Abstract

The rapid expansion of the Internet of Things (IoT) across domains such as industrial automation, smart healthcare, and intelligent transportation has intensified security challenges, particularly in terms of detecting anomalies across large-scale, heterogeneous networks. To address these challenges, this study introduces a blockchain-enabled hierarchical federated learning (Block-HFL) approach that combines federated model aggregation with blockchain-based authentication and immutable storage. This approach has enhanced scalability, reduced communication latency, and ensured trustworthy model management while preserving data privacy. In comparison with existing hierarchical and non-hierarchical FL approaches, the proposed Block-HFL framework introduces an accuracy-based leader election mechanism that enhances fairness and improves global model convergence. Experimental evaluations on the Edge-IIoTset dataset show that Block-HFL consistently maintains detection accuracy above 94% as the number of clients increases from 4 to 16, outperforming baseline FL models under similar non-IID conditions. Moreover, blockchain integration ensures secure, transparent, and tamper-proof global model management with minimal computational cost, confirming that the proposed framework provides an efficient and trustworthy solution for distributed anomaly detection in IoT systems.

1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) comprises a vast network of heterogeneous devices equipped with sensors, actuators, software, and network connections [1]. In recent years, the proliferation of IoT devices has accelerated: in 2020, the number of operational IoT devices worldwide exceeded 31 billion, with forecasts projecting an increase to 75 billion by 2025 [2]. As these numbers grow, IoT systems continue to transform multiple sectors, including smart thermostats, wearable fitness trackers, business sensors, and autonomous vehicles [1]. However, this expanding architecture introduces significant security and privacy concerns, as malicious actors can exploit device vulnerabilities to compromise sensitive Data [3]. Consequently, robust security measures are necessary to protect IoT devices and data during transmission.

To address these vulnerabilities, machine learning (ML) techniques have been increasingly adopted to enhance security in IoT contexts. An essential component of this defense ecosystem is the intrusion detection system (IDS) [4], which monitors network traffic and device activity to detect malicious behavior or policy violations in real time. IDSs are generally classified into two main analytical approaches: signature-based and anomaly-based detection. The former identifies attacks by matching observed patterns against a database of known threat signatures, providing high accuracy for previously recorded attacks but limited adaptability to emerging threats. In contrast, anomaly-based detection involves constructing a model of normal device or network behavior and flagging any significant deviations that may indicate intrusions, cyberattacks, or system malfunctions [4]. Due to their ability to detect novel and unknown attacks, anomaly-based detection approaches have become increasingly crucial in IoT environments. However, traditional ML-based anomaly detection still faces challenges such as unauthorized data exposure and reliance on centralized architectures, potentially introducing single points of failure [5]. Consequently, recent research has focused on the use of decentralized learning paradigms, such as federated learning (FL), to address these limitations and improve scalability, privacy, and resilience in IoT-based intrusion detection systems.

Federated learning (FL) has emerged as a promising paradigm for addressing the challenges of ML-based anomaly detection. This approach enables collaborative model training across distributed devices without sharing raw data; instead, model updates are aggregated at a central aggregator. FL offers advantages such as data heterogeneity and privacy preservation. However, frequent model aggregation and communication with a central server can increase the latency and bandwidth consumption, limiting the scalability of FL in large IoT deployments and negatively impacting overall performance [6]. These constraints have motivated the development of more efficient federated architectures.

Hierarchical federated learning (HFL) addresses these challenges by introducing an intermediate fog layer, which represents a distributed computing tier positioned between IoT devices and the cloud [7]. It consists of multiple fog servers that provide localized storage, computation, and aggregation services closer to data sources [7]. This layer locally aggregates updates from closely related IoT devices before final cloud aggregation [8,9]. This structure improves scalability and reduces latency by distributing the computations and reducing network traffic. However, the use of fog servers introduces new security and trust concerns; for example, if a fog server is compromised or acts maliciously, it can tamper with model updates and undermine the integrity of the global model [10]. Thus, ensuring the security and authenticity of the global model is critical to maintaining system reliability.

To strengthen trust in HFL environments, blockchain technology has gained attention as a complementary solution. A blockchain operates as a decentralized ledger that records transactions across a peer-to-peer network using cryptographic hashes, ensuring transparency, immutability, and tamper-resistance [11]. When integrated with FL, a blockchain ensures model provenance and guarantees that the recorded updates cannot be altered or deleted, thus preserving model integrity. At the same time, only authorized fog servers can store the aggregation results [12].

This study proposes Block-HFL, a blockchain-enabled hierarchical federated learning framework developed to enhance the security, scalability, and trustworthiness of anomaly detection in IoT environments. This framework is designed for deployment in real-world IoT environments that require distributed intelligence and strong data confidentiality, with typical application domains including smart healthcare (e.g., wearable sensors that monitor patient health) and industrial IoT (IIoT; e.g., anomaly detection in production systems or factory networks). These domains involve large numbers of heterogeneous, resource-constrained devices that cannot rely on a single centralized server due to privacy risks and scalability limitations. The Block-HFL framework addresses these challenges by distributing the computations among fog servers and employing blockchain-based accountability to ensure integrity and trust. The contributions of this work are as follows:

- We propose a blockchain-enabled hierarchical federated learning (Block-HFL) framework in which fog servers perform partial aggregations and the elected leader conducts the final aggregation. This architecture minimizes the communication overhead and improves scalability.

- We incorporate blockchain-based authentication into the model to authorize participating servers and immutably record global model updates using smart contracts and the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS).

- We propose an accuracy-based leader election mechanism in the HFL context, where fog servers locally aggregate client updates, and the fog server with the highest validation accuracy is dynamically selected as the leader for global aggregation. This adaptive strategy enhances model convergence and fairness.

- We validated the framework using the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, and compared these values with those reported in relevant works. The results demonstrated a reduced training time and the maintenance of a high accuracy across 4, 8, and 16 clients, highlighting the robustness and scalability of the proposed approach.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews recent advancements in FL for IoT and intrusion detection. Section 3 details the proposed methodology. Section 4 presents and analyzes the experimental data. Section 5 discusses the results and key findings. Finally, Section 6 concludes the article and outlines potential future research directions.

2. Background and Related Work

This section provides essential background on federated learning techniques. It also reviews related studies to highlight their key contributions and limitations, thereby clarifying the research gap that motivates the proposed Block-HFL framework.

2.1. Centralized Aggregation

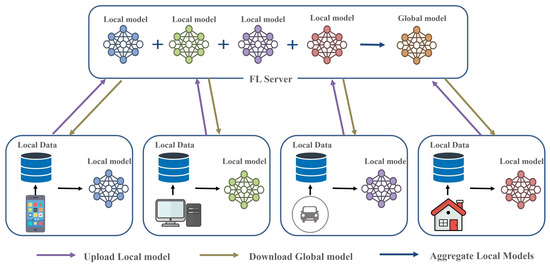

Figure 1 illustrates the centralized federated learning (CFL) process. IoT devices train local models on private datasets and send their updated weights to a single central server. Different colors are used solely to distinguish local models from those of different clients. The central server aggregates all the received models into a global model and redistributes them back to the devices. This architecture improves data privacy compared to centralized ML, but introduces a single point of failure and scalability bottlenecks at the server.

Figure 1.

Centralized federated learning (CFL).

Ferrag et al. [13] proposed a seven-layer IoT/IIoT testbed architecture to generate a realistic cybersecurity dataset, namely, the edge industrial Internet of Things set (Edge-IIoTset). The authors evaluated several machine learning and deep learning models on this dataset, including a decision tree (DT) [14], random forest (RF) [15], a support vector machine (SVM) [16], XGBoost [17], and a deep neural network (DNN) [18], in both centralized and federated learning modes. Their results demonstrated that the Edge-IIoTset supports traditional and privacy-preserving IDS research under realistic network conditions.

Significant concerns about data privacy, service continuity, and network adaptability arise when utilizing wearable IoT devices in predictive healthcare. To address these issues, Baucas et al. [19] developed an IoT platform that preserves privacy by preventing the transfer of raw data through local training on wearable devices. Centralized aggregation is performed to produce a global model, thus reducing privacy risks. The researchers used fog nodes to offload intensive tasks from wearables, improving the scalability and adaptability of their approach. The global federated model achieved an accuracy of 91.75%, thus outperforming local models.

Rajagopal et al. [20] introduced FedSDM, an FL module for edge–fog–cloud healthcare systems that enables efficient electrocardiogram (ECG) anomaly detection while satisfying privacy, latency, and computational efficiency requirements. The framework combines the federated averaging (FedAvg) aggregation algorithm with an autoencoder-based anomaly detector [21], thereby preserving data privacy while improving the computational performance. The simulation results indicated that edge deployment achieved the lowest latency and energy consumption, with the fog nodes outperforming cloud placement. FedSDM achieved higher accuracy, reduced training time, and lower training loss than the baseline methods, demonstrating its strong potential for real-time healthcare IoT applications.

Niyomukiza et al. [22] addressed security concerns in industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) by proposing an unsupervised federated learning framework using a deep autoencoder. Their approach showed improved privacy and adaptability across distributed devices when compared to centralized anomaly detection systems, which rely on labeled datasets and centralized data collection. The authors first evaluated a baseline model that combined FedAvg with an autoencoder-based anomaly detector, then introduced a fair federated averaging (FairFedAvg) algorithm to mitigate the fairness and communication challenges caused by device heterogeneity. Their results showed that the federated model performed comparably to centralized training while reducing the false positive rate (FPR) from 0.49% to 0.16–0.20%, demonstrating the advantage of decentralized learning in lowering false alarms.

Rashid et al. [23] addressed IIoT network security using machine learning-based IDSs. Centralized IDSs require large amounts of sensitive data to be sent to a central server, increasing risks related to privacy, communication, and failure. Therefore, the authors proposed a federated learning IDS that enables IoT devices to build deep learning models using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), sharing only updated models for central aggregation, thereby maintaining privacy while reducing communication overhead. In tests on the Edge-IIoTset dataset, the federated system achieved 92.49% accuracy, which is close to that of the centralized model (93.92%), while maintaining better privacy. When tested under both IID and non-IID settings, the global federated model’s accuracy consistently increased across rounds and converged toward the centralized model’s accuracy.

The results obtained through centralized aggregation in FL approaches demonstrate that privacy-preserving model training without direct data sharing is feasible. The application of such approaches in the healthcare and IIoT domains has yielded a competitive accuracy and reduced frequency of false positives [19]. However, reliance on a single central server for model aggregation introduces drawbacks such as communication bottlenecks, single points of failure, and limited scalability in large heterogeneous IoT environments [8].

2.2. Hierarchical Aggregation

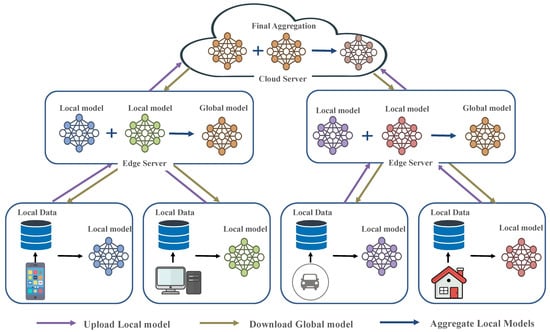

Figure 2 illustrates the hierarchical federated learning (HFL) process. Local IoT devices perform on-device training and upload their model updates to nearby edge servers. Each edge server aggregates local updates to form an intermediate model, which is then sent to the cloud server for final aggregation. This multi-tier structure reduces the communication latency and balances the computation load between the edge and cloud layers.

Figure 2.

Hierarchical federated learning (HFL).

The substantial communication overhead in FL increases with frequent cloud aggregations, particularly when the data distributions are imbalanced. To address this, Deng et al. [8] introduced an HFL framework and designated edge nodes as intermediate aggregators to reduce the dependence on cloud updates. While optimizing HFL, they developed SHARE: a method that reduces communication costs by strategically selecting edge aggregators and their associated nodes, encouraging a more balanced data distribution at the edge. They also presented two algorithms: a greedy-based node association and a local search for aggregator selection, both of which minimize communication costs. Under real-world network topologies, experimental results on the Modified National Institute of Standards and Technology (MNIST) [24] and Canadian Institute for Advanced Research 10 classes (CIFAR-10) [25] datasets demonstrated that SHARE significantly reduced the communication costs while maintaining (or even improving) accuracy levels comparable with those of cloud-based FL and other benchmarks.

Building on these hierarchical edge-aggregation strategies, FL faces scalability challenges when deployed in large-scale networks. In such settings, star topologies create bottlenecks at the cloud server, leading to aggregation delays and an increased computational burden. To address this, Dinh et al. [9] proposed a decentralized edge network architecture. Their approach shifts a substantial portion of the aggregation tasks from the cloud to edge nodes using in-network computation (INC). Their design incorporates an in-network aggregation mechanism with a joint routing and resource allocation algorithm, thereby reducing the latency. As the problem is NP-hard, the authors developed a polynomial-time randomized rounding algorithm and established performance bounds. According to the simulation results, the framework reduced the aggregation latency and cloud overhead while supporting large models, such as ResNet-15.

Even with these improvements, there are drawbacks to hierarchical strategies that rely on edge-level aggregation to reduce the latency and server load while maintaining high accuracy. The main issue is their reliance on intermediate edge nodes, which can create security and trust concerns. If these edge devices are attacked or untrustworthy, they could compromise the aggregated models [26].

2.3. Blockchain-Based Aggregation

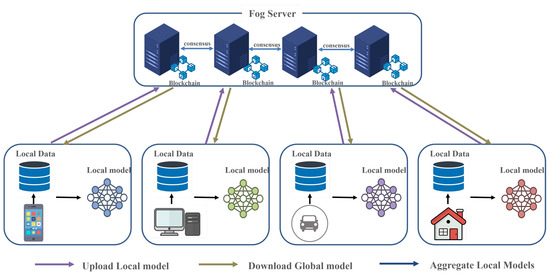

In blockchain-based FL, Figure 3 shows the Blockchain-based federated learning (BFL) process. IoT devices train local models on local data and upload updates to fog servers for aggregation. The fog servers record the aggregation results on a blockchain through a consensus mechanism, ensuring integrity, transparency, and tamper-resistant model updates. Each device downloads the verified global model from the blockchain, eliminating the need for a trusted central authority.

Figure 3.

Blockchain-based federated learning (BFL).

Dias [26] introduced BlockLearning: a modular, open-source, blockchain-based federated learning framework that integrates Ethereum [27] and TensorFlow [28]. In this context, the term ‘framework’ refers to a computational software architecture that combines a blockchain and federated learning components. Ethereum serves as the underlying blockchain platform, supporting smart contracts that automate model submission, validation, and record-keeping within the federated learning process, while TensorFlow provides a machine learning environment for model training and aggregation. Their study offered a comparative analysis of consensus algorithms [29], participant selection, and scoring mechanisms, evaluating their impacts on latency, cost, accuracy, and convergence. They also implemented vertical federated learning on the blockchain, advancing beyond prior theoretical work. Their results highlight the trade-offs among computation, communication, and accuracy, demonstrating how client numbers and privacy mechanisms affect performance. However, their study offered only a limited analysis of the framework’s scalability for large-scale Internet of Things deployments, indicating a need for further research in complex real-world environments.

Lo et al. [30] identified accountability and fairness as ongoing challenges in federated learning systems, particularly in sensitive applications such as medical imaging for COVID-19 detection. They proposed a blockchain-based architecture that integrates a smart, contract-driven, data-model provenance registry to ensure accountability and a weighted fair data-sampling algorithm to address non-IID data. Their experimental results demonstrated that the framework enhanced the fairness, generalizability, and accuracy of the model, while the blockchain operations introduced minimal latency, underscoring the practicality of this framework for real-time applications.

In 2025, Rajagopal et al. [31] introduced FedSDM, a federated decision-making framework that incorporates blockchain technology for IoT-based healthcare, with a focus on electrocardiogram (ECG) anomaly detection. Their approach combines FL with blockchain smart contracts to ensure the transparent and tamper-resistant management of global model updates. An autoencoder detects anomalies across the edge, fog, and cloud-computing layers. Their evaluation indicated that edge deployment outperformed the fog and cloud in terms of latency, execution time, cost, and network usage. The integration of blockchain technology significantly enhanced the transparency and verifiability, with minimal increases in energy consumption or computational load. Thus, blockchain-based FL enhances accountability, fairness, and transparency by providing verifiable updates to the global model and increasing trust in sensitive areas, such as healthcare. Despite these benefits, the existing research remains constrained by problems related to scalability and additional overhead.

Lu et al. [32] introduced a framework that integrates digital twin technology, FL, and a permissioned blockchain [33] to enhance the communication efficiency, data security, and privacy in IoT edge networks. Digital twin edge networks (DITENs) generate virtual representations of IoT devices for reduced latency and to enable real-time decision making. The framework employs a blockchain-based federated learning approach, incorporating asynchronous model aggregation and reinforcement learning to optimize resource allocation and user scheduling. Experiments on benchmark datasets, including MNIST and Fashion-MNIST, demonstrated that the framework achieved an accuracy comparable to that of conventional FL while reducing the communication overhead and system costs. Additionally, reliance on a permissioned blockchain may limit the scalability and interoperability of such frameworks across diverse environments.

2.4. Hybrid FL

Liu et al. [34] proposed a blockchain-enabled FL framework to address security and privacy challenges in vehicular edge computing networks. In this framework, vehicles receive a pre-trained intrusion detection model from roadside units (RSUs), update the model locally with new traffic data, and upload the updated results to the RSUs. The RSUs then aggregate these updates into a global model. In this context, blockchain technology offers tamper-proof storage and mitigates the risks associated with centralized aggregation. Their performance analysis investigates model accuracy, training time under varying dataset sizes and epochs, and the impact of different consensus mechanisms on block generation time, showing that the scheme can achieve high accuracy with moderate computational and communication cost.

However, this model does not account for non-IID data distributions, limiting its applicability in heterogeneous real-world environments; additionally, the consensus mechanism introduces high latency.

2.5. Comparative Analysis of Related Work

We summarize the related works in Table 1, including the proposed models, aggregation techniques, FL frameworks, aggregation functions, algorithms, and datasets.

Table 1.

Summary of the related literature.

The comparative analysis shown in Table 2 demonstrates that, although several existing studies have integrated federated learning with blockchains or edge computing, most frameworks encounter persistent challenges in achieving scalability, communication efficiency, and trust management. Studies assessing centralized aggregation in federated learning architectures (e.g., [13,22,23]) have used the same dataset (Edge-IIoTset) for IDS evaluation, providing a consistent basis for a performance comparison; however, they remain constrained by communication bottlenecks and are vulnerable to single points of failure. Hierarchical federated learning approaches (e.g., [8,9]) provide improved scalability, but lack adequate security and accountability mechanisms. In contrast, blockchain-based frameworks (e.g., [26,30,31]) offer transparency and fairness through immutable ledgers, but introduce a significant computational overhead and an increased delay. Collectively, these findings indicate that no existing framework fully satisfies the combined requirements for scalability, low latency, and trust in distributed IoT environments. The proposed Block-HFL architecture addresses these limitations by integrating hierarchical aggregation with blockchain-based authentication and storage. This multi-tier hierarchical aggregation strategy reduces the latency and communication overhead by distributing the model training and aggregation tasks across fog nodes, which alleviates the bottlenecks associated with a single central coordinator. In parallel, the blockchain layer ensures secure authentication and tamper-proof storage of global model updates on an immutable ledger. This approach also enables the development of a decentralized, reliable leader election mechanism among fog nodes. The combined design maintains system efficiency and distribution while preserving trust and accountability.

Table 2.

Comparison of the related literature.

3. Proposed Model

3.1. System Architecture

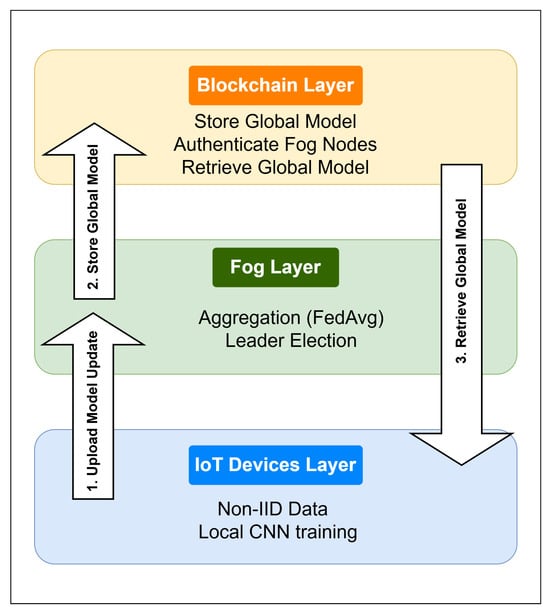

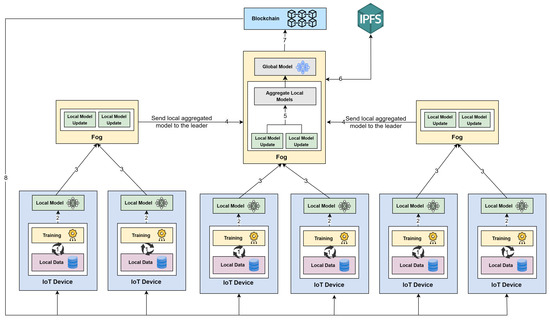

Figure 4 illustrates the system architecture of the proposed Block-HFL system. This architecture employs a three-layer paradigm consisting of the IoT device layer, the fog layer, and the blockchain layer. It utilizes Google Remote Procedure Call (gRPC) clients and servers for communication [35], an on-chain registry, and off-chain storage in the IPFS [36]. The system supports privacy-preserving local training, robust and accurate aggregation at the fog layer, and tamper-evident transparent dissemination of the global model.

Figure 4.

High-level layered architecture.

3.1.1. IoT Device Layer

In the proposed Block-HFL framework, IoT devices (e.g., sensors and lightweight gateways) perform local training on their private data using the same lightweight CNN architecture implemented across all clients. Each device executes anomaly detection locally by training the CNN on its non-IID shard of the Edge-IIoTset dataset, allowing the model to learn device-specific traffic patterns and detect abnormal behavior. After completing local training, each client transmits its model weights to its assigned fog server. Server assignment is predefined in the system configuration, where each client is mapped to a specific fog server based on the experimental setup. The detailed procedures for preprocessing and model configuration are expanded in Section 4.

3.1.2. Fog Layer

In the proposed framework, multiple fog servers operate as intermediate aggregators positioned between IoT devices and the blockchain layer. Each fog server receives local model updates from its assigned IoT devices and performs an independent local aggregation using the FedAvg algorithm. After performing this independent aggregation, each fog server evaluates its aggregated model on a shared IID validation shard to estimate its accuracy, using the same evaluation procedure as IoT devices (see Section 3.3). The fog server with the highest validation accuracy is selected as the leader for that round via an accuracy-based leader-election mechanism. This fog layer design mitigates communication bottlenecks, addresses non-IID data heterogeneity across devices, and reduces reliance on a single central aggregator.

3.1.3. Blockchain Layer

The blockchain layer ensures secure, authenticated, and tamper-resistant management of global model updates. A local Ethereum network is instantiated using Ganache (v2.7.1, Truffle Suite, Austin, TX, USA), and smart contracts implemented in Solidity and accessed through Web3.py (v7.11.1, Ethereum Foundation, Zug, Switzerland) authorize fog servers before they can submit updates. To avoid the cost of on-chain storage, the leader fog server uploads the global model to an IPFS node (IPFS HTTP Client v0.7.0, Protocol Labs, San Francisco, CA, USA) and records only the resulting Content Identifier (CID) and metadata (e.g., round ID, server address) on the blockchain. This combination of authorization, off-chain storage, and immutable on-chain provenance enhances accountability and preserves model integrity across the federated learning process. Detailed implementation steps are provided in Section 3.2.

3.2. Block-HFL for Anomaly Detection

In the FL model, all the clients train local models initialized with a shared global model on their own datasets. Each fog server aggregates the model weights obtained from its clients and generates an updated global model with optimized parameters using Equation (1), and also evaluates the corresponding accuracy. The fog server with the highest accuracy receives the model from other fog servers, performs the final aggregation using Equation (2), and submits the global model to the blockchain. Both equations are based on the FedAvg algorithm [37]. The definitions for the main notation used in this work are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Notation used in this study.

At the first level, each fog server j aggregates the model weights received from its associated IoT devices as follows:

where denotes the local model parameters derived from training on IoT device i and represents the aggregated model parameters at fog server j. This operation follows the FedAvg principle, ensuring that the local models contribute equally within each fog cluster.

At the second level, the elected leader fog server performs the final global aggregation across all m fog servers to obtain the updated global model:

where represents the global model parameters for the current training round and m denotes the total number of participating fog servers.

Figure 5 depicts the workflow of the proposed Block-HFL system, outlining the sequential interactions among the IoT devices, fog servers, and blockchain during each federated learning round. The process comprises eight main steps:

- (1)

- Local Training on IoT Devices: On each IoT device, a CNN model is trained in parallel on its non-IID dataset, generating a set of local weights. The convolutional operation in the nth layer of the CNN model is mathematically defined as follows:where ∗ denotes the convolution operator, is the nonlinear activation function (ReLU in this work), and represents the jth feature map in the nth layer. The term corresponds to the kth input channel of the th layer, denotes the convolutional kernel (filter) connecting the kth input channel to the jth output feature map, and is the bias term associated with the jth filter. The activation function introduces nonlinearity, enabling the CNN to capture complex spatial dependencies in the IoT data.

- (2)

- Model Update Submission: After completing local training, the IoT devices transmit their local model weights to the assigned fog servers via a secure gRPC channel. gRPC is a high-performance communication framework built on HTTP/2 that enables efficient, low-latency, bidirectional data exchange using binary serialization via Protocol Buffers. It supports SSL/TLS encryption to protect the model parameters during transmission, ensuring their confidentiality and integrity while allowing multiple clients to communicate with fog servers concurrently. Only the model parameters are shared, preserving the privacy of the local data.

- (3)

- Local Aggregation on Fog Server: Each fog server applies the FedAvg algorithm using Equation (1) to the received client weights to obtain a locally aggregated model. This approach reduces the communication overhead compared to direct cloud aggregation.

- (4)

- Leader Election: Each fog server independently evaluates its locally aggregated model on a shared independent and identically distributed (IID) validation dataset for model performance assessment. An evaluation metric—typically the validation accuracy—is calculated to assess the server’s reliability in the current training round. The fog server that achieves the highest value of this metric is dynamically elected as the leader for that round. This adaptive selection mechanism enhances fairness and ensures that the most effective server coordinates the final aggregation and blockchain submission. Further details of the mathematical formulation and selection process are provided in Section 3.3.

- (5)

- Final Aggregation by Leader: Non-leader fog servers forward their aggregated model weights to the elected leader, which then performs the final aggregation Equation (2) to produce the updated global model for the round.

- (6)

- IPFS-Based Off-Chain Model Storage: The system Serializes the aggregated weights as a flat, one-dimensional list of floating-point values and uploads them to the IPFS for decentralized storage. Through the ipfshttpclient interface, the leader receives a unique CID for the stored model. This CID ensures data integrity and enables the exact model version to be retrieved later.

- (7)

- Blockchain Authorization and Storage: The system authenticates fog servers through smart contract-based authorization before allowing them to submit model update hashes. Once the authorized leader completes aggregation, the hash is immutably recorded on the Ethereum blockchain, ensuring trust, accountability, and tamper-proof traceability across all learning rounds.

- (8)

- Global Model Distribution and Synchronization: After the leader records the model’s CID on the blockchain, each IoT device queries the contract to obtain the latest CID, then fetches the corresponding model weights directly from the IPFS, verifies the integrity via the CID, and reconstructs the model locally. This global anomaly detection model classifies network behavior into normal or specific attack categories (e.g., DDoS, ransomware, port scanning). During inference, IoT devices use the updated global model to identify anomalous traffic in real time. These synchronized weights serve as the starting point for the next training round.

Figure 5.

Workflow of Block-HFL. In practical applications, each IoT node may correspond to a wearable health sensor, a factory machine, or a smart city device that detects local anomalies. The numbered steps correspond to: (1) Local Training on IoT Devices, (2) Model Update Submission, (3) Local Aggregation on Fog Server, (4) Leader Election, (5) Final Aggregation by Leader, (6) IPFS-Based Off-Chain Model Storager, (7) Blockchain Authorization and Storage, and (8) Global Model Distribution and Synchronization.

3.3. Accuracy-Based Leader Election Mechanism

Traditional federated learning architectures rely on a single central server to aggregate model updates from all clients, which often leads to communication bottlenecks and higher latency. The proposed Block-HFL framework addresses these drawbacks by implementing a dynamic leader election mechanism among fog servers in each training round. During each round, all the fog servers independently aggregate their assigned client models and evaluate the resulting models on a shared validation dataset. The server with the highest aggregation accuracy is dynamically elected as the leader for that round, as described in Algorithm 1. This adaptive and round-based selection ensures that leadership is not fixed but, rather, determined by the real-time performance of each model, thereby promoting fairness, fault tolerance, and a balanced workload distribution while minimizing the reliance on a static central coordinator. The selection rule can be mathematically expressed as follows:

| Algorithm 1 Leader election and final aggregation in Block-HFL |

|

4. Experiments

This section presents the experimental methodology for the proposed model.

4.1. Experimental Setup

The experiments were carried out on Windows 10, equipped with an Intel Core i7 CPU (2.80 GHz) and 16 GB of RAM. Visual Studio Code (v1.106.2) served as the development environment, and all components were implemented in Python 3.10. Although a single machine was used, the distributed IoT–fog–blockchain architecture was fully emulated by running each entity as independent Python processes communicating over local gRPC channels. This setup enabled parallel execution of multiple federated learning clients and fog servers, and supported local blockchain transactions via Ganache. Global model weights were stored off-chain using an IPFS node accessed via the IPFS HTTP Client (v0.7.0). Model construction and training were performed using TensorFlow 2.19.0 and Keras 2.19.0. NumPy 2.2.5 was used for numerical computations, and Pandas 2.2.3 for data preprocessing, including loading and organizing the dataset shards. The gRPC framework (v1.71.0; Google LLC) facilitated remote procedure calls between IoT devices and fog servers. For blockchain integration, the Web3.py library (v7.11.1) [38] was used to deploy and interact with the smart contract implemented in Solidity. The smart contract recorded the CIDs of the global model stored on IPFS.

4.2. Dataset and Data Distribution

The Edge-IIoTset dataset [13] is a recent cybersecurity dataset designed explicitly for evaluating IDSs in IoT environments. This dataset was selected for its comprehensive representation of modern IIoT infrastructures that integrate emerging technologies. These technologies collectively emulate realistic IIoT communication scenarios, making Edge-IIoTset well-suited for training and evaluating machine learning-based IDS models, particularly within FL frameworks. This dataset has 61 features (selected) that are highly correlated from an original set of 1176 extracted features. Additional details about the dataset can be found in the Data Availability statement below.

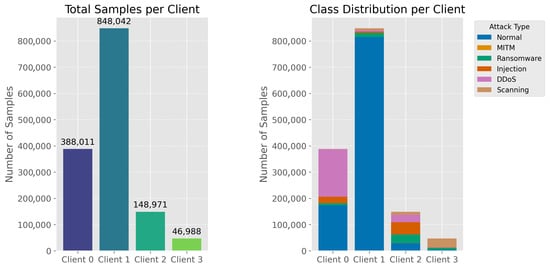

The dataset was generated from a diverse range of IoT devices, including temperature and humidity, ultrasonic, water level, pH, soil moisture, heart rate, and flame sensors. It contains normal traffic and 14 attack types categorized into five main groups: (1) Distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, (2) scanning attacks, (3) man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks, (4) injection attacks, and (5) malware attacks. In FL tasks, the data distribution needs to be non-IID, imbalanced, and representative of real-world scenarios. For experimental purposes, the Edge-IIoTset dataset was partitioned into several local datasets to facilitate training in accordance with the FL requirements.

Before distribution to clients, the dataset underwent a systematic data cleaning and pre-processing pipeline to ensure consistency and reduce noise. Duplicate entries and missing values, such as ‘NaN’ and ‘INF’, were removed. The attack type column was converted to the int32 data type, meeting TensorFlow’s label format requirements for training. Continuous features were normalized using Min–Max normalization, which scales all values into the interval [0, 1], thus ensuring uniform feature contributions during training.

After preparing the dataset, 10% of the samples were selected via stratified sampling to ensure equal representation across all classes. This subset was used exclusively as an IID evaluation shard: each fog server evaluated its locally aggregated model on this subset to determine the leader for the current round, and the selected leader subsequently used the same subset to evaluate the final global model before storing it on the blockchain.

The remaining 90% was divided among the clients. Each client received a unique data shard generated in a non-IID manner, reflecting the heterogeneity of typical IIoT networks. Table 4 displays the partitioning of the dataset into training and test sets. To assess the scalability and communication efficiency, the experiments used 4, 8, or 16 clients, with each number representing a different federated configuration.

Table 4.

Partitioning of Edge-IIoTset for training and testing.

The experiments were conducted on the Edge-IIoTset dataset, which is widely used in research on anomaly and intrusion detection in IoT and IIoT environments. It was divided among four federated clients in the first experiment. To simulate a non-IID environment, the Dirichlet distribution with a concentration parameter of was used to obtain unequal data splits (lower values create greater heterogeneity and more unbalanced data) [39]. This method was utilized as it produces diverse data distributions across clients, better reflecting real IoT network conditions. Figure 6 shows the data distributions for the four clients. The left chart shows the total number of samples, while the right chart shows the distribution by attack type. The datasets were highly imbalanced, as evidenced by Client 1 receiving the most samples (approximately 848,000) and Client 3 receiving the fewest (about 47,000). The class distributions also differed substantially among clients. Specifically, Clients 0 and 1 had a higher proportion of normal traffic than Clients 2 and 3, which had notably more scanning and injection attack samples. These direct disparities enabled a thorough assessment of the federated learning model’s robustness and generalization under highly heterogeneous data conditions. The dataset partitions remained fixed throughout all training rounds; no resampling or redistribution was performed, ensuring that each client preserved the same non-IID distribution across the entire experiment.

Figure 6.

Data distribution among four clients ().

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

The performance of the proposed Block-HFL framework was evaluated using several standard metrics in order to quantify both the effectiveness and computational efficiency of the developed models.

- True Positives (TPs): The number of attack instances that were correctly classified into their respective attack categories (e.g., DDoS, MITM, malware) by the model.

- True Negatives (TNs): The number of normal instances that were correctly classified as normal.

- False Positives (FPs): The number of normal instances that were incorrectly classified as an attack category.

- False Negatives (FNs): The number of attack instances that were incorrectly classified either as normal or as another wrong attack category.

- Accuracy is defined as the proportion of correctly classified instances and is calculated as follows:

- Precision measures the proportion of correctly identified attack instances among all the instances predicted as attacks, and is calculated as follows:

- Recall quantifies the proportion of actual attack instances that are correctly identified by the model:

- The F1-score gives the ratio of successfully classifying attacks to the total number of expected attack outcomes, which can be calculated as follows:

- The training time measures the duration required for each IoT client to complete local model training on its own dataset. It is computed aswhere and denote the timestamps recorded at the beginning and end of the local training process on each client device.

4.4. Model Configuration

Table 5 summarizes the main parameters and the CNN architecture used in the proposed federated anomaly detection model. A single CNN architecture was employed across all IoT devices. The chosen configuration—a lightweight 1D CNN with one convolutional layer (64 filters, kernel size of 3), followed by a Dense layer with 32 hidden nodes—was selected to balance detection performance with computational efficiency, making it suitable for resource-constrained IoT environments.

Table 5.

Model configuration parameters.

5. Results and Discussion

The experimental evaluation was conducted across three federated settings with 4, 8, and 16 clients to examine the behavior of the proposed Block-HFL framework at increasing scales and levels of heterogeneity. The 4-client configuration was used for illustrative analyses, including the visualization of non-IID data distributions, as it provides a clear and interpretable baseline. Additionally, the impacts of hierarchical aggregation, blockchain integration, and varying clients (4, 8, and 16) on scalability, efficiency, and security are examined to demonstrate the overall effectiveness of the proposed system.

5.1. Model Performance Analysis

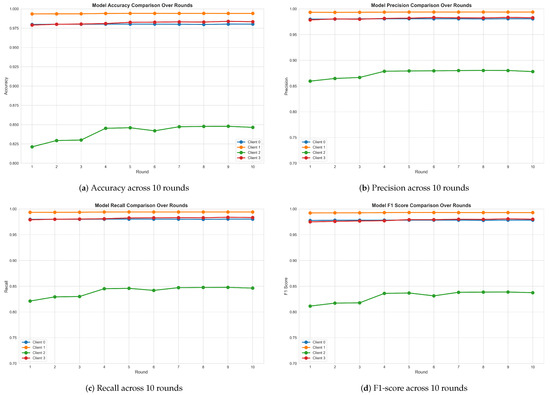

In this section, the performance of the individual local models trained by each client before global aggregation is evaluated. Each client operated on a distinct, non-IID subset of the Edge-IIoTset dataset, as described in Section 4.2.

Figure 7 illustrates the evolution of the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score across ten federated training rounds for each client in the four-client setup. Figure 7a shows that the accuracy increased substantially during the initial rounds and stabilized after the third round. Clients 0, 1, and 3 demonstrated consistently high accuracy, exceeding 97% throughout, whereas Client 2 exhibited slower convergence, with accuracy rising from 82% to approximately 85%. This disparity can be explained by the heterogeneity of the local datasets; specifically, that of Client 2 presented reduced size and limited diversity. The trends in the precision, recall, and F1-score shown in Figure 7b–d mirror those observed for the accuracy. Clients 0, 1, and 3 consistently achieved precision, recall, and F1-score values above 97%, indicating strong and stable classification performance. Conversely, Client 2’s scores—while lower—demonstrated gradual improvement over the rounds. These findings underscore the substantial effect of data heterogeneity, thereby reaffirming the pivotal role of data distribution in determining performance and convergence behaviors in federated learning scenarios.

Figure 7.

Local model performance across ten rounds for all clients.

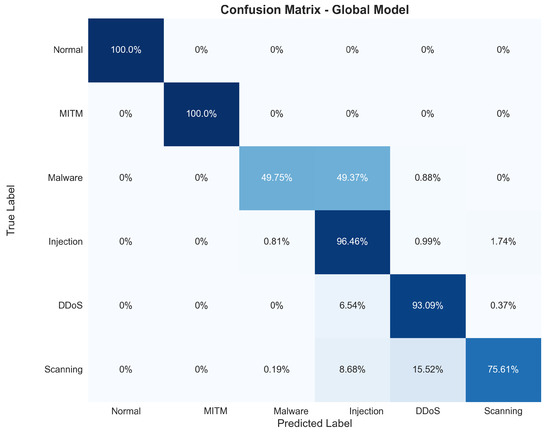

Figure 8 shows the global model’s confusion matrix under the four-client setup after the 10th round and details how each traffic type was classified. The model detected normal and MITM traffic perfectly, demonstrating a strong ability to separate benign from MITM attacks with 100% accuracy. It identified malware correctly 49.75% of the time, indicating that some malicious patterns overlap with other attacks. The injection category had a 96.46% accuracy, showing strong results. DDoS traffic was recognized with an accuracy of 93.03% and scanning attacks with an accuracy of 75.61%, highlighting the model’s robustness in distinguishing most attack types despite some confusion between overlapping feature spaces.

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix of the global model. The color intensity reflects the classification proportion in each cell: darker blue indicates higher values, while lighter shades represent lower values.

5.2. Block-HFL Evaluation for Different Numbers of Clients

We deployed our model for FL experiments using different numbers of clients; namely, , , and . The non-IID data distributions for and used for the experiments are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S1–S2), and detailed confusion matrices for the global models are presented in Figures S3–S4. Table 6 compares the accuracy outcomes of the global models, the best clients, and the worst clients after the first and tenth FL rounds. At the beginning of training (first round), the 4-client configuration achieved a global accuracy of 92.08%. This increased to 95.64% by the tenth round, indicating steady convergence. Similarly, that of the 8-client setup improved from 93.44% to 94.96%, while the 16-client setup improved from 94.81% to 95.92%, representing the highest overall global accuracy among all the configurations. In terms of the local performance, the best local accuracies (B) remained consistently high across all sets, ranging from 98.93% to 99.34%. In contrast, the worst local accuracies (W) exhibited noticeable variation. The lowest value, 82.12%, was observed for the 4-client setup in the first round. Overall, the 16-client configuration in the tenth round achieved the highest accuracy levels across all metrics. These results collectively confirm that both the global performance and learning consistency are maintained while increasing the number of clients.

Table 6.

Global model accuracy across clients and rounds.

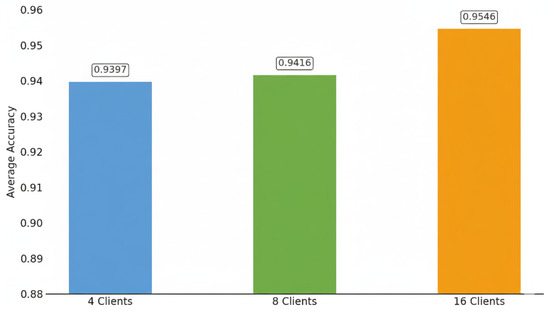

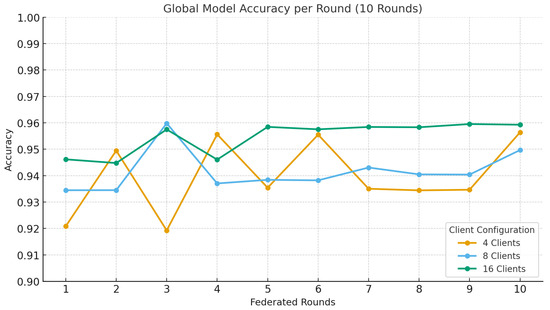

Figure 9 presents the average global model accuracy obtained under different client configurations. Figure 10 shows the accuracy progression across ten federated rounds for each setting. The results demonstrate that the proposed Block-HFL framework maintained stable convergence and a consistent performance as the number of clients increased. The average global accuracy remained high, ranging from 93.97% with 4 clients to 94.16% with 8 clients and 95.46% with 16 clients. This convergence indicates that hierarchical aggregation enables the model to preserve effectiveness and generalization, even as more clients participate. The consistent performance across configurations validates the scalability and robustness of the proposed Block-HFL architecture under non-IID data conditions.

Figure 9.

Average global model accuracy across different client sets.

Figure 10.

Global model accuracy progression over ten federated rounds for different client sets.

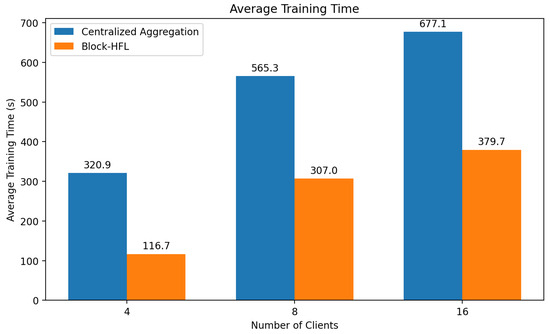

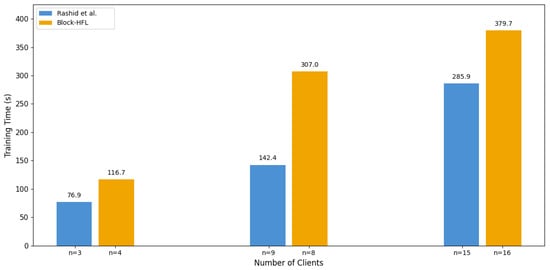

Figure 11 compares the average training time for a centralized aggregation approach and the proposed Block-HFL framework across 4, 8, and 16 clients over 10 training rounds. The reported values indicate the average training time calculated across ten federated training rounds for each client configuration. The results clearly demonstrate the efficiency of Block-HFL in terms of computational latency. While centralized aggregation exhibited a steep increase in training time as the number of clients grew (from 320.9 s to 677.1 s), Block-HFL also showed an upward trend (from 116.7 s to 379.7 s). However, the increase in Block-HFL was substantially smaller in magnitude, reflecting its greater scaling efficiency. This reduction highlights the robustness of Block-HFL in distributed environments, where hierarchical aggregation at the fog layer mitigates the computational and communication burden on a single central server. Decentralized coordination and parallel local processing significantly reduce the latency, enabling scalable and real-time anomaly detection in industrial IoT scenarios.

Figure 11.

Average training time across different client sets over 10 rounds.

5.3. Blockchain Integration

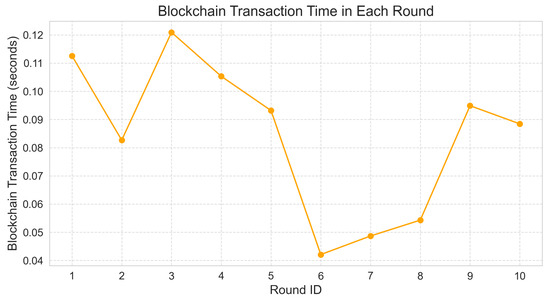

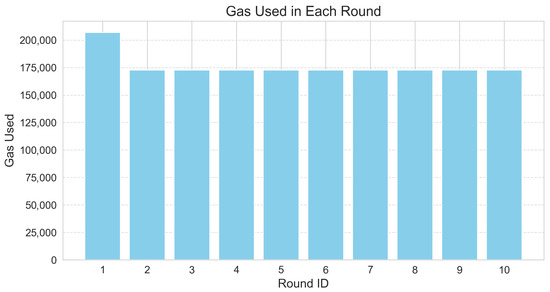

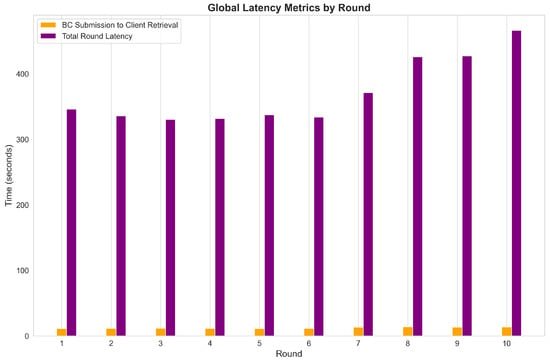

The integration of a blockchain into the Block-HFL framework was evaluated to determine its transaction time, gas consumption, and overall system latency. Blockchain transaction time was measured as the duration between submitting the global model transaction and receiving its mined receipt, while gas consumption was returned by Ganache. System latency was computed as the end-to-end delay from initiating the global model to the successful retrieval of the corresponding CID from the blockchain. Figure 12 presents the blockchain transaction time across ten federated rounds, which ranged from 0.04 to 0.12 s. These low values indicate that recording the global model on-chain introduces a negligible delay to the training process. In this framework, the global model is stored off-chain using IPFS, while only the corresponding IPFS hash is recorded on the blockchain. This approach enables secure and verifiable model tracking without incurring significant on-chain storage requirements. Similarly, Figure 13 displays the gas usage per round, which remained nearly constant at approximately 175,000 to 205,000 gas units, indicating the cost stability of blockchain operations. This stability resulted from each transaction executing the same smart contract function with a fixed computational complexity.

Figure 12.

Blockchain transaction time per round.

Figure 13.

Gas used per round.

Figure 14 compares the total round latency to that associated with the blockchain submission through to client retrieval, indicating that the blockchain operations account for less than 3% of the total communication time. These results demonstrate that the blockchain layer provides secure, transparent, and lightweight global model storage with minimal performance overhead, thus supporting the practicality and efficiency of the proposed Block-HFL system.

Figure 14.

Total latency and blockchain submission to client retrieval latency.

5.4. Comparison with Related Works

Table 7 provides a comparative overview of the proposed model and related FL-based IDS approaches. The comparison encompasses multiple dimensions, including the publication year, dataset, data distribution (non-IID), classifier architecture, blockchain used, number of participating clients, and each study’s primary contributions. The number of clients varied across different methods. In the proposed Block-HFL system, client counts of n = 4, 8, and 16 were selected to achieve balanced hierarchical aggregation. This configuration ensured that the clients were evenly distributed among the fog servers, thereby supporting synchronized updates and equitable leader election.

Table 7.

Comparison of FL-based anomaly detection approaches.

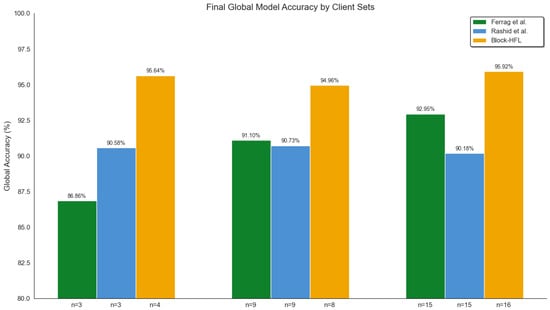

Figure 15 shows the final global model accuracy for three sets of federated clients, comparing the Block-HFL model with the results of Ferrag et al. [13] and Rashid et al. [23]. The Block-HFL framework consistently reached a higher global accuracy in all cases, showing better scalability and stability when the data are not evenly distributed. Ferrag et al. reported accuracies of 86.86%, 91.10%, and 92.95% with 3, 9, and 15 clients, respectively, while Rashid et al. achieved 90.58%, 90.73%, and 90.18% with the same numbers of clients. In comparison, the Block-HFL model achieved 95.64%, 94.96%, and 95.92% with 4, 8, and 16 clients, respectively, indicating the highest stability and accuracy. These results suggest that integrating hierarchical aggregation with a blockchain improves both performance and fairness.

Figure 15.

Final global model accuracy comparison across client sets [13,23].

Figure 16 compares the average training time of the proposed Block-HFL framework with that achieved by Rashid et al. [23] across three client sets. The study by Ferrag et al. was excluded from this comparison because their performance metrics did not report training time, which precluded a direct quantitative comparison. The results indicate that the training time increased with the number of participating clients in both approaches due to the larger volume of local updates per round. The proposed Block-HFL framework had a slightly higher training time. This was primarily due to the larger and more comprehensive dataset used in this study. Rashid et al. used a smaller subset of the Edge-IIoTset, with about 0.17 million samples. In contrast, the proposed model operated on a larger part of the Edge-IIoTset dataset, which contains roughly 1.59 million samples. This greater data volume increased the amount processed in each federated round, which, in turn, prolonged the local training duration per client. However, using a larger dataset enhanced the model’s generalization and ensured that the resulting global model better represented diverse IoT traffic behaviors.

Figure 16.

Training time (s) vs. number of clients [23].

6. Conclusions and Future Work

The Block-HFL framework was proposed for anomaly detection in IoT environments. This approach combines hierarchical aggregation with blockchain-based authentication and storage to provide high detection accuracy and enhanced scalability, while using an accuracy-based leader election mechanism to ensure reliable model updates. Experimental evaluation on the Edge-IIoTset dataset demonstrated the robust performance of the model under non-IID data conditions; it maintained a global accuracy above 94% while significantly reducing the communication overhead and latency. The integration of a blockchain ensures the security, transparency, and resistance to tampering of the final global model with only a minor increase in the computational overhead.

Although this study demonstrated the proposed framework’s effectiveness, it was conducted in a simulated environment using a private Ethereum network, which may differ from real-world blockchain deployments. Future research should focus on implementing the framework in actual IoT infrastructure and addressing practical challenges such as the computational load, memory limitations, and battery consumption. Integrating advanced privacy-preserving techniques, such as differential privacy or homomorphic encryption, could further enhance data confidentiality. Expanding the model to incorporate diverse deep learning architectures, such as RNNs or transformers, and evaluating the performance across a broader range of IoT datasets are also recommended for future work.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152413037/s1. Figure S1. Federated Learning Data Distribution—8 Clients. Visualization of non-IID distribution of Edge-IIoTset samples among eight clients. Figure S2. Federated Learning Data Distribution—16 Clients. Dataset distribution across sixteen clients shows increased heterogeneity and imbalance. Figure S3. Confusion Matrix of the Global Model—8 Clients. Classification performance of the Block-HFL model with eight clients. Figure S4. Confusion Matrix of the Global Model—16 Clients. Classification performance of the Block-HFL model with sixteen clients under highly fragmented data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S.A., S.A. and M.K.; methodology, H.S.A.; software, H.S.A.; validation, H.S.A., S.A. and M.K.; formal analysis, H.S.A.; investigation, H.S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.A.; writing—review and editing, H.S.A., S.A. and M.K.; supervision, S.A. and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by a grant No. CRPG-25-2014 under the Cybersecurity Research and Innovation Pioneers Grants Initiative, provided by the National Cybersecurity Authority (NCA) in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is publicly available as part of the Edge-IIoTset benchmark and can be accessed at: https://www.kaggle.com/mohamedamineferrag/edgeiiotset-cyber-security-dataset-of-iot-iiot (accessed on 15 January 2022). The source code used in this study is available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Block-HFL | Blockchain-Enabled Hierarchical Federated Learning |

| CID | Content Identifier |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CSV | Comma-Separated Value |

| DDoS | Distributed Denial of Service |

| DNN | Deep Neural Network |

| FL | Federated Learning |

| FedAvg | Federated Averaging |

| gRPC | Google Remote Procedure Call |

| HFL | Hierarchical Federated Learning |

| IDS | Intrusion Detection System |

| IID | Independent and Identically Distributed |

| IIoT | Industrial Internet of Things |

| IPFS | InterPlanetary File System |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| MITM | Man-in-the-Middle |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| RPC | Remote Procedure Call |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

References

- Sadhu, P.K.; Yanambaka, V.P.; Abdelgawad, A. Internet of Things: Security and solutions survey. Sensors 2022, 22, 7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Statistics: Number of IoT Devices Worldwide. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Moustafa, N.; Hawash, H. Privacy-preserved cyberattack detection in industrial edge of things (IEoT): A blockchain-orchestrated federated learning approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 7920–7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Li, Q.; Yousafzai, A. Blockchain and federated learning-based intrusion detection approaches for edge-enabled industrial IoT networks: A survey. Ad Hoc Netw. 2024, 152, 103320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Sarkar, S.; Aouedi, O.; Yenduri, G.; Piamrat, K.; Alazab, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Maddikunta, P.K.R.; Gadekallu, T.R. Federated learning for intrusion detection system: Concepts, challenges and future directions. Comput. Commun. 2022, 195, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, P.; Chiaro, D.; Guzzo, A.; Ianni, M.; Fortino, G.; Piccialli, F. Model aggregation techniques in federated learning: A comprehensive survey. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 150, 272–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Li, C.; Li, Q. A Survey of Fog Computing: Concepts, Applications and Issues. In Proceedings of the 2015 Workshop on Mobile Big Data, Hangzhou, China, 21 June 2015; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Lyu, F.; Ren, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y. SHARE: Shaping data distribution at edge for communication-efficient hierarchical federated learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 41st International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Washington, DC, USA, 7–10 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, T.Q.; Nguyen, D.N.; Hoang, D.T.; Vu, P.T.; Dutkiewicz, E. In-network computation for large-scale federated learning over wireless edge networks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.10903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadhoun, R.; Salah, K.; Kadadha, M.; Alhemeiri, M.; Alshehhi, M. A user authentication scheme of IoT devices using blockchain-enabled fog nodes. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/ACS 15th International Conference on Computer Systems and Applications (AICCSA), Aqaba, Jordan, 28 October–1 November 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mothukuri, V.; Pouriyeh, S.; Parizi, R.M.; Dehghantanha, A.; Choo, K.-K.R. FabricFL: Blockchain-in-the-loop federated learning for trusted decentralized systems. IEEE Syst. J. 2022, 16, 3711–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuveneers, D.; Rimmer, V.; Tsingenopoulos, I.; Spooren, J.; Joosen, W.; Ilie-Zudor, E. Chained anomaly detection models for federated learning: An intrusion detection case study. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrag, M.A.; Friha, O.; Hamouda, D.; Maglaras, L.; Janicke, H. Edge-IIoTset: A New Comprehensive Realistic Cyber Security Dataset of IoT and IIoT Applications for Centralized and Federated Learning. TechRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, J.R. Induction of decision trees. Mach. Learn. 1986, 1, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baucas, M.J.; Spachos, P.; Plataniotis, K.N. Federated learning and blockchain-enabled fog-IoT platform for wearables in predictive healthcare. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.04511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, S.M.; Buyya, R. FedSDM: Federated learning based smart decision making module for ECG data in IoT integrated edge–fog–cloud computing environments. Internet Things 2023, 22, 100784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.E.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Reducing the dimensionality of data with neural networks. Science 2006, 313, 504–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyomukiza, T.; Sharara, H.S.E. Unsupervised anomalies detection in IIoT edge devices’ networks using federated learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.12175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.M.; Khan, S.U.; Eusufzai, F.; Redwan, M.A.; Sabuj, S.R.; Elsharief, M. A federated learning-based approach for improving intrusion detection in industrial Internet of Things networks. Network 2023, 3, 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Rasul, K.; Vollgraf, R. Fashion-MNIST: A Novel Image Dataset for Benchmarking Machine Learning Algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.07747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A. Learning Multiple Layers of Features from Tiny Images; Technical Report; University of Toronto: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, H. BlockLearning: A modular framework for blockchain-based federated learning. In Blockchain and Trustworthy Systems; Springer: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Buterin, V. Ethereum: A Next-Generation Smart Contract and Decentralized Application Platform; White Paper. 2014. Available online: https://ethereum.org/en/whitepaper/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; Brevdo, E.; Chen, Z.; Citro, C.; Corrado, G.S.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; et al. TensorFlow: Large-Scale Machine Learning on Heterogeneous Systems. 2015. Available online: https://www.tensorflow.org/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, S.; Dai, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, H. An Overview of Blockchain Technology: Architecture, Consensus, and Future Trends. Proc. IEEE 2018, 6, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.K.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Q.; Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Paik, H.-Y.; Zhu, L. Toward trustworthy AI: Blockchain-based architecture design for accountability and fairness of federated learning systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 3276–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, S.M.; Buyya, R. Leveraging blockchain and federated learning in edge–fog–cloud computing environments for intelligent decision-making with ECG data in IoT. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2025, 233, 104037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, K.; Maharjan, S.; Zhang, Y. Communication-efficient federated learning and permissioned blockchain for digital twin edge networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 2276–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androulaki, E.; Barger, A.; Bortnikov, V.; Cachin, C.; Christidis, K.; De Caro, A.; Enyeart, D.; Ferris, C.; Laventman, G.; Manevich, Y.; et al. Hyperledger Fabric: A Distributed Operating System for Permissioned Blockchains. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth EuroSys Conference, Porto, Portugal, 23–26 April 2018; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, X.; Shao, X.; Pu, G.; Zhang, Y. Blockchain and federated learning for collaborative intrusion detection in vehicular edge computing. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 6073–6084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- gRPC Authors. An Introduction to Key gRPC Concepts, with an Overview of gRPC Architecture and RPC Life Cycle. Available online: https://grpc.io/docs/what-is-grpc/core-concepts/ (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Benet, J. IPFS—Content Addressed, Versioned, P2P File System (DRAFT 3). arXiv 2014, arXiv:1407.3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmahfoud, E.; El Hajla, S.; Maleh, Y.; Mounir, S.; Ouazzane, K. Label flipping attacks in hierarchical federated learning for intrusion detection in IoT. Inf. Secur. J. Glob. Perspect. 2025, 34, 310–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethereum Foundation. Ethereum/Web3.py: A Python Interface for Interacting with the Ethereum Blockchain and Ecosystem. Available online: https://web3py.readthedocs.io/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Hsu, T.-M.H.; Qi, H.; Brown, M. Measuring the Effects of Non-Identical Data Distribution for Federated Visual Classification. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1909.06335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).