Garlic-Derived S-allylcysteine Improves Functional Recovery and Neurotrophin Signaling After Brain Ischemia in Female Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

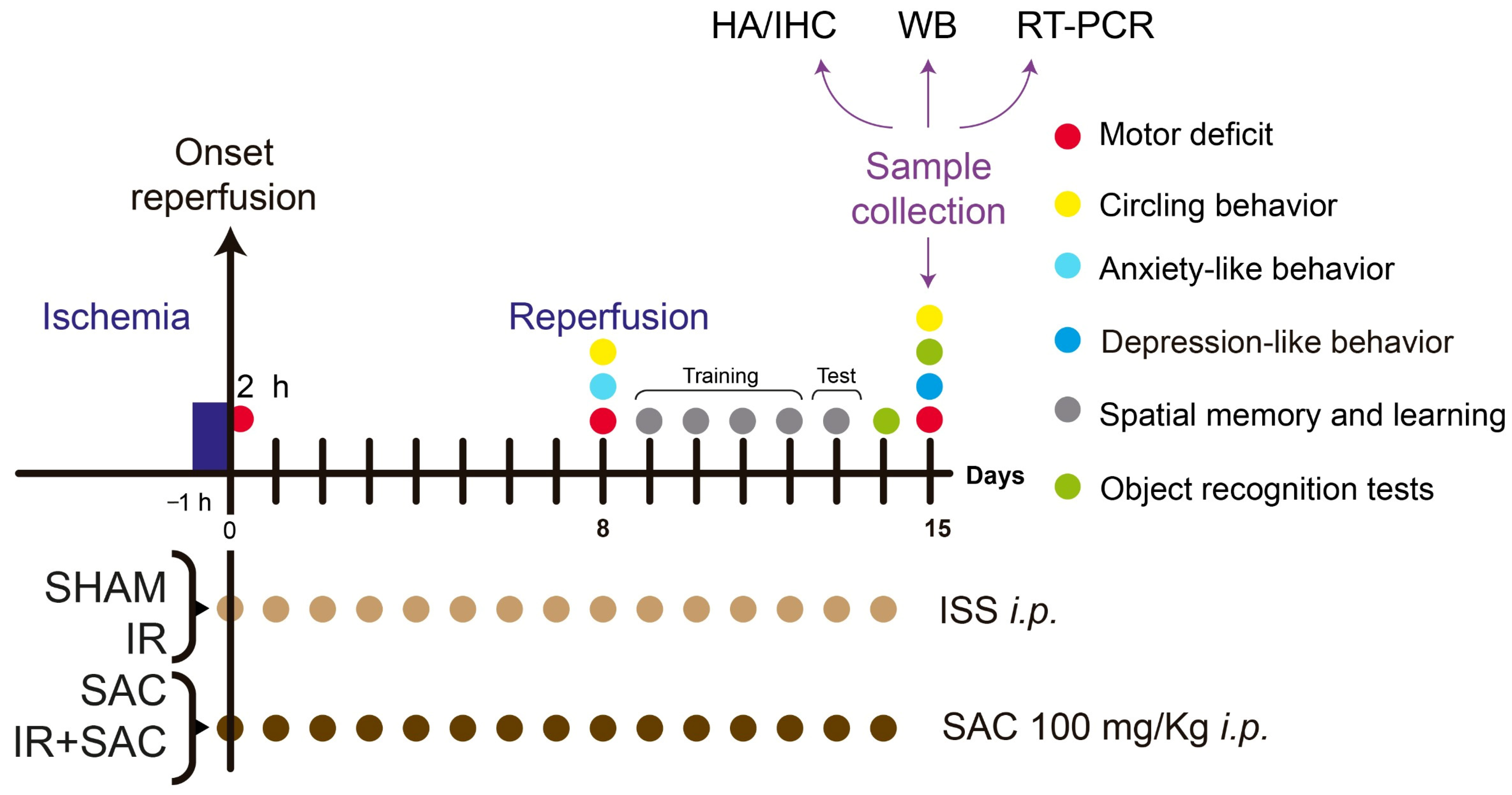

2.2. Experimental Design

- (1)

- SHAM, animals subjected to the dissection procedure without occlusion and treated with isotonic saline solution (ISS, vehicle).

- (2)

- SAC, animals subjected to the dissection procedure without occlusion and treated with SAC.

- (3)

- IR, animals subjected to 1 h of ischemia and 15 days of reperfusion, and treated with ISS.

- (4)

- IR + SAC, animals subjected to 1 h of ischemia and 15 days of reperfusion, and treated with SAC.

2.3. SAC Synthesis

2.4. Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion (MCAO)

2.5. Survival and Body Weight Assessment

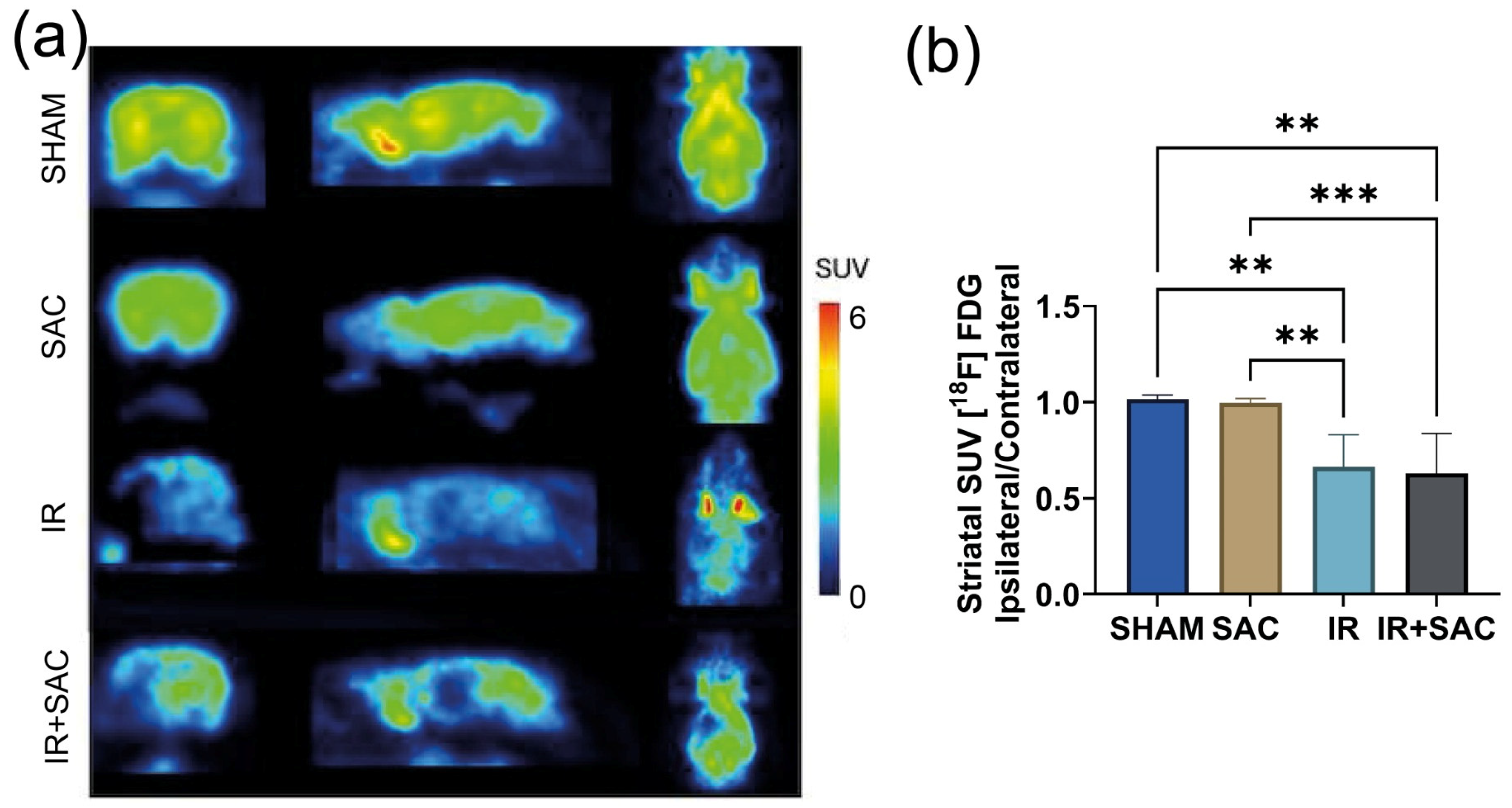

2.6. Micro Positron Emission Tomography (microPET) Imaging and Analysis

2.7. Assessment of Motor Function

2.8. Apomorphine-Induced Circling Behavior

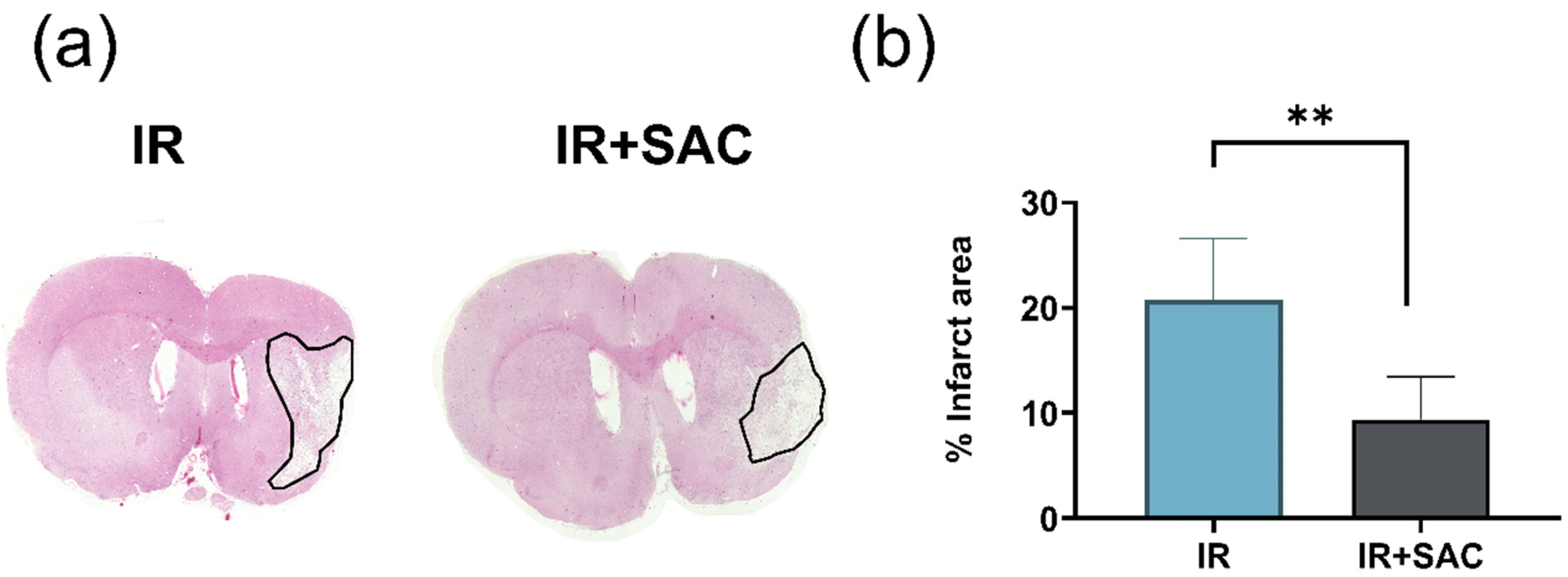

2.9. Histological Analysis

2.9.1. Sample Collection

2.9.2. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

2.9.3. Nissl Staining

2.9.4. Infarct Area

2.10. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

2.11. Western Blot (WB)

2.12. Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

2.13. Anxiety-like Behavior I Elevated Maze

2.14. Depression Like Behavior

2.15. Object Recognition Tests

2.16. Spatial Memory and Learning

2.17. End Points

2.18. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

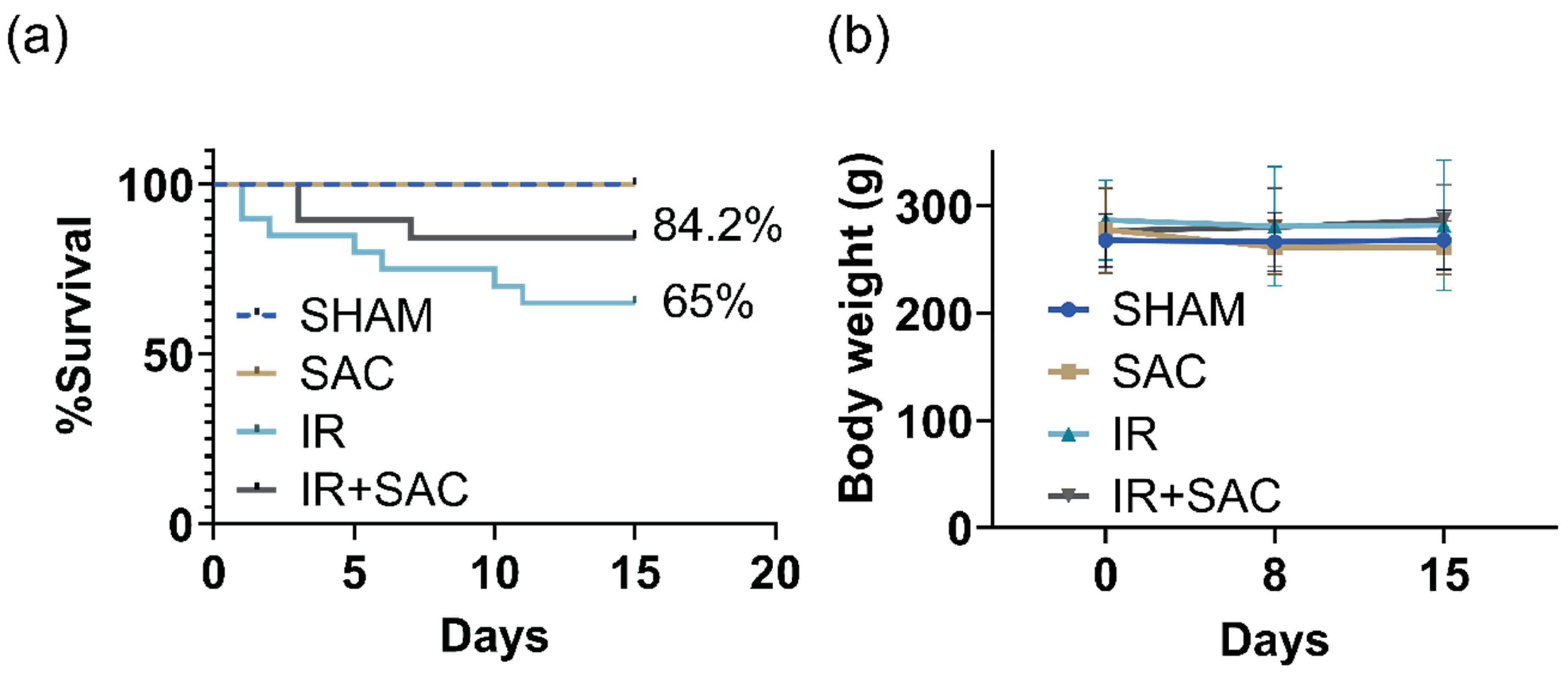

3.1. SAC Does Not Affect Survival and Body Weight

3.2. SAC Reduces Infarct Area, Motor Deficit, and Circling Behavior

3.3. SAC Does Not Modify BDNF and VEGF Levels, but Increases the Content of NGF, p-TrkB, p-AKT, and p-ERK in the Cortex

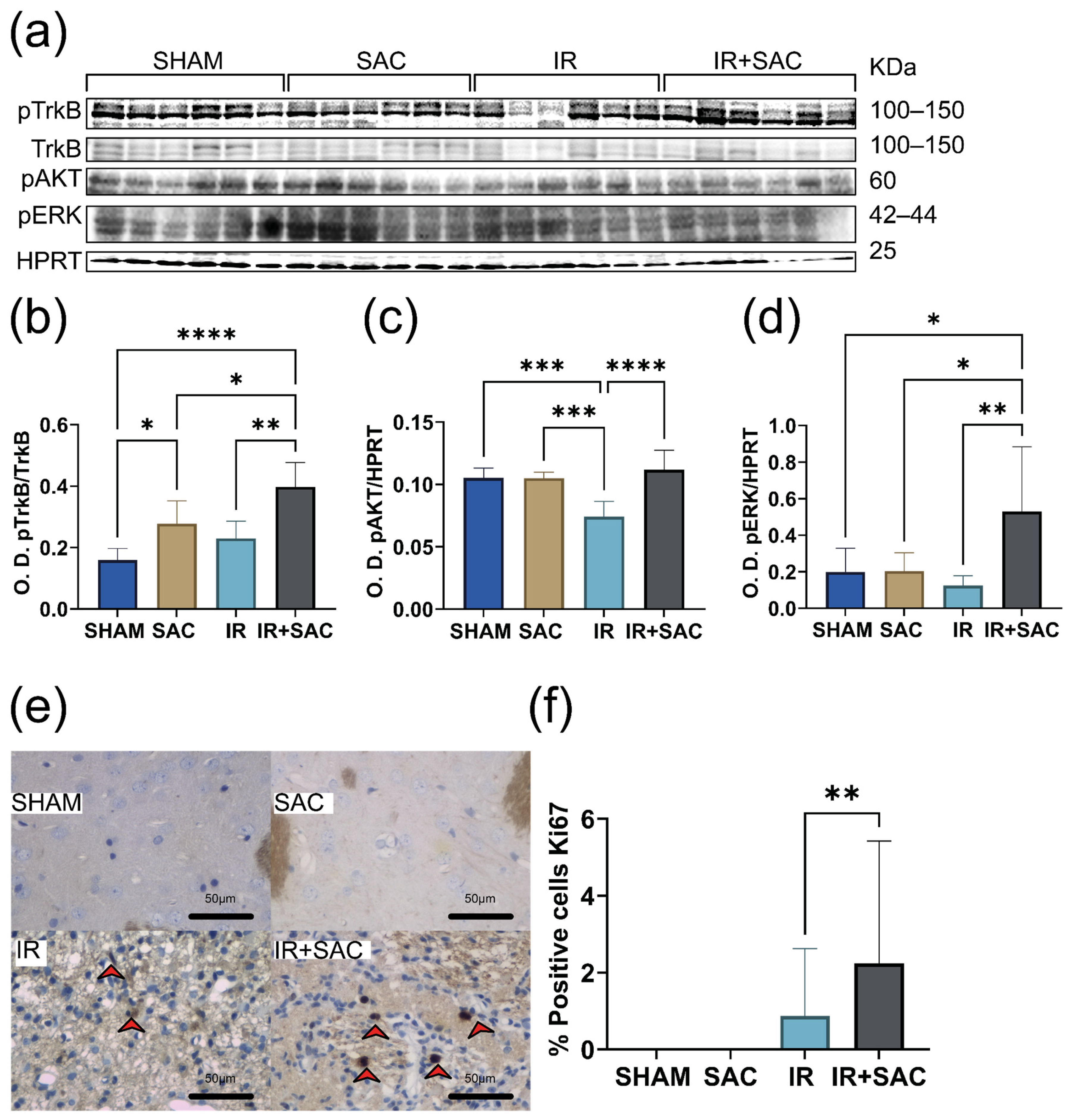

3.4. SAC Increases BDNF Expression and Proliferation, Activating pTrkB, pAKT, and pERK in the Striatum

3.5. SAC Does Not Alter Neurotrophin Expression nor the Levels of pTrkB, pAKT, and pERK in the Hippocampus

3.6. IR Does Not Induce Anxiety-like and Depression-like Behavior

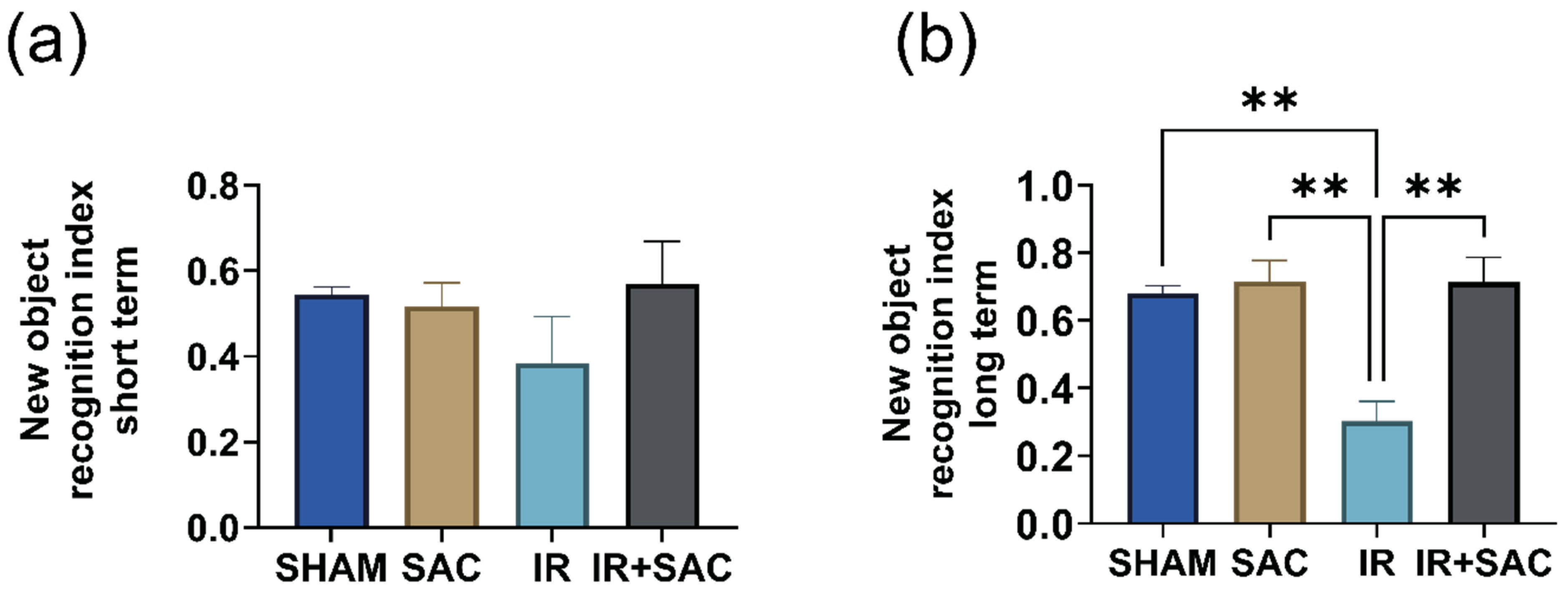

3.7. SAC Enhances Long-Term Recognition Memory, but Does Not Affect Spatial Recognition Memory

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACTB | beta-actin |

| AKT | Protein kinase B |

| ARRIVE | Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments |

| ARE | antioxidant response element |

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| ERK | extracellular signaling-regulated kinase |

| [18F]FDG | 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose |

| HO-1 | hemoxygenase 1 |

| H&E | Hematoxyline eosine |

| IACUC | Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| GAPDH | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate |

| HPRT | hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase |

| IGF | insulin-like growth factor |

| IHC | immunohistochemistry |

| IR | Ischemia-reperfusion |

| MCAO | Middle cerebral artery occlusion |

| microPET | Micro positron emission tomography |

| NFkB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NGF | nerve growth factor |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| 2D-OSEM | 2D Ordered Sets Expectation-Maximization algorithm |

| O.D | Optical density |

| PAF | paraformaldehyde |

| pAKT | phospho-AKT |

| pERK | phospho-ERK |

| PhiP | carcinogenicity caused by 2-amino-1-methyl-6-phenylimidazo[4,5-b]pyridine |

| pTrkB | phospho-TrkB |

| rTPA | recombinant tissue plasminogen activator |

| RT-PCR | reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SAC | S-allyl cysteine |

| SUV | standardized uptake value |

| TrkB | Tropomyosin receptor kinase |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| WB | Western blot |

References

- Feigin, V.L.; Brainin, M.; Norrving, B.; Martins, S.O.; Pandian, J.; Lindsay, P.; Grupper, M.F.; Rautalin, I. World Stroke Organization: Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2025. Int. J. Stroke 2025, 20, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, C.W.; Bushnell, C.D. Stroke in women: A review focused on epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes. J. Stroke 2023, 25, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Amarilla Vallejo, A.; Cantalapiedra Calvete, C.; Rudd, A.; Wolfe, C.; O’Connell, M.D.L.; Douiri, A. Stroke outcomes in women: A population-based cohort study. Stroke 2022, 53, 3072–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 795–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, M.; Liu, Z.J.; Feng, J.; Ma, Y. Neuropsychiatric issues after stroke: Clinical significance and therapeutic implications. World J. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, M.J.; Li, X.; Galligan, D.; Pendlebury, S.T. Cognitive recovery after stroke: Memory. Stroke 2023, 54, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.Y.; Ford, A.; Kutlubaev, M.A.; Almeida, O.P.; Mead, G.E. Depression, anxiety, and suicide after stroke: A narrative review of the best available evidence. Stroke 2022, 53, 1402–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadecola, C.; Buckwalter, M.S.; Anrather, J. Immune responses to stroke: Mechanisms, modulation, and therapeutic potential. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 2777–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Yang, S.; Chu, Y.-H.; Zhang, H.; Pang, X.-W.; Chen, L.; Zhou, L.-Q.; Chen, M.; Tian, D.-S.; Wang, W. Signaling pathways involved in ischemic stroke: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, J.; Gracia-Gil, J.; Sopelana, D.; Ayo-Martín, O.; Vadillo-Bermejo, A.; Touza, B.; Peñalver-Pardines, C.; Zorita, M.D.; Segura, T. Administración de tratamiento trombolítico intravenoso en el ictus isquémico en fase aguda: Resultados en el Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete. Rev. Neurol. 2008, 46, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, K.C.; Schott, T.C.; Jafari, N.; Wohlford-Wessels, M.P.; Finnerty, E.P.; Jacoby, M.R. Tissue plasminogen activator use: Evaluation and initial management of ischemic stroke from an Iowa hospital perspective. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2005, 14, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo-Guerrero, M.; Zevallos, C.; Quiñones, M. Factores asociados a resultados funcionales en pacientes con ictus isquémico tratados con trombólisis endovenosa en un hospital del Perú. Rev. Neuropsiquiatr. 2020, 83, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, V.; Guada, L.; Yavagal, D.R. Global Epidemiology of Stroke and Access to Acute Ischemic Stroke Interventions. Neurology 2021, 97, S6–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haupt, M.; Gerner, S.T.; Bähr, M.; Doeppner, T.R. Neuroprotective strategies for ischemic stroke—Future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.A.; Amruta, N.; Pinteaux, E.; Bix, G.J. Neurogenesis After Stroke: A Therapeutic Perspective. Transl. Stroke Res. 2021, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wang, Z.; Miao, C.Y. Angiogenesis after ischemic stroke. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 1305–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero-Ortega, L.; Gutiérrez-Fernández, M.; Díez-Tejedor, E. Recovery after stroke: New insight to promote brain plasticity. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 768958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szelenberger, R.; Kostka, J.; Saluk-Bijak, J.; Miller, E. Pharmacological interventions and rehabilitation approach for enhancing brain self-repair and stroke recovery. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 18, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaper, S.D. Neurotrophic factors: An overview. In Neurotrophic Factors; Skaper, S., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Kuo, T.-W.; Liu, W.-P.; Chang, C.-P.; Lin, H.-J. Calycosin preserves BDNF/TrkB signaling and reduces post-stroke neurological injury after cerebral ischemia by reducing accumulation of hypertrophic and TNF-α-containing microglia in rats. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2020, 15, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejeda, G.S.; Díaz-Guerra, M. Integral characterization of defective BDNF/TrkB signalling in neurological and psychiatric disorders leads the way to new therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.H.; Holtzman, D.M. BDNF protects the neonatal brain from hypoxic–ischemic injury in vivo via the ERK pathway. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 5775–5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, I.; Krupinski, J.; Goutan, E.; Martí, E.; Ambrosio, S.; Arenas, E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor reduces cortical cell death by ischemia after middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Acta Neuropathol. 2001, 101, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-D.; Wu, C.-L.; Hwang, W.-C.; Yang, D.-I. More insight into BDNF against neurodegeneration: Anti-apoptosis, anti-oxidation, and suppression of autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista-Perez, S.M.; Silva-Islas, C.A.; Sandoval-Marquez, O.U.; Toledo-Toledo, J.; Bello-Martínez, J.M.; Barrera-Oviedo, D.; Maldonado, P.D. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Garlic in Ischemic Stroke: Proposal of a New Mechanism of Protection through Regulation of Neuroplasticity. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.L.; Ali, S.F.; Túnez, I.; Santamaría, A. On the antioxidant, neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties of S-allyl cysteine: An update. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 89, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, M.C.W.; Garnham, N.; Sweeney, S.T.; Landgraf, M. Regulation of Neuronal Development and Function by ROS. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bórquez, D.A.; Urrutia, P.J.; Wilson, C.; van Zundert, B.; Núñez, M.T.; González-Billault, C. Dissecting the role of redox signaling in neuronal development. J. Neurochem. 2016, 137, 506–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriguchi, T.; Matsuura, H.; Kodera, Y.; Itakura, Y.; Katsuki, H.; Saito, H.; Nishiyama, N. Neurotrophic activity of organosulfur compounds having a thioallyl group on cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Neurochem. Res. 1997, 22, 1449–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Nakai, T.; Masutani, T.; Unno, K.; Akao, Y. Improvement of learning and memory in senescence-accelerated mice by S-allylcysteine in mature garlic extract. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syu, J.N.; Yang, M.D.; Tsai, S.Y.; Chiang, E.P.I.; Chiu, S.C.; Chao, C.Y.; Rodriguez, R.L.; Tang, F.Y. S-allylcysteine improves blood flow recovery and prevents ischemic injury by augmenting neovasculogenesis. Cell Transplant. 2017, 26, 1636–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.M.; Yoo, Y.; Kim, W.; Yoo, M.; Kim, D.W.; Won, M.H.; Hwang, I.K.; Yoon, Y.S. Effects of S-allyl-L-cysteine on cell proliferation and neuroblast differentiation in the mouse dentate gyrus. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2011, 73, 1071–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, H.; Khan, M.M.; Khan, A.; Vaibhav, K.; Ahmad, A.; Khuwaja, G.; Ahmed, M.E.; Raza, S.S.; Ashafaq, M.; Tabassum, R.; et al. S-allyl cysteine attenuates oxidative stress-associated cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration in a mouse model of streptozotocin-induced experimental dementia of Alzheimer’s type. Brain Res. 2011, 1389, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarezadeh, M.; Baluchnejadmojarad, T.; Kiasalari, Z.; Afshin-Majd, S.; Roghani, M. Garlic active constituent S-allyl cysteine protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced cognitive deficits in the rat: Possible involved mechanisms. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 795, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurihara, K.; Moteki, H.; Natsume, H.; Ogihara, M.; Kimura, M. The enhancing effects of S-allylcysteine on liver regeneration are associated with increased expression of mRNAs encoding IGF-1 and its receptor in two-thirds partially hepatectomized rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 43, 1776–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, C.; Chatterjee, A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Dutta, N.; Sur, R. S-allyl cysteine inhibits TNF-α-induced inflammation in HaCaT keratinocytes by inhibition of NF-κB-dependent gene expression via sustained ERK activation. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 1328–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Soto, C.Y.; Rangel-López, E.; Galván-Arzate, S.; Colín-González, A.L.; Silva-Palacios, A.; Zazueta, C.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Ramírez, J.; Chavarria, A.; Túnez, I.; et al. S-allylcysteine protects against excitotoxic damage in rat cortical slices via reduction of oxidative damage, activation of Nrf2/ARE binding, and BDNF preservation. Neurotox. Res. 2020, 38, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, C.; Sur, R. S-allyl cysteine alleviates hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative injury and apoptosis through upregulation of Akt/Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling pathway in HepG2 cells. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 3169431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Alvarez, M.J.; Wandosell, F. Stroke and neuroinflamation: Role of sexual hormones. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 1334–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOM-062-ZOO-1999; NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-062-ZOO-1999: Especificaciones Técnicas para la Producción, Cuidado y Uso de los Animales de Laboratorio. Diario Oficial: Mexico City, Mexico, 2001.

- Castillo-Fernández, S.; Silva-Gómez, A.B. Changes in dendritic arborization related to the estrous cycle in pyramidal neurons of layer V of the motor cortex. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2022, 119, 102042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, P.D.; Álvarez-Idaboy, J.R.; Aguilar-González, A.; Lira-Rocha, A.; Jung-Cook, H.; Medina-Campos, O.N.; Pedraza-Chaverrí, J.; Galano, A. Role of allyl group in the hydroxyl and peroxyl radical scavenging activity of S-allylcysteine. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 13408–13417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longa, E.Z.; Weinstein, P.R.; Carlson, S.; Cummins, R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke 1989, 20, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, A.J.; Danckaert, A.; Reese, T.; Gozzi, A.; Paxinos, G.; Watson, C.; Merlo-Pich, E.V.; Bifone, A. A stereotaxic MRI template set for the rat brain with tissue class distribution maps and co-registered anatomical atlas: Application to pharmacological MRI. NeuroImage 2006, 32, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Islas, C.A.; Chánez-Cárdenas, M.E.; Barrera-Oviedo, D.; Ortiz-Plata, A.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Maldonado, P.D. Diallyl trisulfide protects rat brain tissue against the damage induced by ischemia-reperfusion through the Nrf2 pathway. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana-Martínez, R.A.; Silva-Islas, C.A.; Fernández-Orihuela, Y.Y.; Barrera-Oviedo, D.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Hernández-Pando, R.; Maldonado, P.D. The therapeutic effect of curcumin in quinolinic acid-induced neurotoxicity in rats is associated with BDNF, ERK1/2, Nrf2, and antioxidant enzymes. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Jijón, E.; Aparicio-Trejo, O.E.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, R.; León-Contreras, J.C.; Del Carmen Cárdenas-Aguayo, M.; Medina-Campos, O.N.; Tapia, E.; Sánchez-Lozada, L.G.; Hernández-Pando, R.; Reyes, J.L.; et al. The nephroprotection exerted by curcumin in maleate-induced renal damage is associated with decreased mitochondrial fission and autophagy. Biofactors 2016, 42, 686–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Espinosa, J.V.; Arce-Aceves, M.F.; Barrios-Payán, J.; Mata-Espinosa, D.; Lozano-Ordaz, V.; Becerril-Villanueva, E.; Ponce-Regalado, M.D.; Hernández-Pando, R. Effect of Low Doses of Dexamethasone on Experimental Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilhotra, R.; Goel, S.; Gilhotra, N. Behavioral and biochemical characterization of elevated “I-maze” as animal model of anxiety. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2015, 4, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.L.; Ávila, M.; Martins, T.C.; Alvarez-Silva, M.; Winkelmann-Duarte, E.C.; Salgado, A.S.I.; Cidral-Filho, F.J.; Reed, W.R.; Martins, D.F. Medium- and long-term functional behavior evaluations in an experimental focal ischemic stroke mouse model. Cogn. Neurodyn. 2020, 14, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ririe, D.G.; Eisenach, J.C.; Martin, T.J. A Painful Beginning: Early Life Surgery Produces Long-Term Behavioral Disruption in the Rat. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 630889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, K.B.; Kim, J.J. Effects of stress and hippocampal NMDA receptor antagonism on recognition memory in rats. Learn. Mem. 2002, 9, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leger, M.; Quiedeville, A.; Bouet, V.; Haelewyn, B.; Boulouard, M.; Schumann-Bard, P.; Freret, T. Object recognition test in mice. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 2531–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, W.; Zhang, W.; Chen, N.-H. Sexual dimorphism in cerebral ischemia injury. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 711, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, N.; Dietrich, D.W.; Bramlett, H.M.; Raval, A.P. Sexually dimorphic microglia and ischemic stroke. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2019, 25, 1308–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallari, L.H.; Helgason, C.M.; Brace, L.D.; Viana, M.A.; Nutescu, E.A. Sex difference in the antiplatelet effect of aspirin in patients with stroke. Ann. Pharmacother. 2006, 40, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, R.A. Menopause and stroke and the effects of hormonal therapy. Climacteric 2007, 10, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, S.; Yaghi, S.; Bashir, Z. Stroke in young adults. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Hu, X.; Lu, S.; Gan, Y.; Li, P.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Gao, Y. Focal cerebral ischemia activates neurovascular restorative dynamics in mouse brain. Front. Biosci. (Elite Ed.) 2012, 4, 1926–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-S.; Lai, Y.-J.; Nagabhushanam, K.; Ho, C.-T.; Pan, M.-H. S-allylcysteine potently protects against PhIP-induced DNA damage via Nrf2/AhR signaling pathway modulation in normal human colonic mucosal epithelial cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, e2101141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Lee, J.C.; Chang, N.; Chun, H.S.; Kim, W.K. S-Allyl-L-cysteine attenuates cerebral ischemic injury by scavenging peroxynitrite and inhibiting the activity of extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Free Radic. Res. 2006, 40, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, F.; Yousuf, S.; Agrawal, S.K. S-Allyl-L-cysteine diminishes cerebral ischemia-induced mitochondrial dysfunctions in hippocampus. Brain Res. 2009, 1265, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashafaq, M.; Khan, M.M.; Shadab Raza, S.; Ahmad, A.; Khuwaja, G.; Javed, H.; Khan, A.; Islam, F.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Safhi, M.M.; et al. S-Allyl cysteine mitigates oxidative damage and improves neurologic deficit in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. Nutr. Res. 2012, 32, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Jing, X.; Wei, X.; Perez, R.G.; Ren, M.; Zhang, X.; Lou, H. S-Allyl cysteine activates the Nrf2-dependent antioxidant response and protects neurons against ischemic injury in vitro and in vivo. J. Neurochem. 2015, 133, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malliarou, M.; Tsionara, C.; Patsopoulou, A.; Bouletis, A.; Tzenetidis, V.; Papathanasiou, I.; Kotrotsiou, E.; Gouva, M.; Nikolentzos, A.; Sarafis, P. Investigation of factors that affect the quality of life after a stroke. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2023, 1425, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholomé, L.; Winter, Y. Quality of life and resilience of patients with juvenile stroke: A systematic review. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 29, 105129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, M.; Yamada, K.; Olariu, A.; Nawa, H.; Nabeshima, T. Involvement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in spatial memory formation and maintenance in a radial arm maze test in rats. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 7116–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, D.; Gürsoy-Özdemir, Y.; Yemisci, M.; Tuncer, N.; Aktan, S.; Dalkara, T. VEGF protects brain against focal ischemia without increasing blood–brain permeability when administered intracerebroventricularly. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2005, 25, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jin, K.; Xie, L.; Childs, J.; Mao, X.O.; Logvinova, A.; Greenberg, D.A. VEGF-induced neuroprotection, neurogenesis, and angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1843–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bi, F.; Xiao, B.; Zhang, H.; Ye, W.; Zhang, H.; et al. NGF/FAK signal pathway is implicated in angiogenesis after acute cerebral ischemia in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 672, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friguls, B.; Petegnief, V.; Justicia, C.; Pallàs, M.; Planas, A.M. Activation of ERK and Akt signaling in focal cerebral ischemia: Modulation by TGF-α and involvement of NMDA receptor. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002, 11, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Omori, N.; Jin, G.; Wang, S.J.; Sato, K.; Nagano, I.; Shoji, M.; Abe, K. Cooperative expression of survival p-ERK and p-Akt signals in rat brain neurons after transient MCAO. Brain Res. 2003, 962, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, H.; Warita, H.; Sasaki, C.; Zhang, W.R.; Sakai, K.; Shiro, Y.; Mitsumoto, Y.; Mori, T.; Abe, K. Immunoreactive Akt, PI3-K and ERK protein kinase expression in ischemic rat brain. Neurosci. Lett. 1999, 274, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.C.; Lu, L.; Zhou, H.J. Relationship between the MAPK/ERK pathway and neurocyte apoptosis after cerebral infarction in rats. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 5374–5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Liu, H.; Yan, R.; Hu, M. PI3K/Akt and ERK/MAPK signaling promote different aspects of neuron survival and axonal regrowth following rat facial nerve axotomy. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 42, 3515–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-H.; Chen, C.-C.; Hung, T.-H.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Chao, M.; Shyue, S.-K.; Chen, S.-F. Activation of TrkB/Akt signaling by a TrkB receptor agonist improves long-term histological and functional outcomes in experimental intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 26, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidaurre, O.G.; Gascón, S.; Deogracias, R.; Sobrado, M.; Cuadrado, E.; Montaner, J.; Rodríguez-Peña, A.; Díaz-Guerra, M. Imbalance of neurotrophin receptor isoforms TrkB-FL/TrkB-T1 induces neuronal death in excitotoxicity. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.M.; Kim, Y.R.; Shin, Y.I.; Ha, K.T.; Lee, S.Y.; Shin, H.K.; Choi, B.T. Therapeutic potential of a combination of electroacupuncture and TrkB-expressing mesenchymal stem cells for ischemic stroke. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Deng, X.; Liu, M.; He, M.; Long, W.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Liu, T.; So, K.F.; Fu, Q.-L.; et al. Intranasal Delivery of BDNF-Loaded Small Extracellular Vesicles for Cerebral Ischemia Therapy. J. Control. Release 2023, 357, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.W.; Bang, M.S.; Han, T.R.; Ko, Y.J.; Yoon, B.W.; Kim, J.H.; Kang, L.M.; Lee, K.M.; Kim, M.H. Exercise increased BDNF and TrkB in the contralateral hemisphere of the ischemic rat brain. Brain Res. 2005, 1052, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Muñoz-Palma, E.; González-Billault, C. From birth to death: A role for reactive oxygen species in neuronal development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 80, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steliga, A.; Lietzau, G.; Wójcik, S.; Kowiański, P. Transient cerebral ischemia induces the neuroglial proliferative activity and the potential to redirect neuroglial differentiation. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2023, 127, 102192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Lu, X.; Pan, Q.; Wang, B.; Pong, U.K.; Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Lin, S.; Feng, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Cranial bone transport promotes angiogenesis, neurogenesis, and modulates meningeal lymphatic function in middle cerebral artery occlusion rats. Stroke 2022, 53, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woitke, F.; Blank, A.; Fleischer, A.L.; Zhang, S.; Lehmann, G.M.; Broesske, J.; Haase, M.; Redecker, C.; Schmeer, C.W.; Keiner, S. Post-stroke environmental enrichment improves neurogenesis and cognitive function and reduces the generation of aberrant neurons in the mouse hippocampus. Cells 2023, 12, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, F.; Liu, J.; Bernabeu, R. Neurogenesis following brain ischemia. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 2002, 134, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Cui, H.R.; Yang, S.Z.; Sun, H.P.; Qiu, M.H.; Feng, X.Y.; Sun, F.Y. VEGF enhances cortical newborn neurons and their neurite development in adult rat brain after cerebral ischemia. Neurochem. Int. 2009, 55, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dmitrieva, V.G.; Stavchansky, V.V.; Povarova, O.V.; Skvortsova, V.I.; Limborska, S.A.; Dergunova, L.V. Effects of ischemia on the expression of neurotrophins and their receptors in rat brain structures outside the lesion site, including on the opposite hemisphere. Mol. Biol. 2016, 50, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäbitz, W.R.; Steigleder, T.; Cooper-Kuhn, C.M.; Schwab, S.; Sommer, C.; Schneider, A.; Kuhn, H.G. Intravenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances poststroke sensorimotor recovery and stimulates neurogenesis. Stroke 2007, 38, 2165–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohab, J.J.; Fleming, S.; Blesch, A.; Carmichael, S.T. A neurovascular niche for neurogenesis after stroke. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 13007–13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zacharek, A.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, H.; Li, Y.; Roberts, C.; Lu, M.; Kapke, A.; Chopp, M. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase regulates brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression and neurogenesis after stroke in mice. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 2366–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.G.; Zhang, L.; Tsang, W.; Soltanian-Zadeh, H.; Morris, D.; Zhang, R.; Goussev, A.; Powers, C.; Yeich, T.; Chopp, M. Correlation of VEGF and angiopoietin expression with disruption of blood–brain barrier and angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2002, 22, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinkalam, E.; Arabi, S.M.; Komaki, A.; Ranjbar, K. The preconditioning effect of different exercise training modes on middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced behavioral deficit in senescent rats. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-F.; Bian, W.; Wei, J.; Hu, S. Anxiety-reducing effects of working memory training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 331, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chokkalla, A.K.; Jeong, S.; Mehta, S.L.; Davis, C.K.; Morris-Blanco, K.C.; Bathula, S.; Qureshi, S.S.; Vemuganti, R. Cerebroprotective role of N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated protein) after experimental stroke. Stroke 2023, 54, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Q.; Yu, Y.; Zhan, G.; Zhang, X.; Gao, S.; Han, T.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. The sirtuin 5 inhibitor MC3482 ameliorates microglia-induced neuroinflammation following ischaemic stroke by upregulating the succinylation level of annexin-A1. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2024, 19, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerril-Chávez, H.; Colín-González, A.L.; Villeda-Hernández, J.; Galván-Arzate, S.; Chavarría, A.; de Lima, M.E.; Túnez, I.; Santamaría, A. Protective effects of S-allyl cysteine on behavioral, morphological and biochemical alterations in rats subjected to chronic restraint stress: Antioxidant and anxiolytic effects. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 35, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, S.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wan, J.; Sun, K. Electroacupuncture improves cognitive impairment after ischemic stroke based on regulation of mitochondrial dynamics through SIRT1/PGC-1α pathway. Brain Res. 2024, 1844, 149139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Morales, M.A.; Escobar, I.; Saul, I.; Jackson, C.W.; Ferrier, F.J.; Fagerli, E.A.; Raval, A.P.; Dave, K.R.; Perez-Pinzon, M.A. Resveratrol preconditioning mitigates ischemia-induced septal cholinergic cell loss and memory impairments. Stroke 2023, 54, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, M.; He, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H. Dexmedetomidine alleviates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury via inhibiting autophagy through PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. J. Mol. Histol. 2023, 54, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlini, V.P. The object recognition task: A new proposal for the memory performance study. In Object Recognition; Cao, T.P., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, M.; Biala, G. The novel object recognition memory: Neurobiology, test procedure, and its modifications. Cogn. Process. 2012, 13, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueptow, L.M. Novel object recognition test for the investigation of learning and memory in mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2017, 126, 55718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, S.N.; Cole, C.; Ryan, J.D. Relational memory for object identity and spatial location in rats with lesions of perirhinal cortex, amygdala and hippocampus. Brain Res. Bull. 2005, 65, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | HA/IHC | WB | RT-PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| SHAM | n = 3 | n = 6 | n = 4 |

| SAC | n = 3 | n = 6 | n = 4 |

| IR | n = 4 | n = 6 | n = 4 |

| IR + SAC | n = 6 | n = 6 | n = 4 |

| Procedure | Normal Motor Function (Value = 0) | Altered Motor Function (Value = 1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobility assessment | The animal is placed on a flat surface. | The animal actively explores its surroundings. | The animal remains immobile. |

| Contralateral grasp capacity | The animal is held by the tail and brought close to a rope suspended 30 cm above the ground. | The animal grips the rope with both forelimbs. | The animal can only grip with the ipsilateral forelimb. |

| Forelimb strength test | The animal is held by the tail and brought close to a rope suspended 30 cm above the ground. | The animal maintains its grip for more than 5 s. | The animal fails to grasp the rope with both forelimbs and releases it within 5 s. |

| Rotational behavior test | The animal is lifted by the base of the tail just enough to keep its forelimbs in contact with the surface. | The animal propels its body forward. | The animal exhibits rotational movements toward the contralateral side. |

| Forelimb extension reflex | The animal is lifted by the base of the tail, and it has no contact with the table. | Upon lifting, the animal extends both forelimbs. | The animal fails to extend the contralateral forelimb, either retracting it or exhibiting repeated contraction movements. |

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| BDNF (NM_001270630.1) | AAAGGCATTGGAACTCCCAG | ATCCTTATGAATCGCCAGCCA |

| NGF (XM_039102402.1) | CGTACAGGCAGAACCGTACA | GAGGGCTGTGTCAAGGGAAT |

| VEGF (NM_001287114.1) | GTCACCGTCGACAGAACAGT | GACCCAAAGTGCTCCTCGAA |

| ACTB (NM_03114.3) | GATCAGCAAGCAGGAGTACGA | AACGCAGCTCAGTAACAGTCC |

| GAPDH (XM_063285517.1) | CCCCAACACTGAGCATCTCC | GTATTCGAGAGAAGGGAGGGC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bautista-Perez, S.M.; Silva-Islas, C.A.; Cardenas-Aguayo, M.-d.-C.; Lora-Marín, O.-R.; Silva-Lucero, M.-d.-C.; Avendaño-Estrada, A.; Ávila-Rodríguez, M.A.; Lara-Espinosa, J.V.; Hernández-Pando, R.; Menes-Arzate, M.; et al. Garlic-Derived S-allylcysteine Improves Functional Recovery and Neurotrophin Signaling After Brain Ischemia in Female Rats. Nutrients 2026, 18, 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020362

Bautista-Perez SM, Silva-Islas CA, Cardenas-Aguayo M-d-C, Lora-Marín O-R, Silva-Lucero M-d-C, Avendaño-Estrada A, Ávila-Rodríguez MA, Lara-Espinosa JV, Hernández-Pando R, Menes-Arzate M, et al. Garlic-Derived S-allylcysteine Improves Functional Recovery and Neurotrophin Signaling After Brain Ischemia in Female Rats. Nutrients. 2026; 18(2):362. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020362

Chicago/Turabian StyleBautista-Perez, Sandra Monserrat, Carlos Alfredo Silva-Islas, Maria-del-Carmen Cardenas-Aguayo, Obed-Ricardo Lora-Marín, Maria-del-Carmen Silva-Lucero, Arturo Avendaño-Estrada, Miguel A. Ávila-Rodríguez, Jacqueline V. Lara-Espinosa, Rogelio Hernández-Pando, Martha Menes-Arzate, and et al. 2026. "Garlic-Derived S-allylcysteine Improves Functional Recovery and Neurotrophin Signaling After Brain Ischemia in Female Rats" Nutrients 18, no. 2: 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020362

APA StyleBautista-Perez, S. M., Silva-Islas, C. A., Cardenas-Aguayo, M.-d.-C., Lora-Marín, O.-R., Silva-Lucero, M.-d.-C., Avendaño-Estrada, A., Ávila-Rodríguez, M. A., Lara-Espinosa, J. V., Hernández-Pando, R., Menes-Arzate, M., Pedraza-Chaverri, J., Aparicio-Trejo, O. E., Sánchez-Thomas, R., Figueroa, A., Barrera-Oviedo, D., & Maldonado, P. D. (2026). Garlic-Derived S-allylcysteine Improves Functional Recovery and Neurotrophin Signaling After Brain Ischemia in Female Rats. Nutrients, 18(2), 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu18020362