Abstract

This paper proposes a hybrid photovoltaic (PV) Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) strategy to tackle local optima, slow dynamic response, and steady-state oscillations under partial shading conditions (PSC). The method combines an Improved Whale Migration Algorithm (IWMA) with a variable-step Incremental Conductance (VINC) technique. IWMA employs a Tent–Logistic–Cosine chaotic initialization, dynamic weight coefficients, random feedback, and a distance-sensitive term to enhance population diversity, strengthen global exploration, and reduce the risk of convergence to local maxima. The VINC stage adaptively adjusts the step size based on incremental conductance, providing fine local refinement around the global maximum power point (GMPP) and suppressing steady-state power ripple. Extensive MATLAB/Simulink simulations with multiple random trials show that the proposed IWMA-VINC strategy consistently outperforms the Whale Migration Algorithm (WMA), A Simplified Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm Combining Natural Selection and Conductivity Incremental Approach (NSNPSO-INC), and the Grey Wolf Optimizer and Whale Optimization Algorithm (GWO-WOA) under both static and dynamic PSC, achieving the highest tracking accuracies (99.74% static, 99.44% dynamic), higher average output power, shorter convergence times, and the smallest variance across trials. These results demonstrate that IWMA-VINC offers a robust and high-performance MPPT solution for PV systems operating in complex illumination environments.

1. Introduction

Under the guidance of China’s “dual-carbon” strategic goals, which aim to achieve carbon peaking and carbon neutrality within a defined time frame, the rapid development of clean energy technologies has become a national priority. Among various renewable energy sources, PV power generation is widely recognized for its environmental friendliness, scalability, and long-term sustainability [1,2,3,4]. To fully exploit these advantages, PV systems must deliver high conversion efficiency, reduced levelized cost of energy, and stable operation under diverse environmental conditions. PV modules are inherently sensitive to external factors such as solar irradiance, ambient temperature, and partial shading caused by clouds, buildings, or other obstacles. These factors lead to highly nonlinear and time-varying output characteristics, particularly in the power–voltage (P–U) and current–voltage (I–U) curves of PV arrays [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Under uniform irradiation, the P–U curve exhibits a single peak, and conventional MPPT algorithms can reliably track this GMPP. Under PSC, traditional MPPT algorithms may easily converge to a local maximum power point (MPP) rather than the true GMPP, reducing the effective energy yield of the system.

Classical MPPT methods, including Perturb and Observe (P&O) [14,15], Incremental Conductance (INC) [16,17], and the hill-climbing technique [18], are widely used due to their simple structure and ease of implementation. However, under PSC or rapidly changing environmental conditions, these methods often exhibit slow convergence, significant steady-state oscillations, and limited robustness. To mitigate these drawbacks, various improved schemes—such as variable step-size algorithms, adaptive perturbation laws, and sliding-mode-based controllers—have been proposed. Although these enhancements can improve either convergence speed or steady-state accuracy, they still struggle to reliably escape local maxima and to maintain high tracking performance over a broad range of operating scenarios.

In recent years, a number of advanced MPPT strategies have been introduced to strengthen global search capability under PSC. Nonetheless, from an engineering implementation perspective, these methods still present clear limitations. The NSNPSO-INC in [19] is highly sensitive to population size, learning factors, and random initialization. The improved hybrid whale–PSO scheme in [20] couples two metaheuristic algorithms and introduces additional control parameters, which can become problematic under high switching-frequency operation. The variable-step GWO-WOA methods in [21] effectively reduce ripple and overshoot but require relatively high computational resources and exhibit longer response times, limiting their suitability in fast-varying irradiance conditions. The Long Short-Term Memory and Improved Honey Badger Algorithm (LSTM–IHOA) hybrid approach in [22] demands large training datasets, offline learning, and substantial on-chip resources, and its ability to generalize across different PV configurations and unseen shading patterns has not been fully demonstrated. Finally, although the GWO-VINC algorithm in [23] improves tracking speed and efficiency compared with standalone GWO and VINC, issues related to scalability, parameter sensitivity, and robustness under broader field conditions remain insufficiently addressed.

Within this context, the WMA has attracted attention as a population-based metaheuristic optimizer inspired by the collective migration behavior of whale pods. Its hierarchical navigation structure and migration mechanism are well suited to global optimization in complex, multi-modal search spaces such as the P–U characteristic under PSC. Nevertheless, conventional WMA can suffer from insufficient population diversity at initialization, an imbalanced trade-off between exploration and exploitation, and reduced local search accuracy in later iterations, all of which limit its effectiveness for reliable GMPP tracking.

To overcome these shortcomings, this paper proposes an IWMA that employs a Tent–Logistic–Cosine chaotic mapping for population initialization and a dynamic parameter optimization strategy for the migration process. Building on this improved global optimizer, a hybrid MPPT control scheme integrating IWMA with a small variable step-size incremental conductance method is developed. In the proposed framework, IWMA is responsible for global GMPP search under PSC, while the VINC algorithm performs precise local refinement of the operating point in the vicinity of the estimated GMPP, thereby enhancing both tracking speed and steady-state performance.

Based on the above analysis, the main novel contributions compared with existing MPPT algorithms are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- An IWMA-based global optimizer is constructed using a Tent–Logistic–Cosine chaotic initialization mechanism, which enhances population diversity and improves global exploration ability.

- (2)

- A dynamic parameter adjustment strategy is designed to balance exploration and exploitation during whale migration, thereby reducing the tendency to fall into local optima and enhancing convergence stability.

- (3)

- A VINC algorithm is integrated with IWMA to provide precise local tracking of the GMPP, effectively suppressing steady-state oscillations and improving tracking accuracy compared with standalone metaheuristic MPPT schemes and conventional INC-based methods.

- (4)

- In the 2024b MATLAB/Simulink environment, comprehensive simulation studies were carried out for both static and dynamic partial shading scenarios. The results show that the proposed improved whale migration algorithm–variable step-size incremental conductance hybrid strategy outperforms WMA, NSNPSO, and GWO-WOA in terms of tracking accuracy, convergence speed, and robustness.

These innovations make the IWMA-VINC algorithm particularly suitable for real-world PV applications in which arrays are frequently subjected to partial shading and rapidly changing environmental conditions.

2. PV System Model

2.1. Mathematical Representation of PV Cells

The operation of a PV cell is fundamentally governed by the photovoltaic effect. When incident photons with sufficient energy strike the semiconductor material, they excite electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, creating electron–hole pairs. Under the influence of the built-in electric field in the p–n junction, these carriers are separated and collected at the terminals, generating a photocurrent that can be delivered to an external load [24].

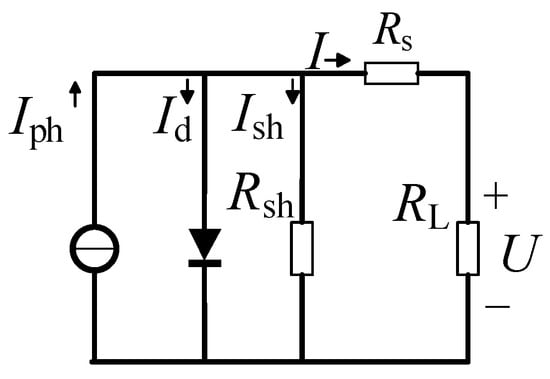

The electrical behavior of a practical PV cell can be represented by an equivalent circuit consisting of a current source in parallel with a diode, a shunt resistance, and a series resistance. This model captures both the ideal photo-generation mechanism and the non-ideal effects, such as leakage currents and internal ohmic losses. Figure 1 shows the equivalent circuit of a single PV cell.

Figure 1.

The Equivalent Circuit of PV Cell.

Based on this model, the output current of a PV cell under a given terminal voltage can be expressed as:

where I represents the load current; Iph denotes the photogenerated current; Id signifies the diode current; Ish indicates the shunt leakage current; Rs represents the equivalent series resistance; Rsh is the equivalent shunt leakage resistance; RL and represents the load resistance.

2.2. Modeling of PV Arrays

A PV array is formed by connecting multiple PV cells in series and parallel. Its engineering mathematical model is given as follows [25]:

where Um and Im represent the voltage and current at maximum output power, respectively; Uoc and Isc and represent the open-circuit voltage and short-circuit current, U is the load voltage; and C1 and C2 are correction coefficients.

2.3. Output Characteristics of PV Arrays

To analyze the output characteristics of the PV array and to verify the effectiveness of the proposed MPPT strategy, a simulation model is built in MATLAB/Simulink by combining the PV cell model with the series–parallel interconnection structure. Various irradiance patterns are applied to emulate uniform and partially shaded conditions. The corresponding I–U and P–U curves are obtained by sweeping the terminal voltage of the array over its operating range. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the illumination conditions and characteristic parameters used in the simulations.

Table 1.

Illumination Conditions.

Table 2.

Characteristic Parameters of PV Arrays.

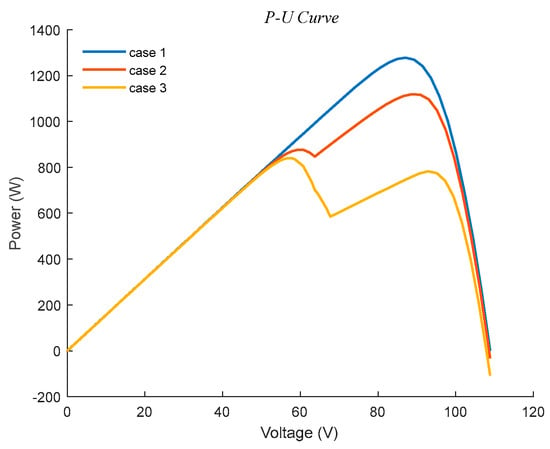

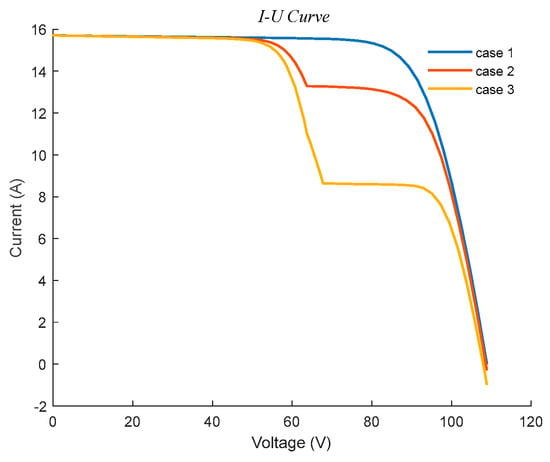

Leveraging the established mathematical representation of PV cells, the electrical output characteristics of a 3 × 2 PV array have been modeled and simulated in the Simulink environment. The simulation captures both the P–U and I–U relationships under specified operating conditions. The resulting P–U characteristics are shown in Figure 2, which illustrates the distinctive multi-peak power profile, while the corresponding I–U characteristics are presented in Figure 3, depicting the array’s current response over the operating voltage range.

Figure 2.

P–U Characteristic Curves of PV Arrays under Different Conditions.

Figure 3.

I–U Characteristic Curves of PV Arrays under Different Conditions.

Under PSC, the PV array experiences a marked current reduction in shaded cell strings, creating a bottleneck that limits the current output of the illuminated modules within the same series branch. This mismatch forces the power–voltage characteristics to exhibit multiple distinct power levels across different voltage intervals, which appear as prominent multiple peaks on the P–U curve. As shown in Figure 2, the GMPP is located at (87.12 V, 1277.65 W) under uniform irradiation. As shading becomes more severe, the GMPP shifts to (90.90 V, 1116.5 W) for partial shading condition 1 and further to (92.96 V, 789.1 W) for partial shading condition 2, clearly illustrating how shading patterns influence both the maximum extractable power and its corresponding operating voltage.

This current reduction in shaded PV modules under PSC imposes a current-limiting bottleneck on other series-connected units within the same string. As a result, the entire series chain is forced to operate at the reduced current level of its most heavily shaded module, producing the characteristic multi-step profile observed in the I–U curve. As illustrated in Figure 3, this staircase pattern arises because each voltage interval corresponds to the activation or deactivation of different module subgroups within the partially shaded array configuration.

3. IWMA-VINC Algorithm

3.1. A VINC Algorithm

While conventional MPPT algorithms are characterized by their straightforward computational requirements, they inherently suffer from a limitation imposed by their fixed step size. This constraint creates a fundamental trade-off between the speed of tracking dynamic changes and the magnitude of steady-state power oscillations around the operating point. To mitigate this issue, an INC strategy utilizing a small, adaptive step size is implemented. This method enables a more precise and refined search for the GMPP. The core principle of the INC algorithm lies in its decision-making logic, which ascertains the attainment of the maximum power point based on the condition defined in Equation (5).

where and represent the output current and voltage of the PV array, respectively.

If , then indicates operation on the left side of GMPP, and the system needs to increase the step size;

If , then indicates operation on the right side of GMPP, and the system needs to decrease the step size;

If , then indicates the system is operating at GMPP.

The calculation formula for the VINC can be expressed as:

where is the voltage increment per step; m is the step size gain coefficient; is the minimum step size.

3.2. Improved Strategy for Whale Migration Optimization Algorithm

The WMA is a metaheuristic optimization method inspired by the collective migration behavior of whale groups. In WMA, a population of candidate solutions adjusts its position in the search space according to migration rules that simulate the guidance of leader whales and the following behavior of ordinary whales. Through iterative updates, the population converges toward optimal regions of the search space.

Although WMA exhibits good global search capability, the conventional algorithm may still encounter several issues when applied to complex multi-modal problems such as GMPP tracking under PSC. These issues include insufficient diversity in the initial population, an unbalanced transition from exploration to exploitation, and reduced effectiveness in local refinement near the optimum. To overcome these limitations, two key enhancements are introduced to form the IWMA:

- (1)

- Tent–Logistic-Cosine Chaotic Initialization Mapping

Instead of using purely random initialization, IWMA employs a composite chaotic map that combines Tent, Logistic, and Cosine mappings to generate the initial population. Chaotic sequences possess ergodicity and pseudo-randomness, which help distribute initial individuals more uniformly across the search space and avoid clustering. The resulting initial population improves the coverage of the solution space and enhances the probability of locating the global optimum. After generating the chaotic sequence, it is linearly mapped to the feasible bounds of each decision variable, ensuring that all individuals satisfy the problem constraints.

Map the chaotic sequence to the solution space:

where x(i) represents the sequence of random factors; r is the control parameter; y(i) is the simplified form of the Logistic map; Wi denotes the position of an individual whale; U and L are the upper and lower bounds of the solution space, respectively.

- (2)

- Dynamic Parameter Optimization

In the original WMA, some control parameters remain fixed during the optimization process, which may lead to either premature convergence or excessive wandering. In IWMA, these parameters are dynamically adjusted according to the iteration index and the current distribution of the population. At the early stage, larger exploration parameters encourage broad search and help the population escape local optima. As the iterations proceed, the parameters are gradually tuned to strengthen exploitation around promising regions.

The migration mechanism is organized in a hierarchical structure in which leader whales with superior fitness guide the movement of follower whales. The positions of follower whales are updated by combining the influence of leader whales, the population mean, and randomized perturbations. Meanwhile, leader whales perform refined searches around the best-known solutions, with additional random feedback terms introduced to preserve diversity and avoid stagnation.

The position update formula for follower whales in the IWMA is as follows:

In the formula, WMean represents the average position of leader whales; NL is the number of leader whales; Wbest denotes the optimal position within the population; Npop is the total number of whales in the population; r(t) is the feedback-based random factor; and are dynamic weight coefficients; rbase is the random intensity, γ is the aggregation amplification coefficient; k is the sensitivity coefficient; D(t) is the current population diversity; Dinit is the initial population diversity; λ is the over-steepness coefficient; t and T are the current iteration number and total iteration number, respectively. WMean,j(t) and Wi,j(t) represent the component within j-th dimension of the average position of the follower population and the component within j-th dimension of the position of the i-th follower, respectively.

where is the distance-sensitive coefficient; γ is the adjustment coefficient; r1 and r2 are random disturbances, respectively.

Through these improvements, IWMA achieves a more reasonable balance between exploration and exploitation, exhibits stronger global search ability, and provides a more reliable global optimization engine for MPPT applications under PSC.

3.3. IWMA-VINC Strategy

To achieve fast and accurate MPPT under both static and dynamic partial shading conditions, this paper integrates the IWMA global optimizer with a VINC algorithm, forming the hybrid IWMA-VINC control strategy. The overall structure adopts a two-layer architecture: IWMA performs a coarse global search to locate the vicinity of the GMPP, while the VINC algorithm carries out fine local tracking to lock onto the exact MPP.

To maintain persistent and precise tracking of the GMPP under dynamically changing atmospheric conditions, the controller incorporates an environmental detection and response mechanism. During operation, it continuously acquires the PV array terminal voltage and current, from which it computes the instantaneous power and incremental conductance values. Variations in solar irradiance and array output are monitored in real time. When the observed changes exceed a predefined threshold—indicating a possible shift of the GMPP—an adaptive decision protocol determines whether the IWMA global search procedure should be re-executed.

In the IWMA stage, each whale represents a candidate operating point, and the fitness function is defined as the PV array output power. The initial population is constructed using the Tent–Logistic–Cosine chaotic mapping to enhance population diversity. Through iterative updates governed by the improved migration rules and dynamically adjusted parameters, IWMA converges toward the operating point with maximum power. The best solution obtained in this stage is then passed to the VINC stage as the initial condition.

In the subsequent VINC stage, the VINC algorithm refines the operating point around the IWMA-estimated GMPP. The adaptive step-size mechanism enables rapid adjustment when the operating point is far from the exact MPP and progressively smaller perturbations as it approaches the optimum, resulting in minimal steady-state power oscillations.

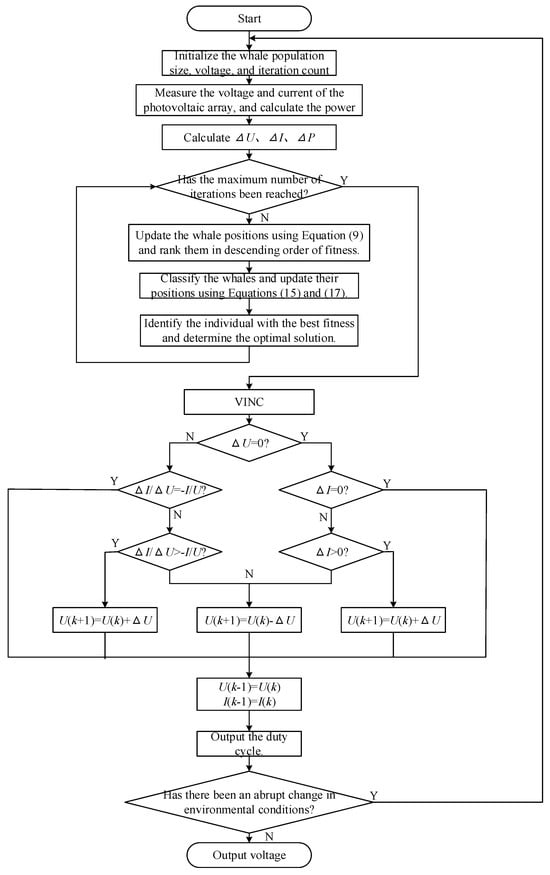

The main procedural steps of the IWMA-VINC algorithm can be summarized as follows in Figure 4:

Figure 4.

Algorithm Flowchart Based on IWMA-VINC.

- (1)

- Initialization: Set system parameters, IWMA control parameters, and VINC step-size limits. Measure the initial voltage and current of the PV array.

- (2)

- Environmental monitoring and decision making: Continuously monitor solar irradiance and array output power. When the measured variations exceed a predefined threshold, activate the decision protocol to determine whether the IWMA global search needs to be invoked.

- (3)

- GMPP search with IWMA: When the triggering condition is satisfied, construct the initial population via the Tent–Logistic–Cosine chaotic mapping, evaluate fitness values based on output power, and iteratively update whale positions using the improved migration rules until the termination criterion is met. Record the best operating point as the estimated GMPP.

- (4)

- Local refinement with VINC: Starting from the estimated GMPP, execute the VINC algorithm to further adjust the operating point. Update the duty cycle of the DC–DC converter according to the sign and magnitude of the conductance error until the tracking error falls below a specified threshold.

- (5)

- Continuous monitoring and re-triggering: Continue to monitor irradiance and output power. If subsequent significant deviations are detected, return to Step 2 and re-enter the IWMA stage; otherwise, maintain VINC-based local tracking.

This cooperative mechanism effectively combines the strong global exploration capability of IWMA with the high-precision local tracking of VINC, thereby improving both the dynamic response and steady-state performance of the MPPT system. The triggering criterion used to decide when to re-execute the IWMA global search is defined as follows:

4. Simulation Experiment Verification

4.1. Simulation Setup

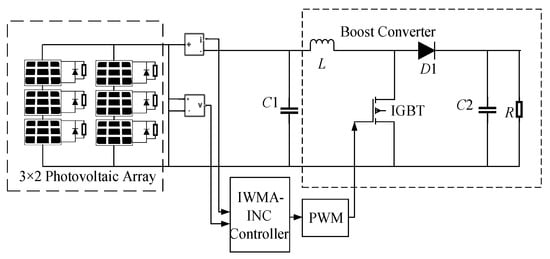

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed IWMA-VINC strategy, a complete PV generation system is modeled in MATLAB/Simulink. The system consists of a PV array, a Boost DC–DC converter, an IWMA-VINC MPPT controller, and a resistive load, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Block Diagram of MPPT Control.

The PV array model is constructed using the equivalent circuit representation described in Section 2 and configured according to the electrical parameters in Table 2. The Boost converter is designed to match the rated power and voltage levels of the PV array. Its key parameters, including inductance, capacitance, and switching frequency, are listed in Table 3. The duty cycle of the converter is adjusted by the MPPT controller to regulate the operating point of the PV array.

Table 3.

Boost Converter Parameters.

The control parameters of the IWMA-VINC algorithm are summarized in Table 4. These parameters are selected to ensure a good trade-off between tracking performance and computational complexity, enabling real-time implementation on typical digital control platforms.

Table 4.

IWMA-VINC Algorithm Control Parameters.

To assess the robustness of each MPPT strategy, all simulation scenarios were repeated over 20 independent trials using different random seeds in MATLAB. For each trial, the stochastic components of the algorithms were re-initialized with a distinct seed, while the irradiation and temperature profiles were kept identical. In every run, we recorded the steady-state output power, tracking time, and tracking accuracy. For each algorithm and operating condition, the results reported in the following subsections and tables correspond to the sample mean and standard deviation computed over these 20 trials.

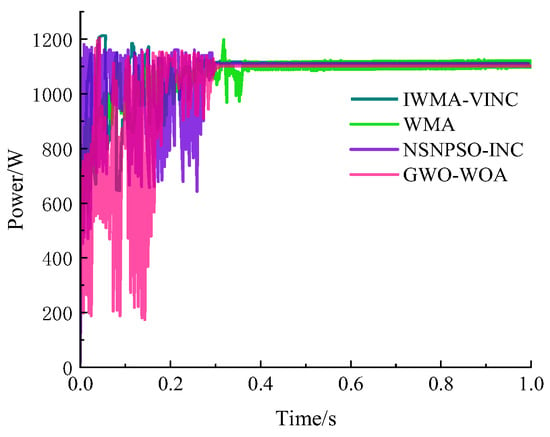

4.2. Static Partial Shading Simulation

The effectiveness of the proposed methodology was evaluated under the non-uniform irradiation pattern defined as Case 2 in Table 1. The resultant power tracking performance, illustrated in Figure 6, demonstrates the algorithm’s capability to rapidly and accurately converge to the operating point of maximum power generation. For quantitative assessment, Table 4 provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of steady-state output power, tracking time, and tracking accuracy for the four algorithms under static partial shading. The listed values represent the mean ± standard deviation over 20 independent trials with different random seeds, highlighting the superior convergence speed, tracking precision, and operational stability of the proposed approach relative to conventional techniques under identical partial shading conditions.

Figure 6.

Comparison of Different Algorithms under Static Non-Uniform Illumination.

As seen in Figure 6, the traditional optimization strategies WMA, NSNPSO-INC and GWO-WOA exhibit pronounced power oscillations and slow convergence, with their output trajectories showing large overshoot and long transient intervals before roughly stabilizing. These fluctuations indicate weaker tracking capability and poorer robustness to rapid changes, which would reduce the effective energy capture of the system. In contrast, IWMA-VINC quickly converges to the maximum power level and maintains an almost flat response with minimal ripple over the entire time horizon, demonstrating faster dynamic response, better stability and a higher steady-state power output. This highlights that IWMA-VINC not only accelerates convergence but also significantly improves control precision compared with the other methods.

The quantitative results further highlight the limitations of the other algorithms and the advantages of IWMA-VINC. WMA produces the lowest output power (1075.97 W) and clearly lags in dynamics and precision, with the longest tracking time (0.42 s) and the poorest accuracy (96.37%), accompanied by large fluctuations in all three indices. NSNPSO-INC and GWO-WOA improve the output power to 1099.31 W and 1103.88 W, respectively, but still require longer tracking times (0.33–0.34 s) and exhibit lower tracking accuracies (98.46% and 98.87%), together with noticeably larger standard deviations than IWMA-VINC. In contrast, IWMA-VINC achieves the fastest response (0.27 s) and the highest tracking accuracy (99.74%) with extremely small dispersion, while its steady-state power is only about 1% lower than the maximum value among all methods. This indicates that IWMA-VINC provides the best overall trade-off between energy capture, convergence speed, and control precision, and exhibits the most stable and reliable performance.

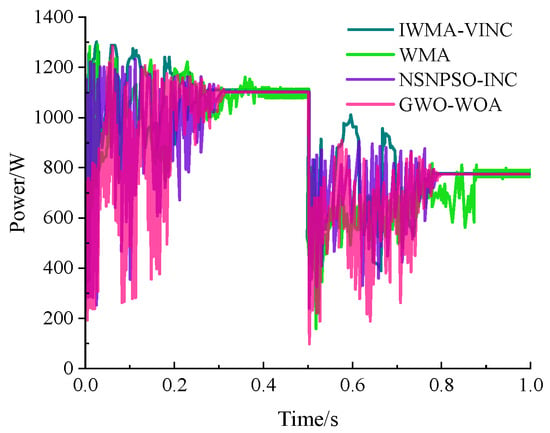

4.3. Dynamic Partial Shading Simulation

To accurately emulate realistic time-varying shading patterns and thoroughly validate the algorithm’s adaptive capabilities, a dynamic illumination transition scenario was configured. The experimental setup starts with the Case 3 illumination parameters (Table 1) at t = 0 s, followed by an abrupt transition to the Case 2 configuration at t = 0.5 s. This dynamic shading sequence, illustrated in Figure 7, effectively tests the algorithm’s response to sudden environmental changes. The quantitative performance metrics under these dynamic partial shading conditions are summarized in Table 5, where each entry represents the mean ± standard deviation over 20 independent trials, providing comprehensive evaluation metrics for comparative analysis.

Figure 7.

Comparison of Different Algorithms under Dynamic Shading Conditions.

Table 5.

Static Tracking Condition.

As shown in Figure 7, the conventional methods WMA, NSNPSO-INC, and GWO-WOA all suffer from large power oscillations and slow resettling both before and after the irradiance step change at 0.5 s. In the first stage, these algorithms exhibit evident overshoot and frequent excursions far from the maximum power point, indicating low tracking precision and poor damping. When the operating point suddenly shifts to a lower power level, their responses again display deep dips and long-lasting fluctuations, which prolong the transient process and reduce the average captured power. By contrast, IWMA-VINC quickly locks onto the initial maximum power with a much smoother profile and, after the step change, rapidly converges to the new steady value with minimal overshoot and ripple. This demonstrates that IWMA-VINC has stronger adaptability to abrupt environmental changes, faster dynamic response, and significantly better stability than the other methods.

As summarized in Table 6, the three algorithms still exhibit clear drawbacks compared with IWMA-VINC. WMA delivers the poorest performance, with the lowest output power (751.54 W), the longest tracking time (0.48 s), and the lowest tracking accuracy (95.24%), while its large standard deviations in all indices indicate pronounced instability. NSNPSO-INC and GWO-WOA improve the steady-state power to around 773–777 W and enhance accuracy to 97.92% and 98.42%, respectively, but they still require longer tracking times (0.36–0.37 s) and show noticeably larger fluctuations than IWMA-VINC. In contrast, IWMA-VINC achieves the highest average output power (784.68 W), the fastest tracking response (0.29 s), and the best tracking accuracy (99.44%) with very small variances, demonstrating superior dynamic performance, higher precision, and stronger robustness than the other methods.

Table 6.

Dynamic Tracking Performance.

5. Conclusions

Under partial shading conditions, the P–U characteristic of PV arrays becomes highly nonlinear and exhibits multiple local maxima, which significantly complicates maximum power point tracking and can cause substantial energy loss if the GMPP is not correctly identified. To address this problem and enhance the energy harvesting efficiency of PV systems, this paper proposes a hybrid MPPT strategy that combines an IWMA-VINC.

The main outcomes of this study can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- By introducing a Tent–Logistic–Cosine chaotic initialization mapping and a dynamic parameter adjustment scheme, the IWMA achieves higher population diversity and a more effective exploration–exploitation balance than the conventional WMA, enabling more reliable localization of the global MPP under complex partial shading patterns.

- (2)

- Integrating the IWMA with a VINC algorithm yields a two-layer MPPT framework in which the IWMA provides global search capability and VINC performs precise local refinement. The adaptive step-size mechanism in the VINC stage effectively suppresses steady-state power oscillations while maintaining fast tracking dynamics.

- (3)

- Extensive MATLAB/Simulink simulations with multiple random trials show that the proposed IWMA-VINC strategy consistently outperforms WMA, NSNPSO-INC, and GWO-WOA under both static and dynamic PSC. IWMA-VINC achieves the highest tracking accuracies of 99.74% (static) and 99.44% (dynamic), delivers higher average output power, and shortens convergence time compared with the three algorithms, while exhibiting the smallest variance in all performance indices across trials.

Future research will focus on experimental validation of the IWMA-VINC strategy using a hardware prototype, real-time implementation on embedded control platforms, and extension of the method to larger PV arrays and different topologies. In addition, integrating grid-side constraints, thermal effects, and long-term aging into the optimization framework will be investigated to further enhance the practicality and robustness of the proposed MPPT approach in real-world photovoltaic applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.X., P.H., W.Q. and J.L.; methodology, Y.X., P.H., W.Q. and J.L.; validation, Y.X., P.H., W.Q. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.X., P.H., W.Q. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Belghiti, H.; Kandoussi, K.; Chellakhi, A.; Mchaouar, Y.; El Otmani, R.; Sadek, E.M. Performance optimization of photovoltaic system under real climatic conditions using a novel MPPT approach. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2024, 46, 2474–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sooriamoorthy, D.; Manoharan, A.; Sivanesan, S.K.; Lun, S.K.; Cheong, A.C.H.; Perumal, S.K.S. Optimizing Solar Maximum Power Point Tracking with Adaptive PSO: A Comparative Analysis of Inertia Weight and Acceleration Coefficient Strategies. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.H.; Ang, S.P.; Dani, M.N.; Rahman, M.I.; Petra, R.; Sulthan, S.M. Optimizing step-size of perturb & observe and incremental conductance MPPT techniques using PSO for grid-tied PV system. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 13079–13090. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelraouf, B.; Serhoud, H.; Nacer, H. Comparative study of sliding mode and incremental conductance for maximum power point tracker for photovoltaic array. Prz. Elektrotech. 2023, 99, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennai, M.Y.; Tedjini, H. Integrating hybrid artificial ecosystem with P&O MPPT for enhanced fuel cell performance in microgrid systems. Electr. Eng. 2025, 107, 8059–8084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Bass, O.; Masoum, M.A.S. An improved genetic algorithm based fractional open circuit voltage MPPT for solar PV systems. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 1535–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percin, H.B.; Caliskan, A. Whale optimization algorithm based MPPT control of a fuel cell system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 23230–23241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wen, X.; Hu, Z.; Yang, H.; He, Z. A maximum-power-point tracking method based on constant conduction time control with constant voltage output for magnetic field energy harvesters in the saturated region. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 10716–10720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangrody, R.; Taheri, S.; Cretu, A.M.; Pouresmaeil, E. An improved PSO-based MPPT technique using stability and steady state analyses under partial shading conditions. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2023, 15, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, H.; Sidhom, L.; Chihi, I. Systematic literature review and benchmarking for photovoltaic MPPT techniques. Energies 2023, 16, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncir, N.; El Akchioui, N.; El Fathi, A. Enhancing photovoltaic system modeling and control under partial and complex shading conditions using a robust hybrid DE-FFNN MPPT strategy. Renew. Energy Focus 2023, 47, 100504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santosh, B.S.S.; Mohammed, T.A.M.; Rao, K. Optimal initial duty for improved MPPT under change in irradiances and partial shading conditions. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 045307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satif, A.; Mekhfioui, M.; Elgouri, R. Advanced techniques for maximizing photovoltaic power: A Systematic literature review. Sci. Afr. 2025, 30, e02989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, F.; Aydoğmuş, Z.; Tür, M.R. Analysis of open circuit voltage MPPT method with analytical analysis with perturb and observe (P&O) MPPT method in PV systems. Electr. Power Compon. Syst. 2024, 52, 1528–1542. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.G.; Uddin, M.A.; Ferdous, A.I.; Sadeque, M.G. Enhanced Maximum Power Point Tracking Using Hybrid GA and PSO Algorithms for Solar PV Systems. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, M.; Shahin, A.; Eskender, S.; Elsayes, M.A. Hybrid global search with enhanced INC MPPT under partial shading condition. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.F.; Mahmoud, M.M.; Alnami, H.; Mbadjoun Wapet, D.E.; Ardjoun, S.A.E.M.; Mosaad, M.I.; Abdelfattah, H. A new adaptive MPPT technique using an improved INC algorithm supported by fuzzy self-tuning controller for a grid-linked photovoltaic system. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0293613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajmi, B.N.; Ahmed, N.A.; Abdelsalam, I.; Marei, M.I. A Robust MPPT Algorithm for PV Systems Using Advanced Hill Climbing and Simulated Annealing Techniques. Electronics 2025, 14, 3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.Z.; Zhong, Y.M. NSNPSO-INC: A simplified particle swarm optimization algorithm for photovoltaic MPPT combining natural selection and conductivity incremental approach. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 2169–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Ni, Z.; Li, F. Maximum power point tracking control of photovoltaic systems using a hybrid improved whale particle swarm optimization algorithm. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2025, 47, 1789–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemmit, A.; Loukriz, A.; Belhouchet, K.; Alharthi, Y.Z.; Alshareef, M.; Paramasivam, P.; Ghoneim, S.S. GWO and WOA variable step MPPT algorithms-based PV system output power optimization. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wei, H.; Wu, S.; Pan, J.; Chen, T.; Zhang, H. Research on MPPT control strategy based on LSTM and IHOA algorithm. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2026, 250, 112097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Lei, G.; Cai, L.; He, C.; Dai, N.; Jiang, Z.; Li, S. MPPT control technology based on the GWO-VINC algorithm. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1205851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksek, G.; Mete, A.N. A P&O based variable step size MPPT algorithm for photovoltaic applications. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. 2023, 36, 608–622. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, Z.; Jiao, H. SMGSA algorithm-based MPPT control strategy. J. Power Electron. 2024, 24, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).