Psychotropic Medicinal Plant Use in Oncology: A Dual-Cohort Analysis and Its Implications for Anesthesia and Perioperative Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Survey Development

2.2. Study Population and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

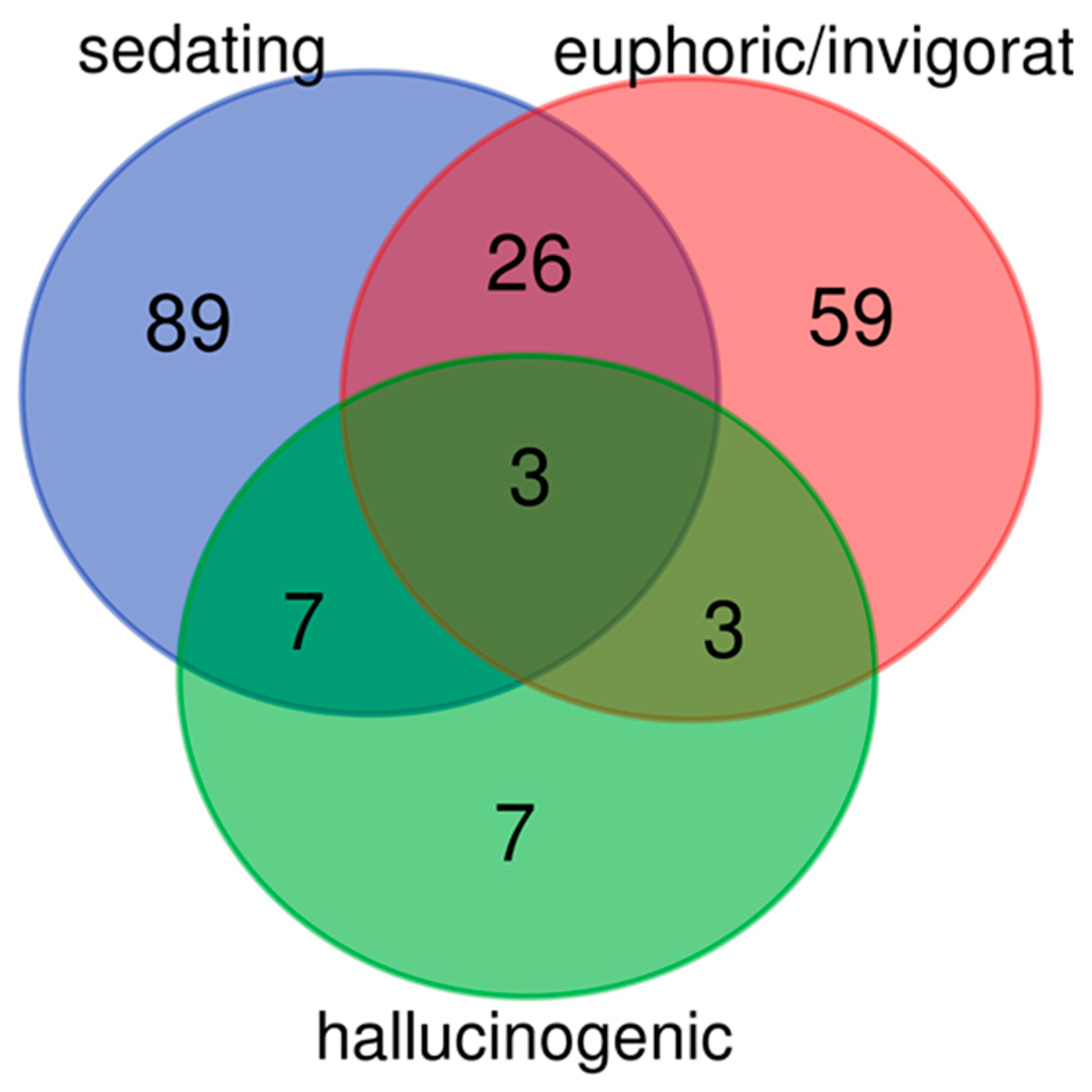

3.1. Systematic Literature Screening of Psychotropic Medicinal Plants

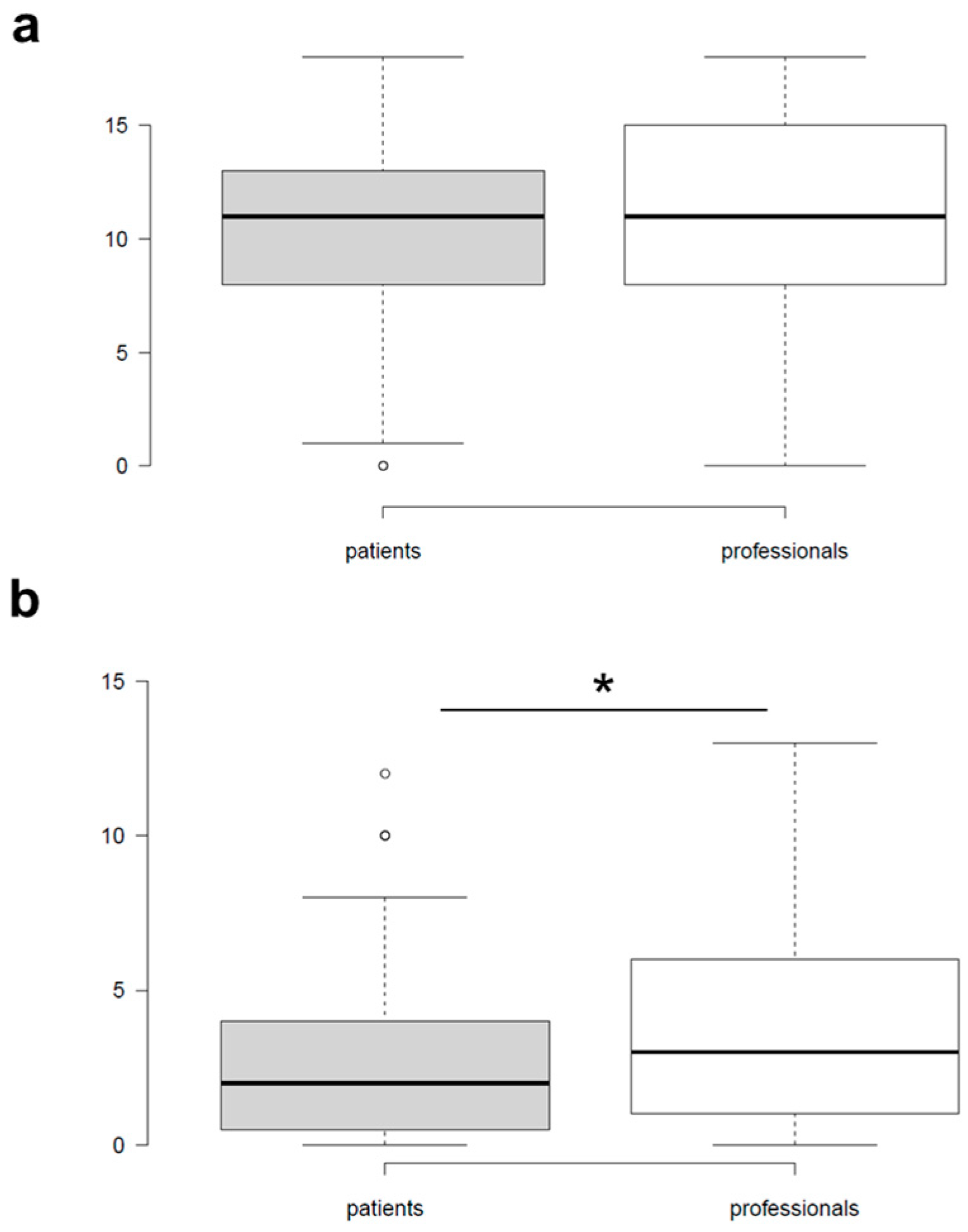

3.2. Cohort Characteristics and Overall Comparison of Plant Knowledge and Use

3.3. Patterns of Plant Knowledge and Use Among Patients and Professionals

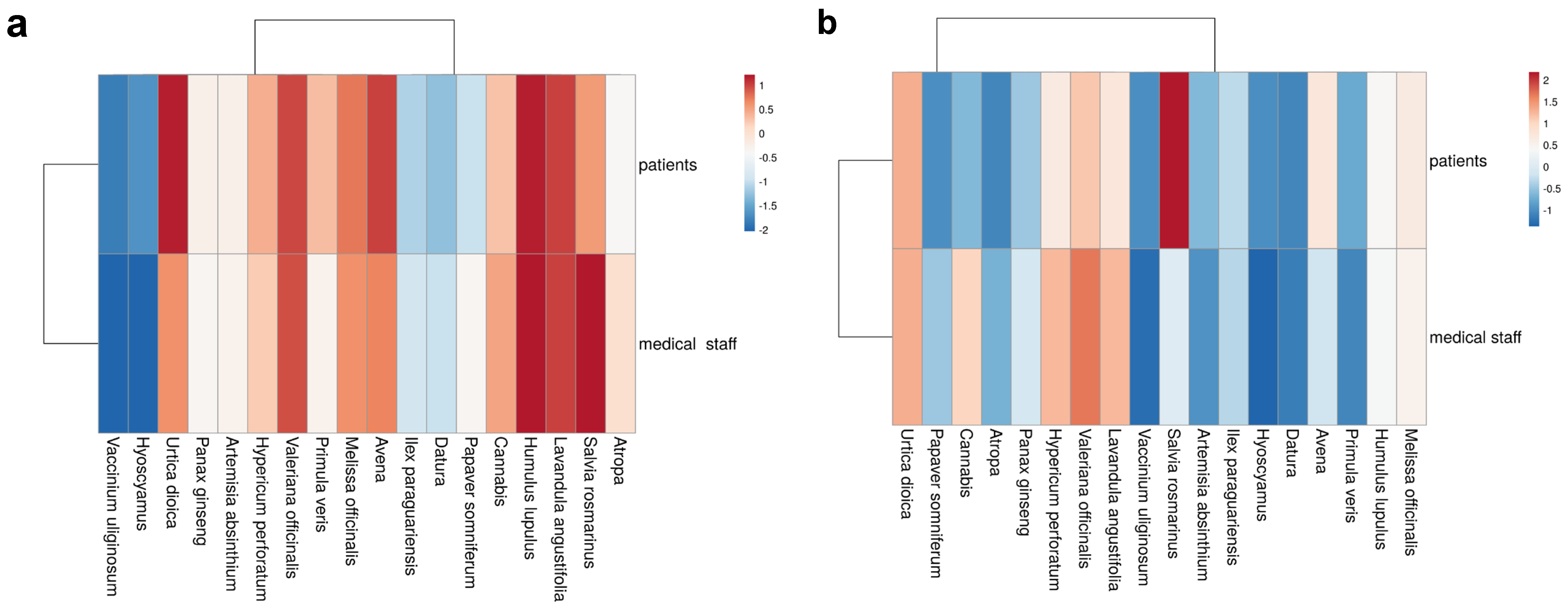

3.4. Cluster Visualization of Knowledge and Use Profiles

3.5. Subgroup Analyses by Tumor Entity and Gender

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAM | Complementary and alternative medicine |

| GCP | Good Clinical Practice |

| HNC | Head and neck cancer |

| SD | Standard deviation |

Appendix A

| Name der Pflanze | Ja, Ich Kenne Die Pflanze | Ja, Ich Nutze Diese Pflanze |

| Baldrian | ||

| Hopfen | ||

| Lavendel | ||

| Melisse | ||

| Schlüsselblume | ||

| Johanniskraut | ||

| Rosmarin | ||

| Wermut | ||

| Ginseng | ||

| Mate | ||

| Brennnessel | ||

| Hafer | ||

| Tollkirsche | ||

| Stechapfel | ||

| Bilsenkraut | ||

| Hanf | ||

| Rauschbeere | ||

| Schlafmohn |

| Plant Name | Yes, I Know This Plant. | Yes, I Use This Plant. |

| Valeriana officinalis L. | ||

| Humulus lupulus L. | ||

| Lavandula angustifolia Mil L. | ||

| Melissa officinalis L. | ||

| Primula veris L. | ||

| Hypericum perforatum L. | ||

| Salvia rosmarinus Spenn. | ||

| Artemisia absinthium L. | ||

| Panax ginseng C. A. Mey. | ||

| Ilex paraguariensis A. St.—HiL. | ||

| Urtica spp. | ||

| Avena spp. | ||

| Atropa belladonna L. | ||

| Datura spp. | ||

| Hyoscyamus sp. | ||

| Cannabis sp. | ||

| Vaccinium uliginosum L. | ||

| Papaver somniferum L. |

References

- Molassiotis, A.; Fernández-Ortega, P.; Pud, D.; Ozden, G.; Scott, J.A.; Panteli, V.; Margulies, A.; Browall, M.; Magri, M.; Selvekerova, S.; et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: A European survey. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, J.; Micke, O.; Muecke, R.; Buentzel, J.; Prott, F.J.; Kleeberg, U.; Senf, B.; Muenstedt, K. User rate of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) of patients visiting a counseling facility for CAM of a German comprehensive cancer center. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 943–948. [Google Scholar]

- Ritschel, M.-L.; Hübner, J.; Wurm-Kuczera, R.; Büntzel, J. Phytotherapy known and applied by head-neck cancer patients and medical students to treat oral discomfort in Germany: An observational study. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 149, 2057–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buentzel, S.K.; Huebner, J.; Buentzel, J.; Micke, O. Medicinal Plants Used for Abdominal Discomfort—Information from Cancer Patients and Medical Students. In Vivo 2022, 36, 2422–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.P.J.G.; Rachow, T.; Ernst, T.; Hochhaus, A.; Zomorodbakhsch, B.; Foller, S.; Rengsberger, M.; Hartmann, M.; Hübner, J. Interactions in cancer treatment considering cancer therapy, concomitant medications, food, herbal medicine and other supplements. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 148, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elvir Lazo, O.L.; White, P.F.; Lee, C.; Cruz Eng, H.; Matin, J.M.; Lin, C.; Del Cid, F.; Yumul, R. Use of herbal medication in the perioperative period: Potential adverse drug interactions. J. Clin. Anesth. 2024, 95, 111473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irún, L.N.; Gras, A.; Parada, M.; Garnatje, T. Plants and mental disorders: The case of Catalan linguistic area. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1256225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, C.A.; Livne, O.; Shmulewitz, D.; Stohl, M.; Hasin, D.S. Use of plant-based hallucinogens and dissociative agents: U.S. Time Trends, 2002–2019. Addict. Behav. Rep. 2022, 16, 100454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.L.; Oh, B.; Butow, P.N.; Mullan, B.A.; Clarke, S. Cancer patient disclosure and patient-doctor communication of complementary and alternative medicine use: A systematic review. Oncologist 2012, 17, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubowitz, J.A.; Sloan, E.K.; Riedel, B.J. Implicating anaesthesia and the perioperative period in cancer recurrence and metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2018, 35, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsalu, T.; Vilo, J. ClustVis: A web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W566–W570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, J.D.; Leder, M. Procedural sedation: A review of sedative agents, monitoring, and management of complications. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2011, 5, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotiby, A.; Alshareef, M. Comparison Between Healthcare Professionals and the General Population on Parameters Related to Natural Remedies Used During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 3523–3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rensburg, R.; Razlog, R.; Pellow, J. Knowledge and attitudes towards complementary medicine by nursing students at a University in South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid 2020, 25, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büntzel, S.K.; Ritschel, M.-L.; Wurm-Kuczera, R.; Büntzel, J. Indications of medical plants: What do medical students in Germany know? A cross-sectional study. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 148, 3175–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planta, M.; Gundersen, B.; Petitt, J.C. Prevalence of the use of herbal products in a low-income population. Fam. Med. 2000, 32, 252–257. [Google Scholar]

- Welz, A.N.; Emberger-Klein, A.; Menrad, K. The importance of herbal medicine use in the German health-care system: Prevalence, usage pattern, and influencing factors. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashrash, M.; Schommer, J.C.; Brown, L.M. Prevalence and Predictors of Herbal Medicine Use Among Adults in the United States. J. Patient Exp. 2017, 4, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tautz, E.; Momm, F.; Hasenburg, A.; Guethlin, C. Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in breast cancer patients and their experiences: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Cancer 2012, 48, 3133–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.L.; Richards, N.; Harrison, J.; Barnes, J. Prevalence of Use of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the General Population: A Systematic Review of National Studies Published from 2010 to 2019. Drug Saf. 2022, 45, 713–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang-Lee, M.K.; Moss, J.; Yuan, C.S. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA 2001, 286, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.oegari.at/web_files/cms_daten/empfehlung_evaluation_erwachsener_patienten_vor_elektiven_eingriffen_dgai_dgch_dgim.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

| Title | Category |

|---|---|

| Bäumler Siegfried. Heilpflanzenpraxis heute—Arzneipflanzenporträts: Heilpflanzenpraxis heute—Arzneipflanzenporträts. Elsevier Health Sciences 2021. | professional |

| Heilpflanzen: Erkennen sammeln und anwenden. Neuer Kaiser 2013. | traditional |

| Hirsch Siegrid und Wolf Ruzicka. Die Kräuter in meinem Garten: 500 Heilpflanzen 2000 | traditional |

| Huber Roman. Mind-Maps Phytotherapie. 2. aktualisierte Edition. Thieme 2019. | professional |

| Mayer Johannes Gottfried Bernhard Uehleke und Pater Kilian Saum. Das große Buch der Klosterheilkunde. 1. Aufl. ZS Verlag Zabert Sandmann GmbH 2013. | traditional |

| Pahlow Apotheker M. Das große Buch der HEILPFLANZEN. Weltbild 2000. | interested layman |

| Schönfelder Peter und Ingrid Schönfelder. Der Kosmos Heilpflanzenführer: Über 600 Heil- und Giftpflanzen Europas. 4. Aufl. With Marianne Golte-Bechtle und Wolfgang Lang. Franckh Kosmos Verlag 2019. | interested layman |

| Steigerwald Petra-Angela. Phytotherapie pocket. 3. Aufl. Börm Bruckmeier 2015. | professional |

| Stumpf Ursula. Unsere Heilkräuter: bestimmen und anwenden. 3. Aufl. Kosmos 2021. | interested layman |

| Indication(s) | N (Plants) | Plants |

|---|---|---|

| Euphoric/invigorating, hallucinogenic, sedating | 3 | Cannabis, Dryas_octopetala, Hyoscyamus |

| Euphoric/invigorating, sedating | 26 | Acorus, Actaea_racemosa, Aloysia_citrodora, Alpinia_officinarum, Angelica, Apium, Artemisia_abrotanum, Artemisia_vulgaris, Avena, Borago_officinalis, Centaurium, Cola, Crataegus, Curcuma_longa, Dictamnus, Fragaria_vesca, Ginkgo_biloba, Hypericum, Jasminum_officinale, Ocimum_basilicum, Origanum_majorana, Piper_methysticum, Rhodiola_rosea, Thymus_serpyllum, Veronica_beccabunga, Vitex_agnus-castus |

| Hallucinogenic, sedating | 7 | Arum, Atropa, Claviceps_purpure, Conium_maculatum, Corydalis_cava, Datura, Solanum_nigrum |

| Euphoric/invigorating, hallucinogenic | 3 | Artemisia_absinthium, Nicotiana_tabacum, Veratrum_album |

| Sedating | 89 | Abies, Achillea_millefolium, Adonis, Ajuga_reptans, Althaea_officinalis, Anagallis_arvensis, Anethum_graveolens, Argentina_anserina, Ballota_nigra, Bellis_perennis, Berberis_vulgaris, Bistorta_officinalis, Boswellia, Calendula_officinalis, Centranthus_ruber, Chelidonium, Cicuta_virosa, Cinchona, Citrus_x_aurantium, Convallaria_majalis, Coriandrum_sativum, Crocus_sativus, Cuminum_cyminum, Cyamopsis_tetragonoloba, Cytisus_scoparius, Drosera, Eschscholzia_californica, Fagopyrum, Foeniculum_vulgare, Fumaria, Galium_odoratum, Gynostemma_pentaphyllum, Helianthus_annuus, Helleborus, Humulus, Hydrocotyle, Lamium, Lavandula_angustifolia, Leonurus_cardiaca, Leptospermum_scoparium, Leucanthemum_vulgare, Lobelia, Lotus, Lycopus, Mandragora, Marrubium, Matricaria_recutita, Melissa_officinalis, Melittis, Mentha_arvensis, Mentha_x_piperita, Meum_athamanticum, Monarda, Morus, Scutellaria, Myrtus_communis, Nardostachys, Nepeta_cataria, Nymphaea_alba, Oenothera, Paeonia, Papaver, Papaver_rhoeas, Parnassia, Passiflora, Peumus_boldus, Pilocarpus_pennatifolius, Piscidia_piscipula, Platycodon_grandifloras, Primula_veris, Rauwolvia, Rheum_rhaponticum, Rhus_coriaria, Salix, Salvia_fruticosa, Sambucus, Sedum, Simaroubaceae, Solidago_canadensis, Syzygium_aromaticum, Tagetes Tanacetum_parthenium, Thalictrum, Tilia, Valeriana_officinalis, Verbena_officinalis, Veronica_officinalis, Zea_mays, Zingiber_officinale |

| Euphoric/invigorating | 59 | Allium_cepa, Allium_sativum, Allium_schoenoprasum, Allium_ursinum, Anchusa_officinalis, Armoracia_rusticana, Arnica_montana, Artemisia_umbelliformis, Betonica_officinalis, Camellia_sinensis, Carlina_acaulis, Cichorium_intybus Cinnamomum_camphora, Cochlearia_officinalis, Cupressus, Daucus_carota, Elettaria_cardamomum, Eleutherococcus_senticosus, Ephedra, Erica, Galanthus, Geum_urbanum, Glycine_max, Hippopha_rhamnoides, Hyssopus_officinalis, Illicium_verum, Juglans_regia, Linum, Lycium_barbarum, Mentha, Mercurialis_perennis, Myosotis, Myristica_fragrans, Panax_ginseng, Panicum_miliaceum, Paullinia_cupana, Petasites, Peucedanum_ostruthium, Piper_nirgum, Polygala, Pulsatilla, Punica_granatum, Rosa_corymbifera, Ruta_graveolens, Saliva_officinalis, Salvia_rosmarinus, Salvia_sclarea, Satureja, Serenoa_repens, Sium_sisarum, Solanum_lycopersicum, Syzygium_cumini, Taraxacum, Theobroma_cacao, Thuja, Thymus_officinalis, Urtica, Valeriana_celtica, Vitis_vinifera |

| Hallucinogenic | 7 | Brugmansia, Lactuca_virosa, Papaver_somniferum, Phalaris_canariensis, Sassafras_albidum, Scopolia_carniolica, Vaccinium_uliginosum |

| Patients | |

|---|---|

| Age [years] +/− SD | 65.18 +/− 11.85 |

| Male | 64/123 (52.03%) |

| Female | 59/123 (47.97%) |

| Cancer Entity | |

| Breast cancer | 33/123 (26.83%) |

| Lung cancer | 8/123 (6.50%) |

| Head and neck cancer | 32/123 (26.02%) |

| Uro-oncology | 17/123 (13.82%) |

| Others | 21/123 (17.07%) |

| >1 cancer entity | 5/123 (4.07%) |

| No information | 7/123 (5.69%) |

| Health care professionals | |

| Age [years] +/− SD | 41.83 +/− 10.65 |

| Male | 30/109 (27.52%) |

| Female | 72/109 (66.06%) |

| No information | 7/109 (6.42%) |

| Physician | 27/109 (24.77%) |

| Nurse | 67/109 (61.47%) |

| Others | 2/109 (1.83%) |

| No information | 13 (11.93%) |

| Knowledge | Usage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Professionals | Patients | Professionals | |

| Artemisia absinthium L. | 52.85% | 57.80% | 6.50% | 8.26% |

| Atropa belladonna L. | 49.59% | 62.39% | 0.81% | 11.93% |

| Avena spp. | 85.37% | 71.56% | 23.58% | 18.35% |

| Cannabis spp. | 66.67% | 68.81% | 6.50% | 33.94% |

| Datura spp. | 26.02% | 47.71% | 0.81% | 5.50% |

| Humulus lupulus L. | 90.24% | 78.90% | 20.33% | 25.69% |

| Hyoscyamus spp. | 16.26% | 33.03% | 1.63% | 2.75% |

| Hypericum perforatum L. | 70.73% | 65.14% | 22.76% | 36.70% |

| Ilex paraguariensis A. St.—HiL. | 30.08% | 48.62% | 10.57% | 16.51% |

| Lavandula angustifolia MilL. | 85.37% | 76.15% | 23.58% | 36.70% |

| Melissa officinalis L. | 78.86% | 70.64% | 22.76% | 27.52% |

| Panax ginseng C. A. Mey. | 52.85% | 56.88% | 8.94% | 19.27% |

| Papaver somniferum L. | 34.15% | 56.88% | 1.63% | 14.68% |

| Primula veris L. | 67.48% | 57.80% | 4.88% | 6.42% |

| Salvia rosmarinus Spenn. | 73.98% | 78.90% | 42.28% | 21.10% |

| Urtica spp. | 90.24% | 70.64% | 30.89% | 37.61% |

| Vaccinium uliginosum L. | 12.20% | 33.03% | 2.44% | 3.67% |

| Valeriana officinalis L. | 84.55% | 75.23% | 29.27% | 42.20% |

| Knowledge | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| breast | 11 | 0 | 18 |

| HNC | 11 | 4 | 18 |

| uro-oncology | 9 | 2 | 17 |

| others | 10 | 0 | 18 |

| Usage | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

| breast | 3 | 0 | 8 |

| HNC | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| uro-uncology | 1 | 0 | 12 |

| others | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| Knowledge | Breast | HNC | Uro-Oncology | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| breast | 0.7279 | 0.2801 | 0.9761 | |

| HNC | 0.7279 | 0.1471 | 0.8572 | |

| uro-oncology | 0.2801 | 0.1471 | 0.2543 | |

| others | 0.9761 | 0.8572 | 0.2543 | |

| Usage | Breast | HNC | Uro-Oncology | Others |

| breast | 0.6312 | 0.0588 | 0.0096 | |

| HNC | 0.6312 | 0.0264 | 0.0025 | |

| uro-oncology | 0.0588 | 0.0264 | 0.6892 | |

| others | 0.0096 | 0.0025 | 0.6892 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wolff, A.; Hübner, J.; Büntzel, J.; Büntzel, J. Psychotropic Medicinal Plant Use in Oncology: A Dual-Cohort Analysis and Its Implications for Anesthesia and Perioperative Care. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010481

Wolff A, Hübner J, Büntzel J, Büntzel J. Psychotropic Medicinal Plant Use in Oncology: A Dual-Cohort Analysis and Its Implications for Anesthesia and Perioperative Care. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):481. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010481

Chicago/Turabian StyleWolff, Anika, Jutta Hübner, Jens Büntzel, and Judith Büntzel. 2026. "Psychotropic Medicinal Plant Use in Oncology: A Dual-Cohort Analysis and Its Implications for Anesthesia and Perioperative Care" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010481

APA StyleWolff, A., Hübner, J., Büntzel, J., & Büntzel, J. (2026). Psychotropic Medicinal Plant Use in Oncology: A Dual-Cohort Analysis and Its Implications for Anesthesia and Perioperative Care. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010481