1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LiBs) play a pivotal role in the global shift toward renewable energy systems [

1]. Among the various cathode chemistries, lithium iron phosphate (LFP) has become widely favored in electric vehicles (EVs) and electrochemical energy storage (EES) applications due to its inherent safety profile and cost-effectiveness. In real-world configurations, individual cells are integrated into modules and packs, where they encounter mechanical constraints during operation [

1,

2,

3]. These constraints, combined with the natural expansion behavior of prismatic cells, induce internal pressures that must be accounted for. Such expansion pressure has direct implications for both the safety and performance of LiBs, significantly influencing their durability and operational lifespan. As a result, tracking pressure evolution has emerged as a valuable method for estimating the state of charge (SOC)and forecasting the state of health (SOH) [

4,

5], within advanced battery management systems (BMS).

To counteract risks associated with uncontrolled deformation, a controlled level of compression is intentionally applied during cell stacking. This mechanical preloading serves to stabilize internal interfaces and preserve electrochemical–mechanical cohesion. When appropriately applied, moderate compression improves interparticle connectivity, facilitates the release of trapped gases [

6,

7], mitigates electrode delamination, reduces gas evolution, and slows the rate of capacity degradation [

8,

9]. However, excessive compression can be detrimental: it constricts pores within electrodes and separators, impedes ion transport, elevates internal resistance, and intensifies parasitic reactions [

10,

11,

12,

13]. These opposing effects underscore the need for precise optimization of compressive forces. Empirical studies illustrate this balance. Collectively, these findings affirm that while mechanical compression is essential for maintaining cell integrity, its magnitude must be carefully calibrated to avoid compromising battery performance and longevity.

Europe has set an ambitious goal to become the first climate-neutral continent by 2050, transitioning away from fossil fuels toward renewable energy sources such as hydropower. As part of this strategy, the European Union targets a renewable energy share of 42.5% by 2030—an increase from 23% in 2022. However, the inherent intermittency of renewables like wind and solar, compounded by variable weather conditions, presents significant operational challenges [

14,

15]. Refs. [

16,

17,

18] achieving climate neutrality demands a rapid transformation of the energy system to ensure dynamic balancing of supply and demand. This includes the efficient storage and reintegration of surplus energy. While conventional batteries face technical and economic constraints, artificial intelligence is being increasingly deployed to modernize hydropower infrastructure, thereby reinforcing its role within the renewable energy mix. Addressing these challenges requires robust infrastructure adaptation and innovative energy solutions [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

Energy storage is a cornerstone of the renewable energy transition. Compressed Air Vessel (CAV)—functioning as water-air batteries—offers a promising uphill storage solution using pumps and hydro turbines. In this configuration, renewable electricity powers water pumps that transfer water into tanks, compressing the air within. The stored energy is later recovered via Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES) [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

While battery-based storage systems are widely used, they suffer from rapid degradation, environmental concerns, and scalability limitations. In contrast, CAV storage provides a degradation-free cycling solution that is environmentally sustainable. These systems can be implemented underground or uphill, offering modularity, scalability, and rapid deployment. CAVs enable long-duration energy storage with minimal spatial footprint [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Climate change intensifies the need for resilient energy grids, as extreme weather events disrupt supply and demand patterns. Decarbonizing the electricity sector by replacing fossil fuels with low-carbon sources is essential for grid stability and energy security. Flexible power systems and robust storage technologies are vital to prevent renewable energy curtailment. Long-duration storage is critical for enhancing system flexibility. Despite its advantages, BESS or CAV deployment is lagging behind rising demand, underscoring the need for coordinated governmental action to meet net-zero targets and avoid grid instability [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, over two-thirds of global greenhouse gas emissions originate from energy production. Since 2000, more than 650 GW of solar and wind capacity has been installed globally. However, in 2020 alone, over 250 TWh of renewable electricity was curtailed, contributing to 180 million tons of CO

2 emissions. Reducing curtailment enhances utilization rates and capacity factors, thereby improving investment returns [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

Pumped-storage remains the dominant energy storage technology worldwide, accounting for 96% of the 176 GW installed capacity as of mid-2017. It offers superior lifecycle performance, rapid response times, high technical maturity, and grid inertia. Compared to other technologies—such as Lithium-Ion (LFP), Lead Acid, Vanadium Redox Flow and air vessels demonstrate clear advantages in durability, responsiveness, and cost-effectiveness [

39,

40].

Comparative analyses of energy storage technologies reveal that pumped-storage with CAV solutions significantly reduce effective capital expenditures (CAPEX) relative to battery and compressed air systems. With lifespans ranging from 50 to 100 years, it offers a robust lifecycle advantage. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) emphasizes the role of pumped storage with CAV in balancing energy supply and demand, facilitating reliable low-carbon alternatives. Hydropower, with over 1330 GW of global installed capacity, is central to renewable electricity generation. Its expansion—including pumped storage—is essential to meet energy transition goals and limit global temperature rise below 2 °C. The IEA Net Zero scenario projects a doubling of hydropower capacity by 2050, requiring an additional 1300 GW [

41,

42].

Despite these advances, the absence of an integrated hybrid energy model incorporating BESS or CAVs for micro-grid renewable energy storage remains a gap [

43,

44,

45]. This motivates ongoing research into combined solutions and integrated modeling approaches. The following questions help to prove the innovative components developments: In what innovative ways does the mathematical modeling of fluid flow within compressed air vessels advance beyond traditional hydropower and pumping system analyses? How does the laboratory evaluation of compressed air vessels introduce novel insights into efficiency and storage capacity compared to conventional energy storage technologies? What innovative contributions do solver-based simulations make to the design of hybrid energy systems integrating compressed air vessels with renewable energy sources? How does the analysis of operational behavior and adaptability reveal innovative pathways for enhancing resilience and flexibility in hybrid energy systems?

2. Methods and Materials

The proposed research methodology is structured into four integrated phases to develop a comprehensive hybrid energy model utilizing compressed air vessels as energy storage units. These vessels act as dynamic batteries, storing potential energy that can be dispatched when intermittent renewable sources such as wind and solar are unavailable. The first phase involves the mathematical characterization of fluid flow within the system, focusing on both pumping and hydropower generation modes. This includes modeling all system components to capture pressure dynamics and flow behavior. The second phase centers on laboratory testing to evaluate the performance, efficiency, and storage capacity of these storage configurations. In the third phase, hybrid energy system configurations are developed using solver-based simulations to explore various combinations of renewable inputs and storage strategies. These models incorporate batteries or compressed air vessels to optimize energy dispatch and system resilience. Finally, the fourth phase focuses on analyzing the operational behavior and adaptability of each hybrid configuration. This includes assessing the system’s ability to store surplus energy—generated during periods of low demand—in batteries or compressed air vessels, and its capacity to release stored energy as hydropower during peak demand (

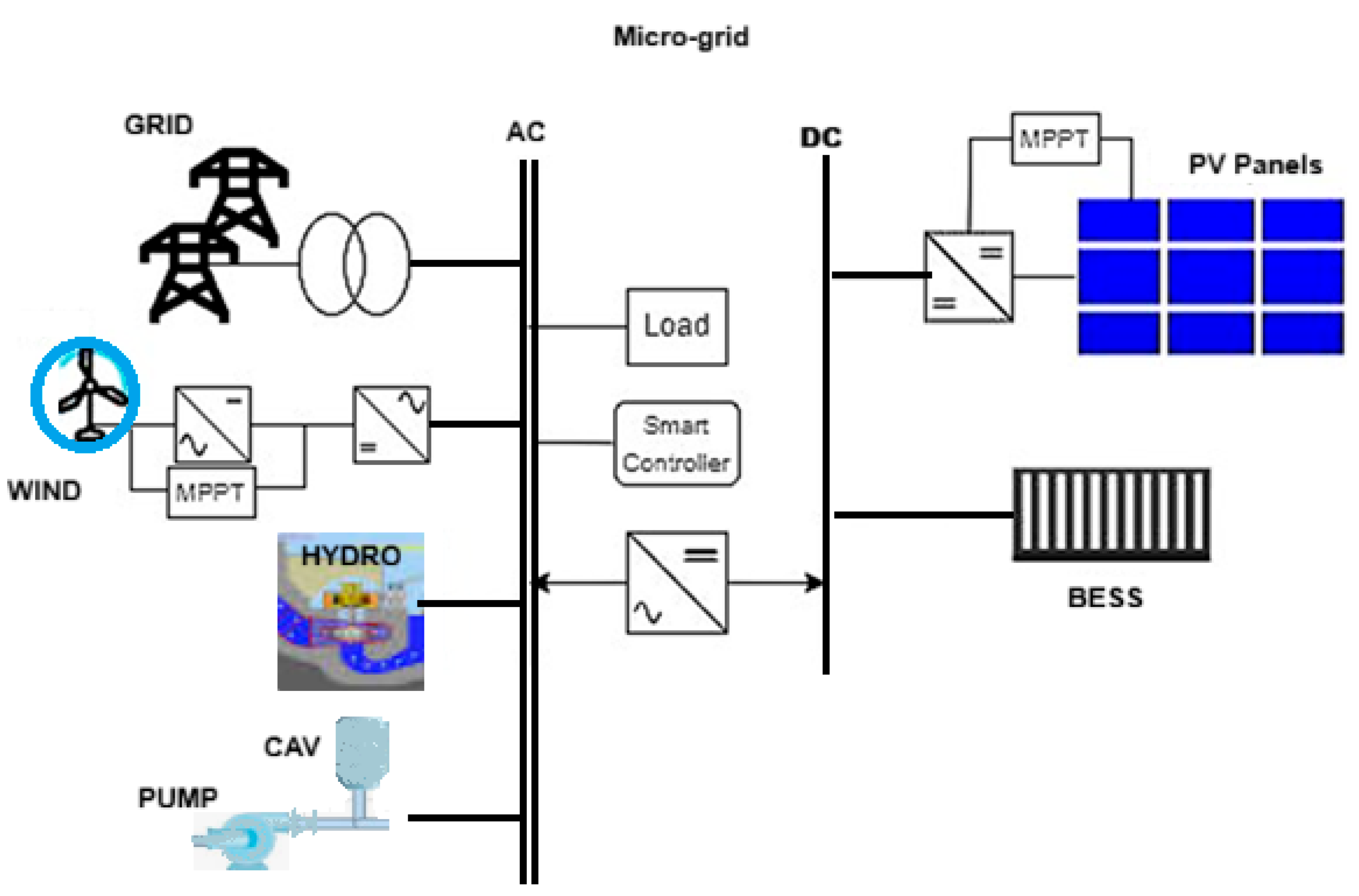

Figure 1).

Figure 1 presents a schematic representation of a hybrid micro-grid system that integrates multiple energy sources across both AC and DC domains to ensure efficient, resilient, and sustainable power distribution. On the AC side, the system incorporates three primary sources: utility GRID power, a WIND turbine, and a HYDRO unit equipped with a pump and a Compressed Air Vessel (CAV), which operates as a water-air battery. Each of these sources is connected through a Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) device, optimizing energy extraction under varying operational conditions. These sources feed into a common AC bus that supplies power to the system’s Load and a Smart Controller, which presumably manages real-time energy flow, load balancing, and operational coordination.

On the DC side, the system features photovoltaic (PV) panels connected via an MPPT controller, ensuring optimal solar energy harvesting. The DC bus links the PV array to a Battery Energy Storage System (BESS), which stores excess energy and provides backup during peak demand or grid outages. A bidirectional converter bridges the AC and DC domains, enabling flexible power exchange and enhancing system adaptability. This integrated micro-grid architecture exemplifies the synergy between renewable sources and smart control mechanisms, supporting decentralized energy management and promoting sustainability in both isolated and grid-connected contexts.

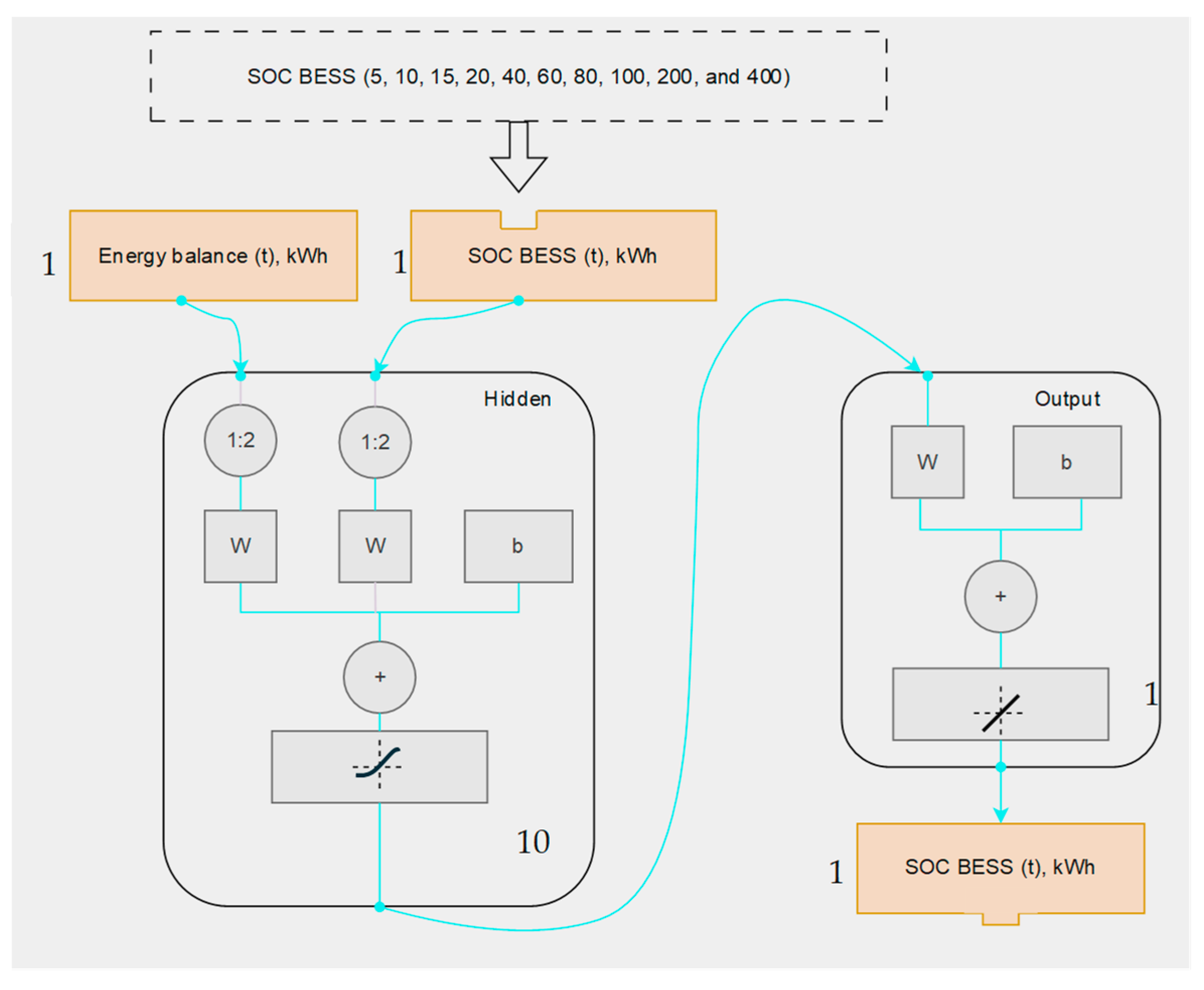

On the other hand, the purpose of this methodology also estimates the variation in battery capacities over time based on the energy balance of the hybrid system. Accordingly, different battery capacities were evaluated, with nominal values of 5, 10, 15, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 200, and 400 kWh. The machine learning algorithm employed in this study is a Nonlinear Autoregressive Neural Network with Exogenous Inputs (NARX Network). This architecture is well-suited for modeling and predicting time-series data, as it learns to forecast the State of Charge (SOC) of the Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) using both past SOC values and previous energy balance values, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

The integrated model supports the design of sustainable, flexible, and economically viable energy systems that enhance renewable energy utilization and grid stability.

Inputs (NARX Network). This architecture is well-suited for modeling and predicting time-series data, as it learns to forecast the State of Charge (SOC) of the Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) using both past SOC values and previous energy balance values, as illustrated in

Figure 2, where W and b represent the weight and bias parameters of the activation function, respectively. The weight (w) determines the influence on the neuron’s activation, while the bias (b) term allows the activation function to shift its response. The analysis comprises ten hidden layers and a single output layer.

Compressed air vessels are a versatile method for energy storage, utilizing the principles of compressible fluids like air and incompressible fluids like water or oil. The compressed gas, compressed by a pump or power source, stores potential energy in the form of pressure difference between the gas and the external environment. The energy can also be released through expansion, pushing the liquid out of the vessel, which can drive a hydraulic motor, generate electricity, or perform mechanical work. Compressed Air Vessels can be used in water networks for smoothing pulsations, providing emergency power, or compensating for leakage. They can also be used as renewable energy storage, storing excess energy when production exceeds demand and releasing it when needed. These solutions are robust, cost-effective, and offer high round-trip efficiency, making them suitable for various energy storage needs.

Hence, by using a CAV for energy storage, industries can improve energy efficiency, manage energy loads more effectively, and reduce dependence on external power sources [

46,

47,

48].

CAV is filled by part of water and air. The air can operate as a compressed air energy storage giving potential energy for the system. The mathematical formulation can be expressed as follows:

The steady or unsteady states can be simulated using the characteristic lines based on the MOC and are expressed as follows:

where

,

Cn is the negative characteristic constant and

Cp the positive one,

Hp the head and

Qp the flow at the calculation pipe section.

If

and

values are known in points

A (left) and

B (right) of a grid points in a pipe system, then

where

f is the friction factor (-), g, the gravitational acceleration (m/s

2),

HA is the piezometric head on section previous section (m),

HB is the piezometric head on forward section (m) and

HP is the piezometric head at section P of calculus (m).

Equations (3) and (4) are basic algebraic relationships that can be used to describe the transient propagation of hydraulic grade lines and water flow rates. Solving simultaneously Equations (3)–(5), the flow can be calculated along the pipe system:

where

is the absolute pressure head at the end of an analyzed time step,

is the air volume at the end of an analyzed time step,

is the air volume,

is the flow through the orifice,

is the cross-section of the orifice,

is the discharge coefficient of the orifice,

is the polytropic coefficient (usually takes a value of 1.2),

is the initial elevation of the free surface,

is the barometric pressure,

is the constant computed in the initial condition of the air vessel,

is the free surface elevation at the end of the time step, and

is the cross-section of the air vessel. The equation of an air vessel is obtained considering the polytropic law

.

Figure 2 represents the ML algorithm in the estimation of SOC of different batteries capacity. The NARX network is a recurrent dynamic neural network specifically designed for time-series modeling and forecasting. It follows the general formulation:

where

represents the SOC of the BESS at time

, regressed on its previous values

, and on the prior values of an independent (exogenous) input signal

, which corresponds to the energy balance.

In this study, the NARX model was configured with ten layers for SOC–BESS prediction. The time-series dataset was partitioned into three subsets: 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. These percentages were selected to reduce the risk of overfitting and to achieve a robust and accurate predictive model.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Hybrid Renewable Energy Solutions

Hybrid renewable energy systems are increasingly vital for the development and resilience of micro-grids, offering a strategic solution to the challenges posed by intermittent power generation and variable demand. By combining multiple renewable sources—such as solar, wind, and small-scale hydropower—with energy storage technologies and intelligent control systems, hybrid configurations enhance the reliability, flexibility, and sustainability of decentralized energy networks. Micro-grids, which can operate autonomously or in coordination with the main grid, benefit significantly from this hybrid approach, as it allows for a continuous power supply even when one energy source is unavailable due to weather conditions or resource variability.

The integration of diverse energy sources within a hybrid system mitigates the limitations of single-source renewables. For instance, solar energy is abundant during daylight hours but absent at night, while wind power may fluctuate unpredictably. By combining these with complementary sources and storage solutions—such as batteries, compressed air vessels, or pumped-hydro storage—micro-grids can maintain a stable energy output and reduce reliance on fossil-fuel-based backup systems. This not only improves energy security but also supports decarbonization goals and enhances the economic viability of renewable investments. Moreover, hybrid renewable systems enable load balancing, peak shaving, and demand-side management within micro-grids, optimizing energy use and minimizing waste. They also facilitate energy access in remote or underserved regions, where grid extension is impractical or cost-prohibitive. In such contexts, hybrid micro-grids empower communities with reliable, clean electricity for essential services, economic development, and climate resilience. As global energy systems transition toward decentralization and sustainability, hybrid renewable energy solutions are becoming indispensable for future-ready micro-grids. Their ability to harmonize generation, storage, and consumption across diverse conditions makes them a cornerstone of resilient, low-carbon infrastructure.

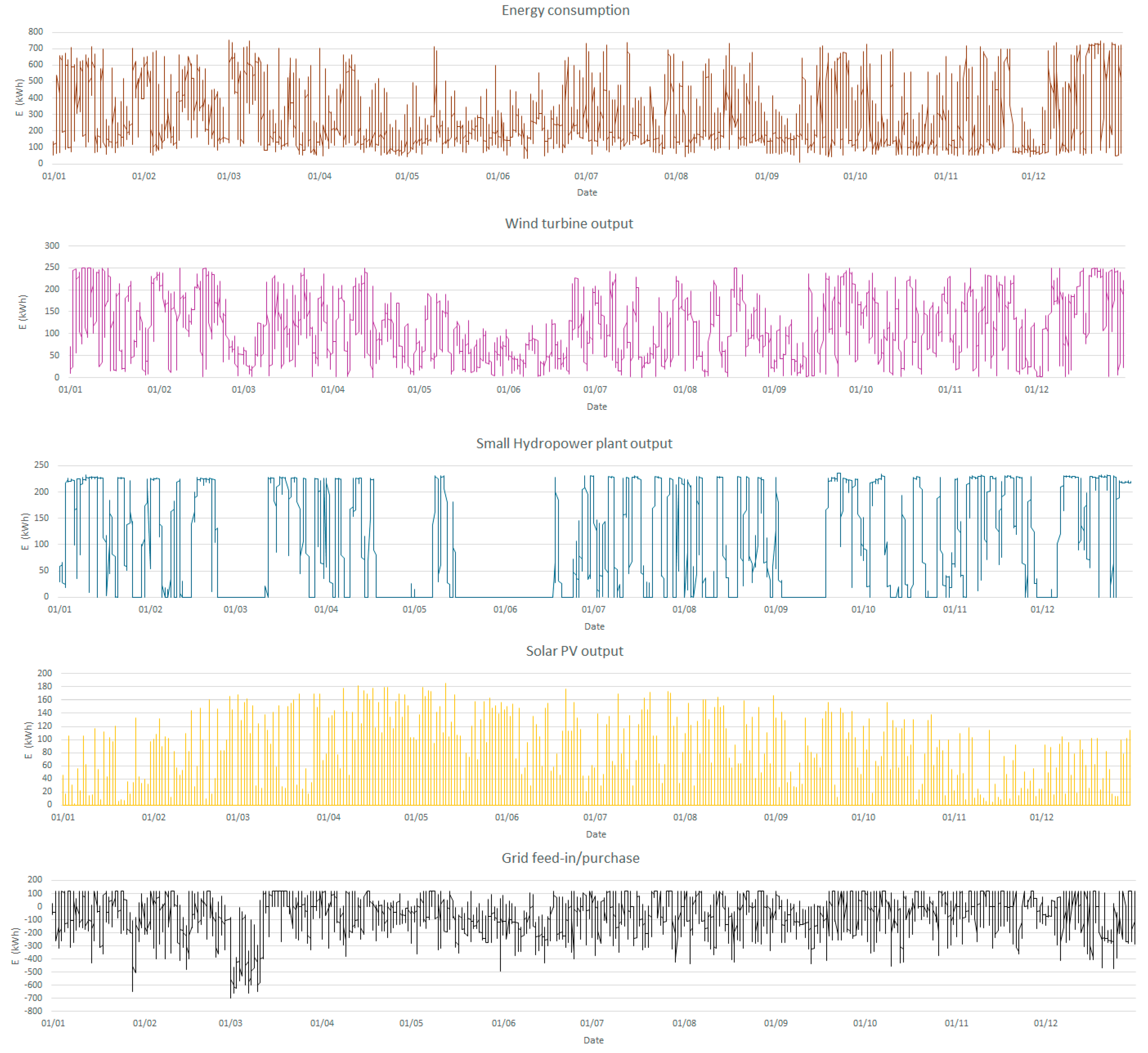

Figure 3 presents a series of five time-series plots that collectively illustrate the dynamics of energy consumption, renewable energy generation, and grid interaction within a micro-grid system over the course of an average year. The top plot shows daily energy consumption (kWh), characterized by frequent fluctuations and distinct peaks, reflecting variable demand patterns across each month. The second plot displays the wind turbine output, which varies significantly over time, indicating the intermittent nature of wind energy availability. The third plot represents the small hydropower plant output, which remains relatively stable, suggesting consistent and predictable generation from this source. The fourth plot captures the solar photovoltaic (PV) output, exhibiting a clear diurnal cycle with pronounced peaks during daylight hours and zero output at night, consistent with solar irradiance patterns. Finally, the bottom plot illustrates grid feed-in and purchase, with values oscillating between positive and negative, signifying alternating periods of importing energy from the grid to compensate for the missing and exporting when there is excess or production. Together, these plots provide a comprehensive overview of the temporal behavior of energy flows within the micro-grid, highlighting the VFR complementary roles of wind, hydro, and solar sources in meeting consumption needs and managing grid interactions.

3.2. Batteries

3.2.1. Battery Capacity Behavior

Batteries play a critical role in micro-grid energy storage systems, enabling decentralized, resilient, and flexible power solutions that support the integration of renewable energy sources. As micro-grids are designed to operate either independently or in conjunction with the main grid, battery energy storage systems (BESS) provide the necessary buffer to balance supply and demand, ensure power quality, and maintain grid stability during fluctuations or outages. In a typical micro-grid set-up, batteries store excess electricity generated from solar panels, wind turbines, or other distributed energy resources (DERs). This stored energy can then be dispatched during periods of low generation or peak demand, allowing the micro-grid to maintain continuous operation without relying on fossil-fuel-based backup systems. Lithium-ion batteries are the most commonly deployed technology due to their high energy density, fast response time, and declining costs. However, other chemistries such as flow batteries, sodium-ion, and solid-state batteries are gaining traction for specific applications requiring longer duration or enhanced safety.

Battery systems in micro-grids serve multiple functions such as:

Load shifting: Storing energy during off-peak hours and releasing it during peak demand to reduce grid stress.

Frequency regulation: Providing rapid response to stabilize voltage and frequency deviations.

Black start capability: Enabling micro-grids to restart independently after a grid outage.

Renewable smoothing: Mitigating the variability of solar and wind generation by absorbing short-term fluctuations.

Beyond technical benefits, batteries enhance the economic viability of micro-grids by reducing energy costs, minimizing curtailment of renewables, and enabling participation in demand response programs. In remote or underserved regions, battery-backed micro-grids offer a pathway to energy access and independence, reducing reliance on diesel generators and improving environmental outcomes. As the global energy landscape shifts toward decarbonization and decentralization, batteries are increasingly recognized as a cornerstone of micro-grid architecture. Their ability to support clean, reliable, and adaptive energy systems makes them indispensable for future-ready infrastructure in both urban and rural contexts.

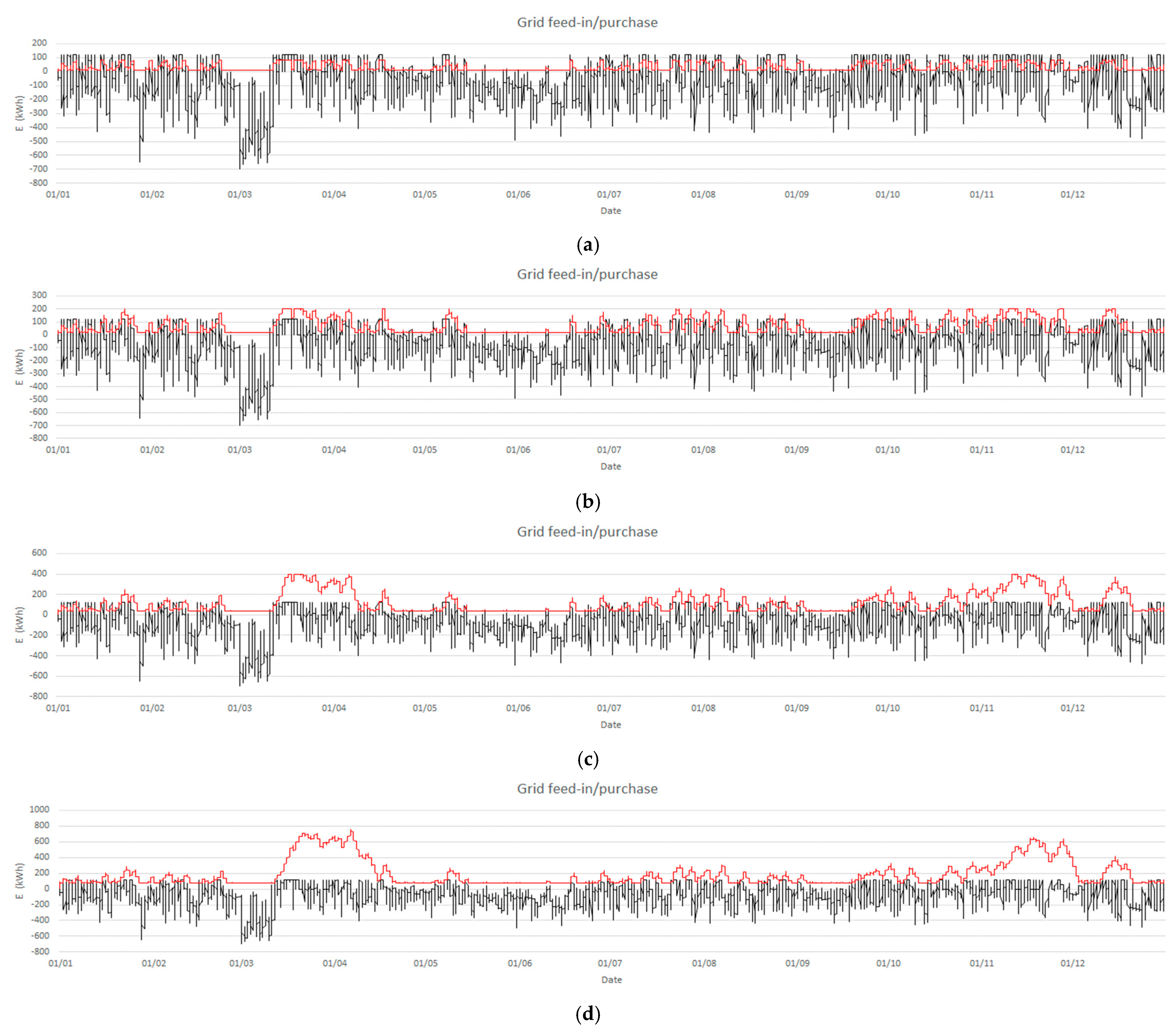

Figure 4 comprises four time-series plots labeled (a) through (d), each depicting the variation in grid feed-in and purchase over time within a micro-grid system for different battery capacity. Each plot includes two curves: a black line showing the grid interaction and a red line representing the battery contribution that in certain cases can avoid grid import. Graph (a) shows relatively stable grid/battery exchange with minor fluctuations, while graph (d) exhibits the behavior of a higher battery capacity with the highest grid exchange values among the four scenarios.

These variations correspond to different operational configurations or energy demand profiles. Importantly, the presence of a Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) within the micro-grid allows for strategic energy management: in certain cases, the batteries can replace energy from the grid during surplus renewables periods and store it for later use, thereby reducing reliance on grid supply during peak demand or high-tariff intervals. This capability enhances system flexibility, supports load leveling, and contributes to economic and energy efficiency across the micro-grid’s operational timeline. The excess of BESS energy can also be redirected to other neighboring building consumptions.

3.2.2. Machine Learning on BESS Performance Estimation

This section presents results demonstrating the suitability of the NARX Network for representing the State of Charge (SOC) of the Battery Energy Storage System (BESS), based solely on the energy balance time series under the analyzed system conditions. This finding is particularly relevant, as it highlights the potential of the NARX Network as a reliable tool for decision-makers to forecast the SOC of the BESS over time.

Figure 5 illustrates the predicted and target SOC–BESS values for battery capacities of 80, 200, and 400 kWh, showing an excellent agreement between the simulated and observed time-series data. Overall, the calculations conducted using MATHLAB R2024b, the NARX Network accurately reproduced the SOC–BESS time series across the training, validation, and testing phases, confirming its ability to model the system’s dynamic behavior effectively.

To evaluate the performance of all simulations, the Mean Square Error (MSE) and the coefficient of determination (

) were computed for all SOC–BESS values ranging from 5 to 400, as presented in

Table 1. The equations used for these statistical metrics are as follows:

where the subscripts

and

denote the true and predicted values, respectively;

is the total number of observations (8760 points); and

represents the mean value of

.

Based on the results presented in

Table 1, the proposed model demonstrates excellent predictive capability for estimating the SOC of the BESS across all tested capacities. For every case, the coefficient of determination (

) remains above 0.9845 during the training, validation, and testing phases, confirming the strong correlation between predicted and observed values. Furthermore, the Mean Square Error (MSE) values indicate very low deviations, ranging from 0.1297 to 0.4919 kWh

2 across all simulations. This consistent performance highlights the robustness of the NARX Network in accurately reproducing the SOC–BESS time series under varying capacity conditions.

Table 2 shows the number of epochs required for the NARX model to converge, corresponding to the training iterations used to minimize the error between the true and predicted SOC–BESS values. The number of epochs ranges from 64 to 302. In general, lower battery capacities required fewer epochs to converge, whereas higher capacities required more iterations.

This trend indicates that as the system complexity and storage capacity increase, the model requires additional training cycles to accurately capture the nonlinear relationships between the energy balance and the SOC of the BESS.

3.3. Compressed Air Vessel

Compressed air vessels are gaining recognition as a robust and sustainable solution for long-duration energy storage, particularly in systems integrating intermittent renewable sources such as wind and solar. These vessels operate by storing energy in the form of pressurized air, which can later be released to drive turbines and generate electricity during periods of high demand or low renewable output. Unlike conventional batteries, compressed air vessels offer a non-polluting alternative with significantly longer lifespans and minimal degradation over time, making them ideal for scalable and modular deployment across diverse geographic and infrastructural contexts.

In hybrid energy systems, compressed air vessels can be coupled with water reservoirs to form water-air batteries, enabling dual-mode operation. During surplus energy periods, renewable electricity powers pumps that inject water into the vessel, compressing the air inside. This stored energy can then be released to produce hydropower when demand exceeds supply. Such configurations enhance system flexibility, allowing energy to be stored when production exceeds consumption and dispatched when renewable generation is insufficient.

The strategic importance of compressed air vessels lies in their ability to support grid stability, reduce curtailment of renewable energy, and contribute to the water-energy nexus by facilitating controlled water allocation. Their integration into pumped-hydro storage systems further amplifies their utility, offering a clean, efficient, and technically mature solution for balancing supply and demand. As global energy systems transition toward net-zero targets, compressed air vessels stand out as a key enabler of resilient, low-carbon infrastructure, capable of supporting both energy and resource management in a unified framework.

Figure 6 presents a composite visual overview of experimental infrastructure and operational data related to CAV energy storage research conducted at the Hydraulic Laboratory of Instituto Superior Técnico (IST).

Figure 6a shows the Hydraulic Lab at IST, likely depicting the physical set-up used for testing. This may include pipelines, pumps, valves, sensors, and control systems arranged to simulate real-world conditions.

Figure 6b illustrates the system operation and measurement framework, detailing how various parameters—such as flow rate, pressure, and pumps (single or in series)—are monitored during dynamic processes. It includes schematic representations or time-series plots showing how the system responds under different operating conditions.

Figure 6c focuses on CAV fullness during a pumped-storage operation, capturing the temporal evolution of volume and pressure head. This figure shows how CAV behavior correlates with operational parameters, informing both predictive modeling and control strategies.

Together, the figure underscores the integration of experimental infrastructure, real-time monitoring, and CAV behavior analysis in advancing the understanding and optimization of pumped-storage hydropower systems.

The potential energy obtained for main trial, and the resultant energy stored in the compressed air vessels (CAV) are presented in

Table 3, where E

pw is the water potential energy, in kWh and E

pa is the compressed air potential energy, in kWh, with i and f are the initial and final duration registered time. The final column presents the storage efficiency of each trial, dividing the stored energy by the energy consumed by the pump.

In case of CAV energy induced by a water hammer condition of a successively valve closure results in the following variation (

Figure 7).

The results in

Table 4 present a scalable of the measurements developed in an experimental set-up at IST Hydraulic Lab model (

Figure 7). This study inspected the Compressed air vessel idea from the amount of attainable hydraulic power and energy produced, similar to a water-battery. The presented data for a prototype at a scale 1/30 relative to the lab set-up demonstrates encouraging values of hydraulic power, having the maximum values of 6142 kW, while the maximum power of the model was equal to 41 W when a succession of water hammer valve closures allowed a pressure wave as an energy storage solution.

3.4. Innovative Components

This research is structured to highlight specific innovations in hybrid energy systems replying to the following questions: (i) In what innovative ways does the mathematical modeling of fluid flow within compressed air vessels advance beyond traditional hydropower and pumping system analyses? The study innovates by using hydraulic modeling of CAV behavior and integrating machine learning (NARX model) to predict battery SOC with high accuracy (R2 > 0.98, MSE as low as 0.13 kWh2). This combination supports intelligent, adaptive energy systems beyond traditional fluid flow models. (ii) How does the laboratory evaluation of compressed air vessels introduce novel insights into efficiency and storage capacity compared to conventional energy storage technologies? Laboratory tests at IST revealed storage efficiencies between 33.9% and 57.1%, with optimal performance at 0.5–2 bar and high pump head scenarios. Unlike electrochemical batteries, CAVs showed minimal degradation, modular scalability, and lifespans exceeding 50 years, offering a robust long-duration alternative. (iii) What innovative contributions do solver-based simulations provide in designing hybrid energy systems that integrate compressed air vessels with renewable inputs? Simulations demonstrated that larger battery capacities (400–800 kWh) reduce grid purchases, store surplus renewable energy, and redistribute excess to neighboring loads. Hybrid configurations combining BESS and CAVs enhance system efficiency, flexibility, stability, and economic viability, showing innovative integration of diverse storage strategies. (iv) How does the analysis of operational behavior and adaptability reveal innovative pathways for enhancing resilience and flexibility in hybrid energy systems? Answer: The study concludes that hybrid micro-grids benefit from combining BESS (rapid response, fine control) with CAVs (durable, scalable, long-duration storage). This dual approach provides resilience, stability, and adaptability, with innovations like predictable waterhammer-based storage behavior (Re ≤ 75,000, VFR ≥ 11%) and incremental pressure gains from repeated events, confirming CAVs as strategic assets for sustainable energy management.

4. Conclusions

This research presents a comprehensive methodology with evaluation of energy storage systems—specifically Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) and Compressed Air Vessels (CAV)—within hybrid renewable micro-grid configurations. The main goal is to enhance energy resilience, flexibility, and sustainability by integrating diverse storage technologies capable of mitigating the intermittency of solar, wind, and small-scale hydropower sources. BESS units were assessed across a wide range of capacities, from 5 kWh to 400 kWh, using a Nonlinear Autoregressive Neural Network with Exogenous Inputs (NARX). This machine learning model accurately predicted the State of Charge (SOC) based on historical energy balance data, achieving high performance metrics with R2 values exceeding 0.98 and Mean Square Errors (MSE) as low as 0.13 kWh2. Larger battery capacities, such as 400 kWh and 800 kWh, demonstrated superior ability to reduce grid purchases, store surplus renewable energy, and redistribute excess to neighboring loads, thereby improving overall system efficiency and economic viability. But, in general, the behavior was very interesting to fit the missing energy in certain periods with the advantage in system flexibility, stability and reliability.

In parallel, the study explored the role of CAVs in two distinct operational modes: pumped-storage and waterhammer-induced energy storage. In the pumped-storage configuration, CAVs function as water-air batteries, where renewable electricity drives pumps to compress air via water displacement. Laboratory tests at IST revealed storage efficiencies ranging from 33.9% to 57.1%, depending on operating pressure and head conditions, with optimal performance observed between 0.5 and 2 bar and high pump head scenarios. These systems offer long-duration storage with minimal degradation, modular scalability, and lifespans exceeding 50 years, making them a robust alternative to electrochemical batteries.

The waterhammer-based CAV approach leverages transient hydraulic surges to store energy in compressed air. Experimental results showed that for Reynolds numbers below 75,000 and Volume Fraction Ratio (VFR) above 11%, the stored pressure consistently exceeded peak transient pressure, indicating reliable and predictable energy capture. A scaled prototype achieved hydraulic power outputs up to 6142 kW and energy storage of 170 kWh at 50% air volume, demonstrating the feasibility of integrating hydraulic transients into energy storage strategies.

Overall, the study concludes that hybrid micro-grids benefit significantly from combining or using alternatives as BESS and CAV technologies. While batteries offer rapid response and fine-variations control, CAVs provide durable, low-maintenance, and scalable solutions for long-duration storage. The integration of machine learning for SOC prediction and hydraulic modeling for CAV behavior supports the development of intelligent, adaptive energy systems capable of meeting future sustainability and grid stability goals.

Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) enhance micro-grid reliability by storing surplus renewable energy and discharging it during low-generation periods, ensuring stable power flow. They support grid stability through rapid voltage and frequency regulation, and enable peak shaving and load shifting to reduce operational costs. BESS also improve renewable integration, reduces fossil fuel dependency, and provides autonomous backup in islanded scenarios. In parallel, compressed air vessels (CAVs) offer long-duration, non-degrading energy storage, modeled through hydraulic simulations and validated in lab tests. These systems are modular and adaptable, suitable for integrating intermittent renewables and managing water-energy nexus challenges. Waterhammer-based CAV storage shows predictable pressure behavior when Reynolds number is ≤ 75,000 and Volume Fraction Ratio (VFR) exceeds 11%. Higher VFR mitigates pressure peaks, making it also vital for hydraulic transient control. Repeated waterhammer events incrementally increase stored pressure under optimal conditions, confirming CAVs as strategic assets for sustainable energy and resource management.