Reassessing Plasmonic Interlayers: The Detrimental Role of Au Nanofilms in P3HT:PCBM Organic Solar Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Fabrication

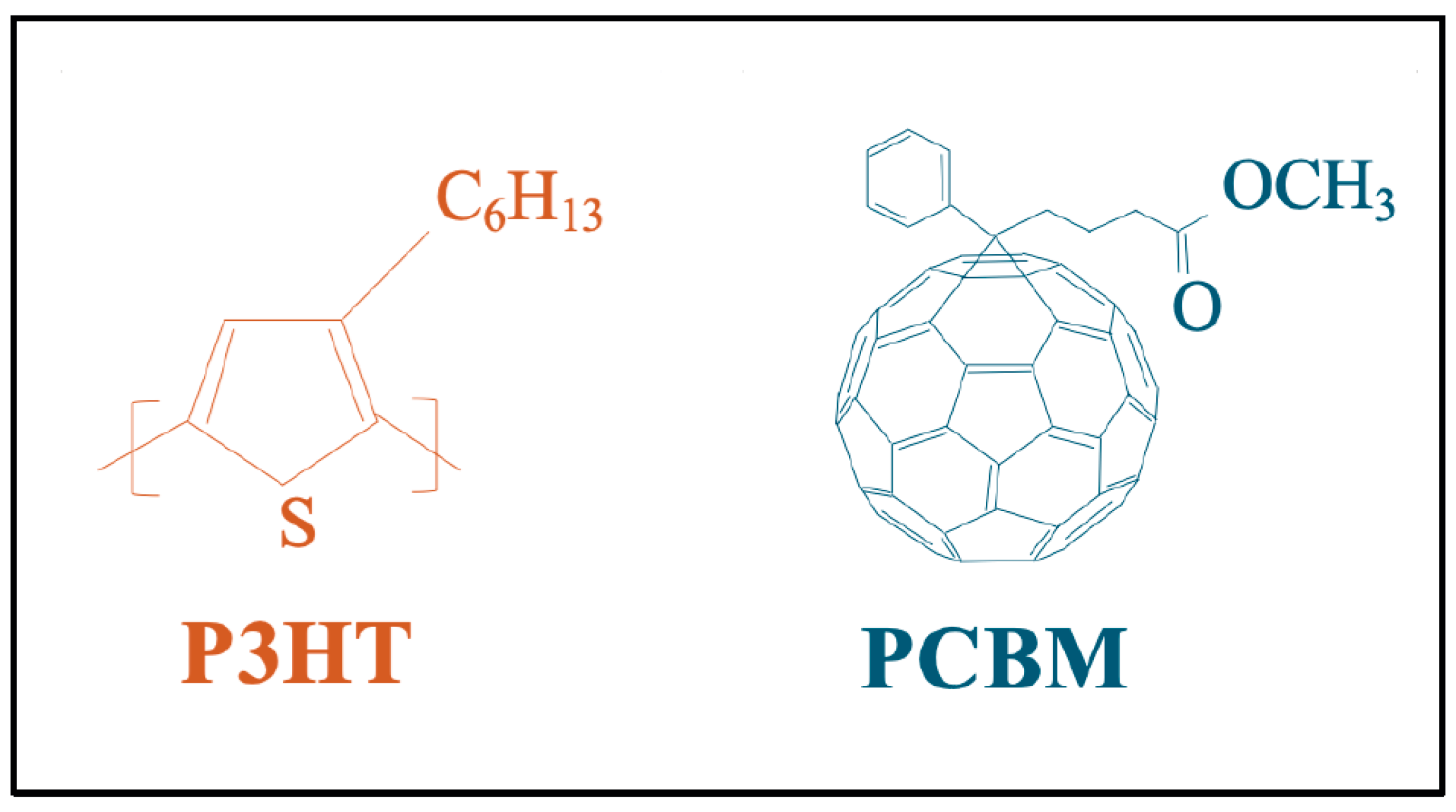

2.1. Chemical Materials

2.2. Instrumentation

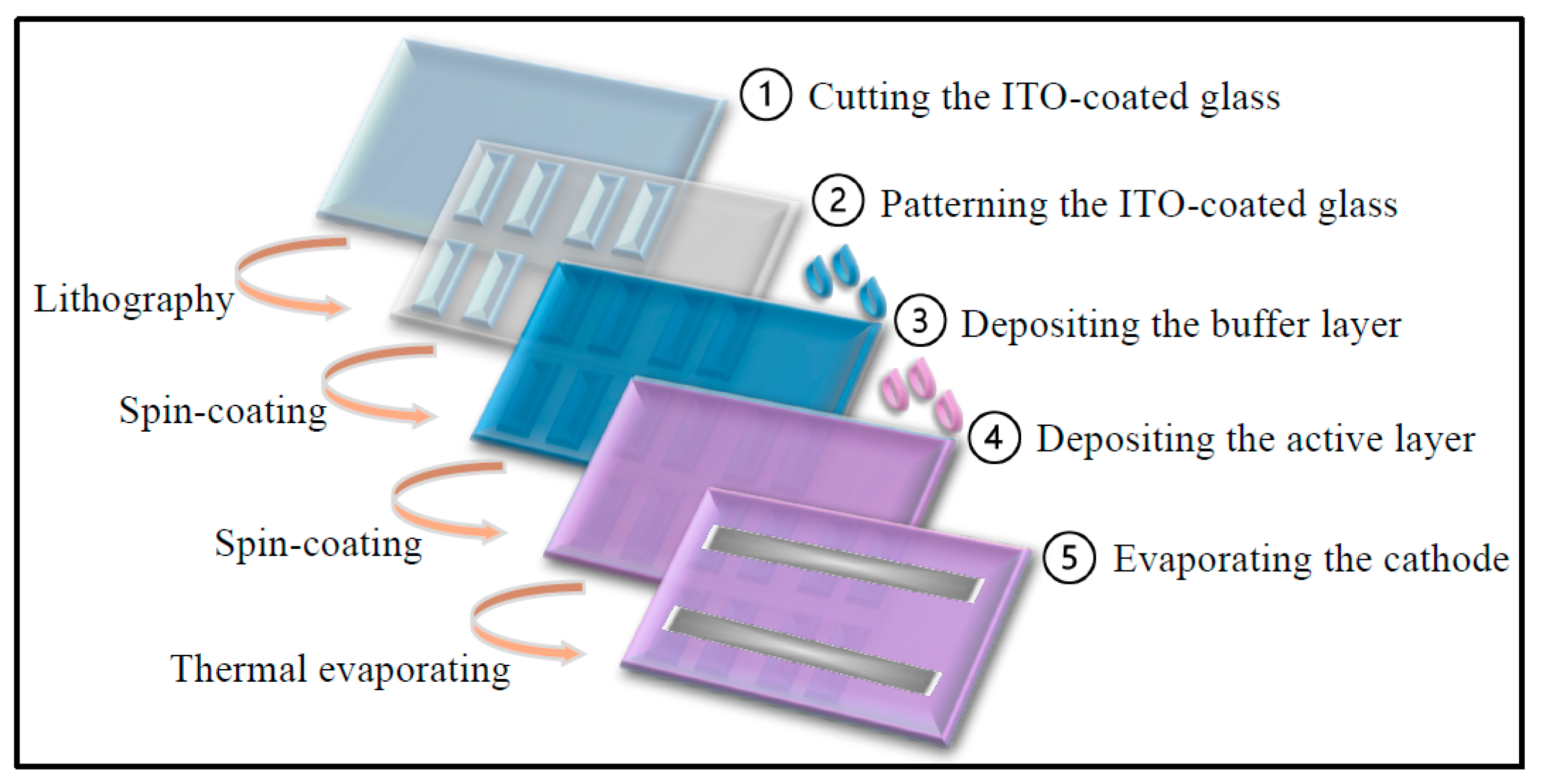

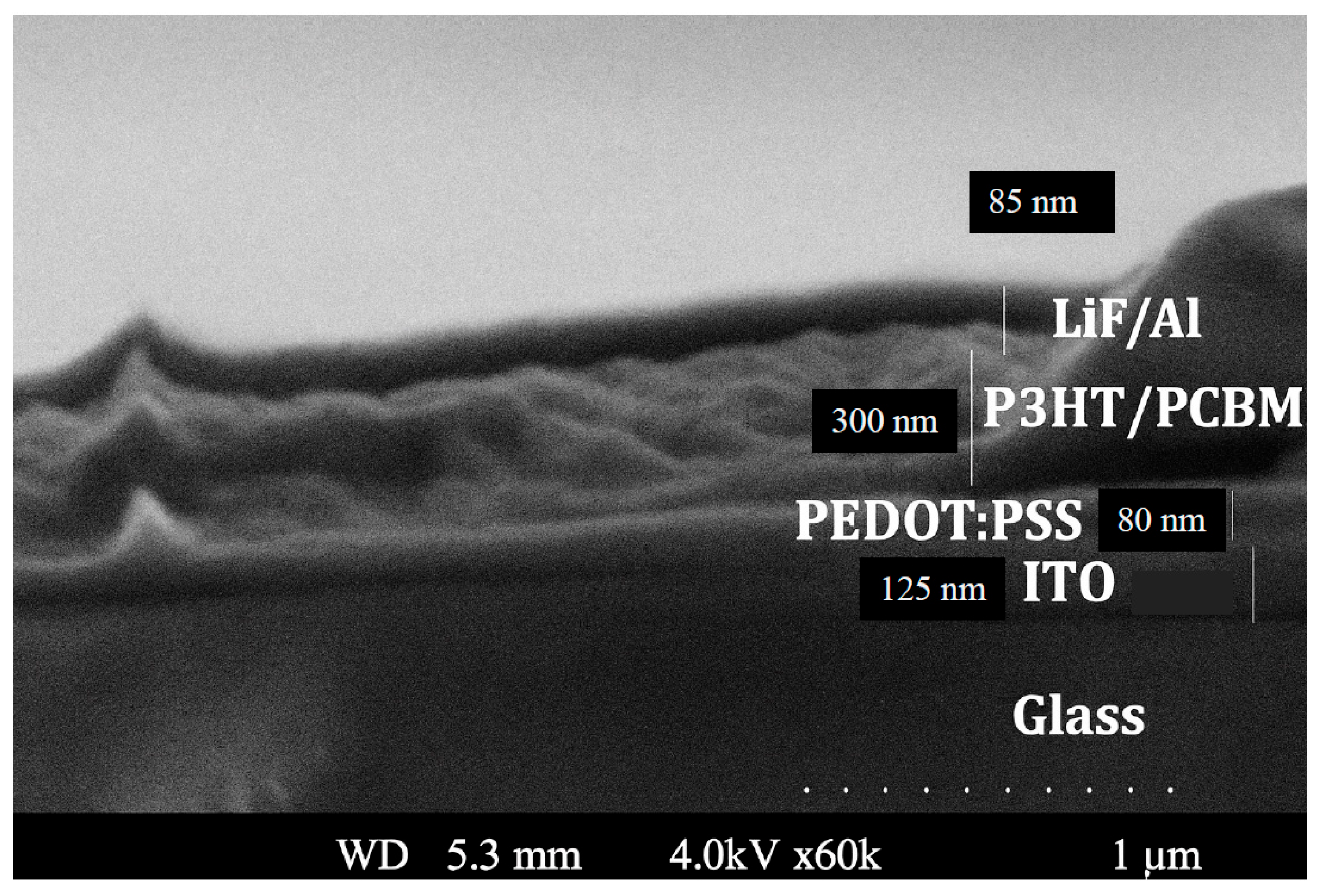

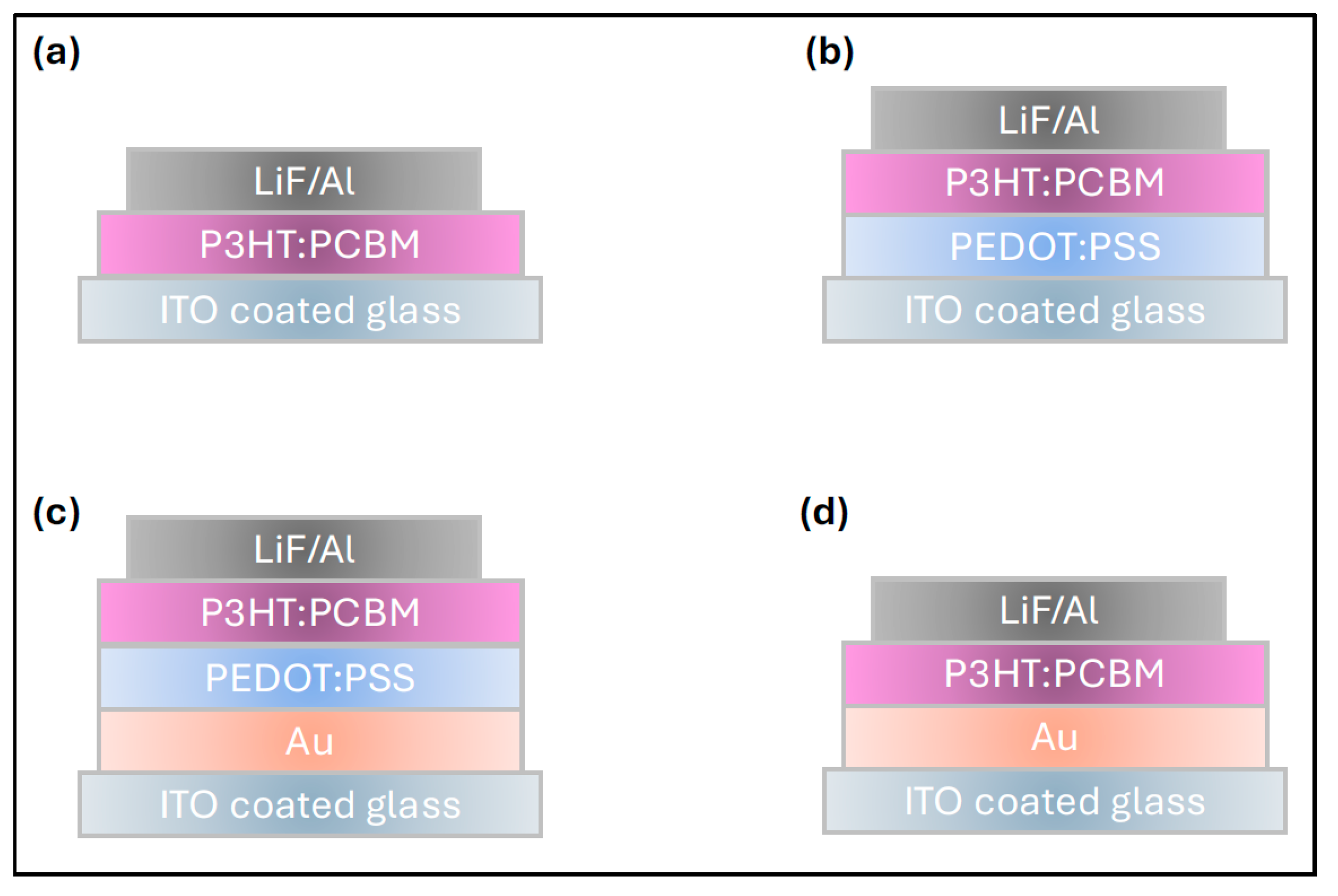

3. Experimental Procedures

4. Measurements and Discussion

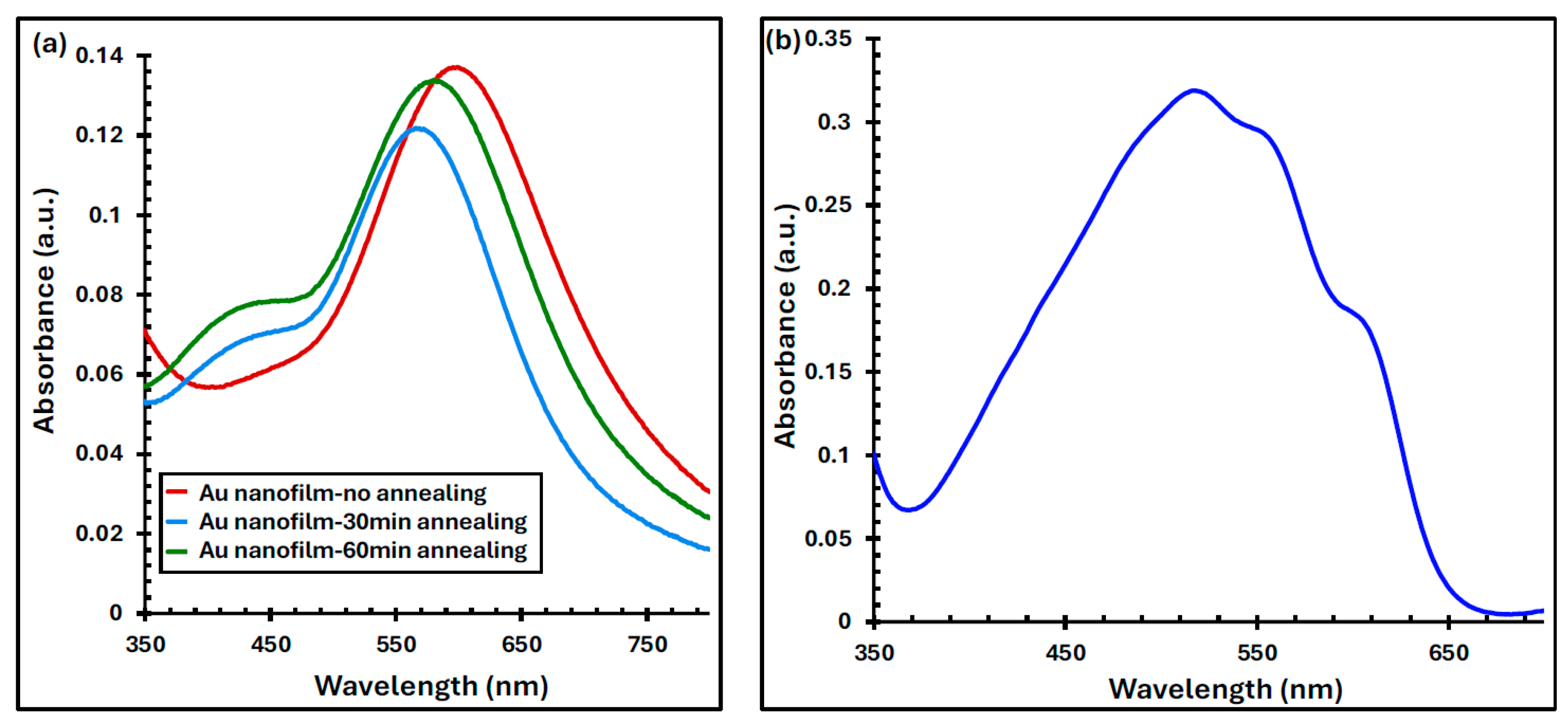

4.1. The Optical Measurement of Au Nanofilms

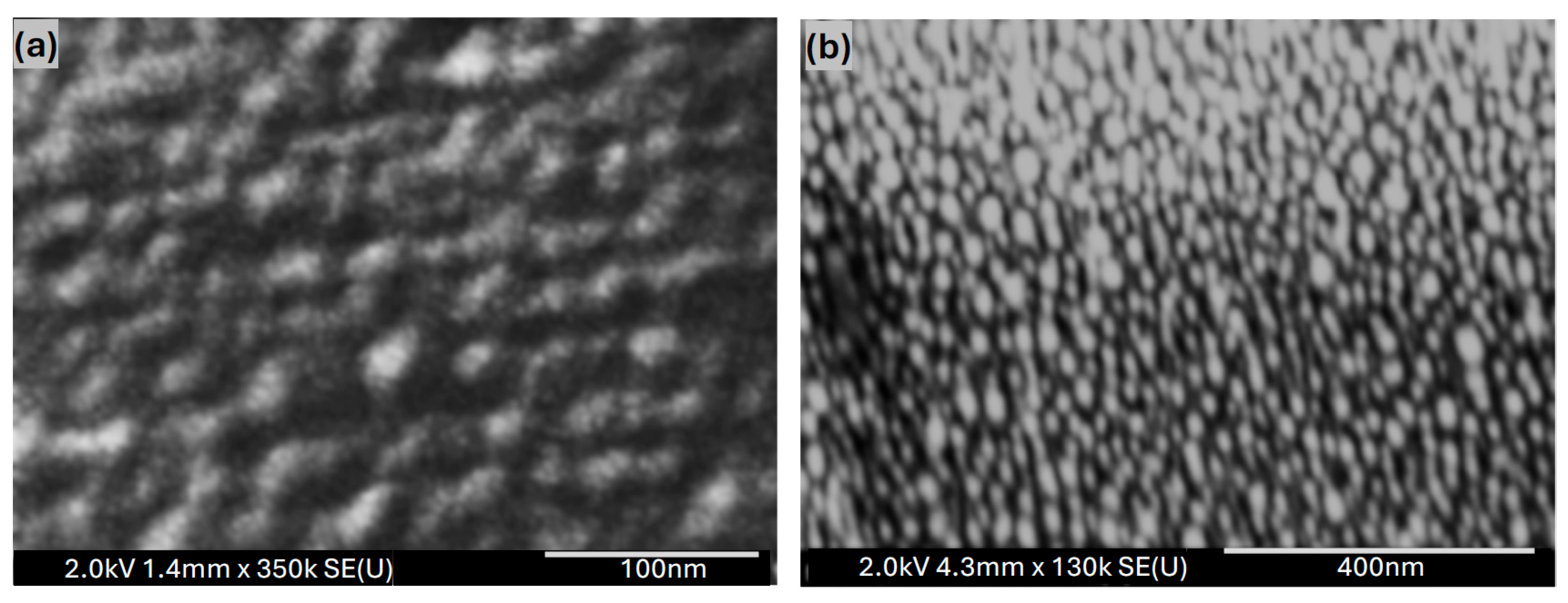

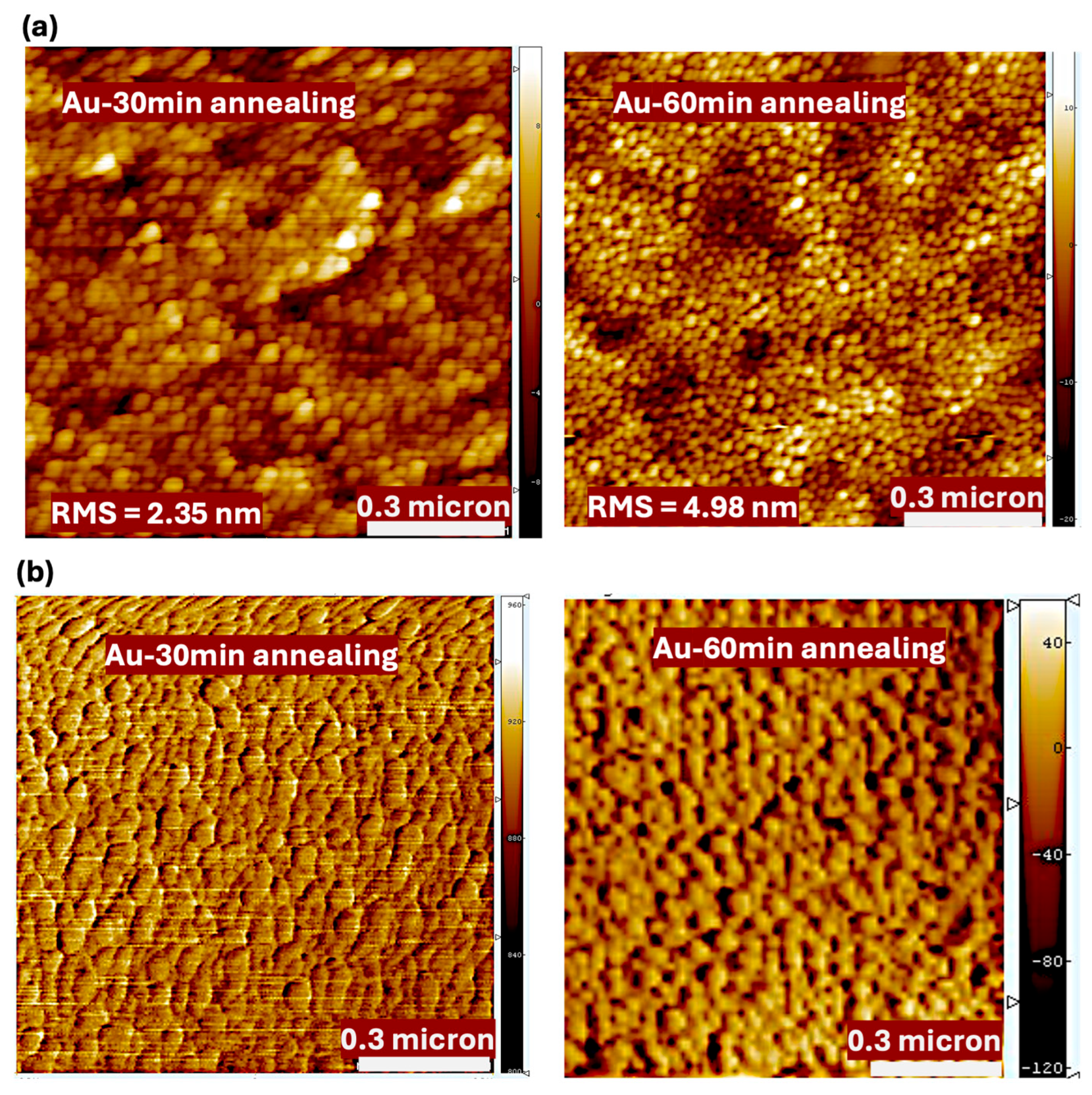

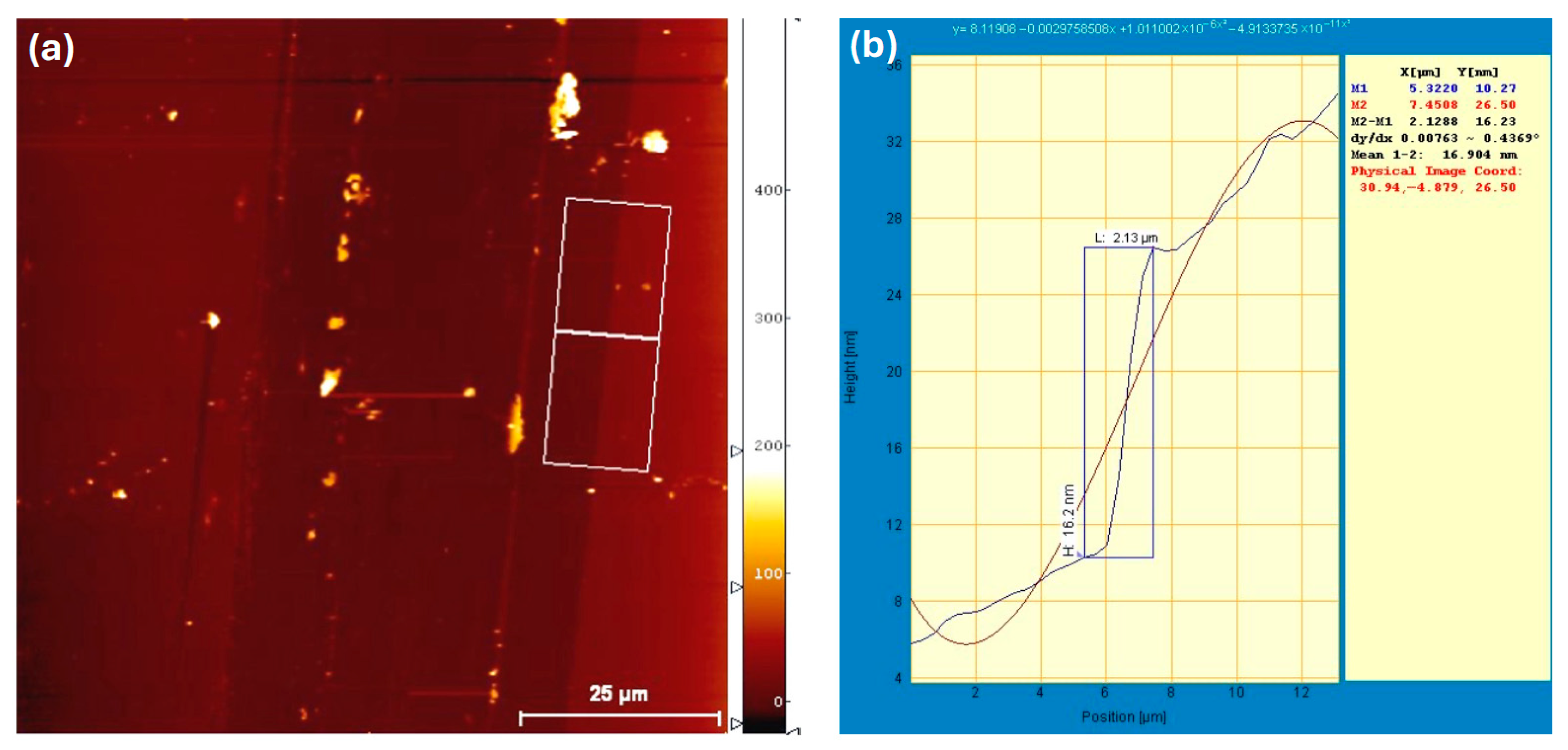

4.2. The Structural Measurement of Au Nanofilms

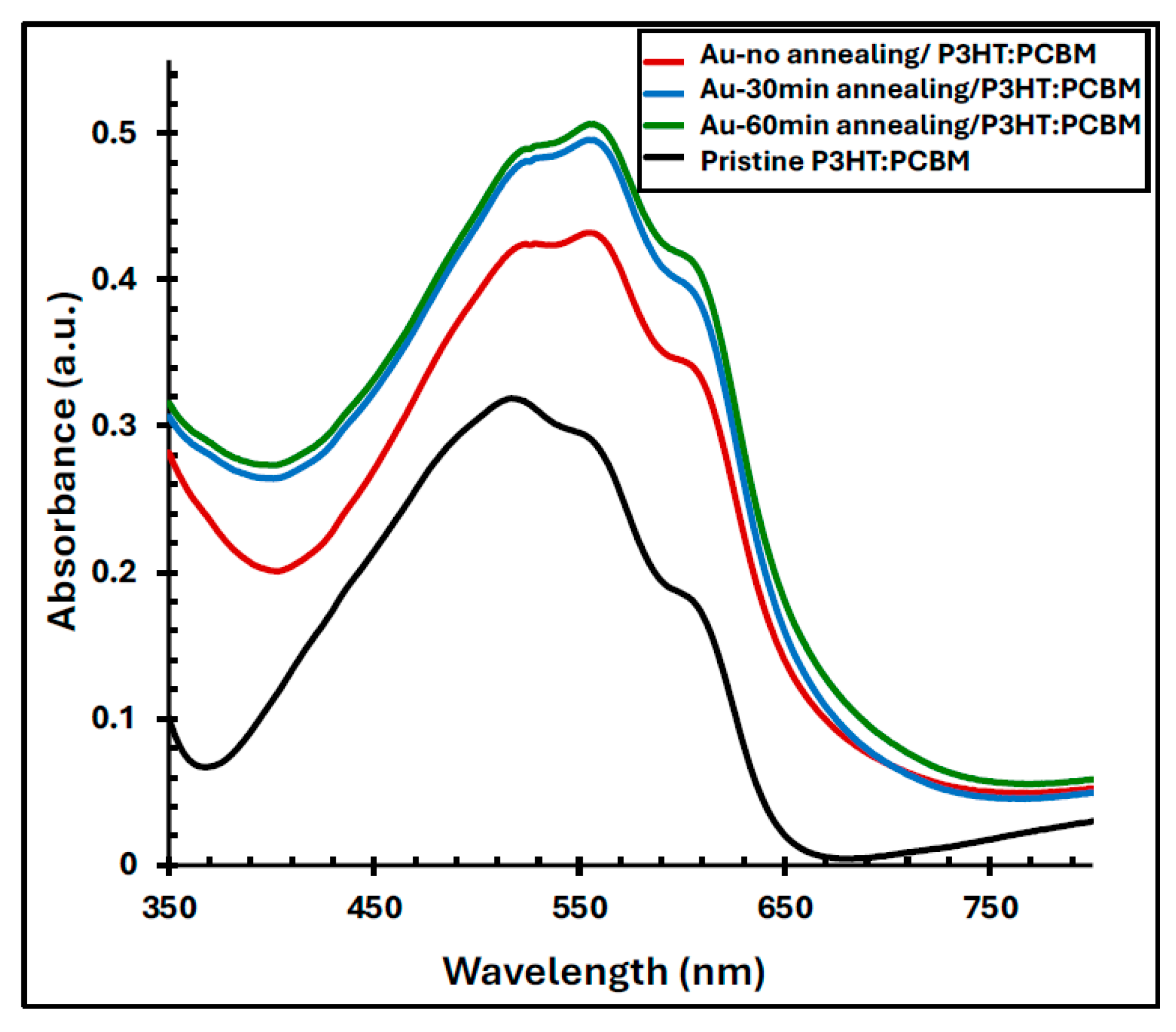

4.3. The Optical Properties of Au/P3HT:PCBM Films

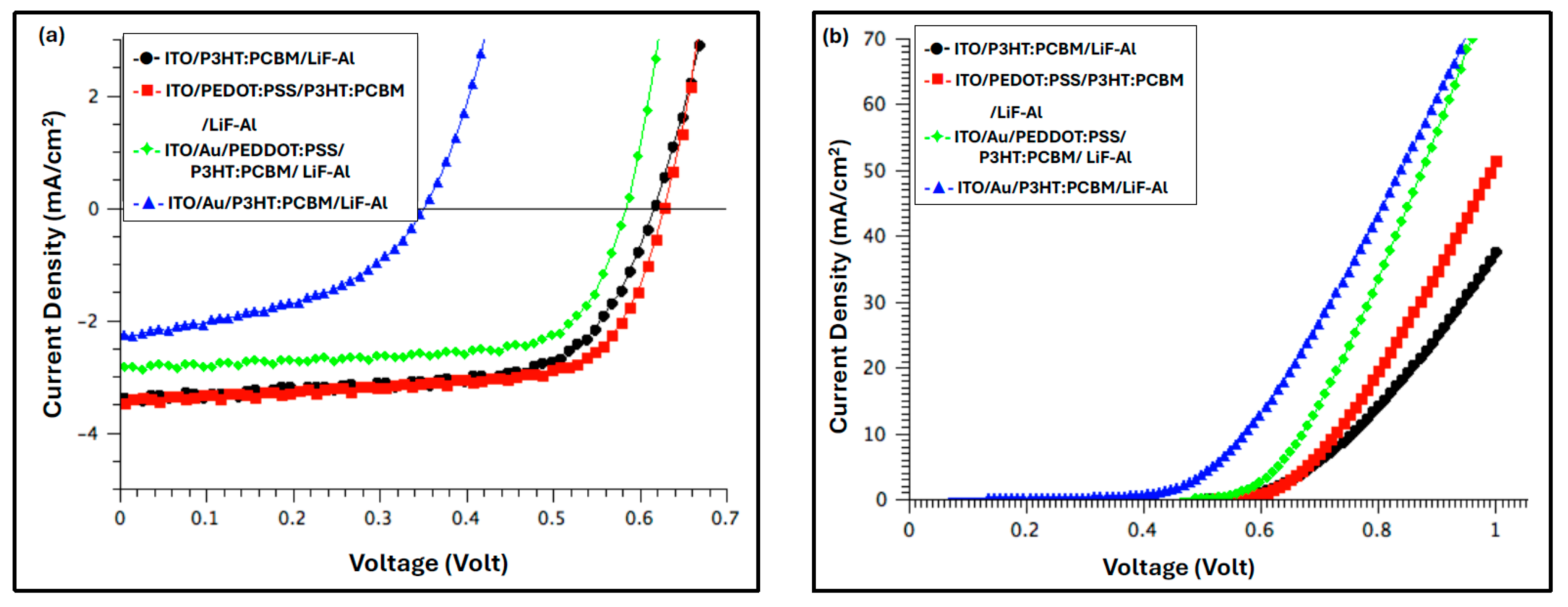

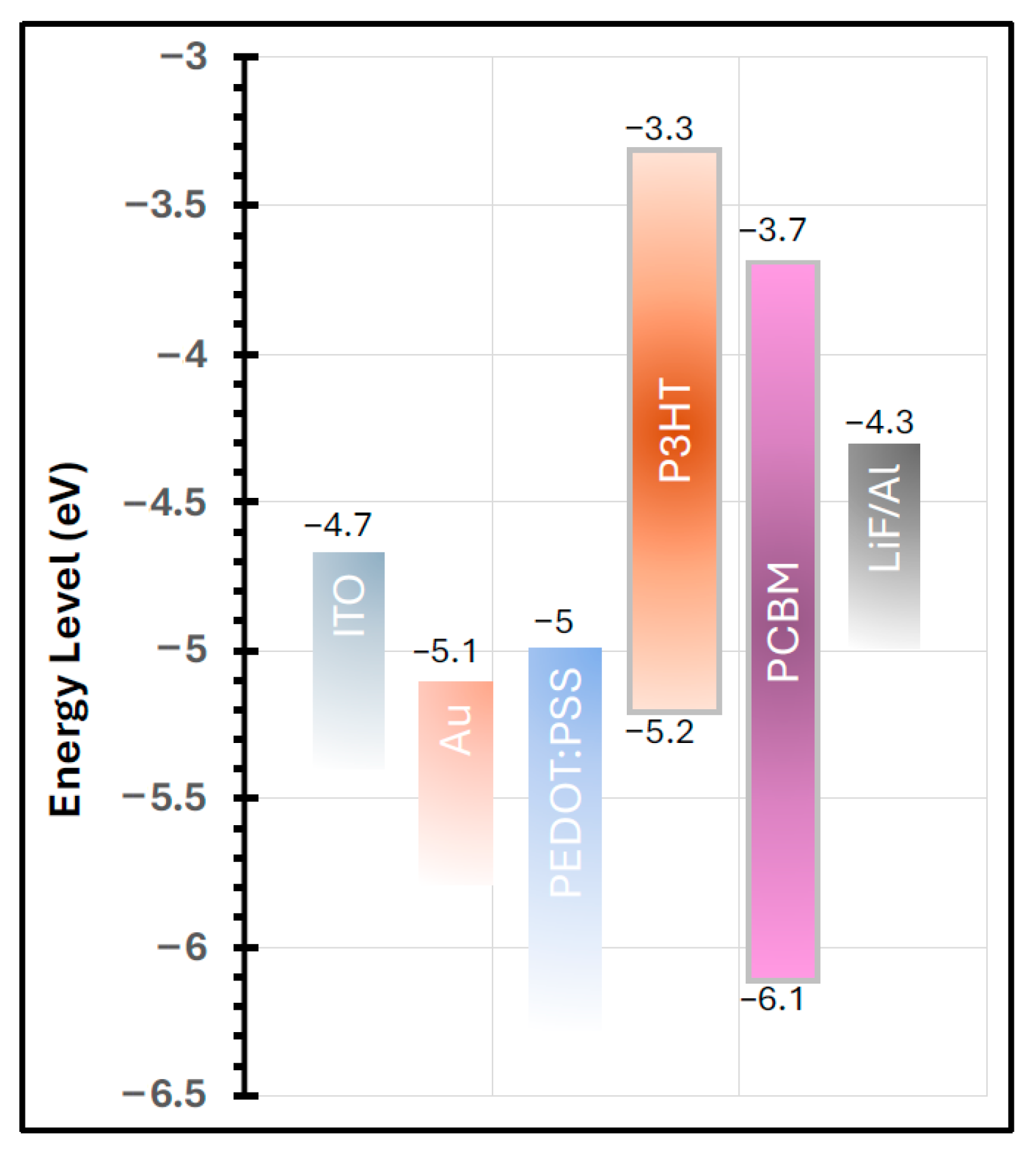

4.4. The Effect of the Annealed Au Nanofilms on OSC Parameters

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahmoud, A.Y.; Zhang, J.; Ma, D.; Izquierdo, R.; Truong, V.-V. Optically-enhanced performance of polymer solar cells with low concentration of gold nanorods in the anodic buffer layer. Org. Electron. 2012, 13, 3102–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.Y.; Zhang, J.; Ma, D.; Izquierdo, R.; Truong, V.-V. Thickness dependent enhanced efficiency of polymer solar cells with gold nanorods embedded in the photoactive layer. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2013, 116, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.Y.; Izquierdo, R.; Truong, V.-V. Gold Nanorods Incorporated Cathode for Better Performance of Polymer Solar Cells. J. Nanomater. 2014, 2014, 464160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabec, C.J.; Gowrisanker, S.; Halls, J.J.M.; Laird, D.; Jia, S.; Williams, S.P. Polymer–Fullerene Bulk-Heterojunction Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 3839–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jia, S.; Cao, Y.; Wang, W.; Yu, P. Design Principles for Nanoparticle Plasmon-Enhanced Organic Solar Cells. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaisar, M.; Zahid, S.; Khera, R.A.; El-Badry, Y.A.; Saeed, M.U.; Mehmood, R.F.; Iqbal, J. Molecular Modeling of Pentacyclic Aromatic Bislactam-Based Small Donor Molecules by Altering Auxiliary End-Capped Acceptors to Elevate the Photovoltaic Attributes of Organic Solar Cells. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 20528–20541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Fukuda, K.; Someya, T. Recent progress in solution-processed flexible organic photovoltaics. npj Flex. Electron. 2022, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Qin, S.; Meng, L.; Ma, Q.; Angunawela, I.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; He, Y.; Lai, W.; Li, N.; et al. High performance tandem organic solar cells via a strongly infrared-absorbing narrow bandgap acceptor. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Ren, J.; Bi, P.; Li, H.; Dai, J.; Zhang, S.; Hou, J. Tandem Organic Solar Cells with 21.5% Efficiency. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e10378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günther, M.; Kazerouni, N.; Blätte, D.; Perea, J.D.; Thompson, B.C.; Ameri, T. Models and mechanisms of ternary organic solar cells. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2023, 8, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Yan, C.; Yu, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Luo, Z.; Tang, B.; Lu, X.; et al. High-Efficiency Ternary Organic Solar Cells with a Good Figure-of-Merit Enabled by Two Low-Cost Donor Polymers. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 2547–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, M.; Benghanem, M.; Almohammedi, A.; Rabia, M. Optimization of the Active Layer P3HT:PCBM for Organic Solar Cell. Coatings 2021, 11, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Gupta, S.K.; Negi, C.M.S. Influence of active layer thickness on photovoltaic performance of PTB7:PC70BM bulk heterojunction solar cell. Superlattices Microstruct. 2019, 135, 106278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y.; Xin, Q.; Zhao, J.; Lin, J. Effect of Active Layer Thickness on the Performance of Polymer Solar Cells Based on a Highly Efficient Donor Material of PTB7-Th. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 16532–16539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharber, M.C. On the Efficiency Limit of Conjugated Polymer: Fullerene-Based Bulk Heterojunction Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 1994–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benaya, N.; Taouti, M.M.; Bougnina, K.; Deghfel, B.; Zoukel, A. Gold nanoparticles in P3HT: PCBM active layer: A simulation of new organic solar cell designs. Solid-State Electron. 2025, 225, 109056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.P.; Pigeon, S.; Izquierdo, R.; Martel, R. Electrical bistability by self-assembled gold nanoparticles in organic diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 183502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.R.; Honold, T.; Gujar, T.P.; Retsch, M.; Fery, A.; Karg, M.; Thelakkat, M. The role of colloidal plasmonic nanostructures in organic solar cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 23155–23163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diukman, I.; Tzabari, L.; Berkovitch, N.; Tessler, N.; Orenstein, M. Controlling absorption enhancement in organic photovoltaic cells by patterning Au nano disks within the active layer. Opt. Express 2011, 19, A64–A71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.K.; Dhawan, A. Plasmonic enhancement of photovoltaic characteristics of organic solar cells by employing parabola nanostructures at the back of the solar cell. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 26780–26792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.-W.; Jun, S.; Kim, B.; Proppe, A.H.; Ouellette, O.; Voznyy, O.; Kim, C.; Kim, J.; Walters, G.; Song, J.H.; et al. Efficient hybrid colloidal quantum dot/organic solar cells mediated by near-infrared sensitizing small molecules. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Yin, F.; Du, Z.; Belfiore, L.A.; Tang, J. Strategically integrating quantum dots into organic and perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 4505–4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X.; Jin, H.; Zhang, W.; Tong, B.; Liu, Y.; Burn, P.L.; Cheng, H.-M.; Ren, W. Extremely efficient flexible organic solar cells with a graphene transparent anode: Dependence on number of layers and doping of graphene. Carbon 2021, 171, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Sarker, A.K.; Park, Y.; Kwak, J.; Song, H.-J.; Lee, C. Study on graphene oxide as a hole extraction layer for stable organic solar cells. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 27199–27206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.-L.; Chen, F.-C.; Hsiao, Y.-S.; Chien, F.-C.; Chen, P.; Kuo, C.-H.; Huang, M.H.; Hsu, C.-S. Surface Plasmonic Effects of Metallic Nanoparticles on the Performance of Polymer Bulk Heterojunction Solar Cells. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelton, M.; Aizpurua, J.; Bryant, G. Metal-Nanoparticle Plasmonics. Laser Photonics Rev. 2008, 2, 136–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitkus, J.; Chang, Y.; Liu, L.; Puttaswamy, S.V.; Chung, T.; Vargas, A.M.M.; Dollery, S.J.; O’COnnell, M.R.; Cai, H.; Tobin, G.J.; et al. Gold Nanoparticle Enabled Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance on Unique Gold Nanomushroom Structures for On-Chip CRISPR-Cas13a Sensing. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 2201261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alebrahim, M.A.; Ahmad, A.A.; Migdadi, A.; Al-Bataineh, Q.M. Localize surface plasmon resonance of gold nanoparticles and their effect on the polyethylene oxide nanocomposite films. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2024, 679, 415805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maktoof, A.S.; Mohammed, G.H.; Abbas, H.H. Effect of annealing process on structural and optical properties of Au-doped thin films (NiO:WO3) fabricated by PLD technique. J. Opt. 2024, 54, 2204–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriubas, M.; Kavaliūnas, V.; Bočkutė, K.; Palevičius, P.; Kaminskas, M.; Rinkevičius, Ž.; Ragulskis, M.; Laukaitis, G. Formation of Au nanostructures on the surfaces of annealed TiO2 thin films. Surfaces Interfaces 2021, 25, 101239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milićević, N.; Novaković, M.; Potočnik, J.; Milović, M.; Rakočević, L.; Abazović, N.; Pjević, D. Influencing surface phenomena by Au diffusion in buffered TiO2-Au thin films: Effects of deposition and annealing processing. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 30, 101811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; McMahon, J.M.; Schatz, G.C.; Gray, S.K.; Sun, Y. Reversing the size-dependence of surface plasmon resonances. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 14530–14534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J.; Huang, T.; Nallathamby, P.D.; Xu, X.-H.N. Wavelength Dependent Specific Plasmon Resonance Coupling of Single Silver Nanoparticles with EGFP. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 17623–17630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Kriegel, I.; Milliron, D.J. Shape-Dependent Field Enhancement and Plasmon Resonance of Oxide Nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 6227–6238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Kunwar, S.; Sui, M.; Li, M.-Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lee, J. Effect of Annealing Temperature on Morphological and Optical Transition of Silver Nanoparticles on c-Plane Sapphire. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 18, 3466–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chokboribal, J.; Vanidshow, W.; Yuwasonth, W.; Chananonnawathorn, C.; Waiwijit, U.; Hincheeranun, W.; Dhanasiwawong, K.; Horprathum, M.; Rattana, T.; Sujinnapram, S.; et al. Annealed plasmonic Ag nanoparticle films for surface enhanced fluorescence substrate. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 3492–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalegno, M.; Famulari, A.; Meille, S.V. Modeling of Poly(3-hexylthiophene) and Its Oligomer’s Structure and Thermal Behavior with Different Force Fields: Insights into the Phase Transitions of Semiconducting Polymers. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 2398–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwater, H.A.; Polman, A. Plasmonics for improved photovoltaic devices. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krebs, F.C.; Alstrup, J.; Spanggaard, H.; Larsen, K.; Kold, E. Production of large-area polymer solar cells by industrial silk screen printing, lifetime considerations and lamination with polyethyleneterephthalate. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2004, 83, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, F.C.; Carlé, J.E.; Cruys-Bagger, N.; Andersen, M.; Lilliedal, M.R.; Hammond, M.A.; Hvidt, S. Lifetimes of organic photovoltaics: Photochemistry, atmosphere effects and barrier layers in ITO-MEHPPV: PCBM-aluminium devices. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2005, 86, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallata, A.A.; Bahabry, R.R.; Mahmoud, A.Y. Performance Degradation of Polymer Solar Cells Measured in High Humidity Environment. J. Nanoelectron. Optoelectron. 2021, 16, 1182–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadem, B.; Hassan, A.; Cranton, W. Efficient P3HT:PCBM bulk heterojunction organic solar cells; effect of post deposition thermal treatment. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 7038–7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Stott, N.E.; Zeng, J.; Li, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Chu, L.; Song, W. PEDOT:PSS materials for optoelectronics, thermoelectrics, and exible and stretchable electronics. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 18561–18591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Ke, Q.; Wu, J.-R.; Lin, C.-C.; Chang, S.H. Understanding the PEDOT:PSS, PTAA and P3CT-X Hole-Transport-Layer-Based Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. Polymers 2022, 14, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.-C.; Wu, J.-L.; Lee, C.-L.; Hong, Y.; Kuo, C.-H.; Huang, M.H. Plasmonic-enhanced polymer photovoltaic devices incorporating solution-processable metal nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 95, 013305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medel-Ruiz, C.I.; Chiu, R.; Sevilla-Escoboza, J.R.; Casillas-Rodríguez, F.J. Nanoscale Surface Roughness Effects on Photoluminescence and Resonant Raman Scattering of Cadmium Telluride. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimpour, Z.; Mansour, N. Annealing effects on electrical behavior of gold nanoparticle film: Conversion of ohmic to non-ohmic conductivity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 394, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmak, K.; Rickman, J.M.; Patrick, M.J. Advances in Experimental Studies of Grain Growth in Thin Films. JOM 2024, 76, 3622–3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadias, G.; Chason, E.; Keckes, J.; Sebastiani, M.; Thompson, G.B.; Barthel, E.; Doll, G.L.; Murray, C.E.; Stoessel, C.H.; Martinu, L. Review Article: Stress in thin films and coatings: Current status, challenges, and prospects. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2018, 36, 020801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyak, L.; Osinsky, A.; Schulte, A. Minority carrier transport in GaN and related materials. Solid-State Electron. 2001, 45, 1687–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lu, W.; Ao, C.K.; Lim, K.W.; Zeng, K.; Soh, S. Nanocavities stabilize charge: Surface topology is a general strategy for controlling charge dissipation. Mater. Today Phys. 2023, 35, 101105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Yang, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, F.; Li, H.; Hong, K. Impact of Surface Roughness on Partition and Selectivity of Ionic Liquids Mixture in Porous Electrode. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandi, S.K.; Liu, X.; Venkatachalam, D.K.; Elliman, R.G. Effect of Electrode Roughness on Electroforming inHfO2and Defect-Induced Moderation of Electric-Field Enhancement. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2015, 4, 064010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.Z.; Liaquat, M. Effects of non-uniform electric field on the charge collection efficiency in radiation detectors: Deviation from Hecht formula. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 138, 024502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Device Configuration | VOC (V) | JSC (mA/cm2) | FF % | RS (Ω cm2) | PCE% | Δ % PCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITO/P3HT:PCBM/LiF-Al | 0.62 | −3.37 | 65.59 | 0.53 | 1.4 | −12% |

| ITO/PEDOT:PSS/P3HT:PCBM/LiF-Al | 0.62 | −3.74 | 67.67 | 0.38 | 1.6 | - |

| ITO/Au/PEDOT:PSS/P3HT:PCBM/LiF-Al | 0.59 | −2.84 | 69.09 | 0.25 | 1.2 | −26% |

| ITO/Au/P3HT:PCBM/Li-Al | 0.35 | −2.27 | 45.55 | 0.31 | 0.4 | −77% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahmoud, A.Y. Reassessing Plasmonic Interlayers: The Detrimental Role of Au Nanofilms in P3HT:PCBM Organic Solar Cells. Polymers 2025, 17, 3262. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243262

Mahmoud AY. Reassessing Plasmonic Interlayers: The Detrimental Role of Au Nanofilms in P3HT:PCBM Organic Solar Cells. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3262. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243262

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahmoud, Alaa Y. 2025. "Reassessing Plasmonic Interlayers: The Detrimental Role of Au Nanofilms in P3HT:PCBM Organic Solar Cells" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3262. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243262

APA StyleMahmoud, A. Y. (2025). Reassessing Plasmonic Interlayers: The Detrimental Role of Au Nanofilms in P3HT:PCBM Organic Solar Cells. Polymers, 17(24), 3262. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243262