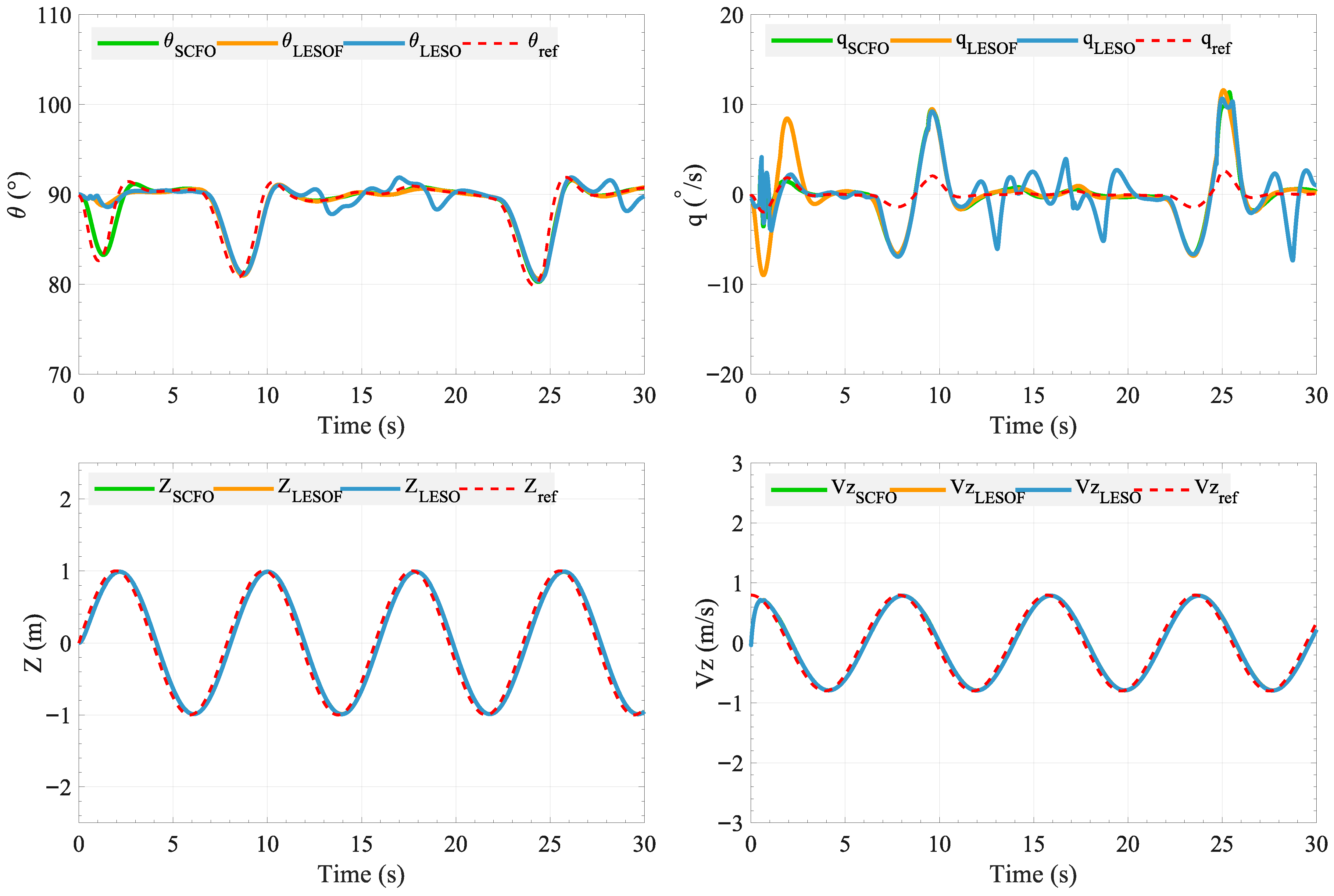

The control performance is illustrated in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9. We can see from Figure 7 that, in all tested controllers using different observers, the X-position tracking exhibits a certain degree of delay, which can be attributed to the cascaded formulation in Equation (15), where is generated indirectly from both position and velocity errors. This structure inevitably introduces phase lag when compensating for external disturbances. Moreover, the pitch rate q in Figure 8 shows larger amplitudes than its reference, which is likely caused by the ESMC in Equation (37) requiring a sufficiently large switching gain to ensure robustness. The additional gain magnifies transient responses, leading to overshoot in the actual q trajectory.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the horizontal position and velocity tracking performance achieved by SCFO, LESOF, and LESO.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the pitch angle and angular velocity, altitude and vertical velocity tracking performance achieved by SCFO, LESOF, and LESO. The tracking performances of Z and are very similar, so the green and orange curves are not clearly visible, although they are indeed present.

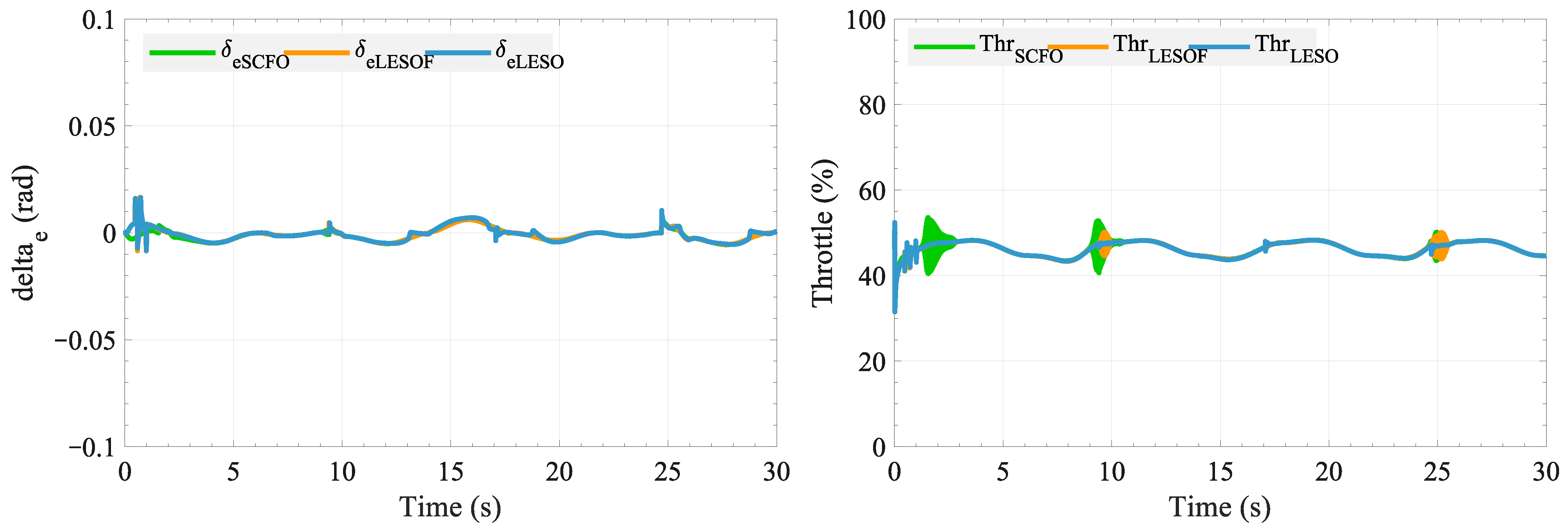

Figure 9.

Control outputs based on SCFO, LESOF, and LESO, including the vectored thrust deflection angle and the throttle percentage.

Despite these common limitations, differences among the controllers can still be observed. As shown in Table 3, the SCFO-based control yields smoother responses in X, , , and q with smaller oscillation amplitudes, and achieves the smallest RMSE values of 0.4002, 0.2562, 0.0325, and 0.0408, respectively, indicating that its disturbance estimation and compensation are more effective. As altitude control is relatively less challenging, all three observers demonstrate comparable and satisfactory estimation performance in Z and . However, the data still show that SCFO achieves the lowest RMSE, with values of 0.1119 and 0.1008, respectively. This confirms that LESO struggles under strong disturbances, while LESOF improves but falls short of SCFO.

Table 3.

Comparison of the state tracking errors of controllers based on SCFO, LESOF, and LESO.

4.3. Experimental Results

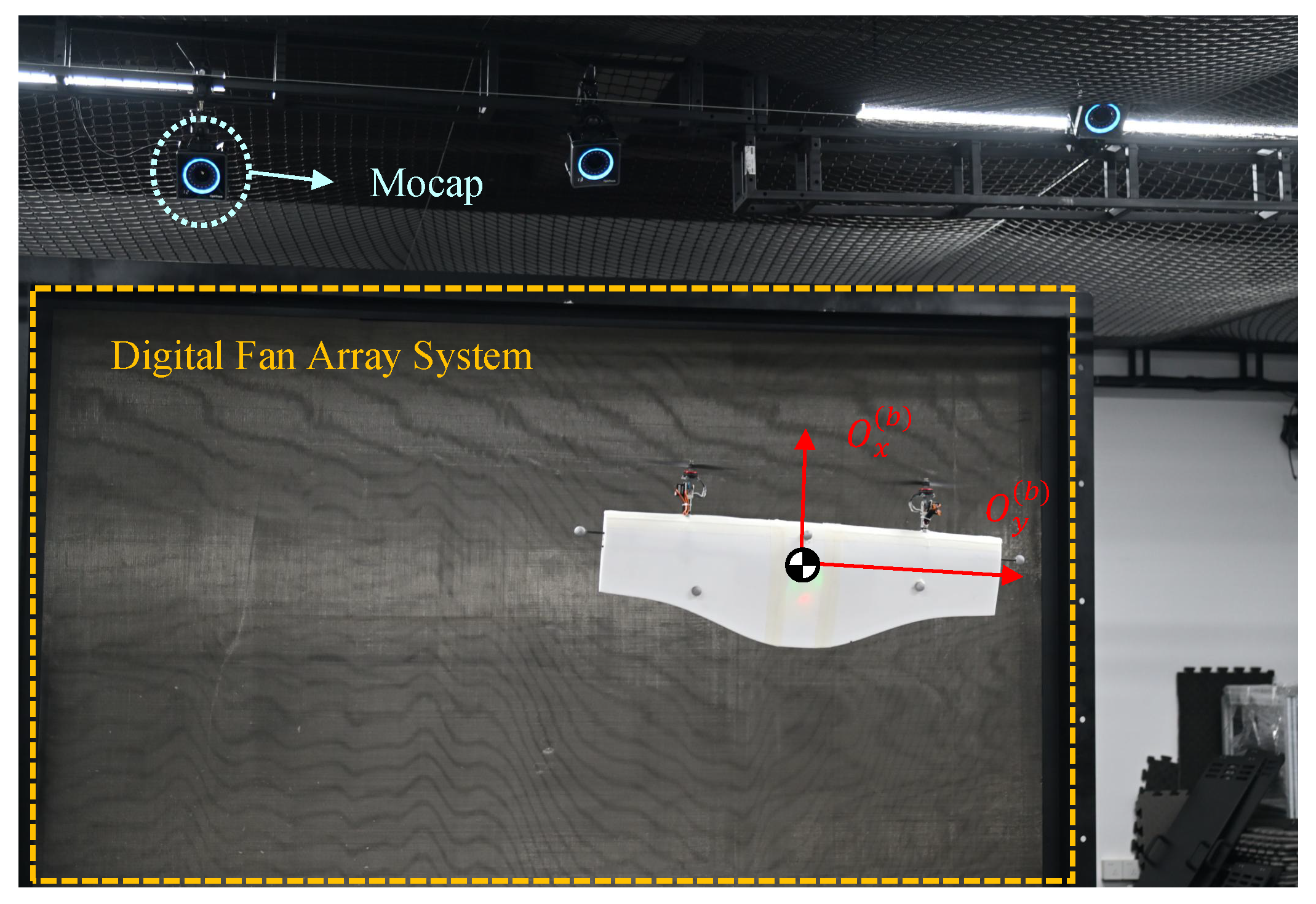

To validate the practicality and effectiveness of the method SSMC, experimental verification was conducted using an FAWG. The FAWG is an open and modular wind tunnel test system composed of stackable fan modules, each containing a grid of fan units. The system supports precise control through dedicated software and APIs, allowing time-varying wind speed configurations, including sinusoidal variations, layered wind changes, and simulated turbulence conditions. In our implementation, the control frequency was set to 10 Hz, and the wind profile was generated through a custom function to simulate dynamic disturbance patterns. Indoor tests with position feedback were conducted using a motion capture system from YMATE (Beijing, China; model KB-0/CL-22), providing millimeter-level precision at high update rates, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Indoor experimental site.

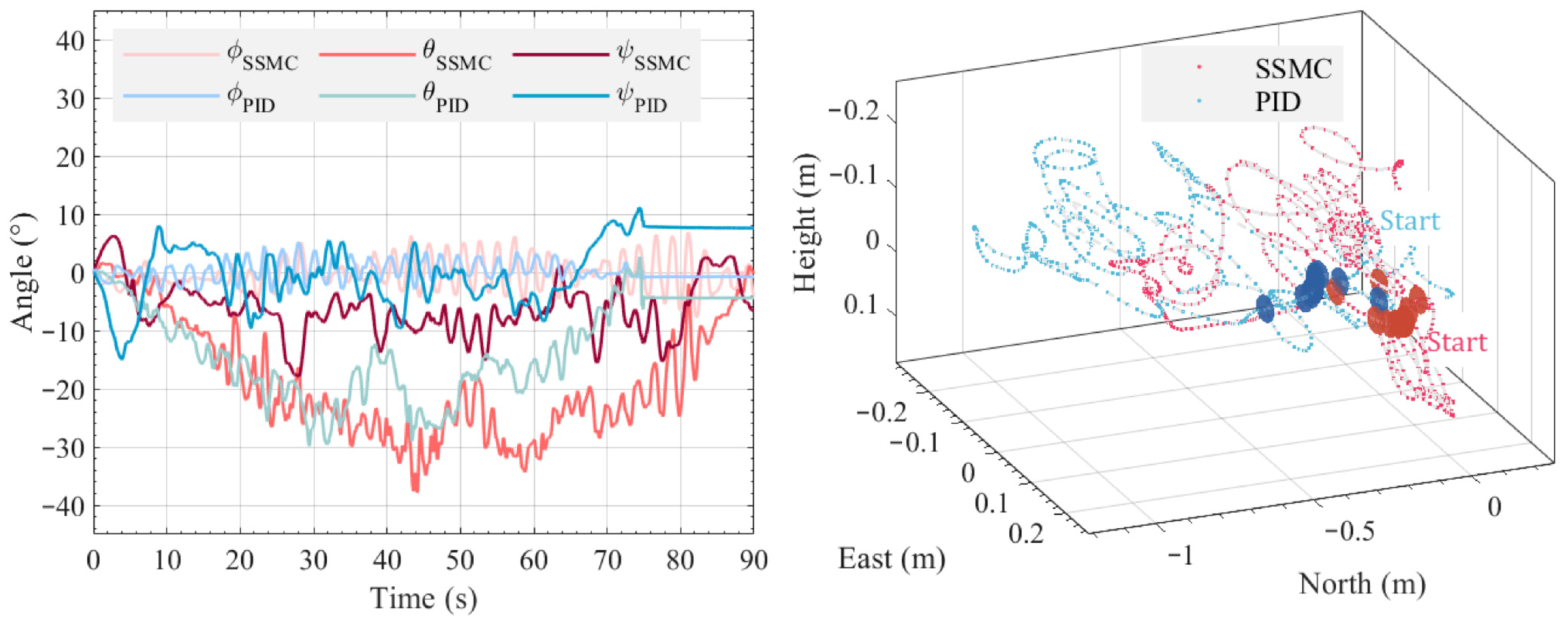

A custom wind speed profile was defined to introduce disturbances in a repeatable and structured manner. The wind speed gradually increased from 0 m/s to 6 m/s and then decreased to 0 m/s over 90 s. The spatial distribution of wind velocity in the longitudinal plane followed a sinusoidal profile, while the temporal variation was layered to replicate fluctuating wind fields.

SSMC was compared with a conventional PID controller, and the corresponding experimental results are shown in Figure 11. The analysis can be divided into three parts. First, in the attitude angle responses, SSMC achieved more stable pitch and altitude regulation under fluctuating wind speeds, exhibiting reduced oscillations compared to PID. The PID-controlled ST-VTOL UAV showed larger deviations when subjected to wind variations, consistent with its higher maximum error of compared to under SSMC. Second, in the trajectory comparison subfigure, red spheres of SSMC and blue spheres of PID denote the real-time positions of the ST-VTOL UAV at identical time instances. The positions under SSMC were more tightly clustered around the hovering target , whereas those under PID spread more widely, indicating larger trajectory deviation. Finally, Table 4 provides a quantitative comparison of tracking errors. The SSMC controller achieved a smaller total error ( vs. ), a lower RMSE ( vs. ), and a reduced maximum deviation ( vs. ). These results demonstrated that SSMC converged faster and stabilized within narrower error bounds, whereas PID suffered from slower convergence and larger steady-state deviations.

Figure 11.

Experimental results: Comparison between the proposed method SSMC and PID, including attitude angles and trajectory tracking.

Table 4.

Comparison of tracking error metrics between SSMC and PID controllers.

Overall, the experimental results consistently demonstrate the superior disturbance rejection ability of the SSMC. The ST-VTOL UAV operating under SSMC maintains a smaller deviation from the target hovering position, effectively counteracting time-varying disturbances introduced by the wind field. In contrast, the PID controller exhibits significant difficulty in achieving comparable precision, resulting in degraded stability and larger residual errors. The results thus confirm that SSMC is effective in real-world scenarios with non-uniform wind disturbances, aligning with the outcomes of the preceding simulation studies.

5. Conclusions

This paper is the first to apply the SSMC method to an ST-VTOL UAV. The goal is to investigate the practicality of this approach for maintaining stability during take-off and landing under wind disturbances. The state observer employed, the SCFO, differs from the traditional LESO in that it explicitly incorporates system derivatives in its formulation. This improvement enhances the accuracy of the state observation, thereby making disturbance estimation more reliable.

Firstly, a complete 6-DOF dynamic model was established, along with a simplified 3-DOF longitudinal model that incorporates disturbance representation. Subsequently, the SCFO was combined with the ESMC to design the SSMC controller. The control variables input to the ST-VTOL UAV include an equivalent control term, a nonlinear switching term, and a disturbance compensation term. A theoretical Lyapunov-based stability analysis shows that the closed-loop error dynamics exhibit asymptotic convergence in the nominal case and remain uniformly ultimately bounded in the presence of bounded disturbance derivatives and estimation residuals. Finally, the proposed SSMC method was validated through both simulations and flight experiments under external disturbances, utilizing an experimental platform comprising a FAWG, an indoor motion-capture testbed, and a lightweight ST-VTOL prototype. Simulation results demonstrated that the SCFO-based control achieved the smallest tracking errors among all observers, with RMSE reductions of up to 65% in pitch angle and 88% in altitude compared to the LESO-based scheme, confirming its superior disturbance estimation and compensation capabilities. Experimental evaluations further revealed that the SSMC reduced the total tracking error by approximately 33%, decreased the RMSE from 0.65 to 0.42, and limited the maximum deviation by 27% compared to the PID controller. These results collectively verify that SSMC ensures faster convergence, smaller steady-state errors, and more stable flight performance under disturbance conditions. This demonstrates the technical advantages of combining a derivative-based observer structure with an SMC law and the practicality of this approach for ST-VTOL UAVs.

Future research will explore integrating of this control approach with an MPC framework, extending the flight mission from fixed-point hovering to trajectory tracking, thereby further improving the engineering applicability of this approach and the ST-VTOL UAV.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z., W.D. and L.Z.; methodology, J.Z., J.X. and D.L.; software, J.Z. and W.D.; validation, J.Z., W.D. and L.Z.; formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, J.Z. and G.Y.; resources, L.Z., J.X. and D.L.; data curation, J.Z. and W.D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z. and G.Y.; writing—review and editing, W.D., L.Z., Z.T., J.X. and D.L.; visualization, J.Z. and W.D.; supervision, W.D. and L.Z.; project administration, J.X. and Z.T.; funding acquisition, D.L. and Z.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by: (1) the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities; (2) Yunnan Science and Technology Projects (grant NO. 202505AT350001). (3) the Reward Funds for Research Project of Tianmushan Laboratory (TK-2024-D-010).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ke, Y.; Wang, K.; Chen, B.M. Design and Implementation of a Hybrid UAV with Model-Based Flight Capabilities. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2018, 23, 1114–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tang, Y.; Ge, Y.; Wu, C.; Tang, H.; Hu, T.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Qu, Q.; et al. Vectored-thrust system design for a tail-sitter micro-aerial-vehicle with belly/back takeoff ability. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 155, 109542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliabue, A.; How, J.P. Airflow-Inertial Odometry for Resilient State Estimation on Multirotors. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 5736–5743. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, N.; Ren, A.Z.; Piqué, A.; Snyder, D.; Barretto, D.; Hultmark, M.; Majumdar, A. FlowDrone: Wind Estimation and Gust Rejection on UAVs Using Fast-Response Hot-Wire Flow Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), London, UK, 29 May–2 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 5393–5399. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Olejnik, D.; Wagter, C.d.; Oudheusden, B.v.; Croon, G.d.; Hamaza, S. Battle the Wind: Improving Flight Stability of a Flapping Wing Micro Air Vehicle Under Wind Disturbance With Onboard Thermistor-Based Airflow Sensing. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 9605–9612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, W.; Dang, S.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Li, D.; Tu, Z. Skin-Like Airflow Odometry for Micro Aerial Vehicles Based on Distributed Thermal Anemometers. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2025; early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalwadi, N.; Deb, D.; Ozana, S. Dual Observer Based Adaptive Controller for Hybrid Drones. Drones 2023, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, C.; Coombes, M.; Yan, Y.; Chen, W.H. Optimal Path Following for Small Fixed-Wing UAVs Under Wind Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2021, 29, 996–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja-Jaimes, V.; Coronel-Escamilla, A.; Escobar-Jiménez, R.F.; Adam-Medina, M.; Guerrero-Ramírez, G.V.; Sánchez-Coronado, E.M.; García-Morales, J. Fractional-Order Sliding Mode Observer for Actuator Fault Estimation in a Quadrotor UAV. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, W.; Suzuki, S. UAV trajectory tracking under wind disturbance based on novel antidisturbance sliding mode control. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 149, 109138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Shen, J. Disturbance Observer and Adaptive Control for Disturbance Rejection of Quadrotor: A Survey. Actuators 2024, 13, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyadat, Z.; Horri, N.; Innocente, M.; Statheros, T. Observer-Based Optimal Control of a Quadplane with Active Wind Disturbance and Actuator Fault Rejection. Sensors 2023, 23, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Wang, Z. A Robust Control for an Aerial Robot Quadrotor under Wind Gusts. J. Robot. 2018, 2018, 5607362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Jia, J.; Yu, X.; Guo, L.; Xie, L. Multiple observers based anti-disturbance control for a quadrotor UAV against payload and wind disturbances. Control Eng. Pract. 2020, 102, 104560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, A.L.; Moghavvemi, M.; Mohamed, H.A.F.; Gaeid, K.S. Modelling and PID controller design for a quadrotor unmanned air vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Automation, Quality and Testing, Robotics (AQTR), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 28–30 May 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, Q.; Du, G.X.; Cai, K.Y. Proportional-Integral Stabilizing Control of a Class of MIMO Systems Subject to Nonparametric Uncertainties by Additive-State-Decomposition Dynamic Inversion Design. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2016, 21, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Huang, K.; Zhang, J. Modelling, Design, and Control of a Central Motor Driving Reconfigurable Quadcopter. Drones 2025, 9, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prach, A.; Kayacan, E. An MPC-based position controller for a tilt-rotor tricopter VTOL UAV. Optim. Control Appl. Methods 2017, 39, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Zhang, W.; Chen, H.; Shi, J. Robust control strategy for multi-UAVs system using MPC combined with Kalman-consensus filter and disturbance observer. ISA Trans. 2023, 135, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, K.; Asadi, D.; Nabavi-Chashmi, S.Y.; Tutsoy, O. Modified adaptive discrete-time incremental nonlinear dynamic inversion control for quad-rotors in the presence of motor faults. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 188, 109989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherinezhad, M.; Ramirez-Serrano, A.; Abedini, A. Robust Trajectory-Tracking for a Bi-Copter Drone Using INDI: A Gain Tuning Multi-Objective Approach. Robotics 2022, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osler, S.; Sands, T. Controlling Remotely Operated Vehicles with Deterministic Artificial Intelligence. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Namiki, A.; Asignacion, A.; Li, Z.; Suzuki, S. Chattering Reduction of Sliding Mode Control for Quadrotor UAVs Based on Reinforcement Learning. Drones 2023, 7, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Ozguner, U. Sliding Mode Control of a Quadrotor Helicopter. In Proceedings of the 45th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, San Diego, CA, USA, 13–15 December 2006; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, C.; Spurgeon, S.K.; Patton, R.J. Sliding mode observers for fault detection and isolation. Automatica 2000, 36, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Alattas, K.A.; Bouteraa, Y.; Mofid, O.; Mobayen, S. Adaptive finite-time backstepping control tracker for quadrotor UAV with model uncertainty and external disturbance. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 133, 108088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Fan, T.; Xu, M.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, F. Adaptive fractional order non-singular terminal sliding mode anti-disturbance control for advanced layout carrier-based UAV. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 139, 108367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, A.; Jafari, H.; Mansouri, S.S.; Nikolakopoulos, G. External force estimation and disturbance rejection for Micro Aerial Vehicles. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 200, 116883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Pan, J.; Chen, G.; Zhang, X.; Ding, F. Sliding Mode Dual-Channel Disturbance Rejection Attitude Control for a Quadrotor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 10489–10499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shao, X.; Xu, L.; Jia, R. Finite-Time Attitude Control With Chattering Suppression for Quadrotors Based on High-Order Extended State Observer. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 159724–159733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Li, X.; Chen, Z. Problems of Extended State Observer and Proposal of Compensation Function Observer for Unknown Model and Application in UAV. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 52, 2899–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Ramirez, F.; Polyakov, A.; Efimov, D.; Perruquetti, W. Finite-time and fixed-time observer design: Implicit Lyapunov function approach. Automatica 2018, 87, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, A. Nonlinear Feedback Design for Fixed-Time Stabilization of Linear Control Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2012, 57, 2106–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, P.; Khorrami, F.; Krstic, M. A dynamic high-gain design for prescribed-time regulation of nonlinear systems. Automatica 2020, 115, 108860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.K.; Zhou, B.; Duan, G.R. Global prescribed-time output feedback control of a class of uncertain nonlinear systems by linear time-varying feedback. Automatica 2024, 165, 111680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, B.L.; Lewis, F.L.; Johnson, E.N. Aircraft Control and Simulation: Dynamics, Controls Design, and Autonomous Systems; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, R.C. Flight Stability and Automatic Control; WCB/McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Di, W.; Wei, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, J.; Li, D.; Tu, Z. Dynamics and control of tailless vectored-thrust VTOL in hover-to-forward transition. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 164, 110385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.V. Flight Dynamics Principles: A Linear Systems Approach to Aircraft Stability and Control; Butterworth-Heinemann: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Wei, H.; Quan, Q. Heading Adjustment by Admittance Control for Lifting-Wing Quadcopters in Strong Winds. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 3558–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichwanul Hakim, T.M.; Arifianto, O. Implementation of Dryden Continuous Turbulence Model into Simulink for LSA-02 Flight Test Simulation. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1005, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, S. Linear system theory and design. Automatica 1986, 22, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H. Nonlinear Systems, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Di, W.; Dong, X.; Wei, Z.; Liu, H.; Tu, Z.; Li, D.; Xiang, J. Towards Efficiency and Endurance: Energy–Aerodynamic Co-Optimization for Solar-Powered Micro Air Vehicles. Drones 2025, 9, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).