Government Subsidies and the Competitiveness of Energy Storage Enterprises: The Moderating Effect of Electricity Price

Abstract

1. Introduction

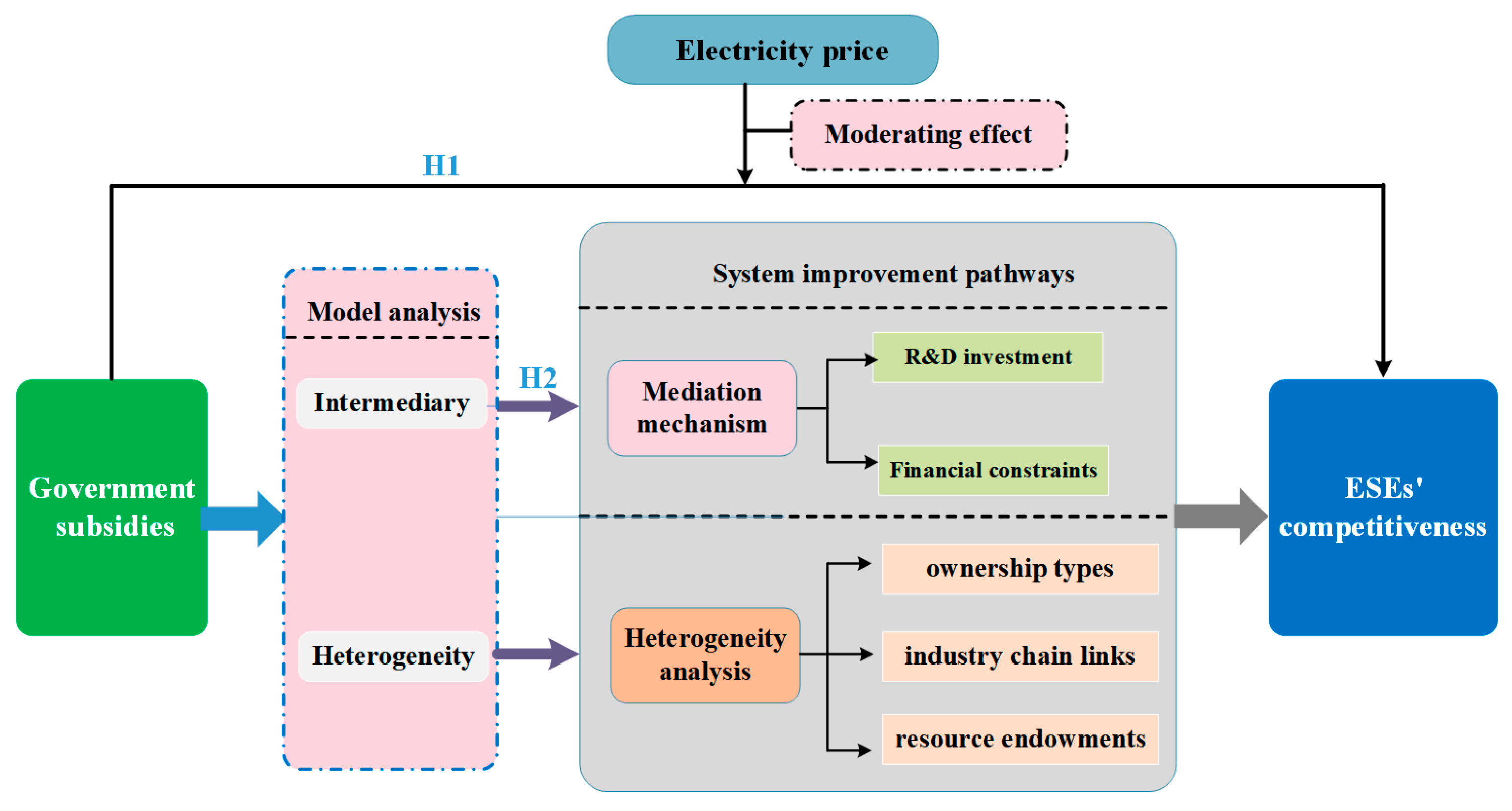

2. Literature Review and Model Justifications

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. The Incentive Effect of Government Subsidies

2.1.2. The Adverse Consequences of Government Subsidies

2.1.3. Literature Gaps

2.2. Theoretical Justifications

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. The Direct Impact of Government Subsidies on the Competitiveness of ESEs

3.2. The Indirect Impact of Government Subsidies on the Competitiveness of ESEs

4. Research Design

4.1. Sample Selection and Data Source

4.2. Measures of Variables

4.2.1. Dependent Variable

4.2.2. Independent Variable

4.2.3. Mechanism Variables

4.2.4. Moderating Variable

4.2.5. Control Variables

4.3. Model Specification

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Benchmark Regression Results

5.3. Robustness Checks

5.4. Endogeneity Issues

5.5. Mechanism Analysis

5.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.6.1. Ownership Type Characteristics

5.6.2. Industry Chain Links Characteristics

5.6.3. Resource Endowments Characteristics

5.7. Further Analysis

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Main Findings

- (a)

- Overall, government subsidies demonstrate a marked enhancing effect on the competitiveness of ESEs. The baseline regression results indicate a coefficient of 0.019 for the core explanatory variable, InSubs, which is statistically significant at the 1% level. This finding indicates that government subsidies enable ESEs to integrate and utilize external resources more effectively, thereby cultivating sustainable competitiveness. The robustness of this conclusion is affirmed through a series of tests, including addressing potential endogeneity via the instrumental variable approach and applying Propensity Score Matching (PSM). The consistent outcomes underscore the reliability of the findings and highlight the indispensable role of government subsidies as a policy instrument in motivating ESEs to enhance their core competitiveness.

- (b)

- Heterogeneity analysis results indicate that the positive impact of government subsidies on enterprise competitiveness is more pronounced in non-state-owned ESEs, energy storage system integration enterprises, and ESEs in resource-rich provinces. A more intriguing outcome is that the incentive effects of subsidies on resource endowment and industry chain integration are more pronounced than those on the ownership type, which exhibit relatively minor differential incentive effects.

- (c)

- The findings further demonstrate that electricity prices exert a positive moderating effect on the relationship between government subsidies and the competitiveness of ESEs. Specifically, when electricity prices exceed a certain threshold (0.8819 RMB/kWh), a crowding-out effect on the positive correlation between subsidies and corporate competitiveness becomes evident. Consequently, the complementary effects of market mechanisms and policy incentives should be fully leveraged to stimulate the sustainable development of the energy storage industry.

6.2. Policy Implications

- (1)

- The government should improve the effectiveness of subsidy policies to further encourage investment in the energy storage industry. China has witnessed a gradual acceleration in the pace of energy storage construction, with local governments playing a pivotal role in the promotion of this industry. Nevertheless, the substantial subsidies flowing into the energy storage industry have exhibited a “flood, flooding” and “too much but not the best” characteristic. Consequently, government bodies in emerging markets should leverage market competition as a tool to identify eligible ESEs for subsidies, conduct a scientific assessment of the market value of energy storage, and provide targeted support for high-quality energy storage resources, leading enterprises, and direct energy storage demonstration projects with advanced technology and greater competitiveness. This approach is preferable to a uniform subsidy policy, as it has the potential to enhance the policy’s effectiveness in fostering the growth of the energy storage industry.

- (2)

- The extensive deployment of ‘government subsidies’ is a crucial element of China’s industrial strategy, with the advancement of the energy storage sector intricately linked to national energy policies and regional economic growth. It would be prudent for local authorities to prioritize the advancement of energy storage technologies within their jurisdictions and implement a range of targeted subsidy strategies. Our research demonstrates that government subsidies exert a considerable influence on non-state-owned energy storage enterprises, energy storage system integrators, and enterprises situated in resource-abundant regions. In light of these insights, it is recommended that local governments adapt their subsidy programs and types in accordance with ownership structures, industry chain positions, and local cumulative installed energy storage capacity. Such efforts will ensure that precise ‘policy incentive’ signals encourage ESEs to enhance R&D innovation, external financing conditions, and the efficacy of subsidies. In addition, given the divergent moderating effects of electricity prices on subsidy efficacy across different regions, governments should formulate regional subsidy policies tailored to local conditions. In regions with higher electricity prices, subsidies should be appropriately reduced to guide ESEs toward leveraging market-based mechanisms to improve operational efficiency. Conversely, in regions with lower electricity prices, while maintaining reasonable subsidies, it is imperative to refine electricity pricing mechanisms and explore the incorporation of energy storage costs into the electricity pricing system.

- (3)

- In addition to providing financial assistance, the government should consider the implementation of a robust regulatory framework, placing greater focus on the daily management of subsidized energy storage projects, and refining the rules for the utilization of subsidized funds. It would be prudent for regulatory bodies to periodically audit the R&D projects funded by subsidies to ensure that funds are not misallocated. Preventing rent-seeking and fraudulent activities is essential to ensure that government subsidies are allocated to genuinely competitive enterprises. This approach will better fulfill the intended incentive role of subsidies and promote the high-quality and sustainable development of the energy storage industry.

6.3. Research Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Liao, H. A real options-based framework for multi-generation liquid air energy storage investment decision under multiple uncertainties and policy incentives. Energy 2024, 309, 133025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Zhao, Y. Energy Storage Technology Innovation, Performance Appraisal Pressure of Officials and Energy Security: An Empirical Study in the Context of Energy Transition. Renew. Energy 2025, 251, 123482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, X.; Hueng, C.J. The user-side energy storage investment under subsidy policy uncertainty. Appl. Energy 2025, 386, 125508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Mickiewicz, T. Subsidies, rent seeking and performance: Being young, small or private in China. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhang, A. Impact of government subsidies on total factor productivity of energy storage enterprises under dual-carbon targets. Energy Policy 2024, 187, 114046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Quan, L.; Guan, K. Does FinTech promote corporate competitiveness? Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhang, A. Government subsidies, market competition and the TFP of new energy enterprises. Renew. Energy 2023, 216, 119090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Yuan, G.; Wu, X.; Xie, P. The effects of government subsidies on the economic profits of hydrogen energy enterprises–An analysis based on A-share listed enterprises in China. Renew. Energy 2023, 211, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, W.; Guo, X.; Su, B.; Guo, S.; Jing, Y.; Zhang, X. Advancements in Energy-Storage Technologies: A Review of Current Developments and Applications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lin, B. Clean energy business expansion and financing availability: The role of government and market. Energy Policy 2024, 191, 114183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K.J. The economic implications of learning by doing. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1962, 29, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhok, A.; Marques, R. Towards an action-based perspective on firm competitiveness. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2014, 17, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Xi, B.; Xu, X.; Xuan, S. The impact of government subsidies on green innovation performance in new energy enterprises: A digital transformation perspective. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 94, 103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Yang, K.; Bai, X. Impact of financial subsidies on the R&D intensity of new energy vehicles: A case study of 88 listed enterprises in China. Energy Strategy Rev. 2021, 33, 100580. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzoglou, P.; Chatzoudes, D. The role of innovation in building competitive advantages: An empirical investigation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2018, 21, 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Fei, J. Government subsidies, enterprise operating efficiency, and “stiff but deathless” zombie firms. Econ. Model. 2022, 107, 105728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Cui, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y. Impact of government subsidies on the innovation performance of the photovoltaic industry: Based on the moderating effect of carbon trading prices. Energy Policy 2022, 170, 113216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelino, M.; Dinc, I.S. Corporate distress and lobbying: Evidence from the Stimulus Act. J. Financ. Econ. 2014, 114, 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ni, H.; Yang, X.; Kong, L.; Liu, C. Government subsidies and total factor productivity of enterprises: A life cycle perspective. Econ. Politica 2023, 40, 153–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, R.; Lin, B. Positive or negative? Study on the impact of government subsidy on the business performance of China’s solar photovoltaic industry. Renew. Energy 2022, 189, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, X.; Su, S.; Su, Y. How green technological innovation ability influences enterprise competitiveness. Technol. Soc. 2019, 59, 101136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Sun, H.; Zhang, T. Do environmental subsidies spur environmental innovation? Empirical evidence from Chinese listed firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-F.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Su, B. Impact of government subsidy on the optimal R&D and advertising investment in the cooperative supply chain of new energy vehicles. Energy Policy 2022, 164, 112885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Fan, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, J. Investment decisions and strategies of China’s energy storage technology under policy uncertainty: A real options approach. Energy 2023, 278, 127905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, B.; Xie, P. An optimal sequential investment decision model for generation-side energy storage projects in China considering policy uncertainty. J. Energy Storage 2024, 83, 110748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, M.; Ma, J.; Yang, W. A study of licensing strategies for energy storage technologies in the renewable electricity supply chain under government subsidies. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 420, 138343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dong, X.; Dong, K. How digital industries affect China’s carbon emissions? Analysis of the direct and indirect structural effects. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Chen, J.; Wesseh Jr, P.K. Peak-valley tariffs and solar prosumers: Why renewable energy policies should target local electricity markets. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.; Liu, X.; Hong, Y.; Yang, S. Moving beyond economic criteria: Exploring the social impact of green innovation from the stakeholder management perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Tan, H.; Tu, Y. Government subsidies, market competition and firms’ technological innovation efficiency. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Dmytriyev, S.D.; Phillips, R.A. Stakeholder theory and the resource-based view of the firm. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1757–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, L. Performance characteristics, spatial connection and industry prospects for China’s energy storage industry based on Chinese listed companies. J. Energy Storage 2023, 62, 106907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Khurshid, A.; Rauf, A.; Calin, A.C. Government subsidies’ influence on corporate social responsibility of private firms in a competitive environment. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B. Theory and methods of enterprise competitiveness assessment. China Ind. Econ. 2003, 3, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hadlock, C.J.; Pierce, J.R. New evidence on measuring financial constraints: Moving beyond the KZ index. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 1909–1940. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Yu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhou, B. Multi-path adjustment in digital transformation and enhancement of enterprise competitiveness. J. Innov. Knowl. 2025, 10, 100735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, B.H.; Nickerson, J.A. Correcting for endogeneity in strategic management research. Strateg. Organ. 2003, 1, 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Fang, C.-C. The influence of corporate networks on competitive advantage: The mediating effect of ambidextrous innovation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2022, 34, 946–960. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Lucey, B.M. Sustainable behaviors and firm performance: The role of financial constraints’ alleviation. Econ. Anal. Policy 2022, 74, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, X. The impact of carbon markets on the financial performance of power producers: Evidence based on China. Energy Econ. 2023, 127, 107119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Q.; Li, X.; Pan, Y. The impact of government subsidy on photovoltaic enterprises independent innovation based on the evolutionary game theory. Energy 2023, 285, 129385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Xue, X.; Liu, Y. More government subsidies, more green innovation? The evidence from Chinese new energy vehicle enterprises. Renew. Energy 2022, 197, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NDRC. The notice on “Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Development of Energy Storage Technology and Industry”. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-10/12/content_5231304.htm (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Sukumar, A.; Jafari-Sadeghi, V.; Garcia-Perez, A.; Dutta, D.K. The potential link between corporate innovations and corporate competitiveness: Evidence from IT firms in the UK. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NDRC & NEA. The Implementation Programme for the Development of New Energy Storage in the 14th Five-Year Plan. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-03/22/content_5680358.htm (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Zhang, H.; Gao, S.; Zhou, P. Role of digitalization in energy storage technological innovation: Evidence from China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 171, 113014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhou, W.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X. Subsidy strategy for distributed photovoltaics: A combined view of cost change and economic development. Energy Econ. 2021, 97, 105087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, Q.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Q.; An, X. Energy storage in China: Development progress and business model. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator Dimension | Sub-Indicators | Weight (%) | Data Definition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterprise competitiveness | Scale dimension | Operating Revenue | 20 | Directly obtained from the CSMAR database |

| Net assets | 11 | |||

| Net profit | 16 | |||

| Growth dimension | Average annual growth rate of operating revenue over the past 3 years | 17 | (Current period operating revenue/Operating revenue three years ago) (1/3) − 1 | |

| Average annual growth rate of net profit over the past 3 years | 14 | (Current period net profit/Net profit three years ago) (1/3) − 1 | ||

| Efficiency dimension | Return on total assets | 8 | Net profit/Total assets | |

| Return on net assets | 8 | Net profit/Net assets | ||

| Labor efficiency | 6 | Operating Revenue/Total number of employees | ||

| Variable | Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Enterprise competitiveness | Firmcompte | The calculation was performed in accordance with the established indicator system. |

| Government subsidies | InSubs | The natural logarithm of “Government subsidies to current profit and loss” |

| R&D expenditure | RD | R&D expenditure as a percentage of operating revenue (%) |

| Financing constraints | SA | SA index |

| Leverage | Lev | Total liabilities at year-end/total assets at year-end |

| Enterprise growth | Growth | Growth rate of business revenue |

| Ownership | SOE | The value of state-owned enterprises is equal to 1; otherwise,0 |

| Shareholding concentration | TOP1 | Number of shares held by the largest shareholder/total number of shares |

| Proportion of independent directors | Indep | Number of independent directors/total board members |

| Enterprise size | Size | The natural logarithm of total assets |

| Cash holding ratio | Cashflow | Net cash flows from operating activities/total assets |

| Economic growth | Gdp | The natural logarithm of the regional gross domestic product |

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Std.Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firmcompte | 2480 | 0.715 | 0.365 | 0.015 | 1.301 |

| InSubs | 2480 | 16.160 | 1.954 | 9.393 | 20.340 |

| RD | 2480 | 0.038 | 0.0310 | 0.000 | 0.146 |

| SA | 2480 | −3.142 | 1.495 | −4.470 | 0.000 |

| Lev | 2480 | 0.477 | 0.190 | 0.000 | 0.900 |

| Growth | 2480 | 0.185 | 0.354 | −0.490 | 1.857 |

| SOE | 2480 | 0.295 | 0.456 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| TOP1 | 2480 | 0.304 | 0.193 | 0.000 | 0.930 |

| Indep | 2480 | 0.363 | 0.204 | 0.000 | 0.857 |

| Size | 2480 | 22.430 | 1.512 | 19.320 | 26.480 |

| Cashflow | 2480 | 0.146 | 0.230 | −0.310 | 1.202 |

| Gdp | 2480 | 10.880 | 0.658 | 9.107 | 11.820 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firmcompte | Firmcompte | Firmcompte | |

| InSubs | 0.0271 *** | 0.0226 *** | 0.0190 *** |

| (3.77) | (3.37) | (2.83) | |

| Lev | −1.045 *** | −0.966 *** | |

| (−10.53) | (−9.70) | ||

| Growth | 0.421 *** | 0.430 *** | |

| (11.14) | (11.52) | ||

| SOE | −0.108 ** | −0.208 *** | |

| (−2.15) | (−3.20) | ||

| TOP1 | 0.732 *** | 0.682 *** | |

| (8.50) | (8.10) | ||

| Indep | −0.131 | −0.111 | |

| (−1.37) | (−1.17) | ||

| Size | 0.036 * | ||

| (1.69) | |||

| Cashflow | 0.480 *** | ||

| (6.99) | |||

| Gdp | 0.308 * | ||

| (1.80) | |||

| Constant | 0.147 | 0.705 *** | −3.593 * |

| (0.98) | (4.39) | (−1.88) | |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 2480 | 2480 | 2480 |

| R2 | 0.360 | 0.468 | 0.488 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firmcompte1 | Firmcompte | Firmcompte | Firmcompte | |

| InSubs | 0.0187 *** | 0.0238 *** | 0.0181 ** | |

| (5.13) | (2.88) | (2.17) | ||

| Subs | 0.0839 *** | |||

| (5.40) | ||||

| Constant | −2.729 *** | −2.769 | −7.303 *** | 1.682 |

| (−3.20) | (−1.46) | (−3.03) | (1.48) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 2480 | 2480 | 1736 | 2480 |

| R2 | 0.358 | 0.495 | 0.541 | 0.330 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| 2SLS (1st) | 2SLS (2nd) | |

| IV | 0.403 *** | |

| (14.30) | ||

| InSubs | 0.091 *** | |

| (5.72) | ||

| Constant | 4.340 *** | −1.980 *** |

| (6.68) | (−9.07) | |

| Controls | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES |

| Observations | 2232 | 2232 |

| R2 | 0.321 | |

| KP-LM statistic | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| [202.151] | [202.151] | |

| CD-Wald statistic | 559.133 | 559.133 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| 1:1 Nearest Neighbor Matching | Kernel Matching Balance | |

| Firmcompte | Firmcompte | |

| InSubs | 0.0162 *** | 0.0190 *** |

| (4.18) | (5.19) | |

| Constant | −2.503 *** | −2.551 *** |

| (−2.63) | (−2.82) | |

| Controls | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES |

| Observations | 2296 | 2465 |

| R2 | 0.624 | 0.624 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| RD | SA | |

| InSubs | 0.0987 *** | −0.0815 *** |

| (3.52) | (−6.40) | |

| Constant | −10.00 | 2.787 |

| (−1.43) | (1.01) | |

| Controls | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES |

| Observations | 2480 | 2.480 |

| R2 | 0.696 | 0.716 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firmcompte | Firmcompte | Firmcompte | |

| InSubs × NSOE | 0.004 *** | ||

| (2.50) | |||

| InSubs × SI | 0.0224 * | ||

| (1.65) | |||

| InSubs × RS | 0.0389 *** | ||

| (2.11) | |||

| Constant | −1.664 *** | −1.307 *** | −1.314 *** |

| (−6.81) | (−7.95) | (−4.54) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 2480 | 2480 | 2480 |

| R2 | 0.258 | 0.256 | 0.257 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample | Eastern Provinces | Western Provinces | |

| Firmcompte | Firmcompte | Firmcompte | |

| InSubs | 0.127 *** | 0.191 *** | 0.104 * |

| (3.11) | (5.74) | (1.75) | |

| elecprice | 2.471 *** | 3.797 *** | 2.326 |

| (2.83) | (5.45) | (1.63) | |

| InSubs × elecprice | −0.144 *** | −0.225 *** | −0.133 |

| (−2.68) | (−5.32) | (−1.46) | |

| Constant | −5.514 *** | −18.60 *** | −6.501 *** |

| (−2.71) | (−3.18) | (−2.65) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 2480 | 1450 | 244 |

| R2 | 0.490 | 0.419 | 0.433 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, L. Government Subsidies and the Competitiveness of Energy Storage Enterprises: The Moderating Effect of Electricity Price. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10789. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310789

Zhao M, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Luo L. Government Subsidies and the Competitiveness of Energy Storage Enterprises: The Moderating Effect of Electricity Price. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10789. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310789

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Manli, Xinhua Zhang, Qianqian Zhang, and Li Luo. 2025. "Government Subsidies and the Competitiveness of Energy Storage Enterprises: The Moderating Effect of Electricity Price" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10789. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310789

APA StyleZhao, M., Zhang, X., Zhang, Q., & Luo, L. (2025). Government Subsidies and the Competitiveness of Energy Storage Enterprises: The Moderating Effect of Electricity Price. Sustainability, 17(23), 10789. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310789