Abstract

Israeli higher education institutes are challenged by the growing number of ultra-orthodox students. This requires coping with novel aspects unfamiliar to participants, as students and as teachers in the education system, utilizing online learning as a lever for empowering this marginalized population. The aim of the proposed research was to explore perceptions of ultra-orthodox students studying in B.Ed. programs within a secular college of education towards online courses. Data included transcriptions from 68 narratives of interviews, which were analyzed using a mixed-methods approach, which helped us achieve an in-depth understanding of the difficulties and challenges of these higher education students. Altogether, five themes were identified, namely: technical challenges, ethical/religious challenges, academic challenges, engagement challenges, and aspects of availability. Statements referring to academic challenges and engagement challenges were the most frequent. The number of positive and negative statements was balanced. Also, distinct patterns of responses were identified for married vs. single ultra-orthodox women. Findings demonstrate the complexity of utilizing online learning among ultra-orthodox B.Ed. students, in a twofold manner: personally and community-wise. The study may shed light on online learning in additional marginal communities worldwide that are traditional in nature, and that may benefit from online courses.

1. Introduction

The Israeli ultra-orthodox society is an example of a society with distinct contextual factors. The society comprises approximately 12% of Israel’s population. It is characterized by ideological, religious, and social differences. The commonalities are portrayed by their faith and study of the Torah (religious scripts) as a fundamental and defining value, and social isolation as a measure of protecting the community and preserving the traditional way of life (Meoded & BenDavid-Hadar, 2025). However, recently this relatively closed society has been affected by rapid changes that the general society has previously experienced (Blondheim, 2015). Ultra-orthodox consequently find themselves contemplating the possibilities of integrating work with Torah studies, and also acknowledging the value of higher education for promoting one’s socio-economic status (Naor et al., 2022). Typically, ultra-orthodox women are employed full-time in education roles, often because they are the primary breadwinners. Their husbands, generally engaged as “Avrechim” in Yeshiva studying the Talmud, receive only a modest stipend (Taragin-Zeller & Stadler, 2022).

The need for internet access was emphasized during the past few years. While regarded as unconventional in the ultra-orthodox society, Internet access was needed for work, education, communication, and even remote religious studying. Still, Internet use indeed grew from 28% in 2008 to 70% in 2022–2023, but it is relatively low compared to 93% in the general Jewish society. The growing employment rates and academic enrollment within the ultra-orthodox population contribute to their increased exposure to and usage of the Internet Top of FormBottom of Form (Cahaner & Malach, 2024).

While technology implementation requires acquisition of digital competencies and technological skills—in the case of educators, skills that support their pedagogical practices—these techno-pedagogical abilities are insufficient for educational purposes (Cebi et al., 2022; Kontkanen et al., 2016). This is partly the result of the complexity of applying digital competence within educational settings. The development of these competencies depends on several contextual and institutional factors (Pettersson, 2018). Specifically, the field of practice and research regarding online courses for ultra-orthodox students is new and challenging, since no one theory regarding online education may be applied to this specific society, which is unaccustomed to the online mode of teaching and learning.

1.1. Digital Competencies of Educators

Educators are expected to cope with complex problems and situations that usually do not have a single and simple or straightforward answer during their training (Forkosh-Baruch, 2018; Körkkö et al., 2024). Consequently, countries worldwide have provided programs and frameworks for teacher preservice training that include ICT skills and competencies to utilize information technologies (Tondeur et al., 2017). This is considered a requirement of the information era and an obligatory product of teacher training and practice (Forkosh-Baruch, 2018; Luik et al., 2018). These may be achieved through modes of training that include a designated course for 21st century skills and competencies, or in various subjects, which focus in turn on pedagogical practices using technology for teaching and learning (Paşa et al., 2022).

Students in the education system are also expected to plan and conduct research as an integral part of their professional identity (O’Sullivan & Dallas, 2017). Accordingly, teacher education aspires to connect ultra-orthodox preservice and in-service teachers to academia in the digital era (Eisenberg & Selivansky, 2019). Online learning indeed poses several such conflictual situations, due to restrictions posed by the rabbinic authorities (Y. Cohen, 2017; Meoded & BenDavid-Hadar, 2025).

Teaching and learning in online settings involve different and diverse interaction and engagement patterns of students. On one hand, online settings have the potential to overcome technical, linguistic, and cross-cultural obstacles, due to exposure to diverse participants that express the need to assist one another and create an inclusive learning environment (Bonk & Zhu, 2024). Hence, the need to be more attentive by acknowledging that communication may be hindered can have a counter-effect: it can make online communication efficient, for example, in project-based learning (Aslan, 2021). On the other hand, due to inability to deploy adequate emotional cognition and connect as effectively as in face-to-face teaching and learning, this may be a significant obstacle. Since online teaching lacks the richness of social cues and gestures, students and teachers may experience feelings of loneliness and isolation and, consequently, lower satisfaction rates (Guo et al., 2023).

1.2. The Ultra-Orthodox Society and Academia

Academic education allows attainment of social and economic opportunities in a society characterized by opportunities for genuine mobility (Genut & Kolikant, 2017). The ultra-orthodox community also embraces these academic trends, reflecting their growing appreciation for scientific knowledge and respect for academic institutions (Golan & Fehl, 2020). Improving socioeconomic status is particularly relevant within the ultra-orthodox women subgroup, who are the sole providers in some families, in which the husband is expected to study the holy scriptures (Kalagy & Braun-Lewensohn, 2019).

Indeed, recent decades have challenged Israeli higher education as a result of the rising attendance of ultra-orthodox men and women in academic institutes (Bowman & Smedley, 2013; Novis Deutsch & Rubin, 2019). Notwithstanding, ultra-orthodox educational institutions do not incorporate technology widely as a result of restrictions issued by rabbinic authorities (Y. Cohen, 2017). These restrictions are fundamental to preserving tradition, while modern values, which may promote individualism, personalization, collaboration, and accessibility, are perceived as contradicting core ultra-orthodox values, posing challenges to tradition, collective identity, and religious authority (Kalagy & Braun-Lewensohn, 2019; Neriya-Ben Shahar, 2017). For example, only about 69% of ultra-orthodox women make use of the Internet for general purposes (Cahaner & Malach, 2024). However, religious women apparently assume the role of change agents in their community (Novis Deutsch & Rubin, 2019), but still struggle, especially married women, with traditional everyday routines, e.g., caring for their families and avoiding the negative influence of information technologies in their homes (Nadan et al., 2019; Naor et al., 2022).

Ultra-orthodox women are key to changes that are no less than a revolution in their community. Recent data states that the rate of employment for ultra-orthodox women is currently 80% of their society; for comparison, the employment rate of secular women is 83% (Appel, 2024). Ultra-orthodox female students outnumber ultra-orthodox male students on a 2:1 ratio. Since ultra-orthodox women traditionally assume teaching positions, training ultra-orthodox teachers in colleges of education may be a means of transforming Internet routines (Bowman & Smedley, 2013; Novis Deutsch & Rubin, 2019). This conservative choice may be contradictory to progress; however, the field of education in itself holds countless opportunities for change and transformation (Zion-Waldoks, 2021).

1.3. Digital Competencies and the Ultra-Orthodox Society

The ultra-orthodox society is experiencing a wide gap in digital competencies of its members. In schools that are classified as ultra-orthodox, digital means are rare, basically nonexistent. Consequently, graduates lack basic digital literacies, incorporating sets of digital skills and competencies, required in the digital era (Cahaner & Malach, 2024; Suzin, 2025). Currently, ultra-orthodox show interest in higher education, including secular disciplines, but exhibit frustration and low self-efficacy due to a lack of digital skills, which they need to acquire as a prerequisite for academic studies (R. Cohen et al., 2019). Online components in teacher education highlight the need to transform training for this society. Hence, the goal of the current study was to examine perceptions of ultra-orthodox teachers towards their online learning within a B.Ed. training program. The research questions stemming from this goal were:

What are ultra-orthodox female B.Ed. students’ perceptions towards online learning?

What are the differences among ultra-orthodox female B.Ed. students in their perceptions towards online learning?

2. Materials and Methods

We utilized qualitative methodology as an anchor in this research, basing our results on textual records. However, we transformed the data into numbers, thereby applying quantitative measures that serve to triangulate the themes we identified; by doing this, we strengthened our findings. Hence, this research can be classified as a mixed-methods study (Hanson et al., 2005; Tashakkori & Creswell, 2007).

2.1. Participants

In total, 68 interviews were performed. The interviews were conducted by 16 ultra-orthodox female students pursuing their B.Ed. degrees in a specialized teacher education program tailored specifically for this demographic group. These interviewers were trained to conduct interviews as part of their curriculum; they were closely supervised by their lecturer. The interviewees included fellow ultra-orthodox students enrolled in various teacher education colleges, with only three being male and the remainder female. This distribution reflects the typical gender demographics of ultra-orthodox students in B.Ed. programs for teacher training. The average age of the participants was 28.18, ranging from 20 to 45 years old. Among the participants, 40 were married women and 28 were single. For many, this was their first experience with online learning, which encompassed both synchronous and asynchronous course activities during their B.Ed. studies. Most of the interviewees were reached through personal acquaintances, since cooperation within the ultra-orthodox community is mostly based on trust, attained through personal connections. Attaining the number of interviews for this study was in itself an achievement, since academia is still looked upon with some caution with regard to cooperation in research.

2.2. Research Tool

We based our data collection on interviews that were part of the requirements in a seminar on technologies in education. As mentioned, the students who conducted the interviews were extensively trained and prepared for this task, using theoretical as well as practical measures, e.g., reading materials on the one hand, and simulations on the other hand. The interviews were aimed at achieving an in-depth understanding of the underlying difficulties and challenges of ultra-orthodox higher education students regarding online learning. The interviews were of a semi-structured nature, including questions on topics such as the following: preferences of online vs. face to face courses and the reasons for this, religious aspects of learning online, and challenges of online learning in a religious setting.

2.3. Data Analysis

The interviewers recorded and subsequently transcribed each interview, focusing on the students’ views and attitudes toward online learning, particularly their educational pursuits. A methodical content analysis was carried out, employing both inductive and deductive approaches outlined by Hsieh and Shannon (2005). Hence, we looked for common themes, on one hand, and embraced outliers, as expected in qualitative research, on the other hand, thereby examining a wide scope of perceptions and opinions.

We transformed the qualitative data into quantifiable metrics to deepen our understanding by identifying statements aligned with predefined themes, and also as a means of triangulating our findings. These included statements that portrayed online learning positively, negatively, or neutrally—where the latter could not be distinctly categorized as either positive or negative. Statistical analysis tools commonly used in the social sciences were then applied to the data. Additionally, we explored variances in responses based on marital status, distinguishing between single and married participants. Classification of statements as positive/negative/neutral came from participants’ own perspectives; notwithstanding, we double-checked this classification, although it was extremely dichotomous. Consequently, reaching inter-rater agreement ensured reliability.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted after approval was granted from Levinsky College of Education’s Ethics Committee. All participants gave their consent to take part in the study. To ensure privacy, participant names and identifying details were omitted. All transcriptions could only be accessed by the authors.

3. Results

We report herewith results of our analysis, including qualitative and quantitative data. Note that this is a marginal society within the overall Israeli population, in several aspects, e.g., their relative avoidance of any type of information technology, due to their religious beliefs.

3.1. Ultra-Orthodox Female Students’ Perceptions Towards Online Learning

The content analysis conducted for this study resulted altogether in five themes, namely: technical challenges, ethical/religious challenges, academic challenges, engagement challenges, and aspects of availability. Technical challenges refer to aspects of using technical devices, usually a computer, as well as software and the Internet. These may include issues that are more common in traditional societies, such as connectivity to the Internet and ownership of devices such as a computer or a smartphone. Ethical and religious challenges include fundamental issues referring to the conventions and way of life in traditional communities, which are manifested in fear of exposure to unfit content (e.g., violence, sexual content) and content that undermines their religious beliefs. Academic challenges refer to the unique aspects of online learning compared to the traditional face-to-face lessons that students are usually confronted with. For most of these students, the courses they attended online were their first experience in this mode of learning; they referred to these courses in this study. The focus of this theme is on the efficiency and academic quality of learning online. Engagement challenges focus on the affective, social, and communicative aspects of learning online; again, for almost all students participating in the study, the online courses were their first learning experience in this mode. Availability relates to practical aspects that stem from the possibilities of online modes of learning, i.e., the possibility to learn anytime, anywhere, in class, or in groups, in a ubiquitous manner.

3.2. Themes

In the content analysis, we identified three types of statements for each theme: statements that reflected positive perceptions regarding online learning, statements that reflected negative perceptions regarding online learning, and neutral statements regarding online learning, which we could not classify as positive or negative. In the transcription analysis, we cataloged a total of 799 statements related to online learning. Among these, 374 statements (47%) were identified as positive regarding the respective themes, 367 statements (46%) were categorized as negative, and 58 statements (7%) were deemed neutral. Table 1 displays the distribution of these statements across the five identified themes.

Table 1.

Classification of the overall 799 statements regarding online learning into the five themes.

In our analysis of the statements, we noted an equilibrium between the positive and negative sentiments expressed by the participants. Significantly, 281 statements (35% of the total) addressed academic challenges, and 215 statements (27% of the total) referred to engagement issues. Interestingly, technical challenges were highlighted in only 68 statements (8% of the total), while ethical or religious concerns were mentioned in 78 statements (10% of the total).

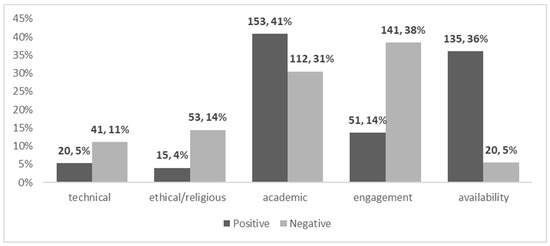

For each theme, we further analyzed the balance between positive and negative perspectives, expressing these as percentages. These findings are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Statements classified into positive vs. negative statements for each of the 5 themes. Source: Author’s own creation/work.

A chi-square test of independence was conducted to assess the relationship between the number of positive versus negative statements and the challenges identified. The outcomes of this analysis are presented in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8. In all tables, observed frequencies are presented without brackets, expected frequencies are shown in parentheses, and chi-square contributions are displayed in square brackets.

Table 2.

Chi-square values for technical vs. academic themes.

Table 3.

Chi-square values for technical vs. availability themes.

Table 4.

Chi-square values for ethical/religious vs. academic themes.

Table 5.

Chi-square values for ethical/religious vs. availability themes.

Table 6.

Chi-square values for academic vs. engagement themes.

Table 7.

Chi-square values for academic vs. availability themes.

Table 8.

Chi-square values for engagement vs. availability themes.

When examining the data exhibited in Figure 1, we see different patterns in positive vs. negative statements, according to themes. In three of the five themes, more negative than positive statements were identified: technical challenges, ethical/religious challenges, and engagement challenges. In the remaining two themes, academic challenges, and availability, more positive than negative statements were identified.

We herewith describe in detail the characteristics of the themes and illustrate with statements of the participants of the study. We first present the three themes in which we found more negative than positive statements; then we present the two themes in which we found more positive than negative statements.

3.2.1. Technical Challenges

Technical challenges comprised 41 negative statements vs. 20 positive statements, and an additional seven neutral statements; hence, there were twice as many negative statements compared to positive ones. Many of the participants encountered technical challenges as a first substantial experience in their post-schooling education, as expressed in the following statement:

“First, I had to cope with this tool called the computer. Until I started my studies at […] I hardly touched a computer… the Moodle was also a whole separate matter… Technical things that are not really connected to the learning.”(interview 5)

Various technical challenges were experienced by the students due to being unfamiliar with several digital devices and applications as follows:

“I encountered many difficulties when we suddenly did not have Internet… sometimes you connect through the phone but that also doesn’t always work. Then you have a technical problem … it’s very disruptive.”(interview 1)

This novelty in learning caused several difficulties and was considered by the students a disadvantage in their learning and even a drawback, for example:

“When I first came to the college with all the Moodle and forums, I didn’t know how to cope with it. And it’s a disadvantage that I didn’t know all these digitals… I really didn’t know how you respond in a discussion group… So, … I turned to the technical help.”(interview 24)

Despite the many problems and difficulties, positive statements were also identified; these were not expressed by digitally literate students (all students were digitally challenged). However, although most interviewees were unfamiliar with technology altogether, some of them had acknowledged the role of technology as a lever for learning and as a means for personal development, as illustrated in the following statement:

“I learned all sorts of things on the computer itself and software … it’s to learn and use it for myself not really about the topic of the course. More the technology itself and not the materials… Because all the time you go into the Moodle and you have over there written help about how to operate everything.”(interview 25)

The acknowledgment of the necessity for using technology in the digital era was a revelation for many students, who appreciated the opportunities for saving time and means by using digital documents:

“It makes it easy for us from many aspects. In terms of printing things, there is less paper and fewer printed materials.”(interview 3)

To sum up, students expressed the obvious need to use technology as a basic skill, as portrayed by the following statement:

“It’s a basic thing [technology] that is obviously what the student has to have and it’s his responsibility to come [to academia] with knowledge on it.”(interview 10)

However, this willingness to utilize technology needs to be accompanied by suitable support and training: “Technology really helps us, really makes it easier to learn, it enriches us, they just have to give us these tools so that we know how to use technology.” (interview 63)

3.2.2. Ethical/Religious Challenges

With regard to ethical/religious challenges, gaps were even larger between negative and positive statements. Approximately three times more negative statements were found, compared to positive ones (53 negative statements vs. 15 positive statements). This illustrates the fundamental importance and value of ethical and religious aspects with regard to academia and altogether. In spite of the risks from their point of view, ultra-religious students’ choice to enter academia requires dealing with technology and finding the adequate solution for these “risks”: “I have filtered Internet. At first, I was indecisive about connecting to the Internet and I couldn’t reach a conclusion about having Internet, because without it you can’t work, so I had filtered Internet.” (interview 7)

Negative statements on ethical/religious challenges included reference to either lack of infrastructure in religious homes due to religious considerations or ethical dilemmas when considering having technological means at home and when experiencing them de-facto. The following statement illustrates the hardship when a student does not have access to a computer at home:

“When we started to learn I retaliated very much regarding all the issue of the academic portal, since I did not understand why we need everything in an online way. I didn’t have Internet at home and it was very difficult to accept the fact that most assignments and all learning materials were on the Internet… at the beginning it was very hard, I had to go to …go to the public town library, I’d go to my mother in-law, to all kinds of places so I can really succeed in opening the learning materials… [till] I got used to it.”(interview 45)

In some cases, against all religious beliefs, technology was introduced to the home of the student:

“I did not have Internet [at home], the Internet I did especially for my studies …we got in our house secured Internet … and then when I completed my degree I disconnected the Internet, I had no need for it.”(interview 49)

Still, the need to welcome—sometimes unwillingly—the Internet and the perceived ambivalence was acknowledged by some of the students: “I am more open, so yes, unfortunately I brought the Internet into my home.” (interview 1)

Hence, some statements regarding ethical/religious challenges were positive, focusing on the necessity of technology for online learning:

“Because of its necessity I find in myself the strength to learn to make wise use of it…so I do leave it at home… I pray to do the right thing with it… what is the need compared to the damage, and to the usefulness.”(interview 43)

Moreover, in the following instance, while to begin with the interviewee’s statements were negative regarding ethical/religious challenges, along the interview her perceptions changed completely because of her experience:

“Now it’s simply real fun for me… suddenly I understood that online learning is very convenient.”(interview 45)

3.2.3. Engagement Challenges

Engagement in educational settings is considered crucial for meaningful learning, as illustrated in this theme, and a basic feature in fully understanding any content, especially unfamiliar content, such as in academia. With regard to engagement challenges, large gaps were evident between negative and positive statements. The following statement refers to the need for constant interaction with the lecturer and between students:

“I didn’t understand so much the assignments and I would write to the lecturer… and step by step I learned to turn to the lecturer less and less times and to try to understand on my own what they mean.”(interview 15)

Altogether 141 negative statements regarding engagement challenges were identified, vs. 51 positive statements. Negative statements included reference to lack of interaction in online modes of learning. Note that ultra-religious students are accustomed to constant interaction in a social climate, which is considered highly important in the learning process:

“I do not have any interaction with the [other] girls in an online course… the social atmosphere is very important for learning… in an online course, there is no social life.”(interview 4)

In the online mode of learning, some students who initially experienced difficulties, even thoughts about dropping out, had gradually begun to adapt to online learning:

“…At the beginning I said, OK so maybe I’ll give up and go to a college where there is no Internet… no need for Internet, because it was too hard for me… so I gradually opened the Internet, and exposed myself to it…. With time I read articles, read stuff… and today it’s different.”(interview 7)

Hence, positive statements regarding engagement challenges were also mentioned, for example, ones reflecting a different take on learning online for shy students:

“Suppose… people that are more introverts in nature… for them it’s excellent learning. They don’t have to cope and stand in front of the class or the lecturer or generate interaction with their classmates… You do have contact with the lecturer, but it’s not a verbal connection.”(interview 5)

Another statement referred to attention disorders:

“I have attention disorder so it’s easier for me to read from the computer and to understand alone than to look at the lecturer for 45 min… of the lesson. To look at the lecturer in the eyes is a bit harder.”(interview 6)

In the additional two themes, more positive than negative statements were identified: academic challenges were mentioned in 153 positive statements vs. 112 negative statements. Regarding availability, the gap between positive and negative statements was the largest: 135 positive statements vs. 20 negative statements—almost seven times more.

3.2.4. Academic Challenges

As mentioned, academic challenges accounted for 265 of the statements altogether, of which 153 were positive statements vs. 112 negative statements. These refer to challenges stemming from pedagogical aspects of online learning, which were encountered by these ultra-orthodox students for the first time. Consequently, they constantly compared it to face-to-face lessons, as illustrated in this statement:

“Regarding communication with the lecturer… I would really like to have at least one meeting with the lecturer in which she explains what’s going to be in the course and the requirements and what she expects from us.”(interview 13)

Positive statements, for example, included reference to a sense of triumph as a result of overcoming challenges of online learning, which these students are unaccustomed to:

“It made me stand up to challenges which I did not think I could overcome. In these courses there is something more varied and interesting that is “out of the box… I enjoyed feeling that it’s like to make something totally new that wasn’t there before. And it’s thanks to the various tools of technology.”(interview 39)

Some statements referred to active learning as a means of meaningful learning in the online course:

“In the online courses learning is more active… You have to learn the materials, to submit and complete the assignment, to participate in forums and discussions. So you really have to be on it.”(interview 30)

This student continues and illustrates the advantages of documentation in online courses:

“Everything is recorded… and if I wanted to hear again to pinpoint something… or if I forget details regarding what to do or if I missed a meeting then I could just go into the Internet and heard the meeting again.”(interview 30)

However, the students experienced also negative academic impacts of online courses, especially due to the need for mediation of the course contents and requirements, for example:

“I think that mediation is something very important… I need to see the teacher that if there is something not clear, you can see her straight away and ask her rather then that you’re stuck in front of the screen and pray to it that it lets you understand a bit of what’s written in it.”(interview 1)

Apparently, the need for direct communication is a very practical one to these students, academic-wise:

“It sucks that I don’t hear directly from the lecturer her demands. I want to be sure that I precisely understood what she demands and what she wants. It sucks to work a few hours on an assignment and at the end to find out that I did something else totally.”(interview 14)

Moreover, some students feel that the grades are lower in online courses, as a result of difficulties in understanding the learning materials, which harms the learning process:

“My grades in online learning are lower, I see this as a result of less understanding the learning materials… You read it again and again and you just don’t get it. For this there is nobody to make the materials simpler and explain to you, and it’s really hard for me.”(interview 7)

3.2.5. Availability

With regard to availability, we identified 135 positive statements, almost 7 times more than the number of negative statements—only 20 altogether. This indicates that a major advantage of learning online was the availability aspect of the course, portrayed in the possibilities of learning whenever it is convenient for the student.

The following statement portrays the advantage of not having to stay in the college for all the courses, but rather learning also from home:

“I think it’s very good… saving of time, also you don’t need to stay in the college for a few more hours… at the expense of the children and so on. I can do it whenever it’s convenient for me, if it’s at night when everyone has gone to sleep I open the computer and then I’m concentrated and do it when it’s accessible to me and convenient for me.”(interview 23)

Ultra-orthodox women are very busy, carrying on their shoulders the household and income issues. Many of the students are mothers to several children; hence availability of online learning and the advantage of its flexibility make it possible to pursue higher education:

“It’s important when you are a mother of children and you come home early… Of course I’d prefer to learn when my little ones are asleep… and to maneuver it with the home. Besides, it saves a lot of money.”(interview 34)

However, there were also negative implications related to availability issues, for example, ones related to self-regulation of the learning: “Sometimes you wait for the last minute, then you are under pressure. You have to be very consistent to do it on time, and there needs to be a lot of responsibility…” (interview 23)

Another interviewee supported this notion, elaborating this point:

“…demands very much from all of the girls to be together and work together… it was very difficult for us to get together as a group… Sometimes it can get to the last minute, and then everyone is in awful pressure to be on time with the required assignment and submit it on time.”(interview 35)

This student continues elaborating on the difficulties regarding expected collaborative online assignments, which forced online cooperation between students. This counterbalanced the relative advantage of learning anytime from any place:

“Some of us were responsible for the assignments, some were not present on time, and that is actually what made it hard… because we were supposed to work together as a group assignment … And also we can’t talk to the lecturer about it.”(interview 35)

Differences among ultra-orthodox female students in their perceptions towards online learning.

Following the interviewees’ statements regarding single vs. married students, with regard to availability for online learning, we examined the themes in accordance with marital status. The average age of married students was 30.8 (min. 22, max. 45), and the average age of single students was 24.4 (min. 20, max. 35). Table 9 presents frequencies and percentage of statements according to themes and marital status.

Table 9.

Classification of the overall 799 statements regarding online learning into the five themes, according to marital status.

When examining the table, some interesting data arise regarding the differences between married and single ultra-orthodox women. Regarding technical challenges, surprisingly, negative statements of married women appeared twice as much as positive statements, and those of single women appeared 4 times as much, also in favor of negative statements. However, single ultra-orthodox women altogether referred less to technical challenges. Otherwise, similar patterns of positive vs. negative statements were identified for married vs. single ultra-orthodox women.

When comparing the married and single ultra-orthodox women in our study by in-depth examination of the statements, two main issues are of concern. The first issue is related to time constraints of married women with children, who exhibit more positive statements regarding the opportunities of online learning, for example:

“My main consideration is the time and the ability to be free in the afternoon. I’m a mother of four tiny, cute kids, and God willing I do not have the possibility to go out once-twice a week in the afternoon on the hours that the kids need me so much… I’d rather… do the online assignments… in the evening after the kids fall asleep.”(interview 30, married)

Moreover, married women acknowledge the advantage of face-to-face vs. online learning for single women from the ultra-orthodox society:

“If it’s someone single, I would say to her: go study frontal, go study face-to-face. This way you’ll benefit and be wiser. But if it’s someone married with children who only wants to complete her degree and carry on with her work, I would say to her that it’s great, that this [online courses] is the best place for her.”(interview 4, married)

One of the single students referred to the balance between online and face-to-face courses, stating that the reasons should not necessarily be the marital status:

“I would advise… to take… blended… in areas she feels less competent to take face-to-face learning, because the response of the lecturer that’s in front of you is import. Then in a subject that she feels… need of more help, she should take face-to-face lessons… it’s always good to have the courses you can manage the time… Because anyway we are all working people, who cope with stuff in addition to studying, we have personal lives… you have family obligations… This is why I would recommend to take online studying but the right amount.”(interview 5, single)

The second issue focuses on ethical concerns, mainly of married women, regarding the dilemma of advantages vs. possible negative influence of the Internet on their children. They acknowledge the dangers of exposure to unwanted content via the Internet. This dilemma is portrayed even by single women who imagine their lives in the future as opposed to their present situation:

“I’m principally ultra-orthodox, but regarding the Internet I’m not a mother of children so I’m less fearful of having Interment at home… possibly if I had children today and a husband I would consider whether to have Internet or do filtering. But nowadays as a student I can say that it’s a tool that helps me very-very much even as an ultra-orthodox. There are a lot of things I need information about, so I log on to the Internet and find out about them.”(interview 24, single)

One of the married women expressed her concerns as a mother of young children, anticipating future difficulties as the children grow up:

“I see the advantages; I also see the disadvantages. Not right now, because I feel that the children are very little. I do not have to cope with this, but I don’t want open Internet, also for me, also for my kids.”(interview 43, married)

Another married woman elaborated on the ambivalence towards the Internet: on one hand, the “corrupt” nature of some of its content, and on the other hand, the advantage of studying at home:

“I am against bringing the Internet into my home… the Internet has many things that can knock you down religious-wise… I won’t have Internet in my home. Period. I’m totally against it. However, it’s very convenient as a woman who wants to have children and to invest in them… so it’s very important to me to be at home as much as I can. The online course allows me to be at home and take care of them.”(interview 4, married)

Another single ultra-orthodox student supports this notion of the difference between being married with children—note that these women have children normally within their first year of marriage—and adds the need to follow tradition by avoiding unsuitable content—for the children and for the husband:

“Today I’m single and I have very high self-discipline, and I really fear The Holy One, Blessed He, and I will not enter places I’m forbidden [on the Internet]. But say if I was a mother of children or a wife to a husband, I would really fear having Internet in my home although I’m a student, because above all I would not know what my kids or my husband would be exposed to. I do not see in this a thing that is so good.”(interview 5, single)

The following quote expresses vividly the dilemma of married ultra-orthodox mothers who as students are exposed to the “wonders” of technology:

“I’m not against the computer… I think you should let the kids be exposed to the computer, otherwise they will at some point learn from someone else. The computer today is a very important tool. My kids play games on the computer and many other things they do on the computer. Of course, everything is under supervision. Anyway, in my opinion, the computer is very much needed especially today in this generation in which technology is so developed.”(interview 33, married)

3.3. Summary of Findings

Findings demonstrate the complexity of utilizing online learning among ultra-orthodox teacher education students in a twofold manner: personally and community-wise. On a personal level, the vast majority of statements were related to the problematic nature of the Internet from their own point of view: their worries about the corrupt nature of content (mostly not being monitored), possibly reaching their families and young children. Also, the lack of a personal acquaintance with the teacher educators was an obstacle. On the community level, their reputation may be compromised as a result of their exposure to forbidden secular materials and devices. To sum up, all ultra-orthodox students acknowledge the importance of technology and its role in their studies in particular, but also in their lives altogether. Their concerns are related to the disruptive nature of technology and the difficulty in controlling and supervising its usage.

4. Discussion, Conclusions, and Implications

4.1. Discussion

This study aims to explore the attitudes of ultra-orthodox higher education students towards online courses. Participants were enrolled in a secular college of education; however, they were part of a specialized program specifically designed for women pursuing their B.Ed. degrees. These programs have become popular among the ultra-orthodox society, as a lever for social inclusion and improving their means of living. However, in many cases their starting point is lower than that of the general society, due to lack of comprehensive core studies and prior conditions that include restrictions with regard to technology utilization (Novis Deutsch & Rubin, 2019). Still, penetration of technology into the ultra-religious scenery is unavoidable, encompassing several fields of their lives (Mishol-Shauli et al., 2019).

The themes that were identified in our study reflect a reference to technological aspects, academic aspects, and pedagogical aspects of learning in an online mode. These may relate to technological, pedagogical, and content components of the TPACK (technology, pedagogy, and content knowledge) model. This well-known and accepted model incorporates the meaning of knowledge in the three aspects found in our study, emphasizing the role of technology and its significance for everyday life, including in teaching and learning (Kontkanen et al., 2016) and in content creation and presentation (Luik et al., 2018). The academic theme, which relates to content; the engagement theme, which refers to pedagogy; and the availability theme are all demonstrated in technology implementation in education. Hence, it may be even more relevant when examining the complexity of a religious way of life, where there are attempts to overcome conflicts of utilizing technology.

The unique ultra-orthodox setting also explains the relatively minor reference to technological challenges, much less than expected (Mishol-Shauli et al., 2019). It seems that participants acknowledged the significance and the unique contribution of online learning and training as educators; this, in turn, may assist in their future teaching, whether online or with regard to positive attitudes towards technology and consequently better utilization and integration of ICT in their future teaching. Hence, their training should focus more on pedagogical aspects of integrating technology in teaching diverse content (Luik et al., 2018).

Furthermore, online communication involves less formal interaction between participants and clashes with the more formal, respectful face-to-face encounters performed in the ultra-orthodox community (Forkosh-Baruch & Gadot, 2022). Student communication was said to be better when conducted online, leading to more efficient, convenient, and productive collaboration. Perhaps online learning is considered more accessible than face-to-face learning. The interaction between peers also aids students in managing their workload, which is reported to be higher than in face-to-face courses. This overload is reported also by the general student population (James et al., 2021).

Contrary to expectations, technical challenges were infrequently cited by the study participants, a finding that may be attributed to their infrequent use of information and communication technologies altogether in daily life (Y. Cohen, 2017). Nevertheless, the number of negative statements was twice that of positive ones. These difficulties are documented in research focusing on the ultra-orthodox community, and impact their integration into higher education and the workforce (Kay & Levine, 2019; Kalagy, 2020). During the interviews, however, a shift in the participants’ attitudes towards the technical aspects of online learning was documented. They expressed initial difficulties but also acknowledged a growing need to adapt to and appreciate online platforms as viable educational environments. Despite these technical challenges, they did not impede academic performance, as reflected by the relatively few statements concerning technical issues. The implications of such a shift in attitudes and perceptions regarding technology utilization may positively impact actual use of technology for professional development of the adult ultra-orthodox society altogether (Cahaner & Malach, 2024).

Unexpectedly, ethical and religious challenges were mentioned less frequently than other identified challenges, such as academic and engagement issues and access problems. One might anticipate these issues to be more prevalent within the ultra-religious community (Shomron & David, 2022). We assume that the very act of engaging with higher education suggests a degree of openness to external influences, which does not necessarily compromise their religious practices or beliefs (Braun-Lewensohn & Kalagy, 2019). This involvement reflects their professional goals and their self-view as part of the broader Israeli society (Golan & Fehl, 2020). While participation in online education might lead to unintended, undesired consequences, particularly for married women with familial responsibilities, they manage these threats by establishing routines that accommodate their religious lifestyle, such as working online at night. Nevertheless, there remains a persistent concern about exposure to inappropriate content, which could lead to religious confusion or spiritual decline (Nadan et al., 2019). Consequently, some opt to study in public settings like libraries, relatives’ homes, or workplaces to mitigate this issue, often choosing to download materials and work offline to limit internet usage, which might seem to instructors as a lack of engagement. This can lead instructors, often from outside the ultra-orthodox community, to misinterpret reduced online presence as lack of involvement in the course.

4.2. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Notwithstanding, this study is not without limitations. First, the interviewees were female since academic programs for ultra-orthodox students separate women from men for religious reasons. Therefore, male students were not involved in this study. Moreover, these female students studied in a program designated for them. Hence, we recommend a separate study focusing on ultra-orthodox male students and possibly comparing the two studies. We also encourage similar research that includes ultra-orthodox participants, whether male or female, who study, in general, programs rather than separate ones.

Moreover, since the interviewers were female, the situation in which they would interview men is unacceptable in the ultra-orthodox society. Therefore, the study excluded ultra-orthodox male participants. Since ultra-orthodox female students study mostly education, the vast majority of participants in the study were female students studying towards their B.Ed. degree; hence, participants from other disciplines were rare. Consequently, conducting additional research that focuses on ultra-orthodox male students may fill these gaps.

In terms of data collection, while interviewers were students from ultra-orthodox society who were familiar with this way of life, they were not experts in qualitative data collection through interviews. Still, their syllabus included the topic of qualitative research, and specifically, they received training on data collection through interviews. Training ultra-orthodox male students to do the same may lead to similar results.

4.3. Recommendations for Practice

Following the results of the current study and its conclusions, recommendations may assist in further developing evidence-based programs for female ultra-orthodox students, and possibly for all ultra-orthodox students, who wish to enroll in higher education institutions. Since information and communication technologies are a major component of modern life, and following COVID-19, academia is rethinking online education in higher education institutions. However, utilizing online learning for ultra-orthodox students is more complex compared to the general population. Still, since most participants agreed that the pros are greater than the cons, and valued online courses, this mode of learning should be encouraged.

Adapting online courses in higher education institutions for ultra-orthodox students should be approached from two perspectives. First, the mere fact that these students prefer, to some extent, online learning reflects a shift within the ultra-orthodox society towards the general population. This illustrates the acknowledgment of the importance of higher education in the digital era. However, they express their reservations regarding unsuitable content. Hence, faculty should be aware of these feelings, by adapting learning content and modes of learning to these populations, who are accustomed to separate face-to-face, education. Traditional characteristics of this society should be considered, thereby supporting their assimilation into society at large.

Secondly, members of the ultra-orthodox society lack sufficient technological skills, which may impact their motivation to study online and prevent full engagement in the courses. While they may benefit from online education, this mode of learning requires openness to a more modern society. Faculty should address this issue concurrently in terms of technological skills and technological infrastructure. Technological skills should be practiced to ensure fluency in online learning and avoid frustration; training should be conducted by the higher education institution. In addition, higher education institutions should supply these students with devices and adequate infrastructure that are available for learning. These may be located in community centers or the institutions themselves since some ultra-orthodox students are forbidden to have these devices at home. The institution should consider filtering content in order to respect the ultra-orthodox way of life. Since the study reported herewith was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, a follow-up post-pandemic study would possibly lead to additional insights.

Our study focuses on students from the ultra-orthodox community, highlighting its status as a distinctive example of a marginalized group. The insights derived from our research may be applicable to other similar communities. We recommend the implementation of case studies on additional traditional marginalized groups, such as refugees in European countries. Such studies could enhance our understanding of their educational needs and behaviors, facilitate broader quantitative research, and ultimately aid in their assimilation into mainstream society as productive members.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G. and A.F.-B.; methodology, R.G. and A.F.-B.; validation, R.G. and A.F.-B.; formal analysis, R.G. and A.F.-B.; investigation, R.G. and A.F.-B.; resources, R.G.; writing—R.G. and A.F.-B.; writing—review and editing, R.G. and A.F.-B.; supervision, R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee for Research of Levinsky College of Education (Approval Number: 2018102401; Approval Date: 4 November 2018).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as datasets were generated for the current study in the Hebrew language and are protected due to privacy issues referring to the specific characteristics of the ultra-orthodox society.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Appel, G. (2024). The work market in Israel 2024 Israeli ministry of economics and industry. [Hebrew]. Available online: https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/dynamiccollectorresultitem/employment-report-2024/he/strategy_annual-employment-report24-full.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Aslan, A. (2021). Problem-based learning in live online classes: Learning achievement, problem-solving skill, communication skill, and interaction. Computers & Education, 171, 104237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondheim, M. (2015). The Jewish communication tradition and its encounters with (the) new media. In H. A. Campbell (Ed.), Digital Judaism: Jewish negotiations with digital media and culture (pp. 16–39). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bonk, C. J., & Zhu, M. (2024). On the trail of self-directed online learners. ECNU Review of Education, 7(2), 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, N. A., & Smedley, C. T. (2013). The forgotten minority: Examining religious affiliation and university satisfaction. Higher Education, 65(6), 745–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Lewensohn, O., & Kalagy, T. (2019). Between the inside and the outside world: Coping of Ultra-Orthodox individuals with their work environment after academic studies. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(5), 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cahaner, L., & Malach, G. (2024). Statistical report on ultra-orthodox society in Israel. The Israel Democracy Institute. Available online: https://en.idi.org.il/haredi/2024/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Cebi, A., Özdemir, T. B., Reisoğlu, İ., & Colak, C. (2022). From digital competences to technology integration: Re-formation of pre-service teachers’ knowledge and understanding. International Journal of Educational Research, 113, 101965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R., Rahimi, I., & Zilka, G. C. (2019). Self-efficacy, challenge, threat and motivation in virtual and blended courses on multicultural campuses. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 16, 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y. (2017). The media challenge to Haredi rabbinic authority in Israel. ESSACHESS-Journal for Communication Studies, 10(02), 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, E., & Selivansky, E. O. (2019). Adapting Israel’s education system for the challenges of the 21st century: Policy paper 130. The Israel Democracy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Forkosh-Baruch, A. (2018). Preparing pre-service teachers to transform education with Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). In J. Voogt, G. Knezek, R. Christensen, & K. W. Lai (Eds.), Handbook of information technology in primary and secondary education (2nd ed., pp. 415–432). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Forkosh Baruch, A., & Gadot, R. (2022, June). Online Learning and Ultra-Orthodox teacher education students–do they align? In EdMedia+ innovate learning (pp. 247–254). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). [Google Scholar]

- Genut, S., & Kolikant, Y. B. D. (2017). Undergraduate Haredi students studying computer science: Is their prior education merely a barrier? Interdisciplinary Journal of e-Skills and Lifelong Learning, 13, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Golan, O., & Fehl, E. (2020). Legitimizing academic knowledge in religious bounded communities: Jewish ultra-orthodox students in Israeli higher education. International Journal of Educational Research, 102, 101609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q., Zeng, Q., & Zhang, L. (2023). What social factors influence learners’ continuous intention in online learning? A social presence perspective. Information Technology & People, 36(3), 1076–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, W. E., Creswell, J. W., Clark, V. L. P., Petska, K. S., & Creswell, J. D. (2005). Mixed methods research designs in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, T. L., Zhang, J., Li, H., Ziegelmayer, J. L., & Villacis-Calderon, E. D. (2021). The moderating effect of technology overload on the ability of online learning to meet students’ basic psychological needs. Information Technology & People, 35(4), 1364–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalagy, T. (2020). “Enclave in transition”: Ways of coping of academics from ultra-orthodox (haredim) minority group with challenges of integration into the workforce. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalagy, T., & Braun-Lewensohn, O. (2019). Agency of preservation or change: Ultra-Orthodox educated women in the field of employment. Community, Work & Family, 22(2), 229–250. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, A., & Levine, L. (2019). Offline: The possible effects of Internet-related behavior on work values, expectations, & behavior among Ultra-Orthodox millennials. The Journal of Social Psychology, 159(2), 210–224. [Google Scholar]

- Kontkanen, S., Dillon, P., Valtonen, T., Renkola, S., Vesisenaho, M., & Väisänen, P. (2016). Pre-service teachers’ experiences of ICT in daily life and in educational contexts and their proto-technological pedagogical knowledge. Education and Information Technologies, 21, 919–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körkkö, M., Lutovac, S., & Korte, S. M. (2024). The sense of inadequacy and uncertainty arising from teacher work: Perspectives of pre-and in-service teachers. International Journal of Educational Research, 127, 102410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luik, P., Taimalu, M., & Suviste, R. (2018). Perceptions of technological, pedagogical and content knowledge (TPACK) among pre-service teachers in Estonia. Education and Information Technologies, 23, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meoded, R., & BenDavid-Hadar, I. (2025). Education policy in culturally diverse countries: The case of ultra-Orthodox schools in Israel. Research Papers in Education, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishol-Shauli, N., Shacham, M., & Golan, O. (2019). ICTs in religious communities: Communal and domestic integration of new media among Jewish ultra-orthodoxy in Israel. In Y. Kali, A. Baram-Tsabari, & A. Schejter (Eds.), Learning in a networked society. Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning Series (CULS, Volume 17). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadan, Y., Gemara, N., Keesing, R., Bamberger, E., Roer-Strier, D., & Korbin, J. (2019). ‘Spiritual risk’: A parental perception of risk for children in the ultra-orthodox Jewish community. The British Journal of Social Work, 49(5), 1198–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naor, M., Pinto, G. D., Davidov, P., Benaroch, J., & Kivel, A. (2022). Inclusion of ultra-orthodox students in higher education: A case study about women seminary in the engineering college of Jerusalem. Education Sciences, 12(2), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neriya-Ben Shahar, R. (2017). Negotiating agency: Amish and ultra-Orthodox women’s responses to the Internet. New Media & Society, 19(1), 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Novis Deutsch, N., & Rubin, O. (2019). Ultra-Orthodox women pursuing higher education: Motivations and challenges. Studies in Higher Education, 44(9), 1519–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, M. K., & Dallas, K. B. (2017). A collaborative approach to implementing 21st century skills in a high school senior research class. Education Libraries, 33(1), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Paşa, D., Hursen, C., & Keser, H. (2022). Determining teacher candidates’ levels of twenty-first century learner and teacher skills use. Education and Information Technologies, 27, 11537–11563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, F. (2018). On the issues of digital competence in educational contexts—A review of the literature. Education and Information Technologies, 23, 1005–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomron, B., & David, Y. (2022). Protecting the community: How digital media promotes safer behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic in authoritarian communities—A case study of the ultra-Orthodox community in Israel. New Media & Society, 26, 1484–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzin, A. (2025). Modern ultra-orthodoxy? A critical reassessment. Journal of Modern Jewish Studies, 24, 393–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taragin-Zeller, L., & Stadler, N. (2022). Religion in contemporary Israel: Haredi varieties. In G. Ben-Porat, Y. Feniger, D. Filc, P. Kabalo, & J. Mirsky (Eds.), Routledge handbook on contemporary Israel (pp. 274–286). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori, A., & Creswell, J. W. (2007). Editorial: The new era of mixed methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J., Aesaert, K., Pynoo, B., van Braak, J., Fraeyman, N., & Erstad, O. (2017). Developing a validated instrument to measure preservice teachers’ ICT competencies: Meeting the demands of the 21st century. British Journal of Educational Technology, 48(2), 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zion-Waldoks, T. (2021). The “tempered radical” revolution: Multifocal strategies of religious-zionist feminism in israel. Religions, 12(8), 628–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).