GCML: A Short-Term Load Forecasting Framework for Distributed User Groups Based on Clustering and Multi-Task Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- This paper proposes a novel load forecasting model, which forecasts the short-term load by segmenting electricity user groups and jointly optimizing multiple forecasting tasks, thereby improving prediction accuracy on the demand side of the electricity market.

- (2)

- An improved multi-task learning architecture is proposed to capture correlations between distributed user groups. It uses an encoder-only approach to extract common features across clusters, introduces dynamic weighting, and assigns independent task heads for multiple forecasting tasks, overcoming the limitations of single-task modeling.

- (3)

- The filter-attention mechanism and Inception convolution module are integrated into an encoder, significantly enhancing the model’s ability to capture local patterns and fuse multi-scale features of load data.

- (4)

- We conducted experiments on publicly available datasets, and the experimental results show that GCML outperforms existing baseline models.

2. Related Work

2.1. Clustering-Based Load Forecasting Methods

2.2. Multi-Task Learning Methods for Time-Series Forecasting

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Definition

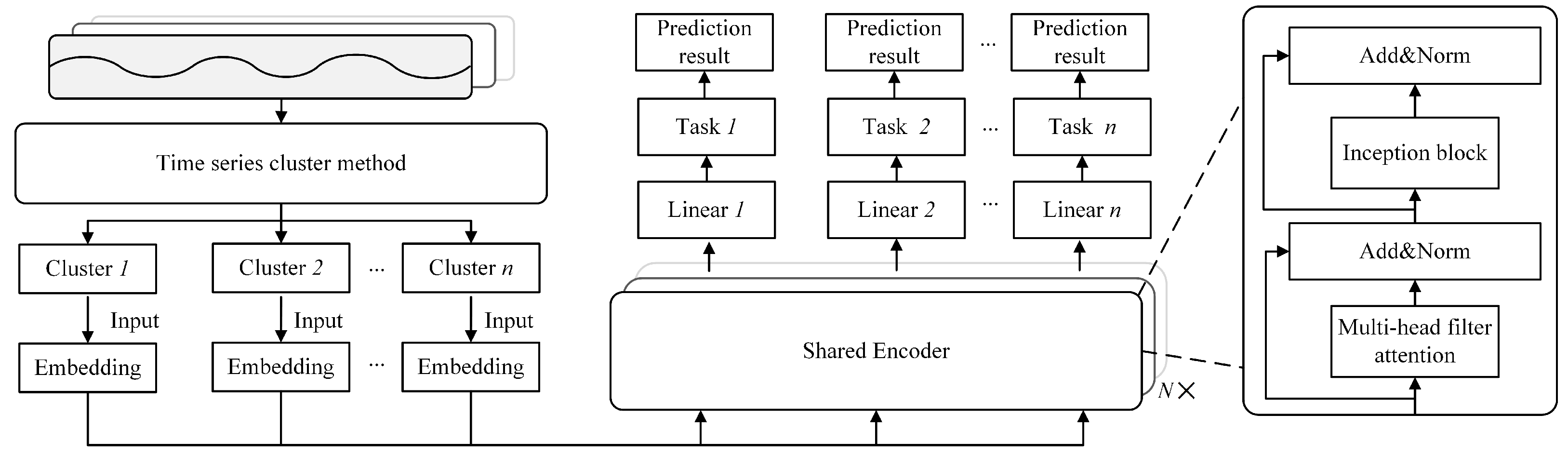

3.2. Processing Model

3.3. Clustering for Distributed Users

3.4. Multi-Task Learning

3.5. Encoder-Only-Based Shared Encoder Architecture

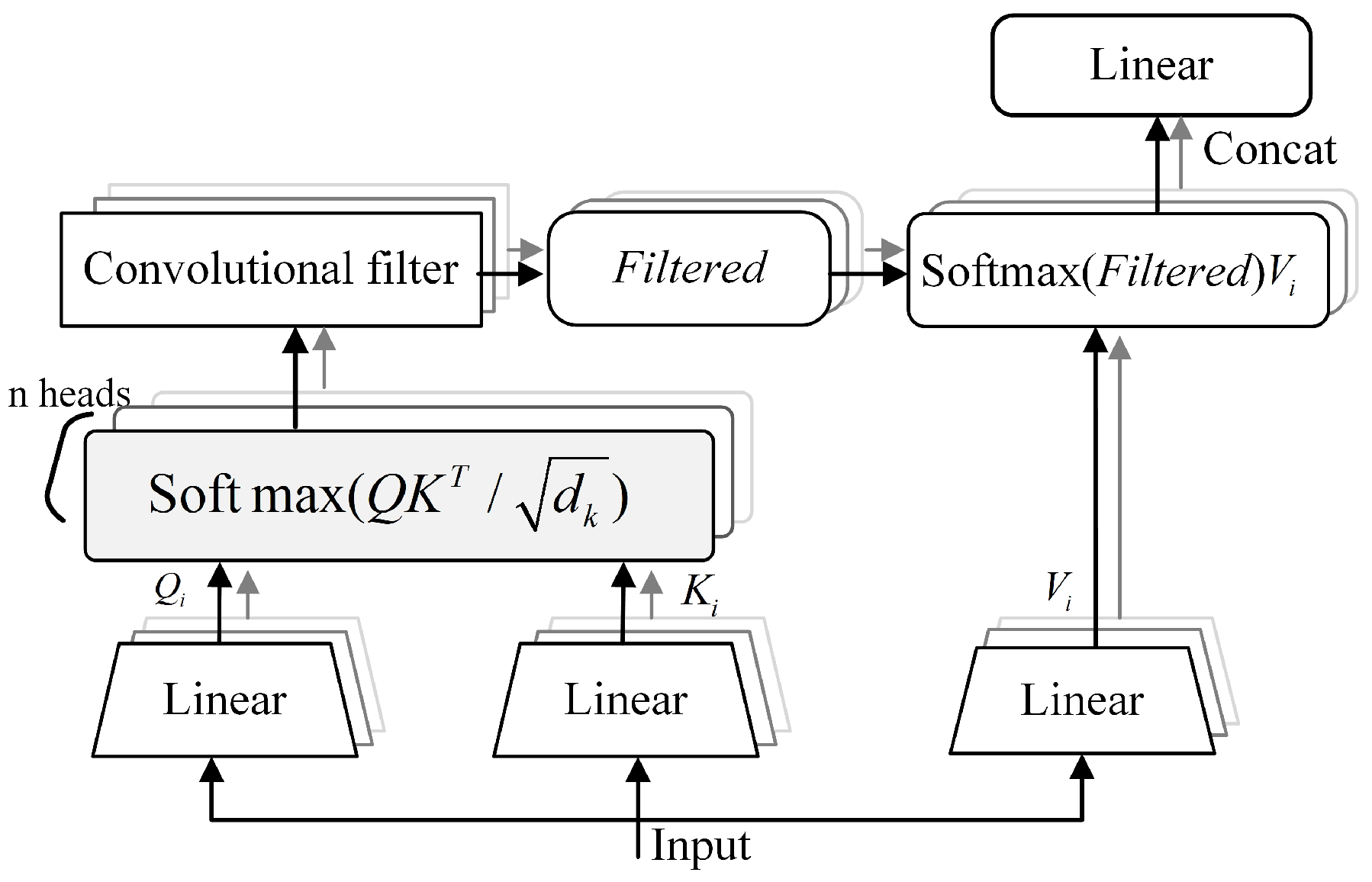

3.5.1. Filter-Attention Mechanism

3.5.2. Multi-Scale Information Fusion

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Settings

4.1.1. Experimental Environment

4.1.2. Datasets

- (1)

- Dataset I: London smart meter dataset (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/jeanmidev/smart-meters-in-london, accessed on 16 November 2025).

- (2)

- Dataset II: UCI electricity load dataset (https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/321, accessed on 16 November 2025).

4.1.3. Data Processing

4.1.4. Result Evaluation

4.2. Comparison of Clustering Results on 2 Datasets

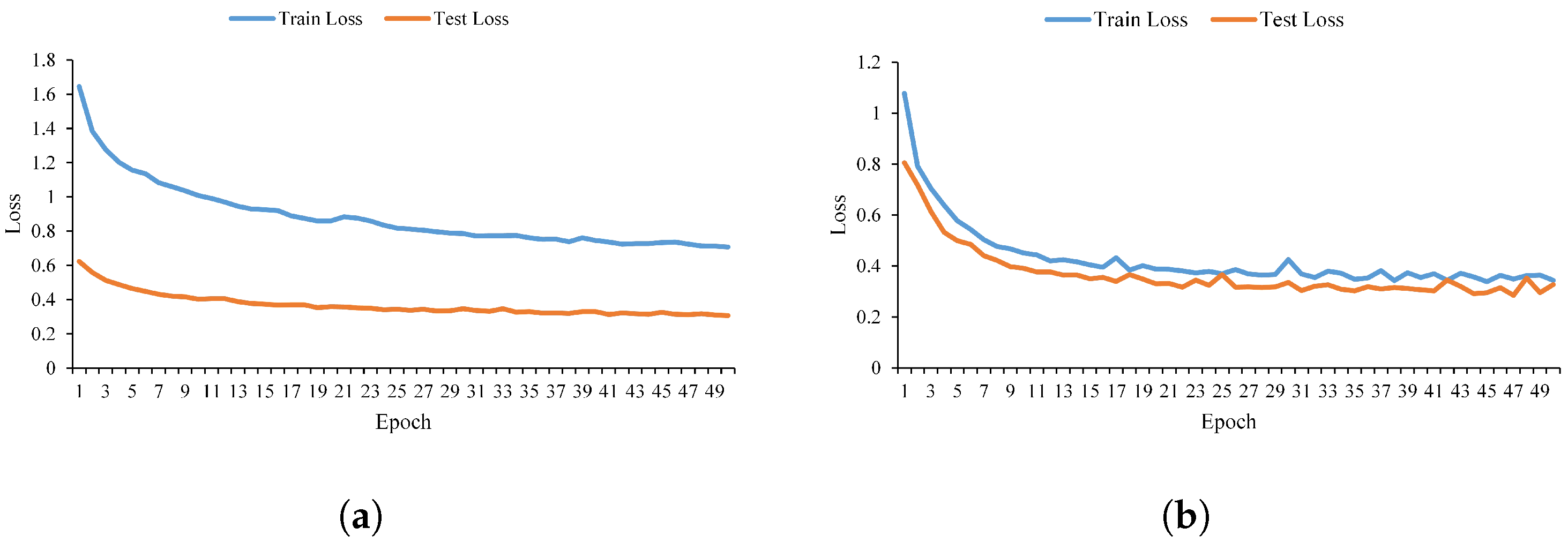

4.3. Training Parameter Tuning

4.4. Effectiveness of Clustering for Short-Term Forecasting

4.5. Comparison with Baseline Models

- (1)

- (2)

4.5.1. Comparison of Experimental Results on Dataset I

4.5.2. Comparison of Experimental Results on Dataset II

4.6. Performance Comparison

4.7. Ablation Experiment

- (1)

- w/o Multi-task: Instead of adopting the multi-task learning paradigm, load forecasting is performed independently for each cluster after clustering.

- (2)

- w/ Self-attention: The filter-attention module is replaced with the vanilla self-attention module from the original Transformer architecture.

- (3)

- w/o Inception: The Inception module is removed from the model, thus disabling multi-scale feature extraction.

- (4)

- w/o Dy-weighting: The dynamic weighting strategy is removed from the model.

- (5)

- w/ Un-weighting: The dynamic weighting is replaced with the uncertainty weighting.

- (6)

- w/ InceptionSize: The number of convolutional branches in the Inception module is set to 4, with an additional branch of kernel size 7.

- (7)

- w/ FilterSize: The window size in the filter-attention mechanism is set to 5.

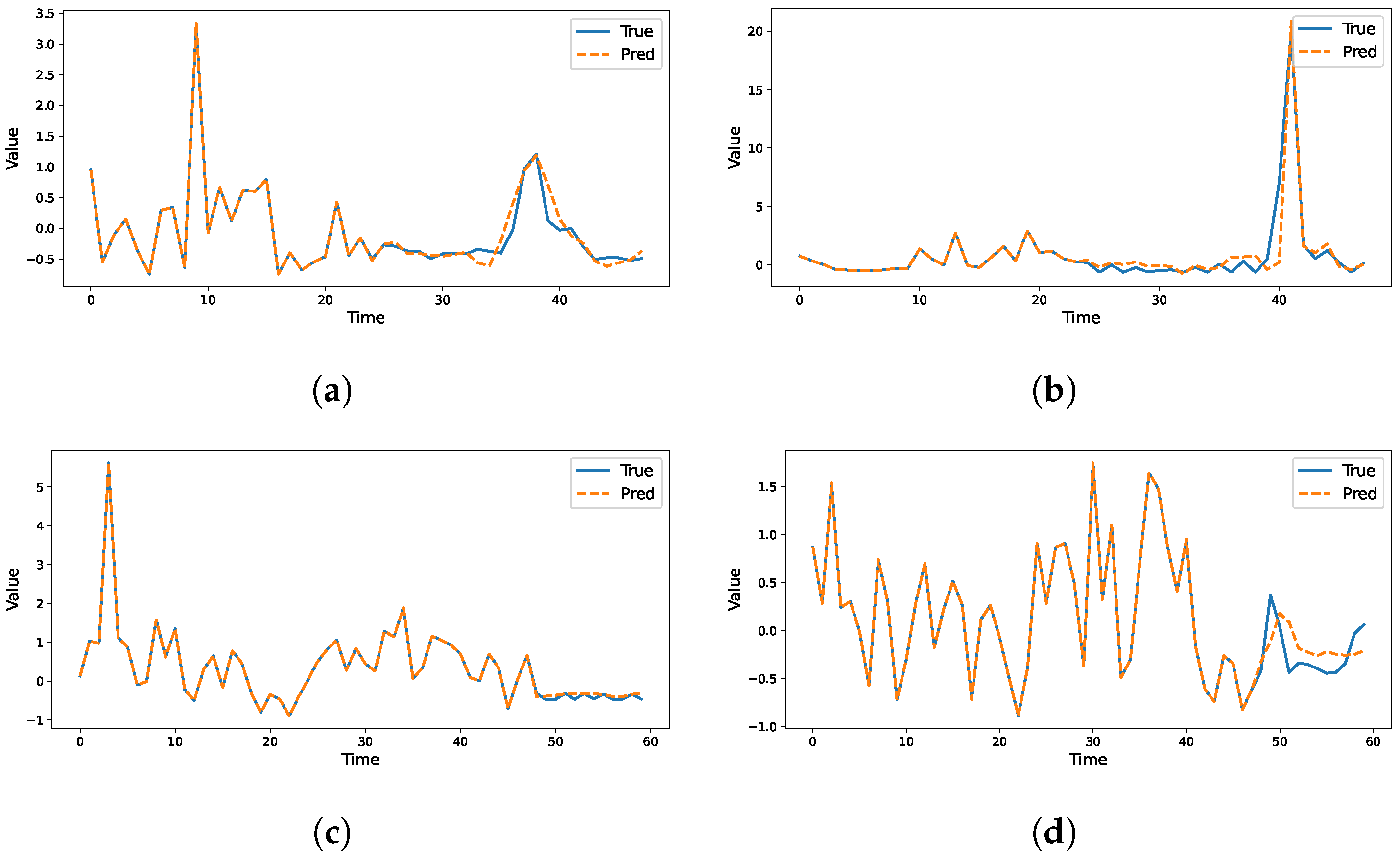

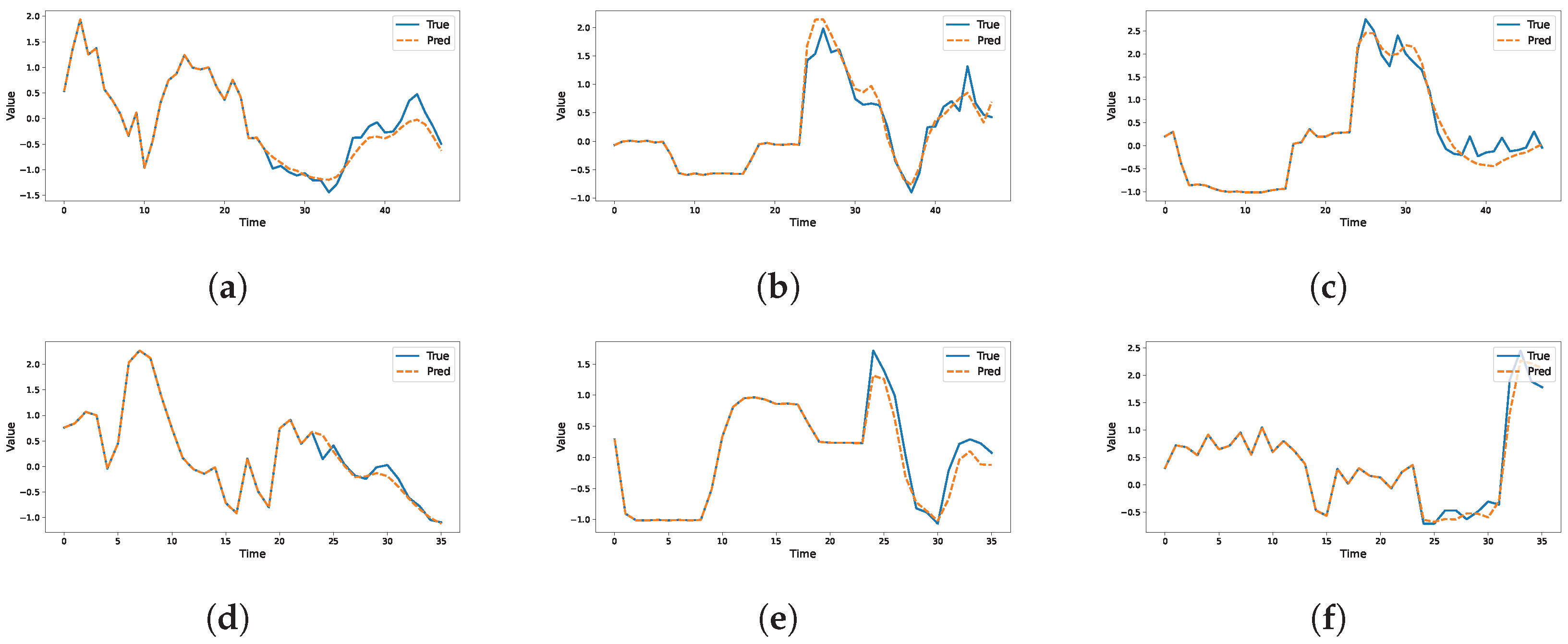

4.8. Visualization of Prediction Results on Different Datasets

4.9. Results Discussion

- (1)

- Our model combines clustering algorithms with multi-task learning to accurately classify user electricity consumption patterns while overcoming the limitations of traditional models. By learning from multiple related tasks, the model captures shared patterns across different groups, improving prediction accuracy and adaptability in complex scenarios with diverse user behaviors.

- (2)

- Compared to other models, our approach’s main advantage lies in the integration of filter-attention mechanisms and Inception convolution modules into the encoder. This combination enhances the model’s ability to capture local patterns and fuse multi-scale features, resulting in improved prediction performance. By focusing on relevant features and extracting information at multiple scales, the model becomes more robust to variations in the data.

- (3)

- The effectiveness of the proposed model is systematically validated through comparative experiments and ablation studies. Experimental analysis demonstrates that the proposed method exhibits significant advantages in prediction accuracy, with each module playing a crucial role.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fan, D.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Shao, X.; Deng, X.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, J. Economic Operation of an Agent-Based Virtual Storage Aggregated Residential Electric-Heating Loads in Multiple Electricity Markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 454, 142112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourdaryaei, A.; Mohammadi, M.; Mubarak, H.; Abdellatif, A.; Karimi, M.; Gryazina, E.; Terzija, V. A New Framework for Electricity Price Forecasting Via Multi-Head Self-Attention and CNN-based Techniques in the Competitive Electricity Market. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 235, 121207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Optimization and Research of Smart Grid Load Forecasting Model Based on Deep Learning. Int. J.-Low-Carbon Technol. 2024, 19, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, Y.; Kucukdemiral, I. A Comprehensive Review on Deep Learning Approaches for Short-Term Load Forecasting. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 114031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botman, L.; Soenen, J.; Theodorakos, K.; Yurtman, A.; Bekker, J.; Vanthournout, K.; Blockeel, H.; Moor, B.D.; Lago, J. A Scalable Ensemble Approach to Forecast the Electricity Consumption of Households. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhu, J.; Li, S.; Wu, W.; Zhu, H.; Fan, J. Short-term Residential Household Reactive Power Forecasting Considering Active Power Demand Via Deep Transformer Sequence-to-sequence Networks. Appl. Energy 2023, 329, 120281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, C.; Strbac, G. Personalized Retail Pricing Design for Smart Metering Consumers in Electricity Market. Appl. Energy 2023, 348, 121545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, Z.; Huang, C.; Ai, Q. Online Transfer Learning-Based Residential Demand Response Potential Forecasting for Load Aggregator. Appl. Energy 2024, 358, 122631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Zhang, D.; Yu, H.; Peng, B.; Wu, Y.; Yu, T.; Wang, K. Customer Load Forecasting Method Based on the Industry Electricity Consumption Behavior Portrait. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 742993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalalifar, R.; Delavar, M.R.; Ghaderi, S.F. SAC-ConvLSTM: A Novel Spatio-Temporal Deep Learning-Based Approach for a Short Term Power Load Forecasting. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Liu, N.; Shi, J.; Ding, Y. Tackling the Duck Curve in Renewable Power System: A Multi-Task Learning Model with Itransformer for Net-Load Forecasting. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 326, 119442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y.; Han, S. Short-term Wind Power Prediction Method Based on Deep Clustering-Improved Temporal Convolutional Network. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 2118–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Lu, Z.; Liu, H.; He, X.; Zhang, X.; Guo, J. Short-term Prediction of Integrated Energy Load Aggregation Using a Bi-Directional Simple Recurrent Unit Network with Feature-Temporal Attention Mechanism Ensemble Learning Model. Appl. Energy 2024, 355, 122159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, W.; Ji, Y.; Liang, C. Short-term Load Forecasting Method Based on Secondary Decomposition and Improved Hierarchical Clustering. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 101993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Liao, C.; Chen, J.; Cao, Y.; Wang, R.; Su, Y. A multi-task learning method for multi-energy load forecasting based on synthesis correlation analysis and load participation factor. Appl. Energy 2023, 343, 121177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.-W.; Cao, M.; Fang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.-W. Joint Load Prediction of Multiple Buildings Using Multi-Task Learning with Selected-Shared-Private Mechanism. Energy Build. 2023, 293, 113178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ding, Z. Frequency-Aware Multi-Task Forecasting for Integrated Energy Systems Via Variational Mode Decomposition and Convolution-Attention Encoding. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, M.Y.; Freire, R.Z.; Seman, L.O.; Stefenon, S.F.; Mariani, V.C.; dos Santos Coelho, L. Optimized Hybrid Ensemble Learning Approaches Applied to Very Short-Term Load Forecasting. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 155, 109579. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, R.; Chen, Y. Improving Model Generalization for Short-Term Customer Load Forecasting with Causal Inference. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025, 16, 424–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Anastasiu, D.C. MC-ANN: A Mixture Clustering-Based Attention Neural Network for Time Series Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. 2025, 47, 6888–6899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, S.; Kim, S. Time-series Clustering and Forecasting Household Electricity Demand Using Smart Meter Data. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 4111–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjout, D.; Sebaa, A.; Torres, J.F.; Martinez-Alvarez, F. Electricity Consumption Forecasting with Outliers Handling Based on Clustering and Deep Learning with Application to the Algerian Market. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 227, 120123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, C. Develop a Multi-Linear-trend Fuzzy Information Granule Based Short-Term Time Series Forecasting Model with K-Medoids Clustering. Inf. Sci. 2023, 629, 358–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Shi, J.; Li, S.; Song, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z. A Combined Deep Learning Load Forecasting Model of Single Household Resident User Considering Multi-Time Scale Electricity Consumption Behavior. Appl. Energy 2022, 307, 118197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dab, K.; Henao, N.; Nagarsheth, S.; Dube, Y.; Sansregret, S.; Agbossou, K. Consensus-based Time-Series Clustering Approach to Short-Term Load Forecasting for Residential Electricity Demand. Energy Build. 2023, 299, 113550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jiaze, E.; Zhang, X.; Sheng, H.; Cheng, X. Multi-Task Time Series Forecasting with Shared Attention. In Proceedings of the Industrial Conference on Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 15–19 July 2020; pp. 917–925. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, S.; Bao, J.; Lu, C. A Time Series Multitask Framework Integrating a Large Language Model, Pre-Trained Time Series Model, and Knowledge Graph. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.07682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, W.; Wu, C. EDformer Family: End-to-end Multi-Task Load Forecasting Frameworks for Day-Ahead Economic Dispatch. Appl. Energy 2025, 383, 125319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, Y.; Qiao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Mei, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhou, Y.; Nakanishi, Y. BiLSTM Multitask Learning-Based Combined Load Forecasting Considering the Loads Coupling Relationship for Multienergy System. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 3481–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Yin, X.; Jia, L. Hybrid Multitask Multi-Information Fusion Deep Learning for Household Short-Term Load Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 5362–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, Y.; Ji, S.; Zhang, S.; Ni, C. A Multitask Graph Convolutional Network with Attention-Based Seasonal-Trend Decomposition for Short-Term Load Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 40, 3222–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Cai, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, X. User Behavior Analysis Based on Stacked Autoencoder and Clustering in Complex Power Grid Environment. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. 2022, 23, 25521–25535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalakopoulos, V.; Sarmas, E.; Papias, I.; Skaloumpakas, P.; Marinakis, V.; Doukas, H. A Machine Learning-Based Framework for Clustering Residential Electricity Load Profiles to Enhance Demand Response Programs. Appl. Energy 2024, 361, 122943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q. A Survey on Multi-Task Learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 34, 5586–5609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, W.; Pan, S.J. Multi-task Learning. Mach. Learn. 2020, 126–140. [Google Scholar]

- Heng, S. Enhanced Multi-Energy Load Forecasting Via Multi-Task Learning and GRU-attention Networks in Integrated Energy Systems. Electr. Eng. 2025, 107, 7673–7683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Lam, W.; Yu, Q.; So, A.M.-C.; Hu, S.; Liu, Z.; Collier, N. Decoder-Only or Encoder-Decoder? Interpreting Language Model As a Regularized Encoder-Decoder. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.04052. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.; Koker, T.; Queen, O.; Hartvigsen, T.; Tsiligkaridis, T.; Zitnik, M. UniTS: A Unified Multi-Task Time Series Model. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–15 December 2024; pp. 140589–140631. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, C.; Xiong, W.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, T. Corruption-robust algorithms with uncertainty weighting for nonlinear contextual bandits and markov decision processes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 39834–39863. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Cao, L.; Madden, S.; Ives, Z.; Li, G. RITA: Group Attention is All You Need for Timeseries Analytics. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD Conference, Santiago, Chile, 9–15 June 2024; pp. 62:1–62:28. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, T.; Dong, L.; Xia, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, G.; Wei, F. Differential Transformer. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Hong Kong, China, 20–22 October 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-Barrachina, J.-M.; Ye-Lin, Y.; del Amor, F.N.; Fuster-Roig, V. Inception 1D-Convolutional Neural Network for Accurate Prediction of Electrical Insulator Leakage Current from Environmental Data During Its Normal Operation Using Long-Term Recording. Eng. Appl. Artif. 2023, 119, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, X.; Hu, L.; Fan, J.; Han, M. A time series continuous missing values imputation method based on generative adversarial networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 283, 111215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Wu, X.; Lin, Y.; Guo, C.; Hu, J.; Yang, B. DUET: Dual Clustering Enhanced Multivariate Time Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the KDD 2025, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3–7 August 2025; pp. 1185–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The Coefficient of Determination R-squared is More Informative Than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in Regression Analysis Evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, H.; Lim, C. ST-MTM: Masked Time Series Modeling with Seasonal-Trend Decomposition for Time Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the KDD 2025, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3–7 August 2025; pp. 1209–1220. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wu, H.; Shi, X.; Hu, T.; Luo, H.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J.Y.; Zhou, J. TimeMixer: Decomposable Multiscale Mixing for Time Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Vienna, Austria, 7 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, M.; Yang, J.; Pan, T.; Liu, Q.; Li, Z. ConvTimeNet: A Deep Hierarchical Fully Convolutional Model for Multivariate Time Series Analysis. In Proceedings of the WWW’25: Companion Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025, Sydney, Australia, 28 April–2 May 2025; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Hu, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Long, M. TimesNet: Temporal 2D-Variation Modeling for General Time Series Analysis. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, G.; Liu, C.; Sahoo, D.; Kumar, A.; Hoi, S. ETSformer: Exponential Smoothing Transformers for Time-series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the ICLR 2023, Online, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Ma, Z.; Wen, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Jin, R. FEDformer: Frequency Enhanced Decomposed Transformer for Long-term Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Pontignano, Italy, 19–22 September 2022; pp. 27268–27286. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, A.; Chen, M.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Q. Are Transformers Effective for Time Series Forecasting? In Proceedings of the AAAI, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; pp. 11121–11128. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, S.; Yang, J.; Ruan, X.; Qin, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, W. MSM-TFL: A Multiservice, Multitask Transformer Framework for Edge Load Prediction. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 37790–37808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Miao, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, J. AutoSTL: Automated Spatio-Temporal Multi-Task Learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; pp. 4902–4910. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Huang, Y.; Pan, Z.; Li, W.; Hu, Y.; Lin, G. Multi-Task Time Series Forecasting Based on Graph Neural Networks. Entropy 2023, 25, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Task Type | Method | Cluster 0 (12-Step) | Cluster 1 (12-Step) | Cluster 0 (24-Step) | Cluster 1 (24-Step) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | ||

| Single-task models | Timemixer | 0.5049 | 0.9387 | 0.4964 | 0.9749 | 0.5079 | 0.9248 | 0.5052 | 0.9929 |

| Convtimenet | 0.5052 | 0.9928 | 0.4863 | 0.9764 | 0.5124 | 0.9937 | 0.5083 | 1.0245 | |

| Timesnet | 0.4860 | 0.8588 | 0.4898 | 0.8860 | 0.4483 | 0.8349 | 0.4981 | 0.8894 | |

| ETSformer | 0.5554 | 0.9029 | 0.6875 | 1.0601 | 0.5592 | 0.8992 | 0.7540 | 1.1250 | |

| Fedformer | 0.7412 | 1.1114 | 0.6924 | 1.1659 | 0.7511 | 1.1215 | 0.7424 | 1.1973 | |

| Dlinear | 0.4614 | 0.8024 | 0.5016 | 0.8830 | 0.4661 | 0.8072 | 0.5068 | 0.8853 | |

| Multi-task models | Multi-Transformer | 0.3543 | 0.6467 | 0.4877 | 0.6750 | 0.3259 | 0.6108 | 0.4892 | 0.7109 |

| AutoSTL | 0.4037 | 0.7412 | 0.4966 | 0.7635 | 0.4174 | 0.7603 | 0.5063 | 0.7940 | |

| Multitask-GNN | 0.2917 | 0.5323 | 0.5071 | 0.7126 | 0.4001 | 0.6246 | 0.4738 | 0.6929 | |

| GCML | 0.2858 | 0.5042 | 0.4312 | 0.5266 | 0.3090 | 0.5596 | 0.4433 | 0.5690 | |

| Task Type | Method | Cluster 0 | Cluster 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 (12-Step) | R2 (24-Step) | R2 (12-Step) | R2 (24-Step) | ||

| Single-task models | Timemixer | 0.2595 | 0.2445 | 0.2516 | 0.2316 |

| Convtimenet | 0.4211 | 0.3721 | 0.3745 | 0.3624 | |

| Timesnet | 0.5636 | 0.5516 | 0.5549 | 0.5381 | |

| ETSformer | 0.5671 | 0.5238 | 0.4553 | 0.4108 | |

| Fedformer | 0.3464 | 0.3240. | 0.3266 | 0.3445 | |

| Dlinear | 0.6432 | 0.6388 | 0.6238 | 0.5812 | |

| Multi-task models | Multi-Transformer | 0.5816 | 0.6269 | 0.5447 | 0.4945 |

| AutoSTL | 0.4511 | 0.4221 | 0.4167 | 0.3706 | |

| Multitask-GNN | 0.7168 | 0.6908 | 0.4922 | 0.5200 | |

| GCML | 0.7587 | 0.6958 | 0.7297 | 0.6856 | |

| Task Type | Method | Cluster 0 (12-Step) | Cluster 1 (12-Step) | Cluster 2 (12-Step) | Cluster 0 (24-Step) | Cluster 1 (24-Step) | Cluster 2 (24-Step) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | ||

| Single-task models | Timemixer | 0.2564 | 0.3962 | 0.2626 | 0.3997 | 0.3226 | 0.5268 | 0.2705 | 0.4200 | 0.2745 | 0.4206 | 0.3446 | 0.5674 |

| Convtimenet | 0.3674 | 0.4788 | 0.3764 | 0.5436 | 0.5099 | 0.9008 | 0.3824 | 0.5332 | 0.4861 | 0.7263 | 0.5467 | 0.8592 | |

| Timesnet | 0.3664 | 0.4831 | 0.277 | 0.4063 | 0.3626 | 0.5922 | 0.3801 | 0.5051 | 0.3116 | 0.4678 | 0.4007 | 0.6473 | |

| ETSformer | 0.3757 | 0.4908 | 0.3596 | 0.4594 | 0.5099 | 0.6825 | 0.4185 | 0.5546 | 0.4169 | 0.5365 | 0.5884 | 0.7911 | |

| Fedformer | 0.4581 | 0.6036 | 0.4130 | 0.5515 | 0.5393 | 0.7440 | 0.4850 | 0.6440 | 0.4434 | 0.5924 | 0.5733 | 0.7843 | |

| Dlinear | 0.3771 | 0.5231 | 0.5093 | 0.6708 | 0.6293 | 0.8688 | 0.4309 | 0.5899 | 0.5576 | 0.7306 | 0.6904 | 0.9252 | |

| Multi-task models | Multi-Transformer | 0.1883 | 0.2622 | 0.2264 | 0.3177 | 0.2792 | 0.3973 | 0.1909 | 0.2648 | 0.1888 | 0.2602 | 0.2887 | 0.2887 |

| AutoSTL | 0.2445 | 0.3306 | 0.2427 | 0.3295 | 0.4258 | 0.5914 | 0.2643 | 0.3556 | 0.2675 | 0.3660 | 0.4076 | 0.5588 | |

| MultiTask-GNN | 0.3644 | 0.4586 | 0.3249 | 0.4181 | 0.2808 | 0.3932 | 0.3767 | 0.4760 | 0.3949 | 0.4823 | 0.2920 | 0.4098 | |

| GCML | 0.1617 | 0.2299 | 0.1554 | 0.2130 | 0.2608 | 0.3678 | 0.1769 | 0.2481 | 0.1725 | 0.2353 | 0.2682 | 0.3799 | |

| Task Type | Method | Cluster 0 | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(12-Step) | (24-Step) | (12-Step) | (24-Step) | (12-Step) | (24-Step) | ||

| Single-task models | Timemixer | 0.8798 | 0.8648 | 0.8745 | 0.8610 | 0.8745 | 0.8109 |

| Convtimenet | 0.8363 | 0.8048 | 0.8251 | 0.7610 | 0.7759 | 0.7230 | |

| Timesnet | 0.7764 | 0.7556 | 0.8388 | 0.7853 | 0.7387 | 0.6750 | |

| ETSformer | 0.5554 | 0.9029 | 0.6875 | 1.0601 | 0.5592 | 0.8992 | |

| Fedformer | 0.7412 | 0.8014 | 0.6924 | 0.8059 | 0.7511 | 0.8215 | |

| Dlinear | 0.7379 | 0.6668 | 0.7465 | 0.6804 | 0.6804 | 0.6296 | |

| Multi-task models | Multi-Transformer | 0.9313 | 0.9299 | 0.8991 | 0.9323 | 0.8421 | 0.8327 |

| AutoSTL | 0.8907 | 0.8735 | 0.8914 | 0.8660 | 0.6501 | 0.6877 | |

| Multitask-GNN | 0.7896 | 0.7734 | 0.8252 | 0.7674 | 0.8252 | 0.8321 | |

| GCML | 0.9471 | 0.9384 | 0.9546 | 0.9446 | 0.8647 | 0.8557 | |

| Method | Cluster 0 (12-Step) | Cluster 1 (12-Step) | Cluster 0 (24-Step) | Cluster 1 (24-Step) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | |

| w/o Multi-task | 0.5521 | 0.9515 | 0.6898 | 1.0363 | 0.5785 | 0.9714 | 0.6309 | 1.0019 |

| w/ Self-attention | 0.3372 | 0.6452 | 0.4964 | 0.7103 | 0.3218 | 0.6181 | 0.4903 | 0.7131 |

| w/o Inception | 0.3828 | 0.7067 | 0.5058 | 0.7715 | 0.3539 | 0.6853 | 0.5022 | 0.7347 |

| w/o Dy-weighting | 0.3263 | 0.5205 | 0.4601 | 0.5857 | 0.3363 | 0.5687 | 0.4984 | 0.6132 |

| w/ Un-weighting | 0.3058 | 0.5639 | 0.4437 | 0.5563 | 0.3257 | 0.6088 | 0.4834 | 0.5865 |

| w/ InceptionSize | 0.2907 | 0.5251 | 0.4452 | 0.5405 | 0.3194 | 0.5992 | 0.4834 | 0.5865 |

| w/ FilterSize | 0.2983 | 0.5565 | 0.4474 | 0.5766 | 0.3146 | 0.5893 | 0.4560 | 0.5712 |

| GCML | 0.2858 | 0.5042 | 0.4312 | 0.5266 | 0.3090 | 0.5596 | 0.4433 | 0.5690 |

| Method | Cluster 0 (12-Step) | Cluster 1 (12-Step) | Cluster 2 (12-Step) | Cluster 0 (24-Step) | Cluster 1 (24-Step) | Cluster 2 (24-Step) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE | |

| w/o Multi-task | 0.3542 | 0.4683 | 0.2765 | 0.3857 | 0.3329 | 0.5086 | 0.3862 | 0.5091 | 0.2907 | 0.4117 | 0.3555 | 0.5632 |

| w/ Self-attention | 0.1861 | 0.2604 | 0.1876 | 0.2649 | 0.3005 | 0.4371 | 0.1936 | 0.2683 | 0.1888 | 0.2618 | 0.2890 | 0.4109 |

| w/o Inception | 0.2144 | 0.2963 | 0.1996 | 0.2824 | 0.3149 | 0.4645 | 0.2211 | 0.3007 | 0.3007 | 0.2919 | 0.2981 | 0.4293 |

| w/o Dy-weighting | 0.1919 | 0.2682 | 0.1865 | 0.2593 | 0.3107 | 0.4461 | 0.2177 | 0.2990 | 0.1902 | 0.2612 | 0.4306 | 0.6090 |

| w/ Un-weighting | 0.1985 | 0.2757 | 0.1684 | 0.2321 | 0.3901 | 0.5595 | 0.2158 | 0.2972 | 0.2077 | 0.2860 | 0.3248 | 0.4652 |

| w/ InceptionSize | 0.1755 | 0.2346 | 0.1659 | 0.2240 | 0.2732 | 0.3880 | 0.1781 | 0.2677 | 0.1747 | 0.2867 | 0.2759 | 0.3978 |

| w/ FilterSize | 0.1695 | 0.2378 | 0.1580 | 0.2161 | 0.2644 | 0.3781 | 0.1831 | 0.2565 | 0.1946 | 0.2558 | 0.2729 | 0.3869 |

| GCML | 0.1617 | 0.2299 | 0.1554 | 0.2130 | 0.2608 | 0.3678 | 0.1769 | 0.2481 | 0.1725 | 0.2353 | 0.2682 | 0.3799 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wan, J.; Sun, Y.; Fan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, R.; Yuan, P. GCML: A Short-Term Load Forecasting Framework for Distributed User Groups Based on Clustering and Multi-Task Learning. Mathematics 2025, 13, 3820. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233820

Wan J, Sun Y, Fan J, Zhou Y, Ye R, Yuan P. GCML: A Short-Term Load Forecasting Framework for Distributed User Groups Based on Clustering and Multi-Task Learning. Mathematics. 2025; 13(23):3820. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233820

Chicago/Turabian StyleWan, Junling, Yusen Sun, Jianguo Fan, Yu Zhou, Rui Ye, and Peisen Yuan. 2025. "GCML: A Short-Term Load Forecasting Framework for Distributed User Groups Based on Clustering and Multi-Task Learning" Mathematics 13, no. 23: 3820. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233820

APA StyleWan, J., Sun, Y., Fan, J., Zhou, Y., Ye, R., & Yuan, P. (2025). GCML: A Short-Term Load Forecasting Framework for Distributed User Groups Based on Clustering and Multi-Task Learning. Mathematics, 13(23), 3820. https://doi.org/10.3390/math13233820