Abstract

This paper presents a new approach to the dimensional synthesis of a robotic limb mechanism for a wheel-legged robot. The proposed kinematic structure enables independent control of wheel motions relative to the robot platform, allowing each drive to perform a distinct movement. The selection of the mechanism’s common dimensions simplifies platform levelling to a single-drive actuation. The hybrid limb design, which combines features of driving and walking systems, enhances platform stability on uneven terrain and is suitable for rescue, exploration, and inspection robots. The synthesis method defines the desired trajectory of the wheel centre and applies a genetic algorithm to determine mechanism dimensions that reproduce this motion. The stochastic optimisation process yields multiple feasible solutions, enabling the introduction of additional design criteria for optimal configuration selection. Analytical kinematic relations were developed for workspace and trajectory evaluation, solving both direct and inverse kinematic problems. The results confirm the effectiveness of evolutionary optimisation in synthesising complex kinematic mechanisms. The proposed approach can be adapted to other mobile robot structures. Future work will address dynamic modelling, adaptive control for real-time platform levelling, and comparative studies with other synthesis methods.

1. Introduction

Wheel–legged robots are hybrid mobile robots that combine the features of wheeled and walking robotic platforms [1]. They were created by combining walking robots, in which the feet were replaced with drive wheels. Thanks to the ability to choose the appropriate mode of locomotion, these robots can move more effectively in diverse terrains and environments.

The need to use mobile robots stems from the growing demand for process automation in a rapidly changing industrial and service environment. Mobile robots, thanks to their ability to move independently and adapt to their surroundings, enable increased operational efficiency, reduced labour costs and improved employee safety by eliminating the need to perform dangerous or monotonous tasks [2]. Furthermore, their use contributes to improving the precision and repeatability of technological processes, which is crucial in the context of Industry 4.0 [3]. With the development of artificial intelligence and vision systems, mobile robots are becoming increasingly autonomous, opening up new opportunities for their use in logistics, agriculture, medicine and transport [4].

The literature contains many examples of wheel–legged mobile robots with different numbers of limbs developed in many research centres. An example of a bipedal hybrid robot is Handle [5]. It is a balancing robot designed to carry loads in warehouses. To maintain stability on two wheels, the Handle is equipped with a movable counterweight system that compensates for the variable load on the limbs when carrying loads. Other examples of similar robots include Ascento [6] and WLR II [7]. The literature also contains examples of quadruped robots such as ANYmal on Wheels [8], which was based on a four-legged robot [9] similar to Spot [10]. ANYmal was equipped with wheels, which expanded its mobility. Another example is Centauro [11]. It is a humanoid robot connected to a platform that enables walking and driving. It was created to perform various activities in environments inaccessible to humans.

The Atlete robot [12] is a hexapod robotic platform developed by NASA for use in building a space base during future missions to the Moon.

The main design challenge is to develop the robot’s limb mechanism. The wheel guidance mechanism in the robot is a complex kinematic system that must provide both the movements necessary for walking and driving [13]. To perform gait, the limb mechanism must provide at least two movements: lifting and extending the wheel. Rolling and turning movements of the wheel are necessary for driving. The robots presented have a variety of limb structures with different degrees of mobility.

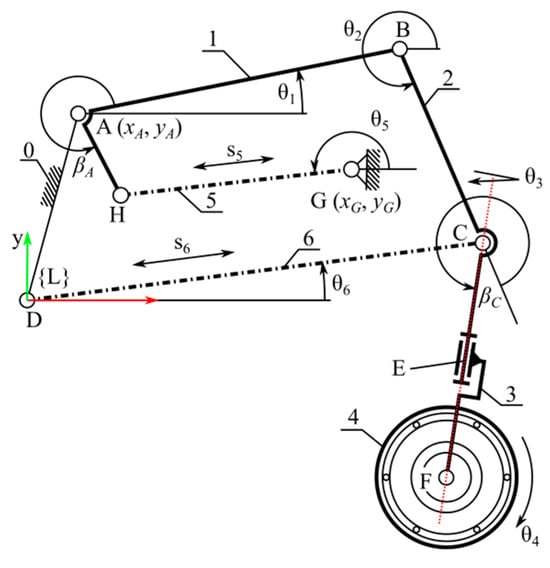

As part of research conducted at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering of the Wrocław University of Science and Technology, prototypes of mobile robots with a wheel–legged structure were developed and tested [14]. The research covered issues related to the design methodology, kinematics, dynamics and control of this type of construction [15]. The theoretical analyses and laboratory experiments resulted in new design solutions and control algorithms, which constitute a significant contribution to the development of knowledge about mobile robotic systems and their practical applications in modern industries [16]. One of the research outcomes was the development of a novel, innovative wheel guidance mechanism for a mobile robot, enabling both driving and walking (Figure 1).

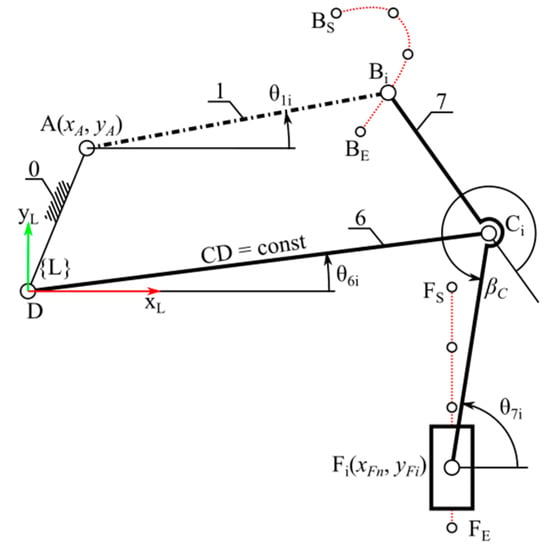

Figure 1.

Kinematic scheme of designed hybrid wheel–legged mobile robot.

This work aims to develop a method for dimensional synthesis (dimension selection) of a limb mechanism that ensures proper wheel movements.

2. Materials and Methods

At Wrocław University of Science and Technology, as part of a project involving the construction of a four-limbed robot, a new wheel guidance limb for wheel–legged robots has been developed [17] (Figure 1). The mechanism has four degrees of freedom, which necessitates the use of four kinematic excitations (drives).

The primary advantage of the presented mechanism is that limb movements are performed by individual drives independently of one another. Two drives are designed for driving, and the other two for gait movements. Angular excitation θ3 performs the steering manoeuvre, and θ4 is responsible for the rolling of the wheel. The s5 linear drive is responsible for the limb lifting movement. It forces the centre of the wheel to move along vertical trajectories. The s6 linear drive (with the s5 drive locked) is responsible for wheel extension, which is the horizontal movement of the wheel necessary to step over an obstacle. The combination of the movements of both drives enables the achievement of more complex wheel centre trajectories.

A wide range of strategies used in dimensional synthesis have already been explored [18,19,20]. The developed dimensional synthesis method focuses on determining the common dimensions of the limb to perform the intended walking and riding movements, i.e., the appropriate guidance of the centre of the wheel—point F. Two tasks of the wheel suspension mechanism have been identified:

- Guiding point F in the vertical axis to compensate for uneven terrain during driving to level robot platform;

- Moving the wheel horizontally during walking.

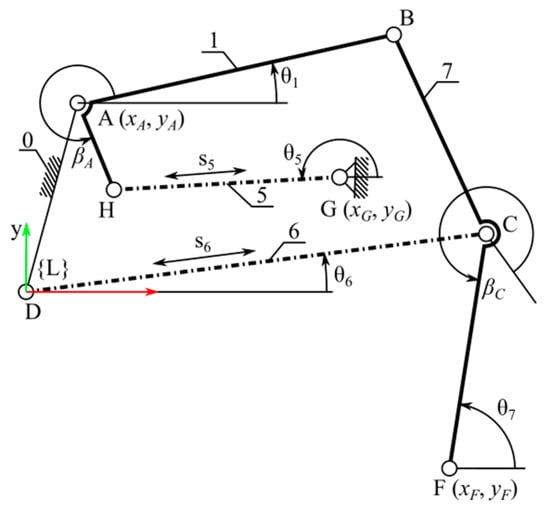

It was assumed that the axes of the wheel steering drive θ3 and the driving drive θ4 intersect at point F. It was also determined that the steering axis θ3 is aligned along the CF segment (Figure 1 and Figure 2). As a result of this assumption, the movements of these drives do not affect the displacement of the wheel centre F relative to the limb coordinate system {L}. Therefore, in the subsequent stages of synthesis, the θ3 and θ4 drives were omitted, as they do not affect the movement of the wheel centre. After replacing members 2, 3 and 4 with a single replacement link 7 (Figure 1 and Figure 2), a two-degree-of-freedom (2 DoF) planar mechanism was obtained (Figure 2).

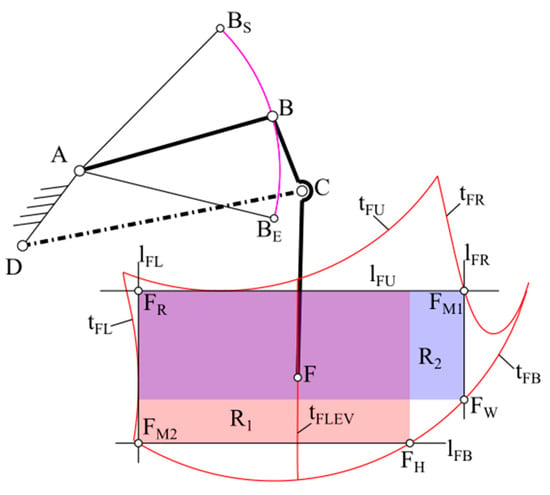

Figure 2.

Scheme of simplified limb mechanism without steering and wheel drive.

This work aims to develop a method for dimensional synthesis of a limb that allows the dimensions of the mechanism to be selected to ensure the lifting movement of the wheel (point F) along a trajectory similar to a vertical section with the walking drive s6 locked. The innovation of the wheel suspension used in the robot lies in the fact that by selecting the appropriate dimensions of the system components, vertical wheel movement can be achieved using only one drive, which significantly simplifies the robot control system in the case of levelling the platform while driving. The procedure for selecting the dimensions of the limb mechanism for the adopted synthesis objective requires determining the lengths of members AB, BC, AH, CF, angles βA, βC, the position of support points A(xA, yA) of member 1 and G(xG, yG) of member 5 attachment, and the ranges of motion of the s5 wheel lift drive HGMIN, HGMAX and the s6 wheel extension drive CDMIN, CDMAX. Assuming that both linear drives s5 and s6 will be identical, i.e., their ranges of motion will also be equal to sMIN to sMAX. Therefore, 10 geometric parameters of the mechanism need to be determined.

The following assumptions were made for the synthesis of the mechanism:

- Rectilinear trajectory of the centre of wheel F (with the s6 extension drive locked in the fixed position CDLEV);

- The workspace of the movement of the centre of wheel F of the limb mechanism will have a height hs and a width ls greater than the width and height of two standard stair sizes;

- The trajectory of the centre of wheel F will ensure uniform vertical guidance of the wheel, depending on the deflection of the levelling drive s5.

Fundamentals of Dimensional Synthesis of Basic Limb Dimensions

The procedure for dimensional synthesis of the basic dimensions of the limb is divided into three main stages. The first stage involves determining the limb parameters required to achieve a vertical trajectory of the wheel centre F, with the wheel extension drive locked at s6 = const. Movement along such a trajectory will be used when driving off-road to lift the wheel and compensate for uneven terrain. In the next stage of synthesis, by activating the wheel extension drive s6, the boundary of the workspace of the mechanism was determined. Its dimensions were then analysed. In the final stage of synthesis, the parameters for mounting the levelling drive s5 were selected and the vertical guidance of the wheel was evaluated.

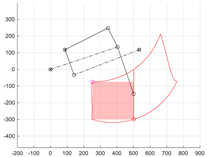

In the first stage, the linear parameters AB, BC, and CF, the angular parameter βC, and the position of point A (xA, yA) were selected. For this purpose, a constant length of the stepping actuator s6 = CD = CDLEV was assumed, at which the trajectory of point F is to be vertical. The synthesis was performed with a fixed vertical movement of the centre of circle F. To achieve a one-degree-of-freedom (1 DoF) mechanism in this step, it was assumed that link AB has a variable length. The synthesis aimed to obtain a constant length of segment AB with the assumed movement of the centre of circle F (Figure 3).

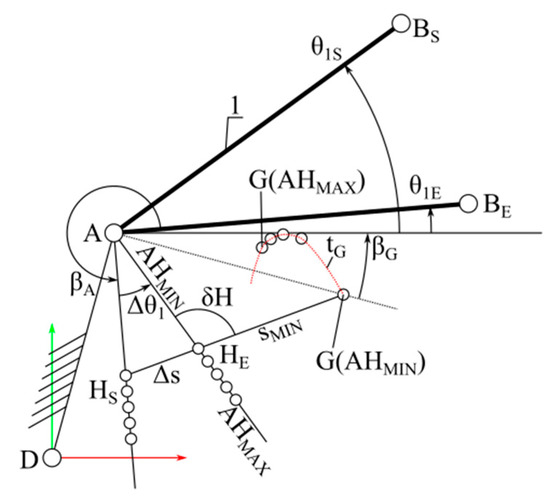

Figure 3.

Desired wheel lift trajectory (point F), with fixed stroke of s6 drive assumed.

A vertical section of the centre of the circle F was established between two given points, the starting point FS (xFn, yFS) and the end point FE (xFn, yFE). The assumed segment was divided into n-evenly spaced points Fi (xFn, yFi) for i = 1, …, n. For each position point Fi, the corresponding positions of point Ci were determined at the intersection of circles O1 (with centre at D and radius CD) and O2 (with centre at Fi and radius CF). The formula gives the position of point Ci:

where θ6i was determined based on the angles of the triangle FiDCi:

The parameter Δ12 is a discriminant of the equation that determines whether circles O1 and O2 intersect (Δ12 > 0), are tangent to each other (Δ12 = 0) or have no points of intersection (Δ12 < 0). Subsequently, the orientation θ7i of link 7 is determined based on point Ci:

The designated angular positions θ7i determine CF and, with the selected parameters BC and βC, determine the set of points Bi (trace tB) on the trajectory of point B. The formula gives the position of point Bi:

By assuming the position of a fixed point A (xA, yA), it is possible to determine the set of lengths ABi corresponding to the successive positions of points Bi. The optimisation aimed to obtain a constant length AB for member 1. Therefore, the target function given by the formula was minimised:

where ()—average value from the set of lengths ABi, rms—function determining the root mean square error.

The optimisation results in the ABCD four-bar mechanism (Figure 4), where link 1 is the driver, link 6 is the rocker and link 7 is the coupler part. The length AB of member 1 is assumed to be equal to (). With a constant length CD of the wheel extension drive, s6 = CDLEV, this mechanism moves the coupler point F along a trajectory similar to the assumed straight line, which is necessary to level the platform while driving. The literature on the optimisation of four-bar mechanism is extensive and continues to be developed [21,22].

Figure 4.

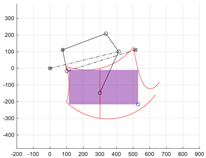

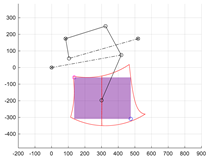

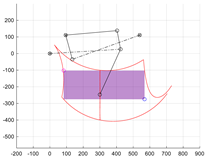

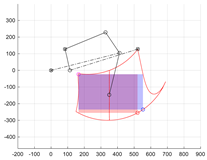

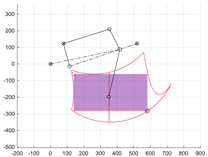

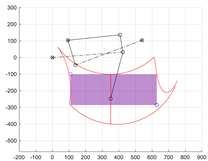

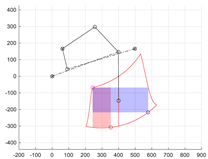

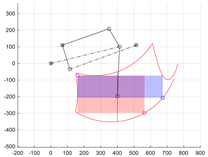

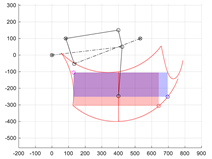

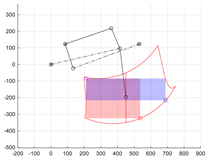

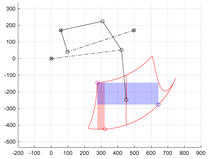

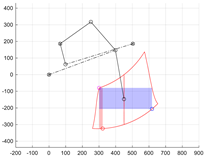

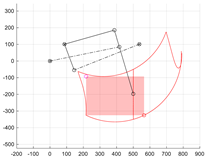

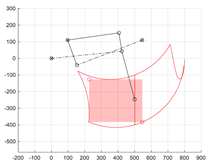

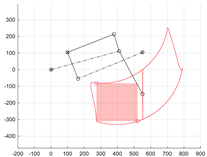

The workspace of the centre of wheel F of the robot limb mechanism.

The next step in the synthesis process was to evaluate the obtained solution. The first parameter examined was the rectilinearity of the trajectory of point F. Parameter θ1 was temporarily adopted as the wheel levelling drive, as the parameters of support point G and attachment point H of the wheel lifting drive s5 had not yet been determined. The angular range of movement of member AB was adopted based on the results obtained from the previous stage of synthesis, θ1 = <θ1S, θ1E>. The angle θ1S corresponds to the deflection of member 1 to point BS (initial position), and the angle θ1E corresponds to the position of member 1 so that point B coincides with point BE (final position). The working range of the θ1 drive was divided into m points. For each position θ1j, the position of point Bj was determined:

At specific points Bj (xBj, yBj) and D (xD, yD), the position of point Cj (xCj, yCj) was determined at the intersection of two circles O3 (with centre at Bj and radius BC) and O4 (with centre at D and radius CD):

where θ2j is the orientation of member 2 (BC) determined by the angles of triangle BCD:

Next, the position of point Fj was determined based on the position of point Cj and the parameters of member 2, i.e., the length CF and angle βC:

When the wheel extension drive is set to a fixed position s6 = CDLEV, the centre of wheel F moves along a trajectory similar to the specified vertical segment FSFE. The deviation of the position of points Fj in the horizontal xFj from the specified value xFn was determined. Based on the differences in the position of the centre of the wheel from the specified trajectory, the first coefficient COEFF1 was formulated, determining the quality of the solution:

Then, after activating the wheel extension drive s6, the size of the workspace of the centre of the wheel F of the limb mechanism was evaluated. The stroke range of the drive s6 was set between lengths CD = <sMIN, sMAX>. The positions of point F for the extreme positions of drives θ1 and s6 were determined. The upper limit of the workspace of the centre of wheel F was obtained at a constant position of point B in position BS (when θ1 = θ1S) and at an actuator extension of sMIN < s6 < sMAX. The working range of the actuator was divided into m points, thus determining the upper trace of point F—tFU consisting of m points. Similarly, the trace of the bottom limit of the workspace tFB was determined for the set position of point B in position BE (θ1 equal to θ1E) and with a change in the length of segment CD in the full range. Subsequently, the right boundary of the workspace tFR was created by a change in the angular position θ1 in the full range from θ1S to θ1E and a constant length CD of the extension actuator s6 = sMIN. The left boundary tFL corresponds to the trajectory of the centre of the wheel at a given drive s6 with a length CD equal to sMAX (Figure 4).

The resulting shape of the workspace should be assessed in terms of size (width and height). For assessment, it was assumed that a rectangle would be inscribed in the resulting area (Figure 4). The height and width of the rectangle will allow for an assessment of how high or wide obstacles, such as stairs, curbs or thresholds, the robot will be able to overcome. When controlling the limb in the task space (i.e., controlling the position of point F), the inscribed rectangle limits the movement capabilities of the mechanism to the ranges of the drives used. Additionally, it was assumed that the mechanism would not assume any dead or singular positions inside this rectangle.

The assessment procedure began with the definition of two tangent lines to the boundaries of the robot limb’s workspace. The first horizontal line lFU is tangent to the upper boundary of the tFU zone (Figure 4). The second vertical line lFL is tangent to the left boundary of the tFL working zone. The intersection of these tangents marks the first vertex FR of the rectangle being sought. Next, the intersection point FM1 of the horizontal tangent lFU with the right boundary of the workspace tFR is determined. The vertical line lFR drawn from this point FM1 intersects the lower boundary of the trace tFB, determining the lower right vertex FW of the rectangle R2 (FR, FW) marked in blue in Figure 4. Similarly, the intersection of the vertical tangent lFL with the lower boundary of the tFB zone marks the point FM2. The horizontal line lFB drawn from it intersects the boundary of the workspace, marking the vertex FH of the second rectangle R1 (FR, FH) inscribed in the area (marked in red in Figure 4). Rectangle R1 has a greater height. Rectangle R1 has a greater height, while rectangle R2 has a greater width. The height of rectangle R1 and the width of rectangle R2 are coefficients that can be used to assess the size of the working zone of the limb mechanism:

The final step of the synthesis was to select the parameters for mounting the s5 actuator responsible for wheel lifting movement. These are the coordinates of support point G (xG, yG) and the length AH and angle βA. It was assumed that the actuator is to rotate member 1 within the range (θ1S, θ1E) obtained in the first step of the synthesis. The s5 actuator in the minimum stroke position, GH equal to sMIN, is to force the orientation of member 1 equal to θ1S, and the maximally extended stroke of s5 actuator, GH equal to sMAX, is to correspond to the position of the wheel at the lower limit of the workspace when θ1 is equal to θ1E. Furthermore, to fully utilise the actuator’s capabilities, the angle δH of actuator s5 operation should be close to a right angle over the entire operating range of the actuator (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Limb dimensions determining the position of the s5 drive mounting.

For the specified length AH and angle βA, the starting point HS was obtained, corresponding to the position of member 1 in the initial orientation θ1S. The endpoint HE corresponds to the position of member 1 determined by the specified angle θ1E. At point HS, actuator s5 should be in its minimum stroke position sMIN, while at point HE, it should be in its maximum stroke position sMAX. The intersection of circles O5 (with centre at HS and radius sMIN) and O6 (with centre at HE and radius sMAX) determines the position of point G. The minimum length of lever AHMIN is that at which circles O5 and O6 are tangent to each other. Point G is then located on a straight line passing through points HS and HE, at a distance sMIN from point HS. The length AHMIN was determined based on the isosceles triangle HSAHE, where the base of the triangle HSHE has a stroke length s5 equal to Δs = sMAX − sMIN:

It was assumed that angle βA = 3/2 π and the trace tG of point G was determined by taking n values of length AH from the determined AHMIN to a certain fixed AHMAX. The greater the length of member AH, the less force the levelling actuator s5 will need to balance the loads of the wheel suspension system. However, the AH lever cannot be too long so that point H does not collide with the ground when the wheel is raised to its maximum height.

With the parameter βA = 3/2π set, the trace of point G is determined by the change in the length of member AH. Changing the parameter βA by a certain fixed angle ΔβA simultaneously rotates the trace tG relative to point A. The characteristic of angle δH therefore does not depend on angle βA, because changing this parameter simultaneously rotates triangle HSAHE and trace tG. Therefore, the length AH and the angle βA can be selected independently. For each adopted value of AHi, the characteristic of the angle δH of the levelling actuator s5 was determined. This characteristic is closest to the value 1/2 π when circles O5 and O6 are tangent to each other. It was therefore assumed that point G would be determined for the lever length AH = AHMIN. It was marked as point GREF (xGREF, yGREF).

When the angle βA changes, the segment AGREF rotates relative to point A. The value of angle βA was selected so that point G is located at the same height as point A (yG = yA). The designated point GREF was rotated relative to point A by angle βG, taking this rotation into account in the value of angle βA:

After this stage of synthesis, all the basic dimensions of the mobile robot limb mechanism were obtained. The last coefficient, which was necessary for evaluating the obtained solution (including s5 drive mount parameters), remained to be determined. In addition to the characteristic angle δH of actuator s5, the synthesis aimed to obtain a linear characteristic of the vertical displacement of point F, dependent on the stroke of actuator s5, for a fixed stroke of actuator s6 (for CD = CDLEV). Obtaining a linear characteristic yF(s5) with a slope coefficient mF will significantly simplify the control system of the robot platform levelling while driving over uneven terrain. The slope parameter mF has the following value:

In the next step of the synthesis, the influence of the stroke changes of the wheel lifting drive s5 on the vertical position yF of the wheel was determined. The previously determined Equation (3) defines the position of the centre of wheel F in relation to the value of angle θ1. At this stage, the influence of the change in length GH, i.e., the wheel lift drive s5, on the orientation of member 1 must be determined. For this purpose, point H was determined at the intersection of circle O7 (with centre at G and radius GH) and circle O8 (with centre at A and radius AH):

The inclination θ5 of the wheel lifting actuator, depending on its length GH, is determined based on the angles of the triangle GHA:

The position of point H expresses the orientation θ1:

Based on this relationship, the effect of the change in the length of the actuator on the lifting height of the wheel centre F was determined. The derivative of the vertical position of point F relative to the stroke of the wheel lifting drive s5 was calculated:

This derivative should have a constant value equal to mF, then the wheel lift characteristic will be linear. The derivative of the vertical position of the wheel centre relative to the orientation of member 1 was determined based on relation 3:

The derivative of angle θ2 with respect to angle θ1 was determined based on Equation (2):

Based on relations 5, 6 and 7, the derivative of orientation θ1 with respect to drive length s5 was determined:

The parameter allowing the linearity of the wheel level characteristic yF (s5, s6 = CDLEV) to be assessed is as follows:

The synthesis of the robot limb mechanism focused on determining the common dimensions of the robot limb mechanism for the proper execution of wheel guidance movements to accomplish the two main tasks set for the mobile robot: maintaining a constant platform orientation when driving on uneven terrain and stepping over obstacles that the robot cannot overcome by driving on wheels.

The developed COEFFi coefficients allow for the evaluation of the obtained solution. The first and fourth coefficients evaluate the platform levelling task. The second and third coefficients allow us to determine whether the robot will be able to manipulate its limbs to overcome obstacles such as thresholds, curbs, or steps.

3. Results

The dimensional synthesis procedure developed and presented in Section 2 was used to select the fundamental dimensions of a new innovative mobile robot limb. The robot being built is designed to navigate public buildings, where it may encounter obstacles such as thresholds and steps, and must be able to walk up and down typical stairs.

The preliminary design assumptions stipulate that obstacles will have a height hp of no more than 0.15 m. This corresponds to the height of a standard staircase. The height of the levelling trajectory is set to cover two such stairs, enabling the robot to walk. To obtain a sufficiently large working space, it was assumed that the Δs strokes of the lifting and walking actuators would be 0.15 m. Based on a review of available linear drive models, the minimum drive length was determined to be sMIN = 0.35 m. The maximum drive length sMAX = sMIN + Δs = 0.5 m. The length of the wheel extension drive s6, at which the wheel trajectory is to be straight, was assumed to be in the middle of the CDLEV = 0.425 m movement range.

The first optimisation objective in the synthesis procedure is to minimise the objective function F1TARGET given by relation (7). Five basic dimensions of the limb mechanism are sought: lengths BC, CF, angle βC, and coordinates of point A: xA and yA (Figure 3). The ranges of values for the sought parameters were adopted (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ranges of desired basic dimensions of the limb mechanism.

In the synthesis procedure, it was assumed that the common dimensions would take values from a fixed range with a fixed step. A genetic algorithm from Matlab’s “version 2024b” (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA www.mathworks.com) optimisation toolbox was used to solve the problem. The advantage of this algorithm is its ability to obtain a solution in a short amount of time. The disadvantage is the stochastic nature of the search. The effect of random searching of the parameter space may be that the algorithm gets stuck in a local minimum of the objective function. To avoid this, it was assumed that the algorithm would operate on integer variables. Linear functions were established that map the integer value of the variable to the real value of the length or angle of the parameter being searched for. The ranges of the variables were selected so that the lengths and coordinates of the points took values with an accuracy of 0.001 m, and the angle values with an accuracy of 0.1°. Limiting the search to integer variables accelerated the algorithm’s operation. In cases where a task requires greater accuracy in searching for dimensions, it is sufficient to modify the functions that map integer variables to the actual values of the robot limb mechanism’s dimensions.

It was assumed that the vertical levelling trajectory of point F would be determined by two points: the starting point FS and the end point FE. Three values of the height yFS of the starting point along the OY axis were assumed, equal to yFS ∈ <0 m, −0.05 m, −0.1 m>. The height of the specified trajectory of point F was set at 0.3 m, which determines the position of the final point FE. The position of the specified trajectory of point F along the OX axis was assumed to be in the range xFn ∈ <0.3 m; 0.55 m> with a step of 0.05 m. The specified section was divided into n = 10 points Fi, for which the positions of points Bi and the lengths of section ABi were determined.

For each given section of the trajectory of point F, a genetic algorithm was run to search for a solution. As a result, 18 geometric solutions for the mechanism of a wheeled walking robot limb were obtained (Table 2). In each case, sets of five sought parameters (BC, CF, βC, xA, yA) were obtained.

Table 2.

Robot limb mechanisms obtained for different positions of the given trajectory of wheel F.

The length of member AB was taken as the average value among the determined lengths ABi. The range of angular position changes θ1 of member 1 was taken as corresponding to points BS and BE (Figure 3). It was assumed that the movement of member 1 in the angular range θ1 ∈ <θ1S, θ1E> and the movement of the wheel extension actuator s6 in the range DC ∈ <sMIN, sMAX>.

For each mechanism, the values of the evaluation coefficients COEFF1, COEFF2 and COEFF3 were determined. Next, the support point of the wheel lifting actuator G (xG, yG) and the dimensions of the levers AH and βA were determined. The evaluation coefficient COEFF4 was determined for the selected dimensions. Table 3 shows the common dimensions of the robot limb mechanism obtained for the assumed different positions of the trajectory of point F. A mechanism was sought that would minimise the coefficients evaluating the trajectory of the wheel lifting movement, COEFF1 and COEFF4, while maximising the coefficients evaluating the size of the workspace, COEFF2 and COEFF3.

Table 3.

Common dimensions of the limb mechanisms obtained.

In Table 4, cases where individual coefficients have minimum or maximum values are marked with bold. The trajectory of the centre of circle F, the levelling movement of the platform, is best in the case of mechanism No. 10.

Table 4.

Values of COEFFi assessment coefficients as obtained solutions.

Assessing the workspace size is no longer straightforward. The mechanisms designated for the xFN parameter equal to 0.3 m and 0.35 m are characterised by rectangles R1 and R2 (Figure 4) of very similar sizes. However, the further the set trajectory of point F is from the centre of the system, the smaller the rectangle R2, and in some cases, it could not be determined. To assess the size of the workspace, the COEFF5 parameter was introduced, which is the product of the width of rectangle R1 (COEFF2) and the height of rectangle R2 (COEFF3). The values are presented in Table 4.

The best solution, according to the additional CEOFF5 coefficient, is mechanism No. 9. Limbs No. 10 and 15 have very similar COEFF5 values, which describe the size of the limb mechanism workspace. Mechanism No. 10 was therefore adopted as the dimensional synthesis solution for selecting the dimensions of the wheel–legged robot limb mechanism. It combines the characteristics of the desired wheel centre F trajectory for the platform levelling task with the appropriate workspace size necessary for walking.

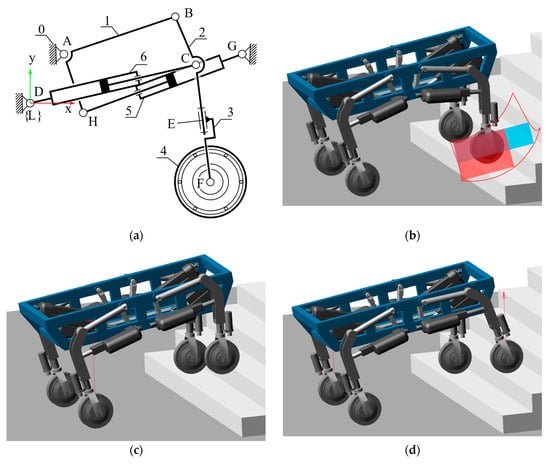

The results of the dimensional synthesis procedure presented above determined the dimensions of the new innovative limb of the wheel–legged robot. The selected solution is described in Table 3, row 10 (marked with bold), and presented in Figure 6a.

Figure 6.

(a) A kinematic scheme of the new limb mechanism with dimensions (Table 3, row 10) obtained based on the developed synthesis procedure, (b) model of wheel–legged mobile robot designed based on the obtained limb mechanism, (c) wheel lifting motion over the step, and (d) wheel extension motion over the step while overcoming the stairs.

Figure 6b shows a model of a wheel–legged mobile robot designed based on the proposed synthesis prepared in MSC Adams “version 2024.2” (Newport Beach, CA, USA). The workspace and the rectangles described against the background of the stairs show the possibility of moving the wheel along the profile of the stairs. Figure 6c shows the process of lifting the wheel along a vertical line, and Figure 6d shows the movement of the wheel over an obstacle along a horizontal line.

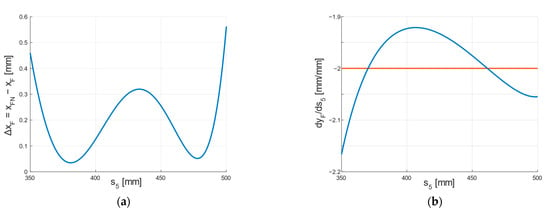

Figure 7 illustrates the characteristics of the wheel lifting trajectory obtained using the new limb mechanism solution. Figure 7a presents a curve describing the distance of the centre of the wheel F from the desired trajectory in the horizontal OX axis xFN – xF. Figure 7b shows the derivative dyF/ds5 of the vertical position yF of the wheel centre relative to the stroke of the wheel lifting actuator s5. The coefficient mF, given by Equation (4), is equal to −2 (ΔyF was set at 0.3 m, and the selected actuators have a stroke of Δs = 0.15 m).

Figure 7.

(a) The deviation of point F from the assumed straight trajectory used to level the robot platform, and (b) the derivative of vertical position yF depending on actuator extension s5 (blue), and it desired constant value (red) defined by Equation (4).

The quasi-linear trajectory of the centre of wheel F allows the platform to be levelled while driving, using only one drive (the wheel extension drive s6 is inactive). On the other hand, the constant characteristic dyF/ds5 allows us to assume that the vertical position of point F depends linearly on the extension of actuator s5. In Figure 7b, the obtained characteristic deviates from the constant, assumed value only at the beginning (when the wheel is raised to its maximum height). Furthermore, it deviates from the value dyF/ds5 = mF = −2 by only 0.1, which represents a 5% relative error. The proposed solution not only reduces the number of drives needed to maintain a constant platform orientation when driving on uneven terrain, but also significantly simplifies the drive control system by reducing kinematic equations to linear functions.

4. Conclusions

The current paper presents the design of a new mechanism for the limb of a wheel–legged robot. The innovative aspect of the solution lies in the selection of the kinematic structure of the limb mechanism, which allows for the independent execution of specific wheel movements relative to the robot platform. Each drive of the robot limb is responsible for performing different wheel movements. The presented selection of common mechanism dimensions has allowed for significant simplification of the platform levelling task, reducing it to the use of only one drive.

The developed mechanism can be utilised in mobile robots designed to operate in uneven terrain, where maintaining platform stability is crucial while driving. Thanks to its hybrid design, which combines the advantages of drive motors and walking motors, the designed limb can be used, for example, in rescue, exploration, or inspection robots.

In previous work [17], the authors focused on dividing the dimensional synthesis process into smaller steps so that a maximum of two parameters were selected at each stage. In this paper, the main parameters of the mechanism were optimised, and then coefficients COEFFi were presented to evaluate the solutions obtained. This allowed for the construction of an expert system where the selection of appropriate features allows for the choice of a solution.

The developed synthesis method involves determining the desired trajectory of the wheel’s centre and then, using a genetic algorithm, determining the dimensions of the mechanism that follows the given trajectory. The stochastic nature of genetic algorithms, combined with the varying positions of the given trajectory, allowed for the generation of a whole family of solutions. The synthesis results showed that for the adopted trajectory of point F, different mechanisms can be obtained by changing only the initial position of the trajectory. Such a variety of solutions allows the user to introduce additional criteria or design constraints, facilitating the selection of the optimal solution for the robot limb mechanism.

The optimisation task was formulated in such a way that the objective function F1TARGET is single-criterion. The use of a genetic algorithm allowed for the effective identification of a set of mechanism parameters that meet the assumed kinematic criteria. The results obtained confirm that the method is highly flexible and capable of finding many alternative solutions, which allows for further optimisation depending on design requirements.

It is worth noting that the accuracy of the solutions obtained and the calculation time depend on the selection of genetic algorithm parameters, such as population size, number of iterations, and mutation and crossover probabilities. However, the impact of these parameters on the results obtained was not the subject of this study. Additionally, the limb structure presented in this paper consists solely of rigid members. It does not contain any flexible elements, such as springs and dampers, typical of classic suspension mechanisms that can compensate for the impact of uneven terrain on platform inclination changes.

The synthesis method is based on the selection of COEFFi coefficients evaluating the obtained solutions. The paper presents the relevant kinematic relationships analytically. In the case of the working zone assessment, a solution to the simple kinematics task of the limb mechanism was determined, which consisted of determining the position of point F based on the extension of actuators s5 and s6. To assess the trajectory used to level the robot platform, the inverse kinematics task was solved.

The results obtained confirm the possibility of using evolutionary optimisation methods in the process of synthesising complex kinematic mechanisms. The developed approach is a universal tool that can be adapted to the design of other types of mobile robots with complex limb geometry.

Further research directions may include the development of a synthesis method that incorporates a dynamic limb model, allowing for consideration of the influence of inertial forces, the mass of limb mechanism components, and external loads. An important stage of future work will also involve the development and implementation of a control system that enables adaptive levelling of the robot platform in real time, as well as the verification of the designed mechanism through experimental tests using a prototype. In addition, it is planned to compare the genetic algorithm used with other optimisation methods, enabling us to assess their effectiveness and accuracy in the process of synthesising the robot limb mechanism.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DoF | Degree of Freedom |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| lA | Straight line named A |

| tA | Trace of a point based on a set of points on trajectory of point A obtained from kinematic analysis |

| O1(C, r) | Circle 1 with a centre point C, and a radius r |

| R1(A, B) | Rectangle 1, defined by to node points: upper left node A, and bottom right node B |

References

- Bałchanowski, J.; Gronowicz, A. Design and simulations of wheel-legged mobile robot. Acta Mech. Autom. 2012, 6, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Raygoza, L.E.; Gonzalez-Aguirre, J.A.; Felix-Herran, L.C.; Ramirez-Moreno, M.A.; Lozoya-Santos, J.d.J.; Tudon-Martinez, J.C. Autonomous Navigation System Test for Service Robots in Semi-Structured Environments. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Jia, H.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bi, G. Wheeled Permanent Magnet Climbing Robot for Weld Defect Detection on Hydraulic Steel Gates. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuhashi, H.; Kamata, H.; Itami, T. Self-Controlled Autonomous Mobility System with Adaptive Spatial and Stair Recognition Using CNNs. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introducing Handle. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-7xvqQeoA8c (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Klemm, V.; Morra, A.; Salzmann, C.; Tschopp, F.; Bodie, K.; Gulich, L.; Kung, N.; Mannhart, D.; Pfister, C.; Vierneisel, M.; et al. Ascento: A Two-Wheeled Jumping Robot. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 7515–7521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, S.; Feng, H.; Fu, Y. WLR-II, a Hose-less Hydraulic Wheel-legged Robot. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Macau, China, 3–8 November 2019; pp. 4339–4346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelonic, M.; Bellicoso, C.D.; de Viragh, Y.; Sako, D.; Tresoldi, F.D.; Jenelten, F.; Hutter, M. Keep Rollin’—Whole-Body Motion Control and Planning for Wheeled Quadrupedal Robots. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2019, 4, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fankhauser, P.; Hutter, M. ANYmal: A Unique Quadruped Robot Conquering Harsh Environments. Res. Features 2018, 126, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spot|Boston Dynamics. Available online: https://bostondynamics.com/products/spot/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Klamt, T.; Kamedula, M.; Karaoguz, H.; Kashiri, N.; Laurenzi, A.; Lenz, C.; Leonardis, D.; Hoffman, E.M.; Muratore, L.; Pavlichenko, D.; et al. Flexible Disaster Response of Tomorrow: Final Presentation and Evaluation of the CENTAURO System. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2019, 26, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, B.H. ATHLETE: A limbed vehicle for solar system exploration. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 3–10 March 2012; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bałchanowski, J. Mobile wheel-legged robot: Researching of suspension leveling system. In Proceedings of the Advances in Mechanisms Design, Proceedings of TMM 2012, Liberec, Czech Republic, 4–6 September 2012; Beran, J., Bílek, M., Hejnova, M., Zabka, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bałchanowski, J. Modelling and simulation studies on the mobile robot with self-leveling chassis. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2016, 54, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sperzyński, P.G. Modelling the Motion of a Wheel-Legged Robot on Uneven Terrain. PhD Thesis, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland, 2023. (In Polish). [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Sperzyński, P.G.; Bałchanowski, J.; Gronowicz, A. Simulation of motion of a mobile robot on uneven terrain. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2020, 58, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperzyński, P.; Bałchanowski, J. Dimensional synthesis of suspension system of wheel-legged mobile robot. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2025, 63, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buśkiewicz, J. The optimum distance function method and its application to the synthesis of a gravity balanced hoist. Mech. Mach. Theory 2019, 139, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, A.S.; Kulkarni, S.A.; Shete, S.S. Dimensional synthesis of mechanism using genetic algorithm. Int. J. Curr. Eng. Technol. 2017, 7, 1572–1580. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Li, X.; Yang, X. Dimensional synthesis for multi-linkage robots based on a niched pareto genetic algorithm. Algorithms 2020, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A.; Muñoyerro, A.; Urízar, M.; Amezua, E. Comprehensive approach for the dimensional synthesis of a four-bar linkage based on path assessment and reformulating the error function. Mech. Mach. Theory 2021, 156, 104126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buśkiewicz, J. Reduced number of design parameters in optimum path synthesis with timing of four-bar linkage. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 2018, 56, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).