Abstract

The influence of synthesis method on the properties of Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles with different Fe doping levels (x = 0, 0.01, 0.03, and 0.05) for Congo Red (CR) adsorption was investigated. Nanoparticles were prepared by sol–gel and coprecipitation and characterized by XRD, SEM-EDS, FTIR, and BET analyses. Sol–gel synthesis produced smaller particles (~13 nm) than coprecipitation (~35 nm), and both the method and calcination temperature strongly affected crystallite size. Sol–gel nanoparticles showed significantly higher adsorption efficiency (~90%) due to their larger BET surface area, greater BJH pore volume, and smaller particle size, which increased the number of accessible active sites. In contrast, coprecipitation nanoparticles exhibited a much lower adsorption capacity (~24%). Fe incorporation further enhanced performance by introducing lattice distortions and oxygen vacancies, as evidenced by XRD peak broadening and increased lattice strain. SEM images displayed particle growth and compaction after adsorption, particularly in doped samples. Temperature-dependent experiments indicated that undoped ZnO lost efficiency at 60 °C due to weak physical interactions, whereas Fe-doped nanoparticles maintained high adsorption, due to improved stability of the adsorbent-adsorbate bond. The combination of Fe doping and sol–gel synthesis significantly improved the properties of ZnO, yielding highly efficient adsorbents suitable for environmental remediation.

1. Introduction

In recent years, zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles have garnered significant attention due to their physicochemical properties, with applications including sensors, solar cells, catalysts, adsorbents, and additives in various industrial products, among others [1,2].

This metal oxide, in its crystalline form, exhibits the wurtzite structure, characterized by a hexagonal unit cell with two lattice parameters: a = 3.2489(1) Å and c = 5.2053(4) Å under ambient conditions. Furthermore, ZnO nanostructures possess a high surface area and remarkable catalytic activity [3], making them attractive for the treatment of contaminated water [4].

Therefore, the challenge is to design practical, effective, and low-cost methods for the large-scale production of this nanomaterial.

Among the most promising synthesis methods, wet chemical processes such as sol–gel and coprecipitation allow nanostructures to be synthesized in a few steps and do not require complex instruments or techniques [5]. In this way, pure ZnO nanoparticles can be obtained, using non-toxic solvents and low synthesis temperatures [6].

The sol–gel method involves the transition from sol to gel, followed by drying and calcination, while the coprecipitation method involves converting a solution into an insoluble solid, which can be separated from the solution by sedimentation, filtration, and washing [7,8,9,10]. Since both methods enable the economical and reproducible production of ZnO nanopowders with different characteristics, a comparative study is crucial. This is particularly relevant given their broad range of applications, including contaminant adsorption, an area in which these materials are increasingly employed.

Regarding industrial pollution, the textile industry worldwide produces approximately 1 million tons of dyes annually, and almost 15% of these pollutants are discharged as effluents [11,12]. Effective treatment of colored wastewater is costly and requires chemical and energy-intensive processes.

The presence of dye traces in aqueous systems has led to severe environmental problems because many dyes exhibit toxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic properties [13]. Congo Red, in addition to having these characteristics, is interesting as a contaminant in industrial effluents and as a good model for complex pollutants [14].

Among the technologies available for water treatment, adsorption is a simple, economical, effective, and universal method [15]. ZnO nanoparticles have been frequently used for the adsorption of dyes, predominantly anionic dyes. At pH above 10, the surface species Zn(OH)3− and Zn(OH)42− dominate. However, at pH below 9, Zn(OH)+ and Zn2+ are the dominant species [16]. This explains CR’s affinity for the nanoparticles used as adsorbents.

Multiple studies demonstrate substantial improvements in dye removal through strategic metal doping. Srivastava et al. [17] found that Cu-doped ZnO nanoparticles were more efficient adsorbents than undoped ZnO. The performance improvements are substantial, with doping often increasing dye removal efficiency by 20−50%. Ebrahimi et al. [18] demonstrated that metal-doped ZnO increased dye removal from 18.4% to up to 74% under UV radiation. Sachin et al. [19] have shown that sol–gel-prepared ZnO nanoparticles doped with Fe, Co, and Mg at a nominal 2 wt% have a high removal efficiency for Congo Red from aqueous solutions. These consistent findings across different metal oxide systems provide strong evidence that doping is an effective strategy for enhancing nanoparticle-dye adsorption. Key mechanisms include increased surface area, inhibition of grain growth, enhanced surface dopant concentration, increased number of adsorption sites, and promotion of π–π and electrostatic interactions between the adsorbent and the adsorbate. In particular, it was shown that doping with Fe stabilizes ZnO nanostructures, induces micro/nano defects that modulate the crystal lattice disorder and the coupling strength in doped ZnO [20], and achieves a high concentration of oxygen vacancies through ion/vacancy diffusion and nanocrystal rearrangement [21]. Given that Fe is a low-cost, readily available, and low-toxicity element, Fe incorporation can enhance the properties of zinc oxide and improve its performance in water treatment via adsorption [22].

To date, no studies have compared ZnO nanoparticles obtained by different synthesis methods with respect to their physicochemical characteristics and performance in a specific application. Therefore, in this work, undoped and Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles (Zn1−xFexO with x = 0, 0.01, 0.03, and 0.05) were synthesized and characterized using and compared two methods: sol–gel and coprecipitation. Furthermore, the adsorption capacity of the obtained nanoparticles was evaluated for the treatment of aqueous solutions contaminated with Congo Red, providing a basis for future adsorption studies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

For the synthesis of the nanostructures, the following reagents were employed: zinc acetate dihydrate ([Zn(CH3CO2)2 2(H2O)], 98–101%, Biopack, Buenos Aires, Argentina), iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate ([Fe(NO3)3 9H2O], 98–101%, Biopack, Buenos Aires, Argentina), citric acid monohydrate (C6H8O7, ≥99%, Sigma Aldrich, Mumbai, India), ethylene glycol (C2H6O2, ≥99%, Biopack, Buenos Aires, Argentina), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, ≥97%, Cicarelli, Santa Fe, Argentina), ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH, 25–30%, Cicarelli, Santa Fe, Argentina) and absolute ethanol (C2H5OH, ≥99.5%, Biopack, Buenos Aires, Argentina). For the adsorption assays, Congo Red dye (C32H22N6Na2O6S2, ≥85%, Sigma Aldrich, Mumbai, India) was used (Table 1). All reagents were stored in a cool, dry, and dark environment. Ultrapure deionized water obtained from the OSMOION water purification system (APEMA S.R.L., Villa Dominico, Buenos Aires, Argentina) was used in all experiments.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the colorant used.

2.2. Synthesis of Zn1−xFexO Nanoparticles

ZnO nanoparticles doped with different Fe contents were synthesized in triplicate to obtain the Zn1−xFexO molar ratio (x = 0, 0.01, 0.03, and 0.05) by sol–gel and coprecipitation. In both methods, zinc acetate [Zn(CH3CO2)2 2(H2O)] was used as the metal precursor and ferric nitrate [Fe(NO3)3 9H2O] as the dopant.

For the sol–gel method, the procedure described in [23] was followed, with the addition of 2 mL of ethylene glycol as the surfactant. This involves the chelation of the precursor’s metal cations by surfactants in an aqueous environment. The solution was then allowed to form a yellow/orange gel, depending on the dopant concentration. Finally, the samples were dried at 120 °C for 24 h in an oven and subsequently calcined at 400, 600, and 800 °C for 2 h in a muffle furnace.

Coprecipitation synthesis was performed according to the procedure reported by [24], using the same precursors as for the sol–gel method, with the addition of 2 mL of ethylene glycol. The nanoparticles were rinsed with a 50% solution of double-distilled water and 50% ethanol and filtered repeatedly up to 6 times. Finally, the drying and calcination methods were applied under the conditions described above.

2.3. Characterization

The crystalline nature of Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles was analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD). The XRD patterns of the nanopowder samples were obtained with a SmartLab® X-ray (Rigaku Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) diffractometer (Cu Kα (λ = 1.5418 Å), 40 kV and 30 mA, 2θ from 0 to 80°, step of 0.05° and time of 1 s). All measurements were performed at ambient temperature. The average diameter of the crystalline domain of the nanostructures was estimated using the Debye-Scherrer model formula [25] according to the equation:

where D is the size of the coherently diffracting crystallite, λ is the incident X-ray wavelength (Cu Kα = 0.15406 nm), β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the X-ray peaks in radians, θ is the diffraction angle (Bragg half angle) in radians, and K is the correction factor typically taken as ~0.9 for spherical particles. The Williamson and Hall method was used to calculate the lattice strain (Ɛ) with the following equation [26]:

where βt represents the sum of the crystallite size contribution (β) and lattice strain contribution.

The morphology of the nanoparticles was studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a ZEISS EVO 15 microscope (Carl Zeiss NTS GmbH, Jena, Germany). The free ImageJ software (version 1.54) was used to process the obtained micrographs. Elemental analysis was performed by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) to verify the presence of Fe in the samples.

To determine the surface functional groups, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was performed using a Shimadzu IRSpirit FT-IR spectrometer with QATR-S AT (Kyoto, Japan) in the 5000–500 cm−1 region.

MicroMeritics ASAP2020 equipment (Micromeritics Instrument Corp., Norcross, GA, USA) was used to analyze the variations in surface area and porosity via nitrogen adsorption analysis (BET).

2.4. Adsorption Assays

Adsorption experiments with the nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel and coprecipitation, and calcined at 600 °C, were carried out in triplicate in a 50 mL volume, with magnetic stirring at 300 rpm and a CR concentration of 10 ppm. This concentration was chosen because most industrial effluents contain 5–30 ppm of CR [27]. Of the three calcination temperatures analyzed in this work (400, 600, and 800 °C), 600 °C was selected as a representative intermediate condition to enable comparisons of synthesis methods’ CR adsorption capacity. The amount of adsorbent in all adsorption experiments was kept at 0.05 g for the 50 mL reaction volume used, to minimize adsorbent for a standard adsorbate concentration. A contact time of 60 min was selected, since similar studies indicate that the adsorption percentage does not change after this time [28]. Additionally, all adsorption tests were carried out at pH 5, as previous studies have shown that the highest CR adsorption efficiency on doped ZnO nanoparticles occurs under acidic conditions, from pH 4–5 downward [19].

The dye concentration before and after the adsorption tests was determined using a UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-2550, Kyoto, Japan). The RC calibration curve was constructed using a concentration range of 1 to 20 ppm, obtained from serial dilutions of a 1000 ppm CR concentrated solution. The variation in dye concentration versus absorbance showed a linear relationship at λmax ≅ 500 nm, and the calibration curve had a high correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.993). The CR concentration in the solutions before and after adsorption was determined from the calibration curve equation.

From these obtained data, the adsorption percentage (%A) was calculated using the following equation [29]:

where Co is the initial concentration of the adsorbate or dye (ppm), and Cf (ppm) is the concentration of the adsorbate in the solution after the adsorption process and the removal of the adsorbent by centrifugation (5000 rpm for 5 min).

The Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles were homogenized in a mortar before the adsorption tests and dried at 80 °C for 24 h after the adsorption tests.

3. Results

3.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS)

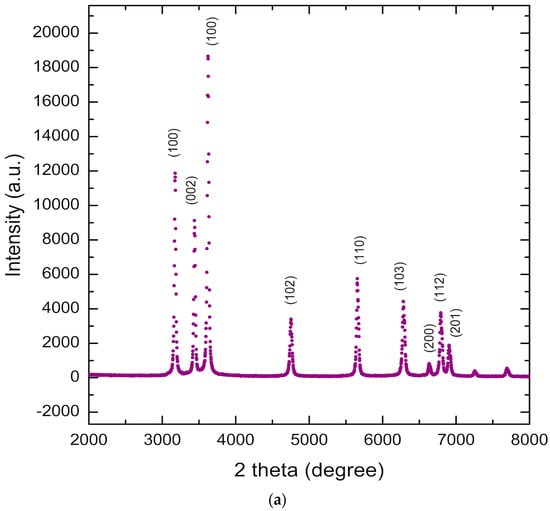

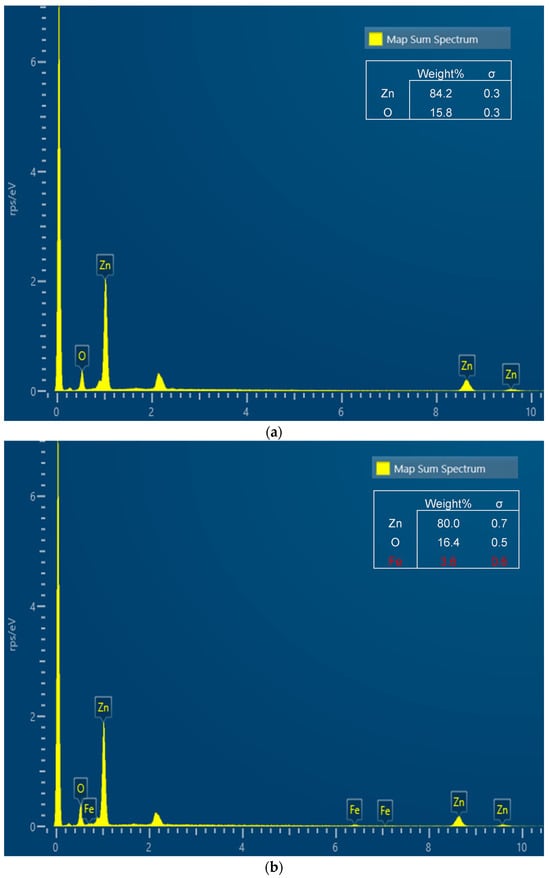

The phase purity and crystal structure of the Zn1−xFexO samples were examined by X-ray diffraction. The results for the undoped samples (Figure 1a) revealed that all diffraction peaks could be indexed to the hexagonal wurtzite structure of ZnO (P63mc), as specified by the Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS 36-1451 [30]) [31]. The absence of other peaks allows the exclusion of crystalline impurities [32].

Figure 1.

XRD diffraction pattern for undoped zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel (a). Diffractogram comparison of Zn1−xFexO samples (x = 0 and x = 0.05) synthesized by sol–gel and coprecipitation (b).

Figure 1b shows the diffractograms for undoped samples, in contrast to the higher Fe dopant concentration used in this study. The FWHM increases with increasing Fe content, indicating that the samples’ crystallinity decreases accordingly. A decrease in peak intensity with increasing Fe doping concentration is also observed.

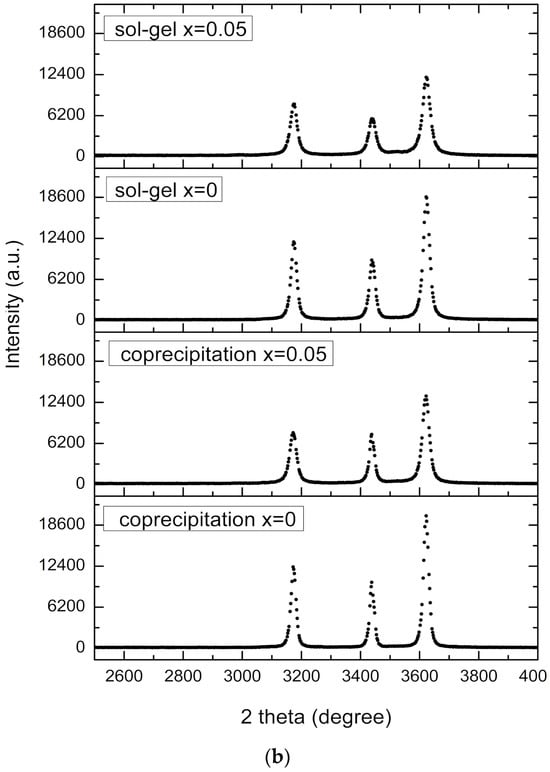

Figure 2 shows the EDS spectrum of an undoped sample (x = 0, Figure 2a) compared with a doped one (x = 0.05, Figure 2b). The results confirm the presence of Fe in all doped samples (spectra for 0.01 ≤ x ≤ 0.05), while it is absent in the pure ZnO sample.

Figure 2.

EDS spectrum for Zn1−xFexO samples with x = 0 (a) and x = 0.05 (b).

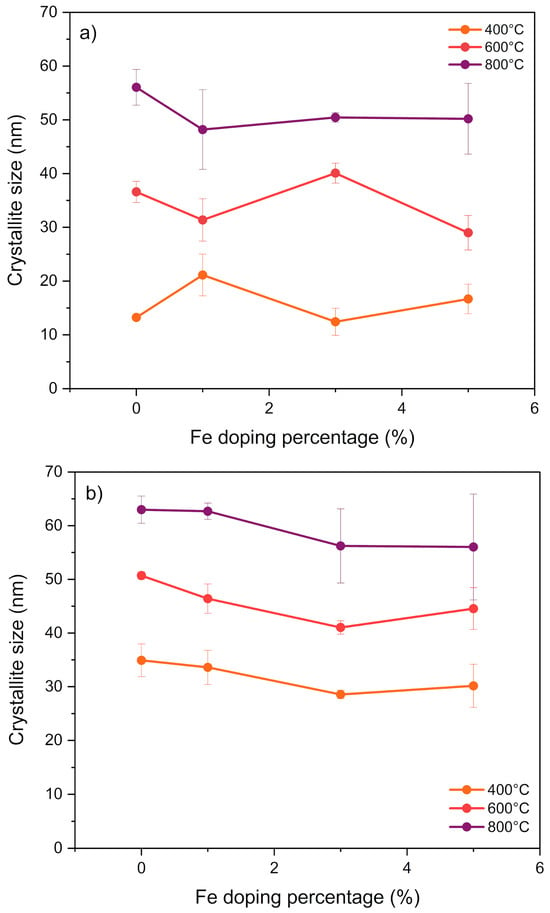

Figure 3 shows the sizes of the nanoparticles obtained by sol–gel and coprecipitation as a function of the Fe doping amount and the calcination temperature. The average crystalline domain size of the nanostructures was 13.23 ± 0.19 nm for the sol–gel synthesis and was almost three times higher for the nanoparticles obtained by coprecipitation (34.93 ± 3.05 nm), considering in both cases the samples calcined at 400 °C and without Fe doping. Furthermore, a direct relationship was observed between nanoparticle size and calcination temperature, with values ranging from 55 to 65 nm at 800 °C, depending on the synthesis method used. Moreover, the presence or amount of dopant did not significantly affect the change in nanoparticle size.

Figure 3.

Size of Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel (a) and coprecipitation (b) as a function of the amount of dopant and the calcination temperature.

The calculated lattice strain values (Ɛ) for the different Zn1−xFexO samples are listed in Table 2. These results demonstrate that Fe dopant increases lattice strain in both synthesis methods. The nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel display a higher Ɛ value, indicating greater distortions or internal stresses in the crystal lattice [33].

Table 2.

Lattice strain values (Ɛ) for the samples as a function of the synthesis method and the amount of dopant.

3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

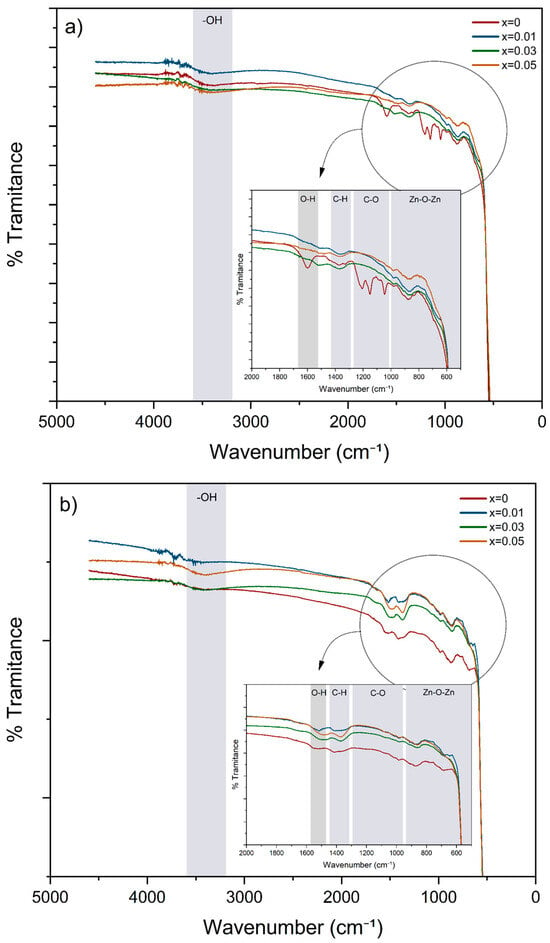

Infrared spectroscopy identifies material types and recognizes functional groups of synthesized nanoparticles. Figure 4 presents the results from FTIR-ATR analysis of Zn1−xFexO nanoparticle samples synthesized using both methods, with varying Fe concentrations. The shaded regions highlight the characteristic bands.

Figure 4.

FTIR spectra of Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles obtained by sol–gel (a) and coprecipitation (b), with a variable amount of Fe doping.

In both cases, a broad band is observed in the ~3600–3000 cm−1 region, which is associated with the –OH stretching vibration, attributable to surface hydroxyl groups and/or adsorbed water molecules [34]. In the middle region of the spectrum (2000–1000 cm−1), contributions corresponding to residual vibrations from precursors or synthesis agents are identified. The band at ~1600 cm−1 is associated with the H-O-H bending vibration of water. The peak in the 1300–1450 cm−1 region is attributed to the C-H symmetric bending vibration of the methyl groups (–CH3) [35]. The absorption bands in the 1000–1300 cm−1 range indicate the presence of the C-O group [36].

Metal oxides generally give absorption in the fingerprint region, below 1000 cm−1, due to interatomic vibrations [37]. In both graphs, the most essential band is observed in the low-frequency region (~600–400 cm−1) and corresponds to the antisymmetric vibration tension of the O–Zn–O bonds, confirming the formation of the ZnO crystal structure [38]. This signal appears defined in all samples analyzed in this study (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.05). In the doped samples, this Zn–O stretching peak shifts slightly towards lower frequencies, indicating a strain in the crystal lattice due to the partial replacement of Zn2+ by Fe3+ [39].

3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

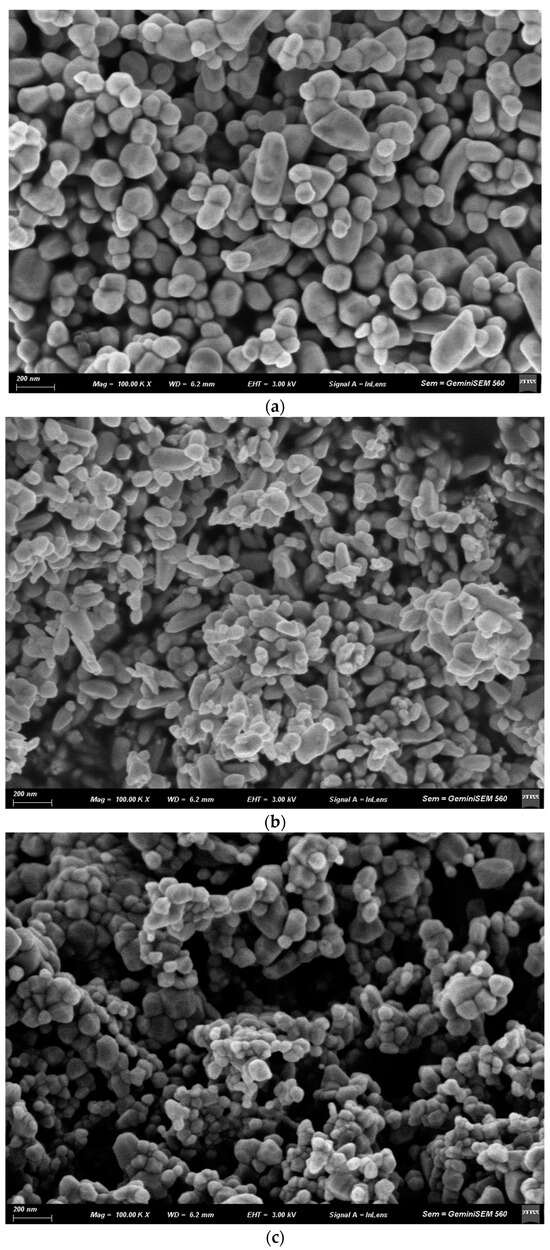

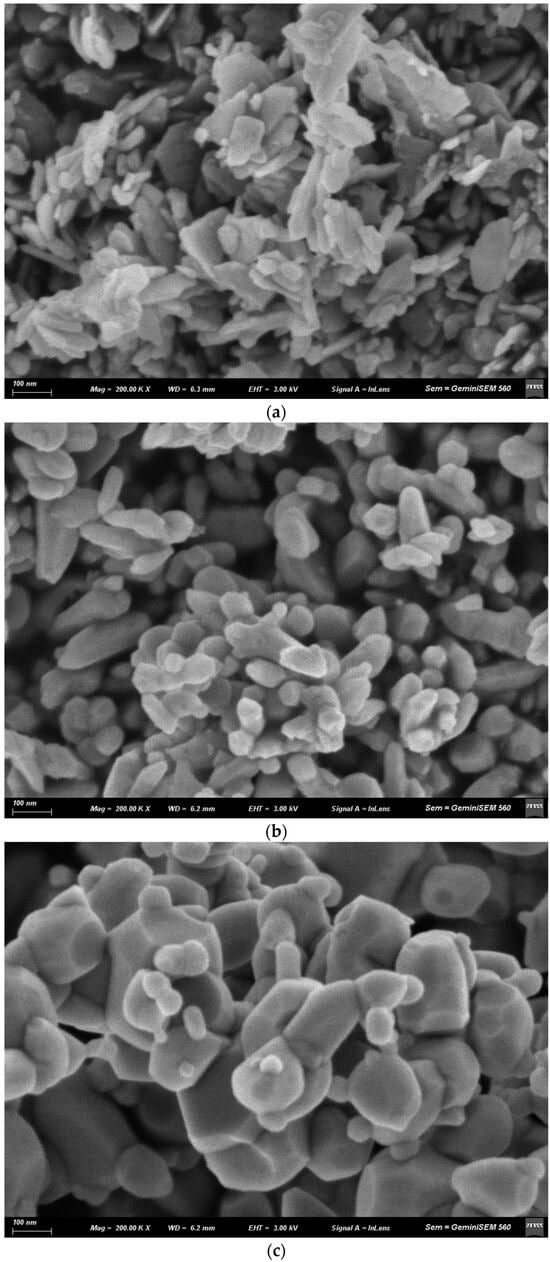

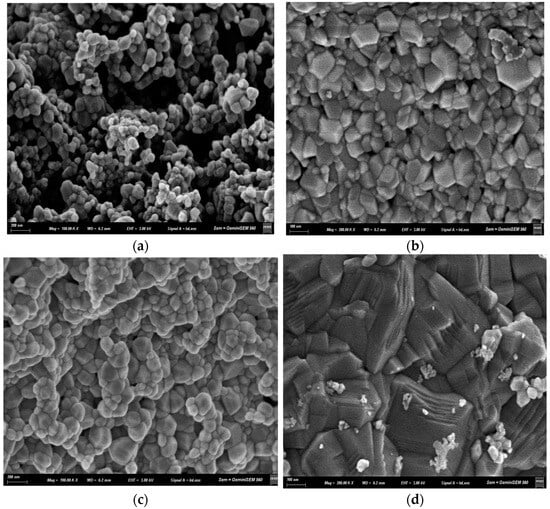

The morphological characteristics of the ZnO nanopowders were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Figure 5 shows comparative micrographs of Fe-doped and undoped ZnO nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel and coprecipitation methods, after calcination at 600 °C.

Figure 5.

SEM micrographs of Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles obtained by coprecipitation with x = 0 (a) and x = 0.05 (b), and by sol–gel with x = 0 (c) and x = 0.05 (d,e).

In agreement with the XRD results, the nanostructures synthesized by coprecipitation (Figure 5a) were approximately twice the size of the particles obtained by sol–gel (Figure 5c). These undoped coprecipitation samples were mostly spherical, though some were elongated and faceted. In contrast, Fe doping created geometries with clearer vertices.

The sol–gel samples (Figure 5d,e) had a more pointed, sharper structure than the coprecipitation samples (Figure 5b). Additionally, a predominantly polyhedral and homogeneous morphology with compact agglomeration was observed for the samples obtained by sol–gel and x = 0.05.

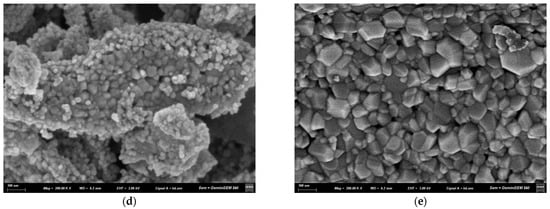

The effect of calcination temperature on the morphology of coprecipitation Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles with x = 0.05 is shown in Figure 6. At higher calcination temperatures, the nanoparticles exhibited more rounded shapes. Similar results were obtained for the sol–gel-synthesized samples under the same conditions.

Figure 6.

SEM micrographs of Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles with x = 0.05 obtained by coprecipitation and calcination at 400 °C (a), 600 °C (b) and 800 °C (c).

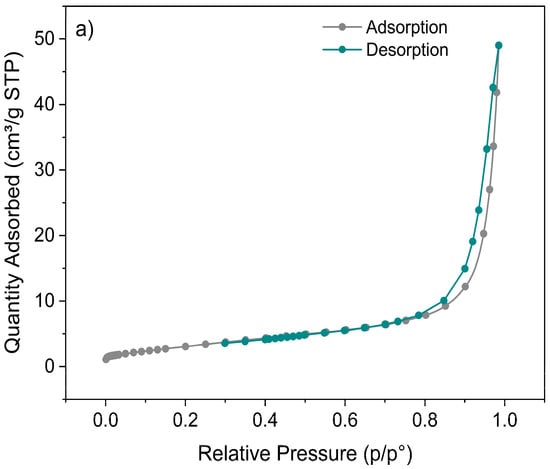

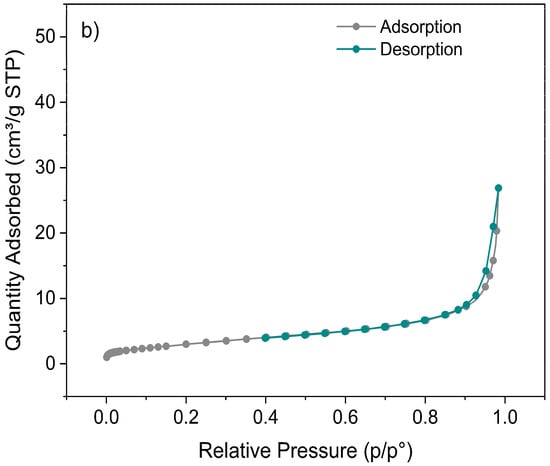

3.4. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller Analysis (BET)

BET analysis was performed to evaluate the porosity and specific surface area of the Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel and coprecipitation, calcined at 600 °C and x = 0.05.

The nanoparticles obtained by the sol–gel method showed a higher total BJH pore volume, with values of 0.0758 cm3/g in the adsorption branch and 0.0761 cm3/g in the desorption branch, versus the coprecipitation samples with 0.0421 cm3/g in adsorption and 0.0391 cm3/g in desorption. Additionally, exhibited a higher BET surface area, reaching 11.95 ± 0.23 m2/g, compared to the 11.31 ± 0.13 m2/g obtained for the nanoparticles synthesized by coprecipitation.

The adsorption/desorption isotherms (Figure 7) revealed that the volume of gas adsorbed per gram of sample (expressed as volume under standard conditions (STP)) was approximately twice that for the sol–gel synthesis compared to coprecipitation.

Figure 7.

BET adsorption–desorption isotherms of N2 for the Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles obtained by sol–gel (a) and coprecipitation (b), at a calcination temperature of 600 °C and x = 0.05.

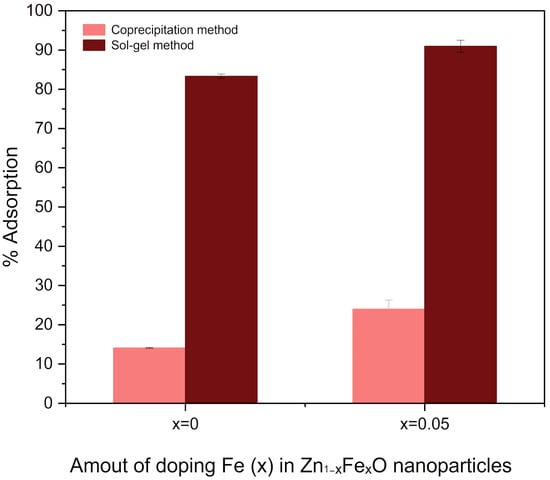

3.5. Adsorption Assays

The adsorption of CR at 10 ppm by Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles prepared by each synthesis method, doped or undoped with Fe, was compared (Figure 8). The undoped nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel exhibited a higher adsorption percentage (%A greater than 80%) than those synthesized by coprecipitation (%A greater than 10%). Furthermore, it was determined that adding Fe to the nanoparticles increases the percentage of CR adsorbed.

Figure 8.

CR adsorption percentage by Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles undoped (x = 0) and doped (x = 0.05), synthesized by sol–gel (dark bars) and coprecipitation (light bars).

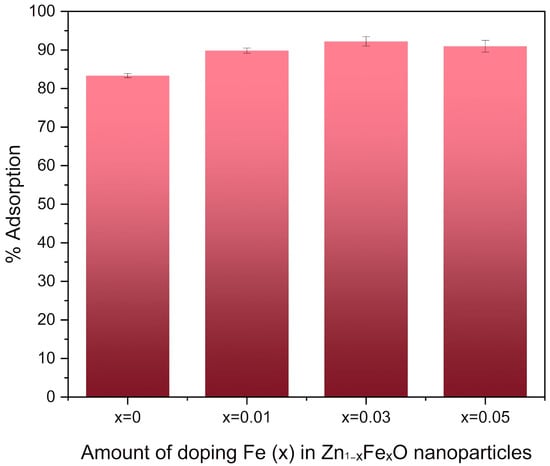

To elucidate the importance of Fe as a dopant in the adsorption of CR, adsorption experiments were carried out using sol–gel Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles with varying Fe concentrations, due to their superior performance compared to those obtained by coprecipitation. A 10% increase in the percentage of adsorption was obtained for the nanoparticles with Fe in the crystal lattice (x = 0.01, x = 0.03 and x = 0.05) compared to the undoped samples (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

CR adsorption percentage for Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel and with variable Fe doping percentage.

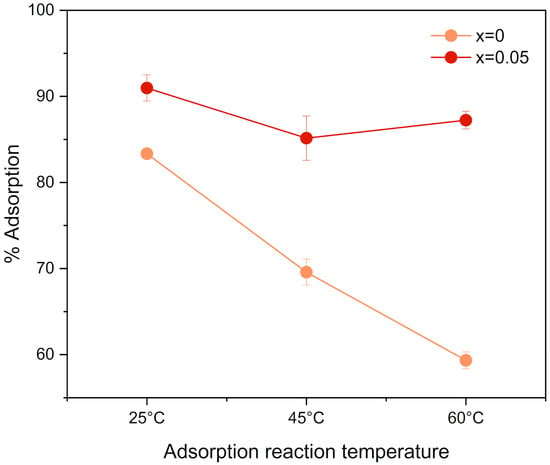

The variation in the percentage of CR adsorption for Zn1−xFexO sol–gel nanostructures with x = 0 and x = 0.05 was also analyzed as a function of temperature. Figure 10 shows that CR adsorption on undoped nanoparticles decreases with temperature, indicating an exothermic process as reported [40]. In doped nanoparticles, temperature had no effect, with about 90% adsorption across the range.

Figure 10.

CR adsorption percentage according to each type of nanostructure used as an adsorbent, varying the percentage of Fe dopant and the reaction temperature.

Micrographs of the Zn1−xFexO sol–gel nanoparticles before and after CR adsorption are shown in Figure 11. The nanoparticles turned red after adsorption, with size increases of 67% in the undoped and 92% in the doped samples (x = 0.05) relative to the initial size. Before adsorption, nanoparticles had well-defined edges and a granular distribution (Figure 11a,b), but after adsorption, they formed a more compact structure with smooth edges due to the dye (Figure 11c,d).

Figure 11.

SEM micrographs of Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles obtained by sol–gel and calcination at 600 °C, before CR adsorption with x = 0 (a) and x = 0.05 (b) and after CR adsorption with x = 0 (c) and x = 0.05 (d).

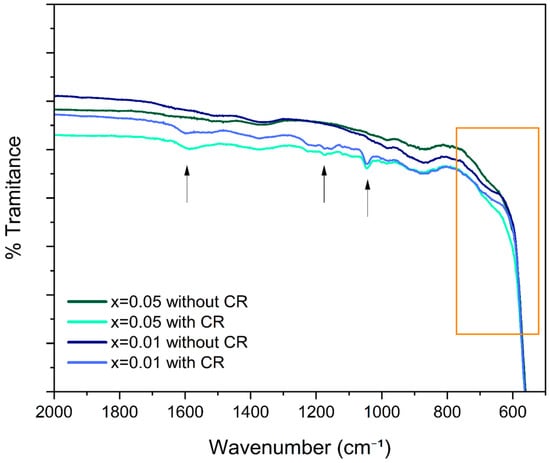

Congo Red (CR) is an anionic dye, and its structure contains two (–N=N–) groups linked to aromatic rings, as well as two sulfonate groups (–SO3−) attached to these rings. In aqueous solution, these sulfonate groups are fully ionized to –SO3−, giving the molecule a net negative charge, which causes CR to behave as a strong anionic dye with high affinity for positively charged surfaces. Figure 12 shows the FTIR spectra for the Zn1−xFexO samples with x = 0 and x = 0.05, before and after CR adsorption, only in the region between 2000 and 500 cm−1. In the samples with adsorbed CR, new peaks or intensity increases appear in the region between 1000 and 1600 cm−1, associated with the vibrations of the functional groups of the dye, such as C–N, C–C aromatic stretching (~1400–1600 cm−1), N=N (~1500–1570 cm−1) and S=O (~1180–1250 cm−1) [41,42]. The appearance of these bands confirms the presence of the dye in the nanoparticle samples. In turn, a shift in the nanomaterial’s fingerprinting region to a higher or lower wavenumber, in this case the O-Zn-O stretching band (~600−400 cm−1), is evidence that the dye has bonded to the surface and is not merely present [43]. This is observed in both cases (x = 0.01 and x = 0.05) in Figure 12, compared with their dye-free counterparts (orange-highlighted frame).

Figure 12.

FTIR spectra of Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles obtained by sol–gel, with a variable amount of Fe doping and before and after CR adsorption. The highlighted orange frame shows the ZnO fingerprinting region, and the arrows indicate the peaks associated with the functional groups of CR.

4. Discussion

4.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) and Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS)

Undoped ZnO nanoparticles exhibited high crystallinity, evidenced by the high peak intensity and smoothed baseline (Figure 1a). Also, Fe in the doped samples was successfully identified by EDS (Figure 2b). The FWHM of an XRD pattern indicates the degree of disorder in the crystal structure. It increased with Fe content, showing decreased crystallinity (Figure 1b). This is explained by an increase in the number of cationic vacancies due to the substitution of Zn2+ by Fe3+ in the zinc oxide unit cell [44], and can be attributed to the difference in the ionic radius of Zn2+ (0.74 Å) compared to that of Fe3+ (0.64 Å) [45]. Furthermore, the absence of additional phases in the doped samples suggests that Fe was successfully incorporated into the ZnO crystal lattice across the entire concentration range studied (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.05). Wet chemical methods are excellent for nanoparticle synthesis, particularly for incorporating dopants with high precision and control [46].

As the calcination temperature increases, a tendency toward larger crystallite size is observed (Figure 3). High temperatures cause grain boundary migration, leading to the coalescence of small grains into larger ones. These results show that the crystalline domain size was determined by the synthesis method and influenced by the calcination temperature. The synthesis, surface modification, and size-dependent properties of nanoparticles are crucial to ensuring biocompatibility, stability, and specific functionality [47].

4.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

In the doped samples, the Zn–O stretching peak in Figure 4 shifts slightly to lower frequencies, providing further evidence of successful doping. No other peaks are visible in this region, indicating no new phases such as Fe oxides, consistent with the XRD results. The reduction in bands corresponding to surface-adsorbed water demonstrates that the nanoparticles were practically dry.

The FTIR spectra showed differences in the intensity of weak bands outside the fingerprint region, which are typically associated with surface groups or residual species. This highlights the influence of synthesis conditions [48].

4.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The main morphological differences between the Fe-doped and undoped nanoparticles (Figure 5) included the appearance of pointed edges or shapes, as reported by [49]. This can be attributed to a progressive shift in the preferential direction of crystal growth, with marked anisotropic growth along a primary axis driven by increased dopant concentration.

In the doped sol–gel-synthesized samples, the nanoparticles aggregated into larger structures composed of small prisms, ranging in size from 200 nm to 1 µm (Figure 5d,e). These results are consistent with other authors [50,51], who found that nanoparticles form larger agglomerates at higher Fe concentrations, confirming that doping reduces surface repulsion between particles. Furthermore, changes in the morphology and surface charge of the nanostructures, as well as slight magnetic interactions induced by Fe doping in the ZnO crystal structure, may be responsible for coalescence. These nanoparticles can retain Fe3+/Fe2+ magnetic moments, which can partially align and form collective magnetic domains or clusters when they approach each other [52]. Several authors agree that the presence of Fe generates magnetic moments on the surface of the doped nanoparticles, resulting in residual magnetic dipoles even in the absence of an external field [53]. Doping is also likely to alter the particles’ isoelectric point or zeta potential. Near the isoelectric point, colloidal stability decreases. Doping can modify these parameters, reducing electrostatic repulsion and promoting particle-particle contacts [54].

The higher calcination temperature favored nanoparticle agglomeration, as evidenced by increased nucleation and growth rates (Figure 6). The fusion of grain boundaries resulted in larger particle sizes at these temperatures (as observed in the XRD analysis). Similarly, a lower specific surface area has been reported at higher calcination temperatures [55].

4.4. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller Analysis (BET)

BJH’s larger total pore volume shows that sol–gel nanoparticles have a more extensive, interconnected pore system with a greater surface area than those by coprecipitation. These results are consistent with BET and could explain the higher performance in applications such as adsorption or photocatalysis [56,57].

The adsorption/desorption isotherms showed that the nanoparticles obtained by sol–gel had the highest gas adsorption per gram of sample under standard conditions (STP) and a larger surface area. This indicates an enhanced adsorption capacity and a more porous texture than those of the coprecipitation samples.

4.5. Adsorption Assays

Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles synthesized by the sol–gel method demonstrated superior CR adsorption efficiency compared with those obtained by coprecipitation. This could be attributed to the increase in the specific surface area of the nanostructures, which increases the number of active sites available for dye adsorption. The higher quantity adsorbed (cm3/g STP) measured for the sol–gel sample—together with an increased BJH pore volume and larger BET area—indicates an enhanced adsorption capacity and a more open porous texture compared to the coprecipitated sample, in agreement with standard interpretations of N2 adsorption isotherms. This is also consistent with the smaller nanoparticles synthesized by the sol–gel method. This relationship is supported by the inverse proportionality between particle size and specific surface area per volume, as described in the literature [58,59]. Nanoparticles in the 0–100 nm range exhibit highly curved surfaces with a large surface-to-volume ratio, and such curvature can be controlled by adjusting the particle size. This feature can lead to tunable adsorption or molecular binding [60].

The addition of Fe to the ZnO crystal structure increased the adsorption capacity of the nanoparticles. It could be inferred that the partial substitution of Zn2+ by Fe3+ alters the crystalline lattice and could generate structural defects and oxygen vacancies that act as preferential adsorption sites (with greater affinity towards molecules such as CR) [61]. There is a close relationship among lattice strain, residual stress and defects, as they are interconnected [62]. The crystal lattice near a defect undergoes elastic deformation or distortion [63], and this broadens the diffraction peaks, as observed in the diffractograms of the Fe-doped samples (Figure 1b). In nanostructured materials, XRD peak broadening can originate from both small crystalline domains, which limit long-range order, and lattice microstrain, which introduces slight variations in interplanar spacing. Both effects could be responsible for the peak broadening observed in the XRD patterns of the Fe-doped nanoparticles. In this regard, an increase in the lattice strain value was observed for both the doped and sol–gel synthesized samples (Table 2). This suggests a greater number of defects in the doped sol–gel samples, which explains their improved CR adsorption performance.

SEM micrographs after adsorption showed a more compact structure and larger nanoparticles. This result is consistent with other studies evaluating the adsorption of organic dyes onto nanostructures [64,65,66]. Furthermore, the increase in particle size was more pronounced with Fe addition, confirming that doping enhanced adsorption.

Increasing the reaction temperature decreased the adsorption percentage for the undoped nanoparticles, reaching approximately 60% at 60 °C. However, no significant decrease in adsorption was observed for the doped nanoparticles. This can be explained by CR adsorption on undoped ZnO being primarily physical, with weak interactions between the adsorbate and the adsorbent, in which the adsorbed molecules gain more kinetic energy as temperature increases and are easily desorbed. On the other hand, the doped samples possess more stable active sites generated by the substituted Fe3+ ion, enabling the nanomaterial to maintain high adsorption efficiency even upon heating. This is consistent with previous work supporting the theory of increased stability and adsorption of ZnO doped with transition metals [67], thereby improving the stability of the adsorbent-adsorbate bond. Furthermore, Fe can play an essential role in strengthening Van der Waals forces within materials [68].

5. Conclusions

The study demonstrates that synthesis conditions strongly influence the properties and performance of Zn1−xFexO nanoparticles, allowing near-complete Congo Red adsorption (~100%) with a minimal amount of nanoadsorbent. Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles produced by sol–gel synthesis exhibited improved CR adsorption performance compared to nanoparticles synthesized by coprecipitation. The enhanced efficiency is primarily attributed to their larger BET surface area and higher BJH pore volume, both of which reflect a more open and accessible porous network. These improvements also complement the smaller particle size achieved through sol–gel synthesis, which increases the surface-to-volume ratio and, consequently, the number of active adsorption sites. Furthermore, the incorporation of Fe significantly improved the adsorption capacity by generating lattice distortions, oxygen vacancies and defects, resulting in energetically favorable sites for CR binding. SEM analyses confirmed post-adsorption agglomeration and particle growth, particularly pronounced in doped samples, aligning with dye-nanostructure interactions. Finally, temperature-dependent experiments revealed that undoped ZnO is more susceptible to thermal desorption due to weaker interactions with CR. In contrast, Fe-doped nanoparticles maintained high adsorption efficiency even at elevated temperatures, owing to more stable active sites introduced by Fe3+ substitution. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing the production of effective adsorbents and show that it is possible to develop nanoparticles tailored explicitly for the efficient removal of organic dyes, providing a practical strategy for environmental remediation and sustainable water treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y.P. and G.R.K.; methodology, C.Y.P.; validation, G.R.K., P.D.Z. and A.E.A.; formal analysis, C.Y.P.; investigation, G.R.K.; resources, A.E.A.; data curation, F.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Y.P.; writing—review and editing, F.A.B.; visualization, P.D.Z.; supervision, A.E.A.; project administration, A.E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lebaka, V.R.; Ravi, P. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles in Modern Science and Technology: Multifunctional Roles in Healthcare, Environmental Remediation, and Industry. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Gusain, D. Synthesis, characterization and application of zinc oxide nanoparticles (n-ZnO). Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 9803–9808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-C.; Tang, C.-T. Preparation and application of granular ZnO/Al2O3 catalyst for the removal of hazardous trichloroethylene. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 142, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iandolo, B.; Hagfeldt, A. Zinc Oxide Nanostructures for Water Treatment: Synthesis, Properties and Applications. Crystals 2024, 14, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, N.B.; Saeed, F.R. Synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles via oxalate co-precipitation method. Mater. Lett. X 2022, 13, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carofiglio, M.; Barui, S. Doped Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization and Potential Use in Nanomedicine. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azam, A.; Khan, Z.M. Formation and characterization of ZnO nanopowder synthesized by sol–gel method. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 495, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziejczak-Radzimska, A.; Jesionowski, T. Zinc Oxide—From Synthesis to Application: A Review. Materials 2014, 7, 2833–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiee, P.; Reisi Nafchi, M. Sol-gel zinc oxide nanoparticles: Advances in synthesis and applications. Synth. Sinter. 2021, 1, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Ayon, S.A. Comparative study of structural, optical, and photocatalytic properties of ZnO synthesized by chemical coprecipitation and modified sol–gel methods. Surf. Interface Anal. 2023, 55, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, A.M.S.; Athira, K.K. Textile dyes effluents: A current scenario and the use of aqueous biphasic systems for the recovery of dyes. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 49, 104125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, A.B.; Blandino, A. Modelling of different enzyme productions by solid-state fermentation on several agro-industrial residues. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 9555–9566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Singh, V.P.; Bhat, S.B.; Kumar, R. Environmental risks of textile dyes and photocatalytic materials for sustainable treatment: Current status and future directions. Discov. Environ. 2025, 3, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbani, P.; Tabatabaii, S.M. Removal of Congo red from textile wastewater by ozonation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 5, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attallah, M.F.; Ahmed, I.M. Treatment of industrial wastewater containing Congo Red and Naphthol Green B using low-cost adsorbent. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labille, J.; Brant, J. Stability of nanoparticles in water. Nanomedicine 2010, 5, 985–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.; Choubey, S. Kinetic and isothermal study of effect of transition-metal doping on adsorptive property of zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized via green route using Moringa oleifera leaf extract. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 036306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, R.; Hossienzadeh, K. Effects of doping zinc oxide nanoparticles with transition metals (Ag, Cu, Mn) on photocatalytic degradation of Direct Blue 15 dye under UV and visible light irradiation. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2019, 17, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachin; Pramanik, B.K.; Singh, N.; Zizhou, R.; Houshyar, S.; Cole, I.; Yin, H. Fast and Effective Removal of Congo Red by Doped ZnO Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahma, S.; Lo, C.-Y. Defect induced crystal lattice disorder and its effect on the electron-phonon coupling in Fe-doped ZnO thin films. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2024, 190, 111999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.-Y.; Wang, S. Modulating nanograin size and oxygen vacancy of porous ZnO nanosheets by highly concentrated Fe-doping effect for durable visible photocatalytic disinfection. Rare Metals 2024, 43, 5905–5920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, T.H.; Prasad, G.K. Nanocrystalline zinc oxide for the decontamination of sarin. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 165, 928–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. Structural, optical and magnetic properties of Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 239, 122180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchana, S.; Chithra, M.J. Violet emission from Fe doped ZnO nanoparticles synthesized by precipitation method. J. Lumin. 2016, 176, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Sarkar, R. Synthesis, characterization and tribological study of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 44, 3606–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revathi, G.; Sangari, N.U. Morphology dependent photocatalytic efficiency of nano ZnO towards Azure A dye. Open Ceram. 2023, 16, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, N. Adsorption of Congo red dye on FexCo3−xO4 nanoparticles. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 238, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şişmanoğlu, T.; Pozan, G.S. Adsorption of Congo red from aqueous solution using various TiO2 nanoparticles. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 13318–13333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, B.; Patra, T. An efficient and comparative adsorption of Congo Red and Trypan Blue dyes on MgO nanoparticles: Kinetics, thermodynamics and isotherm studies. J. Magnesium Alloys 2021, 9, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JCPDS 36-1451; Zinc Oxide-Powder Diffraction File. International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD): Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2024.

- Wahab, R.; Mishra, A. Antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticles prepared via non-hydrolytic solution route. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 1917–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swapna, P.; Venkatramana Reddy, S. Structural, optical & magnetic properties of (Fe, Al) co-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles. Nanoscale Rep. 2019, 2, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousslama, W.; Elhouichet, H.; Férid, M. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of Fe-doped ZnO nanocrystals under sunlight irradiation. Optik—Int. J. Light Electron Opt. 2017, 134, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramawy, A.M.; Agami, W.R. Tailoring the preparation, microstructure, FTIR, optical properties and photocatalysis of (Fe/Co) co-doped ZnO nanoparticles (Zn0.9FexCo0.1−xO). Ceramics 2025, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, W.; Ullah, N. Optical, morphological and biological analysis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) using Papaver somniferum L. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 29541–29548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Arjan, W.S. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Application in Adsorption of Toxic Dye from Aqueous Solution. Polymers 2022, 14, 3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janaki, A.C.; Sailatha, E. Synthesis, characteristics and antimicrobial activity of ZnO nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 144, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazargan, M.; Ghaderi, E. Effect of temperature on the structure, catalyst and magnetic properties of un-doped zinc oxide nanoparticles: Experimental and DFT calculation. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 12345–12358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouzaia, F.; Djouadi, D. Particularities of pure and Al-doped ZnO nanostructures aerogels elaborated in supercritical isopropanol. Arab J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2020, 27, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, P.; Mondal, N.K. Effective removal of Congo Red dye from aqueous solution using biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2020, 14, 100320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yin, W. Efficient removal of Congo red, methylene blue and Pb(II) by hydrochar–MgAlLDH nanocomposite: Synthesis, performance and mechanism. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Wang, D. Enhanced adsorption of Congo red using chitin suspension after sonoenzymolysis. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020, 70, 105327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapat, A.; Aslam, M. Computational supported experimental insights in adsorption of Congo Red using ZnO/doped ZnO in aqueous solution. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuli, G.; Eisenmann, T. Structural and Electrochemical Characterization of Zn1−xFexO—Effect of Aliovalent Doping on the Li⁺ Storage Mechanism. Materials 2018, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wei, Z. Optical and magnetic properties of Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles obtained by hydrothermal synthesis. J. Nanomater. 2014, 2014, 792102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, C.K.; Nigam, S. Lanthanide Ions-Doped Nanomaterials for Light Emission Applications. In Emerging Trends of Research in Chemical Sciences; Chakraborty, T., Chaudhary, S., Eds.; Apple Academic Press: Palm Bay, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 55–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanità, G.; Carrese, B.; Lamberti, A. Nanoparticle Surface Functionalization: How to Improve Biocompatibility and Cellular Internalization. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 587012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Pal, U. Photoluminescence and FTIR study of ZnO nanoparticles: The impurity and defect perspective. Phys. Status Solidi C 2006, 3, 3577–3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, A.; Kumar, Y. Doping concentration driven morphological evolution of Fe-doped ZnO nanostructures. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 116, 164315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, K.B.; Mohite, S.V. Studies on effect of Fe doping on ZnO nanoparticles’ microstructural features using x-ray diffraction technique. Phys. Scr. 2025, 100, 065904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elkader, O.H.; Nasrallah, M. Biosynthesis, Optical and Magnetic Properties of Fe-Doped ZnO/C Nanoparticles. Surfaces 2023, 6, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.E.; Montero-Muñoz, M. Evidence of a cluster glass-like behavior in Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 115, 17E123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokesha, H.S.; Mohanty, P. Structure, optical and magnetic properties of Fe-doped, Fe + Cr co-doped ZnO nanoparticles. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.07266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmulski, M. The pH dependent surface charging and points of zero charge. IX. Update. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 296, 102519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schelonka, D.; Tolasz, J. Doping of Zinc Oxide with Selected First Row Transition Metals for Photocatalytic Applications. Photochem. Photobiol. 2015, 91, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, Q. Estimation of shale pore-size distribution from N2 adsorption characteristics employing modified BJH algorithm. Int. J. Light Electron Opt. 2021, 39, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.G.; Salinger, J.L. Determining Surface Areas and Pore Volumes of Metal-Organic Frameworks. J. Vis. Exp. 2024, 65716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dazon, C.; Fierro, V. Identification of nanomaterials by the volume specific surface area (VSSA) criterion: Application to powder mixes. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 4908–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altammar, K.A. A review on nanoparticles: Characteristics, synthesis, applications, and challenges. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1155622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolai, J.; Mandal, K. Nanoparticle Size Effects in Biomedical Applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 6471–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.B.S.; Parajuli, D. Effect of Fe-doped and capping agent—Structural, optical, luminescence, and antibacterial activity of ZnO nanoparticles. Chem. Phys. Impact 2023, 7, 100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolabella, S.; Borzì, A. Lattice Strain and Defects Analysis in Nanostructured Semiconductor Materials and Devices by High-Resolution X-Ray Diffraction: Theoretical and Practical Aspects. Small Methods 2022, 6, e2100932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzì, A.; Dolabella, S. Microstructure analysis of epitaxial BaTiO3 thin films on SrTiO3-buffered Si: Strain and dislocation density quantification using HRXRD methods. Materialia 2020, 14, 100953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, E.A.; Korsa, H.A. Electrolytic synthesis of γ-Al2O3 nanoparticle from aluminum scrap for enhanced methylene blue adsorption: Experimental and RSM modeling. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majani, S.S.; Manoj; Lavanya, M.; Swathi, B.; Anuvarna, N.; Iqbal, M.; Kollur, S.P. Nano-catalytic behavior of CeO2 nanoparticles in dye adsorption: Synthesis through bio-combustion and assessment of UV-light-driven photo-adsorption of indigo carmine dye. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, M.A.; El-Sayed, G.O. Adsorptive removal of Pb2+ from wastewater using ZnO-biochar nanocomposite: Kinetic, isotherm and morphological studies. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Duan, Y.; Qin, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Ding, H. Adsorption and sensing performances of transition metal doped ZnO monolayer for CO and NO: A DFT study. SSRN 2024, 26, 4958262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muedi, K.L.; Masindi, V. Effective adsorption of Congo Red from aqueous solution using Fe/Al di-metal nanostructured composite synthesised from Fe(III) and Al(III) recovered from real acid mine drainage. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).