Abstract

The safety and shelf life of wheat bread depend not only on recipe formulation and fermentation but also on post-baking handling, particularly the packaging stage. This study focused on evaluating the effect of the temperature of the bread crumb at the moment of packaging (30, 40, and 45 °C) on acrylamide content and microbiological spoilage during storage. Wheat bread samples prepared with 5, 10, and 15% Lactiplantibacillus plantarum sourdough were compared to control bread without sourdough. The results revealed that packaging at elevated temperatures (40–45 °C) led to higher residual acrylamide levels and accelerated mold growth due to condensation and increased humidity inside polyethylene bags. In contrast, packaging at 30 °C significantly reduced acrylamide formation, limited microbial proliferation, and extended the shelf life of bread up to 7 days while maintaining acceptable sensory qualities. The combined effect of sourdough concentration and packaging temperature demonstrated that the optimal conditions for ensuring safety and extending shelf life are the use of 5–10% sourdough and packaging at 30 °C. These findings underline the critical role of sourdough content and packaging temperature in controlling chemical contaminants and microbiological spoilage in bread production.

1. Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum) is a very important grain crop in Kazakhstan, as it is for the whole world. One of the main reasons for this is that it is a significant producer, with a total volume of 15.7 million tons, which is about 12.8% of the total volume in Europe [1,2]. In its October review, the International Grains Council (IGC) significantly raised its earlier estimates for the grain harvest in Kazakhstan in 2025.

Wheat bread is one of the earliest widely consumed and traditional foods in the world. In developed countries, the average consumption of wheat bread is 70 kg per capita per year [3], while in the Republic of Kazakhstan, this figure varies between 122 and 127 kg per capita [4]. One of the reasons for the high consumption of wheat in the world is its high production, which makes it an affordable grain. Despite the growing interest in whole-grain bread due to its high fiber content, which is beneficial to health, white wheat bread is still widely consumed around the world, given its sensory properties and affordable cost [5].

The baking industry is one of the leading food industries of the agro-industrial complex of the Republic of Kazakhstan and fulfills the task of producing products of prime necessity for the following reasons: availability, nutritional value, convenience, etc. According to the “Global Packaged Bread Market Research Report” the packaged bread market size in 2024 was USD 23.8 billion. The packaged bread market is expected to grow from USD 24.3 billion in 2025 to USD 30.4 billion by 2035. The packaged bread market is expected to register a CAGR (growth rate) of around 2.3% during the forecast period (2025–2035).

The widespread consumption of bread in packaged form stimulates the use of the latest methods to ensure the safety of bakery products, taking into account the packaging process, an important aspect of which is the reduction in acrylamide concentration and microbiological spoilage, depending on the temperature parameters of the packaging process. High temperatures and low humidity in cereal-based products promote chemical reactions between the ingredients of bakery products, including the Maillard reaction and caramelization [6]. These reactions cause desirable and undesirable changes in the final product [7]. Desirable changes include those that improve sensory characteristics, enhancing the taste, color, and aroma of the final product, which are highly valued by consumers. Undesirable changes include the formation of harmful compounds such as acrylamide, which is a potential human carcinogen [8].

Acrylamide is formed when carbohydrate-rich foods containing reducing sugars glucose and fructose and the amino acid asparagine, which are common in plant ingredients used to prepare many foods, are heated [9]. The concentration of acrylamide in processed foods has become a very serious health concern. Acrylamide is classified as a probable human carcinogen (Group 2A) by the International Agency for Research on Cancer [10]. Moderate levels of acrylamide (5–50 µg/kg) have been found in reheated protein-rich foods, whereas much higher levels (150–4000 µg/kg) are typical in carbohydrate-rich foods processed by high-temperature treatments [11]. Dietary exposure to acrylamide has been associated with increased risk of certain cancers, neurotoxicity, and reproductive effects [12,13]. Considering that bread and bakery products are one of the main contributors to acrylamide intake in the daily diet, reducing its concentration is a key objective in ensuring food safety and public health.

Currently, there are international recommendations for indicative levels of acrylamide in food products. According to Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/2158, indicative levels of acrylamide have been set at 50 μg/kg for soft wheat bread and 100 μg/kg for other types of bread [14]. Codex Alimentarius does not set specific limits for acrylamide in bread but provides recommendations for reducing its content, such as baking bread to a light color to reduce acrylamide formation, taking into account individual product design and technical capabilities [15].

Various studies have been conducted to reduce the amount of acrylamide in food products. For example, a number of studies have focused on the use of asparaginase to reduce asparagine content, which has been shown to reduce the amount of acrylamide in samples of cookies and crackers [16]. In such products, free asparagine in wheat flour is the main culprit in the formation of acrylamide, especially in cookies, which contain reducing sugars in the recipe. The use of asparaginase in bakery products has been shown to reduce acrylamide formation by 80–96% under optimal conditions, depending on dough type and water activity [17]. The effective dose when added to dough has been reported in the range of 200–1000 µg/kg dough [18]. Despite the small effect on the sensory and textural characteristics of finished bakery products [19], the use of asparaginase may currently be costly for production purposes. In addition, it is necessary to monitor the stability of asparaginase during food processing, as this enzyme preparation may pose a low but non-negligible risk of allergic reactions or residual activity in finished foods [20]. Similarly, Codină et al. reported that the use of dry sourdough significantly decreased acrylamide content in bread, mainly due to pH reduction and microbial metabolism of asparagine and reducing sugars [21].

In addition, the conditions under which bread is packaged after baking can affect acrylamide levels. When bread with a crumb temperature of 30–45 °C is packaged in plastic bags, high humidity and limited air exchange are created. These factors contribute to moisture condensation and changes in water activity, which affect the stability of already formed acrylamide and may accelerate secondary reactions between sugars and amino acids in the crumb [8,22]. Higher packaging temperatures (40–45 °C) enhance this effect due to more intense moisture release, while packaging at 30 °C minimizes post-baking changes and reduces residual acrylamide content [23]. Since the main content of acrylamide is found in bread crusts, it is important to investigate changes in acrylamide when the recommended cooling temperature of bread before packaging is not observed [24], as the crust is the primary part of the bread that comes into contact with the packaging material.

One method for reducing acrylamide levels is to use fermentation. Fermentation through souring is one of the most natural and optimal processes for ensuring pleasant sensory and quality characteristics in bread [25]. The difference in the method for reducing acrylamide is largely due to a decrease in pH rather than the use of precursor nutrients such as reducing sugars and asparagine by microorganisms [26]. Most of the beneficial and valuable properties attributed to sourdough are mainly associated with its dominant microflora, and the choice of sourdough cultures has a decisive influence on the taste, technological properties, nutritional properties, and safety of bread. Studies have shown that fermentation using selected LAB strains is more effective in reducing acrylamide content in bread due to a decrease in dough acidity, which slows down the Maillard reaction [27]. In addition, the selection of various LAB with a wide range of antifungal activity and good technological properties is an important issue for improving the microbiological safety of bread. LAB strains from sourdough can potentially be used for the biopreservation of bread, as they are safe for consumers. These LABs naturally predominate in sourdough and produce metabolites that can inhibit the growth of fungi under natural conditions. Thus, the use of sourdoughs based on selective LABs with special properties, such as the ability to reduce acrylamide levels, as well as the secretion of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances, may be very promising for the baking industry.

The study [28] evaluated combinations of LABs for Type II sourdough production and their influence on bread quality and Maillard-reaction products. Sourdoughs based on L. plantarum and P. pentosaceus increase the overall acceptability, specific volume, and porosity of wheat bread. In addition to the fact that sourdoughs obtained using combinations of selected strains of LAB improve the quality of bread, fermentation with ready-made sourdough also reduces the acrylamide content in wheat bread samples from 29.5% (sourdough prepared with P. pentosaceus and L. mesenteroides) to 67.2% (sourdough prepared with P. pentosaceus and L. curvatus). However, the effect of temperature in the center of the bread crumb during packaging on acrylamide change has not been studied. The study [29] also achieved positive results, but the correlation between acrylamide change and bread temperature change was not investigated.

Sourdough is also one of the oldest methods of grain fermentation, used mainly to improve the microbiological safety of wheat bread. Studies have shown [30,31] that the quality and shelf life of bread can be improved by fermentation using the antifungal strain Lactobacillus plantarum. The study [32] examined the effect of packaging materials and storage conditions on the microbiological quality of millet sourdough bread. Bread samples were packaged in low-density polyethylene and aluminum foil and stored at temperatures of −5, 4, 6, 28, and 37 °C. The total number of bacteria (log CFU/g) and the total number of fungi (spores/g) increased with increasing storage temperature and number of storage days.

In view of the above and the insufficient study of changes in acrylamide content and the dynamics of microbiological spoilage during the packaging of wheat bread at varying temperatures, this area of research is of particular relevance.

The aim of this study is to comprehensively investigate changes in acrylamide concentration and indicators of microbiological spoilage during the packaging of wheat bread at different temperatures, baked using different levels of sourdough fermented with Lactobacillus plantarum.

The scientific novelty of the study lies in establishing the dependence of acrylamide formation on the amount of sourdough and the temperature in the center of the crumb before packaging. The scientific hypothesis underlying the work suggests that different levels of sourdough fermented with L. plantarum culture, combined with a decrease in the temperature in the center of the crumb of wheat bread immediately before packaging will provide a synergistic effect, expressed in two key aspects, (1) a significant reduction in the final concentration of acrylamide and (2) a significant slowdown in the rate of microbiological spoilage, which together will lead to an increase in the shelf life of the finished product while maintaining acceptable organoleptic characteristics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Used for the Preparation of Sourdough

Wheat flour of first grade was obtained from “Agrofirma TNK” LLP (Almaty, Kazakhstan). L. plantarum strain No. 322, acquired from the SPE Antigen LLP collection (Almaty region, Kazakhstan), was used. The strain was stored at −4 °C in a Microbank system (PRO-LAB DIAGNOSTICS) and reactivated before use by inoculation into MRS broth (TM 147, Titan Biotech Ltd., Rajasthan, India) at 37 °C for 24 h. Cell viability was determined by plate counting on MRS agar, confirming a viable cell density of approximately 1.5 × 109 CFU/mL at the end of incubation. The pH of the sourdough was measured at 0, 24, and 48 h to monitor acidification kinetics during fermentation by L. plantarum.

2.2. Wheat Sourdough Preparation and Sampling

Wheat sourdough samples were prepared by using the following procedure: 1 kg of flour and 650 mL of water were used to prepare the sourdough, to which a liquid culture of L. plantarum was added in an amount equal to 3% of the water volume (≈19.5 mL per 650 mL of water). The resulting doughs were left to stand for solid-state fermentation for 48 h at 24 ± 2 °C. The sourdough was prepared in a single batch and used in different quantities (5%, 10%, 15%) for baking wheat bread samples for acrylamide content and the microbiological safety parameters analysis.

2.3. Wheat Bread Formulation and Preparation Technology

The wheat bread formula consisted of 1.0 kg of refined wheat flour obtained from “Agrogirma TNK” LLP (Almaty, Kazakhstan) and wheat sourdough, 1.5% salt (regular, refined table salt, “Araltuz”, Almaty, Kazakhstan), 1.5% instant yeast, and 650 mL of tap water (room temperature, 22 °C). The ratio of ingredients corresponds to the basic production recipes for white wheat bread [33,34]. Thus, this recipe can be considered a universal and representative model of wheat bread. At the same time, it was adapted for small batches (1 kg of flour) in laboratory conditions, which allowed for more precise control of technological factors (crumb temperature, packaging conditions, amount of sourdough). Therefore, the results obtained can be extrapolated to industrial production, but further testing on a real production scale is required for final validation. The samples without the addition of LAB sourdoughs were analyzed as control bread samples. The tested bread groups were prepared by adding 5, 10, or 15% of LAB sourdoughs to the main recipe. The recipe for the control and experimental samples is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Recipe for control and experimental samples.

In total, 4 groups of dough and bread samples were prepared and tested (BC—control bread; LAB-5%, LAB-10%, LAB-15%—bread samples with 5, 10 and 15% of added L. plantarum strain No. 322 sourdough in samples, respectively). The dough was mixed for 3 min at a low speed, then for 7 min at a high-speed in a dough mixer (KitchenAid Artisan, Greenville, OH, USA). Then, the dough was left at 24 ± 2 °C for 20 min of relaxation. Afterwards, the dough was shaped into 400 g loaves, then formed and proofed at 45 ± 2 °C and 80% relative humidity for 40 min. The bread was baked in a deck oven (EKA, Borgoricco PD, Milano, Italy) at 220 °C for 20 min. The dough was prepared in a single batch for each treatment, from which three loaves were baked under identical conditions. All analyses of bread quality and safety, with the exception of sensory analysis, were performed in technical triplicates using samples obtained from these loaves. To simulate different production conditions, bread samples were cooled at 22 ± 2 °C and 60 ± 2% relative humidity until crumb temperature reached 30, 40, or 45 °C. Cooling was carried out without forced ventilation, under natural air circulation in the laboratory environment. The average cooling rates were 1.35 °C/min (95–45 °C), 1.22 °C/min (95–40 °C), and 0.92 C/min (95–30 °C). Crumb temperature was measured at the geometric center of bread samples by the temperature probe TA278 (SINOTIMER, Hangzhou, China), which was inserted perpendicularly through the upper crust to a depth of 6 ± 0.2 cm. After cooling, the bread samples were packaged in LDPE bags and stored at room temperature. After 12 h of storage, bread samples were subjected to analysis of acrylamide content, specific volume, shape coefficient, crumb porosity, moisture content, mass loss after baking, texture, crust and crumb color coordinates, sensory characteristics, and overall acceptability.

2.4. Materials and Standards for Analysis of Acrylamyde

Acetonitrile, methanol, hexane, and acrylamide (>99.5% purity) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Primary and secondary amines (PSA-sorbent) were purchased from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium). Stock standard of acrylamide (1 mg/mL) were prepared by dissolving 10 mg of the acrylamide in 10 mL MilliQ water and stored at 4 °C. All calibration solutions were prepared daily by a serial dilution also in MilliQ water.

2.4.1. Extraction Procedure of Acrylamide in Bread

Extraction of acrylamide was adapted from Bartkiene et al. [35] with slight modifications. Two grams of the sample and 5 mL of hexane were added to a 50 mL centrifuge tube, and then the tube was vortexed. Distilled water (10 mL) and acetonitrile (10 mL) were added, followed by the QuEChERS extraction salt mixture (4.0 g anhydrous MgSO4 and 0.5 g NaCl). The sample tube was shaken for 1 min vigorously and centrifuged at 4500× g for 5 min. The hexane layer was discarded and 1 mL of the acetonitrile extract was transferred to the tube containing 50 mg of PSA-sorbent and 150 mg of anhydrous MgSO4. The tubes were vortexed for 30 s and then analyzed by HPLC-DAD.

2.4.2. Determination of Acrylamide by HPLC-DAD

The quantitative analysis of acrylamide was performed by liquid chromatography using a Waters Agilent 1260 Infinity II HPLC system equipped with a Diode Array Detector (DAD) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The separation of acrylamide was achieved with Poroshell 120 EC-C18 (100 × 3 mm, particle size 2.7 µm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The mobile phase was used in an isocratic eluent mode of 50% methanol and 50% acetonitrile. The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min, the column temperature was 30 °C, the injection volume was 5 μL, the analysis time was 13 min, and the DAD detector wavelength was 210 nm. The acrylamide levels in selective samples were quantified by the external standard method.

2.4.3. Method Validation

The sample preparation method for acrylamide in bread samples by HPLC-DAD was validated. Calibration curves were generated by regressing analyte peak areas against concentration over 0.1–0.5 mg/mL (R2 = 0.9227).

Validation parameters included linearity, repeatability, accuracy (recovery rates), and limits of detection and quantification (LOD/LOQ). LOD and LOQ were derived from the matrix-matched calibration in accordance with a laboratory guide (Eurachem Guide, 2025), using the residual standard deviation of the regression together with the calibration slope (the 3.3 and 10 criteria).

Recovery rate was assessed by spiking of acrylamide into blank bread samples (0.05 mg/kg, n = 4).

2.5. Bread Analysis Methods

Bread volume was established using the American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC) method 10-05.01 [36], and the specific volume was calculated as the ratio of volume (cm3) to weight (g). The bread shape coefficient was calculated as the ratio of bread slice width (in mm) to height (in mm). Bread crumb porosity was evaluated by GOST 5669-96 using Zhuravlev’s device (PZH-1M) (Kolba LLC, Voronezh, Russia) [37]. The moisture content was determined according to the GOST 21094-2022 [38]. Mass loss after baking was calculated as a percentage by measuring the loaf dough mass before and after baking. Crust and crumb color parameters were evaluated using a CIE L*a*b* system (CromaMeter CR-400, Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). Chroma was calculated as and the difference in color as . The deformation force of bread crumb was evaluated using the Brookfield CT3 Texture Analyzer (AMETEK Brookfield, Middleboro, MA, USA). Samples in the form of 10 mm thick slices were compressed with a cylindrical stamp with a diameter of 25 mm to 50% of the initial thickness at a speed of 1 mm/s. The force–deformation curve was recorded and the deformation work (compression energy) was calculated, expressed in millijoules (mJ).

The overall acceptability of bread samples was evaluated using a 9-point hedonic scale, where 1 and 9 indicate the lowest (extremely dislike) and highest (extremely like) intensity, respectively. The assessment was carried out by 15 trained panelists, selected and prepared in accordance with ISO 8586:2012 [39]. Although hedonic scales are typically applied in consumer tests (ISO 11136:2014) [40], in this case they were used with trained assessors to ensure higher consistency and reliability of the evaluations. It should be noted that the results represent the acceptability according to the trained panel and may not fully reflect consumer preferences. The final list of descriptors included crust/crumb color, odor intensity, bread odor, additional odor, flavor intensity, bread flavor, additional flavor, acidity, porosity, bitterness, springiness, hardness, crumb moisture, and overall acceptability. Between the samples, the judges were asked to rinse their mouths with water.

For the mold spoilage analysis, bread samples were packed at 45, 40 and 30 °C crumb temperature in LDPE and stored at room temperature (24 ± 2 °C). The surface of each sample was monitored daily for visible fungi colonies. Samples with no visible colonies (−), one colony (+), two (++), and three or more (+++) were identified. The following microbiological indicators were determined: total mesophilic aerobic and facultative anaerobic microorganisms (TMAFAMs) using GOST 10444.15-94, which corresponds to standard enumeration methods [41], and molds (Microscopic Fungi), determined according to GOST 10444.12-2013, which specifies colony-counting techniques for enumerating molds in food products [42].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The values are presented as mean ± standard error (for dough and bread quality properties n = 3; for bread sensory characteristics and overall acceptability n = 15). Data were subjected to the analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the statistical package SPSS for Windows (Ver.27.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA, 2019). Calculated mean values were compared using Tukey multiple range test with significance defined at p < 0.05. The mathematical modeling of the influence of factors (amount of sourdough in recipe; Crumb temperature before packing) to acrylamide content in bread was carried out by STATISTICA for Windows (Ver.12.5, StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA, 2014).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Parameters of Wheat Sourdough and Bread with L. plantarum

The parameters of wheat sourdough with L. plantarum are presented in Table 2. A significant statistical difference was observed between each day of acidity measurement (p < 0.001). The use of L. plantarum showed good acidification rates in wheat flour; the pH of the sourdough decreased by an average of 22.83% during the first 24 h, and after 48 h, the difference between the initial pH was 33.18%. These results suggest that when using L. plantarum to prepare wheat sourdough, it is recommended to ferment the sourdough for 48 h. Since LABs have effective amylolytic activity, a rapid decrease in pH is expected. However, due to the low buffering capacity of white wheat flour, the pH drops rapidly, but the total acidity remains low [43].

Table 2.

Parameters of prepared sourdough with the addition of L. plantarum.

The quality indicators of the prepared samples are shown in Table 3. Compared to the control sample, in the experimental samples, as the amount of sourdough increased, the specific volume increased by 1.45%, 14%, and 11.11%, respectively. The porosity of sourdough bread was also higher than the control by 2.44%, 6.79%, and 4.85%, respectively. The increase in volume and porosity is associated with the release of a larger amount of carbon dioxide, which is produced when baker’s yeast is used in combination with LAB [44], which is also proven by a strong positive correlation between these indicators (r = 0.906). In addition, the increase in gas retention capacity and dough elasticity is associated with improved gluten due to increased acidity caused by LAB [45]. However, an excessive amount of sourdough can lead to overly elastic gluten, which contributes to a decrease in the volume and porosity of bread [46]. This effect is noticeable when comparing the specific volume and porosity of samples using 10% and 15% sourdough, where an increase in the amount of sourdough reduced the above values by 2.54% and 1.81%, respectively.

Table 3.

The effect of the amount of sourdough on the quality characteristics of bread.

The addition of sourdough to the recipe contributed to greater weight loss after baking compared to the control, at 24.5%, 26.8%, and 31.2%, respectively. Strong positive correlations were found between weight loss after baking and porosity (r = 0.898; p < 0.001); weight loss after baking and specific volume (r = 0.815; p = 0.001). Recent studies have shown that intense moisture evaporation during baking contributes to the formation of a more developed porous crumb structure, which confirms the strong positive correlation between mass loss and bread porosity [47].

The addition of sourdough reduced the deformation force and moisture content in the finished samples compared to the control. However, as the proportion of sourdough increased, these values also began to rise; when using 15% sourdough, the deformation force and moisture content were almost identical to the control sample. Similar results were observed where sourdough incorporation improved bread texture and reduced moisture content and crumb hardness [48].

3.2. Change in Color of the Crumb/Crust of Bread Samples

The study of the effect of the amount of sourdough on the color characteristics of bread samples is shown in Table 4. When comparing the color characteristics of the bread crust, no significant difference was observed in the coordinates of the a* axis of the crust and the b* axis of the crumb between the control and experimental samples. The values for bread with 5% sourdough were the highest in terms of the L* axis coordinates (on average, 18.8% higher than the control and 38.3% and 35.3% higher than the samples with 10% and 15% sourdough, respectively), as well as in terms of the b* axis coordinates (on average, 18.5% higher than the control and 54.8% and 27.3% higher than the samples with 10% and 15% sourdough, respectively). When comparing the color coordinates of the bread crumb, the experimental samples significantly exceeded the control bread in all color characteristics. According to the L* axis coordinates, the highest value was for bread with 10% sourdough (on average, 3.99% higher than the control and 1.55% and 0.56% higher than the samples with 5% and 15% sourdough, respectively). On the a* axis, the experimental samples were 3.0, 2.76, and 2.26 times higher than the control. The coordinates of the sample with 5% sourdough were 7.57% higher than the control sample and 0.14% and 0.98% higher than the samples with 10% and 15% sourdough, respectively. The calculation of total color differences () revealed that the crust color of bread with 5% and 10% sourdough substitution differed substantially from the control ( = 10.11 and 8.78, respectively), while the 15% sample showed only moderate deviation ( = 3.00). In the crumb, the differences were smaller ( = 2.58, 2.99, 3.50 for LAB-5%, LAB-10%, LAB-15%, respectively), corresponding to weak-to-moderate visual perceptibility. In terms of color saturation (C*), the control crust had a value of 25.55. The 5% sourdough crust showed an increased saturation (C* = 29.23), while the 10% and 15% samples had reduced values (C* = 20.52 and 24.07, respectively). In the crumb, the control sample exhibited a chroma value of 20.08, and all sourdough variants showed slightly higher saturation (C* = 21.64, 21.61, 21.42 for LAB-5%, LAB-10%, and LAB-15%, respectively). These findings indicate that sourdough addition strongly affected crust color, particularly at 5–10% substitution, while changes in crumb color were less pronounced. The duration of fermentation affects the color characteristics, which suggests that as the fermentation time increases, the bread will have lower and higher L* and a* values [49]. It is also known that the use of sourdough results in higher a* and b* values in the crust and crumb of bread [50].

Table 4.

Influence of different quantities of wheat sourdough on wheat bread color characteristics.

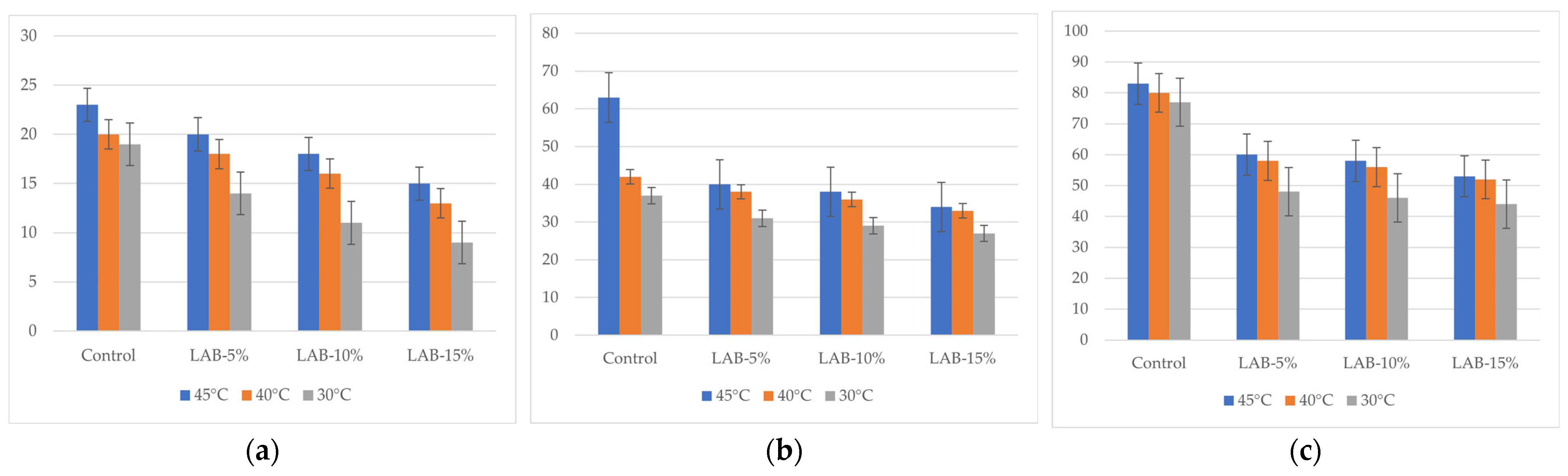

A strong positive correlation was found between porosity and L* coordinates (r = −0.856; p = 0.003). Specific volume also showed a moderate positive correlation with L* and a* coordinates of the crumb (r = 0.751; p = 0.02 and r = 0.678; p = 0.045, respectively). Bread moisture showed a strong negative correlation with the L* coordinates of the bread crust (r = 0.864; p = 0.003); it also correlated moderately negatively with the b* coordinates of the crust and crumb (r = −0.744; p = 0.021 and r = −0.754; p = 0.019, respectively). Recent modeling and experimental studies have shown that a more developed porous crumb structure leads to greater moisture loss during baking and faster crust darkening, owing to the increased surface area and vapor transport pathways [51]. Bread crumb images are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Bread crumb images: (a) control sample, (b) bread with 5% sourdough, (c) bread with 10% sourdough, (d) bread with 15% sourdough.

The positive correlation between specific volume and crust/crumb color coordinates may be due to the fact that a larger volume of bread promotes a more even distribution of heat and moisture during baking, which affects the color characteristics of the crumb. Monteiro et al. noted that a larger volume of bread contributes to a more even distribution of heat and moisture during baking, which affects the color characteristics of the crumb [52].

Although increased humidity does slow down the Maillard reaction and caramelization, darkening of the crust was observed in samples of bread made with sourdough. This effect is explained by the fact that LAB alter the biochemical composition of the dough: the pH decreases, and the number of organic acids and low-molecular-weight sugars involved in alternative pathways of colored compound formation increases. Acidification enhances the formation of melanoidins and polyphenolic complexes, which are not necessarily accompanied by the formation of acrylamide [27,28]. In addition, L. plantarum is capable of producing metabolites (e.g., phenolic compounds and peptides) that contribute to color intensity [49]. In addition, recent studies emphasize the influence of baking conditions (time, temperature, and moisture loss) on moisture redistribution and textural properties of bread, which consequently affect crust color [53].

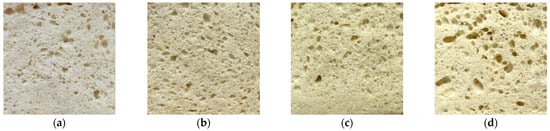

3.3. Sensory Characteristics of Bread

The results of sensory evaluation of bread samples, conducted on a 9-point hedonic scale, demonstrated significant differences in the perception of various characteristics depending on the level of L. plantarum sourdough addition. The control sample received high scores for characteristics such as bread aroma (8.48), bread taste (8.43), elasticity (8.83), and crispness (8.67), as well as maximum overall acceptability (8.60).

The sample with 5% sourdough also received a high overall rating (8.50), almost on par with the control. Panelists noted that it had the most appealing color (8.24) and higher flavor intensity (8.87) compared to the control. In addition, LAB-5% was characterized by more pronounced acidity (7.02) and “additional flavor” (7.14), which was perceived positively and reflected in high acceptability.

At the same time, samples with 10% and 15% sourdough received significantly lower overall acceptability ratings—7.61 and 6.90, respectively. This is due to increased acidity and reduced intensity of the “bread” taste and aroma. LAB-10% and LAB-15% are characterized by lower scores for bread taste (7.60 and 6.02) and aroma (6.60 and 6.50), as well as lower elasticity and moisture content. The panelists noted an excessively sour aftertaste (acidity 5.95 and 4.85 vs. 5.03 in the control) and bitterness (especially in LAB-15%—4.14), which negatively affected the overall acceptability.

Thus, moderate addition of sourdough (5%) improved certain organoleptic characteristics (color, flavor intensity) without compromising overall acceptability, while increasing its proportion to 10–15% led to over-acidification and lower scores for taste, aroma, and texture. These results are consistent with previous studies, which noted that the optimal dose of sourdough should ensure a balance between improving texture and taste properties and preventing excessive acidity [54,55]. The results of the study are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Sensory characteristic profiles ((a)—color, odor, and flavor characteristics; (b)—texture characteristics) of wheat bread prepared with and without sourdough (Control—bread prepared without sourdough; LAB-5%, LAB-10%, LAB-15%—bread prepared with 5%, 10%, and 15% sourdough, respectively).

To identify correlations between sensory attributes and objective color indicators of bread, Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed. The results showed that a number of sensory characteristics were significantly associated with coordinate a*. Thus, the intensity of the additional aroma (r = −0.822, p < 0.01), acidity (r = −0.825, p < 0.01), and porosity (r = −0.617, p < 0.05) had significant negative correlations with a* coordinates of the crust. This indicates that an increase in acidity and related sensory characteristics is accompanied by a decrease in the red-brown hue of the crust. Bread sensory evaluation results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Bread sensory evaluation results.

In addition, the bread aroma negatively correlated with the L* of the crumb (r = −0.732, p < 0.01) and the b* of the crumb (r = −0.651, p < 0.05), indicating that a lighter and less yellow crumb was associated with a more pronounced bread aroma. Crumbly texture also showed a negative correlation with L* of the crumb (r = −0.636, p < 0.05), indicating a link between light-colored crumb and the perception of a more crumbly texture.

Overall acceptability had a negative correlation with the L* of the crumb (r = −0.555, p = 0.061, trend toward significance), which may reflect the panelists’ preference for samples with a more saturated crumb color. Overall, these results confirm that consumers’ perception of bread depends not only on the sensory characteristics of taste and aroma but also on the color properties of the crust and crumb.

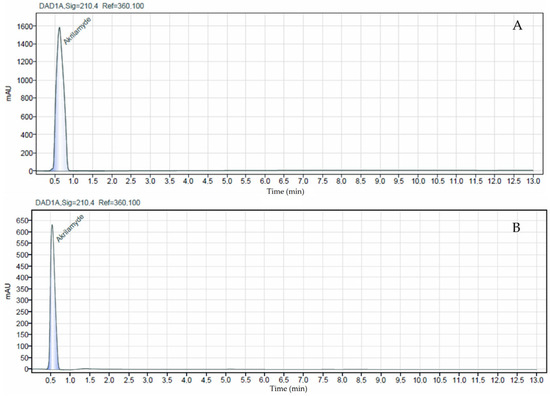

3.4. Validation of the Analytical Method for Acrylamide Determination

The HPLC-DAD method for acrylamide determination in bread samples demonstrated acceptable analytical performance. The calibration curve over the range of 0.1–0.5 mg/mL showed good linearity (R2 = 0.9227). The limit of detection and quantification were 1.91 µg/kg and 5.80 µg/kg, respectively, calculated from the matrix-matched calibration according to Eurachem. Accuracy, evaluated by spiking blank bread samples at 0.05 mg/kg (n = 4), yielded a mean recovery of 103.8% ± 5.0, indicating efficient extraction and minimal matrix interference. Repeatability, expressed as the relative standard deviation (RSD%) of replicate measurements, was 4.83%, confirming good short-term precision and reproducibility of the method. The peak corresponding to acrylamide is clearly observed at the same retention time in both chromatograms, confirming its presence in the sample, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Chromatograms of the acrylamide standard (0.1 mg/mL, (A)) and the analyzed bread sample (B).

3.5. Acrylamide Content in Control and Fermented Bread Samples

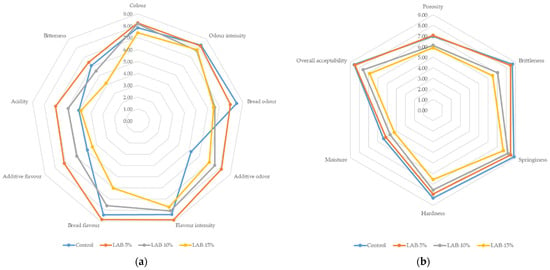

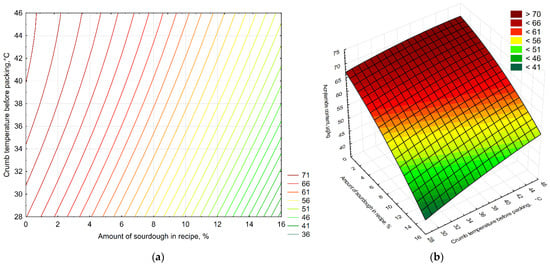

The results of the study of acrylamide levels in various samples of control bread and bread with varying amounts of sourdough, packaged at different crumb temperatures in polyethylene packaging, are presented in Figure 4. The second-order polynomial equation obtained for acrylamide content (Z) as a function of packaging temperature (X) and sourdough concentration (Y) was Z = 48.6155−1.9145x + 0.947y − 0.0355x2 + 0.0296xy − 0.0103y2. The model showed a good fit to the experimental data (R2 = 0.987), indicating that both factors significantly affected acrylamide formation. As the amount of L. plantarum-based sourdough increased, a decrease in acrylamide was observed in the experimental bread samples compared to the control samples (by 19.4%, 21.3%, and 35.3% less for 5%, 10%, and 15% sourdough, respectively), which is consistent with the data of Bartkiene et al., who showed a statistically significant decrease in acrylamide with an increase in LAB dosage to 20% [35]. The lowest acrylamide content was found in the sample with 15% sourdough, packaged at a crumb temperature of 30 °C (35.2% less acrylamide than the control bread). Similar results were obtained by Lopez-Moreno et al., where the use of LAB led to a significant reduction in acrylamide levels [56]. The highest content was found in 5% sourdough bread packaged at 45 °C (4.02% less acrylamide than the control bread). When comparing the results taking both factors into account, it becomes clear that using more sourdough in the recipe reduces acrylamide in bread.

Figure 4.

A two-factor model reflecting the influence of the amount of sourdough in the recipe (X-axis, %) and the temperature of the crumb before packaging (Y-axis, °C) on the acrylamide content in bread (Z-axis, µg/kg): the (a) contour plot and (b) surface response plot. The color zones show the magnitude of the response: cool shades (green) correspond to low acrylamide values, warm shades (yellow/red) to high values. The numbers on the axes correspond to the levels of the factors: 0 (control), 5, 10, and 15% sourdough; 30, 40, and 45 °C for crumb temperature before packaging.

The reduction in acrylamide content in sourdough bread can be explained by several biochemical mechanisms associated with LAB metabolism. L. plantarum actively metabolizes free amino acids, especially asparagine—the main precursor of acrylamide formation through the Maillard reaction. During fermentation, LABs consume asparagine as a nitrogen source, thereby decreasing its availability for reaction with reducing sugars and subsequently limiting acrylamide formation during baking [26].

In addition, LAB fermentation promotes the production of organic acids (mainly lactic and acetic), which not only lower pH but also influence the Maillard reaction kinetics by reducing the reactivity of carbonyl groups. Acidic conditions favor the protonation of carbonyl intermediates, decreasing their ability to react with amino groups and form Schiff bases, thus inhibiting the initial steps of the carbonyl–amine pathway leading to acrylamide [57].

Investigation on the effects of sourdough level and packaging temperature on acrylamide content in bread is shown in Table 6. When assessing the effect of the amount of sourdough at each packaging temperature, it was found that all factors had a significant effect at each level (F = 78.99; p = 0.0003 for 30 °C; F = 71.13; p = 0.0004 for 40 °C; F = 92.79; p = 0.0002 for 45 °C, respectively). A significant effect of packaging temperature was found at any level of sourdough (F = 107.68; p = 0.0001 for 5% sourdough; F = 41.17; p = 0.0012 for 10% sourdough; F = 22.47; p = 0.0041 for 15% sourdough, respectively). The effect of crumb temperature at the time of packaging (30–45 °C) on acrylamide levels is related to post-baking physicochemical processes. At 40–45 °C, a zone of increased humidity is created inside the polyethylene packaging due to active condensation of vapor on the inner surface. This moisture increases the water activity in the crumb and simultaneously limits oxygen diffusion, which can alter the course of secondary Maillard reactions. A moderate negative correlation was established between bread moisture and acrylamide content (r = −0.719; p = 0.029). Awulachew et al. noted that residual acrylamide in bakery products is chemically unstable and decreases during warm storage (20–40 °C) [22]. Dessev et al. noted that packaging hot bread leads to higher levels of acrylamide due to a combination of residual heat and moisture, which accelerates the interaction of asparagine with reducing sugars even after baking is complete [23]. At a packaging temperature of 30 °C, the intensity of moisture release and the reaction rate decrease, which limits post-baking acrylamide formation and promotes its partial degradation or binding with other compounds. Recent studies suggest that water activity and intra-package microclimate are critical factors influencing residual acrylamide levels in stored bakery products, as acrylamide formation increases at lower water activity (aw) and during storage under higher temperature/humidity gradients [58].

Table 6.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the effects of sourdough level and packaging temperature on acrylamide content in bread.

The effect of packaging temperature on the dynamics of acrylamide content after baking should be considered in conjunction with changes in aw. A decrease in aw usually slows down the diffusion of reagents and reduces the rate of many stages of the Maillard reaction, but in the range of moderately low aw, the maximum rate of formation of some intermediate products is observed due to the optimization of the concentrations of reacting species [59]. For bread, where aw and moisture distribution change during storage and at different packaging temperatures, this means that there are competing processes: the kinetic constants for acrylamide formation may decrease due to reduced reagent mobility, but at the same time, the relative proportion of pathways leading to acrylamide formation from already formed intermediates may increase. Therefore, the dynamics of acrylamide reduction at packaging temperatures of 30–45 °C observed in our work can be adequately explained by a combination of the temperature effect on Maillard reaction rates and changes in aw in the grain/crumb matrix. Early kinetic studies clearly showed the sensitivity of acrylamide formation/elimination rates to aw and temperature, confirming the need to include these parameters in the interpretation of the results [60].

It is important to note that all acrylamide values obtained in the samples tested were below the reference levels set by Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/2158 (50 µg/kg for soft wheat bread and 100 µg/kg for other types of bread). However, the temperature of the packaging was found to have an effect on the residual acrylamide content: when bread was packaged at 40–45 °C, its concentration was higher than at 30 °C. This indicates that, although L. plantarum-based recipes meet European requirements, choosing the optimal packaging temperature (30 °C) further minimizes acrylamide levels and thus enhances food safety.

3.6. The Effect of Lactiplantibacillus planatrum in Wheat Bread on Preventing Mold Spoilage

To assess the effect of LAB on preventing mold spoilage, polyethylene bags were used as packaging material, as they are the most readily available type of material for transporting food products. The effect of packaging temperature on bread with different amounts of sourdough during storage is shown in Table 7. Visible mold colonies were observed on the surface of the control bread samples at packaging temperatures of 45 °C and 40 °C on day 3. The first mold colonies on the experimental samples at high crumb temperature were detected on the 4th day for 5% sourdough and on the 5th day for bread using 10% and 15% sourdough, respectively. It was noted that the use of LAB contributes to slowing down the microbiological spoilage of bread in comparison with the control samples [61]. Also, the inclusion of a larger amount of sourdough in the bread baking process increases the shelf life of the product regardless of the packaging temperature [32].

Table 7.

The influence of different quantities of wheat sourdough and packaging temperature on shelf life of wheat bread. Samples were stored at 24 ± 2 °C.

In addition, it is worth noting that airtight packaging materials, such as plastic bags, contribute to increased condensation as the temperature of the packaging rises, which accelerates the spoilage of bread [62]. The use of various additional processing methods, such as plant-based antifungal coatings or extracts, has been shown to further increase the shelf life of bread by inhibiting fungal growth and moisture migration [63].

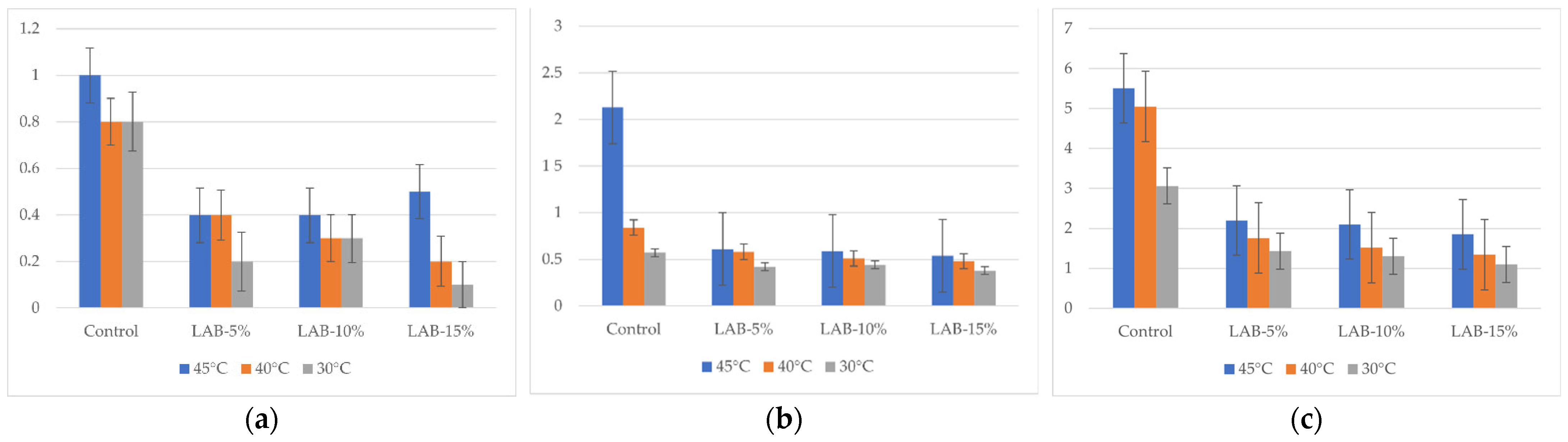

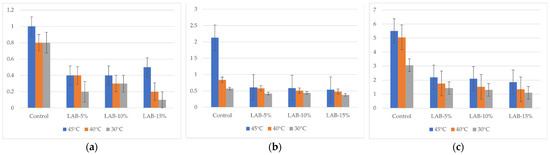

The results of the study on the total mesophilic aerobic and facultative anaerobic microorganisms (TMAFAMs) by day are shown in Figure 5. The values represent the microbial load measured in CFU/g. Microbiological analysis showed that with an increase in storage time (from 1 to 5 days), there was an increase in TMAFAMs and mold count in all samples, but the intensity of growth depended on the presence of sourdough and packaging temperature.

Figure 5.

Total mesophilic aerobic and facultative anaerobic microorganisms of bread samples during storage. LAB-5, LAB-10, and LAB-15 correspond to breads prepared with 5%, 10%, and 15% sourdough fermented with L. plantarum, respectively. Y-axis—total mesophilic aerobic and facultative anaerobic microorganisms: (a) after 24 h, 101 CFU/g; (b) after 72 h, 103 CFU/g; (c) after 120 h, 103 CFU/g.

In control samples without L. plantarum, TMAFAM values reached 5.51 × 103 CFU/g (B-C-45°) by day 5, and mold counts reached 83 CFU/g, which exceeds the requirements of TR CU 021/2011 (≤1 × 103 CFU/g and ≤50 CFU/g, respectively) [64]. This indicates that the shelf life of bread without sourdough under the conditions studied does not comply with sanitary standards.

The introduction of L. plantarum sourdough significantly slowed down the growth of microflora: thus, with 15% sourdough and packaging at 30 °C, the amount of TMAFAMs on the 5th day was only 1.1 × 103 CFU/g, and the amount of mold was 44 CFU/g, which complies with the requirements of TR CU 021/2011 [64]. Thus, even on the 5th day of storage, bread with sourdough retained satisfactory sanitary and hygienic indicators.

The reduction in microbiological spoilage in samples with sourdough can be explained by the synergistic action of L. plantarum: acidification of the dough and formation of organic acids (lactic, acetic) that inhibit mold growth; synthesis of bacteriocins and antagonistic activity against undesirable microorganisms; and possible binding of nutrient substrates, limiting the growth of competitive microflora.

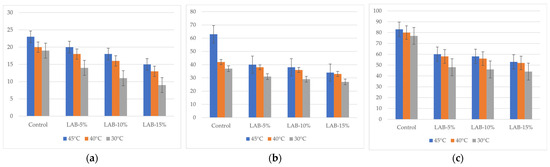

The packaging temperature also had a significant effect. Higher temperatures (40–45 °C) promoted accelerated mold growth in the control samples, while in the samples with LAB, the negative effect was mitigated. The most pronounced antimicrobial effect was observed when packaged at 30 °C, especially at high sourdough levels (10–15%), where microbiological indicators remained within the limits of TR CU 021/2011 even on the 5th day of storage [64]. Thus, L. plantarum-based sourdough not only contributes to the reduction in acrylamide but also increases the shelf life of bread, ensuring that microbiological indicators comply with the requirements of technical regulations. The analysis of the fungal content of the bread samples is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Changes in mold counts in bread samples during storage. LAB-5, LAB-10, and LAB-15 correspond to breads prepared with 5%, 10%, and 15% sourdough fermented with L. plantarum, respectively. Y-axis—total mold counts: (a) after 24 h, CFU/g; (b) after 72 h, CFU/g; (c) after 120 h, CFU/g.

It should be noted that the use of environmentally friendly materials, such as paper packaging at bread temperatures of 30–45 °C, has both advantages and limitations. Unlike plastic bags, paper allows gas exchange and reduces the risk of moisture condensation, which can slow down mold growth during storage [32]. However, the increased moisture permeability of paper leads to accelerated weight loss and drying of bread, especially if it is packaged while still warm (above 30 °C). Various studies showed that plastic bags are better at maintaining the softness and moisture of bread, while paper promotes staling [65]. Thus, paper packaging may be useful for reducing microbiological spoilage at room temperature, but it is not more effective than plastic for preserving the textural characteristics of bread. To optimize product quality, a combined approach is recommended—the use of laminated paper or multilayer biopolymer materials that simultaneously limit condensation and retain moisture. However, when using this material, it is important to pay attention to the preservation of product characteristics during storage, as bread loses its moisture more quickly in paper packaging [66]. A pressing issue is the migration of heavy metals from food-grade paper packaging, which is of concern to countries around the world seeking to ensure food safety throughout the storage period [67].

4. Conclusions

Scientific significance: For the first time, the combined effect of the sourdough level (optimally 5% and 10%) and the crumb temperature during packaging (30 °C) on the minimization of acrylamide formation and the dynamics of microbiological spoilage has been quantitatively substantiated. It was demonstrated that reducing the packaging temperature to 30 °C significantly inhibits moisture condensation, acting as a key factor in prolonging shelf life up to 7 days, which exceeds the effect achieved by sourdough alone (3–4 days).

Industrial applicability: The obtained results offer a ready-to-implement strategy for bakery enterprises. Applying 5–10% Lactobacillus plantarum sourdough in combination with controlling crumb temperature at 30 °C before packaging enables the production of wheat bread with improved safety characteristics (reduced acrylamide), extended shelf life, and maintained organoleptic quality. An additional benefit is the enhancement of crumb properties, including increased moisture content and resistance to deformation.

Limitations and future perspectives: The results have not yet been validated under industrial-scale conditions, which is required to confirm process stability and economic feasibility. Future research will focus on conducting pilot-scale trials to verify optimal operational parameters and assess the consistency of the process in continuous production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: U.T. and A.Z.; methodology: U.T., A.Z. and Z.I.; software: A.Z. and S.A. (Sagynysh Aman); validation: F.A. and S.A. (Sholpan Amanova); formal analysis: U.T. and A.Z.; investigation: U.T. and A.Z.; resources: U.T. and A.Z.; data curation: A.Z., F.A. and S.A. (Sagynysh Aman); writing—preparation of the initial draft: U.T., A.Z. and Z.I.; reviewing and editing: U.T., M.M. and B.A.; visualization: U.T. and Z.I.; supervision: U.T., Z.I. and R.U.; project administration: R.U., M.I. and R.I.; obtaining funding: U.T., R.I. and M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Farida Amutova was employed by the company LLP “Scientific and Production Enterprise Antigen”. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- ElDala.kz. The Wheat Harvest in Kazakhstan Amounted to 17 Million Tons. 8 November 2024. Available online: https://eldala.kz/novosti/ehlevatory/20543-urozhay-pshenicy-v-kazahstane-sostavil-17-mln-tonn (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Engindeniz, S.; Bolatova, Z. A study on consumption of composite flour and bread in global perspective. Br. Food J. 2019, 123, 1962–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-L.; Han, K.-N.; Feng, G.-X.; Wan, Z.-L.; Wang, G.-S.; Yang, X.-Q. Salt reduction in bread via enrichment of dietary fiber containing sodium and calcium. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 2660–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistics Bureau of the Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan. 13 April 2023. On Food Consumption in Households in 2022. Available online: https://stat.gov.kz/ru/news/o-potreblenii-produktov-pitaniya-v-domashnikh-khozyaystvakh-v-2022-godu-/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Agama-Acevedo, E.; Pacheco-Vargas, G.; Gutierrez-Meraz, F.; Tovar, J.; Bello-Perez, L.A. Dietary fiber content, texture, and in vitro starch digestibility of different white bread crusts. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 89, 102824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesta-Corral, M.; Gómez-García, R.; Balagurusamy, N.; Torres-León, C.; Hernández-Almanza, A.Y. Technological and Nutritional Aspects of Bread Production: An Overview of Current Status and Future Challenges. Foods 2024, 13, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebholz, G.F.; Sebald, K.; Dirndorfer, S.; Dawid, C.; Hofmann, T.; Scherf, K.A. Impact of exogenous α-amylases on sugar formation in straight dough wheat bread. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 247, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarion, C.; Codină, G.G.; Dabija, A. Acrylamide in Bakery Products: A Review on Health Risks, Legal Regulations and Strategies to Reduce Its Formation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batuwita, B.K.H.H.; Jayasinghe, J.M.J.K.; Marapana, R.A.U.J.; Jayasinghe, C.V.L.; Jinadasa, B.K.K.K. Reduction of Asparagine; Reducing Sugar Content; Utilization of Alternative Food Processing Strategies in Mitigating Acrylamide Formation—A Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 18, 2101–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC. Some industrial chemicals. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans 60; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Edna Hee, P.-T.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Fang, Z. Formation mechanisms, detection methods and mitigation strategies of acrylamide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heterocyclic amines in food products. Food Control 2024, 158, 110236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraju, I.; Sana, M.; Chakraborty, I.; Rahman, H.; Biswas, R.; Mazumder, N. Dietary Acrylamide: A Detailed Review on Formation, Detection, Mitigation, and Its Health Impacts. Foods 2024, 13, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM). Scientific Opinion on acrylamide in food. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/2158 of 20 November 2017 Establishing Mitigation Measures and Benchmark Levels for the Reduction of the Presence of Acrylamide in Food; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Codex Alimentarius Commission. CAC/RCP 67-2009. General Principles of Food Hygiene; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gazi, S.; Göncüoğlu Taş, N.; Görgülü, A.; Gökmen, V. Effectiveness of asparaginase on reducing acrylamide formation in bakery products according to their dough type and properties. Food Chem. 2023, 402, 134224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Jiang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, P.; Lu, Z.; Lu, F. Thermal Stability Enhancement of L-Asparaginase from Corynebacterium glutamicum Based on a Semi-Rational Design; Its Effect on Acrylamide Mitigation Capacity in Biscuits. Foods 2023, 12, 4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.A.; Abdelhady, M.M.; Jaafari, S.A.; Alanazi, T.M.; Mohammed, A.S. Impact of Some Enzymatic Treatments on Acrylamide Content in Biscuits. Processes 2023, 11, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, N.S.; Tehrani, M.M.; Khodaparast, M.H.H.; Farhoosh, R. Effect of temperature, time, and asparaginase on acrylamide formation and physicochemical properties of bread. Acta Aliment. 2019, 48, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Food Enzymes (FEZ); Zorn, H.; Barat Baviera, J.M.; Bolognesi, C.; Catania, F.; Gadermaier, G.; Greiner, R.; Mayo, B.; Mortensen, A.; Roos, Y.H.; et al. Safety evaluation of the food enzyme asparaginase from the non-genetically modified Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain ARY-2. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codină, G.G.; Sarion, C.; Dabija, A. Effects of Dry Sourdough on Bread-Making Quality; Acrylamide Content. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awulachew, M.T. Bread deterioration; a way to use healthful methods. CyTA J. Food 2024, 22, 2424848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessev, T.; Lalanne, V.; Keramat, J.; Jury, V.; Prost, C.; Le-Bail, A. Influence of Baking Conditions on Bread Characteristics and Acrylamide Concentration. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Res. 2020, 3, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungyshbayeva, U.; Mannino, S.; Uazhanova, R.; Adilbekov, M.A.; Yakiyayeva, M.A.; Kazhymurat, A. Development of a methodology for determining the critical limits of the critical control points of the production of bakery products in the Republic of Kazakhstan. East. -Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2021, 3, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulea Fekensa, W. The Effect of Traditional Sourdough Starter Culture; Involved Microorganisms on Sensory; Nutritional Quality of Whole Wheat Bread. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2021, 9, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Duan, M.; Gao, S.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y. A strategy for reducing acrylamide content in wheat bread by combining acidification rate; prerequisite substance content of Lactobacillus; Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 5, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameur, H.; Tlais, A.Z.A.; Paganoni, C.; Cozzi, S.; Suman, M.; Di Cagno, R.; Gobbetti, M.; Polo, A. Tailor-made fermentation of sourdough reduces the acrylamide content in rye crispbread and improves its sensory and nutritional characteristics. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 410, 110513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, M.; Ozgolet, M.; Cankurt, H.; Dertli, E. Harnessing the Role of Three Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Strains for Type II Sourdough Production; Influence of Sourdoughs on Bread Quality; Maillard Reaction Products. Foods 2024, 13, 1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyaci Gunduz, C.P. Formulation; Processing Strategies to Reduce Acrylamide in Thermally Processed Cereal-Based Foods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 6272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Figueroa, R.H.; Mani-López, E.; Ramírez-Corona, N.; López-Malo, A. Optimizing Lactic Acid Bacteria Proportions in Sourdough to Enhance Antifungal Activity; Quality of Partially; Fully Baked Bread. Foods 2024, 13, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mou, T.; Xu, R.; Li, Q.; Li, J.; Liu, S.; Ao, X.; Chen, S.; Liu, A. Screening of Antifungal Lactic Acid Bacteria; Their Impact on the Quality; Shelf Life of Rye Bran Sourdough Bread. Foods 2025, 14, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I.E.; Shittu, T.A.; Onabanjo, O.O.; Adesina, A.D.; Soares, A.G.; Okolie, P.I.; Kupoluyi, A.O.; Ojo, O.A.; Obadina, A.O. Effect of packaging materials and storage conditions on the microbial quality of pearl millet sourdough bread. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 58, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauvain, S. Technology of Breadmaking; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseney, R.C. Principles of Cereal Science and Technology; American Association of Cereal Chemists: St Paul, MN, USA, 1994; pp. 155–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bartkiene, E.; Jakobsone, I.; Juodeikiene, G.; Vidmantiene, D.; Pugajeva, I.; Bartkevics, V. Study on the reduction of acrylamide in mixed rye bread by fermentation with bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances producing lactic acid bacteria in combination with Aspergillus niger glucoamylase. Food Control 2013, 30, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AACC International. AACC Method 10-05.01. Guidelines for Measurement of Volume by Rapeseed Displacement; American Association of Cereal Chemists: St Paul, MN, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- GOST 5669-96; Bakery Products. Method for Determining Porosity. KazStandard: Astana, Republic of Kazakhstan, 1996.

- GOST 21094-2022; Bakery Products. Methods for Determining Moisture Content. KazStandard: Astana, Republic of Kazakhstan, 2022.

- ISO 8586:2023; Sensory Analysis. Selection and Training of Sensory Assessors. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO 11136:2014; Sensory Analysis. Methodology. General Guidance for Conducting Hedonic Tests with Consumers in a Controlled Area. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- GOST 10444.15-94; Food Products. Methods for Determining Total Mesophilic Aerobic and Facultative Anaerobic Microorganisms. Committee of the Russian Federation for Standardization, Metrology and Certification: Moscow, Russia, 1995.

- GOST 10444.12-2013; Food Products. Methods for Detection and Colony Count of Yeasts and Moulds. Interstate Council for Standardization, Metrology and Certification: Minsk, Belarus, 2013.

- Silva, J.D.R.; Rosa, G.C.; Neves, N.d.A.; Leoro, M.G.V.; Schmiele, M. Production of sourdough; gluten-free bread with brown rice; carioca; cowpea beans flours: Biochemical, nutritional; structural characteristics. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e303101623992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Danial, M.; Liu, L.; Sadiq, F.A.; Wei, X.; Zhang, G. Effects of Co-Fermentation of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae on Digestive and Quality Properties of Steamed Bread. Foods 2023, 12, 3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Alvarado, O.; Zepeda-Hernández, A.; Garcia-Amezquita, L.E.; Requena, T.; Vinderola, G.; García-Cayuela, T. Role of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts in sourdough fermentation during breadmaking: Evaluation of postbiotic-like components and health benefits. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 969460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Islam, S. Sourdough Bread Quality: Facts and Factors. Foods 2024, 13, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, W.; Xu, K.; Long, L.; Ye, H. Study on Moisture Phase Changes in Bread Baking Using a Coupling Model. Foods 2025, 14, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramari, S.; Nouska, C.; Hatzikamari, M.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Lazaridou, A. Impact of Sourdough from a Commercial Starter Culture on Quality Characteristics; Shelf Life of Gluten-Free Rice Breads Supplemented with Chickpea Flour. Foods 2024, 13, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontonio, E.; Perri, G.; Calasso, M.; Celano, G.; Verni, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Unveiling the impact of traditional sourdough propagation methods on the microbiological, biochemical, sensory, and technological properties of sourdough and bread: A comprehensive first study. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, E.; Arici, M.; Durak, M.Z. Effect of starter culture sourdough prepared with Lactobacilli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae on the quality of hull-less barley-wheat bread. LWT 2021, 152, 112230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temkov, M.; Rocha, J.M.; Rannou, C.; Ducasse, M.; Prost, C. Influence of baking time; formulation of part-baked wheat sourdough bread on the physical characteristics, sensory quality, glycaemic index; appetite sensations. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, J.S.; Farage, P.; Zandonadi, R.P.; Botelho, R.B.A.; de Oliveira, L.d.L.; Raposo, A.; Shakeel, F.; Alshehri, S.; Mahdi, W.A.; Araújo, W.M.C. A Systematic Review on Gluten-Free Bread Formulations Using Specific Volume as a Quality Indicator. Foods 2021, 10, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.H.L.; Monteiro, R.L.; Salvador, A.A.; Laurindo, J.B.; Carciofi, B.A.M. Kinetics of bread physical properties in baking depending on actual finely controlled temperature. Food Control 2022, 137, 108898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello-Olmo, M.; Krishnan, P.G.; Araña, M.; Oneca, M.; Díaz, J.V.; Barajas, M.; Rovai, M. Development, Analysis, and Sensory Evaluation of Improved Bread Fortified with a Plant-Based Fermented Food Product. Foods 2023, 12, 2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seis Subaşı, A.; Ercan, R. Technological characteristics of whole wheat bread: Effects of wheat varieties, sourdough treatments and sourdough levels. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 2593–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Moreno, C.; Fernández-Palacios, S.; Ramírez Márquez, P.; Ramírez Márquez, S.J.; Ramírez Montosa, C.; Carlos Otero, J.; López Navarrete, J.T.; Ponce Ortiz, R.; Ruíz Delgado, M.C. Assessment of Acrylamide Levels and Evaluation of Physical Attributes in Bread Made with Sourdough and Prolonged Fermentation. Food Sci. Eng. 2023, 5, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fhoula, I.; Dammak, I.; Nachi, I.; Smida, I.; Hassouna, M.; Ouzari, I.H. Bread-Making Quality; Reduction of Acrylamide Content Using Weissella confusa Strain V20 from Desert Plant Stipagrostis pungens as Sourdough Additive. Fermentation 2024, 10, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, A.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Q.; Jia, C.; Zhao, S.; Liu, R.; Rong, J.; Zhou, G.; Wang, B.; Kuai, J.; et al. Acrylamide and Advanced Glycation End Products in Frying Food: Formation, Effects, and Harmfulness. Foods 2025, 14, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Wang, W.; Yang, T.; Ding, W.; Xu, B. Maillard Reaction in Flour Product Processing: Mechanism, Impact on Quality, and Mitigation Strategies of Harmful Products. Foods 2025, 14, 2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, X.; Nan, S.; Zeng, X.; Kang, L.; Liu, X.; Dai, Y. Inhibition Kinetics and Mechanism of Glutathione and Quercetin on Acrylamide in the Low-Moisture Maillard Systems. J. Food Prot. 2021, 84, 984–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quattrini, M.; Liang, N.; Fortina, M.G.; Xiang, S.; Curtis, J.M.; Gänzle, M. Exploiting synergies of sourdough and antifungal organic acids to delay fungal spoilage of bread. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 302, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadrach, O.A.; Omolara, J.O.; Monsi, B. Storage environment/packaging materials impacting bread spoilage under ambient conditions: A comparative analysis. Chem. Int. 2020, 6, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Islam, R.; Hasan, S.; Zzaman, W.; Rana, M.R.; Ahmed, S.; Roy, M.; Sayem, A.; Matin, A.; Raposo, A.; et al. A Comprehensive Review on Bio-Preservation of Bread: An Approach to Adopt Wholesome Strategies. Foods 2022, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurasian Economic Commission. Technical Regulation of the Customs Union TR CU 021/2011 on Food Safety; Eurasian Economic Commission: Moscow, Russia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mizielińska, M.; Kowalska, U.; Tarnowiecka-Kuca, A.; Dzięcioł, P.; Kozłowska, K.; Bartkowiak, A. The Influence of Multilayer, “Sandwich” Package on the Freshness of Bread after 72 h Storage. Coatings 2020, 10, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpers, T.; Kerpes, R.; Frioli, M.; Nobis, A.; Hoi, K.I.; Bach, A.; Jekle, M.; Becker, T. Impact of Storing Condition on Staling and Microbial Spoilage Behavior of Bread and Their Contribution to Prevent Food Waste. Foods 2021, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhanbolat, A.; Tungyshbayeva, U.; Uazhanova, R.; Nabiyeva, Z.; Yakiyayeva, M.; Samadun, A. Evaluating heavy metal contamination in paper-based packaging for bakery products: A HACCP approach. Potravin. Slovak. J. Food Sci. 2024, 18, 819–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).