The Influence of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Dispersion, Rheology, and Mechanical Properties of Epoxy-Based Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

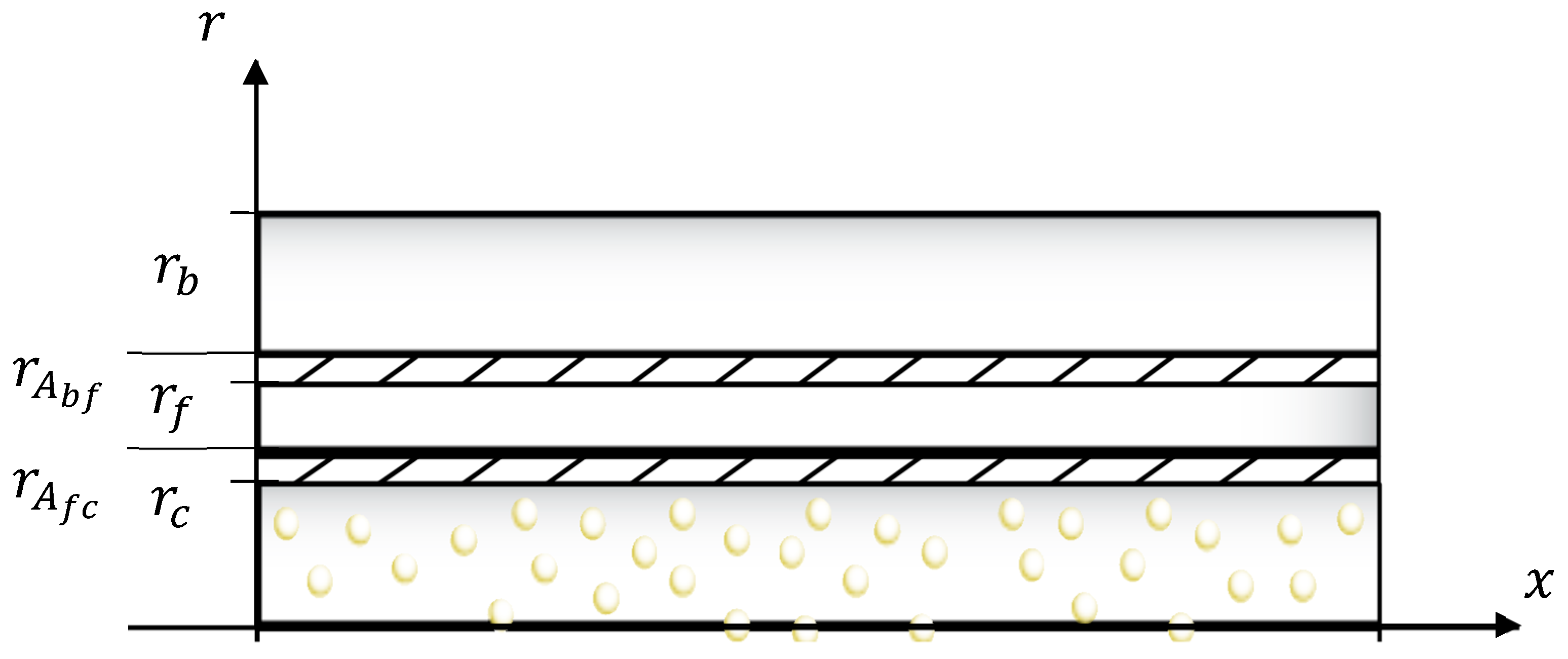

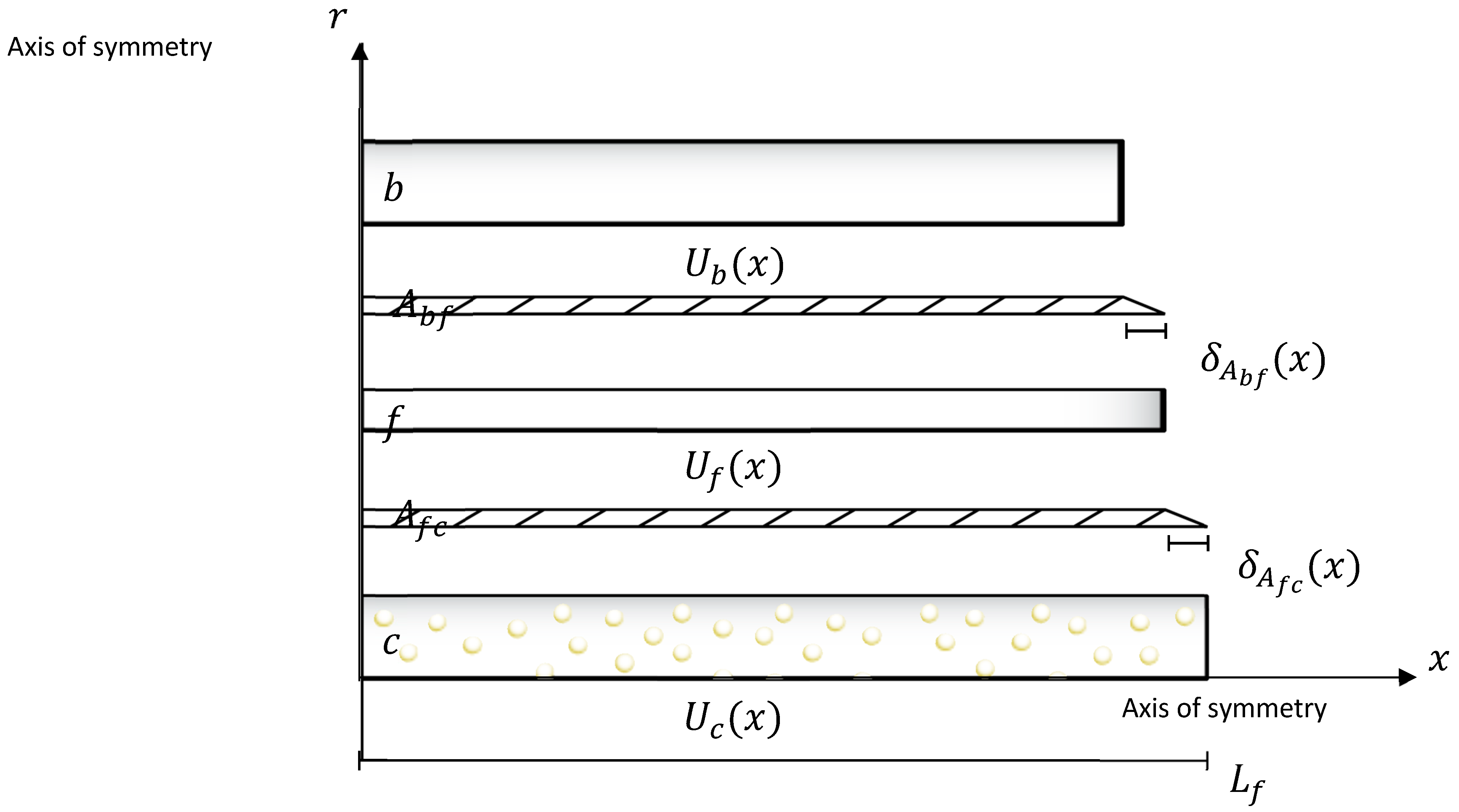

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

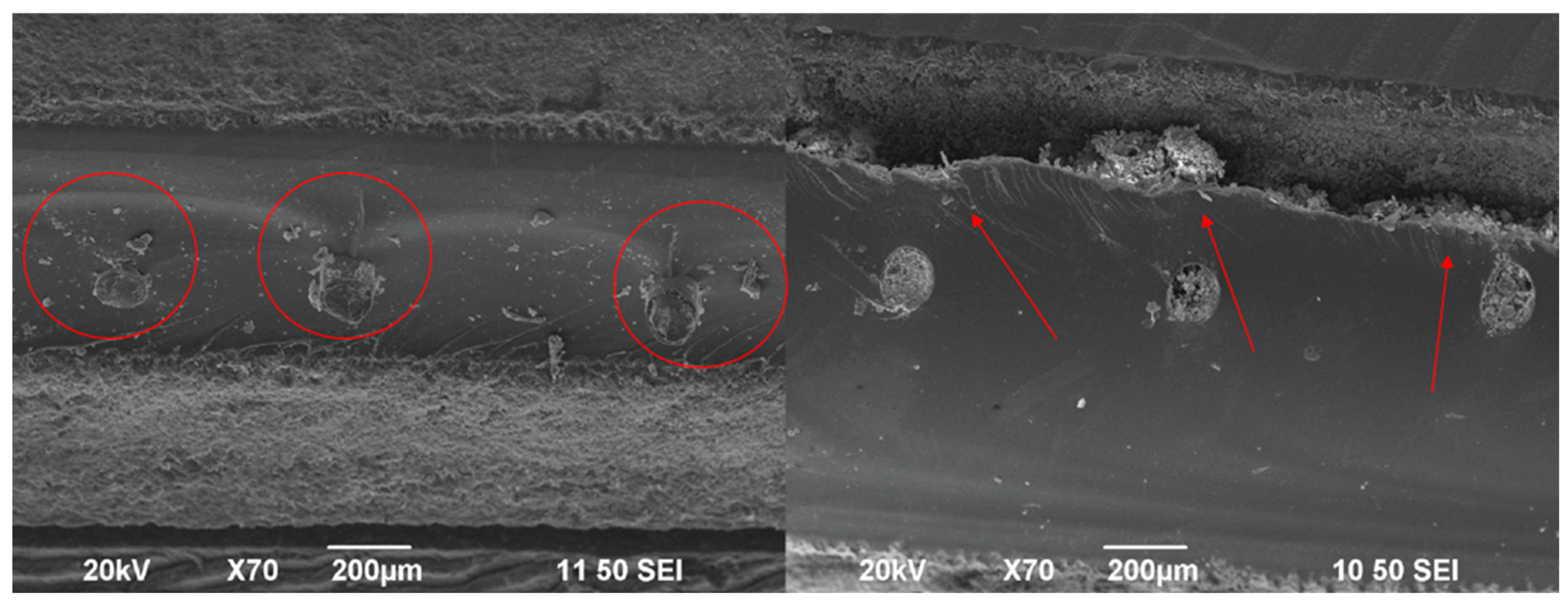

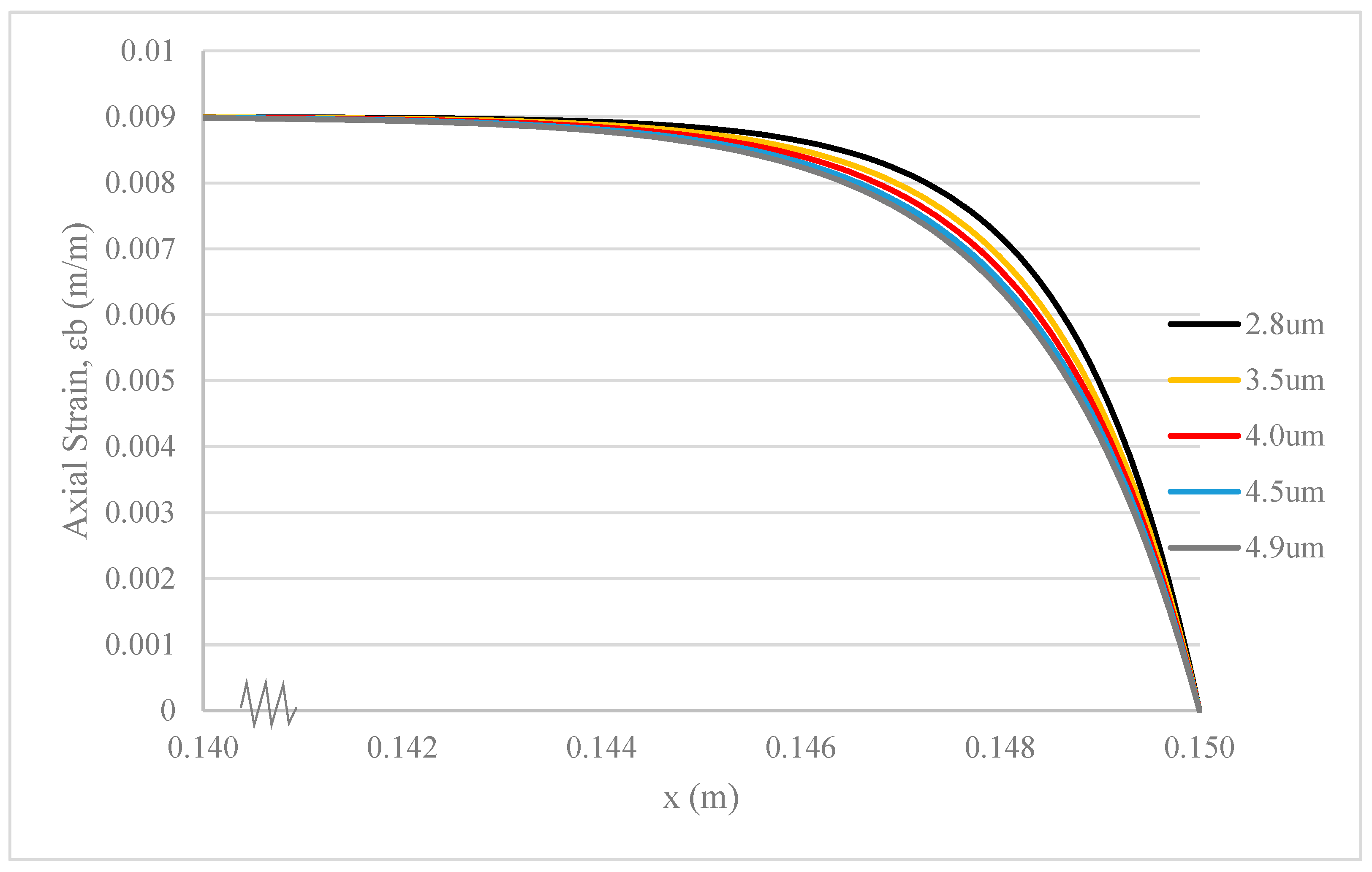

3.1. Content of ZnO Nanoparticles in the Core

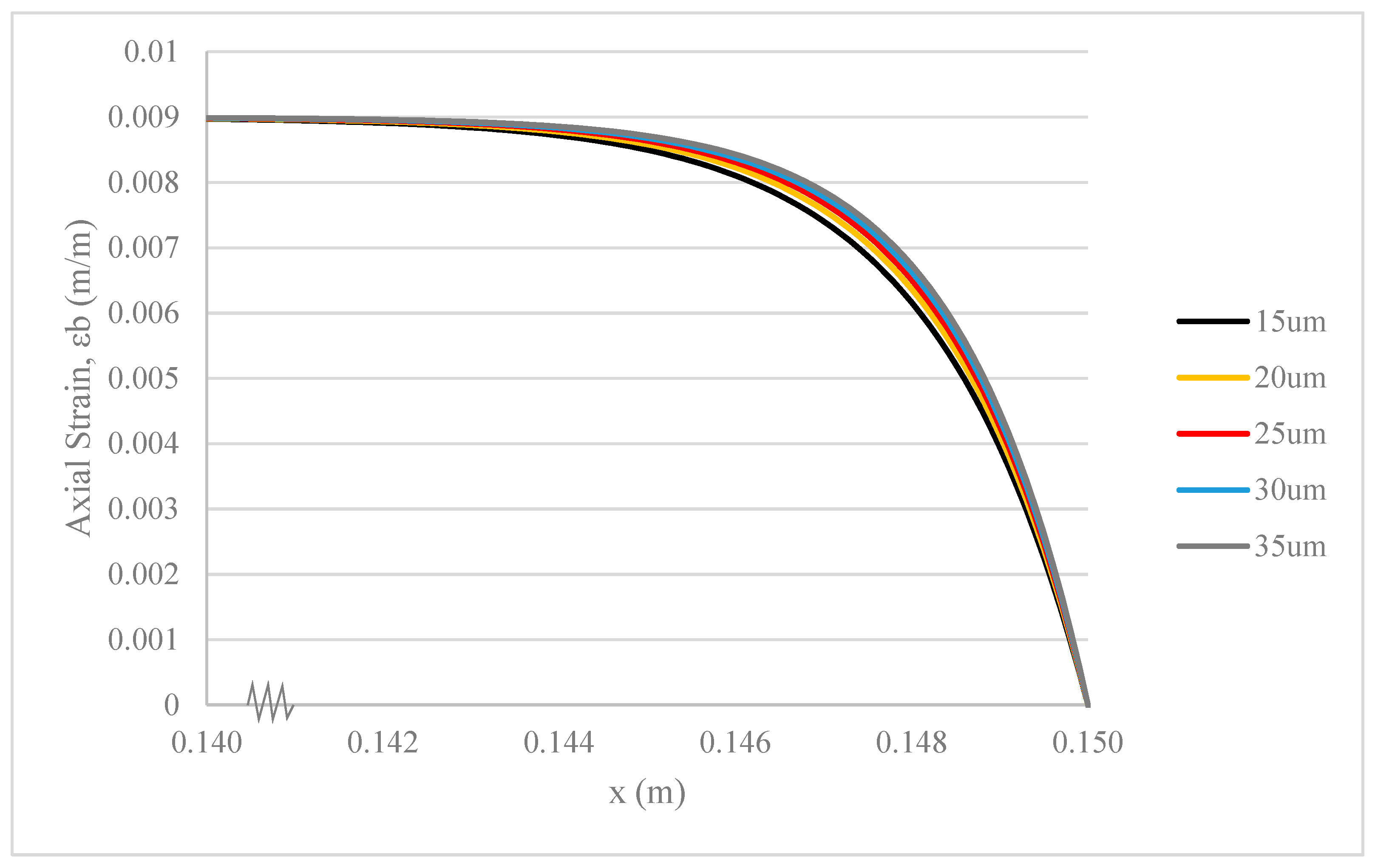

3.2. Hollowness of Hollow Glass Fibres

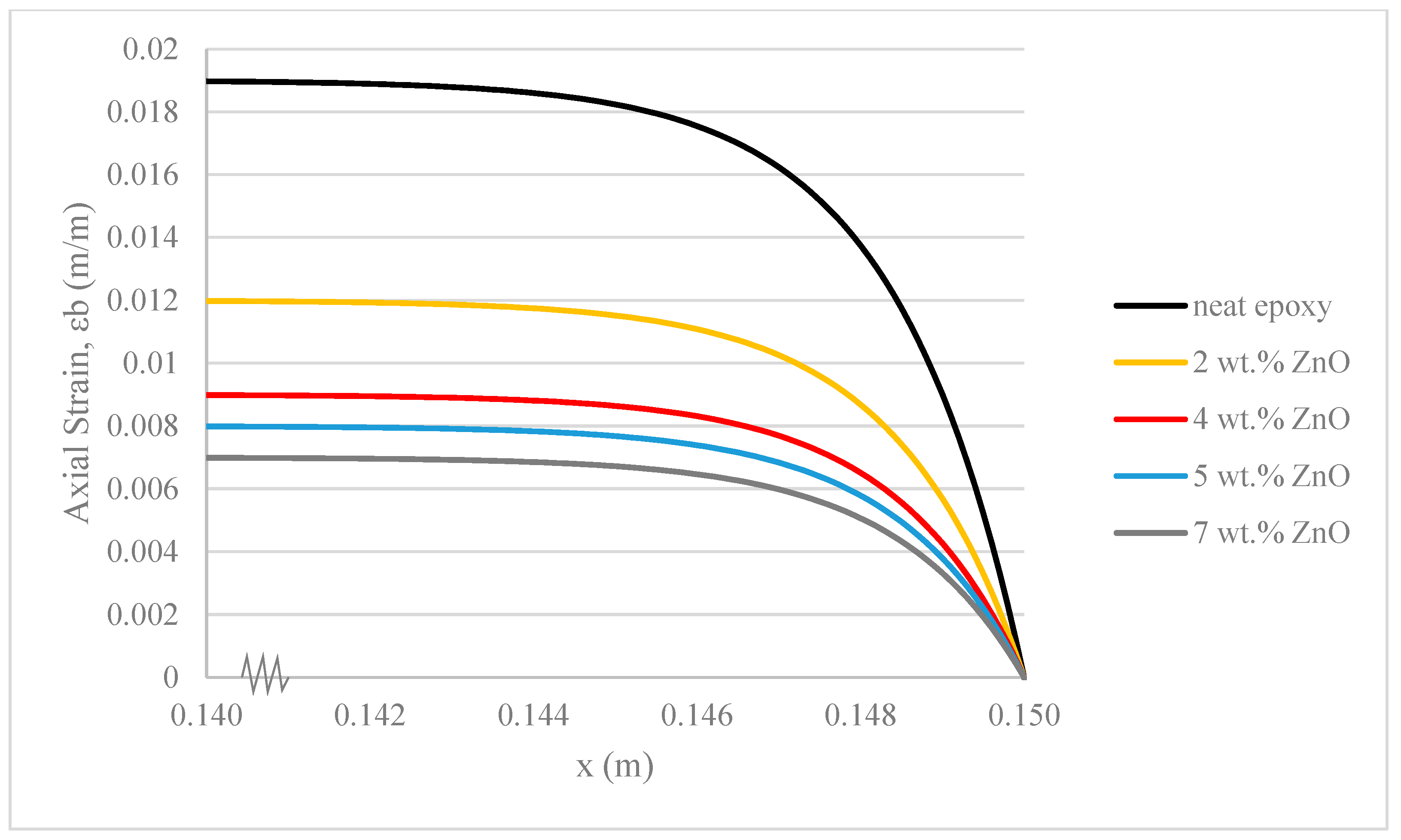

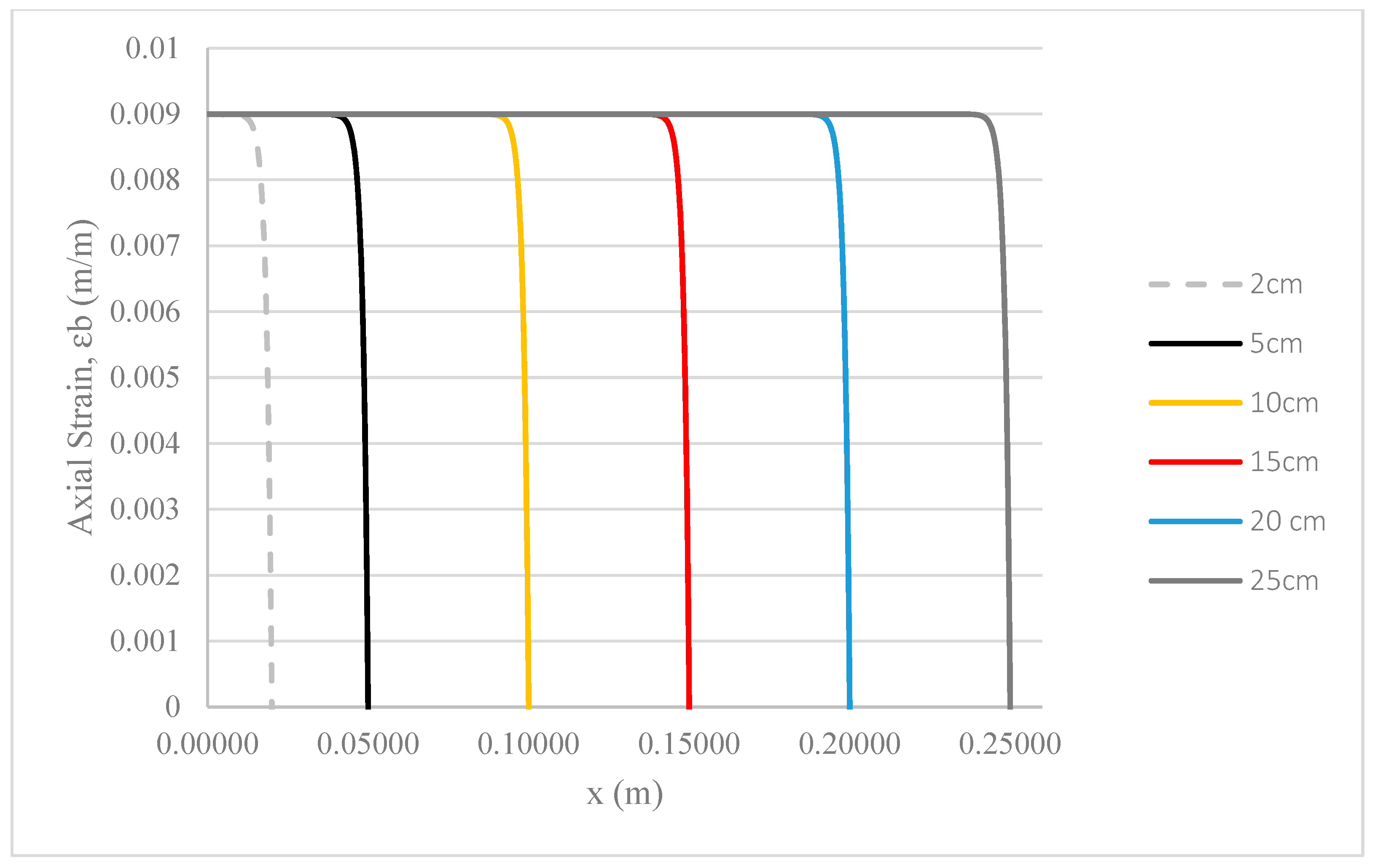

3.3. Length of Hollow Glass Fibres

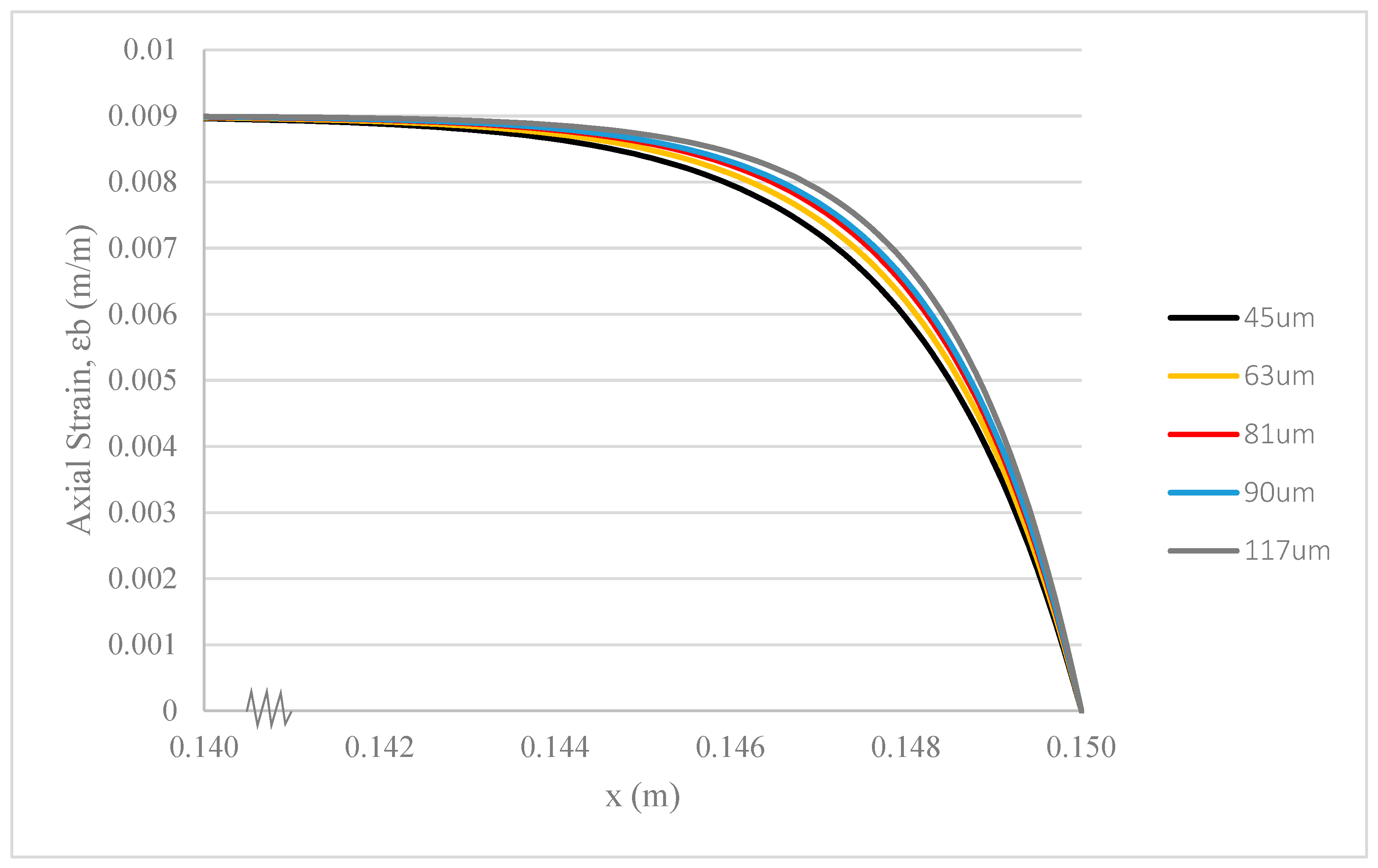

3.4. Thickness of Hollow Glass Fibres

3.5. Shear Strength of Adhesive Layer and Thickness of Adhesive Layer

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mostovoi, A.; Plakunova, E.; Panova, L. New Epoxy Composites Based on Potassium Polytitanates. Int. Polym. Sci. Technol. 2013, 40, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Solar UV Index: A Practical Guide; World Health Organization: Genea, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Environmental Effects of Ozone Depletion and Its Interactions with Climate Change: 2010 Assessment; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, S.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Sarkar, A.; Chakrabarti, M.; Sanyal, D.; Jana, D. Role of defects in tailoring structural, electrical and optical properties of ZnO. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2009, 54, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.P.; Depan, D.; Tomer, N.S.; Singh, R.P. Nanoscale particles for polymer degradation and stabilization trends and future perspectives. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2009, 34, 479–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.; Horie, M.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Turner, M.; Saunders, B. Aggregation of zinc oxide nanoparticles: From non-aqueous dispersions to composites used as photoactive layers in hybrid solar cells. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2010, 344, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, S.B.; Bhardwaj, V.K.; Singh, S.; Singh, A.; Kaur, N. Influence of surface modification by 2-aminothiophenol on optoelectronics properties of ZnO nanoparticles. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2014, 9, 877–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Jiu, T.; Tang, G.; Wang, G.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Fang, J. Solvents induced ZnO nanoparticles aggregation associated with their interfacial effect on organic solar cells. Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 18172–18179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; McNaughter, P.D.; Wang, Z.; Hodson, N.; Chen, M.; Cui, Z.; O’BRien, P.; Saunders, B.R. Controlled aggregation of quantum dot dispersions by added amine bilinkers and effects on hybrid polymer film properties. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 95512–95522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallakpour, S.; Madani, M. A review of current coupling agents for modification of metal oxide nanoparticles. Prog. Org. Coat. 2015, 86, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabek, J.F. Mechanisms of Photophysical Processes and Photochemical Reactions in Polymers: Theory and Applications; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1987; ISBN 0471911801. [Google Scholar]

- Awaja, F.; Nguyen, M.-T.; Zhang, S.; Arhatari, B. The investigation of inner structural damage of UV and heat degraded polymer composites using X-ray micro CT. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2011, 42, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, K.K. Composite Materials: Science and Engineering, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-387-74364-6. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, D.D.L. Composite Materials: Science and Applications, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-1-84882-830-8. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, E.J.; Lam, T.; Gorham, J.M.; Scott, K.C.; Long, C.J.; Stanley, D.; Sharma, R.; Liddle, J.A.; Pellegrin, B.; Nguyen, T. Methods to Assess the Impact of UV Irradiation on the Surface Chemistry and Structure of Multiwall Carbon Nanotube Epoxy Nanocomposites. Carbon 2014, 69, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlleben, W.; Vilar, G.; Fernandez-Rosas, E.; Gonzalez-Galvez, D.; Gabriel, C.; Hirth, S.; Frechen, T.; Stanley, D.; Gorham, J.; Sung, L.P.; et al. A Pilot Interlab Comparison of Methods to Simulate Aging of Nanocomposites and to Detect Fragments Released. Environ. Chem. 2014, 11, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlleben, W.; Brill, S.; Meier, M.W.; Mertler, M.; Cox, G.; Hirth, S.; von Vacano, B.; Strauss, V.; Treumann, S.; Wiench, K.; et al. On the Life Cycle of Nanocomposites: Comparing Released Fragments and Their In Vitro Hazards from Three Release Mechanisms and Four Nanocomposites. Small 2011, 7, 2384–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xie, M.Y.; Liu, L.Q.; Li, J.Z.; Kuang, J.; Ma, W.J.; Zhou, W.Y.; Xie, S.S.; Zhang, Z. Effect of supra-molecular microstructures on the adhesion of SWCNT fibre/iPP interface. Polymer 2013, 54, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppenstall-Butler, M.; Bannister, D.; Young, R. A study of transcrystalline polypropylene/ single-aramid-fibre pull-out behaviour using Raman spectroscopy. Compos. Part A 1996, 27A, 833–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyanagi, J.; Nakatani, H.; Ogihara, S. Comparison of glass-epoxy interface strengths examined by cruciform specimen and single-fiber pull-out tests under combined stress state. Compos. Part A 2012, 43, 1819–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyniuk, K.; Sørensen, B.F.; Modregger, P.; Lauridsen, E.M. 3D in situ observations of glass fibre/matrix interfacial debonding. Compos. Part A 2013, 55, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüller, T.; Beckert, W.; Lauke, B.; Ageorges, C.; Friedrich, K. Single fibre transverse debonding: Stress analysis of the Broutman test. Compos. Part A 2000, 31, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, J.; Yang, L. Temperature dependence of the interfacial shear strength in glass-fibre epoxy composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2014, 96, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.M.; Okabe, T.; Takeda, N. The estimation of statistical fibre strength by fragmentation tests of single-fibre composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2000, 60, 1965–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luethi, B.; Reber, R.; Mayer, J.; Wintermantel, E.; Janczak-Rusch, J.; Rohr, L. An energy-based analytical push-out model applied to characterize the interfacial properties of knitted glass fibre reinforced PET. Compos. Part A 1998, 29A, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Thomason, J. Interface strength in glass fibre-polypropylene measured using the fibre pull-out and microbond methods. Compos. Part A 2010, 41, 1077–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodowsky, H.M.; Jenschke, W.; Mader, E. Characterization of interphase properties: Microfatigue of single fibre model composites. Compos. Part A 2010, 41, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, B.; He, X.; Huang, Y.; Hwang, K. Failure analysis and the optimal toughness design of carbon nanotube-reinforced composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2010, 70, 1360–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFrancia, C.; Ward, T.C.; Claus, R.O. The single-fibre pull-out test. 1: Review and interpretation. Compos. Part A 1996, 27A, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFrancia, C.; Ward, T.C.; Claus, R.O. The single-fibre pull-out test. 2: Quantitative evaluation of an uncatalysed TGDDM/DDS epoxy cure study. Compos. Part A 1996, 27A, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-F.; Kagawa, Y. The energy release rate for an interfacial debond crack in a fiber pull-out model. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2000, 60, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.D.; Ajayan, P.; Schulte, K. Nanocomposite toughness from a pull-out mechanism. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2013, 83, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, D.; Andrews, M.; Cervenka, A.; Young, R. Analysis of the single-fibre pull-out test by means of Raman spectroscopy: Part II. Micromechanics of deformation for an aramid/epoxy system. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1995, 53, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.-Y.; Yue, C.-Y.; Hu, X.; Mai, Y.-W. Analyses of the micromechanics of stress transfer in single- and multi-fiber pull-out tests. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2000, 60, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, J.A. On the use of shear-lag methods for analysis of stress transfer in unidirectional composites. Mech. Mater. 1997, 26, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. A new model for the energy release rate of fibre/matrix interfacial fracture. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1998, 58, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, H.Y.; Mai, Y.W.; Diao, X.X. On steady-state fibre pull-out I The stress field. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1999, 59, 2179–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Baillie, C.; Mai, Y.W. Interfacial debonding and fibre pull-out stresses Part I Critical comparison of existing theories with experiments. J. Mater. Sci. 1991, 27, 3143–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senses, E.; Kitchens, C.L.; Faraone, A. Viscosity reduction in polymer nanocomposites: Insights from dynamic neutron and X-ray scattering. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 60, 1130–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kröger, M.; Liu, W.K. Nanoparticle effect on the dynamics of polymer chains and their entanglement network. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 118001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyromali, C.; Patelis, N.; Cutrano, M.; Gosika, M.; Glynos, E.; Moreno, A.J.; Sakellariou, G.; Smrek, J.; Vlassopoulos, D. Nonmonotonic composition dependence of viscosity upon adding single-chain nanoparticles to entangled polymers. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 4826–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.H.; Wang, G.L.; Zhang, M. Characterization of mechanical properties of epoxy resin reinforced with submicron-sized ZnO prepared via in situ synthesis method. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 3986–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Hong, S.I.; Kim, S.J. On the rule of mixtures for predicting the mechanical properties of composites with homogeneously distributed soft and hard particles. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 112, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, D.; Prolongo, S.; González-Benito, J. Thermo-mechanical properties of polysulfone based nanocomposites with well dispersed silica nanoparticles. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 61, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Pascual, A.M.; Xu, C.P.; Luque, R. Development and characterization of novel poly (ether ether ketone)/ZnO bionanocomposites. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 3065–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hata, E.; Tomita, Y. Order-of-magnitude polymerization-shrinkage suppression of volume gratings recorded in nanoparticle-polymer composites. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak, M.; Szalińska, H. Reducing the shrinkage and setting dose in polyester resins by addition of metal oxides. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 1984, 23, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Wang, J.; Tian, J.; Xu, X.; Dai, J.; Wang, X. Preparation and characterization of TiO2/ZnO composite coating on carbon steel surface and its anticorrosive behaviour in seawater. Compos. Part B 2013, 46, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-K.; Sham, M.-L.; Wu, J. Nanoscale characterization of interphase in silane treated glass fibre composites. Compos. Part A 2001, 32, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Maekawa, Z.; Hamada, H.; Kibune, M.; Hojo, M.; Ikuta, N. Influence of adsorption behaviour of a silane coupling agent on interlaminar fracture in glass fibre fabric-reinforced unsaturated polyester laminates. J. Mater. Sci. 1992, 27, 6782–6790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements | Symbols | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Geometry | ||

| Epoxy base | 208 μm | |

| Adhesive layer | 158 μm | |

| HGF | 149 μm | |

| Adhesive layer | 99 μm | |

| ZnO/epoxy core | 90 μm | |

| Young’s Modulus | ||

| Epoxy | 3 GPa | |

| HGF | 68.5 GPa | |

| Adhesive layer | 3.3 GPa | |

| ZnO | 111.2 GPa | |

| Adhesive Layers | ||

| Adhesive layer | 1.2 GPa | |

| Thickness of adhesive layer | 4.5 μm | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wong, T.T.; Amigues, S.; Awaja, F. The Influence of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Dispersion, Rheology, and Mechanical Properties of Epoxy-Based Composites. Polymers 2025, 17, 3253. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243253

Wong TT, Amigues S, Awaja F. The Influence of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Dispersion, Rheology, and Mechanical Properties of Epoxy-Based Composites. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3253. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243253

Chicago/Turabian StyleWong, Tsz Ting, Solange Amigues, and Firas Awaja. 2025. "The Influence of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Dispersion, Rheology, and Mechanical Properties of Epoxy-Based Composites" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3253. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243253

APA StyleWong, T. T., Amigues, S., & Awaja, F. (2025). The Influence of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Dispersion, Rheology, and Mechanical Properties of Epoxy-Based Composites. Polymers, 17(24), 3253. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243253