Abstract

Oral diseases pose a major public health challenge, especially in low-income countries where dental care is limited due to high costs. In this context, phytotherapy has gained attention as a complementary approach due to its bacteriostatic, anti-inflammatory, healing, and analgesic properties. These therapeutic effects are mainly attributed to plant-derived bioactive metabolites, which interact with cellular structures, especially the plasma membrane, to modulate inflammation, stimulate tissue regeneration, and support antimicrobial defense. This review systematically examined the scientific literature to identify Latin American medicinal plants with therapeutic potential in dentistry. Based on their clinical and ethnobotanical applications, the analysis focused on species with anti-inflammatory, healing, analgesic, and relaxing effects, particularly in conditions such as dental pain, gingivitis, and periodontitis. Given the close relationship between pain, inflammation, and periodontal disease, these conditions cannot be studied in isolation. Gingivitis and periodontitis often present with painful symptoms and inflammatory responses that overlap with mechanisms of tissue damage and repair. Therefore, broadening the scope of this review allows for a more comprehensive understanding of how Latin American medicinal plants can contribute not only to pain relief but also to periodontal health, inflammation control, and wound healing. Fifty plant species were identified. Among these, 35 exhibited anti-inflammatory activity, 28 had healing properties, 20 showed analgesic effects, and 12 were associated with relaxing properties. Mexico accounted for the highest proportion of species (60%), followed by Colombia and Peru (54%) and then Brazil (32%). These percentages represent the proportion of plant species reported in studies originating from each country, relative to the total number of species identified in the review. The most studied species were Salvia rosmarinus Spenn. (Lamiaceae), Moringa oleifera Lam. (Moringaceae), Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. (Asphodelaceae), and Ocimum basilicum L. (Lamiaceae). Latin American medicinal plants demonstrate strong potential not only in dental therapy but also in the management of periodontal inflammation and oral diseases. However, further research and clinical validation are needed to ensure their safe integration into conventional treatments.

1. Introduction

Oral diseases constitute a major global public health concern due to their widespread prevalence and the substantial costs associated with their treatment. These conditions include dental caries, periodontal disease, congenital anomalies such as cleft lip and palate, dental trauma, and hereditary disorders, many of which are strongly influenced by socioeconomic determinants like poverty, limited access to healthcare services, school dropout, and harmful habits such as tobacco use and inadequate nutrition [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), these diseases, along with oral and pharyngeal cancer, remain highly prevalent in industrialized countries and disproportionately affect low-income populations with restricted access to dental care [1]. The economic burden is considerable, as expenditures on oral healthcare account for approximately 5% to 10% of total health costs in various countries [2].

In response to these challenges, interest has grown in complementary and alternative strategies for oral healthcare. Indigenous communities have traditionally used medicinal plants to treat various ailments, including oral conditions [3]. Their bioactive compounds interact with cellular structures, particularly the plasma membrane, helping to regulate inflammation, stimulate tissue regeneration, and enhance antimicrobial defenses. Phytotherapy has demonstrated bacteriostatic, anti-inflammatory, wound-healing, and analgesic effects, suggesting its potential as an adjunct in dental treatment protocols [4].

Despite these promising properties, most research has focused on plant species used in Europe and Asia [5]. Although rich in biodiversity and cultural knowledge of plant-based remedies for oral health, Latin America remains underrepresented in the scientific literature [6]. A systematic review of Latin American species is needed to fill this gap and provide a structured overview of their therapeutic potential in dentistry. Therefore, this review aims to identify, analyze, and highlight the relevance of medicinal plants native to Latin America in the prevention and management of oral diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

This review followed the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility [7]. Although no formal protocol was registered in platforms such as OSF or INPLASY, the review adhered to the core principles of systematic literature mapping.

A systematic literature search was conducted to identify and analyze Latin American medicinal plants with therapeutic potential in dental health. The search was performed in specialized scientific databases to ensure access to peer-reviewed and reliable sources. The consulted databases included Scielo, PubMed, Revista de Salud Pública del Paraguay, RCOE, Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia, REDEL, Revista Granmense de Desarrollo Local, Revista Odontológica Mexicana, Farmacia Profesional, Farmacia Clínica, and Avances en Odontoestomatología. Additionally, Google Scholar and ResearchGate were used to broaden the scope of the literature search.

The complete search strategies, including search strings, date ranges, language limits, and the number of records retrieved from each database, are provided in Table S1 (Supplementary Materials) for transparency and reproducibility.

In the case of Google Scholar, the search yielded a considerably high number of records (over 6000). However, this result reflects the broad and unspecific nature of the platform, which includes duplicated literature, non-relevant documents, and sources of variable quality. For this reason, not all retrieved records were reviewed; instead, the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were rigorously applied. Through this process, only articles pertinent to the review’s objective were selected, ensuring a systematic and transparent screening while acknowledging the inherent limitations of Google Scholar as a search engine.

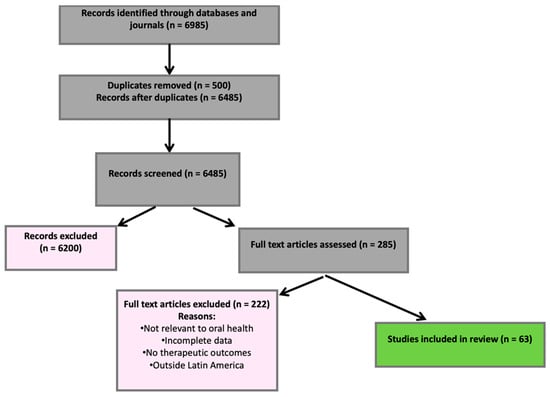

The literature search and screening process are summarized in Figure 1, following the PRISMA-ScR guidelines for scoping reviews. The search strategy included the following keywords: “Dental pain,” “Gingivitis,” “Periodontitis,” “Periodontal inflammation,” “Wound healing,” and “Latin American medicinal plants.”

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the identification and selection of studies.

Original research articles, literature reviews, and academic theses published between 2000 and 2025 in Spanish, English, or Portuguese were included. Eligible documents had to address the use of medicinal plants, phytotherapy, or herbal medicine in the dental field, covering aspects such as oral health, dental pain management, gingivitis, periodontitis, inflammatory processes, and wound healing of oral tissues. Only studies conducted in Latin American countries or including relevant applications in this region were considered. Conversely, reports unrelated to dentistry, even if they mentioned medicinal plants, were excluded, as well as grey literature without full-text access or peer review, duplicate articles identified through a reference manager and manual verification, and documents that did not provide data related to the therapeutic effects of interest (anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, or healing) in oral health, as well as studies conducted outside the geographical scope of interest (Latin America).

All retrieved references from the different databases were exported in RIS format and imported into the reference manager Mendeley. The software’s duplicate detection tool was applied, followed by manual verification, to ensure the removal of duplicate records. This deduplication process reduced the total number of references before the screening stage.

A total of 6985 records were identified across all databases and journals. After removing 500 duplicates using Mendeley and manual verification, 6485 unique records remained. 6200 were excluded during the title and abstract screening stage because they did not meet the eligibility criteria. A total of 285 articles were assessed in full text, of which 222 were excluded due to reasons such as lack of relevance to oral health, incomplete data, absence of therapeutic outcomes of interest, or failure to correspond to the geographical scope of Latin America. Ultimately, 63 studies met all the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. The selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram (Figure 1).

Records were identified through databases and journals (n = 6985). After removing duplicates (n = 500), 6485 records were screened, and 6200 were excluded. A total of 285 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility; 222 were excluded (not relevant to oral health, incomplete data, no therapeutic outcomes, or outside Latin America). Sixty-three studies were included in the final review.

In addition, a brief appraisal of evidence quality and study type was conducted to classify all included sources. In line with the reviewer’s recommendation, peer-reviewed clinical trials, in vivo/in vitro studies, and systematic reviews were prioritized, while reports and institutional documents were categorized as grey literature. Although a total of 63 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review, a focused subset of 36 studies, selected based on methodological quality, relevance to dental applications, and completeness of outcome data, was appraised in greater detail.

This approach allowed us to emphasize higher-quality evidence without diminishing the relevance of the remaining studies. The detailed classification of this subset is provided in Supplementary Table S2, which summarizes the evidence level and main characteristics of the 36 references.

After applying these filters, 63 relevant articles were selected, documenting 50 plant species native to Latin America with potential applications in dentistry. The analysis revealed that Mexico, Colombia, and Peru exhibited the greatest diversity of reported species, with propolis, rosemary, moringa, aloe vera, and basil being the most frequently studied for their therapeutic benefits. A detailed list of all 50 plant species and their reported uses is provided in Table 5. In addition, a small number of species not originally native to Latin America (e.g., Zingiber officinale, Ocimum sanctum) were retained and explicitly labeled as external comparators. These plants were included in the synthesis for contextual purposes; however, it is essential to note that they are also cultivated and widely used in Latin America, as documented in the literature, which justifies their inclusion in the review.

Each plant demonstrated specific effects on oral health:

- Propolis (resinous product of Apis mellifera L., Apidae): Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity, effective against gingivitis and periodontitis.

- Salvia rosmarinus Spenn. (Lamiaceae): Used for pain relief and wound healing in the oral cavity.

- Moringa (Moringa oleifera): Anti-inflammatory effects beneficial to oral tissues.

- Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. (Asphodelaceae) and Ocimum basilicum L. (Lamiaceae): Known for healing and antibacterial properties relevant to disease prevention and oral care.

This review was based entirely on previously published literature and did not involve any new experiments or interventions involving human or animal subjects.

3. Pain and Its Relationship with Dentistry

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as a distressing sensory and emotional state resulting from actual or perceived tissue damage. Beyond its physiological component, pain impacts multiple aspects of daily life, including work, family, and social functioning, ultimately reducing overall well-being. Since pain is inherently subjective, it must be evaluated through self-reported measures, as no absolute objective indicators exist for its confirmation [8].

Pain perception varies significantly according to its etiology, intensity, and each individual’s pain threshold. Although it cannot be measured precisely, standardized assessment tools such as the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) allow for approximate evaluation and improved clinical management. Only Colombia and Australia have formally included the VAS in their national clinical protocols [8].

Oral pain is one of the most frequent discomforts in the facial and cervical regions, commonly associated with pulpal pain due to the dental pulp’s sensitivity to harmful or infectious stimuli [9]. This form of pain is classified as deep somatic, typically characterized by a diffuse, dull, and throbbing quality. Given the extensive innervation of oral structures, particularly by the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V), oral pain is often intense and may radiate toward the ears, eyes, or adjacent areas. This complexity underscores the need for pain management strategies that extend beyond conventional pharmacological methods.

Medicinal plants have emerged as promising alternatives for managing dental pain in this context. Various bioactive compounds found in Salvia rosmarinus Spenn. (Lamiaceae), Moringa oleifera Lam. (Moringaceae), and Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. (Asphodelaceae) have shown analgesic effects by modulating inflammation and regulating nociceptive pathways. These phytotherapeutic agents interact with pain mediators such as prostaglandins, potentially reducing the intensity of orofacial pain [10].

The IASP also emphasizes that oral pain is a sensory and emotional reaction to real or perceived harm affecting the orofacial region [8]. As scientific evidence expands, incorporating natural compounds into dental pain protocols may offer effective alternatives that reduce dependence on synthetic analgesics and help minimize their adverse effects.

4. Causes of Dental Pain

Dental pain can originate from various pathological conditions affecting the oral cavity, including infections, trauma, odontalgia, somatic pain involving the mucosa and periodontium, nutritional deficiencies (such as vitamin shortages), and autoimmune diseases [11]. These conditions compromise the structural integrity of dental tissues and support systems, resulting in different types of pain depending on the location and pathophysiology of the lesion.

Physiologically, dental pain is classified as either somatic or neuropathic. Somatic pain is the most common, affecting the gingiva, periodontium, blood vessels, and maxillary bones. It is usually throbbing and localized [12]. Neuropathic pain, by contrast, arises from direct injury to nerve fibers and is often described as diffuse and radiating. A typical example is pulpal pain when the lesion reaches the neurovascular bundle within the dental pulp [13].

An inflammatory response is triggered when oral tissue damage occurs, activating nociceptive pathways. The inflammatory response begins with the release of mediators such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and bradykinin, which sensitize nerve fibers and facilitate pain transmission [12]. Neuropeptides such as substance P and CGRP further promote the release of histamine and cytokines, intensifying the pain experience [12]. The regulation of these inflammatory mediators is a key target of emerging therapeutic strategies, including the use of natural compounds with analgesic potential; however, further research is needed to validate their clinical effectiveness.

Pain is considered chronic when it is persistent and acute when it is sudden and short-term. Despite being subjective, pain intensity can be estimated using tools such as the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), which rates perception on a scale of 1 to 10 [12].

Beyond biological triggers, psychological factors such as stress, anxiety, and past pain experiences can significantly influence pain perception and treatment outcomes [14]. Furthermore, dental pain can undermine the integrity of enamel and dentin, increasing the risk of pulpitis, a severe inflammation caused by trauma, fracture, or infection.

To further strengthen this clinical framework, it is essential to note that several studies in periodontology and implantology have already employed standardized pain assessment scales. For example, one trial assessed postoperative discomfort, dentin hypersensitivity, and patient-reported pain during different periodontal procedures using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). Patients marked their pain and sensitivity on the VAS, enabling comparisons across scaling and root planing (SRP), modified Widman flap (MWF), osseous flap (OF), and gingivectomy (GV). Pain scores were significantly higher after OF and GV compared with SRP and MWF, and all surgical procedures caused more dentin hypersensitivity than non-surgical therapy [15].

Additionally, larger clinical investigations have incorporated the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) to assess pain intensity. In one study of 253 patients undergoing 330 periodontal or implant surgeries, most participants reported mild pain (70.3%), while 25.5% had moderate and 4.2% severe pain. Advanced implant surgeries showed the highest median NRS scores (4.0), while open flap debridement had the lowest (1.0). Pain duration (median = 2 days) and analgesic use were positively correlated with NRS values, and more extensive or complex surgeries, as well as higher anesthetic volumes, were associated with greater pain [16].

Table 1 outlines the multifactorial nature of dental pain, which can arise from pulpal lesions and surrounding anatomical structures. For instance, pericoronitis, which often affects erupting third molars, can lead to localized inflammation, pain, and difficulty chewing if left untreated. Similarly, infectious alveolitis resulting from the dislodgement of a blood clot post-extraction exposes the alveolar bone and causes intense, persistent pain that requires clinical management.

Table 1.

Primary Oral Diseases and Their Clinical Approach.

Pain may also stem from sinusitis, particularly when the oral and sinus cavities are connected, allowing oral bacteria to infect the sinus mucosa.

In addition, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders are frequent sources of orofacial pain. Displacement of the articular disk affects mandibular movement, producing symptoms such as jaw pressure, clicking sounds, and difficulty chewing [19].

5. Conventional Pharmacology for Pain Management

The first step involves a thorough clinical evaluation when a patient presents to the dental office with pain or discomfort. This process includes obtaining a comprehensive medical history, identifying potential etiological factors, and assessing contraindications for pharmacological interventions.

In conventional dentistry, pain management typically involves commonly prescribed medications such as acetaminophen (paracetamol), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen and naproxen, and, in more severe cases, opioids or their derivatives. Drug selection is guided by the severity of pain and the patient’s overall medical condition. While effective, these drugs are often associated with adverse effects: NSAIDs may cause gastrointestinal irritation, opioids can lead to sedation and dependency, and excessive intake of paracetamol carries the risk of hepatotoxicity.

Pharmacological strategies in dental pain management rely heavily on cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors, particularly NSAIDs, because they block prostaglandin synthesis and reduce inflammation and pain [22]. However, since prostaglandins also protect the gastric mucosa and regulate renal function, prolonged use of NSAIDs can lead to ulcers, kidney dysfunction, or gastrointestinal bleeding, especially in vulnerable patients.

Although paracetamol is not classified as an NSAID, it inhibits prostaglandin synthesis centrally, offering analgesic and antipyretic effects [22]. While generally safe, overdose may result in liver toxicity, requiring careful dosing. Metamizole is another analgesic option, though its use is restricted due to potential risks such as allergic reactions and hematologic complications like agranulocytosis [22].

In cases where other medications are insufficient, opioids may be prescribed. These drugs bind to specific receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems, providing potent analgesia [22]. However, their use in dentistry remains limited due to the risk of adverse effects, including respiratory depression, sedation, dependence, nausea, and constipation, which require close monitoring.

Additionally, combination analgesics, often including substances like caffeine or sedatives, have been developed to enhance efficacy. Although they can improve pain relief in certain clinical scenarios, their use remains controversial due to concerns about drug interactions and potential side effects [22].

Given these limitations, current research has shifted toward identifying complementary therapies that can enhance pain control while minimizing adverse outcomes. In this context, natural bioactive compounds are gaining relevance, and several studies are evaluating their potential role in modulating dental pain.

6. Use of Medicinal Plants for Reducing Oral Pain

The search for therapeutic alternatives with fewer adverse effects than conventional drugs has fueled a growing interest in medicinal plants. These contain bioactive compounds that promote healing by stimulating the production of collagen and proteoglycans, both of which are essential for tissue regeneration. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 201 countries regulate and use medicinal plants for their therapeutic and nutritional benefits [1].

At the cellular level, the plasma membrane plays a critical role in mediating interactions between plant-derived compounds and human cells. This dynamic structure regulates the passage of molecules between the intracellular and extracellular environments. Surrounding each cell, the extracellular matrix (ECM) supports cell communication and molecular exchange. Structurally, the ECM and the basement membrane (BM) share components such as type IV collagen and polysaccharide elements, which are also found in plant cell walls. This resemblance may enhance the bioavailability of plant-based compounds and improve their therapeutic effects, especially in the oral cavity, where the mucosal barrier facilitates rapid absorption.

Among the most studied plant-derived compounds are flavonoids, which are well-known for their anti-inflammatory activity. These molecules modulate the production of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukins IL-1 and IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), thus reducing inflammation and protecting oral tissues. Recent studies have suggested that flavonoids and other secondary metabolites may modulate inflammatory signaling pathways associated with orofacial pain, which supports the findings of this review.

Despite structural differences, plant and human cells share key biological mechanisms in their membranes that allow for the interaction and transport of proteins, enzymes, and other molecules through specific transport systems. Mechanisms such as exocytosis and endocytosis enable the absorption of plant compounds into oral tissues, allowing their integration into metabolic pathways [23]. This cellular interaction helps explain the reported effects of medicinal plants on pain relief and tissue repair in the oral cavity.

Furthermore, the plant cell wall and the human ECM are similar in regulating molecular exchange and cellular signaling. These functional parallels are particularly relevant to natural medicine, providing insight into how specific plant compounds can interact with oral mucosal cells to exert therapeutic effects. For example, flavonoids and alkaloids may cross these cellular barriers via facilitated diffusion or active transport mechanisms that could explain their growing interest in oral healthcare [23]. Overall, the structural and functional interaction between plant and human cells supports the therapeutic potential of natural compounds in oral health. Nonetheless, further clinical studies are needed to determine the full extent of their effects on pain modulation and tissue regeneration.

7. Dental Products

Dental research has increasingly explored the use of natural products as alternatives to conventional treatments, aiming to mitigate the adverse effects of antibiotics and chemical antiseptics. According to the World Health Assembly, traditional medicine plays a fundamental role in managing oral diseases in many developing countries [1]. In this context, several studies have evaluated the impact of medicinal plants on oral health, highlighting their antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and wound-healing properties.

One key study demonstrated that mouth rinses containing 5% Echinacea purpurea (L.) Moench (Asteraceae), Commiphora myrrha (Nees) Engl. (Burseraceae), and Matricaria chamomilla L. (Asteraceae) significantly reduced bacterial plaque and gingival bleeding. Similarly, Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. (Asphodelaceae), and grapefruit seed extract rinses showed superior efficacy in controlling gingivitis compared to distilled water. Additionally, 1% Sage extract, recognized for its anti-plaque properties, has been successfully used as a rinse to enhance oral hygiene. In endodontic treatments, 3.3% Carica papaya oil has been shown to enhance dental permeability and exert notable antiseptic effects. Likewise, Matricaria chamomilla L. (Asteraceae) (syn. Matricaria recutita L.)

Extracts have demonstrated outcomes comparable to those of chlorhexidine, effectively reducing inflammation and controlling pathogenic bacteria. In animal models, Propolis—a resinous product of Apis mellifera L. (Apidae)—has also exhibited wound-healing activity without adverse effects [22].

In line with these findings, additional randomized clinical trials provide further support for the efficacy of herbal formulations. For instance, in a randomized clinical trial involving 70 hospitalized patients (mean age, 44.9 years; 67.1% male), Echinacea purpurea (L.) was compared with chlorhexidine and a control group for 4 days. Both echinacea and chlorhexidine significantly reduced oral microbial flora compared with the control, supporting echinacea as a viable alternative [24]. Similarly, a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial including 30 orthodontic patients (10–40 years old) demonstrated that a 1% Matricaria chamomilla L. (Asteraceae) mouthwash reduced plaque (−25.6%) and gingival bleeding (−29.9%) comparably to 0.12% chlorhexidine, while the placebo showed increased indices. Matricaria chamomilla L. (Asteraceae) was well tolerated without adverse effects, reinforcing its role as a safe herbal alternative in the management of gingivitis [25].

From an ethnobotanical perspective, indigenous communities in Colombia’s Atrato Medio Antioqueño region have reported using species such as Piper, Manekia, and Schradera to strengthen teeth, prevent caries, and control periodontal pockets. Chewing these plants releases bioactive metabolites with antimicrobial potential [23]. The incorporation of these traditional practices reinforces the potential therapeutic role of plant-based compounds in modulating oral health, aligning with the findings presented in this review.

Other investigations have evaluated the use of phytotherapeutic compounds in treating gingivitis and periodontitis. For instance, Solanum lycopersicum L. (Solanaceae) (tomato plant) in gel form has shown anti-hemorrhagic and anti-inflammatory effects, while Eucalyptus, incorporated into chewing gum, has reduced plaque accumulation and gingival inflammation [26]. These findings highlight the increasing interest in developing natural formulations as adjunctive therapies to conventional dental protocols.

Moreover, mouthwashes containing various plant extracts have shown promising results. Solanum lycopersicum (tomato plant) in gel form has shown anti-hemorrhagic and anti-inflammatory effects, while Eucalyptus globulus Labill. (Myrtaceae), incorporated into chewing gum, it has been shown to reduce plaque accumulation and gingival inflammation. Likewise, Mangifera indica L. (Anacardiaceae).

Gel has anti-inflammatory and wound-healing properties, offering therapeutic benefits in the management of chronic periodontitis [26].

Finally, a clinical trial conducted on high school students using a Zingiber officinale Roscoe (Zingiberaceae) based mouth rinse showed a significant reduction in plaque and gingival bleeding compared to the control group, in which inflammation levels remained unchanged [27]. While these findings suggest notable therapeutic potential, further research is necessary to standardize formulations, optimize dosage, and assess long-term clinical effectiveness.

8. Mechanism of Action of Plants in Inflammation

Conventional drugs have shown effectiveness in treating inflammatory diseases; however, prolonged use often results in adverse effects such as fluid retention and hypertension. This has increased interest in medicinal plants, whose bioactive compounds provide anti-inflammatory alternatives with a lower risk of side effects. Chronic inflammation, one of the major contributors to global mortality, is commonly managed using NSAIDs and corticosteroids, yet their long-term impact has often been underestimated [27]. The discomfort caused by symptoms such as edema, redness, and functional impairment has driven patients to seek more accessible natural therapies. As a result, interest has grown in studying plant-based bioactive molecules that can modulate inflammatory responses, paving the way for new complementary approaches in pain management [27].

At the biological level, inflammation is an immune response triggered by chemical, biological, or physical stimuli that affect vascularized connective tissues. This process involves the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and plays a central role in maintaining oral health, particularly in chronic conditions such as periodontal disease [27]. Identifying natural compounds that interact with these inflammatory mediators is gaining increasing attention, especially for their potential in pain relief and tissue regeneration [28].

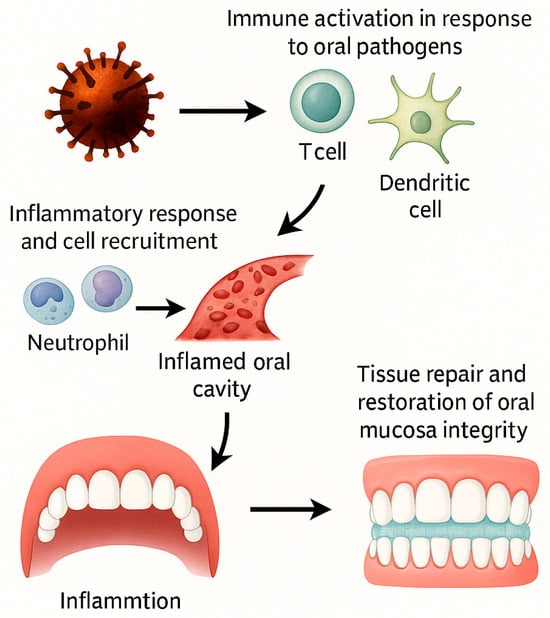

As illustrated in Figure 2, inflammation begins with the release of mediators by mast cells, which promote vascular changes and the recruitment of immune cells to the affected site. These processes initiate an inflammatory cascade that is later regulated by feedback mechanisms, ultimately facilitating wound healing and restoring tissue integrity.

Figure 2.

Inflammatory cascade in oral tissues triggered by natural compounds. Oral pathogens activate immune cells (T cells, dendritic cells), leading to the release of inflammatory mediators that recruit neutrophils and other immune cells to the site of injury. This cascade promotes vascular changes and tissue infiltration, resulting in an inflamed oral cavity. Through feedback mechanisms, the inflammatory process transitions into tissue repair and restoration of oral mucosa integrity. This figure illustrates the dual role of inflammation in both oral pathology and healing, highlighting potential targets for plant-derived bioactive compounds.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit cyclooxygenase 1 and 2 (COX-1 and COX-2). While COX-2 is directly linked to inflammation at the injury site and its inhibition is therapeutically beneficial, COX-1 plays essential physiological roles, such as protecting the gastric mucosa. Therefore, its inhibition may cause adverse effects. These limitations have spurred the search for alternative treatments with fewer risks, encouraging research into plant-based anti-inflammatory compounds [28].

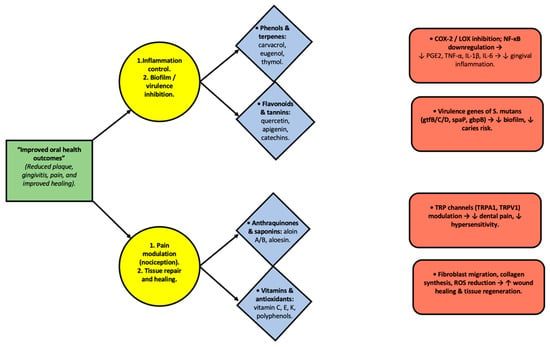

To provide a mechanistic integration of plant bioactives, Figure 3 presents a flowchart mapping plant metabolites to molecular targets and oral outcomes. This schematic illustrates how compounds such as phenols, flavonoids, saponins, and vitamins modulate pathways (e.g., COX/LOX inhibition, NF-κB downregulation, TRP modulation), ultimately leading to improved oral outcomes, including reduced plaque, gingivitis, pain, and enhanced healing.

Figure 3.

Integrative diagram illustrating the relationship between plant-derived metabolites, their molecular targets, and oral health outcomes. Phenols, flavonoids, anthraquinones, saponins, and vitamins act through specific pathways, including COX-2/LOX inhibition, NF-κB downregulation, modulation of Streptococcus mutans virulence genes, TRP channel regulation, and stimulation of fibroblast activity. These interactions contribute to reducing inflammation, inhibiting biofilm formation, modulating nociception, and enhancing wound healing, ultimately leading to improved oral health outcomes. Arrows indicate the direction of interaction and functional flow between bioactive compounds, molecular mechanisms, and oral effects.

Although inflammation is necessary for tissue repair, its dysregulation can extend tissue damage. The natural resolution phase involves the production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes, which reduce neutrophil numbers and enhance monocyte activity, favoring tissue regeneration. This understanding has led to an interest in therapies that modulate rather than completely inhibit inflammation, contrasting with the mechanism of NSAIDs [9].

Additionally, acupuncture has been investigated as a complementary method for managing dental pain. This technique stimulates the release of endogenous opioid peptides, such as β-endorphins, enkephalins, neoendorphins, and dynorphins, through the nervous system, resulting in analgesic effects. These peptides can also be released in the digestive tract and adrenal medulla, broadening their therapeutic potential [29].

Beyond these general mechanisms, recent evidence has identified specific plant-derived metabolites that target well-characterized molecular receptors in oral tissues. These examples offer mechanistic insight and underscore the therapeutic relevance of natural compounds in orofacial inflammation.

Mechanisms of Action of Selected Plant Metabolites in Oral Inflammation

Salvia rosmarinus Spenn. (Lamiaceae). Rosmarinic acid, the predominant bioactive compound in Rosmarinus officinalis, has been linked to anti-inflammatory activity in oral contexts. Studies on human gingival fibroblasts challenged with lipopolysaccharides revealed that it reduces oxidative stress, preserves intracellular glutathione, and suppresses the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and iNOS, an effect linked to the inhibition of NF-κB signaling during periodontal inflammation [29]. Evidence in vascular smooth muscle cells also indicates that rosmarinic acid downregulates MAPK (ERK, JNK, p38) and NF-κB pathways, leading to a lower release of inflammatory mediators, including iNOS, TNF-α, and IL-8 under LPS stimulation. Although these results were obtained in non-oral systems, they support the molecular plausibility of this compound in modulating signaling cascades relevant to periodontal disease [30].

Moringa oleifera Lam. (Moringaceae) is a rich source of phytochemicals such as quercetin and isothiocyanates, which act on inflammatory pathways important in oral health. In a rat model of periodontal inflammation, ethanolic leaf extracts enriched with quercetin attenuated tissue damage by suppressing NF-κB activation, thereby reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and supporting periodontal regeneration [31]. Moringa isothiocyanate-1 (MIC-1) has also been shown to influence Nrf2 and NF-κB signaling in LPS-induced inflammation, thereby lowering the expression of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, while alleviating oxidative stress. Beyond preclinical findings, a randomized controlled trial involving 36 patients with gingivitis demonstrated that a Moringa oleifera mouthwash significantly decreased plaque and gingival indices after 14 days of use, showing efficacy comparable to chlorhexidine and superior to saline [32]. Altogether, this evidence provides a strong mechanistic and clinical rationale for Moringa oleifera as a natural adjunct in periodontal therapy.

Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. (Asphodelaceae). Acemannan, the main polysaccharide of Aloe vera, exhibits immunomodulatory properties within oral environments. In human gingival fibroblasts, acemannan binds to Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5), activating NF-κB signaling and promoting the release of IL-6 and IL-8. This process not only enhances tissue repair but also strengthens host immune defenses in periodontal tissues, offering dual benefits in regeneration and antimicrobial protection [33]. More broadly, Aloe vera and its major active metabolites, including acemannan and aloin, are recognized for their anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and wound-healing properties, reinforcing their potential applications in oral medicine [34].

Ocimum basilicum L. Linalool, a monoterpene present in Ocimum basilicum, has been shown to exert immunomodulatory effects relevant to periodontal inflammation. In vitro studies demonstrated that linalool reduces the overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, IFN-γ) in human immune cells exposed to Porphyromonas gingivalis, a key pathogen in periodontitis. These outcomes are linked to the downregulation of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways, which control the transcription of inflammatory genes. By moderating excessive immune responses without impairing cell viability, linalool may protect periodontal tissues from chronic inflammatory damage [35].

Propolis is a resinous product of Apis mellifera L. (Apidae). Current research highlights the role of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE), the principal phenolic constituent of propolis, in regulating inflammatory activity in periodontal cells. In human gingival fibroblasts stimulated with LPS and IFN-α, CAPE markedly suppressed TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 production, with no cytotoxicity observed. In contrast, ethanolic propolis extract (EEP) produced weaker and less consistent effects on cytokine release. These findings suggest that CAPE exerts a more selective and potent anti-inflammatory effect, supporting its potential application in controlling periodontal inflammation [30].

9. Internal Inflammatory Process

Inflammation within the oral cavity is frequently associated with periodontal pathogens, including Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. These microorganisms stimulate the production of various inflammatory mediators, including cytokines, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and thromboxanes, which are secreted by immune cells, epithelial cells, and fibroblasts. These mediators initiate the periodontal inflammatory cascade. Under normal physiological conditions, this response facilitates the elimination of harmful stimuli and promotes tissue healing. However, when inflammation becomes dysregulated or chronic, it can destroy periodontal tissues and lead to progressive bone resorption [9].

Among the inflammatory mediators, cytokines play a central role in modulating both inflammation and healing by balancing pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory signaling. Chemokines are also crucial, as they attract immune cells to the site of infection and contribute to bone remodeling through the activation of osteoclasts. Although essential in orchestrating the inflammatory response, prostaglandins may exacerbate tissue damage when overproduced, particularly by enhancing bone resorption. Additionally, extracellular matrix metalloproteases involved in tissue repair can lead to structural degradation and tissue weakening if produced in excess [9].

10. Properties of Medicinal Plants

Interest in medicinal plants has increased substantially in recent years, driven by their accessibility and the growing awareness of the adverse effects of conventional pharmaceuticals. It is estimated that there are approximately 260,000 plant species worldwide, of which around 10% possess documented medicinal properties [36]. Their integration into healthcare, including dental applications, has contributed to the development of alternative treatments with reduced side effect profiles.

However, using these plants requires accurate botanical knowledge regarding their identification, preparation, and administration. Although they are of natural origin, excessive or improper use can result in toxicity. It is essential to accurately identify the plant species, understand its origin, and determine which part of the plant—root, stem, leaves, or flowers—should be used, as each contains distinct bioactive compounds with varying therapeutic effects. This ancestral knowledge, transmitted through oral tradition, literature, and scientific research, has been crucial in expanding the scope of natural medicine. In many developing countries, these practices remain particularly relevant as accessible alternatives for treating various health conditions [36].

11. Biodiversity of Medicinal Plants in Latin America

Latin America is one of the most biodiverse regions in the world, offering a vast supply of raw materials for the pharmaceutical industry. However, despite this potential, the lack of regulation and international recognition has limited the sustainable development of these medicinal resources. Commercializing natural compound-based drugs often undervalues local raw materials, fostering an extractivist model that threatens biodiversity and compromises crop quality.

In response, various initiatives have emerged to regulate and promote the sustainable production of these plants. Within this framework, the Ibero-American Program of Science and Technology for Development has supported agroecological strategies to ensure sustainability in medicinal plant cultivation. Nonetheless, the primary challenge remains the revaluation of these crops, ensuring fair pricing that fosters responsible practices and contributes to regional biodiversity conservation [37].

12. Regulation of Medicinal Plants in Colombia

Natural and herbal medicine is recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a safe and effective alternative for treating various conditions. However, its integration into national healthcare systems remains challenging due to economic and structural barriers. The long-term objective is to make this medicine accessible for managing common ailments, such as stomach pain and influenza [38]. Although traditionally empirical, natural medicine requires scientific validation to prevent adverse effects and interactions with conventional drugs and food. Demonstrating its efficacy is key to enabling its proper integration into the healthcare system [38].

In Colombia, Law 1164 of 2007 regulates alternative medicine by establishing a specialized committee and permitting its practice exclusively by certified healthcare professionals. Practices such as herbology, acupuncture, and moxibustion are categorized as complementary therapies, although they are not currently included in the main regulatory committee [39]. The Ministry of Health and Social Protection has promoted the Technical Guidelines for integrating Alternative and Complementary Medicines and Therapies (MTAC), supporting their inclusion in primary healthcare and alignment with the General System of Social Security in Health (SGSSS). Laws 1438 of 2011 and 1752 of 2015 further support this framework in accordance with WHO recommendations.

13. Medicinal Plants for Inflammation and Gingival Problems

Medicinal plants have shown promising effects in managing inflammation and gingival conditions due to their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and healing properties. These plant species are utilized in various formulations, including infusions, mouthwashes, and topical applications, to alleviate oral symptoms and stimulate tissue regeneration. As summarized in Table 2, several plants are commonly used for gingival disorders across Latin America and other regions, highlighting their pharmacological diversity.

Table 2.

Medicinal plants: uses, indications, dosage, and bioactive compounds across different regions.

All dosages included in this table are supported by clinical studies, and whenever possible, standardized regimens are indicated. Additionally, a concise safety summary is provided for each plant, highlighting contraindications, potential drug interactions (e.g., anticoagulants), pregnancy-related considerations, hypersensitivity, and potential mucosal irritation. This approach ensures that the therapeutic use of these medicinal plants is presented with both efficacy and safety considerations, thereby enhancing the clinical relevance of the information.

14. Medicinal Plants for Periodontal Problems

Various medicinal plants have been effectively used to treat periodontal conditions due to their anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and healing properties. These plants are used in various presentations, including gels, rinses, infusions, and topical creams. As detailed in Table 3, several species contribute to managing biofilm accumulation, gingival inflammation, and tissue regeneration through their bioactive compounds.

Table 3.

Therapeutic properties and applications of selected medicinal plants in oral health.

The data presented in this table consolidate available clinical evidence on preparations and doses of medicinal plants for periodontal problems. Additionally, a brief overview of safety aspects is provided, highlighting relevant contraindications, potential drug interactions, and pregnancy considerations. By combining therapeutic potential with safety information, the table aims to offer a balanced reference that can guide clinical decision-making.

15. Results and Discussion

The classification of all cited references by source type is presented in Table S3. The present review identified 50 plant species with therapeutic, anti-inflammatory, healing, and analgesic properties applicable to oral health, particularly in conditions affecting dental support tissues such as bone, periodontal ligament, gingiva, and surrounding periodontal areas. In terms of geographic distribution, our analysis revealed that Mexico had the highest biodiversity (60%), followed by Colombia and Peru (54%) and Brazil (32%). These percentages represent the proportion of plant species reported in studies from each country relative to the total number of species identified in this review.

Within our dataset, the most extensively studied species with high therapeutic potential were propolis, rosemary, moringa, aloe vera, and basil. Among these, aloe vera and propolis already have clinical evidence supporting their use, whereas basil and moringa are still supported mainly by preclinical and in vitro data, highlighting the need for further clinical validation.

Oral pain is one of the most frequent and intense clinical manifestations due to the dense innervation of the region, particularly by the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). Inflammation exacerbates this condition through the release of chemical mediators, such as prostaglandins [28]. Although synthetic drugs remain the mainstay of treatment, prolonged use may result in adverse effects. In this context, the 50 species identified in our review emerge as promising alternatives due to their bioactive metabolites, which exhibit antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic activity, thereby supporting inflammation modulation and tissue regeneration [22].

It is essential to note that the following examples are external to the 50 species identified in this review. For instance, Waizel et al. [46] analyzed 29 species (51 plant uses) and concluded that infusions, decoctions, topical applications, and mouth rinses were the most common forms of administration. Similarly, Lameda Albornoz et al. [23] reported 30 species with potential applications in periodontal treatment, noting that pomegranate was less effective in controlling subgingival plaque and gingivitis compared to other plants. Likewise, Moya Jiménez [49] investigated medicinal plants in Ecuadorian communities and found that chamomile was widely used as an analgesic and anti-inflammatory agent, either alone (56%) or in combination with other remedies (44%).

These external studies complement our findings by highlighting the broader biodiversity of Latin America. However, the focus of our analysis remains exclusively on the 50 species identified in this review, which reinforce the therapeutic potential of regional flora and underscore the importance of sustainable management for their incorporation into dental practice [39].

In addition to therapeutic applications, safety aspects are essential for clinical translation. Table 4 summarizes the most common contraindications and precautions reported for the main species reviewed, including interactions with anticoagulants, allergy risks, and pregnancy-related concerns. Finally, to consolidate the findings of this review, Table 5 presents the 50 Latin American medicinal plants identified with dental applications, detailing their scientific name, family, plant part used, preparation type, indication, evidence type, and corresponding references. This comprehensive synthesis strengthens the relevance of phytotherapeutic diversity in Latin America and highlights its potential contribution to future dental research and practice.

Table 4.

Safety considerations for top medicinal plants in dentistry.

Table 5.

List of 50 Latin American medicinal plants with dental applications, including scientific name, family, plant part, preparation, indication, evidence type, and references.

16. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The findings of this review suggest that medicinal plants offer a promising source of bioactive compounds with potential applications in dentistry, particularly due to their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic properties. However, most of the current evidence derives from in vitro and preclinical studies, while only a few species (e.g., Aloe vera, Propolis, Calendula officinalis) have supportive clinical trials. Thus, clinical translation remains preliminary and requires rigorous validation through well-designed randomized controlled trials.

The development of optimized phytotherapeutic formulations (e.g., gels, mouthwashes, biofilms) could contribute to the management of periodontal and mucosal diseases, provided that issues of dosage, stability, and bioavailability are standardized. Comparative studies against conventional treatments (ibuprofen, paracetamol, and chlorhexidine) and long-term safety evaluations are essential before recommending routine dental use.

To facilitate clarity for readers and avoid overstating clinical potential, we have also included a summary table (Table 6) that highlights representative species, their study types, experimental models, and main findings. This addition allows for a transparent appraisal of the heterogeneity of evidence and helps contextualize the therapeutic promise of these plants within the current limitations of the field.

Table 6.

Safety considerations and contraindications of selected medicinal plants relevant to dentistry.

Finally, attention to regulatory frameworks and sustainable sourcing will be critical to ensure that future phytotherapeutic approaches remain safe, effective, and accessible.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms262311502/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.R.-T. and N.R.-G.; Methodology, V.R.-T.; Validation, N.R.-G. and C.T.-L.; Formal Analysis, V.R.-T. and L.L.-H.; Investigation, V.R.-T.; Resources, V.R.-T.; Data curation, V.R.-T.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, V.R.-T.; Writing—Review and Editing, N.R.-G., R.G.-G. and C.T.-L.; Supervision, N.R.-G., C.T.-L., L.L.-H. and R.G.-G.; Project Administration, N.R.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Universidad Autónoma de Coahuila for academic support and collaboration during the development of this review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Oral Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/oral-health (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Secretaría de Salud de Medellín. Profundización del Análisis de la Situación S. Medellín 2005–2020; Secretaría de Salud: Medellín, Colombia, 2021; pp. 1–50.

- Valdéz Grefa, L.K.; Palacios Paredes, E.W. Prácticas etnobotánicas odontológicas de la comunidad Kichwa Playas de Oro, parroquia Santa Cecilia, cantón Lago Agrio, provincia de Sucumbíos. Recimundo 2022, 6 (Suppl. S1), 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, F.; Faúndez, F.; Roa, I. Fitoterapias en lesiones de mucosa oral: Propiedades reparativas y aplicación clínica. Revisión sistemática de la literatura. Int. J. Odontostomatol. 2016, 10, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vara-Delgado, A.; Sosa-González, R.; Alayón-Recio, C.S.; Ayala-Sotolongo, N.; Moreno-Capote, G.; Alayón-Recio, V.C. Uso de la manzanilla en el tratamiento de las enfermedades periodontales. Rev. Arch. Med. Camagüey 2019, 23, 403–409. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Herrero, M.T.; Delgado-Bueno, S.; Bandrés-Moyá, F.; Ramírez-Íñiguez-de-la-Torre, M.V.; Capdevilla-García, L. Valoración del dolor. Revisión comparativa de escalas y cuestionarios. Rev. Soc. Esp. Dolor 2018, 25, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de la Protección Social. Vademécum Colombiano de Plantas Medicinales; Ministerio de la Protección Social: Bogotá, Colombia, 2008.

- Miguélez-Medrán, B.C.; Goicoechea García, C.; López Sánchez, A.; Martínez García, M.A. Dolor orofacial en la clínica odontológica. Rev. Soc. Esp. Dolor 2019, 26, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Reyes, O.; García Cabrera, L.; Bosch Núñez, A.I.; Inclán Acosta, A. Fisiopatología del dolor bucodental: Una visión actualizada del tema. Medisan 2013, 17, 5080–5090. [Google Scholar]

- Latorre, G.; González-García, N.; García-Ull, J.; González-Oria, C.; Porta-Etessam, J.; Molina, F.J.; Guerrero-Peral, A.L.; Belvís, R.; Rodríguez, R.; Bescós, A.; et al. Diagnóstico y tratamiento de la neuralgia del trigémino: Documento de consenso del Grupo de Estudio de Cefaleas de la Sociedad Española de Neurología. Neurología 2023, 38 (Suppl. S1), S37–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ríos Erazo, M.; Herrera Ronda, A.; Rojas Alcayaga, S. Ansiedad dental: Evaluación y tratamiento. Av. Odontoestomatol. 2014, 30, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Sánchez, A.F.; González Romero, E.A. Dolor dental. Med. Integr. 2001, 37, 242–249. [Google Scholar]

- Servicio Canario de la Salud. Dirección General de Salud Pública. ¿Qué es el Dolor Dental? Programa de Salud Oral. Servicio de Promoción de la Salud, Gobierno de Canarias; 2025. Available online: https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/sanidad/scs/content/4b1164e9-e63b-11e0-bf4e-bd28dc0dbd05/que_es_el_dolor_dental.pdf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Mata Sánchez, N.; Jiménez Méndez, C.; Sánchez Mendieta, K.P. Recesión gingival y su efecto en la hipersensibilidad dentinaria. Rev. ADM 2018, 75, 326–333. [Google Scholar]

- Jwa, S.K. Eficacia de los extractos de hoja de Moringa oleifera contra la biopelícula cariogénica. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 24, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canakci, C.F.; Canakci, V. Dental pain experienced by patients undergoing different periodontal therapies. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2007, 138, 1563–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalá Pizarro, M.; Cortés Lillo, O. La caries dental: Una enfermedad que se puede prevenir. An. Pediatría Contin. 2014, 12, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gallego, J.; Sánchez-Campos, S.; Tuñón, M.J. Anti-inflammatory properties of dietary flavonoids. Nutr. Hosp. 2007, 22, 287–293. [Google Scholar]

- López Silva, M.C.; Diz-Iglesias, P.; Seoane-Romero, J.M.; Quintas, V.; Méndez-Brea, F.; Varela-Centelles, P. Actualización en medicina de familia: Patología periodontal. Med. Fam. (Semer.) 2017, 43, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A. Los analgésicos en odontología. Quintessence 2012, 25, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Casariego, Z.J. Mecanismo de acción de plantas medicinales aplicadas en lesiones estomatológicas: Revisión. Av. Odontoestomatol. 2016, 32, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazzo, F.; Souza, R.; Carvalho, J.C.; Groppo, F. Utilización de sustancias naturales en odontología. J. Bras. Fitomed. 2004, 2, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lameda Albornoz, M.A.; Paredes Rivas, M.F.; Sánchez Díaz, J.T.; Sayago Lameda, M.J.; Yáñez Guerrero, P.A. Uso de las plantas medicinales para el tratamiento de la enfermedad periodontal: Una revisión sistemática. Rev. Venez. Investig. Odontol. 2019, 7, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes-Martins, R.A.; Pegoraro, D.H.; Woisky, R.; Penna, S.C.; Sertié, J.A. The anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of a crude extract of Petiveria alliacea L. (Phytolaccaceae). Phytomedicine 2002, 9, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Filho, E.X.D.; Arantes, D.A.C.; Oton Leite, A.F.; Batista, A.C.; Mendonça, E.F.; Marreto, R.N.; Naves, L.N.; Lima, E.M.; Valadares, M.C. Randomized clinical trial of a muco-adhesive formulation containing curcuminoids (Zingiberaceae) and Bidens pilosa Linn (Asteraceae) extract (FITOPROT) for the prevention and treatment of oral mucositis–phase I study. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 291, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criollo Jiménez, M.E. Efecto Antiinflamatorio de Zingiber officinale Roscoe (Jengibre) Sobre los Tejidos Blandos en Estudiantes de Octavo, Noveno y Décimo Año de Educación Básica del Colegio Fis-Comisional “La Dolorosa” que Presentan Gingivitis, en el Período Junio–Diciembre 2011. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Loja, Loja, Ecuador, 2012. Available online: https://dspace.unl.edu.ec/server/api/core/bitstreams/aedc9d50-b461-43a1-9cc5-517489c753e1/content (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Rodríguez, M.; Aguilar, D.; León, J. Actividad antiinflamatoria de plantas medicinales: Anti-inflammatory activity of medicinal plants (Review). Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Hortic. 2020, 14, e11847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraza, M.A.; Calabró, L.R.; Delgado, E.M.; Peñaloza Azcurra, L.; Suárez Medina, A.L. Usos y Conocimientos de Plantas Medicinales. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de San Martín, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2020. Available online: https://ri.unsam.edu.ar/handle/123456789/1316 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Zdarilová, A.; Svobodová, A.; Šimánek, V.; Ulrichová, J. Extract of Prunella vulgaris and rosmarinic acid suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced alteration in human gingival fibroblasts. Toxicol. In Vitro 2009, 23, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-P.; Lin, Y.-C.; Peng, Y.-H.; Chen, H.-M.; Lin, J.-T.; Kao, S.-H. Rosmarinic acid attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in vascular smooth muscle cells by inhibiting MAPK/NF-κB pathway. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiharto, S.; Ramadany, S.; Handayani, H.; Achmad, H.; Gani, A.; Tanumihardja, M.; Sesiorina, A.; Harmawaty. Ethanolic extract of Moringa oleifera leaves influences NF-κB signaling pathway for periodontal tissue regeneration in rats. J. Popul. Ther. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 30, e324–e332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandikur, S.; Guttiganur, N.; Aspalli, S.; Bhavana. Comparing the anti-plaque and anti-gingivitis efficacy of Moringa oleifera mouthwash to chlorhexidine and saltwater concentration in treating gingivitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. IOSR J. Dent. Med. Sci. 2025, 24, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Thuwajit, P.; Ruangpornvisuti, V.; Kengkwasing, P.; Chokboribal, J.; Sangvanich, P. Acemannan increases NF-κB/DNA binding and IL-6/-8 expression by selectively binding Toll-like receptor-5 in human gingival fibroblasts. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 161, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; González-Burgos, E.; Iglesias, I.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P. Pharmacological update properties of Aloe vera and its major active constituents. Molecules 2020, 25, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.P.; Carvalho-Filho, P.C.; Sampaio, G.P.; Silva, R.R.; Falcão, M.M.; Pimentel, A.C.M.; Oliveira, Y.A.; Miranda, P.M.; Santos, E.K.N.; Meyer, R.; et al. In vitro immunomodulatory effect of linalool on P. gingivalis infection. Glob. J. Med. Res. F Dis. 2019, 20, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozoya Legorreta, X. ¿Una Nueva Farmacéutica Para el Siglo XXI? La Aportación de América Latina al Estudio de las Plantas Medicinales; Editorial CENIC: La Habana, Cuba, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Soria, N. Medicinal plants and their application in public health. Rev. Salud Pública Parag. 2018, 8, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congreso de Colombia. Ley 1164 de 2007, por la Cual se Dictan Disposiciones en Materia del Talento Humano en Salud; Diario Oficial No. 46.786, Bogotá, Colombia. 2007. Available online: https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/eva/gestornormativo/norma.php?i=27528 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Lineamientos Técnicos para la Articulación de las Medicinas y las Terapias Alternativas y Complementarias, en el Marco del Sistema General de Seguridad Social en Salud; Ministerio de Salud: Bogotá, Colombia, 2018.

- Cervantes Pérez, A. Medicina Alternativa: Fitoterapia Como Coadyuvante en el Tratamiento de la Enfermedad Periodontal 2016. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico, 2017. Available online: https://repositorio.unam.mx/contenidos/393452 (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Menon, P.; Pevali, J.; Fenol, A.; Peter, M.R.; Lakshmi, P.; Suresh, R. Effectiveness of ginger on pain following periodontal surgery: A randomized crossover clinical trial. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2020, 12, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maragliano, P.; Viola, T. How Ginger Supplements Can Affect Dental Care. DentistryIQ. 8 May 2024. Available online: https://www.dentistryiq.com/dentistry/pharmacology/video/55038367/how-ginger-supplements-can-affect-dental-care (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Gutiérrez, R.; Albarrán, R. Uso de plantas medicinales como terapia coadyuvante en el tratamiento periodontal: Revisión de la literatura. Rev. Odontol. Los Andes 2020, 15, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, S.A.; Akram, H.M. Evaluating the efficacy of resveratrol-containing mouthwash as an adjunct treatment for periodontitis: A randomized clinical trial. Eur. J. Dent. 2025, 19, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragul, P.; Dhanraj, M.; Jain, A.R. Efficacy of eucalyptus oil over chlorhexidine mouthwash in dental practice. Drug Invent. Today 2018, 10, 638–641. [Google Scholar]

- Waizel-Bucay, J.; Martín Martínez Rico, I. Plantas empleadas en odontalgias I. Rev. ADM 2007, 64, 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Khairnar, M.S.; Pawar, B.; Marawar, P.P.; Mani, A. Evaluation of Calendula officinalis as an anti-plaque and anti-gingivitis agent. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2013, 17, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, N.; Varghese, J.; Shetty, S.; Bhat, V.; Durekhar, T.; Lobo, R.; Nayak, U.Y.; Vishwanath, U. Evaluation of a mouthrinse containing guava leaf extract as part of comprehensive oral care regimen: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya Jiménez, L.E. Uso de Plantas Medicinales Como Analgésico-Antiinflamatorio en la Parroquia Marcos Espinel del Cantón Santiago de Pillaro. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Técnica de Ambato, Ambato, Ecuador, 2018. Available online: https://repositorio.uta.edu.ec/items/cd0c16b7-350b-4270-aa4b-f4983015952f (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Ali, M.S.M.; Mohammed, A.N. Efficacy of oregano essential oil mouthwash in reducing oral halitosis: A randomized, double-blind clinical trial. J. Res. Med. Dent. Sci. 2021, 9, 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Oregano. In LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury [Internet]; National Library of Medicine (US): Bethesda, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK591556/ (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Yuan, Y.; Sun, J.; Song, Y.; Raka, R.N.; Xiang, J.; Wu, H.; Xiao, J.; Jin, J.; Hui, X. Antibacterial activity of oregano essential oils against Streptococcus mutans in vitro and analysis of active components. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Gupta, D.; Bhaskar, D.J.; Yadav, A.; Obaid, K.; Mishra, S. Preliminary antiplague efficacy of Aloe vera mouthwash in a 4-day plaque regrowth model: A randomized control trial. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2014, 24, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, M.; Holst, L. Herbal medicine use during pregnancy: A review of the literature with a special focus on Sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, D.G.; Nadimpalli, H.; Nayak, S.U.; Rajendran, V.; Natarajan, S. Comparison of anti-plaque and anti-gingivitis effects of Aloe vera mouthwash with chlorhexidine in fixed orthodontic patients: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2023, 21, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vairabhava, L.O.; Korsuwannawong, S.; Ruangsawasdi, N.; Phruksaniyom, C.; Srichan, R. The efficiency of natural wound healing and bacterial biofilm inhibition of Aloe vera and sodium chloride toothpaste preparation. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosamane, M.; Acharya, A.B.; Vij, C.; Trivedi, D.; Setty, S.B.; Thakur, S.L. Evaluation of holy basil mouthwash as an adjunctive plaque control agent in a four-day plaque regrowth model. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2014, 6, e491–e496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoudi, R.; Aldiab, D.; Hasan, N. Study of the anticoagulant effect of Ocimum basilicum extract. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2024, 17, 3339–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Bhaskar, D.J.; Gupta, R.K.; Karim, B.; Jain, A.; Singh, R.; Karim, W. A randomized controlled clinical trial of Ocimum sanctum and chlorhexidine mouthwash on dental plaque and gingival inflammation. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2014, 5, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, S. Anti-inflammatory activity of phytochemicals from Ocimum sanctum against cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2): A review. Plant Cell Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. 2021, 22, 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sultana, A.; Tasneem, A.; Krishnappa, P.; Shwetha, K.M. Efficacy of Moringa oleifera mouthwash in young adults as an antiplaque agent: An interventional study. J. Indian Assoc. Public Health Dent. 2024, 22, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebhohon, E.; Miller, D. Moringa oleifera leaf extract–induced pulmonary embolism: A case report. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, K.; Thomas, B.; Varma, S.R.; Kamath, V.; Shetty, B.; Kuduruhtullah, S.; Nambiar, M. Antiplaque efficacy of a novel Moringa oleifera dentifrice: A randomized clinical cross-over study. Eur. J. Dent. 2022, 16, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita-Labori, L.Y.; Matos-Cantillo, D.M.; Quintero-Lores, C.M.; Castillo-Pérez, Y.; Nicó-Navarro, A.M. Uso de Petiveria alliacea Linn como tratamiento paliativo del dolor pulpar. Rev. Inf. Cient. 2023, 102, 4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.J.; Cerdeira, C.; Chavasco, J.; Cintra, A.; Silva, C.; Mendonça, A.; Ishikawa, T.; Boriollo, M.; Chavasco, J. In vitro screening antibacterial activity of Bidens pilosa Linné and Annona crassiflora Mart. against oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (ORSA) from the aerial environment at the dental clinic. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 2014, 56, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunes, R.A.; Pedrosa, R.C.; Filho, V.C.; Calixto, J.B. Isolation and identification of active compounds from Drimys winteri barks. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1998, 62, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.D.; Reis, A.C.C.; Sousa, J.A.C.; Valente, G.M.; de Mello Silva, B.; Magalhães, C.L.B.; Kohlhoff, M.; Teixeira, L.F.M.; Brandão, G.C. Anti–Zika virus activity and isolation of flavonoids from ethanol extracts of Curatella americana L. leaves. Molecules 2023, 28, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sequeda, L.G. Antimicrobial Activity of Baccharis latifolia (Ruiz & Pavón) Pers. (Asteraceae) on Microorganisms Pathogens and Cariogenics. In Proceedings of the V Congreso Iberoamericano de Productos Naturales, Bogotá, Columbia, 25–29 April 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanashiro, C.T.; Miranda González, A.H. Coriandrum sativum (Coriander) in oral health: Literature review. J. Health Sci. 2021, 23, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millones-Gómez, P.A.; Maurtua-Torres, D.; Bacilio-Amaranto, R.; Calla-Poma, R.D.; Requena-Mendizabal, M.F.; Valderrama-Negron, A.C.; Calderon-Miranda, M.A.; Calla-Poma, R.A.; Huauya-Leuyacc, M.E. Antimicrobial activity and antiadherent effect of Peruvian Psidium guajava (Guava) leaves on a cariogenic biofilm model. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2020, 21, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organismo Andino de Salud-Convenio Hipólito Unanue (ORAS-CONHU). Plantas Medicinales de la Subregión Andina; ORAS-CONHU: Lima, Peru, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, A.; Chaudhary, B. Clinical and microbiological effects of 1% Matricaria chamomilla mouth rinse on chronic periodontitis: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2020, 24, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Tito, M.A.; Cartagena-Cutipa, R.; Flores-Valencia, E.; Castillo-Pérez, Y.; Nicó-Navarro, A.M. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oil from Minthostachys mollis against oral pathogens. Rev. Cub. Estomatol. 2021, 58, e3647. [Google Scholar]

- Paucar-Rodríguez, E.; Peltroche-Adrianzen, N.; Cayo-Rojas, C.F. Actividad antibacteriana y antifúngica del aceite esencial de Minthostachys mollis frente a microorganismos de la cavidad oral. Rev. Cub. Investig. Bioméd. 2021, 40 (Suppl. 1), e1450. [Google Scholar]

- Idir, F.; Van Ginneken, S.; Coppola, G.A.; Grenier, D.; Steenackers, H.P.; Bendali, F. Origanum vulgare ethanolic extracts as a promising source of compounds with antimicrobial, anti-biofilm, and anti-virulence activity against dental plaque bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 999839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potra-Cicalău, G.I.; Ciavoi, G.; Todor, L.; Iurcov, R.C.; Iova, G.; Ganea, M.; Scrobotă, I. The benefits of Calendula officinalis extract as therapeutic agent in oral healthcare. Med. Evol. 2022, 28, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.X.; Lin, F.J.; Li, H.; Li, H.B.; Wu, D.T.; Geng, F.; Ma, W.; Gan, R.Y. Recent advances in bioactive compounds, health functions and safety concerns of onion (Allium cepa L.). Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 669805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.A.; Alnazeh, A.A.; Almoammar, S.; Almagbol, M.; Baig, E.A.; Alrwuili, M.R.; Aljabab, M.A.; Alshahrani, I. Effect of plant-based mouthwash (Morinda citrifolia and Ocimum sanctum) on TNF-α, IL-α, IL-β, IL-2, and IL-6 in gingival crevicular fluid and plaque scores of patients undergoing fixed orthodontic treatment. Medicina 2023, 59, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmawati, D.Y.; Kurniawan, V.F.; Sanjaya, O.T.C.; Sugiama, V.K.; Mandalas, H.Y. Antibacterial effects of tomato ethanol extract (Solanum lycopersicum L.) against S. mutans and P. gingivalis: A laboratory experiment. Padjadjaran J. Dent. 2023, 35, e50582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Flores, M.A.; Quintero-Cabello, K.P.; Palafox-Rivera, P.; Silva-Espinoza, B.A.; Cruz-Valenzuela, M.R.; Ortega-Ramirez, L.A.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F. Plant-derived substances with antibacterial, antioxidant, and flavoring potential to formulate oral health care products. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Panda, N.R.; Bhuyan, R.; Bhuyan, S.K. Moringa oleifera and its application in dental conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Herbmed Pharmacol. 2023, 12, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuttion, G.S.; Juárez, H.A.B.; Lima, B.D.; Assumpção, D.P.; Daneris, Â.P.; Tuchtenhagen, I.H.; Casarin, M.; Muniz, F.W.M.G. Comparison of the anti-plaque and anti-gingivitis efficacy of chlorhexidine and Malva mouthwashes: Randomized crossover clinical trial. J. Dent. 2024, 150, 105313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, M.; Karygianni, L.; Argyropoulou, A.; Anderson, A.C.; Hellwig, E.; Skaltsounis, A.L.; Wittmer, A.; Vach, K.; Al-Ahmad, A. The antimicrobial effect of Rosmarinus officinalis extracts on oral initial adhesion ex vivo. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 4369–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayas-Morejón, F.; Ramón, R.R.; García-Pazmiño, M.; Mite-Cárdenas, G. Antibacterial and antioxidant effect of natural extracts from Baccharis latifolia (Chilka). Caspian J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 18, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, A.C.; Acharya, A.P.; Lee, S.B.; Gottardi, R.; Zaleski, E.; Little, S.R. Cranberry extract-based formulations for preventing bacterial biofilms. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2021, 11, 1144–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Xiang, Z.; Wang, S.; Cong, Z.; Gao, P.; Liu, X. Recent advances in nutritional composition, phytochemistry, bioactive, and potential applications of Syzygium aromaticum L. (Myrtaceae). Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1002147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saber Batiha, G.; Alkazmi, L.M.; Wasef, L.G.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Nadwa, E.H.; Rashwan, E.K. Syzygium aromaticum L. (Myrtaceae): Traditional uses, bioactive chemical constituents, pharmacological and toxicological activities. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarabadi, M.; Ghaznavi-Rad, E.; Pakniyat, A.; Rezaie, K.; Jadidi, A. Comparing the effect of Echinacea and chlorhexidine mouthwash on the microbial flora of intubated patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Iran J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2017, 22, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, F. Phytochemistry, mechanisms, and preclinical studies of Echinacea extracts in modulating immune responses to bacterial and viral infections: A comprehensive review. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaboua, K.; Pakoussi, T.; Mouzou, A.; Assih, M.; Kadissoli, B.; Dossou-Yovo, K.M.; Bois, P. Toxicological evaluation of Hydrocotyle bonariensis Comm. ex Lamm (Araliaceae) leaves extract. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2021, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivananda, S.; Doddawad, V.G.; Bhuyan, L.; Shetty, A.; Pushpa, V.H. Assessment of the antibacterial activity of Spilanthes acmella against bacteria associated with dental caries and periodontal disease: An in vitro microbiological study. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 18, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daga-Mauricio, K.M.; Castillo-Saavedra, E.F.; Reyes-Alfaro, C.E.; Salas-Sánchez, R.M.; Vargas-Vigo, J.E. Enfermedad bucodental y masticación de hoja de coca en pobladores peruanos [Oral disease and coca leaf chewing in Peruvian residents]. Av. Odontoestomatol. 2024, 40, 78–83. Available online: https://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/odonto/v40n2/0213-1285-odonto-40-2-78.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Dayal, S.D.; Pushpa Rani, V.; Antony Prabhu, D.; Rajeshkumar, S.; David, D.; Francis, J. Formulation and evaluation of Phaseolus lunatus seed coat mediated silver nanoparticles mouthwash: A comprehensive study on biomedical properties and toxicological assessment. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 197, 107033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A.; Ghasemzadeh, Z.; Ghaffari Hamedani, S.M.M.; Akbari, J.; Moosazadeh, M.; Mirzaee, F.; Zamanzadeh, M.; Shahani, S. Efficacy of black mulberry mouthwash for prevention of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. Front. Dent. 2025, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, T.T.; Ozan, G.; Dundar, S.; Bozoglan, A.; Karaman, T.; Dildes, N.; Kaya, C.A.; Kaya, N.; Erdem, E. The effects of Morus nigra on the alveolar bone loss in experimentally induced periodontitis. Eur. Oral Res. 2019, 53, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halboub, E.; Al-Maweri, S.A.; Al-Wesabi, M.; Al-Kamel, A.; Shamala, A.; Al-Sharani, A.; Koppolu, P. Efficacy of propolis-based mouthwashes on dental plaque and gingival inflammation: A systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).