Abstract

Antimony (Sb), a toxic metalloid, inhibits plant growth and threatens human health. Yellow Stripe-Like (YSL) proteins play crucial roles in metal ion transport and cellular homeostasis. While the OPT gene family has been characterized in some species, its genome-wide organization and functional involvement in Sb stress response remain unexplored in Brassica juncea. Here, we identified 47 high-confidence BjOPT genes and combined transcriptomic approaches to elucidate their regulatory roles under Sb stress. Phylogenetic tree, conserved motifs, and gene structure analyses consistently distinguished the BjOPT and BjYSL subfamilies. Comparative and collinearity analyses indicated that OPT genes in Brassica species (including B. rapa, B. nigra, and B. juncea) expanded independently of whole-genome triplication events. Transcriptomic profiling revealed significant enrichment of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) related to key biological processes (oxidative and toxic stress response, metal ion transport, and auxin efflux) and pathways (glutathione metabolism, MAPK signaling, and phytohormone transduction), highlighting their roles in Sb detoxification and tolerance. Notably, three BjYSL3 (BjA10.YSL3, BjB02.YSL3, and BjB05.YSL3) genes exhibited strong up-regulation under Sb stress. Heterologous expression in yeast demonstrated that both BjA10.YSL3 and BjB02.YSL3 enhance Sb tolerance, suggesting their potential role in transporting Sb–nicotianamine (NA) or phytosiderophore (PS) complexes. These findings advance our understanding of Sb tolerance mechanisms and provide a basis for developing metal-resistant crops and phytoremediation strategies.

1. Introduction

China currently dominates global antimony (Sb) reserves and production, with an output of approximately 60,000 metric tons in 2024—3.53 times that of Tajikistan, the second-largest producer [1]. Severe Sb contamination has been reported in soils surrounding major mining areas in Guangxi, Hunan, Yunnan, and Guizhou provinces [2]. Sb, a potentially toxic metalloid, is listed as a priority pollutant by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the European Union [3]. However, owing to its advantageous properties, Sb is extensively used in industrial and military applications, including flame retardants, batteries, alloys, glass ceramics, and catalysts [4,5]. These Sb-containing products release the metalloid into ecosystems through various pathways, disrupting ecological balance and bioaccumulating through food chains, ultimately posing risks to human health [6,7,8].

During metal uptake and translocation, plants rely on various transporter proteins localized to the plasma membrane and organellar membranes, such as vacuoles, mitochondria, and plastids [9,10]. Key transporters include the oligopeptide transporter (OPT) family, metal tolerance proteins (MTPs), ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABCs), heavy metal ATPases (HMAs), and natural resistance-associated macrophage proteins (NRAMPs) [9]. These proteins mediate the translocation of metal ions between the cytoplasm and organelles, facilitating sequestration and detoxification [10].

The OPT family, comprising the peptide transporter (PT) and YSL subfamilies, functions as proton-coupled symporters [11,12,13]. OPT genes were first identified in Candida albicans [14] and subsequently cloned in bacteria and plants. They have been demonstrated to participate in iron transport in both plants and fungi, as well as in the translocation of small peptides, glutathione, and metal chelates [15]. In Arabidopsis, AtOPT3 functions as a phloem-specific transporter essential for iron allocation [16]. Similarly, in rice, OsOPT1, OsOPT4 and OsOPT7 have been confirmed to transport iron chelates [17]. The YSL subfamily primarily facilitates the long-distance transport of metals, such as manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), cadmium (Cd), and nickel (Ni), chelated with nicotianamine (NA) or phytosiderophores (PSs) [15,18,19]. Research has demonstrated that in Arabidopsis, AtYSL1, AtYSL2, and AtYSL3, localized in leaf parenchyma cells, mediate Fe-PS translocation to stems [20,21]. In Brassica juncea (B. juncea), the plasma membrane-localized metal–NA transporter BjYSL7 facilitates Fe(II)-NA transport and contributes to Cd and Ni root-to-shoot translocation [22]. Notably, recent studies show that CRISPR-edited OsYSL15 mutants in rice exhibit a 40.7–70.6% reduction in chromium (Cr) uptake, identifying OsYSL15 as a key gene for Cr accumulation [18].

B. juncea (2n = 36, AABB), an economically important allopolyploid vegetable crop derived from the hybridization between B. rapa (n = 10, AA) and B. nigra (n = 8, BB), is classified into four major types based on morphological traits and agricultural use: seed mustard, leaf mustard, stem mustard, and root mustard [23]. Furthermore, it exhibits rapid growth, high biomass yield, and notable capacity for heavy metal accumulation and translocation, making it an ideal candidate for phytoremediation [24]. Advances in plant genomics have enabled comprehensive characterization of the OPT gene family in species including A. thaliana, rice, potato [9], tomato and maize [25]. In B. juncea, 27 BjYSL genes homologous to AtYSL2/5/6/8 were previously identified using ARDRA-based molecular fingerprinting with degenerate primer-mediated RT-PCR [26]. Despite these advances, a systematic annotation of BjOPT genes remains incomplete. This study employs HMMER-based profiling to identify high-confidence OPT proteins integrated with transcriptomic analyses to reveal key OPT genes involved in Sb stress response. Our study aims to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms governing Sb tolerance and accumulation, thereby providing insights into plant adaptation to heavy metal stress and informing strategic development of phytoremediation approaches.

2. Results

2.1. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of OPTs

A genome-wide identification of OPT proteins was conducted across three Brassica species using the oligopeptide transporter domain (PF03169) as a query to screen the PFAM, SMART, and NCBI-CDD databases. A total of 98 OPT genes were identified: 47 in B. juncea, 24 in B. rapa, and 27 in B. nigra (Tables S1 and S2). Notably, the number of OPT genes in the allotetraploid B. juncea was slightly lower than the combined total of its diploid progenitors (B. rapa and B. nigra). All identified genes were systematically named according to chromosomal location, species abbreviation, and subfamily (e.g., BjA02.OPT1 and BjB02.YSL1 for B. juncea).

Physicochemical analysis indicated that most BjOPT proteins range from 632 to 1243 amino acids (70.83–139.25 kDa), with exceptions including the unusually long BjA04.YSL4 (3545 aa), possibly due to domain expansion, and the shorter BjA03.OPT8b (431 aa) and BjB08.OPT1 (332 aa). Theoretical isoelectric points (pI) varied from 5.65 to 9.65, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) values ranged between 0.04 and 0.65, consistent with their classification as hydrophobic transmembrane transporters. Subcellular localization predictions indicated that BjA04.YSL4 localizes to mitochondria and the nucleus, BjYSL3 (BjA10.YSL3/BjB02.YSL3/BjB05.YSL3) to the endoplasmic reticulum, and the majority of BjOPT proteins to the plasma membrane. Transmembrane helix analysis revealed 11–16 helices in most proteins, except for BjA03.OPT8b (8 helices) and BjB08.OPT1 (7 helices), corresponding to their reduced lengths. Complete physicochemical properties are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis and Chromosomal Localization of BjOPTs

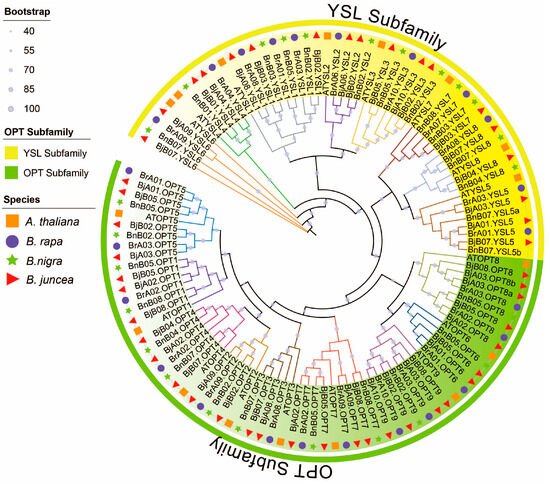

To elucidate phylogenetic relationships among OPT proteins in Brassica species, we conducted a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of 115 OPT sequences from A. thaliana, B. rapa, B. nigra, and B. juncea (Figure 1). The neighbor-joining tree revealed two well-supported clades corresponding to the OPT and YSL subfamilies, with most nodes showing strong bootstrap support (≥90%). Among the 17 color-coded clades (based on AtOPT/AtYSL orthologs), most B. juncea (AABB) OPT gene copies corresponded to orthologs from B. rapa (AA) and B. nigra (BB). Furthermore, most branches contained one OPT ortholog in the diploid progenitor species and two or more in the allotetraploid, consistent with chromosomal additivity, as exemplified by BrA09.YSL6 + BnB07.YSL6 = BjA09.YSL6 & BjB07.YSL6. Notably, BjB05.OPT6 had no detectable ortholog in the progenitors, while BjB07.YSL5 corresponded to two copies in B. nigra (BnB07.YSL5a/b). These results indicate that the OPT gene family was largely conserved during allopolyploidization, although certain members experienced expansion or contraction.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationships of OPT family proteins across Brassicaceae species. The neighbor-joining tree illustrates the evolutionary relationships among 115 OPT proteins from A. thaliana (orange squares), B. rapa (purple circles), B. nigra (green stars), and B. juncea (red triangles). The phylogenetic topology reveals 17 distinct clades (color-coded) representing evolutionarily conserved subgroups within the OPT family.

Chromosomal localization analysis indicated that the 47 BjOPT genes are unevenly distributed across 14 chromosomes of B. juncea, with 21 and 26 genes located in the A and B subgenomes, respectively. Chromosomes B02 and B05 showed the highest gene density (6 genes each), whereas A04, A06, and B01 contained only one BjOPT gene each. No BjOPT genes were detected on chromosomes A05, A07, or B06 (Figure S1).

2.3. Structural Analysis of BjOPT Proteins

The functional diversity of gene families is primarily determined by variations in gene structure and conserved domain composition [27]. Analysis of 10 conserved motifs in BjOPT proteins revealed distinct subfamily-specific patterns (Figure S2a,b). BjOPT members contained 5–10 motifs, with BjB08.OPT1 exhibiting the minimal set (motifs 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9), suggesting these constitute core functional elements. In contrast, BjYSL proteins contained only 3–4 motifs (primarily motifs 1, 2, and 8), indicating potential functional divergence between the OPT and YSL subfamilies. Domain analysis confirmed that all BjOPT proteins retain the conserved OPT domain, supporting their conserved role in substrate transport. Notably, BjA04.YSL4, the longest and most structurally complex protein, uniquely contained PKc_like and FAT domains, consistent with domain expansion (Figure S2c), though the functional significance of these domains remains unclear. Gene structure analysis indicated considerable variability in CDS/UTR organization among BjOPT and BjYSL genes. For example, BjA04.YSL4 contained 28 CDS regions, whereas BjB08.OPT1 had only one (Figure S2d), demonstrating substantial structural variation. Despite these differences, all members retained core functional domains, highlighting evolutionary conservation of transport function amid structural diversification.

2.4. Synteny and Divergence Time Analysis of OPT Genes

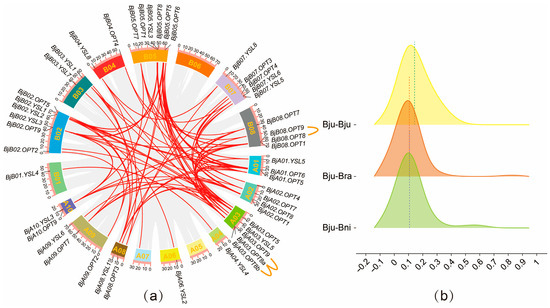

Gene duplication events serve as a major driver of family evolution [28]. The present study indicates that the BjOPT gene family in B. juncea has undergone both expansion and contraction throughout its evolutionary history. To investigate selective pressures on paralog OPT gene pairs within the B. juncea genome and between B. juncea and its diploid progenitors, synteny analysis was conducted among B. juncea & B. juncea, B. juncea & B. rapa, and B. juncea & B. nigra, identifying 192 orthologous gene pairs. The Ka/Ks ratios were calculated for three comparison sets (51 pairs in B. juncea & B. juncea, 63 in B. juncea & B. rapa, and 78 in B. juncea & B. nigra), all of which exhibited Ka/Ks < 1 (Figure 2b; Tables S3 and S4), indicating pervasive purifying selection (Figure 2b). Further analysis revealed that among the 47 BjOPT genes, there were 3 tandem duplications, 16 segmental duplications, and 32 whole-genome duplication events (Table S3). Among these, the BjOPT8 gene exhibited the highest number of homologous gene pairs (13 pairs), whereas only one homologous pair was identified for the BjOPT gene. The divergence time (T = Ks/2λ) was estimated for 51 duplicated gene pairs in B. juncea, ranging from approximately 74.0 to 4.5 million years ago (MYA), with a mean of 25.1 MYA. Three gene pairs—BjA10.OPT9/BjB02.OPT9, BjA09.OPT7/BjB08.OPT7, and BjA04.YSL4/BjB01.YSL4—exhibited the most recent duplication events.

Figure 2.

OPT gene collinearity and Ka/Ks raincloud plot analysis. (a) Intra-genomic collinearity analysis of BjOPT genes in B. juncea. Red lines indicate duplicated BjOPT gene pairs; orange lines represent tandemly duplicated pairs. (b) Raincloud plot of Ka/Ks ratios for orthologous OPT gene pairs between B. juncea and its diploid progenitor species.

Collectively, these results suggest that OPTs are highly conserved within Brassica species without significant functional divergence. Both intra- and interspecies duplicated OPT gene pairs may perform similar functions, particularly in mediating the transport of small peptides, glutathione, and metal chelates, providing critical insights for future functional predictions of OPT genes.

2.5. Analysis of BjOPT Promoter Elements, Expression Patterns, and GO Enrichment

Using PlantCARE software (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/, accessed on 20 September 2025), cis-regulatory elements (CREs) in BjOPT promoters were predicted and categorized into four categories based on previous studies: phytohormone response, stress response, light response, and growth/development elements [29]. Overall, phytohormone-responsive elements such as ABA-responsive ABRE and MeJA-related CGTCA motif and TGACG motif, along with the anaerobic induction element ARE and light-responsive Box 4, were frequently identified among the BjOPT promoters (Figure S3), suggesting their potential roles in stress adaptation. Furthermore, no distinct distribution pattern of these elements was observed between the BjOPT and BjYSL subfamilies, indicating functional divergence in the regulatory domains among different BjOPT promoters.

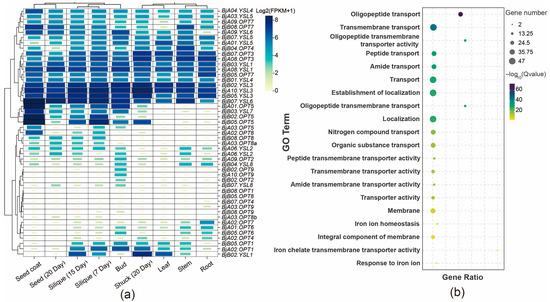

To elucidate the tissue-specific expression profiles of BjOPT genes, RNA-seq data from various tissues of B. juncea cv. Sichuan Yellow were analyzed, including roots, stems, leaves, buds, siliques at 7 and 15 DAF, pods at 20 DAF, seeds, and seed coats. Results showed that BjOPT3/7 and BjYSL3/4/6 are broadly expressed across all tissues, with homologous genes such as BjYSL3 (BjA10.YSL3, BjB02.YSL3, and BjB05.YSL3) exhibiting nearly identical expression patterns. In contrast, BjOPT5 (BjA01.OPT5, BjB02.OPT5, and BjB05.OPT5) displayed marked tissue-specific expression, particularly in seed coats and siliques (Figure 3a). GO enrichment analysis indicated that the 47 BjOPT and BjYSL members are primarily associated with biological processes, including oligopeptide transport (GO:0006857), transmembrane transport (GO:0055085), and iron ion homeostasis (GO:0055072) (Figure 3b), supporting their involvement in transmembrane transport of oligopeptides and metal ions.

Figure 3.

Gene expression pattern and GO enrichment analysis. (a) Analysis of expression pattern of BjOPTs. (b) GO enrichment analysis of BjOPTs.

2.6. Transcriptome Profiling Under Sb Stress

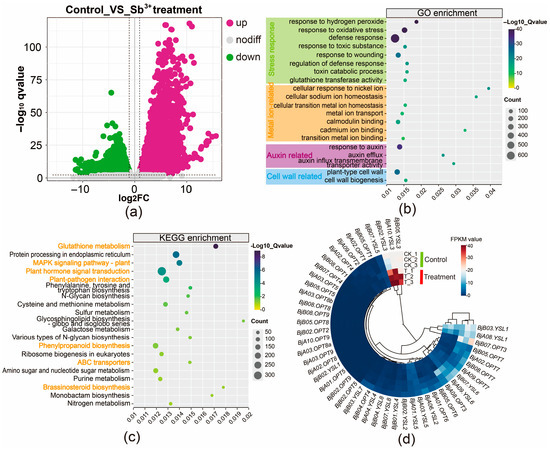

To investigate the transcriptional response of B. juncea to Sb(III) stress, four-week-old plants were hydroponically exposed to 75 mg/L Sb(III). Following 24 h of treatment, plants exhibited observable wilting of basal leaves and root browning. Evans Blue staining revealed that Sb exposure caused a distinct color change in roots from white to dark blue, indicating severe disruption of plasma membrane integrity. Based on these phenotypic changes, RNA sequencing was performed on root tissues from three biological replicates each of control (CK_1, CK_2, CK_3) and Sb-treated (T_1, T_2, T_3) plants. A total of 140.06 million reads and 42.02 Gb of clean bases were obtained, with averages of 23.34 million reads and 7.00 Gb per sample. The Q20 and Q30 values for all samples exceeded 97.66% and 93.21%, respectively (Table S5), indicating high sequencing quality. Compared to the control group, 20,454 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in the treated group, comprising 9871 up-regulated and 10,583 down-regulated genes, with up-regulated genes showing a more pronounced response to Sb stress (Figure 4a). GO enrichment analysis revealed that the DEGs were predominantly associated with stress responses (e.g., response to oxidative stress, defense response, glutathione transferase activity), metal ion binding (e.g., cellular response to nickel ion, metal ion transport, cadmium ion binding), auxin response (e.g., response to auxin, auxin efflux), and cell wall-related processes (Figure 4b; Table S6). KEGG pathway analysis indicated significant enrichment of DEGs involved in glutathione metabolism, MAPK signaling pathway—plant, plant hormone signal transduction, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and ABC transporters (Figure 4c; Table S6), highlighting their roles in the Sb stress response in roots.

Figure 4.

Transcriptomic analysis of root tissues in B. juncea under control and 24-hour Sb-treated conditions. (a) Volcano plot of DEGs. (b) Heatmap of BjOPT gene expression. (c) GO enrichment analysis. Orange font denotes significant GO terms. (d) KEGG pathway analysis.

Further analysis showed that most genes in the BjOPT family were barely expressed in root tissues. Under Sb stress, four BjOPT7, two BjYSL1, and two BjYSL6 homologous genes were slightly down-regulated. Given the lack of evidence for OPT proteins participating in metal efflux or sequestration, this down-regulation may indicate a defensive tolerance mechanism against Sb toxicity. Based on previous findings that OPT overexpression enhances metal tolerance [22] and that loss-of-function mutants exhibit metal deficiency [21], the significant up-regulation of BjA10.YSL3, BjB02.YSL3, and BjB05.YSL3 (Figure 4d) strongly suggests a critical positive regulatory role for BjYSL3 in Sb tolerance.

2.7. Functional Analysis of BjOPTs in Mediating Sb Tolerance

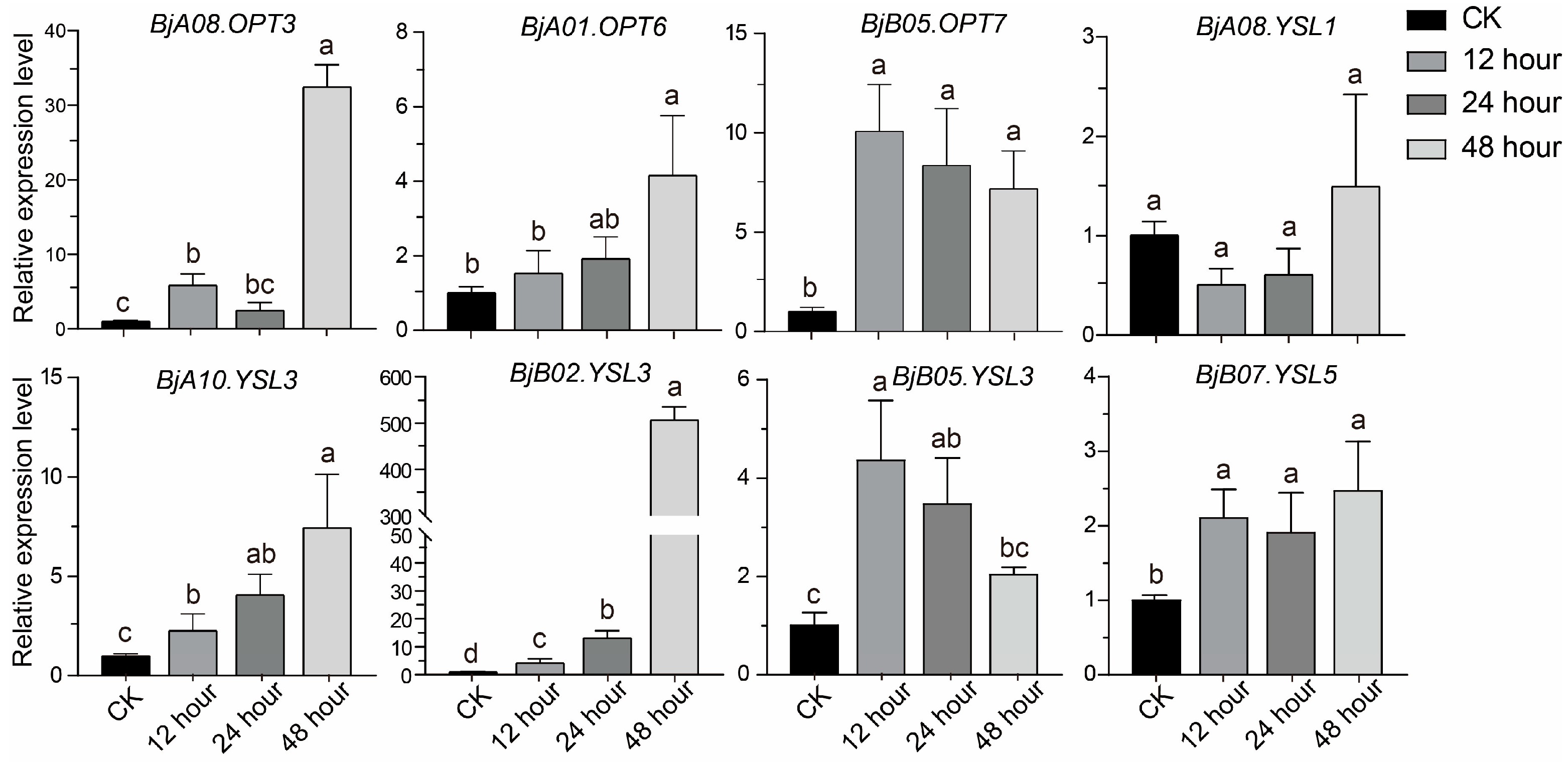

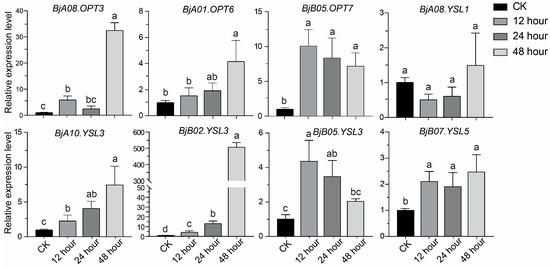

Transcriptome data revealed that several BjOPT genes responded significantly to Sb stress. To further evaluate their temporal expression patterns, we selected eight representative BjOPT genes (Table S7), based on tissue-specific expression profiles and transcriptomic responses, for qRT-PCR analysis. Expression levels were quantified in roots of B. juncea after 12, 24, and 48 h of Sb treatment (Figure 5). Consistent with transcriptome data, all three BjYSL3 homologs (BjA10.YSL3, BjB02.YSL3, and BjB05.YSL3) were up-regulated under Sb stress but exhibited distinct expression dynamics: BjA10.YSL3 and BjB02.YSL3 expression increased gradually, reaching 7.4-fold and 506.5-fold higher than the control at 48 h, respectively, while BjB05.YSL3 peaked at 12 h and subsequently declined. BjA08.OPT3 and BjA01.OPT6 showed no significant change at 24 h but were significantly induced at 48 h. Additionally, BjB05.OPT7 and BjB07.YSL5 also exhibited Sb-responsive up-regulation. These results demonstrate that multiple BjOPT genes are up-regulated under Sb stress, implicating their potential roles in Sb-NA complex transport or detoxification mechanisms.

Figure 5.

Expression patterns of eight representative genes under Sb stress at different time points. Different lowercase letters represent significant differences at p < 0.05 level using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s correction.

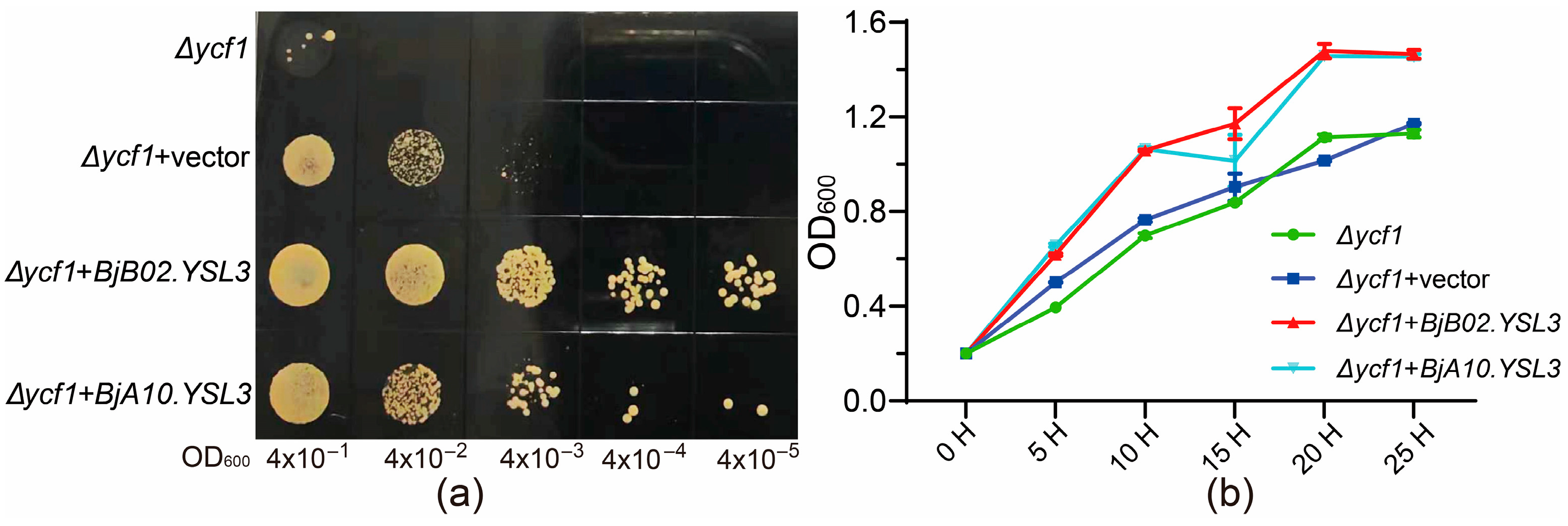

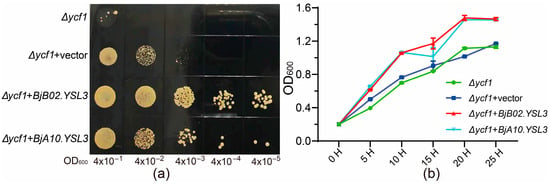

Based on the qRT-PCR results, the CDS sequences of BjA10.YSL3 and BjB02.YSL3 were cloned and inserted into the pYES2-NTB vector. The tolerance of yeast strains carrying these recombinant plasmids, as well as an empty vector control, was evaluated under 20 mM Sb(III) stress. Screening on SG-Ura solid medium demonstrated that heterologous expression of BjA10.YSL3 and BjB02.YSL3 significantly enhanced yeast Sb tolerance compared to the control (Δycf1 & Δycf1 + vector) (Figure 6a). Growth curves in liquid medium under Sb stress showed rapid increases in OD600 values across all treatments during the initial culture phase, stabilizing after approximately 20 h. However, the heterologous expression of BjA10.YSL3 and BjB02.YSL3 consistently resulted in higher OD values compared to the control throughout the experiment (Figure 6b). These findings suggest that both genes may play key roles in the transport of Sb-NA/PS complexes or Sb detoxification. However, whether they are directly involved in regulating Sb uptake and translocation requires further investigation.

Figure 6.

Analysis of heterologous gene expression under 20 mM Sb stress. (a) Screening of transformants with different OD values on SG-Ura solid medium. The labels from left to right indicate the OD600 values of serially diluted transformants. (b) OD600 values at different time points in SG-Ura liquid medium culture. n = 6.

3. Discussion

Sb poses significant health risks to humans, including chronic toxicity, carcinogenicity, and teratogenicity [30]. Our previous studies have demonstrated that B. juncea exhibits strong tolerance to multiple heavy metals (Mn2+, Fe2+, Zn2+, Cd2+, Sb3+, and Pb2+), with several BjMTP genes playing broad roles in the response to various heavy metal stresses [29]. The OPT family represents a group of proton-coupled transporters that play crucial roles in metal homeostasis, nitrogen mobilization, and sulfur distribution in plants [31]. Genome-wide identification of OPT family members has been completed in key plant species such as A. thaliana and rice, and the functions of some genes have been experimentally validated [15]. However, the identification of OPT genes in B. juncea, transcriptomic studies of its response to Sb stress, and functional characterization of BjOPT members under Sb exposure remain unreported. This study aims to identify BjOPT genes and integrate transcriptomic data from Sb-treated B. juncea to elucidate the key BjOPTs involved in the Sb stress response.

3.1. Expansion Characteristics of BjOPTs

In this study, a total of 47 BjOPTs (29 BjOPT and 18 BjYSL) were identified in the B. juncea genome through HMMER scanning combined with SMART, NCBI-CDD, and Pfam databases, along with 24 in B. rapa (13 BrOPT and 11 BrYSL) and 27 in B. nigra (13 BnOPT and 14 BnYSL). Notable differences in copy number were observed among BjOPT homologs: BjOPT8 was present in five copies, while BjOPT5/6 and BjYSL2/4/6/7 each had two copies, largely consistent with the combined contributions from the two progenitor species. These findings indicate that the OPT genes in Brassica species did not undergo triplication-derived expansion [32,33] following divergence from Arabidopsis (which possesses 9 AtOPT and 8 AtYSL), but rather experienced localized gene expansion, as evidenced by the presence of three copies of genes such as BrYSL1 (BrA01.YSL1/BrA03.YSL1/BrA08.YSL1) in B. rapa and BnYSL1 (BnB02.YSL1/BnB03.YSL1/BnB05.YSL1) in B. nigra. Intra-genomic synteny analysis further revealed that the expansion of BjOPT genes occurred primarily due to whole-genome duplication (WGD) events between the A and B subgenomes, accompanied by 16 segmental duplications and 3 tandem duplications. These results align with earlier findings in turnip [34], supporting the hypothesis that segmental duplications within subgenomes represent the major mechanism for BjOPT expansion, while tandem duplications play a secondary role.

Furthermore, divergence time estimation of the 51 putative BjOPT gene pairs revealed substantial variation (average: 25.1 MYA; range: 74.0–4.5 MYA), with 34 pairs diverging between 15.3 and 4.5 MYA. Considering that the Brassica–Arabidopsis split occurred approximately 24 MYA [35], and the divergence among diploid Brassica species (e.g., B. rapa, B. nigra, B. oleracea) is estimated to be between 20 MYA [36] and 7.9 MYA [37], preceding the recent (8000–14,000 years ago) allopolyploid origin of B. juncea [34]. We conclude that some BjOPT duplications predated the Brassica–Arabidopsis divergence, while the majority occurred during the diversification of its diploid progenitor species.

3.2. Divergence Between BjOPT and BjYSL Subfamilies

Previous phylogenetic studies have classified OPTs into two distinct subfamilies: OPT and YSL [11]. Functional differences have also been reported: the OPT subfamily is primarily involved in the transport of small peptides, glutathione, and metal chelates, whereas YSL proteins facilitate long-distance transport of metal–NA complexes, reflecting structural and functional divergence between the two subgroups [15]. Consistent with this, our study demonstrates clear differentiation between BjOPT and BjYSL genes in the phylogenetic tree, conserved motifs, and gene structure. For instance, BjOPTs generally possess more conserved motifs and fewer exons compared to BjYSL members. Similar patterns have been observed in turnip [34] and peanut [38], suggesting evolutionary conservation of OPT and YSL subfamilies across species. Although promoter cis-element profiles and tissue-specific expression patterns did not reveal systematic differences between the two subfamilies, homologous genes within each subfamily exhibited convergent expression behavior. This aligns with earlier observations in BjMTP homologs [29], implying that homologous heavy metal transporters may share conserved expression characteristics and perform similar biological functions.

3.3. Molecular Response Characteristics of B. juncea to Sb Stress

Studies indicate that Sb induces chlorosis, impairs photosynthesis, reduces membrane stability and nutrient uptake, and promotes oxidative stress via reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, thereby inhibiting plant growth and development [39]. Transcriptomic analyses have revealed transcriptional changes in response to Sb stress in many key species, including A. thaliana [40], Oryza sativa [41], Festuca arundinacea [42], and B. napus [43]. This study provides the first transcriptomic profile of the heavy metal-tolerant species B. juncea under Sb stress, uncovering widespread molecular changes with more than 20,000 DEGs. The abundance of DEGs may be attributed to the strong phytotoxicity of Sb, particularly its disruption of root cell membrane integrity (Figure S4c). Functional enrichment analysis showed that these DEGs were significantly associated with biological processes such as response to oxidative stress, toxic substance, toxin catabolic process, metal ion transport, and auxin efflux. Consistent with reports in F. arundinacea under Sb stress [42], GO terms related to stress response and oxidoreductase activity were significantly enriched. KEGG analysis revealed strong enrichment in glutathione metabolism, MAPK signaling, plant hormone signal transduction, and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Glutathione (GSH), a key antioxidant in plants, contributes critically to ROS scavenging and detoxification under stress and acts synergistically with phytohormone signaling to improve abiotic stress tolerance [44]. The glutathione pathway is widely implicated in heavy metal detoxification [45]. MAPKs, as key signal-transducing enzymes, are commonly activated by heavy metal stress, while Cd or Cu excess in Arabidopsis induces NADPH oxidase, H2O2 accumulation, and MAPK activation [46]. Based on the findings of this study, the non-essential heavy metal Sb is proposed to cause irreversible phytotoxicity through a multi-step mechanism. Sb exposure initially induces oxidative stress, triggering the activation of key genes associated with glutathione metabolism, MAPK signaling, and plant hormone transduction pathways to facilitate detoxification. Simultaneously, metal ion transport DEGs are likely involved in Sb translocation and cellular compartmentalization.

3.4. Potential Role of BjYSL3 Genes in Sb Tolerance

YSL proteins, key members of the OPT family, are involved in the transport of metal–NA/PS complexes and the maintenance of cellular metal homeostasis [15]. Functional characterization using metal-sensitive yeast mutants has become an established method for validating gene involvement in heavy metal detoxification, uptake, or efflux [47,48,49]. In this study, transcriptomic analysis identified three homologous BjYSL3 genes (BjA10.YSL3, BjB02.YSL3, and BjB05.YSL3) that were significantly responsive to Sb. Using qRT-PCR and functional complementation assays in yeast, we demonstrated that heterologous expression of BjA10.YSL3 and BjB02.YSL3 significantly enhanced Sb tolerance, with BjB02.YSL3 showing more pronounced effects both in expression and complementation. AtYSL3 in Arabidopsis is expressed in vascular tissues and suppressed under iron deficiency; it has been shown to transport Fe(II)-NA and Fe(III)-PS in yeast [48]. Similarly, TcYSL3 from Noccaea caerulescens (formerly Thlaspi caerulescens) mediates Fe(II)-NA and Ni-NA transport [48], and SnYSL3 from the hyperaccumulator Solanum nigrum is expressed in vascular and epidermal cells of roots and stems, transporting Fe(II)-, Cu-, Zn-, and Cd-NA complexes in yeast [47]. Consistent with these reports, the BjYSL3 homologs identified here are broadly expressed and may play key roles in Sb-NA/PS transport and Sb stress defense. However, whether BjYSL3 is directly involved in intracellular Sb detoxification, efflux, or reduced uptake requires further investigation.

In summary, this study systematically identifies high-confidence OPTs in B. juncea and elucidates their roles in Sb stress response through transcriptomics and yeast functional validation. The discovery of BjYSL3 as a series of tolerance genes provides a key genetic basis for improving crop adaptation to metal-contaminated soils via molecular breeding strategies such as allele introgression or transgenic approaches.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification and Characterization of OPT Family Proteins

Reference sequences of A. thaliana OPT family members (n = 17) were obtained from TAIR (https://www.arabidopsis.org (accessed on 10 August 2024)). Genomic and protein sequences of B. juncea cv. Sichuan Yellow were retrieved from the Oilseed Molecular Breeding Database (http://www.oilseedhunan.net (accessed on 10 August 2024)). To identify OPT proteins in B. juncea, an HMMER search was conducted using TBtools-II (v2.028) [50] with the conserved OPT domain (Pfam: PF03169) as the query (E-value threshold < 1 × 10−70). Candidate proteins were further verified using SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de (accessed on 12 August 2024)), NCBI-CDD (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd (accessed on 12 August 2024)), and Pfam to ensure domain integrity. Genomic data for B. rapa (Chiifu v3.5) and B. nigra (NI100 v2) were acquired from the Brassicaceae database (http://brassicadb.cn/#/ (accessed on 10 August 2024)), and their OPT proteins were identified using the same workflow.

Physicochemical parameters, including molecular weight, amino acid length, isoelectric point (pI), and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), were computed using TBtools-II. Subcellular localization was predicted with Plant-mPLoc (http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/plant-multi (accessed on 18 August 2024)), and transmembrane domains were inferred using TMHMM-2.0 (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0 (accessed on 18 August 2024)).

4.2. Phylogenetic, Chromosomal Location, Conserved Motif and Gene Structure Analyses

A multiple sequence alignment of OPT protein sequences from A. thaliana, B. rapa, B. nigra, and B. juncea was conducted using ClustalW in MEGA X (v11.0.13). A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed with 1000 bootstrap replicates and visualized with iTOL (https://itol.embl.de (accessed on 20 August 2024)). Chromosomal locations of BjOPT genes were mapped based on the GFF3 annotation file of Sichuan Yellow using TBtools-II.

Conserved protein motifs were predicted using the MEME suite (http://meme-suite.org (accessed on 20 August 2024)) with the maximum number of motifs set to 10. Exon–intron structures of BjOPT genes were derived from the B. juncea genome annotation. All conserved motifs, protein domains, and gene structures were visualized using TBtools-II.

4.3. Collinearity and Promoter Elements Analysis of BjOPTs

Synteny analysis of OPT genes among B. juncea, B. rapa, and B. nigra was performed using MCScanX implemented in Tbtools-II. To evaluate selection pressures, the nonsynonymous (Ka) to synonymous (Ks) substitution ratios were calculated for syntenic gene pairs across three comparative sets: B. juncea vs. B. juncea, B. juncea vs. B. rapa, and B. juncea vs. B. nigra. The divergence time of duplication events was estimated using the formula T = Ks/(2λ), with λ set to 1.5 × 10−8 mutations/site/year as the divergence rate for Brassicaceae [34].

For cis-regulatory element analysis, a 2000 bp upstream region of each BjOPT gene was extracted as the putative promoter sequence. These sequences were analyzed using PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/ (accessed on 21 August 2024)) to identify cis-elements related to plant hormones, abiotic stress, light responsiveness, and growth/development. The resulting elements were summarized and visualized through a promoter element heatmap.

4.4. Expression Profiling and GO Enrichment Analysis

To elucidate tissue-specific expression patterns of BjOPT genes, we analyzed RNA-seq datasets from various tissues of Sichuan Yellow, including roots, stems, leaves, buds, siliques at 7 and 15 days after flowering (DAF), pods at 20 DAF, seeds, and seed coats (accession numbers: SRR11787772-SRR11787783, SRR807368) from previous studies [23,29]. Gene expression levels were quantified using log2(FPKM + 1) and visualized as heatmaps. For functional annotation, all identified BjOPT family members were subjected to Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis using the Omicsmart platform (https://www.omicsmart.com/RNAseq/home.html (accessed on 22 August 2024)).

4.5. Plant Materials and Sb Stress Treatments

Plant materials and growth conditions were consistent with previously established methods [29]. Surface-sterilized seeds of Sichuan Yellow (using 50% sodium hypochlorite) were germinated on germination beds moistened with Hoagland’s solution. After one week, seedlings were transferred to black hydroponic containers filled with 1/2 Hoagland’s nutrient solution and grown under controlled conditions: 16/8 h light/dark photoperiod, 50–60% relative humidity, and 24 ± 2 °C. Based on the previously established optimal Sb concentration for B. napus [43], four-week-old B. juncea plants were treated with 75 mg/L Sb (supplied as KSbC4H4O7·0.5H2O; Analytical Reagent; Xilong Chemical Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China). After 24 h of treatment, fresh root tissues were stained with Evans Blue (Maokang Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) (10 min), rinsed with ddH2O, and then imaged. Additionally, root samples from both control and treated plants were collected at 12, 24, and 48 h post-exposure, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80 °C for subsequent analysis. Three biological replicates were included for each treatment condition.

4.6. RNA Extraction, Transcriptome Sequencing, and Functional Annotation

Total RNA was isolated from root tissues of control and Sb-treated (12, 24, and 48 h) plants using the RNAprep Pure Plant Plus Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA samples from control and 24 h Sb-treated roots (n = 6) were submitted for RNA sequencing at Nanjing Jisi Huiyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. RNA quality control and library construction were performed according to a previously described method [43], followed by sequencing on an Illumina NovaSeq 2500 platform. Clean reads were aligned to the Sichuan Yellow reference genome (http://www.oilseedhunan.net/download.html (accessed on 22 April 2025)), and gene expression was quantified using FPKM.

DEGs were identified with DESeq2 using thresholds of |log2FC| > 1 and adjusted p-value < 0.05. Results were visualized via volcano plots and heatmaps. Functional enrichment analyses of DEGs were performed using the GO (https://geneontology.org/ (accessed on 27 April 2025)) and KEGG pathway (http://www.kegg.jp (accessed on 27 April 2025)) databases, with significantly enriched terms defined as those with p < 0.05.

4.7. qRT-PCR Validation and Yeast Complementation Assay

cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Dalian, China). qRT-PCR was carried out in triplicate (biological and technical replicates) with SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara) on a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer Premier (v3.0). BjGAPDH [51] was used as the internal control, and relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method.

To validate the function of key Sb-responsive BjOPT genes, a yeast heterologous complementation assay was performed. Gene-specific primers were designed based on the yeast expression vector pYES2-NTB (ProNet Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China; plasmid schematic provided in Figure S5), and the coding sequences of BjOPT genes were amplified from cDNA templates derived from B. juncea roots treated with Sb for 24 h. The amplified fragments were subsequently cloned into the pYES2-NTB vector using homologous recombination. The resulting recombinant plasmids were transformed into the heavy metal-sensitive yeast mutant strain Δycf1. Transformants were selected on SG-Ura solid medium supplemented with 20 mM, followed by incubation at 30 °C. For liquid culture assays, both control and experimental groups were grown in SG-Ura liquid medium to an OD600 of 0.2, followed by addition of solid KSbC4H4O7·0.5H2O to adjust the Sb concentration to 20 mM. All cultures were incubated at 30 °C with shaking, and OD600 values were recorded every 5 h using an SP754 UV spectrophotometer (Spectrum Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

5. Conclusions

A total of 47 BjOPTs were identified in B. juncea and classified into OPT and YSL subfamilies. Phylogenetic relationships, conserved motifs, and gene structures revealed significant divergence between the subfamilies, whereas promoter cis-element distribution and tissue-specific expression patterns showed no systematic divergence between these two subgroups. Comparative and collinearity analyses among A. thaliana, allopolyploid B. juncea, and its diploid progenitor species indicated that OPTs in Brassica species did not undergo triplication during WGD; instead, most BjOPT genes expanded primarily through WGD and segmental duplication events. Transcriptomic profiling under Sb stress uncovered substantial DEGs associated with response to oxidative stress, toxic substances, metal ion transport, and auxin efflux, as well as key pathways such as glutathione metabolism, MAPK signaling, and plant hormone signal transduction, indicating their central roles in Sb detoxification and tolerance. Furthermore, three BjYSL3 homologs were strongly up-regulated under Sb stress. Yeast heterologous complementation assays demonstrated that BjA10.YSL3 and BjB02.YSL3 confer enhanced tolerance to Sb. These findings confirm that the BjYSL3 genes in B. juncea play a role in Sb tolerance, laying a foundation for further investigation into its underlying mechanism.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants14213399/s1, Figure S1: Chromosomal Localization Analysis of BjOPT Genes; Figure S2: Phylogenetic relationship, conserved motif, protein domain and gene structure analyses of BjOPT proteins; Figure S3: Heatmap of Cis-Regulatory element distribution in BjOPT promoters; Figure S4: Phenotypic response of B. juncea seedlings to Sb stress; Figure S5: Schematic diagram of the pYES2-NTB plasmid used in this study. Table S1: Physicochemical characterization of B. juncea OPTs; Table S2: Identification of OPTs in B. rapa and B. nigra; Table S3: Analysis of Ka/Ks ratios and divergence time in BjOPT homologous gene pairs; Table S4: Analysis of Ka/Ks ratios in BrOPT and BnOPT homologous gene pairs; Table S5: Transcriptome sequencing data of B. juncea root tissues under antimony stress; Table S6: Sb-responsive GO terms and KEGG pathways among DEGs; Table S7: Primer sequences used in this paper..

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and L.Y.; validation, X.L., Y.Y., S.G. and L.Y. .; formal analysis, M.C., J.S. and P.Z.; data curation, M.C., J.S. and P.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L., M.C., G.X. and L.Y.; writing—review and editing, Z.L., J.H., M.Y., Y.C. and L.Y.; visualization, X.L. and L.Y.; supervision, X.L.; project administration, S.G.; funding acquisition, L.Y., Y.Y. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Hunan Province, China (23B0809), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2025JJ70318, 2023JJ50083) and the construct program of plant protection applied characteristic discipline in Hunan Province.

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data for Sb treatment and control are available under the National Genomics Data Center (NGDC) accession PRJCA046671, whereas the RNA-seq data from various Brassica juncea tissues are accessible under NCBI SRA accessions SRR11787772, SRR11787777, SRR11787776, SRR11787782, SRR11787779, SRR11787783, SRR11787780, SRR11787781, and SRR807368.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Sb | Antimony |

| Mn | Manganese |

| Zn | Zinc |

| Cu | Copper |

| Cd | Cadmium |

| Ni | Nickel |

| Fe | Iron |

| Cr | Chromium |

| NA | Nicotianamine |

| PS | Phytosiderophores |

| YSL | Yellow Stripe-Like |

| OPT | Oligopeptide Transporter |

| MTP | Metal Tolerance Protein |

| ABC | ATP-binding Cassette Transporter |

| HMA | Heavy Metal ATPase |

| pI | Isoelectric Point |

| GRAVY | Grand Average of Hydropathicity |

| Ka | Nonsynonymous |

| Ks | Synonymous |

| DAF | Days After Flowering |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| FPKM | Fragments per Kilobase of Transcript per Million Fragments Mapped |

| DEG | Differentially Expressed Gene |

| CRE | Cis-regulatory Element |

| WGD | Whole-genome Duplication |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

References

- United States Geological Survey (USGS). Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2025/mcs2025-antimony.pdf2025; (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- He, M.; Wang, X.; Wu, F.; Fu, Z. Antimony pollution in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 421, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diquattro, S.; Castaldi, P.; Ritch, S.; Juhasz, A.L.; Brunetti, G.; Scheckel, K.G.; Garau, G.; Lombi, E. Insights into the fate of antimony (Sb) in contaminated soils: Ageing influence on Sb mobility, bioavailability, bioaccessibility and speciation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 770, 145354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, N.; Kumar, M.; Singh, E.; Kumar, A.; Singh, L.; Kumar, S.; Keerthanan, S.; Hoang, S.A.; El-Naggar, A.; Vithanage, M.; et al. Antimony contamination and its risk management in complex environmental settings: A review. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okkenhaug, G.; Grasshorn Gebhardt, K.A.; Amstaetter, K.; Bue, H.L.; Herzel, H.; Mariussen, E.; Rossebø Almås, Å.; Cornelissen, G.; Breedveld, G.D.; Rasmussen, G.; et al. Antimony (Sb) and lead (Pb) in contaminated shooting range soils: Sb and Pb mobility and immobilization by iron based sorbents, a field study. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 307, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniadis, V.; Golia, E.E.; Liu, Y.T.; Wang, S.L.; Shaheen, S.M.; Rinklebe, J. Soil and maize contamination by trace elements and associated health risk assessment in the industrial area of Volos, Greece. Environ. Int. 2019, 124, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Tulcan, R.X.S.; He, M.; Ouyang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Yarleque, C.M.H.; Chicaiza-Ortiz, C. Antimony pollution threatens soils and riverine habitats across China: An analysis of antimony concentrations, changes, and risks. Crit. Rev. Env. Sci. Tec. 2024, 54, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Su, H.; Li, H.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, F. Ecological and human health risk assessment of antimony (Sb) in surface and drinking water in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; He, G.; Tian, W.; Saleem, M.; Li, D.; Huang, Y.; Meng, L.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, T. OPT gene family analysis of potato (Solanum tuberosum) responding to heavy metal stress: Comparative omics and co-expression networks revealed the underlying core templates and specific response patterns. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 188, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.D.; Meng, J.G.; Zhao, K.X.; Chen, X.; Yang, Z.M. Annotation and characterization of Cd-responsive metal transporter genes in rapeseed (Brassica napus). Biometals 2018, 31, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomolplitinant, K.M.; Saier, M.H., Jr. Evolution of the oligopeptide transporter family. J. Membr. Bio 2011, 240, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, H.; Stacey, G.; Gassmann, W. ScOPT1 and AtOPT4 function as proton-coupled oligopeptide transporters with broad but distinct substrate specificities. Biochem. J. 2006, 393, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaaf, G.; Ludewig, U.; Erenoglu, B.E.; Mori, S.; Kitahara, T.; von Wirén, N. ZmYS1 functions as a proton-coupled symporter for phytosiderophore- and nicotianamine-chelated metals. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 9091–9096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubkowitz, M.A.; Hauser, L.; Breslav, M.; Naider, F.; Becker, J.M. An oligopeptide transport gene from Candida albicans. Microbio 1997, 143, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Joon, R.; Singh, G.; Singh, J.; Pandey, A.K. The multifaceted role of YSL proteins: Iron transport and emerging functions in plant metal homeostasis. Bba-Gen Subj. 2025, 1869, 130792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, M.G.; Koh, S.; Becker, J.; Stacey, G. AtOPT3, a member of the oligopeptide transporter family, is essential for embryo development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 2799–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, M.W.; Li, G.W.; Lubkowitz, M.A.; Grusak, M.A. Characterization of the PT Clade of Oligopeptide Transporters in Rice. Plant Genome 2008, 1, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, W.; Xu, K.; Xie, W.; Qi, H.; Tang, Y.; Wang, S.; Deng, T.; Morel, J.L.; Qiu, R. Fe(III) transporter OsYSL15 may play a key role in the uptake of Cr(III) in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkaew, A.; Asayama, K.; Kitaiwa, T.; Nakamura, S.I.; Kojima, K.; Stacey, G.; Sekimoto, H.; Yokoyama, T.; Ohkama-Ohtsu, N. AtOPT6 protein functions in long-distance transport of glutathione in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 1443–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiDonato, R.J., Jr.; Roberts, L.A.; Sanderson, T.; Eisley, R.B.; Walker, E.L. Arabidopsis Yellow Stripe-Like2 (YSL2): A metal-regulated gene encoding a plasma membrane transporter of nicotianamine-metal complexes. Plant J. 2004, 39, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, B.M.; Chu, H.H.; Didonato, R.J.; Roberts, L.A.; Eisley, R.B.; Lahner, B.; Salt, D.E.; Walker, E.L. Mutations in Arabidopsis yellow stripe-like1 and yellow stripe-like3 reveal their roles in metal ion homeostasis and loading of metal ions in seeds. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 1446–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Chai, T.Y. Molecular cloning and characterization of a Brassica juncea yellow stripe-like gene, BjYSL7, whose overexpression increases heavy metal tolerance of tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 2013, 32, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Qian, L.; Zheng, M.; Chen, L.; Chen, H.; Yang, L.; You, L.; Yang, B.; Yan, M.; Gu, Y.; et al. Genomic insights into the origin, domestication and diversification of Brassica juncea. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 1392–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duquène, L.; Vandenhove, H.; Tack, F.; Meers, E.; Baeten, J.; Wannijn, J. Enhanced phytoextraction of uranium and selected heavy metals by Indian mustard and ryegrass using biodegradable soil amendments. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 1496–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, X.; Yang, W.; Chen, R. Identification and characterization of yellow stripe-like genes in maize suggest their roles in the uptake and transport of zinc and iron. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Sen, M.; Saha, C.; Chakraborty, D.; Das, A.; Banerjee, M.; Seal, A. Isolation and expression analysis of partial sequences of heavy metal transporters from Brassica juncea by coupling high throughput cloning with a molecular fingerprinting technique. Planta 2011, 234, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, A.E.; Orengo, C.A.; Thornton, J.M. Evolution of function in protein superfamilies, from a structural perspective. J. Mol. Bio 2001, 307, 1113–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Guo, C.; Shan, H.; Kong, H. Divergence of duplicate genes in exon-intron structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Sheng, J.; Jiang, G.; Chen, H.; Yuan, Y.; Gong, S.; Yan, M.; Hu, J.; Xiang, G.; Duan, R.; et al. Molecular characterization and expression patterns of MTP genes under heavy metal stress in mustard (Brassica juncea L.). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saerens, A.; Ghosh, M.; Verdonck, J.; Godderis, L. Risk of Cancer for Workers Exposed to Antimony Compounds: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubkowitz, M. The oligopeptide transporters: A small gene family with a diverse group of substrates and functions? Mol. Plant 2011, 4, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schranz, M.E.; Lysak, M.A.; Mitchell-Olds, T. The ABC’s of comparative genomics in the Brassicaceae: Building blocks of crucifer genomes. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vision, T.J.; Brown, D.G.; Tanksley, S.D. The origins of genomic duplications in Arabidopsis. Science 2000, 290, 2114–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Yang, D.; Yin, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Q.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y. Genome-wide analysis indicates diverse physiological roles of the turnip (Brassica rapa var. rapa) oligopeptide transporters gene family. Plant Divers. 2018, 40, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, M.A.; Haubold, B.; Mitchell-Olds, T. Comparative evolutionary analysis of chalcone synthase and alcohol dehydrogenase loci in Arabidopsis, Arabis, and related genera (Brassicaceae). Molbio Evol 2000, 17, 1483–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, T.; Beilstein, M.A.; Tang, M.; McKain, M.R.; Pires, J.C. Diversification times among Brassica (Brassicaceae) crops suggest hybrid formation after 20 million years of divergence. Am. J. Bot. 2014, 101, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysak, M.A.; Koch, M.A.; Pecinka, A.; Schubert, I. Chromosome triplication found across the tribe Brassiceae. Genome Res. 2005, 15, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Guan, J.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, G. Genome-wide identification and transcript analysis reveal potential roles of oligopeptide transporter genes in iron deficiency induced Cadmium accumulation in Peanut. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 894848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Meng, G.; Xiang, J.; Mahmood, A.; Xiang, G.; SanaUllah; Liu, Y.; Huang, G. Toxic effects of antimony in plants: Reasons and remediation possibilities-A review and future prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1011945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; He, M.; Lin, C.; Ouyang, W.; Liu, X. Uptake, accumulation and gene response of Sb(V) in Arabidopsis thaliana. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 288, 117371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, B.; Yang, F.; Ding, Y.; Liu, H.; et al. Selenite affected photosynthesis of Oryza sativa L. exposed to antimonite: Electron transfer, carbon fixation, pigment synthesis via a combined analysis of physiology and transcriptome. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 201, 107904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, K.; Xiang, Y.; Wu, F.; Yan, X.; Wen, B. Transcriptomic and metabolomic insights into the antimony stress response of tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 933, 172990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; You, L.; Yu, W.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yan, M.; Zheng, Y.; Duan, R.; Meng, G.; Chen, Y.; et al. Transcriptome profiles of leaves and roots of Brassica napus L. in response to antimony stress. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, G.K.; Kumar, P.; Choudhary, S.M.; Singh, H.; Adab, K.; Kosser, R.; Magotra, I.; Kumar, R.R.; Singh, M.; Sharma, R.; et al. Antioxidant potential of glutathione and crosstalk with phytohormones in enhancing abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plants 2023, 12, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Ren, J.; Lin, X.; Yang, Z.; Deng, X.; Ke, Q. Melatonin alleviates chromium toxicity in Maize by modulation of cell wall polysaccharides biosynthesis, glutathione metabolism, and antioxidant capacity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdenakker, K.; Remans, T.; Keunen, E.; Vangronsveld, J.; Cuypers, A. Exposure of Arabidopsis thaliana to Cd or Cu excess leads to oxidative stress mediated alterations in MAPKinase transcript levels. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2012, 83, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Tan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, S.; Xiang, S.; Wang, H.; Chai, T. Isolation and characterization of a novel cadmium-regulated Yellow Stripe-Like transporter (SnYSL3) in Solanum nigrum. Plant Cell Rep. 2017, 36, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.H.; Chiecko, J.; Punshon, T.; Lanzirotti, A.; Lahner, B.; Salt, D.E.; Walker, E.L. Successful reproduction requires the function of Arabidopsis Yellow Stripe-Like1 and Yellow Stripe-Like3 metal-nicotianamine transporters in both vegetative and reproductive structures. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gendre, D.; Czernic, P.; Conéjéro, G.; Pianelli, K.; Briat, J.F.; Lebrun, M.; Mari, S. TcYSL3, a member of the YSL gene family from the hyper-accumulator Thlaspi caerulescens, encodes a nicotianamine-Ni/Fe transporter. Plant J. 2007, 49, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandna, R.; Augustine, R.; Bisht, N.C. Evaluation of candidate reference genes for gene expression normalization in Brassica juncea using real time quantitative RT-PCR. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).