Abstract

This study evaluated the bioavailability, antioxidant response, and post-withdrawal retention of red and grey selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) in adult male Japanese quails. Birds were fed a basal diet supplemented with 0.5 or 5 mg/kg of red or grey SeNPs for 28 days, followed by a 7-day withdrawal period. Selenium distribution varies markedly by nanoparticle form and dose. Red SeNPs, particularly at 5 mg/kg, produced higher selenium accumulation in metabolic and circulating tissues, whereas grey SeNPs showed lower initial uptake but more selective deposition at specific sites. Antioxidant analysis revealed significant increases in hepatic GPx activity across all SeNP groups, with the strongest enhancement occurring at the 5 mg/kg level. Serum TAC was elevated predominantly in quails receiving high-dose red SeNPs. Retention–depletion analysis demonstrated that moderate doses supported stable selenium incorporation, whereas high doses resulted in accelerated post-withdrawal loss. Overall, red SeNPs acted as rapidly available selenium sources with pronounced antioxidant effects, while grey SeNPs provided slower, more sustained selenium delivery. These findings highlight the importance of nanoparticle form and dosage in optimizing selenium supplementation strategies for poultry.

1. Introduction

Selenium (Se) is an essential trace element required for the synthesis of selenoproteins involved in antioxidant defense, immune function, and reproductive performance in birds [1]. In poultry nutrition, selenium supplementation is routinely used to strengthen oxidative stability, support metabolic health, growth performance, and egg production [2,3,4]. However, the bioavailability and safety of traditional inorganic and organic selenium sources vary considerably, motivating the search for more efficient and less toxic alternatives [5,6,7]. Selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) have emerged as a promising form of supplemental selenium due to their lower toxicity, high surface reactivity, and ability to enhance antioxidant capacity at relatively low doses [8,9,10]. Recent studies across different stages of poultry production have demonstrated that nano-selenium supplementation can improve feed conversion efficiency, daily feed intake, average daily gain, carcass yield, and immune responsiveness, including enhanced resistance to bacterial challenges such as Salmonella Typhimurium [11,12]. These findings highlight the growing interest in nano-selenium as a functional nutritional strategy for improving poultry health and productivity. Among nano-selenium forms, red and grey SeNPs represent two distinct allotropes with fundamentally different physicochemical and biological properties [13,14,15]. Red SeNPs are typically amorphous or crystalline, forming spherical or rod-like particles, which are produced mainly through reduction of selenite by agents such as ascorbic acid or hydrosulfite, microwave irradiation, or chemical methods. Their amorphous structure confers high solubility, rapid dissolution, and increased surface reactivity, which contribute to their higher immediate bioavailability and functional incorporation into metabolic pathways [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. In contrast, grey SeNPs correspond to the thermodynamically stable hexagonal crystalline phase composed of polymeric selenium chains and six-membered rings, typically formed upon heating, vaporization, sublimation, or high-pressure conversion of the red allotrope [23,24,25,26,27]. Grey SeNPs exhibit greater structural order, lower solubility, and slower release kinetics, functioning more as a sustained selenium reservoir than a rapidly absorbed source [28,29,30,31]. Despite extensive characterization efforts, nanoscale mechanisms governing the red-to-grey transformation and its biological implications remain incompletely understood [32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. These differences suggest that nanoparticle form may influence absorption, tissue distribution, and overall selenium utilization, yet comparative information in poultry remains limited. Understanding the metabolic fate of different SeNP forms is essential for evaluating their nutritional and physiological value. Tissue selenium accumulation patterns provide direct insight into bioavailability, while antioxidant biomarkers such as glutathione peroxidase (GPx), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) reflect their functional incorporation into biological systems [1,2,39]. Moreover, monitoring selenium retention and depletion following dietary withdrawal can reveal whether selenium is rapidly mobilized or retained as a slow-release reserve. This study aimed to compare the effects of red and grey selenium nanoparticles, provided at two dietary concentrations, on selenium distribution, antioxidant responses, and post-withdrawal retention in adult male Japanese quails. By integrating tissue deposition patterns with enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant markers, our work provides new insight into how nanoparticle form and dose shape selenium bioavailability and physiological efficacy in poultry.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at the Nanofood laboratory of the Institute of Animal Science, Biotechnology and Nature Conservation, Department of Animal Husbandry, Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences and Environmental Management, University of Debrecen, Hungary. It was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the University of Debrecen (ethical permission number: 4/2021/DEMÁB). All methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations.

2.1. Reagents

Sodium selenite, Vitamin C, nitric acid 65% (AR grade), hydrogen peroxide, and hydrochloric acid 37% (AR grade) were obtained from VWR, International Ltd. (Lutterworth, Leicestershire, UK). Sodium borohydride 98% (AR grade) was purchased from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium).

2.2. Selenium Nanoparticle Preparation and Characterization

Red and grey selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) were prepared according to the protocol described in [9]. Red SeNPs were synthesized by reducing sodium selenite (Na2SeO3) with 1% ascorbic acid at room temperature for 30 min, producing a stable red colloidal solution. Grey SeNPs were generated by thermally converting the red particles at 85~95 °C for 2 h, inducing their transition into the hexagonal crystalline form. According to the characterization report in [9], red SeNPs measure approximately 80–120 nm, whereas grey SeNPs range from 90–150 nm according to TEM and DLS analyses. The UV–Vis spectra should show a purity exceeding 95%, with no detectable residual inorganic selenium species. All physicochemical properties were reproduced and confirmed in our laboratory using the same synthesis procedure.

2.3. Experimental Design

A total of 60 adult male Japanese quails (Coturnix japonica; 12 weeks of age) were used in 28-day and 35-day feeding trials. Birds were individually housed in wire cages under standardized environmental conditions (temperature: 25 ± 2 °C; photoperiod: 16 h light/8 h dark) to allow for precise monitoring of feed intake and health status. All birds had free access to feed and water throughout the experimental period, with approximately 18 g of feed offered per bird per day. Quails were randomly allocated into five dietary treatment groups (n = 12 per group) based on initial body weight to ensure uniformity among groups. The treatments were as follows:

C0 (Control): Basal diet without selenium nanoparticle (SeNP) supplementation.

T1: Basal diet supplemented with 0.5 mg/kg red SeNPs.

T2: Basal diet supplemented with 5 mg/kg red SeNPs.

T3: Basal diet supplemented with 0.5 mg/kg grey SeNPs.

T4: Basal diet supplemented with 5 mg/kg grey SeNPs.

The basal diet (Table 1) was formulated using soybean, corn, wheat and sunflower oil considering the nutrient requirements of breeder quails according to [40]. The premix included in the basal diet provided a background selenium content of 0.042 mg/kg. Consequently, the total selenium content in the diets was estimated to be 0.042 mg/kg (C0), 0.542 mg/kg (T1 and T3), and 5.042 mg/kg (T2 and T4). After 28 days of dietary supplementation, half of the birds from each treatment group (n = 6) were slaughtered for sample collection. The remaining birds continued for an additional 7 days on the unsupplemented basal diet (Nano selenium-free phase) and were slaughtered on day 35. This design allowed for the evaluation of both immediate and residual effects of dietary SeNP supplementation following a withdrawal period. Feed intake was recorded daily for each cage throughout the experimental period and expressed as g/bird/day.

Table 1.

Ingredients and nutrient composition of the diet.

2.4. Tissue Sampling

The birds (n = 6 per treatment group) were randomly selected and euthanized after 28 days. Tissue samples were taken from the following organs (n = 6): liver, kidney, blood (which was centrifuged in anticoagulant tubes at 3000 rpm for 15 min to separate red blood fraction (cells) and serum), testis, spleen, breast and eyes, which were washed using phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS) and stored at −80 °C until analyzed. The samples (0.5 g) were digested with 2.25 mL of concentrated HNO3 (65%) and 6.75 mL of concentrated HCl (37%), and then heated for 4 h at 80 °C. Selenium measurements were conducted using a Millennium Excalibur 10.055 atomic fluorescence spectrophotometer (AFS) (PSA, Orpington, UK).

The total retention % and depletion % of Selenium are the combined Se remaining in these organs (liver, kidney, red blood fraction (RBF), spleen) at 35 days from the remaining 30 birds, which were compared with the values from the same organs after 28 days according to the following formulas:

2.5. Antioxidant Biomarkers

Antioxidant indices were determined by measuring the levels of glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC). Liver homogenates were used to measure GSH-Px activity, while both liver and serum samples were analyzed for SOD and T-AOC. The following commercial assay kits were used: Invitrogen™ Glutathione Peroxidase (GSH-Px) Activity Kit (Cat. No. EEA010, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), Invitrogen™ Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Colorimetric Activity Kit (Cat. No. EIASODC, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and Antioxidant Assay Kit (Cat. No. KA1622, Abnova, Taipei, Taiwan). Absorbance was measured using a SPECTROstar Nano Microplate Reader (BMG LABTECH GmbH, Ortenberg, Germany).

2.6. Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.5.0. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Selenium concentrations in tissues were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with selenium nanoparticle form (red vs. grey) and dietary dose (0, 0.5, and 5 mg/kg) as fixed factors. Analyses were conducted separately for each organ. Feed intake, antioxidant parameters (GPx, SOD, and total antioxidant capacity), and total selenium content were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with dietary treatment as the independent factor. Selenium distribution among organs within a single treatment was analyzed using one-way ANOVA with organ as the factor. When significant effects were detected (p < 0.05), Tukey’s multiple comparison test (HSD) was applied.

3. Results

The effects of dietary selenium nanoparticles on selenium distribution, feed intake, antioxidant activity, and retention dynamics were evaluated in adult male Japanese quails. The results are organized to first describe tissue selenium deposition across treatments, followed by changes in antioxidant biomarkers, and finally the patterns of selenium retention and depletion after the withdrawal period.

Table 2 shows the selenium distribution in organs of Japanese quails and total selenium content after 28 days of SeNP supplementation. Selenium concentrations varied significantly among treatments and organs (p < 0.0001). The red SeNP treatments (T1 and T2) resulted in higher selenium concentrations in several metabolically active tissues, with the highest values observed in the T2 group. In this group, selenium levels reached 263.18 µg/kg ± 26 in red blood fractions, 128.86 µg/kg ± 1.6 in the liver, and 196.93 µg/kg ± 6.2 in breast muscle, indicating a dose-dependent increase for red SeNPs. The lower red SeNP dose (T1) also increased selenium concentrations in the spleen, RBFs and breast compared with the control. Grey SeNP supplementation showed a distinct accumulation pattern. The low dose (T3) resulted in lower selenium concentrations in the spleen and testis while maintaining comparable breast muscle selenium levels to the red SeNP groups. At the higher dose (T4), grey SeNPs produced marked increases specifically in the spleen and testis, whereas liver selenium levels were comparable to those observed in T2. Kidney selenium concentrations varied moderately among treatments, with a significant elevation only observed in the T2 group relative to the control. Selenium concentrations in the eyes remained relatively stable across all treatments. Moreover, the high-dose groups T2 and T4 showed higher total Se levels compared with the control. Overall, the groups supplemented with nanoparticles of selenium produced the highest selenium accumulation and distribution in different organs; grey SeNPs demonstrated a strong dose dependence, with substantial increases observed only at higher concentrations in the spleen and testis.

Table 2.

Selenium distribution in organs of Japanese quails and total selenium content after 28 days of SeNP supplementation.

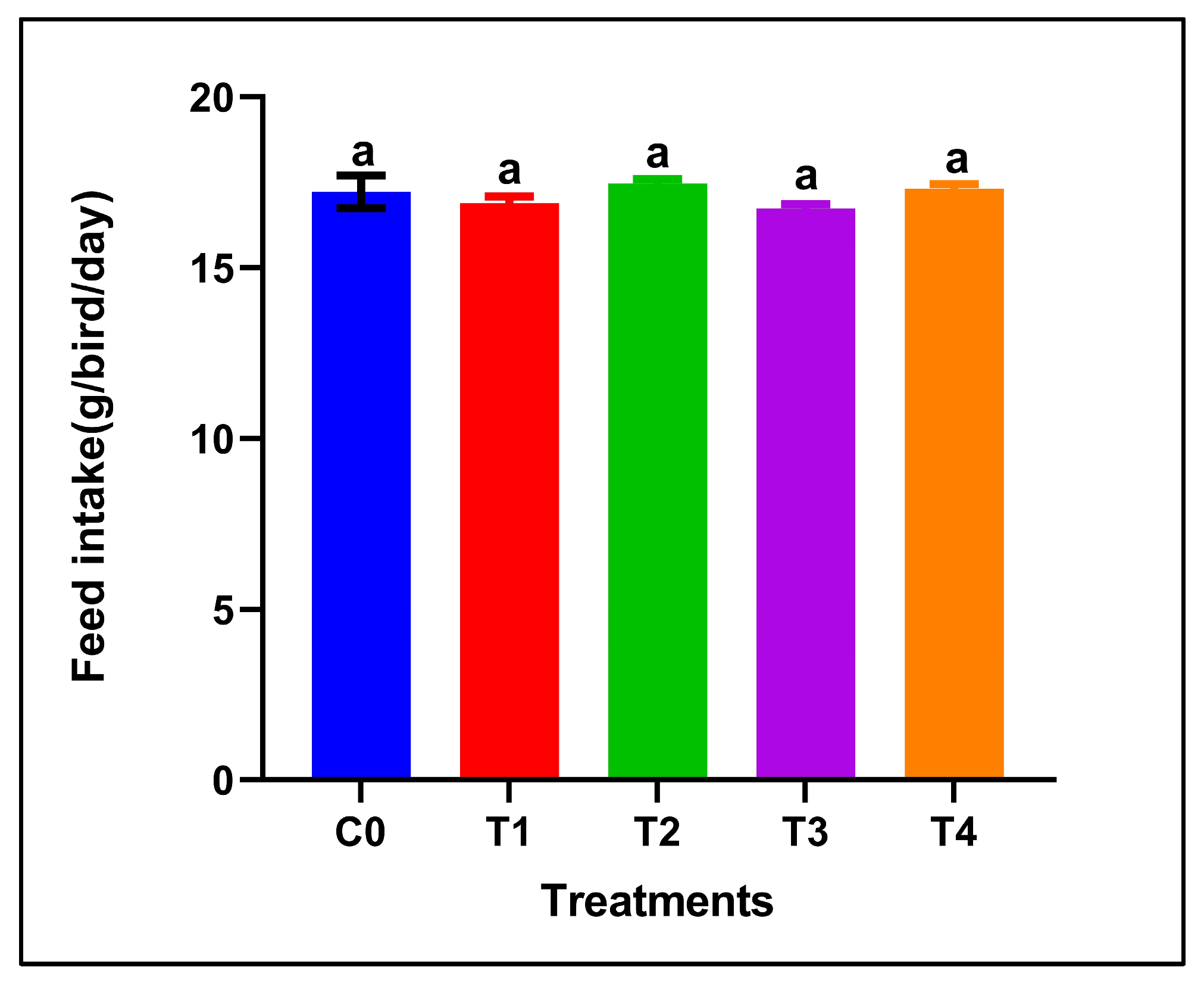

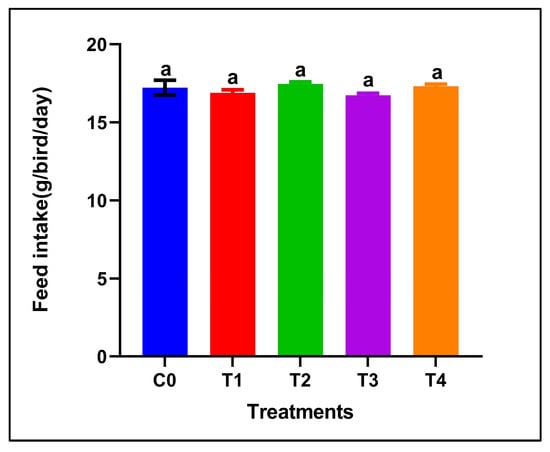

Dietary supplementation with red or grey SeNPs did not significantly affect feed intake throughout the 28-day feeding period (p > 0.05) (Figure 1). The mean FI remained comparable between the control and all supplemented groups, including the high-dose treatments (5 mg/kg), indicating normal feeding behavior and the absence of overt selenium-induced anorexia.

Figure 1.

Feed intake of adult male Japanese quails during 28 days of dietary supplementation with selenium nanoparticles. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. No significant differences were observed among treatments (p > 0.05).

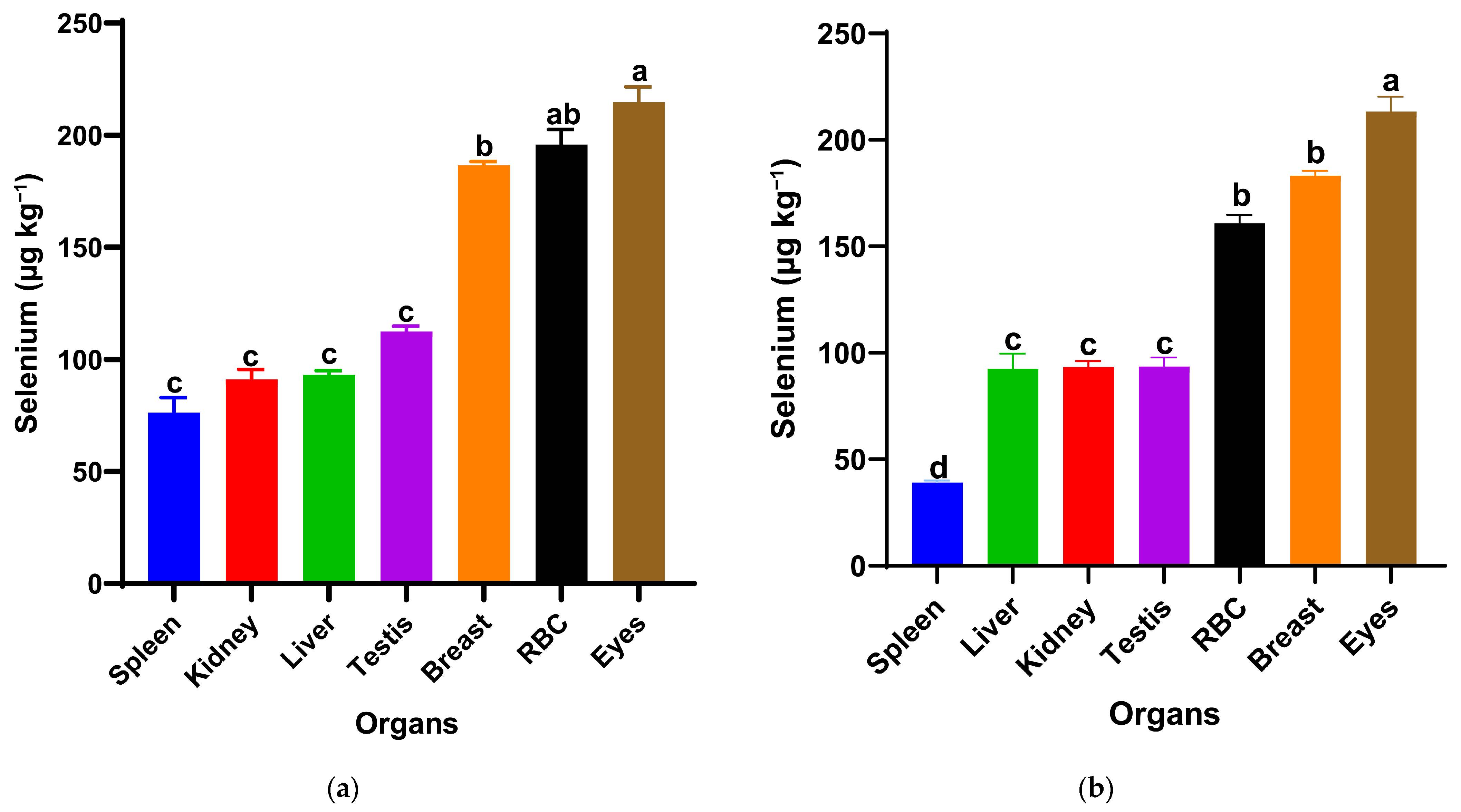

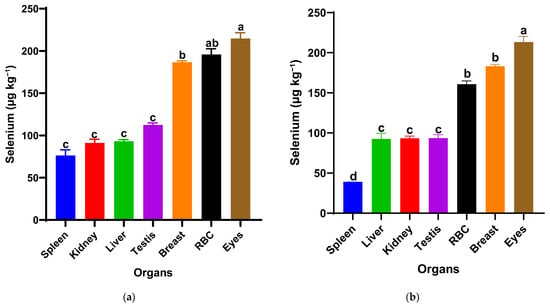

The selenium distribution notably differed between the two nanoparticle forms at the same dietary dose (0.5 mg/kg) in Figure 2. In the red SeNP group (T1) Figure 1a, selenium concentrations varied significantly among organs (p < 0.05). Red blood fraction selenium concentrations did not differ significantly from those in the eyes or breast muscle, whereas a significant difference was observed between the eyes and breast muscle, with the overall pattern being eyes ≥ RBF ≥ breast muscle > testis = liver = kidney = spleen. The highest levels were observed in the eyes, followed by the red blood fraction (RBF) and breast muscle, indicating relatively strong systemic availability and consistent deposition across tissues. The remaining visceral organs and testis showed lower but similar selenium concentrations (93–112 µg/kg), suggesting a homogeneous distribution pattern at this dose. In contrast, birds receiving the same dose of grey SeNPs (T3) in Figure 1b displayed a distinct deposition hierarchy of eyes > breast muscle = RBF > liver = kidney = testis > spleen (p < 0.05). While selenium levels in the eyes and breast muscle were comparable to those in T1, RBF selenium was notably lower, and spleen selenium accumulation was the lowest among all measured tissues (39.10 µg/kg ± 1). Overall, red SeNPs (T1) produced a slightly higher and more evenly distributed selenium profile across organs, whereas grey SeNPs (T3) resulted in reduced accumulation in circulating and immune tissues despite maintaining similar levels in muscle and ocular tissues.

Figure 2.

Selenium distribution in spleen, kidney, liver, testis, breast muscle, red blood cells (RBCs), and eyes of Japanese quails supplemented with red SeNPs ((a): T1, 0.5 mg/kg) and grey SeNPs ((b): T3, 0.5 mg/kg). Bars represent mean ± SEM. Different superscript letters within each treatment indicate significant differences in selenium concentration among organs (p < 0.05).

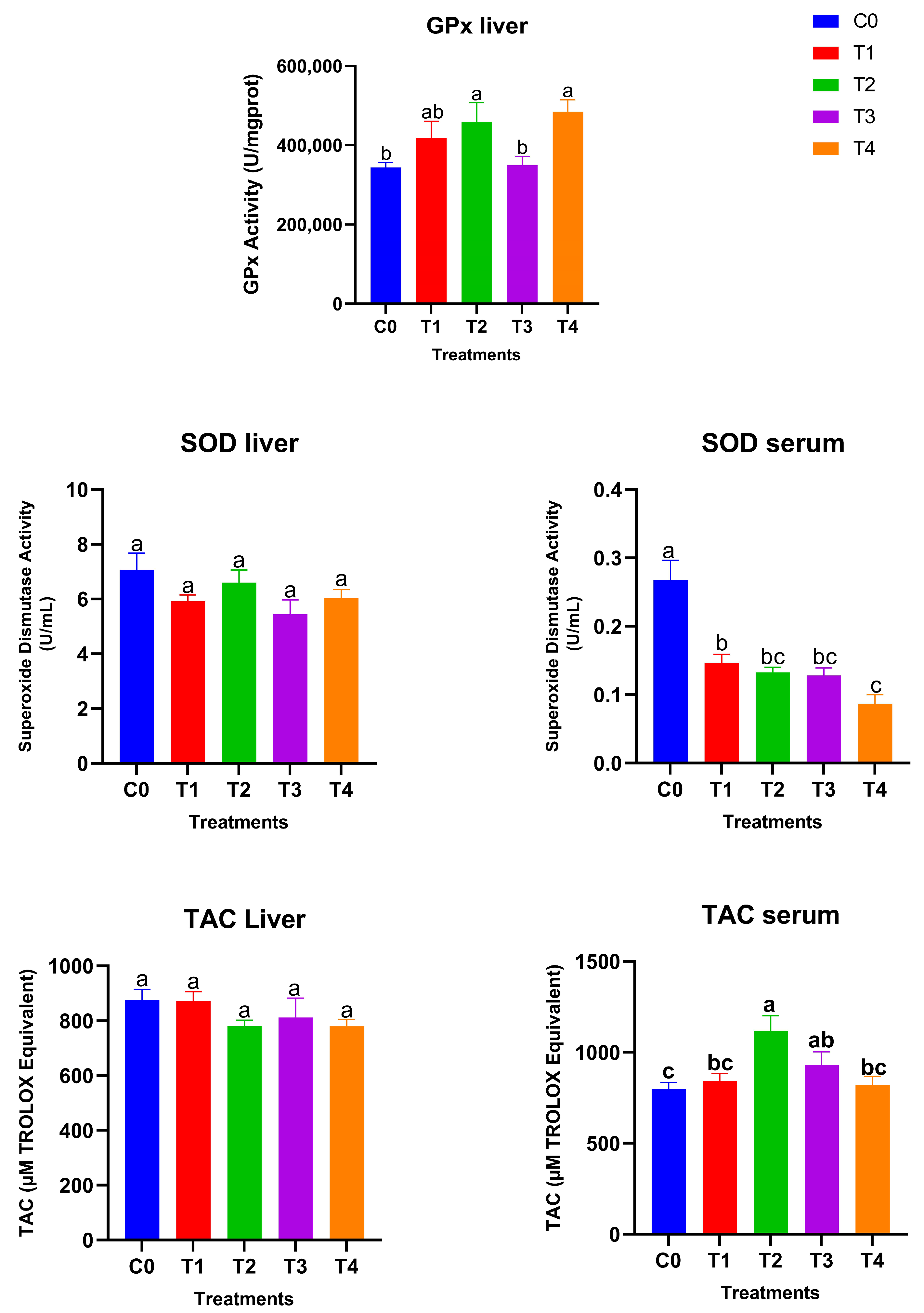

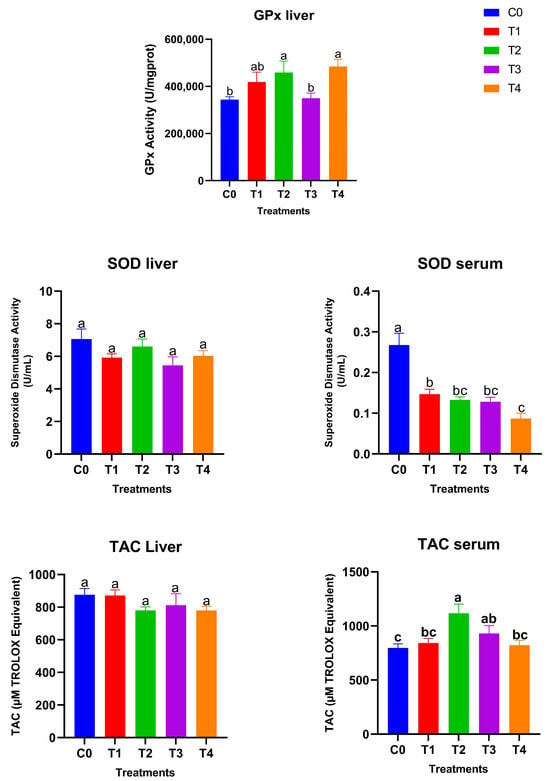

Figure 3 shows the glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity, superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels, and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) in liver and serum samples after 28 days of treatment. Hepatic GPx activity responded strongly to dietary selenium supplementation. The high-dose SeNP-treated groups showed significantly higher GPx activity compared with the control and low grey Se treatment T3, while T1 showed an intermediate value (p < 0.05), with the greatest increases observed in T2 (red SeNP, 5 ppm) and T4 (grey SeNP, 5 ppm). These findings indicate a clear dose-dependent enhancement of GPx-mediated antioxidant capacity in the liver, irrespective of nanoparticle form. In contrast, hepatic SOD activity remained statistically unchanged among treatments, suggesting that liver superoxide dismutase activity is relatively stable and not markedly influenced by selenium level or nanoparticle type. Serum SOD activity exhibited an opposite trend: all SeNP-supplemented birds showed significantly lower serum SOD activity than the control group (p < 0.05); the activity levels were still maintained within the normal reference range, suggesting that the improvement in selenium status reduced the systemic demand for circulating SOD. Liver TAC (Total antioxidant activity) values did not differ significantly among treatments, indicating that hepatic non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity was maintained across dietary groups. However, serum total antioxidant capacity differed significantly among treatments (p < 0.05). The highest serum TAC was observed in T2, which was significantly higher than the control, T1, and T4, but did not differ significantly from T3. In addition, the T3 group exhibited significantly higher serum TAC compared with the control, whereas no significant differences were detected among the control, T1, and T4 groups. Taking together, these results demonstrate that selenium nanoparticles enhanced antioxidant status primarily through GPx upregulation and improved systemic TAC, with red SeNPs at 5 ppm exerting the strongest overall effect. Grey SeNPs also increased GPx activity, but their impact on serum antioxidant capacity was less pronounced with high supplementation, indicating comparatively lower bioefficacy at equivalent high doses.

Figure 3.

Antioxidant biomarkers in liver and serum of Japanese quails fed diets supplemented with selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences among dietary treatments (p < 0.05).

Table 3 shows the total retention and depletion rate (in liver, kidney, spleen and red blood fraction RBF). The total selenium retention and depletion percentages revealed clear treatment-dependent patterns. Control birds exhibited the most stable selenium balance (96% retention, 3.9% depletion), reflecting normal homeostatic regulation. Among the supplemented groups, the low-dose treatments (T1 and T3) achieved the highest overall retention (91% and 88%, respectively), indicating efficient incorporation and stable maintenance of selenium during the withdrawal period. In contrast, higher doses (T2 and T4) showed markedly lower retention (78% and 57%). This drop is a direct consequence of the body reaching tissue saturation, which subsequently triggers enhanced excretion and biological regulatory mechanisms to rapidly clear the excess selenium once supplementation is withdrawn. Red SeNPs displayed higher initial bioavailability and retention overall (T1 was 91%), while grey SeNPs followed closely in second place, confirming that both nanoparticle forms lead to efficient selenium incorporation, but the clearance rate was primarily governed by the dose.

Table 3.

Total selenium retention and depletion rates in Japanese quails following SeNP supplementation and a 7-day withdrawal period.

Although red SeNPs exhibited the highest selenium retention and antioxidant enhancement, the grey form also demonstrated notable biological activity, indicating that selenium absorption and utilization persist even after the red-to-grey transformation. This transformation reflects structural stabilization rather than degradation; therefore, the conversion does not mark the end of the red SeNPs’ shelf life. Instead, the newly formed grey crystalline particles continue to act as sustained selenium reservoirs, gradually releasing selenium within tissues. The maintained, though reduced, selenium accumulation and antioxidant response in grey SeNP-treated groups suggest that both nanoparticle forms are metabolically active—red SeNPs provide rapid and high bioavailability, while grey SeNPs ensure longer-term selenium provision and stability.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that selenium nanoparticles exerted clear form- and dose-dependent effects on selenium deposition, post-withdrawal retention, and antioxidant responses in adult male Japanese quails [41,42,43,44]. Across all evaluated parameters, red and grey SeNPs behaved differently, reflecting their contrasting dissolution rates, bioavailability, and tissue affinities [12,45,46,47]. Red SeNPs, particularly at 5 mg/kg (T2), consistently produced the highest selenium levels in metabolic and circulating compartments, including the liver, red blood fraction (RBF), and breast muscle [17,48,49,50]. This pattern aligns with the known higher reactivity and faster dissolution of amorphous red selenium, enabling efficient intestinal absorption and rapid incorporation into selenoproteins [51]. The pronounced increase in hepatic GPx activity and elevated serum TAC observed in T2 further supports the notion that red SeNPs provide readily available selenium for antioxidant enzyme synthesis and systemic redox balance [52]. Despite the supranutritional selenium level used in the 5 mg/kg treatments, no clinical signs of selenium toxicity were observed during the 28-day feeding period as the birds maintained normal feed intake, normal behavior, and good overall health status. However, the low-dose Red SeNPs (T1) demonstrated high initial bioavailability and also the highest overall retention (91%) among all supplemented groups following dietary withdrawal, indicating highly efficient incorporation and maintenance [53]. In contrast, grey SeNPs exhibited slower and more selective accumulation patterns [14,50]. At the low dose (T3), grey SeNPs resulted in generally lower organ selenium concentrations compared with the equivalent red SeNP dose, confirming reduced bioavailability at small doses [50]. Nonetheless, T3 birds retained selenium more consistently during the withdrawal phase than T2 and T4, suggesting slower release and more prolonged tissue retention, but low-dose Red SeNP-treated T1 birds showed superior retention compared to T3 and showed the most stable maintenance overall during the withdrawal phase [54]. At the high dose (T4), grey SeNPs produced strong accumulation in specific organs, most notably in the spleen and testis, while showing a marked decrease in total retention after withdrawal, likely reflecting saturation of the storage capacity followed by compensatory mobilization or excretion of excess selenium after supplementation ceased. These findings indicate that higher selenium doses do not necessarily improve long-term retention and may reduce supplementation efficiency, highlighting the importance of moderate dosing to achieve sustained selenium status while maintaining safety [55,56]. Across all treatments, the eyes consistently displayed the highest selenium concentrations, independent of SeNP form or dose. This stability suggests a strong physiological requirement for selenium in ocular antioxidant defenses, likely driven by high GPx expression and the sensitivity of retinal tissues to oxidative stress [57,58]. Meanwhile, the spleen and visceral organs showed greater variability among treatments, indicating dynamic selenium redistribution associated with immune and metabolic processes [59,60]. The retention–depletion analysis provided further insight into the kinetic differences between nanoparticle types. Low doses (T1 and T3) resulted in the highest overall retention, whereas high doses (T2 and T4) were associated with accelerated clearance following the withdrawal period [55,57,61]. This dose-dependent clearance pattern suggests that moderate selenium supplementation supports stable tissue incorporation, while higher doses trigger homeostatic regulation and enhanced excretory responses to maintain physiological selenium balance [55,56,61]. Red SeNPs supported greater overall bioavailability and maintenance, with the low dose (T1) achieving the highest total retention among all supplemented groups. Grey SeNPs—particularly at the low dose—provided a sustained release profile that ensures longer-term availability due to their structure. Collectively, these findings highlight that selenium form and dose strongly influence the balance between absorption, utilization, tissue storage, and clearance in quails. Red SeNPs excelled in rapid antioxidant enhancement and systemic distribution, and had superior overall retention. In contrast, grey SeNPs showed distinct advantages in slower, targeted accumulation (spleen/testis) and a release mechanism designed for prolonged selenium provision [62,63].

5. Limitations and Perspectives

While the present study provides a robust physiological evaluation of red and grey selenium nanoparticles in adult male Japanese quails, several factors warrant further investigation. The responses observed here may vary with age, sex, and species, as selenium metabolism and antioxidant requirements are influenced by developmental stage, reproductive status, and genetic background. Additionally, environmental conditions, such as temperature, housing density, and oxidative stress load, may modulate selenium utilization and retention. Although growth performance has been addressed in our previous low-dose studies [41], the supranutritional level (5 mg/kg) examined here requires extended evaluation to define long-term safety margins. Future research should integrate comprehensive physicochemical characterization of nanoparticles alongside molecular analyses, including selenoprotein- and antioxidant-related gene expression, to clarify the underlying mechanisms. Moreover, exploring combined supplementation strategies, such as selenium nanoparticles with vitamin E or other bioactive compounds at varying doses, may provide synergistic benefits and improve nutritional provision. Collectively, these approaches will support the rational optimization of selenium nanoparticle use in poultry nutrition.

6. Conclusions

Selenium nanoparticles influenced selenium distribution and antioxidant status in quail tissues in a form- and dose-dependent manner. Red SeNPs demonstrated higher overall bioavailability, resulting in superior selenium deposition in metabolic tissues and stronger systemic antioxidant support (e.g., increased serum Total Antioxidant Capacity). In contrast, grey SeNPs exhibited a slower release profile and more selective accumulation at specific sites (e.g., spleen and testis), suggesting an advantage for prolonged selenium delivery. All SeNP treatments successfully enhanced the primary enzymatic defense (GPx), though moderate doses produced the most stable tissue incorporation, while higher doses accelerated selenium clearance due to tissue saturation. Ultimately, the study highlights the distinct and complementary properties of the red and grey SeNP forms, underscoring the necessity of selecting both the nanoparticle form and dose to achieve targeted nutritional and antioxidant benefits for poultry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F., A.M., G.P.-A., Á.B. and J.P.; Data curation, A.F.; formal analysis, A.F. and A.M.; methodology, A.F., A.M., G.P.-A., R.K. and J.P.; software, A.F., Á.B. and G.P.-A.; supervision, J.P.; validation, A.F.; writing—original draft, A.F.; writing—review and editing, A.F., G.T., D.S., Á.B., L.C., R.K., H.E.-R. and J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Stipendium Hungaricum Scholarship Program; the University of Debrecen Scientific Research Bridging Fund (DETKA); and the University of Debrecen Program for Scientific Publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee of the University of Debrecen (ethical permission number: 4/2021/DEMÁB; approval date: 22 July 2021). All methods were performed following the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to Reda Gebrehaweria K., Sawadi F., Doha Mohamad Khalifeh, Mequanint Gashew Achenef, Fadella Nur Almira, Eman Moustafa Abas Abdelbary, Aicha Nour Laouameria, Chaima Neji and Besbas Mohamed El Amine for their valuable assistance in euthanizing the animals and the sample collection. Their contributions were instrumental in the successful completion of this study. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4.1)) for grammatical editing and improving paragraph structure. The authors reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. This study is part of the doctoral dissertation of the first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SeNPs | Selenium nanoparticles |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TAC | Total antioxidant activity |

| RBF | Red blood fraction |

| Se | Selenium |

| AFS | Atomic Fluorescence Spectroscopy |

References

- Hefnawy, A.E.G.; Tórtora-Pérez, J.L. The Importance of Selenium and the Effects of Its Deficiency in Animal Health. Small Rumin. Res. 2010, 89, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiser, A.R. Heat Resilience and Dietary Antioxidants: Potential Salutary Effects of Hispanic and Indigenous Diets. Am. J. Med. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Moneim, A.-M.E.; Sabic, E.M.; Abu-Taleb, A.M.; Ibrahim, N.S. Growth Performance, Hemato-Biochemical Indices, Thyroid Activity, Antioxidant Status, and Immune Response of Growing Japanese Quail Fed Diet with Full-Fat Canola Seeds. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2020, 52, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, P.; Swain, R.K.; Mishra, S.K.; Behera, T.; Swain, P.; Mishra, S.S.; Behura, N.C.; Sabat, S.C.; Sethy, K.; Dhama, K.; et al. Effects of Dietary Nano-Selenium on Tissue Selenium Deposition, Antioxidant Status and Immune Functions in Layer Chicks. Int. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 10, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Liu, Y.-L.; Xie, C.-Y.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Y.-Q.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Yao, Y.; Huang, R.; Wu, X. Effects of Different Selenium Sources on Laying Performance, Egg Selenium Concentration, and Antioxidant Capacity in Laying Hens. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019, 189, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.Y.; Mahan, D.C. Comparative Effects of High Dietary Levels of Organic and Inorganic Selenium on Selenium Toxicity of Growing-Finishing Pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2001, 79, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadrup, N.; Ravn-Haren, G. Toxicity of Repeated Oral Intake of Organic Selenium, Inorganic Selenium, and Selenium Nanoparticles: A Review. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2023, 79, 127235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Basu, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Selenium Nanoparticles Are Less Toxic than Inorganic and Organic Selenium to Mice In Vivo. Nucleus 2019, 62, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandsuren, B.; Prokisch, J. Preparation of Red and Grey Elemental Selenium for Food Fortification. Acta Aliment. 2021, 50, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhateeb, F.S.O.; Ghazalah, A.A.; Lohakare, J.; Abdel-Wareth, A.A.A. Selenium Nanoparticle Inclusion in Broiler Diets for Enhancing Sustainable Production and Health. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagawany, M.; Qattan, S.Y.A.; Attia, Y.A.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Elnesr, S.S.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Madkour, M.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Reda, F.M. Use of Chemical Nano-Selenium as an Antibacterial and Antifungal Agent in Quail Diets and Its Effect on Growth, Carcasses, Antioxidant, Immunity and Caecal Microbes. Animals 2021, 11, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipović, N.; Ušjak, D.; Milenković, M.T.; Zheng, K.; Liverani, L.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Stevanović, M.M. Comparative Study of the Antimicrobial Activity of Selenium Nanoparticles with Different Surface Chemistry and Structure. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 624621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandsuren, B.; Prokisch, J. The Production Methods of Selenium Nanoparticles. Acta Univ. Sapientiae Aliment. 2021, 14, 14–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Fresneda, M.A.; Delgado Martín, J.; Gómez Bolívar, J.; Fernández Cantos, M.V.; Bosch-Estévez, G.; Martínez Moreno, M.F.; Merroun, M.L. Green Synthesis and Biotransformation of Amorphous Se Nanospheres to Trigonal 1D Se Nanostructures: Impact on Se Mobility Within the Concept of Radioactive Waste Disposal. Environ. Sci. Nano 2018, 5, 2103–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbank, R.D. The Crystal Structure of β-Monoclinic Selenium. Acta Cryst. 1952, 5, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varlamova, E.G.; Turovsky, E.A.; Blinova, E.V. Therapeutic Potential and Main Methods of Obtaining Selenium Nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambonino, M.C.; Quizhpe, E.M.; Jaramillo, F.E.; Rahman, A.; Santiago Vispo, N.; Jeffryes, C.; Dahoumane, S.A. Green Synthesis of Selenium and Tellurium Nanoparticles: Current Trends, Biological Properties and Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsivileva, O.; Pozdnyakov, A.; Ivanova, A. Polymer Nanocomposites of Selenium Biofabricated Using Fungi. Molecules 2021, 26, 3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramshini, H.; Rostami, S. Dual Function of Selenium Nanoparticles: Inhibition or Induction of Lysozyme Amyloid Aggregation and Evaluation of Their Cell-Based Cytotoxicity. Arch. Ital. Biol. A J. Neurosci. 2021, 159, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beleneva, I.; Kharchenko, U.; Kukhlevskiy, A.; Boroda, A.; Izotov, N.; Gnedenkov, A.; Egorkin, V. Biogenic Synthesis of Selenium and Tellurium Nanoparticles by Marine Bacteria and Their Biological Activity. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 38, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugarte, M.; Geraki, K.; Bentley, E.; Cox, R. Nanoprobe Synchrotron X-Ray Fluorescence Microscopy Reveals Selenium-Rich Spherical Structure in Mouse Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joschko, M.; Malsi, C.; Rapier, J.; Scharmann, P.; Selve, S.; Graf, C. Colloidal Spherical Stibnite Particles via High Temperature Metallo-Organic Synthesis. Nanoscale Adv. 2024, 6, 4450–4461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, A.B.A.; Kuriakose, S.; Monshipouri, M.; Khalid, F.A.; Walia, S.; Sriram, S.; Bhaskaran, M. UV Photochromism in Transition Metal Oxides and Hybrid Materials. Small 2021, 17, 2100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cywar, R.M.; Rorrer, N.A.; Hoyt, C.B.; Beckham, G.T.; Chen, E.Y.-X. Bio-Based Polymers with Performance-Advantaged Properties. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammed, T. Unravelling of Sulphur Selenium Unsaturation in MoS (2 – x) Sex with Efficient Acidic and Alkaline Hydrogen Evolution Reaction (Her). Master’s Thesis, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Fresneda, M.A.; Schaefer, S.; Hübner, R.; Fahmy, K.; Merroun, M.L. Exploring Antibacterial Activity and Bacterial-Mediated Allotropic Transition of Differentially Coated Selenium Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 29958–29970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niranjan, R.; Zafar, S.; Lochab, B.; Priyadarshini, R. Synthesis and Characterization of Sulfur and Sulfur-Selenium Nanoparticles Loaded on Reduced Graphene Oxide and Their Antibacterial Activity against Gram-Positive Pathogens. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvelous, C.; de Azevedo Santos, L.; Siegler, M.A.; Fonseca Guerra, C.; Bouwman, E. Redox Conversion of Cobalt(II)-Diselenide to Cobalt(III)-Selenolate Compounds: Comparison with Their Sulfur Analogs. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 2022, e202200445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmore, C. The Structure of Glassy and Liquid Sulfur Revisited. Glass Eur. 2025, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.K. Minerals. In Geology and Mineral Resources; Upadhyay, R.K., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 293–350. ISBN 978-981-9605-98-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zinke, J.; Bruhn, C.; Siemeling, U. A Stable Crystalline N-Heterocyclic Carbene with a 1,1′-Ferrocenylene Backbone and Benzylic N-Substituents. Z. Für Anorg. Und Allg. Chem. 2023, 649, e202200334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentkowska, A.; Pyrzyńska, K. The Influence of Synthesis Conditions on the Antioxidant Activity of Selenium Nanoparticles. Molecules 2022, 27, 2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Thounaojam, T.C.; Chowdhury, D.; Upadhyaya, H. The Role of Selenium and Nano Selenium on Physiological Responses in Plant: A Review. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 100, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ramady, H.; Omara, A.E.-D.; El-Sakhawy, T.; Prokisch, J.; Brevik, E.C. Sources of Selenium and Nano-Selenium in Soils and Plants. In Selenium and Nano-Selenium in Environmental Stress Management and Crop Quality Improvement; Hossain, M.A., Ahammed, G.J., Kolbert, Z., El-Ramady, H., Islam, T., Schiavon, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-3-031-07063-1. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Q.; Luo, H.; Lin, L.; Zhang, Q.; Yi, W.; Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Zuo, C.; Qi, J.; Tang, X. Effects of Biological Nano-Selenium on Yield, Grain Quality, Aroma, and Selenium Content of Aromatic Rice. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Miao, P.; Xu, Z.; Yi, X.; Yin, X.; Li, D.; Pan, C. Exploring the Mechanism of Nano-Selenium Treatment on the Nutritional Quality and Resistance in Plum Plants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 284, 116957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yu, K.; Xiao, Q.; Song, B.; Yuan, W.; Long, X.; Cai, D.; Xiong, X.; Zheng, W. Effect of Bio-Nano-Selenium on Yield, Nutritional Quality and Selenium Content of Radish. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 115, 104927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, R.; Cheng, H.; Wu, Y.; Tian, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, L.; Wang, C. Foliar-Selenium-Induced Modulation of Volatile Organic Compounds in Rice Grains: A Comparative Study of Sodium Selenite and Nano-Selenium. Foods 2025, 14, 3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Shi, P.; Li, Y.; Qian, S. GPX4 Is a Potential Diagnostic and Therapeutic Biomarker Associated with Diffuse Large B Lymphoma Cell Proliferation and B Cell Immune Infiltration. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council Subcommittee on Poultry Nutrition. Nutrient Requirements of Poultry: 1994; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ferroudj, A.; Muthu, A.; Sári, D.; Törős, G.; Béni, Á.; Czeglédi, L.; Knop, R.; El-Ramady, H.; Prokisch, J. Comparative Study of Red and Grey Selenium Nanoparticles on Organ-Specific Selenium Deposition and Growth Performance in Japanese Quails. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, Z.; Marghazani, I.B.; Chachar, B.; Shah, Q.A.; Shah, T.; Mengal, B.; Ujjan, N.A.; Bilal, M. Exploring the Nutraceutical Role of Selenium Nanoparticles on Laying Performance, Egg Attributes and Immune Response in Laying Hens. Indus J. Biosci. Res. 2025, 3, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaoye, A.B.; Owoeye, S.S.; Nwobegu, J.S. Facile Green Synthesis of Plant-Mediated Selenium Nanoparticles (SeNPs) Using Moringa oleifera Leaf and Bark Extract for Targeting α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Enzymes in Diabetes Management. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 7, 100281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbankova, L.; Skalickova, S.; Pribilova, M.; Ridoskova, A.; Pelcova, P.; Skladanka, J.; Horky, P. Effects of Sub-Lethal Doses of Selenium Nanoparticles on the Health Status of Rats. Toxics 2021, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hageman, S.P.W.; van der Weijden, R.D.; Stams, A.J.M.; Buisman, C.J.N. Bio-Production of Selenium Nanoparticles with Diverse Physical Properties for Recovery from Water. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2017, 169, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesnichaya, M.; Shendrik, R.; Titov, E.; Sukhov, B. Synthesis and Comparative Assessment of Antiradical Activity, Toxicity, and Biodistribution of κ-Carrageenan-Capped Selenium Nanoparticles of Different Size: In Vivo and In Vitro Study. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 14, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Teng, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Zeng, Q.-Z.; Lou, Z.; Lee, S.-H.; Wang, Q. Development, Physicochemical Characterization and Cytotoxicity of Selenium Nanoparticles Stabilized by Beta-Lactoglobulin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 107, 1406–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debata, N.R.; Sethy, K.; Swain, R.K.; Mishra, S.K.; Panda, N.; Maity, S. Supplementation of Nano-Selenium (SeNPs) Improved Growth, Immunity, Antioxidant Enzyme Activity, and Selenium Retention in Broiler Chicken During Summer Season. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2023, 55, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, C.; Florindo, H.F.; Santos, H.A. Selenium Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications: From Development and Characterization to Therapeutics. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, 2100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Guo, Y. Amorphous Structure and Crystal Stability Determine the Bioavailability of Selenium Nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, S.S. Selenium-Based Amorphous Semiconductors and Their Application in Biomedicine. In Electronic Devices, Circuits, and Systems for Biomedical Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Guleria, A.; Neogy, S.; Raorane, B.S.; Adhikari, S. Room Temperature Ionic Liquid Assisted Rapid Synthesis of Amorphous Se Nanoparticles: Their Prolonged Stabilization and Antioxidant Studies. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 253, 123369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeschner, K.; Hadrup, N.; Hansen, M.; Pereira, S.A.; Gammelgaard, B.; Møller, L.H.; Mortensen, A.; Lam, H.R.; Larsen, E.H. Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism and Excretion of Selenium Following Oral Administration of Elemental Selenium Nanoparticles or Selenite in Rats. Metallomics 2014, 6, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M. The Long-Term Biogeochemistry of 79 Se, 99 Tc, and 90 Sr in Complex Environmental Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Chemistry-Radiochemistry, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Burk, R.F.; Hill, K.E. Regulation of Selenium Metabolism and Transport. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2015, 35, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Huang, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Dong, Y. The Role and Mechanism of Essential Selenoproteins for Homeostasis. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Yu, H. Elemental Selenium at Nano Size Possesses Lower Toxicity without Compromising the Fundamental Effect on Selenoenzymes: Comparison with Selenomethionine in Mice—ScienceDirect. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 42, 1524–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christen, W.G.; Glynn, R.J.; Gaziano, J.M.; Darke, A.K.; Crowley, J.J.; Goodman, P.J.; Lippman, S.M.; Lad, T.E.; Bearden, J.D.; Goodman, G.E.; et al. Age-Related Cataract in Men in the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial Eye Endpoints Study: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015, 133, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, S.M.; Pirhajati Mahabadi, V. Selenium Nanoparticles Role in Organ Systems Functionality and Disorder. Nanomed. Res. J. 2018, 3, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, R.; Yang, Q.; Dong, Y.; Hou, Y.; Liu, G. Selenium Metabolism and Regulation of Immune Cells in Immune-Associated Diseases. J. Cell. Physiol. 2022, 237, 3449–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, R.-P.; Cheng, W.-H.; Zhu, J.-H. Prioritized Brain Selenium Retention and Selenoprotein Expression: Nutritional Insights into Parkinson’s Disease. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2019, 180, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmani, A.; Matijaković Mlinarić, N.; Falsone, S.F.; Vidaković, I.; Leitinger, G.; Delač, I.; Radatović, B.; Nemet, I.; Rončević, S.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A.; et al. Simulated Gastrointestinal Fluids Impact the Stability of Polymer-Functionalized Selenium Nanoparticles: Physicochemical Aspects. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 13485–13505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tışlı, B.; Nejati, O.; Torkay, G.; Giray, B.; Bal-Öztürk, A.; Bakırdere, S. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Selenium Nanoparticles: Bioactivity Insights. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202404483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.