1. Introduction

Radiation shielding is a cornerstone of radiation safety in healthcare, nuclear engineering, and industrial applications, serving to protect humans and equipment from harmful ionizing radiation. The demand for effective shielding materials is particularly high in medical imaging and radiotherapy facilities, nuclear reactors, waste storage systems, and non-destructive testing environments. Traditional shielding materials such as lead, tungsten, and concrete have long been favored due to their high density and strong photon attenuation capabilities [

1,

2,

3]. However, these materials present significant drawbacks. Lead is toxic, brittle, and environmentally hazardous, while concrete is heavy, prone to cracking, and difficult to recycle or reuse. These limitations have motivated extensive research toward developing alternative materials that are lighter, safer, and more sustainable.

Polymers have emerged as promising matrices for radiation-shielding composites owing to their low cost, ease of fabrication, and design flexibility. Materials such as high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and polylactic acid (PLA) are widely used in radiation-shielding studies as reference polymers, where they serve as convenient model matrices for evaluating the influence of different fillers on photon attenuation performance [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Although HDPE and PLA are not considered radiation-resistant polymers for long-term structural applications, they are commonly employed as baseline systems in computational studies because they allow the effect of filler composition, loading fraction, and photon-interaction physics to be isolated without the complexity of advanced high-performance polymers. For applications exposed to high accumulated radiation doses, the same zeolite formulations can in principle be transferred to more radiation-resistant aromatic or conjugated polymers such as polyimide [

12,

13]. In the present study, HDPE and PLA are therefore used strictly as model matrices for benchmarking photon attenuation and are not proposed as long-term structural shielding materials.

To overcome the intrinsic limitations of neat polymers, numerous studies have investigated composites enhanced with high-atomic-number (high-

Z) fillers such as bismuth oxide (Bi

2O

3), tungsten trioxide (WO

3), lead oxide (PbO), and barium sulfate (BaSO

4). Adding these fillers enhances photon attenuation properties and reduces the half-value layer by increasing the probability of photoelectric and Compton interactions [

14,

15,

16]. However, the widespread use of heavy-metal fillers presents new challenges, such as increased material weight and potential toxicity during both processing and disposal. As a result, there is growing interest in developing environmentally friendly, low-density, and cost-effective alternatives that deliver acceptable photon shielding without relying solely on toxic or very-high-density phases.

Among the potential candidates, natural zeolites, which are microporous aluminosilicate minerals, have emerged as a promising yet comparatively underexplored option for this purpose. They are naturally abundant, chemically stable, and inexpensive, making them attractive for sustainable radiation shielding applications. Zeolites are environmentally benign and can be readily incorporated into polymer matrices to produce lightweight composites with improved radiation attenuation [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Several studies have shown that zeolites possess mass attenuation coefficients (

) comparable to those of clays and soils and only slightly lower than those of conventional concrete, confirming their potential as sustainable shielding fillers. Further investigations have also demonstrated the successful integration of natural zeolites into polymeric and cementitious materials, achieving enhanced

-ray attenuation while maintaining good environmental performance [

19,

20].

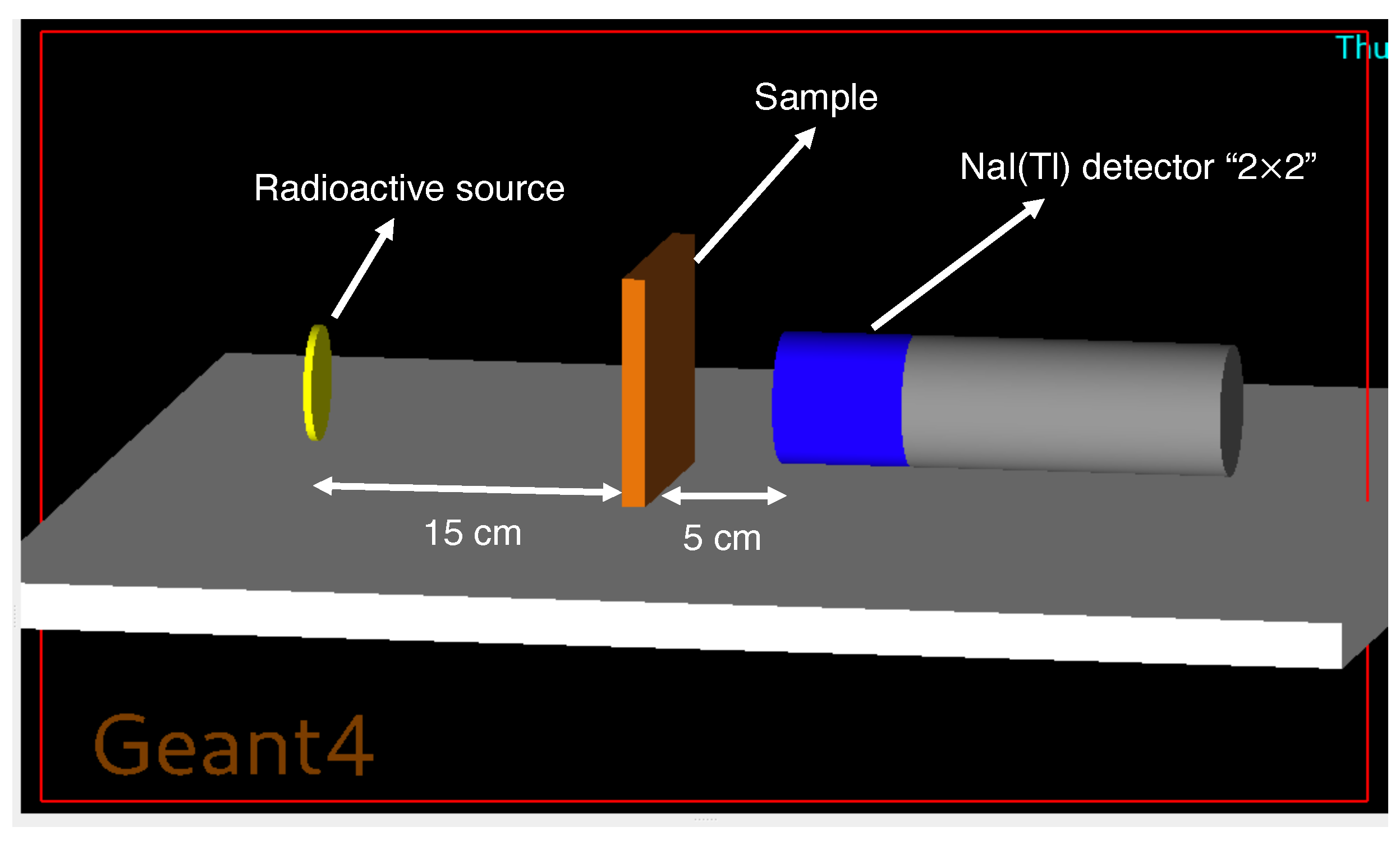

In this context, zeolite–polymer composites are proposed as sustainable, lightweight alternatives to conventional heavy-metal-based shielding systems. This work investigates how zeolite loading (10–40 wt%) modifies the photon-interaction behavior of HDPE and PLA matrices and benchmarks their performance against standard shielding materials. Using the Phy-X/PSD platform, photon attenuation metrics such as the mass and linear attenuation coefficients, half-value layer (HVL), mean free path (MFP), and effective atomic number () are computed over 15 keV–15 MeV and cross-checked against a dedicated GEANT4 Monte Carlo transmission model. Finally, the simulated performance of the zeolite–polymer composites is compared with representative lead-, steel-, and concrete-based shields reported in the literature to clarify the niche where such lightweight, lead-free systems can offer a meaningful balance between attenuation efficiency, mass, and environmental impact.

3. Materials

The oxide composition of the zeolite used in this study was taken from Gili and Hila [

20], whose measurements provide representative mass fractions of SiO

2, Al

2O

3, K

2O, Na

2O, CaO, and MgO for natural clinoptilolite. Similar oxide compositions for natural zeolites have been reported in other studies [

18,

19].

Table 1 summarizes the oxide fractions used in this work. These oxide fractions were subsequently converted into elemental mass fractions for input into both Phy-X/PSD and GEANT4. Because the work was carried out entirely through simulations, no laboratory materials or equipment were used, and therefore supplier details are not relevant.

The computational modeling approach used high-density polyethylene (HDPE) as the foundational polymer matrix, reinforced with clinoptilolite zeolite at loadings of 10–40 wt%. Two reference systems were included for baseline comparison: pure HDPE (100 wt%) and pure zeolite (100 wt%). Composite densities were estimated using the standard mixture rule for multiphase systems [

26]:

where

is the density of the mixture,

is the weight fraction of component

i, and

is the density of component

i. In this study,

g cm

−3,

g cm

−3, and

g cm

−3.

Table 2 lists the densities used in GEANT4 for the investigated HDPE–zeolite and PLA–zeolite systems.

5. Results and Discussion

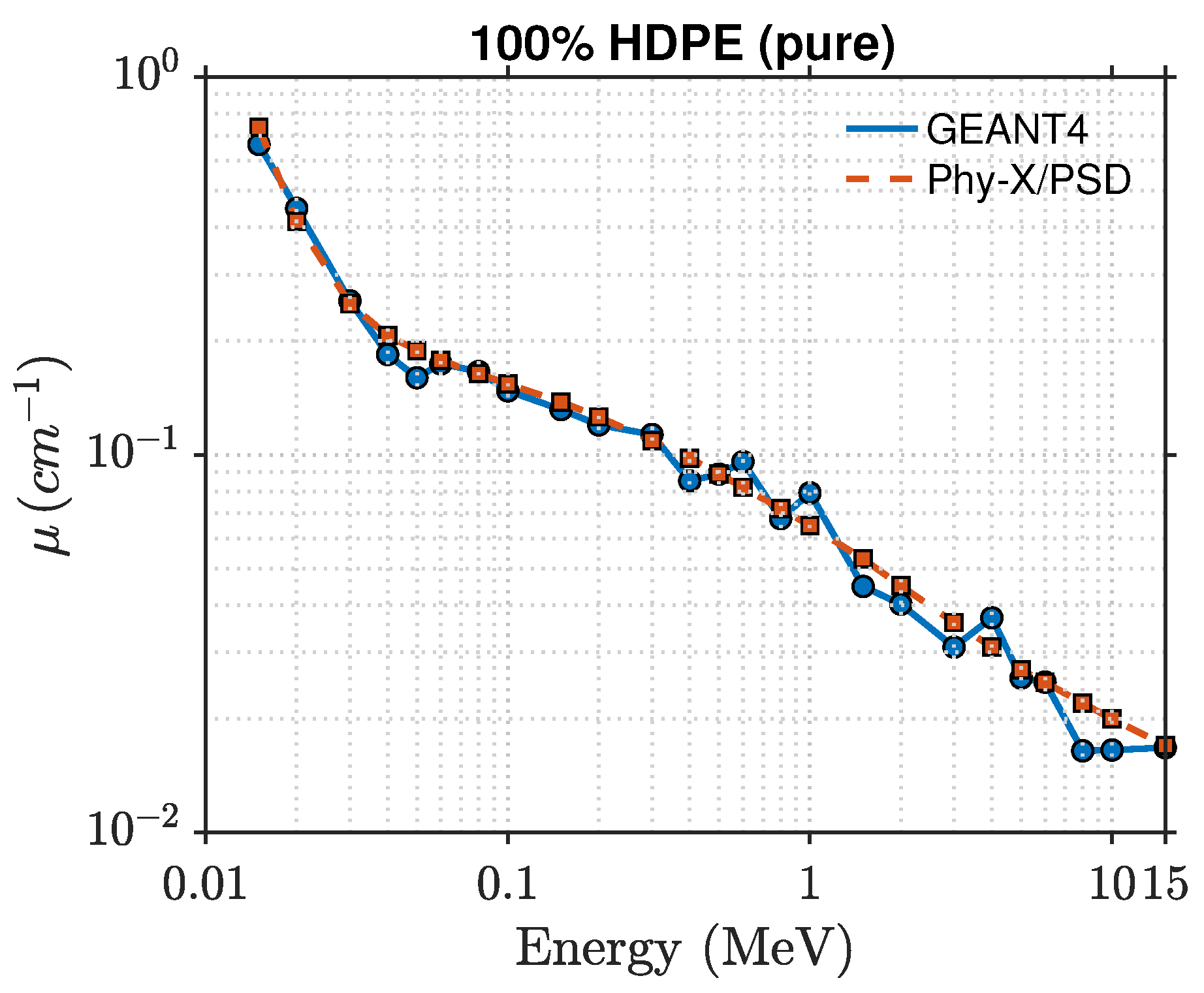

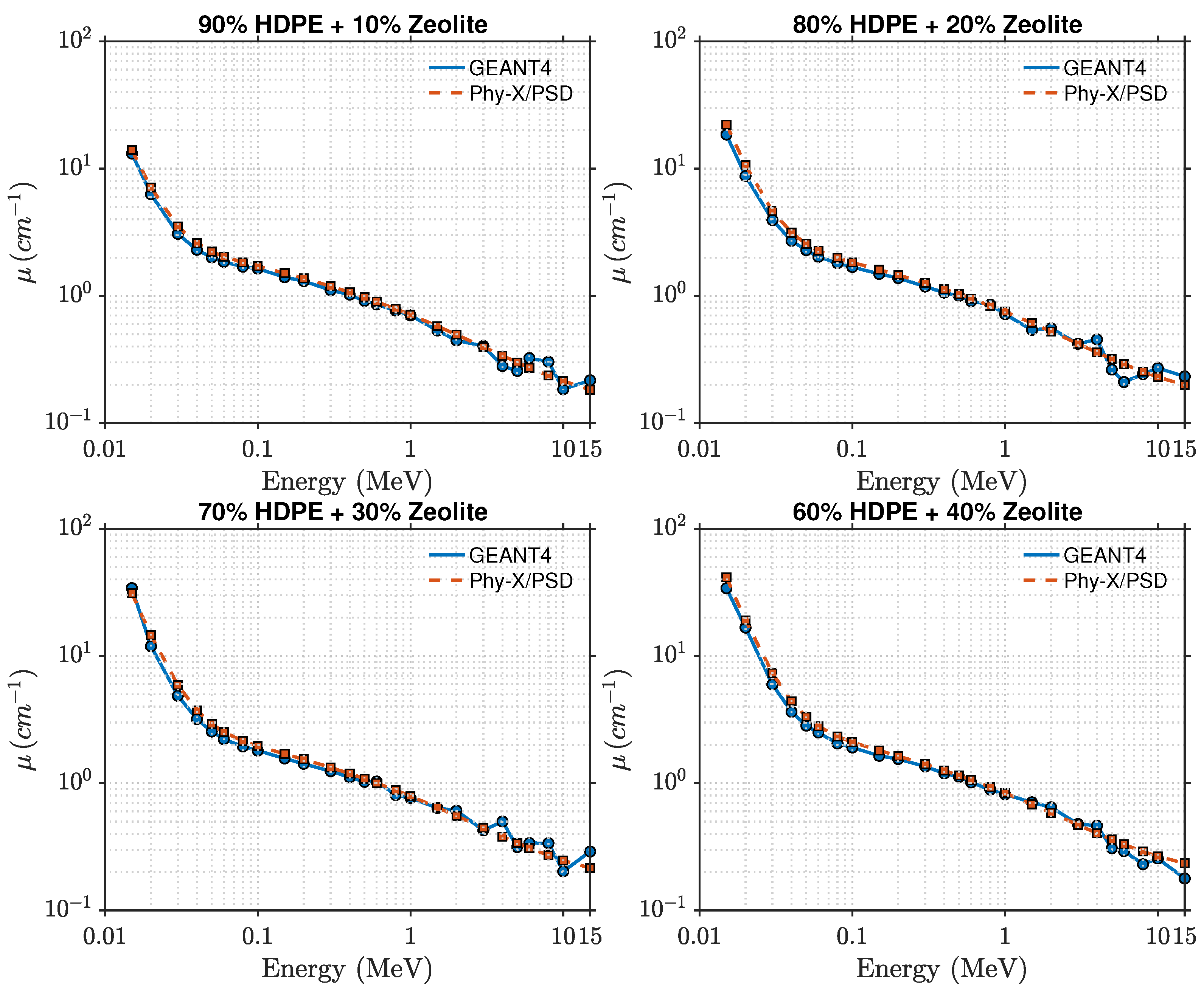

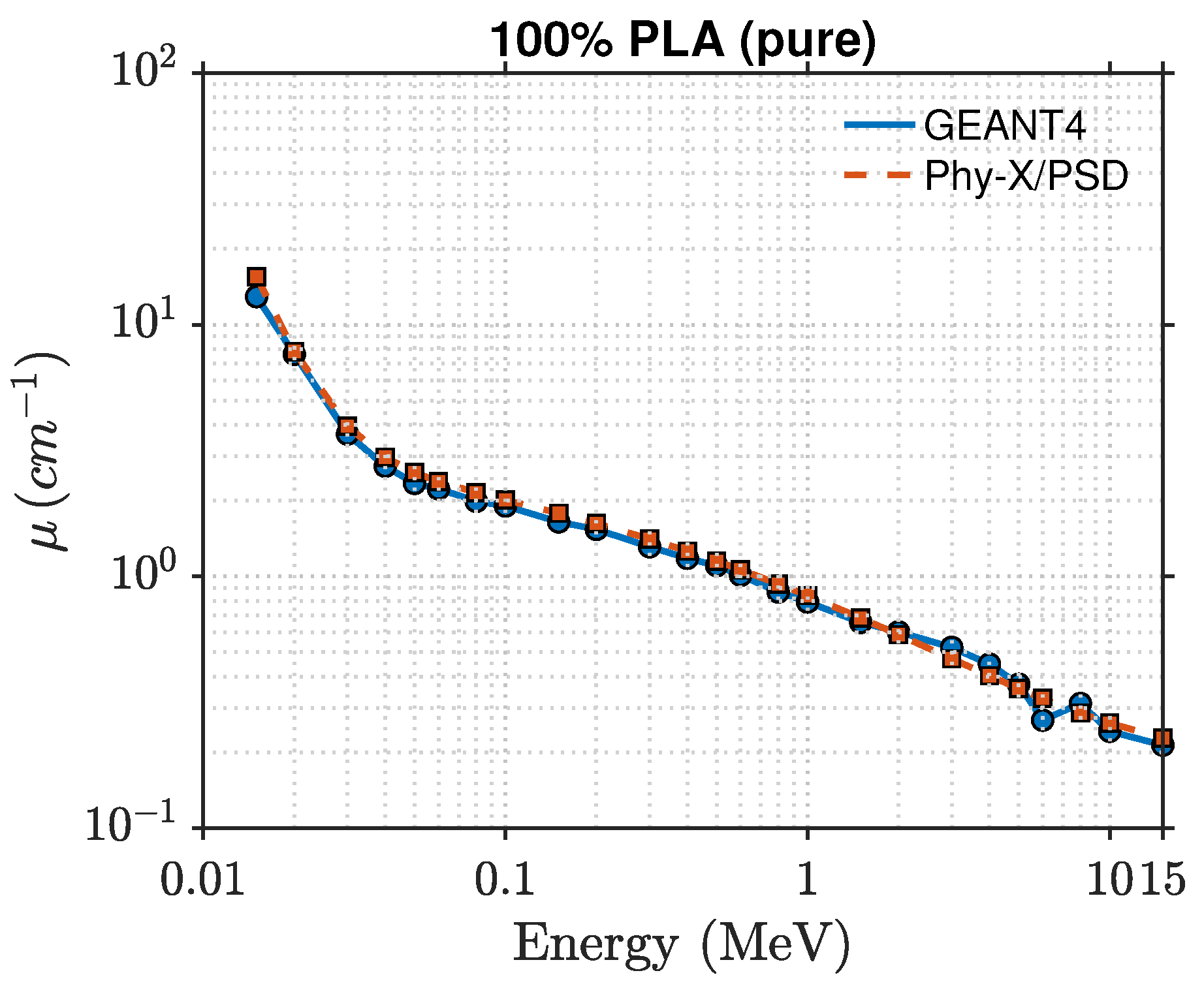

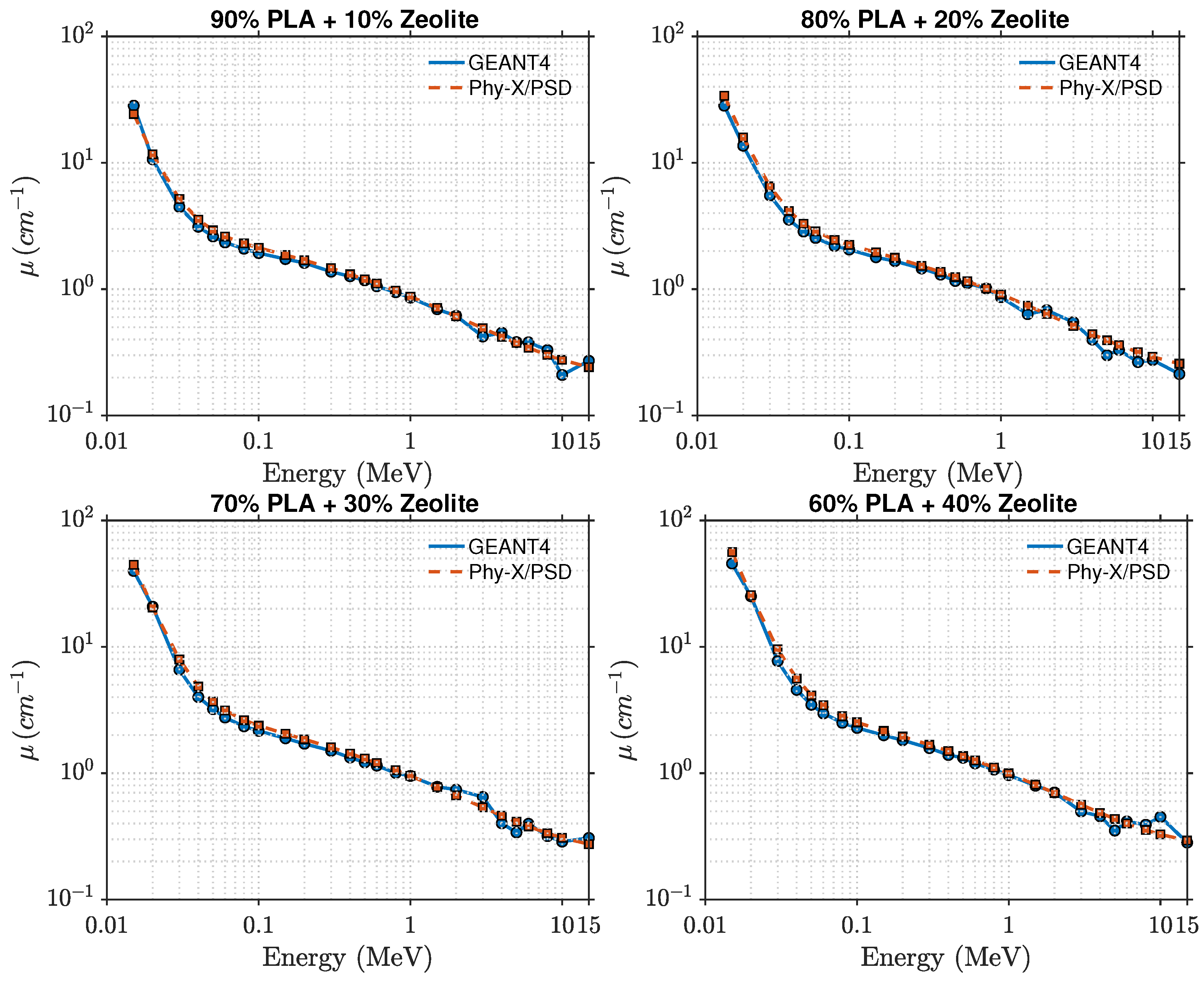

This section presents the photon attenuation characteristics of HDPE- and PLA-based composites reinforced with zeolite at different loadings (0, 10, 20, 30, and 40 wt%). The key parameters include the linear attenuation coefficient (), mass attenuation coefficient (/), half-value layer (HVL), mean free path (), and effective atomic number (), evaluated across photon energies from 15 keV to 15 MeV using both Phy-X/PSD and GEANT4 simulations. The comparison between the two computational approaches revealed excellent agreement, with discrepancies typically below 2%, validating both the physics models and geometry configurations used.

5.1. Gamma Shielding Properties of HDPE–Zeolite Composites

The photon attenuation behavior of pure HDPE and HDPE–zeolite composites is shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. As expected, the linear attenuation coefficient (

) decreases with increasing photon energy, reflecting the transition from photoelectric absorption at low energies to Compton scattering in the intermediate range. At 15 keV,

increases from approximately

for pure HDPE to about

for the 40 wt% zeolite composite, indicating a strong enhancement in photon absorption. The intermediate compositions exhibit a consistent trend, confirming the progressive improvement in attenuation with higher zeolite loading. When the photon energy exceeds about 0.1 MeV,

decreases rapidly for all compositions. In the MeV region, the attenuation curves converge, consistent with the dominance of Compton scattering, though slight composition-dependent differences remain. For instance, at 1 MeV, the 40 wt% composite maintains a marginally higher

value than pure HDPE, while above 10 MeV, pair production begins to contribute slightly.

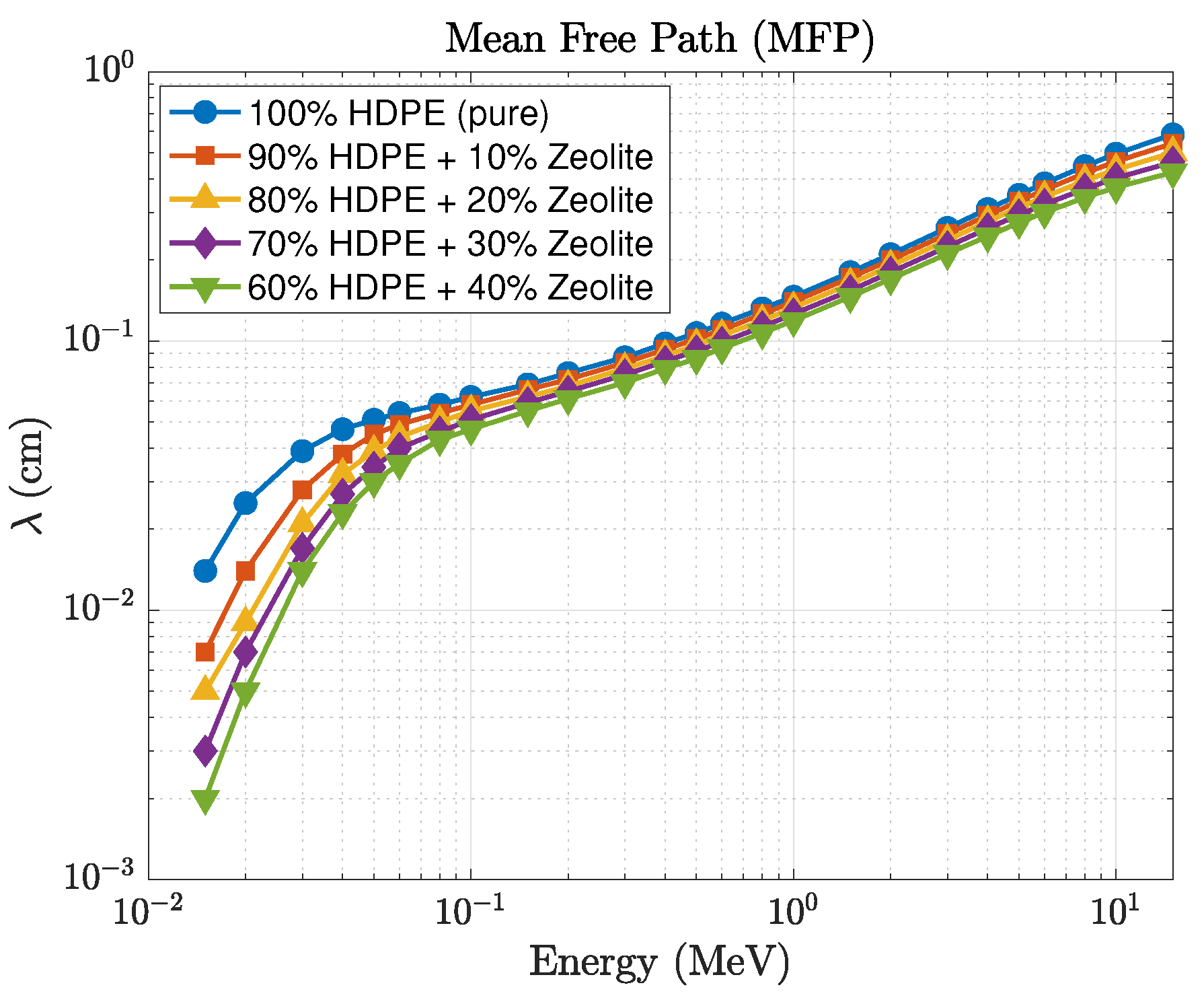

The comparison between the GEANT4-simulated and Phy-X/PSD-calculated values of the linear attenuation coefficient (

) shows very close agreement, with relative deviations remaining within about 2% across all photon energies and compositions. This consistency confirms that the photon cross-section data implemented in Phy-X/PSD are well reproduced by the transport physics models in GEANT4. It also indicates that the material definitions and energy-sampling procedures used in the simulations were accurately established. The observed improvement in shielding performance is directly linked to the increase in

, while the corresponding mean free path decreases proportionally, as illustrated in

Figure 4. At 0.1 MeV, for example, pure HDPE exhibits

, corresponding to

cm and

cm, while the 40 wt% composite achieves

,

cm, and

cm. These values clearly demonstrate that higher zeolite concentrations lead to shorter penetration depths and better photon attenuation. The effective atomic number (

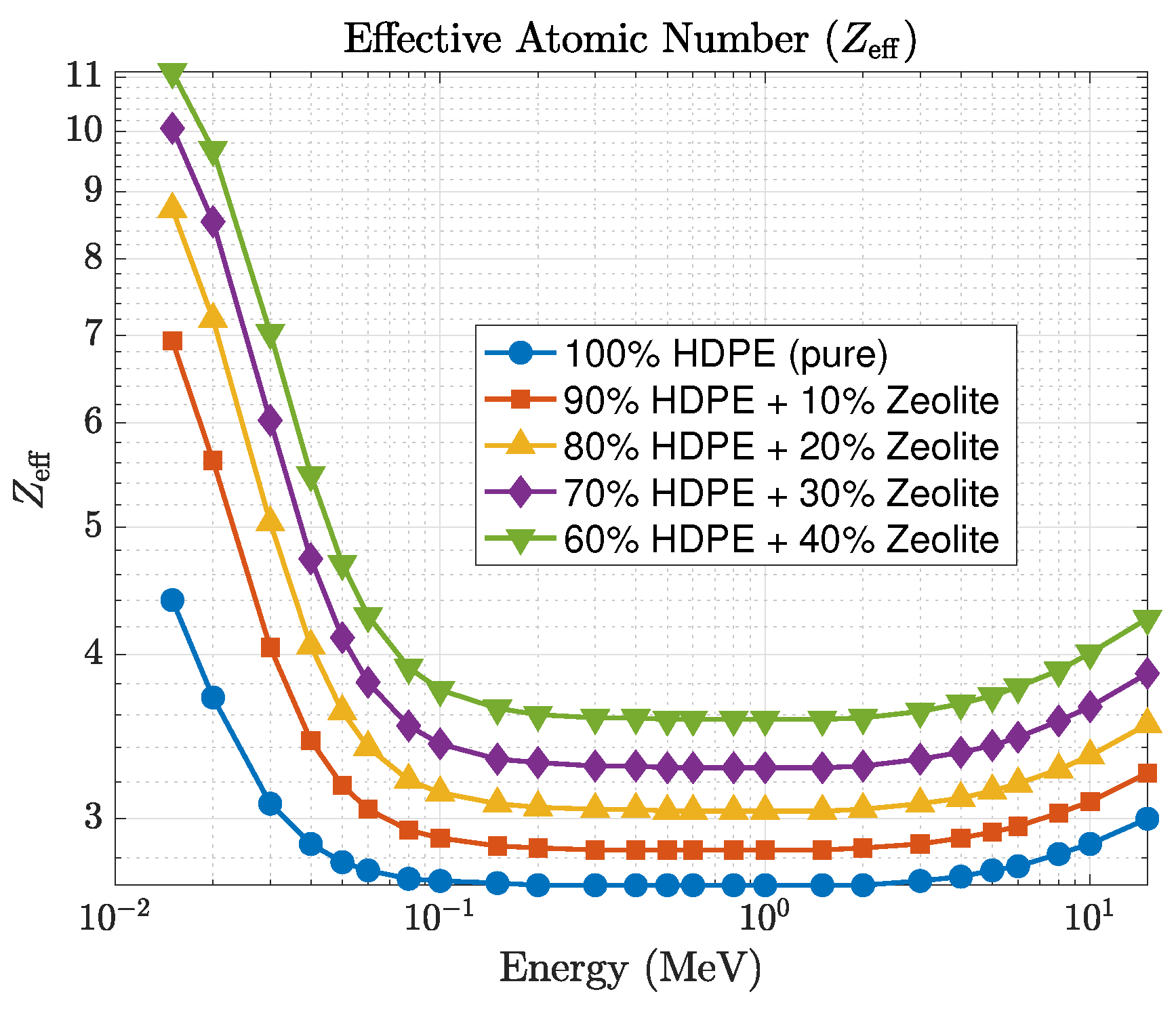

), presented in

Figure 5, also follows the expected dependence on energy and composition. For pure HDPE,

remains nearly constant around 2.7, increasing gradually to about 3.8 for the 40 wt% composite. This increase directly contributes to the enhanced low-energy absorption, where photoelectric interactions are highly sensitive to atomic number.

5.2. Gamma Shielding Properties of PLA–Zeolite Composites

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 illustrate the photon attenuation characteristics of the PLA–zeolite composites. Because of its higher intrinsic density (1.25 g cm

−3) and oxygen-rich molecular structure, PLA shows larger attenuation coefficients than HDPE across the examined energy range.

At 15 keV, the linear attenuation coefficient () increases from roughly for pure PLA to about for the 40 wt% composite, revealing a clear improvement in low-energy photon absorption as the zeolite content increases. As the photon energy increases, the linear attenuation coefficient () drops rapidly. This behavior arises from the reduced contribution of the photoelectric effect and the growing dominance of Compton scattering above approximately 0.1 MeV. Beyond 1 MeV, the attenuation curves for all compositions begin to overlap, indicating that attenuation in this energy range becomes largely independent of composition.

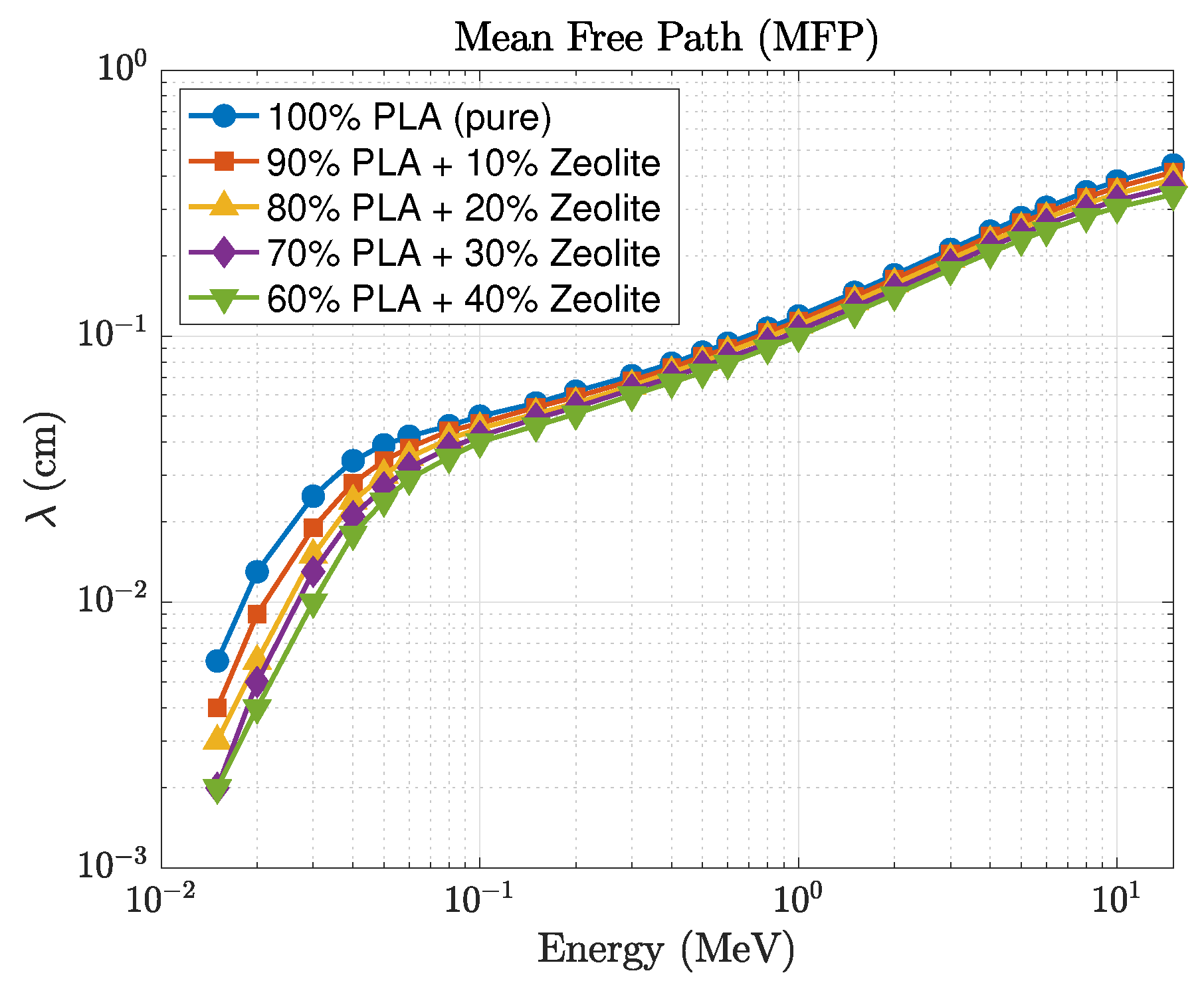

A comparison between the GEANT4 and Phy-X/PSD datasets shows strong consistency, with relative deviations remaining within about 2% across the full energy range and all filler concentrations. This agreement highlights the reliability of both computational approaches and the accuracy of the material definitions employed in the simulations. The mean free path, shown in

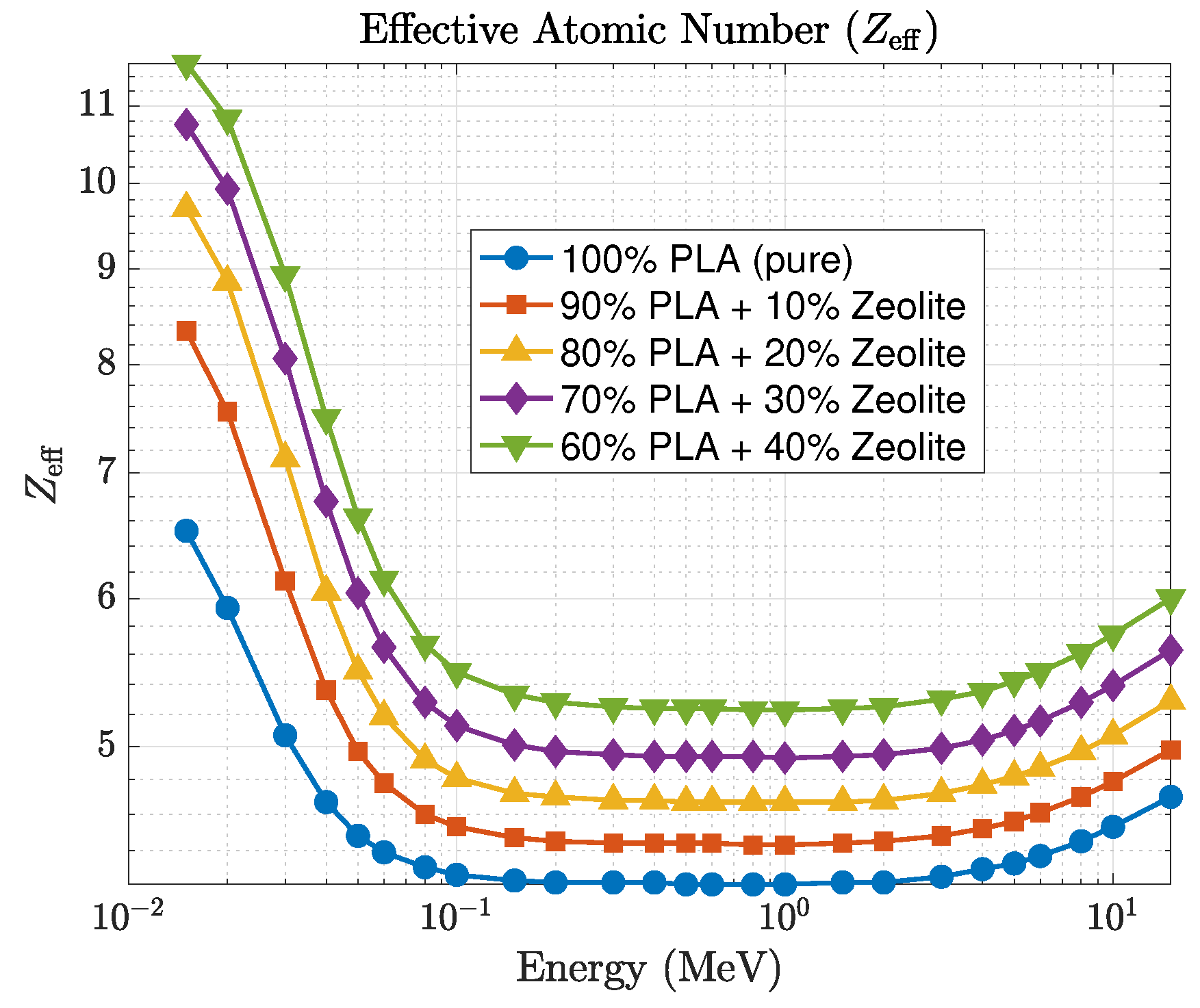

Figure 8, and half-value layer decrease systematically with increasing zeolite loading, consistent with the enhanced linear attenuation coefficient. This trend confirms that higher zeolite concentrations reduce photon penetration depth and improve shielding performance. The effective atomic number, shown in

Figure 9, varies systematically with both photon energy and composition. At lower photon energies (15–50 keV),

rises from about 6.5 for pure PLA to nearly 11.6 for the 40 wt% composite. This increase reflects the presence of higher atomic number elements such as silicon, aluminum, and iron in the zeolite framework. When the photon energy exceeds roughly 0.3 MeV,

stabilizes around 5–6, a region dominated by Compton scattering where attenuation becomes largely insensitive to atomic number. These findings indicate that PLA–zeolite composites provide stronger photon attenuation than their HDPE-based counterparts, primarily due to their greater density and higher effective atomic number. These attributes make them excellent candidates for lightweight, durable, and environmentally friendly radiation-shielding applications in both structural and protective components.

The increase in attenuation with higher zeolite loading can be traced directly to the mineral’s oxide composition. Small amounts of Fe2O3 (Fe) and CaO (Ca) play an outsized role in raising the effective atomic number, especially at low photon energies where the photoelectric effect dominates. The major oxides SiO2 and Al2O3 mainly contribute by increasing the overall density and providing a moderate boost to . Meanwhile, alkali oxides such as K2O and Na2O add to the low-energy response because of their relatively higher atomic numbers. Taken together, this composition explains the upward trend in and with increasing zeolite content, showing that the improvement arises not only from higher density but also from the specific elemental makeup of the zeolite.

5.3. Practical Considerations for Composite Fabrication

In practical processing of zeolite–polymer composites, several material and manufacturing considerations accompany the improvements in photon attenuation. First, uniform dispersion of the zeolite is required to avoid particle agglomeration, which can reduce mechanical strength; previous studies show that micron-scale zeolite powders can be homogeneously mixed into polymers up to 30–40 wt% using melt compounding or twin-screw extrusion [

19,

26]. At 40 wt% loading, however, a noticeable increase in melt viscosity is expected, particularly for HDPE, which may require higher processing temperatures or reduced molding speeds. PLA, by contrast, is more susceptible to thermal and hydrolytic degradation during extended residence times, and processing conditions must therefore be carefully controlled.

High inorganic loadings also influence mechanical behavior. Previous studies on mineral-filled polymers reports that stiffness generally increases while elongation at break and impact resistance decrease at filler contents above 20–30 wt% [

17]. For this reason, the HDPE– and PLA–zeolite systems investigated here are used as model matrices for benchmarking photon attenuation rather than as optimized structural materials. In practical, long-term shielding applications, the same zeolite formulations could be transferred to radiation-resistant engineering polymers such as polyimides [

12,

13], which better withstand accumulated dose and thermal cycling.

5.4. Comparative Assessment

The results show that both HDPE– and PLA–zeolite composites exhibit a clear and progressive enhancement in photon attenuation with increasing zeolite concentration. The addition of zeolite increases the linear attenuation coefficient, reduces the mean free path, and raises the effective atomic number, reflecting the influence of high-Z oxide constituents that strengthen photon interactions, particularly at low and intermediate photon energies. Between the two polymer matrices, PLA-based composites consistently achieve higher values of and . This improvement arises from PLA’s higher intrinsic density (1.25 g cm−3) and its oxygen-rich molecular structure, both of which promote stronger photoelectric absorption. HDPE-based composites show slightly lower photon attenuation but remain attractive for applications where mechanical flexibility, low weight, and ease of processing are required. Accordingly, PLA–zeolite systems are well suited for applications requiring enhanced -ray attenuation, while HDPE–zeolite composites may be preferred in situations that prioritize structural flexibility and low mass. The close agreement between the GEANT4 and Phy-X/PSD datasets across all energies and compositions further confirms the reliability of both computational frameworks. These findings provide a solid basis for the continued development of lightweight, lead-free radiation-shielding materials for medical imaging, nuclear-safety infrastructure, and aerospace technologies.

5.5. Comparison with Conventional Shielding Materials

To place the simulated HDPE–zeolite and PLA–zeolite composites in context, their attenuation performance was compared with representative values for lead, structural steel, and ordinary Portland concrete at 662 keV, using tabulated NIST XCOM data and literature values reported in earlier studies [

1,

2,

3,

19,

20,

22].

Table 3 summarizes the typical linear attenuation coefficients and half-value layers (HVLs) for these reference materials. As expected, lead exhibits the highest attenuation (

), followed by structural steel (

) and Portland concrete (

), which is consistent with previously reported measurements for standard radiation-shielding materials [

1,

2,

22].

In comparison, the PLA–zeolite systems in this study achieve

at 40 wt% loading, while the HDPE–zeolite systems reach

, which is consistent with the lower effective atomic numbers of polymer-based composites. Although the zeolite–polymer composites do not match the attenuation performance of high-density metals, their HVLs (4.3–5.3 cm) are comparable to the range reported for lightweight concretes, polymer–cement mixtures, and zeolite–concrete composites [

1,

19,

20]. These results highlight the potential value of such composites in applications where low mass, lead-free composition, ease of fabrication, or environmental considerations are prioritized over maximum attenuation efficiency.

This comparison indicates that zeolite–polymer composites are not intended to replace lead or high-density concrete in high-flux environments but rather to complement existing shielding systems in scenarios requiring a balance between attenuation efficiency, mass, manufacturability, and environmental sustainability. This positioning is consistent with earlier studies on zeolite- and polymer-based shielding materials [

19,

20,

26] and highlights the niche where the proposed HDPE– and PLA–zeolite formulations can offer practical advantages.

6. Conclusions

This study comprehensively evaluated the photon attenuation characteristics of HDPE- and PLA-based composites reinforced with zeolite over the energy range of 15 keV–15 MeV using Phy-X/PSD calculations and GEANT4 Monte Carlo simulations. This work serves as a feasibility and benchmarking study, and long-term structural shielding applications will require transferring the same zeolite formulations to radiation-resistant polymers rather than HDPE or PLA. Excellent consistency between the two approaches, with deviations below 2%, confirmed the reliability of both the theoretical and transport-simulation methods. The linear attenuation coefficient () decreased with increasing photon energy, whereas the mean free path () increased, exhibiting the typical transition from photoelectric absorption at low energies to Compton scattering at intermediate energies. Incorporation of zeolite up to 40 wt% significantly enhanced attenuation capability for both matrices owing to the increased density and effective atomic number of the composites. At 15 keV, the half-value layer (HVL) decreased from 0.60 cm to 0.08 cm for HDPE and from 0.043 cm to 0.033 cm for PLA, reflecting the stronger photon-shielding performance of the PLA–zeolite system. The effective atomic number () increased from 2.7 to 4.3 for HDPE and from 6.5 to 11.6 for PLA with increasing zeolite loading, confirming the role of zeolite’s high-Z oxides in strengthening photon interactions. Between the two polymer matrices, PLA–zeolite composites exhibited superior photon attenuation across all energies, whereas HDPE–zeolite materials remain attractive for applications that prioritize low weight and ease of processing. Zeolite–polymer composites therefore represent lightweight, environmentally safe, and lead-free materials with promising potential for medical imaging, nuclear safety, and radiation-protection applications where efficient photon shielding is required.