Abstract

The search for natural alternatives that improve the productive efficiency and metabolic state of dairy cows has driven the use of phytogenic compounds such as silymarin, a flavonolignan extracted from Silybum marianum L. Gaertn with recognized antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and hepatoprotective properties. This study evaluated the effects of silymarin supplementation on the productive performance; milk composition; and ruminal, hematological, biochemical, and oxidative parameters of lactating Jersey cows kept in a confined system with robotic milking. Twelve cows (230 ± 30 days in lactation; 22 ± 3.5 kg/day of milk) were distributed in a crossover design, receiving a control diet (GCON) or a diet supplemented with 5 g/cow/day of silymarin (GSIL) for 28 days in each stage. Silymarin intake did not alter dry matter intake, feed efficiency, or average milk production (p > 0.05), but it increased milk fat content (4.27 × 4.02%; p = 0.05) and, consequently, milk production corrected for 4% fat (24.4 × 23.2 kg/day; p = 0.05). In the rumen environment, cows in the GSIL group showed higher concentrations of acetic acid (57.4 × 48.4 nmol/L), and total short-chain fatty acids (100.2 × 89.4 nmol/L; p = 0.01). Regarding the biochemical profile, silymarin reduced gamma-glutamyltransferase and aspartate aminotransferase activities, as well as haptoglobin levels, indicating a hepatoprotective effect, combined with a lower inflammatory response in the liver. Oxidative status was improved by decreased levels of TBARS (lipid peroxidation) and reactive oxygen species, as well as myeloperoxidase activity in the serum of cows fed silymarin (p ≤ 0.05), but there was no difference between groups for superoxide dismutase activity and glutathione levels. The inclusion of silymarin in the diet of lactating Jersey cows improved the antioxidant and hepatic profile, increased milk fat content, and favored ruminal fermentation, suggesting metabolic and productive benefits in confined systems with high physiological demands.

1. Introduction

The search for natural alternatives capable of improving the productive efficiency and metabolic state of livestock has intensified in recent decades, especially due to growing concerns about animal health, the sustainability of production systems, and restrictions on the use of synthetic additives [1,2]. Among the bioactive compounds of plant origin, silymarin—a flavonolignan complex extracted from the seeds of Silybum marianum L. Gaertn—has received attention due to its recognized antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and hepatoprotective properties [3,4]. Its composition is predominantly made up of silibinins A and B, silicristin, silidianin, and isosilibinins [5], compounds that act in the modulation of hepatic metabolism and in the protection against oxidative and inflammatory processes in different animal species [3,6,7].

The hepatoprotective effect of silymarin is due to its ability to stimulate cell regeneration and protein synthesis in hepatocytes, reduce lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress [8,9,10], and its anti-inflammatory properties are mediated by the inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) [11,12].

In dairy cows, liver metabolism is intensely challenged by high energy demand and the mobilization of body reserves [13]. This situation often results in the accumulation of toxic metabolites and oxidative overload, compromising productive performance and milk quality. In this context, the use of natural compounds such as silymarin has been proposed as a strategy to improve liver metabolism, favoring antioxidant activity and enhancing milk production [14].

Previous studies have shown that the addition of silymarin and its compounds can increase milk production and modulate liver enzymes, suggesting an improvement in liver function and integrity [9,15,16]. However, the results are still inconsistent, varying according to the level of inclusion, the physiological state of the animals, and the time of silymarin ingestion. In addition, the effects of silymarin on the rumen profile, oxidative status, and hematological and biochemical indicators in dairy cows remain poorly understood, especially in confinement systems under Brazilian conditions, focusing on Jersey cows.

Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate whether the addition of silymarin to the diet of lactating Jersey cows in a confined system with robotic milking has beneficial effects on productive performance, milk composition, ruminal, hematological, biochemical, and oxidative parameters. Our hypothesis is that silymarin, by acting as an antioxidant and hepatoprotective agent, contributes to improving metabolic efficiency and milk quality, promoting physiological and productive balance in cows in the final third of lactation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Silymarin

The silymarin used in the study is of Chinese origin (Infinity Pharma®, Cambridge, MA, USA), being a yellowish-brown powder (Figure S1) with 86% purity obtained from the seeds of the plant Silybum marianum L. Gaertn (Silybinin A + Silybinin B: 63.94%, Silychristin + Silydianin: 25.75% and Isosilybinin A + Isosilybinin B: 10.31%). The dosage used was based on a study conducted by Tedesco et al. [15] with Holstein cows during the transition period, using a commercial product with 76% purity.

2.2. Production System and Facilities

The study was conducted in the dairy cattle sector of the experimental farm of the State University of Santa Catarina (UDESC), located in the city of Guatambu, in the State of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Twelve primiparous and multiparous Jersey cows with 230 ± 30 days in milk and an average milk production of 22 ± 3.5 L were used in a crossover design. The animals were housed in a compost barn where milking was performed by a DeLaval® robotic system, model VMS™ V300 (DeLaval®, Tumba, Sweden) with fully automated processes. During milking, the animals received a pelleted concentrate limited to 3 kg/day/cow (Bovino Robô AP®, São Paulo, Brazil), the chemical composition of which is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of pelleted concentrate, corn silage, meal concentrate and Tifton 85 hay used in this experiment.

2.3. Experimental Design and Diet

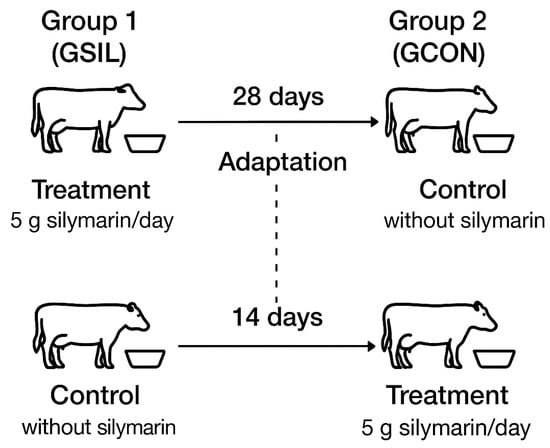

The experimental design of our study was a 28-day crossover (14 days of adaptation + 14 days of data collection). The animals were divided according to milk production into two groups of 6 cows each: Treatment (GSIL)—5 g of silymarin/day previously mixed into the meal concentrate; and Control (GCON)—without the addition of silymarin (Figure 1). In the second round, animals that were in the GCON became the GSIL, and the GSIL became the GCON; in this way, all animals went through both treatments. Both groups had water available ad libitum and received the same light and cooling management.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the 28-day crossover design. Twelve dairy cows were assigned to two groups (n = 6) and received either a control diet without silymarin (GCON) or a diet with 5 g of silymarin/day (GSIL) for 14 days of adaptation followed by 14 days of data collection.

The diets were formulated to meet the nutritional requirements of the animals according to NASEM [16]. The feeds used in the diet included concentrate meal, corn silage, and Bermuda grass (Cynodon spp.) hay, Tifton 85 variety. Animals were fed twice daily (08:00 and 14:00 h), receiving 70% of the total partially mixed ration (PMR) in individual stalls. During this period, the concentrate containing silymarin was offered to the GSIL group, whereas the concentrate without silymarin was offered to the GCON group. The remaining 30% of the PMR was provided overnight in collective feeders (Intergado®, Betim, Brazil) with free access, allowing individual animal identification and intake quantification.

2.4. Performance Parameters

We evaluated the productive performance (kg of milk) that was provided daily by the automated milking system and the milk production corrected for 4% fat using the equation LCG 4% = 0.4 × (kg of milk) + 0.15 × (% fat in milk) × (kg of milk) proposed by NRC 2001 [17]. The consumption of pelleted concentrate was also provided daily by the robotic milking system. The feed consumption data in the individual stalls were obtained by weighing the leftovers 90 min after feeding and recorded in a spreadsheet twice a day. The total feed consumption was determined by the consumption of the PMR in the individual stalls + consumption of the PMR in the collective feeding system + consumption of pelleted concentrate in the milking system. Based on these data, we calculated the feed efficiency, which is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Milk production, milk production corrected to 4%, feed intake, and feed efficiency of cows that consumed silymarin (GSIL) compared to the control (GCON).

2.5. Sample Collection

Blood samples were collected on days 14 and 28 of each experimental period. Blood was collected in tubes with clot activator (4 mL), separating the serum content for biochemical analyses, and in tubes with 10% EDTA anticoagulant (4 mL) for complete blood count. Blood samples were stored in a thermal box with ice (±8 °C) and transported to the laboratory immediately after collection. Blood from the tubes with clot activator was centrifuged (QUIMIS®, São Paulo, Brazil) for 10 min at 8000 rpm, and after complete separation, 2 mL of serum was collected and stored in a freezer (−20 °C) until analysis.

On days 1 and 28 of each experimental period, we collected individual milk samples for centesimal composition and somatic cell count (SCC) using an automatic collector specifically designed for this purpose, coupled to the robotic milking system, which collects 50 mL of milk in tubes with preservative (bronopol) and sent on the same day to a certified commercial laboratory (Parleite, Curitiba, PR, Brazil).

Rumen fluid (50 mL) was collected on day 28 of the first experimental period, 3 h after the start of feeding, using a silicone esophageal probe connected to a vacuum pump, and the pH of the samples was measured immediately after each collection with a portable pH meter (Akso, São Leopoldo, RS, Brazil). The samples were refrigerated (±8 °C) and subsequently frozen (−20 °C) to evaluate the fatty acid profile.

Two hundred and fifty grams of each feedstuff in the diet (corn silage, meal concentrate, Tifton hay, and pelleted concentrate), totaling 1 kg, were collected on days 14 and 28 of each experimental period, frozen (−20 °C), and stored until the bromatological analysis, described below.

2.6. Laboratory Analyses

2.6.1. Feed Analysis

In a forced-air oven at 54 °C for 72 h, the foods were pre-dried; then samples were transferred to another forced-air oven at 105 °C for 24 h, thus measuring the dry matter (DM) content of the foods. Crude protein was obtained after digestion, distillation, and titration processes (Kjeldahl method—2001.11) [19] Ash refers to the sample incinerated in a muffle furnace at 600 °C for 6 h. Neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF) analyses followed international methodologies [19,20]. Ether extract was determined using an automatic lipid extractor (SER 158/6 VELP® Scientifica, Usmate, Italy). All results are in Table 1.

2.6.2. Milk Solid Composition and Somatic Cell Count (SCC)

For milk solids composition and somatic cell count, milk samples were immediately sent to a commercial laboratory certified by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply in Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil. Fat, protein, lactose, total solids, non-fat dry extract, and urea were analyzed by the Mid-Infrared Spectrometry Method, according to ISO 9622—IDF Standard 141 [21]. Somatic cell count was performed by the Flow Cytometric Method according to ISO 13366-2—IDF Standard 148-2 [22].

2.6.3. Volatile Fatty Acid (VFA) Profile in the Rumen

Rumen fluid underwent a thawing process in a controlled environment of 5 °C. After this process, the samples were homogenized and then centrifuged (5 min at 12,300× g). 250 μL of the supernatant was used for the extraction of short-chain fatty acids according to the literature [23]. Subsequently, 1 μL of the sample was injected into a gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector (GC-FID; Varian Star 3400, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and an autosampler (Varian 8200CX, Palo Alto, CA, USA), operating in split mode (1:10). A standardization of the analytical methods and equipment used to identify and quantify VFAs was performed, with results expressed in nanomoles per liter (nmol L−1) in the rumen fluid.

2.6.4. Complete Blood Count

With the blood collected in EDTA tubes, we performed a complete blood count using a VET3000 automated hematology analyzer (EQUIP®, São Paulo, SP, Brazil). The equipment quantified the total leukocytes, lymphocytes, granulocytes, monocytes, erythrocytes, and platelets. In addition, it determined hemoglobin levels and hematocrit percentage.

2.6.5. Serum Biochemistry

Serum levels of albumin, bilirubin, glucose, total protein, urea, cholesterol, cholinesterase, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured using kits (ANALISA® São Paulo, SP, Brazil) and automated equipment (Zybio EXC-200® Chongqing, China). Globulin levels were calculated using (Total Protein − Albumin).

2.6.6. Proteinogram

For the separation of protein fractions from blood serum, the technique of electrophoresis in a polyacrylamide gel containing sodium sulfate was employed, as described by Fagliari et al. [24] and modified by Tomasi et al. [25], using minigels with dimensions of 10 × 10 cm. The gels were stained with Coomassie Blue and subsequently digitized for the detection and quantification of protein fractions using Labimage1D software (Loccus Biotechnology, São Paulo, Brazil, https://www.kapelanbio.com/products/apps/labimage-1d/, accessed on 18 November 2025). A molecular marker with weights ranging from 10 to 250 kDa (Kaleidoscope—BIO-RAD) was used as a reference standard.

2.6.7. Oxidative Status

The concentration of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in serum was assessed using the 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate oxidation method with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 538 nm, respectively [26]. Lipid peroxidation was quantified indirectly by measuring the levels of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) [27]. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) was determined by the oxidative coupling between phenol and 4-aminoantipyrine (AAP), forming a colored compound called quinonimine, with an absorbance of 492 nm [28].

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in the whole blood sample was determined based on the inhibition of the reaction of superoxide oxygen with adrenaline [29]. Glutathione S-transferase (GST), an antioxidant enzyme known for its role in liver detoxification, was measured in serum using the method of Habig et al. [30].

All oxidative stress biomarkers were measured using a SpectraMax iD3 multimodal microplate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA), following the methodologies described above.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Because a crossover experimental design was used, the data were analyzed in blocks. First, we performed a descriptive analysis of the data, followed by an assessment of the normality of the residuals and the homogeneity of variances. All data showed a normal distribution, which is why we decided to use a parametric test. Thus, the data were analyzed using the ‘MIXED’ procedure of SAS (SAS Inst. Inc., Cary, NC, USA; version 9.4), with the Satterthwaite approximation to determine the degrees of freedom of the denominator for the fixed effects tested. In the experimental model, treatment, day, and the interaction between treatment and day were used as fixed effects, while the animal was considered as having a variable effect. All data obtained on day 1 for each variable were included as covariates in each analysis, in addition to the initial weight being included as a variable in the model. The first-order autoregressive covariance structure was selected according to the lowest Akaike information criterion. The comparison of means was performed using the T-test, where significance was considered when p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Productive Performance, Intake Feed, and Feed Efficiency

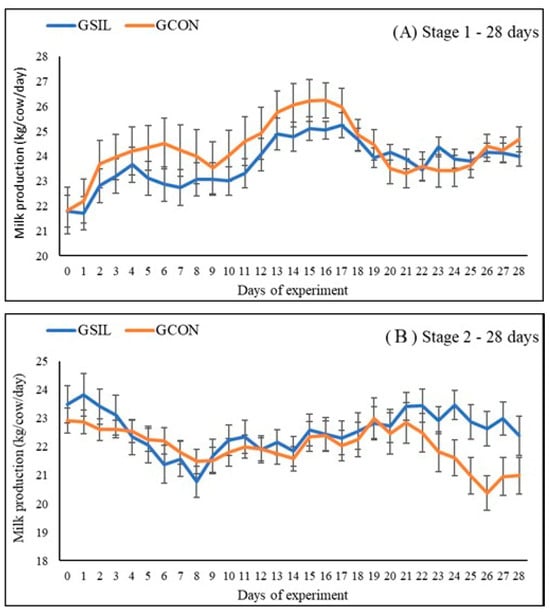

The performance results are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2. There was no difference between the groups evaluated in milk production (kg/day), dry matter intake, and feed efficiency (p > 0.05). For milk production corrected for 4% fat, we observed that the GSIL group had an increase in production (24.4 kg × 23.2 kg) when compared to the GCON group on days 15–28 of the experiment (p = 0.05).

Figure 2.

Daily milk production of dairy cows receiving a control diet (GCON) or a diet with silymarin (GSIL) during a crossover experiment ((A)—Stage 1; (B)—Stage 2). Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

3.2. Milk Quality

Table 3 presents the results of the centesimal composition of the milk and somatic cell count (SCC). We observed no effect of silymarin on the centesimal composition of the milk (protein, lactose, total solids, urea) and SCC. However, GSIL showed a higher percentage of fat in the milk (p = 0.05) compared to GCON on day 28 of the experiment.

Table 3.

Centesimal composition and somatic cell count of cows that consumed silymarin (GSIL) compared to the control (GCON).

3.3. Rumen Environment

The results for pH, short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) profile, and total short-chain fatty acids are shown in Table 4. We observed the effect of silymarin on acetic acid concentration (57.4 vs. 48.4 nmol/L) and total SCFA concentration (100.2 vs. 89.4 nmol/L), which, for both, was higher in the GSIL group compared to the GCON group (p ≤ 0.01). There was no difference in the concentration of propionic, butyric, isobutyric, isovaleric, and valeric acids in the rumen fluid.

Table 4.

pH, short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) profile, and total SCFA in the rumen fluid of cows that consumed silymarin (GSIL) compared to the control group (GCON).

3.4. Blood Tests

3.4.1. Complete Blood Count

Table 5 shows the results of the complete blood count. The leukocyte, lymphocyte, granulocyte, monocyte, erythrocyte, and platelet counts were not influenced by silymarin consumption (p > 0.05). There was also no difference between the groups in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

Table 5.

Hematological, biochemical, and immunological analyses in the serum of cows that consumed silymarin (GSIL) compared to the control (GCON).

3.4.2. Serum Biochemistry

Serum biochemistry data are presented in Table 5. There was a treatment × day interaction in cholesterol concentration on day 14, which was lower in the GSIL group compared to the GCON group. A treatment × day interaction in cholinesterase activity on day 14 was observed, being higher in the GSIL group compared to the GCON group. A treatment × day interaction on day 28 was found for both GGT and AST activity, where both were lower in the GSIL group compared to the GCON group. ALT activity was higher in the GSIL group compared to the GCON group (p < 0.05). We also observed a treatment × day interaction for ALT, which was higher in the GSIL group on days 14 and 28 of the evaluation. No difference was observed between the groups for the other biochemical markers: albumin, bilirubin, glucose, total proteins, urea, and globulins.

3.4.3. Proteinogram

The results of the proteinogram analysis are presented in Table 5. Haptoglobin concentration was 19.35% lower in the GSIL group compared to the GCON group (p = 0.05). We also observed a treatment × day interaction in haptoglobin concentration, which was lower in the GSIL group compared to the GCON group on day 28. For gamma-globulin, ceruloplasmin, ferritin, and transferrin, we found no differences between the groups (p > 0.05).

3.4.4. Oxidative Status

Table 6 presents the results for the oxidative and antioxidant variables. GST activity was lower in the GSIL group compared to the GCON group. TBARS levels were lower in the GSIL group in contrast to the GCON group, and a treatment × day interaction in TBARS levels was found on days 14 and 28, being lower at both time points for the GSIL group compared to the GCON group. Lower MPO activity was found in the GSIN group in contrast to the GCON group on day 28 (p = 0.05). A higher amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was found in the GCON group when compared to the GSIL group on day 28 (p = 0.05). No difference was found for GSH and SOD activity between the groups.

Table 6.

Biomarkers of oxidative status of cows that consumed silymarin (GSIL) compared to the control group (GCON).

4. Discussion

Application of silymarin in chicken diets has been carried out frequently for years [31], but studies on silymarin in ruminant diets have intensified in recent years; the vast majority in cows are related to the lactation period. It is scarce during lactation and absent in the final third of lactation, a time of stability for the cow, but this phase is no less challenging. No significant differences were observed in dry matter intake (DMI) and feed efficiency between the groups evaluated, which was expected, since the animals were in a more advanced stage of lactation, when increased production is difficult to achieve. Previous studies that evaluated the productive responses of cows fed silymarin were conducted during the transition period, where authors verified an increase in milk production both during the experimental period and throughout lactation [15,32]. Milk production corrected to 4% fat was higher in the GSIL group compared to the control group, due to the higher percentage of fat in the milk. This result had a direct relationship with energy production, more specifically, acetate, as discussed below.

Although no differences were found in daily milk production, a higher percentage of fat was observed in the milk of cows fed silymarin compared to the control group. Similar results were reported by Garavaglia et al. [18], who found an increase in the percentage of milk fat (3.68% × 3.55%) in cows fed 7.77 g/day of silymarin, administered for seven days before and fourteen days after calving. The mechanism by which silymarin influences milk fat production is not yet fully elucidated. However, we believe that the higher concentration of ruminal acetic acid observed in the treated group (GSIL) compared to the control (GCON)—which is a fundamental precursor for fat synthesis via de novo synthesis—may have contributed to this effect [33]. On the other hand, Hashemzadeh-Cigari et al. [34], when feeding dairy cows in the middle third of lactation with a mixture of phytobiotics, observed a tendency for a reduction in ruminal acetic acid concentration and a lower percentage of milk fat in treated animals compared to the control. In dairy cows, approximately half of the milk fat is synthesized de novo in the mammary gland, with the main substrate being acetyl-CoA, derived from acetate; therefore, the availability of acetate is essential for milk fat synthesis [33,35].

Cholesterol participates in multiple cellular processes, in addition to being an important structural component of the cell membrane and playing a key role in the synthesis of steroid hormones. Higher serum cholesterol concentrations are generally associated with greater milk production in dairy cows, particularly during the postpartum period [36]. In the present study, cows that consumed silymarin exhibited lower serum cholesterol concentrations on day 14; however, this reduction was not associated with changes in milk production. Consistent with this observation, Katica et al. [37] reported that milk production per se does not significantly influence serum cholesterol concentrations in dairy cows. A possible explanation for the lower cholesterol levels observed in cows that consumed silymarin is its beneficial effect on liver function, which may enhance hepatic lipid utilization and metabolic efficiency.

Some studies show that silymarin has a hepatoprotective effect, and this is related to its ability to stimulate cell regeneration and protein synthesis in hepatocytes [10,15]. Our study found that some markers of liver health were affected by silymarin consumption. For example, concentrations of ALT, an enzyme responsible for assisting in the metabolism of nutrients in the liver, were lower in the GSIL group compared to the GCON group. When liver cells suffer some type of damage, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) is released into the bloodstream, and according to Kataria and Kataria [38], GGT levels in healthy adult cattle are 12 to 34 U/L. Stojević et al. [39] evaluated the serum activity of the enzyme AST in dairy cows and found that the concentration of AST is higher in the first weeks of lactation, and as lactation progresses, its concentration decreases. According to Kauppinen [40], higher levels of AST activity are related to liver damage. In our study, AST activity was lower in the GSIL group compared to the GCON group on day 28 (p < 0.05), and we believe this is related to the hepatoprotective effect of silymarin, resulting in less liver damage.

Acute phase proteins, particularly haptoglobin (Hp), are indicators of systemic inflammation and often manifest before clinical signs of disease [41]. Previous studies with dairy cattle have shown a wide variation in serum Hp levels, with higher concentrations mainly in animals that experienced dystocia, postpartum metritis, retained placenta, and metabolic challenges due to elevated levels of β-hydroxybutyrate [42,43]. Fouz et al. [44] observed a correlation between parity order and serum and milk sample levels of Hp, where cows in their third or later calving have higher Hp concentrations, followed by first-calf heifers. Therefore, adding silymarin to the diet can stimulate the immune system, reducing inflammatory damage in both the liver and mammary gland, especially in cows with higher calving rates, as these are the main organs that synthesize Hp [45].

The increased production of oxidants in animal cells due to the increased production of free radicals leads animals to experience a situation called oxidative stress, as the body needs to neutralize or eliminate them [46]. Reactive oxygen species are one of the main forms of free radicals produced, and when in excess, they can bind to tissues and biological structures such as lipids, causing damage [47,48]. An in vitro study showed that silymarin can be an effective alternative in combating damage induced by oxidative stress. Kiruthiga et al. [49] incubated cells in the presence of Benzo(a)Pyrene (B(a)P), a hydrocarbon known to cause DNA damage and increase the risk of tumors. In one of the treatments, the B(a)P + cells were exposed to a solution containing 2.4 mg/mL of silymarin, and the results indicated a lower concentration of TBARS, which is related to less cell damage caused by free radicals. Our study found similar results, where we first observed that GSIL had a significantly lower presence of ROS compared to GCON, following the same pattern for TBARS, where the concentration was also significantly lower in the group fed 5 g/day of silymarin. Garavaglia et al. [18] found results that contradict ours when they evaluated TBARS levels in dairy cows fed silymarin, but did not observe significant results for ROS between the treatment and control groups in the study.

MPO is a heme enzyme produced by inflammatory cells and released by leukocytes at injury sites, thus reflecting the activation of neutrophils and lymphocytes. This enzyme catalyzes the reaction between chloride ions and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), generating large amounts of hypochlorous acid (HOCl), a reactive oxygen species (ROS) that, in turn, can originate singlet oxygen and hydroxyl radicals [28]. Therefore, MPO is an important marker of oxidative stress as it can contribute to tissue damage and chronic inflammation [50]. In a study with rats, Razavi-Azarkhiavi et al. [51] administered a cytotoxic antibiotic and evaluated MPO activity in the animals’ lung cells. A group of rats was fed silymarin at a dose of 100 mg/kg body weight, and the results showed a significant reduction (p < 0.05) in MPO activity in the group that consumed silymarin compared to the control group. In this present study, silymarin intake resulted in lower MPO, indicating lower inflammatory cell activity and consequently less tissue damage.

Our research focused on cows in the late-lactation, when milk production has already stabilized; it is important that future studies focus on cows in peak and mid-lactation, when metabolic challenges are greater, and under these conditions, silymarin could have a more significant role. The effects on the short-chain fatty acid profile were interesting and had a direct relationship with increased milk fat, but the mechanism actually involved needs to be better investigated, since this effect on VFA may be related to the rumen microbiota. It is known that in ruminants, the effects of silymarin on the microbiota are still poorly explored and are mostly inferred from changes in rumen fermentation patterns and metabolic responses, rather than direct microbiome analyses. In 2023, researchers evaluated a component of silymarin, silibinin, and found that it was able to reduce in vitro methane production by regulating the rumen microbiome and metabolites [52]. In this in vitro study, the authors observed a linear increase in pH when silibinin was added at concentrations of 0.15 g/L to 0.60 g/L, but under these conditions there was a decrease in the total concentration of volatile fatty acids, a reduction in the molar proportion of acetic acid, an increase in the molar proportion of propionic acid, and a reduction in dry matter digestibility; in addition, the relative abundance of Prevotella, Isotricha, Ophryoscolex, Rotifera, Methanosphaera, Orpinomyces, and Neocallimastix in the rumen decreased after the addition of 0.60 g/L of silibinin; while there was an increase in the relative abundance of Succiniclasticum, NK4A214 group, Candidatus, Saccharimonas, and Lachnospiraceae [52]. Therefore, under controlled conditions, it is known that silymarin can influence the microbiome; this also needs to be investigated in vivo in the future.

5. Conclusions

The ingestion of 5 g/day of silymarin by dairy cows did not affect dry matter intake or feed efficiency in late lactation. However, silymarin supplementation was associated with an increase in milk fat percentage, resulting in 4% fat-corrected milk yield, which may be related to changes in energy utilization and ruminal acetate availability. The observed reduction in serum AST activity and the increase in ALT values within the physiological range suggest a potential modulation of hepatic metabolism without indications of liver dysfunction. In addition, lower concentrations of ROS, TBARS, and MPO indicate an improvement in oxidative status and a possible anti-inflammatory effect. Collectively, these findings suggest that dietary silymarin may support hepatic metabolic function and antioxidant balance in late-lactation dairy cows; however, the biological significance of these responses should be interpreted with caution, particularly in the absence of an imposed metabolic or immune challenge.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation11120701/s1, Figure S1: Representative image of the silymarin powder used as dietary feed in the experimental treatments.

Author Contributions

P.V.N. and A.S.d.S. contributed to the design and implementation of the research, and to the analysis of the results. M.D.B. helped in the elaboration of the project, in its execution, and with its financing. P.V.N., L.N., G.L.D., G.B.d.S., and D.M. participated in the execution of the experiment and collection of samples and data, as well as laboratory analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The project was approved by the animal research committee of the State University of Santa Catarina, following the current CONCEA/Brazil regulations (approval protocol number 7502161224; approved on 20 December 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are with the authors and may only be made available upon request with justification, since this is original research, and our research group continues to explore the topic in new experiments.

Acknowledgments

We thank UDESC, UFFS, FAPESC, CAPES, and CNPq for their technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hashemi, S.R.; Davoodi, H. Herbal plants and their derivatives as growth and health promoters in animal nutrition. Vet. Res. Commun. 2011, 35, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaei, R.; Seidavi, A.; Bouyeh, M. A review on the mechanisms of the effect of silymarin in milk thistle (Silybum marianum) on some laboratory animals. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesan, K.; Jayachandran, M.; Xu, B. A critical review on hepatoprotective effects of bioactive food components. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 1165–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abenavoli, L.; Milic, N.; Capasso, R.; Tran, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Izzo, A.A.; Borrelli, F. Milk thistle (Silybum marianum): A concise overview on its chemistry, pharmacological, and nutraceutical uses in liver diseases. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 2202–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milić, N.; Milošević, N.; Suvajdžić, L.; Žarkov, M.; Abenavoli, L. New therapeutic potentials of milk thistle (Silybum marianum). Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8, 1957–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grela, R.E.; Pietrzak, P.; Okruszek, A.; Ender, K.; Wróblewski, R. Impact of milk thistle (Silybum marianum L.) seeds in fattener diets on pig performance and carcass traits and fatty acid profile and cholesterol of meat, backfat and liver. Livest. Sci. 2020, 239, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendowski, W.; Kowalczyk, J.; Michalczuk, M.; Kubiak, D. Using milk thistle (Silybum marianum) extract to improve the welfare, growth performance and meat quality of broiler chicken. Animals 2022, 12, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muriel, P.; Mourelle, M. Prevention by silymarin of membrane alterations in acute CCl4 liver damage. J. Appl. Toxicol. 1990, 10, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, L.; Silva, M.; Manso, C.F. Scavenging properties of reactive oxygen species by silibinin dihemisuccinate. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994, 48, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morazzoni, P.; Bombardelli, E. Silybum marianum (Carduus marianus). Fitoterapia 1995, 66, 3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.S.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Lee, J.S.; Choi, E.Y.; Kim, W.K.; Lee, S.C. Silymarin inhibits TNF-alpha-induced expression of adhesion molecules in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 2003, 550, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharagozloo, M.; Shapouri-Moghaddam, A.; Yousefi, M.; Hajizadeh, S.; Hassan, Z.M.; Nikoueinejad, H.; Seidavi, A.; Baghban-Kohnehrouz, B.; Sadeghi-Nasab, P. Immunosuppressive effect of silymarin on mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathway: The impact on T cell proliferation and cytokine production. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 113, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drackley, J.K. Biology of dairy cows during the transition period: The final frontier? J. Dairy Sci. 1999, 82, 2259–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedesco, D.E.A.; Guerrini, A. Use of milk thistle in farm and companion animals: A review. Planta Med. 2023, 89, 584–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedesco, D.; Tava, A.; Galletti, S.; Tameni, M.; Varisco, G.; Costa, A.; Steidler, S. Effects of silymarin, a natural hepatoprotector, in periparturient dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 2239–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasem. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle, 8th ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle: Seventh Revised Edition, 2001; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Garavaglia, L.; Galletti, S.; Tedesco, D. Silymarin and lycopene administration in periparturient dairy cows: Effects on milk production and oxidative status. N. Z. Vet. J. 2015, 63, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.J.; Queiroz, A.C. Análises de Alimentos: Métodos Químicos e Biológicos, 3rd ed.; UFV: Viçosa, Brasil, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Wine, R.H. Determination of lignin and cellulose in acid detergent fiber with permanganate. J. Assoc. Off. Agric. Chem. 1968, 51, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9622/IDF Standard 141; Milk and Liquid Milk Products—Guidelines for the Application of Midinfrared Spectrometry. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- ISO 13366-2/IDF Standard 148-2; Milk—Enumeration of Somatic Cells—Part 2: Guidance on the Operation of Fluoro-Opto-Electronic Counters. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Simon, A.L.; Olivo, R.; García, R.; López, S.; Fernández, S.; Martínez, J.A.; Torres, P.; Gómez, M.J. Inclusion of exogenous enzymes in feedlot cattle diets: Impacts on physiology, rumen fermentation, digestibility and fatty acid profile in rumen and meat. Biotechnol. Rep. 2024, 41, e00824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagliari, J.J.; Embrapa, L.F.; Silva, L.M.; Souza, L.P.; Santos, B.F.; Oliveira, J.A.; Costa, J.H.; Pereira, M.J.; Cardoso, V.C.; Rocha, R.A.; et al. Constituintes sanguíneos de bovinos recém-nascidos das raças Nelore (Bos indicus) e Holandesa (Bos taurus) e de bubalinos (Bubalus bubalis) da raça Murrah. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 1998, 50, 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasi, T.; Minuti, A.; Malacarne, M.; Stefanon, B.; Badon, T.; Contiero, B.; Vitali, A.; Pilla, R.; Dell’Orto, V.; Prandini, A.; et al. Metaphylactic effect of minerals on the immune response, biochemical variables and antioxidant status of newborn calves. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2018, 102, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.F.; Lebel, C.P.; Bondy, S.C. Reactive oxygen species formation as a biomarker of methylmercury and trimethyltin neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology 1992, 13, 637–648. [Google Scholar]

- Jentzsch, A.M.; Bachmann, H.; Fürst, P.; Biesalski, H.K. Improved analysis of malondialdehyde in human body fluids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 20, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, K.; Ota, H.; Sasagawa, S.; Sakatani, T.; Fujikura, T. Assay method for myeloperoxidase in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Anal. Biochem. 1983, 132, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, J.M.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: An enzymatic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J. Biol. Chem. 1969, 244, 6049–6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habig, W.H.; Pabst, M.J.; Jakoby, W.B. Glutathione S-transferases: The first enzymatic step in mercapturic acid formation. J. Biol. Chem. 1974, 249, 7130–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.A.; Kirrella, A.A.K.; Dawood, M.A.O.; Ebeid, T.A. Effect of dietary inclusion of milk thistle (Silybum marianum) and its bioactive compounds on growth performance, antioxidant status and immune response in poultry: A review. Animals 2022, 12, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulger, I.; Onmaz, A.C.; Ayaşan, T. Effects of silymarin (Silybum marianum) supplementation on milk and blood parameters of dairy cattle. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 47, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, N.L.; Harvatine, K.J. Acetate dose-dependently stimulates milk fat synthesis in lactating dairy cows. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemzadeh-Cigari, F.; Ghaffari, M.H.; Sharifi, G.; Haghparast, S.; Seidavi, A.; Chekani-Aliakbar, S.; Laudadio, V.; Tufarelli, V. Effects of supplementation with a phytobiotics-rich herbal mixture on performance, udder health, and metabolic status of Holstein cows with various levels of milk somatic cell counts. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 7487–7497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauman, D.E.; Griinari, J.M. Nutritional regulation of milk fat synthesis. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2003, 23, 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilenko, T.F. Factors determining the elevated blood cholesterol level in dairy cows during the first months of postpartum. Probl. Biol. Prod. Anim. 2020, 2, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Katica, M.; Mukaca, A.; Saljic, E.; Caklovica, K. Daily milk production in cows: The effect on the concentration level of total cholesterol in blood serum. J. Dairy Vet. Sci. 2019, 12, 555841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataria, N.; Kataria, A.K. Use of serum gamma glutamyl transferase as a biomarker of stress and metabolic dysfunctions in Rathi cattle of arid tract in India. J. Stress Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 8, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stolević, Z.; Tomić, Z.; Marković, J.; Djurdjević, B.; Katić, M.; Milovanović, S.; Jovanović, M. Activities of AST, ALT and GGT in clinically healthy dairy cows during lactation and in the dry period. Vet. Arh. 2005, 75, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen, K. ALAT, AP, ASAT, GGT, OCT activities and urea and total bilirubin concentrations in plasma of normal and ketotic dairy cows. Zentralbl. Veterinarmed. A 1984, 31, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.E. Acute phase proteins: Their use in veterinary diagnosis. Br. Vet. J. 1992, 148, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huzzey, J.M.; Veira, D.M.; Weary, D.M.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Associations of peripartum markers of stress and inflammation with milk yield and reproductive performance in Holstein dairy cows. Prev. Vet. Med. 2015, 120, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, A.; Burfeind, O.; Heuwieser, W. The associations between postpartum serum haptoglobin concentration and metabolic status, calving difficulties, retained fetal membranes, and metritis. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 4555–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouz, R.; Molina, E.; Goyache, F.; López, S.; García-Ispierto, I. Evaluation of haptoglobin concentration in clinically healthy dairy cows: Correlation between serum and milk levels. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2024, 52, 2300624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiss, S.; Mielenz, M.; Bruckmaier, R.M.; Sauerwein, H. Haptoglobin concentrations in blood and milk after endotoxin challenge and quantification of mammary Hp mRNA expression. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 3778–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tufarelli, V.; Laudadio, V.; Ceci, E.; Selvaggi, M.; Dario, C.; Vicenti, A. Biological health markers associated with oxidative stress in dairy cows during the lactation period. Metabolites 2023, 13, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indo, H.P.; Davidson, M.; Yen, H.C.; Suenaga, S.; Tomita, K.; Nishii, T.; Higuchi, M.; Koga, Y.; Ozawa, T.; Majima, H.J. Evidence of ROS generation by mitochondria in cells with impaired electron transport chain and mitochondrial DNA damage. Mitochondrion 2007, 7, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadinejad, F.; Geir Møller, S.; Hashemzadeh-Chaleshtori, M.; Bidkhori, G.; Jami, M.S. Molecular mechanisms behind free radical scavengers function against oxidative stress. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiruthiga, P.V.; Sridevi, P.; Devi, K.; Vijayalakshmi, K.; Sivasubramanian, S.; Saravanan, R. Silymarin protects PBMC against B(a)P-induced toxicity by replenishing redox status and modulating glutathione metabolizing enzymes—An in vitro study. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2010, 247, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phaniendra, A.; Jestadi, D.B.; Periyasamy, L. Free radicals: Properties, sources, targets, and their implications in various diseases. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 30, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razavi-Azarkhiavi, K.; Hosseini, H.; Rafati, A.; Ghanbarzadeh, S.; Shokrzadeh, M.; Ahmadi, A. Silymarin alleviates bleomycin-induced pulmonary toxicity and lipid peroxidation in mice. Pharm. Biol. 2014, 52, 1267–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Shen, Y.; Ma, H.; Li, Y.; Lambo, M.T.; Dai, B.; Shen, W.; Qu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Silibinin reduces in vitro methane production by regulating the rumen microbiome and metabolites. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1225643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).