NMR Analysis of Imbibition and Damage Mechanisms of Fracturing Fluid in Jimsar Shale Oil Reservoirs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

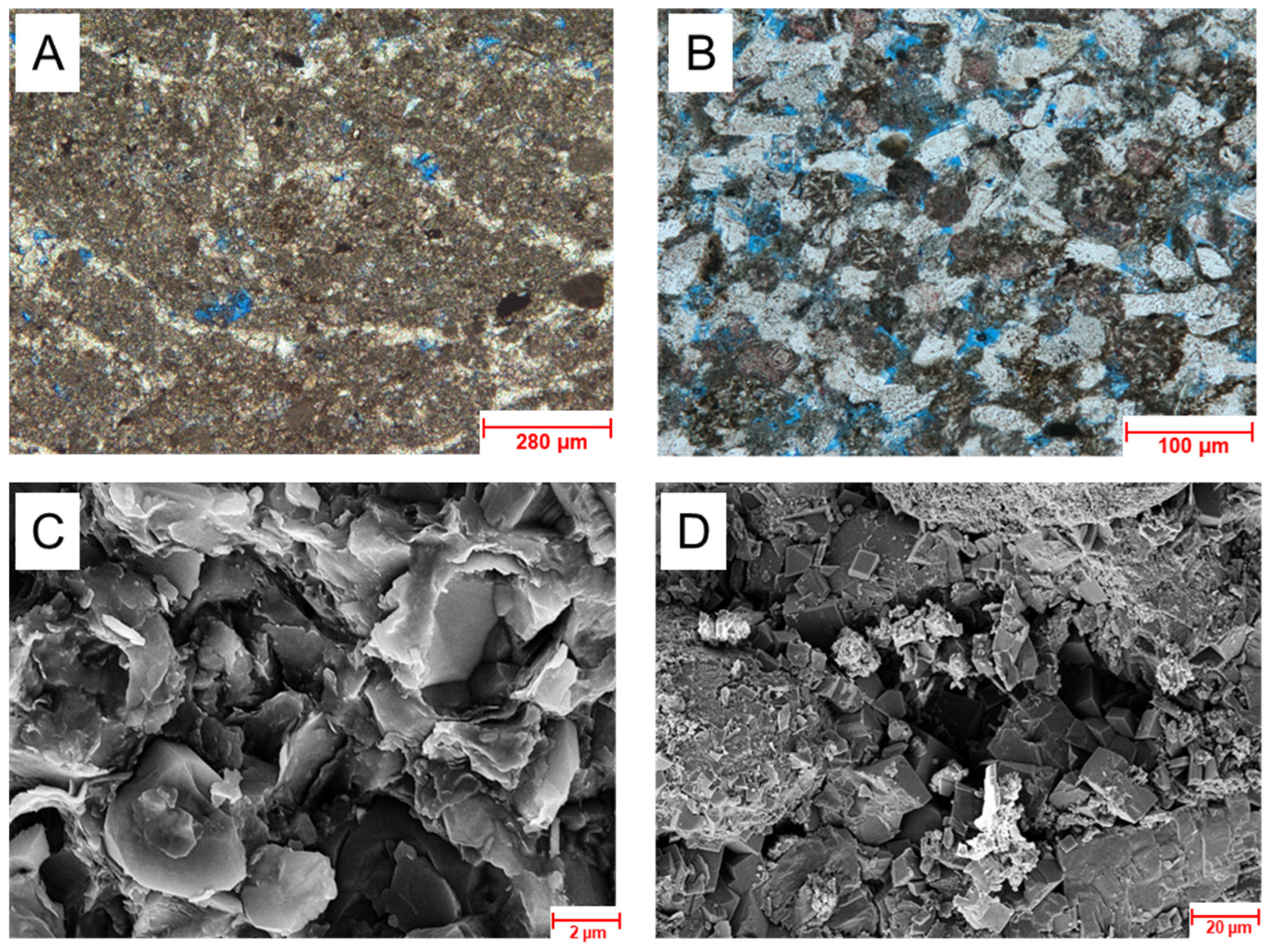

2.2. Petrological Analysis Experiments

2.3. Spontaneous Imbibition Experiments Using NMR

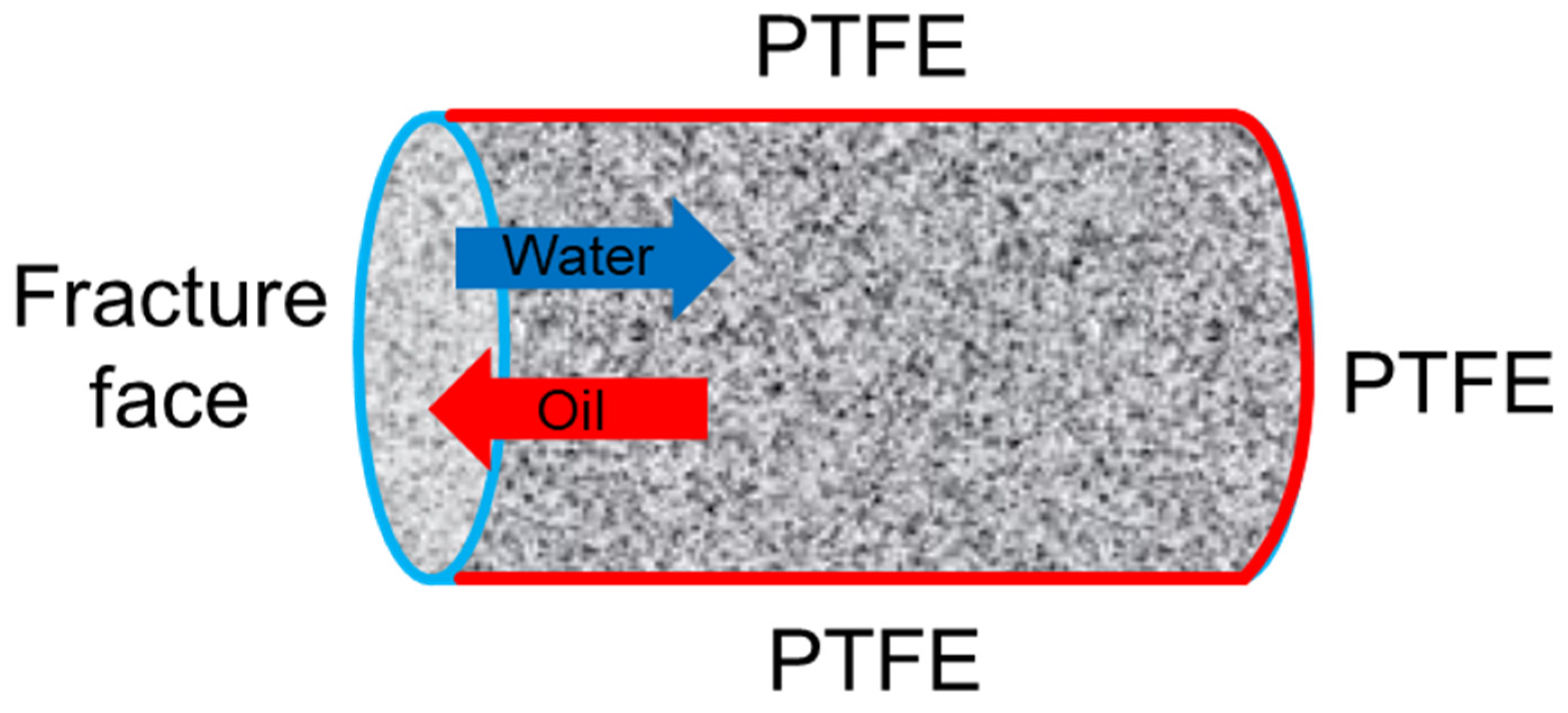

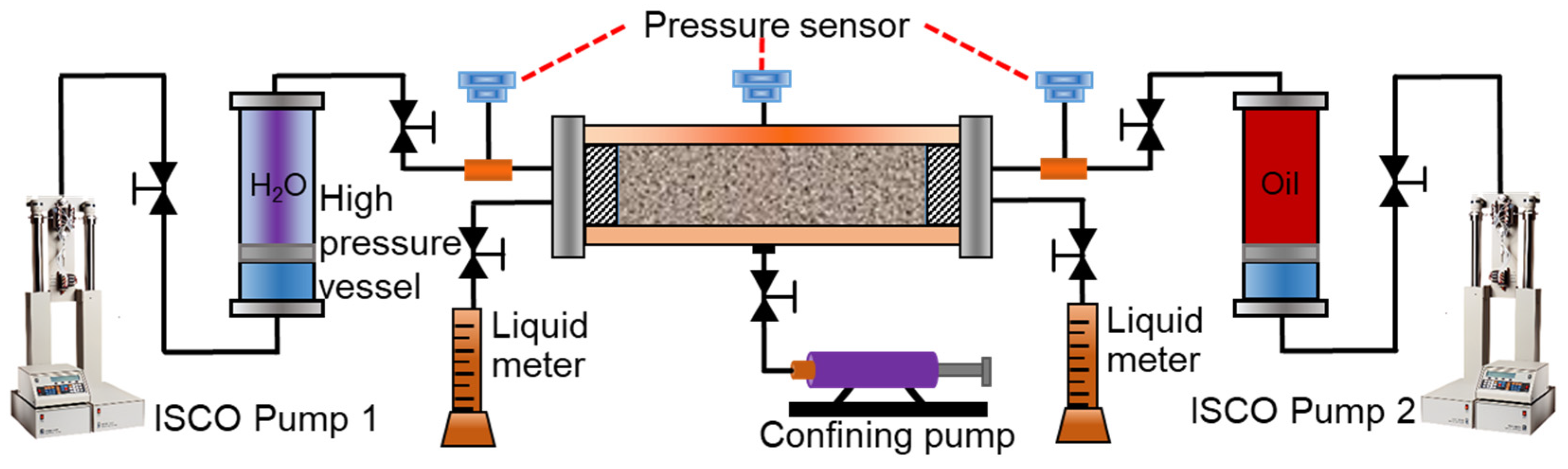

2.4. Permeability Damage Evaluation Experiment

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mineral Composition and Microstructure of the Reservoir

3.2. Fracturing Fluid Imbibition Characteristics

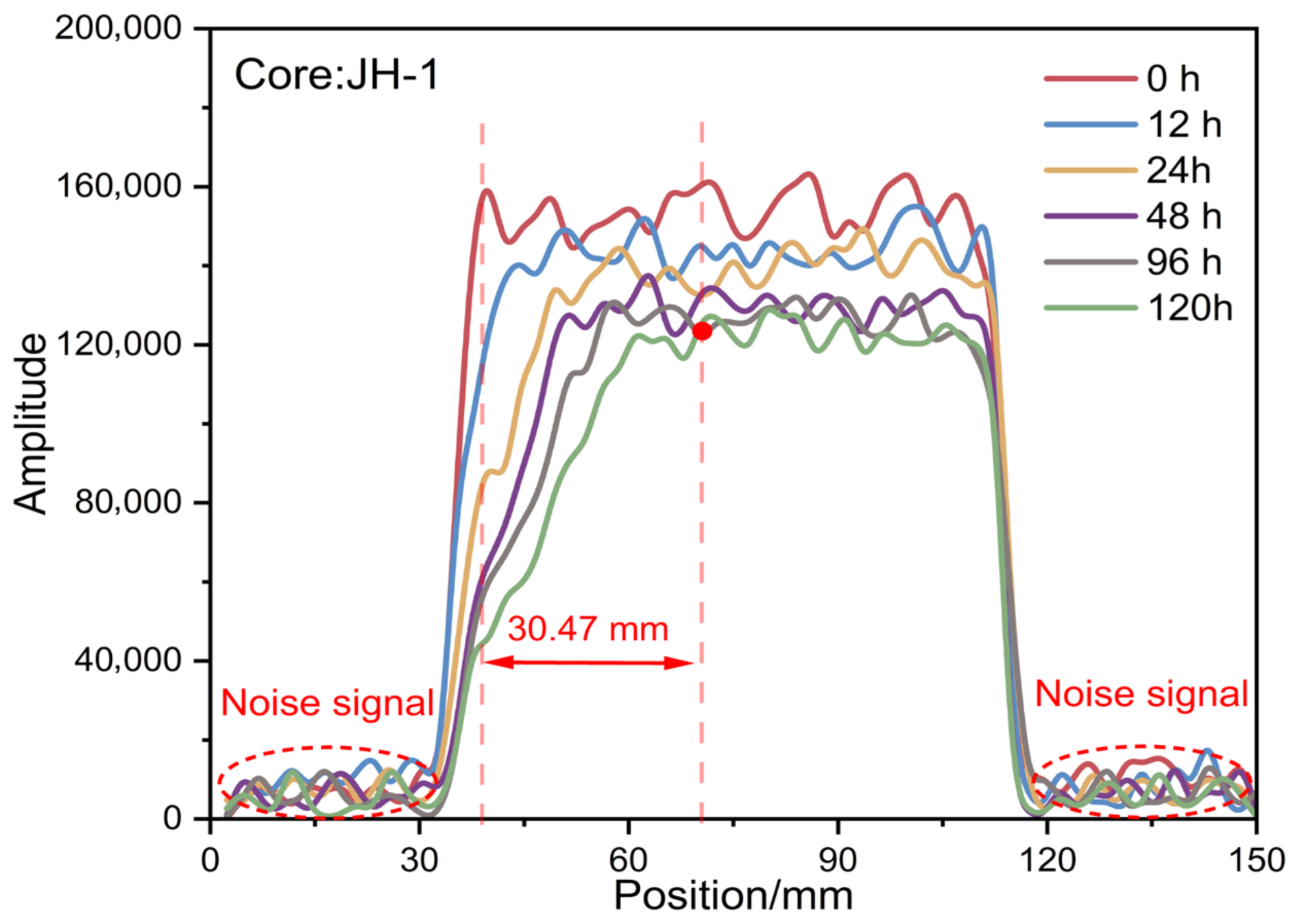

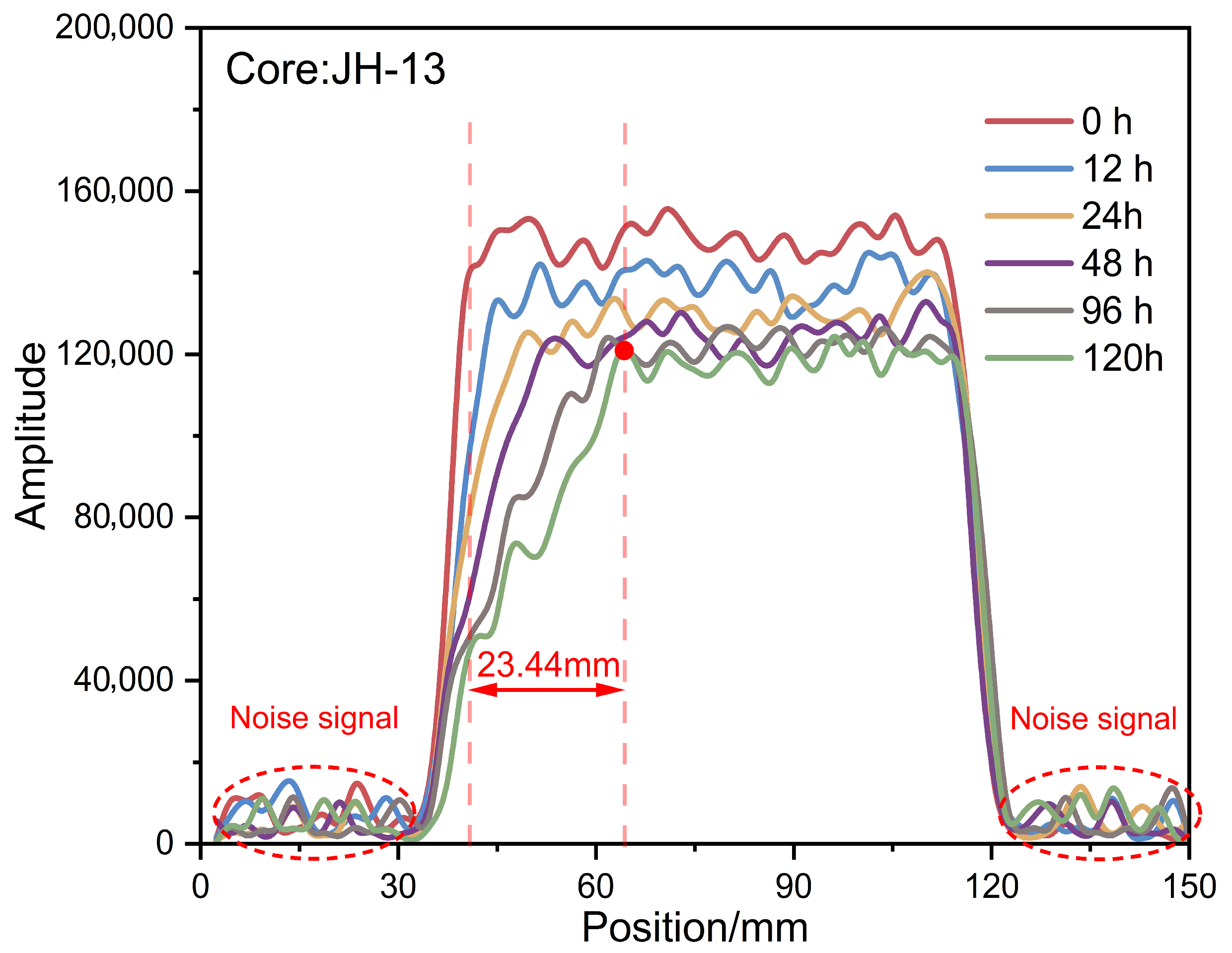

3.2.1. Characteristics of Fracturing Fluid Invasion into Cores

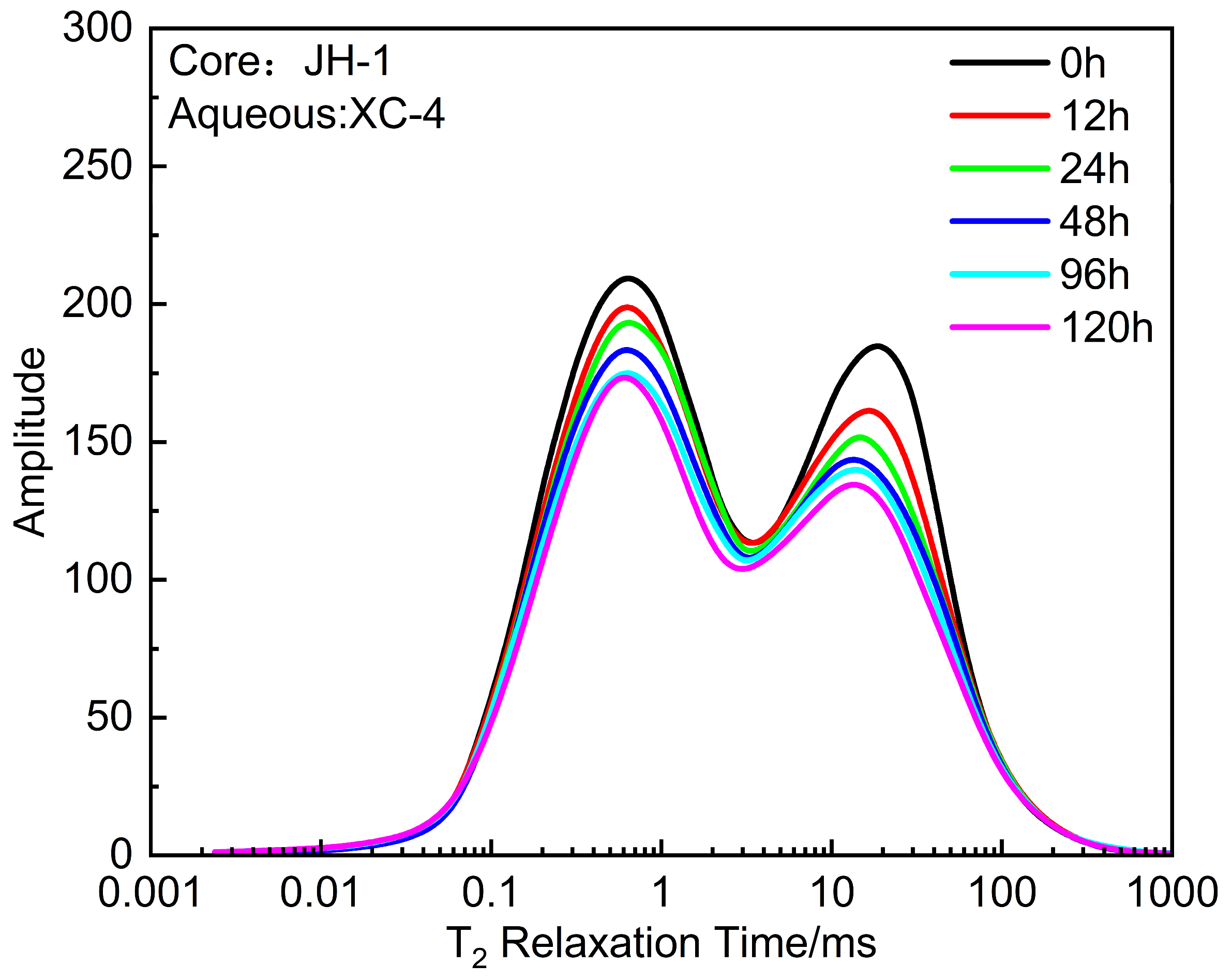

3.2.2. Dynamic Imbibition Analysis Based on NMR T2 Relaxation

3.3. Degree of Permeability Damage Induced by Fracturing

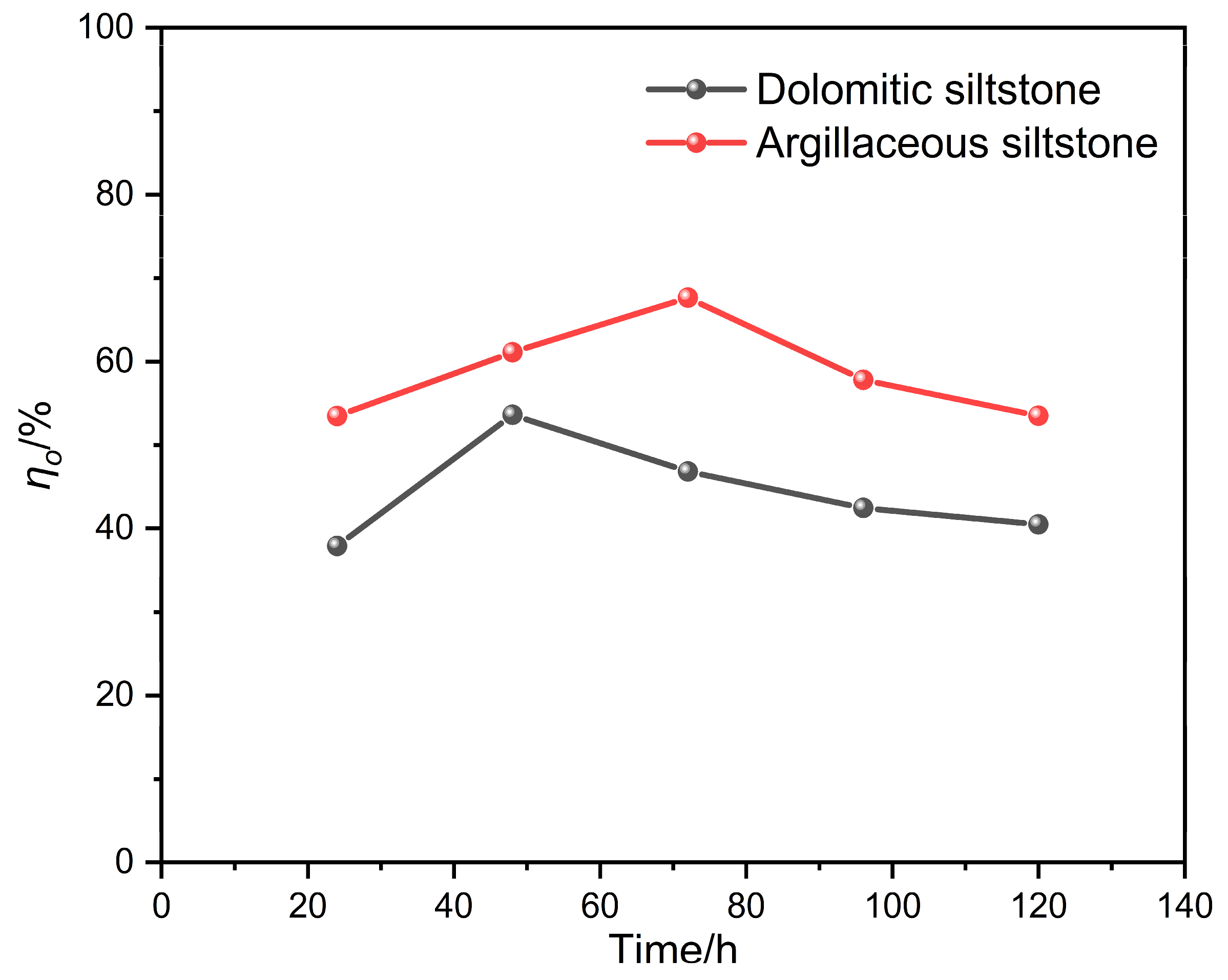

3.3.1. Influence of Lithology

3.3.2. Influence of Shut-In Time

3.3.3. Influence of Flowback Volume

3.4. Implications for Fracturing Operations

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, L.; Pan, L.; Zou, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Feng, W. Recent Advances in Reservoir Stimulation and Enhanced Oil Recovery Technology in Unconventional Reservoirs. Processes 2024, 12, 10234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.D.; Geng, X.F.; Liu, W.D.; Ding, B.; Xiong, C.M.; Sun, J.F.; Wang, C.; Jiang, K. A Comprehensive Review on Screening, Application, and Perspectives of Surfactant-Based Chemical-Enhanced Oil Recovery Methods in Unconventional Oil Reservoirs. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 4729–4750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, T.P.; Larson, T.E.; Zhang, T.; Shuster, M. Geologic characteristics, exploration and production progress of shale oil and gas in the United States: An overview. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 925–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.M. Current Situation and Existing Problems of Horizontal Well Fracturing Technology. Chem. Technol. Fuels Oils 2024, 60, 1307–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.Y.; Li, C.; Sun, L.C.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Li, N. Study on the Influence of Deep Coalbed Methane Horizontal Well Deployment Orientation on Production. Energies 2024, 17, 5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.R.; Yan, B.Q.; Yu, L.M.; Li, Z. Production Capacity Variations of Horizontal Wells in Tight Reservoirs Controlled by the Structural Characteristics of Composite Sand Bodies: Fuyu Formation in the Qian’an Area of the Songliao Basin as an Example. Processes 2023, 11, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Abass, H.; Li, X.; Teklu, T. Experimental investigation of the effect of imbibition on shale permeability during hydraulic fracturing. J. Nat. Gas. Sci. Eng. 2016, 29, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, Q.; Yao, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Lei, G. Reservoir Damage Induced by Water-Based Fracturing Fluids in Tight Reservoirs: A Review of Formation Mechanisms and Treatment Methods. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 18093–18115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Liao, K.; Ge, J.; Huang, W.; Chen, L.; Sun, X.; Zhang, S. Study on the damage and control method of fracturing fluid to tight reservoir matrix. J. Nat. Gas. Sci. Eng. 2020, 82, 103464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X. A comprehensive review of minimum miscibility pressure determination and reduction strategies between CO2 and crude oil in CCUS processes. Fuel 2025, 384, 134053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Wortman, P. Understanding the post-frac soaking process in multi-fractured shale gas-oil wells. Capillarity 2024, 12, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.F.; Nasr-El-Din, H.A. Effect of well shut-in after fracturing operations on near wellbore permeability. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 181, 106213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hun, L.; Bing, Y.; Xixiang, S.; Xinyi, S.; Lifei, D. Fracturing fluid retention in shale gas reservoir from the perspective of pore size based on nuclear magnetic resonance. J. Hydrol. 2021, 601, 126590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, S. Damage evolution characteristics caused by fluid infiltration across diverse injection rates: Insights from integrated NMR and hydraulic fracturing experiments. J. Rock. Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2025, 17, 5753–5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yang, S.-L.; Zuo, H.-W.; Liu, X.-Y.; Dang, Y.-L.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Wang, B.-D.; Hu, J.-T.; Bai, H.-Y.; Han, Y.-N. NMR-Visualized Mechanisms of Nanoparticle-Stabilized Ternary CO2 Foam for EOR in Low-Permeability Reservoirs. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 21412–21421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yang, S.-L.; Bai, H.-Y.; Han, Y.-N.; Wang, B.-D.; Yang, K.; Hu, J.-T.; Luo, Y.; Liu, X.-Y. Enhancing oil recovery in tight fractured reservoirs: An NMR study of foam flooding with imbibition effects. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 726, 137745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhao, S. Influence of Shale Mineral Composition and Proppant Filling Patterns on Stress Sensitivity in Shale Reservoirs. Processes 2024, 12, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, Z.; Wei, B.; Jiang, Q. A novel approach for quantitative characterization of aqueous in-situ foam dynamic structure based on fractal theory. Fuel 2023, 352, 129149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeizadeh, M.; Hajiabadi, S.H.; Aghaei, H.; Blunt, M.J. Pore-scale analysis of formation damage; A review of existing digital and analytical approaches. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2021, 288, 102345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minh, C.C.; Jaffuel, F.; Poirier, Y.; Haq, S.A.; Baig, M.H.; Jacob, C. Quantitative Estimation Of Formation Damage From Multi-Depth Of Investigation Nmr Logs. In Proceedings of the SPWLA 52nd Annual Logging Symposium, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 14–18 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Label | D/cm | L/cm | φ/% | k/md | Lithology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JH-1 | 2.53 | 7.12 | 14.21 | 0.18 | Dolomitic siltstone |

| JH-2 | 2.51 | 7.04 | 13.22 | 0.17 | Dolomitic siltstone |

| JH-3 | 2.52 | 7.16 | 15.14 | 0.15 | Dolomitic siltstone |

| JH-4 | 2.57 | 7.08 | 12.89 | 0.11 | Dolomitic siltstone |

| JH-5 | 2.57 | 7.11 | 14.11 | 0.12 | Dolomitic siltstone |

| JH-6 | 2.49 | 7.14 | 12.68 | 0.14 | Dolomitic siltstone |

| JH-7 | 2.47 | 7.12 | 15.23 | 0.13 | Dolomitic siltstone |

| JH-8 | 2.49 | 7.06 | 12.94 | 0.12 | Dolomitic siltstone |

| JH-9 | 2.51 | 7.11 | 13.52 | 0.14 | Dolomitic siltstone |

| JH-10 | 2.53 | 7.14 | 14.16 | 0.11 | Argillaceous siltstone |

| JH-11 | 2.24 | 7.12 | 13.95 | 0.13 | Argillaceous siltstone |

| JH-12 | 2.52 | 7.10 | 12.55 | 0.15 | Argillaceous siltstone |

| JH-13 | 2.53 | 7.11 | 14.18 | 0.17 | Argillaceous siltstone |

| JH-14 | 2.51 | 7.06 | 13.35 | 0.12 | Argillaceous siltstone |

| JH-15 | 2.54 | 7.04 | 14.12 | 0.14 | Argillaceous siltstone |

| JH-16 | 2.52 | 7.12 | 12.85 | 0.13 | Argillaceous siltstone |

| JH-17 | 2.57 | 7.09 | 13.70 | 0.14 | Argillaceous siltstone |

| JH-18 | 2.51 | 7.12 | 12.69 | 0.12 | Argillaceous siltstone |

| Function | Pulse Sequences | SF (MHz) | DW (us) | TAU (us) | TE (ms) | SCAN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2 | CPMG | 14.06 | 2.0 | 150 | 0.3 | 64 |

| 1D frequency | GR-HSE | 14.06 | 2.0 | 150 | 1.45 | 128 |

| Label | Clay | Qtz | Kfs | Pl | Cal | Dol | Ank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JH-1 | 6.3 | 17.8 | — | 23.9 | 6.6 | — | 45.4 |

| JH-2 | 4.1 | 12.9 | 13.4 | 14.8 | 8.6 | 46.2 | — |

| JH-3 | 7.5 | 21.2 | — | 33.7 | — | — | 37.6 |

| JH-4 | 5.8 | 23.1 | 20.6 | 38.3 | — | — | 12.2 |

| JH-5 | 6.2 | 18.4 | 23.7 | 30.9 | 8.9 | — | 11.9 |

| JH-6 | 4.3 | 23.9 | — | 46.8 | 11.9 | — | 13.1 |

| JH-7 | 5.2 | 28.9 | — | 41.3 | — | 13.1 | 11.5 |

| JH-8 | 6.1 | 19.8 | 9.9 | 28.8 | 19.6 | — | 15.8 |

| JH-9 | 4.3 | 21.5 | — | 36.8 | 8.8 | — | 28.6 |

| JH-10 | 19.4 | 13.4 | 6.5 | 23.4 | 4.8 | 32.5 | — |

| JH-11 | 18.1 | 12.8 | 8.1 | 24.4 | 7.1 | 11.2 | 18.3 |

| JH-12 | 16.9 | 19.4 | 9.9 | 29.7 | 12.8 | — | 11.3 |

| JH-13 | 17.8 | 21.0 | 13.8 | 29.5 | 12.3 | 5.6 | — |

| JH-14 | 14.9 | 23.3 | 12.0 | 31.2 | 11.2 | 7.4 | — |

| JH-15 | 18.2 | 20.4 | 9.2 | 21.7 | 10.6 | 6.8 | 13.1 |

| JH-16 | 19.8 | 17.9 | 21.2 | 15.8 | 17.1 | — | 8.2 |

| JH-17 | 16.5 | 14.7 | 23.8 | 30.2 | 4.1 | — | 10.7 |

| JH-18 | 19.3 | 20.4 | 14.8 | 28.5 | 7.8 | — | 9.2 |

| Label | Lithology | ko1/mD | ko2/mD | ηo/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JH-3 | Dolomitic siltstone | 0.079 | 0.042 | 46.8 |

| JH-12 | Argillaceous siltstone | 0.068 | 0.020 | 70.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bai, L.; Guo, H.; Jiang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Han, Y.; Han, X.; Yang, S.; Zhao, S. NMR Analysis of Imbibition and Damage Mechanisms of Fracturing Fluid in Jimsar Shale Oil Reservoirs. Processes 2025, 13, 3875. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123875

Bai L, Guo H, Jiang Z, Sun Y, Li Y, Han Y, Han X, Yang S, Zhao S. NMR Analysis of Imbibition and Damage Mechanisms of Fracturing Fluid in Jimsar Shale Oil Reservoirs. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3875. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123875

Chicago/Turabian StyleBai, Lei, Huiying Guo, Zhaowen Jiang, Yating Sun, Yan Li, Yuning Han, Xuejing Han, Shenglai Yang, and Shuai Zhao. 2025. "NMR Analysis of Imbibition and Damage Mechanisms of Fracturing Fluid in Jimsar Shale Oil Reservoirs" Processes 13, no. 12: 3875. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123875

APA StyleBai, L., Guo, H., Jiang, Z., Sun, Y., Li, Y., Han, Y., Han, X., Yang, S., & Zhao, S. (2025). NMR Analysis of Imbibition and Damage Mechanisms of Fracturing Fluid in Jimsar Shale Oil Reservoirs. Processes, 13(12), 3875. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123875