Abstract

Alumina nanoparticles have broad applications in catalysis, electronics, and the construction sector, and are widely incorporated as additives in coating formulations to enhance mechanical durability and functional performance. This work focuses on the green synthesis of aluminum oxide (Al2O3) nanoparticles using lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) extract. Aluminum nitrate [Al(NO3)3] and aluminum chloride (AlCl3) were used with extract. The reaction was carried out at 70 °C for 1 h at 250 rpm and then thermal treatments at 700 °C and 900 °C were applied. The results showed that nanoparticles synthesized from the AlCl3 and calcined at 700 °C exhibited a smaller particle size (36 ± 14 nm) as compared with those synthesized from the [Al(NO3)3] and calcined at 700 °C (49 ± 25 nm). Despite both precursors yielding nanoparticles, the peaks related to the γ-Al2O3 crystal phase were observed in the AlCl3 at 700 °C calcination. Conversely, the nanoparticles synthesized from the [Al(NO3)3] required a high temperature treatment at 900 °C to display this stable crystal phase. This study reports an easy and cost-effective green chemistry route to obtain γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles, highlighting the importance of the selection of precursors as a critical step to achieve a sustainable and low-energy process, suggesting the potential applications in paints with multifunctional properties.

1. Introduction

Metal oxide nanomaterials stand out for their remarkable physicochemical properties, such as high catalytic activity, thermal stability, and adsorption capacity [1]. Their reduced size (10–100 nanometers) and high surface-to-volume ratio mainly account for these features. Moreover, they can be used to improve mechanical and thermal resistance in ceramic materials; to fabricate semiconductors and electronic devices [2] due to their dielectric nature; to provide protective coatings against friction and high temperatures in the aerospace industry; to serve as antimicrobial agents and drug carriers in medicine; to enable the controlled release of nutrients in agriculture; and to develop chemical sensors for gas detection [3]. Among all known metal oxide nanomaterials, aluminum oxide (Al2O3) nanoparticles have attracted considerable interest in the design and formulation of antimicrobial agents for sustainable biomedical applications, since they are chemically bio-inert and exhibit good hydrolytic stability [4]. Additionally, the Al2O3 nanoparticles can be used as additives for paints and coating materials to provide functional properties, such as antifungal activity [5,6], self-cleaning [7,8], and UV protection by generating a reflective effect [4].

The synthesis of nanoparticles through green chemistry [9] has become a sustainable alternative to traditional methods, which often require the use of toxic reagents and high energy consumption. In this green approach, plant extracts containing active components such as flavonoids, polyphenols, enzymes, and terpenes are used as ion chelators, reducing agents, and stabilizers during the nanoparticle formation [10].

Several studies have reported the green synthesis of alumina nanoparticles using plant extracts such as Coffea (coffee), Camellia sinensis (tea), and Triphala (Indian gooseberry), under microwave irradiation, producing nanoparticles with spherical or oval morphologies and sizes ranging from 50 to 100 nm [11]. Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) is an herbaceous plant rich in phytocomponents such as terpenoids, flavonoids, and phenolic acids. These secondary metabolites exhibit high chelating and antioxidant capacities, which are useful for the nucleation and stabilization of nanomaterials when a green synthesis approach is applied. Ansari and coworkers [12] reported the effectiveness of lemongrass extract for the synthesis of spherical Al2O3 nanoparticles with an average size of 34.5 nm and a strong antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa by using a minimal inhibitory concentration of nanoparticles ranging from 1600 to 3200 μg/mL [12], in contrast with the current study, we employ a simpler and energy-efficient method that does not require microwave-assisted equipment. This approach improves scalability and reproducibility, while also underscoring the critical role of precursor selection in nanoparticle production. In other work, Rashid and coworkers evaluated the synthesis of Al2O3 nanoparticles using red onion peel extract and aluminum chloride as the precursor. They observed the formation of spherical to rod-like nanoparticles with a hexagonal crystal phase after calcination at 450 °C [13].

Several recent studies have demonstrated that the choice of aluminum precursor plays a decisive role in determining the final structure of alumina as well as the temperature required for the formation of specific crystalline phases. Wen et al. compared different aluminum precursors including chlorides, nitrates, and sulfates and showed that the anion type governs the thermal decomposition pathway and, consequently, the formation of phases such as γ-Al2O3. Their results indicated that nitrates decompose rapidly and violently, leading to materials with lower crystallinity, whereas chlorides promote a more defined formation of the gamma phase at relatively lower temperatures. These findings highlight the relevance of comparing AlCl3 and Al(NO3)3 in our synthesis, as they explain the marked differences in crystallinity observed between both precursors [14]. Complementary evidence was provided by Zheng et al. who demonstrated that the chemical nature of the precursor or catalyst can modify nucleation kinetics and the final structural order of alumina. In their study, the presence of anhydrous aluminum chloride during the hydrolysis of aluminum isopropoxide acted as a nucleation modulator, producing more uniform particles and better-ordered phases after calcination. This reinforces that even subtle variations in precursor chemistry directly affect the structural quality of the resulting alumina [15].

This research was focused on synthesizing aluminum oxide (Al2O3) nanoparticles prepared by green chemistry using lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) extract as a reducing and stabilizing agent. Moreover, the influence of the aluminum precursor on size distribution and crystal structure was analyzed. For this purpose, two different inorganic aluminum salts were evaluated: aluminum nitrate nonahydrate [Al(NO3)3.9H2O] and aluminum chloride hexahydrate [AlCl3.6H2O]. Additionally, the synthesized Al2O3 nanoparticles were submitted to thermal treatments at 700 °C and 900 °C to encourage the gamma crystal phase, which is desirable for innovative paint-type coatings; thus, this study aims to contribute to the development of suitable methods for obtaining nanomaterials applicable to multifunctional coatings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Lemongrass leaves (Cymbopogon citratus) were collected at Gambote, Bolivar, Colombia. Aluminum nitrate nonahydrate [Al(NO3)3.9H2O, 99%] and ethyl alcohol (C2H5OH, 99.5%) were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Aluminum chloride hexahydrate [AlCl3.6H2O, 99%] and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99%) were acquired from Loba Chemie (Mumbai, India) and Sigma-Aldrich (Burlington, MA, USA).

2.2. Extract Preparation of Cymbopogon citratus

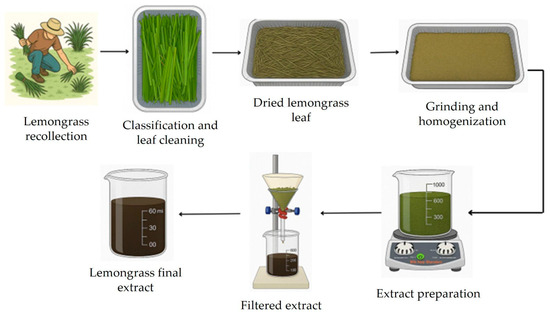

Lemongrass extract was prepared using fresh biomass, as illustrated in Figure 1. In a typical procedure, the lemongrass leaves were washed with distilled water and then placed in an oven at 60 °C for 6 h. The dried biomass was ground, and 100 g of this biomaterial was used to prepare the lemongrass extract in 600 mL of distilled water at 80 °C for 20 min. Afterward, the aqueous extract was filtered and stored in a glass bottle at 4 °C [16]

Figure 1.

Preparation of the lemongrass aqueous extract.

2.3. Synthesis of Al2O3 Nanoparticles

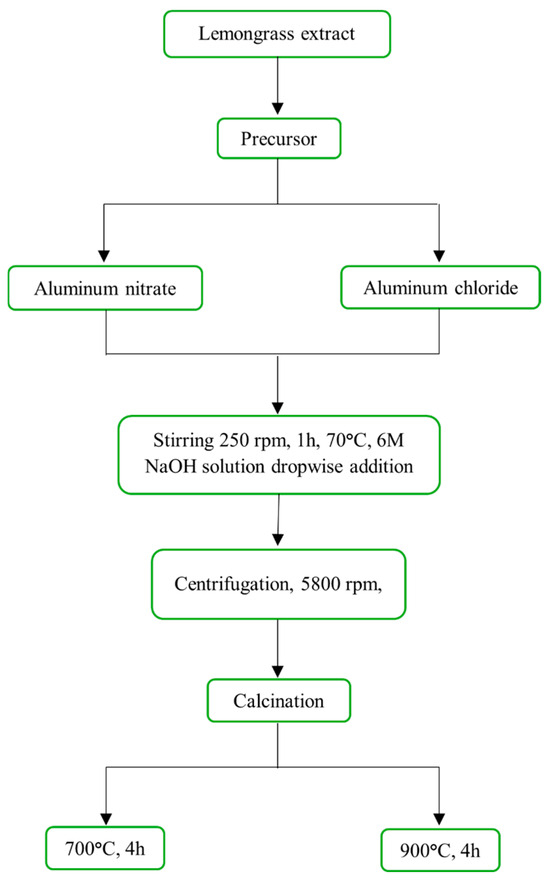

Figure 2 shows the methodology employed to obtain aluminum oxide (Al2O3) nanoparticles using lemongrass extract. The presence of terpenes and terpenoids in the extract prevents uncontrolled agglomeration of the aluminum hydroxide formed during synthesis. These phytochemicals as 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one and β-Myrcene could interact through their functional groups, effectively contributing to size control. This extract has also proven effective in the green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles in previous studies of this group [17]. Initially, 10 g of the inorganic aluminum salt precursor (aluminum nitrate or aluminum chloride) was dissolved in 100 mL of the lemongrass extract. This mixture was heated at 70 °C for 1 h at 250 rpm, with a 6M NaOH solution added dropwise; the total volume added was 14 mL for the aluminum nitrate precursor and 21 mL for the aluminum chloride, corresponding to addition rates of 0.22 mL·min−1 and 0.35 mL·min−1, respectively. The resulting nanoparticles were washed twice with deionized water and once with ethanol via centrifugation at 5800 rpm for 10 min. Finally, the nanomaterials were calcined at 700 °C and 900 °C for 4 h [3,18]. Samples were labelled according to the precursor and the calcination temperature, as follows: for aluminum nitrate (N-Al2O3-700, N-Al2O3-900) and for aluminum chloride (C-Al2O3-700, C-Al2O3-900).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of alumina oxide nanoparticles synthesized in the presence of lemongrass extract and two aluminum salt precursors.

Compared with conventional chemical synthesis, green nanoparticle production offers a lower environmental footprint. Studies report substantial reductions in emissions and toxicity based on the use of green routes under mild heating instead of the high-temperature stages of chemical methods, which may exceed 800–1500 °C [19]. Life Cycle Assessment data shows that green synthesis eliminates carcinogenic impacts and significantly decreases air-pollution-related indicators, largely due to the absence of corrosive precursors and hazardous reducing agents [20]. Additionally, the use of plant extracts and renewable biomass aligns with the principles of safer and less toxic industrial chemical processing [21].

2.4. Characterizations

Aluminum oxide nanoparticles were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) using a Thermo Fisher Scientific (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) Scios 2 LoVac Dual Beam Field Emission Electron Microscope equipped with an UltraDry 129 eV 30 mm2 EDS microanalysis system (SDBX-30PM-B). Samples were analyzed at a resolution of 0.7 nm, 30 kV in STEM mode, and 1.4 nm at 1 kV in FESEM mode [22,23]. Furthermore, X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to analyze the crystal structure of the synthesized nanoparticles. For these measurements, a Malvern-PANalytical Empyrean 2012 diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK) was used with a Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.541 Å) at 45 kV and 40 mA. Measurements were performed in a 2θ range between 10° and 80°, with a step of 0.05° and a counting time of 50 s per step [24,25]. This technique allows for the identification of the crystalline phases present in the samples.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. SEM–EDS

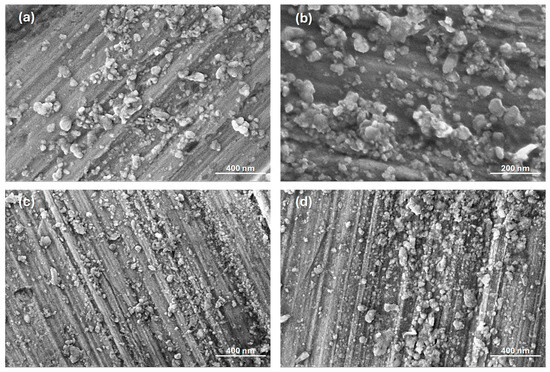

Figure 3 presents SEM images of the Al2O3 nanoparticles, in which the presence of agglomerated nanoparticles with an irregular spherical shape can be observed. Particle size distribution is displayed in Figure 4. Although a broad size distribution was observed for all samples, the largest population of nanoparticles had a size smaller than 50 nm, suggesting that for both precursors, aluminum chloride or aluminum nitrate, the phytocomponents present in the lemongrass extract prevented the growth of the nanomaterials, acting as capping and stabilizing agents. These results agree with the values reported in scientific literature. Gharbi and coworkers obtained aluminum oxide nanoparticles with an average size of 33 nm using a plant extract prepared from fire bush (Calligonum comosum L.) leaves and aluminum nitrate as the precursor reagent [18]. Additionally, Ali and coworkers reported the preparation of aluminum oxide nanoparticles by the coprecipitation method, using aluminum chloride to obtain nanoparticles with a size ranging from 30 to 50 nm [26].

Figure 3.

SEM images of the synthesized nanoparticles: (a) N-Al2O3-700; (b) N-Al2O3-900; (c) C-Al2O3-700, and (d) C-Al2O3-900.

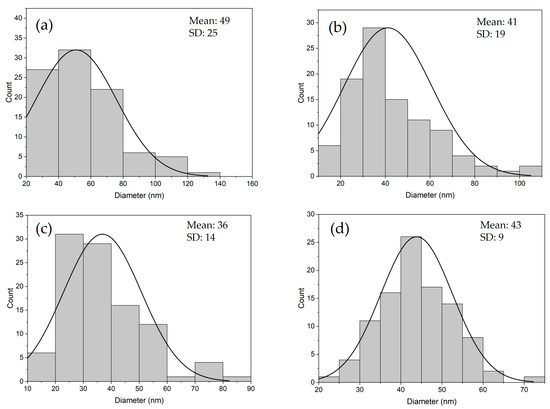

Figure 4.

Particle size distribution of the synthesized nanoparticles: (a) N-Al2O3-700; (b) N-Al2O3-900; (c) C-Al2O3-700; and (d) C-Al2O3-900.

It is important to note that nanoparticles synthesized from the AlCl3 precursor and calcined at 700 °C exhibited a smaller particle size (36 ± 14 nm) as compared with the nanoparticles obtained from the [Al(NO3)3] precursor at the same calcination temperature (49 ± 25 nm). Moreover, no significant increase in particle size was determined after thermal treatment at 900 °C for both aluminum precursors, despite slight evidence of sintering initiation being observed in Figure 3b,d, reflected in partial particle agglomeration. Suaebah and coworkers reported a relevant size increase of Al2O3 nanoparticles synthesized by the Sol–gel method from 374 nm up to 754 nm after submitting the nanoparticles to a calcination temperature of 800 °C and 1000 °C, respectively. This size increase was totally attributed to a sintering process due to grain boundary movements and material densification at the higher temperature of 1000 °C, desirable for the formation of the α- Al2O3 crystal phase [27].

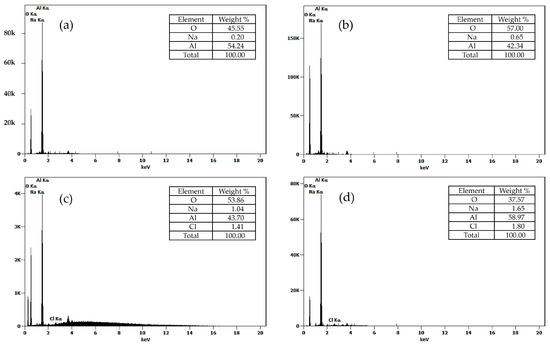

The elemental composition of the Al2O3 nanoparticles was analyzed from X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). Figure 5 presents these results, from which it was observed that all samples exhibited a high concentration of aluminum (Al) and oxygen (O), being more notable this composition at the sample C- Al2O3-900, which displays an aluminum content of 58.97% with an oxygen content of 37.5%. In addition, minimal traces of sodium (Na) were detected in all samples, derived from the precipitating agent (NaOH) used in the synthesis process. Similar results were reported by Manyasree and coworkers, who prepared Al2O3 nanoparticles by the coprecipitation of the aluminum sulfate precursor with sodium hydroxide [28].

Figure 5.

Elemental analysis by X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) for Al2O3 nanoparticles: (a) N-Al2O3-700, (b) N-Al2O3-900, (c) C-Al2O3-700, and (d) C-Al2O3-900.

The results showed traces of Na and Cl in the nanoparticles. These species originated from residual products formed during the synthesis with NaOH, a phenomenon also reported by Khine et al. [29], where NaCl may remain entrapped within hydroxide surfaces of the nanoparticles or adsorbed on metal oxide nanoparticles after washing. The detected levels are minimal, and their presence indicates that precursor and after synthesis conditions influence its surfaces.

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction

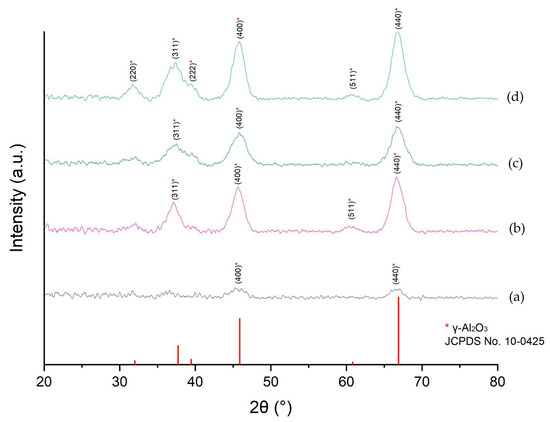

The synthesized Al2O3 nanomaterials exhibited X-ray diffraction patterns characteristic of the γ- Al2O3 phase (Figure 6), being more notable for the samples C- Al2O3-700 and C- Al2O3-900. These samples presented peaks at 32°, 38°, 46°, and 67° (Figure 6c,d), which are associated with the Miller indices (220), (311), (400), and (440), representatives of the γ-Al2O3 crystal phase (JCPDS card No. 10-0425) [18,30,31], confirming the formation of this stable crystal phase for the nanoparticles prepared with the AlCl3 precursor.

Figure 6.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the samples (a) N-Al2O3-700; (b) N-Al2O3-900; (c) C-Al2O3-700; and (d) C-Al2O3-900.

For the nanoparticles prepared from the aluminum nitrate precursor, the γ-Al2O3 crystalline phase was only observed after calcination at 900 °C for 4 h (Figure 6b). In the N-Al2O3-700 sample, no diffraction peaks corresponding to the gamma phase were detected, indicating a predominantly amorphous material. Moreover, the diffraction peaks of the N-Al2O3-900 sample were less intense and broader than those observed for the C-Al2O3-700 and C-Al2O3-900 samples, suggesting lower crystallinity or a higher content of amorphous material in the nanoparticles obtained from the [Al(NO3)3] precursor.

The average crystallite size was estimated using the Debye–Scherrer equation, where D represents the crystallite size, θ is the Bragg angle (0.5824 rad), λ is the wavelength of the Cu Kα radiation (1.541 Å), β is the full width at half maximum of the diffraction peak (FWHM = 0.0332 rad), and k is the shape factor (0.9) [18]. For the calculation, the diffraction peaks with the highest intensities corresponding to the (311), (400), and (440) planes were selected. It is important to note that no instrumental broadening correction was applied in this analysis; therefore, the calculated values should be considered approximate estimates of the crystallite size. The values obtained for the synthesized nanomaterials are presented in Table 1, observing a crystal size of approximately 4 nm for these samples, independent of the aluminum precursor or thermal treatment applied. This result agrees very well with the values reported by Ali and coworkers in their study on the synthesis of γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles from the hydrothermal method, in which crystal size values from 4 to 6.5 nm were determined for the aluminum oxide nanoparticles prepared from aluminum nitrate precursor and with a calcination temperature of 600 °C [32].

Table 1.

Crystal size of the Al2O3 nanoparticles.

4. Conclusions

The main objective of this study was to develop a green synthesis route for aluminum oxide (Al2O3) nanoparticles using lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) extract and to evaluate the influence of different aluminum precursors and thermal treatments on their structural and morphological properties. The aluminum precursor and thermal treatment significantly influenced the size and crystal structure of the Al2O3 nanoparticles prepared by green synthesis using lemongrass extract. In particular, the samples derived from AlCl3 exhibited more defined diffraction peaks and a more uniform morphology, as compared to those obtained from the Al(NO3)3 precursor. These observations highlight that the choice of aluminum precursor not only affects crystallinity and particle uniformity, but also governs the interaction between Al3+ ions and the bioactive metabolites in the lemongrass extract, influencing nucleation, growth, and stabilization processes. Consequently, precursor selection is a key factor for optimizing the structural quality and performance of γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles synthesized via green routes.

Additionally, the presence of bioactive metabolites in the lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) extract (phenols, flavonoids, and aldehydes) might have reinforced these differences. The Cl− ions released from the aluminum chloride precursor appear to play an active role in stabilizing the transient complex between Al+3 and the functional groups of the extract, thereby favoring the formation of more stable nanoparticles with higher crystallinity. In contrast, the NO3− ions from the aluminum nitrate precursor appear to compete with the bioactive metabolites for coordination to aluminum, thereby limiting the efficiency of the stabilization process and contributing to the irregular shape and poor crystallinity of the aluminum oxide nanoparticles. These results are consistent with reports on the synthesis of boehmite and alumina, which show that the type of precursor directly affects the structure and properties of the nanoparticles [33,34,35]. In conclusion, the AlCl3 precursor combined with the lemongrass extract provided a better route for synthesizing γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles by promoting crystallization at 700 °C, resulting in a lower energy cost than the thermal treatments at 900 °C required for the alumina nanoparticles obtained with the Al(NO3)3 reagent.

The green γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles synthesized in this study show promising potential for use as functional additives in advanced coating systems. Beyond their capacity to enhance wear resistance and UV protection, these nanomaterials represent a prospective solution for future applications in asbestos-cement products and protective coatings designed to reduce fiber release from aging asbestos surfaces. Such applications are particularly relevant in developing countries—such as Colombia—where asbestos has been recently banned, and efforts are underway to identify effective mitigation strategies that limit environmental dispersion while improving thermal comfort in housing. Accordingly, future research by the authors will focus on exploring the integration of these green-synthesized alumina nanoparticles into asbestos-cement rehabilitation systems and related coating technologies to improve thermal comfort.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H. and M.S.; methodology, M.C., L.T. and D.M.-B.; validation, A.H. and M.S.; formal analysis, M.C. and L.T.; investigation, M.C., L.T. and D.M.-B.; resources, M.S.; data curation, M.C. and D.M.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C., L.T. and D.M.-B.; writing—review and editing, A.H. and M.S.; supervision, A.H. and M.S.; project administration, M.S.; funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for funding from the University of Cartagena through the project “Plan de Fortalecimiento del grupo NIPAC. Acta No. 008-2023”. Furthermore, this article forms part of the outcomes of the project “Formulation of a Comprehensive Strategy to Reduce the Impact of Asbestos on Public and Environmental Health in the Department of Bolívar”, funded by the General System of Royalties of the Republic of Colombia (SGR), under project code BPIN 2020000100366. The project was implemented by the University of Cartagena in partnership with the Asbestos-Free Colombia Foundation (FundClas).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kam, O.R.; Bakouan, C.; Zongo, I.; Guel, B. Removal of Thallium from Aqueous Solutions by Adsorption onto Alumina Nanoparticles. Processes 2022, 10, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masemola, C.M.; Moloto, N.; Tetana, Z.; Linganiso, L.Z.; Motaung, T.E.; Linganiso-Dziike, E.C. Advances in Polyaniline-Based Composites for Room-Temperature Chemiresistor Gas Sensors. Processes 2025, 13, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiker, M.E.M. Eco-Environmentally Friendly Green Synthesis and Characterization of Aluminum Oxide Nanoparticles Using Leaf Extract of Mentha Pulegium. Int. J. Chem. Biochem. Sci. 2024, 25, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghotekar, S. Plant extract mediated biosynthesis of Al2O3 nanoparticles—A review on plant parts involved, characterization and applications. Nanochem. Res. 2019, 4, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phrompet, C.; Sriwong, C.; Ruttanapun, C. Mechanical, dielectric, thermal and antibacterial properties of reduced graphene oxide (rGO)-nanosized C3AH6 cement nanocomposites for smart cement-based materials. Compos. Part B 2019, 175, 107128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, A.; Gopikishan, S.; Mahapatra, S.; Barhai, P.; Das, A.; Banerjee, I. Bactericidal efficiency of nanostructured Al–O/Ti–O composite thin films prepared by dual magnetron reactive co-sputtering technique. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 4681–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Zhou, R.; Hu, M.; Wu, X.; Du, Y.; Ge, Y.; Yang, C.; Jiang, B.; Yang, R. Self-cleaning Al2O3-PTFE composite coatings on aluminum alloy with enhanced superhydrophobicity, corrosion and wear resistance. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 35483–35495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Xu, T.; Li, C.; Xu, D.; Liu, G.; Zhu, H.; Guo, Y. PES/Fe3S4@Al2O3 self-cleaning membrane with rapid catalysis for effective emulsion separation and dye degradation. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 194, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, M.; Mansour, A.T.; Abdelwahab, A.M.; Alprol, A.E. Metal Oxide Nanoparticles’ Green Synthesis by Plants: Prospects in Phyto- and Bioremediation and Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Pollutants. Processes 2023, 11, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligor, O.; Mocan, A.; Moldovan, C.; Locatelli, M.; Crișan, G.; Ferreira, I.C. Enzyme-assisted extractions of polyphenols—A comprehensive review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutradhar, P.; Debnath, N.; Saha, M. Microwave-assisted rapid synthesis of alumina nanoparticles using tea, coffee and triphala extracts. Adv. Manuf. 2013, 1, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.A.; Khan, H.M.; Alzohairy, M.A.; Jalal, M.; Ali, S.G.; Pal, R.; Musarrat, J. Green synthesis of Al2O3 nanoparticles and their bactericidal potential against clinical isolates of multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 31, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.N.; Bdewi, S.F.; Alshammary, E.T.; Hammad, R.T. Characterization of Alumina Nanoparticles Prepared Via Green Synthesis Method. J. Univ. Anbar Pure Sci. 2023, 17, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Bai, Y.; Xu, M.; Gao, Y.; Yan, P.; Xu, H. Mechanistic Study of the Influence of Reactant Type and Addition Sequence on the Microscopic Morphology of α-Al2O3. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, H. Green Synthesis and Particle Size Control of High-Purity Alumina Based on Hydrolysis of Alkyl Aluminum. Materials 2025, 18, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, R.A.; Herrera, A.P.; Maestre, D.; Cremades, A. Fe-TiO2 Nanoparticles Synthesized by Green Chemistry for Potential Application in Waste Water Photocatalytic Treatment. J. Nanotechnol. 2019, 2019, 4571848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, R.; Patiño-Ruiz, D.; Herrera, A. Preparation of modified paints with nano-structured additives and its potential applications. Nanomater. Nanotechnol. 2020, 10, 1847980420909188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, A.H.; Laouini, S.E.; Hemmami, H.; Bouafia, A.; Gherbi, M.T.; Ben Amor, I.; Hasan, G.G.; Abdullah, M.M.S.; Trzepieciński, T.; Abdullah, J.A.A. Eco-Friendly Synthesis of Al2O3 Nanoparticles: Comprehensive Characterization Properties, Mechanics, and Photocatalytic Dye Adsorption Study. Coatings 2024, 14, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, S.; Guan, Z.; Ofoegbu, P.C.; Clubb, P.; Rico, C.; He, F.; Hong, J. Green synthesis of nanoparticles: Current developments and limitations. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 26, 102336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rojas, M.d.P.; Bustos-Terrones, V.; Díaz-Cárdenas, M.Y.; Vázquez-Vélez, E.; Martínez, H. Life Cycle Assessment of Green Synthesis of TiO2 Nanoparticles vs. Chemical Synthesis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abady, M.M.; Mohammed, D.M.; Soliman, T.N.; Shalaby, R.A.; Sakr, F.A. Sustainable synthesis of nanomaterials using different renewable sources. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2025, 49, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Byati, M.K.A.A.; Al-Duhaidahawi, A.M.J. Synthesis of Aluminum Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Applications in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells as a Clean Energy. Biomed. Chem. Sci. 2023, 2, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandgaonker, P.; Kulkarni, G.; Gaikwad, S.; Rajbhoj, A. Synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles by electrochemical method and their antibacterial application. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 1815–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Han, R.; Li, F. Synthesis of mesoporous γ-alumina and its catalytic performance in dichloropropanol cyclization. Quim. Nova 2019, 42, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, P.; Viruthagiri, G.; Mugundan, S.; Shanmugam, N. Structural, optical and morphological analyses of pristine titanium di-oxide nanoparticles—Synthesized via sol–gel route. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 117, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Abbas, Y.; Zuhra, Z.; Butler, I.S. Synthesis of γ-alumina (Al2O3) nanoparticles and their potential for use as an adsorbent in the removal of methylene blue dye from industrial wastewater. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suaebah, E.; Yunata, E.E.; Wijaya, A.S.N. The sintering temperature effect of Alumina (Al2O3) ceramic using the sol-gel method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2900, 012044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyasree, D.; Kiranmayi, P.; Kumar, R. Synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of aluminium oxide nanoparticles. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 10, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khine, E.E.; Kaptay, G. Identification of Nano-Metal Oxides That Can Be Synthesized by Precipitation-Calcination Method Reacting Their Chloride Solutions with NaOH Solution and Their Application for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Air—A Thermodynamic Analysis. Materials 2023, 16, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, D.; Shen, J.; Chen, J.; Wu, C.; Qu, Z.; Luo, K.; Meng, Z.; Li, Y. Study on the Synthesis of High-Purity γ-Phase Mesoporous Alumina with Excellent CO2 Adsorption Performance via a Simple Method Using Industrial Aluminum Oxide as Raw Material. Materials 2021, 14, 5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, D.; Han, X.; Bao, X.; Frandsen, W.; Wang, D.; Su, D. Hydrothermal synthesis of microscale boehmite and gamma nanoleaves alumina. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 1297–1301. Available online: www.fhi-berlin.mpg.de/ac (accessed on 27 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Buwono, H.P.; Adiwidodo, S.; Wicaksono, H.; Firmansyah, H.I. Hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of nano-particles γ-Al2O3. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1073, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Qin, Q.; Wan, Y.; Zhou, F.; Chen, Y.-B.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.-X. Effect of anions on preparation of ultrafine α-Al2O3 powder. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 2007, 14, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahifar, M.M.; Hidaryan, M.; Jafari, P. The role anions on the synthesis of AlOOH nanoparticles using simple solvothermal method. Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidr. 2018, 57, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, R.R.; Santoyo, V.R.; Sánchez, C.D.M.; Rosales, M.M. Effect of aluminum precursor on physicochemical properties of Al2O3 by hydrolysis/precipitation method. Nova Sci. 2018, 10, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).