Abstract

High organic loading is known to destabilize anaerobic digestion (AD). This study compared bioaugmentation and pH adjustment under increasing organic loading rate (OLR: 2.0, 4.0 and 6.0 gVS L−1 d−1), focusing on the responses of microbial structure, metabolic pathways, and energy metabolism. Results demonstrated that bioaugmentation maintained stable methane production of 400.54 ± 10.08 and 374.15 ± 24.32 mL·g-VS−1 at 4.0 and 6.0 gVS L−1 d−1, respectively, whereas control and pH-adjusted reactors failed at 4.0 gVS L−1 d−1. The acidified system restored methane yield from 86.30 to 382.13 mL·g-VS−1 after bioaugmentation, whereas pH adjustment and feeding cessation were ineffective, failing to produce methane within 25 days. Microbial analysis showed bioaugmentation enriched Methanosarcina, enhanced hydrogenotrophic/methylotrophic methanogenesis, and strengthened syntrophy with syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria (SPOB), reducing volatile fatty acid accumulation via reinforced syntrophic propionate/butyrate oxidation. Upregulation of osmoregulatory (nha, kdp, proP) and energy metabolism genes (eha, mvh, hdr) maintained osmotic balance and energy supply under high load. In contrast, pH adjustment downregulated SPOB and propionate oxidation genes, causing persistent acid inhibition. This study elucidated the distinct regulatory effects of bioaugmentation and pH adjustment on high-load AD systems, providing actionable strategies for both maintaining operational stability in high-load reactors and recovering methanogenesis in acid-inhibited systems.

1. Introduction

China generates over 125 million tons of food waste (FW) annually, and anaerobic digestion (AD) offers a mainstream approach for converting it into valuable resources such as methane and other high-value products [1]. Despite the relative maturity of AD technology, its application to FW management still faces challenges, particularly the need to operate at low organic loading rates (OLR) in practice. Due to the highly biodegradable characteristic of FW, increasing the OLR often triggers acidification and a sharp decline in methane production [2,3]. Previous studies indicate that FW digestion systems experience acid inhibition at OLR of 2.0–6.0 gVS L−1 d−1, leading to significant accumulation of volatile fatty acid (VFA) [4,5,6].

Various strategies have been explored to mitigate acid inhibition, including the addition of exogenous substances (e.g., electroactive materials, acid/alkaline substance, trace elements), adoption of co-digestion, operational parameter adjustments (e.g., pH, hydraulic retention time (HRT), temperature), and reactor optimization [5,7,8,9]. While these approaches have shown effectiveness, they are often limited by complex operational requirements, high costs, and potential long-term chemical accumulation. Bioaugmentation, the external introduction of specific functional microorganisms, represents a promising alternative with demonstrated potential in alleviating acid inhibition, alongside advantages in operational flexibility, environmental compatibility, and cost efficiency [10,11].

Researchers have employed acid-resistant cultures to enhance acetate decomposition and methane yield [5,12], as well as methanogenic propionate-enriched cultures to improve propionate degradation and alleviate acid inhibition [13,14]. Such VFA-degrading enrichments could lower VFA concentrations and shorten system recovery time [15]. However, the OLR in these studies has remained relatively low, typically ranging from 0.625 to 2 gVS L−1 d−1. There is a necessary need to develop bioaugmentation strategies capable of stable operation under higher OLR to balance process stability with maximal digestion efficiency. It is worth noting that microbial responses vary with different bioaugmentation consortia, closely depending on the composition of the inoculated culture. Therefore, elucidating the microbial response of bioaugmentation to alleviate acid inhibition caused by elevated OLR can help better understand and apply this technology.

Given the widespread use in full-scale reactors for mitigating VFA disturbance [16], pH adjustment was chosen as a representative conventional strategy to benchmark the performance of bioaugmentation. This study aims to: (1) compare the effectiveness of bioaugmentation with conventional pH adjustment in enhancing AD performance under high organic loading; (2) evaluate the recovery efficiency of methane production and VFA metabolism following bioaugmentation or pH adjustment in acid-inhibited conditions; and (3) reveal how bioaugmentation and pH adjustment influence metabolic pathways, including methanogenesis, VFA metabolism, osmoregulation, and energy metabolism in acid-inhibited AD systems. These insights demonstrate the technical feasibility of using bioaugmentation to high organic loading in mesophilic AD of FW.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Preparation

The initial inoculum was obtained from a mesophilic anaerobic digester treating FW (Grandblue Environment Co., Ltd., Harbin, China). Sand particles and large solids were removed by sieving through a 1 mm mesh. The inoculum was stored at room temperature for seven days to consume residual biodegradable substrates. FW was collected from a canteen at Harbin Institute of Technology. It was first screened to remove recalcitrant materials (e.g., bones, tissues), homogenized, and then stored at −20 °C. Prior to use, the FW was thawed to room temperature. Characteristics of the inoculum and substrate were provided in Table S1. The bioaugmentation culture was derived from a laboratory-scale, acid-resistant anaerobic reactor with long-term stable operation. The dominant functional microorganisms in the bioaugmentation consortia were listed in Table S2.

2.2. Experimental Procedures

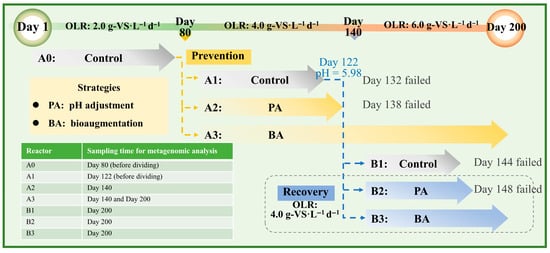

The 200-day experiment induced system acidification by progressively increasing the OLR, comparing the ability of bioaugmentation (BA) and pH adjustment (PA) to maintain and recover methanogenic performance in anaerobic systems, as outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental design and main operating conditions.

All Laboratory-scale semi-continuous stirred tank reactors were operated at 37 °C with agitation at 120 rpm. The initial reactor A0, with a working volume of 1.8 L, was operated at an OLR of 2.0 gVS L−1 d−1 for two hydraulic retention times (HRTs, 40 days each). To ensure identical initial conditions for comparing acidification prevention strategies, on the day 80, the digestate from A0 was evenly distributed into three reactors (A1, A2, A3), with a working volume of 600 mL per reactor. A1 served as the control without any treatment; A2 was adjusted to pH 7.20 ± 0.02 using sodium hydroxide (reagent grade, ≥98% purity, pellets, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, Missouri, USA) during operation to avoid affecting the volume of reactor; A3 was inoculated with 30 mL of mixed bioaugmentation culture, a dosage corresponding to 1% (VS/VS) of the inoculated sludge at the start of operation, while an equal volume of distilled water was added to A1 and A2 to maintain consistent working volumes. After operating stably at 4.0 gVS L−1 d−1 for three HRTs (20 days each), the OLR in A3 was increased to 6.0 gVS L−1 d−1 on day 140 and maintained for four additional HRTs (15 days each) to assess its adaptability and long-term efficacy under higher loading.

When the pH in A1 dropped below 6.0 with a sharp decline in methane production, A1 digestate was divided equally into three reactors B1, B2, and B3 with working volume of 180 mL per reactor to evaluate the recovery potential of each strategy in the acidified system. B1 was operated without feeding to assess natural recovery; B2 received the same pH adjustment as A2; B3 was supplemented with 15 mL of bioaugmentation consortium, a dosage corresponding to 1.5% (VS/VS) of the inoculated sludge at the start, while the other two received 15 mL of distilled water. All experiments were conducted in triplicate and periodic sampling was performed for physicochemical and metagenomic analyses.

2.3. Analytical Methods

The soluble chemical oxygen demand (sCOD), total ammonia nitrogen (TAN), total alkalinity (TA) and total/volatile solids (TS/VS) were measured using potassium dichromate spectrophotometry, Nessler’s reagent spectrophotometry, titration, and the standard gravimetric method, respectively [17,18]. Free ammonia nitrogen (FAN) and VS removal were calculated according to previous study [19]. The pH was measured using a pH meter (INESA, PHS-3C, Shanghai, China). VFA concentrations were analyzed by gas chromatography (Agilent 8890, Santa Clara, CA, USA) after sample filtration (0.22 µm) and acidification. Separation was achieved on an HP19095N-123I column with flame ionization detector (detector/injector/oven: 240/170/240 °C), using nitrogen carrier gas (25 mL min−1). Biogas volume was measured with aluminum foil bags and reported at standard ambient temperature and pressure (SATP, 298.15 K and 100 kPa). Methane content was analyzed by GC (Agilent 7890, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a thermal conductivity detector and the nickel catalyst (300 °C). A PoraPakQ column was used under the following conditions: injector/detector temperatures at 300/200 °C; hydrogen flow at 60 mL min−1; air at 300 mL min−1; reference gas at 20 mL min−1; makeup gas at 5 mL min−1.

2.4. Metagenomic Analysis

Samples collected from parallel reactors were thoroughly mixed, centrifuged, and stored at −80 °C prior to DNA extraction and metagenomic analysis. Sampling time points and corresponding sample identifiers are summarized in Figure 1. Total genomic DNA was extracted using the Mag-Bind® Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek, Norcross, GA, USA) and fragmented to about 400 bp using a Covaris M220 instrument (Gene Company Limited, Shanghai, China) for paired-end library preparation. Metagenomic sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq platform at Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). A non-redundant gene catalog was constructed with CD-HIT (v4.6.1), and gene abundance was quantified by aligning high-quality reads to this catalog at 95% identity using SOAPaligner (v2.21). Functional annotation was carried out by aligning representative sequences to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of replicate experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 26.0. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, with a p value < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Data visualization and graphical representation of the results were carried out using OriginPro 2021 and R 4.4.1.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Reactor Performance

3.1.1. Methane Production

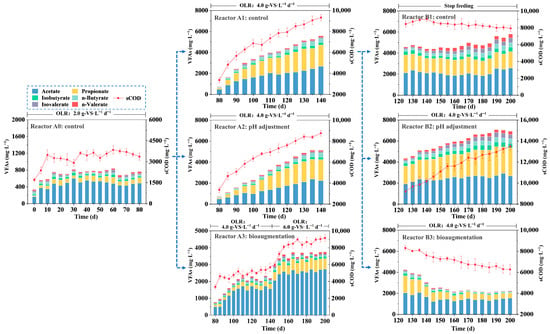

Methane yield refers to the volume of methane produced per unit of substrate, whereas methane content denotes the percentage of methane in the biogas. Both parameters were used to assess the operational status of the AD systems. The results demonstrated that the bioaugmentation strategy significantly enhanced both methane production and content, thereby alleviating acid inhibition induced by elevated OLR. In contrast, the pH adjustment strategy only delayed reactor failure and failed to resolve the underlying acid inhibition (Figure 2). Prior to the separation of bottle A0, methane yield reached 456.89 ± 13.23 mL·g-VS−1. This value aligned with the typical reported range for FW (321–547 mL CH4·g-VS−1) under mesophilic conditions, indicating expected system performance [20]. On the fourth day after increasing the OLR to 4.0 g-VS·L−1·d−1, methane production in reactors A1, A2, and A3 dropped sharply to 356.24 ± 35.12, 370.57 ± 21.06, and 364.65 ± 25.35 mL·g-VS−1, respectively, indicating the adverse impact of higher organic loading. However, the bioaugmented reactor A3 exhibited a gradual recovery in methane production, reaching 406.91 ± 16.05 mL·g-VS−1 with a methane content of 56.76% by day 140 (Figure 2 and Figure S1). In comparison, A1 and A2 ceased gas production on days 132 and 140, respectively. Consistent with prior reports that easily fermentable substrates often require lower organic loading [21], both the control (A1) and pH-adjusted (A2) reactors failed to sustain operation at an OLR of 4.0 gVS L−1 d−1. When the OLR in the bioaugmented reactor A3 was further increased to 6.0 gVS L−1 d−1, methane production initially declined to 321.50 ± 32.41 mL·g-VS−1 but progressively recovered, attaining 374.15 ± 24.32 mL·g-VS−1 by day 200. These results confirm that the bioaugmentation strategy effectively prevents reactor collapse under high organic loading and significantly improves system stability and load tolerance.

Figure 2.

Methane yield and pH throughout the experimental period.

The bioaugmentation approach also exhibited excellent recovery performance in already acidified AD systems. Over two HRTs, methane yield of B3 increased from an initial 56.30 ± 21.02 mL·g-VS−1 to 350.67 ± 20.25 mL·g-VS−1, and the methane content also showed a similar trend, rising from 30.14% to 50.37% (Figure S1), aligning with typical AD values (50–70%) and confirming successful process restoration [22]. pH adjustment and self-recovery strategies led to complete failure within 25 days, B1 (feeding halted) and B2 (pH adjusted) stopped producing gas on days 144 and 148, respectively. Consistent with previous study, Zhang et al. reported that pH adjustment strategies were unable to reverse the fundamental imbalance during AD processes and can only delay eventual process failure [23]. This study employed a reduced HRT of 20 days to achieve the elevated OLR of 4.0 gVS L−1 d−1. The shorter HRT inherently increases the risk of washing out slow-growing microorganisms like methanogens, thereby impairing methane production [24,25]. In this context, pH adjustment can be interpreted as a symptomatic intervention attempting to stabilize the system against this imbalance. However, as results demonstrate, it failed to fundamentally enhance methane yield under the constrained HRT. This indicates that for long-term stability under high organic load (short HRT) conditions, reinforcing the functional capacity of the microbial community may be more critical than merely modulating the chemical environment.

3.1.2. VFA and Other Physicochemical Parameters

Raising the organic loading often leads to VFA accumulation and pH decline [26]. VFA exert inhibitory effects on functional microorganisms, with propionate and butyrate previously considered equally inhibitory [23]. However, during long-term FW digestion, propionate emerges as the primary inhibitory VFA [16], capable of inhibiting methanogens at concentrations exceeding 1000 mg·L−1 [27]. The results showed that bioaugmentation effectively alleviates acid inhibition and restores VFA metabolic activity even in already acidified systems (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Variations in sCOD and VFAs concentrations during the AD process.

During the operation of A0, acetate was the dominant VFA, with total volatile fatty acids (TVFA) below 1000 mg·L−1, indicating stable performance. At the OLR of 4.0 gVS L−1 d−1, all VFA components in the bioaugmented A3 remained significantly lower than in control A1 and pH-adjusted A2. Propionate in A1 and A2 exceeded the inhibition threshold by day 100 (1206.55 mg·L−1) and day 105 (1090.68 mg·L−1), respectively, and further increased to 2028.82 mg·L−1 and 1986.36 mg·L−1 by day 140. Butyrate in these reactors reached 611.18 mg·L−1 and 639.95 mg·L−1 on the same day. In contrast, A3 maintained stable propionate and butyrate levels at 292.31 ± 18.18 mg·L−1 and 189.28 ± 13.61 mg·L−1. Even when OLR was raised to 6.0 gVS L−1 d−1, these values remained well below inhibitory thresholds, at 675.15 ± 39.49 mg·L−1 and 199.32 ± 4.69 mg·L−1, respectively. Studies of successfully bioaugmented anaerobic systems reported a characteristic profile of low propionate and dominant acetate levels, which favors methanogenic activity [28]. Bioaugmented reactors A3 and B3 also exhibited lower sCOD, higher pH, improved VS removal (Figure 3 and Figure S1). The utilization of soluble organics, and higher methane conversion efficiency were enhanced following bioaugmentation.

Bioaugmentation also significantly promoted VFA metabolism in acidified systems, particularly for propionate. Within two HRTs (40 days), propionate in B3 decreased by 68.72% to 536.66 mg·L−1, butyrate fell by 43.8% to 249.99 mg·L−1, and pH increased from 5.98 to 6.46. The recovery effect was sustained: by day 200, B3 achieved a pH of 7.03, with propionate, butyrate, and TVFA concentrations declining to 473.11, 108.43, and 2253.89 mg·L−1, respectively, alongside increasing VS removal (Figure 3 and Figure S1). Reactor B1, which only ceased feeding, failed to resume gas production. Continued acidification increased the concentrations of longer-chain VFA (e.g., butyrate and valerate). This shift likely occurred because methanogenesis inhibition prevented timely consumption of acetate and hydrogen [29]. The resulting high hydrogen partial pressure and low pH created a thermodynamic constraint that hindered the syntrophic oxidation of propionate, butyrate, and valerate, leading to their accumulation [30,31,32]. Although the optimal pH range for methanogens is 6.8–7.8 [33], and pH adjustment can temporarily mitigate VFA-driven acidification, this strategy cannot reverse the underlying propionate accumulation or methanogen inhibition [34], ultimately leading to failure in A2 and B2.

Beyond VFA and pH, the stability of anaerobic systems can also be assessed by TA and the TVFA/TA [35]. As shown in Figure 4, A1 exhibited a significant decline in TA due to VFA accumulation when the OLR was increased to 4.0 gVS L−1 d−1, indicating a deterioration of its buffering capacity [36]. This result corresponds with a concurrent sharp decrease in pH (Figure 2). Reactor A2, which received sodium hydroxide supplementation, maintained the highest TA. However, its TVFA/TA reached 0.42 by day 105, exceeding the stability threshold of 0.4 suggested in previous study [19], and methane production ceased completely when the ratio further increased to 0.70. In contrast, A3, despite receiving no external alkalinity, showed a steady increase in TA and a stable TVFA/TA around 0.33, attributable to the timely VFA consumption (Figure 3). Notably, when the OLR for A3 was further elevated to 6.0 gVS L−1 d−1, its TVFA/TA ratio increased and stabilized at approximately 0.49 while maintaining continuous methane production. Long-term operation at this high load may necessitate close monitoring of reactor parameters, with potential supplementary bioaugmentation culture if required [37].

Figure 4.

Variations in TA and TVFA/TA during the AD process.

At the time of splitting, the TVFA/TA in A1 had reached 0.84, confirming severe acid inhibition and system instability. As the accumulated VFAs were gradually metabolized, the alkalinity recovered. Following bioaugmentation, TVFA/TA dropped below the 0.4 threshold by day 40 and stabilized around 0.37. This demonstrated that the bioaugmentation strategy enhanced the buffering capacity of system. Although the pH-adjustment strategy raises system alkalinity, reactor stability is ultimately determined by the timely and effective VFA metabolism.

TAN increased gradually during operation, with no marked differences under identical conditions (Figure S1). In B1, TAN initially rose due to hydrolysis of residual substrate, then declined, possibly due to microbial assimilation [38]. FAN levels are influenced by TAN, pH, and temperature [19]. The sharp FAN decreases in A1 (day 84) and A3 (days 84 and 144) coincided with pH drops following OLR increases. Reactors A2 and B2, receiving pH adjustment, showed the highest FAN levels. Since FAN inhibition has been reported between 53 and 1450 mg·L−1 [39], pH adjustment strategies require careful monitoring to avoid ammonia toxicity. In summary, bioaugmentation effectively prevented and alleviated VFA accumulation under high OLR, while enhancing VFA utilization and metabolism.

3.2. Microbial Community Analysis

3.2.1. Alpha Diversity of Microbial Community

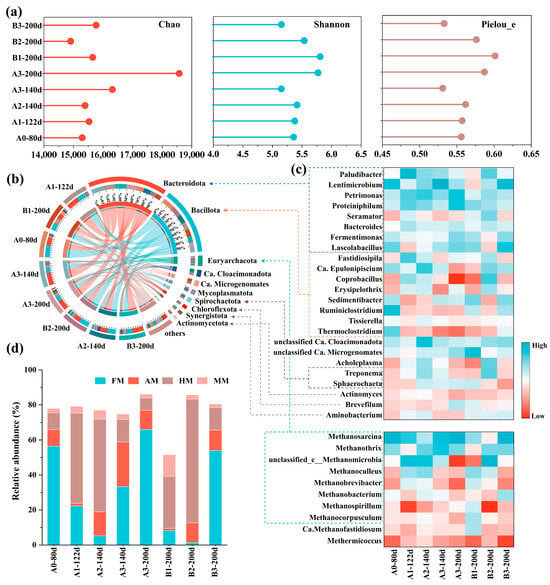

The alpha diversity indices revealed that AD systems under higher organic loading rates generally exhibited increased microbial richness, diversity, and evenness, as evidenced by higher Chao, Shannon, and Pielou_e indices in A1-122d compared to A0-80d and A3-200d relative to A3-140d (Figure 5a). Following pH adjustment, a reduction in the Chao index accompanied by rises in Shannon and Pielou_e indices indicated decreased microbial richness but enhanced community diversity and evenness. In contrast, bioaugmentation led to an increase in microbial richness but a decline in both diversity and evenness. This shift may result from competitive interactions between the introduced bioaugmentation consortia and indigenous microorganisms, leading to the colonization and displacement of certain low-activity taxa within the system [40].

Figure 5.

(a) Alpha diversity index of each sample. (b) Circos sample-to-species relationship map of reactors on phylum level. (c) Heatmap of the top bacterial and archaeal abundance on genus level. (d) Relative abundance of acetoclastic methanogen (AM), hydrogenotrophic methanogen (HM), methylotrophic methanogen (MM), and facultative methanogen (FM).

3.2.2. Effect of Bioaugmentation and pH Adjustment on Bacterial Community Structure

To elucidate the microbial mechanisms underlying the successful mitigation of acid inhibition via bioaugmentation under elevated organic loading, the microbial community structure in each reactor was analyzed (Figure 5). Throughout the experiment, Bacteroidota and Bacillota persisted as the dominant phyla across all reactors. Bacillota (formerly Firmicutes), key consumers of simple organic matter in anaerobic systems [25], exhibited the highest relative abundance in A0 at 51.99%. As OLR increased, Bacillota abundance declined in all reactors, particularly among lignocellulose-degrading genera such as Ruminiclostridium and Thermoclostridium, likely due to their sensitivity to high organic loading or low pH [41,42]. In pH-adjusted reactors A2 and B2, Bacillota remained more dominant than Bacteroidota. Additionally, these reactors showed markedly elevated abundances of Ca. Cloacimonadota, Mycoplasmatota, and Spirochaetota, suggesting enhanced activity under the maintained pH of 7.2 ± 0.02.

Bacteroidota, known for hydrolyzing refractory organics [43], were notably more abundant in the bioaugmented A3 and B3 than in controls A1 and B1 (Figure 5b). Significant enrichment was observed in Lentimicrobium (22.22- and 54.57-fold higher than controls) and Lascolabacillus (8.55- and 2.61-fold higher than controls). Similarly, pH-adjusted reactors A2 and B2 also exhibited enrichment of Lentimicrobium, albeit to a lesser extent, showing 3.48-fold and 6.31-fold increases, respectively, compared to the control. The enhancement was significantly weaker than that achieved through bioaugmentation, further highlighting the superior efficacy of bioaugmentation in modulating functional microbial communities.

When OLR was further increased to 6.0 gVS L−1 d−1, several Bacteroidota genera Petrimonas, Proteinophilum, Fermentinomas, and Lascolabacillus were enhanced in A3-200d, with relative abundances 6.86%, 8.31%, 2.78%, and 2.34% higher than in A3-140d, respectively (Figure 5c). These taxa were recognized as key players in converting complex substrates into metabolic intermediates, exhibiting strong hydrolytic capabilities toward polysaccharides and proteins [44,45,46,47]. Furthermore, methanogenesis-related phyla such as Ca. Microgenomata and Chloroflexita were significantly enriched at the highest OLR, showing 2.33-fold and 4.56-fold increases over A3-140d, respectively, indicating a potential role in stabilizing methane production [48,49]. Bioaugmentation thus sustained hydrolytic and acidogenic functions under high substrate loading, establishing a foundation for enhanced methane yield. Notably, the increased abundances of Ca. Cloacimonadota and Mycoplasmatota may also contribute to the functional recovery of acidified reactors.

Certain low-abundance but functionally critical microorganisms, such as syntrophic volatile acid-oxidizing bacteria, also play essential roles in AD system. Their metabolic activities and contributions to VFA metabolism will be further discussed in the following text of metabolic analysis.

3.2.3. Effect of Bioaugmentation and pH Adjustment on Archaeal Community Structure

The succession of methanogenic archaea during reactor operation is closely linked to methane production performance, with most dominant methanogens across samples belonging to the phylum Euryarchaeota (Figure 5b,c). Methanosarcina was the predominant genus in reactors A0, A3, and B3, which exhibited stable methane production, with relative abundances ranging from 33.28% to 66.04%, followed by the acetoclastic methanogen (AM) Methanothrix (9.49–25.60%) (Figure 5d). Methanosarcina is a facultative methanogen (FM) capable of producing methane via hydrogenotrophic, acetoclastic, and methylotrophic pathways [50]. Under an OLR of 4.0 gVS L−1 d−1, both Methanosarcina and Methanothrix were significantly enriched in A3 compared to the control A1 and pH-adjusted A2. In the acid-inhibited recovery system, enhanced methane output was primarily attributed to the increased abundance of Methanosarcina. The competitive advantage of Methanosarcina under stress may stem from its relatively faster growth rate and resilience to the pH fluctuations associated with organic overload [51]. When the OLR in A3 was raised to 6.0 gVS L−1 d−1, the relative abundance of Methanosarcina further increased from 33.28% to 66.04%, while acetoclastic and hydrogenotrophic methanogens (HM) decreased by 14.77% and 5.88%, respectively. The decline in AM may be attributed to their slower growth rate and increased washout risk at shorter HRTs [52]. In contrast, Li et al. reported the enrichment of Methanothrix and the HM Methanolinea to alleviate acid inhibition at a lower OLR of 2.0 gVS L−1 d−1 [5], suggesting that the specific functional microorganisms enhanced through bioaugmentation depend on the dominant genus in both the inoculum and the exogenous bioaugmentation consortia.

In reactors A2, B1, and B2, where methanogenesis was completely inhibited, HM dominated, with FM accounting for only 1.36–8.28% (Figure 5d). Moreover, during OLR elevation in the control group A1, FM and AM were progressively replaced by HM, primarily unclassified Methanomicrobia, which reached 51.55% in A1-122d, while FM and AM declined to 22.3% and 1.39%, respectively. AM were known to be more susceptible to high organic loads [53], whereas HM often prevail in inhibited systems due to their higher tolerance to environmental stress [27,54]. The methane production decline in both control and pH-adjusted groups indicated that the native HM in the inoculum were insufficient to withstand OLR-induced stresses. Additionally, sodium hydroxide used for pH adjustment may further inhibit methanogenic activity [5]. Thus, the introduction of exogenous functional microorganisms is essential for enhancing system resilience.

Although the methylotrophic methanogenesis pathway is often overlooked due to its minor contribution to total methane yield [55], methylotrophic methanogens (MM) represented by Ca. Methanofastidiosum [56] reached 5.04% and 12.34% in A2 and B2, respectively, suggesting a non-negligible role of methylotrophic metabolism in acid-stressed systems. Previous studies have also highlighted the important role of methylotrophic methanogens in stabilizing methane production in inhibited anaerobic systems [40]. In summary, Methanosarcina, with its metabolic versatility, appears to be a key genus for maintaining methane production under fluctuating OLR and during recovery from acid inhibition. Given the diversity of methanogenic pathways in Methanosarcina [57], the following section will analyze the associated metabolic pathways and key enzyme activities at the genetic level to further elucidate the microbial mechanisms underpinning bioaugmentation.

3.3. Metabolic Analysis

3.3.1. Hydrolysis

The hydrolytic functions across all samples according to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database were shown in Figure 6a. Following the increase in organic loading, the substrate hydrolysis function of AD system was enhanced, attributable to the relatively low sensitivity of hydrolytic and acidogenic bacteria to environmental stressors [58]. The elevated load of digestible substrate promoted the metabolic activity of hydrolytic bacteria. Bioaugmentation specifically enhanced glycine and amino acid metabolism in A3, whereas the metabolic functions across multiple substrates in B3 were broadly strengthened, which successfully recovered from acid inhibition. Given the reduced levels of VFA and sCOD, along with higher methane production observed in bioaugmented systems (Section 3.1), it can be concluded that bioaugmentation improved the utilization efficiency of hydrolyzed substrates. Indeed, even with enhanced carbohydrate and lipid metabolism functions observed in the pH-adjusted B2, the system ultimately failed, indicating that the hydrolysis stage is not the critical limiting factor in acidified systems. Wang et al. demonstrated that pH adjustment enhances hydrolysis but failed to drive the further degradation of organic intermediates [59]. This further confirms that the key bottleneck lies in the subsequent metabolic steps, specifically the inefficient conversion and accumulation of VFA rather than in initial substrate hydrolysis [28].

Figure 6.

(a) The hydrolytic functions across all samples. (b) Relative abundance of syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacteria (SAOB), syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria (SPOB) and syntrophic butyrate-oxidizing bacteria (SBOB).

3.3.2. Acid Metabolism

The underlying reason of acid inhibition is the failure to utilize and metabolize excessive VFA in a timely and effective manner [52]. VFA oxidation plays a critical role in maintaining system stability by enabling efficient VFA metabolism [60]. As summarized in Figure 6b and Figure 7a, the relative abundances of syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacteria (SAOB), syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria (SPOB), and syntrophic butyrate-oxidizing bacteria (SBOB) and related metabolic pathways based on KEGG database were evaluated. Compared with A0, the abundances of SAOB, SPOB, and SBOB decreased markedly in A1. Combined with the VFA accumulation observed in Section 3.1.2, it is evident that the increased OLR coincided with reduced activity of VFA-oxidizing bacteria, thereby impairing VFA metabolism. This finding is consistent with previous studies on acid inhibition [27].

Figure 7.

(a) The main acid-metabolism and methanogenesis pathways in AD system. (b) The heatmap for relative abundance of functional genes in each sample. (c) Principal coordinates analysis of the microbial dynamics. (d) Correlation analysis of the main methanogens and VFAs oxidizers in control samples (bottom left) and bioaugmented samples (top right). Levels of significance: *** p < 0.001.

Figure 6b showed that the bioaugmented systems (A3 and B3), compared with the other acid-inhibited reactors (A1, A2, B1, B2), had lower SAOB abundance but higher abundances of SPOB (e.g., Pelotomaculum, Syntrophorhabdus, Smithella) and SBOB (e.g., Syntrophomonas). Shi et al. concluded that strengthening the oxidation of propionate and butyrate plays a crucial role in mitigating acid inhibition [27]. Changes in key enzyme genes in A3 aligned with shifts in functional bacteria. After bioaugmentation, genes encoding key enzymes in the syntrophic propionate oxidation (SPO) pathway were significantly upregulated: ethylmalonyl-CoA carboxytransferase (EC: 2.1.3.1), propionate CoA-transferase (EC: 2.8.3.1), acetyl-CoA synthetase (EC: 6.2.1.13), and malate dehydrogenase (EC: 1.1.1.37) showed gene abundances 23.36-, 10.67-, 2.46-, and 2.34-fold higher than the control, respectively (Figure 7a,b). In the syntrophic butyrate oxidation (SBO) pathway, medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (EC: 1.3.8.7) catalyzing the conversion of butyryl-CoA to acetyl-CoA, 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (EC: 1.1.1.35), 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (EC: 5.1.2.3), acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase (EC: 2.3.1.9), and enoyl-CoA hydratase (EC: 4.2.1.17) were upregulated by 7.76-, 6.85-, 3.66-, 3.50-, and 3.02-fold higher than control, respectively. These genes encode enzymes critical to the syntrophic oxidation pathways of propionate and butyrate [61]. Conversely, key enzymes related to syntrophic acetate oxidation (SAO) pathway, such as formate dehydrogenase (EC: 1.17.1.10) and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (NADH) (EC: 1.5.1.20) were downregulated, attenuating the conversion of formate to CO2. In B3, nearly all key enzymes in SPO and SBO pathways were enhanced, while the SAO pathway remained largely unaffected. This explained the significantly lower propionate and butyrate levels in bioaugmented reactors compared to non-bioaugmented groups (p < 0.05).

pH-adjusted reactors A2 and B2 exhibited even lower abundances of SPOB compared to the control group, particularly with a marked reduction in Pelotomaculum. This microbial decline was accompanied by the downregulation of key enzyme genes related to SPO pathway, including acetyl-CoA synthase (EC: 6.2.1.1), pyruvate dehydrogenase (EC: 1.2.4.1), malate dehydrogenase (EC: 1.1.1.37/40), and propionyl-CoA carboxylase (EC: 6.4.1.3). These functional impairments in the SPO pathway fundamentally explain the persistent propionate accumulation observed in both A2 and B2. The abundance of Syntrophomonas (SBOB) in reactor A2 was 3.05 times higher than in the control, accompanied by significant upregulation of genes encoding key enzymes in SBO pathway, indicating a functionally enhanced butyrate metabolism. However, since butyrate concentrations remained below 1000 mg·L−1 and did not constitute the primary driver of acid inhibition, this enhancement contributed only marginally to overall process recovery.

In summary, the bioaugmentation strategy alleviated acid inhibition by reinforcing the SPO and SBO pathways, thereby restoring efficient methane production even in already acidified anaerobic digestion systems. In contrast, pH adjustment adversely affected the SPO pathway, exacerbating propionate accumulation and intensifying acid inhibition.

3.3.3. Methanogenesis

As the primary methanogen enriched through bioaugmentation, Methanosarcina exhibited more comprehensive functional versatility and greater metabolic activity across different pathways compared to other methanogens in AD [57]. To elucidate the impact of acid inhibition on methanogenic pathways and the underlying mechanism of bioaugmentation, this Section summarized three principal methane metabolism routes based on the KEGG database (Figure 7a). With increasing OLR, the abundance of key enzyme genes involved in nearly all methanogenesis pathways declined significantly in non-bioaugmented reactors, consistent with the observed reduction in methane production [62].

Compared to the control group, bioaugmented A3 showed marked enhancement in both hydrogenotrophic and methylotrophic methanogenesis. Key enzymes including methanophenazine oxidoreductase (EC: 1.8.98.1), tetrahydromethanopterin S-methyltransferase (EC: 2.1.1.86), methyl-coenzyme M reductase (EC: 2.8.4.1), carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (EC: 1.2.7.4), methylenetetrahydromethanopterin dehydrogenase (EC: 1.5.98.1), 5,10-methenyltetrahydromethanopterin hydrogenase (EC: 1.12.98.2), tetrahydromethanopterin N-formyltransferase (EC: 2.3.1.101), methenyltetrahydromethanopterin cyclohydrolase (EC: 3.5.4.27), coenzyme M methyltransferase (EC: 2.1.1.246/247), and methylamine methyltransferase (EC: 2.1.1.249/250) genes were upregulated [52,63]. Conversely, genes related to the acetoclastic methanogenesis were downregulated (Figure 7b). These shifts, combined with the changes in methanogen (decreased HM and MM, enriched FM) and the relative contributions of Methanosarcina to different type of methanogenesis (Figure 5d and Figure S2), indicated that bioaugmentation primarily reinforced the consumption of methyl compounds and H2/CO2 by Methanosarcina. In the acidified system restored via bioaugmentation, in addition to the enhanced activity of the above enzymes, genes for acetyl-CoA decarboxylase (EC: 2.1.1.245) and acetyl-CoA synthase (EC: 2.3.1.169) were also upregulated. The two enzymes catalyze the critical step of converting Acetyl-CoA to 5,-Methyl-THM(S)PT in the acetoclastic methanogenesis pathway [40]. Among the three methanogenic pathways, methylotrophic methanogenesis was the most significantly enhanced, exhibiting a 4.75-fold increase in the abundance of its key enzyme genes over the control. This enhancement was greater than that observed in hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis (2.14-fold) and acetoclastic methanogenesis (1.50-fold).

In the pH-adjusted reactors A2 and B2, HM constituted the dominant methanogens, while Methanothrix (AM) was also significantly enriched, exceeding the control by 12.37% and 9.94%, respectively. In contrast, the abundance of Methanosarcina (FM) was only 0.26 and 0.21 times that of the control (Figure 5d). Genes of the key enzymes involved in the three methanogenic pathways in A2 showed no significant difference compared to the control, which may explain the lack of substantial improvement in methane production. Although pH adjustment in B2 led to upregulated gene abundance of acetyl-CoA synthase (EC: 2.3.1.169), acetate kinase (EC: 2.7.2.1), and phosphate acetyltransferase (EC: 2.3.1.8), simply enhancing the acetoclastic pathway alone proved insufficient to restore methanogenic performance in the acidified system.

Briefly, bioaugmentation counteracts acid inhibition under elevated OLR by reinforcing hydrogenotrophic and methylotrophic methanogenesis, while the recovery of acidified systems requires the enhancement of all three pathways: hydrogenotrophic, methylotrophic, and acetoclastic methanogenesis.

3.3.4. Osmolality and Energy Metabolism

VFA accumulation is a major factor increasing osmotic pressure in AD systems. Under high osmotic stress, microorganisms enhance adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production by upregulating functional genes for ion/osmoprotectant transport (e.g., nha, trk/ktr, kdp, mnh/mrp, opu, ctp, Prop) and energy conservation (e.g., ech, eha/b, nuo, hdr, mvh, rnf), thereby maintaining cellular osmotic balance and meeting the increased energy demands [64,65,66,67,68,69].

When OLR in control group increased from 2.0 to 4.0 gVS L−1 d−1, most ion transport-related genes (ech, eha/b, mvh, hdr) and energy conversion-related genes (mnh, kdp, proP) were significantly downregulated (Figure 7a,b), reflecting system instability. Bioaugmented reactors A3 and B3 showed marked upregulation of eha, mvh, hdr, nha, kdp, and proP compared to the control. When A3 was further subjected to an OLR of 6.0 gVS L−1 d−1, additional upregulation of ech and opu genes was observed, indicating enhanced microbial capacity for osmotic regulation and energy metabolism [68].

The pH adjustment strategy, while upregulating most osmoregulatory and energy conversion genes and bringing system pH within the optimal range for microbial activity [70], fails to reverse the underlying metabolic impairment. The accumulated inhibitory compounds such as propionate in the system continue to exert detrimental effects on microbial function, preventing process recovery [13,53,54]. In contrast, bioaugmentation addresses the root cause of acid inhibition by functionally restoring key metabolic pathways and syntrophic interactions, enabling genuine system recovery rather than temporary symptomatic relief.

3.4. Regulation of AD System by Bioaugmentation

Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) revealed that the microbial structures of bioaugmented samples A3-140d, A3-200d, and B3-200d were closer to that of the pre-inhibition sample A0-80d, suggesting that bioaugmentation effectively mitigated the microbial disruption caused by elevated organic loading (Figure 7c). As shown in Figure 7d and Figure S3, bioaugmentation altered microbial interaction networks. Methanosarcina exhibited a highly significant negative correlation (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001) with AM, HM such as Methanomicrobia, and Methanoculleus, likely due to competitive exclusion resulting from the enhanced hydrogenotrophic and methylotrophic activities of Methanosarcina following bioaugmentation [40]. Notably, VFA oxidation is thermodynamically constrained and relies on microbial activity to maintain low end-product concentrations [32]. Partnerships between VFA-oxidizing bacteria and methanogens were weaker in control samples than in bioaugmented systems. After bioaugmentation, a highly significant positive correlation was observed between SPOB and Methanosarcina (p < 0.001), as well as between Syntrophobacter and Ca. Methanofastidiosum (p < 0.05), Syntrophus and Methanococcus (p < 0.01), and Thermotoga and Methanosarcina (p < 0.01). Ca. Methanofastidiosum contributed to methane production via methyl-reduction with hydrogen [56], thereby lowering hydrogen partial pressure and facilitating syntrophic VFA oxidation.

The bioaugmentation strategy enhances methane production and system stability by enriching key functional taxa, strengthening essential metabolic pathways, and promoting syntrophic interactions among microorganisms.

4. Conclusions

Bioaugmentation enhanced high-load AD efficiency through multiple synergistic mechanisms: it enriched Methanosarcina, augmented hydrogenotrophic and methylotrophic methanogenesis, reinforced syntrophic partnerships between Methanosarcina and SPOB, and promoted propionate and butyrate metabolism via SPO and SBO pathways. These effects collectively boosted methane production and maintained propionate and butyrate at relatively low levels (below 750 mg·L−1 and 250 mg·L−1, respectively), thereby enabling stable AD performance under a higher organic load of 6.0 gVS L−1 d−1. Furthermore, bioaugmentation upregulated genes responsible for Na+/K+ transport and osmoprotectant uptake, helping to maintain cellular osmotic balance, while also enhancing energy metabolism-related genes to support elevated ATP production under high organic loading. The downregulation of SPOB abundance and key genes critical for propionate oxidation ultimately caused the failure of pH adjustment to resolve acid inhibition and maintain stable operation at 4.0 gVS L−1 d−1. This led to a severe functional impairment and the accumulation of propionate to 1986.36 mg·L−1, causing process collapse. This study elucidates the microbial and metabolic responses following bioaugmentation and pH adjustment, revealing the mechanistic basis for the successful mitigation of acid inhibition via bioaugmentation and the limitations of pH adjustment. Given its potential for practical applications, future work should focus on pilot-scale validation and comprehensive techno-economic analysis to evaluate the real-world feasibility of bioaugmentation as a reliable strategy for digester management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation11120702/s1. Figure S1: Methane content, VS removal, TAN and FAN throughout the experimental period. Figure S2: Relative contribution of multi-pathway methanogenic Methanosarcina to the methane metabolism modules. Figure S3: Correlation analysis of the key functional microorganisms in control samples (bottom left) and bioaugmented samples (top right). Levels of significance: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Table S1: Characteristics of the inoculum and substrate. Table S2: The key functional microorganisms of bioaugmentation consortia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P.; methodology, C.P. and M.D.; software, C.P. and K.Z.; validation, C.P.; formal analysis, C.P.; investigation, Z.W.; resources, K.W.; data curation, C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P.; writing—review and editing, K.W. and Z.W.; visualization, C.P.; supervision, K.W.; project administration, K.W.; funding acquisition, K.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Heilongjiang Chunyan Innovation Team Program, Grant No. CYCX24022; the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Grant No. 52170129; the Project of National Engineering Research Center for Safe Sludge Disposal and Resource Recovery, Grant No. 2024A011; and the State Key Laboratory of Urban-rural Water Resource and Environment (Harbin Institute of Technology), Grant No. 2025DX20.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AD | Anaerobic digestion |

| FW | Food waste |

| OLR | Organic loading rate |

| HRT | Hydraulic retention time |

| VFA | Volatile fatty acid |

| TVFA | Total volatile fatty acids |

| BA | Bioaugmentation |

| PA | pH adjustment |

| sCOD | Soluble chemical oxygen demand |

| TS | Total solids |

| VS | Volatile solids |

| TA | Total alkalinity |

| TVFA/TA | Total volatile fatty acids/Total alkalinity |

| TAN | Total ammonia nitrogen |

| FAN | Free ammonia nitrogen |

| SATP | Standard ambient temperature and pressure |

| KEGG | Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes |

| EC | Enzyme Commission |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| PCoA | Principal coordinates analysis |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| Ca. | Candidatus |

| SAO | Syntrophic acetate oxidation |

| SAOB | Syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacteria |

| SBO | Syntrophic butyrate oxidation |

| SBOB | Syntrophic butyrate-oxidizing bacteria |

| SPO | Syntrophic propionate oxidation |

| SPOB | Syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria |

| AM | Acetoclastic methanogen |

| HM | Hydrogenotrophic methanogen |

| FM | Facultative methanogen |

| MM | Methylotrophic methanogen |

References

- Chen, X.; He, H.; Zhu, N.; Jia, P.; Tian, J.; Song, W.; Cui, Z.; Yuan, X. Food waste impact on dry anaerobic digestion of straw in a novel reactor: Biogas yield, stability, and hydrolysis-methanogenesis processes. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 406, 131023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regueiro, L.; Lema, J.M.; Carballa, M. Key microbial communities steering the functioning of anaerobic digesters during hydraulic and organic overloading shocks. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 197, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Xia, W.; Du, Y.; Li, D.; You, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, L. Enhanced bioavailability of trace elements for improving anaerobic digestion of food waste using sludge extracellular polymeric substances. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 515, 163589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; He, Q.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Peng, X. Dynamics of microbial community in a mesophilic anaerobic digester treating food waste: Relationship between community structure and process stability. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 189, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, G.; Li, L.; Sun, Y. Bioaugmentation for overloaded anaerobic digestion recovery with acid-tolerant methanogenic enrichment. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelklein, M.A.; O’ Shea, R.; Jacob, A.; Murphy, J.D. Role of trace elements in single and two-stage digestion of food waste at high organic loading rates. Energy 2017, 121, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Chen, Y.; Feng, L.; Zhou, Q. Metagenomic analysis reveals nonylphenol-shaped acidification and methanogenesis during sludge anaerobic digestion. Water Res. 2021, 196, 117004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Yang, X.; Lei, Z.; Adachi, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Zhang, Z.; Shimizu, K. Novel insight into enhanced recoverability of acidic inhibition to anaerobic digestion with nano-bubble water supplementation. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 326, 124782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Alvarez, J.; Dosta, J.; Romero-Güiza, M.S.; Fonoll, X.; Peces, M.; Astals, S. A critical review on anaerobic co-digestion achievements between 2010 and 2013. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 36, 412–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Peña, D.C.; Gómez, X. Anaerobic co-digestion of wastes: Reviewing current status and approaches for enhancing biogas production. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, B.; Cai, Y.; Cui, Z.; Wang, X. Bioaugmentation with methanogens cultured in a micro-aerobic microbial community for overloaded anaerobic digestion recovery. Anaerobe 2022, 76, 102603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Town, J.R.; Dumonceaux, T.J. Laboratory-scale bioaugmentation relieves acetate accumulation and stimulates methane production in stalled anaerobic digesters. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wu, S.; Kong, X.; Yuan, Z.; Dong, R. The performance efficiency of bioaugmentation to prevent anaerobic digestion failure from ammonia and propionate inhibition. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 231, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tale, V.P.; Maki, J.S.; Zitomer, D.H. Bioaugmentation of overloaded anaerobic digesters restores function and archaeal community. Water Res. 2015, 70, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, S.M.; Kundu, K.; Sreekrishnan, T.R. Improved stability of anaerobic digestion through the use of selective acidogenic culture. J. Environ. Eng. 2015, 141, 04015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xing, W.; Li, R. Real-time recovery strategies for volatile fatty acid-inhibited anaerobic digestion of food waste for methane production. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 265, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, W.; Wu, Q.; Deng, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, W. Insights into chain elongation mechanisms of weak electric-field-stimulated continuous caproate biosynthesis: Key enzymes, specific species functions, and microbial collaboration. ACS EST Eng. 2023, 3, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Zhao, X.; Ma, Y.; Shi, D. Long-term high-solids anaerobic digestion of food waste: Effects of ammonia on process performance and microbial community. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 262, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohemeng-Ntiamoah, J.; Datta, T. Perspectives on variabilities in biomethane potential test parameters and outcomes: A review of studies published between 2007 and 2018. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 664, 1052–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schievano, A.; D’Imporzano, G.; Malagutti, L.; Fragali, E.; Ruboni, G.; Adani, F. Evaluating inhibition conditions in high-solids anaerobic digestion of organic fraction of municipal solid waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 5728–5732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ma, X.; Sun, H.; Xie, D.; Zhao, P.; Wang, Q.; Wu, C.; Gao, M. Semi-continuous mesophilic-thermophilic two-phase anaerobic co-digestion of food waste and spent mushroom substance: Methanogenic performance, microbial, and metagenomic analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 360, 127518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.-X.; Jianxiong Zeng, R. Inhibitory effects of free propionic and butyric acids on the activities of hydrogenotrophic methanogens in mesophilic mixed culture fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 272, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, G.; Kim, J.; Shin, S.G.; Lee, C. Bioaugmentation of anaerobic sludge digestion with iron-reducing bacteria: Process and microbial responses to variations in hydraulic retention time. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 927–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, T.; Guo, Z.; Liu, W.; Gao, L.; Wang, L.; Cui, M.; Chen, C.; Wang, A. Energy recovery evaluation in an up flow microbial electrolysis coupled anaerobic digestion (ME-AD) reactor: Role of electrode positions and hydraulic retention times. Appl. Energy 2017, 206, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Rhee, C.; Choi, H.; Shin, J.; Shin, S.G.; Lee, C. Long-term effectiveness of bioaugmentation with rumen culture in continuous anaerobic digestion of food and vegetable wastes under feed composition fluctuations. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 338, 125500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Xue, H.; Yao, Y.; Jing, C.; Liu, R.; Niu, Q.; Lu, H. Overcoming methanogenesis barrier to acid inhibition and enhancing PAHs removal by granular biochar during anaerobic digestion. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 477, 147229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, F.; Li, J.; Tao, J.; Sun, Y.; Song, Y.; Duan, Z.; Li, S.; Chen, G. Emerging strategies for enhancing propionate conversion in anaerobic digestion: A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Xue, S.; Raskin, L. Competitive reactions during ethanol chain elongation were temporarily suppressed by increasing hydrogen partial pressure through methanogenesis inhibition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 3369–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, D.; Zhang, K.; Ma, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Gao, X.; Gao, W.; Du, L. Effects of initial volatile fatty acid concentrations on process characteristics, microbial communities, and metabolic pathways on solid-state anaerobic digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 369, 128461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stams, A.J.M.; Plugge, C.M. Electron transfer in syntrophic communities of anaerobic bacteria and archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, B.; Sun, L.; Schnürer, A. First insights into the syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacteria—A genetic study. Microbiologyopen 2013, 2, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achinas, S.; Achinas, V.; Euverink, G.J.W. Chapter 2—Microbiology and biochemistry of anaerobic digesters: An overview. In wBioreactors; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, C.J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Heaven, S. Trace element requirements for stable food waste digestion at elevated ammonia concentrations. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 104, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; He, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wu, D.; Wang, X.; Peng, X. Anaerobic digestion of food waste: Correlation of kinetic parameters with operational conditions and process performance. Biochem. Eng. J. 2018, 130, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi-Banji, A.; Rahman, S. A review of process parameters influence in solid-state anaerobic digestion: Focus on performance stability thresholds. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Li, L.; Peng, Y.; Yang, P.; Peng, X.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X. State indicators of anaerobic digestion: A critical review on process monitoring and diagnosis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 148, 111260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampio, E.; Ervasti, S.; Paavola, T.; Heaven, S.; Banks, C.; Rintala, J. Anaerobic digestion of autoclaved and untreated food waste. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Lin, J.; Zuo, J.; Li, P.; Li, X.; Guo, X. Effects of free ammonia on volatile fatty acid accumulation and process performance in the anaerobic digestion of two typical bio-wastes. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 55, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piao, C.; Wang, K.; Zhu, E.; Wang, Z. Microbial response to varying ammonia conditions in mesophilic anaerobic digestion mediated by mixed bioaugmentation consortia. Environ. Res. 2026, 289, 123365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Li, A.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Yang, C.; Lv, H.; Yao, Y. Microbial mechanisms for higher hydrogen production in anaerobic digestion at constant temperature versus gradient heating. Microbiome 2024, 12, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Shen, Z.; Ren, Z.; Xu, C. Insights into lignocellulose degradation: Comparative genomics of anaerobic and cellulolytic Ruminiclostridium-type species. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1288286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Zhao, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, K.; Zhao, J.; Liang, H.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.-Y.; Hu, C.; Qu, J. Enzyme-enhanced acidogenic fermentation of waste activated sludge: Insights from sludge structure, interfaces, and functional microflora. Water Res. 2024, 249, 120889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahnke, S.; Langer, T.; Koeck, D.E.; Klocke, M. Description of Proteiniphilum saccharofermentans sp. nov., Petrimonas mucosa sp. nov. and Fermentimonas caenicola gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from mesophilic laboratory-scale biogas reactors, and emended description of the genus Proteiniphilum. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1466–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y. Towards engineering application: Integrating current strategies of promoting direct interspecies electron transfer to enhance anaerobic digestion. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2022, 12, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hui, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, H. Boosting volatile fatty acids (VFAs) production in fermentation microorganisms through genes expression control: Unraveling the role of iron homeostasis transcription factors. Water Res. 2024, 259, 121850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qi, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Han, T.; Gong, X.; Shan, M.; Li, G.; Luo, W. Enhancing biogas production from livestock manure in solid-state anaerobic digestion by sorghum-vinegar residues. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 26, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovio-Winkler, P.; Guerrero, L.D.; Erijman, L.; Oyarzúa, P.; Suárez-Ojeda, M.E.; Cabezas, A.; Etchebehere, C. Genome-centric metagenomic insights into the role of Chloroflexi in anammox, activated sludge and methanogenic reactors. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin, M.M.; Salama, Y.; Schellhorn, H.E.; Golding, G.B. Shotgun metagenomic sequencing reveals freshwater beach sands as reservoir of bacterial pathogens. Water Res. 2017, 115, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, J.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Luo, Y.; Tiong, Y.W.; Lam, H.T.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Wang, C.-H.; et al. Enhancing anaerobic digestion of food waste with chemically vapor-deposited biochar: Effective enrichment of Methanosarcina and hydrogenotrophic methanogens. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 424, 132225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.K.; Im, W.T.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, M.H.; Shin, H.S.; Oh, S.E. Dry anaerobic digestion of food waste under mesophilic conditions: Performance and methanogenic community analysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 131, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Euverink, G.J.W. Effect of bioaugmentation combined with activated charcoal on the mitigation of volatile fatty acids inhibition during anaerobic digestion. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 428, 131015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Yan, B.; Liu, C.; Yao, B.; Luo, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Wu, F.; Zhou, Y. Mitigation of acidogenic product inhibition and elevated mass transfer by biochar during anaerobic digestion of food waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 338, 125531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Yan, Q.; Zhong, X.; Angelidaki, I.; Fotidis, I.A. Metabolic responses and microbial community changes to long chain fatty acids: Ammonia synergetic co-inhibition effect during biomethanation. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 386, 129538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, R.; Takeuchi, H.; Hasegawa, T. Methane production from lignocellulosic agricultural crop wastes: A review in context to second generation of biofuel production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 1462–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, D.; Feng, K.; Lou, Y.; Zhou, H.; Liu, B.; Xie, G.; Ren, N.; Xing, D. Polystyrene nanoplastics shape microbiome and functional metabolism in anaerobic digestion. Water Res. 2022, 219, 118606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Sun, H.; Zhou, L.; Arhin, S.G.; Papadakis, V.G.; Goula, M.A.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W. Bioaugmentation with well-constructed consortia can effectively alleviate ammonia inhibition of practical manure anaerobic digestion. Water Res. 2022, 215, 118244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajagopal, R.; Massé, D.I.; Singh, G. A critical review on inhibition of anaerobic digestion process by excess ammonia. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 143, 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Dai, X.; Zhang, D.; He, Q.; Dong, B.; Li, N.; Ye, N. Two-phase high solid anaerobic digestion with dewatered sludge: Improved volatile solid degradation and specific methane generation by temperature and pH regulation. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 259, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Yan, M.; Treu, L.; Angelidaki, I.; Fotidis, I.A. Hydrogenotrophic methanogens are the key for a successful bioaugmentation to alleviate ammonia inhibition in thermophilic anaerobic digesters. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 293, 122070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, A.; Li, Y.; Cai, M.; Luo, G.; Wu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Xing, L.; Zhang, Q. PICRUSt2 functionally predicts organic compounds degradation and sulfate reduction pathways in an acidogenic bioreactor. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2022, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Peng, H.; Li, Y.; Yang, W.; Zou, Y.; Duan, H. Ammonia determines transcriptional profile of microorganisms in anaerobic digestion. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2018, 49, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yuan, W.; Dong, Q.; Wu, D.; Yang, P.; Peng, Y.; Li, L.; Peng, X. Integrated multi-omics analyses reveal the key microbial phylotypes affecting anaerobic digestion performance under ammonia stress. Water Res. 2022, 213, 118152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamalai, T.; Venkitanarayanan, K. Role of proP and proU in betaine uptake by Yersinia enterocolitica under cold and osmotic stress conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 1471–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Guffanti, A.A.; Wang, W.; Krulwich, T.A. Effects of nonpolar mutations in each of the seven Bacillus subtilis mrp genes suggest complex interactions among the gene products in support of Na+ and alkali but not cholate resistance. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 5663–5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanatani, K.; Shijuku, T.; Takano, Y.; Zulkifli, L.; Yamazaki, T.; Tominaga, A.; Souma, S.; Onai, K.; Morishita, M.; Ishiura, M.; et al. Comparative analysis of kdp and ktr mutants reveals distinct roles of the potassium transporters in the model Cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubiger, C.B.; Hoang, K.H.T.; Häse, C.C. Sodium antiporters of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in challenging conditions: Effects on growth, biofilm formation, and swarming motility. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2020, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; He, P.; Zhang, H.; Lü, F. Response of exogenous and indigenous microorganisms in alleviating acetate–ammonium coinhibition during thermophilic anaerobic digestion. ACS EST Eng. 2025, 5, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, S.; San Segundo-Acosta, P.; Protasov, E.; Kaneko, M.; Kahnt, J.; Murphy, B.J.; Shima, S. Electron flow in hydrogenotrophic methanogens under nickel limitation. Nature 2025, 644, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañés, R.; Pérez, M.; Solera, R. Anaerobic mesophilic co-digestion of sewage sludge and sugar beet pulp lixiviation in batch reactors: Effect of pH control. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 255, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).