Abstract

Peptidoglycan (PG) is a polymer that makes up the cell wall of most bacteria. In this study, the peptidoglycan of Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393 was extracted, and its prebiotic function as well as its effects on intestinal health and inflammation reduction in a colitis murine model were investigated. PG was extracted from L. casei ATCC 393 using the ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic method. A structural characterization and assessment of its antioxidant capacity were subsequently performed to evaluate its functional properties. In a dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis model, dietary supplementation with PG (100 mg/kg) demonstrated significant protective effects. Specifically, the PG intervention group exhibited reduced inflammatory symptoms, improved disease activity indices, suppressed weight loss, and colon shortening compared to the DSS-induced group. Intestinal barrier injury was reversed and the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio was increased. These clinical improvements were accompanied by decreased circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β). These findings revealed that PG modulated gut microbial ecology by enhancing bacterial diversity and promoting the enrichment of beneficial taxa, particularly the Lachnospiraceae and Lactobacillus species. Additionally, PG intervention increased fecal short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) concentrations, especially the concentration of propionic acid and butyric acid, which increased by 13% and 42%, respectively, compared to the DSS-induced group, suggesting enhanced microbial metabolic activity. Furthermore, these findings emphasize the potential of peptidoglycan as a functional component for preventing colitis through microbial-mediated pathways. This study underscores the prebiotic promise of peptidoglycan in the development of interventions targeting intestinal inflammation and supports its further exploration as a functional agent for promoting human health.

1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) represents a chronic relapsing condition characterized by non-specific inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) constituting its principal clinical subtypes [1]. As a heterogeneous condition arising from intricate interactions between multigenic and multifactorial disorder, IBD pathogenesis is strongly associated with the disruption of microbial homeostasis, a hallmark of intestinal dysbiosis [2]. Common clinical features include symptoms such as increased stool frequency, urgency, and altered stool consistency, reflecting compromised intestinal function [3]. Recent studies underscore the critical role of intestinal microbial dysbiosis in IBD development, driving intensified research into microbiota-directed therapeutic modalities. Current strategies encompass both functional foods intervention (e.g., administration of probiotic strains and dietary interventions) and clinical procedures (e.g., fecal microbiota transplantation and antibiotic regimens) aimed at modulating the balance of gut microbiota [4]. Thus, the development of novel potent natural anti-inflammatory compounds is critically needed.

Peptidoglycan (PG), as one of the most abundant microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) in lactic acid bacteria (LAB), serves as a primary structural component of the bacterial cell wall. It plays an essential role in maintaining the mechanical integrity of the cell membrane and has been closely associated with the anti-inflammatory properties exhibited by specific LAB strains [5]. Structurally, the glycosidic backbone of PG is composed of alternating β-1,4-glycosidically linked disaccharide units: N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc or NAG) and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc or NAM). This repeating structure forms a highly conserved molecular architecture that is characteristic of bacterial PG [6,7]. The conventional method for PG isolation involves chemical lysis of bacterial cells to remove proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and teichoic acids, followed by dialysis to purify the PG [8]. However, this process typically requires approximately two weeks and suffers from limitations such as prolonged duration and low yield. In contrast, mechanical-assisted extraction applies high-intensity physical forces—such as high-speed vibration, grinding, or shearing—directly to microbial cell walls at ambient temperature [9]. This non-chemical treatment precisely disrupts cellular structures and facilitates PG release, while minimizing structural degradation commonly induced by high temperatures or harsh chemical treatments. Among the non-contact mechanical approaches, ultrasonic-assisted extraction employs ultrasonic cavitation to disrupt cell walls, thereby enhancing extraction efficiency, shortening processing time, and better preserving PG molecular integrity. Bio-assisted extraction could utilize enzymatic hydrolysis to liberate PG from the cell wall, which offers superior selectivity and milder reaction conditions compared to chemical methods, thereby more effectively maintaining the native structure of PG [10]. Based on these considerations, the present study adopted an integrated ultrasonic-enzymatic extraction approach for isolating peptidoglycan from Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393. This combined method simplified operational procedures, shortened extraction time, and improved the structural preservation of the isolated PG.

PG demonstrates multifaceted bioactive properties such as immune regulation, inflammation suppression, intestinal barrier enhancement, and prebiotic function. PG engages with Toll-like receptors (TLRs) on host antigen-presenting cells, thereby inducing the expression of cell surface receptors to regulate cellular functions. This interaction promotes the release of cytokines and chemokines from host cells, synergistically coordinating innate and adaptive immune responses [11,12]. Experimental studies further indicate that under certain conditions, PG can suppress the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6 and TNF-α) in macrophages and interact with upstream signaling mediators in inflammatory pathways, thereby reducing colonic inflammation in murine colitis models [13]. Additionally, PG displays broad-spectrum molecular recognition capabilities through interactions with conserved protein motifs (e.g., LysM, OmpA-C, SH3b, SPOR, and NOD) [14], which enhance its effect in mitigating enteric pathogen colonization and reinforcing intestinal barrier integrity [15,16,17]. Recent studies have revealed that specific fragments of extracted PG from LAB exhibit selective binding to ubiquitin ligases, thereby suppressing neoplastic cell growth and suggesting the promising application potential of the colorectal cancer intervention [18]. Given its structural versatility and pleiotropic bioactivities, PG emerges as a promising candidate for applications such as immune modulation enhancement, anti-inflammatory formulations, antimicrobial agents, and gut microbiota modulation in functional food development.

Despite the critical role of PG in modulating inflammatory processes and metabolic functions, PGs derived from different bacterial strains exhibit significant differences. These differences are manifested in three key aspects: (1) the configuration of polysaccharide backbones, (2) the stereochemistry and sequence of amino acid side chains, and (3) the degree and topology of peptide cross-linking [17,19]. These structural distinctions are further amplified by enzymatic or chemical modifications occurring post-biosynthesis, contributing to functional diversification. For instance, while the conserved amino acid sequence (L-Ala-γ-D-Glu-X-D-Ala) in most Lactobacillus. lactis and lactobacilli species contains a diamino acid (typically L-Lys) at the third residue (X), L. plantarum uniquely incorporates meso-diaminopimelic acid (mDAP) at this position, a structural adaptation with profound implications for host–microbe interactions [7]. Thus, considering these structural specificities, the modulation of the immune system and the metabolic regulatory effects of PG exhibit significant strain dependency rather than universal functionality. Given these structural divergences, illustrating the precise mechanisms by which LAB-derived PG influences gastrointestinal inflammation and metabolic homeostasis remains an area requiring further systematic investigation.

This study investigates the structural characterization of PG derived from L. casei ATCC 393 and evaluates its prebiotic potential in alleviating dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in a murine model. PG was efficiently isolated using an ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic extraction protocol, followed by comprehensive structural profiling through Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The antioxidant capacity of PG was quantified by establishing in vitro assays, including DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)), hydroxyl radical, superoxide anion, and ferrous ion-chelating and radical-scavenging activity. Furthermore, in vivo efficacy was assessed by monitoring DSS-challenged C57BL/6 mice, with a specific focus on colonic histopathology, gut microbiota modulation (16S rRNA sequencing), and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production (GC-MS). Our findings demonstrate that L. casei-derived PG exhibits dose-dependent anti-inflammatory effects and significantly restores dysbiotic microbiota composition, while enhancing SCFA biosynthesis. This work provides foundational evidence for the translational applications of PG as a multifunctional ingredient in nutraceutical development and preventive dietary strategies targeting inflammatory bowel diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material and Chemicals

The L. casei ATCC 393 strain used in this study was obtained from the Biotechnology Laboratory of the School of Chemical Engineering, Tianjin University. The strain was stored in MRS medium with 50% (v/v) glycerol (−80 °C) and the strain was activated by transferring samples to fresh MRS medium and incubating at 37 °C for 24 h.

2.2. Peptidoglycan Extraction and Purification

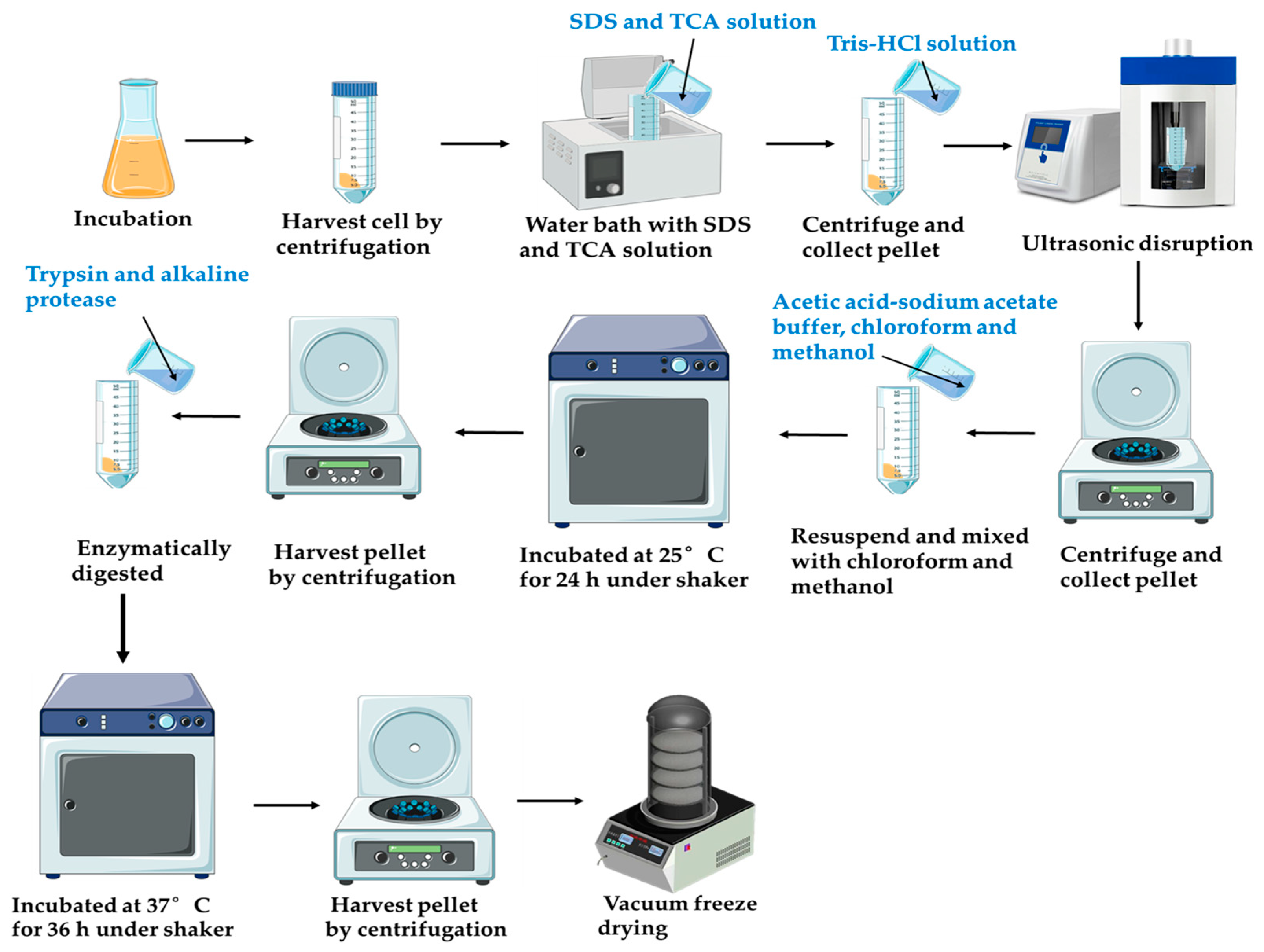

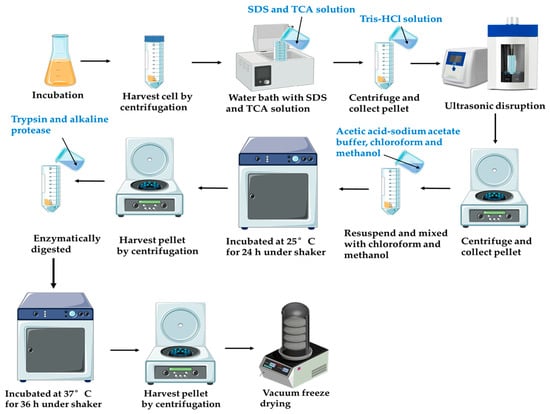

The extraction of PG was performed using an ultrasonic-assisted enzymatic approach. The schematic diagram of the peptidoglycan extraction process is shown in Figure 1. The experimental protocol was adapted from a previous method with appropriate modifications to align with the current research objectives [20]. L. casei ATCC 393 was inoculated (2% w/v) into sterile MRS broth and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, with growth kinetics monitored throughout the incubation period. After the 24 h cultivation period, cells were harvested by centrifugation (4000× g, 15 min, 4 °C) and washed three times with sterile physiological saline (0.9% w/v NaCl) to remove residual media components.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the peptidoglycan extraction process.

The pellet was resuspended in 4% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and boiled for 5 min. After centrifugation (8000× g, 20 min), the pellet was treated with 15% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (TCA) at a 1:10 (w/v) ratio, incubated in a water bath (100 °C) for 30 min, and immediately chilled. The TCA-treated residue was collected by centrifugation (8000× g, 20 min) and subjected to ultrasound (15 min) to fragment cell wall matrices. The pellet was washed three times with sterile ultrapure water under centrifugation (8000× g, 15 min).

The pellet was resuspended in an acetic acid–sodium acetate buffer (0.05 M acetic acid, 0.02 M sodium acetate, pH 4.6) and mixed with chloroform/methanol (4:5:10, v/v/v). The mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 24 h under a shaker, followed by centrifugation (8000× g, 15 min, 4 °C). Sequential washes with methanol (2–3 times) and distilled water (3 times) were performed to remove residual solvents. The washed pellet was enzymatically digested in Tris-HCl buffer (0.1 M, pH 8.0) containing trypsin and alkaline protease at a 1:10 (w/v) ratio, with continuous agitation (37 °C, 36 h). After digestion, insoluble debris was removed by low-speed centrifugation, and the supernatant was discarded after high-speed centrifugation (10,000× g, 20 min, 4 °C). The purified PG was washed extensively with deionized water (4–5 times) and lyophilized for long-term storage.

2.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Analysis

Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy was performed on an iS50 spectrometer (FEI, Waltham, MA, USA) to analyze the PG. For sample preparation, 2 mg of PG was pressed with potassium bromide (KBr) at a 1:100 (w/w) mass ratio and made into tablets. A background reference spectrum was obtained using pure KBr pellets prepared under identical conditions. Spectral acquisition spanned the mid-infrared region (400–4000 cm−1).

2.4. Method for Detecting Peptidoglycan pH Changes During Enzymatic Hydrolysis

During the hydrolysis process, the pH of the reaction mixture was systematically monitored at 2 h intervals using a pH meter. The stabilization of pH values within ±0.05 units over consecutive intervals was interpreted as a terminal marker of reaction completion.

2.5. Helical Conformation Analysis of Peptidoglycan

The Congo red (CR) binding assay was performed to assess the triple-helical structure of the peptidoglycan (PG) sample. Specifically, 8.0 mg of PG was dissolved in 2.0 mL of deionized water (ddH2O), followed by the addition of 2.0 mL of 0.05% (w/v) Congo red solution to achieve a final PG concentration of 2 mg/mL. The mixture was then titrated with 1 mol/L NaOH solution to generate a series of final NaOH concentrations (0, 0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20, 0.25, 0.30, 0.35, 0.40, 0.45, and 0.50 mol/L). Aliquots of each concentration were transferred to quartz cuvettes, and full-wavelength scanning from 500 to 700 nm was conducted using a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer (Kyoto, Japan).

2.6. Method for Testing Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant activity of peptidoglycan was assessed as previously described [21], the antioxidant detection method was used to measure the radical-scavenging activities of polysaccharide solutions at different concentrations (0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 mg/mL) after 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h of enzymatic hydrolysis. The free radical-scavenging capacity of peptidoglycan was measured by using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)), hydroxyl radical-scavenging ability, superoxide anion-scavenging activity (SOSA), and ferrous ion-chelating activity.

2.7. Animal Experiments

The institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yi Shengyuan Gene Technology (Tianjin) Co., Ltd. (Approval No. YSY-DWLL-2023164) gave approval for this work. Six- to eight-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Beijing Huafukang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) and housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) environment with temperature control (20–26 °C) and relative humidity control (40–70%).

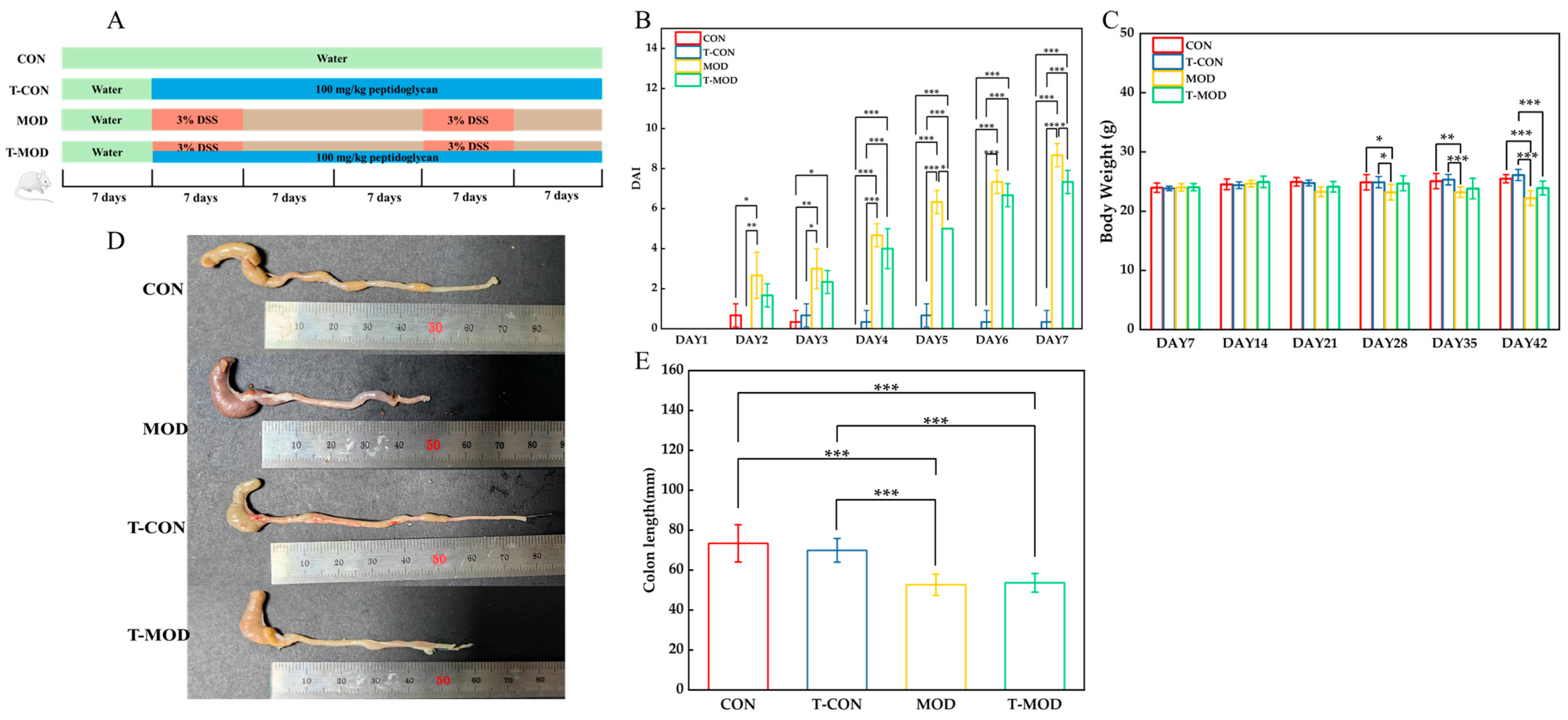

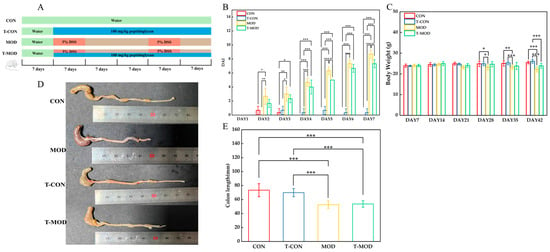

After 7 days of adaptation, the mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups using a computer-generated randomization schedule stratified by body weight to ensure equivalent baseline distributions across groups. The mice were initially randomly divided into four experimental groups (n = 10 per group): (1) the control group (CON), (2) the PG-feed control group (T-CON), (3) the dextran sulfate sodium salt (DSS)-induced group (MOD), and (4) the PG intervention group (T-MOD) [22]. The treatment of each group and the intervention strategy is shown in Figure 4A. During the 8–14 and the 29–35 days, 3% (w/v) DSS was added to the water for the MOD group and T-MOD group mice. After 7 days of adaptation, the T-CON group and T-MOD group were treated with PG. The dose of Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393-derived PG (100 mg/kg) was selected based on previous studies [13,23]. After a six-week intervention period, mice feces were collected for further analysis. Whole blood was collected and centrifuged to collect serum. Some tissues and serum were quickly transferred to a −80 °C freezer after being flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen.

2.8. Assessment of Colitis Symptoms

Body weight was monitored every week, and the disease activity index (DAI) of each group was monitored after DSS was induced [24]. The DAI scoring standard is shown in the following table (Table 1). When the mice were euthanized, their colon lengths were measured.

Table 1.

The DAI standard of each group.

2.9. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

The colon tissues of each group were fixed in formalin solution, then embedded, sliced, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin reagent. After staining, the sections were observed by a full scan system [25].

2.10. Biochemical Assays

Blood samples were collected from the eyeballs of mice, and the serum samples of each group were separated and collected. The concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were detected using an ELISA kit (Yanqi Biology Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

2.11. 16S rRNA Gene and Bioinformatics Analysis

The samples of the mice were treated and collected to extract the total bacterial genomic DNA using the previously described techniques [26]. Shortly, 3–4 variable segments of each 16S rDNA specimen were amplified with the primers 338F and 806R by a PCR thermocycler. The platform for analysis was furnished by Majorbio Bio-pham Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China.

2.12. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Determination

The extraction of fecal SCFAs was performed as previously described [27]. The SCFA contents of acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, and pentanoic acid were measured by a gas chromatography (GC)—mass spectrometry (MS) instrument (Thermo, Trace 1300, USA; Thermo, ISQ LT, USA) equipped with an HP-INNOWAX column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), as preciously described [26].

2.13. Statistical Analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s test were conducted using Origin2018 (OriginLab, version 10.3.0.180, Northampton, MA, USA) and SPSS (SPSS software, version 24.0). The cut-off values for statistical significance were set at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Purification and Characterization of Peptidoglycan

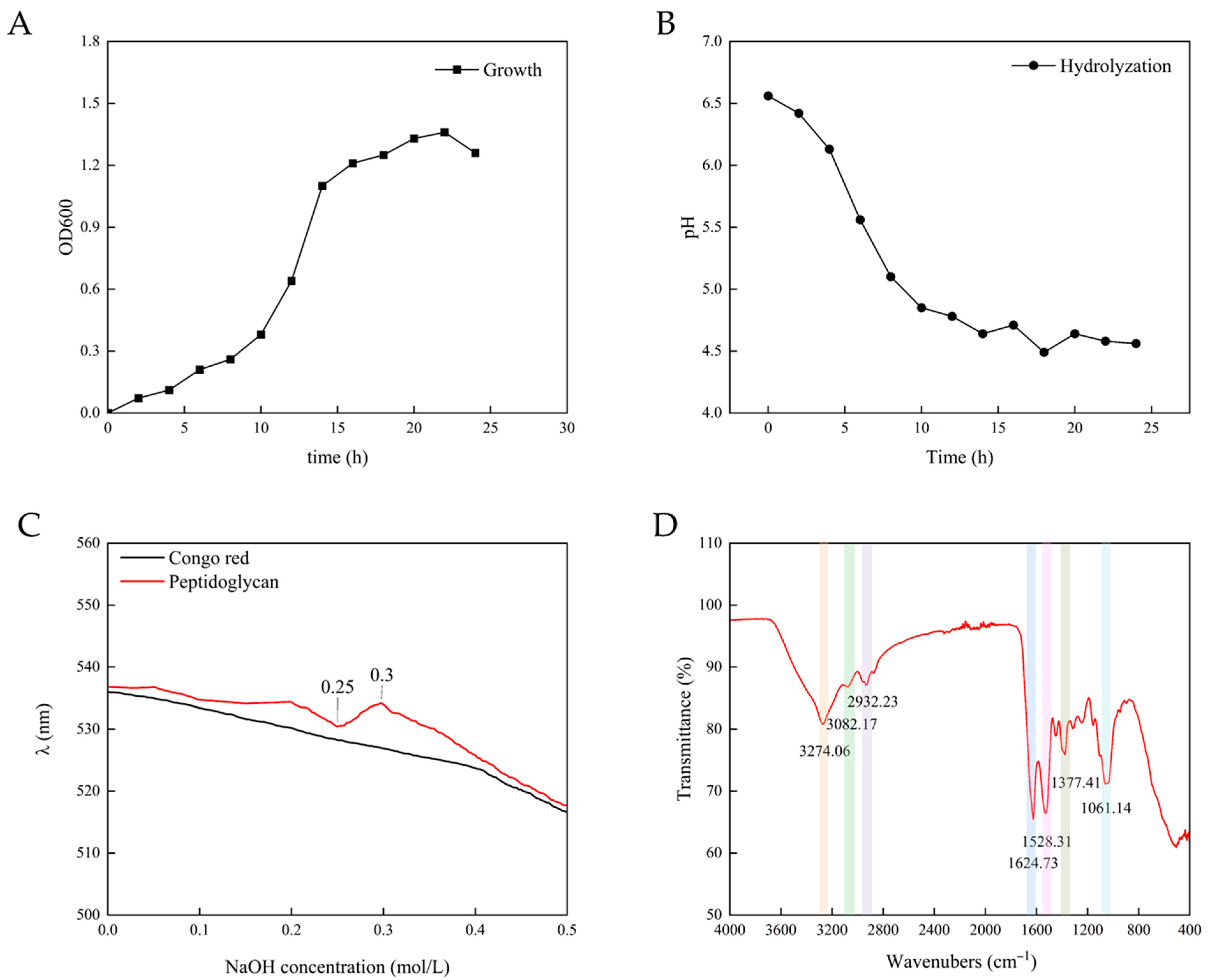

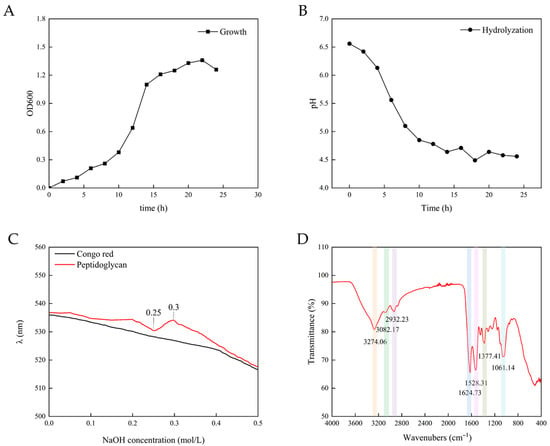

Bacterial cultures were collected during the exponential or stationary phase for the extraction of PG. In the exponential phase, rapid cell division leads to active cell wall remodeling and continuous PG production. In the stationary phase, bacterial cells develop a stabilized PG architecture and accumulate maximal biomass prior to nutrient depletion, thereby optimizing both PG yield and extraction efficiency. However, the decaying phase triggers autolysin activation, which risks PG hydrolysis and compromises product integrity. As shown in Figure 2, Lactobacillus cultures entered the stationary phase at approximately 20 h under standardized conditions. Therefore, cells harvested between 16 and 20 h were selected for PG extraction to optimize yield while maintaining structural stability.

Figure 2.

(A) The growth of Lactobacillus casei ATCC 393; (B) pH change during PG hydrolysis; (C) UV absorption spectrum of PG; and (D) FT-IR analysis of PG.

3.2. pH Change of Peptidoglycan During Enzymatic Hydrolysis

When PG was hydrolyzed by enzymes, the solution became clearer and the particles smaller. The size change of the particles indicated that key structural connections—both the protein cross-links and the sugar chain bonds (β-1,4-glycosidic bonds)—were being cut. Notably, the particle size of PG after ultrasound was discontinuous [28]. As shown in Figure 2, the pH of the solution progressively dropped from 6.5 to approximately 4.5 during hydrolysis, with the rate of decline decelerating over time. The pH fell quickly at first but slowed over time. As pH gradually decreased beyond the enzyme’s optimal range, enzymatic activity diminished, leading to reduced hydrolysis efficiency. The reaction was considered complete when the pH stabilized near 4.5, indicating a balance between substrate depletion and autolytic termination. The reason for the decline in pH was possibly the exposure of free carboxyl groups (-COOH) to alanine residues within PG’s tetrapeptide side chains during hydrolysis. Furthermore, dicarboxylic amino acids (e.g., glutamic acid and aspartic acid) in PG stem peptides retained partially unbound carboxyl groups even after peptide bond formation, which contributed to sustained acidification [21].

3.3. Structure Analysis

Figure 2 shows the characteristic functional groups and chemical bonds of PG from the L. casei ATCC 393. The absorption bands at 3274 cm−1 represented the O–H stretching, 2932 cm−1 and 1061 cm−1 absorption bands represent C–O–C bridging and asymmetric C–H stretching, respectively. These two absorption bands suggested the presence of polysaccharide residues. C=O stretching vibration of amide I was observed at 1624 cm−1 and amide II bands combining N–H bending and C–N stretching vibrations was observed at 1528 cm−1. Additional spectral features included variable C–H deformations (1460–1200 cm−1) and a characteristic β-D-glucopyranose absorption band (905–876 cm−1) [19,29,30,31,32]. Notably, the absorption peak near 1070 cm−1, which was commonly observed in LAB-derived PG, corresponds to the characteristic sugar chain linkages (β-1,4 bonds) that are critical for the PG’s structure [33].

Congo red is an acidic dye that is soluble in water and alcohol. It can form complexes with polysaccharides that exhibit a triple-helical chain conformation, which is essential for the biological activity of polysaccharides. The maximum absorption wavelength of these complexes exhibited a red shift compared to that of Congo red itself. Within a certain concentration range, this characteristic change in maximum absorption wavelength manifested as a violet–red hue. When the concentration of NaOH exceeds a specific value, the maximum absorption wavelength experiences a sharp decline [34]. As shown in Figure 2, the Congo red solution containing PG demonstrated no significant red shifts in maximum absorbance wavelength compared to the control, indicating that only a small amount of triple-helical or single-helical structures existed in the PG component. Given that polysaccharides typically exist in three conformational states (random coils, single helices, or triple helices) in solution, this observation suggested that PG predominantly existed in a random coil conformation in solution. At the 0.25 mol/L NaOH concentration, the wavelength of the PG–Congo red solution initially decreased but subsequently increased. At the 0.3 mol/L NaOH concentration, a sudden decline in maximum absorbance occurred. This may be attributed to the disintegration of the small amount of triple-helical or single-helical structures within the PG component, resulting in it being unable to combine with the Congo red solution and thereby causing a sudden decline in the maximum absorbance value. Notably, triple-helical polysaccharides generally exhibit enhanced biological activities. The predominant random coil conformation of PG suggested that its spatial structure minimally impacts bioactivity.

3.4. Antioxidant Activity

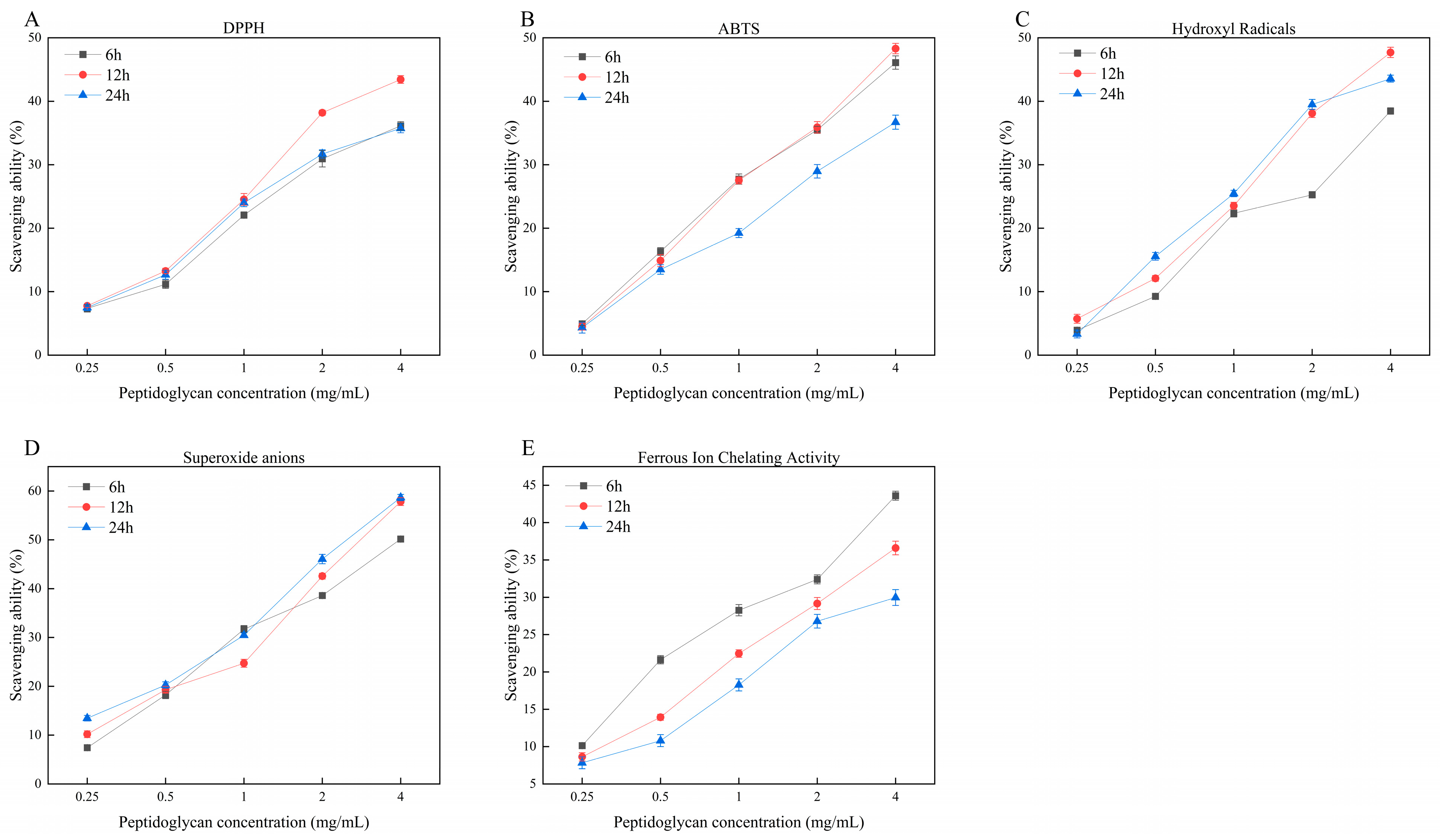

DPPH radicals can be reduced by accepting electrons or hydrogen atoms, serving as a standard tool for evaluating the free radical-scavenging capacity of antioxidants including polysaccharides. Higher DPPH-scavenging rates indicate greater antioxidant activity [35]. As shown in Figure 3, the DPPH radical-scavenging activity of PG increased with rising peptidoglycan concentrations, a trend consistent with the results reported by Wang [36]. The DPPH-scavenging ability of PG was also influenced by different hydrolysis times; PG hydrolyzed for 12 h exhibited better performance, followed by a gradual decline with extended hydrolysis time. This suggests that excessively long hydrolysis times are not conducive to enhancing peptidoglycan activity.

Figure 3.

Peptidoglycan antioxidant activity. (A) DPPH. (B) ABTS. (C) Hydroxyl radicals. (D) Superoxide aminos. (E) Ferrous ion-chelating activity. Different shapes represent different hydrolysis times for PG (hydrolysis for 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h). The values are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3).

ABTS is also one of the indicators used to evaluate the antioxidant capacity of polysaccharides. PGs hydrolyzed for 6 h and 12 h exhibited comparable ABTS-scavenging capacities (Figure 3), while the 24 h hydrolysate showed the lowest activity, a result similar to the observation by Zhang [21]. This phenomenon may be attributed to the potential correlation between ABTS-scavenging efficacy and the abundance of glycosidic bonds or aglycone moieties. Excessively long hydrolysis led to the hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds, exposing polysaccharide groups to the solution environment and consequently reducing their activity. The differential antioxidant responses of PG toward DPPH and ABTS radicals could be associated with structural variations in the substrate molecules [36,37].

Hydroxyl radicals are important reactive oxygen species commonly found in biological systems, which can easily penetrate cell membranes and react with certain biological macromolecules, leading to cellular damage or even death [35]. Therefore, the elimination of hydroxyl radicals is of significant importance for organismal integrity. As shown in Figure 3, PG hydrolyzed for 6 h exhibited limited hydroxyl radical-scavenging capacity, whereas moderate extension of hydrolysis time could enhance the ability to scavenge hydroxyl radicals, indicating that a moderate increase in hydrolysis time could improve the antioxidant capacity of PG. Furthermore, radical-scavenging efficacy increased with the concentration of PG. When the concentration was increased to 4 mg/mL, the increase in the antioxidant activity of polysaccharides after 24 h of hydrolysis slowed down.

Superoxide anions normally exist in biological systems at controlled levels, but when combined with hydroxyl radicals, they generate harmful substances that induce oxidative damage to tissues. Therefore, eliminating excess superoxide anions remains of crucial importance. As illustrated in Figure 3, the superoxide anion-scavenging capacity of PG progressively increased with increasing concentration. PGs hydrolyzed for 24 h exhibited slightly higher activity than those hydrolyzed for 12 h, suggesting that a moderate extension of hydrolysis time could enhance the antioxidant properties of PG.

The ferrous ion-chelating activity of a substance can also reflect its antioxidant potential. In polysaccharides, this chelating ability may be associated with cross-linking bridges between carboxyl groups in uronic acid moieties [38]. As shown in Figure 3, the ferrous ion-chelating ability of PG gradually enhanced with increasing concentrations, demonstrating a positive correlation. PG hydrolyzed for 6 h exhibited the strongest chelating activity, but prolonged hydrolysis times resulted in a gradual reduction in this capacity. This reduction might result from the degradation of macromolecular fragments containing abundant metal-chelating functional groups. As the hydrolysis degree increased, these relevant groups decreased, thereby reducing the metal ion-chelating capacity of PG [21].

Antioxidant activity was closely associated with the structural characteristics of polysaccharides. After hydrolysis, the molecular weights of polysaccharides decreased while their solubility moderately increased, accompanied by the enhanced dissolution of antioxidant-active components. As hydrolysis proceeded, the cleavage of glycosidic bonds led to increased exposure of electron-donating groups including hydroxyl (-OH), carboxyl (-COOH), and amide (-CONH2) groups. This structural modification enabled unstable free radicals to capture more electrons, thereby facilitating their conversion into stable products and consequently enhancing the antioxidant capacity of hydrolyzed PG. However, excessive hydrolysis was observed to negatively impact polysaccharide antioxidant activity. In summary, our research revealed that the 12 h hydrolyzed polysaccharides exhibited optimal antioxidant performance.

3.5. Evaluation of Inflammatory Indicators

To further explore the health-promoting potential of peptidoglycan on intestinal environments, we evaluated colitis damage induced by DSS administration and the capacity of PG to alleviate colitis damage induced by the DSS solution, and examined its protective potential in mitigating inflammatory responses.

Figure 4 displays indicators reflecting colitis severity, including body weight and colon length. During the feeding period, the DSS-induced MOD group mice exhibited symptoms such as weight loss, diarrhea, and colon shortening, which were consistent with colitis pathogenesis. Disease activity index (DAI) scores were evaluated for the different treatment groups during the second DSS induction phase. Mice in the DSS-treated MOD group developed symptoms like soft stools, diarrhea, and hematochezia. As shown in Figure 4B, the MOD group demonstrated a progressive increase in DAI scores, significantly higher than those of the CON and T-MOD groups. No significant differences were observed in body weight or colon length between the CON and T-CON groups, indicating that PG intervention in non-DSS-induced mice did not cause measurable colonic alterations, and thus PG alone does not disrupt immune homeostasis in healthy mice. Compared to the CON group, the MOD group showed decreased body weight after a feeding period but exhibited varying degrees of weight recovery by day 35, following 100 mg/kg PG intervention. Colon length was significantly shortened in the MOD group compared with the CON group, while the T-CON group showed no significant differences compared with the CON group. These data confirmed the successful establishment of the DSS-induced murine colitis model and the inhibitory effects of PG on DSS-induced weight loss and colon shortening in mice.

Figure 4.

Peptidoglycan attenuated DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice. (A) Experimental design. (B) Disease activity index scores across experimental groups. (C) Changes in body weight of mice. (D) Colon picture of group. (E) Length of colons. The values are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 10). Statistics: * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, and *** p ≤ 0.001.

As previously reported, colon length serves as a reliable indicator of IBD severity, with colon shortening representing a hallmark symptom of colonic inflammation that can recover with disease remission [39]. The DSS-induced MOD group exhibited significantly shorter colon lengths compared to the CON group, consistent with findings reported by Cao [22] that DSS can induce clinical manifestations including weight loss and colon shortening in murine models. Notably, after PG intervention, mice in the T-MOD group demonstrated a protective effect against DSS-induced colon length changes than the MOD group. These results demonstrate that PG can effectively mitigate DSS-induced colitis to a certain extent.

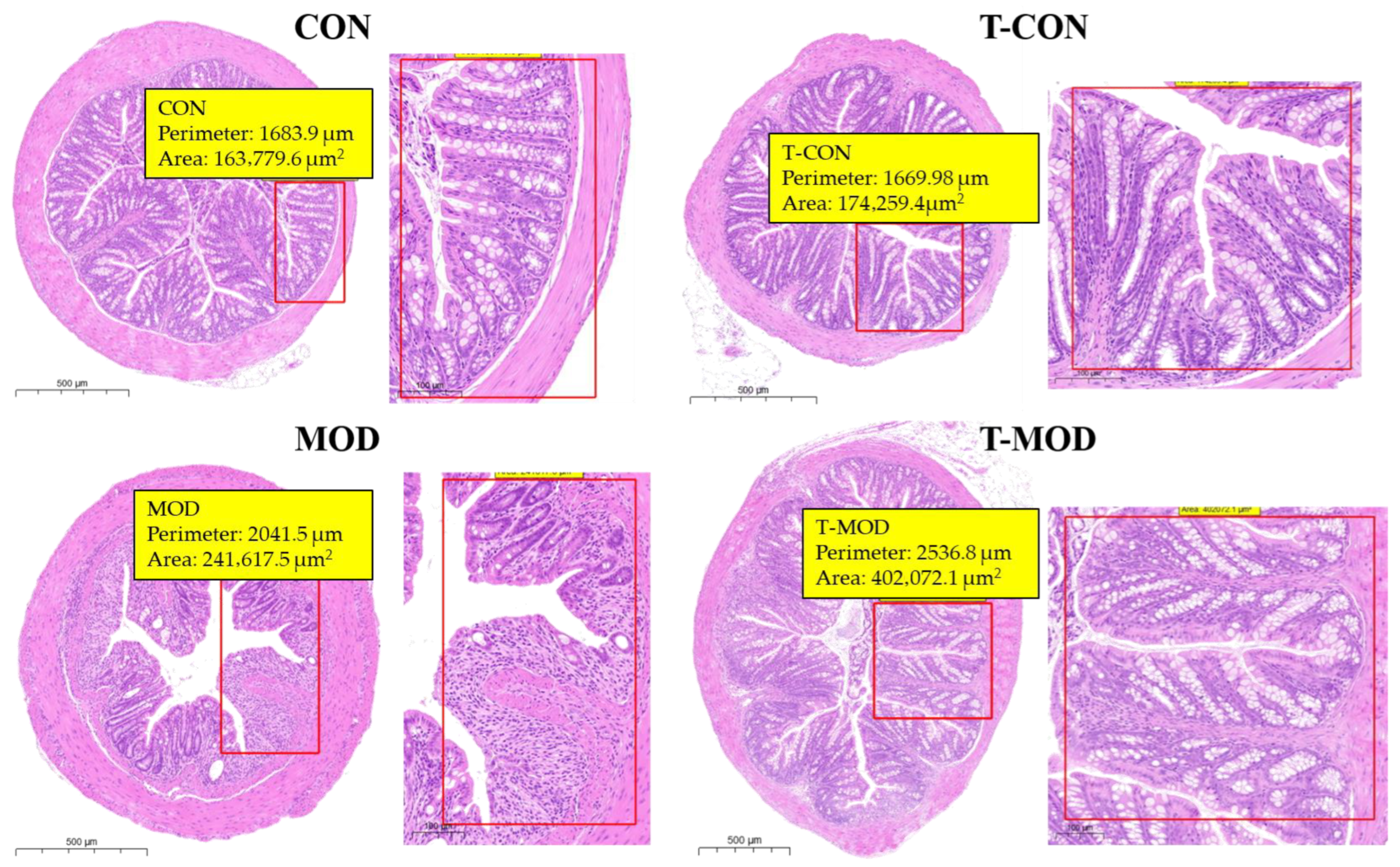

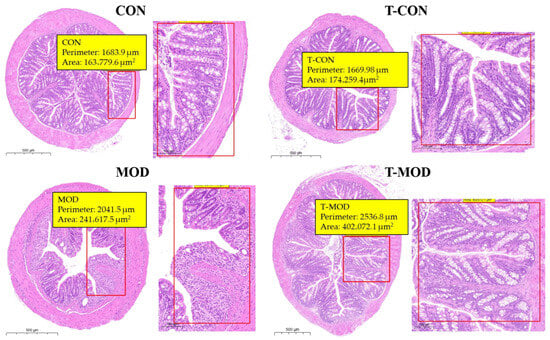

3.5.1. H&E Staining

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining remains the gold standard technique for histopathological assessment of cellular damage. Goblet cells perform a critical role in secreting intestinal mucin, which was of great importance in preserving the structural integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier [40]. In experimental colitis models, characteristic histopathological hallmarks include a disrupted crypt architecture, immune cell infiltration (primarily neutrophils and lymphocytes), epithelial denudation, and goblet cell depletion. These symptoms have been established as reliable indicators of disease progression [41]. According to Figure 5, the histological examination of colonic tissues from the control (CON) group analysis revealed preserved epithelial integrity with ordered enterocyte arrangement, minimal inflammatory infiltration, and intact crypt formations, indicating the absence of pathological alterations. Compared to the CON group, the DSS-induced colitis model (MOD group) exhibited significant mucosal damage characterized by crypt atrophy, submucosal edema, and extensive polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration. Notably, PG intervention (T-MOD group) significantly improved these pathological features, with evidence of crypt morphology restoration. These observations indicate the protective efficacy of PG against DSS-induced colonic damage.

Figure 5.

Representative H&E-stained colon sections (scale bar: 500 μm).

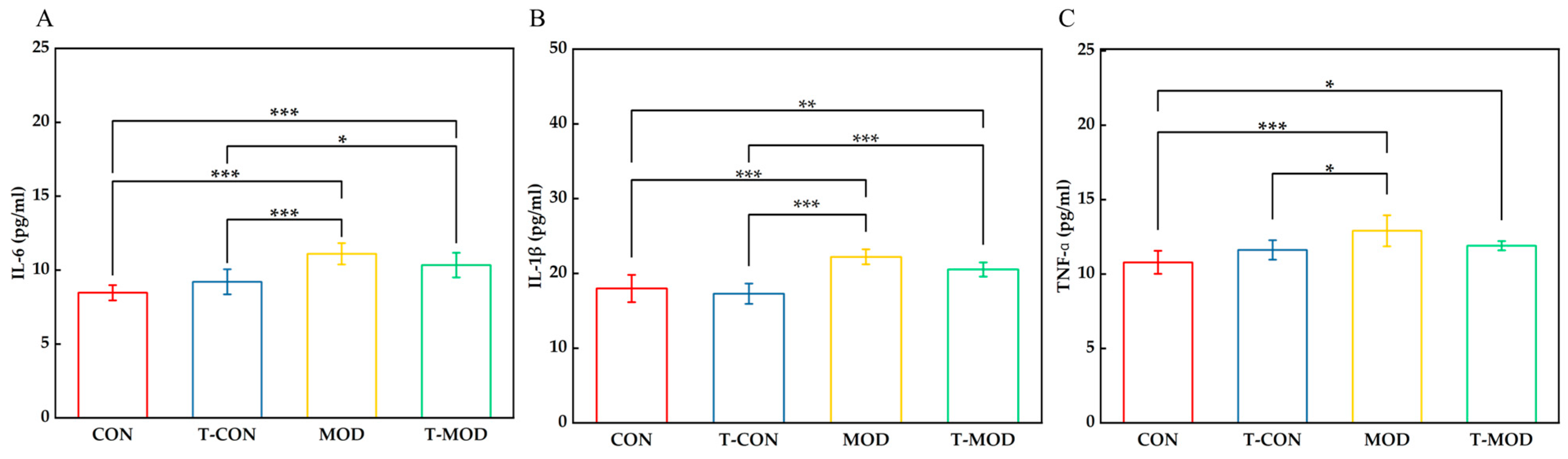

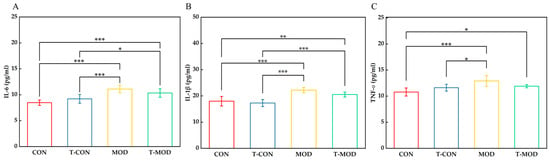

3.5.2. Changes in Inflammatory Cytokines

Inflammatory bowel disease has been associated with the upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [22]. These cytokines, produced during active inflammation, emerge in the early stages of immune response and may initially serve protective functions against tissue damage. DSS-induced colitis can promote the excessive release of inflammatory cytokines, which subsequently stimulates inflammatory reactivity. Pathogenic microbes infiltrating the colon through a compromised intestinal barrier activate antigen-presenting cells (APCs), including dendritic cells and macrophages. Macrophages, through phagocytic activity, release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, thereby initiating and amplifying the inflammatory response [42]. To evaluate the prebiotic potential of PG in mitigating colitis severity, we quantified serum concentrations of these pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α) following PG intervention. As shown in Figure 6, the MOD group showed significantly elevated cytokine levels compared to the CON group, which potentially reflects DSS-induced inflammatory responses and underlying immune dysregulation. Compared with the MOD group, the T-MOD group substantially reversed these increases, reducing IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α levels by approximately 7.0%, 7.6%, and 7.8%, respectively, relative to the MOD group. After PG intervention (T-MOD group), serum pro-inflammatory cytokine levels decreased, indicating that PG modulates cytokine expression to mitigate colitis. These quantitative reductions align with established mechanisms, wherein Lactobacillus-derived peptidoglycan modulates macrophage activity and suppresses NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-B) signaling. These findings are consistent with those from Wu [32], confirming PG’s role in promoting anti-inflammatory mediator secretion while suppressing pro-inflammatory pathways. The robust effect sizes observed underscore PG’s potent immunomodulatory capacity in colitis mitigation.

Figure 6.

Serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α measured by ELISA. (A) IL-6. (B) IL-1β. (C) TNF-α. The values are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 7). Statistics: Some mice showed hemolysis during sampling and the samples were not taken. * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, and *** p ≤ 0.001.

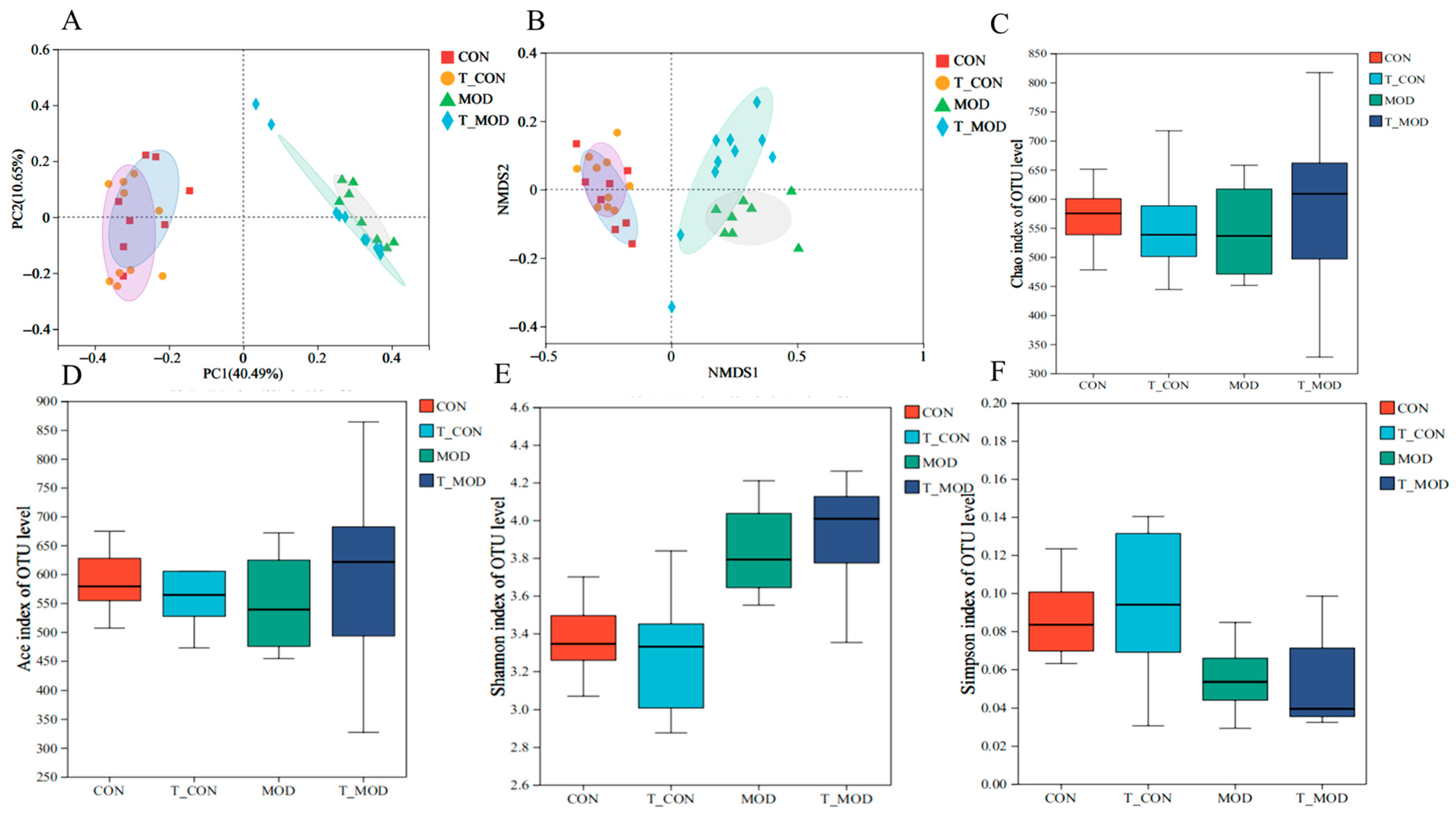

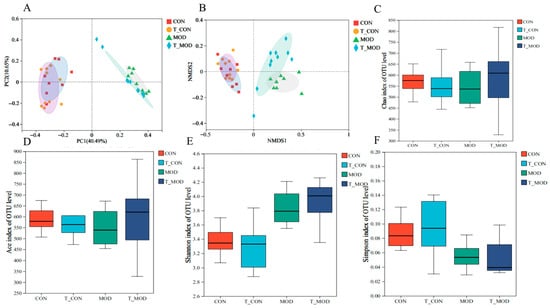

3.5.3. Effect of Peptidoglycan on Mice Gut Microbiota

16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed on fecal samples from the CON, T-CON, MOD, and T-MOD groups. The detected gut microbiota were classified into 12 phyla, 19 classes, 49 orders, 82 families, 182 genera, 341 species, and 2269 operational taxonomic units (OTUs). Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) revealed structural differences in microbial communities among the CON groups, T-CON groups, MOD groups, and T-MOD groups. As shown in Figure 7, DSS-induced colitis increased microbial diversity, potentially due to disrupted intestinal barriers promoting the growth of pathogenic bacteria [43]. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) and non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) of β-diversity at the OTU level (Figure 7A,B) revealed substantial overlap in microbial composition between the CON and T-CON groups, whereas the MOD and T-MOD groups exhibited distinct clustering patterns. This indicated that PG intervention had negligible effects on healthy mice but modulated gut microbial growth in colitis-induced mice to alleviate inflammation. The α-diversity of gut microbiota in colitis mice was evaluated using the Chao1, ACE, Shannon, and Simpson indices. The former two indices quantify microbial richness while the latter two assess diversity. As presented in Figure 7, the T-MOD group exhibited slightly higher Chao1 and ACE indices, reflecting enhanced microbial richness. The change in α-diversity observed in the MOD group was probably caused by DSS-induced inflammation, which promoted the proliferation of harmful gut bacteria, disrupted the balance of gut microbiota, and consequently reduced microbiota abundance. A high Shannon index and reduced Simpson index suggested that while colitis decreased microbial diversity, PG intervention effectively attenuated this reduction, maintaining gut microbial stability.

Figure 7.

Effects of peptidoglycan on the diversity of gut microbiota in mice. (A) PCoA analysis of the β diversity at the OTU level. (B) NMDS analysis of the β diversity at the OTU level. (C) Alpha diversity Chao index. (D) Alpha diversity ACE index. (E) Alpha diversity Shannon index. (F) Alpha diversity Simpson index. The values are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 10).

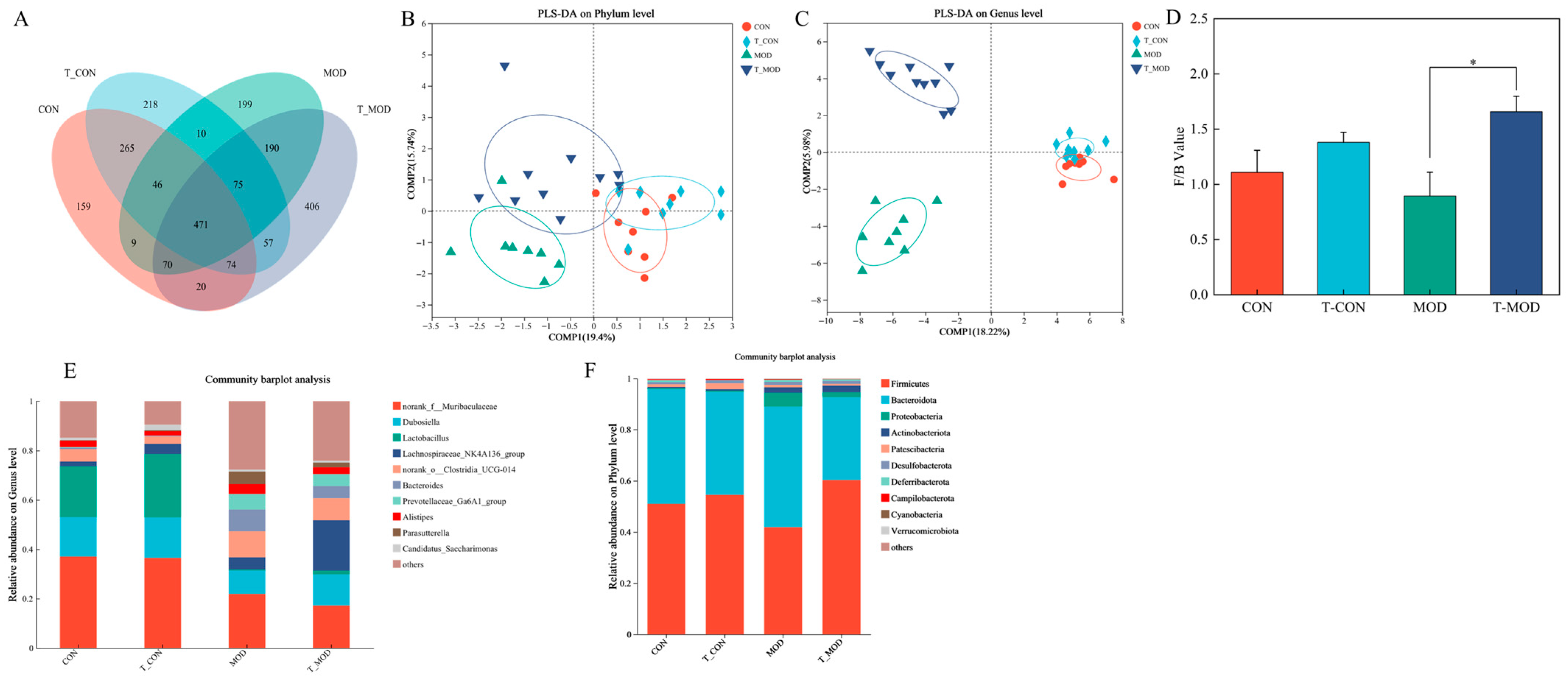

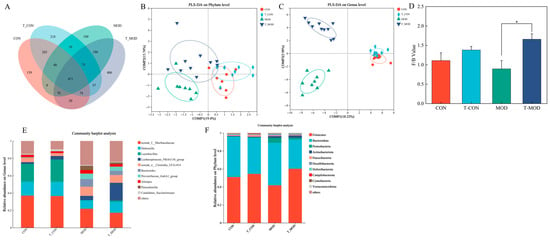

Venn diagrams (Figure 8A) revealed unique and shared microbial species among the CON, MOD, and T-MOD groups, with the T-MOD group exhibiting the highest number of unique microbial species. This suggests that PG intervention modulates intestinal microbial metabolism in mice. To further investigate key microbial community shifts, fecal microbiota were analyzed using linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe). Figure S1 in the Supplementary Materials displays LEfSe classification plots with corresponding LDA scores. The LEfSe plots are organized hierarchically from inner to outer rings, representing phylum, class, order, family, and genus levels. LEfSe analysis identified 40 significantly differential OTUs across taxonomic ranks: 9 at the phylum level, 10 at the class level, 23 at the order level, 36 at the family level, and 70 at the genus level, demonstrating distinct microbial community structures between groups.

Figure 8.

Peptidoglycan modulated the gut microbiota dysbiosis in mice induced by DSS. (A) Venn diagram. (B) PLS-DA analysis on the phylum level. (C) PLS-DA analysis on the genus level. (D) The composition abundance on the phylum level. (E) The composition abundance on the genus level. (F) The abundance ratio of the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes (F/B). The values are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 10). Statistics: * p ≤ 0.05.

The ratio of Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes (F/B) is considered a vital indicator for evaluating the health conditions of the gut microbiome. The decreased F/B ratio has been associated with immuno-inflammatory responses in inflammatory bowel disease [44,45]. Firmicutes primarily produce butyrate, which strengthens intestinal barrier integrity by stimulating mucus synthesis and inhibiting pathogen invasion. In contrast, Bacteroidetes predominantly generate acetate, with elevated levels potentially disrupting gut microbial equilibrium and exerting harmful health effects [45]. As shown in Figure 8D, the T-CON group exhibited increased Firmicutes abundance and an elevated F/B ratio compared to the CON group, but no statistical significance was observed between the two groups. DSS-induced colitis reduced Firmicutes abundance, increased Bacteroidetes levels, lowered F/B ratios, but promoted Proteobacteria proliferation in the MOD group [43,45,46,47]. DSS-induced colitis could create an environment that promotes Firmicutes proliferation. Proteobacteria is considered as the characteristic bacteria of inflammatory phenotypes, which can exacerbate microbial dysbiosis and intestinal inflammation [48]. Compared to the MOD group, the ratio of F/B in the T-MOD group was observed to significantly increase, suggesting that PG intervention could promote the growth of Firmicutes over Bacteroidetes. Notably, PG intervention mitigated these alterations, demonstrating its efficacy in restoring microbial homeostasis.

Figure 8D,E present PLS-DA plots at the phylum and genus levels. Analysis revealed that microbial community compositions were comparable across different treatment groups at the phylum level, with no significant intergroup differences detected. At the genus level, however, the CON group and the T-CON group exhibited similar community structures, whereas the MOD and T-MOD groups showed a statistical difference in compositional divergence. These differences in community assembly across all four groups could be attributed to PG, which modulated the composition of the colon microbiome in mice after DSS-induced inflammation, for instance, suppressing the growth of specific pathogenic microbes and enhancing the proliferation of beneficial bacterial. Additionally, we can suggest that PG might improve the negative impacts of DSS on the gut microbiome.

Heatmaps provide a visual tool to analyze gut microbiota abundance variations with significant differences, enabling intuitive recognition of dominant bacterial community distributions across experimental groups. As observed in Figure S2 in the Supplementary Materials, compared to the CON group, the T-CON group exhibited increased abundances of Lactobacillales and Lachnospiraceae at the genus level, which are known to modulate intestinal inflammation, an observation consistent with prior studies [49,50,51]. Conversely, the MOD group showed significant reductions in Lactobacillus, Muribaculaceae, and Lachnospiraceae populations relative to the CON group, aligning with dysbiosis patterns characteristic of IBD [52,53]. Notably, the T-MOD group demonstrated elevated levels of Lachnospirales, Dubosiella, Lactobacillus, and Clostridia. Both Muribaculaceae and Lachnospiraceae have been identified as microbial targets inversely correlated with colitis progression, as they mitigated the protein degradation in small intestinal epithelial cells caused by DSS-induced colitis [43]. Muribaculaceae is correlated with immunomodulatory processes, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine levels and enhancing intestinal barrier integrity [54]. Lachnospiraceae has been well recognized as a producer of SCFAs and an inducer of regulatory T cells. Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group is also an SFCAs-producing bacteria, which is related to butyric acid production [55]. Furthermore, Lachnospiraceae could synthesize secondary bile acids through 7 α-dehydrogenation to repair the mucosal barrier and reduce inflammation [56]. DSS-induced colitis has been shown to decrease Lachnospirales abundance in murine models [43,57].

The abundance of Dubosiella was negatively correlated with intestinal inflammation severity, as it alleviated colitis by enhancing mucosal barrier integrity in murine models [58,59]. Dubosiella could rebalance Treg/Th17 responses and ameliorate mucosal barrier injury by producing short-chain fatty acids, especially propionate and L-Lysine (Lys), which further explained the increase in fecal propionate levels (Figure 9). Furthermore, Dubosiella can also work in synergy with Clostridium to activate the AhR-IDO1-Kyn circuit in mice, generating L-Lys to regulate Treg-mediated immunosuppression and maintain intestinal immunity [60]. Lactobacillus species attenuate colonic inflammation by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines and reinforcing intestinal epithelial barrier function [43,61]. Specifically, Lactobacillus paracasei JY062 and its exopolysaccharides downregulated TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-17, and IL-1β levels, inhibiting TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway activation and restoring intestinal environmental homeostasis [62]. When combined with other probiotics, Lactobacillus further enhanced gut barrier function. For instance, Clostridium butyricum metabolized lactic acid (a byproduct of Lactobacillus) to produce butyrate, which energized colonic mucosa, strengthened barrier integrity, regulated luminal pH, and maintained gut microbial homeostasis [63]. Therefore, elevated Lactobacillus abundance can promote intestinal equilibrium, mitigate inflammation, and inhibit pathogens [64]. Previous studies reported that shifts in Clostridia abundance correlated with altered colitis susceptibility in murine models, with increased Clostridia abundance emerging as another hallmark of colitis linked to gut dysbiosis [2,65]. Butyric acid demonstrated a positive correlation between Bifidobacterium, Clostridium–Bifidobacterium, and Clostridium, which could regulate butyric acid content by inhibiting hepatic mTORC1 via the gut–liver axis, thereby activating the IRS1/AKT pathway to enhance glucose uptake, glycogen synthesis, and insulin sensitivity, ultimately ameliorating SCFAs content, which further explained the increase in fecal butyrate levels (Figure 9) [66]. Clostridia abundance correlates positively with enhanced epithelial barrier integrity, elevated short-chain fatty acid concentrations, regulatory T-cell proliferation, and the improvement in T-cell function, all of these contributing to anti-inflammatory outcomes [67]. The production of diverse antibiotics is a hallmark feature of Actinobacteria. Elevated levels of Actinobacteria in the MOD group may enhance host defense mechanisms and promote resistance to inflammatory challenges. In contrast, the reduced relative abundance of Actinobacteria observed in the T-MOD group indicated a suppressive effect of PG on inflammatory responses. These observations indicated that PG exerted a regulatory influence over gut microbial communities. While DSS disrupted bacterial community architecture, PG demonstrated a capacity to mitigate these alterations, thereby suggesting potential prebiotic functionality.

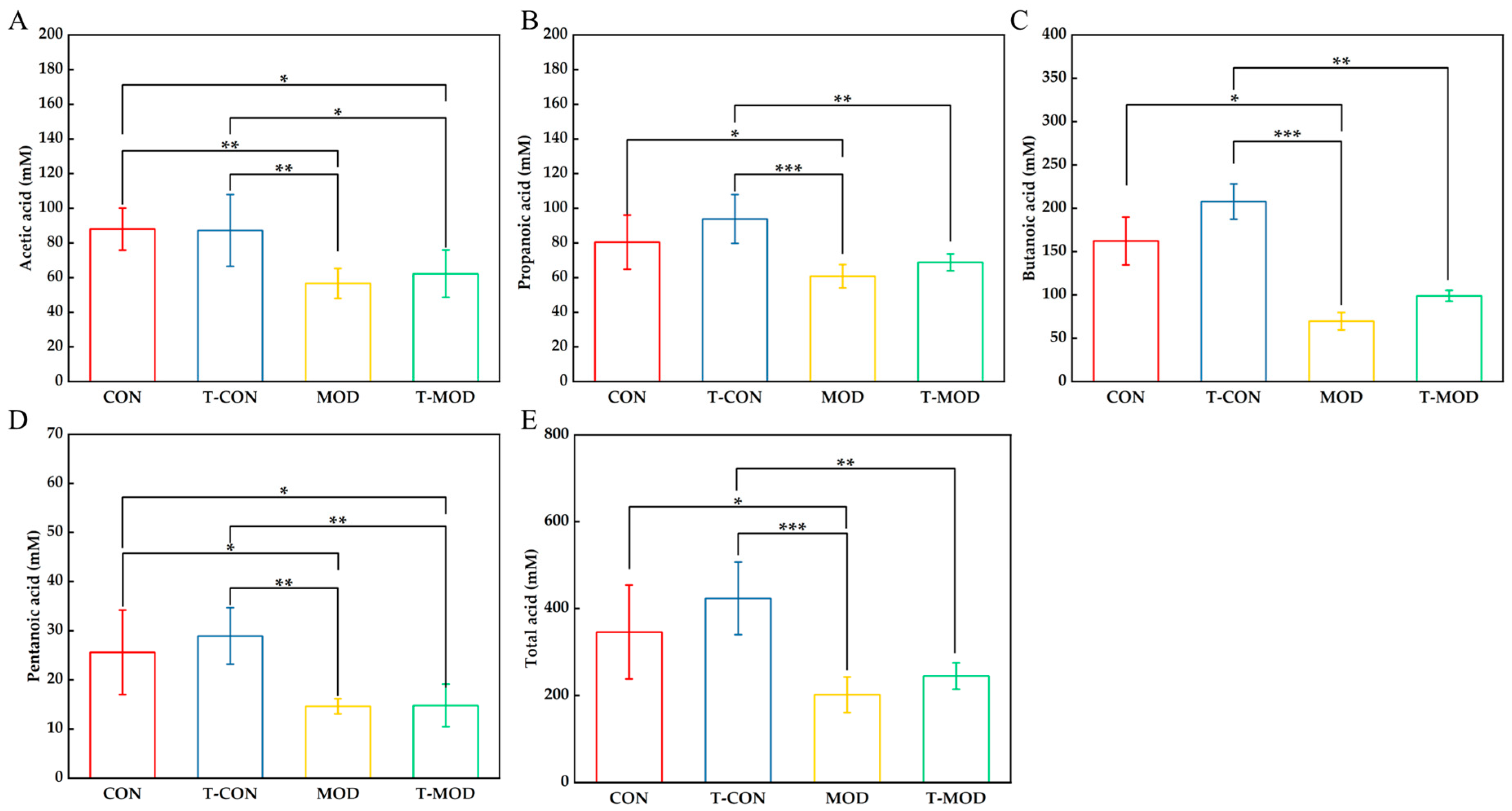

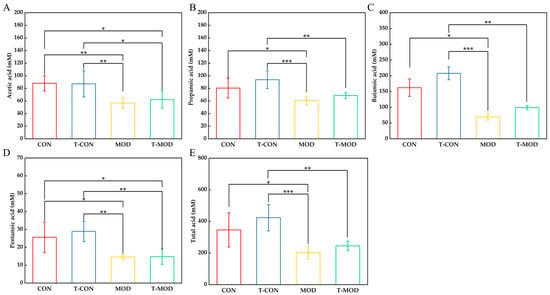

Figure 9.

SCFA. The values are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 6). (A) Acetic acid. (B) Propanoic acid. (C) Butanoic acid. (D) Pentanoic acid. (E) Total acid. Statistics: Some samples were not detected. Statistics: * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, and *** p ≤ 0.001.

These results demonstrated that PG could alleviate intestinal inflammation by enhancing the growth of microbial biomarkers associated with colitis, thereby highlighting its promising capacity as a probiotic replacement for improving colitis inflammation. Notably, significant increases were observed in the abundances of Lachnospirales, Dubosiella, Lactobacillus, and Clostridia in the gut microbiota. PG intervention could effectively attenuate IBD symptoms by promoting the proliferation of beneficial bacteria and suppressing the growth of harmful microbiota. Our research showed that PG could alleviate inflammation by modulating the balance of the gut bacteria environment and improving beneficial metabolites produced by gut bacteria, including SCFAs (short-chain fatty acids).

3.5.4. Effect of Peptidoglycan on SCFAs (Short-Chain Fatty Acids)

SCFAs stimulate the proliferation of intestinal goblet cells while concurrently modulating T lymphocyte differentiation pathways through both direct and indirect mechanistic routes. This dual regulatory capacity underscores their role in maintaining intestinal immune homeostasis. A substantial portion of dietary cellulose in food can be utilized by intestinal microbiota and metabolized into SCFAs, primarily acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid [68,69]. Previous studies demonstrated that SCFAs modulate immune responses via intracellular and extracellular signaling pathways, including G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs). By inhibiting HDAC activity, SCFAs promote regulatory T-cell (Treg) differentiation and suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine expression [39]. Acetate is predominantly produced by Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Clostridium, and Streptococcus. Propionate is produced by Firmicutes, Bacteroides, and Coprococcus. Butyrate is produced by Firmicutes, Eubacterium hirae, and Ruminococcus bromii [69,70]. SCFAs maintain gut microbiota equilibrium by regulating luminal pH and attenuating intestinal inflammation through anti-inflammatory cytokine modulation [71,72]. Additionally, SCFAs exhibit anticancer properties, inducing apoptosis, arresting cell cycles, all of which can contribute to inhibiting intestinal carcinogenesis [73]. Research indicated that propionate can stimulate host metabolite production and anti-inflammatory effects through the activation of the GPR41 and GPR43 signaling pathways [74]. Butyrate selectively regulates histone acetylation of pathogen recognition in receptor-encoding genes to modulate intestinal mucosal immune responses, enhancing epithelial tight junctions, mucus secretion, and barrier function. It also promotes cell apoptosis and inhibits proliferation, while suppressing NF-κB signaling to reduce the expression of inflammatory genes and mitigate colonic inflammation [63,75,76,77]. Pentanoic plays a significant role in host control of body and autoimmune regulation [27].

As shown in Figure 9, the T-CON group exhibited elevated levels of acetate, propionate, butyrate, and pentanoic compared to the CON group, with butyrate showing the highest concentration. This observation correlated with the increased abundances of Lactobacillus and Lachnospiraceae in the T-CON group, suggesting that PG modulates gut microbiota composition to maintain intestinal homeostasis. Compared to the CON group, the MOD group demonstrated reduced levels of all SCFAs, particularly butyrate, which had the largest decline relative to controls (decreased by 57.08%), indicating that DSS-induced colitis had an inhibitory effect on the production of SCFAs. As shown in Figure 9D, DSS induction significantly reduced the content of pentanoic acid in mice. After PG intervention, this phenomenon had alleviated, but there was no significant difference between the T-MOD and MOD groups. As mentioned previously, butyrate is associated with intestinal barrier energy supply. The butyrate content in the MOD group was the lowest, which also suggests that DSS induction disrupts the intestinal barrier. However, PG intervention can improve butyrate content. This metabolic shift is likely mediated by the observed enrichment of butyrogenic bacteria, such as Colidextribacter (Figure 8E), in response to PG intervention. Furthermore, as shown in Figure 9E, compared with the CON group, the total acid content in the T-CON group increased, and compared with the MOD group, the total acid content in the T-MOD group also rebounded, indicating that peptidoglycan could alleviate colitis by regulating the content of SCFAs in mice. The increase in butyrate content indicated that PG could affect the content of metabolites by improving the composition of beneficial intestinal microbiota, thereby alleviating intestinal inflammation.

This result is consistent with the diminished butyrate levels observed in ulcerative colitis (UC) patients due to microbial dysbiosis [4]. According to these findings, we can suggest that PG can alleviate colonic inflammation response by enhancing the production of SCFAs and regulating SCFA-mediated signaling pathways.

However, there is an important limitation to this study. The role and mechanism of peptidoglycan in alleviating colitis have been investigated in this study on DSS-induced models, yet further validation of the effect of PG in subsequent clinical studies is still needed.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully extracted and purified PG from L. casei ATCC 393. Structural analysis revealed that PG forms a three-dimensional network composed of N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) and N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM) linked by β-1,4-glycosidic bonds. In solution, it predominantly adopted a random coil conformation, with less triple- or single-stranded helical structures. PG demonstrated significant antioxidant activity by scavenging free radicals, suggesting its potential as a natural antioxidant. Its antioxidant capacity exhibited concentration-dependent enhancement and hydrolysis time sensitivity; moderate hydrolysis time (e.g., 12 h hydrolysis) and higher PG concentrations improved antioxidant activity, while excessive hydrolysis compromised structural integrity, thereby reducing activity. In the current research, we constructed a colitis model by DSS-induced inflammatory injury in mice to study the preventive effect of PG against inflammation. In the DSS-induced colitis model, PG (100 mg/kg) alleviated weight loss phenomena and decreased the disease activity index (DAI) score in mice. Pro-inflammatory cytokine levels were suppressed, and histological analysis of colonic tissues via (H&E) staining indicated improved epithelial barrier integrity. PG also prevented DSS-induced dysbiosis by maintaining gut microbiota stability and elevated SCFAs, including acetic, propionic, butyric, and pentanoic acids. In conclusion, PG promoted beneficial metabolite production by increasing the abundance and diversity of probiotic bacterial communities, which contributed to mitigating DSS-induced inflammation.

Placing our findings in the context of other prebiotics studied in DSS-induced colitis models helps to contextualize the efficacy of PG. For instance, the common prebiotics for alleviating colitis include inulin and β-glucan. Inulin can alter colitis by inhibiting the TRL4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway—improving the inflammatory response and enhancing the intestinal barrier [78]. However, some findings suggested that inulin may aggravate colitis, potentially through increased luminal osmotic pressure [79]. β-glucan supplementation has a dual effect. It could regulate the mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory markers such as IL-6, IL-17, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1β in the colon, increase the expression of serum anti-inflammatory factor IL-10, and also stimulate the increase in transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) expression [80]. However, a previous study has shown that the intestinal microbiota diversity of mice with DSS-induced colitis intervened by glucan did not increase significantly. This might be due to the fact that the oral glucan portion was utilized before reaching the intestine [81]. In contrast, PG not only has the ability to regulate intestinal microbiota but also has a unique function of protecting the integrity of the intestinal barrier and regulating the function of short-chain fatty acids in the body, which may be achieved through its direct interaction with pattern recognition receptors on host immune cells.

These findings highlight the potential of PG in modulating gut microbiota, enhancing antioxidant defenses, and protecting intestinal barriers, supporting its application as a functional food ingredient. However, this study has certain limitations. The murine models might inadequately reflect the complex dynamics of human intestinal microbiota and immunological interactions. Further studies should explore the molecular pathways governing PG probiotic mechanisms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr13123978/s1, Figure S1: LEfSe; Figure S2: heatmap; Table S1: p-values and confidence intervals for major comparisons; Table S2: Summary table of antioxidant capacities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, and writing—original draft preparation, R.L. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, M.X., X.Y. and Y.H.; supervision, W.H.; project administration, H.X., R.L. and J.S. contributed equally to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Tianjin Key Research and Development Plan, grant number 19YFZCSN00100.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviation is used in this manuscript:

| PG | Peptidoglycan |

References

- Zulfiqar, F.; Hozo, I.; Rangarajan, S.; Mariuzza, R.A.; Dziarski, R.; Gupta, D. Genetic Association of Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein Variants with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziarski, R.; Park, S.Y.; Kashyap, D.R.; Dowd, S.E.; Gupta, D. Pglyrp-Regulated Gut Microflora Prevotella falsenii, Parabacteroides distasonis and Bacteroides eggerthii Enhance and Alistipes finegoldii Attenuates Colitis in Mice. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coates, M.D.; Binion, D.G. Silent Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Crohns Colitis 360 2021, 3, otab059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, R.; Lo, B.C.; Núñez, G. Host–microbiota interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, E.M.; Valenti, V.; Rockel, C.; Hermann, C.; Pot, B.; Boneca, I.G.; Grangette, C. Anti-inflammatory capacity of selected lactobacilli in experimental colitis is driven by NOD2-mediated recognition of a specific peptidoglycan-derived muropeptide. Gut 2011, 60, 1050–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Araby, A.M.; Fisher, J.F.; Mobashery, S. Bacterial peptidoglycan as a living polymer. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2025, 84, 102562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapot-Chartier, M.P.; Kulakauskas, S. Cell wall structure and function in lactic acid bacteria. Microb. Cell Fact. 2014, 13, S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmann, R.; Lajunen, H.M.; Erbs, G.; Newman, M.A.; Kolb, D.; Tsuda, K.; Katagiri, F.; Fliegmann, J.; Bono, J.J.; Cullimore, J.V.; et al. Arabidopsis lysin-motif proteins LYM1 LYM3 CERK1 mediate bacterial peptidoglycan sensing and immunity to bacterial infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 19824–19829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Q.; Wu, L.L.; Liu, J.W.; Chen, K.X.; Li, Y.M. Iridoids and derivatives from Catalpa ovata with their antioxidant activities. Fitoterapia 2023, 169, 105599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Yi, Z.K.; Xu, M.; Han, Y. A Review on the Extraction, Structural Characterization, Function, and Applications of Peptidoglycan. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2025, 46, e2400654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.M. Immunomodulatory mechanisms of lactobacilli. Microb. Cell Fact. 2011, 10, S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Li, F.; Zhang, M.; Xia, Y.; Ai, L.; Wang, G. Effect of D-Ala-Ended Peptidoglycan Precursors on the Immune Regulation of Lactobacillus plantarum Strains. Front. Immunol. 2022, 12, 825825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, M.G.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, G.B. Lactobacillus plantarum CAU1055 ameliorates inflammation in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW264.7 cells and a dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis animal model. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 6718–6725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, T.; Osorio, A.; David Ginez, L.; Camarena, L.; Poggio, S. Bacterial cell wall quantification by a modified low-volume Nelson-Somogyi method and its use with different sugars. Can. J. Microbiol. 2022, 68, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbara, M.T.; Philpott, D.J. Peptidoglycan: A critical activator of the mammalian immune system during infection and homeostasis. Immunol. Rev. 2011, 243, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarchum, I.; Pamer, E.G. Regulation of innate and adaptive immunity by the commensal microbiota. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2011, 23, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.J. Peptidoglycan-induced modulation of metabolic and inflammatory responses. Immunometabolism 2023, 5, e00024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuochi, V.; Spampinato, M.; Distefano, A.; Palmigiano, A.; Garozzo, D.; Zagni, C.; Rescifina, A.; Volti, G.L.; Furneri, P.M. Soluble peptidoglycan fragments produced by Limosilactobacillus fermentum with antiproliferative activity are suitable for potential therapeutic development: A preliminary report. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1082526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde, S.; Chodisetti, P.K.; Reddy, M. Peptidoglycan: Structure, Synthesis, and Regulation. EcoSal Plus 2021, 9, eESP-0010-2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Shi, Y.H.; Le, G.W.; Ma, X.Y. Distinct immune response induced by peptidoglycan derived from Lactobacillus sp. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 11, 6330–6337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Functional Properties of Lactic Acid Bacteria Peptidoglycan andits Effect on the Quality of Fresh-Cut Apples. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Agricultural University, Taian, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhang, L.; Qin, N.; Zhu, B.; Xia, X. Jellyfish skin polysaccharides enhance intestinal barrier function and modulate the gut microbiota in mice with DSS-induced colitis. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 10121–10135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyder, A. PG1yRP3 concerts with PPARγ to attenuate DSS-induced colitis in mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 67, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S. Study About the Preventive and Therapeutic Effects of Fucoidan onDSS-Induced Acute Ulcerative Colitis in C57BL/6 Male Mice. Master’s Thesis, Soochow University, Suzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Gong, L.; Jin, Y.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P.; Zhao, J.; Yang, B.; Chen, W. Different Effects of Different Lactobacillus acidophilus Strains on DSS-Induced Colitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-L.; Chen, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-T.; Wu, W.-K.; Chang, L.-C.; Lai, C.-H.; Wu, M.-S.; Kuo, C.-H. Evaluation and Optimization of Sample Handling Methods for Quantification of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Human Fecal Samples by GC–MS. J. Proteome Res. 2019, 18, 1948–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Pan, L.; Wang, B.; Zou, X.; Zhang, A.; Zhou, Z.; Han, Y. Simulated Digestion and Fecal Fermentation Behaviors of Levan and Its Impacts on the Gut Microbiota. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 1531–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, A.; Brown, R.R.; Anderle, S.K.; Chetty, C.; Cromartie, W.J.; Gooder, H.; Schwab, J.H. Arthropathic properties related to the molecular weight of peptidoglycan-polysaccharide polymers of streptococcal cell walls. Infect. Immun. 1982, 35, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, D.D.; Guo, Y.X.; Zeng, X.Q. Structure and anti-inflammatory capacity of peptidoglycan from Lactobacillus acidophilus in RAW-264.7 cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 96, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacuráková, M.; Wilson, R.H. Developments in mid-infrared FT-IR spectroscopy of selected carbohydrates. Carbohydr. Polym. 2001, 44, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talari, A.C.S.; Martinez, M.A.G.; Movasaghi, Z.; Rehman, S.; Rehman, I.U. Advances in Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy of biological tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2017, 52, 456–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, D.D.; Zeng, X.Q.; Sun, Y.Y.; Cao, J.X. Phosphorylation of peptidoglycan from Lactobacillus acidophilus and its immunoregulatory function. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, D.D.; Guo, Y.X.; Sun, Y.Y.; Zeng, X.Q. Peptidoglycan diversity and anti-inflammatory capacity in Lactobacillus strains. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 128, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.Z. Exatration, Structual Analysis and Bioactivity of Peptidoglycan from L. paracasei subp. Paracaseix 12. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhixiang, Y.; Haicheng, Y.; Jinrong, W. Structural characterization and antioxidant activity in vitro of selenized Bacillus subtilis peptidoglycan. J. Henan Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 44, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. Preparation, Structual Characterization and Function of Peptidoglycan from Lactic Acid Bacteria. Master’s thesis, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Azzouny, R.A.; Wang, R.; Yoo, S.H. Purification and Characterization of a 6.5 kDa Antioxidant Peptidoglycan Purified from Silk Worm (Bombyx mori) Pupae Extract. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2011, 20, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.P.; Li, J.W.; Deng, K.Q.; Ai, L.Z. Effects of drying methods on the antioxidant activities of polysaccharides extracted from Ganoderma lucidum. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 1849–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, H.; Kan, J.; Gou, Y.R.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X.N.; Tang, S.X.; Sun, R.; Qian, C.L.; et al. Anti-inflammatory properties and gut microbiota modulation of an alkali-soluble polysaccharide from purple sweet potato in DSS-induced colitis mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 153, 708–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Li, X.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Zhu, B.Y.; You, L.J.; Hileuskaya, K. Polysaccharides from Sargassum fusiforme after UV/H2O2 degradation effectively ameliorate dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 11747–11759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Zulfiqar, F.; Park, S.Y.; Núñez, G.; Dziarski, R.; Gupta, D. Peptidoglycan Recognition Protein 3 and Nod2 Synergistically Protect Mice from Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 3055–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Sharma, N.; Kakkar, D. Natural polysaccharides for ulcerative colitis: A general overview. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2023, 13, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, Z.; Cheng, L.; Kang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, M.; Liu, H.; Zhu, Q.; Guo, Q.; et al. Structural Characterization of Water-Soluble Pectin from the Fruit of Diospyros lotus L. and Its Protective Effects against DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 1630–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.B.; Elzallat, M.; Mohammed, D.M.; Hammam, O.A.; Abdel-Wareth, M.T.A.; Hassan, M. Helix pomatia mucin alleviates DSS-induced colitis in mice: Unraveling the cross talk between microbiota and intestinal chemokine. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.Y.; Wang, L.J.; Tang, L.; Wang, L.; Cao, S.Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L. Salvianolic acid B alters the gut microbiota and mitigates colitis severity and associated inflammation. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 46, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.M.; Chen, Y.J.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, K.K.; Huang, L.X.; Ke, X.Q.; Peng, L.; Guo, Z.G. Protective effects and mechanisms of extracts of Gleditsia sinensis Lam. Thorn on DSS-induced colitis in mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 340, 119244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.M.; Zhu, M.H.; Wang, N.; Zhang, F.Y.; Liu, T.J. Photodynamic therapy with a novel photosensitizer inhibits DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in rats via the NF-κB signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 15, 1539363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.L.; Sun, Q.; Wang, Y.W.; Han, D.Q.; Fan, J.H.; Zhang, J.L.; Yang, C.H.; Ma, X.X.; Sun, Q.S. The regulatory effects of L-plantarum peptidoglycan microspheres on innate and humoral immunity in mouse. J. Microencapsul. 2017, 34, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryaznova, M.; Burakova, I.; Smirnova, Y.; Morozova, P.; Chirkin, E.; Gureev, A.; Mikhaylov, E.; Korneeva, O.; Syromyatnikov, M. Effect of Probiotic Bacteria on the Gut Microbiome of Mice with Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammation. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.C.; Peng, H.H.; Sun, Y.N.; Yang, J.L.; Wang, J.; Bai, F.Q.; Peng, C.Y.; Fang, S.Z.; Cai, H.M.; Chen, G.J. Yeast β-glucan attenuates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis: Involvement of gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 135846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-H.; Chen, C.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, Z.-J.; Zhou, M.-Q.; Liu, X.-Y.; Miyashita, K.; Duan, D.-L.; Du, L. Fucoxanthin Alleviates Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced Colitis and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 4142–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Liu, H.; Yu, H.; Chen, M.; Yang, T.; Zeng, X.; Qiao, S. Core Altered Microorganisms in Colitis Mouse Model: A Comprehensive Time-Point and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Analysis. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, J.Y.; Choi, K.; Lee, J.H.; Oh, N.S. Protective Potential of Limosilactobacillus fermentum Strains and Their Mixture on Inflammatory Bowel Disease via Regulating Gut Microbiota in Mice. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 35, e2410009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wang, L.; Liu, M.; Wu, X.; Lu, Q.; Liu, R. The underlying mechanism of A-type procyanidins from peanut skin on DSS-induced ulcerative colitis mice by regulating gut microbiota and metabolism. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.-W.; Xie, Y.; Huang, Z.-C.; Yang, K.; Wang, Z.-G.; Hu, H.-L. Study of the therapeutic effect of raw and processed Vladimiriae Radix on ulcerative colitis based on intestinal flora, metabolomics and tissue distribution analysis. Phytomedicine 2021, 85, 153538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Hu, G.Q.; Fu, S.P.; Qin, D.; Song, Z.Y. Phillyrin ameliorates DSS-induced colitis in mice via modulating the gut microbiota and inhibiting the NF-κB/MLCK pathway. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0200624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, Z.; Sun, R.; Liu, X.; Luo, J.; Chen, X.; Zheng, J.; Liu, R. Improvement in DSS induced acute enteritis in mice with supplementation of bifidobacteria. Acta Aliment. 2025, 54, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Lv, Y.J.; Quan, M.; Ma, M.F.; Shang, Q.S.; Yu, G.L. Bacteroides salyersiae Is a Candidate Probiotic Species with Potential Anti-Colitis Properties in the Human Colon: First Evidence from an In Vivo Mouse Model. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tu, S.; Ji, X.; Wu, J.; Meng, J.; Gao, J.; Shao, X.; Shi, S.; Wang, G.; Qiu, J.; et al. Dubosiella newyorkensis modulates immune tolerance in colitis via the L-lysine-activated AhR-IDO1-Kyn pathway. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.Q.; Yu, Z.F.; Luo, L.; Li, S.; Guan, X.; Sun, Z.L. Modulation of Inflammation Levels and the Gut Microbiota in Mice with DSS-Induced Colitis by a Balanced Vegetable Protein Diet. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2025, 80, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Cui, Z.Y.; Chen, C.; Yang, X.Y.; Jiang, Y.J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Man, C.X. Lactobacillus paracasei JY062 with its exopolysaccharide ameliorates intestinal inflammation on DSS-induced experimental colitis through TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway. Food Biosci. 2025, 63, 105689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, J.Z.; Xie, A.W.; Yang, H.Q.; Li, Y.J.; Mei, Y.X.; Li, J.S.; Xiao, L.; Liu, Y.Y.; Liang, Y.X. Enhancing butyrate synthesis and intestinal epithelial energy supply through mixed probiotic intervention in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. Food Biosci. 2025, 63, 105727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Maimaitiming, M.; Yang, J.C.; Xia, S.L.; Li, X.; Wang, P.Y.; Liu, Z.Q.; Wang, C.Y. Quinazolinone Derivative MR2938 Protects DSS-Induced Barrier Dysfunction in Mice Through Regulating Gut Microbiota. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Håkansson, Å.; Tormo-Badia, N.; Baridi, A.; Xu, J.; Molin, G.; Hagslätt, M.L.; Karlsson, C.; Jeppsson, B.; Cilio, C.M.; Ahrné, S. Immunological alteration and changes of gut microbiota after dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) administration in mice. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 15, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Xiong, H.; Cai, Y.; Chen, W.; Shi, M.; Liu, L.; Wu, K.; Deng, X.; Deng, X.; Chen, T. Clostridium butyricum ameliorates post-gastrectomy insulin resistance by regulating the mTORC1 signaling pathway through the gut-liver axis. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 297, 128154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, T.J.; Tchaptchet, S.Y.; Arsene, D.; Mishima, Y.; Liu, B.; Sartor, R.B.; Carroll, I.M.; Miao, E.A.; Fodor, A.A.; Hansen, J.J. Environmental Factors Modify the Severity of Acute DSS Colitis in Caspase-11-Deficient Mice. Inflamm. Bowel. Dis. 2018, 24, 2394–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhou, L.; Ling, S.; Li, Y.; Kong, B.; Huang, P. Dietary fiber intake and risks of proximal and distal colon cancers A meta-analysis. Medicine 2018, 97, e11678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Liang, Y.Q.; Qiao, Y. Messengers From the Gut: Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites on Host Regulation. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 863407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Faden, H.S.; Zhu, L. The Response of the Gut Microbiota to Dietary Changes in the First Two Years of Life. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, H. The Inhibitory Effect of Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolites on Colorectal Cancer. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 1607–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.X.; Zhao, J.X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Zhai, Q.X. Modulation of gut health using probiotics: The role of probiotic effector molecules. J. Future Foods 2022, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, A.; Dash, J.; Kancharla, S.; Kolli, P.; Mahajan, D.; Senapati, S.; Jena, M.K. Probiotics: A Promising Candidate for Management of Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, I.; Inoue, D.; Maeda, T.; Hara, T.; Ichimura, A.; Miyauchi, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Hirasawa, A.; Tsujimoto, G. Short-chain fatty acids and ketones directly regulate sympathetic nervous system via G protein-coupled receptor 41 (GPR41). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 8030–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Taussig, D.P.; Cheng, W.-H.; Johnson, L.K.; Hakkak, R. Butyrate Inhibits Cancerous HCT116 Colon Cell Proliferation but to a Lesser Extent in Noncancerous NCM460 Colon Cells. Nutrients 2017, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Li, M.M.; Xu, H.X.; Wang, W.J.; Yin, Z.P.; Zhang, Q.F. Retrograded starch as colonic delivery carrier of taxifolin for treatment of DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 288, 138602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.H.; Lam, W.; Ma, D.L.; Gullen, E.A.; Cheng, Y.C. Butyrate mediates nucleotide-binding and oligomerisation domain (NOD) 2-dependent mucosal immune responses against peptidoglycan. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 3529–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Li, F.; Lv, X.; Xiao, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, J.; Lu, W.; Chen, W. Unveiling the therapeutic potential and mechanism of inulin in DSS-induced colitis mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 135861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosono, T.; Saito, K.; Arima, Y.; Ozaki-Masuzawa, Y.; Seki, T. Inulin exacerbates disease severity in a mouse model of ulcerative colitis by causing osmotic diarrhea. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2025, 89, 1721–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariaee, A.; Koentgen, S.; Wardill, H.R.; Hold, G.L.; Prestidge, C.A.; Armstrong, H.K.; Joyce, P. Prebiotic selection influencing inflammatory bowel disease treatment outcomes: A review of the preclinical and clinical evidence. eGastroenterology 2024, 2, e100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiengrach, P.; Visitchanakun, P.; Finkelman, M.A.; Chancharoenthana, W.; Leelahavanichkul, A. More Prominent Inflammatory Response to Pachyman than to Whole-Glucan Particle and Oat-β-Glucans in Dextran Sulfate-Induced Mucositis Mice and Mouse Injection through Proinflammatory Macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).