Abstract

This study explores a six-month professional development program implemented in four schools offering prevocational education, a group often overlooked in literacy research. Over six months, teachers participated in structured training aimed at improving their competence in teaching reading and promoting students’ reading motivation. The program responded to international concerns about declining literacy and reading motivation among adolescents in vocational tracks. Data from pre- and post-program semi-structured group interviews were thematically analyzed to identify shifts in teachers’ knowledge and beliefs. Two key findings emerged. First, most schools showed noticeable growth in teachers’ understanding of reading comprehension and its instruction and evolving beliefs. Second, teachers continued to struggle with how to promote reading motivation both before and after the program, indicating a need for more targeted support in this area. These results highlight the importance of ongoing professional development focusing on both instructional strategies and motivational practices.

1. Introduction

Reading is a fundamental skill that underpins educational success and informed participation in society. In today’s increasingly digitized and text-rich society, strong reading comprehension skills are essential not only for educational achievement across disciplines but also for effective engagement in daily life (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2019). In parallel, motivation to read, defined as the willingness and desire to engage with texts (De Naeghel & Van Keer, 2013; Wigfield et al., 2016), has been consistently linked to both educational and societal achievements (Schiefele et al., 2012). Research highlights a dynamic interplay between cognitive processes, such as inference-making and information integration, and motivational factors that sustain engagement during reading (Kintsch, 2005; Van Ammel et al., 2021b; van den Broek & Helder, 2017). Increasingly, studies ask for teaching approaches that address both reading comprehension and motivation together (Troyer et al., 2019; Van Ammel et al., 2021b).

However, recent data from the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) underscore troubling global trends in reading literacy. In particular, results from Flanders, the Dutch-speaking region of Belgium, reveal a significant decline in reading proficiency among 15-year-olds; nearly one in four students performs below the basic proficiency level, lacking the skills necessary for successfully completing functional reading tasks in everyday life (De Meyer et al., 2023; OECD, 2019, 2023). Currently, Flemish adolescents also report low levels of reading motivation, reflecting a lack of interest and enjoyment in reading (De Meyer et al., 2019; OECD, 2019). These concerning findings are especially pronounced among students enrolled in prevocational and vocational tracks, who demonstrate lower reading motivation, weaker reading comprehension skills, and limited engagement with reading both inside and outside the classroom (De Meyer et al., 2023; OECD, 2019; Van Ammel et al., 2021b). Vocational students are particularly vulnerable as their curricula combine general education with technical skill development aimed at direct entry into the workforce. Alarmingly, only 34% of vocational students in Flanders meet the government’s functional reading comprehension standards by the end of their training (Steunpunt Toetsontwikkeling en Peilingen (STEP), 2021), raising concerns about their preparedness for employment and lifelong learning.

Given the critical role of teachers in shaping students’ reading comprehension, high-quality reading comprehension instruction and reading motivation promotion are essential. However, studies point to shortcomings in teachers’ competence for delivering effective reading comprehension instruction and fostering reading motivation in their classrooms (McRae & Guthrie, 2009; Vansteelandt et al., 2022). While a substantial body of research has focused on reading pedagogy in general education (Duke et al., 2011; Guthrie, 2004), vocational and prevocational education contexts remain underrepresented in international literacy research (Conradi et al., 2014). Recent studies emphasize that teachers in vocational education often lack systematic professional development (PD) opportunities to enhance their reading instruction, particularly with regard to motivational strategies (Van Ammel et al., 2021a). Moreover, although integrated approaches that combine reading comprehension and reading motivation promotion have been shown to be more effective, such models remain rare in both research and practice (Van Ammel et al., 2021a). The present study addresses this critical gap in the literature by designing and evaluating a targeted educational intervention aimed at strengthening teacher competence in reading comprehension and its instruction and reading motivation and its promotion within the context of prevocational education. In doing so, it responds to both international and regional calls for teacher-centered, evidence-informed solutions to improve reading outcomes among vulnerable student populations, contributing new insights to the field of literacy education.

1.1. Theoretical Framework

This study connects four domains of literature: teacher competence, reading comprehension and its instruction, reading motivation and its promotion and teacher professional development. Combined, these domains shed light on how teachers can be supported by professional development in effectively enhancing students’ reading. The study applies this to the setting of prevocational education. Central is the role of professional development focusing on teacher competence as a bridge between reading instruction and student outcomes.

1.1.1. Teacher Competence

Teacher competence encompasses the cognitive and affective-motivational factors influencing teacher behavior across diverse instructional contexts (Blömeke et al., 2016; Blömeke et al., 2015; Blömeke et al., 2022; Blömeke & Kaiser, 2017; Kunter et al., 2013). It is built on two core types of dispositions: professional knowledge and affective motivational characteristics including beliefs, and self-efficacy. These dispositions underpin situation-specific skills like perception, interpretation, and decision-making, which collectively shape teachers’ instructional behavior (Blömeke et al., 2015). Improving teachers’ instructional practice, therefore, requires a deep understanding of and targeted interventions in the foundational dispositions.

Within professional knowledge, Shulman (1986) distinguishes between content knowledge (i.e., understanding the subject matter itself) and pedagogical content knowledge, which refers to knowing how to effectively teach that content to students. Both are critical to high-quality instruction.

Affective-motivational dispositions, such as interest, motivation, volition, values, beliefs, and attitudes, also play a key role, as highlighted by Blömeke et al. (2017). Of particular importance in the present study are teachers’ beliefs about their students and about their own role and their perceived self-efficacy (Bandura, 1978), especially in the context of teaching reading and promoting reading motivation. These beliefs influence whether and how teachers apply their knowledge in practice (Pajares, 1992).

1.1.2. Reading Comprehension and Its Instruction

Several influential models of reading comprehension have shaped the field, including the Simple View of Reading (Hoover, 2024; Hoover & Gough, 1990), the RAND Reading Study Group’s heuristic model (Snow, 2002), and Scarborough’s Reading Rope (Scarborough, 2001). Recently situation models have gained prominence in research regarding reading (Davoudi & Hashemi Moghadam, 2015). Within situation models, reading comprehension is understood as constructing meaning from text by connecting information with prior knowledge. Kintsch’s Construction–Integration Model (Kintsch, 1988, 2005) distinguishes between two levels of mental representation: the text base and situation model. The text base model involves accurate encoding and retention of textual information in working memory, while the situation model integrates the text with the reader’s prior knowledge, producing deeper understanding. This model is particularly relevant for mapping teachers’ content knowledge, as it illuminates the dynamic interactions among different components of comprehension, thereby opening possibilities for connecting theory to reading comprehension instruction. However, the literature also points to a gap concerning the distinction between comprehension processes and outcomes (Davoudi & Hashemi Moghadam, 2015). To address this, van den Broek and Helder (2017) expanded the model by differentiating between the outcomes of comprehension (the product) and the processes that lead to it. Some processes are automatic and thus passive, while others are active and reader-initiated, requiring deliberate effort, such as making inferences or resolving ambiguities while reading. The extent to which readers engage in each depends on their “standards of coherence” or the internal benchmarks used to determine whether their understanding of the text makes sense (van den Broek & Helder, 2017). When comprehension fails, readers initiate more effortful strategies to restore meaning.

Reading comprehension instruction is teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge and stands as one of the most extensively investigated domains within language instruction research (Geudens et al., 2023). While there is general agreement on the core elements of effective reading comprehension instruction, minor differences sometimes emerge in different studies. Recent literature reviews offer a comprehensive overview of the common ground regarding characteristics of effective reading comprehension instruction (e.g., Duke et al., 2011; Geudens et al., 2023; Houtveen et al., 2019; Merchie et al., 2019). In this study, effective RCI entails following elements.

- Engaging students in textual discourse (Guthrie, 2004; Murphy et al., 2009).

- Teaching about reading comprehension, for instance by strategy-instruction (Okkinga et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2021) or teaching text structures (Bogaerds-Hazenberg et al., 2024; Nestlog et al., 2024).

- Promoting reading motivation (Schiefele et al., 2012; Van der Sande et al., 2023; Wigfield et al., 2016).

- Offering a diverse range of functional texts and contexts (Wigfield et al., 2016).

- Fostering knowledge acquisition, encompassing vocabulary development and world knowledge (Cabell & Hwang, 2020; Cervetti et al., 2016).

- Integrating reading and writing activities (Graham, 2020; Shanahan et al., 2025).

1.1.3. Reading Motivation and Its Promotion

Reading motivation refers to what drives a person to read (Wigfield et al., 2016). In recent decades, several motivational theories have shaped educational research including the Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1978), Achievement Goal theory (Dweck & Leggett, 1988), and Self-Determination Theory (Deci et al., 1991). Among these, Self-Determination Theory (R. M. Ryan & Deci, 2000) has become particularly influential in studies on reading motivation in academic contexts (De Naeghel et al., 2014; Engler & Westphal, 2024; Lin, 2025; Svrcek & Abugasea Heidt, 2022; Vansteelandt et al., 2022). This study maps teachers’ content knowledge regarding reading motivation. The framework distinguishes between self-determined and controlled types of regulation of behavior, referred to as autonomous and controlled motivation (Deci et al., 1991; R. M. Ryan & Deci, 2000). Controlled motivation contains two regulatory styles of motivation: external regulation (e.g., behavior based on external rewards, punishments) and introjected regulation (e.g., behavior coming from pressure from within). Autonomous motivation consists of three types of identified regulation involving recognizing the value or importance of an activity and willingly engaging in it, integrated regulation, where the activity becomes fully integrated into the person’s self, and intrinsic regulation, driven by interest, enjoyment and satisfaction derived from the activity itself. Given the positive outcomes associated with autonomous motivation namely, higher reading frequency and better reading comprehension performance it is beneficial to cultivate this type of motivation (De Naeghel et al., 2012; Linde & Daniela, 2025; Vansteelandt et al., 2022).

Cognitive Evaluation Theory, a sub-theory of the Self-Determination Theory, highlights three innate psychological needs essential for fostering motivation and well-being: competence, relatedness, and autonomy (R. M. Ryan & Deci, 2000, 2020). Satisfying these is key to enhancing autonomous motivation. Previous research has related these insights to education, demonstrating pedagogical content knowledge or how teachers can promote students’ autonomous reading motivation by addressing these needs and adapting their instructional approach (De Naeghel et al., 2016; Van Ammel et al., 2021b). The following section introduces practical tools for reading motivation promotion. First, competence refers to the need to feel capable of achieving goals and taking the necessary steps to do so. In reading comprehension instruction, teachers can support this by modeling text comprehension, providing positive feedback, and offering explicit reading strategy instruction. Second, relatedness reflects the need to feel connected and supported by others. This can be fostered through collaborative learning, reading aloud in small groups, or organizing collective reading activities. Third, autonomy involves the need to make independent choices and take responsibility for one’s learning. Teachers can support this by offering students choices, such as selecting books or texts to read. These theoretical insights can manifest in practice as the knowledge and beliefs held by participants. Given its strong theoretical and empirical foundation, this study adopts Self-Determination Theory as its guiding framework. By focusing on the basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, Self-Determination Theory provides a nuanced lens to understand how classroom practices and teacher behavior can foster more self-determined forms of reading motivation. This makes Self-Determination Theory particularly suitable for informing instructional approaches and professional development aimed at promoting long-term and beneficial forms of motivation for reading.

1.1.4. Teacher Professional Development

Our aim is to activate and strengthen teachers’ dispositions regarding reading through PD. Over the last decades, several studies on teacher PD have advanced our knowledge about components of effective teacher PD such as Guskey’s (2002) path model of teacher change, Clarke and Hollingsworth’s (2002) Interconnected Model of Professional Growth, Desimone’s path model including core features for professional development (Desimone, 2009), and more recently Darling-Hammond’s seven elements of effective teacher PD (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). Among these, Desimone’s model is particularly interesting because it focuses on the interactions between the core features of PD and increased teacher competence, change in instruction, and subsequent improved student learning. In line with this model, the design of the present program was guided by the five core features of effective PD: content focus, active learning, coherence, duration, and collective participation guided the program’s design (Desimone, 2009, 2011). Moreover, Desimone’s theoretical framework provides a strong rationale for how professional development can strengthen teacher competence, support high-quality reading comprehension instruction, and promote reading motivation.

Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses of teacher PD in reading have synthesized evidence regarding its impact on both student outcomes and teachers’ knowledge, beliefs and skills. Didion et al. (2020) drawing on studies of students from kindergarten through eighth grade, reported a moderate but statistically significant positive average effect on student reading achievement. Basma and Savage (2023), reviewing studies in middle and high school settings, found a small effect on student reading outcomes, with effects moderated by delivery mode, PD hours, student population, and assessment type. Van der Sande et al. (2023) found positive effects on autonomous reading motivation and reading comprehension. Turning to teacher-level outcomes, Rice et al. (2024) conducted a meta-analysis of reading comprehension PD for elementary teachers and identified significant gains in teachers’ knowledge and skills. Similarly, Filderman et al. (2025) examined in-service teachers across grade levels, from kindergarten through twelfth grade, and revealed that reading-focused PD yielded a large and significant improvement in teachers’ knowledge and skills, whereas its impact on teachers’ beliefs was small and nonsignificant.

1.2. Research Objectives

This study examines the role of teacher PD in shaping teachers’ dispositions, particularly their professional knowledge and beliefs about reading comprehension, its instruction, reading motivation and its promotion. The focus is on teachers of Dutch and Project General Subjects (PGS) in 7th and 8th grade prevocational education. In Flanders, some schools in prevocational education offer PGS, where students engage in interdisciplinary projects covering subjects like language, mathematics, history, geography, and sciences. This teacher group is of particular interest due to the low reading achievement and declining reading motivation levels among their students, highlighting the crucial role teachers play in addressing these challenges (Washburn & Pierce, 2025).

2. Method

The first author draws on her experience as an in-service teacher trainer, working closely with prevocational schools in supporting teachers’ PD. From this background, she entered academic research on teacher professionalization and reading literacy in prevocational contexts. This dual perspective—rooted in both practice and research—offers valuable contextual insights, while also demanding reflexivity regarding own assumptions about effective instruction and professional development.

2.1. Participants

Four Flemish secondary schools offering prevocational education for students aged 13 to 15 participated in a PD program and accompanying research. In total, 27 participants were involved. In three schools, one staff member was intentionally included as a full PD participant. All participants provided informed consent, and schools are referred to by pseudonyms to protect anonymity. The study followed the General Ethical Protocol for Scientific Research at the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of Ghent University. In Table 1 a description of the schools and the participants is provided.

Table 1.

Summary of Schools’ and Participants’ Descriptions.

2.2. Research Design

A multiple case-study approach (Yin, 2018) was chosen to gain a nuanced understanding of how PD processes unfolded within varied school contexts. This approach enabled in depth analysis of complex, context-specific phenomena that are often missed in large-scale studies and that influence teacher learning.

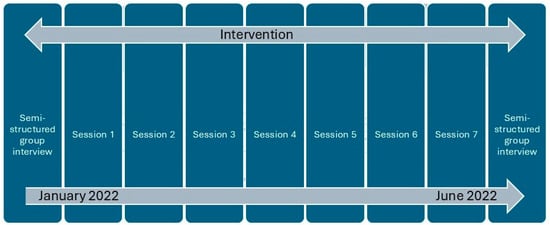

2.2.1. Description of the Professional Development

The PD was designed building on Desimone’s framework (Desimone, 2009, 2011) for effective teacher development. Each school participated in the PD program separately. The sessions were facilitated by the first author. To ensure fidelity a detailed road map was used for each session, supported by a PowerPoint presentation, and structured reflection prompts. For the lesson observation, the teachers received an observation form; for lesson design, the presentation included a step-by step plan, and a blank lesson plan template was provided. An overview of the PD structure is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the PD intervention study.

The content of the PD focused on two themes: reading comprehension and reading motivation. As shown in Table 2, participants were introduced to current research in both domains, with particular emphasis on translating theory into practice. For reading comprehension, the program included demonstrations of effective instructional strategies, which teachers were encouraged to apply in their own classrooms. As to motivation, participants examined how to better understand and support students’ motivation in reading.

Table 2.

Overview of the goals and approach per session.

Active learning was central to the PD. Teachers participated in group discussions, developed lesson materials collaboratively, and engaged in structured reflection after classroom application. In session 4, participants observed a lesson delivered by the researcher supported by an observation guide provided to facilitate discussion. In session 5, teachers co-developed their own reading lesson. These lessons were taught and observed by peers and the researcher, followed by debriefing discussions. To ensure coherence the PD connected with teachers’ existing knowledge and aligned with broader school policies and policy reforms. In terms of duration, 7 sessions were delivered over a six-month period, totaling 16 PD hours. The first two sessions were held online due to pandemic restrictions; session three was offered as a prerecorded masterclass, which not all participants viewed. The remaining sessions were typically held on campus. Collective participation was emphasized. Teachers worked in groups, set shared goals, and reflected together on their development. The first and the final sessions framed the PD as a joint endeavor. Collaboration was further supported by the availability of the researcher for feedback and co-planning.

2.2.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

Data were collected through semi-structured group interviews conducted during the first and final sessions of the PD program. The questions of these interviews can be found in Appendix A. Not all teacher participants attended the group interviews; however, as the analysis and reporting focused on the collective level rather than on individual contributions, this was not considered a limitation. This approach enabled a comparative analysis of perspectives over time, capturing both initial understandings and subsequent shifts in thinking. By putting these changes within each school’s specific context, the interviews provided insight into how professional learning unfolded in practice.

2.2.3. Qualitative Analysis of Interviews

The first author conducted the thematic analysis following the six-phase framework proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006, 2022), ensuring both analytical rigor and transparency in the development of themes.

The analytic process itself followed six phases. First, all interviews were transcribed verbatim. To ensure immersion in the data, the first author read the transcripts multiple times and wrote initial notes and reflections to capture early impressions; no formal coding was applied at this stage. Second, a manual, inductive approach was used to generate initial codes. Broad descriptive codes were developed to capture content related to teachers’ knowledge and beliefs. Third, similar units of meaning were clustered into preliminary themes. These themes centered on reading comprehension and its instruction, and reading motivation and its promotion, reflecting the core components of the PD program. At this stage, each coded segment was assigned a secondary code to indicate whether it provided insight into teachers’ knowledge or beliefs. For segments reflecting teacher beliefs, a third layer of coding was applied to specify the focus of the belief, for example, beliefs about students, about their own role, or self-efficacy beliefs (see Table 3 for the coding tree). Fourth, codings were entered in NVivo 14. Themes were refined, codes revised, and a coding tree was developed to visualize the thematic structure. Fifth, the themes and sub-themes were carefully defined and named; where relevant, fine-grained distinction; for instance, differentiating between autonomous and controlled student motivation, were introduced to sharpen thematic focus. Finally, in the sixth phase, themes were presented using illustrative quotes and thick descriptions to convey participants’ voices. To strengthen the credibility and consistency of the analysis, 25% of the data was independently double-coded by a second researcher. The first author provided a coding tree and codebook, and one transcript fragment was initially coded jointly as a training exercise to establish a shared understanding of the coding framework. Thereafter, the independent researcher coded 25% of the data independently, which resulted in a high level of agreement (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.81; Lumivero, 2020), indicating strong consistency in the application of codes.

Table 3.

Coding Tree.

Table 3 presents the coding tree as the final outcome of the analytic process. Rather than detailing each coding step, it provides a visual overview of the thematic structure that emerged from the three-layered coding process.

3. Results

3.1. Flanders Technical Academy

Although the school staff required participation of the teachers, the teachers faced scheduling pressures and heavy workloads, which fostered resistance and hindered the implementation of the lesson plans. In this school, six participants took part in the semi-structured interviews at the beginning, and eight at the end, of whom six were the same and two were new.

Participants initially viewed reading comprehension as simply reading and understanding text, with some mistakenly equating it with studying content. After the PD, their understanding broadened to include the notion of deriving meaning from texts (1).

| 1 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Reading comprehension involves comprehending a text accurately.” | “Reading comprehension involves leveraging the context to derive meaning.” |

Teachers continued to perceive reading comprehension as a challenge for students in the prevocational track, but by the end of the PD, they acknowledged contributing factors such as vocabulary deficits, limited world knowledge, and external influences like the pandemic (2).

| 2 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Students are unable to demonstrate reading comprehension.” | “Students’ low reading comprehension level is due to limited vocabulary and a lack of foundational knowledge.” |

Early in the PD program, teachers did not elaborate on pedagogical content knowledge in reading instruction; teachers mostly relied on commercial manuals or used self-developed materials. By the end, they recognized the importance of integrating reading motivation promotion into their reading instruction. While teachers initially already considered their role in reading instruction as crucial, the PD helped them expand this view, emphasizing their active role beyond just following manuals (3).

| 3 | Before PD | After PD |

| “It is important to teach reading comprehension.” | “If you choose the right text, I think you’ve already achieved about 60% more with your lesson than if you just take a text from the manual, where it’s merely about searching for information in texts. That doesn’t work in prevocational education. You have to be able to do some magic there.” |

Initially, teachers lacked self-efficacy, particularly in selecting suitable and engaging texts for their students. After the program, their self-efficacy increased, especially when delivering the lesson, they had developed collaboratively (4).

| 4 | Before PD | After PD |

| “It is difficult to offer a text at their level matching their interests.” | “It is an exciting lesson that I plan to teach next year.” |

At first, participants struggled to define reading motivation, narrowing it to reading pleasure, and they attributed students’ lack of motivation to infrequent reading habits. After the PD, they identified more underlying causes, such as difficulties with reading fluency (5).

| 5 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Reading motivation involves students enjoying reading.” | “Students struggled significantly with reading fluency in elementary school.” |

Initially, they could not elaborate on how they promoted reading motivation, although they mentioned various activities. By the end of the PD, they provided concrete examples of strategies they had used (6).

| 6 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Defining reading motivation promotion is difficult.” | “Students’ reading motivation is growing because I focus more on the context of the text.” |

Teachers initially viewed their role in promoting reading motivation as centered on organizing reading time and preparing materials, and they also pointed to a lack of time and space as significant barriers to implementation. After the PD, they acknowledged the influence of school policy, such as expanding book collections, and creating reading spaces, on fostering a reading culture (7).

| 7 | Before PD | After PD |

| “The teacher’s role is to ensure students to put their phones away and sit with a book.” | “Reading motivation promotion involves allocating time and paying attention to it.” |

Teachers originally lacked confidence in their ability of promoting reading motivation. However, their confidence increased as they experienced the benefits of collaboration (8).

| 8 | Before PD | After PD |

| “I am unsure about my confidence in reading motivation promotion.” | “More cooperation with other teachers would help me feel more confident.” |

3.2. Nexus School

At Nexus School, participants completed the PD as planned and all three participants took part in both semi-structured interviews. Initially, they defined reading comprehension as a combination of reading and understanding but questioned whether fluency was a prerequisite. A common misconception emerged confusing reading comprehension with reading for pleasure. By the end of the PD, participants clarified that reading comprehension involves understanding a text’s content in depth and noted that comprehension could also foster enjoyment (9).

| 9 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Reading comprehension involves reading the text and understanding its content.” | “Reading comprehension is grasping both the essence and the depth of a text.” |

At the outset, participants held negative beliefs about their students’ reading comprehension level, often comparing them to primary school levels. However, by the end of the PD, they observed improved student engagement during lessons and developed a more positive outlook on their students’ reading capabilities.

| 10 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Students will not be able to read proficiently.” | “I underestimated the students.” |

With limited prior training, instruction often relied on manuals or ad hoc support, sometimes reduced to testing. Over time, participants came to see the value of a structured, proactive approach to guiding students through texts (11).

| 11 | Before PD | After PD |

| “[Reading comprehension instruction is] offering short texts with questions.” | “[Reading comprehension instruction is] providing a clear structure for how to read the text.” |

At first, teachers’ role was shaped largely by pre-set tasks such as testing, following manuals, or answering questions. By the end of the PD, they considered themselves as actively responsible for teaching reading skills, emphasizing the importance of step-by-step instruction.

| 12 | Before PD | After PD |

| “I follow the manual.” | “You have to take time to read a text.” |

Teachers’ initial lack of confidence in teaching students with limited Dutch proficiency gave way to increased self-efficacy after delivering their own reading lessons.

| 13 | Before PD | After PD |

| “How supporting students who are not proficient in Dutch.” | “I really enjoyed [teaching] this lesson and want to do it again.” |

While teachers recognized a lack of motivation among students, by the end of the PD their concern shifted to students’ reluctance to engage with full-length books. The concept of reading motivation was approached with a focus on practical application. By the end of the PD, participants identified it as their goal (i.e., encouraging students to read) but could not always articulate specific strategies for promoting it.

| 14 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Reading motivation involves providing a diverse range of books.” | “Our goal is to cultivate reading pleasure for our students.” |

Teachers described their role in promoting reading motivation in different ways, ranging from creating enthousiasm to emphazing structure and guidance. A limited book supply was cited as a barrier. However, participants began to recognize their influence in guiding students and scheduling motivational activities, and contributing to a reading-motivating environment.

| 15 | Before PD | After PD |

| “The teacher’s role is to ensure students to put their phones away and sit with a book.” | “Reading motivation promotion involves allocating time and paying attention to it.” |

Initially, participants expressed difficulties in motivating students to read. By the end of the PD, they emphasized that although their understanding had grown, motivating students in the prevocational track remained particularly challenging (16).

| 16 | Before PD | After PD |

| “It is quite challenging to encourage students to engage in reading” | “It is more challenging in prevocational education.” |

3.3. Professional Academy

At Professional Academy, most participants joined the PD at the request of a staff member, despite initial resistance due to competing demands and uncertainty about its outcomes. Ongoing support and motivational efforts during the sessions helped reduce this reluctance, enabling teachers to effectively deliver the lessons they had developed. For the semi-structured interviews, 12 participants took part at the beginning and 9 at the end, of whom 2 were different from those in the initial group.

Participants initially considered reading comprehension as simply reading and understanding a text. Two misconceptions emerged: first, that reading comprehension was limited to reading and answering literal questions; and second, that it applied exclusively to informational texts, and was distinct from reading for pleasure. After the PD, participants began to consider reading comprehension as a more complex process. While the first misconception was addressed, the second (i.e., regarding the separation of comprehension and pleasure) persisted (17).

| 17 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Reading comprehension involves reading a text and answering questions.” | “Reading comprehension is complex, we must teach it to students.” |

Teachers initially believed that students struggled with reading comprehension due to difficulties in grasping deeper meanings. Over time, they identified contributing factors such as insufficient reading practice and students’ low confidence in their own abilities (18).

| 18 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Students struggle with deep comprehension of texts and stay on the surface.” | “Students lack confidence in their reading abilities.” |

At the start, participants had difficulty defining reading comprehension instruction, often describing it in terms of asking questions about texts. Their understanding of instruction broadened over the course of the PD. This shift was reflected in their evolving views of their own role: initially, limited to assigning to continue reading during tasks, their perspective shifted toward actively guiding the comprehension process (19).

| 19 | Before PD | After PD |

| “We consistently assign students to continue reading.” | “Step by step, we need to build and enhance students’ reading comprehension abilities.” |

Early frustrations with teaching reading comprehensionstemmed from uncertainty about how to adapt strategies. By the end of the PD, teachers felt more positive about the lessons they delivered but expressed a need for more time to implement new strategies (20). Finding texts that matched both students’ interests and reading levels remained a persistent challenge.

| 20 | Before PD | After PD |

| “We consistently assign students to continue reading.” | “Step by step, we need to build and enhance students’ reading comprehension abilities.” |

Reading motivation was initially defined as reading without pressure, often equated with reading for pleasure. Some participants recognized its role in supporting comprehension but considered it as text dependent (21). Teachers began the PD with the belief that all students were unmotivated readers. After the PD, they observed a more nuanced picture, noting that while some students were consistently motivated, others showed occasional interest.

| 21 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Reading motivation occurs when a student enjoys reading without feelings of pressure.” | “For our students, reading motivation is less about enthusiastic reading in all contexts and more about accepting to read a given text.” |

Throughout the PD, participants struggled to define reading motivation promotion but were already employing some effective practices, such as allowing students to choose from a variety of books. By the end, their interest in reading motivation promotion had grown, and they became merely intentional in selecting texts that students felt comfortable and confident engaging with (22).

| 22 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Allow them to choose their reading material.” | “ Reading motivation promotion involves offering brief texts that students feel confident to tackle.” |

Initially, teachers considered themselves primarily as role models who recommended books. By the end of the PD, they began to see their role as actively promoting reading motivation through thoughtful text selection and instructional strategies.

| 23 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Bring a book to class and place it on your desk.” | “The lesson should be conducive to reading motivation promotion.” |

Their self-efficacy grew as they witnessed students’ positive responses, which in turn reinforced their motivation to continue improving their approach. At the outset, teachers had difficulties in finding suitable texts. However, by the end of the PD, they noted that seeing the enthusiasm of their students boosted their self-efficacy, and they discovered strategies to enhance their confidence in promoting reading motivation.

| 24 | Before PD | After PD |

| “It is challenging to find rich texts aligning with our themes in PGS.” | “Seeing students’ enthusiasm fills me with joy.” |

3.4. Pathways Institute

At Pathways institute, three teachers initially participated in the PD. One later disengaged, citing feeling overwhelmed and prior education covering reading comprehension instruction. All three teachers took part in both semi-structured interviews.

Participants initially defined reading comprehension as understanding a text and conveying its essence with a focus on vocabulary and clearly defined reading objectives. A persistent misconception was that reading comprehension always involved specific tasks, such as answering questions, and that it was distinct from reading for pleasure. This misconception persisted even after the PD (25). One teacher initially believed that all students in prevocational education were at the same reading level but later came to recognize differences in proficiency.

| 25 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Reading comprehension is always purposeful and not for fun.” | “We need to differentiate between reading for comprehension, where training on reading fluency is essential, as well as reading for pleasure.” |

Reading instruction was first understood broadly as supporting comprehension but by the end of the PD, it was described in more limited terms, mainly as administering reading tests (26). Teachers relied heavily on commercial manuals both before and after the PD.

| 26 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Reading comprehension instruction is promoting reading comprehension.” | “Reading comprehension instruction involves taking a reading test.” |

Teachers did not feel competent in reading comprehension instruction andexpressed a desire for more effective instructional strategies. However, by the end of the PD, they remained uncertain about how to approach reading instruction.

| 27 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Reading comprehension instruction is promoting reading comprehension.” | “Reading comprehension instruction involves taking a reading test.” |

Reading motivation was initially equated with reading for pleasure, but this understanding gradually expanded to include students’ interest in reading. Early on, participants felt that students were generally reluctant readers. After the PD, some teachers even expressed doubt that their students would ever experience autonomous reading motivation (28). One participant did demonstrate a strong understanding of Self-Determination Theory from the beginning.

| 28 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Students read reluctantly.” | “My students will never experience reading motivation.” |

Initially, the teacher’s role in promoting reading motivation was seen as ensuring that students completed their work independently. By the end of the PD, participants struggled to define their role more clearly and several activities aimed at promoting reading motivation were reported as unsuccessful (29).

| 29 | Before PD | After PD |

| “Allow students to work individually.” | “Describing my role is difficult. I tried to read out loud, did some free reading, but students disrupted the lessons.” |

Throughout the PD, teachers struggled promoting reading motivation (30).

| 30 | Before PD | After PD |

| “I struggle to inspire reading motivation.” | “I struggle with addressing reading motivation.” |

3.5. Cross-Case Analysis

A cross-case analysis revealed varied outcomes concerning teacher knowledge, beliefs about their students and roles as teachers, and their self-efficacy. Overall, participants demonstrated expanded and deepened knowledge of reading comprehension and its instruction, with corresponding shifts in their beliefs, positively impacting their self-efficacy. However, minimal changes were observed in teacher dispositions toward reading motivation and its promotion.

4. Discussion

This discussion interprets the findings through relevant theoretical frameworks while critically examining the differential effects observed across reading comprehension and its instruction and reading motivation and its promotion. It also explores school-specific variation and outlines implications for PD and practice.

4.1. Reading Comprehension

At the outset of the PD, participants understood reading comprehension mainly in terms of surface-level outcomes, rather than as the deep integration of text and prior knowledge involved in constructing a situation model (Kintsch, 1988). The PD successfully broadened this perspective by emphasizing reader-initiated processes, consistent with van den Broek and Helder’s (2017) model. This shift aligns with Rice et al.’s (2024) meta-analysis on PD’s effects on content knowledge as well as with Filderman et al.’s (2025) review. However, critical gaps in knowledge remain. Many teachers failed to integrate key elements of reading comprehension, such as the situation model and the role of prior knowledge (Kintsch, 1988, 2005). Misconception persisted, including the belief that reading comprehension is separate from reading for pleasure. Teachers’ beliefs regarding struggling readers did deepen, with greater recognition of vocabulary deficits as contributing factors (Duke et al., 2011).

4.2. Reading Comprehension Instruction

At the outset, teachers addressed only one instructional principle for teaching reading, namely using varied, functional texts which they found challenging. This finding is consistent with the Flemish education inspection’s report, which noted that fewer than half of primary schools implement effective reading didactics (Onderwijsinspectie, 2020). By the end of the PD, participants emphasized explicit instruction in reading, consistent with best practices research (Houtveen et al., 2019; Merchie et al., 2019). The growth in teachers’ knowledge after PD is in line with other research (e.g., Medina et al., 2021; Tiba, 2023). However, essential aspects, such as engaging students in textual discourse, fostering knowledge acquisition, or integrating reading and writing, remained absent. Teachers reported increased self-efficacy, primarily through vicarious learning, and successful lesson delivery (Bandura, 1978, 1989; Klassen & Tze, 2014; M. Ryan & Hendry, 2022).

4.3. Reading Motivation

The PD had minimal impact on teachers’ knowledge and beliefs regarding reading motivation, which contradicts Filderman et al.’s (2025) findings on knowledge but is in line with what has been reported about beliefs. Teachers continued to rely on commercial manuals that emphasize reading for pleasure, adopting their content often without critical reflection. These manuals primarily offer fictional texts to encourage it. Although some developed a more nuanced understanding, thereby acknowledging self-confidence as a component of autonomous motivation (Conradi et al., 2014), most participants failed to move beyond superficial interpretations.

4.4. Reading Motivation Promotion

While teachers aimed and claimed to promote reading, they often rely on intuition rather than on theory-informed strategies. Only one teacher explicitly referred to the Cognitive Evaluation Theory (Deci et al., 1991), suggesting a disconnect between practice and theory. In one school, however, the role of motivation promotion emerged as a new insight (Duke et al., 2011), which points to the teachers gradually recognizing the importance of motivational aspects. The gap between research and practice may explain persistently low self-efficacy (Vansteelandt et al., 2020). Additionally, participants often cited contextual constraints (e.g., time, space) to justify limited action, which contrasts with the increased awareness, especially by the end of the PD, that teachers play a crucial role in shaping motivational climates (Garces-Bacsal et al., 2018; Ruwette et al., 2020; Van der Sande et al., 2023).

4.5. Varying Effects Across Domains and Contexts

The PD’s stronger impact on reading comprehension and its instruction can be attributed to two main factors. First, these domains were closely tied to everyday classroom teaching, which facilitated immediate application and experimentation. Teachers could readily try out new strategies during lessons and reflect on their effectiveness, an approach well supported in the literature of effective PD (Desimone, 2009, 2011; Desimone & Garet, 2015). In contrast, reading motivation and its promotion were less concrete and harder to integrate into instructional acts in the short term. Addressing these aspects required more profound shifts in teachers’ perceptions of their role and their relationships with students; shifts that typically develop over time and are shaped by contextual factors such as school culture, student interactions, and personal teacher beliefs. This complexity helps explain why teacher beliefs regarding motivation shifted less than instructional knowledge. This difference aligns with King et al. (2023) pragmatic meta-model of teacher learning, which emphasizes the non-linear, iterative, and situated nature of it. From this perspective, it is unsurprising that knowledge-based domains like reading comprehension instruction responded more readily to structured input, while belief- and emotion-driven domains like reading motivation required more time and contextual responsiveness than the PD allowed. Another contributing factor may lie in the degree of dissatisfaction teachers experienced with their existing practice. As Hollenbeck and Kalchman (2013) note, discontent is often a catalyst for change. In the present study, teachers more readily identified shortcomings in their reading instruction than in their efforts to motivate students, which may have reduced the feelings of urgency for change in the latter domain.

In addition to differences across instructional domains, variation was observed between schools, shaped by several contextual and structural factors (Desimone & Garet, 2015; Lentz et al., 2024; Magnusson et al., 2023; M. Ryan & Hendry, 2022). First, time allocation was crucial: in at least one case, a participant mentioned a lack of time as the reason for discontinuing the PD (Magnusson et al., 2023). Second, participants brought different levels of prior knowledge and experience, which affected their engagement with the PD content (Desimone & Garet, 2015). Third, leadership support emerged as a critical factor. Schools in which leadership aligned with PD goals, allocated time, and actively participated showed more robust implementation. This finding is in line with prior research that underscores the importance of supportive leadership for sustaining change.

4.6. Implications for Practice

The present study points to several design features that can strengthen PD for teachers in prevocational education. More specifically, the study reinforces the importance of tailoring PD to local contexts, not only by adapting content but also by embedding flexible structures that enable facilitators to address teachers’ initial knowledge and beliefs, and to adjust support throughout the process. Therefore, PD providers and policymakers are encouraged to design PD programs that begin with mapping teachers’ existing knowledge and beliefs and include built-in structured moments for follow-up that enable facilitators to monitor how these knowledge and belief systems develop over time, while also providing space for feedback, mentoring, and targeted support. Finally, PD design should be responsive not only to teacher needs but also to emotional and motivational factors. As the discussion suggests, promoting reading motivation required deeper shifts in teacher beliefs and relational understandings, which developed more slowly than instructional knowledge due to their emotional and contextual complexity. Offering reflective tools, affective check-ins, or optional coaching sessions can help support such changes in belief. These practical steps create a richer and more sustainable learning environment aligned with the complexity acknowledged (Bilge & Kalenderoğlu, 2022; King et al., 2023).

4.7. Limitations of the Research

Researcher positionality remains a complex and often ambiguous aspect of research (Chin et al., 2022). In this study, the researcher held a dual role as both the designer and facilitator of the PD program, and as a pedagogical advisor to the participating schools. This embedded position afforded rich contextual insight, enhanced access to schools, and strengthened relational trust. However, it also introduced potential for bias, particularly in how participants might respond. The researcher was acutely aware of this dynamic and took deliberate methodological steps to mitigate its effects. Rather than asking teachers to self-report change (an approach more susceptible to social desirability bias) the group interviews focused on broader discussions of what teachers considered to be reading comprehension and reading motivation, and how these were applied in their teaching. This strategy allowed for the elicitation of underlying beliefs and perceptions, rather than overt evaluations of the PD or personal performance. In doing so, the method aimed to surface more implicit dispositions and definitions that might otherwise remain unspoken in more evaluative formats. This aligns with a stance of inquiry that prioritizes reflective dialog and meaning-making over measurement (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009). Second, the study was conducted in an authentic school-based PD setting, resulting in variable operational conditions across four participating schools. Although this diversity offered insight into the influence of contextual factors, the small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic required one planned session to be replaced with a prerecorded masterclass. This format did not engage teachers to the same extent as live sessions. Consequently, there were no opportunities for interaction and collaborative reflection during this session, which may have limited the depth of professional learning achieved. Additionally, although we did not explicitly monitor viewing rates, some teachers reported not having watched the fragment, citing lack of time as the reason. The conclusions drawn should therefore be interpreted as exploratory and illustrative, rather than definitive. Finally, the study focused on teachers’ dispositions related to reading comprehension and motivation. The use of semi-structured group interviews provided insight into collective knowledge and beliefs but did not capture individual learning trajectories. Additionally the study did not consider situation-specific cognitive skills or instructional performance, a central component in Blömeke et al.’s (2016) model of teacher competence. Future research should adopt a more comprehensive approach, combining these dimensions to better understand how professional learning translates into classroom practice.

5. Conclusions

This exploratory study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of how PD can influence teachers’ knowledge and beliefs in the context of prevocational reading education. By examining changes in teacher dispositions before and after a targeted PD intervention, the study reveals that while participants began with limited understandings of reading comprehension, the PD facilitated meaningful gains, particularly in knowledge and self-efficacy. However, progress in the area of reading motivation was more limited, suggesting that affective and relational components of literacy teaching require longer-term and more emotionally attuned support. Importantly, the variation in outcomes across schools underscores the influence of local conditions including time allocation, leadership involvement, and teacher engagement. These findings reinforce the need for PD models that are not only responsive to teachers’ needs but also flexible enough to adapt to diverse school ecologies. This aligns with recent calls in the literature (e.g., King et al., 2023) to move beyond standardized delivery models toward context-sensitive and complexity-aware PD designs. While these insights are grounded in the Flemish context, they may resonate with broader discussions about literacy instruction in vocational settings internationally. Still, the small sample size and highly contextualized setting warrant caution in drawing general conclusions. The findings offer direction for future PD design by illustrating the value of combining structured instructional input with opportunities for school-based adaptation, and by highlighting the need to integrate relational, emotional, and critical dimensions of teacher learning into PD aimed at motivating disengaged readers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W. and H.V.K.; methodology, S.W. and H.V.K.; validation, S.W. and H.V.K.; formal analysis, S.W.; investigation, S.W.; resources, S.W.; data curation, S.W.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W.; writing—review and editing, S.W. and H.V.K.; visualization, S.W.; supervision, H.V.K. project administration, S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its compliance with the General Ethical Protocol for Scientific Research at the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of Ghent University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Provincial Education Flanders and the five Flemish provinces.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PD | Professional Development |

| PGS | Project General Subjects |

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Group-Interview

Interview 1

What is reading comprehension?

How do you approach reading comprehension in your classroom?

On what basis do you work on reading comprehension?

What is reading motivation?

What does promoting reading motivation in your classroom/school mean to you?

How can you motivate students to read?

What role can you play in this?

To what extent do you consider a program focused on reading comprehension and reading motivation meaningful?

What elements should be included in such a program?

What conditions are important for its success?

Interview 2

What is reading comprehension?

How do you approach reading comprehension in your classroom?

On what basis do you work on reading comprehension?

Are there any elements that differ from before this professional development? If so, which ones?

What is reading motivation?

What does promoting reading motivation in your classroom/school mean to you?

How can you motivate students to read?

What role can you play in this?

Are there any elements that differ from before this professional development? If so, which ones?

To what extent did you find this program on reading comprehension and reading motivation meaningful?

What needs do you still have to work on?

References

- Bandura, A. (1978). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavorial change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1989). Regulations of cognitive processes through perceived self-efficacy. Developmental Psychology, 25(5), 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basma, B., & Savage, R. (2023). Teacher professional development and student reading in middle and high school: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Teacher Education, 74(3), 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilge, H., & Kalenderoğlu, İ. (2022). The relationship between reading fluency, writing fluency, speaking fluency, reading comprehension, and vocabulary. Eğitim ve Bilim, 47, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blömeke, S., Busse, A., Kaiser, G., König, J., & Suhl, U. (2016). The relation between content-specific and general teacher knowledge and skills. Teaching and Teacher Education, 56, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blömeke, S., Dunekacke, S., & Jenßen, L. (2017). Educational and psychological determinants of prospective preschool teachers’ beliefs. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal Cognitive, 25, 885–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blömeke, S., Gustafsson, J. E., & Shavelson, R. J. (2015). Beyond dichotomies: Competence viewed as a continuum. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 223, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blömeke, S., Jentsch, A., Ross, N., Kaiser, G., & König, J. (2022). Opening up the black box: Teacher competence, instructional quality, and students’ learning progress. Learning and Instruction, 79, 101600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blömeke, S., & Kaiser, G. (2017). Understanding the development of teachers’ professional competencies as personally, situationally and socially determined. In J. Clandinin, & J. Husu (Eds.), International handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 783–802). Sage Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaerds-Hazenberg, S. T. M., Evers-Vermeul, J., & van den Bergh, H. H. (2024). Text structure instruction in primary education: Effects on reading, summarization, and writing. Pedagogische Studiën, 101(1), 30–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. International Journal of Transgender Health, 24(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabell, S. Q., & Hwang, H. J. (2020). Building content knowledge to boost comprehension in the primary grades. Reading Research Quarterly, 55, S99–S107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervetti, G. N., Wright, T. S., & Hwang, H. J. (2016). Conceptual coherence, comprehension, and vocabulary acquisition: A knowledge effect? Reading and Writing, 29(4), 761–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M., Beckwith, V., Levy, B., Gulati, S., Macam, A. A. F., Saxena, T., & Suwarningsih, D. P. S. (2022). Navigating researcher positionality in comparative and international education research: Perspectives from emerging researchers. International Education Journal-Comparative Perspectives, 21(2), 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, D., & Hollingsworth, H. (2002). Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(8), 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. (2009). Inquiry as stance: Practitioner research for the next generation. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conradi, K., Jang, B. G., & McKenna, M. C. (2014). Motivation terminology in reading research: A conceptual review. In Educational psychology review (Vol. 26, pp. 127–164). Springer Science and Business Media, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Leaning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Davoudi, M., & Hashemi Moghadam, H. (2015). Critical review of the models of reading comprehension with a focus on situation Models. International Journal of Linguistics, 7, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E., Vallerand, R., Pelletier, L., & Ryan, R. (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist, 26(3–4), 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meyer, I., Berlamont, L., Hoedt, L., Janssens, R., Lermytte, A., Warlop, N., & van Braak, J. (2023). Vlaams rapport PISA2022. Universiteit Gent. [Google Scholar]

- De Meyer, I., Janssens, R., Warlop, N., Van Keer, H., De Wever, B., & Valcke, M. (2019). PISA in focus: 7 plezier in Lezen. Vlaamse resultaten van PISA2018. Universiteit Gent. [Google Scholar]

- De Naeghel, J., & Van Keer, H. (2013). The relation of student and class-level characteristics to primary school students’ autonomous reading motivation: A multi-level approach. Journal of Research in Reading, 36(4), 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Naeghel, J., Van Keer, H., & Vanderlinde, R. (2014). Strategies for promoting autonomous reading motivation: A multiple case study research in primary education. Frontline Learning Research, 2(1), 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Naeghel, J., Van Keer, H., Vansteenkiste, M., Haerens, L., & Aelterman, N. (2016). Promoting elementary school students’ autonomous reading motivation: Effects of a teacher professional development workshop. The Journal of Educational Research, 109(3), 232–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Naeghel, J., Van Keer, H., Vansteenkiste, M., & Rosseel, Y. (2012). The relation between elementary students’ recreational and academic reading motivation, reading frequency, engagement, and comprehension: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 1006–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L. M. (2011). A primer on effective professional development. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(6), 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L. M., & Garet, M. S. (2015). Best practices in teachers’ professional development in the United States. Psychology, Society & Education, 7(3), 252–263. [Google Scholar]

- Didion, L., Toste, J. R., & Filderman, M. J. (2020). Teacher professional development and student reading achievement: A meta-analytic review of the effects. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 13(1), 29–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, N. K., Pearson, P. D., Strachan, S. L., & Billman, A. K. (2011). Essential elements of fostering and teaching reading comprehension. In S. J. Samuels, & A. E. Farstrup (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (4th ed.). The International Reading Association. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, L., & Westphal, A. (2024). Teacher autonomy support counters declining trend in intrinsic reading motivation across secondary school. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 39, 4047–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filderman, M. J., Didion, L., Austin, C. R., Payne, B., Silvert, C., & Wexler, J. (2025). Teacher professional development for reading: A review of the state of the research. Reading Research Quarterly, 60(4), e70054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garces-Bacsal, R. M., Tupas, R., Kaur, S., Paculdar, A. M., & Baja, E. S. (2018). Reading for pleasure: Whose job is it to build lifelong readers in the classroom? Literacy, 52(2), 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geudens, A., Schraeyen, K., Bellens, K., Taelman, H., & Trioen, M. (2023). Effectief lessonderwijs voor het basis- en secundair onderwijs in Vlaanderen. Universiteit Antwerpen. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, S. (2020). The sciences of reading and writing must become more fully integrated. Reading Research Quarterly, 55, S35–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskey, T. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching, 8, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J. T. (2004). Teaching for literacy engagement. Journal of Literacy Research, 36(1), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbeck, A. F., & Kalchman, M. (2013). Professional development for conceptual change: Extending the paradigm to teaching reading comprehension in US schools. Professional Development in Education, 39(5), 638–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, W. A. (2024). The simple view of reading and its broad types of reading difficulties. Reading and Writing, 37(9), 2277–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, W. A., & Gough, P. B. (1990). The simple view of reading. Reading and Writing, 2(2), 127–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtveen, A. A. M., van Steensel, R., & de la Rie, S. (2019). De vele kanten van leesbegrip. Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam. [Google Scholar]

- King, F., Philip, P., & Pierre, T. (2023). A pragmatic meta-model to navigate complexity in teachers’ professional Learning. Professional Development in Education, 49(6), 958–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintsch, W. (1988). The role of knowledge in discourse comprehension—A construction integration model. Psychological Review, 95(2), 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintsch, W. (2005). An overview of top-down and bottom-up effects in comprehension: The CI perspective. Discourse Processes, 39(2–3), 125–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klassen, R. M., & Tze, V. M. C. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 12, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunter, M., Klusmann, U., Baumert, J., Richter, D., Voss, T., & Hachfeld, A. (2013). Professional competence of teachers: Effects on instructional quality and student development. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, A., Desimone, L., Stornaiuolo, A., Pak, K., Flores, N., Nichols, P., Polikoff, M., & Porter, A. (2024). Changes that stick. Phi Delta Kappan, 105(6), 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. H. (2025). A reflection of learners’ motivation to read, self-assessment, critical thinking, and academic well-being in extensive and intensive reading offline instruction: A focus on self-determination theory. Learning and Motivation, 89, 102093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, I., & Daniela, L. (2025). Teachers’ insights into the efficacy of the ‘reading circle’ project using English language teaching graded readers. Education Sciences, 15(1), 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumivero. (2020). NVivo (version 13 [2020, R1]). Available online: https://www.lumivero.com (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Magnusson, C. G., Luoto, J. M., & Blikstad-Balas, M. (2023). Developing teachers’ literacy scaffolding practices—Successes and challenges in a video-based longitudinal professional development intervention. Teaching and Teacher Education, 133, 104274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (2009). Promoting reasons for reading: Teacher practices that impact motivation (E. H. Hiebert, Ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Medina, A. L., Hancock, S. D., Hathaway, J. I., Pilonieta, P., & Holshouser, K. O. (2021). The influence of sustained, school-based professional development on explicit reading comprehension strategy instruction. Reading Psychology, 42(8), 807–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchie, E., Gobyn, S., De Bruyne, E., De Smedt, F., Schiepers, M., Vanbuel, M., Ghesquière, P., Van den Branden, K., & Van Keer, H. (2019). Effectieve, eigentijdse begrijpend leesdidactiek in het basisonderwijs. Wetenschappelijk eindrapport van een praktijkgerichte literatuurstudie. Vlaamse Onderwijsraad (VLOR). [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P. K., Wilkinson, I. A. G., Soter, A. O., Hennessey, M. N., & Alexander, J. F. (2009). Examining the effects of classroom discussion on students’ comprehension of text: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(3), 740–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestlog, E. B., Danielsson, K., & Jeppsson, F. (2024). Disciplinary content and text structures communicated in the classroom–pathways in science lessons. Linguistics and Education, 84, 101343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 results (Volume I). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/pisa-2018-results-volume-i_5f07c754-en/full-report.html (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 results (Volume I). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/pisa-2022-results-volume-i_53f23881-en/full-report.html (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Okkinga, M., van Steensel, R., van Gelderen, A. J. S., van Schooten, E., Sleegers, P. J. C., & Arends, L. R. (2018). Effectiveness of reading-strategy interventions in whole classrooms: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(4), 1215–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onderwijsinspectie. (2020). Begrijpend leesonderwijs in de basisscholen kwaliteitsvol? Onderwijsinspectie.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2019). Education at a glance 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/education-at-a-glance-2019_f8d7880d-en.html (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M., Lambright, K., & Wijekumar, K. (2024). Professional development in reading comprehension: A meta-analysis of the effects on teachers and students. Reading Research Quarterly, 59(3), 424–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwette, M., van Schooten, E., & de Glopper, K. (2020). Teachers’ reading promotion activities: Variation, structure and correlates. L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 20(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M., & Hendry, G. D. (2022). Sources of teacher efficacy in teaching reading: Success, sharing, and support. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 46(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, Theory, and Practice. In S. Neuman, & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for research in early literacy (pp. 97–110). Guidlford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schiefele, U., Schaffner, E., Möller, J., & Wigfield, A. (2012). Dimensions of reading motivation and their Relation to reading behavior and competence. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(4), 427–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, E., Reno, E., Chandler, B. W., Novelli, C., An, J. C., Choi, S., & McMaster, K. L. (2025). Effects of writing instruction on the reading outcomes of students with literacy difficulties in pre-kindergarten to fifth grade: A meta-analysis. Reading and Writing, 38(3), 627–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, C. (2002). Reading for understanding: Toward an R&D program in reading comprehension. RAND Corporation. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1465.html (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Steunpunt Toetsontwikkeling en Peilingen (STEP). (2021). Peiling project algemene vakken (PAV). Steunpunt Toetsontwikkeling en Peilingen. [Google Scholar]

- Svrcek, N. S., & Abugasea Heidt, M. (2022). Beyond levels and labels: Applying self-determination theory to support readers. Literacy, 56(4), 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiba, C. (2023). Motivation to explicitly teach reading comprehension strategies after a workshop. Reading & Writing-Journal of the Reading Association of South Africa, 14(1), a405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyer, M., Kim, J. S., Hale, E., Wantchekon, K. A., & Armstrong, C. (2019). Relations among intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation, reading amount, and comprehension: A conceptual replication. Reading and Writing, 32(5), 1197–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ammel, K., Aesaert, K., De Smedt, F., & Van Keer, H. (2021a). An analytic description of projectExpert: An instructional reading program for ninth grade vocational students. L1 Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 21, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ammel, K., Aesaert, K., De Smedt, F., & Van Keer, H. (2021b). Skill or will? The respective contribution of motivational and behavioural characteristics to secondary school students’ reading comprehension. Journal of Research in Reading, 44, 574–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Broek, P., & Helder, A. (2017). Cognitive processes in discourse comprehension: Passive processes, reader-Initiated processes, and evolving mental representations. Discourse Processes, 54(5–6), 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Sande, L., van Steensel, R., Fikrat-Wevers, S., & Arends, L. (2023). Effectiveness of interventions that foster reading motivation: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 35(1), 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteelandt, I., Mol, S. E., Vanderlinde, R., Lerkkanen, M. K., & Van Keer, H. (2020). In pursuit of beginning teachers’ competence in promoting reading motivation: A mixed-methods study into the impact of a continuing professional development program. Teaching and Teacher Education, 96, 103154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteelandt, I., Mol, S. E., & Van Keer, H. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ reader profiles: Stability and change throughout teacher education. Journal of Research in Reading, 45(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washburn, E. K., & Pierce, A. (2025). Teaching older struggling readers: Novice 4–12th general and special education teachers’ knowledge of foundational reading skills. Education Sciences, 15(6), 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A., Gladstone, J. R., & Turci, L. (2016). Beyond cognition: Reading motivation and reading comprehension. Child Development Perspectives, 10(3), 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L., Valcke, M., & Van Keer, H. (2021). Supporting struggling readers at secondary school: An intervention of reading strategy instruction. Reading and Writing, 34(8), 2175–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. (2018). Case Study research and applications. Design and methods (6th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).