ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy Analysis of Biochemical Alterations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms Following Antibiotic and Probiotic Treatments

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Assay

2.3. Biofilm Preparation

2.4. Biofilm Evaluation Assay

2.5. FTIR Spectroscopy Measurement Procedure

2.6. Data Analysis Procedures

3. Results and Discussion

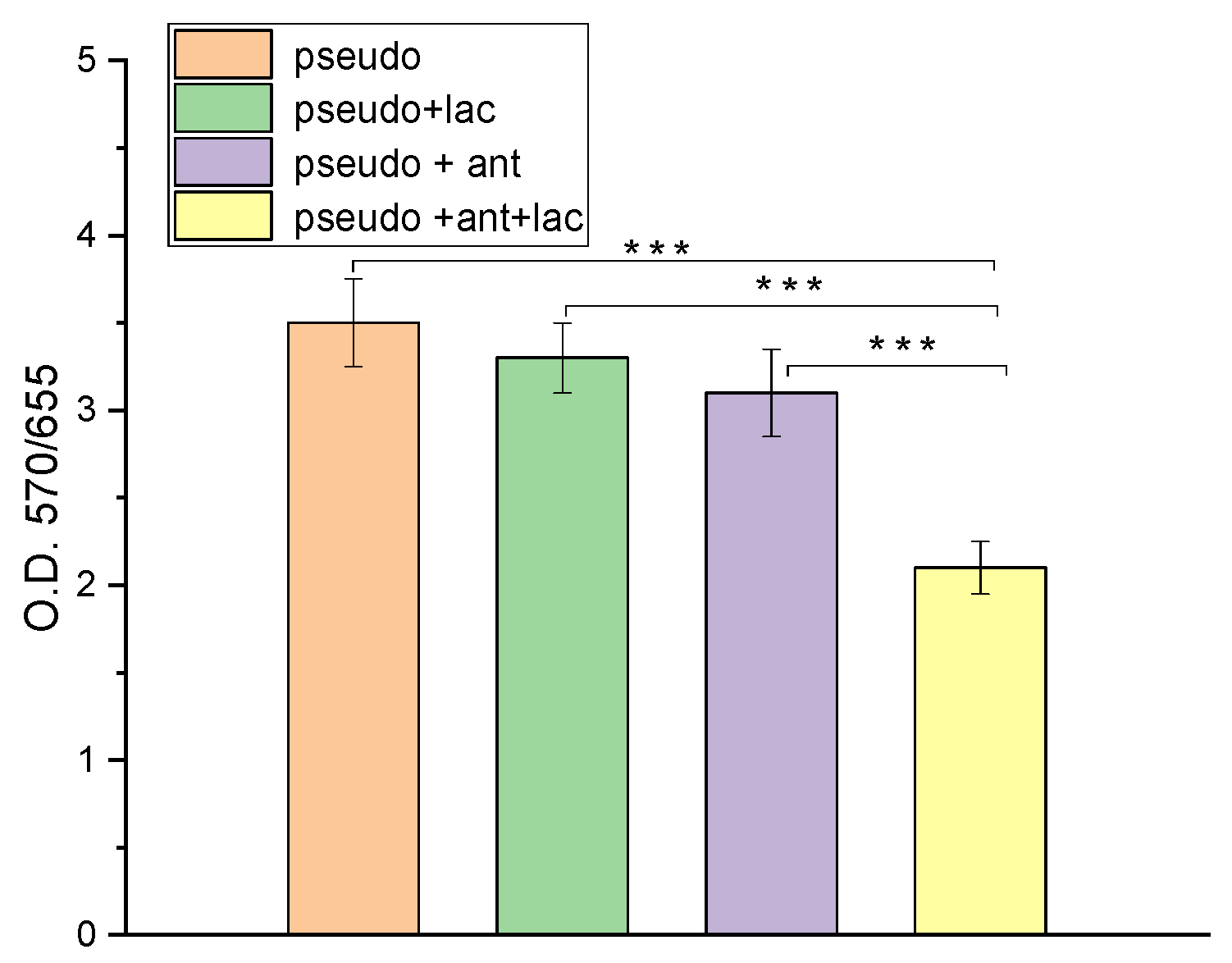

3.1. Results of Biofilm Formation by Crystal Violet Assay

3.2. FTIR Spectroscopy Investigation Results

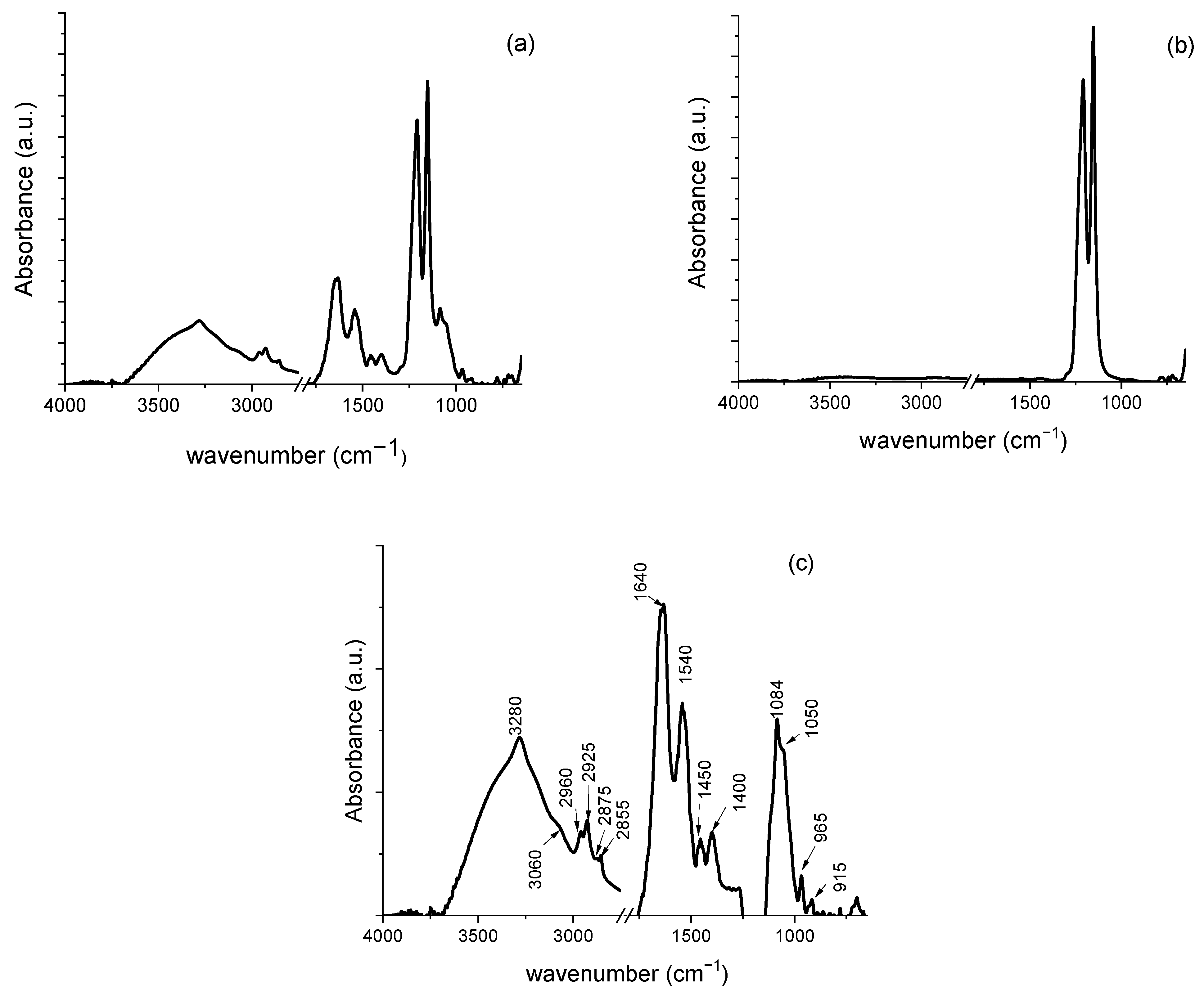

3.2.1. Characterization of P. aeruginosa Biofilms on Teflon Membranes

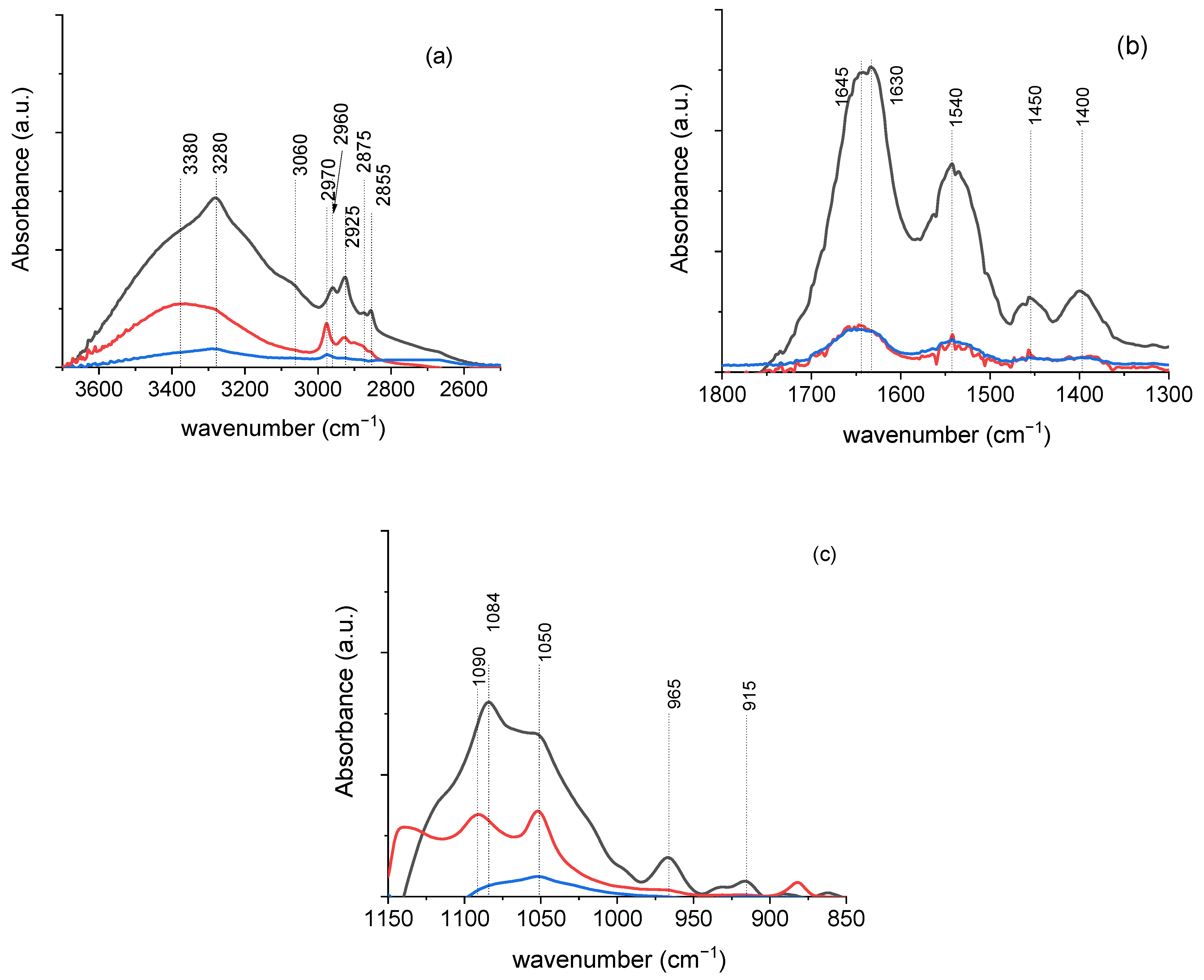

3.2.2. Characterization of P. aeruginosa Biofilms After Antibiotic Treatment in the Absence and the Presence of L. plantarum Probiotic Agents

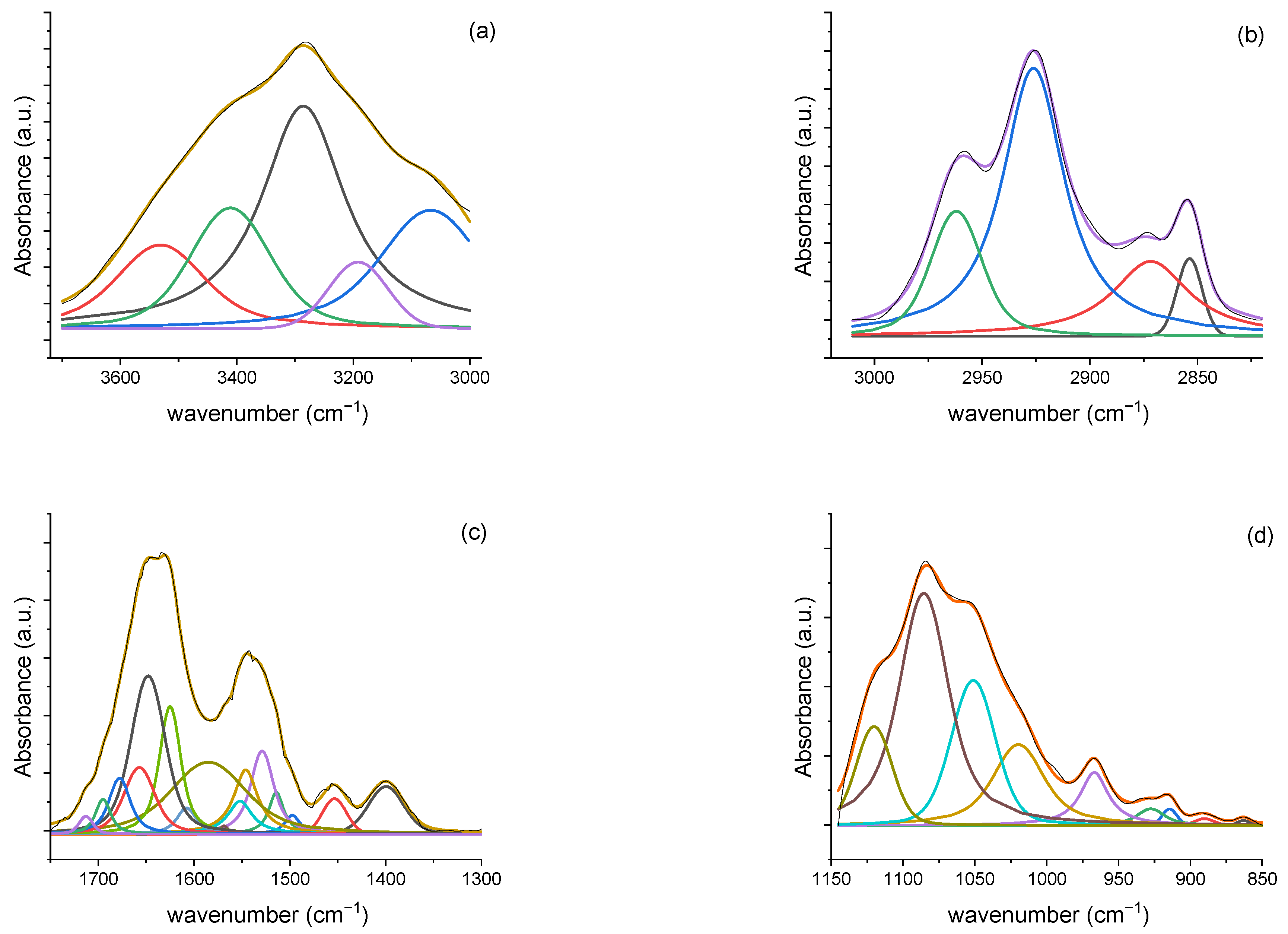

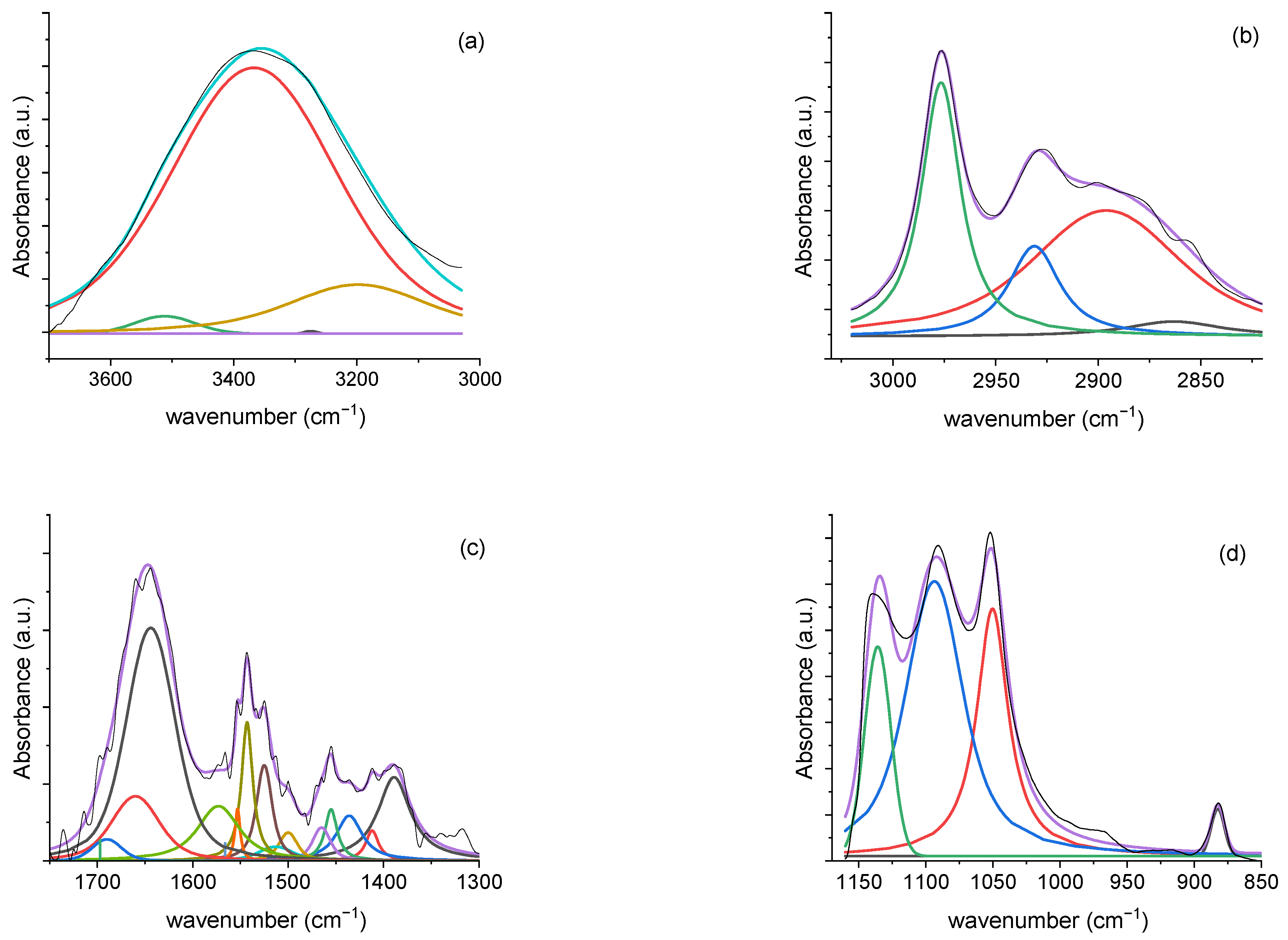

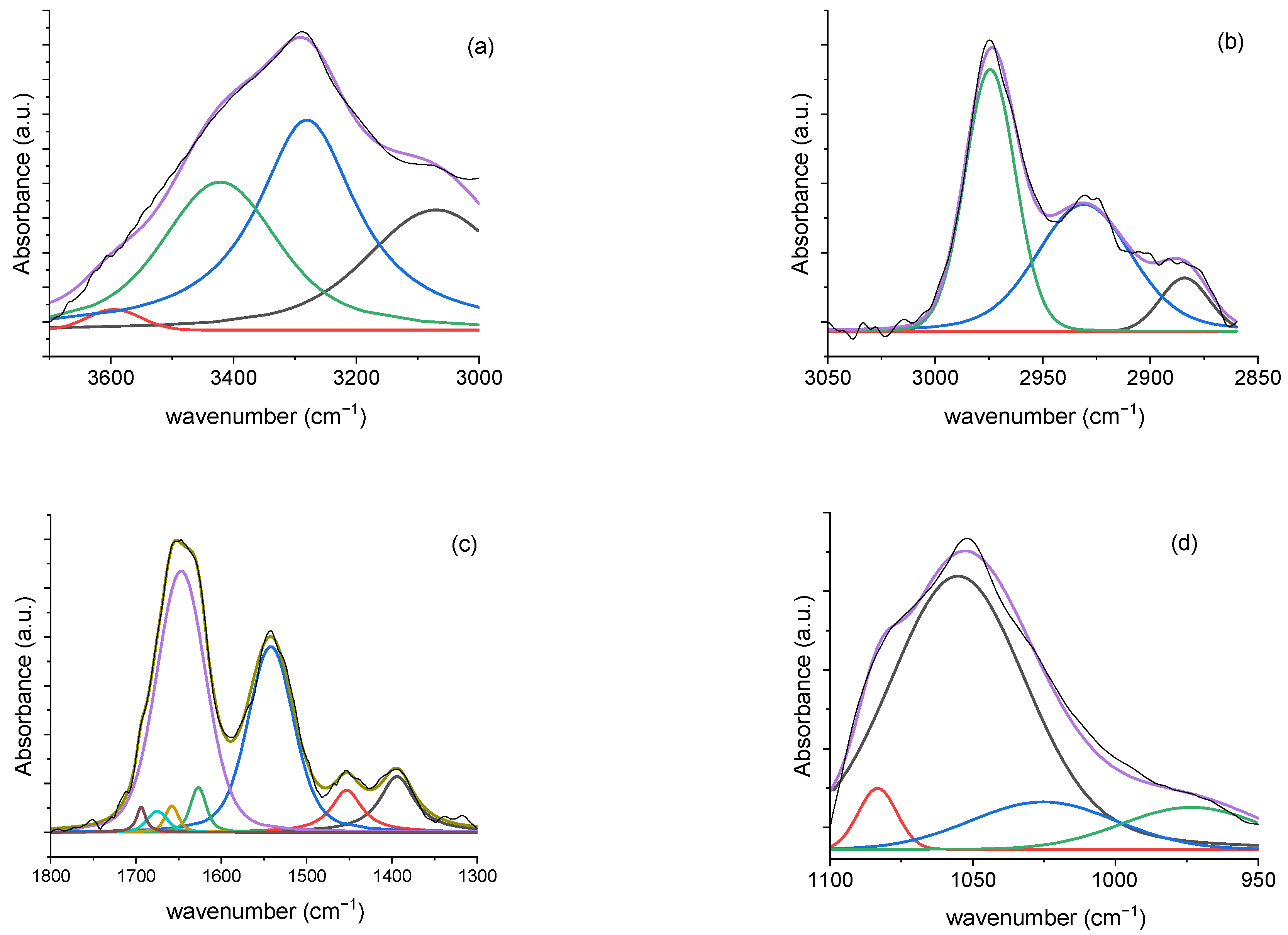

3.2.3. Deconvolution Analysis Results

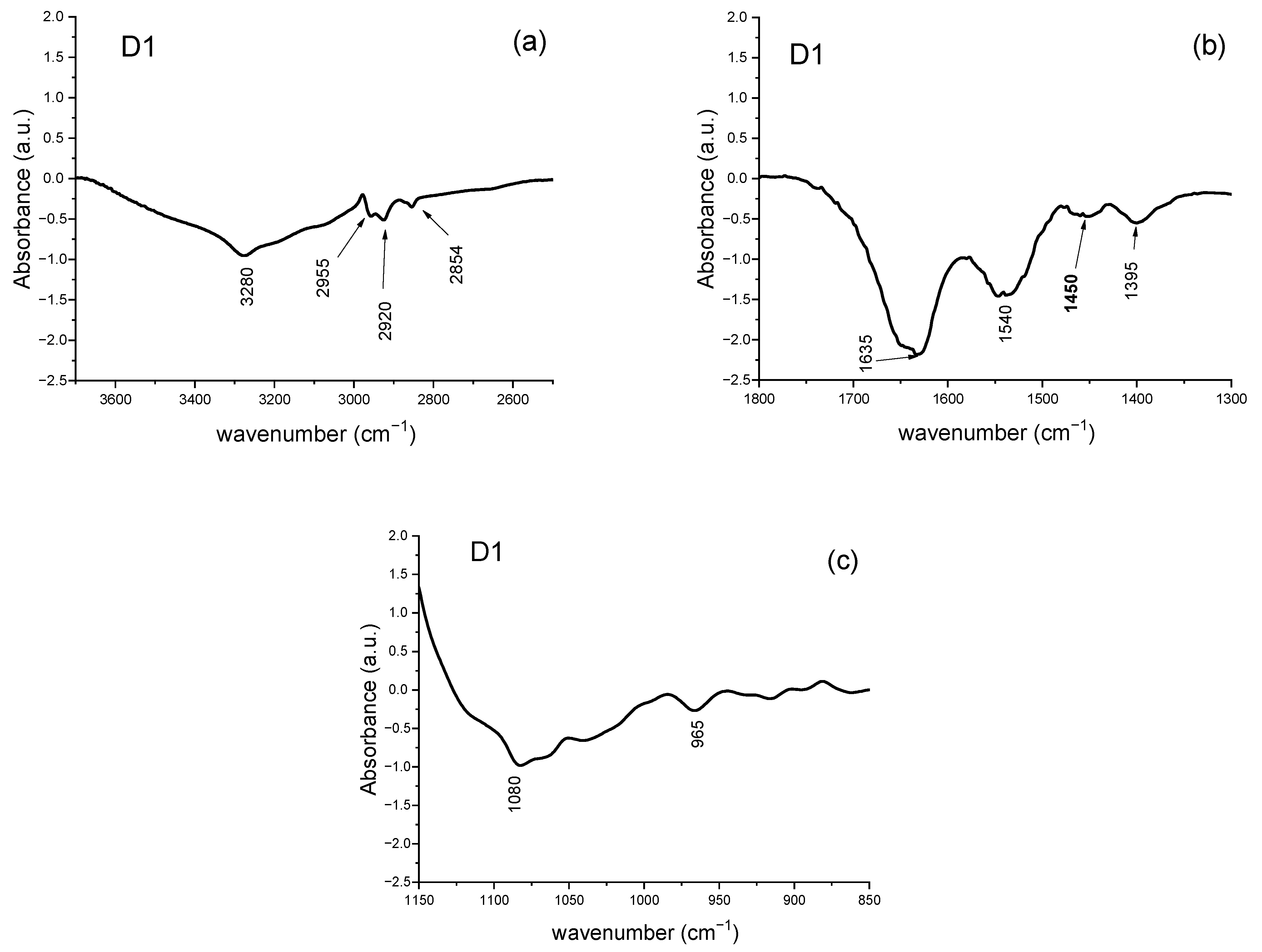

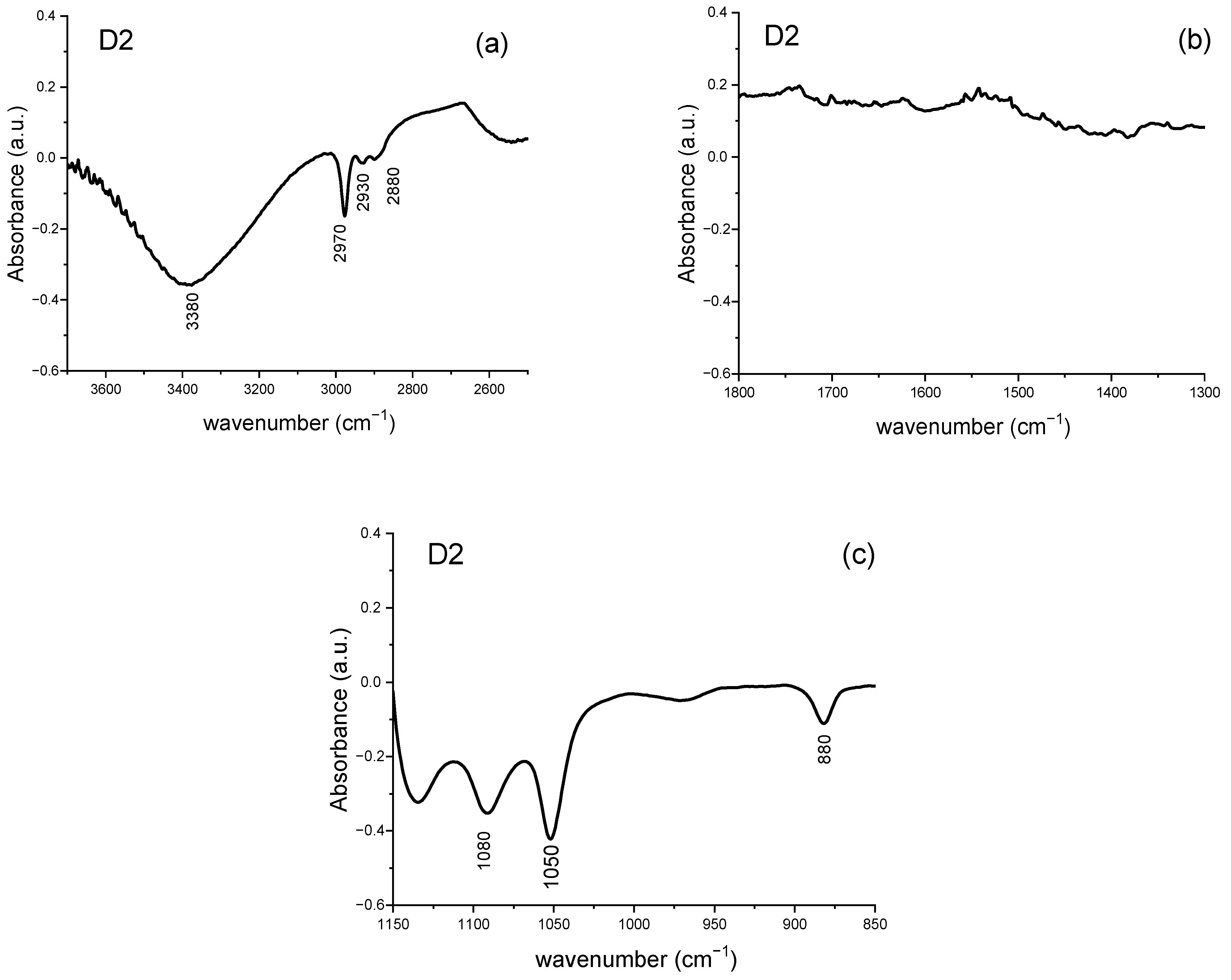

3.2.4. Analysis of Difference Spectra

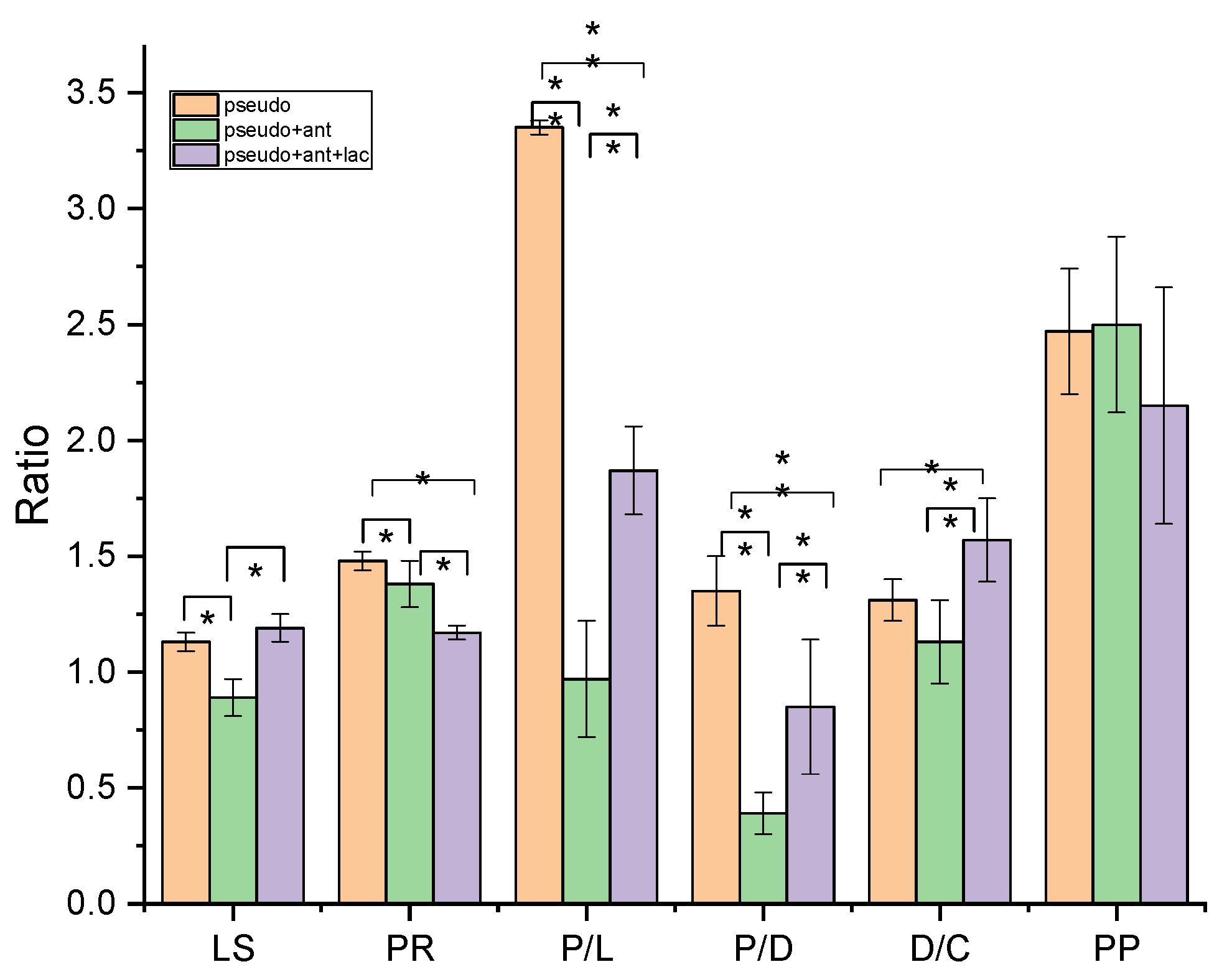

3.2.5. Ratiometric Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFU | Colony-Forming Unit |

| EPS | Exopolysaccharide matrix |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared |

| MIC | Minimal Inhibitory Concentration |

| MRS | Man, Rogosa and Sharpe |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| SNV | Standard Normal Variate |

| TSB | Tryptone Soy Broth |

References

- Di Martino, P. Extracellular polymeric substances, a key element in understanding biofilm phenotype. AIMS Microbiol. 2018, 4, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, A.; Savio, V.; Stelitano, D.; Baroni, A.; Donnarumma, G. The Intestinal Biofilm of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus Is Inhibited by Antimicrobial Peptides HBD-2 and HBD-3. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, D.; Rumbaugh, K. The Consequences of Biofilm Dispersal on the Host. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 10738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, M.; Amare, A. Biofilm-Associated Multi-Drug Resistance in Hospital-Acquired Infections: A Review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 5061–5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Aggarwal, A.; Khan, F. Medical Device-Associated Infections Caused by Biofilm-Forming Microbial Pathogens and Controlling Strategies. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, L.R.; Isabella, V.M.; Lewis, K. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in disease. Microb. Ecol. 2014, 68, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, W.K.; Gagnon, P.M.; Vogel, J.P.; Chole, R.A. Surface charge modification decreases Pseudomonas aeruginosa adherence in vitro and bacterial persistence in an in vivo implant model. Laryngoscope 2017, 127, 1655–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, J.; Coenye, T. Biofilm dispersion: The key to biofilm eradication or opening Pandora’s box? Biofilm 2020, 2, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chegini, Z.; Khoshbayan, A.; Taati Moghadam, M.; Farahani, I.; Jazireian, P.; Shariatiet, A. Bacteriophage therapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: A review. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2020, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Yu, X.; Guo, W.; Guo, C.; Guo, X.; Li, Q.; Zhu, Y. Bacteriophage-Mediated Control of Biofilm: A Promising New Dawn for the Future. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 825828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halawa, E.M.; Fadel, M.; Al-Rabia, M.W.; Behairy, A.; Nouh, N.A.; Abdo, M.; Olga, R.; Fericean, L.; Atwa, A.M.; El-Nablaway, M.; et al. Antibiotic action and resistance: Updated review of mechanisms, spread, influencing factors, and alternative approaches for combating resistance. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 14, 1305294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, F.; Castagna, T.; Pantolini, B.; Campanardi, M.C.; Roperti, M.; Grotto, A.; Fattori, M.; Dal Maso, L.; Carrara, F.; Zambarbieri, G.; et al. The challenge of antimicrobial resistance (AMR): Current status and future prospects. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 9603–9615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, F.M.; Teixeira-Santos, R.; Mergulhão, F.J.M.; Gomes, L.C. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum Biofilms on the Adhesion of Escherichia coli to Urinary Tract Devices. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, A.; Savio, V.; Cimini, D.; D’Ambrosio, S.; Chiaromonte, A.; Schiraldi, C.; Donnarumma, G. In Vitro Evaluation of the Most Active Probiotic Strains Able to Improve the Intestinal Barrier Functions and to Prevent Inflammatory Diseases of the Gastrointestinal System. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhurajeshwar, C.; Chandrakanth, R.K. Probiotic potential of Lactobacilli with antagonistic activity against pathogenic strains: An in vitro validation for the production of inhibitory substances. Biomed. J. 2017, 40, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekky, A.F.; Hassanein, W.A.; Reda, F.M.; Elsayed, H.M. Anti-biofilm potential of Lactobacillus plantarum Y3 culture and its cell-free supernatant against multidrug-resistant uropathogen Escherichia coli U12. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 2989–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Hu, X.; Liu, W. Current Status of Probiotics as Supplements in the Prevention and Treatment of Infectious Diseases. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 789063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayamohan, P.; Joseph, D.; Viju, L.S.; Baskaran, S.A.; Venkitanarayanan, K. Efficacy of Probiotics in Reducing Pathogenic Potential of Infectious Agents. Fermentation 2024, 10, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, E.Z. Antimicrobial and anti-adhesive properties of biosurfactant produced by lactobacilli isolates, biofilm formation and aggregation ability. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 59, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javadi, K.; Emadzadeh, M.R.; Mohammadzadeh Hosseini Moghri, S.A.H.; Halaji, M.; Parsian, H.; Rajabnia, M.; Pournajaf, A. Anti-biofilm and antibacterial effect of bacteriocin derived from Lactobacillus plantarum on the multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Protein Expr. Purif. 2025, 226, 106610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilova, T.A.; Adzhieva, A.A.; Danilina, G.A.; Polyakov, N.B.; Soloviev, A.I.; Zhukhovitsky, V.G. Antimicrobial Activity of Supernatant of Lactobacillus plantarum against Pathogenic Microorganisms. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019, 167, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batoni, G.; Catelli, E.; Kaya, E.; Pompilio, A.; Bianchi, M.; Ghelardi, E.; Di Bonaventura, G.; Esin, S.; Maisetta, G. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Effects of Lactobacilli Strains against Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa under Conditions Relevant to Cystic Fibrosis. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalifar, H.; Rahimi, H.; Samadi, N.; Shahverdi, A.; Sharifian, Z.; Hosseini, F.; Eslahi, H.; Fazeli, M. Antimicrobial Activity of Different Lactobacillus species against Multi- Drug Resistant Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2011, 3, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Shokri, D.; Khorasgani, M.R.; Mohkam, M.; Fatemi, S.M.; Ghasemi, Y.; Taheri-Kafrani, A. The Inhibition Effect of Lactobacilli against Growth and Biofilm Formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2018, 10, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, A.; Abbas, L.; Coutinho, O.; Opara, S.; Najaf, H.; Kasperek, D.; Pokhrel, K.; Li, X.; Tiquia-Arashiro, S. Applications of Fourier Transform-Infrared spectroscopy in microbial cell biology and environmental microbiology: Advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1304081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Shi, H.; Feng, B.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Zhang, L.; Shen, H.; Zhu, J.; Yang, S.; et al. Protocol for bacterial typing using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. STAR Protoc. 2023, 15, 102223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, B.; Shi, H.; Xu, F.; Hu, F.; He, J.; Yang, H.; Huayan, Y.; Chuanfan, D.; Wenxiang, C.; Shaoning, Y. FTIR-assisted MALDI-TOF MS for the identification and typing of bacteria. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1111, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, N.M.R.D.; Lourenço, F.R. Rapid identification of microbial contaminants in pharmaceutical products using a PCA/LDA-based FTIR-ATR method. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 57, 8899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Yang, F.; Shi, H.; Yan, J.; Shen, H.; Yu, S.; Gan, N.; Feng, B.; Wang, L. Protein FT-IR amide bands are beneficial to bacterial typing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 207, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchaamba, F.; Stephan, R. A Comprehensive Methodology for Microbial Strain Typing Using Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Methods Protoc. 2024, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, C.E.E.; Lakshmi, P.K.; Meenakshi, S.; Vaidyanathan, S.; Srisudha, S.; Mary, M.B. Biomolecular transitions and lipid accumulation in green microalgae monitored by FT-IR and Raman analysis. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2020, 224, 117382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain, O.; Funk, C. Detailed characterization of the cell wall structure and composition of Nordic green microalgae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 9711–9721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashajyothi, M.; Balamurugan, A.; Patel, A.; Krishnappa, C.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, A. Cell wall polysaccharides of endophytic Pseudomonas putida elicit defense against rice blast disease. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxac042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Ezhov, A.A.; Vigovskiy, M.A.; Grigorieva, O.A.; Dyachkova, U.D.; Belogurova, N.G.; Kudryashova, E.V. Application prospects of FTIR spectroscopy and CLSM to monitor the drugs interaction with bacteria cells localized in macrophages for diagnosis and treatment control of respiratory diseases. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Wang, P.; Hou, J.; Yao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, S. Low concentrations of copper oxide nanoparticles alter microbial community structure and function of sediment biofilms. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.M.; Zayed, A.A.; Crossen, K.B.; Woodcroft, B.; Tfaily, M.M.; Emerson, J.; Raab, N.; Hodgkins, S.B.; Verbeke, B.; Tyson, G.; et al. Functional capacities of microbial communities to carry out large scale geochemical processes are maintained during ex situ anaerobic incubation. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanwal, P.; Kumar, A.; Dudeja, S.; Badgujar, H.; Chauhan, R.; Kumar, A.; Dhull, P.; Chhokar, V.; Beniwal, V. Biosorption of heavy metals from aqueous solution by bacteria isolated from contaminated soil. Water Environ. Res. 2018, 90, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, G.; Liu, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, F.; Guo, Y.; Wang, C.; Song, L. Biosorption and bioreduction of aqueous chromium (VI) by different Spirulina strains. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2023, 370, fnad070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáceda Quiroz, C.J.; Fora Quispe, G.d.L.; Carpio Mamani, M.; Maraza Choque, G.J.; Sacari Sacari, E.J. Cyanide bioremediation by Bacillus subtilis under alkaline conditions. Water 2023, 15, 3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, F.; Lashaniand, E.; Moghimi, H. Simultaneous bioremediation of phenol and tellurite by Lysinibacillus sp. EBL303 and characterization of biosynthesized Te nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarsini, M.; Thurotte, A.; Veidl, B.; Amiard, F.; Niepceron, F.; Badawi, M.; Lagarde, F.; Schoefs, B.; Marchand, J. Metabolite quantification by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy in diatoms: Proof of concept on Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 75642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.M.; Guimarães, F.E.G.; Yakovlev, V.V.; Bagnato, V.S.; Blanco, K.C. Physicochemical mechanisms of bacterial response in the photodynamic potentiation of antibiotic effects. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.; Nivens, D.; White, D.C.; Flemming, H.C. Changes of biofilm properties in response to sorbed substances—An FTIR-ATR study. Wat. Sci. Technol. 1995, 32, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, A.; Serra, D.; Prieto, C.; Schmitt, J.; Naumann, D.; Yantorno, O. Characterization of Bordetella pertussis growing as biofilm by chemical analysis and FT-IR spectroscopy. Appl. Microb. Biotechnol. 2006, 71, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, J.; Ow, S.Y.; Noirel, J.; Biggs, C.A. Quantitative protein expression and cell surface characteristics of Escherichia coli MG1655 biofilms. Proteomics 2011, 11, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tugarova, A.V.; Scheludko, A.V.; Dyatlova, Y.A.; Filip’echeva, Y.A.; Kamnev, A.A. FTIR spectroscopic study of biofilms formed by the rhizobacterium Azospirillum brasilense Sp245 and its mutant Azospirillum brasilense Sp245. 1610. J. Mol. Struct. 2017, 1140, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Lai, Z.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, X.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, X. The self-adaption capability of microalgal biofilm under different light intensities: Photosynthetic parameters and biofilm microstructures. Algal Res. 2021, 58, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamnev, A.A.; Dyatlova, Y.A.; Kenzhegulov, O.A.; Fedonenko, Y.P.; Evstigneeva, S.S.; Tugarova, A.V. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopic study of biofilms formed by the Rhizobacterium Azospirillum baldaniorum Sp245: Aspects of methodology and matrix composition. Molecules 2023, 28, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Errico, S.; Moggio, M.; Diano, N.; Portaccio, M.; Lepore, M. Different experimental approaches for Fourier-Trasform infrared spectroscopy applications in biology and biotechnology: A selected choice of representative results. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2023, 70, 937–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzinga, E.J.; Huang, J.H.; Chorover, J.; Kretzschmar, R. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy study of the influence of pH and contact time on the adhesion of Shewanella putrefaciens bacterial cells to the surface of hematite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 12848–12855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheeseman, S.; Shaw, Z.L.; Vongsvivut, J.; Crawford, R.J.; Dupont, M.F.; Boyce, K.J.; Gangadoo, S.; Bryant, S.J.; Bryant, G.; Cozzolino, D.; et al. Analysis of pathogenic bacterial and yeast biofilms using the combination of synchrotron ATR-FTIR microspectroscopy and chemometric approaches. Molecules 2021, 26, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, C.Y.; Derek, C.J.C. Biofilm formation of benthic diatoms on commercial polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Algal Res. 2021, 55, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, A.R.; Short, B.; Rowan, L.; Ramage, G.; Rehman, I.U.R.; Short, R.D.; Williams, C. Investigating the chemical pathway to the formation of a single biofilm using infrared spectroscopy. Biofilm 2023, 6, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grdadolnik, J. ATR-FTIR spectroscopy: Its advantages and limitations. Acta Chim. Slov. 2002, 49, 631–642. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, S.; Goodfellow, B.J.; Nunes, A. FTIR spectroscopy in biomedical research: How to get the most out of its potential. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2021, 56, 869–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suci, P.A.; Mittelman, M.W.; Yu, F.P.; Geesey, G.G. Investigation of ciprofloxacin penetration into Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1994, 38, 2125–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadtochenko, V.A.; Rincon, A.G.; Stanca, S.E.; Kiwi, J. Dynamics of E. coli membrane cell peroxidation during TiO2 photocatalysis studied by ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and AFM microscopy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2005, 169, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galichet, A.; Sockalingum, G.D.; Belarbi, A.; Manfait, M. FT-IR spectroscopic analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell walls: Study of an anomalous strain exhibiting a pink-colored cell phenotype. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001, 197, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Ng, T.W.; An, T.; Li, G.; Wang, B.; Wu, D.; Yin Yip, H.; Zhao, H.; Wong, P.K. Interaction between bacterial cell membranes and nano-TiO2 revealed by two-dimensional FT-IR correlation spectroscopy using bacterial ghost as a model cell envelope. Water Res. 2017, 118, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Su, P.; Chen, H.; Qiao, M.; Yang, B.; Xu, Z. Impact of reactive oxygen species on cell activity and structural integrity of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria in electrochemical disinfection system. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeroual, W.; Choisyl, C.; Millot, J.M.; Manfait, M. FT-IR Spectroscopy Investigation of Bacteria -Antibiotic Interactions. In Fifth International Conference on the Spectroscopy of Biological Molecules; Theophanides, I., et al., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: London, UK, 1993; pp. 191–192. [Google Scholar]

- Vrany, J.D.; Stewart, P.S.; Suci, P.A. Comparison of Recalcitrance to Ciprofloxacin and Levofloxacin Exhibited by Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms Displaying Rapid-Transport Characteristics. Antimicrob.-Agents Chemother. 1997, 41, 1352–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suci, P.A.; Siedlecki, K.J.; Palmer, R.J.; White, D.C.; Geesey, G.G. Combined light microscopy and attenuated total reflection Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy for integration of biofilm structure, distribution, and chemistry at solid-liquid interfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 4600–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Patiño, C.P.; Soares, J.M.; Branco, K.C.; Inada, N.M.; Bagnato, V.S. Spectroscopic Identification of Bacteria Resistance to Antibiotics by Means of Absorption of Specific Biochemical Groups and Special Machine Learning Algorithm. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdéz, J.C.; Peral, M.C.; Rachid, M.; Santana, M.; Perdigón, G. Interference of Lactobacillus plantarum with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and in infected burns: The potential use of probiotics in wound treatment. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2005, 11, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.N.; Cabral, M.E.; Noseda, D.; Bosch, A.; Yantorno, O.M.; Valdez, J.C. Antipathogenic properties of Lactobacillus plantarum on Pseudomonas aeruginosa: The potential use of its supernatants in the treatment of infected chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2012, 20, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, T.C.; Nair, N.U. Engineered lactobacilli display anti-biofilm and growth suppressing activities against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. npj Biofilm. Microbiomes 2020, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, G.A.; Kolter, R. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: A genetic analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 28, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghurabi, M.N.A.; Mubarak, T.H.; Judran, A.K.; Hasoon, B.A. Two-Stage Pulsed Laser Ablation for the Production of Ag@TiO2 Core–Shell Nanoparticles with Enhanced Antimicrobial Properties: An In Silico Study. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 10863–10888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasch, P. Spectral pre-processing for biomedical vibrational spectroscopy and microspectroscopic imaging. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2012, 117, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.; Vanga, S.; Ariese, F.; Umapathy, S. Review of multidimensional data processing approaches for Raman and infrared spectroscopy. EPJ Tech. Instrum. 2015, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat, A.; Joye, I.J. Peak Fitting Applied to Fourier Transform Infrared and Raman Spectroscopic Analysis of Proteins. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasper, R.; Dewelle, J.; Kiss, R.; Mijatovic, T.; Goormaghtigh, E. IR spectroscopy as a new tool for evidencing antitumor drug signatures. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Biomembr. 2009, 1788, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfino, I.; Ricciardi, V.; Manti, L.; Lasalvia, M.; Lepore, M. Multivariate analysis of difference Raman spectra of the irradiated nucleus and cytoplasm region of SHSY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. Sensors. 2019, 19, 3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz-Fonfria, V. Infrared difference spectroscopy of proteins: From bands to bonds. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 3466–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Verma, T.; Mukherjee, R.; Ariese, F.; Somasundaram, K.; Umapathy, S. Raman and infra-red microspectroscopy: Towards quantitative evaluation for clinical research by ratiometric analysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 1879–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Su, Q.; Sheng, D.; Zheng, W.; Wang, X. Comparison of red blood cells from gastric cancer patients and healthy persons using FTIR spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct. 2017, 1130, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, V.; Portaccio, M.; Manti, L.; Lepore, M. An FT-IR microspectroscopy ratiometric approach for monitoring X-ray irradiation effects on SH-SY5Y huma neuroblastoma cells. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler-Arango, J.; Figoli, C.; Muraca, G.; Bosch, A.; Brelles-Mariño, G. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix and cells are drastically impacted by gas discharge plasma treatment: A comprehensive model explaining plasma-mediated biofilm eradication. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qadiri, H.M.; Al-Holy, M.A.; Lin, M.; Alami, N.I.; Cavinato, A.G.; Rasco, B.A. Rapid detection and identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Escherichia coli as pure and mixed cultures in bottled drinking water using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and multivariate analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 5749–5754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, H.Y.; Chan, G.K.; Cheung, S.H.; Sun, S.Q.; Fong, W.F. Morphological and chemical changes in the attached cells of Pseudomonas aeruginosa as primary biofilms develop on aluminium and CaF2 plates. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 102, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Ordonez, A.; Mouwen, D.J.M.; Lopez, M.; Prieto, M. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy as a tool to characterize molecular composition and stress response in foodborne pathogenic bacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 2011, 84, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, M.J.; Trevisan, J.; Bassan, P.; Bhargava, R.; Butler, H.J.; Dorling, K.M.; Fielden, P.R.; Fogarty, S.W.; Fullwood, N.J.; Heys, K.A.; et al. Using Fourier Transform IR Spectroscopy to Analyze Biological Materials. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 1771–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ratio | Biomolecular Origin | Indication |

|---|---|---|

| A(1645-1630)/A1540 | Amide I/Amide II | Protein rearrangement (PR) |

| A(1645-1630)/A(2970-2960) | Amide I/CH3 s. ν | Proteins/lipid content (P/L) |

| A(1645-1630)/A(1085-1090) | Amide I/PO2− s. ν | Proteins/DNA content (P/D) |

| A2925/A(2970-2960) | CH2 as. ν/CH3 s. ν | Lipid saturation (LS) |

| A(1085-1090)/A1050 | PO2− s. ν/C-OH ν | DNA/Carbohydrate content (D/C) |

| A(1085-1090)/A(2970-2960) | PO2− s. ν/CH3 s. ν | Protein phosphorylation (PP) |

| Peak Position (cm−1) | Assignments | Description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa Biofilm | P. aeruginosa Biofilm + Antibiotic Treatment | P. aeruginosa Biofilm + Antibiotic and Probiotic Treatment | |||

| 3531 | 3511 | 3560 | ν (O-H) | polysaccharides | |

| 3380 | 3380 | 3422 | ν (O-H) | polysaccharides | |

| 3280 | 3280 | 3280 | ν (O-H) and ν (N-H) | polysaccharides and Amide A protein | |

| 3191 | ν (N-H) | Amide A protein | |||

| 3060 | 3070 | ν (=C-H) | Unsaturated fatty acid | ||

| 2960 | 2970 | 2970 | νas (C-H) | CH3 of fatty acid chains | |

| 2925 | 2925 | 2930 | νas (C-H) | CH2 in fatty acid chains | |

| 2875 | 2869 | 2884 | νs (C-H) | CH3 of fatty acid chains | |

| 2855 | 2855 | νs (C-H) | CH2 in fatty acid chains | ||

| 1713 | >ν (C = O) | phospholipids | |||

| 1695 1678 1657 1645 1630 1607 | 1689 1660 1645 | 1694 1675 1658 1645 1626 | ν (C=O) and δ (C-N) | Antiparallel b-sheets b-turn a-helix Unordered Parallel b-sheets | Amide I protein |

| 1585 | 1573 | C=N | adenine | ||

| 1552 1540 1528 1514 1497 | 1540 1524 1513 1500 | 1540 | δ (N-H) and ν (C-N) | Amide II protein | |

| 1464 | δ (C-H) | CH2 and CH3 | |||

| 1450 | 1450 | 1453 | δ (C-H) | CH2 and CH3 | |

| 1436 | δ (C-H) | CH2 and CH3 | |||

| 1400 | 1400 1388 | 1400 | ν (C-O-H) | polysaccharides | |

| 1120 | 1135 | ν (C-O) | |||

| 1084 | 1090 | 1084 | νs (PO2−) | nucleic acids and phospholipids | |

| 1050 | 1050 | 1050 | ν (C-OH) | polysaccharides | |

| 1019 | 1025 | ν (C-O) | |||

| 965 | 973 | δ (C-H) | DNA backbone | ||

| 932 915 890 860 | 880 | δ (C–OH) | DNA contributions | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Portaccio, M.; Fusco, A.; Amaro, S.; Donnarumma, G.; Lepore, M. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy Analysis of Biochemical Alterations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms Following Antibiotic and Probiotic Treatments. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010482

Portaccio M, Fusco A, Amaro S, Donnarumma G, Lepore M. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy Analysis of Biochemical Alterations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms Following Antibiotic and Probiotic Treatments. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):482. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010482

Chicago/Turabian StylePortaccio, Marianna, Alessandra Fusco, Sofia Amaro, Giovanna Donnarumma, and Maria Lepore. 2026. "ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy Analysis of Biochemical Alterations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms Following Antibiotic and Probiotic Treatments" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010482

APA StylePortaccio, M., Fusco, A., Amaro, S., Donnarumma, G., & Lepore, M. (2026). ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy Analysis of Biochemical Alterations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms Following Antibiotic and Probiotic Treatments. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010482