Valorization of Green Arabica Coffee Coproducts for Mannanase Production and Carbohydrate Recovery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Sample Preparation

2.1.2. Elementary Organic Analysis (CHNSO) in the Best Carbon Source

2.1.3. Microorganism

2.2. Enzyme Production

2.2.1. Preliminary Growth Medium Composition and Cultivation

2.2.2. Determination of Mannanase Activity

2.2.3. Statistical Experimental Design for Mannanase Production

Plackett–Burman Design (PB)

Central Composite Rotatable Design (CCRD)

2.2.4. Determination of β-mannosidase Activity

2.3. Hydrolysis Experiments of Coffee Beans

2.3.1. Enzymatic Hydrolysis

2.3.2. Acid Hydrolysis

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Enzyme Production

3.1.1. Influence of Carbon Source Arrangement

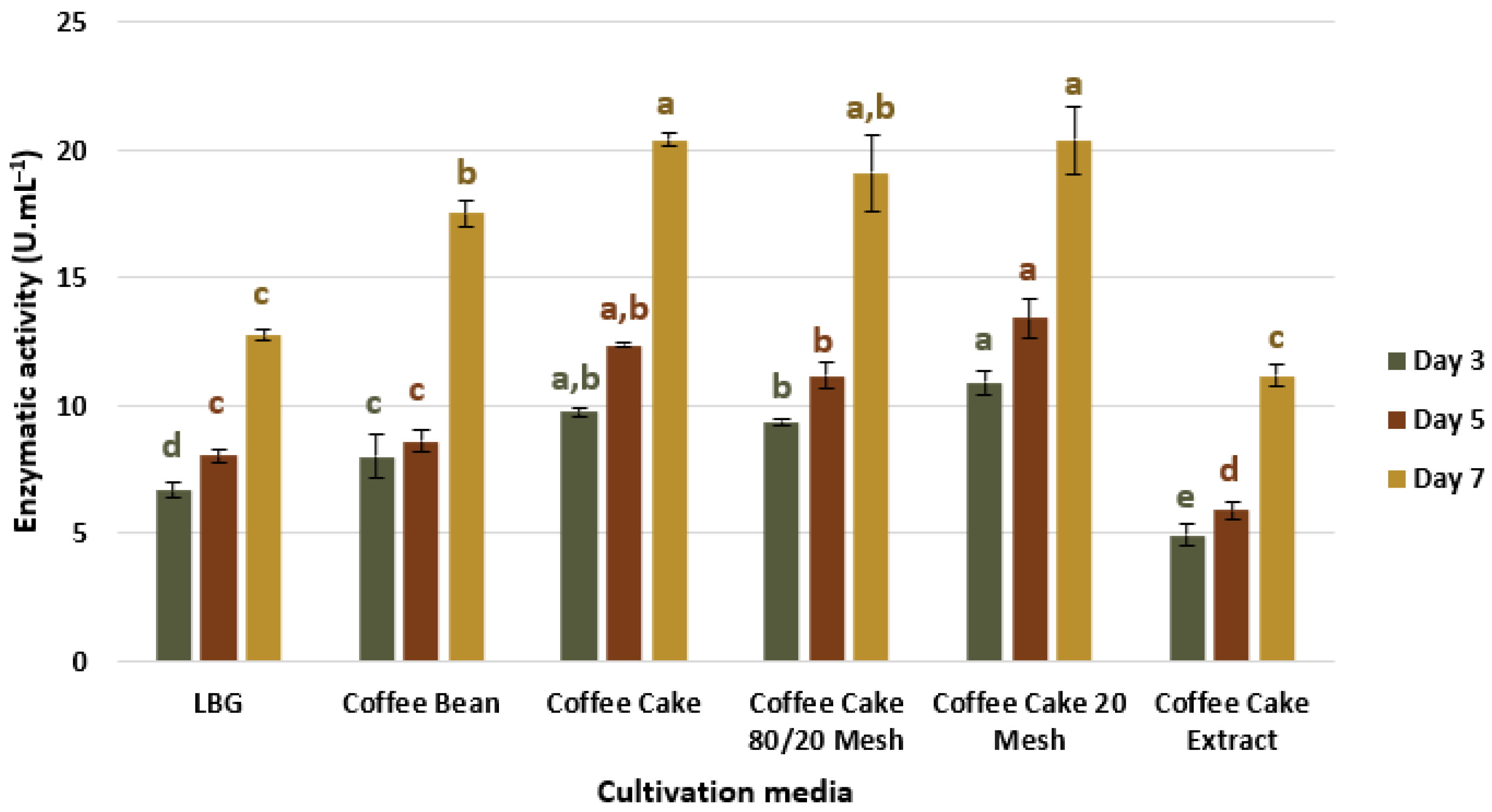

3.1.2. Influence of Cultivation Time

3.1.3. Validation of Preliminary Tests

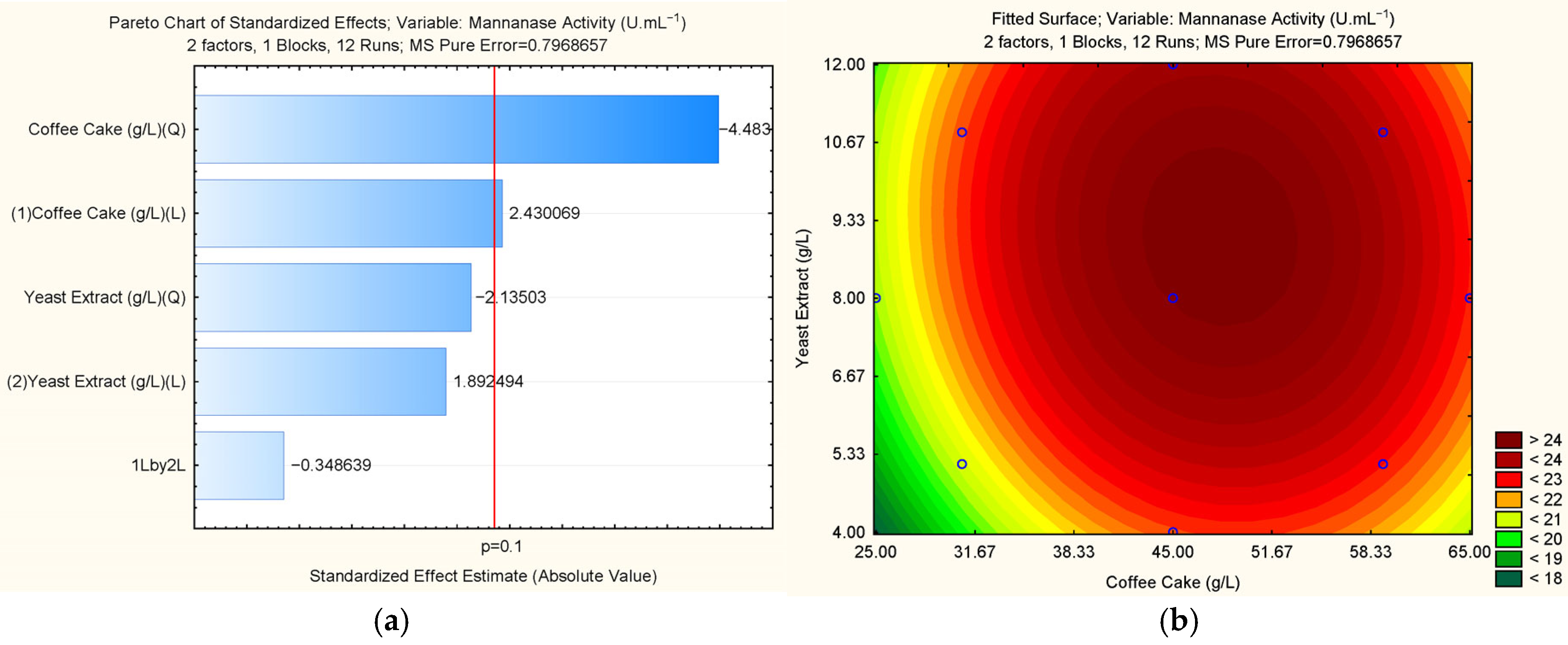

3.1.4. Statistical Experimental Design

3.1.5. Determination of β-mannosidase Enzyme Activity

3.2. Hydrolysis Experiments of Coffee Beans

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferreira-Leitão, V.; Gottschalk, L.M.F.; Ferrara, M.A.; Nepomuceno, A.L.; Molinari, H.B.C.; Bon, E.P.d.S. Biomass Residues in Brazil: Availability and Potential Uses. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2010, 1, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.M.; Pereira, N. Produção, propriedades e aplicação de celulases na hidrólise de resíduos agroindustriais. Quim. Nova 2010, 33, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basmak, S.; Turhan, I. Production of β-Mannanase, Inulinase, and Oligosaccharides from Coffee Wastes and Extracts. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261, 129798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, V.d.N.e.S.; Batista, J.M.d.S.; Nascimento, T.P.; da Cunha, M.N.C.; Leite, A.C.L. Resíduos Agroindustriais: Uma Alternativa Promissora e Sustentável Na Produção de Enzimas Por Microrganismos. In Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação: Do Campo a Mesa, Proceedings of the Congresso Internacional da Agroindústria, Virtual Event, 25 September 2020; Editora IIDV: Recife, Brazil; pp. 1–16.

- Berto, P.J.; Ferraz, D.; Rebelatto, D.A.d.N. The Circular Economy, Bioeconomy, and Green Investments: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Rev. Gestão Produção Operações Sist. 2022, 17, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The 17 Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- ICO. Beyond Coffee: Towards a Circular Coffee Economy; International Coffee Organization: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kalschne, D.L.; Viegas, M.C.; De Conti, A.J.; Corso, M.P.; Benassi, M.d.T. Steam Pressure Treatment of Defective Coffea Canephora Beans Improves the Volatile Profile and Sensory Acceptance of Roasted Coffee Blends. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingel, T.; Kremer, J.I.; Gottstein, V.; De Rezende, T.R.; Schwarz, S.; Lachenmeier, D.W. A Review of Coffee By-Products Including Leaf, Flower, Cherry, Husk, Silver Skin, and Spent Grounds as Novel Foods within the European Union. Foods 2020, 9, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.C.; Teixeira, R.S.S.; de Rezende, C.M. Extrusion Pretreatment of Green Arabica Coffee Beans for Lipid Enhance Extraction. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 221, 119318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongsiriyakul, K.; Wongsurakul, P.; Kiatkittipong, W.; Premashthira, A.; Kuldilok, K.; Najdanovic-Visak, V.; Adhikari, S.; Cognet, P.; Kida, T.; Assabumrungrat, S. Upcycling Coffee Waste: Key Industrial Activities for Advancing Circular Economy and Overcoming Commercialization Challenges. Processes 2024, 12, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, O.L.; Tsukui, A.; Garrett, R.; Miguez Rocha-Leão, M.H.; Piler Carvalho, C.W.; Pereira Freitas, S.; Moraes de Rezende, C.; Simões Larraz Ferreira, M. Production of Bioactive Films of Carboxymethyl Cellulose Enriched with Green Coffee Oil and Its Residues. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 146, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franca, A.S.; Oliveira, L.S.; Mendonça, J.C.F.; Silva, X.A. Physical and Chemical Attributes of Defective Crude and Roasted Coffee Beans. Food Chem. 2005, 90, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, A.T.; Chun, B.S. Influence of Pretreatment and Modifiers on Subcritical Water Liquefaction of Spent Coffee Grounds: A Green Waste Valorization Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 3719–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento. Produção de Café Cresce 8,2% Em 2023 e Chega a 55,1 Milhões De. Available online: https://www.conab.gov.br/ultimas-noticias/5323-producao-de-cafe-cresce-8-2-em-2023-e-chega-a-55-1-milhoes-de-sacas (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Silva, A.C.R.; da Silva, C.C.; Garrett, R.; de Rezende, C.M. Comprehensive Lipid Analysis of Green Arabica Coffee Beans by LC-HRMS/MS. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redgwell, R.; Fischer, M. Coffee Carbohydrates. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 18, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Chen, Q.; Wei, C.; Hu, R.; Long, Y.; Zong, Y.; Chu, Z. Comparison of the Effect of Extraction Methods on the Quality of Green Coffee Oil from Arabica Coffee Beans: Lipid Yield, Fatty Acid Composition, Bioactive Components, and Antioxidant Activity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 74, 105578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farah, A. Coffee Constituents. In Coffee: Emerging Health Effects and Disease Prevention; Chu, Y.-F., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Franca, A.S.; Oliveira, L.S. Chemistry of defective coffee beans. In Food Chemistry Research Developments; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2008; p. 234. ISBN 9781604563030. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan, M.F. Cold Pressed Oils: Green Technology, Bioactive Compounds, Functionality, and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Arya, M.; Rao, L.J.M. An Impression of Coffee Carbohydrates. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2007, 47, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, G.; Arya, S.K. Mannans: An Overview of Properties and Application in Food Products. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 119, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, J.A.; Lima, G.D.S.; Dos Santos, G.F.; Lyra, F.H.; Da Silva-Hughes, A.F.; Gonçalves, F.A.G. Filamentous Fungi and Chemistry: Old Friends, New Allies. Rev. Virtual Quim. 2017, 9, 2351–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, P.K.; Kapoor, M. Production, Properties, and Applications of Endo-β-Mannanases. Biotechnol. Adv. 2017, 35, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, H.; Shi, Y.; Yan, Q.; You, X.; Jiang, Z. Preparation, Characterization, and Prebiotic Activity of Manno-Oligosaccharides Produced from Cassia Gum by a Glycoside Hydrolase Family 134 β-Mannanase. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 125709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, U.K.; Kango, N. Characteristics and Bioactive Properties of Mannooligosaccharides Derived from Agro-Waste Mannans. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mary, P.R.; Prashanth, K.V.H.; Vasu, P.; Kapoor, M. Structural Diversity and Prebiotic Potential of Short Chain β-Manno-Oligosaccharides Generated from Guar Gum by Endo-β-Mannanase (ManB-1601). Carbohydr. Res. 2019, 486, 107822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, S.A.A.; Mostafa, F.A.; Ahmed, S.A.; Zaki, E.R.; Salama, W.H.; Abdel Wahab, W.A. Date Nawah Powder as a Promising Waste for β-Mannanase Production from a New Isolate Aspergillus niger MSSFW, Statistically Improving Production and Enzymatic Characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cairns, T.C.; Nai, C.; Meyer, V. How a Fungus Shapes Biotechnology: 100 Years of Aspergillus niger Research. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2018, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntana, F.; Mortensen, U.H.; Sarazin, C.; Figge, R. Aspergillus: A Powerful Protein Production Platform. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, M.K.; Teixeira, R.S.S.; da Silva, A.S.; Fujimoto, M.D.; Melo, P.A.; Secchi, A.R.; Bon, E.P.d.S. Continuous Pretreatment of Sugarcane Biomass Using a Twin-Screw Extruder. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 97, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasheun, D.O.; de Oliveira, R.A.; Bon, E.P.S.; da Silva, A.S.A.; Teixeira, R.S.S.; Ferreira-Leitão, V.S. Dry Extrusion Pretreatment of Cassava Starch Aided by Sugarcane Bagasse for Improved Starch Saccharification. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 285, 119256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, A.; Mandal, A. Production and Optimization of Xylanase Enzyme from Bacillus Cereus BSA1 by Submerged Fermentation. Int. Res. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2024, 9. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385899118_Production_and_Optimization_of_Xylanase_Enzyme_from_Bacillus_cereus_BSA1_by_Submerged_Fermentation (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Blibech, M.; Chaari, F.; Bhiri, F.; Dammak, I.; Ghorbel, R.E.; Chaabouni, S.E. Production of Manno-Oligosaccharides from Locust Bean Gum Using Immobilized Penicillium Occitanis Mannanase. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2011, 73, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilmeli, S.; Doruk, T.; Könen-Adıgüzel, S.; Adıgüzel, A.O. A Thermostable and Acidophilic Mannanase from Bacillus Mojavensis: Its Sustainable Production Using Spent Coffee Grounds, Characterization, and Application in Grape Juice Processing. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022, 14, 3811–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaro, C.P.; Baraldi, I.J.; Casciatori, F.P.; Farinas, C.S. β-Mannanase Production Using Coffee Industry Waste for Application in Soluble Coffee Processing. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.A.; Kalthoum Khattab, O.H.; Nour, S.A.; Awad, G.E.A.; Abo-Elnasr, A.A.; Hashem, A.M. A Thermodynamic Study of Partially-Purified Penicillium Humicola β-Mannanase Produced by Statistical Optimization. Jordan J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 12, 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R.; Brand, A.L.; Tinoco, N.; Freitas, S.; Rezende, C. Bioactive Diterpenes and Serotonin Amides in Cold-Pressed Green Coffee Oil (Coffea arabica L.). J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2023, 35, 20230131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, O.C.; Tupi, L.P.C.; Teixeira, R.S.S. Prospecção de Fungos Do Gênero Aspergillus Produtores de Mananases; Final Course Work; Universidade do Grande Rio: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Karahalil, E.; Germeç, M.; Turhan, I. β-Mannanase Production and Kinetic Modeling from Carob Extract by Using Recombinant Aspergillus sojae. Biotechnol. Prog. 2019, 35, e2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, S.N.; Ramanan, R.N.; Mohamad, R.; Ariff, A.B. Improved Mannan-Degrading Enzymes’ Production by Aspergillus niger through Medium Optimization. New Biotechnol. 2011, 28, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozturk, B.; Cekmecelioglu, D.; Ogel, Z.B. Optimal Conditions for Enhanced β-Mannanase Production by Recombinant Aspergillus sojae. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2010, 64, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatmaz, E.; Germec, M.; Karahalil, E.; Turhan, I. Enhancing β-Mannanase Production by Controlling Fungal Morphology in the Bioreactor with Microparticle Addition. Food Bioprod. Process. 2020, 121, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmazer, C.; Gürler, H.N.; Erkan, S.B.; Ozcan, A.; Hosta Yavuz, G.; Germec, M.; Yatmaz, E.; Turhan, I. Optimization of Mannooligosaccharides Production from Different Hydrocolloids via Response Surface Methodology Using a Recombinant Aspergillus sojae β-Mannanase Produced in the Microparticle-Enhanced Large-Scale Stirred Tank Bioreactor. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e14916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalbrand, H.; Siika-Aho, M.; Tenkanen, M.; Viikari, L. Purification and Characterization of Two B-Mannanases from Trichoderma Reesei. J. Biotechnol. 1993, 29, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, R.S.S.; Da Silva, A.S.; Ferreira-Leitão, V.S.; Bon, E.P.d.S. Amino Acids Interference on the Quantification of Reducing Sugars by the 3,5-Dinitrosalicylic Acid Assay Mislead Carbohydrase Activity Measurements. Carbohydr. Res. 2012, 363, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, L.M.F.; Paredes, R.D.S.; Teixeira, R.S.S.; Da Silva, A.S.; Bon, E.P.D.S. Efficient Production of Lignocellulolytic Enzymes Xylanase, b-Xylosidase, Ferulic Acid Esterase and b-Glucosidase by the Mutant Strain Aspergillus awamori 2B.361 U2/1. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2013, 44, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piza, F.A.T.; Siloto, A.P.; Carvalho, C.V.; Franco, T.T. Production, Characterization and purification of chitosanase from Bacillus Cereus. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 1999, 16, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Aziz, S.; Ong, L.G.A.; Hassan, M.A.; Karim, M.I.A. Process Parameters Optimisation of Mannanase Production from Aspergillus niger FTCC 5003 Using Palm Kernel Cake as Carbon Source. Asian J. Biochem. 2008, 3, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lin, T.C.; Chen, C. Enhanced Mannanase Production by Submerged Culture of Aspergillus niger NCH-189 Using Defatted Copra Based Media. Process Biochem. 2004, 39, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.S.; Puri, N.; Sharma, P.; Gupta, N. Mannanases: Microbial Sources, Production, Properties and Potential Biotechnological Applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 1817–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandl, J.; Aguilar-Pontes, M.V.; Schäpe, P.; Noerregaard, A.; Arvas, M.; Ram, A.F.J.; Meyer, V.; Tsang, A.; de Vries, R.P.; Andersen, M.R. A Community-Driven Reconstruction of the Aspergillus niger Metabolic Network. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2018, 5, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-M.; Gilmore, D.F. Statistical Experimental Design for Bioprocess Modeling and Optimization Analysis. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2006, 135, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.I.; Iemma, A.F. Planejamento de Experimentos e Otimização de Processos: Uma Estratégia Sequencial de Planejamentos, 3rd ed.; Cárita Editora: Campinas, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Agu, K.C.; Okafor, F.C.; Amadi, O.C.; Mbachu, A.E.; Awah, N.S.; Odili, L.C. Production of Mannanase Enzyme Using Aspergillus Spp. Isolated from Decaying Palm Press Cake. Sch. Acad. J. Biosci. 2014, 2, 863–870. [Google Scholar]

- Fliedrová, B.; Gerstorferová, D.; Křen, V.; Weignerová, L. Production of Aspergillus niger β-Mannosidase in Pichia Pastoris. Protein Expr. Purif. 2012, 85, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.R.S.; Filho, E.X.F. An Overview of Mannan Structure and Mannan-Degrading Enzyme Systems. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 79, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniyan, S.; Prema, P. Cellulase-Free Xylanases from Bacillus and Other Microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000, 183, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, N.; Srivastava, M.; Mishra, P.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Molina, G.; Rodriguez-Couto, S.; Manikanta, A.; Ramteke, P.W. Applications of Fungal Cellulases in Biofuel Production: Advances and Limitations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 2379–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, P.S.; Madhava Naidu, M. Sustainable Management of Coffee Industry By-Products and Value Addition—A Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 66, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotou, G.; Kekos, D.; Macris, B.J.; Christakopoulos, P. Production of Cellulolytic and Xylanolytic Enzymes by Fusarium Oxysporum Grown on Corn Stover in Solid State Fermentation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2003, 18, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, K.; Nieminen, K.; Ekholm, F.S.; Poláková, M.; Roslund, M.U.; Saloranta, T.; Leino, R.; Savolainen, J. Evaluation of Immunostimulatory Activities of Synthetic Mannose-Containing Structures Mimicking the β-(1→2)-Linked Cell Wall Mannans of Candida Albicans. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012, 19, 1889–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.M.; Ali, H.I.; Anwar, M.M.; Mohamed, N.A.; Soliman, A.M. Synthesis, Antitumor Activity and Molecular Docking Study of Novel Sulfonamide-Schiff’s Bases, Thiazolidinones, Benzothiazinones and Their C-Nucleoside Derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.-E.; Zhao, J.-F.; Xiong, F.-J.; Xie, B.; Zhang, P. An Improved Synthesis of a Key Intermediate for (+)-Biotin from D-Mannose. Carbohydr. Res. 2007, 342, 2461–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.K.; Hwang, J.S. Selective Hydrogenation of D-Mannose to d-Mannitol Using NiO-Modified TiO2 (NiO-TiO2) Supported Ruthenium Catalyst. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2013, 453, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipigh, A.A.; Rojo, E.M.; Pila, A.N.; Bolado, S. Fractional Recovery of Proteins and Carbohydrates from Secondary Sludge from Urban Wastewater Treatment Plants. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2024, 20, 100686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, I.J.; Giordano, R.L.C.; Zangirolami, T.C. Enzymatic Hydrolysis as an Environmentally Friendly Process Compared to Thermal Hydrolysis for Instant Coffee Production. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 33, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.L.; Sousa, R., Jr.; Rodríguez-Zúñiga, U.F.; Suarez, C.A.G.; Rodrigues, D.S.; Giordano, R.C.; Giordano, R.L.C. Kinetic Study of the Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Sugarcane Bagasse. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2013, 30, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenio, M.E.; Domínguez, G.; Molina-Guijarro, J.M.; Hernández, M.; Arias, M.E.; Ibarra, D. Boosting Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Steam-Pretreated Softwood by Laccase and Endo-β-Mannanase Enzymes from Streptomyces Ipomoeae CECT 3341. Wood Sci Technol 2023, 57, 965–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasheun, D.O.; da Silva, A.S.; Teixeira, R.S.S.; Ferreira-Leitão, V.S. Enhancing Methane Production from Cassava Starch: The Potential of Extrusion Pretreatment in Single-Stage and Two-Stage Anaerobic Digestion. Fuel 2023, 366, 131406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, T.; Liang, F.; Fang, G.; Jiao, J.; Huang, C.; Tian, Q.; Zhu, B.; Deng, Y.; Han, S.; Zhou, X. An Integrated Pretreatment Strategy for Enhancing Enzymatic Hydrolysis Efficiency of Poplar: Hydrothermal Treatment Followed by a Twin-Screw Extrusion. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 211, 118169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, A.F.; Miguez, I.S.; Silva, J.P.R.B.; da Silva, A.S.A. High Concentration and Yield Production of Mannose from Açaí (Euterpe Oleracea Mart.) Seeds via Mannanase-Catalyzed Hydrolysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbe, M.; Wallberg, O. Pretreatment for Biorefineries: A Review of Common Methods for Efficient Utilisation of Lignocellulosic Materials. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Q.A.; Cho, E.; Trinh, L.T.P.; Jeong, J.; Bae, H.-J. Development of an Integrated Process to Produce D-Mannose and Bioethanol from Coffee Residue Waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Concentration (g·L−1) |

|---|---|

| Carbon Source * | 30.0 |

| Yeast extract | 4.0 |

| Potassium phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) | 0.5 |

| CaCl2·2H2O | 0.05 |

| MgSO4·7H2O | 0.5 |

| Al2O3 | 1.0 |

| ID | Independent Factor (g·L−1) | Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| X1 | Coffee cake | 20 | 30 | 40 |

| X2 | Yeast extract | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| X3 | Phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.75 |

| X4 | CaCl2·2H2O | 0 | 0.005 | 0.1 |

| X5 | MgSO4·7H2O | 0 | 0.5 | 1 |

| X6 | Al2O3 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| ID | Independent Factor (g·L−1) | Level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1.41 | −1 | 0 | +1 | +1.41 | ||

| Z1 | Coffee cake | 25 | 30.82 | 45 | 59.18 | 65 |

| Z2 | Yeast extract | 4 | 5.16 | 8 | 10.84 | 12 |

| Carbon Source | %C | %H | %N | %S | %O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LBG | 38.85 ± 0.12 a | 6.64 ± 0.04 a | 0.87 ± 0.01 b | 0.15 ± 0.03 a | 53.49 ± 0.17 a |

| Coffee cake | 43.42 ± 0.05 a | 6.36 ± 0.00 b | 2.61 ± 0.00 a | 0.23 ± 0.01 a | 47.38 ± 0.04 a |

| ID | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | X6 | VI1 | VI2 | VI3 | VI4 | VI5 | Mannanase Activity (U·mL−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 21.87 ± 1.64 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 21.49 ± 0.24 |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 19.42 ± 0.61 |

| 4 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 20.44 ± 0.41 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 21.67 ± 0.77 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 20.77 ± 0.93 |

| 7 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | 19.96 ± 0.81 |

| 8 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | −1 | 13.56 ± 0.83 |

| 9 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 19.53 ± 1.34 |

| 10 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 20.79 ± 0.43 |

| 11 | −1 | 1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | −1 | 1 | 1 | 20.65 ± 0.30 |

| 12 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 14.52 ± 0.22 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.74 ± 0.14 |

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.57 ± 0.14 |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.20 ± 0.17 |

| 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.52 ± 0.07 |

| ID | Z1 | Z2 | Mannanase Activity (U·mL−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −1 | −1 | 21.01 ± 0.27 |

| 2 | 1 | −1 | 22.97 ± 0.45 |

| 3 | −1 | 1 | 21.30 ± 0.18 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 22.65 ± 0.27 |

| 5 | −1.41 | 0 | 21.07 ± 0.59 |

| 6 | 1.41 | 0 | 23.07 ± 0.43 |

| 7 | 0 | −1.41 | 22.02 ± 0.61 |

| 8 | 0 | 1.41 | 25.43 ± 0.84 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 25.63 ± 0.48 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 25.33 ± 0.30 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 23.64 ± 0.29 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 24.50 ± 0.52 |

| Samples | Monosaccharides (g·100 g−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Galactose | Arabinose | Mannose + Fructose | |

| Acid hydrolysis | ||||

| Healthy beans | 6.56 ± 0.21 | 13.53 ± 0.70 | 1.91 ± 0.38 | 19.69 ± 4.06 |

| Defective beans | 5.52 ± 0.53 | 12.59 ± 0.76 | 1.68 ± 0.13 | 18.50 ± 2.07 |

| Enzymatic hydrolysis (24 h) | ||||

| Healthy beans | 5.01 ± 0.33 | 0.18 ± 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.66 ± 0.01 |

| Defective beans | 3.96 ± 0.39 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.00 | 4.81 ± 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, R.C.; Barros, L.J.B.d.M.d.; Menezes, L.B.d.; Rezende, C.M.d.; Silva, A.S.d.; Bon, E.P.d.S.; Teixeira, R.S.S. Valorization of Green Arabica Coffee Coproducts for Mannanase Production and Carbohydrate Recovery. Processes 2025, 13, 3874. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123874

Ribeiro RC, Barros LJBdMd, Menezes LBd, Rezende CMd, Silva ASd, Bon EPdS, Teixeira RSS. Valorization of Green Arabica Coffee Coproducts for Mannanase Production and Carbohydrate Recovery. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3874. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123874

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Raquel Coldibelli, Leonardo João Bicalho de Moraes de Barros, Laura Braga de Menezes, Claudia Moraes de Rezende, Ayla Sant’Ana da Silva, Elba Pinto da Silva Bon, and Ricardo Sposina Sobral Teixeira. 2025. "Valorization of Green Arabica Coffee Coproducts for Mannanase Production and Carbohydrate Recovery" Processes 13, no. 12: 3874. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123874

APA StyleRibeiro, R. C., Barros, L. J. B. d. M. d., Menezes, L. B. d., Rezende, C. M. d., Silva, A. S. d., Bon, E. P. d. S., & Teixeira, R. S. S. (2025). Valorization of Green Arabica Coffee Coproducts for Mannanase Production and Carbohydrate Recovery. Processes, 13(12), 3874. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123874