Abstract

This study utilized the high salt concentrations of liquid albumen (LA), a by-product of salted duck eggs, to enhance the traditional pickling process for hog casings (HCs) and investigated the feasibility of replacing salt brine with LA at varying concentrations and pickling periods. In addition, physicochemical properties, textural profile analysis (TPA), aroma analysis, and sensory evaluation were performed on sausages post-production to assess the recycling value of LA. This study revealed no significant differences among the groups compared to the control for proximate composition, apparent color, and aroma component profiles of the sausages. However, HC pickled in 50% LA for 7 days exhibited excellent sausage hardness, cohesiveness, and elasticity performance. It also achieved the highest scores for mouthfeel, aroma, and overall preference, indicating that this is a suitable concentration for brine substitution. According to the findings of this study, the application of LA as a substitute for traditional brine in pickling HCs has potential for improving the texture and sensory properties of sausage products. This can contribute to the accomplishment of a circular bioeconomy. One limitation of this study was that the HC pickling conditions (concentration and duration) required deeper optimization to facilitate subsequent large-scale production and application.

1. Introduction

Salted duck eggs are a classic pickled egg product popular in Asia, which can be steamed or boiled before being peeled and eaten [1]. The preserved yolks can fill other foods (such as mooncakes, buns, or zongzi) [2]. The global salted duck egg market was estimated at approximately USD 395 million in 2024, with a projected market value of around USD 500 million in 2025 [3]. However, the volatility of raw material prices [such as duck eggs and feed (corn and soybeans)], transportation, energy costs, and potential health issues associated with high sodium content may act as restraints [1,4]. Moreover, climate change, frequent avian influenza outbreaks, duck manure wastewater treatment, and the disposal of redundant salted duck egg LA were not yet sufficiently addressed [3,4,5,6].

HCs include natural products, plastics, collagen, and cellulose [7,8], where the global market size of natural HCs is reached USD 2.1 billion in 2024, and the market is expected to grow at a CAGR of 3.8% to reach approximately USD 2.97 billion by 2033 [9]. Moreover, the production of sausages is expected to drive further demand for HCs due to changing consumer preferences, a sustained growth in consumption, and a growing inclination towards convenience foods and ready-to-eat products [8]. Thus, natural HCs without synthetic food additives need to align with this trend. Their premium profile makes them a popular production choice by producers of gastronomy and meats [7,8]. Typically, all HCs from animal sources are cleaned and preserved in a 15–20 °C brine solution and are never stored for more than two days without refrigeration to avoid weakening the casings and losing elasticity and hardness [7]. However, the demand for kosher and halal food puts pressure on companies to provide HCs from non-pork sources. This is despite the utilization of HCs as an important by-product included in the assessment of sustainable animal production [7].

The food industry is exploring ecologically conscious value-added systems that operate under the circular bioeconomy concept to achieve low waste generation [5,10,11]. These systems enhance economic performance and promote sustainable development by transforming residual resources—such as waste or discarded materials—into value-added products based on their integration with existing technologies [5,10,11,12]. Therefore, this study employed LA rich in protein and high salt concentrations to replace the traditional high-salt solution used to pickle HCs before sausage manufacturing. We verified the effects of the alternative pickling solution on HCs through physicochemical tests, TPA, and the aroma of the sausages, followed by sensory evaluation. These synergistic processes were expected to enhance the recycling capability of LA while minimizing the high-salinity wastewater generated from the process of pickling HCs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Commercially available salted HCs (small and large intestines; initial salt concentration of 50% and thickness of 0.03 mm) were purchased from Yun Jian Industrial Co., Ltd. (Chiayi, Taiwan). Salted duck egg by-products (LA, salt concentration about 25%) were purchased from Yong Hao egg merchants (Tainan, Taiwan). All the essential chemicals employed in this research were procured from Sigma-Aldrich® (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), and they were used directly without any pre-treatment, unless specifically stated otherwise.

2.2. Processing of Samples and Pickling Solutions

2.2.1. Desalting of Commercially Available Salted HC

All commercially available salted HCs were cut into 10 cm lengths and cleaned with deionized water (DW) to remove the surface salt [13]. Afterwards, they were immersed in hypochlorite water, which was produced by electrolyzing the salted water for 2 min.

2.2.2. Processing of Pickling Solution

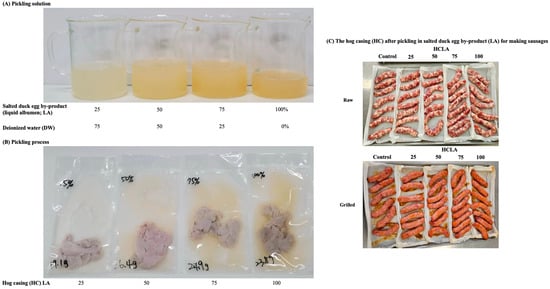

The LA was sieved through a 40 mesh and then prepared at different ratios to formulate the pickling solution (including: pH 6.8, protein 9.6%, lipid 0.05%, and ash 4.01%) for the HCs. Specifically, 25, 50, 75, and 100% of the LA were diluted with 0, 75, 50, and 25% of the DW, respectively, namely HCLA 25, 50, 75, and 100 (Figure 1A). In addition, the control group included untreated commercially available HCs.

Figure 1.

The hog casings (HCs) were pickled in salted duck egg by-product (liquid albumen; LB) for different durations and then used to manufacture the sausages: (A) pickling solution, (B) pickling process; and (C) HCLB sausages.

2.2.3. Pickling Process

Based on the weight of the HC, 2-fold weight of the above-mentioned pickling solution (w/w) was added and vacuum-packed, followed by refrigerated salting at 4 °C for 1, 7, 14, and 21 days before Chinese sausage production (Figure 1B).

2.2.4. Preparation of Chinese Sausages

The formulation of the Chinese sausage is based on the approach described by Huang et al. [14] with minor modifications. The recipe for Chinese sausages is listed in Table A1. The primary process involved twisting the lean pork (10,000 g each) into 1.27 and 2.54 cm3, adding all the seasonings, sodium nitrite, and polyphosphate, and mixing for 3 min. Afterwards, the cooking rice wine was added and mixed for 2 min, before adding the ground back fat (0.95 cm3) for 3 min. Eventually, Chinese sausages were obtained (Figure 1C) by filling the meat mixtures into the HCs (Section 2.2.3); randomly selected samples were then analyzed for the following physicochemical characterization.

2.3. Proximate Analysis

Proximate analyses were carried out in accordance with the standard method performance requirements (SMPRs®), and as described by AOAC [15]. The components of the samples were examined by measuring the water activity (AW; 978.18), moisture content (934.01), crude protein (984.13), crude fat (954.01), saturated and trans fats (996.06), sugars (982.14), ash (942.05), and sodium content (976.25).

2.4. Determining the Color of HCs

Color analysis was carried out for HCs according to the method described by Lin et al. [16]. The L* (brightness, with 100 being the brightest and 0 the darkest), a* (reddish-greenish color, positive for reddish, negative for greenish), and b* (yellowish-blueish color, positive for yellowish, negative for blueish) values of the samples (cooked) were measured using a hand-held imaging spectrocolorimeter (Lovibond® LC 100, Tintometer GmbH, Dortmund, Germany). Specifically, each sausage was measured at three points in the front, center, and end of the sausage.

2.5. TPA

The TPA of Chinese sausages (un-diced) was determined following the method described by Huang et al. [17], with minor modifications. TPA was performed using a texture analyzer (TA-XT2, Stable Micro Systems Ltd., Godalming, UK) with an HDP/VB probe. The specific parameters were as follows: initial, test, and post-test probe movement speed of 2 mm/s; compression ratio of 50%; recoverable time of 5 s; and trigger point load of 5 g. Then, the values of hardness (Newton; N), springiness, cohesiveness, and chewiness (N) were obtained.

2.6. Aroma Analysis

This study followed the method described by Wang et al. [18] with some modifications for analyzing volatile compounds in Chinese sausages. The samples were extracted using the solid-phase microextraction (SPME)-arrow tool (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Specifically, 3 g of sausage was placed into a 20 mL precision thread headspace-vial (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), and 10 μL of ethyl decanoate (50 μg/mL as internal standard) was added. The magnetic screw cap was immediately locked, and the volatile compounds were extracted using a multifunctional autosampler system AOC-6000 (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan). Briefly, the samples were shaken at 60 °C for 7.5 min and then adsorbed with 120 μm/20 mm divinylbenzene/polydimethylsiloxane (DVB/PDMS) fiber for 10 min. After extraction, the SPME-arrow tool was removed from the injection port at 250 °C for 3 min, and the volatile compounds were separated and identified using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis (GC-MS; GC-2010 Plus-TQ™8040, Shimadzu Co.). Specifically, the GC was equipped with a fused silica capillary column SH-Rxi-5Sil-MS (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. × 0.25 μm, (Shimadzu, Co., Ltd.); the oven was maintained at an initial temperature of 40 °C for 1 min, then increased at a rate of 2 °C/min to 128 °C, and then followed by an increase at a rate of 80 °C/min to 240 °C for 3 min. The flow rate was 1 mL/min, and helium (99.9995%) was used as the mobile phase. The MS parameters were in electron ionization mode (positive ions, 70 eV), with the ion source temperature set to 250 °C and a scanning range of 40–400 m/z. The retention index (RI) values were established using an Alkane standard mixture (Restek Co., Bellefonte, PA, USA), and the MS similarity of volatile compounds was compared with the software National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST; Gaithersburg, MD, USA) 17-1 and flavors/fragrances (FFNSC) 3rd Edition Wiley Library (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, USA) databases. In addition, the concentration of volatile compounds was calculated as shown in the following equation:

where

C represents the volatile compound peak area; I represents the internal standard peak area; 50 represents the weight (μg/mL) of the internal standard; and Ws represents the weight (g) of the Chinese sausage sample.

2.7. Sensory Evaluation

This study used different ratios of LA-pickled HCs to manufacture Chinese sausages, and invited volunteers aged 18 to 40 years (30 members of the consumer-type evaluation panel) to perform a hobby sensory evaluation according to the methodology described by Huang et al. [19], with slight modifications. All members were informed of the agreement, experiment settings, and could withdraw at any time, which was agreed to by written consent prior to the test. Briefly, participants were notified that their answers (were statistically analyzed with no personal privacy or information involved) would be published anonymously in a scientific journal with no financial or other compensation for their participation. While the evaluation was in progress, the room temperature was maintained at 25 ± 1 °C, and the room was kept noiseless. Each panelist was seated on a partitioned seat and could not talk or confer with the other. After sampling, panelists rinsed their mouths twice with drinking water until the taste was removed before the following sample was tasted. The evaluation scale was based on a 9-point scale, with 1—extremely disliked; 2—very disliked; 3—disliked; 4—somewhat disliked; 5—neither disliked nor liked; 6—slightly liked; 7—liked; 8—liked very much; and 9—liked immensely. The panelists rated the HCs’ appearance, aroma, mouthfeel, elasticity, crispness, integration of HC and filling, saltiness, and overall preference. Higher sensory scores indicated higher consumer preference for an HC.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

This study was repeated three times for each test (n = 3), except for proximate analyses, as shown in Table A2, which were only conducted once (n = 1). The data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted with XLSTAT statistical software (version 2019, Lumivero, Denver, CO, USA), and Duncan’s multiple range test was used to compare the variability among groups; p < 0.05 indicates a significant difference.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Properties of the Sausage

3.1.1. Moisture Content

This study utilized HCs pickled in LA (over 0–21 days and at different concentrations), followed by sausage manufacturing. The moisture content exhibited an increasing followed by a decreasing trend with increased HC pickling time and LA concentrations across all sausage groups (Table 1), which were significantly different from each other (p < 0.05); however, HCs pickled with LA for 14 days showed the highest moisture content in all groups. In particular, the HCLA 50 group exhibited the highest moisture content (44.34 ± 2.25%), with a significant difference compared to the HCLA 75 and 100 groups, whereas there was no significant difference compared to the HCLA 25 and control groups. Notably, the lowest moisture content (22.57 ± 5.78%) was detected in the HCLA50 group of sausages, which were pickled in LA for 21 days. Despite the HCs being pickled in LA for 21 days, no significant differences were reported between the groups.

Table 1.

Effects of hog casings (HCs) pickled in salted duck egg by-product (liquid albumen; LA) for different durations before use in sausage production on the moisture, water activity (AW), and color (L*, a*, and b* values) of the sausages.

These variations were attributed to accumulation of organic acid, which resulted in the denaturation of muscle proteins and contraction of muscle bundles, resulting in a loss of water between the networks of muscle fibers [20]. It has been reported that proper water vapor permeability (WVP) facilitates the efficient release of water from the sausage during this process, thus regulating and preventing the fermented sausage from drying out or undergoing excessive humidification [21]. Notably, Guan et al. [21] reported that when producing HCs with materials sensitive to moisture, these materials absorb water from the environment and meat fillings. They then form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, which ultimately impacts the tensile strength of the HC. The same authors also demonstrated that insufficient water absorption by the sausage casings affects their elongation. Therefore, the outer casing’s surface of HCLA sausages remained intact, and no cracks were observed during the production of the sausages until they were cooked. This also explains how the HC pickled in LA retained structural integrity even when in contact with the meat filling; it was unaffected by the filling and ambient environment.

3.1.2. AW

In this study, the AW of all groups ranged from 0.92 to 0.96 (Table 1), whereas some groups exhibited significant differences (p < 0.05). The AW values fell within the characteristic range for semi-dry fermented sausages, specifically in the range of 0.90 < AW < 0.95 [22]. It is worth noting that when the AW drops to 0.86–0.88 during the aging process of Chinese dry-fermented sausages, the growth of most microorganisms can be effectively inhibited [20]. However, all groups were classified as having a high AW content with no threshold for effective inhibition of foodborne microbial growth (below 0.65) [23]. Zhang et al. [20] also reported that moisture content and AW in fermented sausages decrease as the fermentation period is prolonged. Namely, the microorganisms in the sausage will produce lactic acid and other chemicals, while Lactobacillus inhibits the growth of different bacteria [20]. It has also been reported that incorporating Chinese red and yellow wines in sausage recipes yields sausages with less water loss and higher AW values [24]. Ultimately, the substitution of salted duck egg by-product (LA) for salt-pickling HCs had no adverse effects on the AW of the sausages in this study. These results highlight the feasibility of LA as an alternative to salt, providing a sustainable and reusable substance for both quality and application in the HC process.

3.1.3. Color

The L* values of the sausages of all groups except the control group and the HCLA 100 group decreased with the increase in the duration of HC pickling in the LB (Table 1). There were significant differences (p < 0.05) between the groups. However, in the control and HCLA 100 groups, a slight increase was observed, followed by a decrease. The L* values for sausages in all groups were lowest for HCs with a 21-day pickling period in LA. These results also implied that pickling of HC in LA at a concentration of 25–75% for one day contributed to the improvement of the L* value of the sausages. The decrease in the L* value of sausages has been attributed to water loss, nitrite fermentation, or changes in light scattering on the sausage surface [25]. R. Huang et al. [26] have also revealed that the elevated L* value of low-sodium-treated sausages might be associated with improved water retention ability. However, this study failed to observe the effect of HC pickling with different salt concentrations of LA on the moisture content and L* value of the sausages.

Regarding a* and b* values, no degree of regularity was found in all group variations compared to the control group (Table 1), albeit with significant differences (p < 0.05) under some conditions. Moreover, the a* values of the sausages in this research were partially ascribed to the positive influence of the coloring agent (sodium nitrite) [21,22]. Specifically, sodium nitrite was converted to nitrous acid, whereby nitric oxide reacted with myoglobin and metmyoglobin in the meat to develop the characteristic red color (nitroso–myoglobin) of the sausage [27,28,29,30]. However, the sampling variations likely led to the a* and b* values changing irregularly among the groups. R. Huang et al. [26] also reported that the elevated b* values were probably related to the limited loss of sausage color at lower salt concentrations. Conversely, the shrinkage of muscle fragments and fibers at high salt concentrations promoted the leaching of myoglobin and residual hemoglobin with water during the heating process. This resulted in the b* values decreasing in the samples [26]. Moreover, it has been reported that b* values were related to yellow pigments generated by lipid oxidation products reacting with amines in the phospholipid head groups or amines in proteins [21]. Therefore, this study revealed that HCLAs did not interfere with the sausage coloring effect, and the trends of color changes observed in the groups agreed with those of the control group. Furthermore, the color values were exhibited to be similar to each other, resulting in differences in the color of the sausage groups that were not distinguishable to the naked eye [31].

3.1.4. TPA

The TPA values for all groups varied to different degrees without regular HC pickling with LA (as different durations and concentrations were used) (Table 2). There were significant differences (p < 0.05) between all groups and the control group. Specifically, hardness exhibited an increase followed by a decrease, and then a slight increase for the HCLA 25 and 100 groups, in relation to the duration of HC pickling with LB. Conversely, the HCLA 50 and 75 groups showed a decrease followed by a slight increase and then a slight decrease.

Table 2.

Effects of hog casings (HCs) pickled in salted duck egg by-product (liquid albumen; LA) for different durations before use in sausage production on the textual profile analysis (TPA) of the sausage.

In terms of springiness, the HCLA50 and 75 groups showed a slight increase on days 1 and 7 of HC pickling (Table 2). However, the other groups were similar to the control group, which showed a gradual decrease in springiness with an increase in the pickling period, and there were significant differences between the groups (p < 0.05).

Based on the results of this study, the values of cohesiveness, gumminess, and chewiness for each group increased with the HC pickling time (Table 2).

In addition, the cohesiveness and gumminess of all groups were higher and significantly different (p < 0.05) compared to the control group, except for the pickled conditions after 21 days. It is worth mentioning that HC showed higher gumminess values in groups HCLA 75 and 100 than the control group after pickling for 21 days, but there was no significant difference. The variations in chewiness were similar for the HCLA 75 and 100 groups to those described above but were significantly different (p < 0.05) compared to the control group. The changes observed in this study were attributed to the various changes in moisture content observed in the sausages encased by different HCLAs [21]. Notably, Xu et al. [30] reported that the inoculation of a complex fermenting agent in the formulation of Sichuan-style fermented sausages decreased the pH (the generation of acids such as organic acids) and the water-holding capacity of the proteins. The same authors also indicated that this would facilitate the acceleration of the drying process (reduction in water reduction in water content) and enhance the textural properties of the sausage. In a low-sodium Vienna sausage study, the use of different concentrations of KCl and glycine to reduce NaCl significantly reduced the hardness and firmness of the sausage significantly [32]. Low-salt meat products with the TPA properties declined due to the interactions between adjacent myosin monomers [28]. These interactions occurred due to electrostatic forces in their tails, forming regular self-assembling filamentous structures [28]. Consequently, this process reduces the solubility of myofibrillar proteins and contributes to their destabilization. Karla dos Santos et al. [27] reported on the application of alginate-encapsulated açaí oil microcapsules for fresh sausage production. Results indicated that the TPA of the sausages was more resistant due to the encapsulation of the microcapsules. In particular, addition of microcapsules altered the parameters of hardness, adhesiveness, and chewiness. Following the report by Zhao et al. [33], these relative TPA results were not directly indicative of the quality of the sausages concerned, which needed to be exploited in combination with the sensory evaluation results. In contrast, the small size of the particles from Pickering’s emulsion effectively fills the three-dimensional gel network matrix of the proteins, forming a finer gel structure, which enhances the texture of emulsified sausages [34]. The same authors suggested that oil droplet-based interfacial particles in Pickering’s emulsion augment the gelatinization and texture of emulsified sausages due to their interaction with myofibrillar proteins. In addition, using Taguchi orthogonality, Chung et al. [13] determined that the pork lean-to-fat ratio has an essential influence on mouthfeel in sausage recipes. Using consistent recipes for all sausages in this study (Table A1), HC had a negligible effect on the TPA in sausages, as indicated by the results described above. Therefore, HCs were pickled in LA for 1–21 days before sausage production. Different LA concentrations showed satisfactory performance in improving the TPA characteristics of the sausages to a certain extent. However, from a health point of view, we strongly recommend using pickling conditions with low salt concentrations for subsequent HC processing.

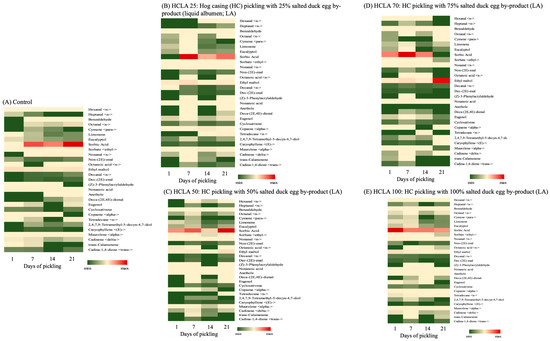

3.1.5. Aroma Heat-Map Analysis

Changes in the primary volatile component contents of flavor were similar in all groups of sausages manufactured by pickling HCs in LA (with different concentrations and pickling days) and the control (Figure 2A–E). The components contributing to the aroma of Chinese sausages, as a standard processed meat product, generally consist of a variety of volatile compounds. These compounds are classified into the following categories according to their chemical properties and flavor sources. (I) Aldehydes (such as hexanal, nonanal, and benzaldehyde), products of lipid oxidation and Strecker degradation, provide fat, grassy, and fruity flavors while serving as one of the most critical sources of flavor during meat processing [33,35]. (II) Maillard reaction (MR) derivatives (such as ethyl maltol or (Z)-3-phenylacrylaldehyde) derived from the heating reaction of proteins with reducing sugars give products with sweet and bakery fragrance characteristics [18,36]. It has been reported that phenylalanine (Phe) can enhance the aromatic strength of products by MR [37]. Moreover, Phe is transformed by microbial development to form phenylpyruvic acid, which is further oxidized to yield aldehydes, alcohols, acids, and key volatile compounds such as benzaldehyde, phenylacetic acid, and other substances with specific aromatic fragrances [30,38]. (III) Terpenes and sesquiterpenes (such as limonene, eugenol, caryophyllene, γ-terpinene, α-copaene, and cis-anethol) originate from the spice or the inner HCs, which express citrus-like, herbal, woody, sweet, pleasant aroma, or pungent flavor characteristics [37,38,39,40]. Hu et al. [38] also showed that 33 volatile compounds positively affected the fat odor in dried sausage flavors with different lactobacilli. Volatile compounds, such as cis-anethol and D-camphor, showed a positive correlation with the content of most free amino acids. (IV) The presence of partial-free, medium, and long-chain fatty acids (such as octanoic acid and nonanoic acid) and hydrocarbons reflected the changes in fatty acid-oxidized, β-oxidated, and aging states [33,40,41]. Specifically, these reactions form precursors of flavored substances in fermented sausages, such as aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, and esters [40,42]. In addition, microorganisms in Chinese fermented sausages significantly facilitated the hydrolysis of proteins and the generation of numerous flavor precursors [20]. Therefore, food scientists have focused on the development of natural functional food ingredients [19]. Specifically, it has been reported that using 3,4′-di-O-butanoylresveratrol (ED2) and 3-O-butanoylresveratrol (ED4) in different structural monomers of resveratrol butyrate esters reduces sodium nitrite by 83% in Chinese sausage recipes while inhibiting lipid oxidation and providing a degree of antibacterial activity [19].

Figure 2.

Effects of hog casings (HCs) pickled in salted duck egg by-product (liquid albumen; LB) and then used in sausage making on the aroma heatmap analysis of the sausage: (A) control; (B) HCLB 25: HC pickling with 25% LB; (C) HCLB 50: HC pickling with 50% LB; (D) HCLB 75: HC pickling with 75% LB; and (E) HCLB 100: HC pickling with 100% LB.

Interestingly, Cai et al.’s [37] study on the volatile contents of five-spice sausages provided evidence of an abundance of 2-methyl-1-butanol-D, 2-heptanone, 1-butanol, 2-pentanone, butyl benzene, and 2-pentanol-D. The same authors also indicated that these substances imparted a fruity and sweet flavor to the sausages. Microbial or endogenous proteases (fructose-bisphosphate-α, photosynthesized hydrogenase, and creatine kinase M−type) hydrolyze the meat proteins during the initial stage of Chinese sausage fermentation (the first 10 days) to develop and stabilize the flavor [43,44]. Consequently, the composition and content of the food matrix in sausage, including proteins and lipids, interact with flavor compounds and influence the retention of aroma compounds and release of flavors [39]. Furthermore, Chen et al. [40] reported that one of the major factors influencing the distinctive aroma of Sichuan- and Cantonese-style sausages was the different distribution of microbes. Despite the benefits of fermented sausages through microorganisms, Enterococcus has been known to cause increased levels of biogenic amines (such as histamines) in the product and poses a potential health risk to the consumer [45]. Zhou et al. [39] also noted that sausage recipes that are not sufficiently acidified may be at risk of higher enterobacterial counts during the drying process. Notably, all sausages in this study were frozen and preserved upon completion of production, which also contributed to delaying the onset of lipid oxidation. This prevents any adverse effects on the flavor of traditional Chinese (fermented) sausages caused by prolonged storage at ambient temperature. Based on the above results, the application of HCLA in sausage production does not adversely affect the flavor of the sausage.

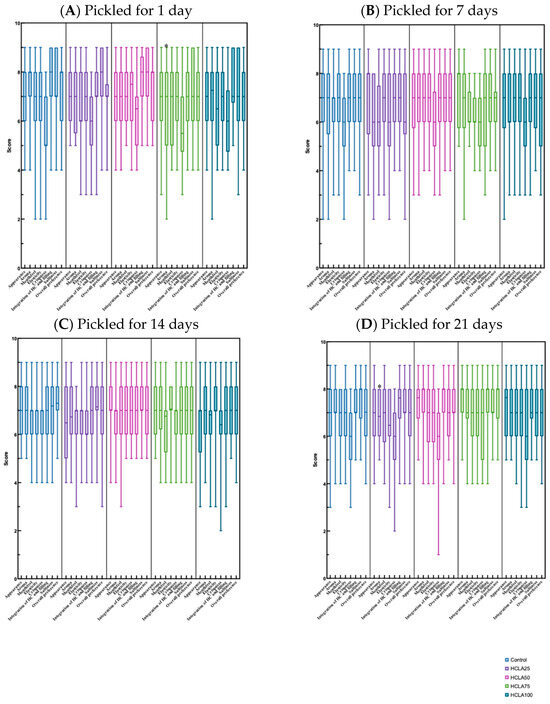

3.2. Sensory Evaluation

The sensory evaluation results revealed that all sausage groups received similar scores to the control group (Figure 3A–D). The numerical differences were minor despite significant differences (p < 0.05) being observed in several evaluation indicator scores compared to the control group. The HCLA50 scored higher than the control group in terms of mouthfeel, elasticity, and crispness, regardless of whether the HCs were pickled for 1–21 days. Despite a slight difference reported in sensory evaluation scores for all sensory attributes between laboratory-scale and commercially produced low-salt sausages (with a lower score for saltiness), no significant differences were observed [32]. As mentioned above, the present study only used HCs pickled in different LAs (concentrations and days) for sausage production without altering the sausage recipe. Hence, there were no significant changes in the sensory properties of the recipes [23,31]; rather, the primary differences were due to the HCs. Therefore, it is possible to substitute the use of LA for the pickling of HCs with a high salt solution without affecting the quality indicators of the final sausage product in terms of the number of pickling days. In practical operation, considering time savings, curing HCs in 50% LA takes only 1–7 days to obtain HCs that would be satisfactory for consumer use in the production of sausage products.

Figure 3.

Effects of hog casings (HCs) pickled in salted duck egg by-product (liquid albumen; LB) on their sensory properties for the manufacture of sausages: (A) pickled for 0 days, (B) pickled for 7 days, (C) pickled for 14 days, and (D) pickled for 21 days. * Represents a significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to the control group.

3.3. Proximate Composition

The HCs obtained in the control and HCLA50 groups did not affect the proximate composition of the sausage products produced by the same recipe (Table A2). Therefore, the findings of this study exhibited a similar tendency to those previously published [19,24,27,46]. It is worth mentioning that the sodium content of the HCLA50 group was also lower than that of the control group, creating a niche product for consumers with limited daily sodium consumption. Specifically, identifying ways to improve digestive characteristics and sensory qualities (taste balance and saltiness perception) and extend the shelf-life of reduced/low-sodium content sausages contributes to a viable solution for the meat processing industry. These methods can meet consumer demand and requirements for a healthier product [6,23,26,32].

4. Conclusions

In total, 50% LA has the potential to substitute traditional brine pickling for HCs, achieving a beneficial outcome for residual resource recycling without adversely affecting the quality indicators of sausage products. It was found that LA possesses practical value and potential for application in meat processing. Furthermore, the process of HC pickling and preservation conditions under LA can be optimized in the future, and its application value is expected to broaden in the food processing industry. However, the limitations of this study lie in the laboratory-scale nature of the current results, necessitating further consideration for validation under industrial conditions and the conduct of larger-scale testing. Meanwhile, future research directions could also incorporate shelf-life evaluation, microbial safety analysis, and optimization studies utilizing response surface methodology and other artificial intelligence tools. Consequently, it would be advantageous for food-related industries to attain sustainable development in environmental, economic, and social aspects. This can be achieved by contributing to emission reduction and pollution control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and data curation, W.-C.C. and W.-T.H.; methodology, software, and formal analysis, W.-T.H. and P.-H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, W.-C.C., W.-T.H. and P.-H.H.; writing—review and editing, W.-C.C. and P.-H.H.; visualization, P.-H.H.; supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition, W.-C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LA | Liquid albumen |

| HC | Hog casing |

| TPA | Textural profile analysis |

| CAGR | Conservative compound annual growth rate |

| DW | Deionized water |

| AW | Water activity |

| N | Newton |

| SPME | Solid-phase microextraction |

| DVB/PDMS | Divinylbenzene/polydimethylsiloxane |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| RI | Retention index |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| FFNSC | Flavors/fragrances |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| WVP | Water vapor permeability |

| MR | Maillard reaction |

| Phe | Phenylalanine |

| ED2 | 3,4′-di-O-butanoylresveratrol |

| ED4 | 3-O-butanoylresveratrol |

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of Chinese sausage recipes.

Table A1.

List of Chinese sausage recipes.

| Ingredient | Weight | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (g) | (%) | ||

| Lean pork | 20,000 | 69.79 | |

| Back fat | 5000 | 17.45 | |

| Seasonings | Salt | 358.3 | 1.25 |

| Sugar | 2278.47 | 7.95 | |

| Monosodium glutamate (MSG) | 126.1 | 0.44 | |

| Five-spice powder | 11.5 | 0.04 | |

| White pepper | 74.5 | 0.26 | |

| Cooking rice wine | 753.8 | 2.63 | |

| Polyphosphate | 51.6 | 0.18 | |

| Sodium nitrite | 2.5 | 0.01 | |

| Total | 28,656.77 | 100 | |

Table A2.

Effects of hog casing (HC) pickled in salted duck egg by-product (liquid albumen; LA) for different days before use in sausage production on the proximate composition.

Table A2.

Effects of hog casing (HC) pickled in salted duck egg by-product (liquid albumen; LA) for different days before use in sausage production on the proximate composition.

| Item | Control | HCs Pickled in 50% Salted Duck Egg By-Product (LA) for 7 Days HCLA50 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Each Serving (40 g) | Per 100 g | Each Serving (40 g) | Per 100 g | |

| Calories (kcal) | 115.8 | 289.6 | 130.5 | 326.3 |

| Protein (g) | 5.5 | 13.7 | 5.2 | 13.1 |

| Fat (g) | 9.3 | 23.3 | 14.4 | 28.6 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 3.5 | 8.6 | 4.4 | 11.1 |

| Trans fat (g) | 0 | |||

| Carbohydrate (g) | 2.5 | 6.2 | 1.7 | 4.3 |

| Sugar (g) | 2.6 | 6.5 | 2.4 | 6 |

| Sodium (g) | 235 | 587 | 214 | 535 |

The proximate analyses were conducted just once (n = 1). Consequently, no statistical analyses were carried out.

References

- Wongnen, C.; Panpipat, W.; Saelee, N.; Rawdkuen, S.; Grossmann, L.; Chaijan, M. A novel approach for the production of mildly salted duck egg using ozonized brine salting. Foods 2023, 12, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Wu, N.; Yao, Y.; Chen, S.; Xu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Tu, Y. Effects of ammonium chloride on physicochemical properties, aggregation behavior and microstructure of duck egg yolk induced by salt. LWT 2025, 229, 118151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMarket. Salted Duck Egg Analysis Uncovered: Market Drivers and Forecasts 2025–2033; PRDUA Research & Media Private Limited: Pune, Maharashtra, India, 2025; Available online: https://www.datainsightsmarket.com/reports/salted-duck-egg-1236257#segments (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Wang, H.-C.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, J.-W. The Current Production and Export Situation of the Duck Egg Industry in Taiwan. FFTC Agricultural Policy Platform (FFTC-AP). 2025. Available online: https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/3766 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Vidyarthi, S.K.; Xu, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, H. A comprehensive review on salted eggs: Quality formation mechanisms, innovative pickling technologies and value-added applications. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1409–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Lu, W.; Zalewski, P.; He, J.; Li, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, C.; Wu, J.; Chen, H.; et al. Innovative approaches to sodium reduction in pickled foods: A review of recent developments. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 163, 105133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suurs, P.; Barbut, S. Collagen use for co-extruded sausage casings—A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 102, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global-Market-Insights. Sausage Casings Market Size; Global Market Insights Inc.: Selbyville, DE, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/sausage-casings-market (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Anuradha. Natural Sausage Casings Market Research Report 2033; Growth Market Reports: Ontario, CA, USA, 2024; 288p, Available online: https://growthmarketreports.com/report/natural-sausage-casings-market (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Venugopal, V. Green processing of seafood waste biomass towards blue economy. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 4, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Huang, Y.-T.; Ciou, J.-Y.; Cheng, C.-M.; Wang, G.-T.; You, C.-M.; Huang, P.-H.; Hou, C.-Y. Circular economy and sustainable recovery of taiwanese tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) byproduct—The large-scale production of umami-rich seasoning material application. Foods 2023, 12, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-H.; Chen, Y.-W.; Chen, C.-H.; Fan, H.-J.; Hsieh, C.-W.; Tain, Y.-L.; Tsai, W.-T.; Shih, M.-K.; Hou, C.-Y. Characterization and evaluation of the adsorption of uremic toxins through the pyrolysis of pineapple leaves and peels and by forming a bio-complex with sodium alginate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 302, 138843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, P.-L.; Lufaniyao, K.-S.; Gavahian, M. Development of Chinese-style sausage enriched with djulis (Chenopodium formosanum Koidz) using taguchi method: Applying modern optimization to indigenous people’s traditional food. Foods 2024, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-H.; Chen, Y.-W.; Shie, C.-K.; Chen, S.-Y.; Lee, B.-H.; Yin, L.-J.; Hou, C.-Y.; Shih, M.-K. Chinese sausage simulates high calorie–induced obesity in vivo, identifying the potential benefits of weight loss and metabolic syndrome of resveratrol butyrate monomer derivatives. J. Nutr. Metab. 2025, 2025, 8414627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 22nd ed.; Latimer, G.W., Jr., Latimer, G.W., Jr., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.-W.; Tsai, C.-L.; Chen, C.-J.; Li, P.-L.; Huang, P.-H. Insights into the effects of multiple frequency ultrasound combined with acid treatments on the physicochemical and thermal properties of brown rice postcooking. LWT 2023, 188, 115423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.-H.; Wu, Y.-Y.; Lin, C.-M.; Chen, H.-L.; Chen, M.-H.; Shih, M.-K.; Hou, C.-Y. Characterization of the effects of micro-bubble treatment on the cleanliness of intestinal sludge, physicochemical properties, and textural quality of shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Food Chem. 2025, 472, 142909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.-H.; Huang, P.-H.; Lo, C.-Y.; Chang, W.-C. Metabolomic analysis elucidates the dynamic changes in aroma compounds and the milk aroma mechanism across various portions of tea leaves during different stages of oolong tea processing. Food Res. Int. 2025, 209, 116203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Chen, Y.; Fan, H.; Chen, S.; Tain, Y.; Hsieh, C.; Hou, C.; Shih, M. Application of resveratrol butyric acid derivatives in the processing, physicochemical characterization, and the shelf-life extension of Chinese sausages low in sodium nitrite. J. Food Saf. 2024, 44, e13144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jia, J.; Qian, Q.; Ma, H.; Zhou, J.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, Q.; Zeng, Q.; Li, Q.; et al. Effect of isolated bacteria on nitrite degradation and quality of Sichuan dry sausages. LWT 2024, 212, 117039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.; Yang, X.; Tao, J.; Zhan, F.; Qiu, Y.; Jin, J.; Zhao, L. Novel biodegradable polyamide 4/chitosan casing films for enhanced fermented sausage packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2025, 47, 101444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Mijiti, M.; Xu, Z.; Abulikemu, B. Effect of a combination of probiotics on the flavor profiling and biogenic amines of composite fermented mutton sausages. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 104835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibt, A.C.M.D.; Nerhing, P.; Pinton, M.B.; Santos, S.P.; Leães, Y.S.V.; Oliveira, F.D.C.D.; Robalo, S.S.; Casarin, B.C.; Dos Santos, B.A.; Barin, J.S.; et al. Green technologies applied to low-NaCl fresh sausages production: Impact on oxidative stability, color formation, microbiological properties, volatile compounds, and sensory profile. Meat Sci. 2024, 209, 109418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, J.-X.; Chen, S.-Y.; Li, C.-H.; Huang, Y.; Chang, H.-J. Quality properties of Chinese Sichuan-style sausages as affected by Chinese red wine, yellow rice wine and beer. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 3291–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wei, H.; Luo, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Xie, N. Enhancing the textural properties of Tibetan pig sausages via zanthoxylum bungeanum aqueous extract: Polyphenol-mediated quality improvements. Foods 2025, 14, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Fang, Y.; Yin, H.; Zhong, Y.; Lu, W.; Deng, Y. Al-optimized synergy of KCl and κ-carrageenan in low-sodium sausages: Integrated enhancement of saltiness perception, gel stability, and protein digestibility. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 168, 111574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karla dos Santos, A.; da Silva, N.M.; Matiucci, M.A.; de Marins, A.R.; de Campos, T.A.F.; de Brito Sodré, L.W.; Bezerra, R.A.D.; Alcalde, C.R.; Feihrmann, A.C. Use of encapsulated açaí oil with antioxidant potential in fresh sausage. LWT 2024, 204, 116469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Kong, B.; Cao, C.; Sun, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q. Application of lysine as a potential alternative to sodium salt in frankfurters: With emphasis on quality profile promotion and saltiness compensation. Meat Sci. 2024, 217, 109609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Wang, L.; Ge, Y.; An, Y.; Sun, X.; Xue, K.; Xie, H.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Chen, L. Screening, identification, and application of superior starter cultures for fermented sausage production from traditional meat products. Fermentation 2025, 11, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Qiu, W.; Liu, Y.; Gong, F.; Liu, Q.; Chen, J.; Tang, Y.; Su, C.; Tang, J.; Zhang, D.; et al. Exploring the regulation of metabolic changes mediated by different combined starter cultures on the characteristic flavor compounds and quality of Sichuan-style fermented sausages. Food Res. Int. 2025, 208, 116114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Ye, R.; Zhuang, H.; Rong, Z.; Fang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Jin, Z. Physicochemical properties and sensory evaluation of mesona blumes gum/rice starch mixed gels as fat-substitutes in Chinese Cantonese-style sausage. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriwattana, S.; Chokumnoyporn, N.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Reduced-sodium Vienna sausage: Selected quality characteristics, optimized salt mixture, and commercial scale-up production. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 3939–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; An, Y.; Dong, Z.; Sun, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Yang, B.; Yan, J.; Fang, B.; Ren, F.; et al. Comparative analysis of commercially available flavor oil sausages and smoked sausages. Molecules 2024, 29, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shen, J.; Meng, G.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, G.; Wang, X. Characterization of wheat bran nanocellulose and its application in low-fat emulsified sausage. Cellulose 2024, 31, 11101–11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Sun, J.; Chen, H.; Sun, B. Characterization of key volatile flavor compounds in dried sausages by HS-SPME and safe, which combined with GC-MS, GC-O and OAV. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 133, 106438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleicher, J.; Ebner, E.E.; Bak, K.H. Formation and analysis of volatile and odor compounds in meat—A review. Molecules 2022, 27, 6703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Zeng, Y.; Zhu, K.; Peng, Y.; Xv, P.; Dong, P.; Qiao, M.; Fan, W. Characterization of the quality and flavor in Chinese sausage: Comparison between Cantonese, five-spice, and mala sausages. Foods 2025, 14, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ren, J.; Chen, Q.; Kong, B. Unraveling the difference in flavor characteristics of dry sausages inoculated with different autochthonous lactic acid bacteria. Food Biosci. 2022, 47, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, N.; Li, S.; Pan, X.; Wang, S.; Qiao, X. Development of volatiles and odor-active compounds in Chinese dry sausage at different stages of process and storage. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2021, 10, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yan, F.; Qu, D.; Wan, T.; Xi, L.; Hu, C.Y. Aroma characterization of Sichuan and Cantonese sausages using electronic nose, gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, gas chromatography-olfactometry, odor activity values and metagenomic. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, L.; Pan, D.; Guo, T.; Ren, H.; Wang, L. Role of Lactobacillus plantarum with antioxidation properties on Chinese sausages. LWT 2022, 162, 113427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Qian, M.; Cheng, F.; Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Tian, J.; Jin, Y. The effect of lactic acid bacteria on lipid metabolism and flavor of fermented sausages. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, B.; Zhou, T.; Gao, H.; Wu, L.; Zhao, D.; Wu, J.; Li, C. Flavor evolution of normal- and low-fat Chinese sausage during natural fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2023, 169, 112937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Sheng, B.; Gao, H.; Nie, X.; Sun, H.; Xing, B.; Wu, L.; Zhao, D.; Wu, J.; Li, C. Effect of fat concentration on protein digestibility of Chinese sausage. Food Res. Int. 2024, 177, 113922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.-S.; Wang, C.-Y.; Hu, Y.-Y.; Yang, L.; Xu, B.-C. Enhancement of fermented sausage quality driven by mixed starter cultures: Elucidating the perspective of flavor profile and microbial communities. Food Res. Int. 2024, 178, 113951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, C.; Zhang, P.; Wang, F.; Zhang, T.; Ma, Y.; Xu, M. Formulation optimization and quality evaluation of walnut protein sausage based on fuzzy mathematics sensory evaluation combined with random centroid optimization. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).