Abstract

This study investigated the influence of different winemaking processes, particularly fermentation type and must clarification, on the formation of biogenic amines (BA) in Sauvignon wine. The experiment investigated seven methods of vinification combining spontaneous and controlled alcoholic and malolactic fermentation. The concentrations of six biogenic amines (histamine, tyramine, tryptamine, phenylethylamine, putrescine, and cadaverine) were determined using a HILIC-LC-MS/MS. Statistical evaluation confirmed the significant effect of alcoholic and malolactic fermentation, maturation stage, and must processing on the overall amine profile of the wine (p < 0.001). The total BA content in all the variants was low and well below values considered to pose a health risk. Histamine and tryptamine were only detected in trace amounts (<0.1 mg/L), whereas putrescine and tyramine exhibited the greatest variability. Higher concentrations were recorded in variants that underwent malolactic fermentation, particularly in combination with clarified must. In contrast, whole-mash fermentation produced the lowest BA concentrations, possibly due to factors associated with extended skin and seed contact. These findings indicate that the choice of fermentation strategy significantly affects the formation of biogenic amines in wine.

1. Introduction

Biogenic amines (BAs) are nitrogen-containing compounds primarily formed by the microbial decarboxylation of amino acids, typically during fermentation processes [1,2]. At elevated concentrations, they can induce adverse physiological effects such as headaches, hypertension, allergic reactions, flushing, and gastrointestinal disturbances [3,4,5].

In winemaking, BAs are unavoidable metabolic by-products of microbial activity, and their formation is strongly influenced by the process parameters applied during fermentation. Critical stages in the production of BA include alcoholic fermentation (AF) and malolactic fermentation (MLF), during which compounds such as histamine, tyramine, putrescine, and cadaverine may be generated. While AF, carried out mainly by Saccharomyces cerevisiae, makes a minimal contribution to BA formation, the principal source of these compounds is MLF, which is typically carried out, according to literature, by lactic acid bacteria (LAB) such as Oenococcus oeni, Lactobacillus, or Pediococcus spp. [6,7,8]. A minor proportion of BAs may also originate from the grape material itself [9,10].

Modern enology distinguishes two fundamental fermentation strategies: spontaneous fermentation, which relies on the native microbiota of the grapes and the winery environment, and controlled fermentation that employs selected commercial microbial cultures [11,12]. From a process standpoint, these approaches represent two contrasting extremes in terms of process control and reproducibility. Spontaneous fermentation often promotes broader microbial diversity which enhances terroir expression and wine complexity [13], but it may also involve LAB strains with a high capacity for BA formation. Controlled fermentation, particularly when using O. oeni as a starter for MLF, ensure a greater degree of control over timing, microbial activity, and fermentation kinetics, thereby reducing the risk of BA accumulation and improving the consistency of the wine [14,15]. Among LAB species, O. oeni is most commonly used due to its tolerance to ethanol and low pH, as well as its relatively low decarboxylase activity. In contrast, spontaneous fermentation is described in the literature as favouring species such as L. brevis and Pediococcus spp., which exhibit markedly greater histamine and tyramine production [16,17].

Although BAs are often discussed in the context of consumer health [4], numerous studies confirm that under well-controlled winemaking conditions its concentration remains within safe limits. Compared to other fermented foods such as cheese, cured meat or fish, wine generally contains substantially lower levels of BAs [17,18]. Their occurrence is therefore more indicative of process management than of a quality defect.

The formation of BAs is affected by multiple oenological parameters, including yeast strain selection, the initiation and course of MLF, and fermentation temperature [19]. Additionally, factors such as pH regulation, sulphur dioxide management, and nutrient supplementation can either suppress or stimulate the growth of BA-producing microorganisms [11,20,21].

This study aims to assess the effect of different fermentation strategies on the formation of biogenic amines in Sauvignon wine, specifically the type of alcoholic and malolactic fermentation and must clarification. The dynamics of individual amines throughout the vinification process were monitored using HILIC–LC–MS/MS (Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry) to elucidate how specific process decisions influence BA accumulation during winemaking.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

The experiment was conducted using Vitis vinifera L. cv. Sauvignon grapes harvested in 2024 from the “Na Valtické” vineyard in the wine-growing area around the village of Lednice (Mikulov sub-region, Moravia wine region, Czech Republic). The initial must have a sugar content of 21.1 °NM, titratable acidity of 6.42 g/L, pH 3.45, and yeast-assimilable nitrogen (YAN) of 189 mg/L.

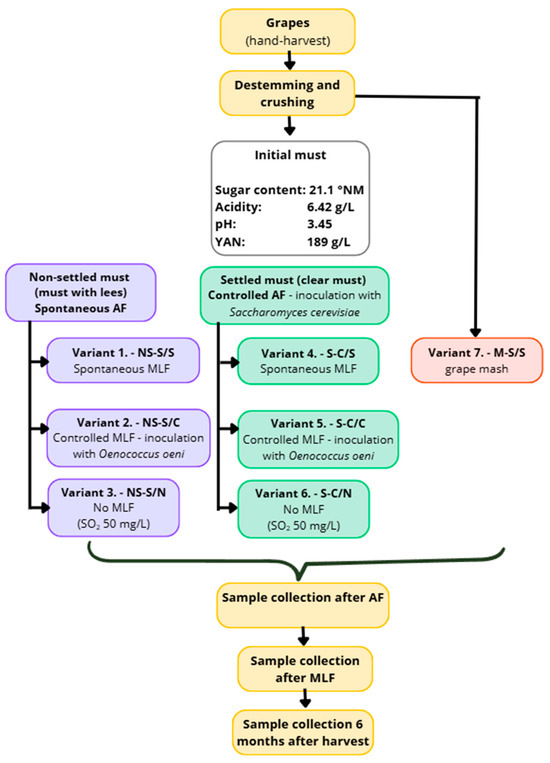

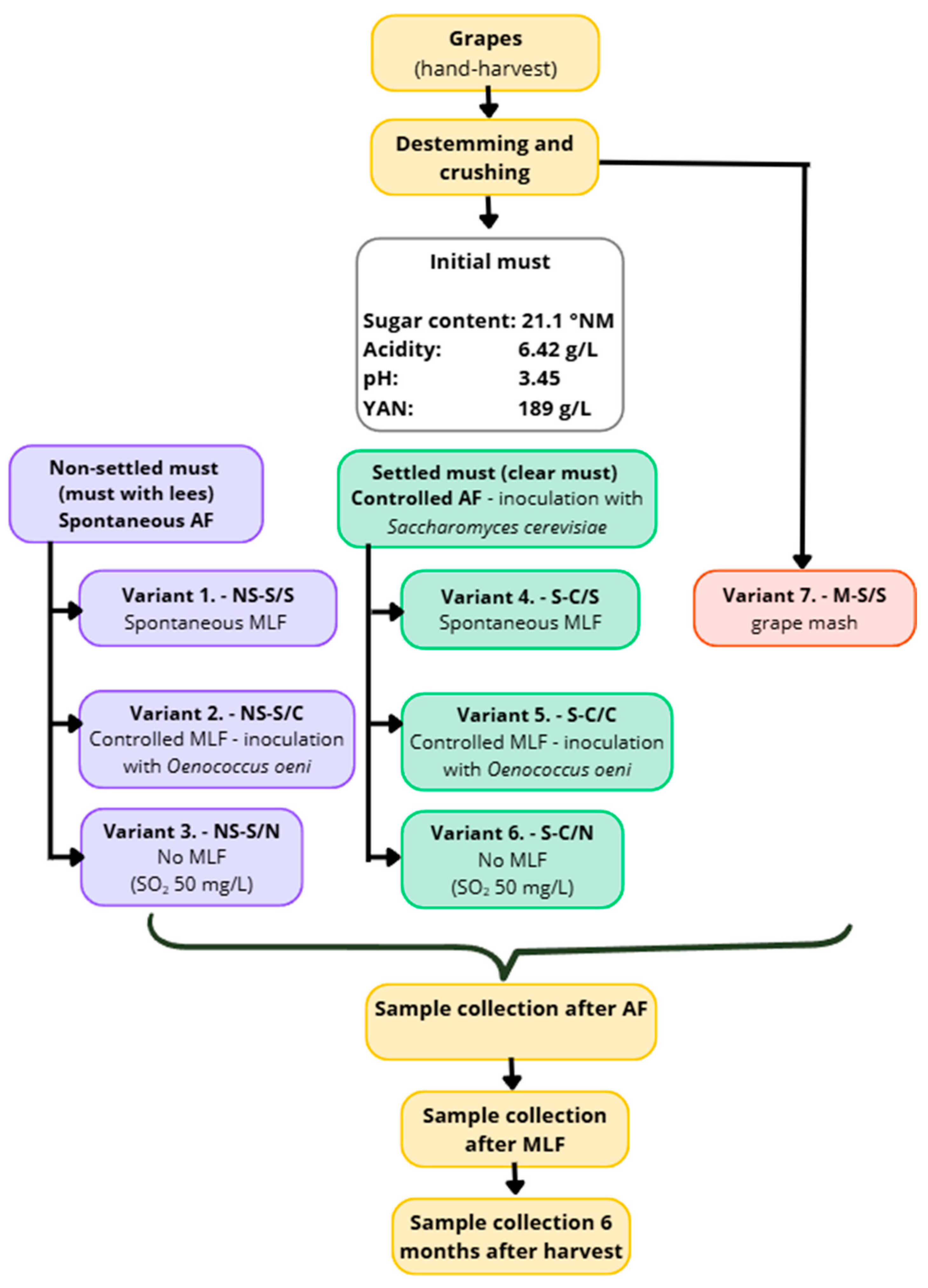

2.2. Experimental Design and Vinification

The Sauvignon grapes were harvested by hand and processed immediately after collection. After destemming and crushing, a portion of the mash was separated prior to pressing and used for variant V7 (M-S/S), which underwent spontaneous alcoholic and malolactic fermentation on the whole mash (skins and seeds). The remaining mash was then pressed using a pneumatic press.

Immediately after pressing, a portion of the fresh, unclarified must was divided into three batches corresponding to variants V1–V3: NS-S/S (V1), NS-S/C (V2), and NS-S/N (V3). These variants were produced from unclarified must and all underwent spontaneous alcoholic fermentation. In V1 (NS-S/S), alcoholic fermentation was followed by spontaneous MLF; in V2 (NS-S/C), controlled MLF was performed; and in V3 (NS-S/N), no MLF occurred.

The rest of the pressed must was left to settle by static sedimentation for 24 h at 6–8 °C. On the following day, the clarified must was carefully racked and divided into variants V4–V6: S-C/S (V4), S-C/C (V5), and S-C/N (V6). These variants were produced from clarified must and underwent controlled alcoholic fermentation (inoculation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae—IOC Révélation Terroir, Institut Œnologique de Champagne, France). Malolactic fermentation proceeded according to the experimental design: V4 (S-C/S) underwent spontaneous MLF, V5 (S-C/C) controlled MLF, and V6 (S-C/N) no MLF.

All seven experimental variants (V1–V7) were prepared in triplicate, with each replicate fermented in a 30 L glass fermentation vessel (see Figure 1 for the schematic overview of the experimental design).

After the completion of alcoholic fermentation, samples were taken from all variants. Variants intended for controlled MLF (V2 and V5) were inoculated with a commercial strain of Oenococcus oeni (Viniflora Oenos 2.0, Chr. Hansen A/S, Denmark). In the variants without MLF (V3 and V6), sulphur dioxide was added at 50 mg/L. After fermentation, the wines were racked off the heavy lees. Samples were collected at the following stages: must before fermentation, after alcoholic fermentation, after malolactic fermentation, and six months after harvest.

2.3. Determination of Biogenic Amines

The following biogenic amines were analysed: histamine, phenylethylamine, tyramine, tryptamine, putrescine, cadaverine, and isoamylamine (not detected). Quantification was performed using a high-pressure binary gradient HPLC system (ExionLC, AB Sciex, Concord, ON, Canada) coupled to a 3200QTrap™ LC–MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry) detector (AB Sciex, Concord, ON, Canada). Ionization was carried out with a Turbo V™ interface equipped with an Electrospray Ionization (ESI) source operating in positive ion mode. Data acquisition and processing was performed using Analyst 1.5.1 software (AB Sciex).

Prior to analysis, the wine samples were centrifuged (3000× g, 6 min) and prepared as follows: 20 µL of 1,6-diaminohexane solution (0.2 mM, internal standard) and 930 µL of diluting buffer (3 mM ammonium formate in 80% acetonitrile, pH adjusted to 3.0 with formic acid) were added to 50 µL of sample. The resulting mixture was vortexed, again centrifuged under the same conditions, and directly injected into the chromatographic system.

Chromatographic separation was performed on a Poroshell 120 HILIC-Z column (2.7 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) maintained at 40 °C. The injection volume was 5 µL, and the mobile phase flow rate was 0.5 mL/min. The mobile phase consisted of 3 mM ammonium formate (pH 3.0) as solvent A and 3 mM ammonium formate in 90% acetonitrile (pH 3.0) as solvent B. Gradient elution was performed under the following conditions: 0.0 min—100% B; 3.0 min—70% B; 7.0 min—0% B; 7.1 min—100% B.

Figure 1.

Experimental process.

Figure 1.

Experimental process.

The ESI source was operated in positive ion mode at 3600 V. The gas flow parameters were set as follows: curtain gas 30 psig, nebulizer gas (GS1) 40 psig, turbo gas (GS2) 60 psig, and a desolvation temperature of 720 °C. The 3200QTrap™ mass spectrometer was operated in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode with optimized transitions for each analyte (summarized in Table 1). The total chromatographic run time was 10 min, and MS data were acquired within the 0.3–8.0 min interval.

Table 1.

Detector settings.

The LC–MS/MS procedure applied in this study follows the validated HILIC–MS/MS method described by Kumšta et al. [22]. Seven-point calibration curves (10–1000 µg/L; 20–2000 µg/L for spermine) were prepared for all analytes, showing excellent linearity (R2 = 0.97–0.997). The limits of detection (LOD) ranged from 0.5 to 5 µg/L and the limits of quantification (LOQ) from 1.5 to 15 µg/L. Matrix effects were assessed by comparing aqueous and matrix-matched calibration curves, resulting in signal suppression/enhancement values between 74% and 107%. Repeatability and reproducibility were consistent with the validated method. An internal standard (1,6-diaminohexane) was added to all samples and standards. Each analytical sequence included solvent blanks, calibration-verification standards, and QC samples to ensure instrument stability and exclude drift throughout the run.

2.4. Determination of Basic Wine Parameters

The following parameters were determined: total titratable acidity, malic acid, lactic acid, reducing sugars, pH, and ethanol content.

An Alpha FTIR analyser (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) was used to determine pH, ethanol, reducing sugars, and total titratable acidity.

The concentrations of individual organic acids were determined through high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a Shimadzu LC-10A system (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Prior to analysis, the wine samples were centrifuged (3000× g, 6 min) and diluted tenfold with demineralized water. A 20 µL aliquot of the diluted sample was injected into a chromatographic system equipped with an SCL-10Avp system controller, two LC-10ADvp pumps, a CTO-10ACvp column thermostat with a Rheodyne manual injection valve, and an SPD-M10Avp diode array detector. The system operation and data acquisition was managed using LCsolution software (Version 1.25 SP2, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

Chromatographic separation was performed on a Watrex Polymer IEX H form column (10 µm, 250 × 8 mm + 10 × 8 mm) maintained at 60 °C. The mobile phase consisted of 3.0 mM H2SO4 at a flow rate of 0.75 mL/min, with isocratic elution. Detection was carried out at 210 nm, and the quantification of the analytes was based on external calibration.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical data processing was carried out using STATISTICA 14 software (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate the effect of individual factors, including must clarification, alcoholic fermentation, malolactic fermentation, and vinification stage, on the concentration of individual biogenic amines.

To assess the combined influence and interactions of these factors, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was carried out. The evaluation was based on a Wilks’ lambda (λ) test and the corresponding F-statistics. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Vinification strategy was not included as a separate factor in the ANOVA/MANOVA because it represents a composite of the experimental parameters (must clarification, type of alcoholic fermentation, and MLF type). Including it as an additional factor would therefore introduce collinearity into the model. Moreover, must clarification and AF type were inherently linked in the design (unclarified must → spontaneous AF; clarified must → controlled AF). Consequently, the factor “AF/Must” reflects a composite process parameter rather than two independent effects, and this was taken into account when interpreting the statistical results. Detailed ANOVA and MANOVA results for all biogenic amines are provided in Appendix A (Table A1, Table A2, Table A3, Table A4, Table A5, Table A6 and Table A7).

To identify which vinification variants differed significantly at the six-month stage, a post hoc comparison was performed using the Tukey HSD test (α = 0.05). Mean values were assigned to homogeneous groups (labelled a, b, c, …), and these groupings are shown directly in the figures.

3. Results and Discussion

The results section presents the concentrations of six biogenic amines in seven experimental variants of Sauvignon wine, each representing a different approach to vinification. Particular emphasis is placed on the impact of fermentation management (spontaneous vs. inoculated alcoholic and malolactic fermentation) and must clarification on the dynamics of amine formation. The results are interpreted in the context of the current literature to identify the process and microbiological factors responsible for differences in the biogenic amine profile.

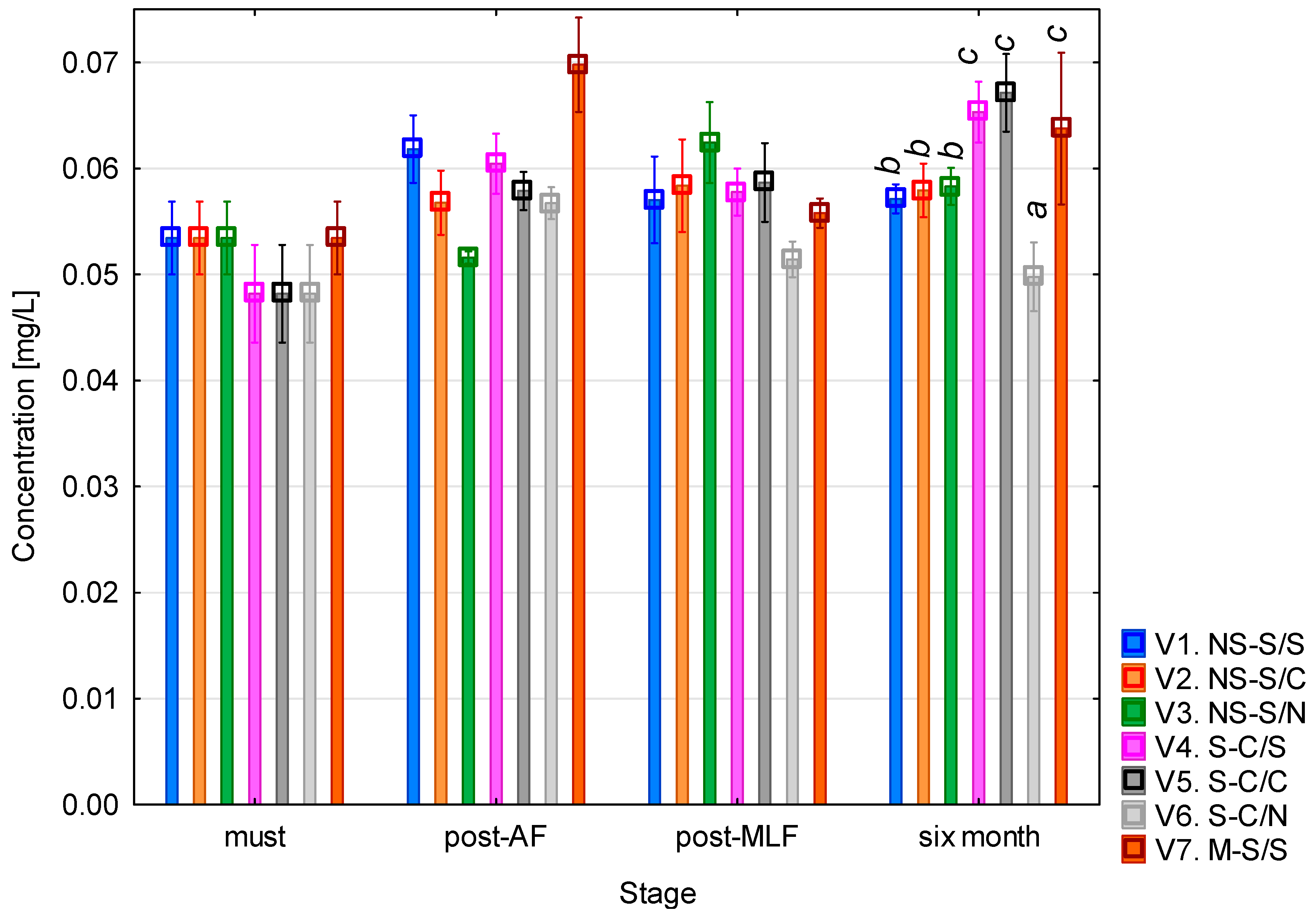

3.1. Histamine Content During Vinification

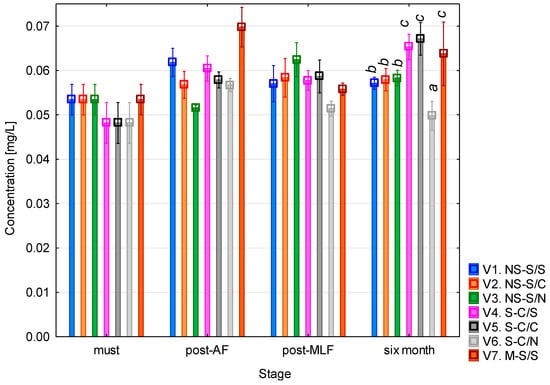

The histamine content (Figure 2) in the variants was consistently low throughout the vinification process. In the must, the concentration ranged between 0.05 and 0.06 mg/L across all variants. Following alcoholic fermentation, a slight increase was observed, particularly in variant 7, where the concentration approached 0.07 mg/L. After malolactic fermentation, all concentrations were comparable, with no significant differences among variants. After six months of maturation, variant 6 (clarified must + no MLF) had the lowest histamine content, similar to that measured in the must.

Figure 2.

Histamine concentration. NS—non-settled must; S—settled must; M—mash fermentation; S—spontaneous fermentation (AF or MLF); C—controlled fermentation (AF or MLF); N—no malolactic fermentation (SO2 50 mg/L); mean values at the six-month stage were divided into homogeneous groups (letters a, b, c) using Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05); the vertical lines represent a 0.95 confidence interval.

The one-way ANOVA revealed that histamine concentration was significantly affected by the MLF method used and vinification stage (both p < 0.01; see Table A1). The largest effect was associated with the vinification stage (F = 22.52; p < 0.001), confirming changes in histamine levels during fermentation and wine maturation. The interaction between must processing (AF) and MLF was also significant (p < 0.05), indicating that the way in which the must was handled influenced histamine formation. Other factors and interactions were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

These results are in agreement with previous studies reporting that white wines generally contain very low concentrations of histamine, typically <1 mg/L, whereas higher levels are more characteristic of red wines. Esposito et al. [23] reported a median histamine concentration of 0.55 mg/L in white wines and 2.68 mg/L in red wines. García-Marino et al. [24] observed histamine levels that ranged from 0.1 to 4.2 mg/L in commercial wines from Castilla y León. Nalazek-Rudnicka and Wasik [25] found histamine levels that ranged from several tens of µg/L to a few hundred (0.01–0.125 mg/L), reporting a maximum of 3.7 mg/L for Central European white wines which is consistent with the present findings, while red wines exceeded 15 mg/L. U Zhu et al. [26] observed that white wines generally contained low histamine levels (average ~2 mg/L, median 0.18 mg/L), although some Czech samples reached values of greater than 10 mg/L, demonstrating a considerable degree of variability depending on origin.

Overall, the histamine concentrations observed in this study were not high enough to be problematic, and they were not substantially affected by malolactic fermentation or must clarification. The measured values of 0.05 to 0.07 mg/L are well below the recommended limits of 2–10 mg/L, which are considered potentially harmful to sensitive individuals and are used in some countries as internal quality thresholds [15,27]. From a toxicological standpoint, the consumption of up to 4 mg of histamine (approximately one glass of sparkling wine) may trigger a reaction in sensitive individuals [23]. but this is still significantly higher than the concentrations found in this study. Furthermore, the EFSA states that no adverse effects have been observed in healthy individuals after the consumption of up to 50 mg of histamine in a single exposure [15]; again, this is several orders of magnitude higher than the levels detected here.

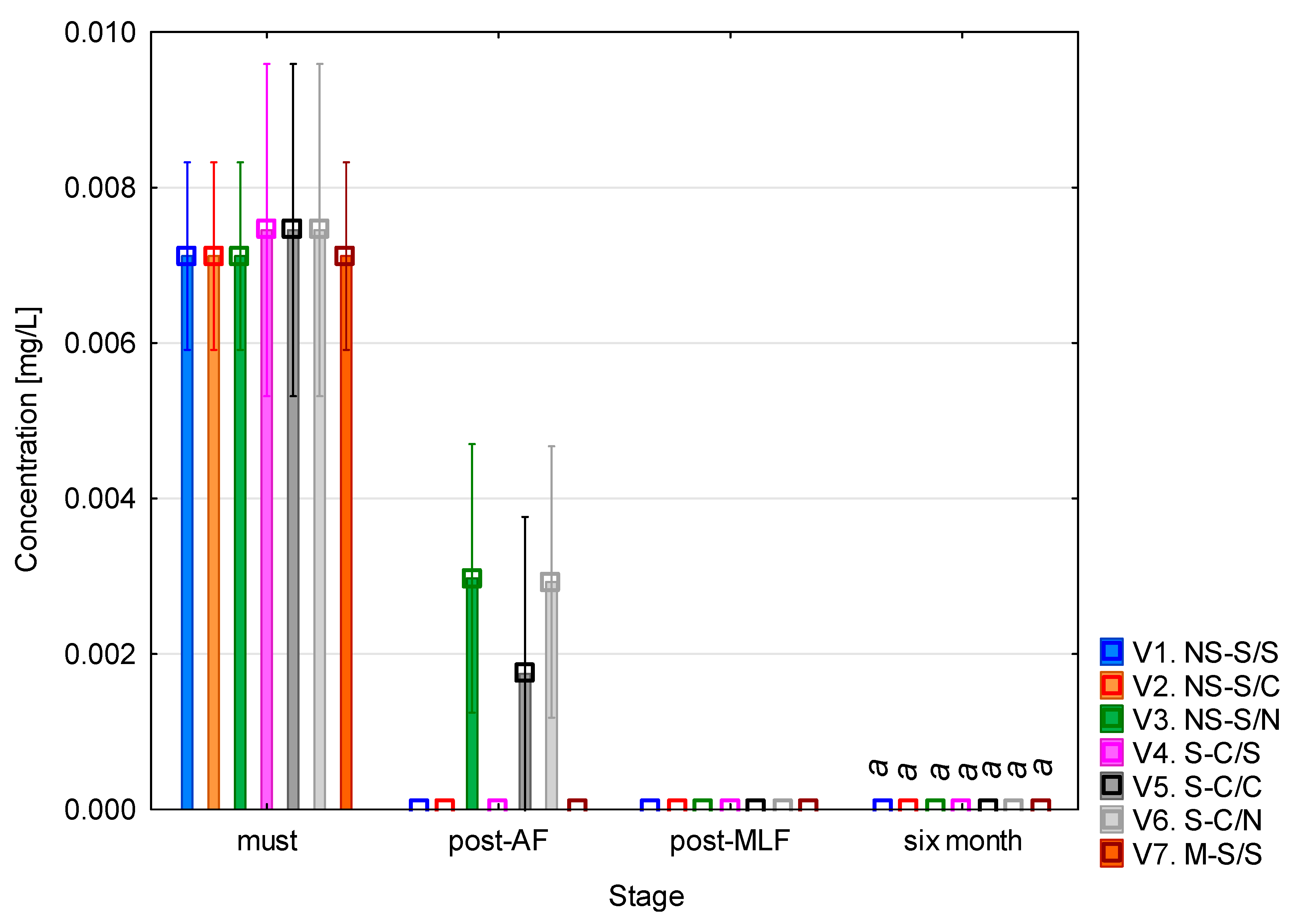

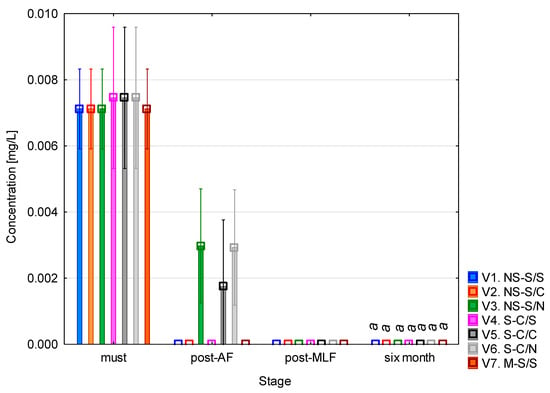

3.2. Tryptamine Content During Vinification

The highest concentration of tryptamine (Figure 3) was found at the beginning of the experiment, in the must samples, where it ranged between 0.007 and 0.008 mg/L across all variants. These values are, however, very low. Following alcoholic fermentation, a sharp decrease in concentration was observed, with values dropping to 0.001–0.003 mg/L or below the limit of detection. After malolactic fermentation and six months of aging, tryptamine concentrations were practically undetectable, with no observable differences between variants. The ANOVA confirmed (see Table A2) that tryptamine concentrations did not differ between the vinification variants. However, a significant effect of vinification stage was observed, reflecting the uniform decline of tryptamine over time. These results indicate that tryptamine formation was not influenced by must clarification, alcoholic fermentation type, or malolactic fermentation but was affected mainly by the progression of fermentation and maturation.

Figure 3.

Tryptamine concentration. NS—non-settled must; S—settled must; M—mash fermentation; S—spontaneous fermentation (AF or MLF); C—controlled fermentation (AF or MLF); N—no malolactic fermentation (SO2 50 mg/L); mean values at the six-month stage were divided into homogeneous groups (letter a) using Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05); vertical lines represent 0.95 confidence intervals.

The data suggest that tryptamine is present in trace amounts in grape must but rapidly degrades during fermentation, resulting in negligible levels in finished wines. This finding corresponds to the results of Míšková et al. [28] who did not detect tryptamine in any of 232 Central European wine samples, confirming that it only occurs as a trace or is absent in white wines. García-Marino et al. [24] also detected tryptamine in wines from Castilla y León, but only at levels close to the lower detection limit. Similarly, Mir-Cerdà et al. [21] reported that it was not present in the sparkling wines analysed which supports its minimal importance in comparison to other biogenic amines. According to Han et al. [29], tryptamine occurs at low concentrations (tenths or units of mg/L) in commercial wines on the Chinese market and, together with putrescine and tyramine, is considered a potential quality indicator rather than a toxicologically relevant compound.

From a toxicological perspective, tryptamine belongs to the group of indole amines, which serve as precursors in the biosynthesis of serotonin and melatonin. At elevated concentrations, it may have vasodilatory effects and contribute to headaches or migraines, particularly when combined with other biogenic amines such as tyramine or histamine [23].

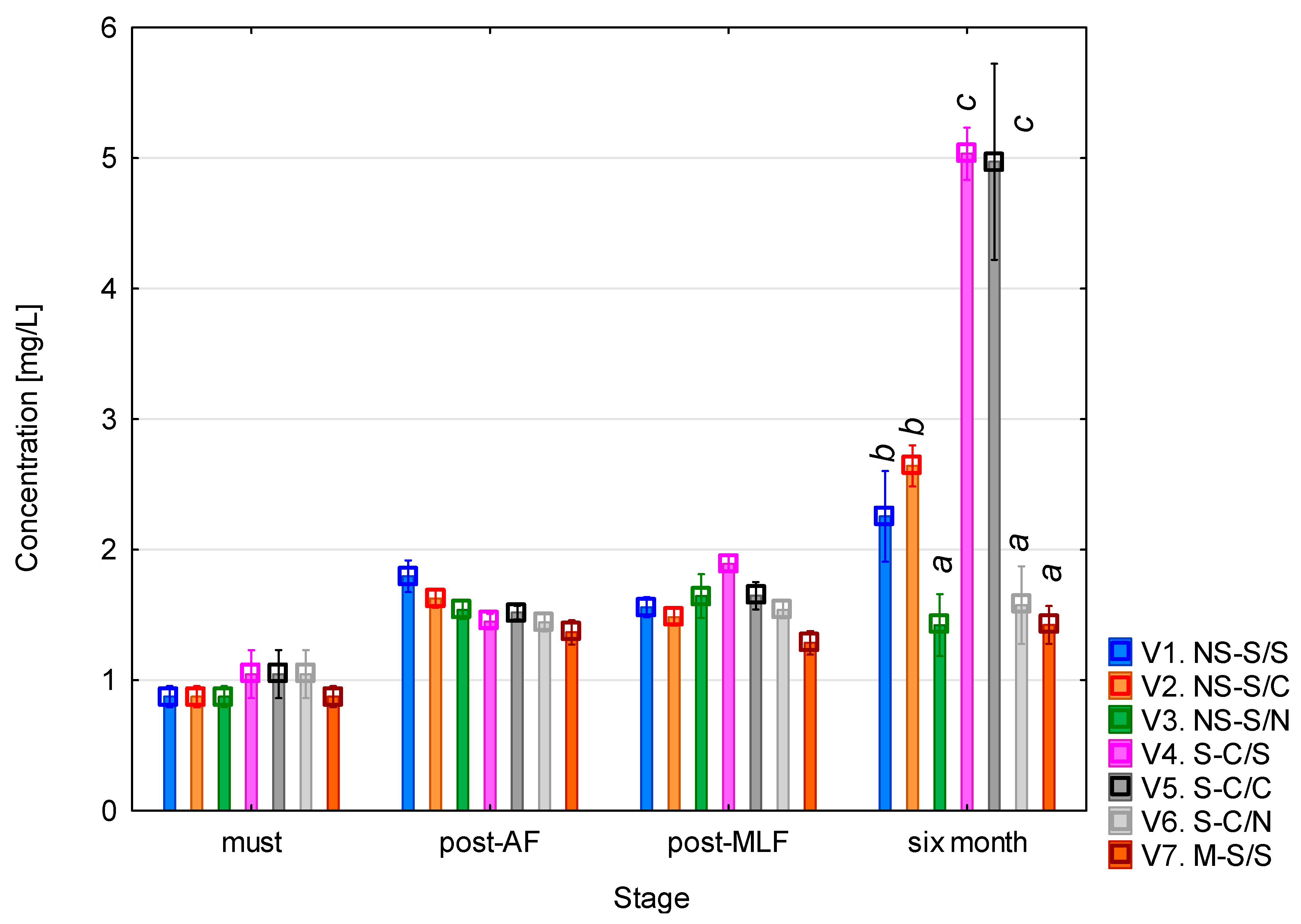

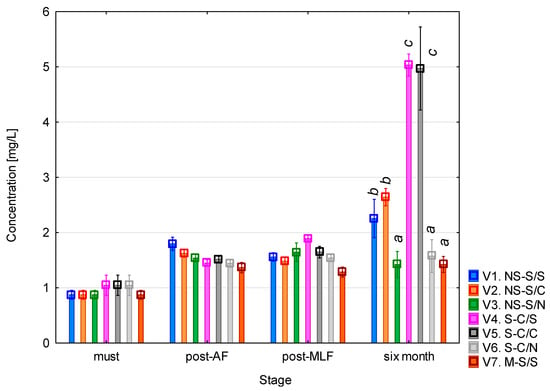

3.3. Putrescine Content During Vinification

The putrescine content (Figure 4) showed a clear trend of gradual increase throughout the monitoring period. The concentration found in the must was around 1 mg/L. After alcoholic fermentation, a slight increase was observed in most of the variants, with slightly higher values in those with unclarified must. Following malolactic fermentation, the concentrations did not change significantly, with the lowest level recorded in variant 7 (whole-mash fermentation). The mash-fermented variant involves multiple simultaneous changes and should therefore be interpreted cautiously. Several studies have reported that the higher polyphenol content resulting from contact with skins and seeds may contribute to lower putrescine levels, as polyphenolic compounds such as piceatannol and glycosylated stilbenes have been shown to partially inhibit the fermentative activity of bacteria responsible for the synthesis of biogenic amines [30]. This interpretation aligns with previously reported inhibitory effects of phenolic compounds on LAB and can be considered a plausible contributing factor. The most pronounced differences were observed after six months of aging, when a significant increase occurred, particularly in variants 4 and 5 (clarified must + malolactic fermentation), where the concentrations reached approximately 5 mg/L. A noticeable increase was also seen in variants 1 and 2 (unclarified must + malolactic fermentation). In variants where malolactic fermentation did not occur, the concentrations remained relatively stable. The ANOVA revealed that all the monitored factors had a statistically significant effect on putrescine levels (p < 0.001, see Table A3). The strongest effect was associated with the vinification stage (F = 594.66; p < 0.001), confirming the dominant influence of the fermentation and post-fermentation phases on changes in concentration. All the interaction terms were also statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating that putrescine formation was governed by a combination of technical and biological processes, particularly the concurrence of alcoholic and malolactic fermentation.

Figure 4.

Putrescine concentration. NS—non-settled must; S—settled must; M—mash fermentation; S—spontaneous fermentation (AF or MLF); C—controlled fermentation (AF or MLF); N—no malolactic fermentation (SO2 50 mg/L); mean values at the six-month stage were divided into homogeneous groups (letters a, b, c) using Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05); the vertical lines represent a 0.95 confidence interval.

The results further showed that the final putrescine concentrations were higher in variants with clarified must than in those with unclarified must. This finding is somewhat unexpected, as the opposite would typically be expected due to the reduction in the microbial load during clarification. However, several enological studies have demonstrated that pre-fermentation clarification, especially static sedimentation, significantly modifies the nitrogen composition and amino acid profile of musts and the resulting wines [31,32,33]

Since putrescine is formed through decarboxylation of arginine or ornithine, changes in the availability of these precursors can influence its formation. This is consistent with studies showing strong correlations between free amino acids and biogenic amine levels in wines [34,35].

Furthermore, clarification may alter microbial population dynamics; sedimentation reduces overall microbial diversity and can selectively retain groups with different metabolic potential in the clarified fraction, as shown for other wine microorganisms [36,37,38]. Together, these literature-supported mechanisms offer a plausible explanation for the elevated putrescine levels in clarified variants. Differences could also be related to the progression of malolactic fermentation itself, which may proceed differently in clarified musts compared to unclarified musts [39].

After six months of maturation, the putrescine concentrations of the Sauvignon samples ranged from 1.5 to 5 mg/L, with the lowest levels found in variants 3, 6, and 7 (approximately 1.5 mg/L), intermediate levels in variants 1 and 2 (approximately 2.5 mg/L), and the highest in variants 4 and 5 (approximately 5 mg/L). These results correspond well with the published data: [23] Esposito et al. reported a median of 1.55 mg/L for white wines (95th percentile 3.96 mg/L), while red wines reached a median of 7.30 mg/L. García-Marino et al. [24] found concentrations that ranged from 5.55 to 11.09 mg/L in wines from Castilla y León, and Míšková et al. [28] reported exceptionally high levels of up to 30.4 mg/L in white wines. Overall, the results of this study fall within the normal range for white wines, with variants 4 and 5 approaching the upper limit of the typical range reported in the literature.

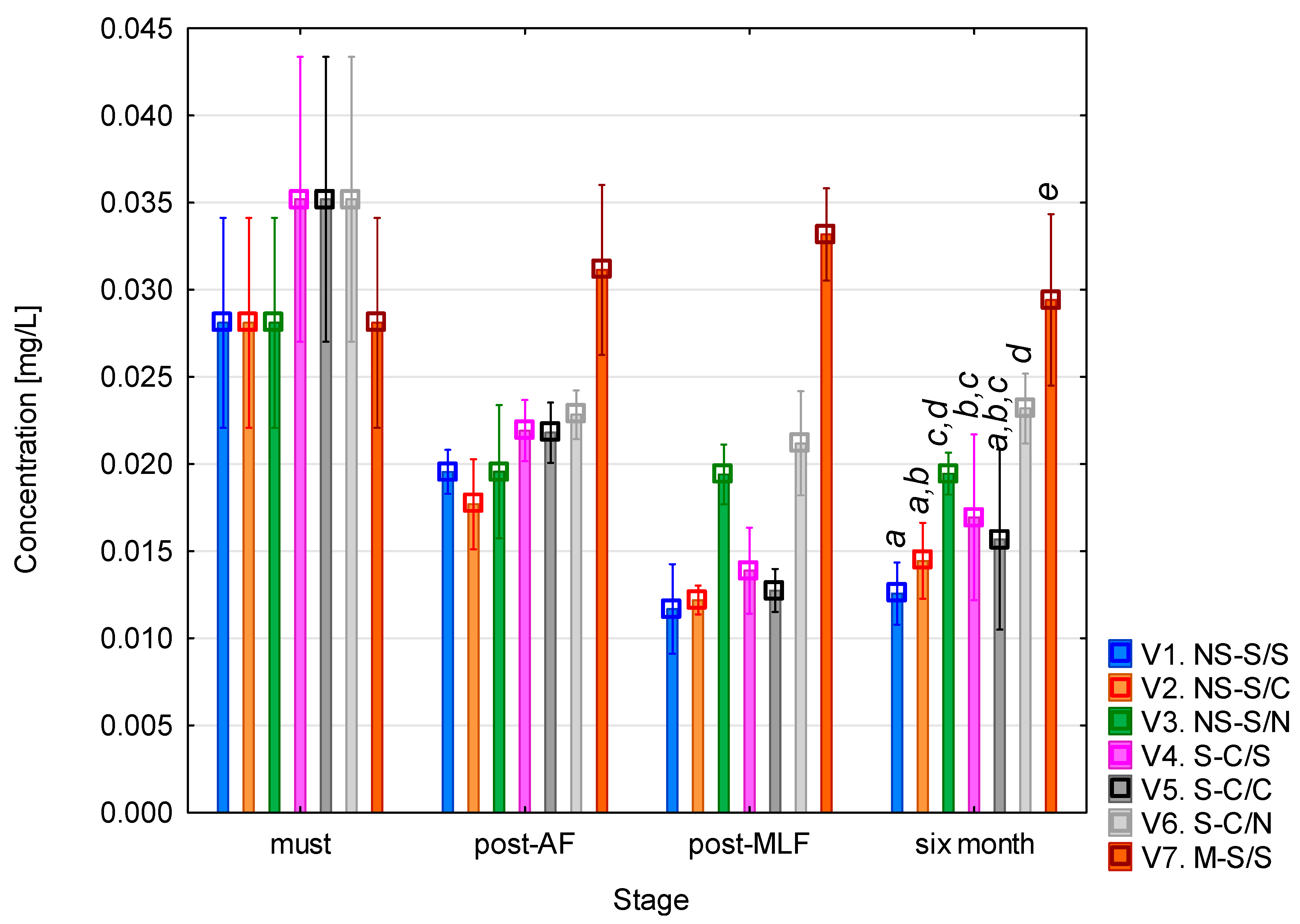

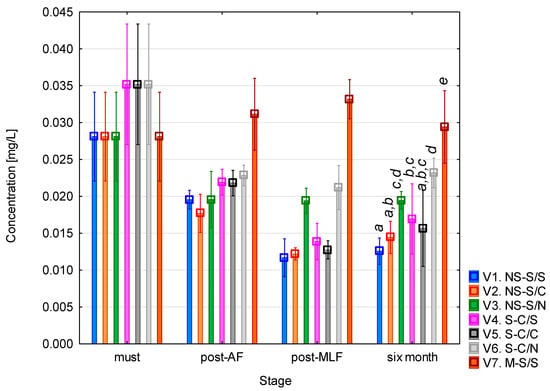

3.4. Phenylethylamine Content During Vinification

The phenylethylamine (PEA) concentration (Figure 5) was highest in the must. After alcoholic fermentation, PEA levels decreased in all variants except variant 7 (whole-mash fermentation), which showed a slight increase. Following malolactic fermentation, the concentration further declined in variants that underwent MLF (1, 2, 4, and 5). Comparable values were observed in the variants without MLF, where sulphur dioxide was added, as well as in variant 7. After six months of maturation, no significant changes in PEA concentration were observed. The highest final concentration was recorded in variant 7, consistent with reports that wines fermented on skins and seeds typically exhibit higher PEA levels due to the enhanced extraction of free amino acids, particularly phenylalanine as the direct biochemical precursor of PEA [40,41]. This variant should be interpreted cautiously due to multiple simultaneous changes. According to the one-way ANOVA results (see Table A4), the vinification stage had a statistically significant effect on PEA concentration (F = 44.18; p < 0.001), while racking (AF) showed a weaker but still significant influence (F = 4.10; p = 0.045).

Figure 5.

Phenylethylamine concentration. NS—non-settled must; S—settled must; M—mash fermentation; S—spontaneous fermentation (AF or MLF); C—controlled fermentation (AF or MLF); N—no malolactic fermentation (SO2 50 mg/L); mean values at the six-month stage were divided into homogeneous groups (letters a, b, c, d, e) using Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05); vertical lines represent 0.95 confidence intervals.

The low PEA concentrations observed in this study are consistent with the findings of Kovačević Ganić et al. [42], who reported levels ranging from 0.05 to 0.8 mg/L in Sauvignon wines. PEA toxicity has generally been associated with concentrations of around 3 mg/L, confirming that the values obtained here are well below the threshold of potential concern for sensitive individuals.

The slightly higher PEA levels seen in wines treated with sulphur dioxide and without MLF can be explained by the inhibitory effect of SO2 on lactic acid bacteria. Sulphur dioxide suppresses their growth and enzymatic activity, thereby preventing both the formation and potential degradation of biogenic amines. Conversely, during MLF, which is generally described in the literature as being driven mainly by LAB such as O. oeni, both the formation and subsequent metabolism of some amines, including PEA, may occur. This has been confirmed by several studies that monitored BA dynamics before and after MLF [43]. In wines where MLF was carried out in a controlled manner, the total BA content, including PEA, either remained stable or decreased, whereas in sulfurized wines without MLF, the concentrations tended to remain unchanged or slightly increase [24,44].

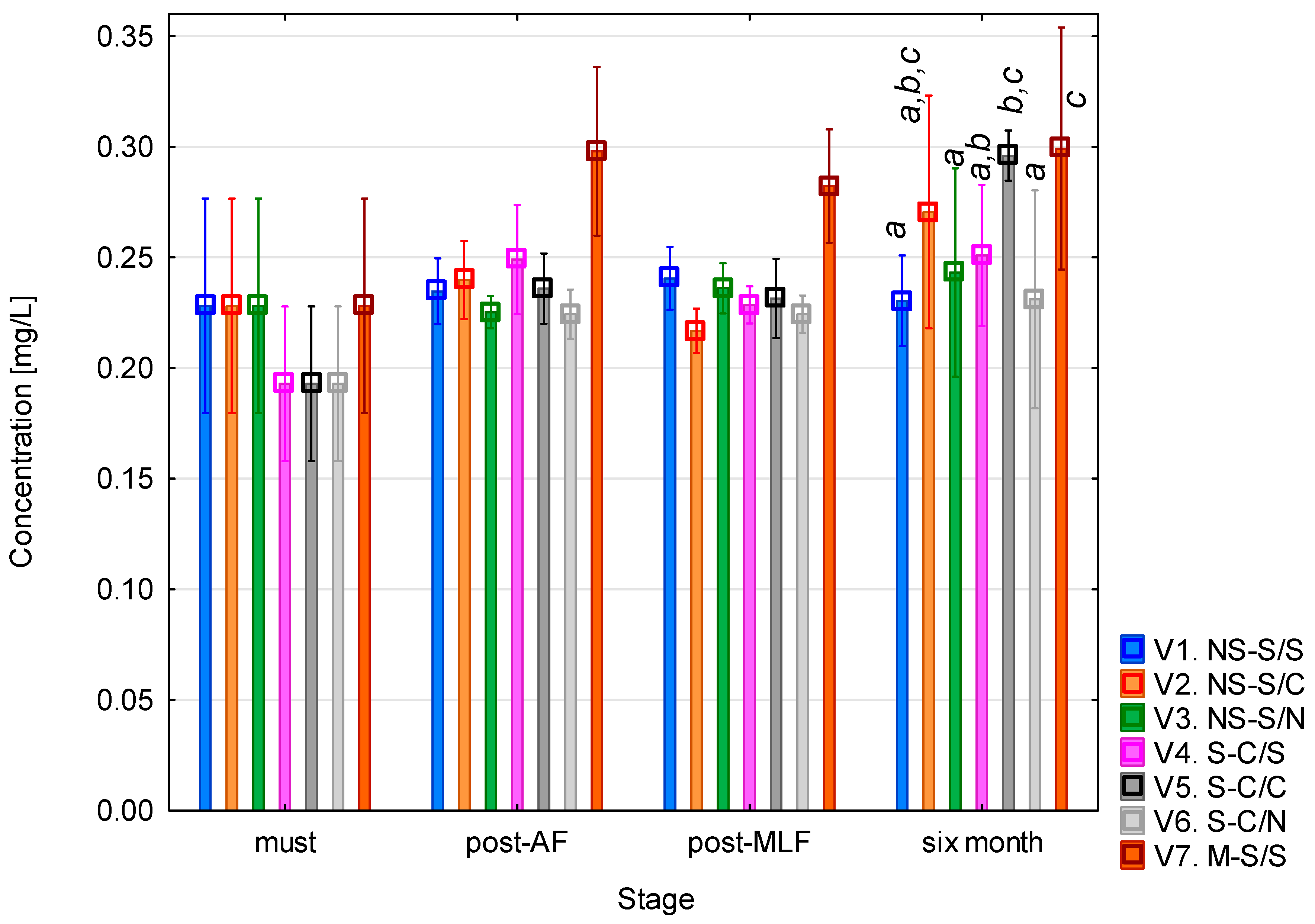

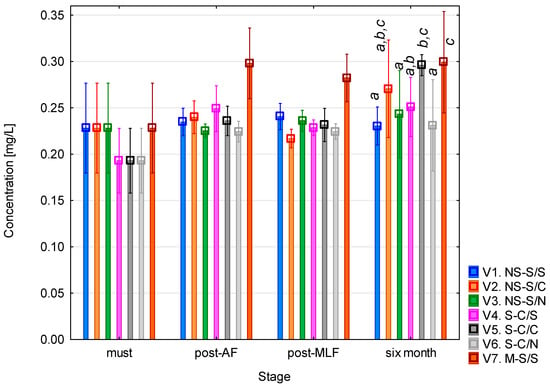

3.5. Cadaverine Content During Vinification

Cadaverine concentrations (Figure 6) were low across all the experimental variants. In the musts, the levels were in the range of 0.20 and 0.23 mg/L. After alcoholic fermentation, a slight increase was observed in most variants, most notably variant 7. No clear differences were detected between controlled and spontaneous fermentations. Similarly, malolactic fermentation did not cause substantial changes in cadaverine levels, although after maturation, variants 2, 5, and 7 reached their highest concentrations. The elevated cadaverine content in wines with controlled MLF (variants 2 and 5) compared to spontaneous MLF is likely related, according to literature, to the metabolic potential of the commercial O. oeni inoculum used, which have been reported to vary in their decarboxylase potential. The gradual increase in cadaverine over time is consistent with previous findings that describe cadaverine as an amine accumulating slowly during post-MLF maturation due to bacterial activity rather than during the primary fermentation stage [24,43]. The highest cadaverine concentration was observed in wine fermented on the mash (variant 7), where extended contact with grape skins and seeds may promote the release of lysine, the biochemical precursor of cadaverine, which could contribute to its accumulation [40,42]. Statistical analysis confirmed that all factors had a significant effect (p < 0.05, see Table A5), with the most pronounced influence associated with the vinification stage (F = 26.20; p < 0.001). Overall, the results indicate that cadaverine may serve as a sensitive indicator of microbial activity and fermentation dynamics in wine.

Figure 6.

Cadaverine concentration. NS—non-settled must; S—settled must; M—mash fermentation; S—spontaneous fermentation (AF or MLF); C—controlled fermentation (AF or MLF); N—no malolactic fermentation (SO2 50 mg/L); mean values at the six-month stage were divided into homogeneous groups (letters a, b, c) using Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05); the vertical lines represent a 0.95 confidence interval.

The final measured concentrations ranged from 0.23 to 0.30 mg/L, which is in good agreement with the data reported by Míšková et al. [28], who recorded a maximum cadaverine concentration of 0.7 mg/L, with most samples below 0.5 mg/L. A review by Moreira et al. [45] also confirmed that cadaverine is among the more frequently detected diamines in wine, although its concentrations generally remain low, consistent with the findings of this study.

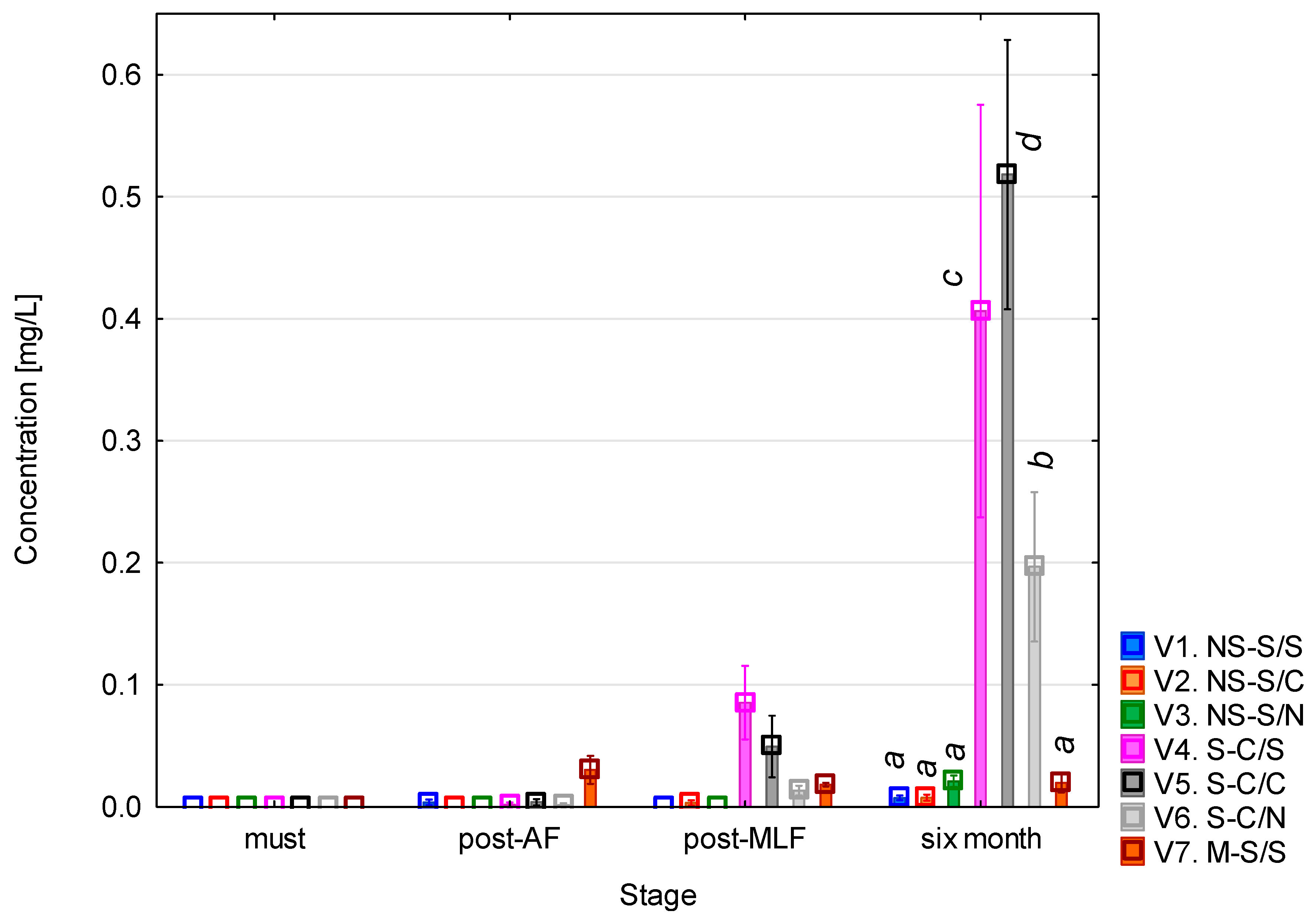

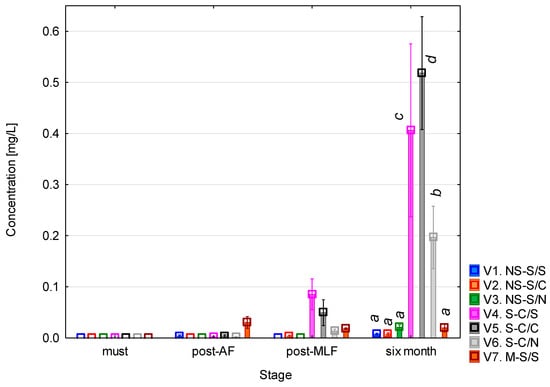

3.6. Tyramine Content During Vinification

Tyramine (Figure 7) was practically undetectable in the musts, and after alcoholic fermentation only trace concentrations (<0.01 mg/L) were found. Following malolactic fermentation, a slight increase (up to approximately 0.05–0.1 mg/L) occurred in variants 4 and 5. The most pronounced differences appeared after six months of maturation, when tyramine levels rose significantly in variants 4 and 5 (clarified must + MLF) and variant 6 (clarified must + controlled MLF). In the remaining variants, concentrations remained very low (<0.05 mg/L). This pattern indicates that tyramine formation only occurs to a limited extent during fermentation but can accumulate under specific process conditions, in particular when must clarification is combined with malolactic fermentation. These findings were confirmed by the one-way ANOVA (see Table A6), which showed statistical significance for all the evaluated factors (p < 0.001). Again, the most pronounced effect was associated with the vinification phase (F = 494.28; p < 0.001), reflecting the dynamic changes that occur during fermentation and subsequent maturation. All the interaction terms were also significant (p < 0.001), demonstrating the complex nature of tyramine formation, which depends on the combined influence of biological and process parameters.

Figure 7.

Tyramine concentration. NS—non-settled must; S—settled must; M—mash fermentation; S—spontaneous fermentation (AF or MLF); C—controlled fermentation (AF or MLF); N—no malolactic fermentation (SO2 50 mg/L); mean values at the six-month stage were divided into homogeneous groups (letters a, b, c, d) using Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05); vertical lines represent 0.95 confidence intervals.

The low concentrations of tyramine immediately after MLF and their increase during maturation can be hypothetically explained by changes in the microbial dynamics and precursor availability. During prolonged aging, the literature indicates that residual lactic acid bacteria may metabolize tyrosine released from yeast autolysis, leading to secondary tyramine formation. The increase was more pronounced in clarified musts, a pattern that has been associated in other work with the dominance of fewer bacterial strains with active decarboxylase systems and an altered profile of free amino acids. The highest values were observed in variant 5 (controlled MLF), which exceeded those in the spontaneous MLF variant (variant 4). This may be related to the behaviour of commercial O. oeni strains, which are reported in the literature to differ in decarboxylase activity compared to spontaneous LAB populations or lead to a more efficient fermentation process. A notable increase in tyramine was also recorded in variant 6 (clarified must + SO2), possibly connected to the reactivation of SO2-tolerant bacterial strains once the free sulphur dioxide content decreased during maturation [5,46,47,48].

3.7. Multivariate Analysis of the Influence of Process and Biological Factors on the Formation of Biogenic Amines

To comprehensively assess the overall influence of fermentation dynamics and process factors on the formation of biogenic amines, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted. Two models were tested: the AF–MLF–Stage model, representing the biological progression of fermentation phases, and the Must–MLF–Stage model, representing the way the must was processed. Both models produced identical statistical outcomes due to the close correspondence between the type of alcoholic fermentation and the racking/clarification step, as these two parameters reflect the same underlying process. For this reason, vinification strategy was not included as an independent statistical factor. Instead, its underlying components were evaluated separately. In this context, the AF/Must factor should be interpreted as a composite process parameter, because must clarification and alcoholic fermentation type were inherently linked in the experimental design; therefore, its effect represents the combined influence of both steps rather than fully independent variables.

The MANOVA revealed (see Table A7) that all the main factors and their interactions had a statistically significant effect on the overall biogenic amine profile (p < 0.001). The most pronounced effect was associated with the vinification stage (Wilks’ λ = 0.014; F = 169.7), indicating that changes in the composition of biogenic amines is most dynamic during fermentation and post-fermentation maturation. Significant effects were also observed for alcoholic and malolactic fermentation (Wilks’ λ = 0.159; F = 122.4 for AF; Wilks’ λ = 0.316; F = 18.0 for MLF), both of which are key biological processes involved in the formation and transformation of amines.

These results indicate that biogenic amine formation in wine is a multifactorial process governed by the combined influence of microbial metabolism and processing during vinification. It should also be acknowledged that minor malolactic activity may have been initiated before the formally defined MLF stage, which could contribute to some of the early changes observed in the biogenic amine profile. These patterns should be interpreted within the context of a single-cultivar, single-vintage experiment and may differ in wines with higher phenolic content or under different technological conditions.

3.8. Analytical Parameters of Wines During Vinification

Monitoring of the basic analytical parameters of the wines (see Table 2) confirmed the occurrence of the expected changes during the individual fermentation phases. The most pronounced variations were observed in the content of malic and lactic acids, which clearly reflected the progress of malolactic fermentation. During MLF, a gradual degradation of the malic acid was accompanied by a simultaneous increase in lactic acid, particularly evident in the variants where MLF occurred spontaneously or was induced in a controlled manner. The fastest progression was observed in variant 7 (whole-mash fermentation), where the decrease in malic acid and increase in lactic acid appeared earliest. These results suggest that in some variants a limited onset of malolactic activity may have occurred already during the late alcoholic fermentation phase, which is consistent with the behavior of lactic acid bacteria under low-pH conditions. These results indicate that different processes conditions applied in the experiment, such as skin and seed contact, bacterial inoculation, or sulphur-dioxide addition, likely contributed to the observed differences in fermentation dynamics and the final wine composition.

Table 2.

Basic analytical parameters of wines.

4. Conclusions

The results of this study confirmed that the concentrations of biogenic amines (BAs) in Sauvignon wines remained well below the threshold associated with potential health risks and were consistent with typical values reported for white wines. Among the analysed amines, histamine and tryptamine were only found in very low, trace concentrations, whereas putrescine and tyramine showed greater variability depending on the individual stage of fermentation.

The ANOVA and MANOVA statistical analyses demonstrated that the formation of biogenic amines is significantly influenced by both the biological processes used for fermentation and the processing of the must, with malolactic fermentation and the fermentation stage showing statistically significant effects (p < 0.001).

The combination of malolactic fermentation and clarified must resulted in higher concentrations of putrescine and tyramine, while whole-mash fermentation tended to suppress their formation. These findings indicate that the careful selection of process parameters can serve as an effective tool for controlling biogenic amine formation during vinification, thereby contributing to the production of wines with a stable and low BA profile. Because the experiment involved one cultivar, vineyard and vintage, the results may not be directly applicable to other wine styles or regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: K.K. and J.S.; methodology: K.K.; validation: K.K.; formal analysis: M.K.; investigation: K.K.; resources: K.K.; data curation: M.K.; writing—original draft preparation: K.K.; writing—review and editing: K.K.; supervision: J.S. and M.B.; project administra-tion: J.S.; funding acquisition: J.S. and M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project “The effect of winemaking technologies on the content of biogenic amines in wine.” IGA-ZF/2025-SI1-009.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AF | Alcoholic fermentation |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BA/BAs | Biogenic amine(s) |

| ESI | Electrospray Ionization |

| HILIC | Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| MANOVA | Multivariate Analysis of Variance |

| MLF | Malolactic fermentation |

| PEA | Phenylethylamine |

| SO2 | Sulphur Dioxide |

| Variant Abbreviations | |

| V1 | NS-S/S |

| V2 | NS-S/C |

| V3 | NS-S/N |

| V4 | S-C/S |

| V5 | S-C/C |

| V6 | S-C/N |

| V7 | M-S/S |

| NS | non-settled must |

| S | settled must |

| M | mash fermentation |

| S | spontaneous fermentation (AF or MLF) |

| C | controlled fermentation (AF or MLF) |

| N | no malolactic fermentation (SO2 50 mg/L) |

Appendix A

This appendix contains detailed statistical results supporting the findings described in the main text. Table A1, Table A2, Table A3, Table A4, Table A5 and Table A6 summarize one-way ANOVA results for individual biogenic amines (histamine, tryptamine, putrescine, phenylethylamine, cadaverine, and tyramine), while Table A7 presents the results of multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) evaluating the combined effects on the overall biogenic amine profile.

Abbreviations used in Table A1, Table A2, Table A3, Table A4, Table A5 and Table A6: AF (Must)—type of alcoholic fermentation, corresponding to the method of must processing (clarified vs. unclarified must);

MLF—type of malolactic fermentation; Stage—sampling phase (must, post-AF, post-MLF, 6 months);

SS—Sum of Squares; df—degrees of freedom; MS—Mean Square; F—F-value; p—significance level (statistically significant result are shown in bold p < 0.05).

Table A1.

Result of one-way ANOVA for histamine.

Table A1.

Result of one-way ANOVA for histamine.

| Effect | SS | df | MS | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF (Must) | 0.000050 | 1 | 0.000050 | 2.32 | 0.130119 |

| MLF | 0.000298 | 2 | 0.000149 | 6.86 | 0.001428 |

| Stage | 0.000979 | 2 | 0.000489 | 22.52 | 0.000000 |

| AF× MLF | 0.000167 | 2 | 0.000084 | 3.85 | 0.023550 |

| AF × Stage | 0.000125 | 2 | 0.000063 | 2.88 | 0.059322 |

| MLF × Stage | 0.000181 | 4 | 0.000045 | 2.08 | 0.086495 |

| AF × MLF × Stage | 0.000175 | 4 | 0.000044 | 2.01 | 0.095502 |

Table A2.

Result of one-way ANOVA for tryptamine.

Table A2.

Result of one-way ANOVA for tryptamine.

| Effect | SS | df | MS | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF (Must) | 0.000001 | 1 | 0.000001 | 0.5296 | 0.467969 |

| MLF | 0.000004 | 2 | 0.000002 | 1.0749 | 0.344049 |

| Stage | 0.000786 | 2 | 0.000393 | 240.7684 | 0.000000 |

| AF × MLF | 0.000000 | 2 | 0.000000 | 0.1158 | 0.890771 |

| AF × Stage | 0.000000 | 2 | 0.000000 | 0.1144 | 0.891972 |

| MLF × Stage | 0.000011 | 4 | 0.000003 | 1.7399 | 0.144402 |

| AF × MLF × Stage | 0.000001 | 4 | 0.000000 | 0.1878 | 0.944466 |

Table A3.

Result of one-way ANOVA for putrescine.

Table A3.

Result of one-way ANOVA for putrescine.

| Effect | SS | df | MS | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF (Must) | 8.6509 | 1 | 8.6509 | 245.533 | 0.000000 |

| MLF | 8.4358 | 2 | 4.2179 | 119.715 | 0.000000 |

| Stage | 41.9032 | 2 | 20.9516 | 594.660 | 0.000000 |

| AF × MLF | 2.7614 | 2 | 1.3807 | 39.188 | 0.000000 |

| AF × Stage | 15.5303 | 2 | 7.7651 | 220.394 | 0.000000 |

| MLF × Stage | 16.8893 | 4 | 4.2223 | 119.840 | 0.000000 |

| AF × MLF × Stage | 8.1589 | 4 | 2.0397 | 57.893 | 0.000000 |

Table A4.

Result of one-way ANOVA for phenylethylamine.

Table A4.

Result of one-way ANOVA for phenylethylamine.

| Effect | SS | df | MS | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF (Must) | 0.000130 | 1 | 0.000130 | 4.098 | 0.044787 |

| MLF | 0.000177 | 2 | 0.000089 | 2.802 | 0.064000 |

| Stage | 0.002793 | 2 | 0.001397 | 44.179 | 0.000000 |

| AF × MLF | 0.000100 | 2 | 0.000050 | 1.581 | 0.209317 |

| AF × Stage | 0.000204 | 2 | 0.000102 | 3.227 | 0.042549 |

| MLF × Stage | 0.000081 | 4 | 0.000020 | 0.644 | 0.631673 |

| AF × MLF × Stage | 0.000051 | 4 | 0.000013 | 0.402 | 0.806798 |

Table A5.

Result of one-way ANOVA for cadaverine.

Table A5.

Result of one-way ANOVA for cadaverine.

| Effect | SS | df | MS | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF (Must) | 0.004060 | 1 | 0.004060 | 6.976 | 0.009175 |

| MLF | 0.004048 | 2 | 0.002024 | 3.477 | 0.033512 |

| Stage | 0.023509 | 2 | 0.011755 | 20.196 | 0.000000 |

| AF × MLF | 0.001723 | 2 | 0.000862 | 1.480 | 0.230975 |

| AF × Stage | 0.003855 | 2 | 0.001928 | 3.312 | 0.039241 |

| MLF × Stage | 0.007952 | 4 | 0.001988 | 3.416 | 0.010601 |

| AF × MLF × Stage | 0.000989 | 4 | 0.000247 | 0.425 | 0.790457 |

Table A6.

Result of one-way ANOVA for tyramine.

Table A6.

Result of one-way ANOVA for tyramine.

| Effect | SS | df | MS | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF (Must) | 0.329304 | 1 | 0.329304 | 575.0809 | 0.000000 |

| MLF | 0.041403 | 2 | 0.020701 | 36.1520 | 0.000000 |

| Stage | 0.566077 | 2 | 0.283038 | 494.2845 | 0.000000 |

| AF × MLF | 0.045461 | 2 | 0.022730 | 39.6953 | 0.000000 |

| AF × Stage | 0.501137 | 2 | 0.250569 | 437.5807 | 0.000000 |

| MLF × Stage | 0.057181 | 4 | 0.014295 | 24.9647 | 0.000000 |

| AF × MLF × Stage | 0.069028 | 4 | 0.017257 | 30.1366 | 0.000000 |

Table A7.

Result of MANOVA analysis for the combined biogenic amine profile.

Table A7.

Result of MANOVA analysis for the combined biogenic amine profile.

| Effect | df Effect | df Error | Wilks’ Λ | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF (Must) | 6 | 139.000 | 0.159 | 122.427 | <0.001 |

| MLF | 12 | 278.000 | 0.316 | 18.017 | <0.001 |

| Stage | 12 | 278.000 | 0.014 | 169.651 | <0.001 |

| AF × MLF | 12 | 278.000 | 0.461 | 10.964 | <0.001 |

| AF × Stage | 12 | 278.000 | 0.089 | 54.446 | <0.001 |

| MLF × Stage | 24 | 486.123 | 0.169 | 13.446 | <0.001 |

| AF × MLF × Stage | 24 | 486.123 | 0.251 | 9.842 | <0.001 |

df effect—degrees of freedom for effect; df error—degrees of freedom for error; Wilks’ Λ—Wilks’ lambda (multivariate test statistic); F—F-value; p-value—significance level.

References

- Barbieri, F.; Montanari, C.; Gardini, F.; Tabanelli, G. Biogenic amine production by lactic acid bacteria: A review. Foods 2019, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feddern, V.; Mazzuco, H.; Fonseca, F.; De Lima, G. A review on biogenic amines in food and feed: Toxicological aspects, impact on health and control measures. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2019, 59, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durak-Dados, A.; Michalski, M.; Osek, J. Histamine and other biogenic amines in food. J. Vet. Res. 2020, 64, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omer, A.K.; Mohammed, R.R.; Ameen, P.S.M.; Abas, Z.A.; Ekici, K. Presence of biogenic amines in food and their public health implications: A review. J. Food Prot. 2021, 84, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Restuccia, D.; Loizzo, M.R.; Spizzirri, U.G. Accumulation of biogenic amines in wine: Role of alcoholic and malolactic fermentation. Fermentation 2018, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doeun, D.; Davaatseren, M.; Chung, M.-S. Biogenic amines in foods. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 1463–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regecová, I.; Semjon, B.; Jevinová, P.; Očenáš, P.; Výrostková, J.; Šuľáková, L.; Nosková, E.; Marcinčák, S.; Bartkovský, M. Detection of microbiota during the fermentation process of wine in relation to the biogenic amine content. Foods 2022, 11, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnodim, L.; Odu, N.; Ogbonna, D.; Kiin-Kabari, D. Screening of yeasts other than Saccharomyces for amino acid decarboxylation. Biotechnol. J. Int. 2021, 25, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokhoijav, E.; Guba, A.; Vadadokhau, U.; Tőzsér, J.; Győri, Z.; Kalló, G.; Csősz, É. Comparative analysis of amino acid and biogenic amine compositions of fermented grape beverages. Metabolites 2023, 13, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incesu, M.; Karakus, S.; Seyed Hajizadeh, H.; Ates, F.; Turan, M.; Skalicky, M.; Kaya, O. Changes in biogenic amines of two table grapes (cv. Bronx Seedless and Italia) during berry development and ripening. Plants 2022, 11, 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatenco, G.O.; Taran, N.; Adajuc, V. The role of non-Saccharomyces microorganisms and their technological importance in winemaking: A review. J. Agroaliment. Process. Technol. 2024, 4, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J.M.; Alperstein, L.; Walker, M.E.; Zhang, J.; Jiranek, V. Modern yeast development: Finding the balance between tradition and innovation in contemporary winemaking. FEMS Yeast Res. 2023, 23, foac049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, B.L.; Eisenhofer, R.; Bastian, S.E.; Kidd, S.P. Monitoring the viable grapevine microbiome to enhance the quality of wild wines. Microbiol. Aust. 2023, 44, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastard, A.; Coelho, C.; Briandet, R.; Canette, A.; Gougeon, R.; Alexandre, H.; Guzzo, J.; Weidmann, S. Effect of biofilm formation by Oenococcus oeni on malolactic fermentation and the release of aromatic compounds in wine. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantini, A.; Vaudano, E.; Pulcini, L.; Carafa, T.; Garcia-Moruno, E. An overview on biogenic amines in wine. Beverages 2019, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabanelli, G. Biogenic amines and food quality: Emerging challenges and public health concerns. Foods 2020, 9, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özogul, Y.; Özogul, F. Biogenic amines formation, toxicity, regulations in food. In Biogenic Amines in Food: Analysis, Occurrence and Toxicity; Saad, B., Tofalo, R., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Herrero, A.M. Impact of biogenic amines on food quality and safety. Foods 2019, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo, C.; Bordiga, M.; Pérez-Álvarez, E.; Travaglia, F.; Arlorio, M.; Salinas, M.; Coïsson, J.D.; Garde-Cerdán, T. The impacts of temperature, alcoholic degree and amino acids content on biogenic amines and their precursor amino acids content in red wine. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wen, X.; Wen, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, L.; Wei, X. Evaluation of the biogenic amines formation and degradation abilities of Lactobacillus curvatus from Chinese bacon. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir-Cerdà, A.; Izquierdo-Llopart, A.; Saurina, J.; Sentellas, S. Oenological processes and product qualities in the elaboration of sparkling wines determine the biogenic amine content. Fermentation 2021, 7, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumšta, M.; Helmová, T.; Štůsková, K.; Baroň, M.; Průšová, B.; Sochor, J. HPLC/HILIC determination of biogenic amines in wines produced by different winemaking technologies. Acta Aliment. 2023, 52, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, F.; Montuori, P.; Schettino, M.; Velotto, S.; Stasi, T.; Romano, R.; Cirillo, T. Level of biogenic amines in red and white wines, dietary exposure, and histamine-mediated symptoms upon wine ingestion. Molecules 2019, 24, 3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Marino, M.; Trigueros, Á.; Escribano-Bailon, T. Influence of oenological practices on the formation of biogenic amines in quality red wines. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2010, 23, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalazek-Rudnicka, K.; Wasik, A. Development and validation of an LC–MS/MS method for the determination of biogenic amines in wines and beers. Monatshefte Für Chem.-Chem. Mon. 2017, 148, 1685–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Song, X.; Jiang, Y.; Yao, J.; Li, Z.; Dai, F.; Wang, Q. Determination of Biogenic Amines in Wine from Chinese Markets Using Ion Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Foods 2023, 12, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osete-Alcaraz, L.; Gómez-Plaza, E.; Pérez-Porras, P.; Oliva-Ortiz, J.; Cámara, M.Á.; Jurado-Fuentes, R.; Bautista-Ortín, A.B. Plant fibres. A solution to reduce pesticides, OTA and histamine in red and white wines. Food Chem. 2025, 486, 144662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Míšková, Z.; Lorencová, E.; Salek, R.N.; Koláčková, T.; Trávníková, L.; Rejdlová, A.; Buňková, L.; Buňka, F. Occurrence of biogenic amines in wines from the central european region (Zone B) and evaluation of their safety. Foods 2023, 12, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, B.; Han, X.; Deng, H.; Wu, T.; Li, C.; Zhan, J.; Huang, W.; You, Y. Profiling the occurrence of biogenic amines in wine from Chinese market and during fermentation using an improved chromatography method. Food Control 2022, 136, 108859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassoni, A.; Tango, N.; Ferri, M. Polyphenol and biogenic amine profiles of Albana and Lambrusco grape berries and wines obtained following different agricultural and oenological practices. Food Nutr. Sci. 2014, 5, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burin, V.M.; Gomes, T.M.; Caliari, V.; Rosier, J.P.; Luiz, M.T.B. Establishment of influence the nitrogen content in musts and volatile profile of white wines associated to chemometric tools. Microchem. J. 2015, 122, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayestaran, B.M.; Ancin, M.C.; Garcia, A.M.; Gonzalez, A.; Garrido, J.J. Influence of prefermentation clarification on nitrogenous contents of musts and wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995, 43, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancín, C.; Ayestarán, B.; Garrido, J. Sedimentation clarification of Garnacha musts. Consumption of amino acids during fermentation and aging. Food Res. Int. 1996, 29, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, A.; Du Toit, W.; Du Toit, M. Biogenic amines in wine: Understanding the headache. South Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2008, 29, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macoviciuc, S.; Niculaua, M.; Nechita, C.-B.; Cioroiu, B.-I.; Cotea, V.V. The Correlation between Amino Acids and Biogenic Amines in Wines without Added Sulfur Dioxide. Fermentation 2024, 10, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berbegal, C.; Spano, G.; Tristezza, M.; Grieco, F.; Capozzi, V. Microbial resources and innovation in the wine production sector. South Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2017, 38, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisson, L.F. Stuck and sluggish fermentations. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1999, 50, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, A.; Malfeito-Ferreira, M.; Loureiro, V. The microbial ecology of wine grape berries. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 153, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, A.P.; Leitão, M.C.; San Romão, M.V. Biogenic amines in wines: Influence of oenological factors. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, A.Y.; du Toit, W.J.; Stander, M.; du Toit, M. Evaluating the influence of maceration practices on biogenic amine formation in wine. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 53, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, A.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Martín-Álvarez, P.J.; Bartolomé, B. Comparative study of the inhibitory effects of wine polyphenols on the growth of enological lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 145, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević Ganić, K.; Gracin, L.; Komes, D.; Ćurko, N.; Lovrić, T. Changes of the content of biogenic amines during winemaking of Sauvignon wines. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 1, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Pinilla, O.; Guadalupe, Z.; Hernández, Z.; Ayestarán, B. Amino acids and biogenic amines in red varietal wines: The role of grape variety, malolactic fermentation and vintage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2013, 237, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramithiotis, S.; Stasinou, V.; Tzamourani, A.; Kotseridis, Y.; Dimopoulou, M. Malolactic fermentation—Theoretical advances and practical considerations. Fermentation 2022, 8, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.; Milheiro, J.; Filipe-Ribeiro, L.; Cosme, F.; Nunes, F.M. Exploring factors influencing the levels of biogenic amines in wine and microbiological strategies for controlling their occurrence in winemaking. Food Res. Int. 2024, 190, 114558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płotka-Wasylka, J.; Simeonov, V.; Namieśnik, J. Evaluation of the impact of storage conditions on the biogenic amines profile in opened wine bottles. Molecules 2018, 23, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerbu, M.I.; Colibaba, C.L.; Popîrdă, A.; Toader, A.-M.; Niță, R.-G.; Zamfir, C.-I.; Niculaua, M.; Cioroiu, B.-I.; Cotea, V.V. Increasing amino acids and biogenic amines content of white and rosé wines during ageing on lees. BIO Web Conf. 2023, 68, 02014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, V.; Tufariello, M.; De Simone, N.; Fragasso, M.; Grieco, F. Biodiversity of oenological lactic acid bacteria: Species-and strain-dependent plus/minus effects on wine quality and safety. Fermentation 2021, 7, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).