Microwave-Assisted Chemical Activation of Caraway Seeds with Potassium Carbonate for Activated Carbon Production: Physicochemical Characterization and Adsorption Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

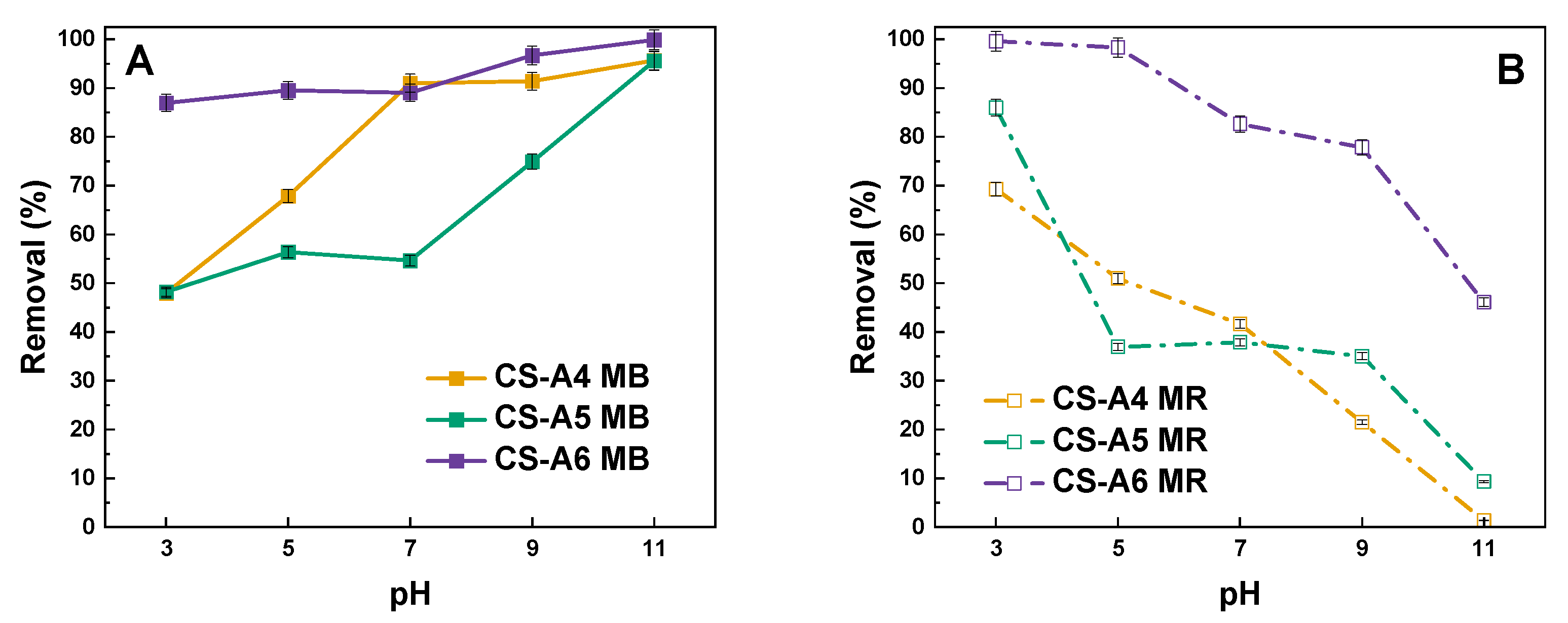

Adsorption

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Precursor and Activated Carbon Samples Preparation

3.2. Characterization of Resulted Activated Carbon Samples

3.3. Adsorption Studies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lobato-Peralta, D.R.; Duque-Brito, E.; Orugba, H.O.; Arias, D.M.; Cuentas-Gallegos, A.K.; Okolie, J.A.; Okoye, P.U. Sponge-like nanoporous activated carbon from corn husk as a sustainable and highly stable supercapacitor electrode for energy storage. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 138, 110176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okman, I.; Karagöz, S.; Tay, T.; Erdem, M. Activated carbons from grape seeds by chemical activation with potassium carbonate and potassium hydroxide. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 293, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsom, M.; Autthanit, C. Adsorptive purification of crude glycerol by sewage sludge-derived activated carbon prepared by chemical activation with H3PO4, K2CO3 and KOH. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 229, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, G.; Rehman, A.; Hussain, S.; Mahmood, Q.; Fteiti, M.; Heo, K.; Din, M.A.U. Towards a sustainable conversion of biomass/biowaste to porous carbons for CO2 adsorption: Recent advances, current challenges, and future directions. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 4941–4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Sultana, A.I.; Chambers, C.; Saha, S.; Saha, N.; Kirtania, K.; Reza, M.T. Recent Progress on Emerging Applications of Hydrochar. Energies 2022, 15, 9340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busca, G. Bases and basic materials in industrial and environmental chemistry: A review of commercial processes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 6486–6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidarinejad, Z.; Dehghani, M.H.; Heidari, M.; Javedan, G.; Ali, I.; Sillanpää, M. Methods for preparation and activation of activated carbon: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesas, R.H.; Daud, W.M.A.W.; Sahu, J.N.; Arami-Niya, A. The effects of a microwave heating method on the production of activated carbon from agricultural waste: A review. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2013, 100, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.; Sahoo, S.; Kumar, R.; Singh, R.K. A review of the microwave-assisted synthesis of carbon nanomaterials, metal oxides/hydroxides and their composites for energy storage applications. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 11679–11711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoriyekomwan, J.E.; Tahmasebi, A.; Dou, J.; Wang, R.; Yu, J. A review on the recent advances in the production of carbon nanotubes and carbon nanofibers via microwave-assisted pyrolysis of biomass. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 214, 106686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Peng, J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, K.; Xia, H.; Zhang, S.; Guo, S.H. Preparation of activated carbon from coconut shell chars in pilot-scale microwave heating equipment at 60 kW. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, W.; Fu, J.; Mao, X.; Kang, Q.; Ran, C.; Liu, Y.; Dai, J. Microwave assisted preparation of activated carbon from biomass: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 92, 958–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari Selvam, S.; Paramasivan, B. Microwave assisted carbonization and activation of biochar for energy-environment nexus: A. review. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, J.Y.; Choe, S.; Jang, Y.J.; Kim, H. Waste paper-derived porous carbon via microwave-assisted activation for energy storage and water purification. Chemosphere 2024, 355, 141798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khuong, D.A.; Trinh, K.T.; Nakaoka, Y.; Tsubota, T.; Tashima, D.; Nguyen, H.N.; Tanaka, D. The investigation of activated carbon by K2CO3 activation: Micropores-and macropores-dominated structure. Chemosphere 2022, 299, 134365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, G.; Park, J.E.; Kim, S.H. Limitation of K2CO3 as a Chemical Agent for Upgrading Activated Carbon. Processes 2021, 9, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, F.; Kornhauser, I.; Felipe, C.; Esparza, J.M.; Cordero, S.; Domínguez, A.; Riccardo, J.L. Capillary condensation in heterogeneous mesoporous networks consisting of variable connectivity and pore-size correlation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002, 4, 2346–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhao, N.; Tong, L.; Lv, Y. Structural and adsorption characteristics of potassium carbonate activated biochar. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 21012–21019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, W.M.A.W.; Houshamnd, A.H. Textural characteristics, surface chemistry and oxidation of activated carbon. J. Nat. Gas Chem. 2010, 19, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Carrizosa, S.B.; Jasinski, J.; Dimakis, N. Charge transfer dynamical processes at graphene-transition metal oxides/electrolyte interface for energy storage: Insights from in-situ Raman spectroelectrochemistry. AIP Adv. 2018, 8, 065225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, B.; Huang, M.; Cai, B. On the preparation and characterization of activated carbon from mangosteen shell. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2021, 42, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.M.; Le Luu, T. Synthesis of activated carbon from macadamia nutshells activated by H2SO4 and K2CO3 for methylene blue removal in water. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2020, 12, 100583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilev, C.; Dicko, M.; Langlois, P.; Lamari, F. Modelling of Single-Gas Adsorption Isotherms. Metals 2022, 12, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigdorowitsch, M.; Pchelintsev, A.; Tsygankova, L.; Tanygina, E. Freundlich Isotherm: An Adsorption Model Complete Framework. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, N.; Danesh, S.; Eftekhari, M.; Farahmandzadeh, M. Application of graphene oxide and its derivatives on the adsorption of a cationic surfactant (interaction mechanism, kinetic, isotherm curves and thermodynamic studies). J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 368, 120720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, R.; Mulky, L. Adsorption of dyes from wastewater: A comprehensive review. ChemBioEng Rev. 2023, 10, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Da, T.; Ma, Y. Reasonable calculation of the thermodynamic parameters from adsorption equilibrium constant. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 322, 114980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X. Adsorption kinetic models: Physical meanings, applications, and solving methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 390, 122156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluch, D.; Bazan-Wozniak, A.; Nosal-Wiercińska, A.; Pietrzak, R. Efficient dye removal by biocarbon obtained by chemical recycling of waste from the herbal industry. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 220, 119254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajoriya, S.; Saharan, V.K.; Pundir, A.S.; Nigam, M.; Roy, K. Adsorption of methyl red dye from aqueous solution onto eggshell waste material: Kinetics, isotherms and thermodynamic studies. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 4, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, H.P. Some aspects of the surface chemistry of carbon blacks and other carbons. Carbon 1994, 32, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Jiang, L.; Gao, Y.; Sheng, L. Effects of oxygen-containing functional groups on carbon materials in supercapacitors: A review. Mater. Des. 2023, 230, 111952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Surface Area 1 (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | Average Pore Size (nm) | Iodine Number (mg/g) | Ash Content (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Microporous | Total | Microporous | ||||

| CS-A4 | 25 | 0 | 0.183 | 0 | 28.89 | 385 | 1.31 |

| CS-A5 | 284 | 149 | 0.278 | 0.083 | 3.92 | 306 | 2.11 |

| CS-A6 | 634 | 406 | 0.483 | 0.235 | 3.05 | 575 | 3.41 |

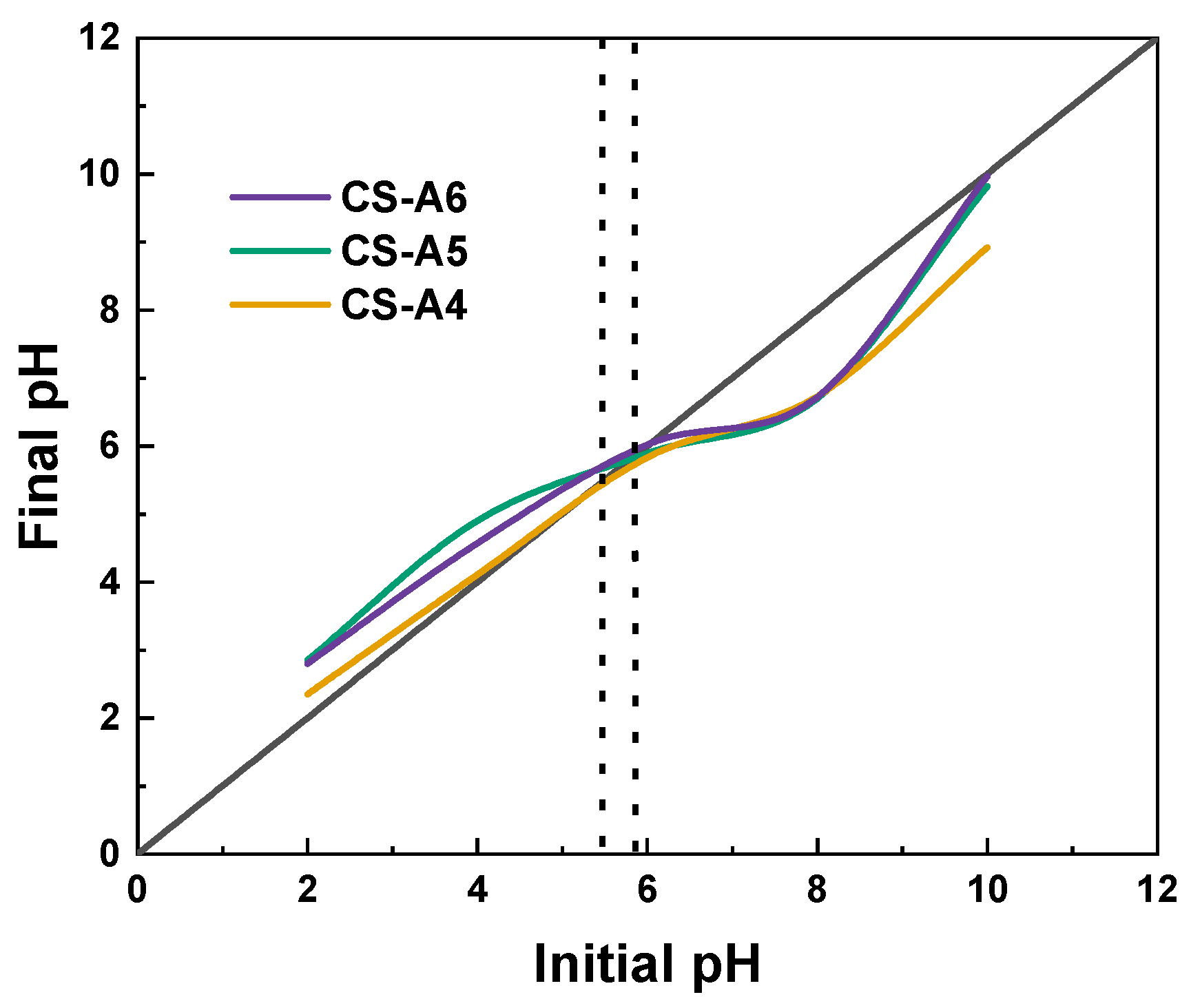

| Sample | pH | Acidic Oxygen Functional Groups (mmol/g) | Basic Oxygen Functional Groups (mmol/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS-A4 | 5.37 ± 0.01 | 1.32 ± 0.07 | 0.43± 0.02 |

| CS-A5 | 5.37 ± 0.01 | 1.30 ± 0.07 | 0.43 ± 0.02 |

| CS-A6 | 5.38 ± 0.01 | 1.93± 0.10 | 0.53 ± 0.03 |

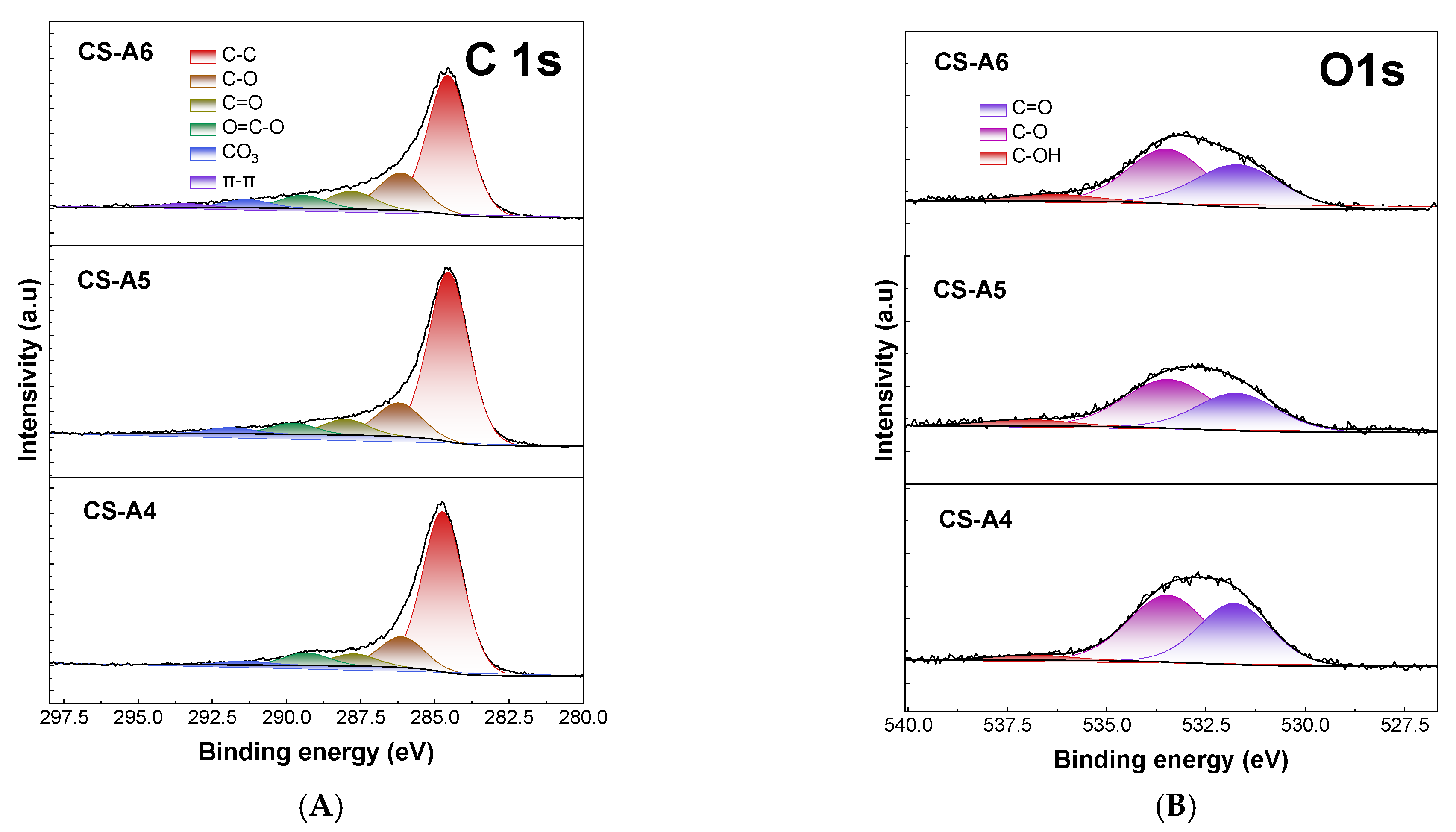

| Sample | C wt.% | N wt.% | H wt.% | O wt.% * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS-A4 | 73.71 | 5.03 | 4.18 | 17.08 |

| CS-A5 | 72.16 | 4.95 | 2.81 | 20.08 |

| CS-A6 | 65.33 | 4.97 | 2.69 | 27.01 |

| Sample | C at.% | O at.% | N at.% |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS-A4 | 89.27 | 9.93 | 0.81 |

| CS-A5 | 92.60 | 5.45 | 1.96 |

| CS-A6 | 89.39 | 7.17 | 3.43 |

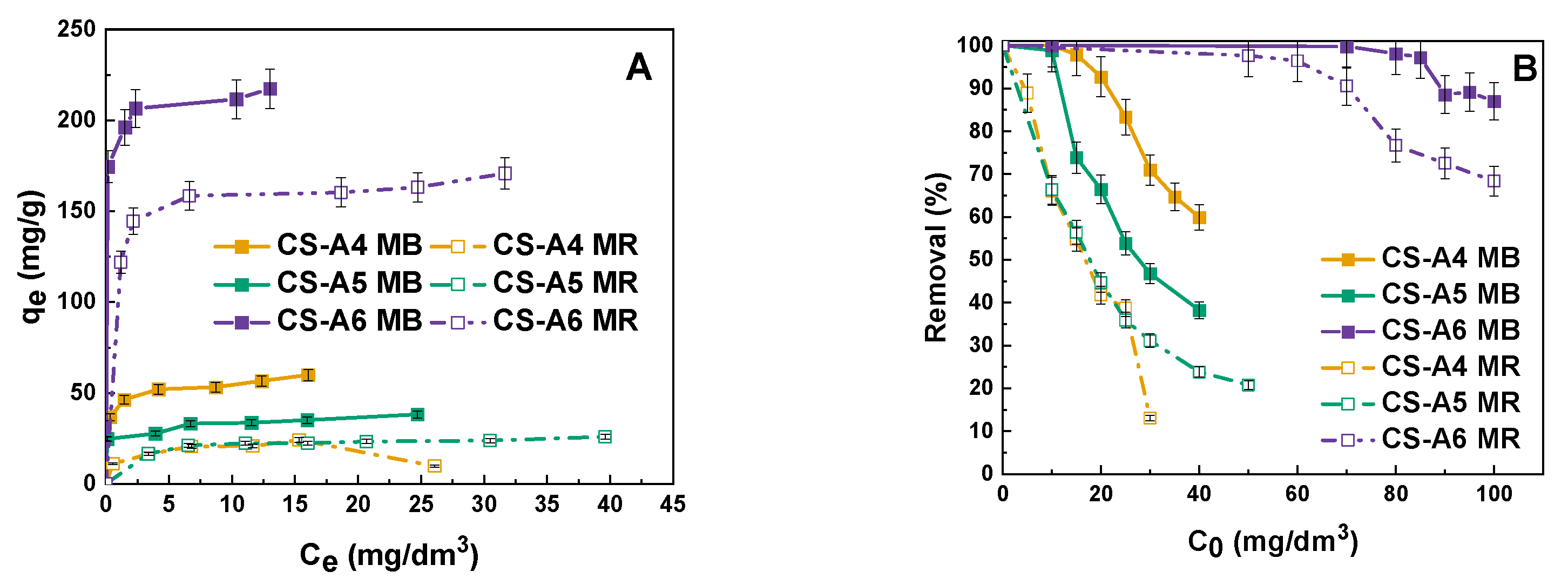

| Isotherm | Parameters | Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS-A4 | CS-A5 | CS-A6 | ||

| qexp (mg/g) | 60 | 38 | 217 | |

| Langmuir | KL (dm3/mg) | 0.715 | 0.589 | 2.121 |

| qm (mg/g) | 63 | 39 | 220 | |

| R2 | 0.951 | 0.973 | 0.972 | |

| Adj2 | 0.927 | 0.964 | 0.957 | |

| Freundlich | KF (mg/g(dm3/mg)1/n) | 44.641 | 23.240 | 183.997 |

| 1/n | 0.097 | 0.155 | 0.048 | |

| R2 | 0.945 | 0.900 | 0.6831 | |

| Adj2 | 0.926 | 0.866 | 0.578 | |

| Isotherm | Parameters | Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS-A4 | CS-A5 | CS-A6 | ||

| qexp (mg/g) | 24 | 26 | 171 | |

| Langmuir | KL (dm3/mg) | 0.501 | 0.442 | 3.201 |

| qm (mg/g) | 26 | 26 | 165.289 | |

| R2 | 0.909 | 0.933 | 0.673 | |

| Adj2 | 0.861 | 0.920 | 0.564 | |

| Freundlich | KF (mg/g(dm3/mg)1/n) | 12.320 | 17.117 | 139.072 |

| 1/n | 0.252 | 0.0110 | 0.061 | |

| R2 | 0.984 | 0.970 | 0.977 | |

| Adj2 | 0.968 | 0.953 | 0.955 | |

| Sample | Temperature (°C) | ∆G0 (kJ/mol) | ∆H0 (kJ/mol) | ∆S0 (J/mol × K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS-A4 | 25 | −4.48 | 41.52 | 155.15 |

| 35 | −6.75 | |||

| 45 | −7.55 | |||

| CS-A5 | 25 | −3.96 | 14.71 | 62.86 |

| 35 | −4.94 | |||

| 45 | −5.05 | |||

| CS-A6 | 25 | −7.10 | 35.78 | 143.41 |

| 35 | −8.09 | |||

| 45 | −9.99 |

| Sample | Temperature (°C) | ∆G0 (kJ/mol) | ∆H0 (kJ/mol) | ∆S0 (J/mol × K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS-A4 | 25 | −1.45 | 33.07 | 115.78 |

| 35 | −2.54 | |||

| 45 | −3.77 | |||

| CS-A5 | 25 | −1.74 | 20.27 | 73.18 |

| 35 | −1.83 | |||

| 45 | −3.24 | |||

| CS-A6 | 25 | −5.22 | 28.69 | 113.99 |

| 35 | −6.53 | |||

| 45 | −7.49 |

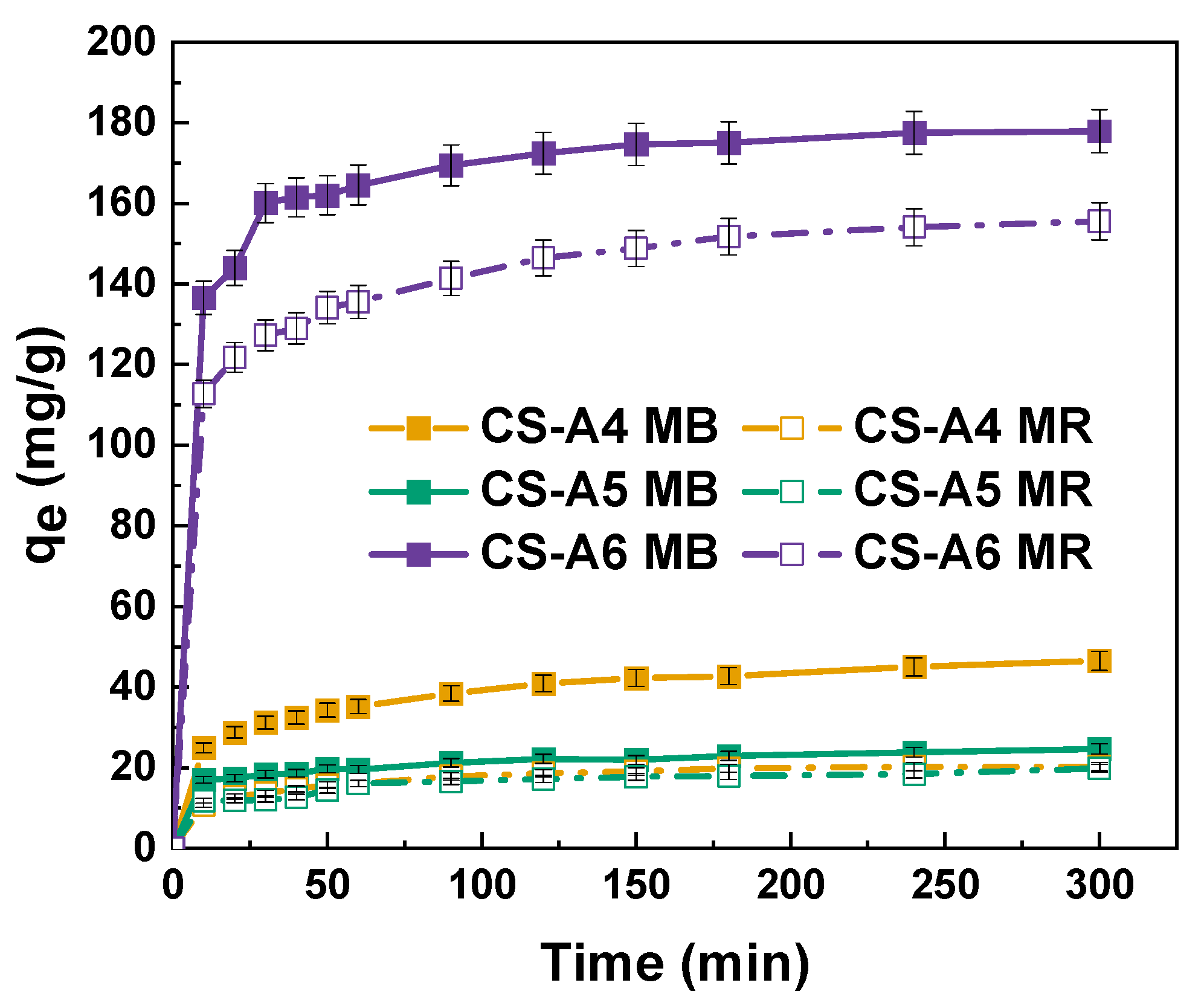

| Kinetics Model | Parameters | Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS-A4 | CS-A5 | CS-A6 | ||

| qe (mg/g) | 53 | 33 | 197 | |

| Pseudo-first-order | k1 (1/min) | 1.51 × 10−5 | 7.07 × 10−6 | 1.19 × 10−5 |

| R2 | 0.966 | 0.952 | 0.781 | |

| qe/cal (mg/g) | 24 | 16 | 44 | |

| Pseudo-second-order | k2 (g/mg × min) | 2.31 × 10−3 | 3.26 × 10−3 | 8.61 × 10−3 |

| R2 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.999 | |

| qe/cal (mg/g) | 50 | 31 | 198 | |

| Kinetics Model | Parameters | Sample | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS-A4 | CS-A5 | CS-A6 | ||

| qe (mg/g) | 21 | 22 | 156 | |

| Pseudo-first-order | k1 (1/min) | 3.36 × 10−5 | 1.58 × 10−5 | 4.32 × 10−5 |

| R2 | 0.956 | 0.926 | 0.996 | |

| qe/cal (mg/g) | 9 | 10 | 46 | |

| Pseudo-second-order | k2 (g/mg × min) | 2.62 × 10−3 | 2.30 × 10−3 | 5.11 × 10−3 |

| R2 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | |

| qe/cal (mg/g) | 21 | 20 | 159 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paluch, D.; Bazan-Wozniak, A.; Pietrzak, R. Microwave-Assisted Chemical Activation of Caraway Seeds with Potassium Carbonate for Activated Carbon Production: Physicochemical Characterization and Adsorption Study. Molecules 2025, 30, 3804. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30183804

Paluch D, Bazan-Wozniak A, Pietrzak R. Microwave-Assisted Chemical Activation of Caraway Seeds with Potassium Carbonate for Activated Carbon Production: Physicochemical Characterization and Adsorption Study. Molecules. 2025; 30(18):3804. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30183804

Chicago/Turabian StylePaluch, Dorota, Aleksandra Bazan-Wozniak, and Robert Pietrzak. 2025. "Microwave-Assisted Chemical Activation of Caraway Seeds with Potassium Carbonate for Activated Carbon Production: Physicochemical Characterization and Adsorption Study" Molecules 30, no. 18: 3804. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30183804

APA StylePaluch, D., Bazan-Wozniak, A., & Pietrzak, R. (2025). Microwave-Assisted Chemical Activation of Caraway Seeds with Potassium Carbonate for Activated Carbon Production: Physicochemical Characterization and Adsorption Study. Molecules, 30(18), 3804. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30183804