Caproate Production from Yellow Water Fermentation: The Decisive Roles of Electron Donors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Substrate

2.2. Inoculum

2.3. Experimental Setup and Fermentation Procedure

2.4. Culture Medium Composition

2.5. Analytical Methods

2.6. Microbial Community Analysis

2.7. Analysis of Metal Ions

2.8. Caproate Production Yield

3. Results and Discussion

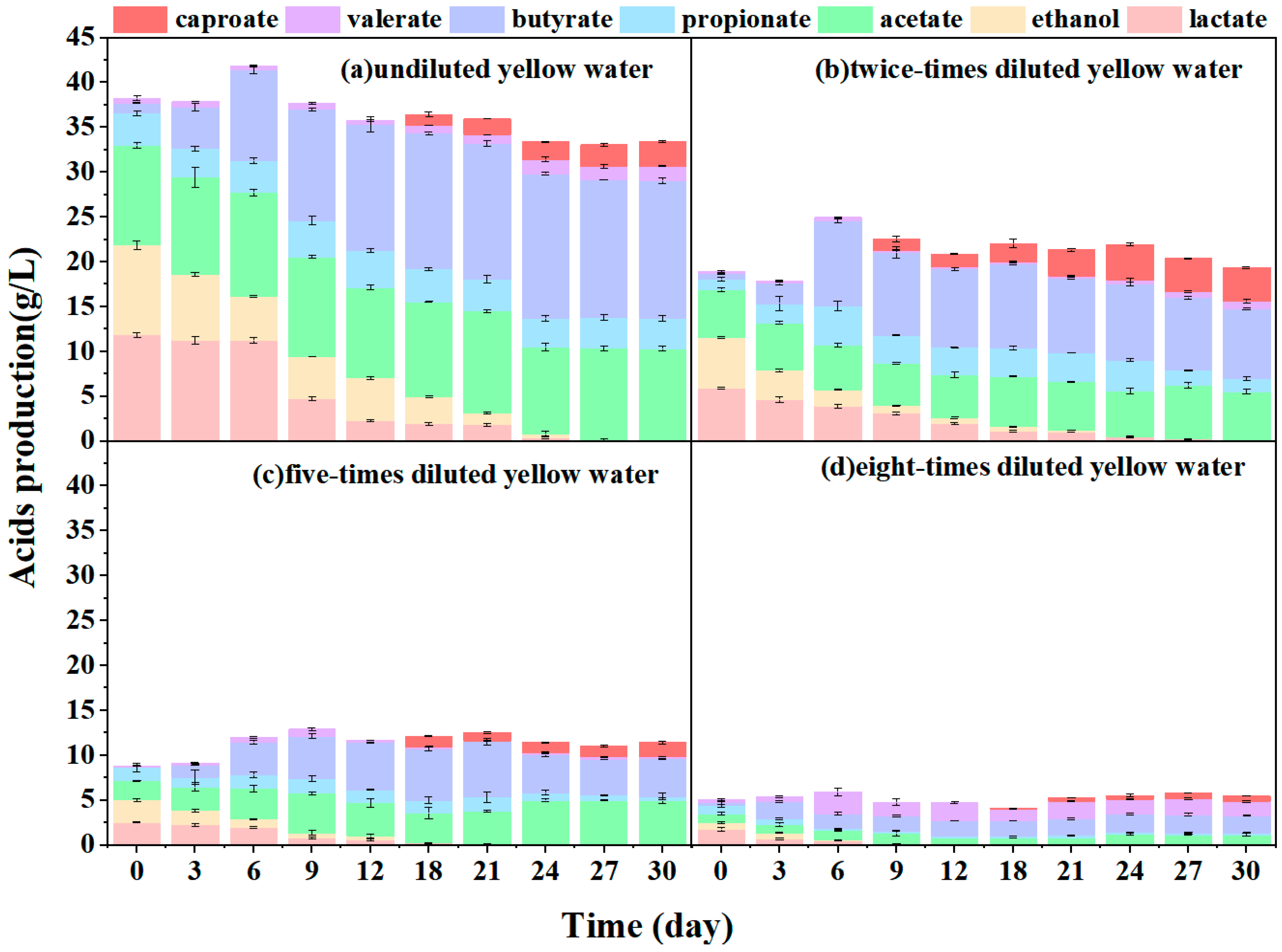

3.1. Direct Fermentation of Yellow Water for Caproate Production

3.2. Impact of Exogenous Electron Donors on Caproate Production by Yellow Water Fermentation

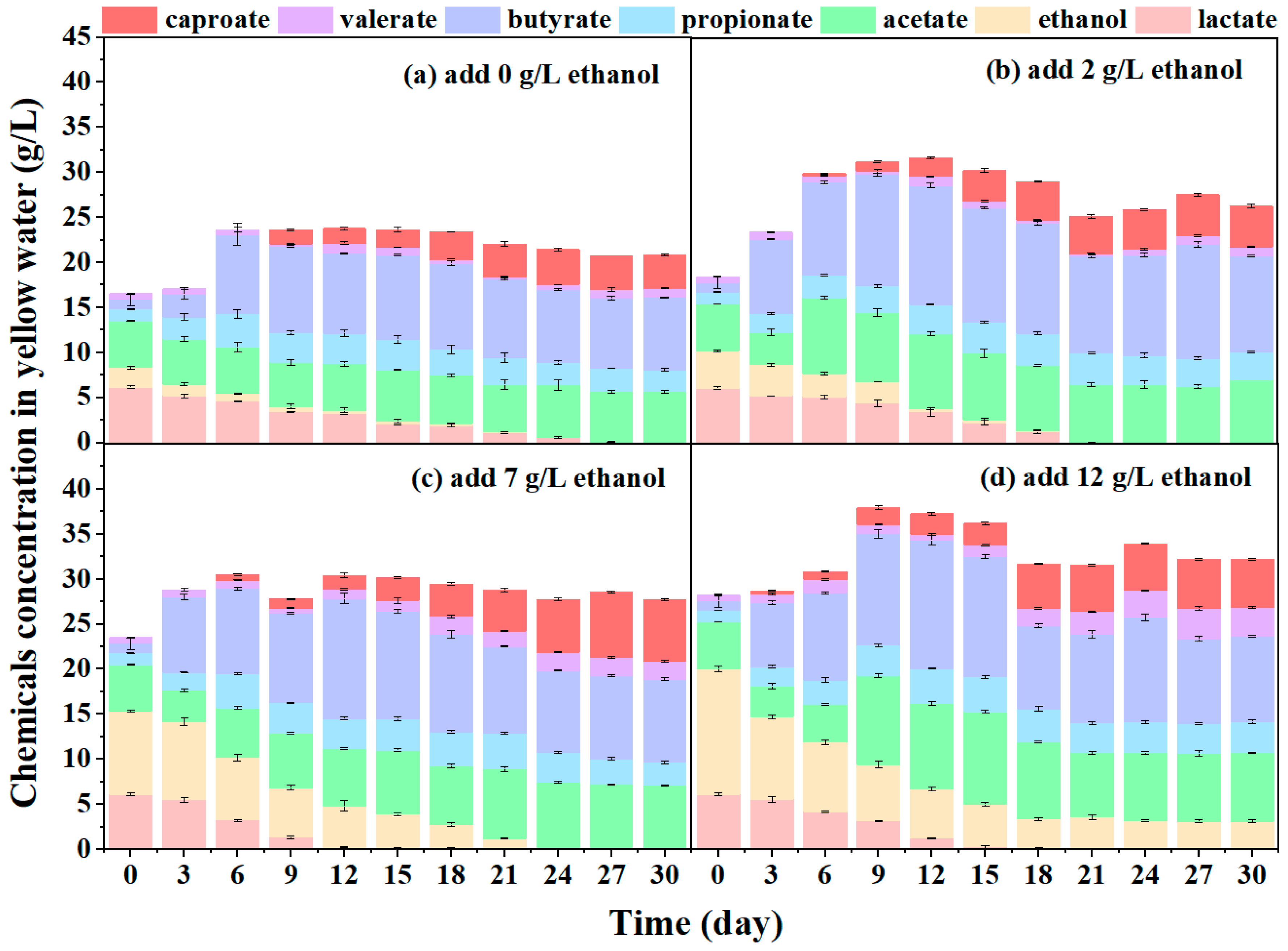

3.2.1. Ethanol Addition

3.2.2. Lactic Acid Addition

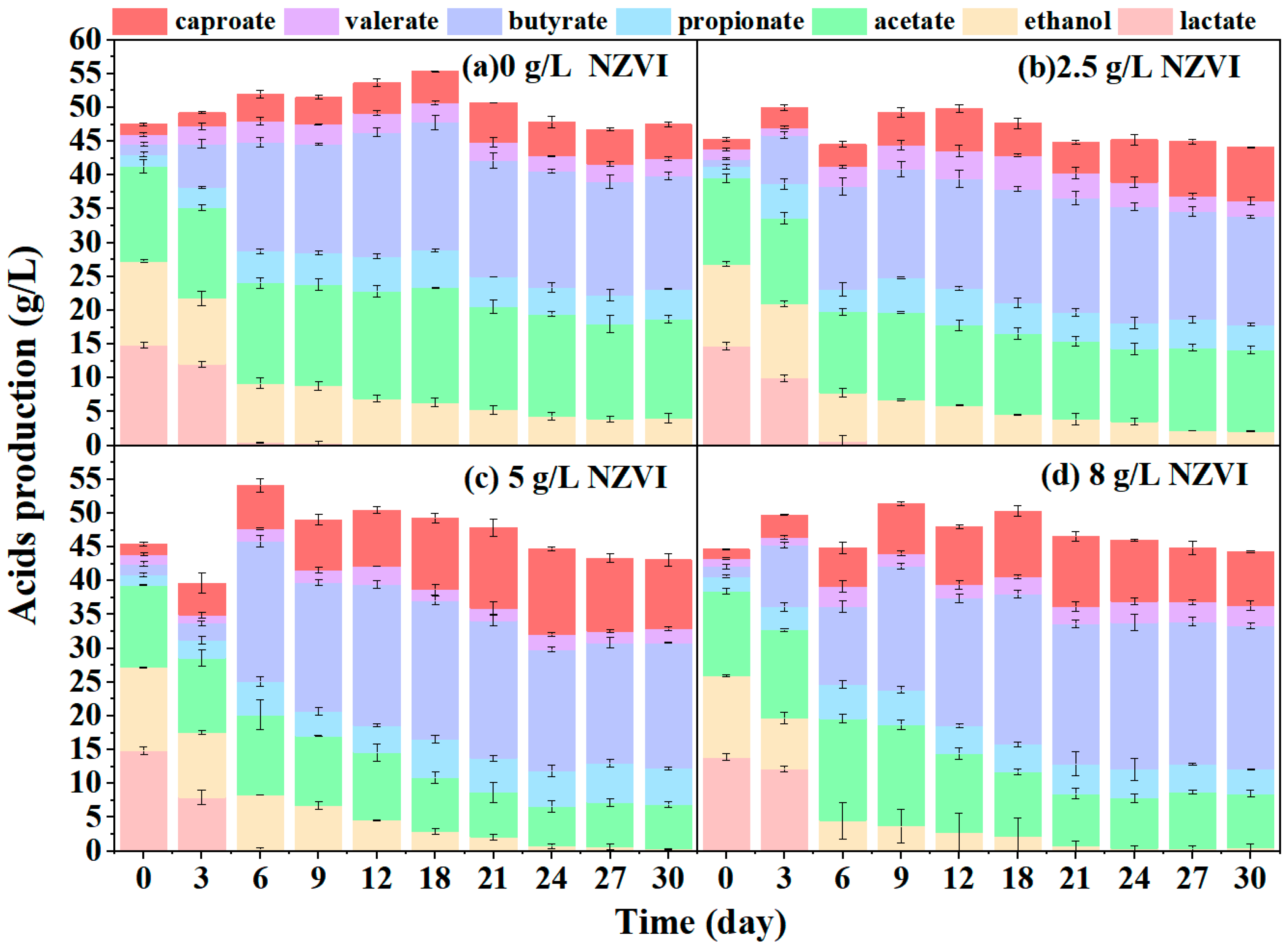

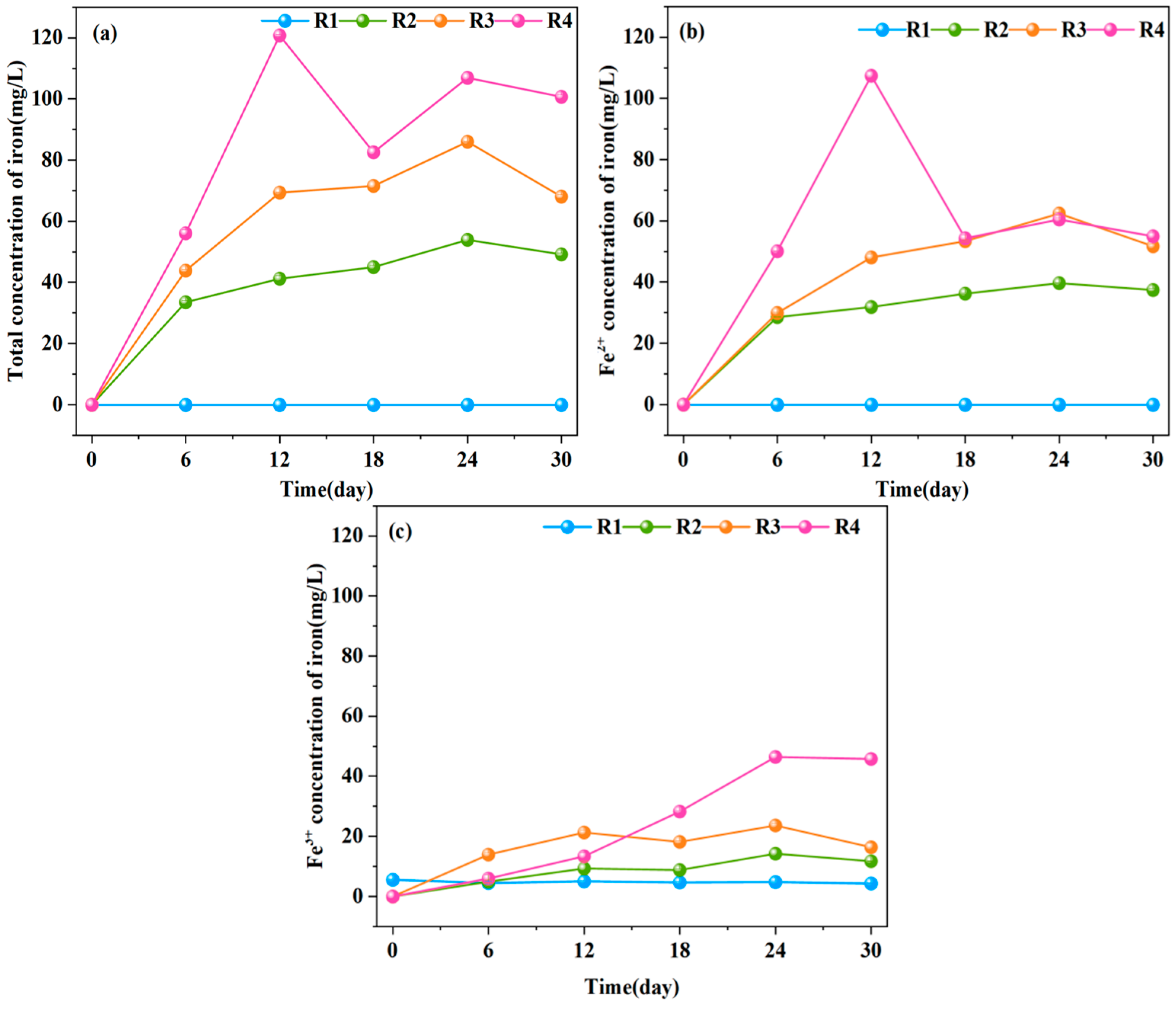

3.2.3. Zero-Valent Nano-Iron Addition

3.3. Developing Endogenous Electron Donor to Promote Caproate Production from Yellow Water Fermentation

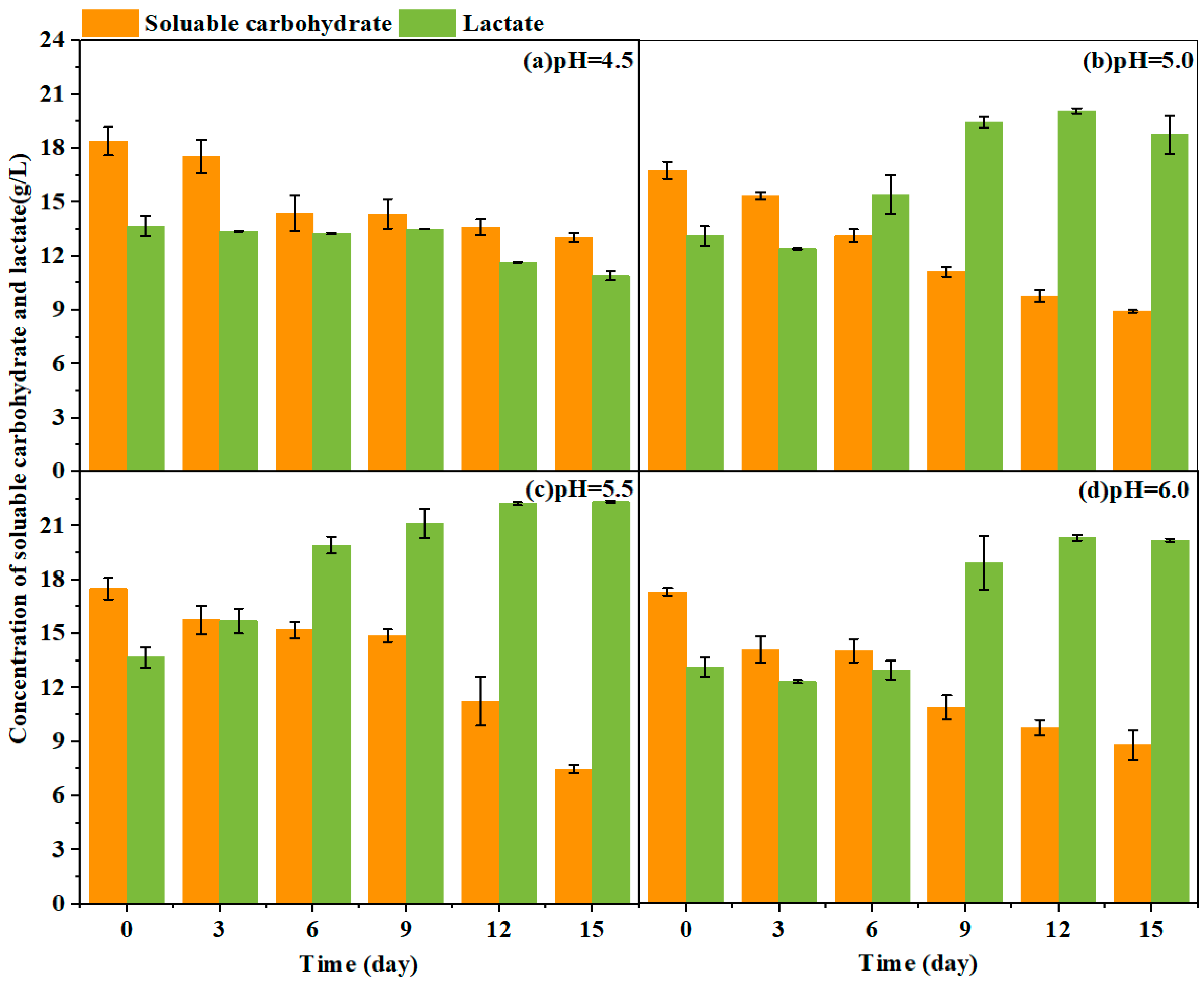

3.3.1. Lactic Acid Production from Yellow Water Fermentation to Improve Endogenous Reducing Power

3.3.2. Caproate Production by Secondary Fermentation of Yellow Water

3.4. Promoted Caproate Production from Yellow Water Fermentation by Complexing Exogenous and Endogenous Electron Donors

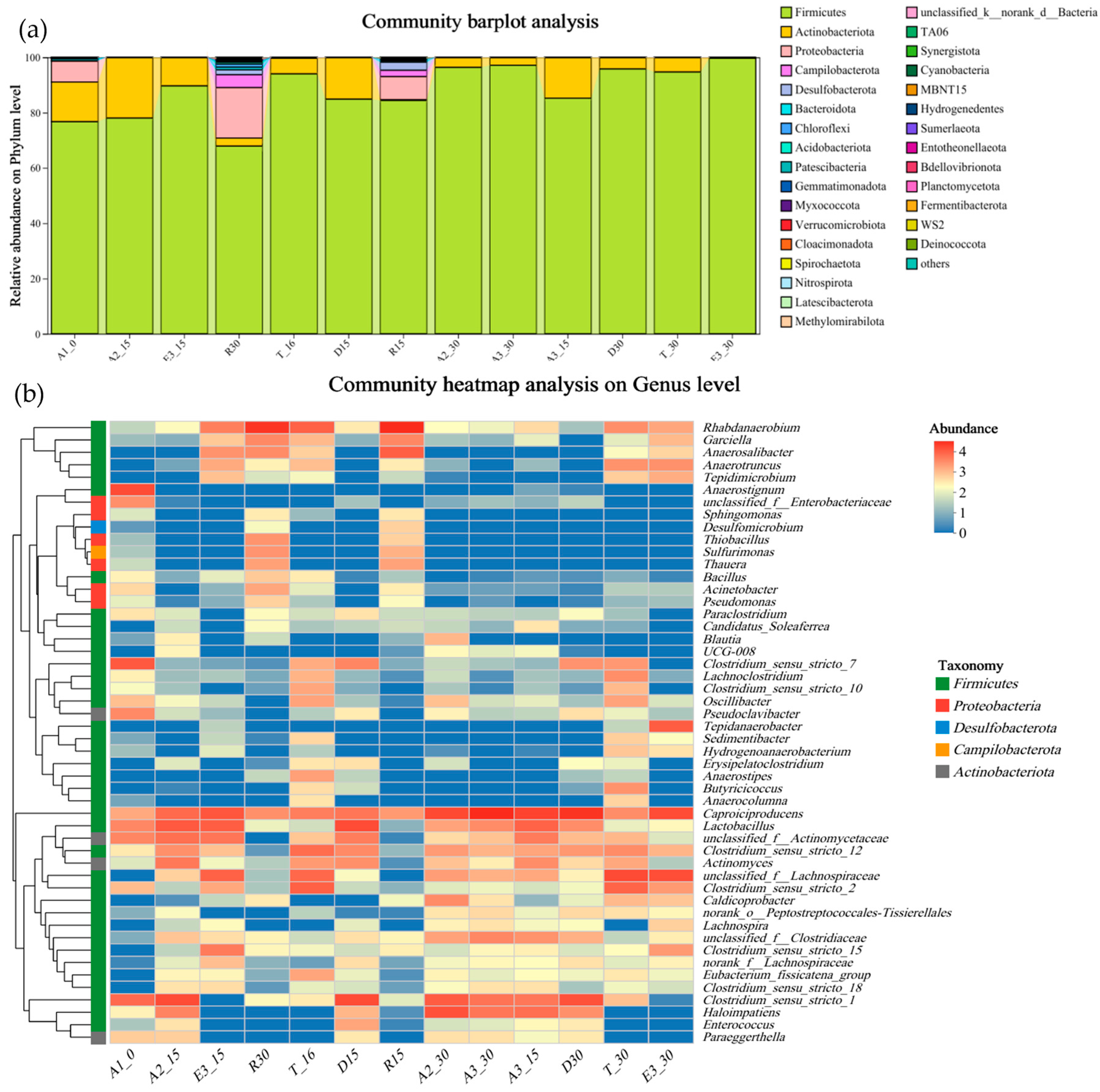

3.5. Microbial Community

3.5.1. Phylum-Level Distribution and Shifts

3.5.2. Enrichment of Caproate-Producing Genera

3.5.3. Supporting Taxa’s Functional Contribution

3.5.4. Ecological Implications

3.6. Quantitative Analysis of Electron Donors-Acceptor Balance Regulating Caproate Production from Yellow Water Fermentation

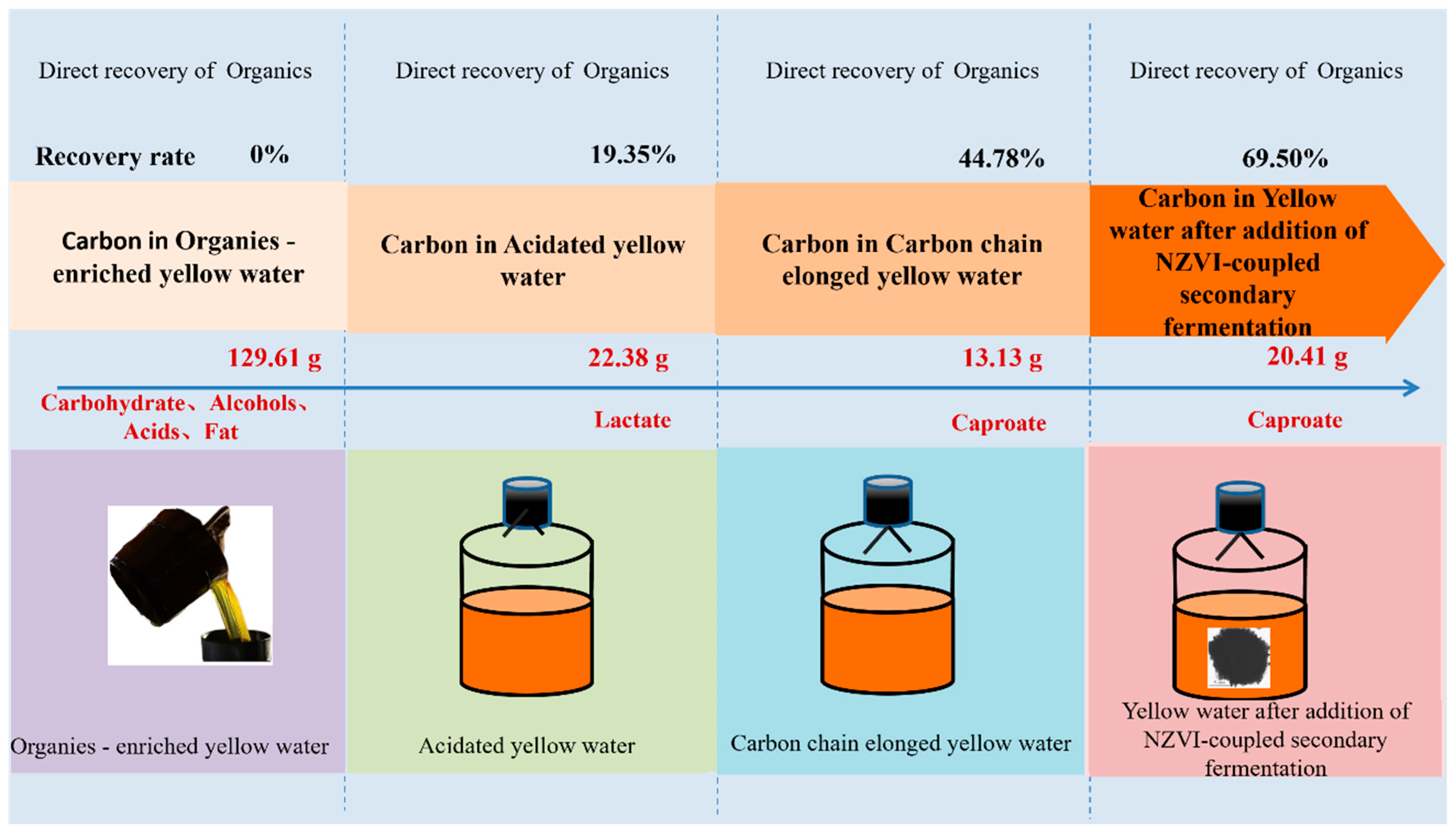

3.6.1. Carbon Recovery from Organic Fractions

3.6.2. Transformation of Carbohydrates into Functional Electron Donors

3.6.3. Impact of Electron Donor Strategies on Caproate Selectivity

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Substrate overloading hindered the direct fermentation of yellow water for caproate production, which could be alleviated by dilution, two-fold dilution obtaining 3.81 g·L−1 of caproate with a 16.23% conversion efficiency.

- (2)

- Lack of electron donors also hindered caproate production from yellow water fermentation, which could be alleviated by adding external electron donors, such as ethanol, lactic acid and NZVI. However, butyrate accumulation or microbial inhibition resulted after over-supplementation of external electron donors. The maximum performance of 12.50 g·L−1 caproate and a yield of 20.05% was achieved with 5 g·L−1 NZVI.

- (3)

- Developing endogenous electron donors was a promising approach to solve the shortage of electron donors during yellow water fermentation for caproate production. Endogenous lactic acid enrichment could yield 13.13 g·L−1 caproate with a 44.78% conversion efficiency, which even further improved to 20.41 g·L−1 and 69.50%, respectively, by integrating with NZVI addition.

- (4)

- Lactic acid enrichment and NZVI-mediated redox enhancement reconfigured microbial community structure toward increased medium-chain fatty acid productivity, including enrichments of Firmicutes and Clostridium species, particularly Caproiciproducens and Clostridium sensu stricto.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dahiya, S.; Sarkar, O.; Swamy, Y.V.; Mohan, S.V. Acidogenic fermentation of food waste for volatile fatty acid production with co-generation of biohydrogen. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 182, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J. Recent Advances in Resource Utilization of Huangshui from Baijiu Production. Fermentation 2024, 10, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Lin, Y.; Wang, P.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ma, H.; Sheng, Y.; Van Le, Q.; Xia, C.; Lam, S.S. Production of medium-chain fatty acid caproate from Chinese liquor distillers’ grain using pit mud as the fermentation microbes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 126037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, P.; Wu, B.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Ghasimi, D.S.M.; Zhang, X. Alleviation of Organic Load Inhibition and Enhancement of Caproate Biosynthesis via Fe3O4 Addition in Anaerobic Fermentation of Food Waste. Fermentation 2025, 11, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshemese, Z.; Buzón-Durán, L.; García-González, M.C.; Deenadayalu, N.; Molinuevo-Salces, B. A Novel Food Wastewater Treatment Approach: Developing a Sustainable Fungicide for Agricultural Use. Fermentation 2025, 11, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candry, P.; Ganigué, R. Chain elongators, friends, and foes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 67, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Liu, J.; Luo, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, D.; Xue, X.; Zheng, J.; Qiao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, Z.; et al. Analysis of the Influence of Microbial Community Structure on Flavor Composition of Jiang-Flavor Liquor in Different Batches of Pre-Pit Fermented Grains. Fermentation 2022, 8, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Bao, X.; Guo, W.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Luo, H.; Wang, H.; Ren, N. Medium chain carboxylic acids production from waste biomass: Current advances and perspectives. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yin, Y. Biological production of medium-chain carboxylates through chain elongation: An overview. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 55, 107882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, B. Chinese Baijiu and Whisky: Research Reservoirs for Flavor and Functional Food. Foods 2023, 12, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Duan, J.; Lv, S.; Xu, L.; Li, H. Revealing the Changes in Compounds When Producing Strong-Flavor Daqu by Statistical and Instrumental Analysis. Fermentation 2022, 8, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Guo, W.; Bao, X.; Meng, X.; Yin, R.; Du, J.; Zheng, H.; Feng, X.; Luo, H.; Ren, N. Upgrading liquor-making wastewater into medium chain fatty acid: Insights into co-electron donors, key microflora, and energy harvest. Water Res. 2018, 145, 650–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wu, W.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Fu, P.; Xia, C.; Lam, S.S.; Wang, Q.; Gao, M. Medium-chain fatty acid production from Chinese liquor brewing yellow water by electro-fermentation: Division of fermentation process and segmented electrical stimulation. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 360, 127510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Du, Z.; Zhao, L.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Huo, Z.; Du, Y.; Zhang, Z. Continuous production of aromatic esters from Chinese liquor yellow water by immobilized lipase in a packed-bed column bioreactor. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhou, A.; Mei, J.; Liu, Z.; Duan, H.; Luo, J.; He, Z.; Liu, W.; Ni, B.-J.; Yue, X. Synergy among multiple electron donors in electro-fermentation chain elongation: Accelerated directional electron transfer and enhanced microbial functions. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 434, 132817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montecchio, D.; Gazzola, G.; Gallipoli, A.; Gianico, A.; Braguglia, C.M. Medium chain Fatty acids production from Food Waste via homolactic fermentation and lactate/ethanol elongation: Electron balance and thermodynamic assessment. Waste Manag. 2024, 177, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhong, W.; Yang, T.; Dou, D.; Huang, Y.; Kong, Q.; Xu, X. Influence of acetate-to-butyrate ratio on carbon chain elongation in anaerobic fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 395, 130326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Ma, H.; Gao, M.; Qian, D.; Wang, Q.; Liu, L. Production of caproate from lactate by chain elongation under electro-fermentation: Dual role of exogenous ethanol electron donor. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 424, 132272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, L. Biocarrier-driven enhancement of caproate production via microbial chain elongation: Linking metabolic redirection and microbiome assembly. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 438, 133272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Jin, X.; Ye, R.; Lu, W. Nano zero-valent iron: A pH buffer, electron donor and activator for chain elongation. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 329, 124899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angenent, L.T.; Richter, H.; Buckel, W.; Spirito, C.M.; Steinbusch, K.J.J.; Plugge, C.M.; Strik, D.P.B.T.B.; Grootscholten, T.I.M.; Buisman, C.J.N.; Hamelers, H.V.M. Chain Elongation with Reactor Microbiomes: Open-Culture Biotechnology to Produce Biochemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 2796–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Qiu, S.; Xu, S.; Lu, X.; Wang, Y.; Ge, S. Nano zero valent iron stimulated acetaldehyde oxidation, electron transfer, and RBO pathway for enhanced medium-chain carboxylic acids production. Water Res. 2024, 262, 122103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Lee, C.-H.; Graham, N.J.D.; Ng, H.Y. Enhanced methane production and biofouling mitigation by Fe2O3 nanoparticle-biochar composites in anaerobic membrane bioreactors. Water Res. 2025, 280, 123522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefaniuk, M.; Oleszczuk, P.; Ok, Y.S. Review on nano zerovalent iron (nZVI): From synthesis to environmental applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 287, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, B.; Xu, M.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Liu, H. Deciphering the role and mechanism of nano zero-valent iron on medium chain fatty acids production from CO2 via chain elongation in microbial electrosynthesis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 863, 160898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.S.; Spakowicz, D.J.; Hong, B.-Y.; Petersen, L.M.; Demkowicz, P.; Chen, L.; Leopold, S.R.; Hanson, B.M.; Agresta, H.O.; Gerstein, M.; et al. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.-K.; Tian, X.-H.; Liu, C.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.-M. Microbiologic surveys for Baijiu fermentation are affected by experimental design. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 413, 110588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Shi, D.; Sun, J.; Li, A.; Sun, B.; Zhao, M.; Chen, F.; Sun, X.; Li, H.; Huang, M.; et al. Characterization of key aroma compounds in Gujinggong Chinese Baijiu by gas chromatography–olfactometry, quantitative measurements, and sensory evaluation. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Zhang, R.; Ding, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Tabassum, S.; Yang, F.; et al. Novel Approaches for the Dewatering of Anaerobic Digestate from Food Waste: EPS Stripping Coupled Skeletal Reconstruction. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 9302–9315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wan, B.; Li, Y.; Su, J.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, D.; Xu, Y. Correlation Analysis Between Volatile Flavor Compounds and Microbial Communities During the Fermentation from Different Ages Mud Pits of Wuliangye Baijiu. Fermentation 2025, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agler, M.T.; Wrenn, B.A.; Zinder, S.H.; Angenent, L.T. Waste to bioproduct conversion with undefined mixed cultures: The carboxylate platform. Trends Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.-K.; Geng, Z.-Q.; Sun, T.; Dai, K.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, R.J.; Zhang, F. Caproate production from xylose by mesophilic mixed culture fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 308, 123318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucek, L.A.; Nguyen, M.; Angenent, L.T. Conversion of l-lactate into n-caproate by a continuously fed reactor microbiome. Water Res. 2016, 93, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gildemyn, S.; Molitor, B.; Usack, J.G.; Nguyen, M.; Rabaey, K.; Angenent, L.T. Upgrading syngas fermentation effluent using Clostridium kluyveri in a continuous fermentation. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weimer, P.J.; Stevenson, D.M. Isolation, characterization, and quantification of Clostridium kluyveri from the bovine rumen. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 94, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, T.; Yin, Y.; Wang, J. Enhancement of medium-chain fatty acids production from sewage sludge fermentation by zero-valent iron. Chemosphere 2025, 370, 143912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, X.C.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Effect of pH on lactic acid production from acidogenic fermentation of food waste with different types of inocula. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 224, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Tao, Y.; Liang, C.; Li, X.; Wei, N.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Bo, T. The synthesis of n-caproate from lactate: A new efficient process for medium-chain carboxylates production. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Pu, Y.; Huang, J.; Pan, S.; Wang, X.C.; Hu, Y.; Ngo, H.H.; Li, Y.; Abomohra, A. Caproic acid production through lactate-based chain elongation: Effect of lactate-to-acetate ratio and substrate loading. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 28, 102918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaiz, M.; Baur, T.; Brahner, S.; Poehlein, A.; Daniel, R.; Bengelsdorf, F.R. Caproicibacter fermentans gen. nov., sp. nov., a new caproate-producing bacterium and emended description of the genus Caproiciproducens. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 4269–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakari, O.; Njau, K.N.; Noubactep, C. Effects of zero-valent iron on sludge and methane production in anaerobic digestion of domestic wastewater. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 8, 100377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Mu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Deng, L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Tabassum, S.; Liu, H. A comprehensive review on nature-inspired redox systems based on humic acids: Bridging microbial electron transfer and high-performance supercapacitors. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2026, 156, 101563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, K.; Chen, X.; Shi, J.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, H.; Tabassum, S.; Liu, H. Caproate Production from Yellow Water Fermentation: The Decisive Roles of Electron Donors. Fermentation 2025, 11, 689. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120689

Shen K, Chen X, Shi J, Zhang X, Sun Y, Liu H, Tabassum S, Liu H. Caproate Production from Yellow Water Fermentation: The Decisive Roles of Electron Donors. Fermentation. 2025; 11(12):689. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120689

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Kai, Xing Chen, Jiasheng Shi, Xuedong Zhang, Yaya Sun, He Liu, Salma Tabassum, and Hongbo Liu. 2025. "Caproate Production from Yellow Water Fermentation: The Decisive Roles of Electron Donors" Fermentation 11, no. 12: 689. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120689

APA StyleShen, K., Chen, X., Shi, J., Zhang, X., Sun, Y., Liu, H., Tabassum, S., & Liu, H. (2025). Caproate Production from Yellow Water Fermentation: The Decisive Roles of Electron Donors. Fermentation, 11(12), 689. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120689