Abstract

This study investigated the effects of heat treatment on the surface properties, structure, and Pb(II) sorption capacity of natural clinoptilolite zeolite (Nat-CLI). For this purpose, 10 g samples of Nat-CLI were heated separately at 300, 400, and 500 °C for two hours. The resulting samples were labeled CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500, respectively. The samples were characterized using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis, and point of zero-charge (pHpzc) measurements. XRD results confirmed that the crystal structure of Nat-CLI remained unchanged after heat treatment, a finding supported by FT-IR and TGA analyses. BET analysis revealed that the heating temperature altered both the specific surface area (SBET) and the mean pore diameter. The values were as follows: SBET = 16.5, 14.1, 14.4, and 14.9 m2/g and mean pore diameter = 38.1, 36.0, 48.6, and 36.0 Å for Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500, respectively. The results of the kinetic study showed that the pseudo-second order model best agreed with the experimental data for all adsorbents. The maximum sorption capacities of Pb(II) were 28.26, 32.96, 34.69, and 33.85 mg/g for Nat-CLI and CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500, respectively. These results suggest that the sample treated at 400 °C (CLI-400) achieved the highest sorption capacity due to its larger mean pore diameter.

1. Introduction

Zeolites consist of tetrahedral XO4 units, where X is typically silicon (Si) or aluminum (Al). These tetrahedra are interconnected through corner-sharing oxygen atoms, forming a three-dimensional microporous framework [1]. Additionally, the aluminum and silicon atoms within the zeolite framework can be replaced with other elements, such as boron (B), beryllium (Be), cobalt (Co), iron (Fe), gallium (Ga), germanium (Ge), magnesium (Mg), phosphorus (P), titanium (Ti), and zinc (Zn) [1].

Based on their Si/Al ratio, zeolites are classified into three categories: low-silica zeolites (Si:Al = 1–2; SiO2:Al2O3 = 1.18–2.35), medium-silica zeolites (Si:Al = 2–5; SiO2:Al2O3 = 2.35–5.88), and high-silica zeolites (Si:Al > 5; SiO2:Al2O3 > 5.88) [2]. The Si/Al ratio determines their physical and chemical properties. A low ratio makes them hydrophilic, and a high ratio makes them hydrophobic [3,4,5,6]. Zeolites have become valuable materials in multiple applications, including water purification, fuel cells, and renewable energy production, due to their ion-exchange capacity, thermal stability, and well-defined cage structures [2,7,8]. Their porous structure and uniform pore sizes also make zeolites suitable for use as catalysts, adsorbents, and ion exchangers [9,10,11,12]. Zeolites are widely used to remove metal ions from solutions because of their high ion-exchange capacity, porosity, and surface area. They are abundant and inexpensive, and they can be regenerated with saline or acidic solutions. These natural materials are highly effective at removing Pb(II) ions due to the high charge density and low hydration energy of lead, which favor its interaction with the zeolite framework [13]. Additionally, zeolites are a sustainable alternative to synthetic materials such as metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) and activated carbons (ACs) because they are naturally abundant and chemically stable. They also do not require complex synthesis or costly precursors. Their negatively charged aluminosilicate framework promotes the retention of lead (Pb(II)) through ion exchange and electrostatic attraction. Unlike ACs, which require energy-intensive reactivation, and MOFs, which suffer from hydrolytic instability, zeolites can be easily regenerated using mild saline or acidic solutions [1,13,14,15].

To improve their performance, zeolites can undergo chemical or thermal modification [14,16]. Chemical treatments often include ion exchange, which involves exposing the zeolite to a concentrated solution of specific cations. This alters its acid–base, redox, and structural properties [5]. For example, Min et al. used Ag-exchanged zeolite for nitrogen and oxygen adsorption, as well as mercury removal [17]. Similarly, grafting of amines, silanes, or inorganic acids onto the zeolite framework reduces its hydrophilicity while maintaining affinity for CO2 [18]. Using silanes (e.g., tetraethoxysilane), in vapor or liquid deposition can modify the textural and catalytic characteristics by decreasing pore size and diffusivity [19]. Regarding thermal treatment, temperature can induce structural changes such as unit cell modifications, partial collapse, and framework breakdown. Temperature can also promote cation migration and dehydration processes within the channels [20]. Previous studies have examined the effects of thermal or chemical treatments on the structure of clinoptilolite. However, none have systematically correlated surface modifications induced by thermal treatment with Pb(II) adsorption capacity under identical experimental conditions.

In this context, heat-treated clinoptilolite is a novel and sustainable method for the adsorption of heavy metals. Studies have shown that thermal treatment at temperatures up to 500 °C effectively removes impurities and increases the material’s surface area, porosity, and surface chemistry, all without degrading the crystal structure [2]. As a result, the adsorption capacity for Pb(II) can be significantly improved. This process aligns with green chemistry principles, offering an eco-friendly, sustainable alternative to acid activation methods [21].

Thus, this study examined how heating temperature affects the surface and structural properties of natural clinoptilolite and its impact on adsorption capacity for Pb(II) removal. The three tested temperatures were 300, 400, and 500 °C. The samples were characterized using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM)/energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis, and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). The pH point of zero charge (pHPZC) was also determined. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms were used to evaluate textural parameters. These characterization methods revealed a relationship between structural stability and Pb(II) adsorption performance. The adsorption data were fitted to the Langmuir, Freundlich, Dubinin–Radushkevich, Temkin, and Redlich–Peterson isotherms using the Microsoft Excel’s Solver tool. Additionally, adsorption–desorption cycles were conducted to evaluate the reusability of the zeolites.

These analyses allowed us to propose a structural correlation model that explains the superior adsorption capacity of the sample treated at 400 °C (CLI-400). This model expands our understanding of the impact of thermal treatment on natural zeolites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Samples and Reagents

A clinoptilolite-rich tuff with a grain size of 40 mesh was obtained from a deposit in Puebla, Mexico. The material was washed repeatedly with deionized water (18.2 MΩ·cm−1 resistivity) to remove dust and impurities and then dried in an oven at 80 °C for 24 h. This prepared sample was designated as Nat-CLI. For thermal modification, ten grams of Nat-CLI were placed in an alumina crucible and heated in a Thermolyne furnace at a rate of 10 °C/min until reaching 300 °C. The sample was then held at this temperature for two hours before being cooled to 25 °C at the same rate. This sample was labeled CLI-300. The same procedure was followed to prepare the samples CLI-400 and CLI-500. The heating temperatures of 300, 400, and 500 °C were selected to evaluate the progressive stages of dehydration and dehydroxylation that clinoptilolite undergoes, as reported in the literature [2].

A stock solution of lead was prepared using deionized water and PbCl2 salt (JT Baker, 99.99%). All required concentrations were derived from this solution.

2.2. Characterization Techniques

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a TA Instruments SDT Q600 to investigate the effect of heat treatment on the structure of a natural clinoptilolite zeolite. The analysis was conducted from 13 to 900 °C.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was performed using a Nicolet Nexus 670 FTIR spectrometer. Spectra were acquired in the wavenumber range of 400–4500 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1 using KBr wafers (SpectroGrade, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were acquired using an APD 2000 PRO diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å). Data were collected over a 2θ range of 5° to 70°, with a step size of 0.025° and a counting time of 15 s per step.

The sample morphology was studied using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and the chemical composition was determined using energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS/EDX) with a Hitachi S-3400N system equipped with an EDAX 9900 device.

To investigate the surface properties further, the point of zero charge (pHPZC) was determined for the natural and heat-treated zeolites. A 0.01 M NaCl solution was used as the background electrolyte. The initial pH of the working solutions was adjusted to values between 1 and 11 (specifically 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11) using 0.1 M solutions of NaOH and/or HCl. The pH was measured using a Hanna Instruments pH meter (model HI2020-01). Then, 0.5 g of each zeolite was added to the solutions, which were agitated at 120 rpm and ambient temperature for 24 h. After agitation, the solutions were decanted, and the final pH was measured. The pHPZC was identified as the point at which the final pH versus initial pH curve intersects the diagonal line, meaning that the final pH equals the initial pH [22].

The textural properties, including the specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution, were determined from N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms measured at 77 K. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) and Langmuir models were applied to calculate the surface area. The total pore volume was assessed by the Gurvich rule at a relative pressure of P/P0 ≈ 0.99, and the external surface area was determined using t-plot analysis. Furthermore, the pore size distribution was evaluated using the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method on the desorption branch of the isotherm [23].

2.3. Sorption Process

The sorption process was performed using the batch technique. For kinetic study, 10 mL of a Pb(II) solution with initial concentration of 100 m/L was mixed with a 0.1 g of each zeolite in centrifuge tubes, and agitated at 150 rpm using a rotary shaker (Cscientific CVP-0228) for 15, 30, 60, 120, 180, 360, 760, and 1440 min. After each contact time, the samples were centrifuged at 3500 rpm for five minutes using a CRM Globe (Certificient, Chicago, IL, USA) to separate the solid adsorbents from the liquid solutions. The resulting liquid samples were filtered using a Whatman No. 40 filter and diluted with deionized water, if necessary, to ensure that the lead concentration was within the linear calibration curve of the atomic absorption spectrometry (iCE series, Thermo Scientific iCE 3000 series, Waltham, MA, USA). The concentration of Pb(II) before and after contact with the adsorbent materials was determined by extrapolating the measured absorption at 217 nm.

The amount of Pb(II) removed by the natural and thermally modified zeolites was determined using the following equation:

where C0 (mg/L) is the initial concentration, Ce (mg/L) is the equilibrium concentration, qe (mg/g) is the adsorption capacity at equilibrium, V (L) is the volume of the solution, and m (g) is the mass of the adsorbent.

For isotherm study, a volume of 10 mL volume of Pb(II) ion solution with a concentration ranging from 10 to 1000 mg/L was placed in contact with 0.1 g of Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500. The samples were shaken at 150 rpm for 24 h using an orbital shaker. After separation by centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 2 min, the same procedure was carried out to determine the residual concentrations by AAS, using Equation (1) formula.

All experiments were performed in duplicate, and the results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation.

Kinetic data were analyzed by fitting the pseudo-first-order (Equation (2)) and pseudo-second-order (Equation (3)) nonlinear models.

where qe and qt are the adsorption capacities at equilibrium and at time t (mg/g). k1 (min−1) and k2 (g mg−1 min−1) are the rate constants of the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models, respectively.

The experimental equilibrium data were fitted to the following nonlinear isotherm models: Langmuir (Equation (4)), Freundlich (Equation (5)), Dubinin–Radushkevich (Equation (6)), Temkin (Equation (7)), and Redlich–Peterson (Equation (8)). The fitting was performed using the Solver add-in in Microsoft Excel.

where KL (L/mg is the Langmuir equilibrium constant, and qm (mg/g) is the maximum adsorption capacity.

where n (dimensionless) and KF (mg/g)(L/mg)1/n are the exponent and the Freundlich parameter, respectively.

where qm (mg/g) is the maximum adsorption capacity of the sorbent for Pb(II). KD (mol2kJ2) is the Dubinin–Radushkevich isotherm constant related to the free energy of adsorption and R (8.314 J/mol K) is the gas constant. T (K) is the absolute temperature. Additionally, E (kJ/mol) is the mean free energy of sorption, and it can be calculated by the following equation:

Temkin isotherm model is presented by Equation (7)

where b (KJ/mol) is the constant related to the heat of sorption and At (L/mg) is the Temkin isotherm equilibrium binding constant.

where KRP (L/g), αRP (L/mg) are the constant of the Redlich–Peterson and β is a dimensionless parameter between 0 and 1.

In addition to the coefficient of determination (R2), three error functions were used to evaluate the model fit: the sum of squared errors (SSE), the chi-square test (χ2), and the root mean square error (RMSE). These metrics were used to assess the accuracy of the experimental data and the suitability of the kinetic and isotherm models. The corresponding calculations for SSE, χ2, and RMSE are given by Equations (9), (10) and (11), respectively.

2.4. Adsorption/Desorption Experiments

The reusability of natural and heated clinoptilolites was evaluated through successive adsorption–desorption cycles for Pb(II). In the first adsorption cycle, 50 mL of metal solution (500 mg/L) was mixed with 10 g/L of each zeolite at 25 °C, and agitated at 150 rpm for 24 h. Residual metal concentrations were determined by AAS. For desorption, the metal-loaded adsorbents were separated by centrifugation, then placed in contact with 50 mL of 0.1 M HCl under the same agitation conditions for 24 h. The solid phase was then thoroughly washed with deionized water, dried at 60 °C, and reused in the next adsorption cycle. In subsequent cycles, the solution and eluent volumes were adjusted to maintain an approximately constant solid–liquid ratio of 10 g/L. This procedure was repeated for three consecutive cycles.

The desorption capacity (qDes, mg/g) was calculated using Equation (12).

where Cdes is the concentration of the desorbed metal ion (mg/L), V is the volume of the eluent (L), m is the mass of the adsorbent (g).

3. Results

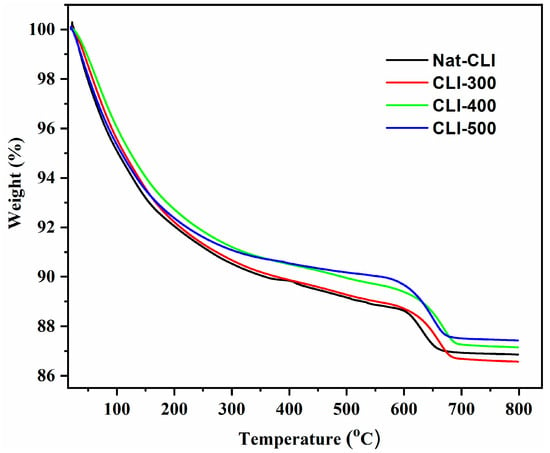

3.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

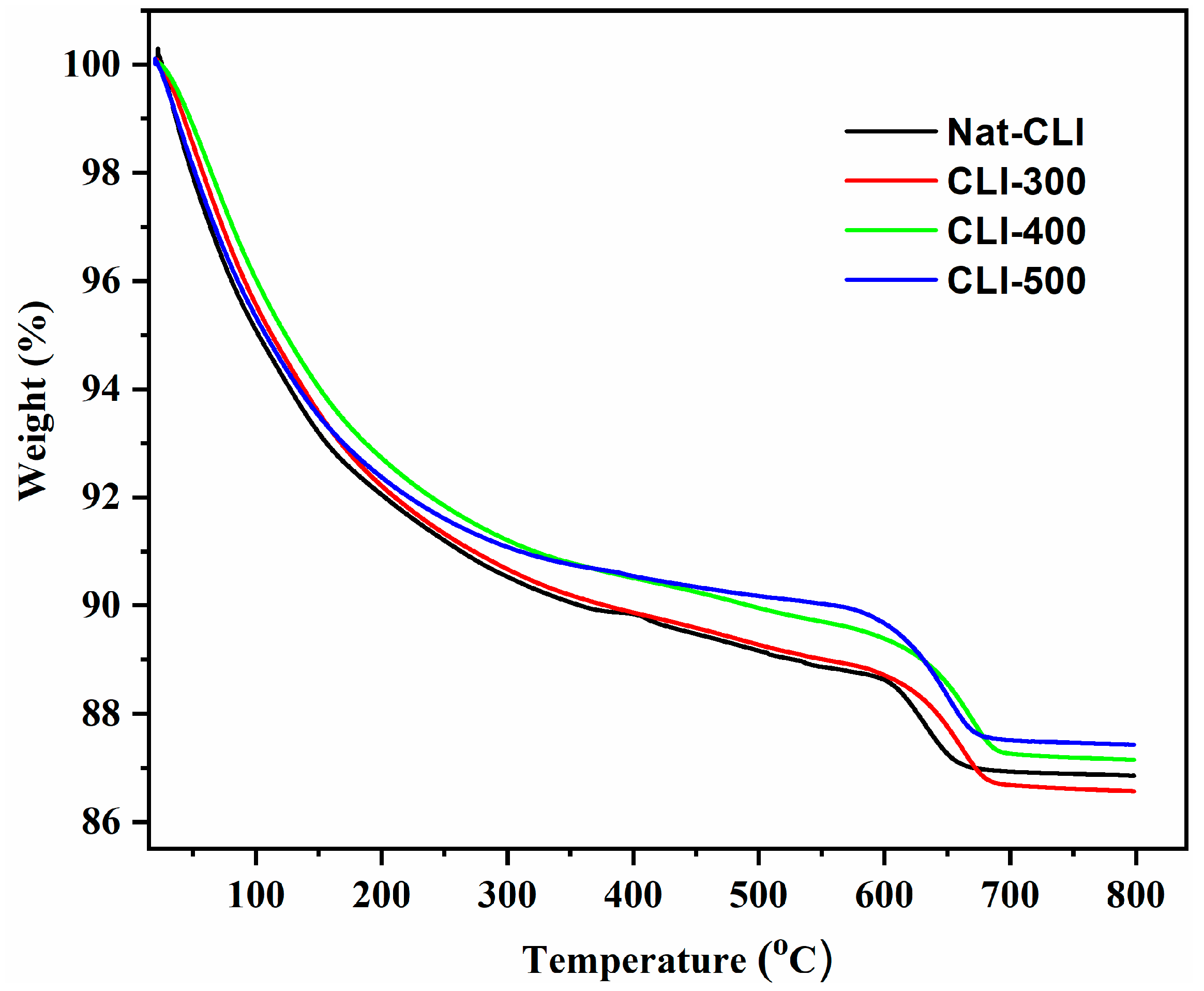

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed by heating the samples from room temperature to 800 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere. Figure 1 presents the TGA curves for the Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500 zeolites. Since the presence of different exchangeable cations significantly influences the dehydration temperature [21] the percentage weight loss was quantified within specific temperature intervals. The corresponding mass losses for the temperature ranges of 25–100 °C, 100–200 °C, 200–300 °C, 300–400 °C, 400–600 °C, and 600–800 °C are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Thermogravimetric curves of the Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400 and CLI-500 samples.

Table 1.

Weight loss (%) of the Clinoptilolite samples in different temperature ranges.

In the initial stage of thermogravimetric analysis (25–100 °C), the mass loss observed for all samples (Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500) is primarily due to water desorption [24,25]. Significant weight loss was recorded for all samples up to 200 °C and is attributed to the removal of physically adsorbed water confined in the clinoptilolite channels and water coordinated to exchangeable cations [26]. As the temperature increased to the 200–300 °C range, the weight loss rate decreased, as indicated by the reduction in slope of the TGA curves in Figure 1. This progressive dehydration aligns with the finding that heat treatment effectively removes both surface water and water from the internal structure of clinoptilolite [27]. The results confirm that thermal treatment significantly reduces the water content associated with silanol groups in the zeolite framework [25]. The trend of minimal weight loss was maintained in all calcined samples within the 300–400 °C range. Similarly, only marginal mass loss was observed between 400 and 500 °C consistent with previous studies [23,24]. Notably, the most significant weight loss occurred within the 500–600 °C range. In this range, the TGA curve exhibited a steeper slope compared than in lower temperature intervals (<500 °C) [24,27]. The Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500 samples all demonstrated high thermal stability, as evidenced by a continuous mass loss up to 690 °C and the preservation of their structural integrity within the 600–800 °C range [25,26,27,28]. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating that the crystalline structure of clinoptilolite typically collapses at around 800 °C [25].

3.2. SEM and EDS Analysis

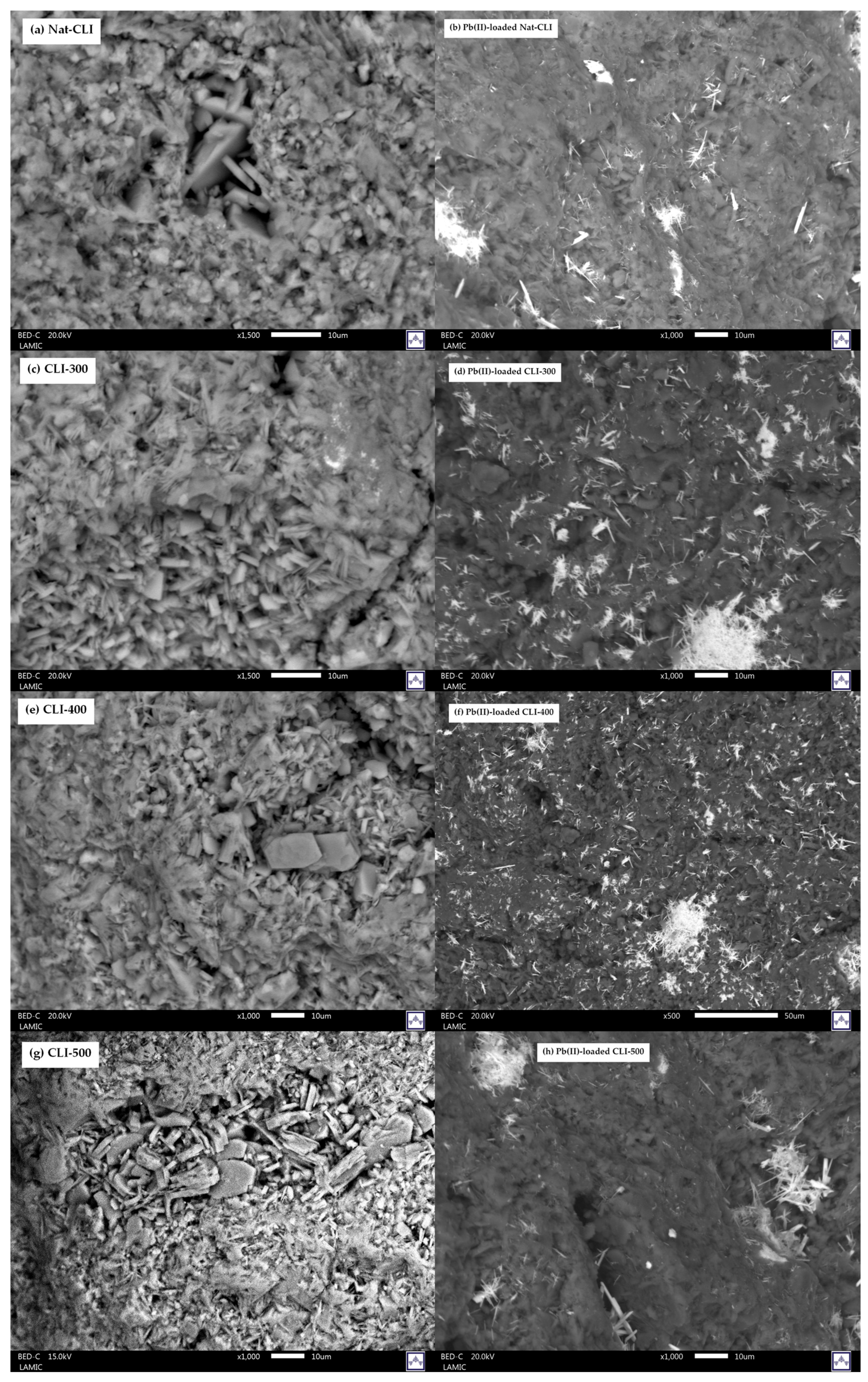

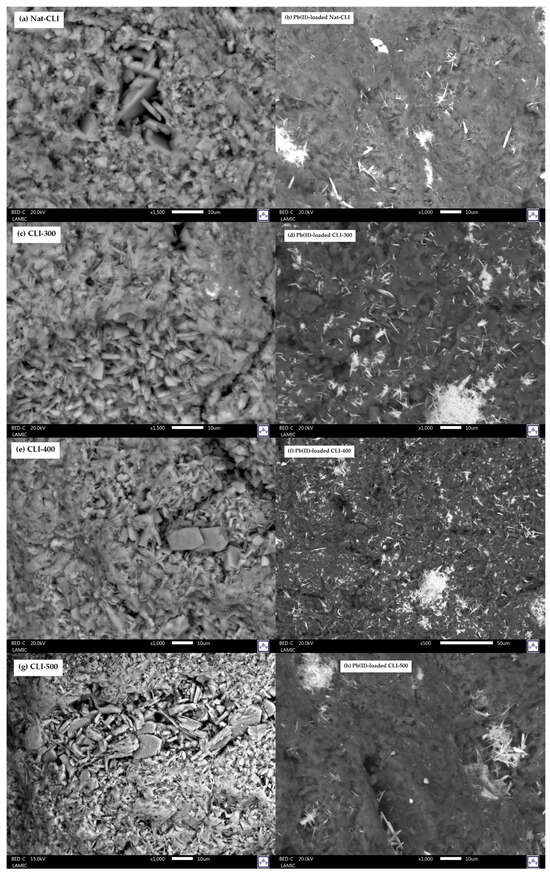

The morphological and chemical characterization of the natural clinoptilolite (Nat-CLI) and its thermally treated counterparts was carried out using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS).

Figure 2 shows comparative scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500 before and after lead (II) sorption. Micrographs of pristine zeolites (Figure 2a,c,e,g) reveal tabular, lamellar, and coffin-shaped morphologies characteristic of clinoptilolite, consistent with previous reports [29]. Only minor morphological differences were observed between the Nat-CLI and the thermally treated samples CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500, indicating that the crystallinity and structural integrity of clinoptilolite were largely preserved, confirming its thermal stability within the 300–500 °C range. After Pb(II) adsorption (Figure 2b,d,f,h), the heterogeneous distribution of bright regions, corresponding to lead, suggests that adsorption occurs preferentially at active sites on the zeolite surface, such as pores and functional groups including silanols (Si-OH) and bridging hydroxyls (Si-OH-Al).

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the zeolite samples: (a) Nat-CLI, (b) Pb(II)-loaded Nat-CLI, (c) CLI-300, (d) Pb(II)-loaded CLI-300, (e) CLI-400, (f) Pb(II)-loaded CLI-400, (g) CLI-500, and (h) Pb(II)-loaded CLI-500.

Table 2 summarizes the average chemical composition, expressed as a weight percentage, obtained by EDS from different surface regions of Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500 prior to Pb(II) sorption. The data show that the Si/Al ratio decreases with increasing heating temperature, reaching a minimum for the CLI-400 sample. This compositional modification suggests that moderate thermal activation (around 400 °C) enhances the material’s ion-exchange capacity and adsorption performance. Consequently, CLI-400 zeolite exhibits the highest Pb(II) removal efficiency, confirming its potential for environmental remediation and wastewater treatment applications.

Table 2.

Chemical composition (% weight) of Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500.

Table 3 shows the energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis results for the Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500 zeolites following Pb(II) sorption. The presence of lead on all sample surfaces indicates the effectiveness of these materials in removing this metal. However, sample CLI-400 had a higher lead concentration. This could be due to the higher Si/Al ratio of this sample (Table 2). It is important to note that EDS was used to confirm the qualitative presence of lead on the adsorbents’ surfaces after contact with the Pb(II) solution. Meanwhile, atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) was used to quantify the amount of residual metals in the solution before and after the zeolites were in contact with the Pb(II) solutions [30,31].

Table 3.

Chemical composition (wt%) of Pb(II) loaded on natural and thermally treated zeolites.

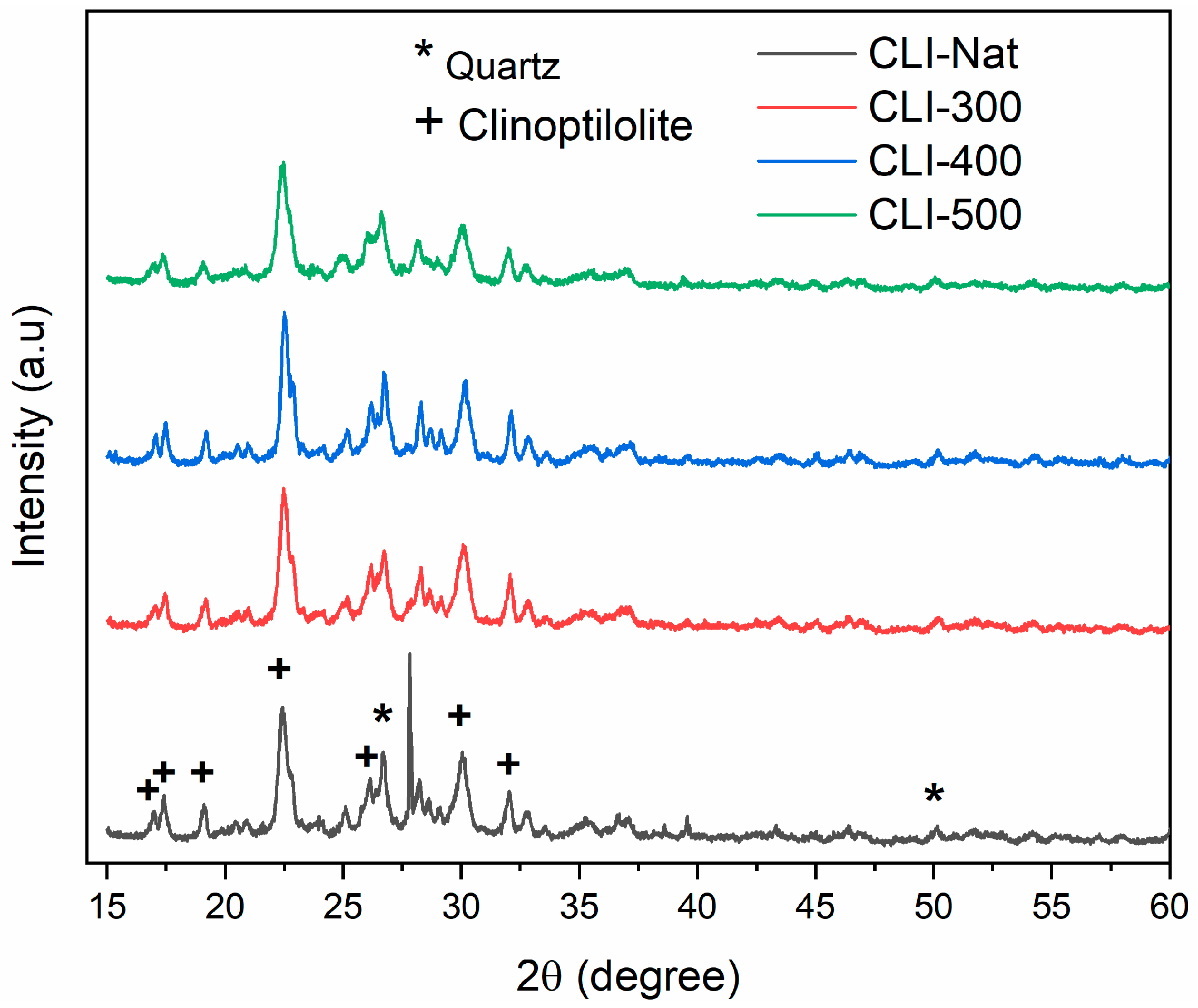

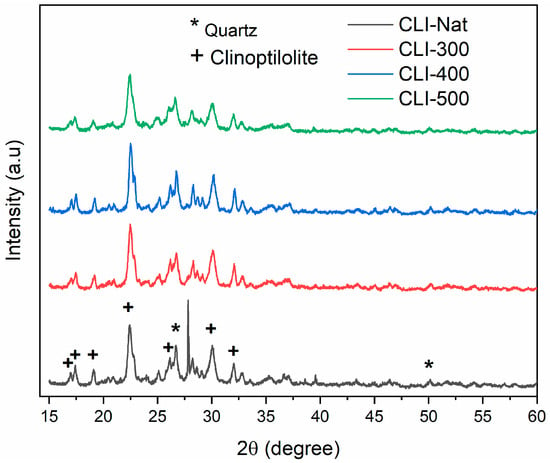

3.3. X-Ray Diffraction

Figure 3 shows the X-ray diffraction patterns of natural clinoptilolite (Nat-CLI) and its thermally treated variants (CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500). The characteristic clinoptilolite peaks, identified at 2θ = 16.88°, 17.28°, 19.01°, 22.32°, 25.92°, 29.92°, and 31.91° (JCPDS 25-1349), are present in all samples [21], Furthermore, the XRD patterns of the heated zeolites show no significant changes in peak intensity or sharpness, indicating the thermal stability of the clinoptilolite crystal structure up to 500 °C. This finding aligns with the work of Kim et al. [32], who reported that clinoptilolite retains its structure when exposed to high temperatures and acid pretreatment. This demonstrates greater thermal stability than heulandite (HEU).

Figure 3.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500.

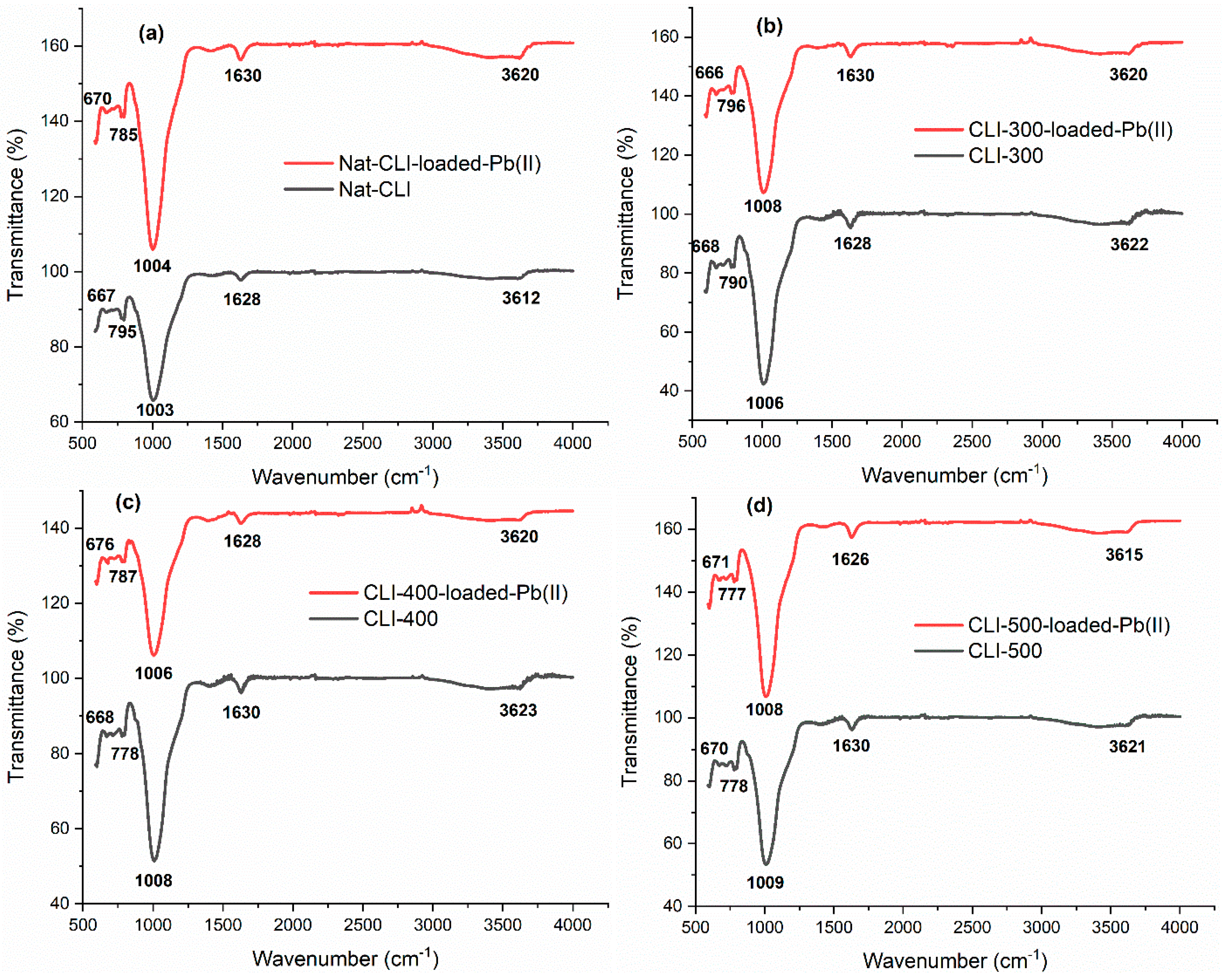

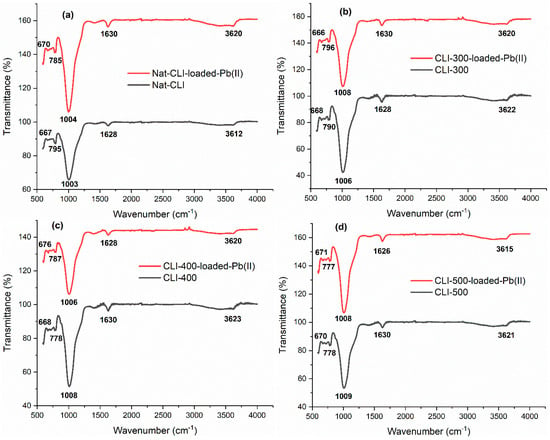

3.4. FT-IR

The FTIR spectra of natural and thermally treated clinoptilolite samples before and after Pb(II) adsorption (Figure 4a–d) provide critical insights into the structural stability and surface interactions governing the adsorption mechanism. The spectral features, characterized by well-defined vibrational bands associated with aluminosilicate frameworks, confirm that the fundamental structure of clinoptilolite remains largely preserved after Pb(II) incorporation. This stability aligns with previous studies demonstrating that zeolitic frameworks are resistant to collapse under moderate thermal activation or metal exchange [33].

Figure 4.

Fourier transformed infrared (FT-IR) spectra of (a) Nat-CLI, Nat-CLI-loaded-Pb(II), (b) CLI-300, CLI-300-loaded-Pb(II), (c) CLI-400, CLI-400-loaded-Pb(II), (d) CLI-500, CLI-500-loaded-Pb(II).

The main absorption bands, which are located between 1003 and 1009 cm−1 and are assigned to the asymmetric stretching vibrations of the T–O–T linkages (where T = Si or Al), exhibit only minor decreases in intensity after Pb(II) adsorption. This suggests that cation exchange occurs without significantly disrupting the tetrahedral TO4 framework. The slight attenuation in band intensity can be attributed to the replacement of native cations (Na+, K+, and Ca2+) with Pb2+. This substitution induces localized distortions in the bonding environment, but it does not compromise the zeolite’s structural integrity [34].

Additionally, the broad band around 3620 cm−1 and the sharper band around 1628 cm−1, which correspond to O–H stretching groups (such as Si–OH or Al–OH) and H–O–H bending vibrations of water molecules, exhibit a significant decrease in intensity in the Pb-loaded samples. This indicates the partial dehydration of the zeolite channels, which is consistent with the displacement of hydrated cations during ion exchange. Hydroxyl groups act as active sites for cation exchange and electrostatic interactions. These findings support the conclusion that Pb(II) absorption is primarily governed by ion exchange processes within the zeolite channels. Such dehydration phenomena have been widely reported in thermally or chemically activated zeolites and indicate enhanced accessibility of adsorption sites [35].

The presence of low-frequency bands at approximately 790 and 670 cm−1, which are associated with symmetric stretching and ring-opening vibrations, respectively, further supports the structural integrity of the clinoptilolite framework. The presence of these bands in both pristine and Pb-loaded samples suggests that framework degradation does not occur upon adsorption. Notably, the absence of new absorption bands in the low-frequency region (550–500 cm−1) and of hydroxyl stretching signals (3700–3550 cm−1) suggests that Pb(II) uptake primarily occurs via ion exchange rather than surface complexation [34].

Taken together, these findings confirm that moderate thermal treatment (up to 400 °C) preserves the crystalline framework and increases the density of active sites by inducing controlled dehydration. Thus, the spectroscopic evidence corroborates the adsorption data, highlighting that the removal of Pb(II) from an aqueous solution is primarily governed by cation exchange within the zeolitic channels rather than by chemical bonding at the external surface.

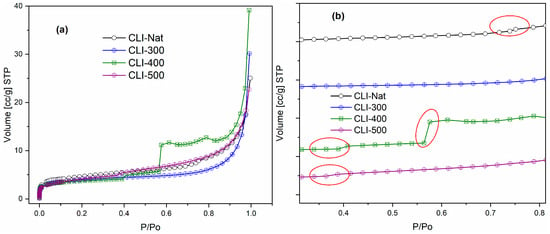

3.5. BET

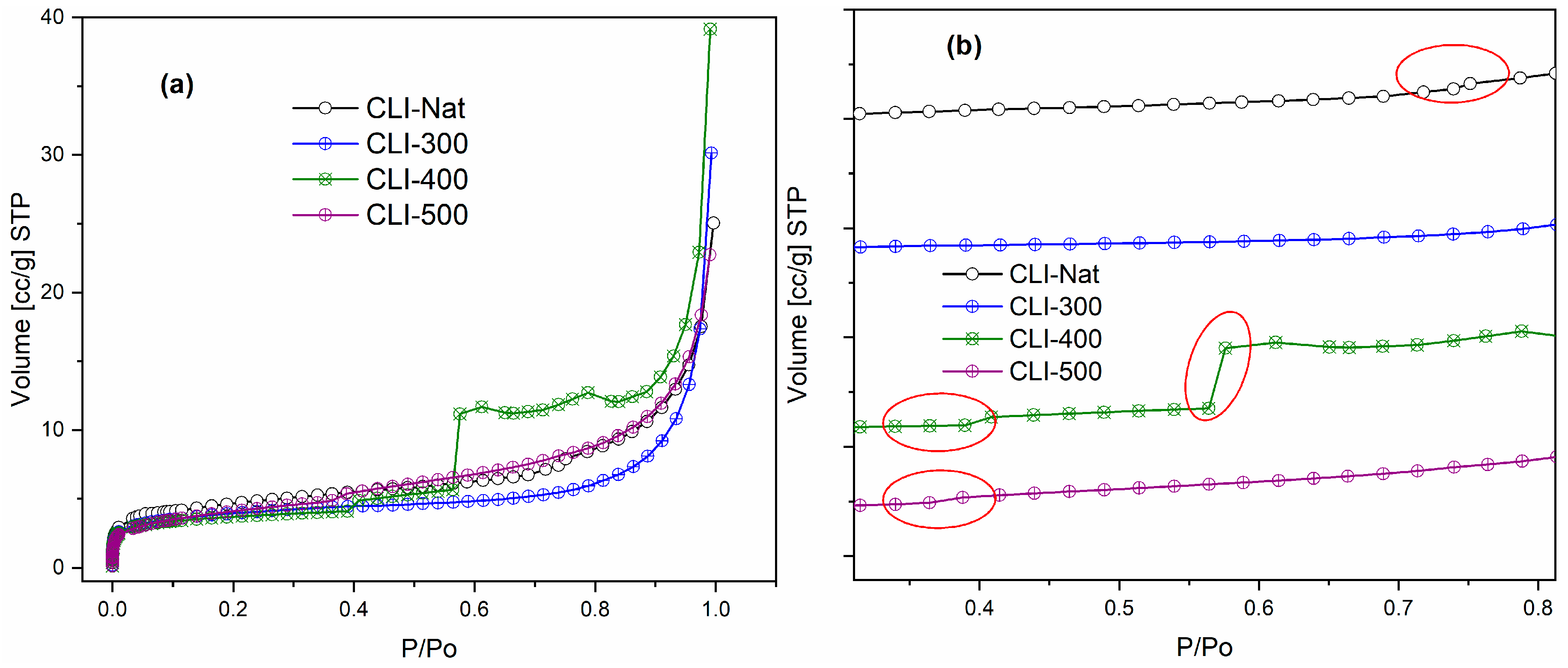

Figure 5a shows the nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms for the four samples, which were measured at 76 K. Within the low relative pressure range (0 to 0.4), the adsorption isotherms are very similar across all samples, exhibiting characteristics indicative of monolayer adsorption and micropore filling. However, a gradual increase in adsorbed volume is observed at higher relative pressures, attributed to multilayer adsorption in mesopores. The divergence in the isotherms within this region indicates that adsorption behavior is strongly influenced by thermal treatment temperature. The most notable differences are observed in the CLI-400 sample. All samples exhibit Type I adsorption isotherms that are largely similar, except for CLI-400. The isotherms are irreversible and display nearly identical hysteresis cycles. However, the samples exhibit distinct variations in adsorption and desorption behavior. These differences suggest that the thermal treatment temperature significantly influences the process in addition to relative pressure. The observed differences are likely due to heat-induced changes in composition that concentrate a non-zeolitic phase with distinct adsorption properties. For example, the isotherm for natural zeolite (Nat-CLI) shows sharp uptake at a relative pressure of about 0.7, while CLI-500 shows a similar increase at around 0.4. Notable differences are observed in the isotherms, particularly for CLI-400. CLI-400 exhibits an initial uptake similar to that of CLI-500, followed by a more substantial increase near a relative pressure of 0.6. In contrast, CLI-300 shows only a gradual increase in the high-pressure region, which is consistent with multilayer adsorption. Subtle variations in adsorbate volume across the samples, as shown in Figure 5b, suggest the presence of a minor impurity within the zeolite framework. The general similarity of the isotherms, with the exception of CLI-400, suggests that this impurity is minor. Nevertheless, its influence is significant; the distinct adsorption behavior and hysteresis of CLI-400 imply that heat treatment causes a redistribution or stabilization of this phase. The increased adsorbate volume for CLI-400 may be related to the migration of these impurities to the external surface, which alters the porosity and creates new adsorption sites.

Figure 5.

Nitrogen (N2) adsorption and desorption isotherm curves within (a) 0 to 1.0 and (b) between 0.4 to 0.8 relative pressure ranges for Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400 and CLI-500 at 76 K.

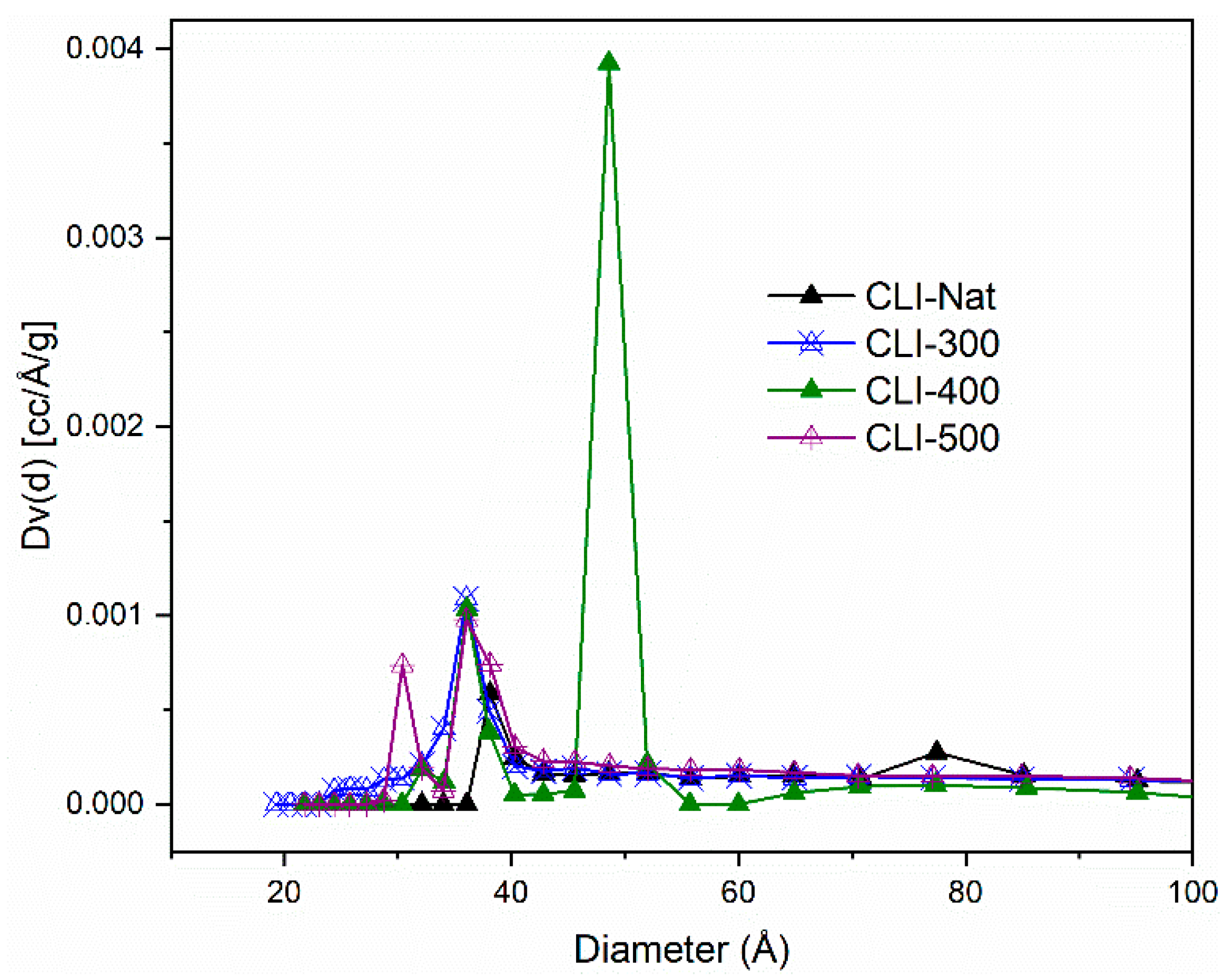

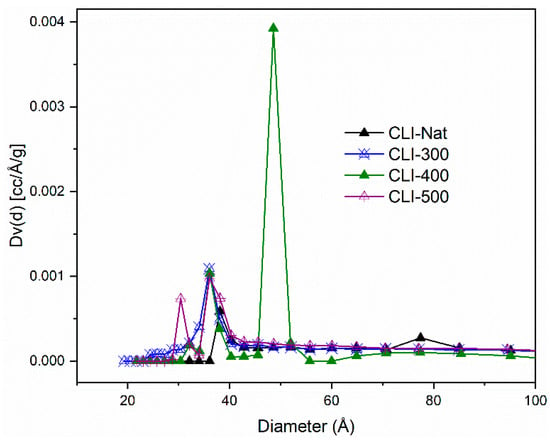

Figure 6 shows that the pore size distributions suggest thermal treatment displaces impurities, clogging the larger mesopores (around 80 Å) in natural clinoptilolite (Nat-CLI). This effect is evident when comparing the Nat-CLI and CLI-300 samples. The clogging results in a reduction in the specific surface area, total pore volume, and mesopore size. Consequently, as the population of mesopores narrows, the CLI-300 adsorption isotherm more closely resembles a Type I isotherm. The quantitative values for these textural properties are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 6.

Pore size distribution calculated by BJH method, for Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400 and CLI-500.

Table 4.

Textural properties of natural and thermally treated zeolites.

The textural properties of the samples were quantified by applying the standard BET method for specific surface area and the BJH method for pore size distribution. The resulting values for the specific surface area, total pore volume, and average pore size are summarized in Table 4.

Where

SBET is the surface area calculated by the BET method. CBET is the BET constant.

SL is the surface area calculated by the Langmuir method, and KL is the Langmuir constant.

SMIC and SEXT are the surface areas of the micropores and mesopores, respectively, calculated by the T-graph method, and the sum equals SBET.

VTP is the total pore volume at a relative pressure of ~0.98.

DPP is the average pore diameter.

DBJH: pore diameter calculated by the BJH method.

DDFT: pore diameter calculated by the DFT method.

The DBJH and DDFT values correspond to the maximum values of the main pore populations. The most significant changes occur when Nat-CLI is heated to 400 °C. The increased gas uptake, particularly at a relative pressure of 0.6, is likely due to the reorganization of impurities. This process generates a new population of mesopores and reduces the hysteresis cycle. However, when heated to 500 °C, some of these impurities appear to volatilize. Consequently, the adsorption–desorption isotherms and hysteresis of CLI-500 closely resemble those of the original Nat-CLI. A small uptake near a relative pressure of 0.4 is attributed to a marginal amount of remaining impurity. Based on this evidence, it can be inferred that the impurity in the natural zeolite (Nat-CLI) is initially dispersed more or less uniformly across the external surface.

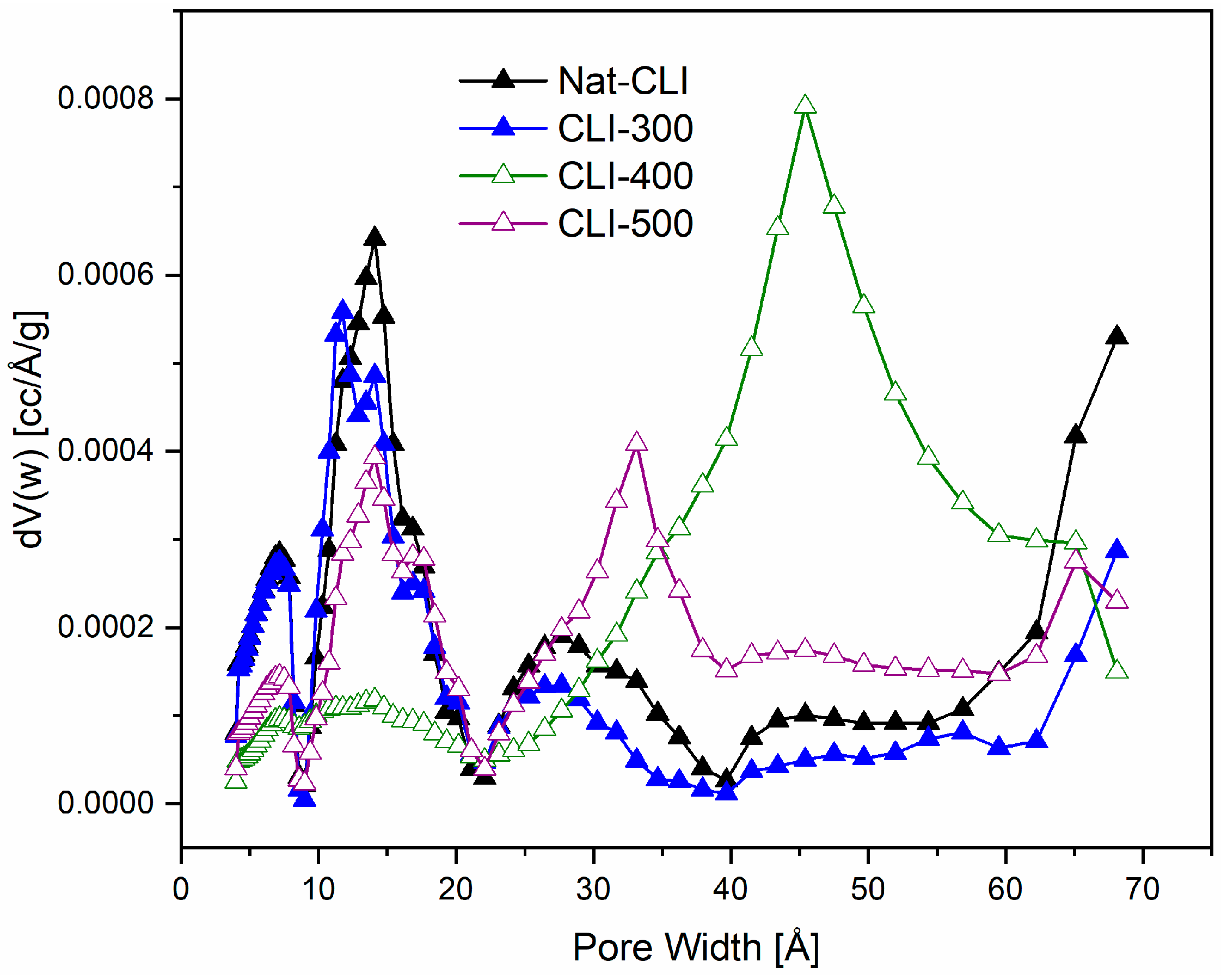

Figure 7 shows the pore size distributions calculated using the DFT method. The results are consistent with those obtained from the BJH method regarding the mesopore populations. This confirms that nitrogen adsorption in these samples occurs through monolayer and multilayer formation on solid surfaces. All samples exhibit a Type I isotherm, consistent with their larger micropore volume compared to mesopore volume. The CLI-400 sample is the exception to this trend.

Figure 7.

Comparison of DFT pore size distributions, for the Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400 and CLI-500 samples.

Effective strategies have been developed to enhance the surface area, mesoporous structure, and Si/Al ratio of zeolites while maintaining their crystalline integrity. These strategies include acid dealumination, alkaline desilication, and combined thermal activation followed by acid leaching. Akyalcin et al. (2024) used 1 M HCl, which increased the BET surface area from 46 to 309 m2 g−1 [36]. Agudelo et al. (2015) found that applying acid leaching after thermal treatment further enhanced the textural properties, achieving BET surface areas of 737, 710, and 630 m2/g for samples treated at 500, 600, and 700 °C, respectively [37].

Overall, these findings confirm that controlled thermochemical modifications effectively optimize the balance between structural stability and surface accessibility. These methods are thus established as sustainable, efficient strategies for improving the performance of natural clinoptilolite in applications such as heavy metal removal and heterogeneous catalysis.

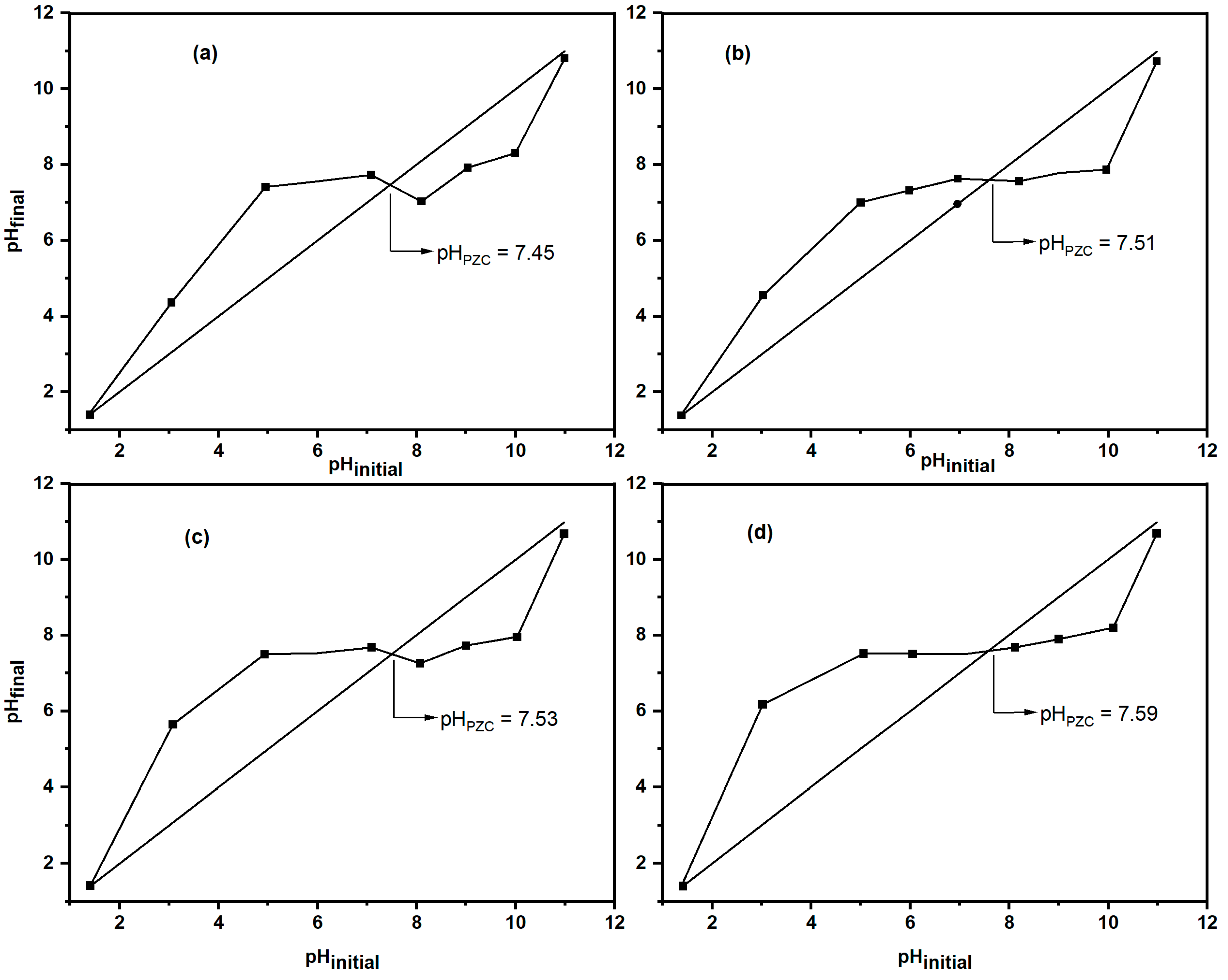

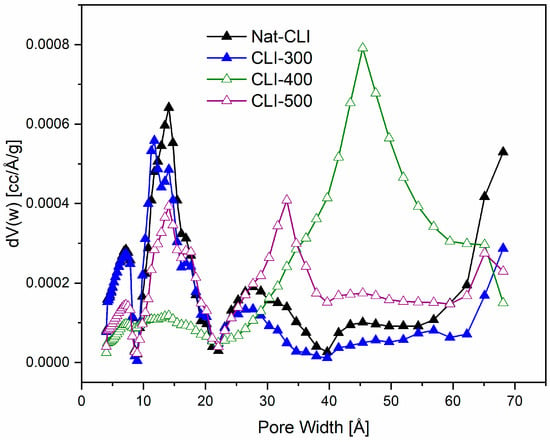

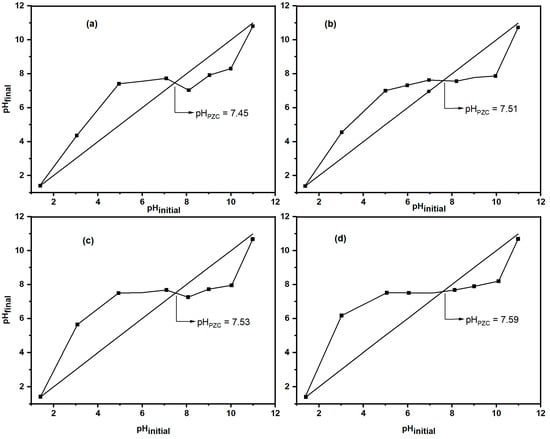

3.6. pHpzc

The point of zero charge (pHpzc) is the pH at which the net surface charge of an adsorbent is zero [38]. Above the pHpzc, the surface is negatively charged; below it, the surface is positively charged. Figure 8 shows that the pHpzc values are 7.45 for Nat-CLI, 7.51 for CLI-300, 7.53 for CLI-400, and 7.59 for CLI-500. The surface charge is positive below the pHpzc and negative above it. Figure 8 shows the pHpzc values: 7.45 for Nat-CLI, 7.51 for CLI-300, 7.53 for CLI-400, and 7.59 for CLI-500. Following thermal treatment at 300 °C, the pHpzc value increased from 7.45 for natural zeolite to 7.51. Increasing the temperature to 400 °C (CLI-400) resulted in a slight increase to 7.53. The highest pHpzc value, 7.59, was observed for the sample treated at 500 °C (CLI-500). Overall, there is a slight but consistent trend of increasing pHpzc with higher treatment temperatures. This behavior is consistent with the findings of Psaltou et al. [39] for raw and thermally treated clinoptilolite. The increase in pHpzc is due to dehydroxylation, which alters the surface chemistry. This process involves the removal of hydroxyl groups, which affects the formation of surface charges originating from the hydrolysis of metal oxides and the formation of metal hydrolytic complexes [40]. Despite these changes, the pHpzc of natural zeolite (Nat-CLI) increased by only 0.14 units after treatment at 500 °C (CLI-500), suggesting that thermal treatment only slightly influences the overall surface charge.

Figure 8.

pHpzc of (a) Nat-CLI, (b) CLI-300, (c) CLI-400 and (d) CLI-500.

3.7. Sorption Study

3.7.1. Kinetic Study

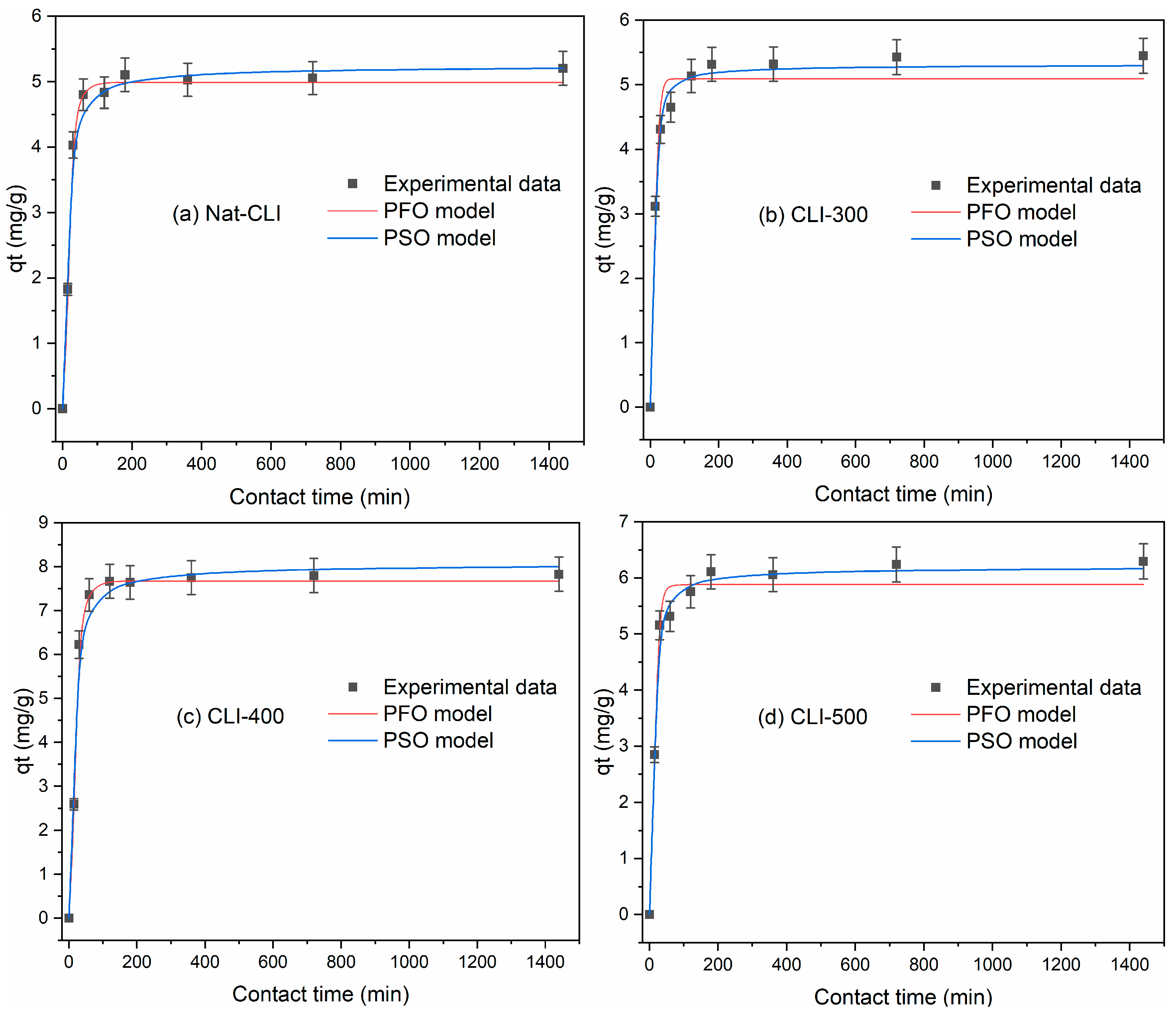

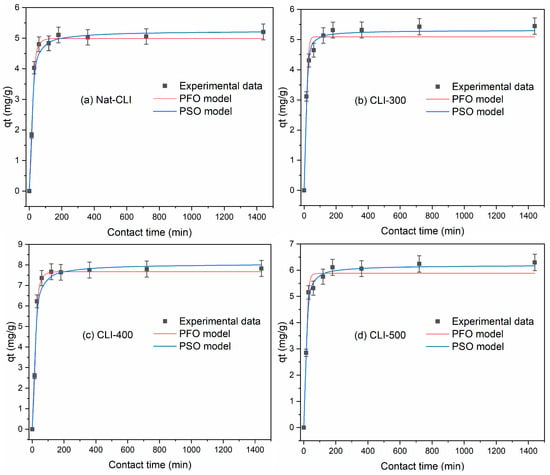

Figure 9a–d illustrate the adsorption kinetics of Pb(II) onto Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500. As shown in these figures, all of the adsorbents exhibited rapid adsorption during the first 60 min and reached equilibrium after approximately 120 min. The maximum adsorption capacities were approximately 5.203, 5.449, 7.831, and 6.297 mg/g, respectively, for Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500. As observed, qt values were consistently higher for the CLI-400, confirming the beneficial effect of thermal modification on metal adsorption performance.

Figure 9.

Effect of contact time on the adsorption of Pb(II) onto (a) Nat-CLI, (b) CLI-300, (c) CLI-400, and (d) CLI-500.

The pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) models are applied to the adsorption of Pb(II) onto Nat-CLI, CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500. The calculated parameters (qe,cal, k1, k2, R2, SSE, χ2, and RMSE) are presented in Table 5. As evidenced by higher R2 (0.951–0.991) and lower SSE (0.192–0.631), χ2 (0.045–0.142), and RMSE (0.454–1.435), the PSO model demonstrated the best agreement with the experimental data for all adsorbents. The correlation coefficients for the PFO model range from 0.836 to 0.985. However, the SSE, χ2, and RMSE values obtained with the PFO model are higher than those obtained with the PSO model. These results support the assumption that the rate-controlling step involves a chemisorption process governed by valence interactions between the metal ions and surface functional groups [41].

Table 5.

Kinetic parameters of Pb(II) adsorption onto (a) Nat-CLI, (b) CLI-300, (c) CLI-400, and (d) CLI-500 fitted to pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models.

3.7.2. Isotherm Study

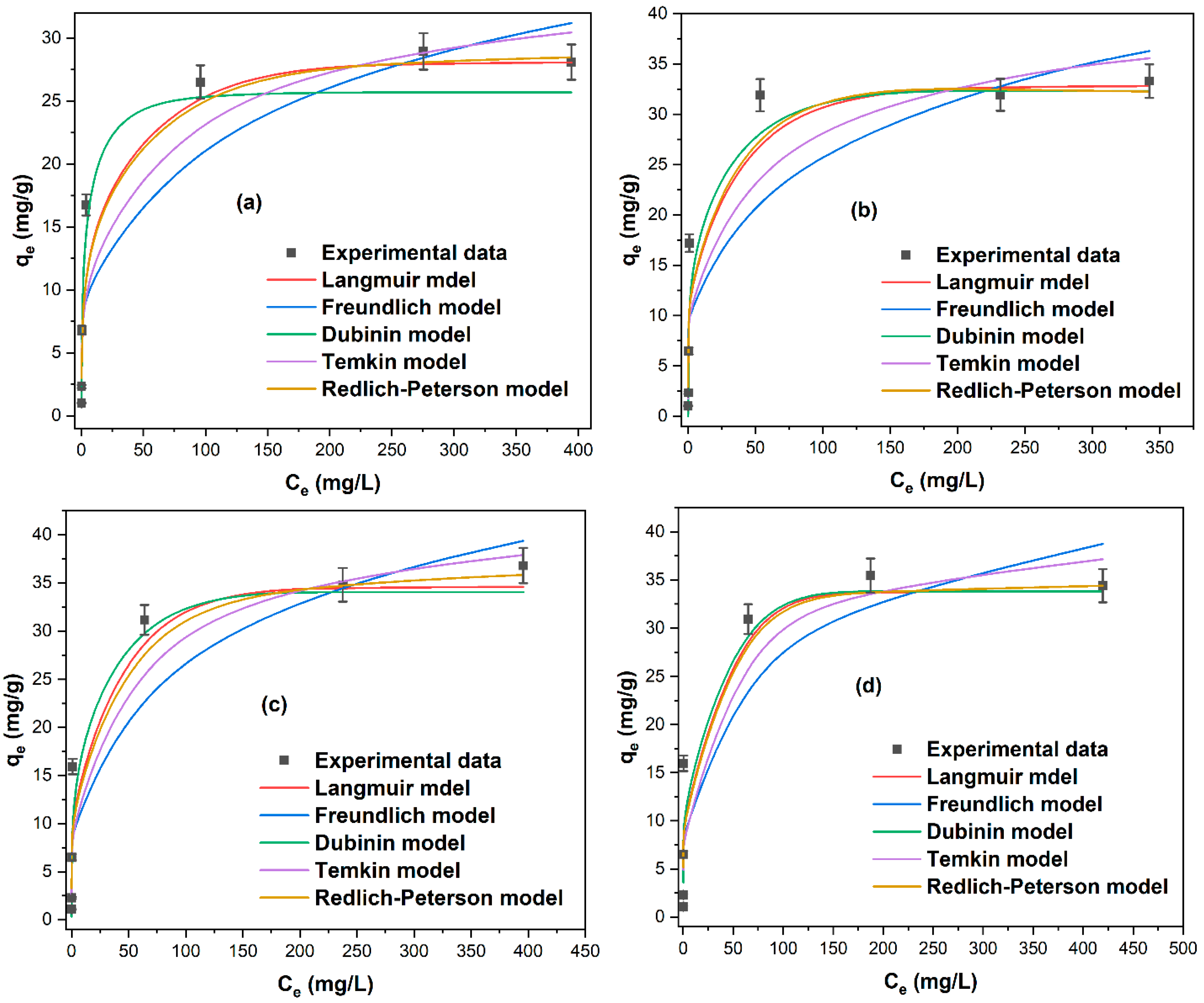

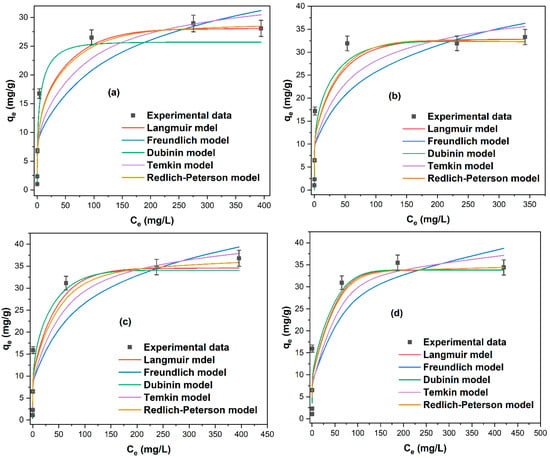

The sorption behavior of Pb(II) onto natural and thermally treated zeolites was evaluated using nonlinear Langmuir, Freundlich, Dubinin–Radushkevich, Temkin, and Redlich–Peterson models (Figure 10). For the natural zeolite (Figure 10a), the Langmuir and Redlich–Peterson models provided the best fit. This is consistent with previous reports indicating that Pb(II) adsorption onto natural clinoptilolite predominantly follows monolayer behavior with slight surface heterogeneity [42].

Figure 10.

Nonlinear fitting of Langmuir, Freundlich, Dubinin–Radushkevich, Temkin, and Redlich–Peterson isotherm models for Pb(II) adsorption onto (a) natural (Nat-CLI) and thermally treated zeolites at (b) 300 °C (CLI-300), (c) 400 °C (CLI-400), and (d) 500 °C (CLI-500).

After thermal activation, all of the treated samples (CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500; see Figure 10b–d) showed improved agreement with the Dubinin–Radushkevich model. This was followed by agreement with the Langmuir and Redlich–Peterson isotherms. This shift indicates that heating alters surface energetics and site distribution. This leads to adsorption governed by physical forces acting on microporous heterogeneous surfaces. The suitability of multiple models suggests that Pb(II) uptake involves more than one interaction mechanism [43].

Table 6 summarizes the isotherm parameters and the statistical indicators: correlation coefficient (R2), sum of squares error (SSE), chi-squared (χ2), and root mean square error (RMSE). These indicators are used to evaluate the deviation between the experimental and model-predicted values. The adsorption of Pb(II) onto natural clinoptilolite (Nat-CLI) was adequately described by the Langmuir, Temkin, and Redlich–Peterson models, all of which yielded R2 values greater than 0.950. The Redlich–Peterson isotherm exhibited the best fit among these models, showing the highest R2 value (0.989) and the lowest SSE (10.46) and RMSE (1.446). The Redlich–Peterson model is considered suitable because it can represent adsorption processes involving both monolayer and multilayer interactions [30].

Table 6.

Isotherm parameters from nonlinear regression for the adsorption of Pb(II) onto natural and thermally treated zeolites.

The close agreement between the maximum experimental adsorption capacity (Qm,exp) and the calculated (Qm,cal) values, as well as the β parameter value near 1 (Table 6), suggests that the adsorption behavior follows the Langmuir isotherm model. This is consistent with the Langmuir model being the second-best fit, as indicated by its high R2 value of 0.988 and low error values of SSE = 11.22 and RMSE = 1.498. The Langmuir model describes homogeneous monolayer adsorption on a surface with a finite number of identical sites, but it does not account for interactions between adsorbed molecules [30]. The Temkin isotherm also showed a good fit, with an R2 of 0.967, χ2 of 7.716, and RMSE of 2.465. This model has previously been reported for the adsorption of Pb(II) onto natural clinoptilolite [41].

However, the Pb(II) adsorption mechanism changed after thermal treatment at 300 °C (CLI-300), as indicated by a shift in the best-fitting isotherm models. Based on the highest R2 values and lowest error values, the order of fit for CLI-300 was as follows: Dubinin–Radushkevich > Redlich–Peterson > Langmuir. The same trend was observed for zeolites treated at 400 and 500 °C (CLI-400 and CLI-500), suggesting that the Dubinin–Radushkevich model best describes the adsorption isotherm of thermally treated zeolites.

Table 6 shows the mean free energy of adsorption (E) for CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500, which are 1.394, 1.831, and 2.933 kJ/mol, respectively. According to the literature [44], an E value below 8 kJ/mol indicates a physical adsorption mechanism. Therefore, the calculated E values suggest that physical forces primarily govern the adsorption of Pb(II) onto the thermally treated zeolites. The good fit with both the Langmuir and Redlich–Peterson isotherm models further supports a complex adsorption process. This is consistent with a system in which physical adsorption is dominant, though it does not preclude contributions from chemical interactions. Table 6 also presents the parameters for each fitted isotherm model. The maximum adsorption capacity (Qₘ), calculated from the Langmuir model, increased after thermal treatment from 28.26 mg/g for Nat-CLI to 32.96, 34.69, and 33.85 mg/g for CLI-300, CLI-400, and CLI-500, respectively. A similar trend was observed for the Qm values derived from the Dubinin–Radushkevich model, which increased from 25.69 mg/g for Nat-CLI to 32.33, 34.03, and 33.82 mg/g for the thermally treated samples, respectively. The rise in the pHPZC of the zeolites following thermal treatment can explain this overall increase in Pb(II) adsorption capacity. The pHPZC changed from 7.45 (Nat-CLI) to 7.51 (CLI-300), 7.53 (CLI-400), and 7.59 (CLI-500).

Therefore, thermal treatment of the zeolites enhances their physical interaction with Pb(II). CLI-400 exhibited the highest adsorption capacity and the lowest Si/Al ratio of 4.5 (Table 2). According to Puspitasari et al., [35], a lower Si/Al ratio corresponds to a higher negative charge on the zeolite framework, increasing its capacity to adsorb cationic species like Pb(II). The lowest Qm values (28.26 mg/g using the Langmuir method and 25.69 mg/g using the Dubinin–Radushkevich method) were observed for natural zeolite (Nat-CLI), which has a higher Si/Al ratio of 4.79 compared to 4.5 for CLI-400, further supporting this correlation.

Table 7 compares the maximum adsorption capacity (Qm) and the percentage of Pb(II) removed from natural and modified clinoptilolites via thermal or chemical treatments. The data clearly show that these modifications substantially improve the overall adsorption performance. The CLI-400 sample, with a Qm of 34.69 mg/g, is comparable to systems modified with acid or alkali. These results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed thermal activation method [38,44,45].

Table 7.

Comparison of the Pb(II) adsorption capacity of natural and modified clinoptilolite-based materials.

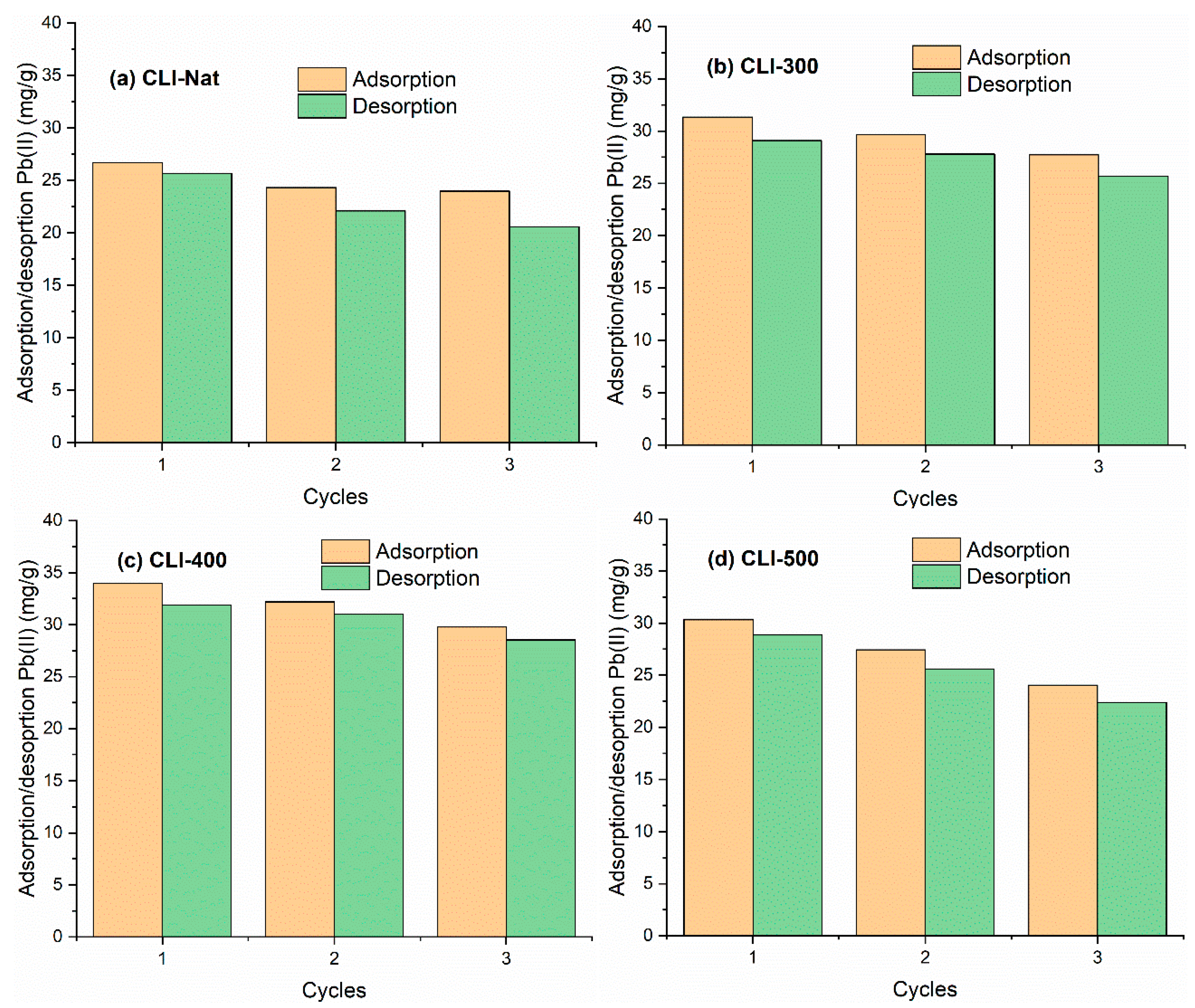

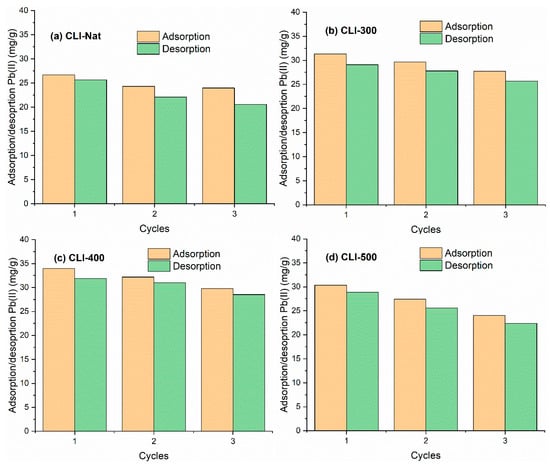

3.8. Adsorption/Desorption Cycles

The reusability of natural and heat-treated clinoptilolite was evaluated using three consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles (Figure 11a–d). Although a slight but progressive decrease in Pb(II) adsorption capacity was observed across cycles, all samples maintained sufficient removal efficiency. These results are consistent with previous findings that lead (Pb(II)) can be effectively recovered via ion exchange in saline or acidic media while maintaining the structural stability of the adsorbent [51]. The reduction in clinoptilolite’s adsorption capacity during repeated cycles is due to incomplete desorption of Pb(II) [52], which is caused by the zeolite surface’s strong chemical bonding with metal ions [53]. This leads to a loss of active sites on the adsorbent surface after desorption. Another possible reason is the partial degradation of the zeolite framework’s structure when HCl is used as the desorption reagent [54]. The thermally treated clinoptilolite, particularly the CLI-400 sample, maintained a high adsorption capacity following multiple regeneration cycles. This confirms its strong potential for reuse.

Figure 11.

Adsorption and desorption capacity of Pb(II) after three progressive cycles onto (a) NAT-CLI, (b) CLI-300, (c) CLI-400, and (d) CLI-500.

4. Conclusions

Analyses using FTIR, XRD, and TGA confirm that the crystalline framework of natural clinoptilolite remains stable after thermal treatment at 300, 400, and 500 °C. Minor variations in pHPZC and the Si/Al ratio reflect surface dehydroxylation and slight compositional adjustments. The sample treated at 400 °C (CLI-400) exhibited the highest surface area, total pore volume, and maximum Pb(II) adsorption capacity (34.69 mg/g). This demonstrates that moderate calcination increases the density of active sites while preserving the structural integrity of the framework. These results confirm that moderate thermal activation is a green, cost-effective, and efficient strategy for removing Pb(II) from wastewater. This positions thermally treated natural clinoptilolite as a sustainable alternative to synthetic or chemically functionalized adsorbents.

Equilibrium data suggest that the adsorption of Pb(II) onto thermally treated zeolites involves a combination of physical, chemical, and electrostatic mechanisms. Regeneration experiments showed that clinoptilolite can be efficiently reused through desorption with mild acid solutions and maintain a high adsorption capacity after three consecutive adsorption/desorption cycles. Regenerating and reusing the material reduces operational expenses and minimizes environmental impact, which reinforces the sustainability advantages of thermally treated clinoptilolite for Pb(II) remediation.

To further enhance adsorption efficiency, it is recommended that a combined thermal and chemical modification be used, such as acid dealumination or controlled alkaline desilication after calcination. This approach has been shown to effectively increase mesoporosity and surface area while preserving crystallinity. Integrating these methods can lead to the development of hierarchical zeolites with superior textural and adsorption properties. This expands their potential for environmental remediation and sustainable catalytic applications. Additionally, future studies are encouraged to evaluate the scalability of this activation process, its performance in systems contaminated with multiple metals, and its long-term regeneration capacity under continuous flow conditions.

Author Contributions

A.Q. and M.A. designed the experiments. M.A., F.A.-F. and C.A.U. contributed to characterizing the samples and interpreting the results. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Orlando Hernández Cristobal for his valuable support with the SEM and FTIR analyses of the adsorbents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mumtaz, F.; Irfan, M.F.; Usman, M.R. Synthesis methods and recent advances in hierarchical zeolites: A brief review. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2021, 18, 2215–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadar, O.; Senila, M.; Hoaghia, M.A.; Scurtu, D.; Miu, I.; Levei, E.A. Effects of thermal treatment on natural clinoptilolite-rich zeolite behavior in simulated biological fluids. Molecules 2020, 25, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Shang, R.; Heijman, S.G.J.; Rietveld, L.C. Adsorption of triclosan, trichlorophenol and phenol by high-silica zeolites: Adsorption efficiencies and mechanisms. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 235, 116152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Shang, R.; Heijman, S.G.J.; Rietveld, L.C. High-silica zeolites for adsorption of organic micro-pollutants in water treatment: A review. Water Res. 2018, 144, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Botella, E.; Valencia, S.; Rey, F. Zeolites in Adsorption Processes: State of the Art and Future Prospects. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 17647–17695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Y.W.; Wong, K.L.; Ooi, B.S.; Ling, T.C.; Khoerunnisa, F.; Ng, E.P. Effects of synthesis parameters on crystallization behavior of K-MER zeolite and its morphological properties on catalytic cyanoethylation reaction. Crystals 2020, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordala, N.; Wyszkowski, M. Zeolite Properties, Methods of Synthesis, and Selected Applications. Molecules 2024, 29, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wang, H.; Dong, Q.; Li, Y.; Xiang, H. A Review on the Research Progress of Zeolite Catalysts for Heavy Oil Cracking. Catalysts 2025, 15, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowska, M.; Chmielarz, L. Application of Mesoporous/Hierarchical Zeolites as Catalysts for the Conversion of Nitrogen Pollutants: A Review. Catalysts 2024, 14, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmanzadegan, F.; Ghaemi, A. A comprehensive review on novel zeolite-based adsorbents for environmental pollutant. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 17, 100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, M. Recent Trends in Synthesis and Applications of Zeolite Membranes+1. Mater. Trans. 2024, 65, 1218–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senila, M.; Kovacs, E.; Senila, L. Silver-Exchanged Zeolites: Preparation and Applications—A Review. Materials 2025, 18, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshanfekr Rad, L.; Anbia, M. Zeolite-based composites for the adsorption of toxic matters from water: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senila, M.; Cadar, O. Modification of natural zeolites and their applications for heavy metal removal from polluted environments: Challenges, recent advances, and perspectives. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behfrouz, A.; Tahmasebpoor, M. Modification of clinoptilolite zeolite adsorbent from Miyaneh mines to remove ammonia from the water environment. Environ. Water Eng. 2025, 11, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyitno; Rosyadi, I.; Arifin, Z.; Sutardi, T.; Sunaryo; Ilminnafik, N. Advanced modification of natural zeolites for optimized biogas, syngas, and hydrogen production and purification. Cogent Eng. 2024, 11, 2398912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.G.; Kemp, K.C.; Kencana, K.S.; Hong, S.B. Silver-exchanged CHA zeolite as a CO2-resistant adsorbent for N2/O2 separation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 323, 111239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.M.; Karanikolos, G.N. CO2 capture adsorbents functionalized by amine—Bearing polymers: A review. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2020, 96, 103005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’connor, C.T.; Möller, K.P.; Manstein, H. The effect of silanization on the catalytic and sorption properties of zeolites. CATTECH 2001, 5, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukobat, R.; Škrbić, R.; Massiani, P.; Baghdad, K.; Launay, F.; Sarno, M.; Cirillo, C.; Senatore, A.; Salčin, E.; Atlagić, S.G. Thermal and structural stability of microporous natural clinoptilolite zeolite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 341, 112101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, E.B. Investigating the Chemical and Thermal Based Treatment Procedures on the Clinoptilolite to Improve the Physicochemical Properties. J. Turk. Chem. Soc. Sect. B Chem. Eng. 2022, 5, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Jabłońska, B. Optimization of ni(Ii), pb(ii), and zn(ii) ion adsorption conditions on pliocene clays from post-mining waste. Minerals 2021, 11, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Liang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, W. Method Selection for Analyzing the Mesopore Structure of Shale—Using a Combination of Multifractal Theory and Low-Pressure Gas Adsorption. Energies 2023, 16, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, A.; Hardacre, C. The effect of various treatment conditions on natural zeolites: Ion exchange, acidic, thermal and steam treatments. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 372, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M.; Dechnik, J.; Szymczak, P.; Handke, B.; Szumera, M.; Stoch, P. Thermal Behavior of Clinoptilolite. Crystals 2024, 14, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaria, S.; Mamontova, E.; Guari, Y.; Larionova, J.; Long, J.; Trens, P.; Salles, F.; Zajac, J. Heat release kinetics upon water vapor sorption using cation-exchanged zeolites and prussian blue analogues as adsorbents: Application to short-term low-temperature thermochemical storage of energy. Energies 2021, 14, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burris, L.E.; Juenger, M.C.G. Effect of calcination on the reactivity of natural clinoptilolite zeolites used as supplementary cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 258, 119988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatal, M.; Quiroz, A.V.C.; Olguín, M.T.; Vázquez-Olmos, A.R.; Vargas, J.; Anguebes-Franseschi, F.; Giácoman-Vallejos, G. Sorption of Pb(II) from aqueous solutions by acid-modified clinoptilolite-rich tuffs with different Si/Al ratios. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-García, S.; Ramírez-García, J.J.; Granados-Correa, F.; Sánchez-Meza, J.C. Structural and textural influences of surfactant-modified zeolitic materials over the methamidophos adsorption behavior. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, I.V.; Tosheva, L.; Miller, G.; Doyle, A.M. Fau—Type zeolite synthesis from clays and its use for the simultaneous adsorption of five divalent metals from aqueous solutions. Materials 2021, 14, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasiri-Ardali, M.; Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A. A comprehensive study on the kinetics and thermodynamic aspects of batch and column removal of Pb(II) by the clinoptilolite–glycine adsorbent. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 240, 122142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Hwang, U.-C.; Nam, I.-S.; Kim, Y.G. The characteristics of a copper-exchanged natural zeolite for NO reduction by NH3 and C3H6. Catal. Today 1998, 44, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zendelska, A.; Golomeova, M.; Jakupi, S.; Lisichkov, K.; Kuvendziev, S.; Marinkovski, M. Characterization and Application of Clinoptilolite for Removal of Heavy Metal Ions from Water Resources. Geol. Maced. 2018, 32, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Król, M.; Koleżyński, A.; Mozgawa, W. Vibrational spectra of zeolite y as a function of ion exchange. Molecules 2021, 26, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspitasari, T.; Ilmi, M.M.; Nurdini, N.; Mukti, R.R.; Radiman, C.L.; Darwis, D.; Kadja, G.T.M. The physicochemical characteristics of natural zeolites governing the adsorption of Pb2+ from aqueous environment. Key Eng. Mater. 2019, 811, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyalcin, S.; Akyalcin, L.; Ertugrul, E. Modification of natural clinoptilolite zeolite to enhance its hydrogen adsorption capacity. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2024, 50, 1455–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo, J.L.; Hensen, E.J.M.; Giraldo, S.A.; Hoyos, L.J. Influence of steam-calcination and acid leaching treatment on the VGO hydrocracking performance of faujasite zeolite. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 133, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Desouky, M.G.; El-Bindary, M.A.; El-Bindary, A.A. Effective adsorptive removal of anionic dyes from aqueous solution. Vietnam J. Chem. 2021, 59, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psaltou, S.; Kaprara, E.; Kalaitzidou, K.; Mitrakas, M.; Zouboulis, A. The effect of thermal treatment on the physicochemical properties of minerals applied to heterogeneous catalytic ozonation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, G.A. The isoelectric points of solid oxides, solid hydroxides, and aqueous hydroxo complex systems. Chem. Rev. 1965, 65, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetanova, L.; Barbov, B.; Rusew, R.; Delcheva, Z.; Shivachev, B. Equilibrium Isotherms and Kinetic Effects during the Adsorption of Pb(II) on Titanosilicates Compared with Natural Zeolite Clinoptilolite. Water 2022, 14, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günay, A.; Arslankaya, E.; Tosun, I. Lead removal from aqueous solution by natural and pretreated clinoptilolite: Adsorption equilibrium and kinetics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 146, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakhaei, M.; Mokhtari, H.R.; Vatanpour, V.; Rezaei, K. Investigating the Effectiveness of Natural Zeolite (Clinoptilolite) for the Removal of Lead, Cadmium, and Cobalt Heavy Metals in the Western Parts of Iran’s Varamin Aquifer. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anari-Anaraki, M.; Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A. Modification of an Iranian clinoptilolite nano-particles by hexadecyltrimethyl ammonium cationic surfactant and dithizone for removal of Pb(II) from aqueous solution. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 440, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, R.; Zhang, J.; Zou, W.; Shi, J.; Liu, H. Equilibrium biosorption isotherm for lead ion on chaff. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005, 125, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglezakis, V.J.; Stylianou, M.A.; Gkantzou, D.; Loizidou, M.D. Removal of Pb(II) from aqueous solutions by using clinoptilolite and bentonite as adsorbents. Desalination 2007, 210, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewská, E.; Tylus, W.; Bujdoš, M. Study of mono- and bimetallic fe and mn oxide-supported clinoptilolite for improved pb(Ii) removal. Molecules 2021, 26, 4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Adsorption of Zn(II), Pb(II), and Cu(II) by Residual Soil-Derived Zeolite in Single-Component and Competitive Systems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepova, K.; Konanets, R. Clinoptilolite- and Glauconite-Based Sorbents for Lead Removal from Natural Waters. J. Environ. Eng. Landsc. Manag. 2024, 32, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Avendaño, Y.S.; Hernández, N.C.; Ruiz-Salvador, A.R.; Abatal, M. Further Insight in the High Selectivity of Pb2+ Removal over Cd2+ in Natural and Dealuminated Rich-Clinoptilolite. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doula, M.K.; Ioannou, A. The effect of electrolyte anion on Cu adsorption-desorption by clinoptilolite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2003, 58, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratti, L.M.; Reis, G.M.; Santos, F.S.D.; Gonçalves, G.R.; Freitas, J.C.C.; de Pietre, M.K. Effects of textural and chemical properties of β-zeolites on their performance as adsorbents for heavy metals removal. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidpour, M.; Afyuni, M.; Kalbasi, M.; Khoshgoftarmanes, A.H.; Inglezakis, V.J. Mobility and plant-availability of Cd(II) and Pb(II) adsorbed on zeolite and bentonite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 48, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscarella, S.M.; Badalucco, L.; Cano, B.; Laudicina, V.A.; Mannina, G. Ammonium adsorption, desorption and recovery by acid and alkaline treated zeolite. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 341, 125812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).