Abstract

This paper presents an embedded gateway architecture that enables the seamless integration of Modbus-based industrial devices into Data Distribution Service (DDS) middleware for Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) applications. The gateway, implemented on an STM32 microcontroller, acts as both a Modbus master and DDS-XRCE client, mapping Modbus registers directly to DDS topics with a configurable Quality of Service (QoS). Experimental validation demonstrates median latencies below 15 ms in four out of five scenarios, a throughput of up to 80 messages/s, and stable scalability to 160 subscribers with moderate resource usage. The results confirmed the feasibility and efficiency of Modbus–DDS integration on resource-constrained platforms.

1. Introduction

The effective integration of data and communications into complex industrial systems has become one of the main challenges of Industry 4.0 and the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT). Heterogeneous field devices, traditional automation protocols, and modern middleware coexist in the same ecosystem, and the lack of standardized interoperability mechanisms can limit scalability and overall performance [1,2]. In this context, industrial information integration aims to seamlessly connect existing technologies with modern distributed platforms to achieve real-time visibility, predictive control, and operational flexibility in industrial production.

The IIoT is driving the convergence of legacy industrial networks and modern data-centric communication frameworks. However, many existing installations continue to rely on serial fieldbuses such as Modbus RTU [3,4], which lack interoperability with distributed architectures and cloud-oriented middleware. Bridging these legacy devices into publish–subscribe ecosystems remains a practical challenge, particularly under embedded resource constraints.

Several integration approaches have been proposed using OPC UA or MQTT gateways [5], but these often depend on centralized brokers or high-level operating systems, limiting their applicability to low-cost controllers. In contrast, the Data Distribution Service (DDS) [6,7] and its lightweight variant DDS-XRCE [8] provide a brokerless, real-time communication model that can be operated directly on microcontrollers.

This paper proposes a hybrid Modbus–DDS integration architecture in which a master station on an STM32 microcontroller collects data from Modbus devices and publishes them in a DDS domain. The main contributions of this study are as follows.

- A declarative YAML schema mapping Modbus registers to DDS topics (with endianness/word order, scaling, units, and data quality flags).

- An STM32/FreeRTOS gateway that acts as Modbus master + DDS-XRCE client, preserving sensor sampling timestamps end-to-end

- Evaluation of system performance (latency, scalability, and stability) in relevant IIoT scenarios.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides the background on Modbus and DDS/DDS-XRCE. Section 3 reviews the related work on IIoT middleware and industrial protocol integration. Section 4 details the Modbus–DDS mapping approach and its configuration. Section 5 presents the proposed STM32-based gateway architecture and its implementation. Section 6 reports the experimental results, including the latency, throughput, and scalability analyses. Section 7 concludes the paper and outlines the directions for future work.

2. Background

Modbus is one of the oldest and most widely used industrial communication protocols, introduced in 1979 by Modicon and currently maintained by the Modbus Organization. The most commonly used variants are Modbus RTU on serial interfaces (RS-232/RS-485) and Modbus TCP/IP for Ethernet communications. The protocol is of the master–slave type, where the master initiates all transactions and the slaves respond to requests to read or write registers [3].

The simplicity of the data frame, high interoperability, and low cost have led to its global adoption, particularly in SCADA, energy, and industrial processing systems. However, Modbus has major limitations, including the lack of native security mechanisms, low scalability in large topologies, and the absence of a distributed communication model. To address these challenges, recent standards have introduced extensions, such as the Modbus Security Protocol, which is based on TLS, for authentication and communication confidentiality [4].

The STM32 microcontrollers developed by STMicroelectronics are based on ARM Cortex-M architectures and offer a wide range of peripherals for industrial embedded applications, including universal asynchronous receiver–transmitter (UART), serial peripheral interface (SPI), inter-integrated circuit (I2C), controller area network (CAN), universal serial bus (USB), and Ethernet. In particular, the USART interface with RS-485 support is frequently used for Modbus RTU implementation in embedded systems.

The STM32 has a solid software ecosystem: HAL/LL Drivers, STM32CubeMX for quick configuration, and support for FreeRTOS or other real-time operating systems. These features make it a suitable platform for implementing industrial gateways with moderate resources capable of simultaneously running traditional protocols (Modbus) and distributed middleware (DDS-XRCE) [9].

Recent studies have shown that STM32 can be successfully used to implement industrial protocols, such as Modbus, BACnet, and OPC-UA, when combined with lightweight RTOSs and software stacks optimized for communication [10].

The Data Distribution Service (DDS), standardized by the Object Management Group (OMG), is a data-centric publish/subscribe communication middleware designed for critical distributed applications that require real-time performance. The DDS allows the definition of data topics that can be published by producers and consumed by subscribers without a direct relationship between participants. A major advantage of DDS is its support for configurable Quality of Service (QoS), which allows communication to be optimized for different requirements, such as low latency, reliability, durability, or data history. These features make DDS attractive for robotics, automotive, medical systems, and IIoT, where data synchronization and consistency are critical [11].

For microcontrollers and embedded devices with limited memory and processing power, OMG defined the DDS for eXtremely Resource-Constrained Environments (DDS-XRCE) standard. In this architecture, an XRCE client runs on the embedded device and communicates with an intermediate XRCE agent that provides transparent access to the full DDS domain [12].

DDS-XRCE significantly reduces complexity and resource consumption at the device level, enabling the integration of embedded sensors and gateways into large DDS ecosystems. Recent research has demonstrated competitive performance with millisecond latencies and scalability for hundreds of devices in industrial IoT networks [13].

From an industrial information integration perspective, the combination of Modbus, STM32, and DDS/DDS-XRCE provides a practical bridge between existing field equipment and modern distributed middleware. This ensures continuity for Modbus-based industrial infrastructures, scalability through DDS publish/subscribe with configurable QoS, efficiency through the use of STM32 as an embedded gateway platform, and security through the adoption of TLS extensions for Modbus and DDS Security mechanisms. This combination forms the basis of the architecture proposed in this study.

3. Related Works

The integration of field protocols (e.g., Modbus) with distributed data-oriented middleware has attracted increasing interest in recent years in the context of the industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) and Industry 4.0. Several major directions can be distinguished in the literature: gateways for traditional protocols (Modbus, CAN, and Profibus) to IP platforms (OPC-UA/MQTT), middleware for interoperability, and optimizations for embedded platforms with limited resources.

Recent work proposed edge architectures in which Modbus (including extensions) is transposed to OPC-UA on industrial processors (e.g., Sitara AM335x, with offload in PRU for the deterministic acquisition cycle), demonstrating feasibility and discussing overhead/complexity trade-offs when integrating with OPC-UA servers on Linux. These approaches emphasize the real-time separation of Modbus acquisition from the exposure of OPC-UA-modeled data to clients but typically run on SoCs rather than constrained MCUs [14,15]. In parallel, Modbus to MQTT remains attractive for cloud-centric integration; literature and industry reports highlight its simplicity but also its limitations in terms of fine-grained typing/QoS and its dependence on a central broker [16,17]. In application evaluations, MQTT tends to favor fast delivery in scenarios with more relaxed constraints, whereas OPC-UA provides semantic benefits and security at the cost of higher configuration costs and overheads [16].

DDS is often positioned as a data-centric (peer-to-peer) alternative to broker-based protocols with automatic discovery and granular QoS control (i.e., reliability, deadline, history, and liveliness). Recent syntheses and comparisons highlight that the choice depends on latency/jitter requirements, topology, and semantic modeling; OPC-UA excels at information modeling, whereas MQTT remains very simple to operate and is more lightweight. Updated comparisons (including in unified namespace contexts) show that each technology has its strengths depending on the architectural layer (edge vs. cloud) and task profile [18,19].

To implement the DDS model on an MCU, the DDS-XRCE standard adopts a client–agent architecture, where the agent represents the client in the DDS data space. Updated documentation and experimental evaluations show significant footprint reductions and support the best effort/reliable modes. Micro-ROS, based on Micro XRCE-DDS, demonstrated improvements in predictability and execution in recent works (e.g., PoDS planner), including on ARM Cortex-M [13,20,21,22]. However, the literature rarely addresses end-to-end direct Modbus to DDS/DDS-XRCE integration on the MCU; most results are network micro-benchmarks or generic sensor demos, without formal mapping of Modbus registers and without exhaustive measurements of resources (RAM/Flash/CPU/energy) and jitter percentiles (P95/P99).

In recent years, several papers have analyzed the coexistence of OPC-UA and MQTT in a factory-level unified namespace to avoid “information islands.” Performance evaluations in such frameworks confirm that decoupling semantics (OPC-UA) from lightweight transport (MQTT) is useful; however, it introduces operational complexity and does not address strict latency/jitter requirements. Here, a data-centric layer, such as DDS, can cover niches with tougher constraints, especially when the endpoints are heterogeneous (edge + MCU). This literature supports the relevance of direct Modbus-to-DDS mapping to populate a coherent data space without a broker [19].

Although Ethernet-based fieldbuses, such as PROFINET, EtherCAT, and Ethernet/IP, provide deterministic high-speed communication for modern installations, the majority of brownfield industrial systems remain RS-485-based. Therefore, this study focuses on Modbus RTU as a representative low-cost legacy interface, bridging it to modern distributed middleware via DDS-XRCE.

MQTT Sparkplug B and OPC UA Pub/Sub provide alternative publish/subscribe semantics but remain broker-centric or resource-heavy for microcontrollers, respectively. DDS offers a peer-to-peer data exchange with a configurable QoS and lightweight XRCE client–agent model, making it more suitable for embedded gateways. Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of representative IIoT middleware technologies based on published performance studies [13,16,17,18,19,20,23]. DDS and DDS-XRCE implement a peer-to-peer data-centric model that avoids broker latency and allows deterministic quality-of-service (QoS) control, achieving single-digit millisecond latencies on microcontrollers. MQTT Sparkplug B simplifies the message structure but depends on a broker, whereas OPC UA Pub/Sub over MQTT adds semantic richness at the cost of higher resource usage and configuration complexity. These comparisons further justify the selection of DDS-XRCE for embedded gateway implementations, such as the STM32-based design proposed in this paper.

Table 1.

Comparison of Middleware Alternatives for IIoT Integration [13,16,17,18,19,20,23].

4. Modbus–DDS Mapping

Modbus provides a 16-bit register-oriented interface, whereas DDS exposes a type-oriented, QoS- and time-oriented publish/subscribe model. In practice, modern systems need to “translate” dense local Modbus streams into explicit, interoperable DDS messages. This section proposes a method for mapping the Modbus protocol to DDS: a description file interpreted by the gateway that separates the semantics (what a signal represents) from the Modbus query type (how it is read).

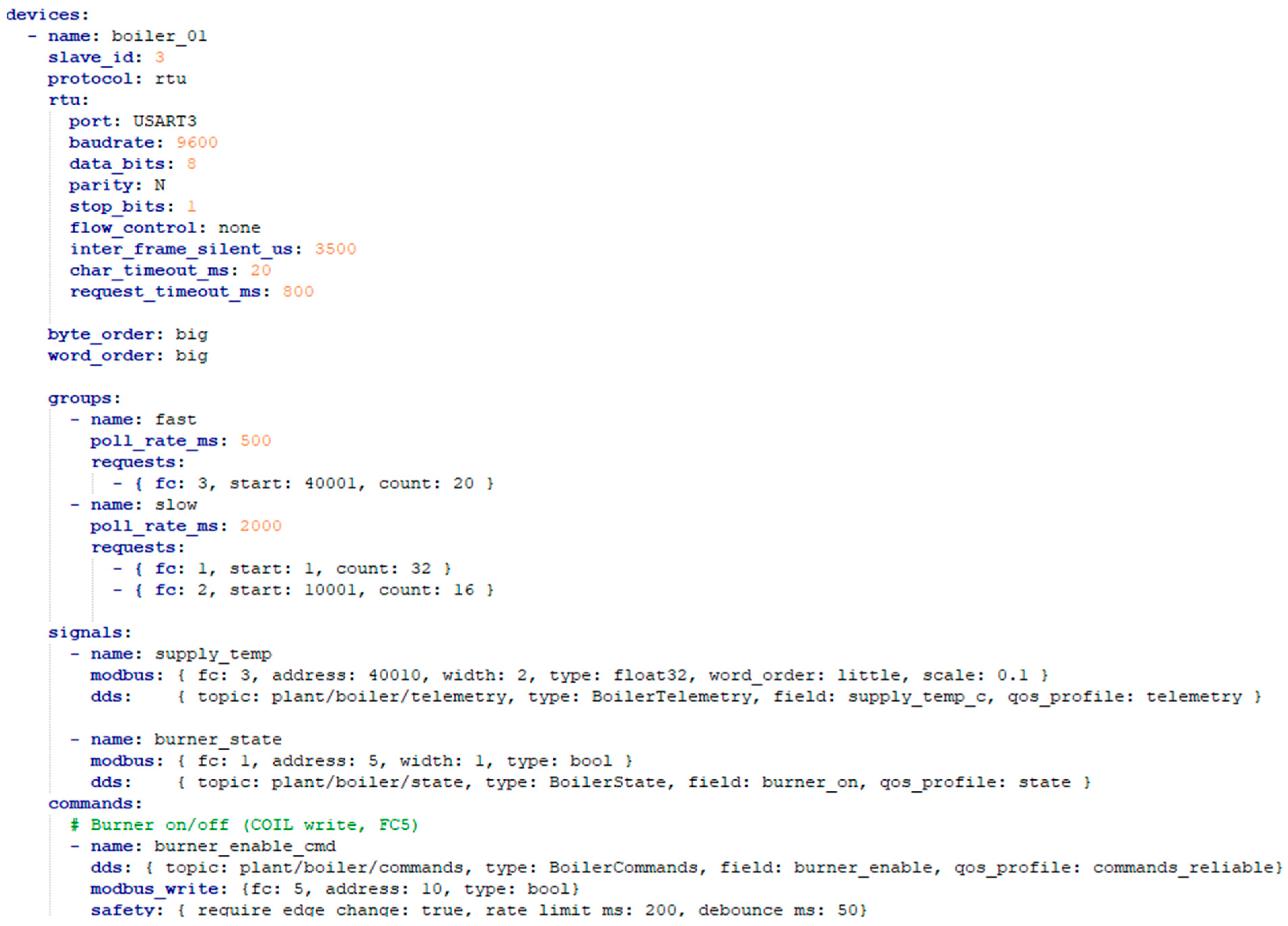

At the heart of the proposal is a description file (of the YAML type). It is not a simple “address inventory”; it is a formal narrative about what signal we read, how we reconstructed it and where we published it. In practice, for each device, we describe the identity (unit ID), query policy (groups of requests with different rates), decoding rules (endianness, word order, target type), adjustments (scale, offset), and, crucially, the destination in the DDS (topic, type, field). This description becomes the “source of truth”: the gateway interprets these files to perform the translation from Modbus to DDS and vice versa. Execution follows a short and predictable loop: the gateway executes the Modbus requests defined in groups, caches the responses, marks the sampling time, scans the signals, decodes the values according to the declared rules, evaluates the quality, and publishes the results on the designated DDS topics. Read failures propagate as BAD_COMM for dependent signals. An example of such a file is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Example of a YAML file that describes a device.

A description file for a Modbus–DDS gateway functions as a metadata description of the dialog between a device that “thinks” in registers and an infrastructure that publishes typed messages. The text usually begins with a presentation of the execution context, that is, the version of the scheme and the identity of the gateway instance. This is where the system’s rhythm and patience are set—the default query rate, connection and response times, and number of retries—not as implementation details, but as parameters of behavior.

The section dedicated to devices introduces each piece of equipment as an actor. For a UART/RS-485 connection, the file specifies the serial port, speed, parity, and frame structure, as well as the physical characteristics of the bus, such as the required quiet time between frames. The same section also specifies the byte order in the 16-bit register and the register order when the value exceeds 16 bits (little or big endian). These two seemingly minor conventions determine the exact meaning of each byte string.

To avoid wasting queries, the readings were grouped, each with its own polling rate/period. Thus, a group becomes a coherent sample in time: the gateway launches a sequence of compact requests, caches the responses, and marks sampling time. In this architecture, signals are not read individually from the wire but are extracted later from the common basket, each with its own set of semantic rules. This separation—groups for efficiency, signals for meaning—allows the same harvest of registers to feed distinct DDS streams without duplicating the traffic on the bus.

The heart of the file is, in fact, the description of the signals. Each signal declares its origin in Modbus through its code function, address, and width in registers; it specifies, if necessary, its own byte or word order when a manufacturer remains non-compliant with the rest of the device; and it applies the scalings and offsets that anchor it in the physical units. Then, it specifies its destination: a DDS topic, an IDL type, and a field in which the value will be saved. If the raw value hides a composite field, as is the case in bit fields, the file makes the mapping visible; each named bit is transmitted in its own field in the DDS message, thus cleaning the semantics for data consumers. Sometimes, a numeric code requires a legend; then, a section of enumerations translates it into canonical text without altering the numeric transport.

The quality of each publication is indicated in a footnote. A successful read that complies with the declared rules carries the quality “good,” and a delay beyond the agreed term becomes “outdated.” A deviation from physical ranges explicitly defines “out of range,” and silence on the bus marks “faulty communication.” These qualifiers are designed to be consumed by algorithms and operators alike so that decisions consider the context, not just numbers.

The DDS types maintained sobriety. A common header with the source name, Modbus unit identifier, sampling time expressed in nanoseconds, and quality code precedes the actual field. This simple but consistent structure allows for reliable temporal correlations and auditability throughout the data path. Simultaneously, the publication policy, that is, the QoS profiles, is invoked by name, not by scattered recipes: fast telemetry prefers the delivery of the “freshest” values, whereas states and alarms require reliability and short persistence so that a delayed subscriber can recover what is important.

When the system not only receives data but also sends them to the device, the file gains a second section, commands. Commands arrive on a dedicated DDS topic and are subject to a double filter: a semantic filter, which ensures that the desired values make sense, and an operational filter, which tempers the pace of change to avoid oscillations. The transformation back into the register applies the scalings symmetrically in the declared order of the bytes and words.

The YAML schema proposed in this work conceptually resembles the W3C Thing Description and the Asset Administration Shell (AAS) Asset Interface Description. However, it is intentionally simplified and declarative, enabling direct interpretation on constrained microcontrollers without external JSON-LD parsing. It serves as a lightweight alternative for representing Modbus–DDS mappings in IIoT edge nodes.

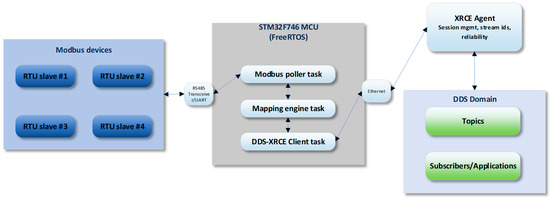

5. Proposed Architecture

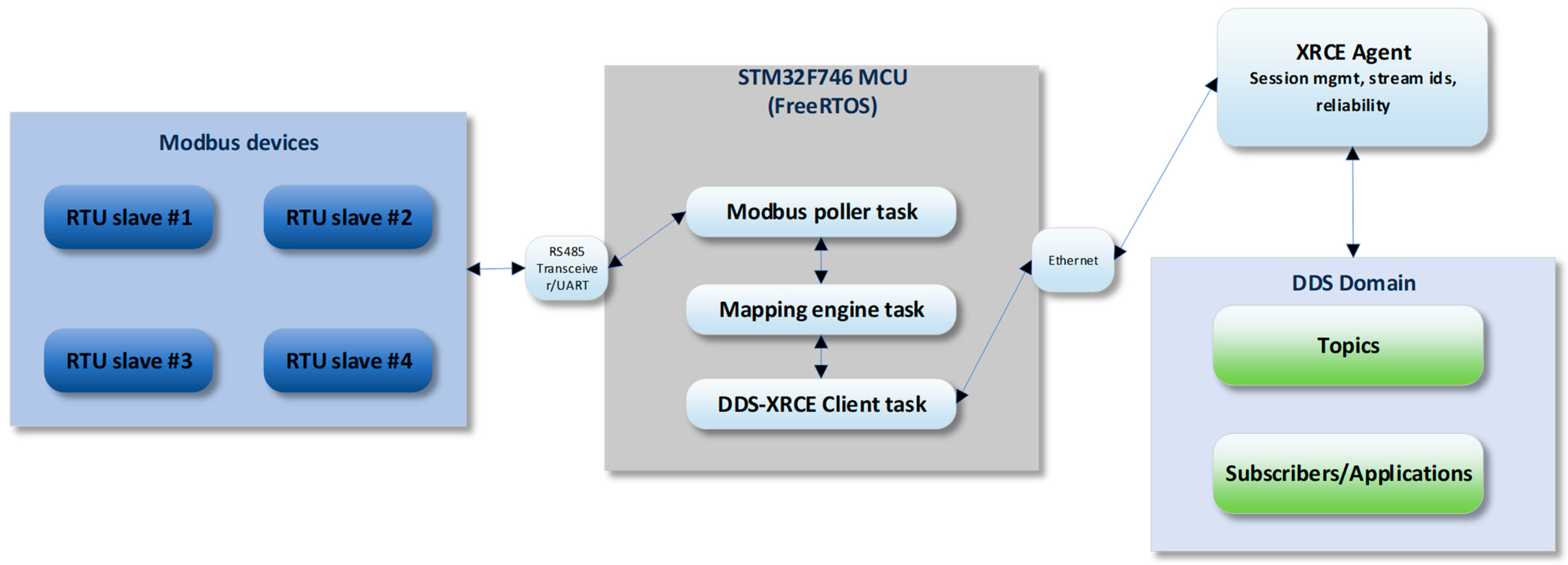

The proposed architecture aims to integrate Modbus-based industrial devices into the DDS domain using an embedded gateway with limited resources. The central element of this architecture is an STM32F746 microcontroller (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland) that acts simultaneously as a Modbus master station and DDS-XRCE client. Thus, data collected from traditional sensors and actuators are converted into DDS messages and made available to a variable number of distributed consumers.

The architecture is structured into three levels. At the base of the system, field devices are connected via Modbus RTU (RS-485) or Modbus TCP/IP [3]. These provide raw values such as temperature, pressure, and vibrations, as well as logical states from industrial actuators. The intermediate level is represented by the STM32 gateway, which runs on FreeRTOS and integrates several software components: a Modbus query module, a mechanism for mapping registers to DDS topics, and an XRCE client capable of publishing the data. The upper level consists of the DDS domain itself, where the XRCE agent receives data from the gateway and distributes them to applications such as SCADA, real-time analysis systems, and cloud platforms.

The data flow occurs in four stages. First, the STM32 gateway periodically queries the Modbus slave devices. The read values were then normalized and mapped to data structures corresponding to DDS topics, each topic representing a type of process variable. Subsequently, the XRCE client on the microcontroller publishes this data to the agent, making it available in the DDS domain for further processing. Finally, subscribers receive the data in real time without the need for a direct connection to the Modbus devices and benefit from the QoS mechanisms offered by the DDS.

Figure 2 schematically illustrates the proposed architecture, showing the data flow from the sensors to the distributed applications. This approach has several advantages. First, it allows the reuse of existing industrial equipment without major modifications. Second, it extends the scalability of communication through the native publish/subscribe mechanisms of DDS, allowing the simultaneous connection of a large number of consumers to the same topic. In addition, the flexibility offered by QoS parameters makes it possible to adapt data transmission to the requirements of each application, ensuring a balance between latency, reliability, and resource utilization. Finally, the integration of TLS extensions for Modbus and DDS Security mechanisms provides an additional level of protection for the transmitted data.

Figure 2.

End-to-end data path from Modbus devices to the DDS domain. The STM32/FreeRTOS gateway polls Modbus RTU, parses frames, applies a YAML-defined register to topic mapping (endianness, word order, scaling, and units), and publishes via a DDS-XRCE client to an XRCE Agent that bridges into the DDS domain.

6. Experimental Results and Discussion

To validate the proposed architecture, experiments were performed using an experimental setup that is representative of IIoT applications. The gateway was implemented on an STM32F746G-DISCO board (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland) configured with an RS-485 transceiver and an Ethernet module. The slave devices included three industrial sensors connected via Modbus RTU and a digital actuator, whereas the DDS infrastructure consisted of an XRCE agent running on a Linux server and integrated into a Cyclone DDS domain. A SCADA dashboard and a real-time analysis module developed in Python 3.10 were used as consumer applications.

We conducted all experiments on an STM32F746 microcontroller (STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland) (Arm Cortex-M7 MCU) running at 216 MHz with 1 MB Flash, 340 KB RAM, and 128-Mbit Quad-SPI Flash memory. The firmware runs FreeRTOS v10.5 with a 1 ms tick, and UART DMA is enabled for serial I/O. The Modbus link uses an SN65HVD1780 RS-485 transceiver (Texas Instruments, Dallas, TX, USA) on a two-wire, half-duplex bus of approximately 10 m in length, terminated with 120 Ω at both ends; a common signal ground is provided across all nodes. The gateway hosts the Micro XRCE-DDS Client v2.4 and publishes it to an XRCE Agent v2.4 running on a PC. The DDS backbone is Cyclone DDS v0.10 (domain ID 20) reachable over a 100 Mbps Ethernet LAN with sub-millisecond latency. Measurements timestamped the Modbus request, device response, and DDS publish events; unless otherwise stated, each scenario comprised 10,000 samples. The Modbus topology includes one to four slave devices, depending on the scenario, with termination at both ends of the bus.

The tests were designed to cover the scenarios presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Matrix of test scenarios performed (RS-485/Modbus RTU).

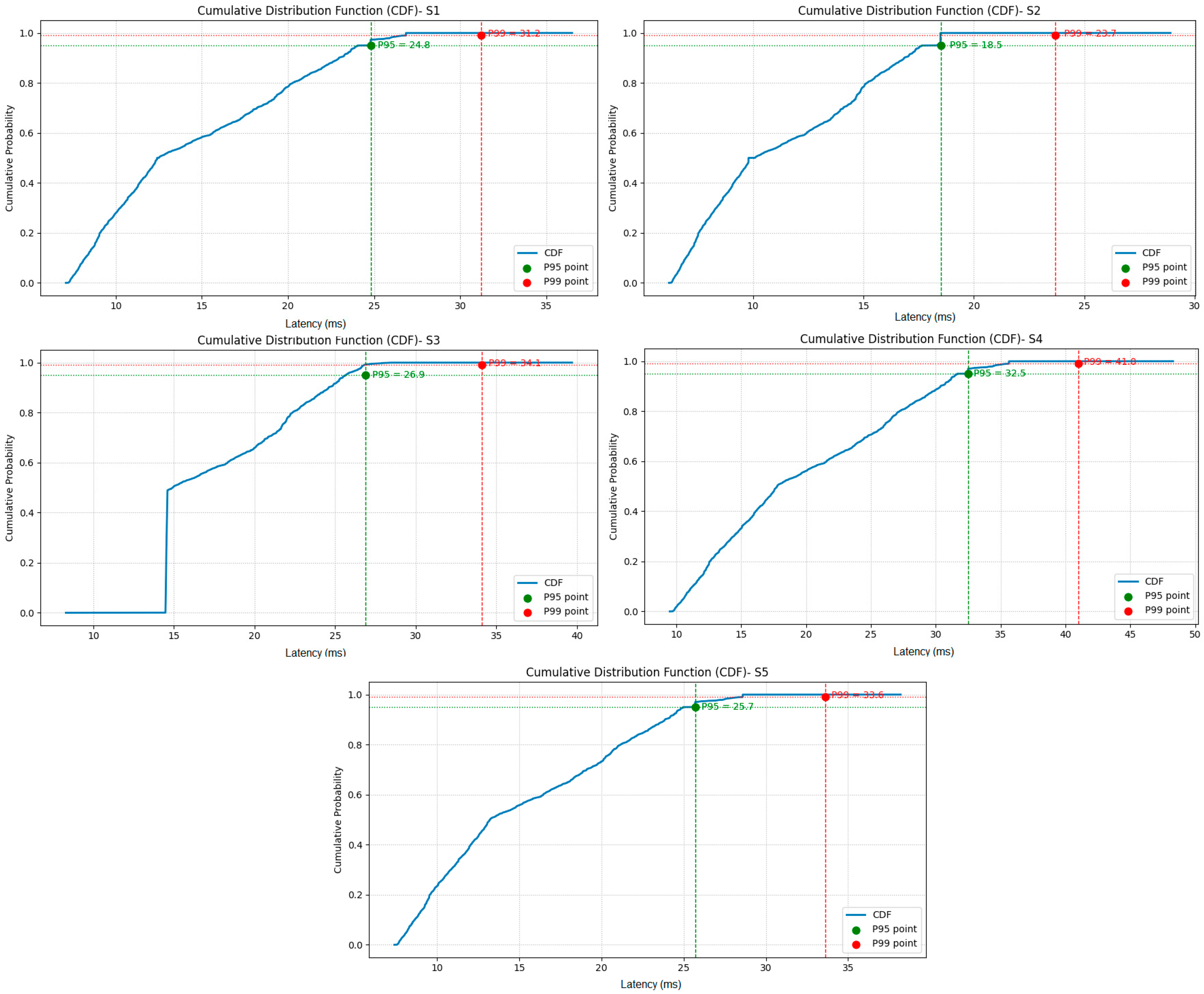

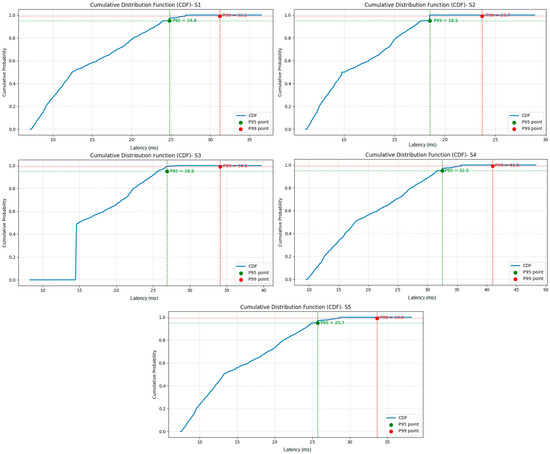

The results are presented in Table 3. With Modbus/RS-485 at 115,200 kbps, the best median end-to-end latency was 9.8 ms in the reliable mode (S1), with P95 = 18.5 ms and P99 = 23.7 ms. Shortening the polling period to 50 ms (S2) increased the median to 12.4 ms (P95 24.8 ms), whereas a heavier configuration with four slaves and 200 ms polling (S3) yielded a 14.6 ms median (P95 26.9 ms). The only best-effort case (S4) showed a higher delay—17.8 ms median, 32.5 ms P95—than otherwise similar reliable runs. A mixed read/write workload at 50 ms (S5) produced a 13.2 ms median and 25.7 ms P95. Across scenarios, the gap between the median and P95 remained within approximately 10–22 ms, indicating bounded jitter under our conditions.

Table 3.

Latency statistics (end-to-end: request for publication).

Figure 3 illustrates the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of the end-to-end latencies for S1–S5 scenarios. The similarity of the curves across the scenarios also indicates that increasing the number of subscribers or Modbus registers does not significantly affect the timing determinism.

Figure 3.

Cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of end-to-end latencies for the S1–S5 scenarios from Table 3. Each curve represents the cumulative probability that latency is less than or equal to a given value. For instance, a CDF value of 0.95 corresponds to the 95th percentile (P95).

Notably, Modbus RTU follows a strict master–slave command–response paradigm, in which only the master initiates transactions, and each slave responds sequentially. Consequently, increasing the number of slave devices does not proportionally increase the CPU utilization of the STM32 gateway because the Modbus task is executed in a deterministic polling loop with a fixed cycle time. The processing overhead per request remains nearly constant; however, the effective polling rate for each slave changes. As the number of slaves increases, the gateway employs a round-robin scheduling mechanism to sequentially query each device, which extends the total acquisition cycle but preserves real-time determinism and a low MCU load. Therefore, scalability in Modbus-based topologies is primarily limited by the serial bus bandwidth and response time rather than the processing capacity. This property explains the stable CPU utilization observed in our experiments, even when multiple slaves and subscribers were active.

For scenario 6 (S6), the number of subscribers gradually increased from 2 to 160, and the processor load did not change, remaining at 17%.

To evaluate the publication throughput, the number of DDS topics generated per Modbus polling cycle was gradually increased; each Modbus query can produce multiple DDS publications corresponding to individual process variables. By expanding the number of mapped signals while maintaining the same polling rate, the test effectively measured the upper limit of the publication capacity of the gateway without altering the Modbus communication timing. In terms of publishing capacity, the gateway sustained approximately 80 messages per second at a 100 ms polling interval, with an average CPU utilization of approximately 55% on the microcontroller.

In the DDS-XRCE architecture, the agent handles participant management externally; thus, scalability primarily depends on network and agent performance. Prior benchmarks [13,21] demonstrated stable operation with hundreds of XRCE clients, suggesting that the proposed approach can be extended proportionally.

Several studies have confirmed that DDS-XRCE achieves lower latency and better scalability than broker-based middleware when operating under resource constraints (Table 1). Because DDS-XRCE adopts a peer-to-peer data-centric architecture with binary serialization and pre-allocated memory pools, message dispatch avoids the context switching and buffering delays introduced by MQTT or OPC UA Pub/Sub brokers. Experiments reported in [13,20] show end-to-end latencies of 5–15 ms for DDS-XRCE clients running on ARM Cortex-M microcontrollers, compared with 20–60 ms for equivalent MQTT configurations on the same class of hardware [16,17]. In addition, the DDS-XRCE scales efficiently with the number of participants because discovery and QoS negotiation occur directly between endpoints through the XRCE Agent, eliminating the single-point bottleneck of broker systems. Evaluations in [18,19] demonstrate that peer-to-peer DDS domains can sustain hundreds of active publishers and subscribers with predictable jitter and bounded CPU utilization, which is an essential advantage in deterministic IIoT networks and embedded real-time controllers. These characteristics make DDS-XRCE particularly suitable for constrained gateways such as the STM32 platform used in this paper, where deterministic timing and low communication overhead are critical.

These results demonstrate that Modbus–DDS integration via an STM32 gateway is possible and efficient in terms of both performance and resource utilization. The latencies achieved meet the requirements of SCADA and IIoT applications, and the QoS mechanisms of DDS allow the transmission to be adapted to specific needs. In addition, the resources consumed by the microcontroller remained within acceptable limits, even in scenarios with high query frequencies or an increased number of subscribers to the service.

These results are directly applicable to smart switch controllers, where sub-15 ms latency ensures near real-time control, and the ability to scale to multiple subscribers enables simultaneous monitoring by SCADA dashboards and energy-management applications. Overall, the experiments demonstrate that the system performance is bounded primarily by serial communication timing rather than computational limits and that the DDS-XRCE agent effectively decouples subscriber scalability from the gateway processing load.

Although the proposed Modbus–DDS gateway achieved sub-15 ms latencies and stable scalability, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the throughput of the RS-485 Modbus channel inherently constrains the update rate as the number of connected devices increases, since the master–slave cycle is sequential and bandwidth-limited (≤115.2 kbps in our setup). Second, the current implementation does not include security validation for Modbus TLS or DDS Security profiles; these will be considered in future work.

7. Conclusions

This paper proposes an integration architecture between traditional industrial protocols and modern distributed middleware, with an STM32-based embedded gateway as its central element. The proposed solution demonstrates that Modbus devices can be efficiently integrated into a DDS domain using DDS-XRCE without the need for a complex intermediate infrastructure or expensive hardware equipment.

The experimental results confirmed that the latencies achieved (median below 15 ms in most scenarios) were compatible with the requirements of near-real-time IIoT and SCADA applications. Furthermore, the system demonstrated good scalability, being able to simultaneously serve up to 160 subscribers without major performance degradation. The QoS mechanisms offered by DDS proved essential for adapting communication to varying requirements, allowing a compromise between reliability and latency. The implementation on STM32 demonstrated that the necessary hardware resources remained moderate. A direct use case is the integration of Modbus-based smart switch controllers into DDS-enabled infrastructures, supporting energy-aware automation, predictive maintenance, and seamless interoperability with OPC-UA enterprise platforms

The main contributions of this study are as follows: a methodology for directly mapping Modbus registers to DDS topics is defined, the use of DDS-XRCE on a microcontroller with limited resources is validated, and the performance of the architecture is evaluated in realistic scenarios. In doing so, this study addresses a gap identified in the literature, where most existing solutions either do not use DDS as middleware or do not target small-scale embedded implementations.

Future research directions include extending the architecture with advanced security mechanisms by combining Modbus TLS with DDS Security standards to meet the increasingly stringent data protection requirements in critical infrastructures. Another direction is the integration of preprocessing and analysis capabilities at the gateway level by including machine learning algorithms on more powerful microcontrollers from the STM32H7 or STM32MPU family, which would enable local anomaly detection and reduce the data traffic. Finally, interoperability with other integration standards, such as OPC-UA, could extend the applicability of the proposed architecture, transforming it into a key element of smart manufacturing ecosystems and Industry 4.0.

Funding

This paper was supported by the North-East Regional Program 2021–2027, under Investment Priority PRNE_P1—A More Competitive, More Innovative Region, within the call for proposals Support for the Development of Innovation Capacity of SMEs through RDI Projects and Investments in SMEs, Aimed at Developing Innovative Products and Processes. The project is entitled “DIGI TOUCH NEXTGEN”, Grant No. 740/28.07.2025, SMIS Code: 338580.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Afrin, S.; Rafa, S.J.; Kabir, M.; Farah, T.; Bin Alam, S.; Lameesa, A.; Ahmed, S.F.; Gandomi, A.H. Industrial Internet of Things: Implementations, challenges, and potential solutions across various industries. Comput. Ind. 2025, 170, 104317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Antwi-Afari, M.F. The applications of Internet of Things (IoT) in industrial management: A science mapping review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 1928–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modbus Organization. MODBUS Application Protocol Specification V1.1b3. April 2012. Available online: https://www.afs.enea.it/project/protosphera/Proto-Sphera_Full_Documents/mpdocs/docs_EEI/Modbus_Application_Protocol_V1_1b3.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Modbus Organization. MODBUS/TCP Security Protocol Specification (MB-TCP-Security-v36). July 2021. Available online: https://assets.noviams.com/novi-file-uploads/modbus/pdfs-and-documents/MB-TCP-Security-v36_2021-07-30.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Găitan, V.G.; Zagan, I. Modbus Extension Server Implementation for BIoT-Enabled Smart Switch Embedded System Device. Sensors 2024, 24, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Kim, D.-K. A broker-embedded data distribution service for resource-constrained IoT environments. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2025, 47, 100909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Open Research Europe|Open Access Publishing Platform. Secure Integration of Extremely Resource-Constrained Nodes on Distributed ROS2 Applications. Available online: https://open-research-europe.ec.europa.eu/articles/3-113/v1 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- DDS for Extremely Resource Constrained Environments (DDS-XRCE), Version 1.0; Object Management Group: Milford, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.omg.org/spec/DDS-XRCE/1.0/PDF (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- STM32 Microcontrollers (MCUs)—STMicroelectronics. Available online: https://www.st.com/en/microcontrollers-microprocessors/stm32-32-bit-arm-cortex-mcus.html (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Latency Reduction and Packet Synchronization in Low-Resource Devices Connected by DDS Networks in Autonomous UAVs. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/23/22/9269 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Eclipse Cyclone DDS—Eclipse Cyclone DDS, 0.11.0. Available online: https://cyclonedds.io/docs/cyclonedds/latest/about_dds/eclipse_cyclone_dds.html (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- About the DDS for Extremely Resource Constrained Environments Specification Version 1.0. Available online: https://www.omg.org/spec/DDS-XRCE/1.0/About-DDS-XRCE (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Solpan, S.; Kucuk, K. DDS-XRCE Standard Performance Evaluation of Different Communication Scenarios in IoT Technologies. EAI Endorsed Trans. Internet Things 2022, 8, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventuneac, C.; Gaitan, V.G. Industrial Internet of Things Gateway with OPC UA Based on Sitara AM335X with ModbusE Acquisition Cycle Performance Analysis. Sensors 2024, 24, 2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventuneac, C.; Gaitan, V.G. Performance Evaluation of the Acquisition Cycle for an Original Modbus Extension IIoT Gateway Based on Sitara AM335x Processor. Adv. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2024, 24, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, L.; Pereira, F.; Lopes, H.; Lima, A.; Marujo, P.; Ottaviano, E.; Machado, J. OPC-UA in interoperability—A performance comparative testing. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Electronics April 2024: Comparing Dds and Mqtt. Available online: https://ne.mydigitalpublication.co.uk/articles/comparing-dds-and-mqtt (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Yu, X.; Ha, S.; Queralta, J.P.; Westerlund, T. Comparison of Middlewares in Edge-to-Edge and Edge-to-Cloud Communication for Distributed ROS 2 Systems. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2024, 110, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, L.; Silva, M.; Vale, G.; Avram, C.; Lopes, H.; Pereira, F.; Leal, N.; Machado, J. OPC UA and MQTT performance analysis within a unified namespace context. Internet Things 2025, 33, 101734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Ji, D.; Yi, W. Improving Real-Time Performance of Micro-ROS with Priority-Driven Chain-Aware Scheduling. Electronics 2024, 13, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Version 3.0.1—eProsima Micro XRCE-DDS 3.0.1 Documentation. Available online: https://micro-xrce-dds.docs.eprosima.com/en/latest/notes.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Stadnik, B.; Wymysłowski, A. Overview Analysis of Micro-ROS System as an Embedded Solution for Microcontrollers in Automatics and Robotics Applications. Prz. Elektrotech. 2024, 1, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eclipse Foundation. Sparkplug™ B Specification Version 3.0; Eclipse Foundation: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://sparkplug.eclipse.org (accessed on 5 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).