A Domain-Adversarial Mechanism and Invariant Spatiotemporal Feature Extraction Based Distributed PV Forecasting Method for EV Cluster Baseline Load Estimation

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Literature Review

1.3. Contribution

- (1)

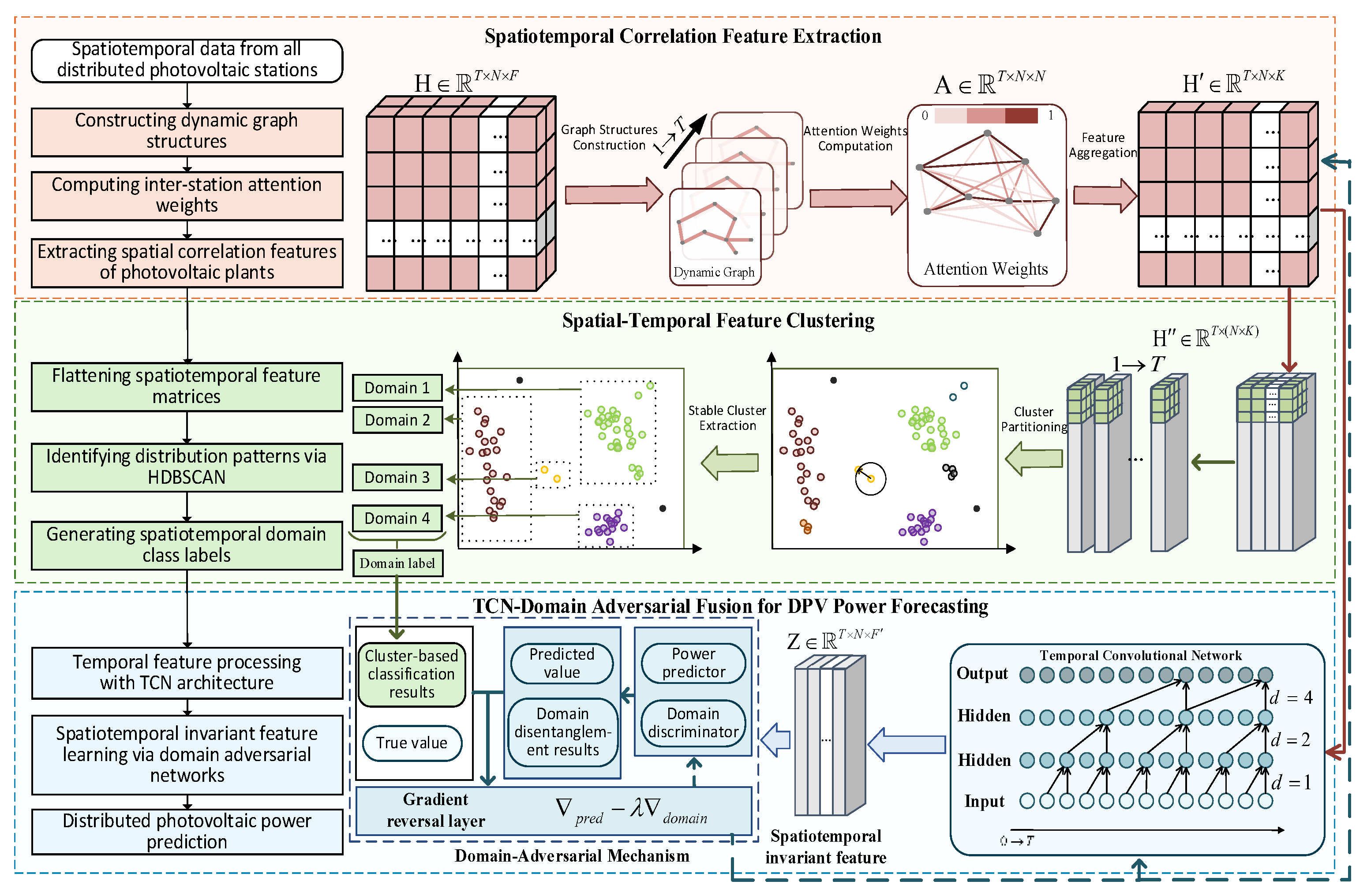

- A GAT-HDBSCAN-TCN domain-adversarial fusion framework is proposed. This framework innovatively integrates dynamic spatial dependency modeling, unsupervised distribution domain partitioning, and spatiotemporal invariant feature extraction, offering an effective solution to spatiotemporal distribution shifts in distributed PV forecasting.

- (2)

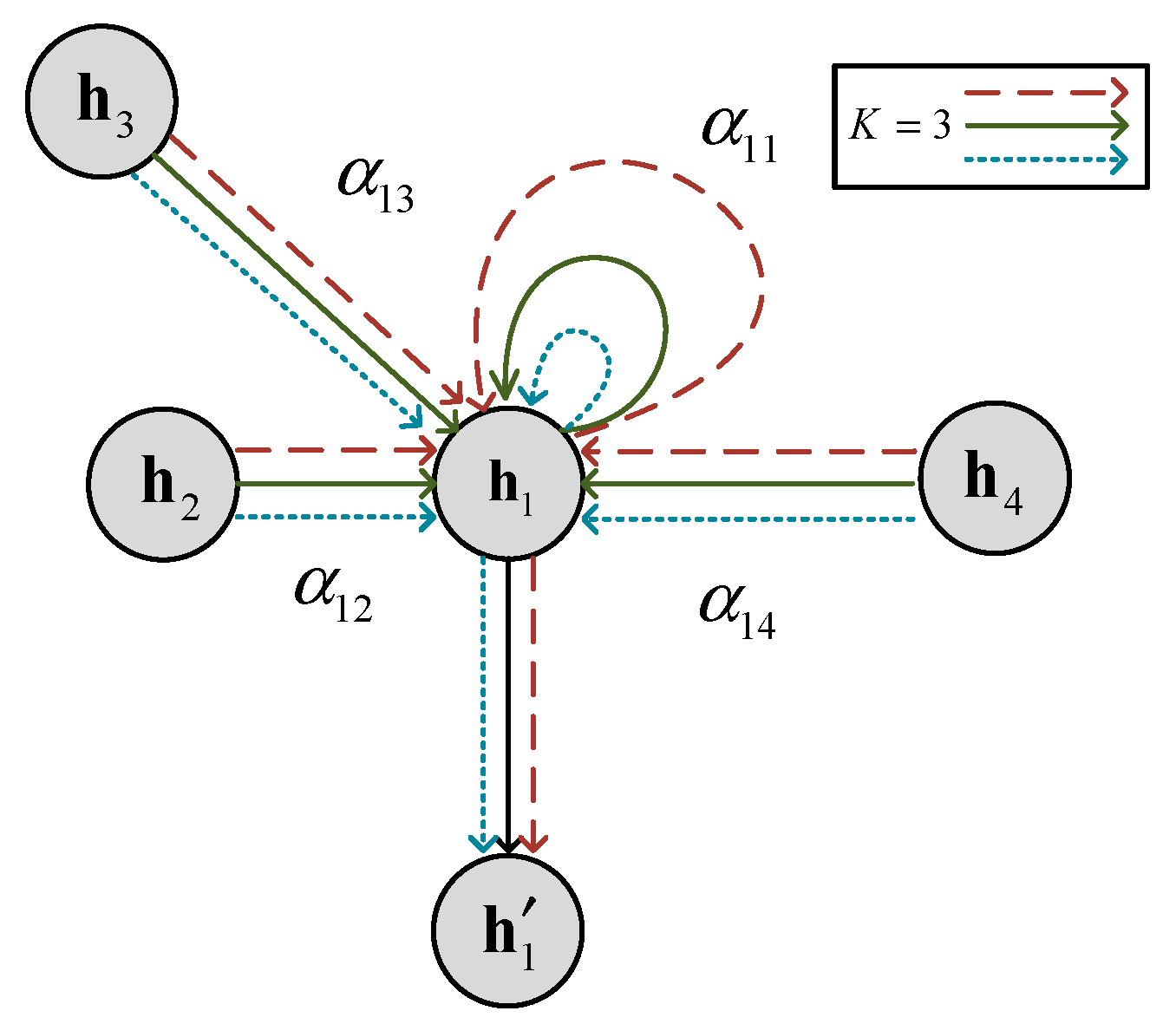

- A dynamic spatial dependency feature extraction and unsupervised domain partitioning strategy is designed. To address the dynamic spatiotemporal correlations among PV stations under disturbances, a GAT is employed to adaptively capture spatial dependencies, overcoming the limitations of static graph models like traditional GCN. Subsequently, the HDBSCAN clustering algorithm is introduced for unsupervised domain partitioning, automatically identifying multiple distribution domains and eliminating the subjectivity of manual domain labeling.

- (3)

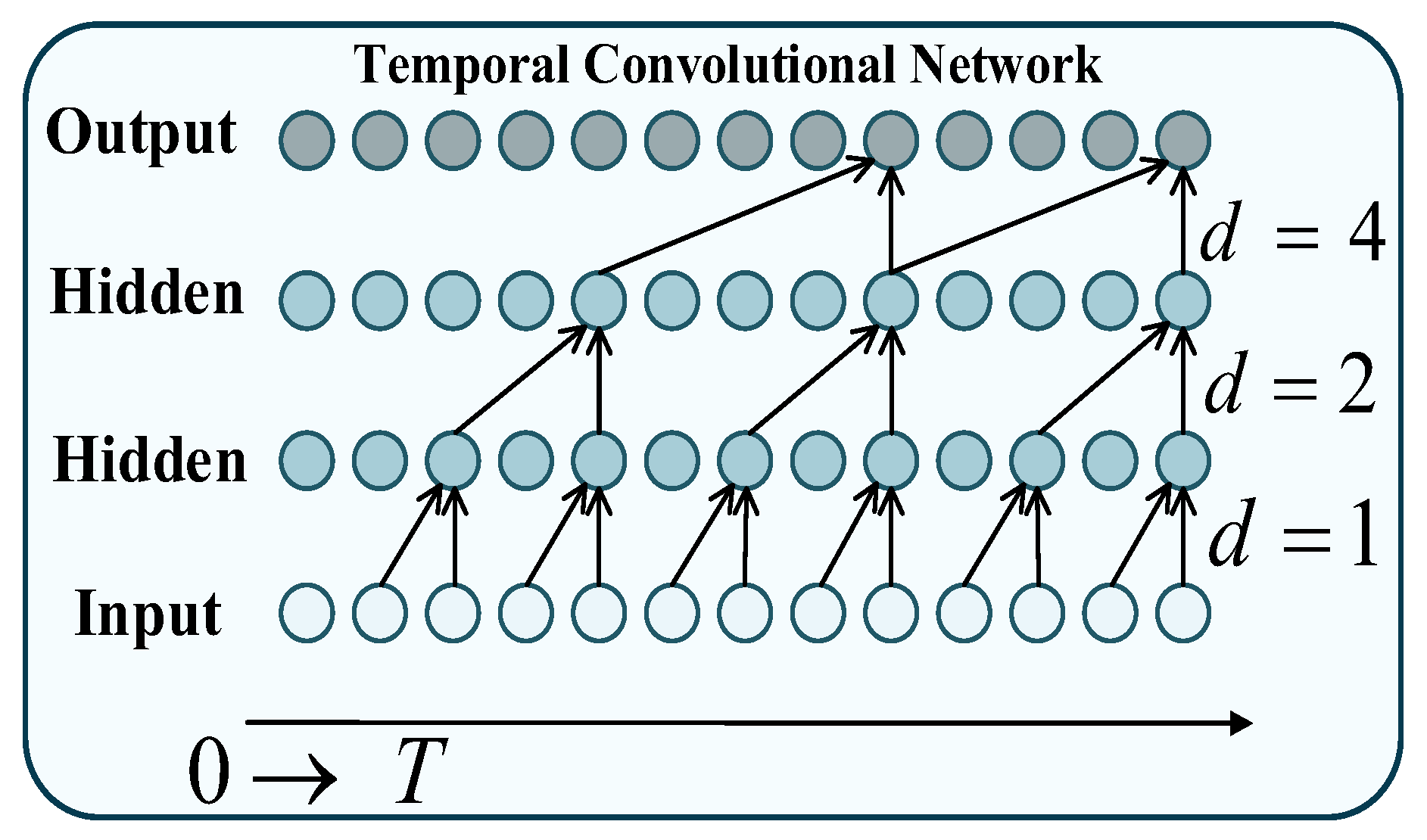

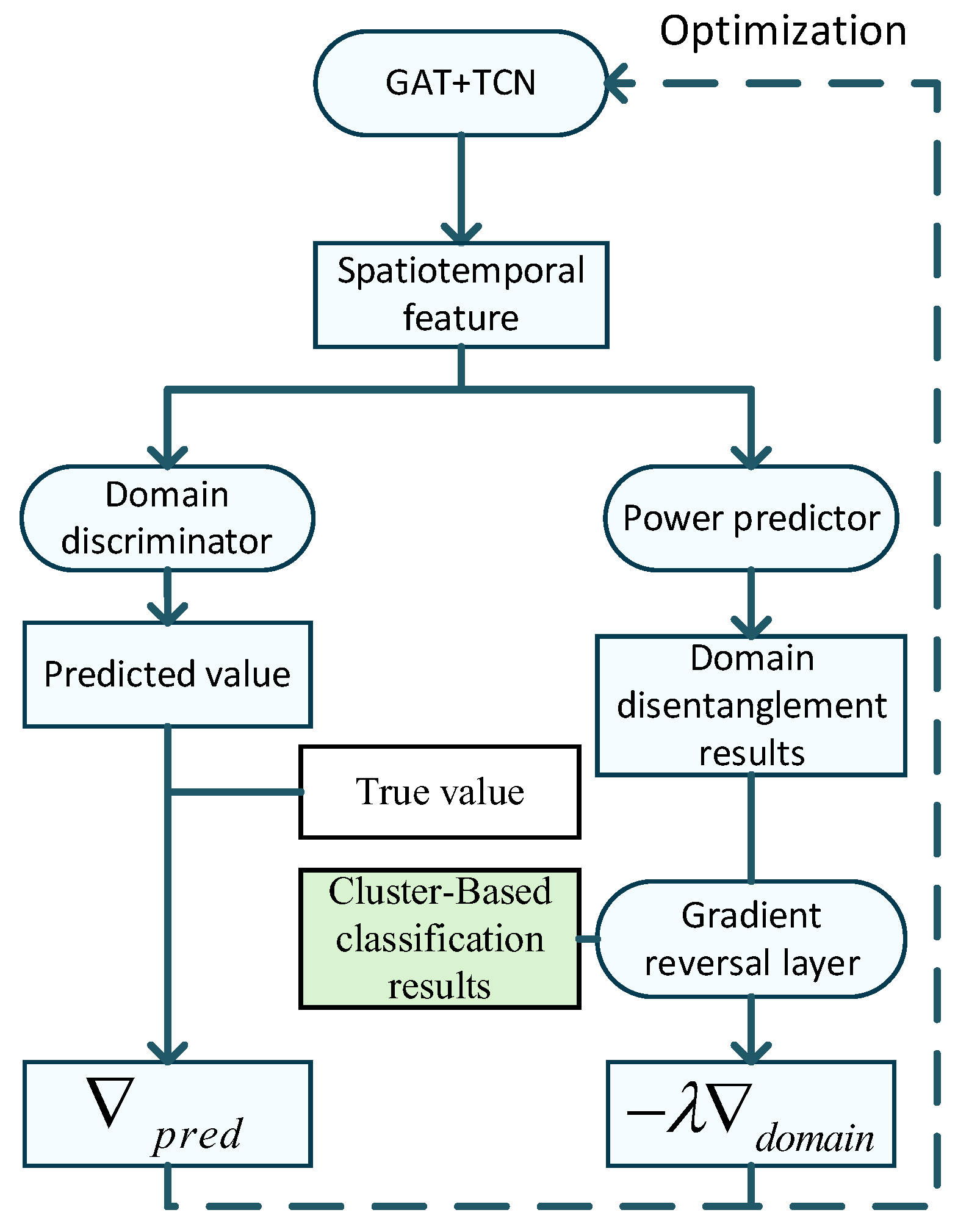

- A feature learning mechanism combining TCN and domain-adversarial training is designed to extract domain-invariant spatiotemporal features. The feature extractor GAT-TCN and domain discriminator are optimized through adversarial competition: the feature extractor generates domain-indistinguishable feature representations, suppressing domain-specific information (e.g., weather conditions or station locations), thereby learning spatiotemporal invariant features that characterize PV output patterns. This significantly enhances the model’s generalization capability.

2. DPV Forecasting Method Considering Spatiotemporal Invariant Feature Modeling

- (1)

- Spatiotemporal correlation feature extraction: GAT is utilized to dynamically capture spatial dependency features among DPV stations. Attention weights are adaptively calculated based on real-time meteorological and power states of each station, effectively characterizing non-uniform spatial dependencies under localized abrupt weather changes.

- (2)

- Spatiotemporal feature clustering: The HDBSCAN algorithm is applied to adaptively partition the spatiotemporal feature matrix output by the GAT, identifying distinct distribution domains corresponding to weather patterns. This constructs discriminative domain structures to support subsequent adversarial training.

- (3)

- TCN-domain adversarial fusion for DPV power forecasting: A domain-adversarial training mechanism is established by combining the TCN with a gradient reversal layer (GRL) and a domain discriminator. This mechanism strips domain-specific variant features from multi-domain data, extracts cross-domain robust spatiotemporal invariant features, and ultimately achieves accurate ultra-short-term PV power forecasting.

2.1. Spatial Correlation Feature Extraction Based on GAT

2.2. Spatiotemporal Feature Clustering Based on HDBSCAN

2.3. DPV Power Forecasting Based on Temporal Convolutional Network and Domain Adversarial Fusion

3. Case Study

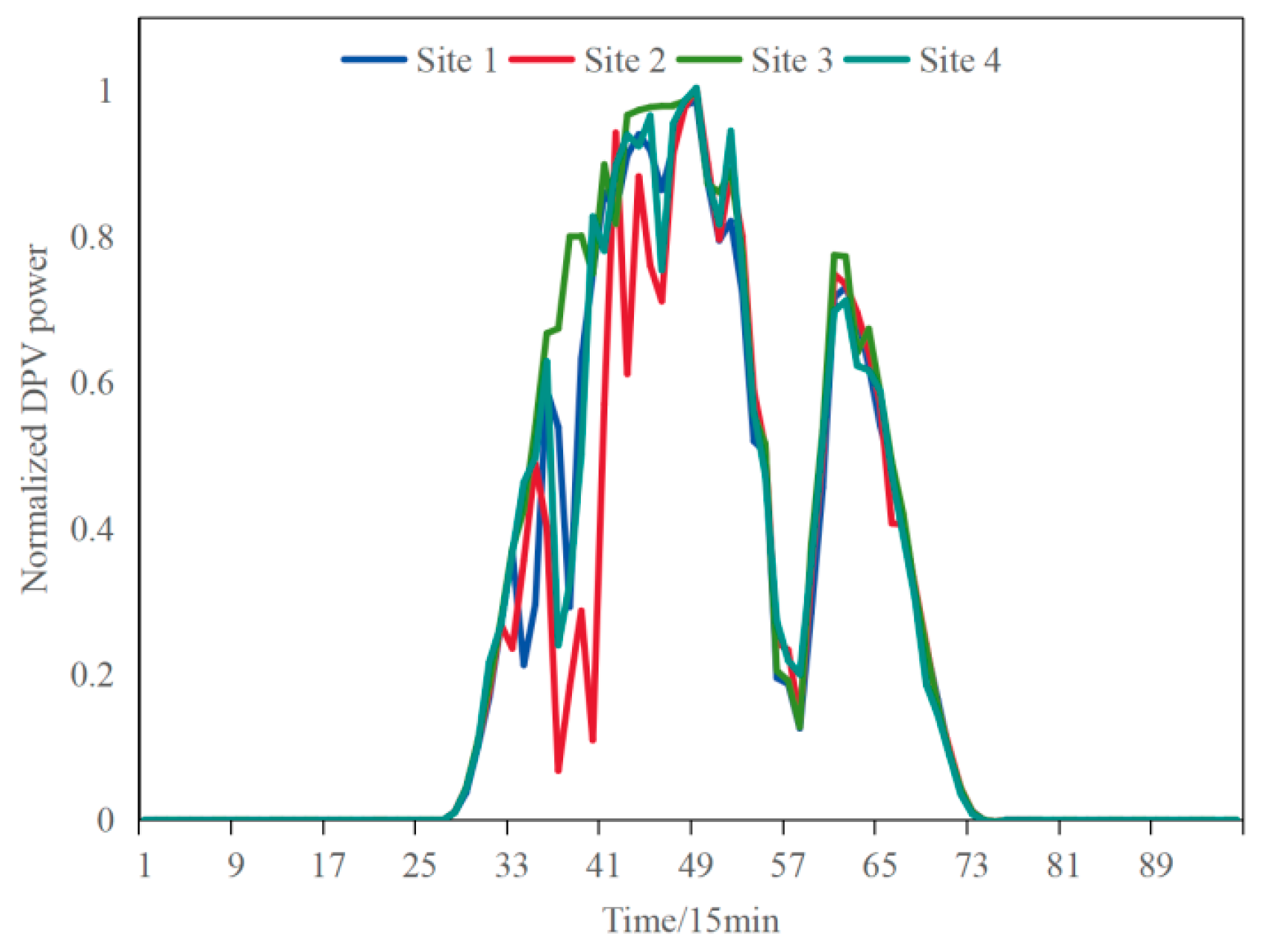

3.1. Data Description and Implementation Details

3.2. Evaluation Metrics

3.3. Benchmarks Configuration

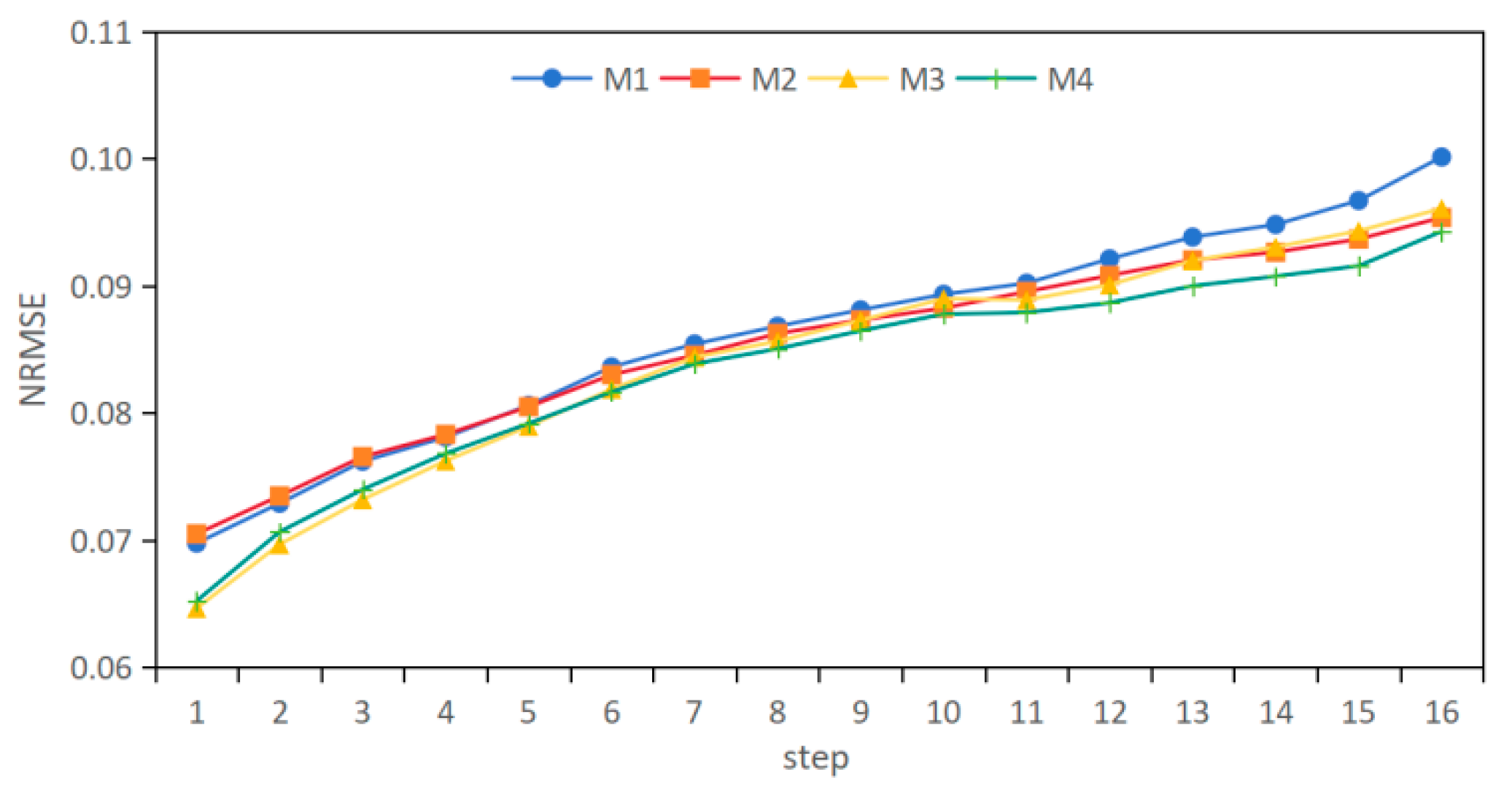

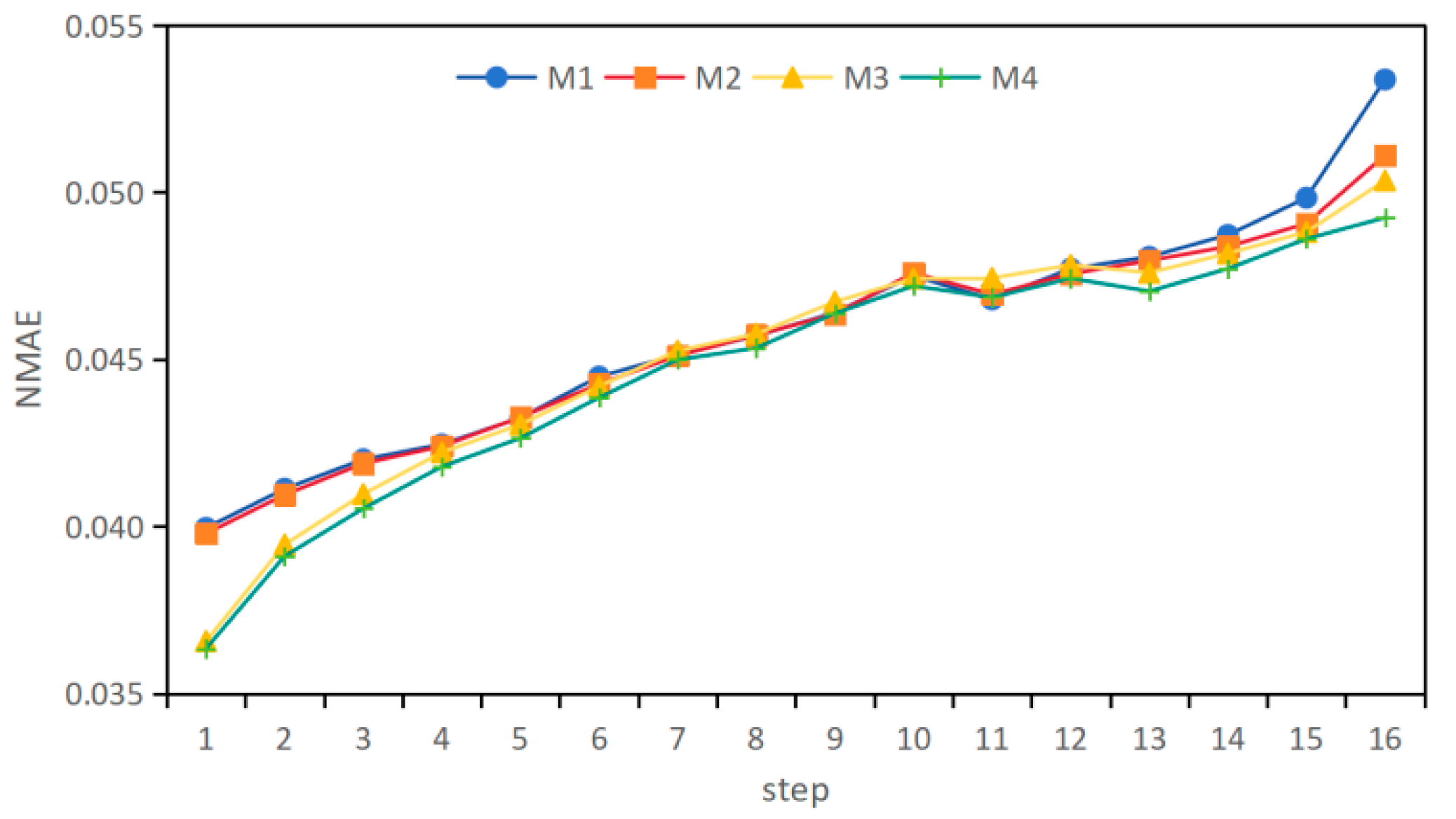

3.4. The Results and Analysis of Regional Forecasting

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yin, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q. Mechanisms and implementation pathways for distributed photovoltaic grid integration in rural power systems: A study based on multi-agent game theory approach. Energy Strategy Rev. 2025, 60, 101801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, M.; Run, W.; Yang, L.; Liu, D. Ultra-Short-Term Power Prediction for Distributed Photovoltaics Based on Time-Series LLMs. Electronics 2025, 14, 4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H. Spatiotemporal Forecasting of Regional Electric Vehicles Charging Load: A Multi-Channel Attentional Graph Network Integrating Dynamic Electricity Price and Weather. Electronics 2025, 14, 4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yan, J.; Hu, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, N. Two-stage decoupled estimation approach of aggregated baseline load under high penetration of behind-the-meter PV system. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 4876–4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, Z.; Yang, J.; Yang, J.; Li, S.; He, X. GCN-Transformer-Based Spatio-Temporal Load Forecasting for EV Battery Swapping Stations under Differential Couplings. Electronics 2024, 13, 3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghami, M.; Pasupuleti, J.; Ling, C. Impact of photovoltaic penetration on medium voltage distribution network. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, W.; Du, M.; Liang, T.; Liu, Y.; Fan, H.; Li, J. Ultrashort-Term Power Prediction of Distributed Photovoltaic Based on Variational Mode Decomposition and Channel Attention Mechanism. Energy Eng. 2025, 122, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Wu, H.; Lin, J.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Huang, X.; Zhao, J. A distributed photovoltaic short-term power forecasting model based on lightweight AI for edge computing in low-voltage distribution network. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2024, 18, 3955–3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Liu, T.; Weng, J.; Liu, D. Lightweight Edge Stream Processing Framework and Task Scheduling Algorithm for CNN-Based Distributed PV Output Prediction. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2025, 19, e70057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimzadeh, N.; Vahdatikhaki, F.; Hammad, A. Parametric modeling and surface-specific sensitivity analysis of PV module layout on building skin using BIM. Energy Build. 2020, 216, 109953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Peng, Y.; Chen, J.; Meng, L. Short-term photovoltaic power prediction with similar-day integrated by BP-AdaBoost based on the Grey-Markov model. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 215, 108966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Li, L.; Tseng, M.; Liu, H.; Yuan, D.; Tan, R. An improved moth-flame optimization algorithm for support vector machine prediction of photovoltaic power generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Y. Quad-kernel deep convolutional neural network for intra-hour photovoltaic power forecasting. Appl. Energy 2022, 323, 119682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wei, J.; Sun, G.; Muyeen, S.; Lin, S.; Li, F. A short-term probabilistic photovoltaic power prediction method based on feature selection and improved LSTM neural network. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 210, 108069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.; Zhen, Z.; Wang, F.; Fu, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Ren, H. Sub-region division based short-term regional distributed PV power forecasting method considering spatio-temporal correlations. Energy 2024, 288, 129716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Wang, S.; Bak-Jensen, B.; Pillai, J.; Yang, Z.; Liu, K. Ultra-short-term interval prediction of wind power based on graph neural network and improved bootstrap technique. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2023, 11, 1100–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Kuldeep, S.A.; Rafa, S.J.; Fazal, J.; Hoque, M.; Liu, G.; Gandomi, A.H. Enhancement of traffic forecasting through graph neural network-based information fusion techniques. Inf. Fusion 2024, 110, 102466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shu, S.; Zheng, J. DEST-GNN: A double-explored spatio-temporal graph neural network for multi-site intra-hour PV power forecasting. Appl. Energy 2025, 378, 124744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satpathy, P.; Babu, T.; Shanmugam, S.; Popavath, L.; Alhelou, H. Impact of uneven shading by neighboring buildings and clouds on the conventional and hybrid configurations of roof-top PV arrays. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 139059–139073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhen, Z.; Wang, F. Dynamic directed graph convolution network based ultra-short-term forecasting method of distributed photovoltaic power to enhance the resilience and flexibility of distribution network. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2024, 18, 337–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Xiao, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, H.; Gao, W.; Pei, W. Power prediction of regional distributed photovoltaic clusters with incomplete information based on improved weighted fusion and transfer learning. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2024, 18, 1556–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, S.; Xi, X.; Su, D.; Han, Z.; Wang, D. Spatio-Temporal Photovoltaic Power Prediction with Fourier Graph Neural Network. Electronics 2024, 13, 4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Li, L.; Xiong, X.; Cai, J.; Cui, H.; Li, H. Short-term photovoltaic power prediction model based on variational modal decomposition and improved RIME optimization algorithm. Electronics 2025, 14, 3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Yang, C.; Ma, H.; Zhu, S.; Sun, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, J. Short-term power prediction of distributed PV based on multi-scale feature fusion with TPE-CBiGRU-SCA. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2024, 18, 3200–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, K.; Chen, J.; Guo, L.; Ke, C.; Liang, J.; He, D. A photovoltaic power prediction approach based on data decomposition and stacked deep learning model. Electronics 2023, 12, 2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Salguero, P.; Bueso-Sanchez, M.; Molina-Garcia, A.; Sanchez-Lozano, J. Spatio-temporal dynamic clustering modeling for solar irradiance resource assessment. Renew. Energy 2022, 200, 344–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, T. Multi-step power forecasting for regional photovoltaic plants based on ITDE-GAT model. Energy 2024, 293, 130468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnat, M.; Asadi, S.; Alemazkoor, N. A graph attention network framework for generalized-horizon multi-plant solar power generation forecasting using heterogeneous data. Renew. Energy 2025, 243, 122520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Luo, Y.; Yuan, S.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X.; Liu, B. Building electricity load forecasting based on spatiotemporal correlation and electricity consumption behavior information. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, F.; Yu, N.; Huang, G.; Chang, X.; Li, G. PV power forecasting method using a dynamic spatiotemporal attention graph convolutional network with error correction. Sol. Energy 2025, 300, 113770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Zou, Z.; Jiang, J.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z. GWTSP: A multi-state prediction method for short-term wind turbines based on GAT and GL. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 221, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Li, R.; Shi, L.; Lu, T. Distributed photovoltaic short-term power forecasting using hybrid competitive particle swarm optimization support vector machines based on spatial correlation analysis. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2023, 17, 3624–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Qi, X.; Liu, H.; Song, J. Deep belief network based k-means cluster approach for short-term wind power forecasting. Energy 2018, 165, 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Wang, J.; Fan, Y. Wind power forecasting method of large-scale wind turbine clusters based on DBSCAN clustering and an enhanced hunter-prey optimization algorithm. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 307, 118341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kou, M.; Li, R.; Qian, Y.; Li, Z. Ultra-short-term wind power forecasting jointly driven by anomaly detection, clustering and graph convolutional recurrent neural networks. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, D.; Yang, M.; Liang, C. CEEMDAN-SE-HDBSCAN-VMD-TCN-BiGRU: A two-stage decomposition-based parallel model for multi-altitude ultra-short-term wind speed forecasting. Energy 2025, 330, 136660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sun, W.; Li, Q. Power load forecasting and anomaly detection using a two-stage attention mechanism and deep neural networks. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 249, 112056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Xia, Y.; Lin, J.; Xiong, D.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Dynamic adaptive hierarchical TCN driven by IHOA-VMD optimization for short term load forecasting. Energy 2025, 335, 138074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, X. A regional distributed photovoltaic power generation forecasting method based on grid division and TCN-Bilstm. Renew. Energy 2026, 256, 123935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Liu, H.; Gan, W.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, N.; Ma, S. Short-term electric vehicle charging load forecasting based on TCN-LSTM network with comprehensive similar day identification. Appl. Energy 2025, 381, 125174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ren, X.; Zhang, F.; Gao, L.; Hao, B. A novel ultra-short-term wind power forecasting method based on TCN and Informer models. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 120, 109632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Su, L.; Li, Y. Wind power forecasting based on new hybrid model with TCN residual modification. Energy AI 2022, 10, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, W.; Wang, J.; Zhen, Z.; Wang, F. Ultra-short-term distributed PV power forecasting for virtual power plant considering data-scarce scenarios. Appl. Energy 2024, 373, 123890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Forecasting Model | Temporal Distribution Shift | Spatial Distribution Shift | Domain-Adversarial Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | GCN | No | No | No |

| M2 | GAT | No | Yes | No |

| M3 | GAT | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| M4 | GAT+TCN | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 0.0698 | 0.0705 | 0.0647 | 0.0652 |

| 1 h | 0.0781 | 0.0783 | 0.0763 | 0.0768 |

| 2 h | 0.0868 | 0.0863 | 0.0856 | 0.0851 |

| 3 h | 0.0921 | 0.0908 | 0.0901 | 0.0887 |

| 4 h | 0.1001 | 0.0954 | 0.0961 | 0.0943 |

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 0.0400 | 0.0398 | 0.0366 | 0.0364 |

| 1 h | 0.0425 | 0.0424 | 0.0422 | 0.0418 |

| 2 h | 0.0457 | 0.0457 | 0.0458 | 0.0453 |

| 3 h | 0.0477 | 0.0476 | 0.0478 | 0.0474 |

| 4 h | 0.0534 | 0.0511 | 0.0504 | 0.0492 |

| Weather | Forecasting Scales | NRMSE | NMAE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | ||

| Sunny | 15 min | 0.0490 | 0.0484 | 0.0363 | 0.0367 | 0.0332 | 0.0324 | 0.0235 | 0.0227 |

| 1 h | 0.0505 | 0.0501 | 0.0429 | 0.0438 | 0.0317 | 0.0308 | 0.0270 | 0.0258 | |

| 2 h | 0.0529 | 0.0523 | 0.0502 | 0.0503 | 0.0309 | 0.0303 | 0.0291 | 0.0286 | |

| 3 h | 0.0618 | 0.0594 | 0.0593 | 0.0579 | 0.0356 | 0.0346 | 0.0338 | 0.0332 | |

| 4 h | 0.0717 | 0.0698 | 0.0728 | 0.0666 | 0.0430 | 0.0398 | 0.0406 | 0.0376 | |

| Cloudy | 15 min | 0.0744 | 0.0745 | 0.0690 | 0.0696 | 0.0407 | 0.0408 | 0.0374 | 0.0366 |

| 1 h | 0.0876 | 0.0869 | 0.0855 | 0.0854 | 0.0447 | 0.0457 | 0.0448 | 0.0436 | |

| 2 h | 0.0934 | 0.0937 | 0.0933 | 0.0932 | 0.0466 | 0.0484 | 0.0461 | 0.0463 | |

| 3 h | 0.0971 | 0.0967 | 0.0952 | 0.0967 | 0.0479 | 0.0503 | 0.0508 | 0.0477 | |

| 4 h | 0.1034 | 0.1010 | 0.1032 | 0.1024 | 0.0566 | 0.0551 | 0.0554 | 0.0550 | |

| Rainy | 15 min | 0.0718 | 0.0713 | 0.0696 | 0.0694 | 0.0412 | 0.0410 | 0.0397 | 0.0397 |

| 1 h | 0.0783 | 0.0773 | 0.0801 | 0.0791 | 0.0453 | 0.0445 | 0.0441 | 0.0442 | |

| 2 h | 0.0907 | 0.0883 | 0.0912 | 0.0880 | 0.0489 | 0.0488 | 0.0490 | 0.0480 | |

| 3 h | 0.0963 | 0.0916 | 0.0963 | 0.0907 | 0.0507 | 0.0495 | 0.0509 | 0.0493 | |

| 4 h | 0.1051 | 0.0959 | 0.1064 | 0.0955 | 0.0574 | 0.0564 | 0.0542 | 0.0531 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Li, Q.; Bo, B.; Yang, P.; Li, X.; Wu, Z.; Wang, G.; Ren, H. A Domain-Adversarial Mechanism and Invariant Spatiotemporal Feature Extraction Based Distributed PV Forecasting Method for EV Cluster Baseline Load Estimation. Electronics 2025, 14, 4709. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234709

Zhao Z, Li Q, Bo B, Yang P, Li X, Wu Z, Wang G, Ren H. A Domain-Adversarial Mechanism and Invariant Spatiotemporal Feature Extraction Based Distributed PV Forecasting Method for EV Cluster Baseline Load Estimation. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4709. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234709

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zhiyu, Qiran Li, Bo Bo, Po Yang, Xuemei Li, Zhenghao Wu, Ge Wang, and Hui Ren. 2025. "A Domain-Adversarial Mechanism and Invariant Spatiotemporal Feature Extraction Based Distributed PV Forecasting Method for EV Cluster Baseline Load Estimation" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4709. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234709

APA StyleZhao, Z., Li, Q., Bo, B., Yang, P., Li, X., Wu, Z., Wang, G., & Ren, H. (2025). A Domain-Adversarial Mechanism and Invariant Spatiotemporal Feature Extraction Based Distributed PV Forecasting Method for EV Cluster Baseline Load Estimation. Electronics, 14(23), 4709. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234709