Asphalt as a Plasticizer for Natural Rubber in Accelerated Production of Rubber-Modified Asphalt

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Method

2.2.1. TSNR Compound (CTSNR) Production

2.2.2. Production of CTSNR Modified Asphalt (CTSNRMA)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Performance Evaluation of CTSNR Homogenization Time in Asphalt Matrix

3.2. Penetration

3.3. Softening Point

3.4. Storage Stability

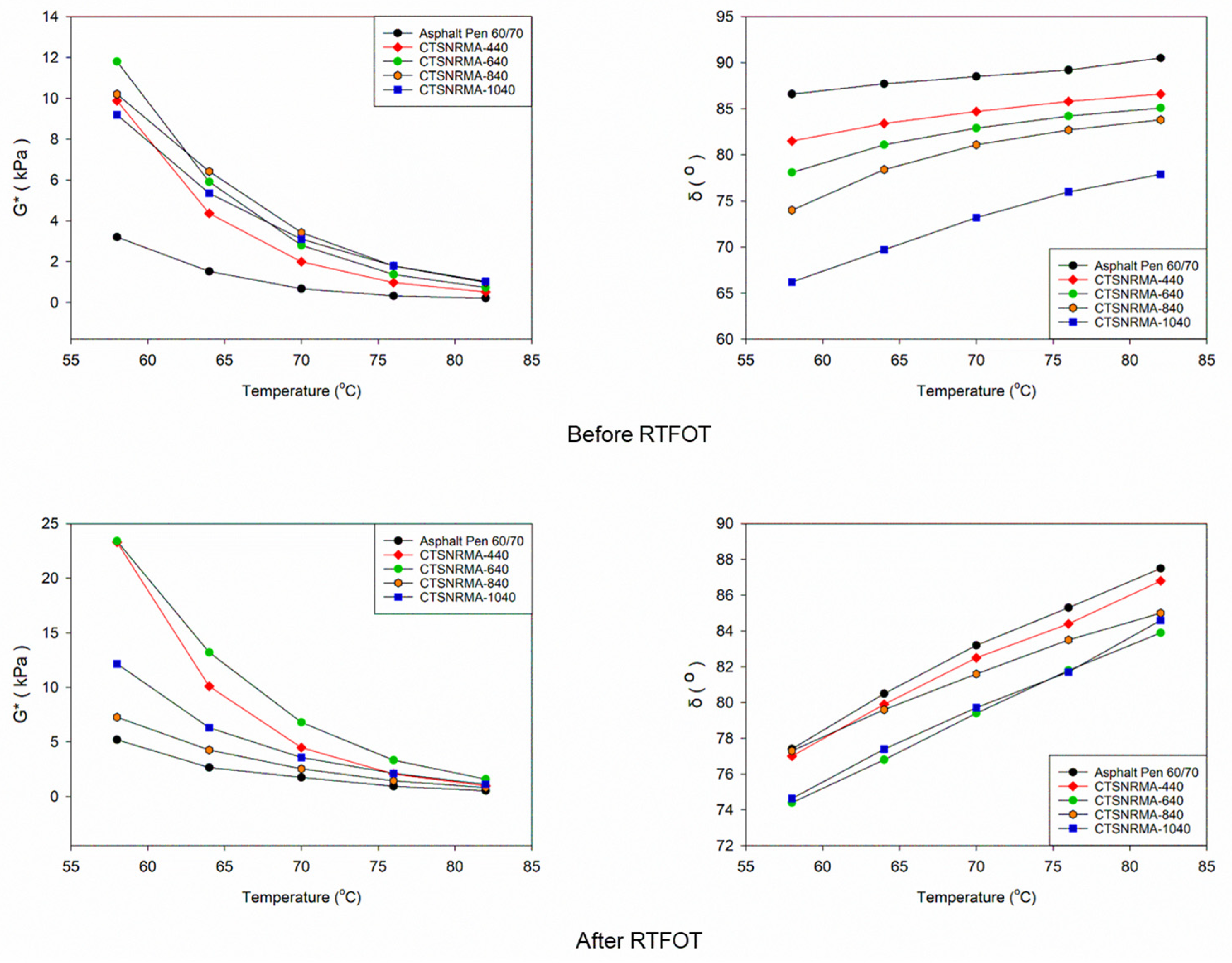

3.5. Dynamic Shear Rheometer (DSR)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moreno-Navarro, F.; Sol-Sánchez, M.; Rubio-Gámez, M.C. The effect of polymer modified binders on the long-term performance of bituminous mixtures: The influence of temperature. Mater. Des. 2015, 78, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Cao, X.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Tang, B.; Shan, B. Dynamic chemistry approach for self-healing of polymer-modified asphalt: A state-of-the-art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 403, 133128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheet, S.H.; Latief, R.H. Assessment of the properties of asphalt mixtures modified with LDPE and HDPE polymers. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2024, 21, 2024265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Huan, H.; Guo, R.; He, Y.; Tang, K. Effect of vulcanisation on the properties of natural rubber-modified asphalt. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 214, 118588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B.; Wiranata, A.; Malik, A. The effect of addition of antioxidant 1,2-dihydro-2,2,4-trimethyl-quinoline on characteristics of crepe rubber modified asphalt in short term aging and long term aging conditions. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Chen, M.; Geng, J.; Liao, X.; Chen, Z. Swelling and Degradation Characteristics of Crumb Rubber Modified Asphalt during Processing. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6682905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Erkens, S.; Skarpas, A. Experimental characterization of storage stability of crumb rubber modified bitumen with warm-mix additives. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 249, 118840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasileiro, L.; Moreno-Navarro, F.; Tauste-Martínez, R.; Matos, J.; Rubio-Gámez, M.d.C. Reclaimed polymers as asphalt binder modifiers for more sustainable roads: A review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B.; Wiranata, A.; Zahrina, I.; Sentosa, L.; Nasruddin, N.; Muharam, Y. Phase Separation Study on the Storage of Technically Specification Natural Rubber Modified Bitumen. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xiao, F.; Zhu, X.; Huang, B.; Wang, J.; Amirkhanian, S. Energy consumption and environmental impact of rubberized asphalt pavement. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 180, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.Z.; Wang, N.N.; Tseng, M.L.; Huang, Y.M.; Li, N.L. Waste tire recycling assessment: Road application potential and carbon emissions reduction analysis of crumb rubber modified asphalt in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyelere, A.; Wu, S. State of the art review on the principles of compatibility and chemical compatibilizers for recycled plastic-modified asphalt binders. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 492, 144895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhou, H.; Hu, W.; Polaczyk, P.; Zhang, M.; Huang, B. Compatibility and rheological characterization of asphalt modified with recycled rubber-plastic blends. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 270, 121416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Wang, T.J.; Lee, C.T. Evaluation of a highly-modified asphalt binder for field performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 171, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, M.; Bala, N.; Al Zaro, K.; Sunarjono, S. Properties of Crumb Rubber and Latex Modified Asphalt Binders using Superpave Tests. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 203, 05007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, J.; Whiteoak, D. The Shell Bitumen Handbook, 6th ed.; Thomas Telford: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Y.; Méndez, M.P.; Rodríguez, Y. Polymer modified asphalt. Vis. Tecnol. 2001, 9, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez, F.; Marcobal, J.; Gallego, J. Laboratory evaluation of the mechanical properties of asphalt mixtures with rubber incorporated by the wet, dry, and semi-wet process. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 205, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, N.A.; Yusoff, N.I.M.; Jafri, S.F.; Sheeraz, K. Rheological Findings on Storage Stability for Chemically Dispersed Crumb Rubber Modified Bitumen. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 305, 124768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahruddin; Arya, W.; Yanny, S.; Alfian, M. Effects of cup lump natural rubber as an additive on the characteristics of asphalt-rubber products. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 845, 012050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahruddin; Wiranata, A.; Malik, A.; Kumar, R.; Permata, D.S. Pembuatan Aspal Modifikasi Polimer Berbasis Karet Alam Tanpa dan Dengan Mastikasi. Indones. J. Ind. Res. 2019, 2, 260–269. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sabaeei, A.; Nur, N.I.; Napiah, M.; Sutanto, M. A review of using natural rubber in the modification of bitumen and asphalt mixtures used for road construction. J. Teknol. 2019, 81, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahruddin; Wiranata, A.; Malik, A. The effect of technical natural rubber mastication with wet process mixing on the characteristics of asphalt-rubber blend. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2049, 012081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohayzi, N.F.; Katman, H.Y.B.; Ibrahim, M.R.; Norhisham, S.; Rahman, N.A. Potential Additives in Natural Rubber-Modified Bitumen: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mansob, R.A.; Ismail, A.; Md Yusoff, N.I.; Azhari, C.H.; Karim, M.R.; Alduri, A.; Baghini, M.S. Rheological characteristics of epoxidized natural rubber modified bitumen. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 505–506, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, R.; Suherman. Temperature sensitivity effect in asphalt modification with natural rubber sir20. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 650, 012045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadhan, A.; Puspitasari, S.; Prastanto, H.; Falaah, A.F.; Maspanger, D.R.; Andriani, W.; Faturrohman, M.I.; Sofyan, T.S.; Firdaus, Y. Development of Rubberized Asphalt Technology Based on Asphalt Cement (AC Pen 60) and Fresh Natural Rubber in Indonesia. Macromol. Symp. 2020, 391, 2000075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahruddin; Wiranata, A.; Malik, A. Effects of 1,2-dihydro-2,2,4-trimethyl-quinoline (TMQ) antioxidant on the Marshall characteristics of crepe rubber modified asphalt. Key Eng. Mater. 2021, 876, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Birgisson, B.; Kringos, N. Polymer modification of bitumen: Advances and challenges. Eur. Polym. J. 2014, 54, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Lu, X.; Kringos, N. Experimental investigation on storage stability and phase separation behaviour of polymer-modified bitumen. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2018, 19, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayeemasae, N.; Waesateh, K.; Soontaranon, S.; Masa, A. The effect of mastication time on the physical properties and structure of natural rubber. J. Elastomers Plast. 2021, 53, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Kong, H.; Luo, K.; Wang, M.; Yong, Z. Characterization of the molecular structure of masticated natural rubber using rheological techniques. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Geng, X. Plasticization and Polymer Morphology. In Innovations in Food Packaging, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasruddin; Susanto, T. The Effect of Natural Based Oil as Plasticizer towards Physics-Mechanical Properties of NR-SBR Blending for Solid Tyres. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1095, 012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasruddin; Setianto, W.B.; Yohanes, H.; Atmaji, G.; Lanjar; Yanto, D.H.Y.; Wulandari, E.P.; Wiranata, A.; Ibrahim, B. Characterization of Natural Rubber, Styrene Butadiene Rubber, and Nitrile Butadiene Rubber Monomer Blend Composites Loaded with Zinc Stearate to Be Used in the Solid Tire Industry. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canepari, S.; Castellano, P.; Astolfi, M.L.; Materazzi, S.; Ferrante, R.; Fiorini, D.; Curini, R. Release of particles, organic compounds, and metals from crumb rubber used in synthetic turf under chemical and physical stress. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 1448–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, L.; Mas-Giner, I.; Esposti, M.D.; Morselli, D.; Santana, M.H.; Fabbri, P. Competing Effects of Plasticization and Miscibility on the Structure and Dynamics of Natural Rubber: A Comparative Study on Bio and Commercial Plasticizers. ACS Polym. Au 2025, 5, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Bahia, H.; Yi-qiu, T.; Ling, C. Effects of refined waste and bio-based oil modifiers on rheological properties of asphalt binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 148, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyin, S.O.; Melekhina, V.Y.; Kostyuk, A.V.; Smirnova, N.M. Hot-Melt and Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives Based on Asphaltene/Resin Blend and Naphthenic Oil. Polymers 2022, 14, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Hyun, J.S.; Seol, I.S.; Choi, S. High Shear Viscosity Measurement of A Natural Rubber and Synthetic Rubber Materials Using the Rubber Screw Rheometer. In Proceedings of the Annual Technical Conference—ANTEC, Conference Proceedings; Society of Plastics Engineers: Danbury, CT, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Turbay, E.; Martinez-Arguelles, G.; Navarro-Donado, T.; Sánchez-Cotte, E.; Polo-Mendoza, R.; Covilla-Valera, E. Rheological Behaviour of WMA-Modified Asphalt Binders with Crumb Rubber. Polymers 2022, 14, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Guo, R.; Cheng, C.; Fu, C.; Yang, Y. Viscosity prediction model of natural rubber-modified asphalt at high temperatures. Polym. Test. 2022, 113, 107666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. Storage Stability and Phase Separation Behaviour of Polymer-Modified Bitumen: Characterization and Modelling. Doctoral Dissertation, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulrahman, S.; Hainin, M.R.; Idham, M.K.; Hassan, N.A.; Warid, M.M.; Yaacob, H.; Azman, M.; Puan, O.C. Physical properties of warm cup lump modified bitumen. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 527, 012048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, S.; Alanazi, F.; Hainin, M.R.; Albuaymi, M.; Alanazi, H.; Adamu, M.; Azam, A. Rheological and Morphological Characterization of Cup Lump Rubber-Modified Bitumen with Evotherm Additive. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 13195–13209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegenizadeh, A.; Shen, P.J.; Arumdani, I.S.; Budihardjo, M.A.; Nikraz, H. The addition of a high dosage of rubber to asphalt mixtures: The effects on rutting and fatigue. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehabe, E.E.; Nkeng, G.E.; Collet, A.; Bonfils, F. Relations between high-temperature mastication and Mooney viscosity relaxation in natural rubber. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 113, 2785–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latshaw, A.; Reddy, S.; Rauschmann, T. Rheological characterization of mixing effects on natural rubber using an RPA. Rubber World 2019, 259, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, D.; Huang, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, L. Swelling process of rubber in asphalt and its effect on the structure and properties of rubber and asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 29, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, K.; Toh, M.; Liang, X.; Nakajima, K. Influence of mastication on the microstructure and physical properties of rubber. Rubber Chem. Technol. 2021, 94, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhan, M.; Wang, S. Molecular dynamics study on the effect of rheological performance of asphalt with different plasticizers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cheng, D.; Xiao, F. Recent developments in the application of chemical approaches to rubberized asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 131, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ye, F. Experimental investigation on aging characteristics of asphalt based on rheological properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 231, 117158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnood, A.; Gharehveran, M.M. Morphology, rheology, and physical properties of polymer-modified asphalt binders. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 112, 766–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, M.; Schaur, A.; Unterberger, S.H. Polymer-bitumen interaction: A correlation study with six different bitumens to investigate the influence of sara fractions on the phase stability, swelling, and thermo-rheological properties of sbs-pmb. Materials 2021, 14, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffie, E.; Hanif, W.M.M.W.; Arshad, A.K.; Hashim, W. Rutting resistance of asphalt mixture with cup lumps modified binder. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 271, 012056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azahar, N.M.; Hassan, N.A.; Putrajaya, M.R.; Hainin, R.; Puan, O.C.; Shukry, N.A.M.; Hezmi, M.A. Engineering properties of asphalt binder modified with cup lump rubber. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 220, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofko, B.; Eberhardsteiner, L.; Füssl, J.; Grothe, H.; Handle, F.; Hospodka, M.; Grossegger, D.; Nahar, S.N.; Schmets, A.J.M.; Scarpas, A. Impact of maltene and asphaltene fraction on mechanical behavior and microstructure of bitumen. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2016, 49, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Yang, Y.; Lv, S.; Peng, X.; Zhang, Y. Investigation on preparation process and storage stability of modified asphalt binder by grafting activated crumb rubber. Materials 2019, 12, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holkar, C.; Pinjari, D.; D’Melo, D.; Bhattacharya, S. The effect of asphaltene concentration on polymer modification of bitumen with SBS copolymers. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2023, 56, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdhani, F.; Subagio, B.S.; Rahman, H.; Frazila, R.B. Rheological analysis of micro rubber SIR 20 modified asphalt. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1416, 012049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.W.; Zhang, D.W. Research on the impact of temperature on the softening point of SBS modified asphalt. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 365, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, M.A.; Dernayka, S.D.; Chowdhury, S.R. Physical properties of crumb rubber modified asphalt binders and environmental impact consideration. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 31, 7678–7692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Guo, H.; Guan, W.; Zhao, Y. A laboratory evaluation of factors affecting rutting resistance of asphalt mixtures using wheel tracking test. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushinga, N.; Cao, L.; Dong, Z.; Assogba, C.O. Improving storage stability and physicochemical performance of styrene-butadiene-styrene asphalt binder modified with nanosilica. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.; Fan, W.; Ren, F.; Lv, X.; Xing, B. Influence of polyphosphoric acid (PPA) on properties of crumb rubber (CR) modified asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 117094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.S.; Singh, S.K.; Ransinchung, G.D.; Ravindranath, S.S. Effect of property deterioration in SBS modified binders during storage on the performance of asphalt mix. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Hou, W. Influence of storage conditions on the stability of asphalt emulsion. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2017, 35, 1217–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhang, J.; Pei, J.; Ma, W.; Hu, Z.; Guan, Y. Evaluation of the compatibility between rubber and asphalt based on molecular dynamics simulation. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2020, 14, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Xin, X.; Fan, W.; Sun, H.; Yao, Y.; Xing, B. Viscous properties, storage stability and their relationships with microstructure of tire scrap rubber modified asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 74, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Apostolidis, P.; Erkens, S.; Skarpas, A. Experimental Investigation of Rubber Swelling in Bitumen. Transp. Res. Rec. 2020, 2674, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lepe, A.; Martínez-Boza, F.J.; Attané, P.; Gallegos, C. Destabilization mechanism of polyethylene-modified bitumen. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 100, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Qiao, X.; Yu, R.; Yu, X.; Liu, J.; Yu, J.; Xia, R. Influence of modification process parameters on the properties of crumb rubber/EVA modified asphalt. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Liu, X.; Fan, W.; Wang, H.; Erkens, S. Rheological Properties, Compatibility, and Storage Stability of SBS Latex-Modified Asphalt. Materials 2019, 12, 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Li, R.; Liu, T.; Pei, J.; Li, Y.; Luo, Q. Study on the effect of microwave processing on asphalt-rubber. Materials 2020, 13, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.A.; Underwood, B.S.; Castorena, C. Low-temperature performance grade characterisation of asphalt binder using the dynamic shear rheometer. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2022, 23, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Walubita, L.F.; Faruk, A.N.M.; Karki, P.; Simate, G.S. Use of the MSCR test to characterize the asphalt binder properties relative to HMA rutting performance—A laboratory study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 94, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Sun, L.; Duan, D.; Zhang, B.; Wang, G.; Zhang, S.; Yu, W. Enhancing the Storage Stability and Rutting Resistance of Modified Asphalt through Surface Functionalization of Waste Tire Rubber Powder. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H.-G.T.; Mai, H.-V.T.; Nguyen, H.L.; Ly, H.-B. Application of extreme gradient boosting in predicting the viscoelastic characteristics of graphene oxide modified asphalt at medium and high temperatures. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2024, 18, 899–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, W. Dynamic viscoelastic properties of SBS modified asphalt based on DSR testing. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 598, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jexembayeva, A.; Konkanov, M.; Aruova, L.; Zhaksylykova, L.; Baidaulet, Z. Preparation of polymer bitumen binder in the presence of a stabilizer. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2025, 65, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.C.; Guo, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.S.; Xue, Z.C. Analysis of effects of high temperature on asphalt binder. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 325, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Fan, S.; Xu, T. Method for Evaluating Compatibility between SBS Modifier and Asphalt Matrix Using Molecular Dynamics Models. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04021207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Yuan, D.; Tong, Z.; Sha, A.; Xiao, J.; Jia, M.; Ye, W.; Wang, W. Aging effects on rheological properties of high viscosity modified asphalt. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 10, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.H.; Suresha, S.N. Investigation of aging effect on asphalt binders using thin film and rolling thin film oven test. Adv. Civ. Eng. Mater. 2019, 8, 637–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Peng, C.; Chen, J.; Liu, G.; He, X. Effect of short-term aging on rheological properties of bio-asphalt/SBS/PPA composite modified asphalt. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lv, S.; Liu, J.; Peng, X.; Lu, W.; Wang, Z.; Xie, N. Performance evaluation of aged asphalt rejuvenated with various bio-oils based on rheological property index. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwanuakwa, I.D.; Ali, S.I.A.; Hasan, M.R.M.; Akpinar, P.; Sani, A.; Shariff, K.A. Artificial intelligence prediction of rutting and fatigue parameters in modified asphalt binders. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Zhang, N.; Lv, S.; Cabrera, M.B.; Yuan, J.; Fan, X.; Liu, H. Correlation Analysis of Chemical Components and Rheological Properties of Asphalt After Aging and Rejuvenation. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 04022303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Material | Specification | Content (phr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Technically Specified Natural Rubber (TSNR) | Dry Rubber Content (DRC) 98%, 0.02% impurity content, and a plasticity retention index (PRI) of 50, Specific Gravity is approximately 0.92 g/cm3. | 100 |

| 2 | Zinc Oxide | Technical specifications with 99% purity | 6 |

| 3 | Stearic Acid | Technical specifications with 99% purity | 2 |

| 4 | Mercaptobenzothiazole sulfenamide (MBTS) | Technical specifications Production RICHON offers 98% purity | 3 |

| 5 | 2,2,4-Trimethyl-1,2-dihydroquinoline (TMQ) | Technical specifications Production SINOPEC offers 98% purity | 1 |

| 6 | Asphalt Penetration 60/70 | Penetration 60/70 | 30 |

| Component | CTSNR Composition (g) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTSNR-430 | CTSNR-440 | CTSNR-450 | CTSNR-640 | CTSNR-650 | CTSNR-840 | CTSNR-850 | CTSNR-1040 | CTSNR-1050 | |

| TSNR | 62.5 | 53.6 | 44.6 | 53.5 | 44.6 | 53.5 | 44.6 | 53.6 | 44.6 |

| Zinc Oxide | 3.8 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 2.7 |

| Stearic Acid | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| MBTS | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| TMQ | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Plasticizer (asphalt) | 30.0 | 40.0 | 50.0 | 40.0 | 50.0 | 40.0 | 50.0 | 40.0 | 50.0 |

| Component | Composition CTSNRMA (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTSNRMA-430 | CTSNRMA-440 | CTSNRMA-450 | CTSNRMA-640 | CTSNRMA-650 | CTSNRMA-840 | CTSNRMA-850 | CTSNRMA-1040 | CTSNRMA-1050 | |

| Asphalt | 93.63 | 92.57 | 91.08 | 88.88 | 86.66 | 85.21 | 82.25 | 81.55 | 77.87 |

| CTSNR | 6.37 | 7.43 | 8.92 | 11.12 | 13.34 | 14.79 | 17.75 | 18.45 | 22.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ibrahim, B.; Helwani, Z.; Jahrizal; Nasruddin; Wiranata, A.; Kurniawan, E.; Mashitoh, A.S. Asphalt as a Plasticizer for Natural Rubber in Accelerated Production of Rubber-Modified Asphalt. Constr. Mater. 2026, 6, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater6010004

Ibrahim B, Helwani Z, Jahrizal, Nasruddin, Wiranata A, Kurniawan E, Mashitoh AS. Asphalt as a Plasticizer for Natural Rubber in Accelerated Production of Rubber-Modified Asphalt. Construction Materials. 2026; 6(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater6010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbrahim, Bahruddin, Zuchra Helwani, Jahrizal, Nasruddin, Arya Wiranata, Edi Kurniawan, and Anjar Siti Mashitoh. 2026. "Asphalt as a Plasticizer for Natural Rubber in Accelerated Production of Rubber-Modified Asphalt" Construction Materials 6, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater6010004

APA StyleIbrahim, B., Helwani, Z., Jahrizal, Nasruddin, Wiranata, A., Kurniawan, E., & Mashitoh, A. S. (2026). Asphalt as a Plasticizer for Natural Rubber in Accelerated Production of Rubber-Modified Asphalt. Construction Materials, 6(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/constrmater6010004