Multimodal Writing in Multilingual Space

Abstract

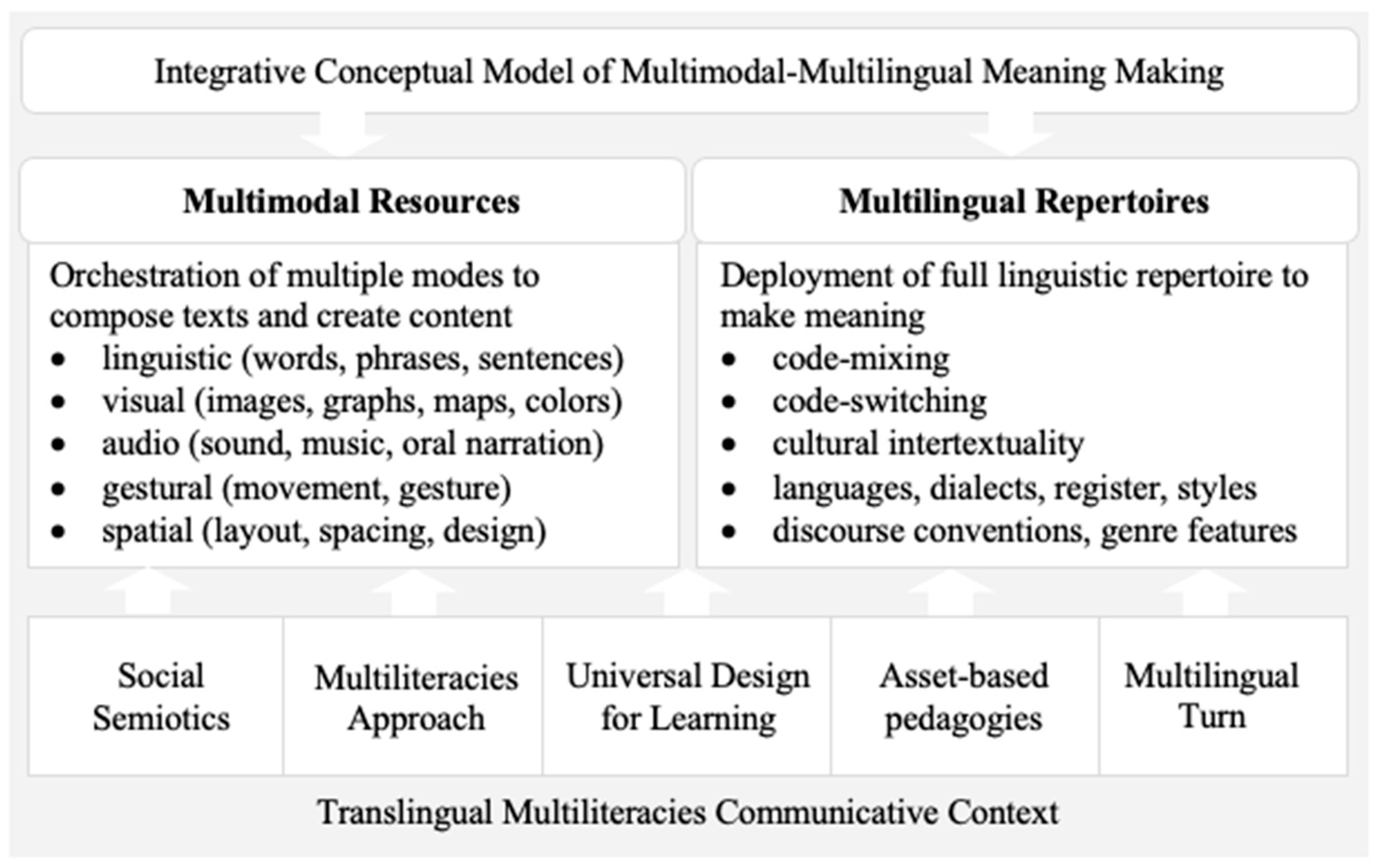

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations and Research Overview

2.1. Multimodality and Digital Multimodal Composition (DMC)

2.2. Multilingualism and Translanguaging Practice

2.3. The Intersection of Multimodality and Multilingualism

3. Pedagogical Implications in Contemporary Teaching and Learning

3.1. Toward a Multimodal-Multilingual Pedagogical Ethos

3.2. Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Practices

3.3. Culturally Sustaining Systemic Functional Linguistics

3.4. Shared Responsibility for Educational Equity

4. Practical Strategies and Classroom Implementation

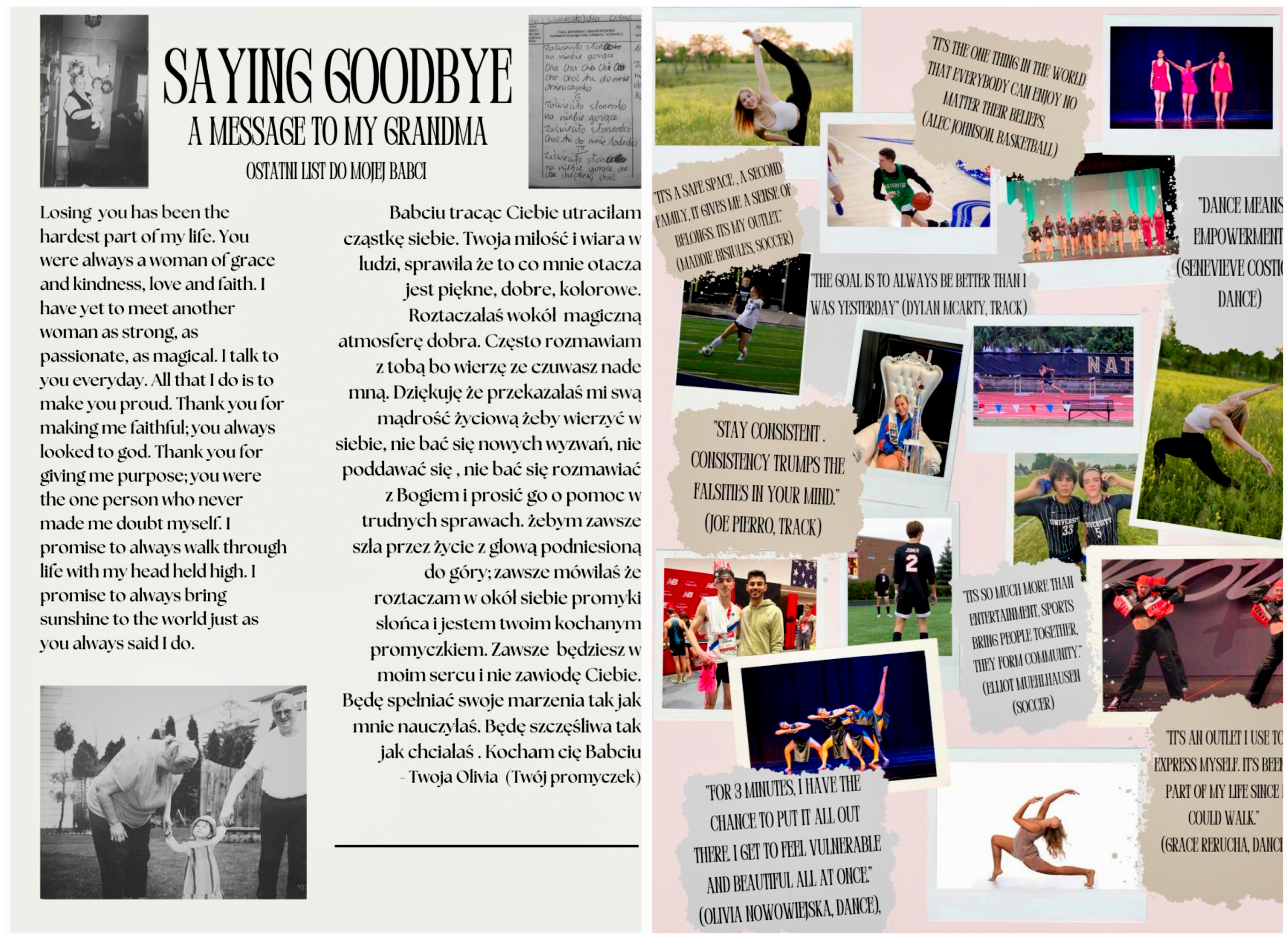

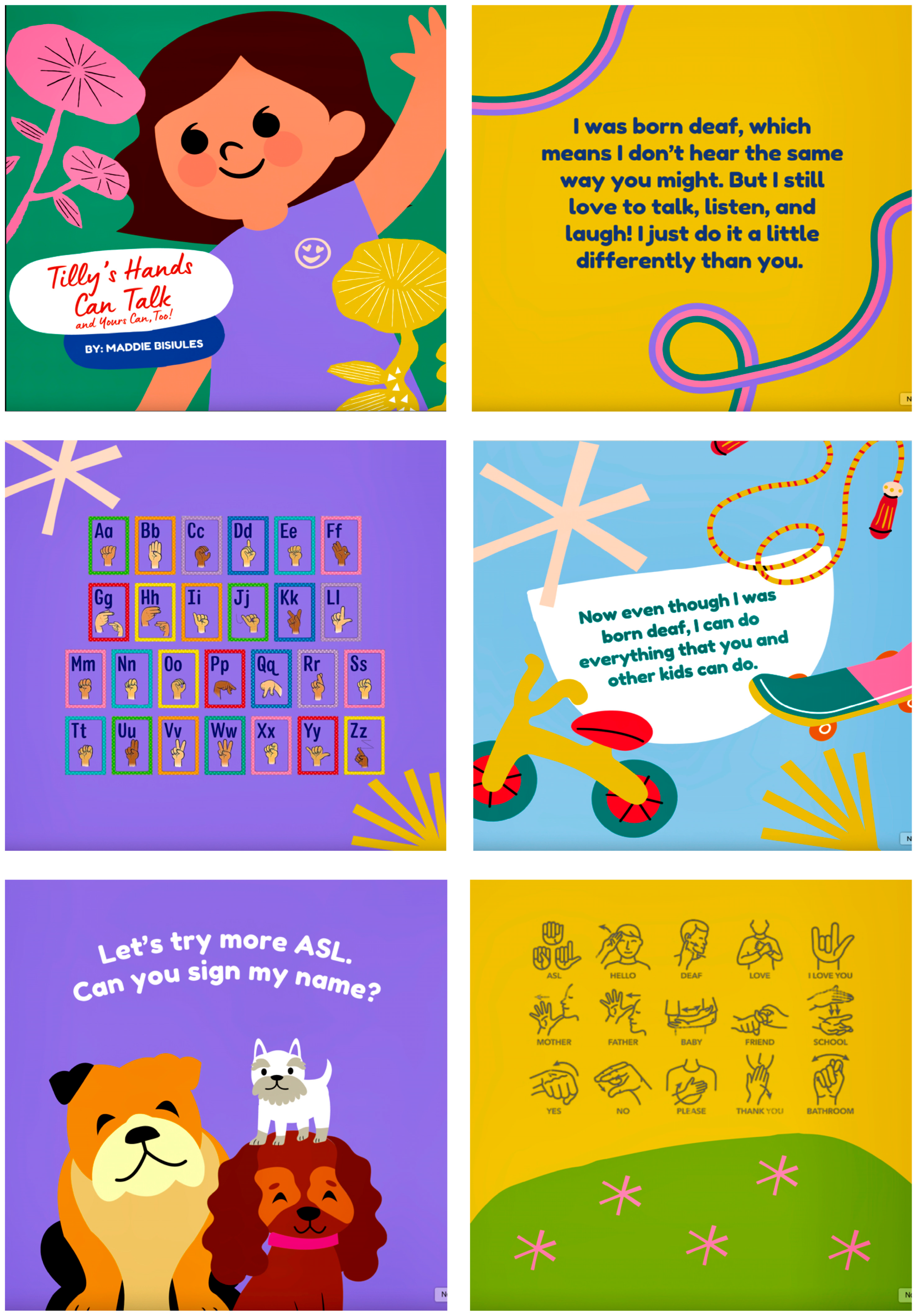

4.1. Diversity of Voices, Texts, and Assignments

- Create a space for multiple languages and semiotic modes in both teaching and student expression, welcoming multilingual and multimodal meaning-making as valid and valuable means of communication.

- Broaden curricular content by intentionally including authors, speakers, content creators, and artists from a range of cultural and linguistic backgrounds and by integrating varied genres.

- Design learning experiences that promote critical inquiry, engaging students to examine how language and representation relate to power, identity, and inclusion.

- Build reflective practices into instruction, guiding students to consider how they use different modes and languages to construct meaning and express their perspective in different contexts.

4.2. Centering Student Agency, Voice, and Ownership

- Provide students with an opportunity to choose topics, modes of expression, and project formats that promote the pursuit of inquiries that reflect their identities, interests, and lived experiences.

- Design open-ended assignments that have multiple pathways, giving students the flexibility and freedom to determine how they want to approach the task.

- Invite students into curricular decisions by co-creating class norms and writing assignments and assessment criteria. These practices signal to students that their voices matter in shaping their own learning experience.

- Support metacognitive reflections through journals, check-ins, and reflections to help students track their growth, articulate their learning goals, and take ownership of their creative and intellectual process.

- Create opportunities for students to draw from their cultural, linguistic, and experiential backgrounds as sources of insight, knowledge, and authority.

4.3. Fostering Creativity and Criticality

- Integrate inquiry-based learning by posing essential, open-ended questions that ask students to investigate real-world issues, challenge dominant narratives, and reflex on their positionalities and language practices.

- Provide models of creative–critical texts and multimodal works that blend genres, modes, and languages to inspire students and expand their understanding of what academic work can look and feel like.

- Build in opportunities for peer dialogue and collaborative meaning-making, where students can share drafts, exchange feedback, and reflect critically on both their creative choices and their rhetorical impacts.

- Prompt students to interrogate linguistic, cultural, and multimodal representation by analyzing how different voices, languages, dialects, and sign systems are privileged or marginalized across communicative contexts.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexander, J., & Rhodes, J. (2014). On multimodality: New media in composition studies. Conference on College Composition and Communication/National Council of Teachers of English NCTE. [Google Scholar]

- Alim, S. H. (2005). Critical language awareness in the United States: Revisiting issues and revising pedagogies in a resegregated society. Educational Researcher, 34(7), 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Masaeed, K. (2020). Translanguaging in L2 Arabic study abroad: Beyond monolingual practices in institutional talk. The Modern Language Journal, 104, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, M. S. (2012). The reflexive imperative in late modernity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bazerman, C. (2016). What do sociocultural studies of writing tell us about learning to write? In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (2nd ed., pp. 11–23). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bazerman, C., Graham, S., Applebee, A. N., Matsuda, P. K., Berninger, V. W., Murphy, S., Brandt, D., Rowe, D. W., & Schleppegrell, M. (2017). Taking the long view on writing development. Research in the Teaching of English, 51(3), 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, R., Newell, G. E., & VanDerHeide, J. (2016). A sociocultural perspective of writing development: Toward an agenda for classroom research on students’ use of social practices. In C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (2nd ed., pp. 11–23). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belcher, D. D. (2017). On becoming facilitators of multimodal composing and digital design. Journal of Second Language Writing, 38, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezemer, J., & Kress, G. (2016). Multimodality, learning and communication: A social semiotic frame. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan, M., & King, J. M. (2011). Classroom remix: Patterns of pedagogy in techno-literacies poetry unit. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 55(2), 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canagarajah, S. (2002). Multilingual writers and the academic community: Towards a critical relationship. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 1, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanave, C. P. (2017). Controversies in second language instruction: Dilemmas and decisions in research and instruction (2nd ed). University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Charamba, E. (2023). Translanguaging as bona fide practice in a multilingual South African science classroom. International Review of Education, 69, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K. C. K., & Tai, K. W. H. (2025). Cross-curricular connection in collaborative digital multimodal composing process: Insights from translanguaging and transpositioning perspectives. Language and Education, 39(5), 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimasko, T., & Shin, D. (2017). Resemiotization and authorial agency in an L2 writing classroom. Written Communication, 34(4), 387–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M., Ell, F., Grudnoff, L., Haigh, M., Hill, M., & Ludlow, L. (2016). Initial teacher education: What does it take to put equity at the center? Teaching and Teacher Education, 57, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2009). Multiliteracies: New literacies, new learning. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 4(3), 164–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2015). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Learning by design. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Decristan, J., Bertram, V., Reitenbach, V., Schneider, K. M., & Rauch, D. P. (2024). Translanguaging in today’s multilingual classes—Students’ perspectives of classroom management and classroom climate. Teaching and Teacher Education, 139, 104437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeström, Y. (2015). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., Flores, N., Seltzer, K., Wei, L., Otheguy, R., & Rosa, J. (2021). Rejecting abyssal thinking in the language and education of racialized bilinguals: A manifesto. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 18(3), 203–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O., & Kleifgen, J. A. (2018). Educating emergent bilinguals: Policies, programs, and practices for English learners (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., & Kleyn, T. (Eds.). (2016). Translanguaging with multilingual students: Learning from classroom moments (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism, and education. Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistics. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. St. Martin’s Griffin. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, S. (2018). A revised writer(s)-within-community model of writing. Educational Psychologist, 53(4), 258–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groundwater-Smith, S., Ewing, R., & Le Cornu, R. (2011). Teaching: Challenges and dilemmas. Cengage. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1994). Introduction to functional grammar (2nd ed.). Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Hamman-Ortiz, L., Dougherty, C., Tian, Z., Palmer, D., & Poza, L. (2025). Translanguaging at school: A systematic review of U.S. PK-12 translanguaging research. System, 129, 103594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, Z. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, R., & Burke, K. (2020). Culturally sustaining systemic functional linguistics: Embodied inquiry with multilingual youth. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, R., & Shin, D. (2018). Multimodal and community-based literacies: Agentive bilingual learners in elementary school. In G. Onchwari, & S. Keengwe (Eds.), Handbook of research on pedagogies and cultural considerations for young English language learners (pp. 217–238). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, M. R., & Mori, J. (2018). Considering ‘Trans-’ perspectives in language theories and practices. Applied Linguistics, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepple, E., Sockhill, M., Tan, A., & Alford, J. (2014). Multiliteracies pedagogy: Creating claymations with adolescent, post-beginning English language learners. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 58(3), 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Garcia, M., Schleppegrell, M. J., Sobh, H., & Monte-Sano, C. (2023). The translanguaging school. Phi Delta Kappan, 105(2), 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W. Y. J. (2022). The construction of translanguaging space through digital multimodal composing: A case study of students’ creation of instructional videos. Journal of English Academic Purposes, 58, 101134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, R., & Kress, G. (1998). Social semiotics. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L. (2023). Multilingual youths’ digital activism through multimodal composing in the post-pandemic era. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawafha, H., & Al Masaeed, K. (2023). Multidialectal and multilingual translanguaging in L2 Arabic classrooms: Teachers’ beliefs vs. actual practices. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1060196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, G. (2000). Design and transformation: New theories of meaning. In B. Cope, & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures (pp. 153–161). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse: The modes and media of contemporary communication. Arnold Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, J., Maamuujav, U., & Collins, P. (2021). Multiple utilities of infographics in undergraduate students’ process-based writing. Writing and Pedagogy, 12, 369–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, W., & Yu, B. (2011). First language and target language in the foreign language classroom. Language Teaching, 44(1), 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn Brownlee, J. L., Bourke, T., Rowan, L., Ryan, M., Churchward, P., Walker, S., L’Estrange, L., Berge, A., & Johansson, E. (2022). How epistemic reflexivity enables teacher educators’ teaching for diversity: Exploring a pedagogical framework for critical thinking. British Educational Research Journal, 48, 684–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunsford, A. A. (2006). Writing, technologies, and the fifth canon. Computer and Composition, 23, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutkewitte, C. (2014). An introduction to multimodal composition: Theory and practice. In C. Lutkewitte (Ed.), Multimodal composition: A critical sourcebook. Bedford St. Martin’s. [Google Scholar]

- May, S. (2014). Introducing the multilingual turn. In S. May (Ed.), The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and bilingual education (pp. 1–6). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mirra, N., & Garcia, A. (2017). Civic participation reimagined: Youth inter- rogation and innovation in the multimodal public sphere. Review of Research in Education, 41(1), 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, B. (2018). Exploring multimodal writing in secondary English classrooms: A literature review. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 17(4), 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeri, J. (2012). Remixing composition: A history of multimodal writing pedagogy. Southern Illinois University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, D., & Alim, S. H. (2014). What are we seeking to sustain through culturally sustaining pedagogy? A loving critique forward. Harvard Educational Review, 84, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, D., & Alim, S. H. (2017). Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Selfe, C. L. (2004). Toward new media texts: Taking up the challenges of visual literacy. In A. F. Wysocki, J. Johnson-Eilola, C. L. Selfe, & G. Sirc (Eds.), Writing new media: Theory and applications for expanding the teaching of composition (pp. 67–110). Utah State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Selfe, C. L. (2009). The movement of air, the breath of meaning: Aurality and multimodal composing. College Composition and Communication, 60, 616–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seltzer, K., Johnson, S., & García, O. (2025). The translanguaging classroom: Leveraging student bilingualism for learning (2nd ed.). Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co., Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, R. P. (2018). Digital writing, multimodality, and learning transfer: Crafting connections between composition and online composing. Computers and Composition, 48, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D., Cimasko, T., & Yi, Y. (2020). Development of metalanguage for multimodal composing: A case study of an L2 writer’s design of multimedia texts. Journal of Second Language Writing, 47, 100714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivers, J., Levenson, C., & Tan, M. (2017). Visual literacy, creativity and the teaching of argument. Learning Disabilities, 15(1), 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. E., Pacheco, M. B., & de Almeida, C. R. (2017). Multimodal codemeshing: Bilingual adolescents’ processes composing across modes and languages. Journal of Second Language Writing, 36, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutrisno, D. B. (2023). Multilingualism & translanguaging: A review of translanguaging practices in the linguistically diverse Indonesian EFL classrooms. Journal of Languages and Language Teaching, 11(3), 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayoshi, P., & Selfe, C. L. (2007). Thinking about multimodality. In C. I. Selfe (Ed.), Multimodal composition: Resources for teachers (pp. 1–12). Hampton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ticheloven, A., Blom, E., Leseman, P., & McMonagle, S. (2019). Translanguaging challenges in multilingual classrooms: Scholar, teacher and student perspectives. International Journal of Multilingualism, 18(3), 491–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unsworth, L., & Mills, K. A. (2020). English language teaching of attitude and emotion in digital multimodal composition. Journal of Second Language Writing, 47, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing social semiotics. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, S., & García, O. (2017). Translanguaging. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-181 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Vogel, S., & García, O. (2025). Translanguaging: Leveraging theoretical shifts toward social change. In C. A. Chapelle, & D. Gabryś-Barker (Eds.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistic. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. (2024). Digital multimodal composing as a translanguaging space: Understanding students’ initial experiences and challenges. Chinese Language and Discourse, 15(2), 164–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L. (2018). Translanguaging as a practical theory of language. Applied Linguistics, 39(1), 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L. (2022). Translanguaging as a method. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics, 1(3), 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L., & Lee, T. K. (2024). Transpositioning: Translanguaging and the liquidity of identity. Applied Linguistics, 45, 873–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C. (1994). An evaluation of teaching and learning methods in the context of secondary education [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Bangor]. [Google Scholar]

- Yancey, K. B. (2004). Made not only in words: Composition in a new key. College Composition and Communication, 56(2), 297–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H. (2024). A window into multilingual students’ worlds: Using multimodal writing to support writing growth. The Reading Teacher, 78(2), 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X., & Vanek, N. (2017). Facilitative effects of learner-directed codeswitching: Evidence from Chinese learners of English. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 20(7), 773–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maamuujav, U. Multimodal Writing in Multilingual Space. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111446

Maamuujav U. Multimodal Writing in Multilingual Space. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111446

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaamuujav, Undarmaa. 2025. "Multimodal Writing in Multilingual Space" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111446

APA StyleMaamuujav, U. (2025). Multimodal Writing in Multilingual Space. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1446. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111446