Abstract

Although the influence of raw material composition on soy sauce koji fermentation is well recognized, the differences in microbial succession and metabolic pathways between whole soybean koji (WSK) and defatted soybean–wheat bran koji (DSK) remain unclear. In this study, a multi-omics approach integrating absolute quantitative PCR and physicochemical analyses was employed to elucidate the mechanisms by which DSK enhances the quality of Deyang Baiwo soy sauce. Compared with WSK, DSK exhibited lower moisture content but higher total acidity, amino nitrogen, and reducing sugar levels, indicating its suitability for high-quality soy sauce production. Volatile analysis revealed greater accumulation of key aroma compounds such as 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol and 4-vinylguaiacol in DSK, contributing characteristic smoky flavors. At the microbial community level, Aspergillus, Weissella, Enterobacter, and Bacillus were enriched in DSK, promoting the accumulation of flavor and aroma compounds in alignment with industrial koji production objectives. Metabolic pathway analysis indicated that Weissella in DSK was primarily responsible for lactic acid accumulation, whereas Aspergillus dominated early-stage substrate degradation and played a key role in the enrichment of 1-octen-3-ol in WSK. This study provides insights into the “substrate–microbiota–metabolite” regulatory network and offers a theoretical basis for optimizing the use of defatted soybean in traditional soy sauce fermentation.

1. Introduction

Deyang Baiwo (DB) soy sauce, originating from Sichuan, China, has a long history and is renowned for its bright color, rich aroma, and mellow taste. Its traditional production involves two key stages, i.e., koji fermentation and moromi fermentation [1]. During koji fermentation, the most critical step, diverse microorganisms proliferate and produce abundant hydrolytic enzymes and flavor precursors, which ultimately determine the yield and sensory quality of the final product [2,3]. However, the selection of raw materials plays a pivotal role in shaping the flavor profile and nutritional composition of the final product [4]. Traditionally, whole soybeans have been used as the core ingredient in soy sauce production due to their rich nutritional composition, including lipids (19.9%), carbohydrates (30%), and plant-based proteins (36.5%) [5]. However, the use of whole soybeans in koji making poses several challenges, including high production costs, lipid interference with fermentation, and difficulties in handling fermentation residues [6]. Defatted soybean, a by-product of oil extraction with high protein, low fat, and abundant dietary fiber, has shown considerable potential as a substitute in koji production [7]. Partial or complete replacement of whole soybeans with defatted soybeans can reduce lipid interference, optimize the microbial metabolic environment, lower production costs, and contribute to more efficient and sustainable soy sauce fermentation.

The distinctive flavor of soy sauce results from a complex combination of volatile compounds, which contribute to its aroma, and non-volatile compounds, such as amino acids, peptides, and organic acids, which are responsible for its characteristic umami, salty, and slightly sweet or sour tastes [8,9,10]. More than 300 aromatic compounds have been identified in soy sauce to date, predominantly including alcohols, aldehydes, acids, esters and phenols [11]. However, the composition of these aroma compounds can vary considerably depending on the raw materials, salt concentration, and microbial strains employed [12]. For instance, soy sauce made from whole soybeans typically contains a greater abundance of fatty acid esters and exhibits a milder flavor, owing to the higher crude fat content of the beans, compared to that produced from defatted soybeans [13,14]. In addition, wheat bran is regarded as superior to wheat flour, as its ferulic acid content can be converted during fermentation into methoxyphenols, including 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol, 4-vinylguaiacol, and 4-ethylguaiacol [15]. Given these findings, a comprehensive investigation into how differences in raw materials influence flavor compound formation and mechanisms is essential.

During the production of soy sauce koji, the fermentation process is driven by a complex microbial community, including the inoculated Aspergillus strain, which exerts a critical influence on the flavor and quality of the final koji product [16]. Due to differences in raw material composition and microbial interactions, the structure, succession, and functional roles of microbial communities differed between the two fermentation substrates, ultimately leading to distinct metabolic profiles. In recent years, the microbial succession within soy sauce koji has been gradually elucidated, revealing a typical progression involving Aspergillus, Weissella, Bacillus, and Enterococcus. The metabolic functions of these microorganisms have also become increasingly well characterized. For instance, Aspergillus is known to secrete a complex array of enzymes, including amylases, proteases, lipases, and glutaminases, which can hydrolyze starches and proteins in the raw materials into short-chain sugars and amino acids, while also producing aromatic compounds and their precursors, such as organic acids, alcohols, and esters [17,18,19]. Weissella, a common acid-producing bacterium in koji, contributes to carbohydrate degradation into monosaccharides and organic acids, resulting in decreased pH and promoting the formation of aroma-related compounds such as phenylacetaldehyde and ethyl acetate [20]. Bacillus species are capable of degrading starch, proteins, and lipids through the secretion of relevant enzymes, and during high-temperature koji fermentation, they mainly produce acetic acid, malic acid, and propionic acid [21,22]. Enterococcus, frequently detected in fermented soy products, exhibits strong glycolytic, lipolytic, and proteolytic activities [17]. Although previous studies have explored the influence of raw material components such as soybean and defatted soybean on flavor and taste [5], a detailed comparison of microbial community structures between koji made from whole soybeans and defatted soybeans remains lacking. Thus, more comprehensive studies are urgently required to clarify these differences and their impact on fermentation efficiency and flavor formation.

This study systematically compared the physicochemical properties, flavor compounds, and microbial community structures during koji preparation using whole and defatted soybeans in DB soy sauce. The aim was to elucidate the key mechanisms by which defatted soybeans enhance soy sauce quality. Metabolic pathways related to macromolecule hydrolysis and flavor formation were reconstructed to reveal microbial functional differentiation, providing a basis for raw material substitution, process optimization, and the selection of locally adapted functional strains.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

The koji fermentation was conducted in March 2024 at Deyang Seasoning Food Co., Ltd. (Deyang, China). Except for WSK, in which soybeans were pre-soaked for several hours, all raw materials were directly mixed and pressure-steamed for 8 min. After steaming, a 1:1 mixture of starters A and B was applied. In WSK, the ratio of soybeans to starter was 2.6:0.03 (w/w), whereas in DSK, defatted soybeans, wheat, wheat bran, and starter were mixed at 1.6:0.8:0.2:0.03 (w/w). Inoculation was performed at 38–40 °C, after which the materials were transferred to the koji bed and fermented at 30–32 °C for 48 h. Samples were randomly collected at five key time points: steaming, inoculation (0 h), first turning (24 h), second turning (36 h), and the final product (48 h). Four raw materials (soybeans, defatted soybeans, wheat, and wheat bran) and both starters A and B were also collected. Both starters A and B were commercial preparations of Aspergillus oryzae 3.042. A mixed inoculum of starters A and B was employed to improve yield and flavor development. At each sampling point, 500 g samples were obtained from three independent batches and immediately stored at −80 °C. In total, 48 samples were collected, including 12 raw material samples (4 types × 3 batches), 6 starter samples (2 types × 3 batches), and 30 soy sauce koji samples (10 types × 3 batches).

2.2. Analysis of Physicochemical Parameters

The moisture content was measured using a gravimetric method by drying a koji sample to a constant weight at 105 °C (about 6 h). The pH, titratable acidity (TA), amino acid nitrogen (AN), and reducing sugar (RS) were detected based on previous studies [23].

2.3. Analysis of Volatile Compounds (VCs), Free Amino Acids (FAAs), and Organic Acids (OAs)

The VCs were extracted and analyzed using headspace solid-phase microextraction/gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (HS-SPME/GC-MS) according to our previous report [24] with some modifications. Briefly, 0.5 g of mash sample was mixed with 10 mL of saturated NaCl solution in a 20 mL headspace bottle, and 2 μL of 0.08 μg/μL 2-octanol solution was added as an internal standard. The 50/30 μm DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) was used to extract the volatiles at 55 °C for 35 min with a 20 rpm stirring speed of the sample solution. The VCs were detected by GC-MS (Shimadzu GCMS-QP2010 SE, Kyoto, Japan) with a VF-WAXms column (60 m length, 0.25 mm internal diameter, 0.25 μm film thickness, Agilent J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA, USA). The constant flow rate of the carrier gas, ultrahigh-purity helium (99.999%), was 1.0 mL/min. The inlet temperature was 250 °C, and the desorption time was 5 min. The temperature program of GC was as follows: the starting temperature was held at 40 °C for 3.5 min, heated to 60 °C at 5 °C/min, heated to 230 °C at 8 °C/min, and then held for 9 min. The interface and ion source temperatures were set at 235 and 220 °C, respectively. The ionization mode was electron ionization (EI) at 70 V and 60 μA. The compounds, covering a range of m/z 33–400 in full scan, were identified by aligning mass spectral data against the NIST-17 mass spectral database.

A total of 21 FAAs were quantified via ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) by Shanghai Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). They included 20 standard proteinogenic amino acids and hydroxyproline, following established reference methods [25]. Briefly, 20 mg of freeze-dried koji was mixed with 212 μL of ultrapure water, 25 μL of 0.15% DOC, and 8 μL of internal standard solution (100 μg/mL), and the mixture was subjected to ultrasonic extraction at 5 °C for 10 min. Subsequently, 5 μL of 10 M TCA was added, and the solution was stored at −20 °C for 10 min before being centrifuged at 14,000 rcf and 4 °C for 10 min. An aliquot of 25 μL of the supernatant was diluted with 375 μL of water, filtered through a 0.2 μm PTFE membrane, and then analyzed. FAAs were separated using an AdvanceBio MS Spent Media column (2.1 mm × 50 mm, 2.7 μm; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at 40 °C, with an injection volume of 1 μL. The mobile phases consisted of 95% water containing 0.1% formic acid and 10 mM ammonium formate (phase A) and 95% acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid and 10 mM ammonium formate (phase B). Mass spectrometric detection was conducted in both positive and negative ESI modes under the following conditions: CUR 35 psi, CAD medium, IS +5500/−4500 V, source temperature 550 °C, GS1 50 psi, and GS2 50 psi. Scheduled-MRM analysis (120 s window) was employed. All 21 FAAs exhibited excellent calibration linearity (R2 > 0.99). The limits of detection for individual amino acids (S/N ≈ 3, R2 > 0.99) are provided in Table S1. Quantitative analysis of 7 OAs was performed using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a 1260 Infinity II system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Separation was achieved using an Athena C18-WP column (4.6 mm × 250 mm, 5 μm; Anpel Laboratory Technologies Inc., Shanghai, China). The analytical method was adapted with minor modifications from a previously published protocol [26]. Briefly, 2 g of koji was placed in a 50 mL centrifuge tube and mixed with 20 mL of ultrapure water, followed by ultrasonic-assisted extraction for 20 min. An aliquot of 1.5 mL of the extract was transferred to a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 1 min. Then, 1.2 mL of the supernatant was transferred to a new 1.5 mL tube, and 0.15 mL of potassium ferrocyanide solution (106 g/L) and 0.15 mL of zinc sulfate solution (300 g/L) were added for protein precipitation. The mixture was vortexed thoroughly and centrifuged again at 10,000 rpm for 1 min. The resulting supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane into an HPLC vial for analysis. OAs were separated and quantified using HPLC equipped with a CNW Athena C18-WP column at 30 °C. The mobile phase was 0.02 mol/L NaH2PO4 (pH 2.7) at a flow rate of 0.7 mL/min, with an injection volume of 10 μL and detection at 210 nm. Identification and quantification were performed based on established standard curves for OAs, and all analyses were conducted in triplicate.

2.4. Total DNA Extraction, Absolute Quantification PCR, and High-Throughput Sequencing

Total genomic DNA was extracted using the Omega Soil DNA Kit (Omega Biotek, Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA integrity was confirmed via 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis, its concentration was determined by a fluorometer with a minimum requirement of ≥20 ng/μL, and then the DNA samples were divided into three parts, which were used for absolute quantification PCR, amplicon sequencing, and metagenomics sequencing, respectively.

The absolute quantification PCR was carried out on a Yarui MA-6000 real-time PCR system (Suzhou Yarui Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China) with AceQ® qPCR SYBR® Green Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) by Shanghai Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) according to the methods described by [27]. The specific primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′)/806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) and ITS1F (5′-CTTGGTCATTTAGAGGAAGTAA-3′)/ITS2 (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′) were used to quantify the abundance of total bacteria and total fungi, respectively [28].

For amplicon sequencing, the above-mentioned primers 338F/806R and ITS1F/ITS2 were used to amplify the V3–V4 regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene and the ITS1 regions of the fungal rRNA gene, respectively. The amplicon sequencing of DNA libraries was executed on the Illumina NovaSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with paired-end 250 bp reads by Shanghai Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) [27].

For metagenomics sequencing, the shotgun sequencing of DNA libraries was executed on the Illumina NovaSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with a paired-end 150 bp strategy by Shanghai Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) [24].

2.5. Bioinformatics Analysis for High-Throughput Sequencing Data

For amplicon sequencing data, the bioinformatic analysis was performed using Easy Amplicon v1.20 (https://github.com/YongxinLiu/EasyAmplicon, accessed on 1 December 2025). Briefly, the primer removal, quality control and sequence deduplication were conducted via vsearch v2.22.1 software (https://github.com/torognes/vsearch, accessed on 1 December 2025), the amplicon sequence variant (ASV) denoise was performed using the unoise3 algorithm in usearch v10.0.240 software (https://www.drive5.com/usearch/, accessed on 1 December 2025), and then the taxonomy of each 16S rRNA and ITS rRNA (ASV) was performed by aligning each representative sequence against the RDP (rdp_16s_v18) and UNITE (utax_reference_dataset_all_25.07.2023), respectively. For metagenomics sequencing data, the quality control was conducted using fastp v0.23.4 (https://github.com/OpenGene/fastp, accessed on 1 December 2025), and the host removal (Glycine max and Triticum aestivum) was performed by kneaddata v0.12.0 (https://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/kneaddata, accessed on 1 December 2025) to obtain clean data. Finally, the read-based taxonomic classification was performed by Kaiju v1.10.1 (https://github.com/bioinformatics-centre/kaiju, accessed on 1 December 2025) in greedy mode with five allowed mismatches and E-value < 0.00001, and the assembly-based analysis was conducted using EasyMetagenome v1.21 (https://github.com/YongxinLiu/EasyMetagenome, accessed on 1 December 2025).

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Visualization

The multiple comparisons and histograms of physicochemical parameters were performed using Origin 2022 equipped with the paired comparison plot app (https://www.originlab.com/, accessed on 1 December 2025). The principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted in R 4.3.3 (https://www.r-project.org/, accessed on 1 December 2025) using packages vegan, ggplot2, and ggpubr. The stacking histograms and bubble matrix diagrams were drawn using R packages reshape2 and ggplot2. The combinations of graphs by ggplot2 were conducted using the R package patchwork. The metabolic networks were visualized using PathVisio v3.3.0 (https://pathvisio.org/, accessed on 1 December 2025), in which the heatmaps of metabolites were generated in R using packages vegan and pheatmap. The drawing of the schematic diagram and the beautification of graphs were conducted using Adobe Illustrator 2023 (https://www.adobe.com/, accessed on 1 December 2025).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Properties

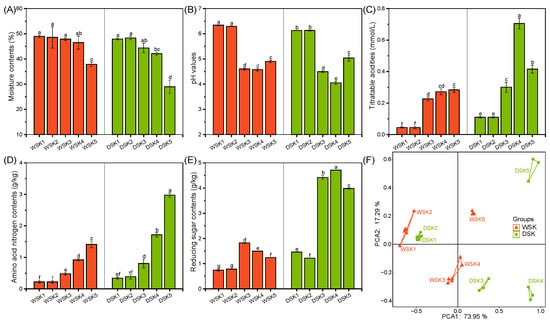

The temporal dynamics of physicochemical parameters during koji fermentation are demonstrated in Figure 1. As the fermentation progressed, the overall trends of the five parameters in the two groups of soy sauce koji samples were similar, consistent with previous reports [4]. However, compared with soy sauce koji made from whole soybeans (WSK), soy sauce koji made from defatted soybeans, wheat, and bran (DSK) exhibited lower MC (WSK5: 37.9%, DSK5: 29.0%) and higher TA (0.28 mmol/g, 0.42 mmol/g), AN (1.4 g/kg, 3.0 g/kg), and RS (1.2 g/kg, 4.0 g/kg). It is generally accepted that the initial increase in acidity is due to the accumulation of organic acids produced by microorganisms such as lactic acid bacteria, and then the subsequent reduction in acidity is attributed to the production of ammonia associated with protein degradation and the decomposition of organic acids [27,29]. The consistently higher acidity in the DSK (Figure 1C) indicated that it had higher metabolic activity of acid-producing bacteria as well as a higher utilization rate of raw materials. The AN is closely related to the nitrogen content of free amino acids and small peptides and is evaluated as the main indicator of the quality in mature koji [30]. The significantly higher level of AN in the DSK (Figure 1D) suggested that defatted soybeans are more suitable for making high-quality soy sauce koji. The RS in soy sauce koji is primarily produced through the hydrolysis of soybeans, wheat, and other substrates by A. oryzae, yielding monosaccharides such as glucose and galactose. These sugars contribute sweetness and serve as essential carbon sources for the formation of flavor- and aroma-active compounds [31,32]. Although previous studies have reported no significant differences in RS content between koji prepared from whole and defatted soybeans [4], the formulations used in the present study differ markedly. The DSK included crushed wheat and wheat bran, whereas the WSK contained only whole soybeans. The elevated starch content in wheat and bran is more easily hydrolyzed by A. oryzae, resulting in higher RS levels [33]. These differences in substrate composition and structure reasonably explain the higher sugar content observed in DSK (Figure 1E). Additionally, PCA showed that the physicochemical parameters in the WSK were consistently different from those in the DSK, except for the initial stage of fermentation (Figure 1F), which might be the direct result of substrate differences and the microbial community differences they induce.

Figure 1.

Variations in physicochemical parameters during koji preparation in two soy sauce groups. (A) Bar chart of the dynamic changes in moisture contents (MC), (B) pH values, (C) titratable acidities (TA), (D) amino acid nitrogen contents (AN), (E) reducing sugar contents (RS), (F) PCA score plot of all physicochemical parameters. Different letters represent significant differences at p < 0.05 (Tukey’s post hoc test, n = 3).

3.2. Volatile Compounds (VCs), Free Amino Acids (FAAs), and Organic Acids (OAs)

3.2.1. Temporal Dynamics of VCs During Koji Fermentation

A total of 61 VCs were identified by HS-SPME/GC-MS, including 19 alcohols, 5 acids, 5 esters, 12 aldehydes, 9 ketones, 6 phenols, and 5 others. PCA demonstrated that the composition of volatiles in the WSK during stages 3 to 5 was significantly different from that in the DSK (Figure 2A). At the beginning (stages 1 and 2), the total contents of VCs in both were low (i.e., WSK: 0.70 ± 0.31 μg/g, DSK: 0.69 ± 0.21 μg/g, mean ± SD, n = 6), mainly consisting of phenols, aldehydes, and alcohols, e.g., 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol, hexanal, 1-octen-3-ol, and 2-ethyl-1-hexanol (Figure 2B,C). In the middle and late stages of fermentation (stages 3 to 5), the types and contents of VCs increased significantly (Figure 2B,C). Specifically, during stages 3 and 4, the WSK was characterized by a dramatic increase in diverse alcohols, aldehydes, and ketones, e.g., 3-methyl-1-butanol, 1-octen-3-ol, ethanol, benzeneacetaldehyde, 3-methyl-1-butanal, and acetoin; meanwhile, the DSK was rich in phenols, alcohols, and aldehydes, e.g., 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol, 3-methyl-1-butanol, 1-octen-3-ol, ethanol, benzeneacetaldehyde, and 3-methyl-1-butanal (Figure 2B,C).

Figure 2.

Dynamic changes in volatile compositions (VCs) during koji preparation in two soy sauce groups. (A) PCA score plot, (B) stacking histograms of different classes of VCs, (C) bubble matrix diagrams of all VCs. * denotes unknown absolute configuration with known relative configuration.

Lipid and protein degradation were generally recognized as crucial processes for the formation of flavors in soy sauce koji [34]. For instance, auto-oxidation or enzyme-oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids facilitated the accumulation of aldehydes, ketones, and alcohols [27]; protein hydrolysis by proteases produced various amino acids and peptides, which served as flavor compounds and their precursors. 1-Octen-3-ol (mushroom aroma), a common unsaturated alcohol in fermented soybean products, was mainly generated by oxidation of linoleic acid and arachidonic acid [34], and the high content of lipids in whole soybeans was responsible for the higher content of 1-octen-3-ol in the WSK. Some higher alcohols and corresponding aldehydes were mainly generated through carbohydrate metabolism or amino acid decarboxylation, e.g., decarboxylation of leucine produced 3-methyl-1-butanol and 3-methyl-1-butanal, and decarboxylation of phenylalanine produced phenylethyl alcohol and benzeneacetaldehyde [35]. These abundant substances in the two groups might be the characteristic flavor compounds of soy sauce koji. In addition, the DSK had a significantly higher content of 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol (baking and nutty aroma), which should be related to the lignin content in the raw materials, as 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol was the decarboxylation product of lignin-derived ferulic acid [36]. Therefore, the higher levels of lignin in wheat and bran were responsible for the higher content of 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol in the DSK.

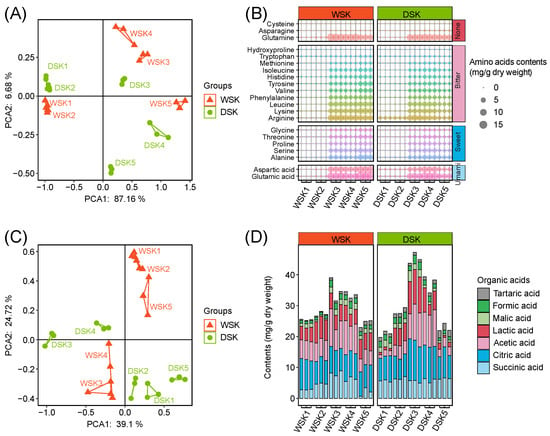

3.2.2. Temporal Dynamics of FAAs During Koji Fermentation

A total of 21 FAAs (i.e., 20 standard amino acids and hydroxyproline) were quantitatively detected by LC-MS. The total content of FAAs, as well as the content of most FAAs, gradually increased with the fermentation process, consistent with previous studies [30]. Glutamic acid, glutamine, arginine, and aspartic acid were the predominant FAAs during fermentation, with an average content of 7.0 ± 6.5 mg/g, 6.0 ± 5.1 mg/g, 4.3 ± 3.2 mg/g, and 4.2 ± 3.9 mg/g (mean ± SD, n = 30), respectively, which were responsible for 50.9 ± 12.4% of total FAAs (Figure 3A,B). Compared with the WSK, the higher level of total FAAs in the DSK was consistent with its higher content of AN, which should be related to its higher protein content [37].

Figure 3.

Dynamic changes in free amino acids (FAAs) and organic acids (OAs) during koji preparation in two soy sauce groups. (A) PCA score plot of FAAs, (B) bubble matrix diagrams of FAAs, (C) PCA score plot of OAs, (D) stacking histograms of OAs composition.

3.2.3. Temporal Dynamics of OAs During Koji Fermentation

The concentration changes in seven organic acids (OAs) were determined using HPLC (Figure 3D). PCA revealed persistent differences in OAs composition between the WSK and DSK throughout the fermentation process. In both, the total content of OAs and the individual OA concentrations exhibited an initial increase followed by a subsequent decrease. Notably, a significantly higher total content of OAs was observed in the DSK during fermentation stage 3 (WSK: 35.05 ± 3.75 mg/g; DSK: 45.33 ± 1.80 mg/g), and a more pronounced decline was observed in the later stages of fermentation.

Citric acid, acetic acid, succinic acid, and lactic acid were identified as the predominant OAs, with average concentrations of 8.92 ± 1.81 mg/g, 6.52 ± 3.36 mg/g, 5.36 ± 1.82 mg/g, and 5.13 ± 2.86 mg/g, respectively (mean ± SD, n = 30), accounting for 85.03 ± 0.23% of the total OAs. Compared to the WSK, the DSK exhibited a higher overall content of OAs, which was consistent with its higher acidity. The DSK, which was fermented using defatted soybean, wheat bran, and wheat, developed a porous structure that may have facilitated oxygen diffusion. This likely promoted glycolytic metabolism by acid-producing bacteria such as Weissella and Bacillus, thereby enhancing the production of lactic and acetic acids [36,38]. Carbohydrate metabolism is a significant source of non-volatile OAs. Among these, lactic acid is one of the predominant OAs during soy sauce fermentation. The unique acidity of lactic acid plays a crucial role in harmonizing and enhancing the overall flavor of soy sauce. In the later stages of fermentation, the concentrations of lactic acid and acetic acid are observed to decrease significantly. This decline is likely attributed to esterification reactions, resulting in the formation of ethyl lactate and ethyl acetate, which contribute to the characteristic ester-like flavors of soy sauce [31,39,40]. Succinic acid plays multiple roles during soy sauce fermentation, contributing to sour, salty, bitter, and umami tastes and serving as an important precursor for various flavor compounds [34]. At equivalent concentrations, citric acid has been reported to impart a stronger sour taste than succinic acid [6]. The concentrations of citric acid and succinic acid were observed to be significantly higher in DSK than in WSK, suggesting that the conditions in DSK may favor the accumulation of these two OAs.

3.3. Dynamics of Microbial Succession

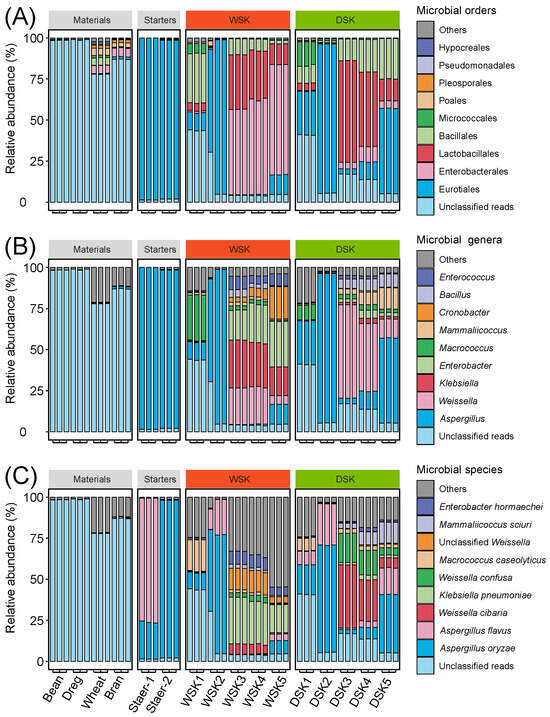

3.3.1. Amplicon Sequencing-Based Analysis of Bacterial Community Succession

Amplicon sequencing was utilized to investigate the compositional differences in bacterial and fungal communities between the two groups. After quality control, a total of 3,591,040 16S rRNA sequences and 6,529,500 ITS sequences were obtained from two groups of samples. Taxonomic annotation of microbial communities identified 64 bacterial orders and 51 fungal orders, along with 293 bacterial genera and 110 fungal genera. The relative abundances (RA) of the top 10 predominant orders and genera of bacteria and fungi were 99.88% and 99.83% (Figure 4A,B), and 75.42% and 98.25% (Figure S2A,B), respectively.

Figure 4.

Bacterial community structure and succession during koji preparation in two soy sauce groups based on 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. (A) Relative abundance of bacterial orders, (B) relative abundance of bacterial genera.

During the fermentation process of both, the bacterial community composition at the order level exhibited a similar trend. In the early stages of fermentation, Lactobacillales dominated the microbial community. Beginning at the first turning (Stage 3), Enterobacterales gradually replaced Lactobacillales as the dominant. However, moving to the genus level, notable differences in bacterial community composition were observed between the two groups. In the WSK, the dominant Lactobacillales genera during the initial fermentation stage were Leuconostoc and Carnobacterium, whereas Weissella and Leuconostoc predominated in the DSK. Following the first turning, genera such as Klebsiella and Enterobacter became dominant in the WSK. In contrast, these bacteria, along with Weissella, constituted the major bacterial taxa in the DSK. Additionally, at the end of fermentation (Stage 5), Staphylococcus and Bacillus were detected at relatively high abundances in the DSK. Among the fungal order and genus levels, Eurotiales and Aspergillus were overwhelmingly dominant in two groups (RA exceeding 99%) (Figure S2), consistent with fungal profiles reported in other studies on soy sauce fermentation koji [41]. Moreover, based on the bacterial community composition of the raw materials, it was found that the dominant bacterial taxa in soybeans were not prevalent during the fermentation process of the WSK starter. This suggests that the bacterial community in the WSK primarily originated from the starter culture and the brewing environment, rather than from the soybeans themselves. In the DSK, the initial bacterial community was likely derived mainly from soybean meal, starter culture, and the surrounding fermentation environment, while the contributions from wheat and wheat bran appeared to be relatively minor.

Aspergillus possesses a complex enzymatic system capable of efficiently degrading starch and protein substrates, providing essential nutrients and energy for the subsequent metabolic activities of other microorganisms [26,42]. Consistently, Aspergillus dominated both groups (RA > 99%), which is consistent with the intended outcomes of industrial koji-making processes [34]. Weissella, a common obligate LAB frequently detected in various fermented foods, contributes to the production of lactic acid, isoamyl acetate, and other metabolites, and functions as a functional LAB that promotes the formation of OAs, oligopeptides, and FAAs in fermented soybean products [36]. Enterobacter species are commonly observed in soybean-based koji and moromi and can contribute to the production of ester compounds via their enzymatic activities [36,43]. The accumulation of flavor- and aroma-active compounds is promoted by the predominance of Aspergillus, Weissella, and Enterobacter in DSK, consistent with industrial koji production goals.

3.3.2. Metagenomic Sequencing-Based Analysis of Microbial Community Succession

Metagenomic sequencing technology was employed to further quantify the differences in functional microbial communities. A total of 3,569,154,322 sequencing reads were generated, yielding 538.94 Gbp of raw data. Following stringent quality control procedures, 525.21 Gbp of the clean data from 98% reads were retained for the subsequent analysis. Taxonomic annotation of these sequences led to the identification of 141 orders, 652 genera, and 1919 species. The RA of the top 10 predominant order, genus, and species levels accounted for 99.26%, 93.22%, and 83.05%, respectively (Figure 5A–C).

Figure 5.

Microbial community structure and succession during koji preparation in two soy sauce groups based on metagenomic sequencing. (A) Relative abundance of community orders, (B) relative abundance of community genera, (C) relative abundance of community species.

At the order level (Figure 5A), Eurotiales, Bacillales, Enterobacterales, and Lactobacillales (RA > 7.7%) were dominant in both fermentation groups, aligning with amplicon data. Early fermentation was dominated by Eurotiales and Bacillales, while Enterobacterales and Lactobacillales increased markedly after the first turning, forming the core community in later stages. However, distinct differences were observed at the genus level (Figure 5B). Overall, Aspergillus dominated during the koji mixing stage (Stage 2) in both, while bacterial communities became more dominant as fermentation progressed. Specifically, during the post-steaming cooling stage (Stage 1), Macrococcus (RA: 1.9%, mainly Macrococcus caseolyticus) was the predominant microorganism in both. Once koji mixing began, Aspergillus (RA: 30.53%, primarily Aspergillus oryzae and Aspergillus flavus) occupied the ecological niche. In the middle and late stages of fermentation, Weissella (RA: 10.08%, mainly Weissella cibaria and Weissella confusa), Klebsiella (RA: 5.03%, mainly Klebsiella pneumoniae), and Enterobacter (RA: 4.98%, mainly Enterobacter hormaechei) emerged as dominant genera in the WSK. In contrast, the DSK was characterized by the dominance of Aspergillus, Weissella, Cronobacter, and Bacillus (each with RA > 1.80%).

Additionally, analysis of the raw material microbiota indicated that microorganisms inherent to soybeans and defatted soybeans had minimal impact on the initial community structure. Thus, the genus-level differences between WSK and DSK were unlikely to be driven by substrate-borne microbes but rather by the distinct nutritional and physicochemical properties of the two substrates. These properties imposed differential selective pressures on starter- and environment-derived microorganisms, leading to divergent enrichment patterns and microbial succession.

Bacillus is a dominant bacterial genus in many fermented soybean products and is capable of degrading starch, proteins, and lipids through the secretion of specific enzymes. Accordingly, it is regarded as a key microbial group in various fermentation processes and has been selected for the development of specialized fermentation starter cultures [22,36]. In the later stages of fermentation, the abundance of Bacillus was higher in DSK, which may be attributed to the porous structure formed by the DSK substrates. This structure likely facilitates the establishment of microaerobic conditions, thereby promoting the enrichment of Bacillus [36]. Metagenomic sequencing further confirmed that the predominance of microorganisms such as Aspergillus, Weissella, and Bacillus in DSK is conducive to industrial soy sauce koji production.

3.4. Flavor Compounds Metabolic Pathways

Soybeans and defatted soybeans are rich in starch, lipids, and proteins, which serve as major substrates for the formation of various flavor compounds during soy sauce fermentation [4]. In the present study, metabolic networks associated with the production of 48 flavor-related metabolites were reconstructed for both substrates using the KEGG and MetaCyc databases. These reconstructed pathways include the formation of aldehydes and acids as precursors of esters, as well as carbohydrate metabolism, amino acid metabolism, and related biosynthetic processes (Figure 6) [43,44,45]. Among these pathways, carbohydrate metabolism provides the fundamental basis for microbial growth and the subsequent generation of flavor compounds [30]. Several key enzymes involved in the conversion of starch and sucrose to glucose were found to be highly active, including sucrose phosphorylase (EC:2.4.1.7), glycogen phosphorylase (EC:2.4.1.1), and glucoamylase (EC:3.2.1.3). These enzymes were primarily produced by Aspergillus and Weissella (Figure S3). Previous studies [44] have also confirmed the essential roles of these microorganisms in starch degradation.

Figure 6.

Metabolic networks of carbohydrate, protein and fatty acid metabolic networks during koji preparation in two soy sauce groups based on KEGG (EC: black) and MetaCyc (EC: red) databases. Heatmaps show the dynamics of Z-score normalized levels of AAs (blue to red), OAs (purple to red), and selected VCs (green to red).

FAAs are important indicators of soy sauce quality, and their accumulation is primarily derived from the hydrolysis of protein in the raw materials, as well as from amino acid biosynthesis [30]. As shown in Figure 6, pyruvate is converted into acetyl-CoA and enters the TCA cycle, in which 2-oxoglutarate and oxaloacetate act as key intermediates involved in the synthesis and metabolism of various amino acids. For example, 2-oxoglutarate is converted to glutamate via EC:1.4.1.13 and EC:1.4.1.14, providing precursors for the metabolism of arginine and proline as well as for Arg biosynthesis. Similarly, oxaloacetate is converted to aspartate through the action of EC:2.6.1.1, which participates in lysine biosynthesis and the metabolism of alanine, serine, threonine, cysteine, and methionine. During fermentation, the concentrations of most FAAs gradually increased in both substrates, consistent with the objective of enhancing protein degradation during koji preparation. Notably, amino acid degradation constitutes a critical pathway for the formation of characteristic volatile compounds [11]. In DSK, leucine, tyrosine, and phenylalanine were significantly depleted from fermentation stages 4 to 5, likely due to their conversion into multiple flavor precursors. For instance, leucine degradation can produce 3-methylbutanal and 3-methylbutanol, while tyrosine and phenylalanine are enzymatically converted into phenol, phenylethylalcohol, and phenylacetaldehyde. Among these, phenylacetaldehyde and phenylethylalcohol are primarily produced via the actions of EC:1.4.3.4 and EC:1.1.1.90, both of which contribute to the characteristic aromatic profile of soy sauce [30]. It is noteworthy that ferulic acid is an important phenolic acid compound, with wheat and bran being its primary natural sources [13]. In addition, ferulic acid can also be enzymatically synthesized from phenylalanine and further converted into 4-vinylguaiacol (4-VG) and 4-ethylguaiacol (4-EG) through the action of phenacrylate decarboxylase (EC:4.1.1.102). The substantial accumulation of 4-VG observed in DSK was primarily attributed to the high levels of ferulic acid present in the raw materials.

In terms of fatty acid metabolism, unsaturated fatty acids are generally oxidized to form hydroperoxides, which are further cleaved to generate various flavor compounds [34]. For instance, palmitic acid, oleic acid, and linoleic acid can undergo autoxidation to produce key volatile compounds such as decanal, hexanal, and 1-octen-3-ol. Among these, 1-octen-3-ol exhibits a characteristic mushroom-like aroma and can be enzymatically produced from lecithin [44]. The key enzymes involved in its synthesis include phospholipase A1/A2 (EC:3.1.1.4), linoleate 10R-lipoxygenase (EC:1.13.11.62), and aldehyde-lyases (EC:4.1.2.-). These enzymes were maintained at relatively high abundances during the late stages of fermentation and were predominantly produced by Aspergillus, consistent with previous studies [46]. Notably, the abundances of these key enzymes were significantly higher in WSK than in DSK, which corresponds to the higher levels of 1-octen-3-ol detected in WSK (0.70 ± 0.81 μg/g) compared to DSK (0.45 ± 0.71 μg/g). This observation further indicates that the contribution of fatty acid oxidation to flavor formation varies between different substrates.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study systematically elucidated the role and underlying mechanisms of defatted soybean-based koji in enhancing the quality of DB soy sauce by integrating multi-omics analyses, AQ-PCR, and key physicochemical parameters. The results demonstrated that the substrate composition (whole soybean koji, WSK; defatted soybean–wheat bran koji, DSK) significantly influenced the structure and metabolic activity of microbial communities during the koji fermentation process, which in turn modulated physicochemical properties and flavor profiles. The DSK, owing to its higher protein content, porous structure, and the synergistic effect of wheat and bran components, favored the dominance of microbial populations with enhanced proteolytic and acid-producing capacities, such as Weissella and Bacillus species. This dominance resulted in increased amino acid nitrogen production, enriched organic acid accumulation, and elevated levels of characteristic phenolic compounds, including 2-methoxy-4-vinylphenol. Analyses of 16S rRNA and ITS revealed that Aspergillus, Weissella, and Enterobacter were predominant in DSK, creating conditions conducive to the accumulation of flavor and aroma compounds, in alignment with industrial objectives for soy sauce fermentation. Metagenomic sequencing further confirmed the dominance of Aspergillus, Weissella, and Bacillus in DSK, providing microbial evidence supporting industrial koji production. Flavor-related metabolic pathways encompassed the generation of aldehyde and acid precursors for esters, as well as carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism and biosynthesis. Specifically, in WSK, Aspergillus promoted the accumulation of 1-octen-3-ol, whereas in DSK, abundant Weissella and substrate-derived ferulic acid facilitated the production of lactate and the key smoked flavor compound 4-vinylguaiacol. Collectively, these findings link substrate characteristics, microbial ecology, and koji quality, providing a theoretical basis for optimizing soy sauce flavor through the use of defatted soybeans. Future research should focus on functional validation of key enzymatic pathways (e.g., via metatranscriptomics), optimization of fermentation parameters to regulate substrate-specific microbial communities, and integration with systematic sensory analyses to directly correlate microbial metabolites with final soy sauce quality, enabling precise control of fermentation and flavor enhancement.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fermentation11120685/s1, Figure S1: AQ-PCR of bacteria (A) and fungi (B) during koji preparation in two soy sauce groups; Figure S2: Fungi community structure and succession during koji preparation in two soy sauce groups based on ITS amplicon sequencing. (A) Relative abundance of fungal orders. (B) Relative abundance of fungal genera; Figure S3: Genus-level microbial sources of key enzymes in carbohydrate, protein and fatty acid metabolic networks; Table S1: Linear ranges and limits of detection (LOD) of 21 FAAs; Table S2: Analysis of volatile compounds during koji preparation in two soy sauce groups.

Author Contributions

K.-Y.C.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—original draft. N.Z.: Visualization, Writing—review and editing. W.-H.L.: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing—review and editing. C.W.: Data curation, Writing—review and editing. Y.-Q.H.: Funding acquisition. C.-H.S.: Funding acquisition, Writing—review and editing. L.Z.: Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. X.R.: Project administration, Supervision, Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that this study received funding from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2022YFD2101205), Deyang Seasoning Food Co., Ltd. and Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. (National Engineering Research Center of Solid-State Brewing).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequence data reported in this study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in the National Genomics Data Center, China National Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and can be accessed using the following accession numbers: CRA028105, CRA028106, and CRA028118. The data are publicly available at https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Wen-Hu Liu, Yong-Qi Hu, and Cai-Hong Shen were employed by the companies Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. and Luzhou Pinchuang Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from Deyang Seasoning Food Co., Ltd. and Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DB | Deyang Baiwo |

| WSK | Whole Soybeans Koji |

| DSK | Defatted Soybeans combined with Wheat Bran Koji |

| AQ-PCR | Absolute Quantification Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| pH | potential of Hydrogen |

| TA | Titratable Acidity |

| AN | Amino acid Nitrogen |

| RS | Reducing Sugar |

| VCs | Volatile Compounds |

| FAAs | Free Amino Acids |

| OAs | Organic Acids |

| 16S rRNA | 16S ribosomal RNA |

| ITS rRNA | Internal Transcribed Spacer ribosomal RNA |

| RA | Relative Abundances |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| MetaCyc | MetaCyc Metabolic Pathway Database |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle |

References

- Wang, J.; Xie, Z.; Feng, Y.; Huang, M.; Zhao, M. Co-Culture of Zygosaccharomyces Rouxii and Wickerhamiella Versatilis to Improve Soy Sauce Flavor and Quality. Food Control 2024, 155, 110044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwood, J.G.; Wakeling, L.T.; Bean, D.C. Fermentation and the Microbial Community of Japanese Koji and Miso: A Review. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 2194–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Tramper, J. Koji—Where East Meets West in Fermentation. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tong, X.; Hou, S.; Zhao, M.; Feng, Y. Flavor Differences of Soybean and Defatted Soybean Fermented Soy Sauce and Its Correlation with the Enzyme Profiles of the Kojis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Peng, J.; He, Y. A Systematic Comparative Study on the Physicochemical Properties, Volatile Compounds, and Biological Activity of Typical Fermented Soy Foods. Foods 2024, 13, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Tian, Y.; Su, G.; Zhao, M.; Feng, J.; Feng, Y. Differences in Taste and Material Basis of Soybean and Defatted Soybean Fermented Soy Sauces and Influence Factors. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 136, 106768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskildsen, M.; Pape Andersen, M.; Christoffer Johannsen, J.; Kappel Theil, P. P32. Daily Gain and Feed Intake of Organic Piglets Fed Either Biorefined Grass Protein or Soy-Bean-Meal Five Weeks Prior to Weaning. Anim.—Sci. Proc. 2022, 13, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Peng, P.; Yu, L.; Wan, B.; Liang, X.; Liu, P.; Liao, W.; Miao, L. Metagenomic Analysis Reveals the Correlations between Microbial Communities and Flavor Compounds during the Brewing of Traditional Fangxian Huangjiu. Food Biosci. 2024, 58, 103816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.J.; Schieber, A.; Gänzle, M.G. Formation of Taste-Active Amino Acids, Amino Acid Derivatives and Peptides in Food Fermentations—A Review. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zhang, L.-L.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Sun, B.-G.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, H.-T. Evaluation of Non-Volatile Taste Components in Commercial Soy Sauces. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21, 1854–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, D.; Shi, Y.; Meng, R.; Yong, Q.; Shi, Z.; Shao, D.; Sun, B.; Zhang, Y. Decoding the Different Aroma-Active Compounds in Soy Sauce for Cold Dishes via a Multiple Sensory Evaluation and Instrumental Analysis. Foods 2023, 12, 3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.-H.; Mu, D.-D.; Guo, L.; Wu, X.-F.; Chen, X.-S.; Li, X.-J. From Flavor to Function: A Review of Fermented Fruit Drinks, Their Microbial Profiles and Health Benefits. Food Res. Int. 2024, 196, 115095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devanthi, P.V.P.; Gkatzionis, K. Soy Sauce Fermentation: Microorganisms, Aroma Formation, and Process Modification. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, S.; Wan-Mohtar, W.A.A.Q.I.; Jamaludin, N.S.; Ilham, Z. Recent Progress and Advances in Soy Sauce Production Technologies: A Review. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e15799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, M.; Xie, N.; Huang, M.; Feng, Y. Community Structure of Yeast in Fermented Soy Sauce and Screening of Functional Yeast with Potential to Enhance the Soy Sauce Flavor. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 370, 109652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xiong, S.; Du, T.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Huang, G.; Guan, Q.; Xiong, T. Unraveling the Core Functional Microbiota Involved in Metabolic Network of Characteristic Flavor Development during Soy Sauce Fermentation. Food Biosci. 2024, 58, 103697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.Y.; Ilham, Z.; Samsudin, N.I.P.; Soumaya, S.; Wan-Mohtar, W.A.A.Q.I. Microbial Consortia and Up-to-Date Technologies in Global Soy Sauce Production: A Review. Int. Food Res. J. 2023, 30, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Peng, D.; Zhang, W.; Duan, M.; Ruan, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhou, S.; Fang, Q. Effect of Aroma-Producing Yeasts in High-Salt Liquid-State Fermentation Soy Sauce and the Biosynthesis Pathways of the Dominant Esters. Food Chem. 2021, 344, 128681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huang, L.; Zhou, S.; Awad, S.; Ibrahim, A.; Chen, J.; Du, M. Metagenomics and Metabolomics-Based Approaches to Reveal the Formation of Flavor Metabolites during Post-Fermentation of Multi-Strain Complex Fermented Douchi. Food Biosci. 2025, 73, 107629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Song, X.; Mu, Y.; Sun, W.; Su, G. Co-Culturing Limosilactobacillus Fermentum and Pichia Fermentans to Ferment Soybean Protein Hydrolysates: An Effective Flavor Enhancement Strategy. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 100, 103920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, T.; Zhao, M.; Feng, Y. Effect of Co-Inoculation of Different Halophilic Bacteria and Yeast on the Flavor of Fermented Soy Sauce. Food Biosci. 2023, 51, 102292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Jin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xia, B.; Sun, Q. Dynamics of Microbial Community during the Extremely Long-term Fermentation Process of a Traditional Soy Sauce. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 3220–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Zhou, R.; Qi, Q.; Yang, M.; Peng, C.; Wu, C.; Jin, Y. The Effects of Different Coculture Patterns with Salt-Tolerant Yeast Strains on the Microbial Community and Metabolites of Soy Sauce Moromi. Food Res. Int. 2021, 150, 110747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.-H.; Chai, L.-J.; Wang, H.-M.; Lu, Z.-M.; Zhang, X.-J.; Xiao, C.; Wang, S.-T.; Shen, C.-H.; Shi, J.-S.; Xu, Z.-H. Community-Level Bioaugmentation Results in Enzymatic Activity- and Aroma-Enhanced Daqu through Altering Microbial Community Structure and Metabolic Function. Food Biosci. 2024, 57, 103630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Lyu, W.; Dinssa, F.F.; Simon, J.E.; Wu, Q. Free Amino Acids in African Indigenous Vegetables: Analysis with Improved Hydrophilic Interaction Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry and Interactive Machine Learning. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1637, 461733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiong, S.; Du, T.; Xiao, M.; Peng, Z.; Xie, M.; Guan, Q.; Xiong, T. Effects of Microbial Succession on the Dynamics of Flavor Metabolites and Physicochemical Properties during Soy Sauce Koji Making. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-H.; Chai, L.-J.; Wang, H.-M.; Lu, Z.-M.; Zhang, X.-J.; Xiao, C.; Wang, S.-T.; Shen, C.-H.; Shi, J.-S.; Xu, Z.-H. Bacteria and Filamentous Fungi Running a Relay Race in Daqu Fermentation Enable Macromolecular Degradation and Flavor Substance Formation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 390, 110118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Chai, L.-J.; Zhao, H.; Song, Y.-N.; Mei, J.-L.; He, Y.-X.; Lu, Z.-M.; Zhang, X.-J.; Yang, B.; Wang, S.-T.; et al. Deciphering the Effects of Different Types of High-Temperature Daqu on the Fermentation Process and Flavor Profiles of Sauce-Flavor Baijiu. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Du, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, B.; Hardie, W.J.; Tang, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Xiao, M.; Xiong, T.; et al. Co-Fermentation of Peanut Milk by Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria on Its Protein Structure, Ara h 1’s Immunoreactivity, Physical-Chemical Properties and Sensory Attributes. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Lin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Li, W.; Lin, W.; Luo, L. Comprehensive Analysis of Flavor Formation Mechanisms in the Mechanized Preparation Cantonese Soy Sauce Koji Using Absolute Quantitative Metabolomics and Microbiomics Approaches. Food Res. Int. 2024, 180, 114079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xiao, Z.; Gu, Z.; Deng, X.; Liu, J.; Luo, X.; Song, C.; Jiang, X. Fermentation-Promoting Effect of Three Salt-Tolerant Staphylococcus and Their Co-Fermentation Flavor Characteristics with Zygosaccharomyces Rouxii in Soy Sauce Brewing. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murai, T.; Annor, G.A. Improving the Nutritional Profile of Intermediate Wheatgrass by Solid-State Fermentation with Aspergillus Oryzae Strains. Foods 2025, 14, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, K.; Zhao, G.; Duan, X.; Hadiatullah, H. Effect of Wheat Germination on Nutritional Properties and the Flavor of Soy Sauce. Food Biosci. 2022, 48, 101738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Lin, J.; Lin, W.; Li, W.; Luo, L. Impacts of Aspergillus Oryzae 3.042 on the Flavor Formation Pathway in Cantonese Soy Sauce Koji. Food Chem. 2024, 441, 138396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Feng, Y.; Cui, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, M. Effects of Koji-making with Mixed Strains on Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Chinese-type Soy Sauce. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Pan, Z.; Li, M.; Li, L.; Zheng, Z. Comparative Evaluation of the Microbial Diversity and Metabolite Profiles of Japanese-Style and Cantonese-Style Soy Sauce Fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 976206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Kang, L.; Xu, Y. Phenotypic, Genomic, and Transcriptomic Comparison of Industrial Aspergillus Oryzae Used in Chinese and Japanese Soy Sauce: Analysis of Key Proteolytic Enzymes Produced by Koji Molds. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e00836-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.T.H.; Huang, M.B.; Liu, F.Y.; Huang, W.-L.; Tran, H.-T.; Hsu, T.-W.; Huang, C.-L.; Chiang, T.-Y. Deciphering Microbial Community Dynamics along the Fermentation Course of Soy Sauce under Different Temperatures Using Metagenomic Analysis. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2023, 42, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, F.; Wu, J.; Feng, Y.; Pan, G.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, J.; Yang, X.; Xue, R.; Wu, R.; Zhao, M. A Systematic Review on the Flavor of Soy-based Fermented Foods: Core Fermentation Microbiome, Multisensory Flavor Substances, Key Enzymes, and Metabolic Pathways. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2023, 22, 2773–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, T.; Huang, M.; Zhao, M. Exploring the Core Functional Microbiota Related with Flavor Compounds in Fermented Soy Sauce from Different Sources. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Huang, J.; Zhou, R.; Yang, M.; Zhang, L.; Peng, C.; Jin, Y.; Wu, C. Characterizing Microbial Community and Metabolites of Cantonese Soy Sauce. Food Biosci. 2021, 40, 100872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Hou, S.; Zeng, L.; Tang, H.; Tong, X.; Wu, C.; Liu, X.; Tan, G.; Guo, L.; Lin, J. Proteomics Analysis of Enzyme Systems and Pathway Changes during the Moromi Fermentation of Soy Sauce Mash. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 5735–5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Lei, J.; Yang, L.; Kan, Q.; Wang, P.; Li, J.; Chen, C.; He, L.; Fu, J.; Ho, C.-T.; et al. Metagenomics and Untargeted Metabolomics Analyses to Unravel the Formation Mechanism of Characteristic Metabolites in Cantonese Soy Sauce during Different Fermentation Stages. Food Res. Int. 2024, 181, 114116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Z.; Ma, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Lu, J.; Chen, X. Metagenomic Analysis of the Relationship between Microorganisms and Flavor Development during Soy Sauce Fermentation. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, C.; Chen, T.; Liu, F.; Luo, S.; Ye, J. Microorganisms and Characteristic Volatile Flavor Compounds in Luocheng Fermented Rice Noodles. Food Chem. 2025, 490, 145133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Kan, Q.; Yang, L.; Huang, W.; Wen, L.; Fu, J.; Liu, Z.; Lan, Y.; Huang, Q.; Ho, C.-T.; et al. Characterization of the Key Aroma Compounds in Soy Sauce by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry-Olfactometry, Headspace-Gas Chromatography-Ion Mobility Spectrometry, Odor Activity Value, and Aroma Recombination and Omission Analysis. Food Chem. 2023, 419, 135995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).