1. Introduction

The widespread deployment of wireless sensor networks (WSNs) has become a cornerstone of the Internet of Things (IoT), enabling deep integration and application across various societal domains [

1,

2,

3]. A particularly impactful application is in the domain of smart agriculture, where the deployment of diverse sensor nodes across farmlands allows for the real-time acquisition of fine-grained operational data [

4,

5,

6]. This capability is crucial to enabling the dynamic monitoring of crop growth statuses and providing a scientific basis for precision management practices, such as targeted fertilization and irrigation.

However, efficiently collecting data from sensor nodes dispersed across vast agricultural fields remains a significant challenge, particularly in remote areas with limited network infrastructure [

7,

8]. To address this, employing mobile devices to assist in data collection has emerged as a viable strategy. Among the available mobile platforms, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) offer a uniquely flexible, efficient, and cost-effective solution for data gathering from WSNs compared with their ground-based counterparts [

9,

10].

The application of UAVs for data acquisition has given rise to a rich body of literature focused on optimization. Depending on mission objectives, research efforts have targeted distinct performance metrics, such as minimizing task completion time, system energy consumption, the Age of Information (AoI), and network coverage quality [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

A primary branch of this research field focuses on optimizing the data collection trajectory for a single UAV. For instance, in agricultural scenarios, the authors in [

16] employ a grid-based method to partition the area and select cluster heads for data aggregation, subsequently utilizing a Competitive Double Deep Q-Network (Competitive Double DQN) to optimize the UAV’s traversal path, thereby improving both collection efficiency and coverage quality. Addressing a similar agricultural setting, the study in [

17] extends this by optimizing MAC layer mechanisms, introducing packet prioritization and timeslot allocation schemes to achieve more efficient resource utilization. In more complex urban environments, researchers in [

18] investigate UAV data collection in a 3D space with signal jammers and obstacles, leveraging a Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN) to enhance the UAV’s task execution capabilities.

As IoT deployment scenarios expand, single-UAV systems face inherent limitations in efficiency and coverage, making cooperative multi-UAV path planning a prominent research hotspot. Exemplifying this trend, the authors of [

19] proposed a multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) framework that integrates Double Deep Q-Network (DDQN), SARSA, and Q-learning algorithms. This hybrid approach enables effective cooperative path planning, leading to notable improvements in data collection efficiency and reductions in system energy consumption. Building upon this, system adaptability was enhanced in [

20] by structuring the operational scene as a three-dimensional vector and introducing a convolutional layer into the DDQN architecture. Notably, these studies are predicated on discrete action spaces, which can constrain UAV maneuverability and limit optimal performance in practical scenarios.

To overcome these limitations, a significant line of research has shifted towards multi-agent optimization within continuous action spaces. For example, the work in [

21] addresses the IoT data collection task by proposing the MCDDPG-EPM algorithm, based on the Multi-Critic Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (MCDDPG) framework, to minimize path length under battery constraints. Similarly, the authors in [

22] focus on optimizing the AoI by employing an improved Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm to fine-tune an MATD3 neural network.

Furthermore, to transcend the limitations of conventional reinforcement learning, architectural innovations have been introduced. Hierarchical reinforcement learning (HRL), for instance, has tackled long-term path planning for UAVs requiring mid-mission charging by decoupling macro-level tasks from micro-level actions [

23]. In parallel, attention mechanisms have been integrated into network architectures, empowering models to dynamically focus on salient information, proving effective for scheduling multi-UAV systems in dynamic scenarios [

24]. Collectively, these advancements underscore that innovation within the algorithmic architecture itself is a key avenue for enhancing MARL systems’ capabilities.

Recent advances have also explored Transformer-enhanced MARL frameworks for UAV applications. For example, self-attention mechanisms have been employed to coordinate multi-UAV air transportation and navigation tasks by capturing long-range inter-agent dependencies, resulting in more globally coherent route planning [

25]. Similarly, Transformer-based critics have been applied to UAV-enabled communication networks, where attention-driven policies improve channel allocation efficiency and training stability [

26]. These developments highlight a growing trend toward leveraging attention architectures to strengthen the representational capacity of MARL models.

Despite these advances, many widely used CTDE-based algorithms—such as MADDPG, MATD3, and MASAC—still depend on centralized critics that encode the joint state–action space via simple feature concatenation. Such a representation is fundamentally limited in its ability to model complex inter-agent relationships, often leading to unstable training, slow convergence, and suboptimal performance as the number of UAVs or sensor nodes increases. Motivated by these limitations, this work introduces a Transformer-based centralized critic that uses multi-head self-attention to explicitly capture inter-agent interactions, thereby enabling more expressive Q-value estimation, faster convergence, and improved scalability.

Building on the foregoing discussion, this paper addresses the challenge of cooperative data collection from IoT sensor nodes using a multi-UAV system for agricultural applications. The primary contributions of this work are as follows:

This paper proposes a framework based on the MATRS algorithm designed for multi-UAV collaborative data collection. The multi-agent data collection problem is modeled as a decentralized Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (Dec-POMDP), and a solution based on MASAC (Multi-Agent Soft Actor–Critic) is presented. The framework adopts a Centralized Training with Decentralized Execution (CTDE) paradigm, which ensures autonomous decision-making capability for each UAV while simultaneously enabling the learning of efficient global collaborative strategies.

Integration of a Transformer architecture to enhance inter-agent collaboration. Diverging from conventional coordination mechanisms, this work incorporates a Transformer encoder within the critic network of the MASAC framework. By leveraging the self-attention mechanism, our approach enables the system to dynamically weight the importance of information from different agents, effectively capturing long-range, global spatiotemporal dependencies. This facilitates a more sophisticated and far-sighted form of cooperative decision making, particularly in scheduling data collection tasks among UAVs.

Comprehensive experimental validation and scalability analysis in a smart agriculture scenario. We conducted rigorous experiments in a simulated agricultural environment, benchmarking the proposed MATRS algorithm against several state-of-the-art baseline methods. The empirical results demonstrate that MATRS achieves superior performance, exhibiting a significantly higher data collection rate and a shorter mission completion time. Furthermore, by evaluating the algorithm across various problem scales, we confirm its robustness and excellent scalability.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In

Section 2, we outline the system model and provide the formal problem formulation.

Section 3 details the design and implementation of the proposed MATRS algorithm. In

Section 4, we present the simulation experiments conducted to evaluate the UAV data collection paths and discuss the corresponding results. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. System Model

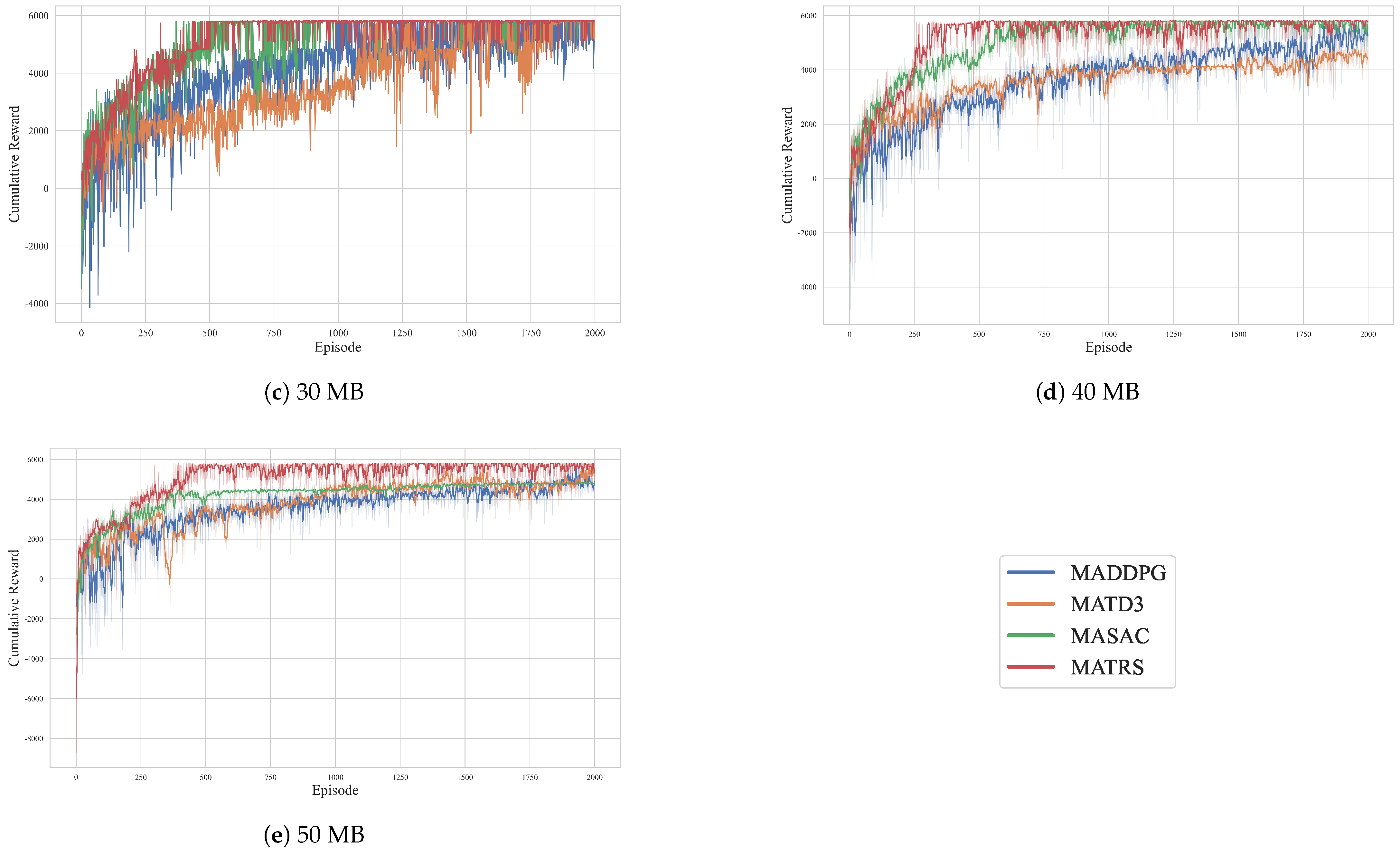

We consider a multi-UAV cooperative data collection scenario, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The operational environment is defined as a three-dimensional agricultural area of size

.

Within this area, a set of N static sensor nodes is deployed. The position of each sensor node is fixed and known, with its coordinates given by .

The data collection task is executed by a fleet of K homogeneous UAVs, denoted by the set . To simplify the analysis and focus on horizontal trajectory optimization, all UAVs are assumed to maintain a constant flight altitude of H. This altitude is typically chosen to balance communication coverage area with signal quality and to ensure safe clearance above crops.

The total mission duration is denoted by T (in seconds). For the purpose of decision making, we discretize this period into a sequence of L time slots, where each slot has a uniform duration of (in seconds). The set of time slots is thus defined as , with .

In this discrete-time model, the instantaneous position of UAV

in any time slot

is uniquely determined by its two-dimensional horizontal coordinates,

. Consequently, the individual trajectory of UAV

throughout the entire mission, denoted by

, can be defined as the sequence of its positions in each time slot:

Correspondingly, the joint trajectory of the entire UAV fleet,

, is the collection of all individual trajectories:

2.1. UAV Energy Consumption Model

The total energy consumption during the mission comprises two primary components: the propulsion energy required for flight and the communication energy for data transmission with the sensor nodes. In the data collection task we investigate, a communication link is established only when the received signal power between a UAV and a sensor node exceeds a predefined threshold. During these brief data exchange intervals, the energy consumed for communication is negligible compared with the energy required for propulsion.

Therefore, in modeling the mission’s energy consumption, we focus exclusively on the dominant component: the flight energy. Following the widely used rotary-wing UAV energy model proposed by Zeng et al. [

27], the power consumption

(in Watts) for a UAV flying at a speed

v (in m/s) can be modeled as

The parameters in Equation (

3) are defined as follows:

(Watts) and

(Watts) are constants representing the blade profile power and induced power in hovering state, respectively;

(m/s) is the tip speed of the rotor blade;

(m/s) is the mean rotor-induced velocity in hover;

d and

denote the fuselage drag ratio and rotor solidity; and

(kg/m

3) and

A (m

2) represent the air density and the rotor disc area, respectively.

Based on this power model, the total flight energy consumption

(in kJ) of UAV

over the entire mission can be calculated by summing its power consumption in each time slot:

where

is the speed of UAV

in time slot

t. The total energy consumption of the entire UAV fleet,

(kJ), is the sum of the individual energy consumption of all UAVs:

Furthermore, to ensure that all UAVs can successfully complete the mission, each UAV must adhere to its own energy constraint. Assuming that each UAV starts with an initial energy budget of

(in kJ), the cumulative energy consumed by any UAV

must not exceed this budget at any point during the mission. This constraint can be formally expressed as follows: For any UAV

k and any time slot

, the following inequality must hold:

2.2. Channel Model

In agricultural data collection scenarios, the wireless channel between a UAV and a sensor node is highly dependent on the type and height of the crops. For analytical tractability, we base our channel model on the Line-of-Sight (LoS) propagation assumption, which is generally valid for environments with low-stalk crops or where sensor modules are elevated above the vegetation canopy.

To better reflect the practical conditions of an agricultural field, we augment the standard free-space path loss model with an additional, constant attenuation factor,

, to account for the signal loss caused by vegetation. Consequently, the average path loss

between UAV

k at position

and sensor node

n is given by the modified Friis equation in decibels:

where

(meters) is the Euclidean distance between the UAV and the sensor node in time slot

t,

f (Hz) is the carrier frequency,

c (m/s) is the speed of light, and

(dB) is the additional loss component due to vegetation.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this model. In environments with dense or tall crops (e.g., cornfields), signal propagation can be significantly affected by scattering, diffraction, and absorption, leading to complex Non-Line-of-Sight (NLoS) conditions. While our inclusion of provides a first-order approximation, a more sophisticated, probabilistic channel model might be required for such scenarios. However, for the scope of this work, the augmented LoS model provides a reasonable and computationally tractable basis for trajectory optimization, particularly in typical precision-agriculture deployment that involves low-stalk crops or utilizes elevated sensor modules to maintain approximate LoS connectivity.

Building upon the path loss model from Equation (

7), the received signal power

(in dBm) at the UAV

k from sensor node

n in time slot

t can be expressed as

where

(in dBm) is the constant transmission power of the sensor nodes. We adopt a transmission power of

dBm, as this choice is not only consistent with prior studies [

21,

27] but also represents a typical power level for nodes in modern wireless sensor networks.

In practice, a stable communication link can only be established if the received signal power is above the UAV’s minimum reception sensitivity. To model this requirement, we introduce a reception power threshold,

(in dBm). Therefore, for UAV

k to effectively communicate with sensor node

n, its received power must satisfy the following constraint:

This constraint implies that data collection is only feasible when a UAV is sufficiently close to a sensor node, such that the path loss is below a certain maximum. If this condition is not met, the channel between them is considered unavailable, and the data rate is effectively zero.

Assuming that the channel is subject to Additive White Gaussian Noise (AWGN) with constant power spectral density, resulting in a noise power of

(in Watts), the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)

at UAV

k from sensor node

n can be expressed as

where

is the received power in linear scale (Watts), converted from the logarithmic scale (dBm) representation

.

Finally, according to the Shannon–Hartley theorem, the maximum achievable data rate

(in bits per second) over a channel with bandwidth

B (in Hz) is given by

2.3. Problem Formulation

Based on the system model detailed above, the central task of this research study can be formulated as a multi-objective optimization problem (MOOP). The goal is to jointly optimize the trajectories of the UAV fleet, , and the mission completion time, , to simultaneously maximize the total data throughput while minimizing the completion time, all subject to the operational constraints previously defined.

The two conflicting objectives are formally stated as follows:

(Objective 1: Maximize Total Throughput)

(Objective 2: Minimize Completion Time)

5. Conclusions

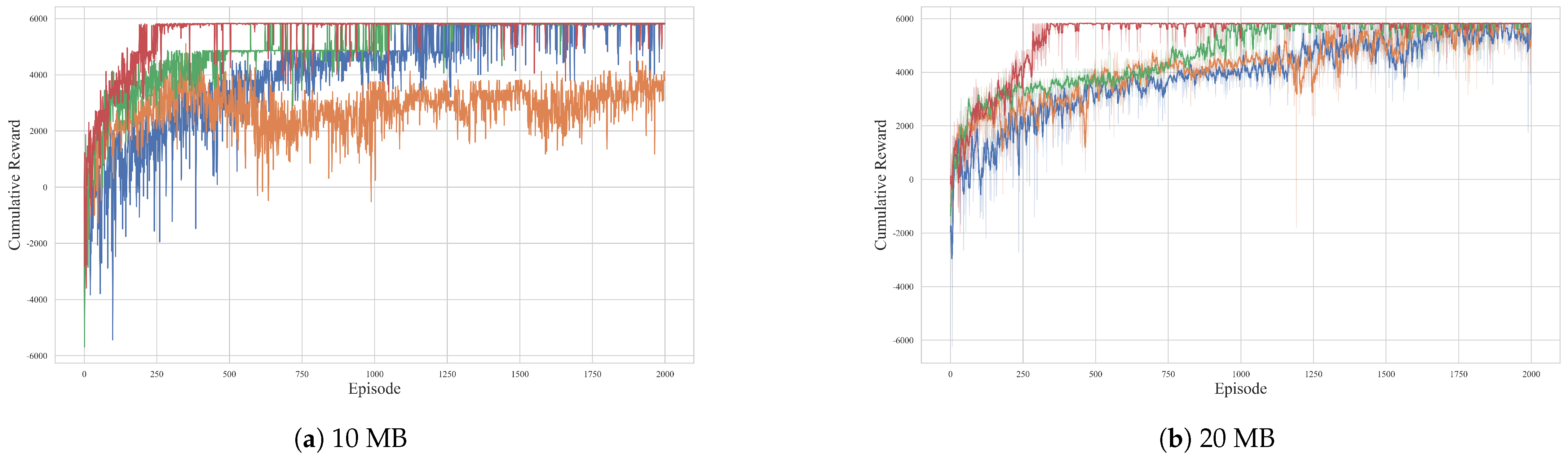

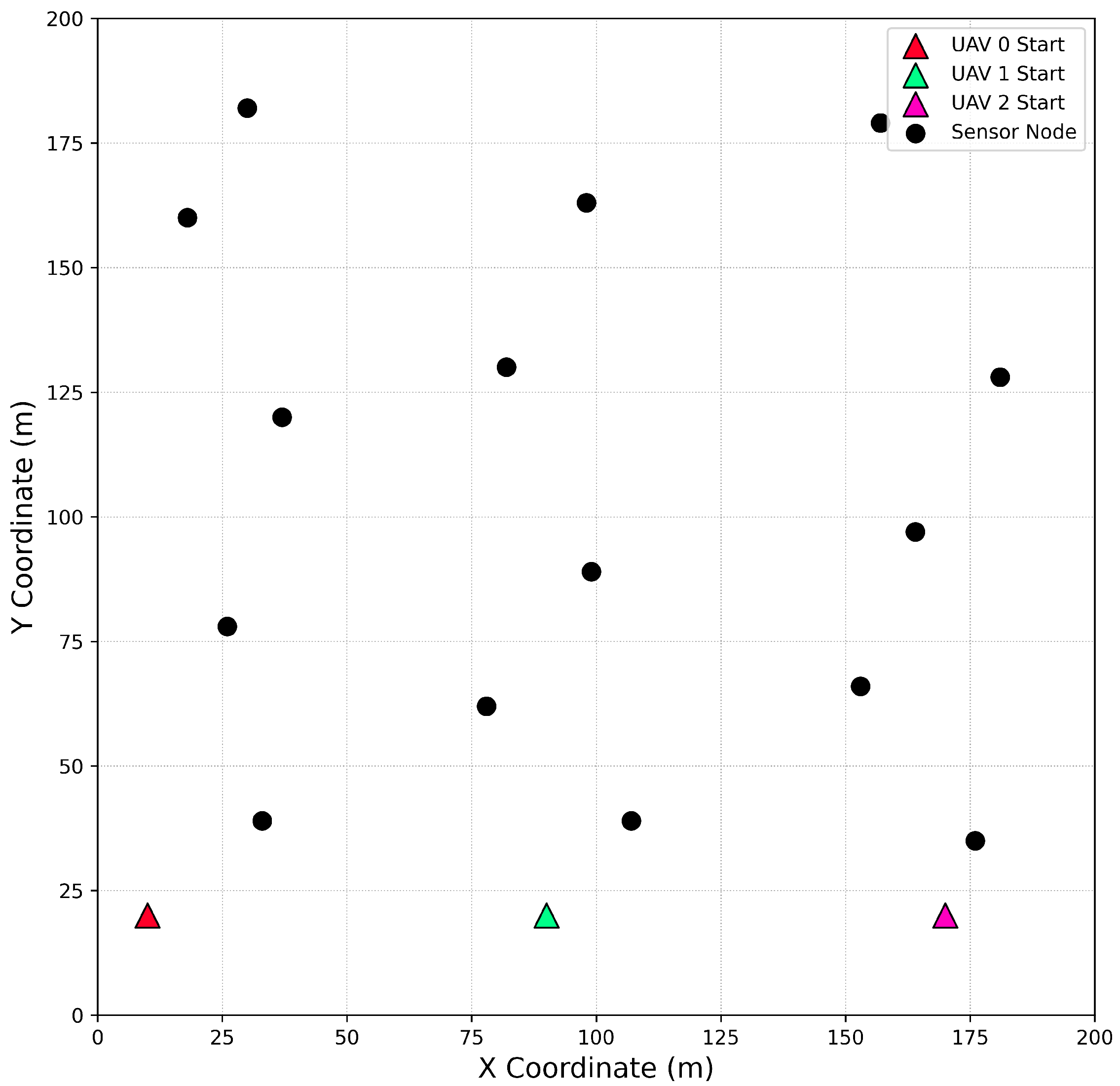

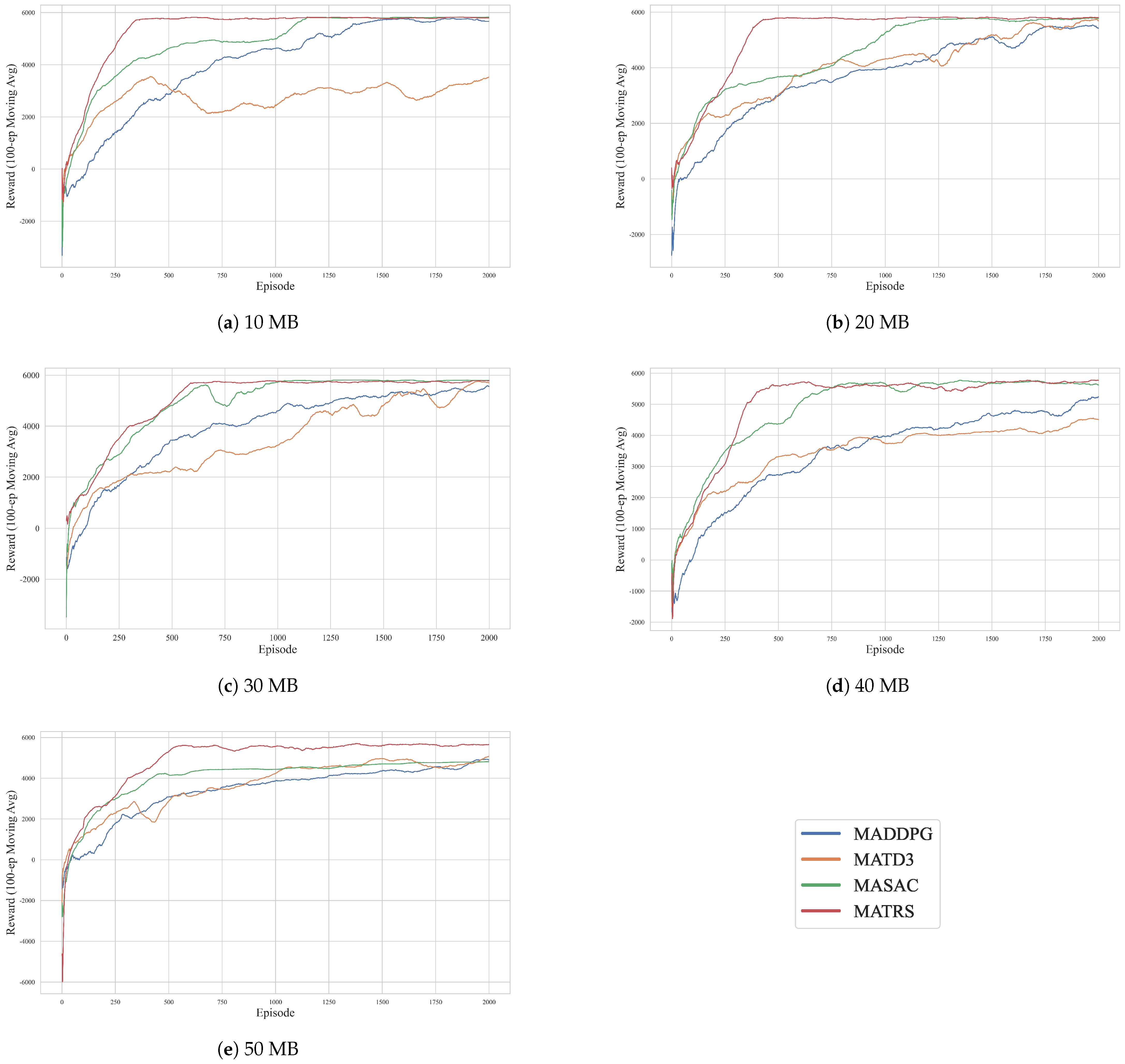

In this paper, we addressed the complex challenge of cooperative path planning for multiple UAVs in agricultural data collection tasks, proposing a novel multi-agent reinforcement learning algorithm named MATRS. Our approach is built upon the Centralized Training with Decentralized Execution paradigm and integrates a SAC framework to ensure efficient exploration and policy stability. The core innovation of MATRS lies in its centralized critic architecture, which replaces conventional MLP networks with a Transformer-based encoder. This design leverages the self-attention mechanism to effectively model the complex inter-agent dependencies and accurately evaluate the joint action–value function, which is critical to learning sophisticated cooperative strategies.

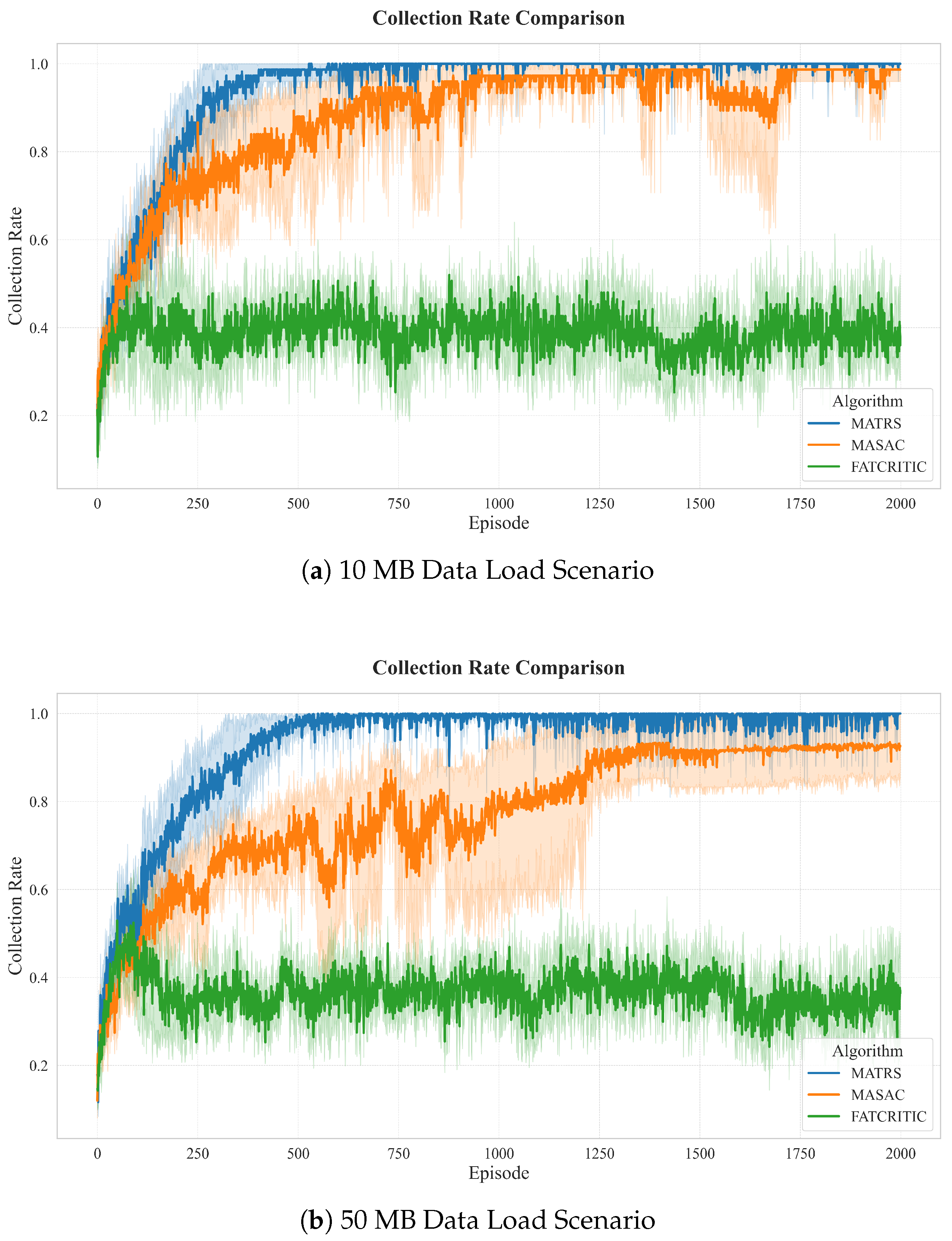

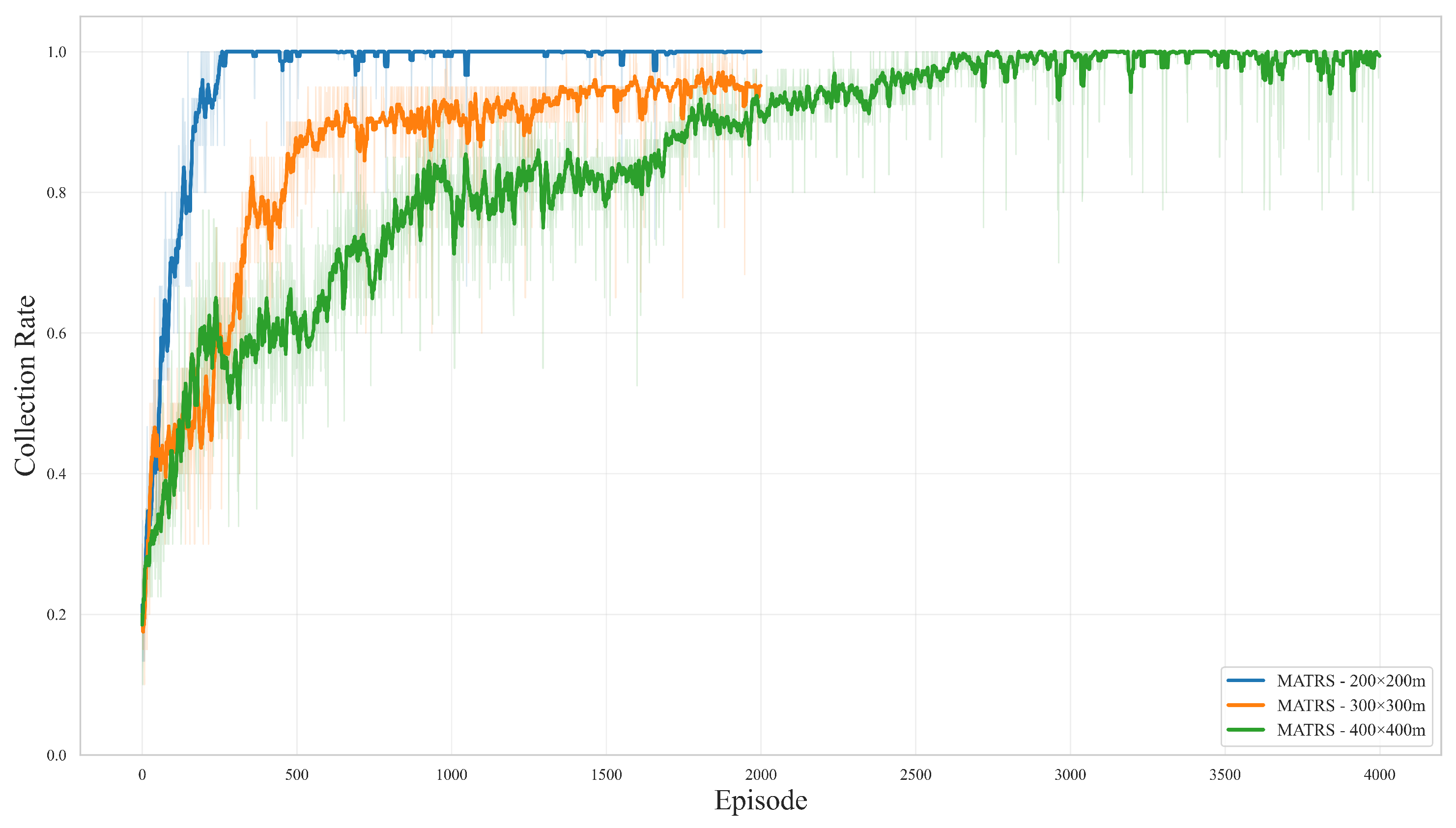

Through a series of comprehensive simulation experiments, we have demonstrated the significant performance benefits and promising scalability of MATRS. Compared with established baseline algorithms such as MADDPG, MATD3, and MASAC, MATRS consistently exhibited faster convergence and greater stability across various data load scenarios. This superior efficiency is starkly highlighted when comparing MATRS with MASAC, where across all five data load scenarios, MATRS reduced the steps required for task completion by 10% to 30%. Furthermore, the visualization of the final trajectories provided compelling evidence of an emergent and efficient “task-space partitioning” strategy, where the UAV swarm autonomously divides the mission area for conflict-free coverage. This intelligent cooperative behavior, enabled by the powerful representation capacity of the Transformer critic, underscores the algorithm’s ability to solve complex coordination problems. Finally, scalability tests in larger and more complex environments confirmed the robustness and promising generalization capabilities of the proposed framework.

However, we acknowledge the limitations of this study. Our validation is currently confined to simulated environments, and the framework was tested using a homogeneous swarm of UAVs. These limitations motivate our primary directions for future work. In future work, we plan to validate the proposed algorithm in real-world scenarios to further assess its practical effectiveness and robustness. In addition, we will extend the MATRS framework to applications involving heterogeneous agents, where coordination among UAVs with different capabilities poses new challenges. Moreover, we plan to enhance the framework by incorporating more realistic constraints, such as ensuring Quality of Service (QoS), optimizing for Age of Information, and designing intelligent UAV recharging strategies.

The capabilities demonstrated by MATRS hold significant practical implications for the advancement of precision agriculture. The efficient coverage strategies are applicable to automating crop surveillance, where a swarm of UAVs can autonomously gather data to identify early indicators of crop distress—such as disease, water deficits, or nutrient imbalances—across vast agricultural expanses. In the context of irrigation management, the MATRS framework can empower a UAV fleet to perform rapid and systematic soil moisture mapping, enabling data-driven water resource management that optimizes usage and enhances crop yields. By automating and optimizing these critical data acquisition tasks, our framework serves as a foundational component for developing more scalable, responsive, and intelligent agricultural management systems.