Glycemic Cluster Analysis of Non-Diabetic Japanese Individuals Using the Triglyceride-Glucose Index Identifies an At-Risk Group for Incident Cardiovascular Disease Independent of Impaired Glucose Tolerance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Parameters Measured

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characteristics of the Participants at the Baseline

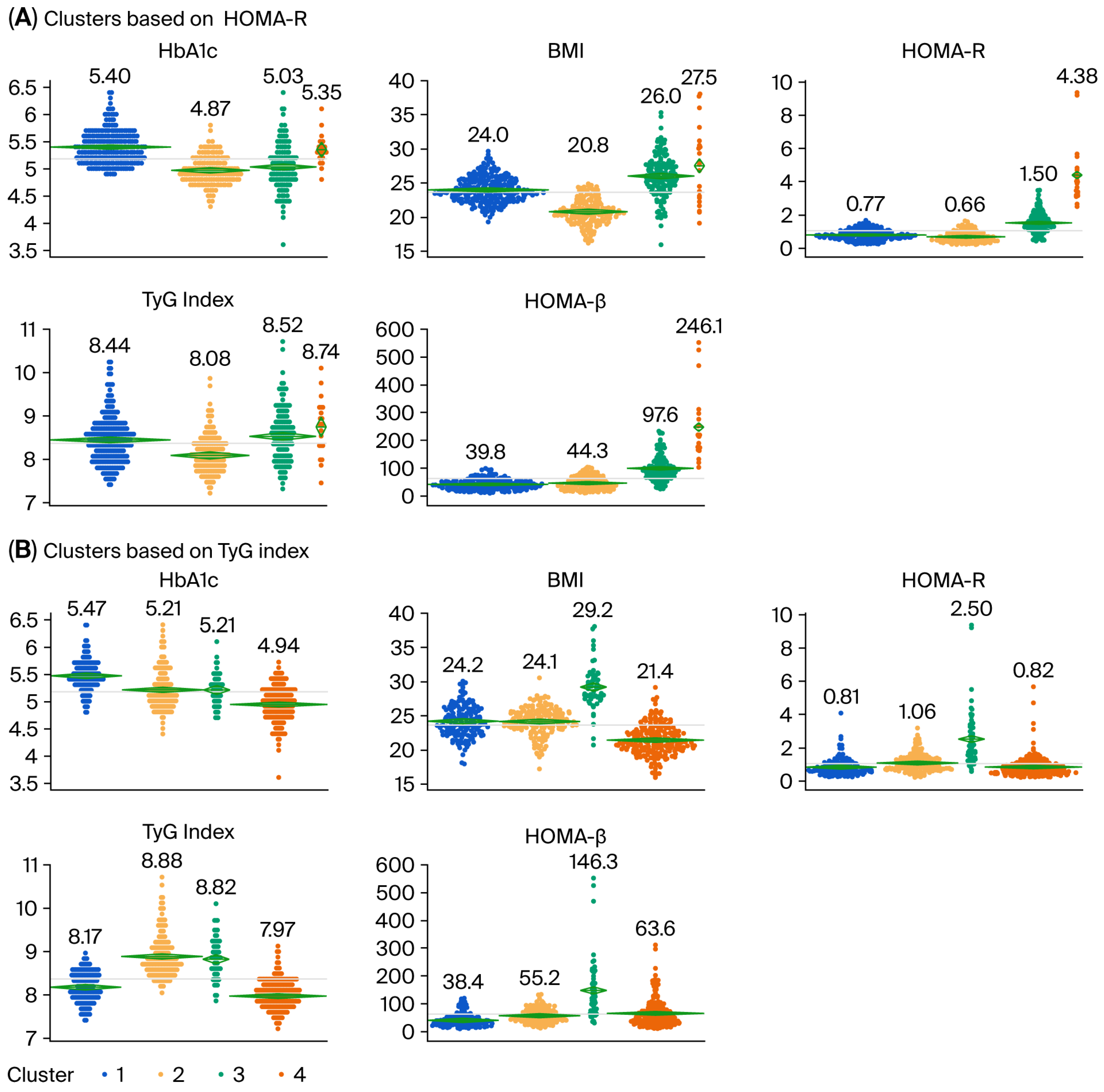

3.2. Cluster Analysis Using Four Variables

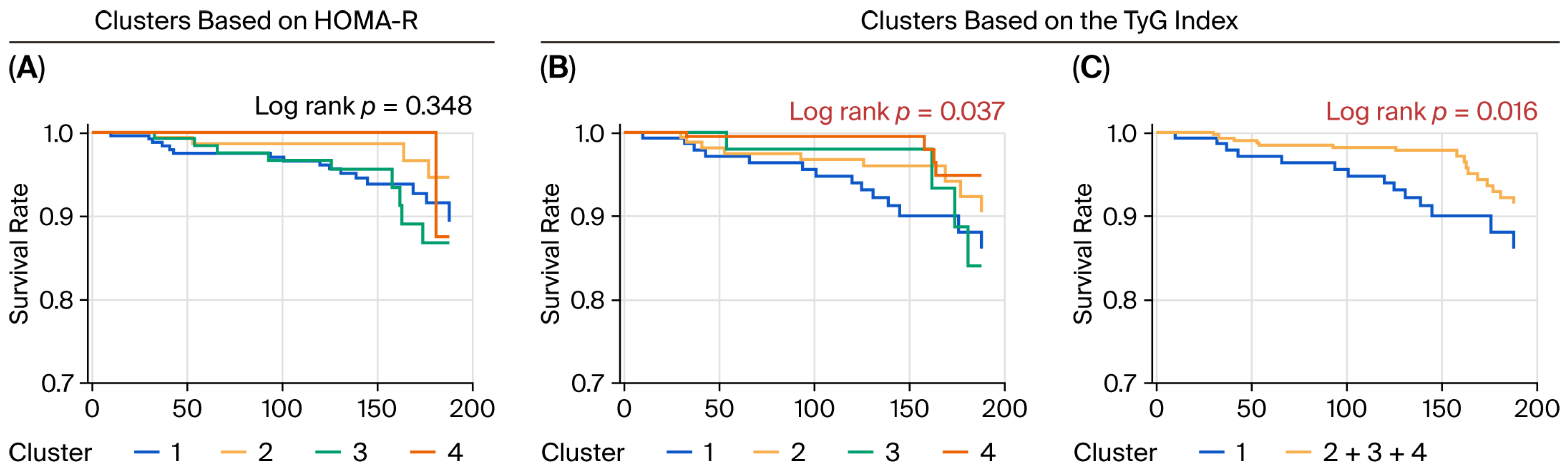

3.3. Risk of Incident CVD Associated with the Clusters

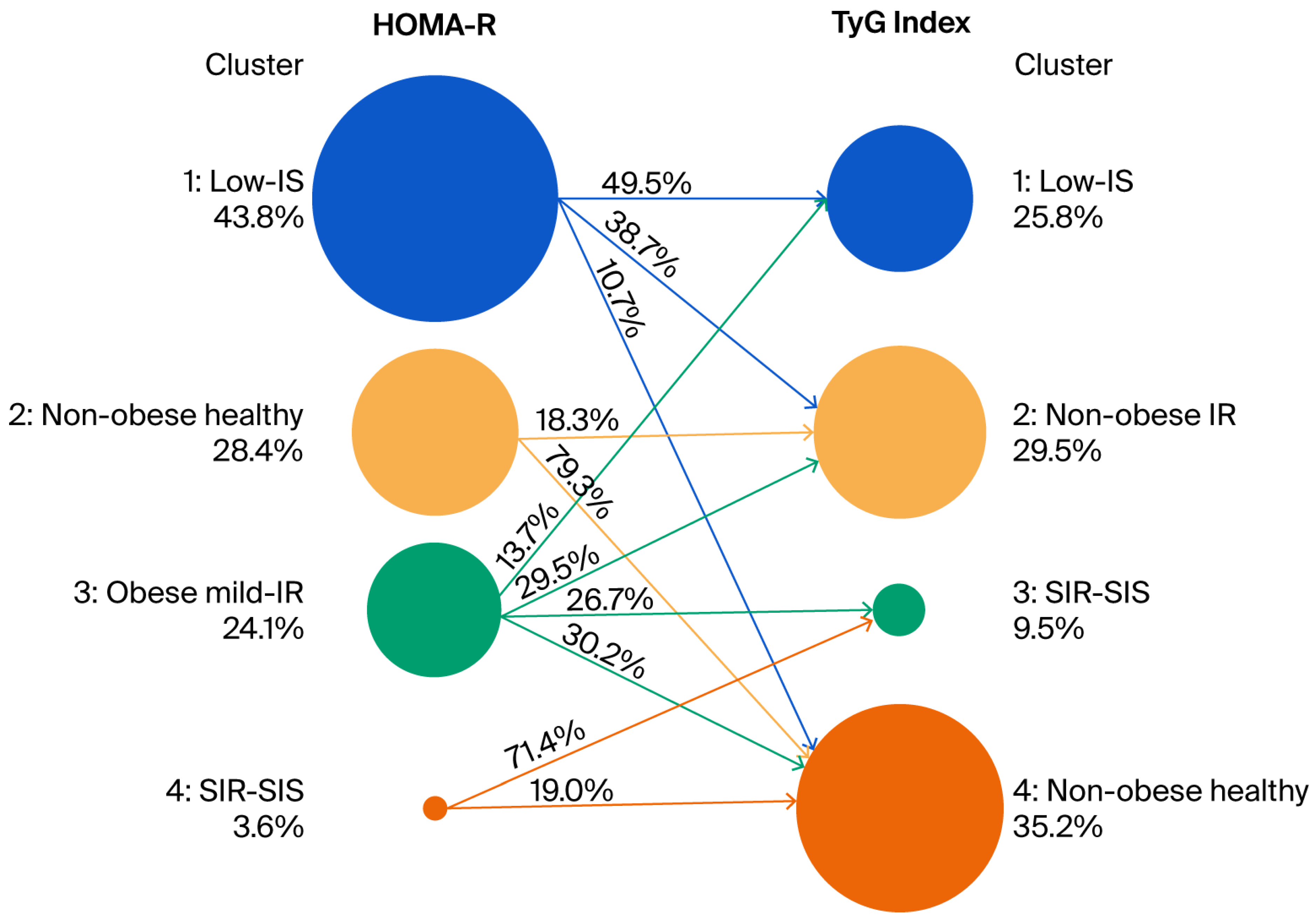

3.4. Relationship Between Clusters Defined by Cluster Analysis Using the HbA1c Level, BMI, HOMA-β, and HOMA-R and Clusters Defined by Cluster Analysis Using the HbA1c Level, BMI, HOMA-β, and TyG Index

3.5. Risk of Incident CVD in the Low-IS (TyG) Cluster Was Independent of Risk of Incident CVD Associated with IGT

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| HOMA-β | Homeostatic model assessment estimates of β-cell function |

| HOMA-R | Homeostatic model assessment estimates of insulin resistance |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| IGT | Impaired glucose tolerance |

| TyG | The triglyceride glucose |

| FPG | Fasting blood glucose |

| FI | Fasting serum insulin |

| HbA1c | Glycated hemoglobin |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| IR | Insulin resistance |

| SIR-SIS | Severely insulin resistant with sufficient compensatory insulin secretion |

| Low-IS | Low insulin secretion |

References

- Stumvoll, M.; Goldstein, B.J.; van Haeften, T.W. Type 2 diabetes: Principles of pathogenesis and therapy. Lancet 2005, 365, 1333–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A. Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 88, 787–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, R.; Mizushiri, S.; Nishiya, Y.; Ono, S.; Tamura, A.; Hamaura, K.; Terada, A.; Tanabe, J.; Yanagimachi, M.; Wai, K.M.; et al. Two Distinct Groups Are Shown to Be at Risk of Diabetes by Means of a Cluster Analysis of Four Variables. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Rodríguez-Morán, M.; Guerrero-Romero, F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2008, 6, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Placzkowska, S.; Pawlik-Sobecka, L.; Kokot, I.; Piwowar, A. Indirect insulin resistance detection: Current clinical trends and laboratory limitations. Biomed. Pap. Med. Fac. Univ. Palacky. Olomouc. Czech. Repub. 2019, 163, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasques, A.C.; Novaes, F.S.; de Oliveira, M.S.; Souza, J.R.; Yamanaka, A.; Pareja, J.C.; Tambascia, M.A.; Saad, M.J.; Geloneze, B. TyG index performs better than HOMA in a Brazilian population: A hyperglycemic clamp validated study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2011, 93, e98–e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Kwon, H.S.; Park, Y.M.; Ha, H.S.; Jeong, S.H.; Yang, H.K.; Lee, J.H.; Yim, H.W.; Kang, M.I.; Lee, W.C.; et al. Predicting the development of diabetes using the product of triglycerides and glucose: The Chungju Metabolic Disease Cohort (CMC) study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Íñigo, L.; Navarro-González, D.; Fernández-Montero, A.; Pastrana-Delgado, J.; Martínez, J.A. The TyG index may predict the development of cardiovascular events. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 46, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Ahn, C.W.; Lee, B.K.; Kang, S.; Nam, J.S.; You, J.H.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, M.K.; Park, J.S. Association between triglyceride glucose index and arterial stiffness in Korean adults. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Peng, Y.; Fang, Q.; Mu, Q.; Gu, W.; Hong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W. Stronger association of triglyceride glucose index than the HOMA-IR with arterial stiffness in patients with type 2 diabetes: A real-world single-centre study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.C.; Xu, J.N.; Wang, T.T.; Hua, F.; Li, J.J. Triglyceride-glucose index as a marker in cardiovascular diseases: Landscape and limitations. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2022, 21, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, M.; Eguchi, H.; Manaka, H.; Igarashi, K.; Kato, T.; Sekikawa, A. Impaired glucose tolerance is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, but not impaired fasting glucose. The Funagata Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 1999, 22, 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oizumi, T.; Daimon, M.; Jimbu, Y.; Wada, K.; Kameda, W.; Susa, S.; Yamaguchi, H.; Ohnuma, H.; Tominaga, M.; Kato, T. Impaired glucose tolerance is a risk factor for stroke in a Japanese sample—The Funagata study. Metabolism 2008, 57, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brannick, B.; Dagogo-Jack, S. Prediabetes and cardiovascular disease. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 47, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee of the Japan Diabetes Society on the Diagnostic Criteria of Diabetes Mellitus; Seino, Y.; Nanjo, K.; Tajima, N.; Kadowaki, T.; Kashiwagi, A.; Araki, E.; Ito, C.; Inagaki, N.; Iwamoto, Y.; et al. Report of the committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Investig. 2010, 1, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Nagai, M.; Ohkubo, T. Epidemiology of hypertension in Japan: Where are we now? Circ. J. 2013, 77, 2226–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daimon, M.; Oizumi, T.; Saitoh, T.; Kameda, W.; Hirata, A.; Yamaguchi, H.; Ohnuma, H.; Igarashi, M.; Tominaga, M.; Kato, T. Decreased serum levels of adiponectin are a risk factor for the progression to type 2 diabetes in the Japanese Population: The Funagata study. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 2015–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hata, J.; Ninomiya, T.; Hirakawa, Y.; Nagata, M.; Mukai, N.; Gotoh, S.; Fukuhara, M.; Ikeda, M.; Shikata, K.; Yoshida, D.; et al. Secular trends in cardiovascular disease and its risk factors in Japanese: Half-century data from the Hisayama Study (1961–2009). Circulation 2013, 128, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T.; Saitoh, S.; Takagi, S.; Ohnishi, H.; Ohata, J.; Takeuchi, H.; Isobe, T.; Chiba, Y.; Katoh, N.; Akasaka, H.; et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic arteriosclerosis obliterans and its relationship with risk factors in inhabitants of rural communities in Japan: Tanno-Sobetsu study. Atherosclerosis 2004, 177, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal, V.; Nair, S.; Elfeky, O.; Aguayo, C.; Salomon, C.; Zuñiga, F.A. Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmas, C.E.; Bousvarou, M.D.; Kostara, C.E.; Papakonstantinou, E.J.; Salamou, E.; Guzman, E. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 3000605231164548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Shen, W.; Li, J.; Wang, B.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gao, L.; Xu, F.; Xiao, X.; Wang, N.; et al. Association between glycemia risk index and arterial stiffness in type 2 diabetes. J. Diabetes Investig. 2024, 15, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torimoto, K.; Okada, Y.; Mita, T.; Tanaka, K.; Sato, F.; Katakami, N.; Yoshii, H.; Nishida, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Ishii, R.; et al. Association of Glycaemia Risk Index With Indices of Atherosclerosis: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Diabetes 2025, 17, e70065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonoff, D.C.; Wang, J.; Rodbard, D.; Kohn, M.; Li, C.; Liepmann, D.; Kerr, D.; Ahn, D.; Peters, A.L.; Umpierrez, G.E.; et al. A glycemia risk index (GRI) of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia for continuous glucose monitoring validated by clinician ratings. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2023, 17, 1226–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oriot, P.; Prévost, G.; Philips, J.C.; Klipper Dit Kurz, N.; Hermans, M.P. Glycemia risk index (GRI): A metric designed to facilitate the interpretation of continuous glucose monitoring data: A narrative review. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2025, 48, 1995–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlqvist, E.; Storm, P.; Käräjämäki, A.; Martinell, M.; Dorkhan, M.; Carlsson, A.; Vikman, P.; Prasad, R.B.; Aly, D.M.; Almgren, P.; et al. Novel subgroups of adult-onset diabetes and their association with outcomes: A data-driven cluster analysis of six variables. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, J.M.; Shields, B.M.; Henley, W.E.; Jones, A.G.; Hattersley, A.T. Disease progression and treatment response in data-driven subgroups of type 2 diabetes compared with models based on simple clinical features: An analysis using clinical trial data. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaharia, O.P.; Strassburger, K.; Strom, A.; Bönhof, G.J.; Karusheva, Y.; Antoniou, S.; Bódis, K.; Markgraf, D.F.; Burkart, V.; Müssig, K.; et al. Risk of diabetes-associated diseases in subgroups of patients with recent-onset diabetes: A 5-year follow-up study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanabe, H.; Saito, H.; Kudo, A.; Machii, N.; Hirai, H.; Maimaituxun, G.; Tanaka, K.; Masuzaki, H.; Watanabe, T.; Asahi, K.; et al. Factors Associated with Risk of Diabetic Complications in Novel Cluster-Based Diabetes Subgroups: A Japanese Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahkoska, A.R.; Geybels, M.S.; Klein, K.R.; Kreiner, F.F.; Marx, N.; Nauck, M.A.; Pratley, R.E.; Wolthers, B.O.; Buse, J.B. Validation of distinct type 2 diabetes clusters and their association with diabetes complications in the DEVOTE, LEADER and SUSTAIN-6 cardiovascular outcomes trials. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2020, 22, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugner, M.; Gudbjörnsdottir, S.; Sattar, N.; Svensson, A.M.; Miftaraj, M.; Eeg-Olofsson, K.; Eliasson, B.; Franzén, S. Comparison between data-driven clusters and models based on clinical features to predict outcomes in type 2 diabetes: Nationwide observational study. Diabetologia 2021, 64, 1973–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, X.F.; Yang, Y.; Wei, L.; Xiao, Y.; Li, L.; Sun, L. Identification of two novel subgroups in patients with diabetes mellitus and their association with clinical outcomes: A two-step cluster analysis. J. Diabetes Investig. 2021, 12, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, R.; Heni, M.; Tabák, A.G.; Machann, J.; Schick, F.; Randrianarisoa, E.; Hrabě de Angelis, M.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Norbert Stefan, N.; Peter, A.; et al. Pathophysiology-based subphenotyping of individuals at elevated risk for type 2 diabetes. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yabe, D.; Seino, Y.; Fukushima, M.; Seino, S. β cell dysfunction versus insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes in East Asians. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2015, 15, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number (Male/Female) | 577 (265/312) |

| Age (year) | 50.3 ± 10.9 |

| Height (cm) | 158.0 ± 8.8 |

| Body weight (kg) | 59.3 ± 10.5 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.7 ± 3.2 |

| Plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 92.2 ± 9.1 |

| Insulin (mU/mL) | 4.6 ± 3.9 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.18 ± 0.38 |

| HOMA-R | 1.06 ± 0.92 |

| HOMA-β | 62.5 ± 56.2 |

| Body fat (%) | 16.7 ± 13.5 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 196.8 ± 36.5 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 112.5 ± 90.4 |

| TyG index | 8.371 ± 0.566 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 56.3 ± 13.7 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 122.5 ± 17.3 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 74.7 ± 11.6 |

| Hypertension: n (%) | 209 (36.2) |

| Hyperlipidemia: n (%) | 198 (34.3) |

| Characteristics | Univariate | Age and Gender Adjusted | Multiple Factor Adjusted | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95%CI | p | HR | 95%CI | p | HR | 95%CI | p | |

| Age (per 1 year) | 1.00 | 0.95–1.03 | 0.905 | 1.00 | 0.97–1.03 | 0.953 | 0.98 | 0.94–1.02 | 0.309 |

| Gender (M vs. F) | 2.84 | 1.34–6.04 | 0.007 * | 2.84 | 1.34–6.04 | 0.007 * | 2.66 | 1.24–5.71 | 0.012 * |

| Hypertension | 1.07 | 0.85–2.20 | 0.855 | 1.07 | 0.46–2.45 | 0.881 | 1.00 | 0.43–2.33 | 0.991 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.51 | 0.74–3.06 | 0.254 | 1.48 | 0.73–3.01 | 0.279 | 1.85 | 0.83–4.10 | 0.131 |

| IGT | 2.68 | 1.16–6.25 | 0.021 * | 3.16 | 1.30–7.69 | 0.011 * | 2.77 | 1.11–6.91 | 0.028 * |

| Cluster | |||||||||

| 1: Low-IS (TyG) | 4.54 | 1.49–13.78 | 0.008 * | 4.18 | 1.36–12.86 | 0.013 * | 3.92 | 1.26–12.21 | 0.019 * |

| 2: Non-obese IR (TyG) | 2.59 | 0.80–8.42 | 0.128 | 2.38 | 0.73–7.77 | 0.151 | 1.69 | 0.48–5.99 | 0.416 |

| 3: SIR-SIS (TyG) | 3.27 | 0.82–13.07 | 0.094 | 3.29 | 0.82–13.18 | 0.092 | 2.11 | 0.48–9.31 | 0.322 |

| 4: Non-obese healthy (TyG) | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - | Ref | - | - |

| Low-IS (TyG) (vs Others) | |||||||||

| Whole | 2.32 | 1.14–4.71 | 0.020 * | 2.20 | 1.07–4.52 | 0.031 * | 2.74 | 1.25–6.03 | 0.012 * |

| in non IGT | 2.53 | 1.13–5.65 | 0.024 * | 2.44 | 1.08–5.53 | 0.032 * | 3.29 | 1.32–8.18 | 0.010 * |

| in IGT | 1.30 | 0.29–5.81 | 0.731 | 1.77 | 0.37–8.35 | 0.472 | 1.66 | 0.34–8.15 | 0.534 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daimon, M.; Susa, S.; Ishii, K.; Hada, Y.; Karasawa, S. Glycemic Cluster Analysis of Non-Diabetic Japanese Individuals Using the Triglyceride-Glucose Index Identifies an At-Risk Group for Incident Cardiovascular Disease Independent of Impaired Glucose Tolerance. Diabetology 2025, 6, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120149

Daimon M, Susa S, Ishii K, Hada Y, Karasawa S. Glycemic Cluster Analysis of Non-Diabetic Japanese Individuals Using the Triglyceride-Glucose Index Identifies an At-Risk Group for Incident Cardiovascular Disease Independent of Impaired Glucose Tolerance. Diabetology. 2025; 6(12):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120149

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaimon, Makoto, Shinji Susa, Kota Ishii, Yurika Hada, and Shigeru Karasawa. 2025. "Glycemic Cluster Analysis of Non-Diabetic Japanese Individuals Using the Triglyceride-Glucose Index Identifies an At-Risk Group for Incident Cardiovascular Disease Independent of Impaired Glucose Tolerance" Diabetology 6, no. 12: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120149

APA StyleDaimon, M., Susa, S., Ishii, K., Hada, Y., & Karasawa, S. (2025). Glycemic Cluster Analysis of Non-Diabetic Japanese Individuals Using the Triglyceride-Glucose Index Identifies an At-Risk Group for Incident Cardiovascular Disease Independent of Impaired Glucose Tolerance. Diabetology, 6(12), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/diabetology6120149