TiO2, GO, and TiO2/GO Coatings by APPJ on Waste ABS/PMMA Composite Filaments Filled with Carbon Black, Graphene, and Graphene Foam: Morphology, Wettability, Thermal Stability, and 3D Printability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Polymeric Mixture Preparations

2.2. D Printing of Test Specimens and Demonstrator Components

2.3. Surface Coating with TiO2 and GO

2.4. Characterization Techniques

3. Results and Discussion

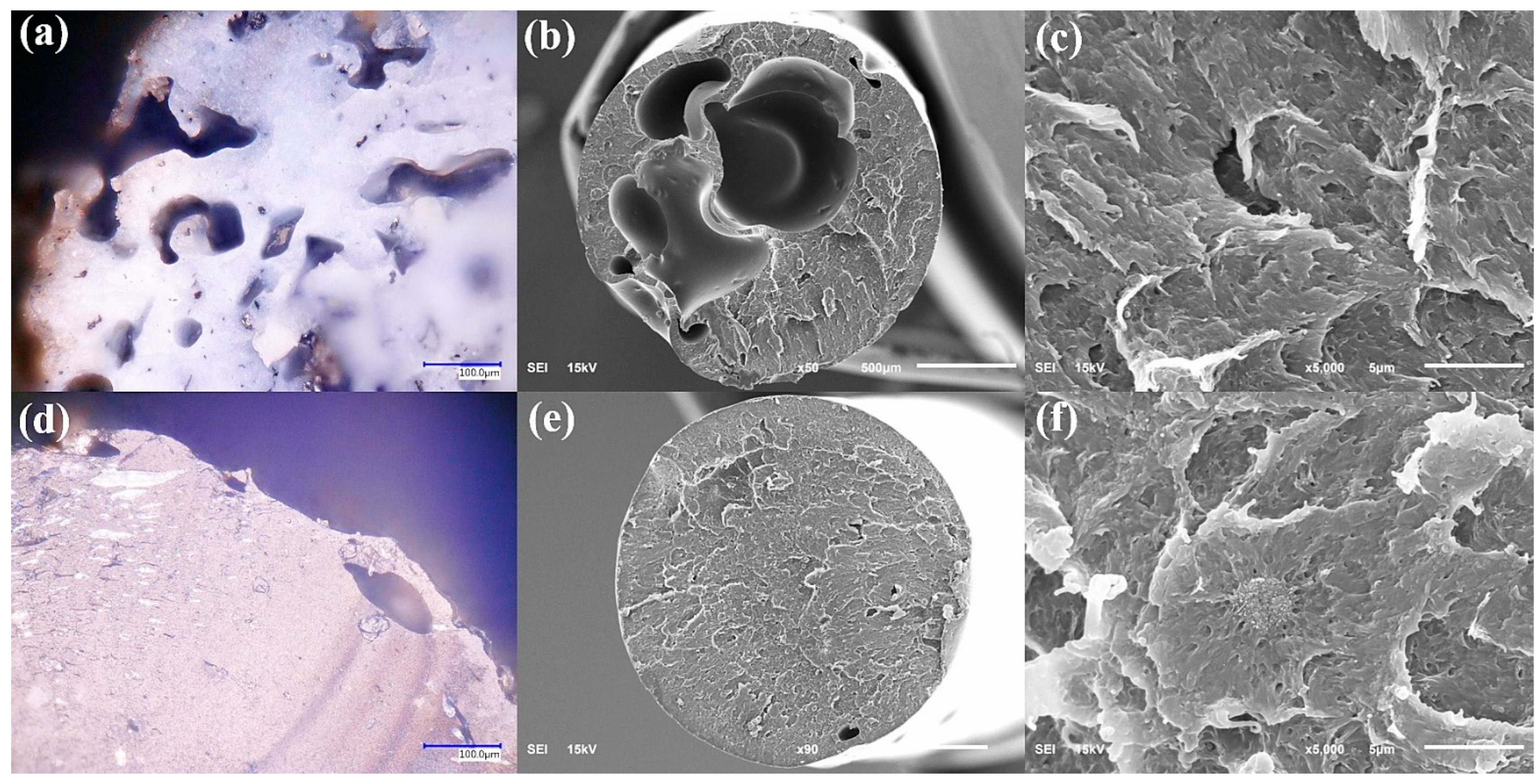

3.1. PMMA Filaments

3.2. ABS Filaments

3.3. TiO2 and GO Coatings

3.4. Wettability of Composite Surfaces

3.5. Calorimetry and Thermal Stability

4. Conclusions

- Waste thermoplastics as viable matrices for composite filaments

- 2.

- Filler-dependent morphology in implications

- 3.

- Conformal APPJ coatings on complex composite substrates

- 4.

- Thermal stability and printability range

- 5.

- Outlook for circular, surface-engineered polymer manufacturing

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ding, Y.; Abeykoon, C.; Perera, Y.S. The effects of extrusion parameters and blend composition on the mechanical, rheological and thermal properties of LDPE/PS/PMMA ternary polymer blends. Adv. Ind. Manuf. Eng. 2022, 4, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousfi, M.; Belhadj, A.; Lamnawar, K.; Maazouz, A. 3D printing of PLA and PMMA multilayered model polymers: An innovative approach for a better-controlled pellet multi-extrusion process. ESAFORM 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melentiev, R.; Yudhanto, A.; Tao, R.; Vuchkov, T.; Lubineau, G. Metallization of polymers and composites: State-of-the-art approaches. Mater. Des. 2022, 221, 110958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasekaran, K.; Heijmans, T.; van Bennekom, S.; Woldhuis, H.; Wijnia, S.; de With, G.; Friedrich, H. 3D printing of CNT- and graphene-based conductive polymer nanocomposites by fused deposition modeling. Appl. Mater. Today 2017, 9, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Nilsson, F.; Qin, Y.; Yang, G.; Pan, Y.; Liu, X.; Hernandez Rodriguez, G.; Chen, J.; Zhang, C.; Schubert, D.W. Electrical conductivity and mechanical properties of melt-spun ternary composites comprising PMMA, carbon fibers and carbon black. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2017, 150, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-H.; Shiu, J.-W.; Rwei, S.-P. Preparation and characterization of PMMA encapsulated carbon black for water-based digital jet printing ink on different fibers of cotton and PET. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 648, 129450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; Yan, C.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, B. Carbon black reinforced polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA)-based composite particles: Preparation, characterization, and application. J. Geophys. Eng. 2017, 14, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallés, C.; Papageorgiou, D.G.; Lin, F.; Li, Z.; Spencer, B.F.; Young, R.J.; Kinloch, I.A. PMMA-grafted graphene nanoplatelets to reinforce the mechanical and thermal properties of PMMA composites. Carbon 2020, 157, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Pan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wu, J.; Xia, R.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Su, L.; Miao, J.; Qian, J.; et al. Filler network structure in graphene nanoplatelet (GNP)-filled polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) composites: From thermorheology to electrically and thermally conductive properties. Polym. Test. 2020, 89, 106575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, B.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Z. Graphene-based flame retardants: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 8271–8295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, G.; Hendrix, J.; Kear, B.; Lynch, J.; Nosker, T. Graphene-Reinforced Polymer Matrix Composites. Patent WO 2016/018995, 4 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Sandhu, G.; Penna, R.; Farina, I. Investigations for Thermal and Electrical Conductivity of ABS-Graphene Blended Prototypes. Materials 2017, 10, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, S.; Fambri, L.; Pegoretti, A. Filaments Production and Fused Deposition Modelling of ABS/Carbon Nanotubes Composites. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magallón-Cacho, L.; Pérez-Bueno, J.J.; Meas-Vong, Y.; Stremsdoerfer, G.; Espinoza-Beltrán, F.J. Surface modification of acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS) with heterogeneous photocatalysis (TiO2) for the substitution of the etching stage in the electroless process. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 206, 1410–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvear-Daza, J.J.; Pais-Ospina, D.; Marín-Silva, D.A.; Pinotti, A.; Damonte, L.; Pizzio, L.R.; Osorio-Vargas, P.; Rengifo-Herrera, J.A. Facile photocatalytic immobilization strategy for P-25 TiO2 nanoparticles on low density polyethylene films and their UV-A photo-induced super hydrophilicity and photocatalytic activity. Catal. Today 2021, 372, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, R.; Nandan, D.; Haleem, A.; Bahl, S.; Javaid, M. Experimental study of electroless plating on acrylonitrile butadiene styrene polymer for obtaining new eco-friendly chromium-free processes. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 28, 1575–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubdub, I.; Al-Yaari, M. Thermal Behavior of Mixed Plastics at Different Heating Rates: I. Pyrolysis Kinetics. Polymers 2021, 13, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Li, D.; Jiang, W.; Gu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Z. 3D Printable Graphene Composite. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, R.; Singh, M.; Singh, T.; Batish, A. Multi material 3D printing of PLA-PA6/TiO2 polymeric matrix: Flexural, wear and morphological properties. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2022, 35, 2105–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhou, G.X.; He, P.G.; Yang, Z.H.; Jia, D.C. 3D printing strong and conductive geo-polymer nanocomposite structures modified by graphene oxide. Carbon 2017, 117, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos Espinoza, R.; Sierra-Gómez, U.; Magdaleno López, C.; González-Gutiérrez, L.V.; Estela Castillo, B.; Luna Bárcenas, G.; Elizalde Peña, E.A.; Pérez Bueno, J.J.; Fernández Tavizón, S.; España Sánchez, B.L. Zwitterion-decorated graphene oxide nanosheets with aliphatic amino acids under specific pH conditions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 555, 149723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorski, M.R.; Esenther, J.M.; Ahmed, Z.; Miller, A.E.; Hartings, M.R. The chemical, mechanical, and physical properties of 3D printed materials composed of TiO2-ABS nanocomposites. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2016, 17, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevastaki, M.; Suchea, M.P.; Kenanakis, G. 3D Printed Fully Recycled TiO2-Polystyrene Nanocomposite Photocatalysts for Use against Drug Residues. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumnate, C.; Pongwisuthiruchte, A.; Pattananuwat, P.; Potiyaraj, P. Fabrication of ABS/Graphene Oxide Composite Filament for Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) 3D Printing. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2018, 2830437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chao, X.; Liang, J.; Wang, B.; Sun, M. Enhanced Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Composites Reinforced with Silane-Modified Al2O3 Nanoparticles: An Experimental Study. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Wang, S.-C.; Chen, H.-W.; Chou, T.-Y.; Chang, C.-S. High-Efficiency Photocatalytic Reactors Fabricated via Rapid DLP 3D Printing: Enhanced Dye Photodegradation with Optimized TiO2 Loading and Structural Design. ACS ES&T Water 2024, 4, 1883–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, I.S.O.; Manrique, Y.A.; Paiva, D.; Faria, J.L.; Santos, R.J.; Silva, C.G. Efficient photocatalytic reactors via 3D printing: SLA fabrication and TiO2 hybrid materials. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 2275–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.; Afzali Naniz, M.; Kouhi, M.; Saberi, A.; Zolfagharian, A.; Bodaghi, M. Recent progress in extrusion 3D bioprinting of hydrogel biomaterials for tissue regeneration: A comprehensive review with focus on advanced fabrication techniques. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 535–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, J.; Luo, H.; Li, S.; Yang, J. Physicochemical and Photocatalytic Properties of 3D-Printed TiO2/Chitin/Cellulose Composite with Ordered Porous Structures. Polymers 2022, 14, 5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabello Mendez, J.A.; Pérez Bueno, J. de J.; Meas Vong, Y.; Meneses Rodríguez, D.; Pérez Quiroz, J.T.; López Miguel, A. Novel self-assembled graphene oxide coating by atmospheric pressure plasma jet. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2024, 175, 108284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, M.G.; Mendoza López, M.L.; de Jesús Pérez Bueno, J.; Pérez Meneses, J.; Maldonado Pérez, A.X. Polymer Waste Recycling of Injection Molding Purges with Softening for Cutting with Fresnel Solar Collector—A Real Problem Linked to Sustainability and the Circular Economy. Polymers 2024, 16, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magdaleno-López, C.; de Jesús Pérez-Bueno, J. Quantitative evaluation for the ASTM D4541-17/D7234 and ASTM D3359 adhesion norms with digital optical microscopy for surface modifications with flame and APPJ. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2020, 98, 102551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, A.; Mantelli, A.; Tralli, P.; Turri, S.; Levi, M.; Suriano, R. Metallization of Thermoplastic Polymers and Composites 3D Printed by Fused Filament Fabrication. Technologies 2021, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Gilmer, E.L.; Biria, S.; Bortner, M.J. Importance of Polymer Rheology on Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing: Correlating Process Physics to Print Properties. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 1218–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.X.; Yu, Y.G.; Yang, Z.H.; Jia, D.C.; Poulin, P.; Zhou, Y.; Zhong, J. 3D Printing Graphene Oxide Soft Robotics. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 3664–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jnido, G.; Ohms, G.; Viöl, W. One-Step Deposition of Polyester/TiO2 Coatings by Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet on Wood Surfaces for UV and Moisture Protection. Coatings 2020, 10, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, E.; Kotsilkova, R.; Xia, H.; Chen, Y.; Donato, R.K.; Donato, K.; Godoy, A.P.; Di Maio, R.; Silvestre, C.; Cimmino, S.; et al. PLA/Graphene/MWCNT composites with improved electrical and thermal properties suitable for FDM 3D printing applications. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Sole, R.; Lo Porto, C.; Lotito, S.; Ingrosso, C.; Comparelli, R.; Curri, M.L.; Barucca, G.; Fracassi, F.; Palumbo, F.; Milella, A. Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Deposition of Hybrid Nanocomposite Coatings Containing TiO2 and Carbon-Based Nanomaterials. Molecules 2023, 28, 5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olea, M.A.U.; de Jesús Pérez Bueno, J.; Pérez, A.X.M. Nanometric and surface properties of semiconductors correlated to photocatalysis and photoelectrocatalysis applied to organic pollutants—A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Chen, H.; Peng, H.; Wang, Z.; Huang, W. Graphene Modified TiO2 Composite Photocatalysts: Mechanism, Progress and Perspective. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Porto, C.; Dell’Edera, M.; De Pasquale, I.; Milella, A.; Fracassi, F.; Curri, M.L.; Comparelli, R.; Palumbo, F. Photocatalytic Investigation of Aerosol-Assisted Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Deposited Hybrid TiO2 Containing Nanocomposite Coatings. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio Uscanga Olea, M.; de Jesús Pérez Bueno, J.; Adrián Díaz Real, J.; Alonso Mares Suárez, A.; Francisco Pérez Robles, J.; Xochitl Maldonado Pérez, A.; Yepes Largo, S. Self-assembled graphene oxide thin films deposited by atmospheric pressure plasma and their hydrogen thermal reduction. Mater. Lett. 2024, 363, 136334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozetič, M. Plasma-Stimulated Super-Hydrophilic Surface Finish of Polymers. Polymers 2020, 12, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Nikiforov, A.; Hegemann, D.; De Geyter, N.; Morent, R.; Ostrikov, K. (Ken) Plasma-controlled surface wettability: Recent advances and future applications. Int. Mater. Rev. 2023, 68, 82–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedler, G.; Antunes, M.; Realinho, V.; Velasco, J.I. Thermal stability of polycarbonate-graphene nanocomposite foams. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 1297–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedler, G.; Antunes, M.; Velasco, J.I. Low density polycarbonate–graphene nanocomposite foams produced by supercritical carbon dioxide two-step foaming. Thermal stability. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 92, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maldonado Pérez, A.X.; Arenas Flores, A.D.; Pérez Bueno, J.d.J.; Mendoza López, M.L.; Casados Mexicano, Y.; Reyes Araiza, J.L.; Manzano-Ramírez, A.; Vásquez García, S.R.; Flores-Ramírez, N.; Montoya Suárez, C.; et al. TiO2, GO, and TiO2/GO Coatings by APPJ on Waste ABS/PMMA Composite Filaments Filled with Carbon Black, Graphene, and Graphene Foam: Morphology, Wettability, Thermal Stability, and 3D Printability. Polymers 2025, 17, 3263. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243263

Maldonado Pérez AX, Arenas Flores AD, Pérez Bueno JdJ, Mendoza López ML, Casados Mexicano Y, Reyes Araiza JL, Manzano-Ramírez A, Vásquez García SR, Flores-Ramírez N, Montoya Suárez C, et al. TiO2, GO, and TiO2/GO Coatings by APPJ on Waste ABS/PMMA Composite Filaments Filled with Carbon Black, Graphene, and Graphene Foam: Morphology, Wettability, Thermal Stability, and 3D Printability. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3263. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243263

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaldonado Pérez, Alejandra Xochitl, Alma Delfina Arenas Flores, José de Jesús Pérez Bueno, Maria Luisa Mendoza López, Yolanda Casados Mexicano, José Luis Reyes Araiza, Alejandro Manzano-Ramírez, Salomón Ramiro Vásquez García, Nelly Flores-Ramírez, Carlos Montoya Suárez, and et al. 2025. "TiO2, GO, and TiO2/GO Coatings by APPJ on Waste ABS/PMMA Composite Filaments Filled with Carbon Black, Graphene, and Graphene Foam: Morphology, Wettability, Thermal Stability, and 3D Printability" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3263. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243263

APA StyleMaldonado Pérez, A. X., Arenas Flores, A. D., Pérez Bueno, J. d. J., Mendoza López, M. L., Casados Mexicano, Y., Reyes Araiza, J. L., Manzano-Ramírez, A., Vásquez García, S. R., Flores-Ramírez, N., Montoya Suárez, C., & Pérez Mendoza, E. B. (2025). TiO2, GO, and TiO2/GO Coatings by APPJ on Waste ABS/PMMA Composite Filaments Filled with Carbon Black, Graphene, and Graphene Foam: Morphology, Wettability, Thermal Stability, and 3D Printability. Polymers, 17(24), 3263. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243263