Abstract

Considering the growing global interest in healthy diets and reducing sugar consumption, date paste has emerged as a natural sweetener and valuable raw material in food processing. This study promotes sustainability by evaluating date paste as a sugar substitute in orange jam production. Sugar was replaced at levels of 0, 20, 40, 50, and 80%, and the resulting products were assessed for chemical composition, physicochemical properties, and sensory characteristics. The results showed that substituting sugar with date paste significantly increased ash, protein, carotenoids, and mineral contents (particularly potassium and iron), while reducing moisture and calorie levels. Both total soluble solids and viscosity values increased as the substitution level increased. Sensory evaluation indicated that samples with 20% and 40% date paste replacement achieved the highest acceptance scores, whereas the 80% replacement level resulted in lower preference. Overall, replacing sugar with date paste enhanced the orange jam’s nutritional and physicochemical properties, with optimal sensory quality observed at moderate substitution levels. Therefore, it is recommended to use date paste as a healthy, natural sweetener (at 20–40% substitution levels) to improve nutritional value and support environmental sustainability and the local economy.

Keywords:

nutrition; orange jam; sugar substitute; date paste; sensory evaluation; food; sustainability 1. Introduction

Jam is a gelatinized food product with medium moisture content, produced by cooking fruit or vegetable pulp with sugar, pectin, citric acid, and other additives until the total soluble solids (TSS) reach approximately 68.5–70%. At this concentration, microbial growth is effectively inhibited, ensuring product preservation. Jams are widely consumed and commonly incorporated into bakery products such as bread, biscuits, and pies [1,2]. Sugar plays a central role in jam manufacturing, acting as a preservative by lowering water activity and preventing microbial proliferation. It also interacts with pectin to form a desirable gel structure, contributes to sweetness, enhances the natural fruit flavor, and participates in color development through caramelization. However, excessive consumption of refined sugar is associated with health concerns, including dental caries, obesity, elevated triglycerides, malnutrition, and impaired insulin function [3].

Citric acid is essential for achieving the appropriate acidity required for pectin gelation, facilitating intermolecular bonding and stable gel formation. Pectin, a polysaccharide extracted mainly from citrus peels, functions as a thickening agent, significantly influencing the texture and rheological properties of jam [4]. Oranges, with their high-water content (86–88%) and carbohydrates (8–12%), are including glucose, fructose, and sucrose, serve as an excellent raw material for jam production. They also provide dietary fiber (2–3%) and are a rich source of vitamin C (45–70 mg per 100 g of fresh orange), supplying 70–90% of the recommended daily intake based on 100 g of fresh orange. In addition, oranges contain essential minerals such as potassium (170–200 mg per 100 g) and bioactive compounds, including flavonoids (e.g., hesperidin and naringin) and phenolic acids. The acidity of oranges (pH 3.0–4.0), largely due to citric acid, contributes to their characteristic flavor and preservation [5].

Dates are naturally rich in dietary fiber and essential minerals, including iron, potassium, calcium, and magnesium, while providing significant caloric content. These characteristics make dates a healthy alternative to refined sugars and a functional ingredient with potential benefits for mitigating diet-related health risks. Notably, the potassium content in dates is approximately 2.5 times higher than that found in bananas [3]. In Saudi Arabia, date paste is produced extensively, primarily from surplus or lower-grade dates generated during the processing of premium fruits. Date paste represents a cost-effective intermediate product that can be incorporated into multiple food industries, including bakery and pastry products [6], soft drinks [7], baby foods [8], ice cream [9], jam production [10], fortified pastes [11], and functional foods [12]. Within the framework of national strategies to utilize local agricultural resources and promote sustainable food production, the date sector has become one of the most important industries in Saudi Arabia. Recent reports from the National Center for Palms and Dates and the General Authority for Statistics indicate that Saudi date products were exported to 116 countries in 2023, with total export value exceeding 566 million SAR—a 2.5% increase compared to the first quarter of 2022. Annual production exceeds 1.6 million tons, and the Kingdom ranked first globally in date exports in 2021 [13,14]. Among Saudi cultivars, ‘Khalas’ dates from the Qassim region are particularly valued for their superior flavor, long shelf life, and high antioxidant content. These dates are rich in carbohydrates and fiber, with a composition including 7.1% moisture, 6.0% protein, and 1.8% ash [15,16]. Despite the nutritional and functional benefits of dates, their use as a sugar substitute in jam production remains limited. Incorporating date paste as a natural sweetener could improve the nutritional profile of jams while maintaining acceptable sensory characteristics. Thus, the objective of this research was to produce a nutritionally enhanced and high-quality orange jam by replacing added sugar with different proportions of locally produced date paste as a natural, healthy sweetener.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Khalas date paste was obtained from Kingdom Dates Factory in Buraidah, Al-Qassim region, KSA, during the season August 2024. The raw materials used to manufacture the jam are orange fruits (Seedless Navel), citric acid, pectin, and sugar were purchased from the local market in Buraidah, Qassim, KSA. All chemicals used for the different chemical analyses were of high purity and were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Orange Puree Preparation

The orange puree was prepared following a clearly defined laboratory procedure. Fresh oranges were sorted to remove defective fruits, washed thoroughly with tap water, and sliced into approximately 2 cm thick pieces. The sliced oranges were then squeezed, and the resulting pulp was blanched in potable water at 100 °C for 10 min. to inactivate enzymes and stabilize color. After blanching, the pulp was homogenized using an electric homogenizer (Molineux SS-193272, ECULLY Cedex, France) for 5 min. until a uniform puree was obtained (Supplementary Figure S1).

2.3. Preparation of orangeJam

The orange jam samples were prepared following the method described by Makanjuola and Alokun (2019) [3]. A control sample was produced using 100% sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), while the experimental samples were formulated by replacing sucrose with date paste at varying proportions (20%, 40%, 50%, and 80%). For all samples, the sugar or its substitute (date paste) was combined with orange puree, pectin, and citric acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and the mixture was heated until reaching a thick consistency corresponding to 65 °Brix. Specifically, for the control sample, 1 kg of sucrose was mixed with 1 kg of orange puree and gently heated with manual stirring under typical jam-processing conditions (approximately 85–95 °C) until the total soluble solids reached 65 °Brix. Subsequently, pectin (5 g per kg of orange with sugar) was added, followed by citric acid (3 g per kg of sugar or sugar-equivalent date paste). The hot jam mixtures were then filled into clean, dry glass jars with tightly fitting lids, immediately cooled to room temperature, and stored until further physicochemical and sensory analyses.

2.4. Chemical Composition and Calorimetric Analysis

The chemical and caloric analysis of the date paste and jam samples was carried out based on dry weight according to the methods mentioned by AOAC [17], calculating the percentage of moisture, ash, and fat (ether extract) using a Soxhlet apparatus, and total protein by the Kjeldahl method (conversion factor for date paste and jam samples is 6.25). The carbohydrate content on a dry basis was calculated by utilizing the following difference-based approach:

Carbohydrate (%) = 100 − (protein [%] + lipids [%] + ash [%]).

The caloric content of orange jam samples was calculated by the following equation:

The energy value (kcal/g) = 4 × (protein [g] + carbohydrate [g]) + 9 × fat [g]

2.5. Determination of Carotenoid Content in Jam Samples

Carotenoids were extracted from jam samples by weighing 5 g of the sample into a separating funnel, followed by the addition of 50 mL of hexane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and gentle shaking. To facilitate phase separation, 20 mL of 10% sodium carbonate solution was added, and after complete separation, the hexane containing carotenoids was collected in a clean volumetric flask. The extraction was repeated 2–3 times with additional hexane to ensure complete recovery, and the combined hexane was filtered through Whatman No. 44 filter paper (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The solvent was evaporated, and the carotenoid residue was re-dissolved in 10 mL of hexane. Spectrophotometric measurements were performed at 450 nm using a Shimadzu UV-1800 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Co., Koyoto, Japan), with pure hexane as the blank. A standard calibration curve was prepared using different concentrations of β-carotene, and the carotenoid content was calculated according to AOAC [17] using the following equation:

Carotenoid content (mg/100 g) = [Carotenoid concentration (mg/mL) × Extract volume (mL)] × 100 / Sample weight (g)

2.6. Estimation of Total Soluble Solids (TSS)

The TSS of orange jam samples was determined in units (°Brix) with a Refractometer (ATAGO POCKET REFRACTOMETER PAL-3) (ATAGO CO., LTD., Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan) according to the method described by AOAC [17].

2.7. Determination of pH

The pH of orange jam samples was determined by using Hanna Instruments (HI2211 pH/ORP Meter), according to the method described by Vijayakumar and Adedeji (2017) [18].

2.8. Determination of Total Acidity in Jam Samples

Total acidity was determined by an aqueous extract of the jam sample by titration with 0.1 N NaOH. For this purpose, 20 g of the jam sample was blended with 380 mL of distilled water and thoroughly homogenized, followed by a filter paper or a clean muslin cloth. A 10 mL aliquot of the filtrate was transferred to a conical flask, and two drops of phenolphthalein were added before titration against 0.1 N NaOH. The total acidity based on citric acid was calculated according to AOAC [17] using the following equation:

Total acidity % = [Volume of NaOH consumed × Normality × Equivalent weight of citric acid (64 g/mol)] × 100 / Sample volume

2.9. Estimation of the Color Attributes of Jam

The impact of date paste incorporation on the color attributes of orange jam samples was assessed. The color parameters measured included lightness (L*, ranging from 0 [black] to 100 [white]), redness (a*, with positive values [+60] indicating red and negative values [−60] indicating green), and yellowness (b*, with positive values [+60] indicating yellow and negative values [−60] indicating blue). Measurements were conducted for the control jam (100% sucrose) and for jam samples containing 20%, 40%, 50%, and 80% date paste. Color determinations were performed using a Hunter Lab Color QUEST II Minolta CR-400 (Minolta Camera Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan), following the procedure outlined by AOAC [17].

2.10. Determination of Mineral Elements

The influence of sugar substitution by date paste on the mineral content of orange jam was evaluated. For mineral analysis, samples were first dried at 105 °C and ground to a uniform powder. Approximately 1 g of each sample was subjected to wet digestion using a mixture of nitric acid (HNO3, 65%) and perchloric acid (HClO4, 70%) in a ratio of 3:1. The digestion was carried out on a hot plate at 120–150 °C until a clear solution was obtained. The digested samples were then transferred to volumetric flasks and diluted to 50 mL with deionized water. Potassium and sodium were quantified using a Flame Photometer (JENWAY). Calcium, iron, copper, and zinc were determined using an Atomic Absorption Flame Emission Spectrophotometer (Shimadzu AA-6200) (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan). Calibration curves were established using certified standard solutions, and results were expressed as mg/100 g dry weight, following AOAC methods [17].

2.11. Determination of Viscosity

The apparent viscosity in centipoise units (cP) of orange jam samples containing different levels of date paste was determined by using the rotational viscometer (Rheotest, type RV2, Pruefgreat, Medingen, Germany) according to the method described by Türkmen et al. (2019) [19].

2.12. Sensory Evaluation of Jam Samples

The sensory properties of the orange jam samples were evaluated by ten trained panelists, all faculty members from the Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition, College of Agriculture and Food, Qassim University. The evaluation included general appearance, color, odor, taste, texture, and overall acceptability, with the control sample serving as a reference. Preference tests were conducted using a 10-point scale, where 10 indicated the highest acceptability and 1 indicated the lowest, following the methodology described by Besbes et al. (2009) [10] (Supplementary Figure S2).

2.13. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis of the obtained results was carried out for three replicates for each of the tests, except for the sensory evaluation, where the number of replicates was 10, and the arithmetic mean of the replicates and significant differences between the coefficients were calculated by Duncan’s test, and the degree of significance at the 0.05 level using SAS (2000) [20].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition of Orange Puree and Date Paste

The results of the chemical analysis, presented in Table 1, showed that the moisture content of the orange puree was 87.94%, while that of the date paste was 24.55%. This result indicates that orange puree has a high moisture content, which may affect the final texture of products made from it. In contrast, the low moisture content of date paste is an advantage for extending the shelf life of products that use dates as the main ingredient, as it reduces the risk of microbial spoilage. The results are consistent with a study indicating that fruits with high water content need advanced preservation techniques to ensure their stability [21]. Statistical analysis revealed that the moisture content of orange puree was significantly higher than that of date paste (p ≤ 0.05).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of orange puree and date paste used in jam preparation (% on wet basis, based on total mass).

The percentages of ash (3.73 and 3.07%), protein (7.38 and 3.00%), ether extract (2.16 and 0.14%), and total carbohydrates (86.73 and 93.79%) were measured as initial composition of the raw materials, namely orange puree and date paste, respectively, prior to jam preparation.

The results are compatible with a previous study showing that oranges have a reasonable percentage of ash, reflecting the presence of minerals such as potassium and calcium [22]. Date paste has the lowest protein content (3.0%) compared to orange puree (7.38%). This indicates that oranges are a reasonable source of protein compared to date paste. It is observed that date paste has the lowest fat (ether extract) content (0.14%) compared to orange puree (2.16%). This may be due to the nature of dates and their low-fat content, making them a suitable choice for low-fat products. While date paste shows the highest percentage of total carbohydrates (93.79%), compared to orange puree (86.73%), this high content of carbohydrates (natural sugars) and dietary fiber in dates is a positive factor for its use as a natural sweetener alternative to sugar in food products, as it imparts a natural sweetness without the need to add refined sugar.

3.2. Chemical Composition and Calorie Content of the Orange Jam

Based on the results presented in Table 2, replacing sucrose with increasing proportions of date paste (0, 20, 40, 50, and 80%) clearly affected the chemical composition and caloric value of the orange jam. A gradual reduction in moisture content was observed as the percentage of date paste increased; the control sample recorded the highest moisture level (30.51%), while the formulation containing 80% date paste showed the lowest value (25.74%). This decrease can be attributed to the inherently lower moisture content of date paste compared to refined sugar formulations. In addition, the progressive decline in water content with increasing substitution levels may also be related to the higher solid content and binding capacity of date paste, which promotes water retention within the matrix and reduces the free water fraction. These findings align with a previous study, which stated that date paste typically has a relatively low moisture content (18–22%) and contributes to a reduction in moisture when incorporated at higher ratios in food formulations [23]. The samples containing date paste recorded higher percentages of ash compared to the control sample, indicating an increase in mineral content. The ash content reached the highest value in the 80% date paste jam sample (2.57%), while the lowest ash value was in the control sample (0.58%). The results indicate a significant increase in ash content as the percentage of sugar substitution with date paste increases, confirming the added nutritional value of these ingredients. This increase directly reflects the higher mineral content in date paste. That is consistent with a previous study that dates contain high concentrations of potassium (650 mg/100 g), magnesium (54 mg/100 g), and calcium (64 mg/100 g), which are essential minerals that directly contribute to the increase in ash content [24]. The study also indicated that these minerals remain bioavailable even after heat treatment.

Table 2.

The effect of replacing sugar with date paste on the chemical composition and calories of orange jam (% based on dry weight).

Referring to Table 2, a significant increase in protein content of jam samples was observed as the percentage of date paste increased. The highest protein content was found in the 80% date paste sample (2.78%), while the lowest protein content was found in the control sample (1.91%). This enhances the nutritional value of the jam by adding date paste, as it contains good proportions of natural proteins. These results are consistent with those of Muñoz-Tebar et al. [25], who found that replacing sugar (protein-free) with date paste by 80% increased the protein content by 45%, improved the amino balance of the final product, and enhanced the functional properties of the protein [25]. There was a slight, nonsignificant decrease in either extract (EE) of the jam as the percentage of date paste increased. The highest percentage of EE was found in the control sample (0.24%), while it decreased to 0.16% in the 80% date paste sample. This decrease may be related to the fat content of date paste (0.14%). The data also showed that total carbohydrates decreased as the percentage of date paste increased, being highest in the control sample (97.27%) and lowest in the 80% date paste sample (94.49%). This reflects that replacing sugar with date paste leads to a reduction in total carbohydrates. There was also a gradual decrease in calories as the percentage of sugar substitution with date paste increased. The control sample was found to have the highest calorie content (398.87 kcal/g), while the lowest caloric value was recorded when using 80% date paste (390.52 kcal/g). This decrease indicates that replacing sugar with date paste reduces the calorie content of the jam, making it a healthier option for consumers looking to reduce calories. These results are consistent with the general trend in some previous studies showed that when replacing sugar with date paste in different proportions in baked goods and jams, resulting in reduced calories, increased mineral content (potassium and magnesium), and enhanced nutritional value while maintaining sensory acceptance [23,26]. The study conducted by Sayas-Barberá et al. (2023) revealed the role of date paste as a natural sweetener alternative to sugar, noting its effect on reducing calories and improving nutritional values, including increased protein and mineral content [23]. Statistical analysis (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05) confirmed that the changes in moisture, ash, protein, total carbohydrates, and calories were statistically significant among the jam samples. Different superscript letters in Table 2 indicate statistically significant differences between treatments. Ether extract showed no significant difference across treatments (p > 0.05).

3.3. Total Carotenoids and TSS of Orange Jam Samples

The results in Table 3 indicate that replacing sugar with date paste positively affects the carotenoid content of orange jam. Statistical analysis (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05) confirmed that carotenoid content significantly differed among the jam samples. Different superscript letters in Table 3 indicate statistically significant differences between treatments. The control sample (0% date paste) had the lowest carotenoid content (0.873 mg/100 g), while the sample with 80% date paste recorded the highest value (0.953 mg/100 g). This gradual increase in carotenoid content can be explained by the fact that date paste contains high levels of natural carotenoids, which are added to the final product when used in jam manufacturing.

Table 3.

Total carotenoids and total soluble solids of orange jam samples containing date paste.

Moreover, this increase could be of health benefit, since carotenoids are known for their antioxidant properties and potential health benefits, such as reducing the risk of chronic diseases. This is consistent with a study by Tanaka et al. [27], which reviews the role of carotenoids in cancer prevention, highlighting their antioxidant properties and potential benefits in reducing the risk of chronic diseases. These results are also consistent with the results of other studies, which confirmed that dates contain high concentrations of carotenoids and polyphenolic compounds, strong antioxidant activity, and showed that the use of dates in jams reduces the need for artificial additives [28,29]. TSS is widely recognized as a key parameter for assessing the quality and processing characteristics of jam products, as it reflects the concentration of soluble solids, including sugars, salts, and other dissolved compounds present in the final product. As shown in Table 3, the gradual replacement of sucrose with date paste during orange jam preparation, up to the point of reaching the desired cooking endpoint and suitable consistency, resulted in a progressive and statistically significant increase in TSS values. The maximum value was observed in the formulation containing 80% date paste (69.90%) compared with 64.40% for the control sample. This notable increase can be primarily attributed to the high content of natural sugars (particularly glucose and fructose) in dates, which are readily soluble and contribute directly to the rise in TSS in the finished product. The use of such natural sugars not only enhances the sweetness perception but may also provide an added nutritional advantage compared to refined sucrose [30]. In addition, the higher TSS resulting from increased date paste incorporation can influence the rheological properties of the jam, leading to a more viscous and stable texture, which is generally perceived positively by consumers. This observation is in line with Sayas-Barberá et al. [23], who reported that the inclusion of date paste in food formulations increases TSS and improves product structure and flavor intensity due to the presence of bioactive compounds and soluble carbohydrates. Moreover, the elevated TSS may improve the preservation potential of jam products, as the high concentration of dissolved solids can limit water activity and consequently reduce microbial growth, thus prolonging shelf-life. This is consistent with the findings of Jammula et al. (2012), who demonstrated that the high sugar content in date-based products enhances stability and reduces spoilage during storage [31].

3.4. Total Acidity and pH Values of Orange Jam

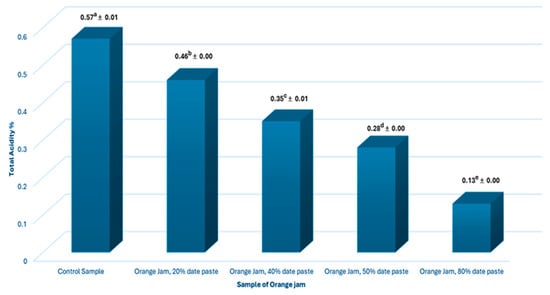

Total acidity was assessed as a key indicator of both product quality and shelf life, given its important role in jam stability and consumer acceptance. As shown in Figure 1, replacing sucrose with date paste had a clear and statistically significant effect on the total acidity of orange jam (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05). A progressive decrease in acidity was observed with increasing levels of date paste, with the control sample exhibiting the highest value (0.57%) and the 80% substitution sample recording the lowest value (0.13%). This decrease may be explained by the fact that dates contain mainly natural sugars and minerals, which exert a lower acidifying effect compared to refined sucrose [32]. The reduction in total acidity may result in a sweeter taste and a smoother mouthfeel, thus improving the acceptability of the product for consumers who prefer jams with a mild taste profile. Although higher acidity generally contributes to increased shelf life, the high sugar content and presence of bioactive components in date paste can exert a natural preservative effect and partially compensate for the reduced acidity.

Figure 1.

Total acidity (%) of orange jam samples containing different levels of date paste. Data are expressed as means ± standard error, number of replicates = 3. Data followed by the same letter are not significantly different (p ≤ 0.05).

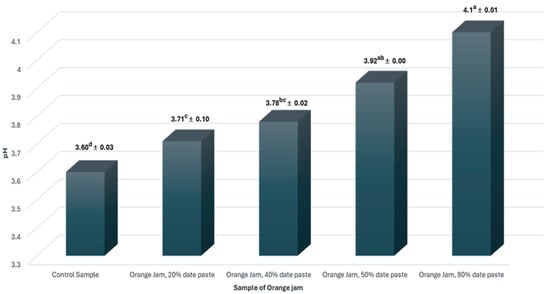

The pH of the control sample was 3.60 and gradually increased to 4.10 in the sample containing 80% date paste, as shown in Figure 2. This trend can be attributed to the relatively alkaline nature of dates compared to oranges; date paste contains large amounts of natural sugars and alkaline minerals such as potassium, magnesium, and calcium, which contribute to neutralizing the acidity of the jam mixture. This is consistent with previous studies that reported the incorporation of date paste into jam resulted in a significant pH increase during processing, which may influence the product’s sensory characteristics [33,34]. A moderate reduction in acidity can improve the flavor profile and enhance consumer acceptance by producing a milder, less sharp taste. However, the effects on preservation and the physicochemical stability of the product should be carefully considered. The present results are also consistent with Farahnaky et al. [35], who observed similar increases in pH (0.4–0.5 units per 20% date paste substitution) while reporting improved microbial stability due to the presence of phenolic compounds in dates.

Figure 2.

pH of orange jam samples containing different levels of date paste. Data are expressed as means ± standard error, number of replicates = 3. Data followed by the same letter are not significantly different (p ≤ 0.05).

3.5. Color Values for Orange Jam Samples

The results presented in Table 4 showed that the incorporation of date paste produced pronounced changes in the color attributes of orange jam. A significant decrease in lightness (L) was observed as the proportion of date paste increased, with the control sample showing the highest lightness value (57.77), in contrast to the formulation containing 80% date paste, which recorded a markedly lower value (39.31). Statistical analysis (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05) confirmed significant differences among treatments for all color parameters, indicating a clear effect of date paste substitution on jam color.

Table 4.

The effect of replacing sugar with different proportions of date paste on the color properties of orange jam.

This reduction in brightness is most likely due to the intrinsic dark color of date paste, which reduces light reflection and results in a less glossy appearance. Conversely, the redness parameter (a*) increased progressively and significantly from 7.88 in the control sample to 30.78 in the 80% substitution sample. This marked increase can be explained by the natural reddish-brown pigments present in dates, which intensify the reddish hue of the final product. Regarding the yellow color component (b*), a gradual decrease was observed from 43.44 for the control sample to 23.19 in the 80% substitution sample, suggesting a shift in the chromatic balance of the jam as yellow in orange tones are replaced by the deeper tones of the date paste. These findings align with a previous study that demonstrated that sugar substitution with date paste in orange jam leads to a decrease in lightness and a pronounced increase in redness, although slight differences in the yellow component were recorded [36]. Overall, the color parameters show statistically significant differences across treatments (p ≤ 0.05), confirming the strong influence of date paste on the visual attributes and potential consumer perception of orange jam during storage (Supplementary Figure S3).

3.6. Mineral Elements of Orange Jam Samples

The data presented in Table 5 clearly demonstrate that replacing sucrose with date paste in orange jam formulations produces a significant enhancement in mineral composition, particularly for potassium, iron, and calcium, while simultaneously reducing sodium content. Potassium levels increased markedly from 370 ppm in the control sample to 7866 ppm in the 80% date paste formulation. In contrast, sodium content decreased progressively from 560 ppm in the control to 372 ppm at 80% substitution.

Table 5.

Effect of replacing sugar with different proportions of date paste on the mineral content of orange jam.

Similar trends were observed for calcium, which increased from 380 ppm in the control to 650 ppm in the 80% date paste sample. In addition, there was a significant and gradual rise in iron content from 1.50 ppm in the control to 14.82 ppm with 80% substitution. Concentrations of both copper and zinc also increased significantly with higher levels of date paste, where they up from 0.90 ppm to 2.90 ppm and 0.40 ppm to 2.56 ppm, respectively. Statistical analysis confirmed that these differences were significant (ANOVA, p ≤ 0.05), indicating a clear dose-dependent effect of date paste on mineral enhancement. These improvements can be attributed to the naturally high mineral content of date paste, which contributes to the overall nutritional enhancement of the product. These findings are consistent with those reported by AlFaris et al. [37], who highlighted that dates are rich in potassium (≈650 mg/100 g), iron (≈12 mg/100 g), and calcium (≈64 mg/100 g), while being low in sodium (≈2 mg/100 g). From a nutritional perspective, high potassium contributes to regulating blood pressure, iron plays a crucial role in preventing anemia, and calcium is essential for bone health [38]. Furthermore, the low sodium content of jam may be beneficial for individuals on low-sodium diets, which emphasizes the role of dates in developing healthy, low-sodium food products [33,39]. The replacement of sugar with date paste significantly improved the mineral profile of orange jam, enhancing its nutritional value while maintaining significant statistical differences among treatments (p ≤ 0.05).

3.7. Viscosity of Orange Jam Samples

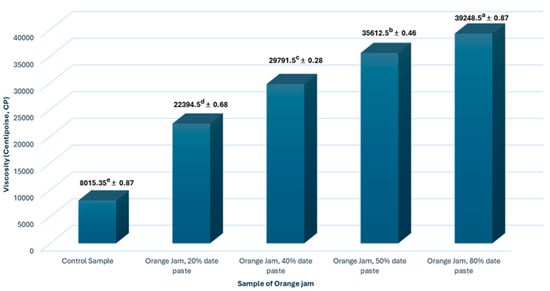

The results presented in Figure 3 revealed a clear and statistically significant increase in viscosity as the proportion of date paste in the orange jam formulation increased. The control sample (0% date paste) exhibited the lowest viscosity value (8015.35 cP), whereas the sample containing 80% date paste reached the highest value (39248.50 cP).

Figure 3.

Viscosity of orange jam containing different proportions of date paste. Data are expressed as means ± standard error, number of replicates = 3. Data followed by the same letter are not significantly different (p ≤ 0.05).

This pronounced rise in viscosity may be attributed to the high content of soluble fibers and natural sugars found in dates, which enhance the thickening capacity of the product and contribute to a more structured gel network in the jam matrix. Similar findings were reported by Shahein et al. [32], who observed that increasing the level of date paste in jam formulations resulted in a marked improvement in rheological behavior, including a 35–40% increase in the elastic modulus and greater textural stability during storage. Such improvements in viscosity and rheological parameters are considered desirable in jam products, as they contribute to better spreadability and overall product quality.

3.8. Sensory Evaluation of Orange Jam Samples

The results presented in Table 6 indicate that replacing sugar with date paste at levels of 20% or 40% did not significantly compromise the sensory attributes of orange jam (appearance, color, odor, taste, texture, and overall acceptability; p ≤ 0.05), while slightly enhancing certain characteristics such as texture and taste.

Table 6.

The effect of replacing sugar with different proportions of date paste on the sensory properties of orange jam.

This suggests that moderate substitution can improve nutritional value without negatively affecting consumer acceptance. The 20% date paste sample achieved the highest overall acceptability score (47.7), followed closely by the 40% sample (46.3), both statistically classified as “a,” indicating a clear preference over the control (0% date paste), which was rated with “ab” significance. This higher sensory preference at 20–40% substitution is likely due to the balanced sweetness, improved texture, and enhanced flavor harmony contributed by moderate levels of date paste. In contrast, the 80% date paste formulation received the lowest acceptability score (42.4) and was classified with “b” significance, reflecting a reduced consumer preference at high substitution levels. Substitutions of 50% or more caused a noticeable decline in key sensory attributes, particularly color, appearance, and taste, likely due to the overpowering influence of date paste on the natural orange flavor and the darkening of the jam’s color. These findings highlight that moderate substitution (20–40%) can enhance nutritional value without negatively affecting sensory acceptance, whereas higher levels (>50%) adversely impact consumer preference. These align with a previous study, which reported that moderate substitution (around 30%) yielded the highest sensory evaluation scores (7.8/10), whereas higher replacement levels (50–70%) led to progressive declines in overall acceptability (6.2–4.5/10) [37], confirming that excessive addition of date paste can adversely affect sensory quality.

4. Conclusions

The incorporation of date paste as a substitute for refined sugar in orange jam markedly enhances its nutritional profile. Higher substitution ratios increase carotenoids, protein, and essential minerals, particularly calcium and potassium, while reducing calories and sodium, which is beneficial for individuals with hypertension. Optimal substitution levels of 20–40% preserve desirable texture and flavor while providing significant nutritional benefits. Expanding the use of locally produced date products in the food industry, including bakery and confectionery sectors, can promote natural sweeteners, support the national agricultural economy, and foster environmental sustainability, in line with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. Future studies should investigate the effects of storage on the physicochemical and sensory properties of date-paste-enriched jams and explore their potential application in other food products.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr13123956/s1, Figure S1. The appearance and color of prepared orange puree are used in jam processing; Figure S2. Evaluation of sensory properties of orange jam samples enriched with date paste; Figure S3. Color of orange jam samples containing different levels of date paste.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.-S.A.A.E.-H. and N.A.A.; methodology, E.H.F., Z.A.S., and M.G.E.G.; software, E.-S.A.A.E.-H.; validation, N.A.A. and M.G.E.G.; formal analysis, E.H.F.; investigation, Z.A.S.; resources, E.H.F., Z.A.S., and M.G.E.G.; data curation, E.-S.A.A.E.-H.; writing—original draft preparation, E.H.F., Z.A.S., and M.G.E.G.; writing—review and editing, E.-S.A.A.E.-H. and N.A.A.; visualization, E.H.F.; supervision, Z.A.S.; project administration, N.A.A.; funding acquisition, N.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University (QU-APC-2025).

Data Availability Statement

All the data are available in the current text.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at Qassim University for financial support (QU-APC-2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| cP | Centipoise units |

| TSS | total soluble solids |

References

- Krivokapić, S.; Pejatović, T.; Perović, S. Chemical Characterization, Nutritional Benefits, and Some Processed Products from Carrot (Daucus carota L.). Agric. For. 2020, 66, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, F.; Santos, B.A.D.; Nunes, G.; Soares, J.M.; Amaral, L.A.D.; Souza, G.H.O.D.; Novello, D. Addition of Orange Peel in Orange Jam: Evaluation of Sensory, Physicochemical, and Nutritional Characteristics. Molecules 2020, 25, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makanjuola, O.M.; Alokun, O.A. Microbial and Physicochemical Properties of Date Jam with Inclusion of Apple and Orange Fruits. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 4, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, M.S.; Yeasmin, F.; Khan, M.J.; Riad, M.H. Evaluation of Quality Characteristics and Storage Stability of Mixed Fruit Jam. J. Food Res. 2021, 5, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vavoura, M.V.; Karabagias, I.K.; Kosma, I.S.; Badeka, A.V.; Kontominas, M.G. Characterization and Differentiation of Fresh Orange Juice Variety Based on Conventional Physicochemical Parameters, Flavonoids, and Volatile Compounds Using Chemometrics. Molecules 2022, 27, 6166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, M.; Manikas, I.; Maqsood, S.; Stathopoulos, C. Date Components as Promising Plant-Based Materials to Be Incorporated into Baked Goods—A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, G.A.; El-Samahy, S.K.; Abd El-Hady, E.A.; Abd El-Fadeel, M.G. Production of Date Nectars. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2002, 47, 695–705. [Google Scholar]

- Alsuheban, H.; Sakr, S.S.; Elkashef, H.; Algheshairy, R.M.; Alfheeaid, H.A.; Algeffari, M.; Alharbi, H.F. Novel High Protein-Energy Balls Formulated with Date Paste Enriched with Samh Seeds Powder and/or Different Milk Protein Origins: Effect on Protein Digestibility In Vitro and Glycemic Response in Young Adults. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1538441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.M.F.; El-Rashody, M. Effect of Camel Milk Fortified with Dates in Ice Cream Manufacture on Viscosity, Overrun, and Rheological Properties during Storage Period. Food Nutr. Sci. 2017, 8, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besbes, S.; Blecker, C.; Deroanne, C.; Drira, N.E.; Attia, H. Adding Value to Hard Date (Phoenix dactylifera L.): Compositional, Functional and Sensory Characteristics of Date Jam. Food Chem. 2009, 112, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Samahy, S.K.; Habiba, R.A.; Gab-Alla, A.A. Preparation and Protein-Fortification of Date Bars. Egypt. J. Food Sci. 2005, 33, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Hady, E.A.; Alfheeaid, H.A.; Abd El-Razik, M.M.; Althwab, S.A.; Barakat, H. Nutritional, Physicochemical, and Organoleptic Properties of Camel Meat Burger Incorporating Unpollinated Barhi Date Fruit Pulp. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 2022, 4581821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, Y.A.; Alnafissa, M.A.; Kotb, A.; Alagsam, F.; Aldakhil, A.I.; Alfadil, I.E.; Al-Qunaibet, M.H.; Alaagib, S. Estimating the Expected Commercial Potential of Saudi Date Exports to Middle Eastern Countries Using the Gravity Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Date Palm and Dates. Annual Report 2024; National Center for Date Palm and Dates: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2024.

- Almuziree, R.S.; Alhomaid, R.M. The Effect of Sugar Replacement with Different Proportions of Khalas Date Powder and Molasses on the Nutritional and Sensory Properties of Kleicha. Processes 2023, 11, 3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musthafa, M.; Sandhu, D. Utilization of Dates for the Formulation of Functional Food Products. J. Pharm. Innov. 2022, 17, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De C Tobaruela, E.; De O Santos, A.; De Almeida-Muradian, L.B.; Da S Araujo, E.; Lajolo, F.M.; Menezes, E.W. Application of Dietary Fiber Method AOAC 2011.25 in Fruit and Comparison with AOAC 991.43 Method. Food Chem. 2018, 238, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, P.P.; Adedeji, A.A. Measuring the pH of Food Products; University of Kentucky, College of Agriculture, Food and Environment, Cooperative Extension Service: Lexington, KY, USA, 2017; Publication No. ID-246. [Google Scholar]

- Türkmen, F.U.; Takcı, H.A.M.; Seyhan, B.; Palta, T. Investigation of Some Quality Parameters of Sour Cherry Concentrates Produced under Atmospheric and Vacuum Conditions. Karadeniz Fen Bilim. Derg. 2019, 9, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS Institute. SAS/STAT User’s Guide; Version 8.1; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, M.A.; Khan, A.S.; Azam, M.; Ayyub, S.; Kaleem, M.M.; Nawaz, S.; Ateeq, M. Innovative Technologies in Postharvest Management of Fruits and Vegetables: A Review. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2025, 251, 3445–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, P.; Dudeja, I.; Pooja Singh, A.; Purewal, S.S.; Kaur, A.; Swamy, C.T. Orange. In Recent Advances in Citrus Fruits; Singh Purewal, S., Punia Bangar, S., Kaur, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayas-Barberá, E.; Paredes, C.; Salgado-Ramos, M.; Pallarés, N.; Ferrer, E.; Navarro-Rodríguez de Vera, C.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.Á. Approaches to Enhance Sugar Content in Foods: Is the Date Palm Fruit a Natural Alternative to Sweeteners? Foods 2023, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, S.A.; Rahman, S.; Khan, M.M.; Rafiq, S.; Inayat, A.; Khurram, M.S.; Jamil, F. Potential of Dates (Phoenix dactylifera L.) as a Natural Antioxidant Source and Functional Food for Healthy Diet. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 141234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Tebar, N.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Fernandez-Lopez, J.; Perez-Alvarez, J.A. Strategies for the Valorization of Date Fruit and Its Co-Products: A New Ingredient in the Development of Value-Added Foods. Foods 2023, 12, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, N.K.; Alnemr, T.M.; Ahmed, A.R.; Ali, S. Effect of Inclusion of Date Press Cake on Texture, Color, Sensory, Microstructure, and Functional Properties of Date Jam. Processes 2022, 10, 2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Shnimizu, M.; Moriwaki, H. Cancer Chemoprevention by Carotenoids. Molecules 2012, 17, 3202–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alu’datt, M.H.; Rababah, T.; Tranchant, C.C.; Al-‘u’datt, D.A.; Gammoh, S.; Alrosan, M.; AbuJalban, D. Date Palm (Phoenix dactylifera) Bioactive Constituents and Their Applications as Natural Multifunctional Ingredients in Health-Promoting Foods and Nutraceuticals: A Comprehensive Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray, N.; Gullón, B.; Pateiro, M.; Amarowicz, R.; Misihairabgwi, J.M.; Lorenzo, J.M. Date Fruit and Its By-Products as Promising Source of Bioactive Components: A Review. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 1411–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, S.; Rehman, T.; Saif, S.; Rajoka, M.S.R.; Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Hassoun, A.; Cropotova, J.; Trif, M.; Younas, A.; Aadil, R.M. Replacement of Refined Sugar by Natural Sweeteners: Focus on Potential Health Benefits. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jammula, S.; Kota, S.; Kota, S.; Meher, L.; Modi, K.; Krishna, S.S.; Rao, E. Nutraceuticals in Pathogenic Obesity: Striking the Right Balance between Energy Imbalance and Inflammation. J. Med. Nutr. Nutraceut. 2012, 1, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Shahein, M.R.; Atwaa, E.S.H.; Elkot, W.F.; Hijazy, H.H.A.; Kassab, R.B.; Alblihed, M.A.; Elmahallawy, E.K. The Impact of Date Syrup on the Physicochemical, Microbiological, and Sensory Properties, and Antioxidant Activity of Bio-Fermented Camel Milk. Fermentation 2022, 8, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nateghi, L. Effect of Sugar Replacement with Date Syrup on Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Quince Jam. Food Health 2022, 5, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ghahremannejad, N.; Alizadeh, M.; Pirsa, S. Partial Substitute of Sugar with Date Concentrate in the Peach/Apple Juice and Study Physicochemical/Color Properties of Blend Fruit Juice. Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 13, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahnaky, A.; Hosseini, N.; Mohammadi, A. Physicochemical Properties of Date Juice Concentrate and Comparison with Other Fruit Juice Concentrates. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2016, 40, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Manickvasagan, A.; Kumar, C.S.; Al-Attabi, Z.H. Effect of Sugar Replacement with Date Paste and Date Syrup on Texture and Sensory Quality of Kesari (Traditional Indian Dessert). J. Agric. Mar. Sci. [JAMS] 2017, 22, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlFaris, N.A.; AlTamim, J.Z.; AlMousa, L.A.; Albarid, N.A.; AlGhamidi, F.A. Nutritional Values, Nutraceutical Properties, and Health Benefits of Arabian Date Palm Fruit. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2023, 35, 488–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Potassium Intake for Adults and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Adegbanke, O.R. Chemical Composition and Sensory Evaluation of Jam Produced from Pawpaw, Apple, Banana, and Orange Fruit. Nutr. Food Process. 2025, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).