Abstract

The production of craft beer depends on the quality and availability of yeast. However, many small breweries in developing countries face high costs due to their reliance on imported yeast strains. Developing efficient and low-cost propagation methods is therefore essential for sustainable production. A lager-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain (SC-Lager2) was propagated using both synthetic and low-cost alternative media. The latter was formulated with malt extract as a carbon source and yeast extract obtained from brewery by-products as a nitrogen source. A Plackett–Burman design identified significant factors influencing growth (p < 0.05), and a full factorial design (24) optimized conditions. Growth kinetics and biomass yield were validated at laboratory (2 L) and pilot (83 L) scales. Maltose, yeast extract, zinc sulfate, and agitation significantly affected cell density and viability (p < 0.05). Under optimized conditions, 100% viability, a maximum cell density of 1.4 × 1010 cells/mL, and a biomass yield of 10 g/L were achieved values that were statistically higher (p < 0.05) than those obtained with the synthetic medium. The maximum specific growth rate (μmax) increased by 52%, while doubling time decreased by 39%. Overall, the use of agro-industrial by-products reduced medium costs by approximately 65% compared to conventional synthetic formulations. The proposed low-cost medium provides a scalable, economical, and sustainable solution for yeast propagation, reducing production costs while maintaining high cell viability and performance. This approach supports the autonomy and competitiveness of the craft beer sector in developing regions.

1. Introduction

Craft beer is an alcoholic beverage obtained through fermentation processes, characterized by its high quality and the diversity of methods used in its production, which allows for a wide range of sensory profiles [1]. During production, one of the most important components is yeast, especially the species Saccharomyces cerevisiae for ale-type beers and Saccharomyces pastorianus for lager-type beers, due to their ability to convert wort sugars into ethanol and carbon dioxide [2,3,4].

The fermentation process requires an initial concentration of approximately 15 million cells per milliliter of wort, which can be achieved through a yeast cultivation process [5,6,7]. The use of a suitable inoculum is essential to guarantee enough viable yeast for efficient fermentation. Achieving this involves establishing optimal cultivation conditions that promote high cell concentrations and improving fermentation performance [6]. These conditions include key parameters such as temperature, aeration, agitation, and nutrient availability [8,9]. However, commercial culture media commonly used for yeast cultivation are expensive, which limits their use on an industrial scale and reduces the economic feasibility of the process [10,11].

Beyond optimizing physical parameters, a major challenge lies in developing nutrient media that enables efficient yeast growth at reduced costs. In recent years, several studies have explored alternative low-cost substrates for yeast propagation. For instance, molasses has been used as a carbon source due to its high sugar content, but it often presents compositional variability and requires pretreatment to remove inhibitory compounds [10,12]. Agricultural by-products such as corn steep liquor, rice bran, or extruded legumes have been tested as nitrogen sources, offering low cost but limited reproducibility and batch-to-batch consistency [13,14]. Similarly, brewery spent grain hydrolysates and vegetable waste extracts have shown promise but often lack the micronutrient balance necessary to sustain high yeast viability and biomass yield [15,16]. Several studies have addressed the production and propagation of brewer’s yeast using alternative media, highlighting the importance of optimizing culture conditions to maximize growth and viability, as well as rigorous control of parameters to prevent microbial contamination and loss of active cells [9,17,18]. These studies demonstrate the potential of alternative media but also highlight a persistent limitation: most available low-cost formulations compromise either process reproducibility or biomass productivity compared to synthetic media.

Also, most microbreweries in Ecuador lack dedicated propagation infrastructure and standardized protocols to ensure consistent viability and purity at larger volumes.

Given these limitations, there is a need for a sustainable and reproducible alternative medium that maintains high yeast viability while significantly lowering production costs suitable for small-scale facilities. In this context, yeast waste generated by the brewing industry represents a valuable but underutilized source of nitrogen rich extract [16], and malt extract from barley provides an inexpensive and compositionally stable carbon source. The combined use of these two brewery-derived by-products offers an innovative and circular-economy approach that minimizes costs and valorizes industrial residues.

Therefore, this study was designed to address the technical bottleneck associated with the high cost and limited reproducibility of current low-cost media for yeast propagation. We hypothesize that a medium formulated from brewery-derived yeast extract and malt extract can support yeast growth comparable to that obtained with commercial synthetic media while reducing production costs and maintaining scalability.

To test this hypothesis, we developed and optimized bioprocess for S. cerevisiae biomass production intended for craft beer fermentation. The optimization involved identifying and adjusting key culture parameters to maximize yeast growth and viability, followed by kinetic and scaling evaluations to validate the process under laboratory and pilot conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism and Culture Conditions

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SC-Lager2 strain used in this study was obtained from the institutional microbial collection of Industrial Biotechnology Laboratory at Universidad de las Américas (UDLA), where it had been maintained as a lager-type isolate.

For culture maintenance, a modified Yeast extract Peptone dextrose (YPD) medium was employed. In this formulation, dextrose was replaced with maltose as the carbon source, and the medium was subsequently designated as Yeast Peptone Maltose (YPM). This modification was employed to resemble the sugar composition typically found in beer wort. The medium consisted of 1% yeast extract (™Media, Delhi, India), 2% peptone (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), and 2% maltose (LOBA Chemie, Mumbai, India). Cultures were incubated at 25 °C for 48 h. The incubation temperature was set at 25 °C, consistent with the optimal range for lager-type Saccharomyces strains, which often show improved propagation performance at ~20–25 °C [19,20].

2.2. Molecular Identification

For DNA extraction, a 1 mL aliquot of yeast culture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 1 min, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was resuspended in 100 µL of 10% Chelex and 20 µL of proteinase K (20 mg/mL). The sample was vortexed for 5 s and spun for 10 s. Subsequently, the sample was incubated at 56 °C, with shaking at 180 rpm for 1 h, followed by vortexing for 4 min. A final incubation was performed at 100 °C for 2 min to inactivate the enzyme. The DNA was recovered by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 1 min, and the resulting supernatant was collected for downstream applications [21].

For the yeast specie confirmation, a section of 840 bp of the ITS region was amplified with ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGC-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) primers [22], under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 30 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The resulting PCR product was Sanger sequenced.

Furthermore, a BLAST v2.17.0 and phylogenetic tree analysis was performed. The tree construction was performed by the maximum likelihood method using Tamura-Nei (TN93) with gamma distribution, 1000 bootstraps and Kluyveromyces wickerhamii as an outgroup in the online server NGPhylogeny (https://ngphylogeny.fr/, accessed on 15 May 2025). The sample sequence was uploaded to GenBank under the accession number PV582135.

2.3. Formulation of Culture Media for Propagation

For the propagation of the SC-Lager2 yeast strain, two culture media were evaluated to determine their effect on growth and biomass production. The first was an optimized synthetic medium prepared with high-purity carbon and nitrogen sources and designed to maximize cell growth. The second was a low-cost medium formulated from inexpensive raw materials and agro-industrial by-products as an economical alternative.

2.3.1. Optimized Synthetic Medium

The synthetic medium contained maltose monohydrate (LOBA Chemie, Mumbai, India) as the carbon source, yeast extract (™Media) as the nitrogen source, and zinc sulfate heptahydrate (LOBA Chemie, Mumbai, India) as the zinc source. The medium was sterilized by autoclaving prior to inoculation with the yeast strain. Medium optimization was performed using experimental designs, as described in Section 2.5.

2.3.2. Low-Cost Alternative Culture Medium

To ensure reproducibility and characterize the composition of the alternative medium, the main components were quantified using classical colorimetric methods available in our laboratory. The concentration of reducing sugars in the malt extract was determined using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method, and the protein content of the yeast extract obtained from brewery by-products was measured using the biuret method, following standard laboratory protocols.

The alternative formulation medium developed in this study used a simplified malt extract obtained from locally available malted barley as a major carbon source, and a nitrogen source derived from recovered brewery yeast biomass. This combination aimed to replicate the nutritional composition of production wort while substantially reducing material costs and valorizing brewery by-products.

To obtain the yeast extract, the sediment from residual yeast was collected and subjected to thermal autolysis at 70 °C for 3 h. The resulting suspension was centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C for 15 min. The sterilized solution was centrifuged again under the same conditions and subsequently filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper [23,24].

The malt extract used as a carbon source was produced locally from Ecuadorian barley grains instead of using commercial brewing-grade malt. The barley was milled, mixed with water at 60 °C, and subjected to a mashing process to hydrolyze starches into fermentable sugars for 1 h. The resulting liquid was filtered and concentrated to obtain the malt extract by boiling at 100 °C (Figure S1). This approach was selected to minimize costs and rely on locally available raw materials, since Ecuadorian barley is considerably less expensive than imported refined malt. The alternative media was composed of maltose (10 and 30 g/L), yeast extract (5 and 20 g/L), K2HPO4 (0 and 1 g/L), ZnSO4 (0 and 14 mg/L), pH (4.5 and 5.5), and agitation (0 and 150 rpm), depending on the selected treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Factor and levels evaluated in Plackett–Burman experimental design.

A small amount of zinc sulfate heptahydrate (2 mg/L) was included in the formulation study to ensure consistent availability of zinc, an essential cofactor in yeast metabolism. Although yeast extract provides trace minerals, supplementation was performed to minimize batch variability associated with by-product-derived extracts and to improve process reproducibility [25].

Other trace elements were not supplemented individually, following brewers’ recommendations to avoid potential toxicity or undesirable sensory effects in the final product.

2.4. Analytical Methods of Quantification

2.4.1. Cell Density Determination

Cell density was determined by counting total and viable cells using an improved Neubauer chamber (BOECO, Hamburg, Germany). Counts were performed in the four outer quadrants, considering 16 squares per quadrant, and expressed as the number of cells per milliliter. Cell viability was assessed by comparing the number of viable cells with the total cell count, differentiating non-viable cells by blue staining with methylene blue [26].

This direct counting method was selected because it allows simultaneous quantification of total and viable cells and avoids potential interferences caused by medium turbidity or suspended solids when using optical density measurements. In addition, it represents a practical and accessible approach that can be implemented in small-scale brewery laboratories without requiring specialized equipment.

2.4.2. Biomass Concentration Determination

The biomass concentration was determined gravimetrically using the dry weight method. Aluminum foil caps were pre-dried in an oven for 24 h and weighed using an analytical balance. Each culture sample was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C and washed three times with distilled water. After the final wash, the pellet was transferred to the pre-weighed aluminum caps, dried in an oven, and weighed at room temperature until a constant weight was achieved [27,28].

2.5. Experimental Design

The optimization of the culture medium for the propagation of S. cerevisiae was carried out in two consecutive experimental stages.

2.5.1. Selection of Significant Variables Using Plackett–Burman Design

A Plackett–Burman experimental design was applied for the identification of the most significant factors on cell viability. Six independent variables were evaluated: maltose, yeast extract, agitation, zinc sulfate, dipotassium hydrogen phosphate and pH (Table 1).

The temperature was kept constant at room temperature throughout the experiment. The design generated a total of eight treatments, and the percentage of cell viability after 24 h of incubation was used as the response variable. The design and statistical analysis were performed in RStudio (2025.5.1.513.3), using packages like “rsm, FrF2, car, stats, agricolae”. As reference values reported in the literature to establish concentration ranges. The data obtained from cell counting and viability assessment were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using a Tukey HSD post hoc test at a 95% confidence level. Tukey test with a 95% significance level to determine the statistical influence of each factor on the response.

2.5.2. Treatment Optimization Using Complete Factorial Design 24

Based on the results obtained in the first stage, the four most significant factors were selected for optimization using a full factorial design 24. The evaluated factors and their corresponding and levels are presented in Table 2, resulting in a total of 16 treatments.

Table 2.

Factors and levels evaluated in factorial design 24.

After 24 h of incubation, cell density and viability were assessed following the methodology described in Section 2.4. The treatment showing the highest percentage of viability and cell density was considered optimal and subsequently used for an additional validation experiment, in which the kinetic parameters of growth and substrate consumption were determined (Section 2.7).

2.6. Validation and Scaling up of Low-Cost Culture Medium (Scale-Up)

The validation of the alternative culture medium was performed on a laboratory scale in a 2 L flask with a working volume of 1.4 L, under controlled conditions (pH 5.5, 100 rpm, and 25 °C). The samples were incubated for 72 h, with measurements taken at regular intervals to estimate the growth kinetics. During this stage, key parameters such as cell density and biomass production were monitored to evaluate the reproducibility of the process.

Scale-up experiments were conducted in a custom-designed 83 L pilot bioreactor, adapted from a stainless-steel fermenter by modifying its lid to include ports for agitation, sampling, and temperature control. The operating conditions were maintained at 25 °C, pH 5.5, and agitation speed of 100 rpm. These parameters were selected based on laboratory optimization results to assess the reproducibility of the process at pilot scale, maintaining the same previously optimized culture conditions. Inoculation was performed with an initial cell density of 1 × 107 cells/mL, replicating the conditions used in the small-scale trials.

2.7. Estimation of Growth Kinetic

The estimation of growth kinetic parameters was determined both in the 1.4 L flask and in the 83 L stirred tank bioreactor, including the maximum specific growth rate (μmax) (Equation (1)) and the doubling time (td) (Equation (2)) [29].

The specific growth rate (μ) was calculated using the exponential growth model:

where μmax is the specific growth rate (h−1), x1 and x2 are the biomass concentrations (g/L) at times t1 and t2 (h), respectively.

The doubling time (td) was determined as:

All parameters were calculated from experimental data obtained under optimized culture conditions at both laboratory and pilot scales. Sampling intervals were strategically chosen to represent the lag, exponential, and stationary growth phases, ensuring reliable estimation of kinetic parameters.

3. Results

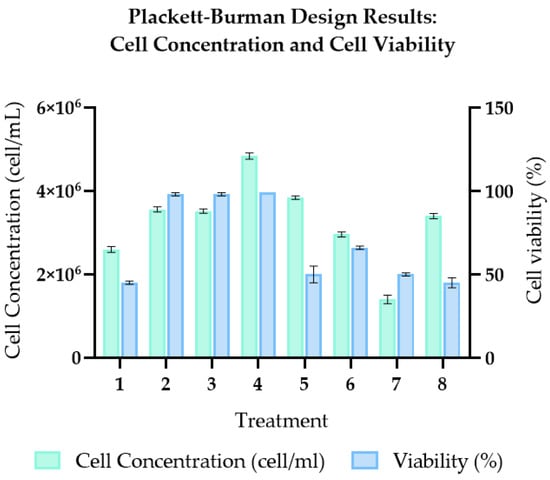

Optimization of the culture medium significantly improved yeast growth and viability. Through a Plackett–Burman experimental design, key factors influencing cell growth were identified, including maltose concentration, yeast extract, zinc sulfate, and agitation. Subsequently, the factorial design allowed for maximizing cell density and viability, achieving 100% viability in several treatments.

Validation of the optimized medium at different scales demonstrated efficient growth kinetics, characterized by faster doubling rates and higher biomass production compared to the synthetic medium. At both laboratory and prototype scales, cell concentration and biomass value exceeded those obtained with the conventional medium, highlighting its potential as a viable and cost-effective alternative for yeast propagation.

3.1. Microorganism and Culture Conditions

To achieve effective growth, the yeast was reactivated in YPM medium, which promoted rapid adaptation to the substrate and optimal growth, reaching a cell concentration of 1.28 × 107 cells/mL. These results demonstrate not only efficient utilization of maltose as a carbon source, but also the favorable physiological response of the strain to the modified medium.

3.2. Molecular Identification

After performing, the BLAST analysis of the sequence, a 99.82% identity was obtained for a Saccharomyces cf. bayanus/pastorianus (KY104984) and S. cerevisiae (MZ098694) strains. To confirm the identification, a maximum-likelihood tree was performed and confirmed that the sample was S. cervisiae with 999 bootstrap values. Additionally, the sample was located within the clade of S. bayanus and S. pastorianus, suggesting that it could be lager-type strain (Figure S2).

3.3. Experimental Designs

3.3.1. Significative Variables Selection by Plackett–Burman Design

Based on the results obtained from the Plackett–Burman design, treatment 4 was identified as having the best performance, achieving 99% cell viability and a density of 4.84 × 106 cells/mL (Tables S1 and S2, Figure 1). Statistical analysis using ANOVA revealed that the variables with a significant effect on the growth of S. cerevisiae were maltose (p = 0.020), commercial yeast extract (p = 0.031), ZnSO4 (p = 0.018), and agitation (p = 0.011; Table S2).

3.3.2. Treatment Optimization by Factorial Design 24

The factorial design was applied to the significant variables identified in the Plackett–Burman design (Table S3). It showed 100% cell viability for treatments 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, and 16. Among these, treatment 16 exhibited the highest cell density, reaching 1.89 × 107 cells/mL.

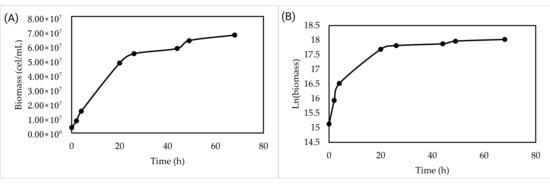

3.4. Validation of Optimized Synthetic Medium at Laboratory Scale

The validation of the optimized synthetic medium at the laboratory scale showed that the yeast growth phases were clearly distinguishable (Figure 2). A very short lag phase was observed, followed by an exponential phase that lasted up to 24 h. Subsequently, the yeast enters a stationary phase that covers the rest of the process. After 72 h of incubation, a cell concentration of 6.72 × 107 cells/mL and a biomass concentration in dry weight of 1.8 g/L were reached.

Figure 2.

Growth kinetics in synthetic culture medium at laboratory scale (0.5 L). (A) Growth kinetics over 72 h. (B) Semilogarithmic growth to observe the growth phases of SC-Lager2.

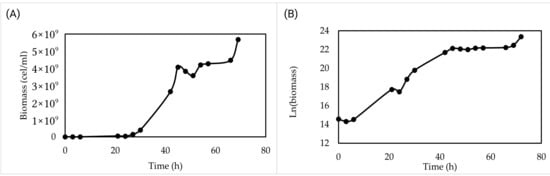

3.5. Validation in Low-Cost Culture Medium at Laboratory and Pilot Scale

Validation at laboratory scale (2 L) revealed the following growth profile: a brief lag phase until hour 6, followed by exponential growth that lasted until hour 45. In the linear plot (Figure 3A), temporary fluctuations and apparent lag duration are more pronounced, while the steep slope in the semilogarithmic representation (Figure 3B) clearly shows the exponential phase. From hour 45 onward, the growth rate slowed, reflected in the flattening of the slope in the semilogarithmic plot. After 72 h of incubation, the cell concentration reached 1.4 × 1010 cells/mL, and the biomass was 10 g/L.

Figure 3.

Growth kinetics in low-cost culture medium at laboratory scale (2 L). (A) Growth kinetics over 72 h. (B) Semilogarithmic growth to observe growth phases.

A slight deviation observed around 70 h was attributed to transient variations in mixing conditions during cultivation; however, this did not affect the overall reproducibility or the kinetic parameters derived from the growth curve.

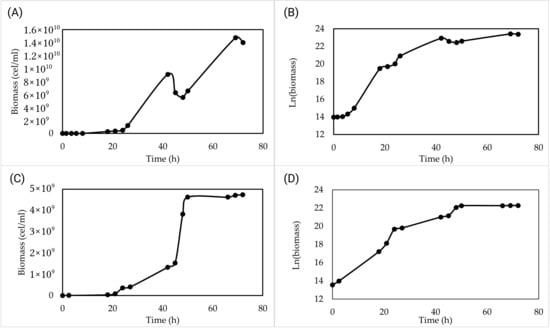

Pilot-scale validation was performed in duplicate in an 83 L bioreactor. For the first validation, the growth kinetics showed a pattern observed at the laboratory scale, identifying the three classic phases of growth, lag, exponential, and stationary. These phases, including the brief lag phase lasting until approximately 6 h, the end of the exponential phase at 42 h, and the transition to the stationary phase after 42 h, are clearly visualized in the semilogarithmic representation (Figure 4B), which linearizes the exponential growth phase and allows accurate assessment of growth kinetics. In contrast, Figure 4A shows the same data on a linear scale, where temporary fluctuations appear more pronounced and the growth pattern differs from the second validation. The semilogarithmic plots of the second validation (Figure 4D) are very similar to the first (Figure 4B), indicating consistent growth kinetics, whereas the linear plots (Figure 4C) differ in appearance due to the scale. In the first validation, the final cell concentration was 1.4 × 1010 cells/mL, and the biomass reached 9.62 g/L.

Figure 4.

Growth kinetics in low-cost culture medium at pilot scale (83-liter capacity). (A) Validation 1 of growth kinetics in 72 h with the optimized low-cost medium. (B) Validation 1 of semilogarithmic growth to observe the growth phases of SC-Lager2 with the optimized low-cost medium. (C) Validation 2 of growth kinetics in 72 h with the optimized low-cost medium. (D) Validation 2 of semi-logarithmic growth to observe the growth phases of SC-Lager2 with the optimized low-cost medium.

For the second validation, the growth kinetics showed a pattern like the first, with an exponential phase from 6 h to 42 h, followed by a stationary phase. On this occasion, the final cell density at 72 h was 4.7 × 109 cells/mL, and the biomass reached 8.14 g/L.

3.6. Comparison of Kinetic Parameters

The results obtained from the kinetic parameters revealed differences between the optimized synthetic culture medium and the low-cost alternative medium. In terms of maximum growth rate (µmax), a notable increase was observed in the laboratory-scale validation of the alternative medium, reaching a value of 0.202 h−1 at a volume of 2 L, representing an increase of approximately 26% compared to the value of 0.16 h−1 obtained with the synthetic medium at a volume of 500 mL (Table S4).

It is important to note that the kinetic results obtained for the synthetic and low-cost media are not directly comparable, as each formulation was optimized and evaluated under specific conditions according to its physicochemical characteristics. The analysis therefore focuses on the reproducibility and scalability of the proposed low-cost medium rather than on direct yield equivalence between both systems.

On a pilot scale, the prototype showed a µmax of 0.244 h−1 in validation 1, which exceeded the maximum growth rate observed in the synthetic medium under the same conditions by 52%. However, in validation 2, the µmax of the alternative medium decreased to 0.185 h−1, reflecting a slight decrease compared to validation 1.

Regarding doubling time, the alternative medium showed significant improvement. At the laboratory scale, the doubling time was reduced by 27% from 4.67 h with the synthetic medium to 3.42 h with the alternative medium. At the prototype level, the doubling times were 2.83 h in the first validation and 3.74 h in the second, compared to 4.67 h for the synthetic medium in the laboratory.

In terms of biomass, the alternative medium showed superior performance under all cultivation conditions. At the laboratory scale, a biomass of 10 g/L was achieved, almost six times more than the 1.8 g/L obtained with the synthetic medium. In industrial-scale validation, the biomass was 9.62 g/L in the first validation, with a slight decrease to 8.14 g/L in the second.

In terms of cell density, the alternative medium also outperformed the synthetic medium. After 72 h of cultivation, a cell density of 1.4 × 1010 cells/mL was obtained in the validation of the alternative medium at 2 L, representing an increase of more than 20 times compared to the 6.72 × 107 cells/mL of the synthetic medium. On an industrial scale, cell densities were equally high, reaching 1.4 × 1010 cells/mL in the first validation, and although in the second validation it was reduced to 4.74 × 109 cells/mL, the figure was still considerably high compared to the values obtained with the synthetic medium.

To place our results in context, we compiled representative KPI values from studies that propagated S. cerevisiae using common low-cost substrates (molasses, corn steep liquor, whey permeate and spent brewery yeast). The comparison (Table 3) shows that the biomass achieved with our brewery-derived medium (10 g·L−1 in laboratory validation) is higher than many reported low-cost formulations and that our observed µmax values (0.202–0.244 h−1) are competitive with literature ranges. These differences underscore that direct numeric comparisons must be interpreted cautiously because KPI values depend strongly on strain, inoculum, cultivation time, feeding strategy, and analytical methods; nevertheless, the compiled Table 3 demonstrates that our brewery-derived medium performs at least as well as many documented low-cost alternatives while offering the additional advantage of valorizing brewery waste.

Table 3.

Comparison of key performance indicators (KPI) for yeast biomass production on low-cost substrates.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively evaluate the optimization of a low-cost culture medium for yeast propagation in an industrial context, with emphasis on its performance relative to commercial synthetic media. Yeast growth in liquid cultures is influenced by multiple interrelated factors, including nutrient availability, environmental conditions, and the physicochemical properties of the medium. The optimization of culture media is therefore essential to enhance process efficiency, particularly when aiming for more accessible and sustainable alternatives for industrial applications.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively evaluate the optimization of low-cost culture medium for yeast propagation in an industrial context, with emphasis on its performance relative to commercial synthetic media. Yeast growth in liquid cultures is influenced by multiple interrelated factors, including nutrient availability, environment conditions, and the physicochemical properties of the medium. The optimization of culture media is therefore essential to enhance process efficiency, particularly when aiming for more accessible and sustainable alternatives for industrial applications [34]. This represents a growing need in countries such as Ecuador, where the high cost of imported commercial synthetic media poses a significant challenge for local industries. The use of low-cost media not only provides an economically viable solution but also reduces dependence on imported inputs and promotes local production, thereby generating a positive impact on the national economy.

In this study, several key factors influencing yeast growth and viability were evaluated, including agitation, essential nutrient concentrations, and carbon and nitrogen sources. Agitation played a crucial role in the optimization process, as it not only enhanced the homogeneous distribution of nutrients and oxygen throughout the medium but also contributed to system stability and prevented the formation of gradients that could adversely affect cell viability [35]. In fact, adequate agitation facilitates the formation of a more homogeneous environment, which improves the metabolic efficiency of yeasts, resulting in faster growth and higher biomass concentration.

In terms of nutrients, zinc, maltose, and yeast extract were identified as essential components promoting both cell growth and viability. These nutrients play key roles in protein synthesis, cell structure formation, and overall metabolic efficiency in yeast [36].

In particular, the combination of maltose as a carbon source and yeast extract as a nitrogen source proved decisive for maximizing cell growth. While zinc was deliberately included as a key micronutrient due to its enzymatic and metabolic roles, additional trace elements such as magnesium, manganese, copper, and iron were not individually optimized. Following recommendations from experienced brewers, their supplementation was limited to avoid potential toxicity or undesirable sensory effects in the final beer. The intrinsic composition of the yeast extract provided sufficient baseline levels of these elements to sustain balanced and reproducible yeast growth. These findings indicate that the low-cost medium, although simpler in composition, can deliver comparable or even superior performance to commercial synthetic media in terms of biomass production and cell density.

An interesting observation was that the low-cost alternative medium supported a higher growth rate and greater biomass accumulation than the synthetic medium. This result underscores the efficiency of alternative formulations that, despite being less expensive, maintain the quality and robustness of the biological process. Such outcomes are especially significant for industries in developing countries like Ecuador, where high production costs are often driven by the need to import culture media components. Therefore, the optimization of low-cost media represents a viable strategy not only from an economic standpoint but also in terms of long-term environmental and industrial sustainability.

The superior performance of the low-cost medium compared to the synthetic formulation can be attributed to its richer biochemical composition and the synergistic interaction between its carbon and nitrogen sources. The yeast extract recovered from brewery by-products likely retains a complex mixture of amino acids, short peptides, B-group vitamins, and trace minerals that act as essential cofactors in central metabolic pathways, including glycolysis and amino acid biosynthesis. In addition, spent yeast extract has been reported to contain antioxidant molecules such as glutathione and other reducing compounds that protect cells from oxidative stress during propagation, contributing to higher viability and shorter doubling times [16,23,24]. When combined with malt extract, which provides a balanced mixture of fermentable sugars (mainly maltose and maltotriose) and low levels of dextrins, the medium may facilitate more efficient energy metabolism and biomass accumulation. This biochemical richness and synergistic nutrient balance explain the enhanced kinetic behavior observed in the alternative medium relative to the synthetic one [3].

In addition, the malt extract used in this study was produced from locally sourced Ecuadorian barley, rather than commercial brewing-grade malt. This adaptation substantially reduced raw material costs while maintaining adequate sugar composition for yeast growth. The use of local barley, combined with yeast extract recovered from brewery residues, reinforces the sustainability and economic feasibility of the proposed low-cost propagation medium.

The study demonstrated that agitation was one of the most decisive factors influencing yeast biomass production, playing a key role in enhancing culture performance. Agitation facilitates the uniform distribution of nutrients and oxygen, both essential for the aerobic metabolism of yeast, thereby optimizing growth conditions. Moreover, it prevents the formation of concentration gradients that could compromise cell viability, ensuring a more stable and efficient culture environment [36,37]. The importance of agitation in yeast cultures has been widely documented, and it has been proven that optimizing agitation not only improves the availability of these resources, but also increases the stability of the system, which is essential in large-scale industrial processes.

Along with agitation, other factors such as the availability of micronutrients and the selection of appropriate carbon and nitrogen sources significantly influence yeast performance. Zinc, as an essential micronutrient, plays a fundamental role in numerous enzymatic processes critical for cell growth and metabolism [15]. Additionally, maltose serves as an effective carbon source, providing the energy required for metabolic activity, while yeast extract functions as a nitrogen source that supports protein synthesis and the formation of essential cellular components [36]. The interaction among these nutritional factors is crucial for optimizing yeast viability and proliferation during cultivation, underscoring the importance of refining growth medium formulation.

The composition and characteristics of both media are key to interpreting comparative results. The synthetic medium was formulated with high-purity inputs, such as maltose monohydrate and commercial yeast extract, and supplemented with zinc sulfate, an essential micronutrient that acts as a cofactor for enzymes involved in central metabolism, protein synthesis, and cell division. Zinc supplementation contributed to enhanced cell growth, viability, and reproducibility, as reflected in the optimization results. Other micronutrients naturally present in yeast extract, including magnesium, trace elements, and B-group vitamins, further supported metabolic activity, although their levels were not independently optimized [13].

The alternative medium, developed from agro-industrial by-products such as recovered brewery yeast extract, substantially reduced production costs and promoted sustainability [14]. A key limitation of using brewery-derived by-products as components of low-cost propagation media is their intrinsic compositional variability. Factors such as raw material source, processing conditions, and storage can affect the levels of sugars, amino acids, peptides, vitamins, and trace minerals in yeast extract and malt-derived residues. Such variability may influence yeast growth kinetics, biomass yield, and viability, potentially impacting reproducibility at both laboratory and larger scales. To address this challenge, future research should focus on establishing routine quality control procedures, including rapid assays for key parameters (reducing sugars and protein content) and batch-to-batch consistency checks.

Both media proved suitable for the propagation of S. cerevisiae; however, from an economic and environmental standpoint, the alternative medium represents a promising option for small and medium-sized breweries seeking greater autonomy in yeast production without compromising microbiological quality (Table S5).

The results obtained in this study confirm the effectiveness of the commercial medium used as a reference, in which the final biomass exceeded the initial inoculum of 0.5 g/L, reaching values comparable to those reported by Cardozo and Moreno [12], who achieved a final biomass of 1.861 g/L under similar conditions. Nevertheless, when compared with the results obtained using the proposed alternative medium, a substantial increase in both final cell concentration and biomass was observed. After 72 h of cultivation, the alternative medium reached a cell concentration of 1.4 × 1010 cells/mL and a biomass of 10 g/L, representing a significant improvement relative to the commercial medium. Although previous studies such as that of Cáceres [10] reported higher values under specific conditions, particularly when using molasses as the carbon source, the results obtained with the proposed medium remain competitive. This difference can be attributed to the nature of the carbon source: molasses contains simple sugars that are rapidly assimilated by the yeast, whereas the malt extract used in the alternative medium primarily provides disaccharides such as maltose, which require additional metabolic processing time for assimilation.

The scale-up stage demonstrated that the optimized low-cost medium and process parameters were reproducible at pilot scale, confirming the robustness of the proposed bioprocess. Although the transition was made directly from 2 L shake flasks to an 83 L pilot bioreactor, this decision was based on equipment availability and the applied nature of the study. The pilot reactor was adapted from a stainless-steel fermenter with a modified lid, enabling agitation, temperature control, and sampling under semi-controlled conditions. Despite the differences in hydrodynamic behavior between orbital shaking and mechanical agitation, the process maintained comparable cell viability and biomass yields, demonstrating that the optimized conditions can be effectively transferred to larger volumes typical of small-scale brewing operations. These results support the feasibility of implementing the proposed medium and protocol in local craft breweries with limited infrastructure.

The increase in growth rate observed between the laboratory-scale and 58 L validations suggests that the optimized medium retains its effectiveness under higher-volume conditions, although further adjustments may enhance process efficiency. The variations detected in biomass and cell concentration could be attributed to differences in nutrient and oxygen distribution within the bioreactor, particularly at larger scales. As noted by Xia et al. [38] during bioprocess scale-up, challenges associated with flow heterogeneity and nutrient or oxygen gradients can lead to alterations in cell physiology, ultimately affecting biomass production. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing agitation intensity and dissolved oxygen control systems to ensure process homogeneity and maximize yield.

Although both pilot-scale validation runs followed similar overall growth patterns, differences were observed in the final cell concentration and biomass. Since the initial inoculum was identical in both experiments, variations in inoculum density or physiological state are unlikely to account for these discrepancies. Agitation speed was maintained constant, suggesting a minimal contribution to the observed variation. Nevertheless, subtle differences in oxygen transfer within the 83 L bioreactor may have influenced growth kinetics and biomass accumulation, as even minor changes in mixing or aeration efficiency can significantly impact yeast proliferation at pilot scale.

Additionally, the alternative culture media were manually prepared in separate batches, which may have introduced slight batch-to-batch variability in nutrient composition and quality, further contributing to the observed differences. Collectively, these factors underscore the inherent variability of pilot-scale operations, particularly when using locally prepared, alternative media, and provide a plausible explanation for the discrepancies observed between the two runs.

In summary, the results of this study provide a strong foundation for the use of low-cost alternative media in yeast production. The optimized culture medium demonstrated high effectiveness in terms of growth rate, biomass concentration, and cell viability, outperforming the commercial synthetic medium across several key parameters. These findings are particularly relevant for countries such as Ecuador, where the cost of imported synthetic media remains a significant barrier. The adoption of alternative media not only has the potential to reduce production expenses but also contributes to the sustainability and self-sufficiency of local industries, fostering a more accessible and sustainable model of biotechnology in the long term.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the combination of malt extract and brewery-derived yeast extract constitutes an effective, reproducible and low-cost medium for the propagation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Under optimized conditions, the process achieved 100% cell viability, a biomass yield of 10 g/L, and a maximum cell density of 1.4 × 1010 cells/mL, representing a 52% increase in growth rate compared with the synthetic medium. These results confirm the technical feasibility of producing high-quality yeast biomass using locally available agro-industrial by-products.

The proposed bioprocess provides a sustainable and economically viable alternative for the craft beer sector, particularly in developing regions where dependence on imported yeast strains substantially increases production costs. By valorizing brewery waste streams, this approach supports a circular bioeconomy model and strengthens the technological autonomy of local breweries.

Future work will focus on scaling the process to industrial fermenters and performing pilot-scale brewing trials to evaluate the metabolic performance of the propagated yeast and its influence on beer flavor and aroma. In addition, life cycle and techno-economic assessments will be conducted to quantify the environmental and economic benefits of implementing this low-cost propagation technology at commercial scale.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation11120688/s1: Figure S1. Preparation of the alternative medium. (Left) Production of yeast extract from brewery waste yeast. (Right) Preparation of malt extract from malted barley.; Figure S2. Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic ITS tree of SC-Lager2; Table S1. Plackett–Burman experimental design for the evaluation of significant variables.; Table S2. Estimated effects, standard errors, t-values, and p-values for independent variables in the Plackett–Burman design.; Table S3. Full factorial (24) experimental design used to evaluate the influence of different variables on cell concentration and viability.; Table S4. Kinetic parameters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae growth in optimized synthetic and low-cost culture media evaluated at laboratory (500 mL and 2 L) and prototype (83 L) scales during process validation.; Table S5. Comparison of culture media components reported for the propagation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B.-C. and M.A.C.; methodology, M.A.C. and D.V.; software, A.R.; validation, J.R., F.H.-A. and C.B.-C.; formal analysis, M.A.C., A.R. and D.V.; investigation, J.R., A.R. and F.H.-A.; resources, C.B.-C.; data curation, D.V. and J.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.C.; writing—review and editing, C.B.-C. and M.A.C.; visualization, M.A.C.; supervision, C.B.-C. and M.A.C.; project administration, M.A.C. and C.B.-C.; funding acquisition, M.A.C. and C.B.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The experimental work was supported by the Biotechnology Engineering Program at Universidad de las Américas. The article processing charges (APCs) were covered by Universidad de las Américas.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chacon Cuevas, T. Beer Fermentation Tank Module; Centria University of Applied Sciences: Kokkola, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bonatto, D. The Diversity of Commercially Available Ale and Lager Yeast Strains and the Impact of Brewer’s Preferential Yeast Choice on the Fermentative Beer Profiles. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.G. Saccharomyces Species in the Production of Beer. Beverages 2016, 2, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Takahashi, T. Studies on the Genetic Characteristics of the Brewing Yeasts Saccharomyces: A Review. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2023, 81, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracín Torres, K. Estudio de Parámetros Para La Propagación de Las Cepas de Levadura Cervecera Saccharomyces Cerevisiae y Saccharomyces Carlsbergensis Para La Fabricación de Cerveza Artesana; Universidad Politécnica de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Beugholt, A.; Geier, D.U.; Becker, T. The Role of Yeast Propagation Aeration for Subsequent Primary Fermentation with Respect to Performance and Aroma Development. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 7346–7356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.R.B.; Douradinho, R.S.; Sica, P.; Mota, L.A.; Pinto, A.U.; Faria, T.M.; Baptista, A.S. Evaluation of Aerobic Propagation of Yeasts as Additional Step in Production Process of Corn Ethanol. Stresses 2024, 4, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigbeder, J.B.; de Medeiros Dantas, J.M.; Lavoie, J.M. Optimization of Yeast, Sugar and Nutrient Concentrations for High Ethanol Production Rate Using Industrial Sugar Beet Molasses and Response Surface Methodology. Fermentation 2021, 7, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso Lopes Cardoso, A.B.F. Implementation and Optimization of a Yeast Propagation Method for Craft Beer Production. Universidad do Porto: Port, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres, N.G.M. Producción de Biomasa Líquida de Levaduras Cerveceras En Un Medio de Cultivo Alternativo: Biomasa Liquida de Levaduras. Steviana 2023, 14, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, K.A.; Fernandes, K.F. Development and Optimization of a New Culture Media Using Extruded Bean as Nitrogen Source. MethodsX 2015, 2, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo Guzmán, M.C.; Moreno Cardozo, J.H. Diseño y Optimización de Un Medio de Cultivo a Base de Melaza de Caña Para La Producción de Biomasa a Partir de Saccharomyces Cerevisiae; Pontificia Universidad Javeriana: Bogotá, Colombia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, T.M.; Kaltenbach, H.M.; Rudolf, F. Development and Optimisation of a Defined High Cell Density Yeast Medium. Yeast 2020, 37, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lino, F.S.D.O.; Basso, T.O.; Sommer, M.O.A. A Synthetic Medium to Simulate Sugarcane Molasses. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López de Romaña, D.; Castillo, D.C.; Diazgranados, D. Zinc in Human Health—I. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2010, 37, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, F.F.; Striegel, L.; Rychlik, M.; Hutzler, M.; Methner, F.J. Spent Yeast from Brewing Processes: A Biodiverse Starting Material for Yeast Extract Production. Fermentation 2019, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiralal, L.; Olaniran, A.O.; Pillay, B. Aroma-Active Ester Profile of Ale Beer Produced under Different Fermentation and Nutritional Conditions. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2014, 117, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, C.; Wackerbauer, K.; Kyung Lee, S.; Ah Kang, S. Optimal Conditions for Propagation in Bottom and Top Brewing Yeast Strains. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2008, 17, 739–744. [Google Scholar]

- Sui Generis Brewing Optimizing Yeast Starters and Large-Scale Yeast Production. Available online: https://suigenerisbrewing.com/index.php/2022/09/20/optimizing-yeast-starters/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Escarpment Laboratories Best Practices—Yeast Propagation. Available online: https://knowledge.escarpmentlabs.com/article/68-propagating-yeast-best-practices (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Blount, B.A.; Driessen, M.R.M.; Ellis, T. GC Preps: Fast and Easy Extraction of Stable Yeast Genomic DNA. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korabečná, M.; Liška, V.; Fajfrlík, K. Primers ITS1, ITS2 and ITS4 Detect the Intraspecies Variability in the Internal Transcribed Spacers and 5.8S RRNA Gene Region in Clinical Isolates of Fungi. Folia Microbiol. 2003, 48, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, M.; Pereira, J.O.; Gomes, D.; Pereira, C.D.; Pinheiro, H.; Pintado, M. Nutritional Ingredients from Spent Brewer’s Yeast Obtained by Hydrolysis and Selective Membrane Filtration Integrated in a Pilot Process. J. Food Eng. 2016, 185, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Yuan, H.; Liu, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, D.; Wang, T. Yeast Extract: Characteristics, Production, Applications and Future Perspectives. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 33, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nicola, R.; Walker, G.M. Zinc Interactions with Brewing Yeast: Impact on Fermentation Performance. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2011, 69, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, K.M.R.; Gomes, L.H.; Sampaio, A.C.K.; Issakowicz, J.; Rocha, F.; Granato, T.P.; Terra, S.R. Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Used As Probiotic: Strains Characterization And Cell Viability. IOSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2012, 1, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J.F.; Sullivan, T.R.; Helbert, J.R. A Rapid Method for the Determination of Yeast Dry Weight Concentration1. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 1980, 38, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Mira De Orduña, R. A Rapid Method for the Determination of Microbial Biomass by Dry Weight Using a Moisture Analyser with an Infrared Heating Source and an Analytical Balance. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 50, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, P.M. Bioprocess Engineering Principles, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-12-220851-5. [Google Scholar]

- Trigueros, D.E.G.; Fiorese, M.L.; Kroumov, A.D.; Hinterholz, C.L.; Nadai, B.L.; Assunção, G.M. Medium Optimization and Kinetics Modeling for the Fermentation of Hydrolyzed Cheese Whey Permeate as a Substrate for Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Var. Boulardii. Biochem. Eng. J. 2016, 110, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, A.E.; Madzimbamuto, T.N.; Ojumu, T.V. Optimization of Corn Steep Liquor Dosage and Other Fermentation Parameters for Ethanol Production by Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Type 1 and Anchor Instant Yeast. Energies 2018, 11, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkessa Jiru, T.; Abate, D. Evaluation of Yeast Biomass Production Using Molasses and Supplements; LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing: Saarbrücken, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ali Khalid, K.; Tama, B.; Taleb, T.; Acourene, S.; Kh Khalid, A.; Bacha, A.; Tama, M.; Taleb, B. Optimization of Bakery Yeast Production Cultivated on Musts of Dates. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2007, 3, 964–971. [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete-Bolaños, J.L.; Téllez-Martínez, M.G.; Miranda-López, R.; Jiménez-Islas, H. An Experimental Strategy Validated to Design Cost-Effective Culture Media Based on Response Surface Methodology. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017, 47, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Roh, K.; Lee, J.H. CFD-Based Determination of Optimal Design and Operating Conditions of a Fermentation Reactor Using Bayesian Optimization. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2025, 122, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedele, C.; Kennedy, C.; Huckleberry, S.; Hinson, W.; Hamrock, R. The Effects of Agitation on Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Yeast Carbon Dioxide Output. J. Introd. Biol. Investig. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Hernández, F.R. Evaluación del proceso de propagación y fermentación de dos cepas de levadura Saccharromyces cerevisiae y su influencia en el perfil sensorial del alcohol obtenido en la primera destilación, en DUSA. Rev. Científica Agroind. Soc. Y Ambiente 2023, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Wang, G.; Lin, J.; Wang, Y.; Chu, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, S. Advances and Practices of Bioprocess Scale-Up. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2016, 152, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).