Influence of Organic and Inorganic Compositions on the Porosity of the Deep Qiongzhusi Shales on the Margin of the Deyang–Anyue Aulacogen, Sichuan Basin: Implications from the Shale Samples of Well Z204

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological Background

3. Samples and Experiments

3.1. Samples

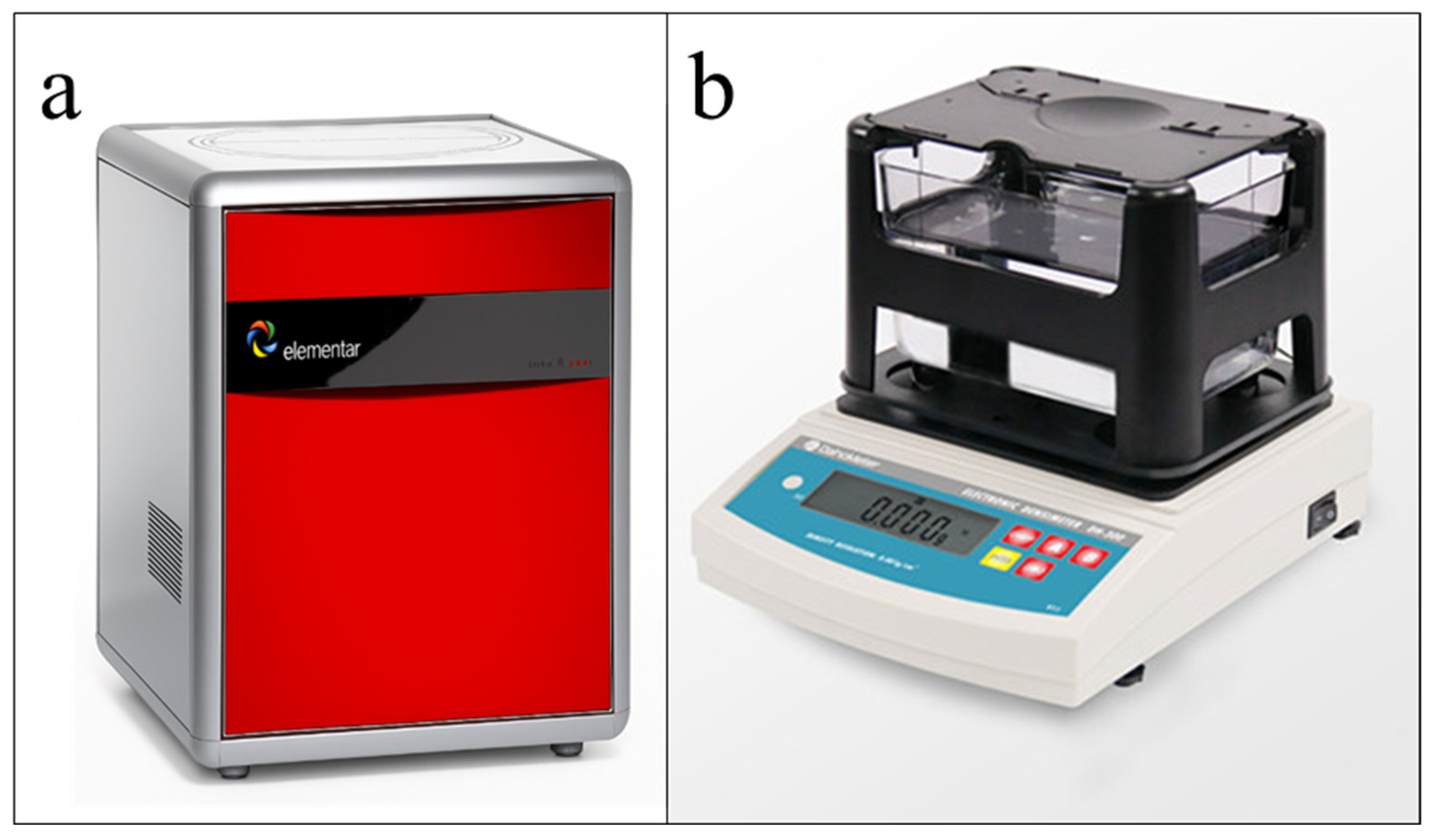

3.2. TOC and Mineral Composition Analysis

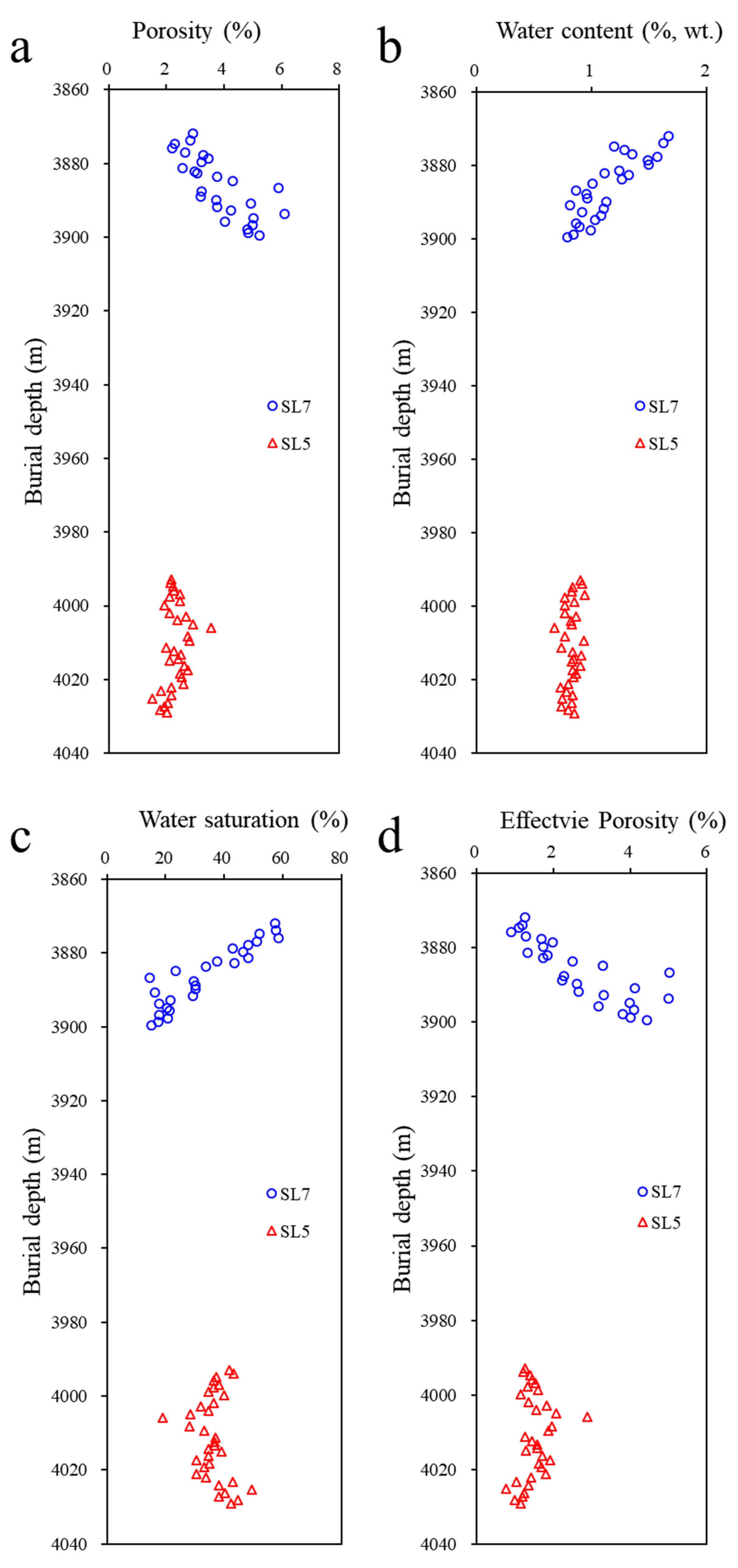

3.3. Water Content and Water Saturation

3.4. Porosity and Effective Porosity

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. TOC Content of the Deep QZS Shales

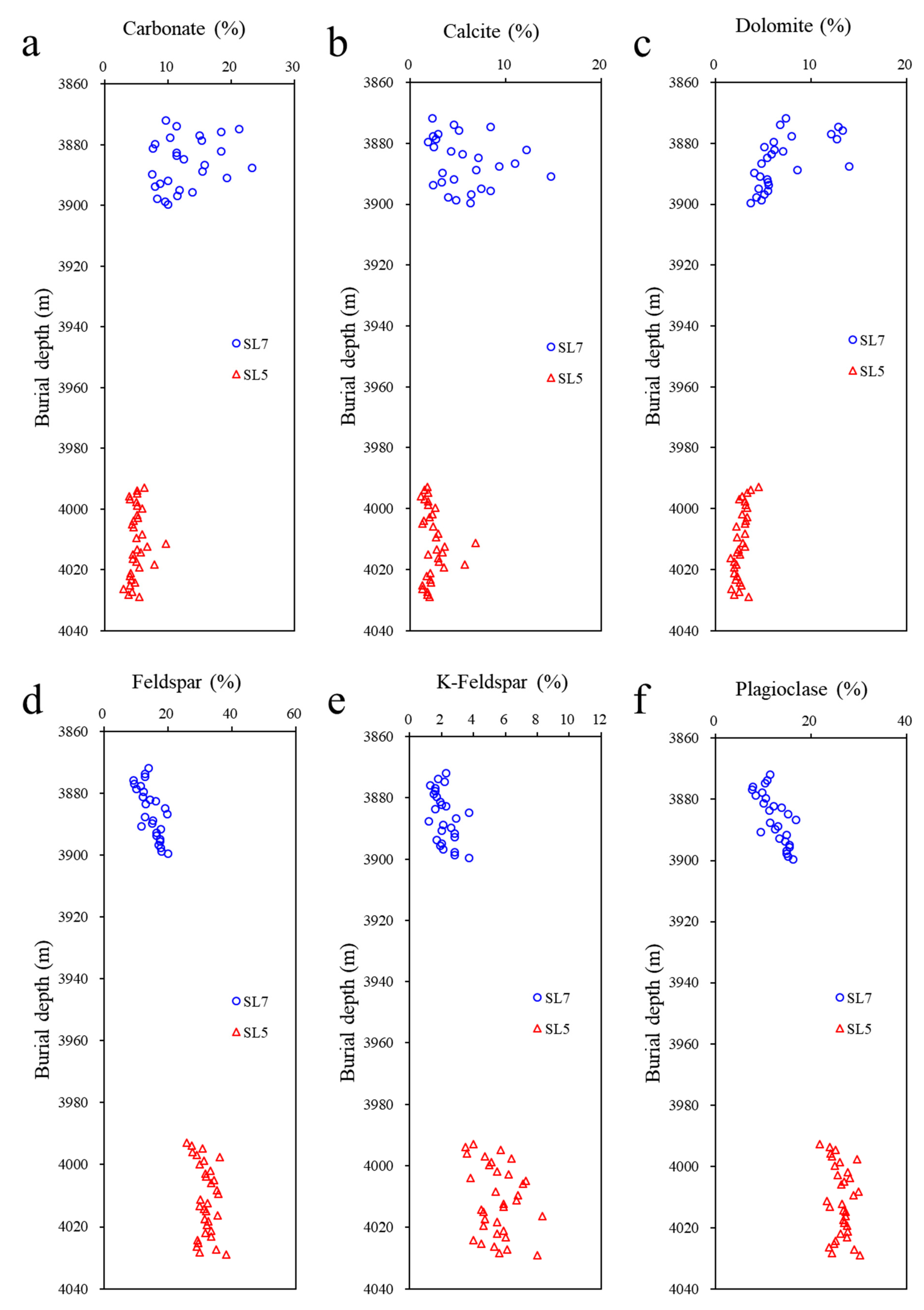

4.2. Mineralogical Compositions of the Deep QZS Shales

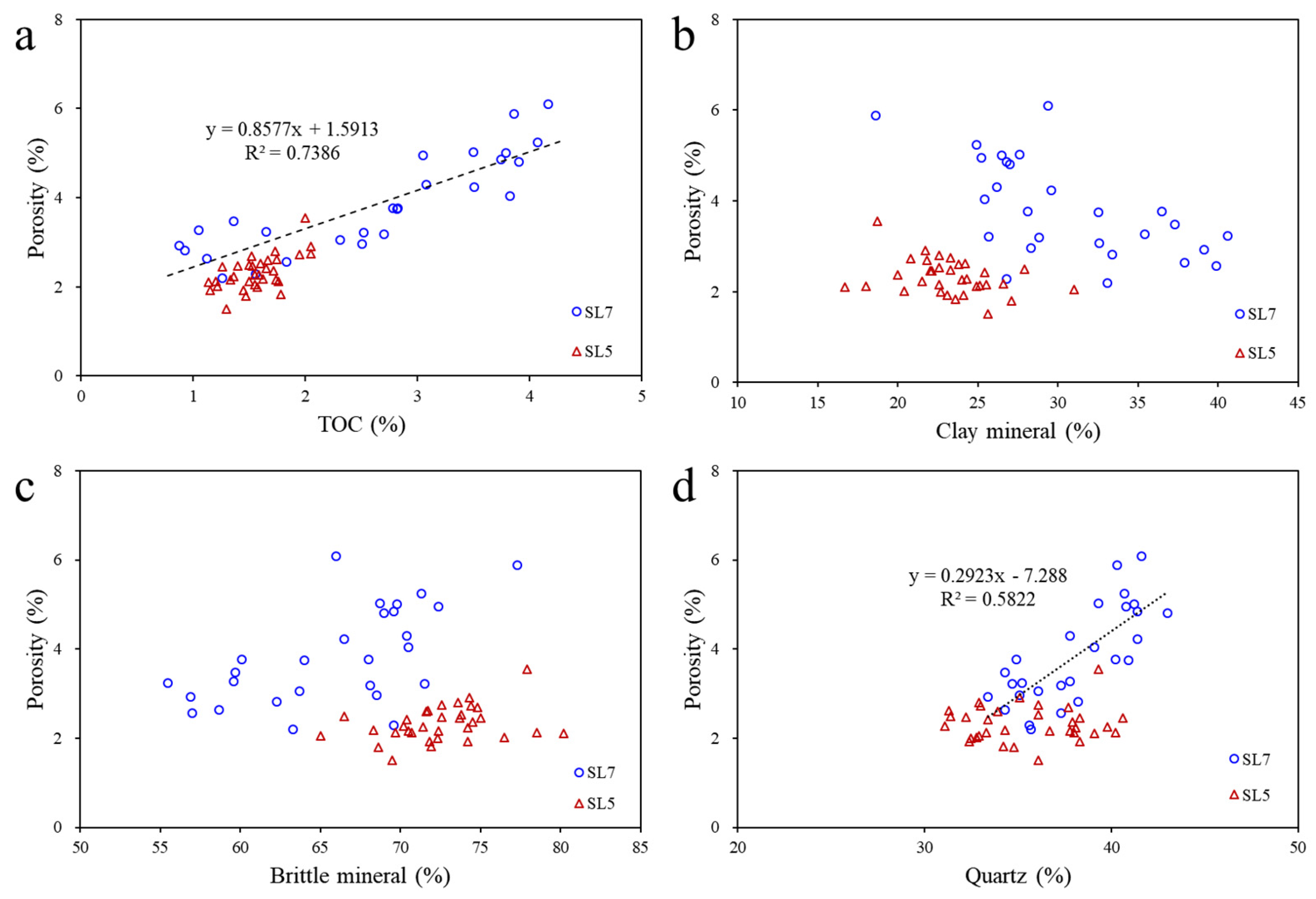

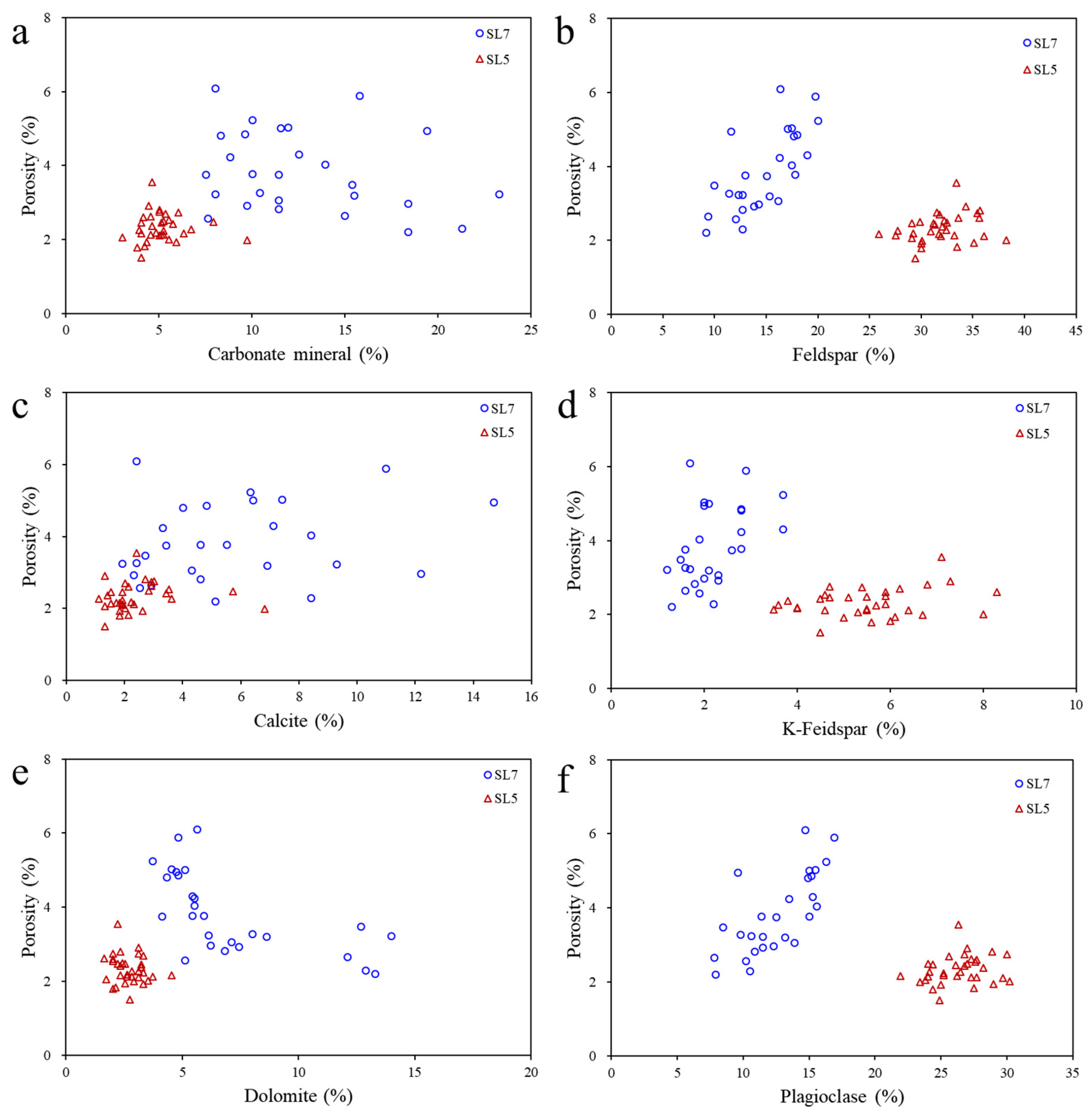

4.3. Porosity of Shales and Its Controlling Factors

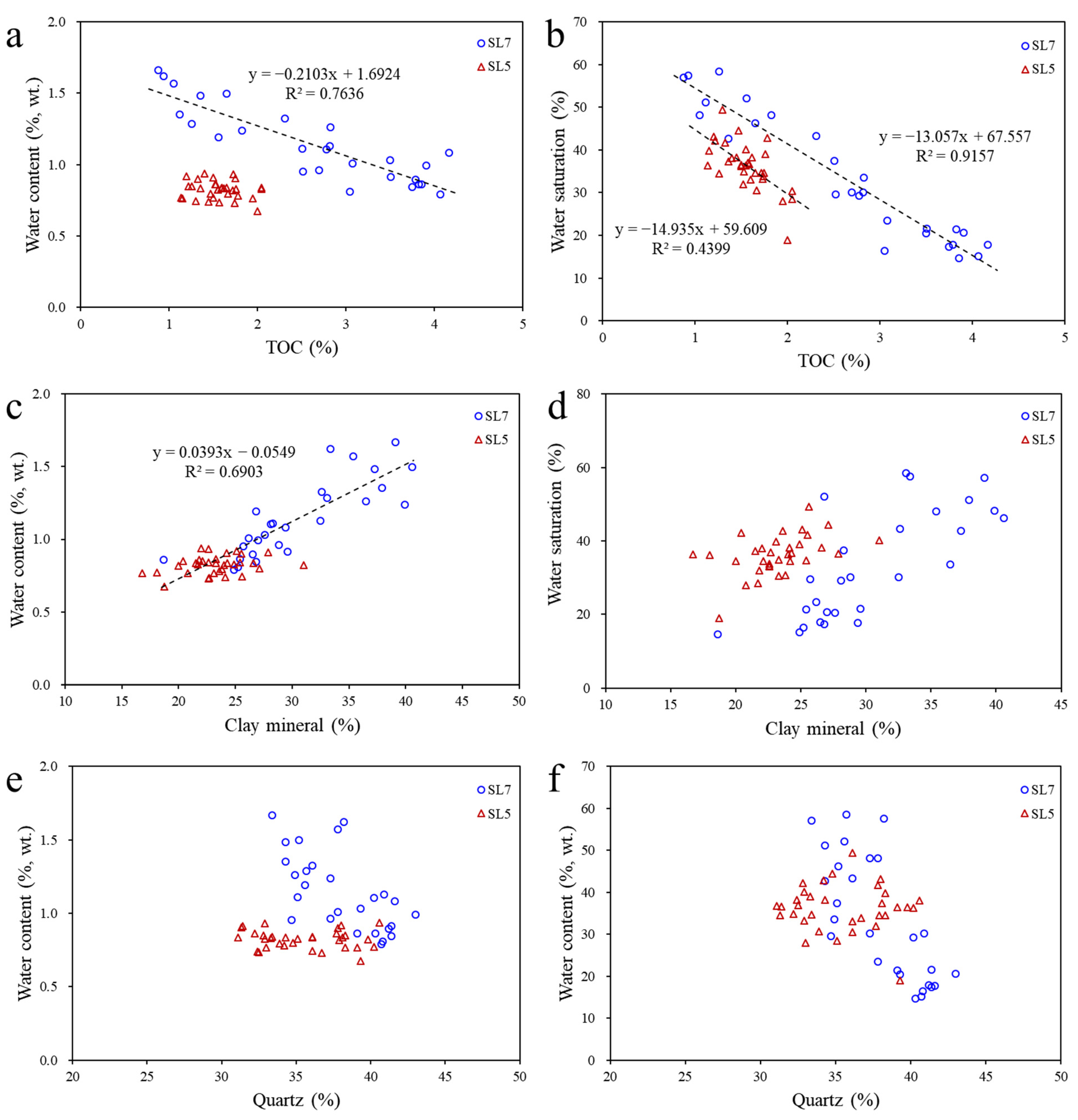

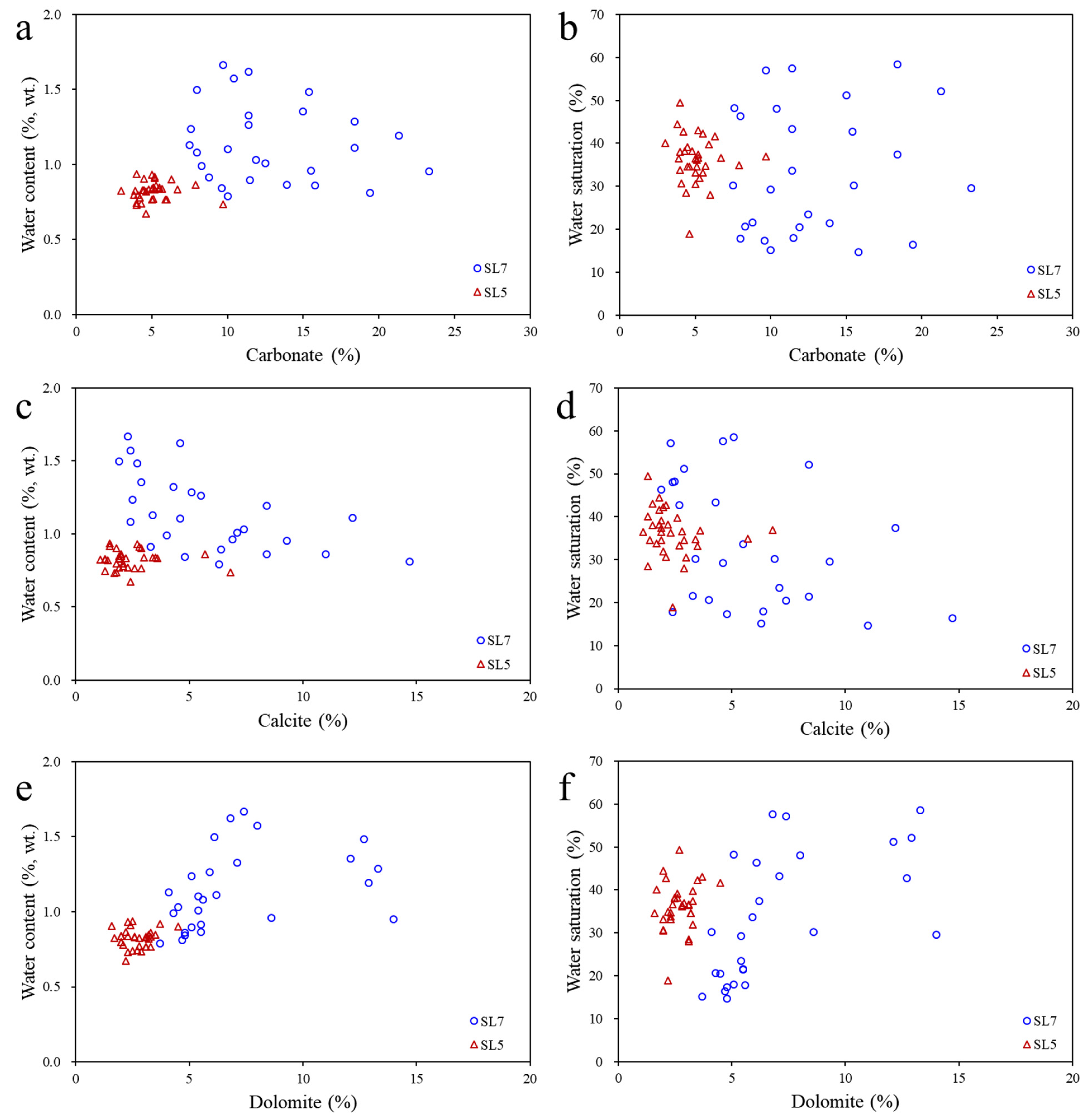

4.4. Water-Bearing Characteristics of Shale and Its Controlling Factors

4.5. Effective Porosity of Shale and Its Main Controlling Factors

4.6. Geological Significance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hao, F.; Zou, H.Y.; Lu, Y.C. Mechanisms of shale gas storage: Implications for shale gas exploration in China. Aapg Bull. 2013, 97, 1325–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.N.; Zhu, R.K.; Chen, Z.Q.; Ogg, J.G.; Wu, S.T.; Dong, D.Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, Y.M.; Wang, L.; Lin, S.H.; et al. Organic-matter-rich shales of China. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 189, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.Z.; Li, J.Z.; Yang, T.; Wang, S.F.; Huang, J.L. Geological difference and its significance of marine shale gases in South China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2016, 43, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, S.X.; Shi, Z.S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, T.Q.; Wang, Y.M.; Cui, H.Y.; Chen, H.R.; Wang, Y. Genesis Mechanism of Low Resistivity in the Lower Cambrian Qiongzhusi Formation Shale and Its Response Characteristics to Pore Structure—Take the Z201 Well as an Example. Acs Omega 2025, 10, 43995–44011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.L.; Deng, H.C.; Zhao, S.; Wei, L.M.; He, J.H. Formation mechanisms and exploration breakthroughs of new type of shale gas in Cambrian Qiongzhusi Formation, Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Gao, P.; Xiao, X.M.; Lu, C.G.; Feng, Y. Lower Cambrian Organic-Rich Shales in Southern China: A Review of Gas-Bearing Property, Pore Structure, and Their Controlling Factors. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 9745313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.L.; Zou, C.N.; Li, J.Z.; Dong, D.Z.; Wang, S.I.; Wang, S.Q.; Cheng, K.M. Shale gas generation and potential of the Lower Cambrian Qiongzhusi Formation in the Southern Sichuan Basin, China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2012, 39, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.L.; Jiang, Z.X.; Yuan, Z.L.; Jiao, Y.F.; Lin, C.H.; Liu, X.X. Pore Water and Its Multiple Controlling Effects on Natural Gas Enrichment of the Quaternary Shale in Qaidam Basin, China. Energies 2023, 16, 6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.F.; Zhao, Y.P. Characterization of pore structure, gas adsorption, and spontaneous imbibition in shale gas reservoirs. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 159, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Chen, D.X.; Wang, Y.C.; Lei, W.Z.; Wang, F.W. Characteristics and Controlling Factors of Pores in Different Shale Lithofacies Reservoirs of Lower Cambrian Qiongzhusi Formation, Southwestern Sichuan Basin, China. Minerals 2023, 13, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, F.; Devegowda, D. Estimation of adsorbed-phase density of methane in realistic overmature kerogen models using molecular simulations for accurate gas in place calculations. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017, 46, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Xiao, X.M.; Hu, D.F.; Liu, R.B.; Li, F.; Zhou, Q.; Cai, Y.D.; Yuan, T.; Meng, G.M. Gas in place and its controlling factors of deep shale of the Wufeng-Longmaxi Formations in the Dingshan area, Sichuan Basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 17, 322–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.Y.; Liu, C.; Zhu, X.M.; Steel, R.J.; Tian, H.Y.; Wang, K.; Song, Z.P. Experimental Study on the Development Characteristics and Controlling Factors of Microscopic Organic Matter Pore and Fracture System in Shale. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 773960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Xiao, X.M.; Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Wei, Q. Evolution of water content in organic-rich shales with increasing maturity and its controlling factors: Implications from a pyrolysis experiment on a water-saturated shale core sample. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 109, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, R.G.; Reed, R.M.; Ruppel, S.C.; Hammes, U. Spectrum of pore types and networks in mudrocks and a descriptive classification for matrix-related mudrock pores. Aapg Bull. 2012, 96, 1071–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.L.; Wang, M.Z.; Lin, S.B.; Hao, Y.W. Pore characteristics and influencing factors of different types of shales. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 102, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.M.; Zhou, Q.; Cheng, P.; Sun, J.; Liu, D.H.; Tian, H. Thermal maturation as revealed by micro-Raman spectroscopy of mineral-organic aggregation (MOA) in marine shales with high and over maturities. Sci. China-Earth Sci. 2020, 63, 1540–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.E.; Tan, J.Q.; Lyu, Q.; Zhang, Y.L. Evolution of organic pores in Permian low maturity shales from the Dalong Formation in the Sichuan Basin: Insights from a thermal simulation experiment. Gas Sci. Eng. 2024, 121, 205166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Rezaee, R.; Yuan, Y.J.; Liu, K.Q.; Xie, Q.; You, L.J. Distribution of adsorbed water in shale: An experimental study on isolated kerogen and bulk shale samples. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 187, 106858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Gong, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Pore structure and heterogeneity of shale gas reservoirs and its effect on gas storage capacity in the Qiongzhusi Formation. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 101244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, H.K.; Sun, C.X.; Liu, G.X.; Du, W.; He, Z.L. Dissolution pore types of the Wufeng Formation and the Longmaxi Formation in the Sichuan Basin, south China: Implications for shale gas enrichment. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 101, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, Z.L.; Zhang, Y.G.; Bao, H.Y.; Su, K.; Shu, Z.H.; Zhao, C.H.; Wang, R.Y.; Wang, T. Dissolution of marine shales and its influence on reservoir properties in the Jiaoshiba area, Sichuan Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2019, 102, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Pan, L.; Zhang, T.W.; Xiao, X.M.; Meng, Z.P.; Huang, B.J. Pore characterization of organic-rich Lower Cambrian shales in Qiannan Depression of Guizhou Province, Southwestern China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2015, 62, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.N.; Zong, P.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y.Y.; Guo, J.Z.; Wu, H. Quantitative Characterization of Inorganic Pores in Sinian Doushantou Dolomitic Shale Based on FIB-SEM in Western Hubei Province, China. Acs Omega 2024, 9, 8151–8161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.N.; Du, J.H.; Xu, C.C.; Wang, Z.C.; Zhang, B.M.; Wei, G.Q.; Wang, T.S.; Yao, G.S.; Deng, S.H.; Liu, J.L.; et al. Formation, distribution, resource potential, and discovery of Sinian-Cambrian giant gas field, Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2014, 41, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, R.; Shi, X.W.; Luo, C.; Zhong, K.S.; Wu, W.; Zheng, M.J.; Yang, Y.R.; Li, Y.Y.; Xu, L.; Zhu, Y.Q.; et al. Aulacogen-uplift enrichment pattern and exploration prospect of Cambrian Qiongzhusi Formation shale gas in Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 1402–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.F.; Jiang, W.B.; Luo, C.; Lin, M.; Zhong, K.S.; He, Y.F.; Li, Y.Y.; Nie, Y.H.; Ji, L.L.; Cao, G.H. Composition-based methane adsorption models for the Qiongzhusi Formation shale in Deyang-Anyue rift trough of Sichuan Basin, China, and its comparison with the Wufeng-Longmaxi Formation shale. Fuel 2025, 393, 134976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.N.; Yan, J.P.; Liao, M.J.; Qiu, X.X.; Yang, Y.; Guo, W.; Zheng, M.J.; Hu, Q.H. Lithofacies Classification and Sweet Spot Development Model for Marine Shale in the Lower Cambrian Qiongzhusi Formation, Sichuan Basin. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 18802–18820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Xiao, X.M.; Tian, H.; Wang, X. Water Content and Equilibrium Saturation and Their Influencing Factors of the Lower Paleozoic Overmature Organic-Rich Shales in the Upper Yangtze Region of Southern China. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 11452–11466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.X.; Song, H.Q.; Wang, J.L.; Wang, Y.H.; Killough, J. An analytical method for modeling and analysis gas-water relative permeability in nanoscale pores with interfacial effects. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2016, 159, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.W.; Xie, R.H.; Xiao, L.Z.; Wu, B.H.; Xu, C.Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Wang, T.Y. Quantitative characterization of bound and movable fluid microdistribution in porous rocks using nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 107677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, M.J.; Paterson, J.R.; Jacquet, S.M.; Andrew, A.S.; Hall, P.A.; Jago, J.B.; Jagodzinski, E.A.; Preiss, W.; Crowley, J.L.; Birch, S.A.; et al. Early Cambrian chronostratigraphy and geochronology of South Australia. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2018, 185, 498–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.R.; Reza, M.T. Hydrothermal deformation of Marcellus shale: Effects of subcritical water temperature and holding time on shale porosity and surface morphology. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 172, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.A.; Rezaee, R. Porosity and Water Saturation Estimation for Shale Reservoirs: An Example from Goldwyer Formation Shale, Canning Basin, Western Australia. Energies 2020, 13, 6294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.Q.; Zhu, Y.M.; Chen, S.B.; Xue, X.H. Structure and Fractal Characteristics of Nano-Micro Pores in Organic-Rich Qiongzhusi Formation Shales in Eastern Yunnan Province. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 17, 5996–6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.J.; Chen, Y.N.; Tang, T.K.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.Y.; Peng, S.X.; Zhang, J.Z. Multiscale Characterization of Pore Structure and Heterogeneity in Deep Marine Qiongzhusi Shales from Southern Basin, China. Minerals 2025, 15, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Z.X.; Wang, P.F.; Song, Y.; Li, Z.; Tang, X.L.; Li, T.W.; Zhai, G.Y.; Bao, S.J.; Xu, C.L.; et al. Porosity-preserving mechanisms of marine shale in Lower Cambrian of Sichuan Basin, South China. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018, 55, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.J.; Xiao, X.M.; Zhao, Y.M.; Liu, W.; Fan, Q.Z.; Meng, G.M.; Qian, Y.J. Thermodynamic and kinetic behaviors of water vapor adsorption on the lower Cambrian over-mature shale and kerogen. Fuel 2025, 381, 133560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Lei, Q.; Chen, J.B.; Weng, D.W.; Wang, X.M.; Liang, H.B. Gas content prediction model of water-sensitive shale based on gas-water miscible competitive adsorption. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2024, 42, 1841–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Hu, Z.M.; Shen, R.; Chang, J.; Duan, X.G.; Li, Y.R.; Guo, Q.L. Water Occurrence Characteristics of Gas Shale Based on 2D NMR Technology. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 910–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.W.J.; Celia, M.A. Shale Gas Well, Hydraulic Fracturing, and Formation Data to Support Modeling of Gas and Water Flow in Shale Formations. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 3196–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Hu, Z.M.; Chang, J.; Duan, X.G.; Li, Y.L.; Li, Y.R.; Niu, W.T. Effect of water occurrence on shale seepage ability. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 204, 108725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhou, J.P.; Xian, X.F.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, C.P.; Lu, Z.H.; Yin, H. Changes of wettability of shale exposed to supercritical CO2-water and its alteration mechanism: Implication for CO2 geo-sequestration. Fuel 2024, 357, 129942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, S.; Sakurovs, R.; Weir, S. Supercritical gas sorption on moist coals. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2008, 74, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Ma, T.R.; Kang, Y.L.; Du, H.Z.; Xie, S.L.; Ma, D.P. A fractal model for gas-water relative permeability in inorganic shale considering water occurrence state. Fuel 2025, 381, 133664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shan, W.; Wang, X. Quantitative evaluation of organic porosity and inorganic porosity in shale gas reservoirs using logging data. Energy Sources Part A-Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2019, 41, 811–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liang, F.; Li, H.; Zheng, M.J.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W.P. Breakthrough and enrichment mode of marine shale gas in the Lower Cambrian Qiongzhusi Formation in high-yield wells in Sichuan Basin. China Pet. Explor. 2024, 29, 142–155. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.Y.; Jin, Z.J.; Liu, Q.Y.; Huang, Z.K. Depositional process and astronomical forcing model of lacustrine fine-grained sedimentary rocks: A case study of the early Paleogene in the Dongying Sag, Bohai Bay Basin. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2020, 113, 103995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.Y.; Jin, Z.J.; Liu, Q.Y.; Huang, Z.K. Lithofacies classification and origin of the Eocene lacustrine fine-grained sedimentary rocks in the Jiyang Depression, Bohai Bay Basin, Eastern China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2020, 194, 104002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Series/Sublayer | Burial Depth (m) | TOC (%) | Clay Mineral (%) | Brittle mineral (%) | Pyrite (%) | Water Content (%, wt.) | Water Saturation (%) | Porosity (%) | Effective Porosity (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz | Feldspar | Carbonate | |||||||||||

| K-Feldspar | Plagioclase | Calcite | Dolomite | ||||||||||

| QZS2/SL7 | 3871.91 | 0.87 | 39.10 | 33.40 | 2.30 | 11.50 | 2.30 | 7.40 | 4.00 | 1.67 | 57.13 | 2.92 | 1.25 |

| 3895.69 | 3.83 | 25.40 | 39.10 | 1.90 | 15.60 | 8.40 | 5.50 | 4.10 | 0.86 | 21.40 | 4.04 | 3.17 | |

| 3873.84 | 0.93 | 33.40 | 38.20 | 1.80 | 10.90 | 4.60 | 6.80 | 4.30 | 1.62 | 57.58 | 2.82 | 1.20 | |

| 3874.73 | 1.56 | 26.80 | 35.60 | 2.20 | 10.50 | 8.40 | 12.90 | 3.60 | 1.19 | 52.08 | 2.29 | 1.10 | |

| 3875.83 | 1.26 | 33.10 | 35.70 | 1.30 | 7.90 | 5.10 | 13.30 | 3.60 | 1.29 | 58.49 | 2.20 | 0.91 | |

| 3876.92 | 1.12 | 37.90 | 34.30 | 1.60 | 7.80 | 2.90 | 12.10 | 3.40 | 1.35 | 51.19 | 2.64 | 1.29 | |

| 3877.71 | 1.05 | 35.40 | 37.80 | 1.60 | 9.80 | 2.40 | 8.00 | 5.00 | 1.57 | 48.13 | 3.27 | 1.69 | |

| 3878.68 | 1.36 | 37.30 | 34.30 | 1.50 | 8.50 | 2.70 | 12.70 | 3.00 | 1.48 | 42.71 | 3.48 | 1.99 | |

| 3879.69 | 1.65 | 40.60 | 35.20 | 1.70 | 10.60 | 1.90 | 6.10 | 3.90 | 1.50 | 46.28 | 3.23 | 1.74 | |

| 3881.32 | 1.83 | 39.90 | 37.30 | 1.90 | 10.20 | 2.50 | 5.10 | 3.10 | 1.24 | 48.18 | 2.57 | 1.33 | |

| 3882.18 | 2.51 | 28.30 | 35.10 | 2.00 | 12.30 | 12.20 | 6.20 | 3.20 | 1.11 | 37.44 | 2.97 | 1.86 | |

| 3882.66 | 2.31 | 32.60 | 36.10 | 2.30 | 13.90 | 4.30 | 7.10 | 3.70 | 1.32 | 43.28 | 3.06 | 1.74 | |

| 3883.65 | 2.83 | 36.50 | 34.90 | 1.60 | 11.40 | 5.50 | 5.90 | 3.40 | 1.26 | 33.56 | 3.76 | 2.50 | |

| 3884.83 | 3.08 | 26.20 | 37.80 | 3.70 | 15.30 | 7.10 | 5.40 | 3.40 | 1.01 | 23.45 | 4.30 | 3.29 | |

| 3886.72 | 3.86 | 18.60 | 40.30 | 2.90 | 16.90 | 11.00 | 4.80 | 4.10 | 0.86 | 14.63 | 5.89 | 5.03 | |

| 3887.66 | 2.52 | 25.70 | 34.70 | 1.20 | 11.50 | 9.30 | 14.00 | 2.80 | 0.95 | 29.59 | 3.22 | 2.27 | |

| 3888.89 | 2.70 | 28.80 | 37.30 | 2.10 | 13.20 | 6.90 | 8.60 | 3.10 | 0.96 | 30.13 | 3.19 | 2.23 | |

| 3889.81 | 2.82 | 32.50 | 40.90 | 2.60 | 12.50 | 3.40 | 4.10 | 3.50 | 1.13 | 30.13 | 3.74 | 2.62 | |

| 3890.82 | 3.05 | 25.20 | 40.80 | 2.00 | 9.60 | 14.70 | 4.70 | 2.40 | 0.81 | 16.39 | 4.94 | 4.13 | |

| 3891.75 | 2.78 | 28.10 | 40.20 | 2.80 | 15.00 | 4.60 | 5.40 | 3.90 | 1.10 | 29.31 | 3.77 | 2.66 | |

| 3892.75 | 3.51 | 29.60 | 41.40 | 2.80 | 13.50 | 3.30 | 5.50 | 3.90 | 0.91 | 21.61 | 4.23 | 3.32 | |

| 3893.66 | 4.17 | 29.40 | 41.60 | 1.70 | 14.70 | 2.40 | 5.60 | 4.60 | 1.08 | 17.77 | 6.09 | 5.01 | |

| 3894.91 | 3.50 | 27.60 | 39.30 | 2.00 | 15.50 | 7.40 | 4.50 | 3.70 | 1.03 | 20.50 | 5.03 | 4.00 | |

| 3896.71 | 3.79 | 26.50 | 41.20 | 2.10 | 15.00 | 6.40 | 5.10 | 3.70 | 0.90 | 17.89 | 5.01 | 4.11 | |

| 3897.76 | 3.91 | 27.00 | 43.00 | 2.80 | 14.90 | 4.00 | 4.30 | 4.00 | 0.99 | 20.62 | 4.81 | 3.82 | |

| 3898.77 | 3.75 | 26.80 | 41.40 | 2.80 | 15.20 | 4.80 | 4.80 | 3.60 | 0.84 | 17.38 | 4.85 | 4.01 | |

| 3899.60 | 4.07 | 24.90 | 40.70 | 3.70 | 16.30 | 6.30 | 3.70 | 3.80 | 0.79 | 15.09 | 5.24 | 4.45 | |

| QZS1/SL5 | 3992.85 | 1.33 | 25.50 | 37.80 | 4.00 | 21.90 | 1.80 | 4.50 | 4.00 | 0.90 | 41.66 | 2.16 | 1.26 |

| 3993.83 | 1.20 | 25.10 | 38.00 | 3.50 | 24.00 | 1.50 | 3.70 | 4.20 | 0.92 | 43.08 | 2.13 | 1.21 | |

| 3994.79 | 1.36 | 21.50 | 38.10 | 5.70 | 25.20 | 1.90 | 3.30 | 4.30 | 0.83 | 37.34 | 2.24 | 1.40 | |

| 3995.88 | 1.55 | 24.00 | 39.80 | 3.60 | 24.10 | 1.10 | 2.80 | 4.60 | 0.82 | 36.43 | 2.26 | 1.44 | |

| 3996.84 | 1.40 | 22.00 | 40.60 | 4.70 | 24.40 | 1.50 | 2.50 | 4.30 | 0.94 | 38.06 | 2.46 | 1.52 | |

| 3997.65 | 1.14 | 16.70 | 39.10 | 6.40 | 29.70 | 1.90 | 3.10 | 3.10 | 0.77 | 36.43 | 2.11 | 1.34 | |

| 3998.78 | 1.26 | 22.10 | 38.30 | 5.10 | 26.10 | 1.90 | 3.20 | 2.90 | 0.85 | 34.51 | 2.46 | 1.61 | |

| 3999.82 | 1.15 | 23.10 | 38.30 | 5.00 | 25.00 | 2.60 | 3.30 | 2.70 | 0.76 | 39.81 | 1.92 | 1.16 | |

| 4001.90 | 1.50 | 18.00 | 40.20 | 5.50 | 27.70 | 2.30 | 2.80 | 3.50 | 0.77 | 36.21 | 2.12 | 1.35 | |

| 4002.82 | 1.52 | 21.80 | 37.70 | 6.20 | 25.60 | 2.00 | 3.30 | 3.40 | 0.86 | 31.95 | 2.69 | 1.83 | |

| 4003.95 | 1.72 | 20.00 | 37.90 | 3.80 | 28.20 | 1.40 | 3.20 | 5.50 | 0.82 | 34.57 | 2.37 | 1.55 | |

| 4004.95 | 2.05 | 21.70 | 35.10 | 7.30 | 27.00 | 1.30 | 3.10 | 4.00 | 0.83 | 28.47 | 2.91 | 2.08 | |

| 4005.94 | 2.00 | 18.70 | 39.30 | 7.10 | 26.30 | 2.40 | 2.20 | 3.40 | 0.67 | 18.97 | 3.55 | 2.88 | |

| 4008.32 | 1.95 | 20.80 | 33.00 | 5.40 | 30.00 | 2.90 | 3.10 | 4.80 | 0.76 | 27.99 | 2.73 | 1.97 | |

| 4009.49 | 1.73 | 22.60 | 32.90 | 6.80 | 28.90 | 2.70 | 2.30 | 3.80 | 0.93 | 33.24 | 2.81 | 1.87 | |

| 4011.30 | 1.57 | 22.70 | 32.50 | 6.70 | 23.40 | 6.80 | 2.90 | 5.00 | 0.74 | 36.95 | 1.99 | 1.26 | |

| 4012.36 | 1.59 | 24.30 | 31.10 | 5.90 | 26.50 | 3.60 | 3.10 | 5.50 | 0.83 | 36.69 | 2.27 | 1.44 | |

| 4013.34 | 1.50 | 27.90 | 31.40 | 5.90 | 24.00 | 2.80 | 2.40 | 5.60 | 0.91 | 36.56 | 2.49 | 1.58 | |

| 4014.33 | 1.65 | 25.40 | 33.40 | 4.50 | 26.80 | 3.40 | 2.30 | 4.20 | 0.84 | 34.67 | 2.42 | 1.58 | |

| 4014.97 | 1.76 | 24.90 | 33.30 | 4.60 | 27.30 | 1.90 | 2.60 | 5.40 | 0.83 | 39.05 | 2.12 | 1.29 | |

| 4016.29 | 1.75 | 24.20 | 31.30 | 8.30 | 27.30 | 2.90 | 1.60 | 4.10 | 0.90 | 34.56 | 2.62 | 1.71 | |

| 4017.44 | 2.05 | 23.30 | 36.10 | 4.70 | 26.80 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 4.10 | 0.84 | 30.45 | 2.75 | 1.91 | |

| 4018.36 | 1.53 | 23.30 | 32.20 | 5.50 | 27.00 | 5.70 | 2.20 | 4.10 | 0.86 | 34.87 | 2.48 | 1.61 | |

| 4019.34 | 1.60 | 22.60 | 36.10 | 4.60 | 27.60 | 3.50 | 2.00 | 3.60 | 0.84 | 33.14 | 2.53 | 1.69 | |

| 4021.20 | 1.67 | 23.80 | 33.90 | 5.90 | 27.70 | 2.10 | 2.00 | 4.60 | 0.80 | 30.60 | 2.60 | 1.81 | |

| 4022.04 | 1.74 | 22.60 | 36.70 | 5.50 | 26.20 | 1.70 | 2.30 | 5.00 | 0.73 | 33.82 | 2.16 | 1.43 | |

| 4023.20 | 1.78 | 23.60 | 34.20 | 6.00 | 27.50 | 2.10 | 2.10 | 4.50 | 0.78 | 42.79 | 1.82 | 1.04 | |

| 4024.22 | 1.62 | 26.60 | 34.30 | 4.00 | 25.20 | 2.20 | 2.60 | 5.10 | 0.83 | 38.24 | 2.18 | 1.35 | |

| 4025.26 | 1.30 | 25.60 | 36.10 | 4.50 | 24.90 | 1.30 | 2.70 | 4.90 | 0.74 | 49.40 | 1.51 | 0.76 | |

| 4026.35 | 1.55 | 31.00 | 32.90 | 5.30 | 23.80 | 1.30 | 1.70 | 4.00 | 0.82 | 40.13 | 2.05 | 1.23 | |

| 4027.23 | 1.45 | 24.10 | 32.40 | 6.10 | 29.00 | 1.80 | 2.50 | 4.10 | 0.74 | 38.21 | 1.93 | 1.19 | |

| 4028.24 | 1.47 | 27.10 | 34.80 | 5.60 | 24.40 | 1.80 | 2.00 | 4.30 | 0.80 | 44.47 | 1.79 | 1.00 | |

| 4029.04 | 1.22 | 20.40 | 32.80 | 8.00 | 30.20 | 2.00 | 3.50 | 3.10 | 0.85 | 42.25 | 2.01 | 1.16 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, W.; Xu, L.; Luo, C.; Gao, H.; Liu, H.; Shi, X.; Gai, H.; Cheng, P. Influence of Organic and Inorganic Compositions on the Porosity of the Deep Qiongzhusi Shales on the Margin of the Deyang–Anyue Aulacogen, Sichuan Basin: Implications from the Shale Samples of Well Z204. Processes 2025, 13, 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123880

Wu W, Xu L, Luo C, Gao H, Liu H, Shi X, Gai H, Cheng P. Influence of Organic and Inorganic Compositions on the Porosity of the Deep Qiongzhusi Shales on the Margin of the Deyang–Anyue Aulacogen, Sichuan Basin: Implications from the Shale Samples of Well Z204. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123880

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Wei, Liang Xu, Chao Luo, Haitao Gao, Huan Liu, Xinyue Shi, Haifeng Gai, and Peng Cheng. 2025. "Influence of Organic and Inorganic Compositions on the Porosity of the Deep Qiongzhusi Shales on the Margin of the Deyang–Anyue Aulacogen, Sichuan Basin: Implications from the Shale Samples of Well Z204" Processes 13, no. 12: 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123880

APA StyleWu, W., Xu, L., Luo, C., Gao, H., Liu, H., Shi, X., Gai, H., & Cheng, P. (2025). Influence of Organic and Inorganic Compositions on the Porosity of the Deep Qiongzhusi Shales on the Margin of the Deyang–Anyue Aulacogen, Sichuan Basin: Implications from the Shale Samples of Well Z204. Processes, 13(12), 3880. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123880