Featured Application

This review of experimental and recommended daily food use aims at providing potential standard references and templates for the design of omnivorous (OMN), lacto-ovo-vegetarian (LOV), and vegan (VEG) diets in healthy adults. To this end, we retrieved experimentally determined (EXP) data on dietary daily food use, as well as recommended (REC) dietary targets, provided by western countries (Europe and USA) in 1998–2024. By analyzing and combining the data derived from these two sources, we develop potential templates for standard OMN, LOV, and VEG diets at the ≈2200 kcal/day level in a healthy adult subject, useful in the in silico design of diets. The most relevant differences among OMN, LOV, and VEG diets are presented and discussed.

Abstract

Background: In silico diet design may represent a flexible approach in diet planning and adaptation to a variety of conditions, and it may take advantage from standard diet(s) as reference template(s). The concept of standard diet(s) is, however, quite vague and poorly defined. Objective: The aim of this work was to develop templates of omnivorous (OMN), lacto-ovo-vegetarian (LOV), and vegan (VEG) standard diets, based on data produced in European countries and the USA in 1998–2024, and adapted to an adult subject requiring ≈2200 kcal/day. Design: Online databases were used to identify papers containing experimentally determined (EXP) data of daily food frequencies, or reporting dietary recommendations (REC) from (inter)national agencies or specific studies. Only sources reporting quantitative food data (as g/day) in OMN, LOV, and VEG diets were accepted. Results: Out of >200 publications initially identified, 24 EXP and 20 REC sources complied with the selection criteria. By combining the EXP and REC data within each diet type, total meat intake in OMN diet was 99 ± 36 g/day. Total dairy food in LOV diets (247 ± 107 g/day) tended to be lower (by ≈15%, NS) than in OMN diets (272 ± 100). In VEG diets, total vegetal foods were ≈33% greater than in LOV (p < 0.01), and ≈1-fold greater than in OMN ones (p < 0.00001). Total cereal foods were similar in OMN (272 ± 122) and LOV (264 ± 122) diets, but tended to be ≈20–25% greater in VEG diets (to 326 ± 103, NS). Potato and other starchy foods were not different among the three diets. Legumes and pulses were modestly but insignificantly greater in LOV (55 ± 25) and VEG diets (112 ± 137) than in OMN ones (31 ± 24). Soy products were greater in VEG than in LOV diets. The “nuts, seeds, and spreads” food group in VEG diets was ≈3-fold greater than in OMN (p < 0.0005), and ≈90% greater than in LOV diets (p < 0.002). Fruit intake in VEG diets was ≈14% (p = NS) and ≈ 60% (p < 0.005) greater than in LOV and OMN diets, respectively. Finally, the “protein and energy-rich vegetal alternatives” food group in LOV and VEG diets was ≈5- to ≈6-fold greater than in the OMN diet (p ≤ 0.001). Conclusions: The exclusion of meat, fish, and egg in LOV diets is not compensated by increased dairy foods, rather by more total vegetal foods and protein-rich vegetal alternatives. VEG diets replace animal-derived proteins mainly with nuts, seeds, and spreads, soy products and protein-rich vegetal alternatives. On the basis of these data, templates to design “standard” OMN, LOV, and VEG diets are proposed.

1. Introduction

There is a growing interest in diet planning, both from the nutritional and the environmental standpoint [1,2,3,4]. The impact of diet on health, the impact of the food production system on the environment, and the need to optimize food production in respect of the nutritional needs of a steadily growing human population, are only some fields where diet planning is relevant [5,6,7].

In any diet-development process, a new diet may need to be compared with a reference, standard diet, in order to highlight its specific characteristics and properties. Nevertheless, the definition of a standard (i.e., “typical”, or “reference”, or “sample”), healthy diet is a common, although somehow overlooked, issue [8]. The heterogeneity among diet types, food preferences, and day-to-day variations in food intake across the world populations as well as in the same individual [9,10] is indeed tremendous, making the definition of a standard diet a sort of oxymoron. On the other hand, such a heterogeneity hampers the identification of a reference diet type, at least as a proxy, to be used as a possible reference in any diet planning process [11,12]. These issues are obviously shared by in silico diet planning too.

A sound, accepted methodology is therefore mandatory in the attempt to design any standard diet, and some a priori prerequisites are required, to avoid authors’ subjectivity and potential bias at the core. To this end, several methods and data sources are available and could be tested. One could be the use of existing, objective epidemiological data of food consumption in specific population samples. Another could be represented by widely accepted nutritional endpoints, combined with a realistic evaluation of their applicability in everyday life. Another could be based on guidelines released by official, recognized institutions and/or peer-reviewed publications, in respect of daily food consumption. Guidelines, in turn, are usually based on previously collected objective data of type and frequency of food use, in order to be either harmonized with, or directed to, people’s customs. Associations between any of these sources could thus provide a realistic base for the in silico design of a hypothetical, desired reference diet.

In this paper, we retrieved published experimental data on daily food consumption of omnivorous (OMN), lacto-ovo-vegetarian (LOV), and vegan (VEG) diets, and we combined them with nutritional recommendation targets. We focused our data search on western countries, predominantly European countries, and the USA, published in approximately the last 25 yrs. We selected only sources providing quantitative data (in either gram or liter) of each food.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Food Classification

Common foods were operationally divided into three major categories: animal foods, plant foods, and other foods and drinks, each of them further divided into sub-categories.

2.1.1. Animal Foods

The animal foods group included meat, fish, egg, dairy foods, and fat of animal origin. Meat was further divided into the subcategories of bovine, pork, poultry (i.e., “white”), and processed meat. Dairy foods were divided into milk and yogurt, ricotta, and cheese (including both low- and high-fat cheese, i.e., containing either <25% or >25% fat, w/w, respectively).

2.1.2. Plant Foods

The plant foods group included the following:

- (a)

- Starch-rich foods, such as cereals in general, bread and bread substitutes (breadsticks), breakfast cereals, flours, pasta and rice, potato, other tubers, and quinoa);

- (b)

- Vegetables in general, potentially subdivided into dark-green, red and orange, and other vegetables, according to the USDA classification (see below);

- (c)

- Legumes/pulses;

- (d)

- Soy and soy-derived products;

- (e)

- Nuts and seeds;

- (f)

- Fruits (both fresh and dehydrated) and fruit juices;

- (g)

- Vegetal/plant fat;

- (h)

- Alcoholic beverages.

2.1.3. Other Foods and Drinks

This category included salty snacks, sweets and sugars, coffee and tea, and non-alcoholic and alcoholic beverages (wine and beer).

2.2. Diet Design and Data Search Criteria

2.2.1. Data Search Criteria

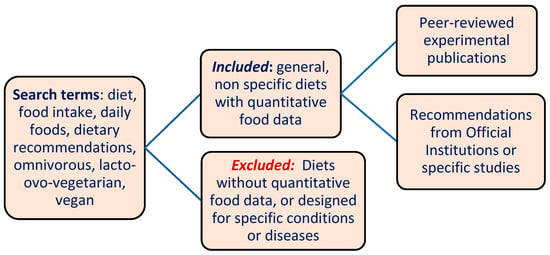

The criteria employed in the data search were the following (see also Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of dietary data retrieval.

- We consulted freely accessible databases (Google & Google scholar and search, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA; Pubmed, a resource of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), Bethesda, ML, USA), to retrieve open-access publications on peer-reviewed experimental data and on recommendations from institutional agencies;

- We selected data referring to healthy subjects only (i.e., by excluding those recommended in known disease), of both sexes, in representative samples of the general population(s), and referring to European countries and the USA;

- We excluded studies reporting food data of diets designed for specific physiological conditions (i.e., exercise, pregnancy, food allergies, age classes), or those either testing the effects of specific diet modifications (i.e., changing the ratio between CHO and fat, etc.), targeted to lifestyle modifications (i.e., physical activity), or aimed at the modulation of specific parameters (such as the intentional reduction in total calories);

- We included only sources reporting quantitative food data;

- We selected data produced in approximately the last 25 yrs;

- We used searching terms like diet, food intake, daily foods, dietary recommendations or guidelines, omnivorous, lacto-ovo-vegetarian, vegan, associated with specific countries.

On the basis of the above-listed constraints, we retrieved data about omnivorous (OMN), lacto-ovo-vegetarian (LOV), and vegan (VEG) diet type, referred to a “standard” adult human subject (of ≈70–75 kg BW), consuming a ≈2.200 kcal diet daily.

2.2.2. Omnivorous (OMN) Diets

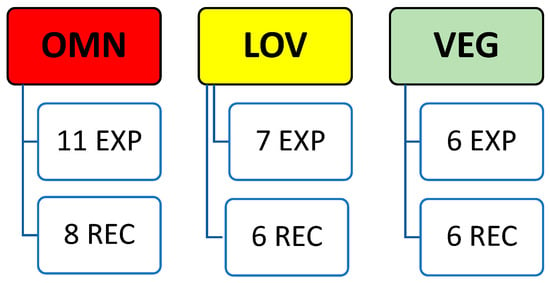

The OMN diet matrix was based on eleven experimental studies, combined with eight recommendations from institutional agencies or research groups, as reported in detail in Supplementary Table S1A,B.

Experimental (EXP) OMN Studies

We identified eleven experimental population studies conducted in seven European countries: the Czech Republic, Denmark, and France (all reported by Mertens et al. [13]), Greece [14], Italy (three studies) [15,16,17], Sweden [18,19], the Netherlands [20], and the United Kingdom [21] (Figure 2) (Supplementary Table S1A).

Figure 2.

Diet types and number of retrieved references according to the diet. Legend to the figure: OMN: Omnivorous diet; LOV: Lacto-ovo-vegetarian diet; VEG: Vegan diet. Exp: Experimental data; Rec: Recommendation data.

There were some disparities in food data reporting among these sources, i.e., not all studies reported data on each of the selected foods or food groups. Furthermore, the quantification of food intake lacked uniformity: gram (g) is the primary unit in most studies; cup is used in some studies with approximate conversions (1 cup of solid food ≈ 200 g; 1 cup of liquid ≈ 240 mL); ounces (oz) occasionally used (with the conversion of 1 oz ≈ 28.34 g). Such a variation in measurement units represented challenges in the direct comparisons between studies and necessitated careful conversion for consistent analysis. Details of the food quantitative data transformation are reported in the footnotes to the Supplementary Table S1A.

The studies showed broadly similar characteristics in terms of age (reported as either mean or range, where available), sex distribution, caloric intake, and food consumption quantities (Supplementary Table S1A).

Recommendation (REC) OMN Studies

We retrieved the eight nutritional recommendation data from the following countries: Denmark (within the New Nordic Diet, NND, Danish component) [22], France [23,24], Germany [25], Italy [26], the “Nordic” Countries as a group [27], Spain [28], the UK [29], and the US [30], (Figure 2). The analytical data retrieved from these studies are reported in the Supplementary Table S1B.

2.2.3. Lacto-Ovo-Vegetarian LOV Diets

Experimental (EXP) LOV Studies

We searched the literature for experimental data publications reporting detailed descriptions of LOV diets, mainly using the following string: “modeling lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets”. We ended up with >40 initial publications. After exclusions of the sources not compatible with the selection criteria, we retrieved seven experimental EXP-LOV studies reporting data from the following countries: Denmark [31], France [32], Germany [33], Italy [15], Spain [34], Sweden [19], and the UK [21] (Figure 2). The analytical data retrieved from these studies are reported in the Supplementary Table S2A.

Recommendation (REC) LOV Studies

In search for REC-LOV studies, we retrieved six studies performed in the “Nordic” countries [27], the Netherlands [35], and the UK [36], and three in the US [30,37,38]. The analytical data retrieved from these studies are reported in the Supplementary Table S2B.

2.2.4. Vegan (VEG) Diets

The definition of a template of vegan diets suitable to adults proved challenging due to two main factors: (1) Many official institutions have not issued specific recommendation guidelines for vegans; (2) Vegan diet consumers usually declare that they do not use animal foods, whereas they do not report their vegetal food alternatives systematically.

Nevertheless, given these limitations, we also followed for VEG diets the same methodology used for the definition of OMN and LOV diets, i.e., by combining published experimental data with those of the recommendation guidelines.

We retrieved seven EXP-VEG data sets in studies performed in Italy [15]. Sweden [19], France [32], Spain [34], Finland [39], and the US [40]. As for the REC-VEG data set, we retrieved six data sets from studies performed in the UK [21,41], Spain [34], the USA [37], Germany [42], and Italy [43], (Figure 2). The analytical data retrieved from these studies are all reported in the Supplementary Table S3. Meat and fish were usually substituted by “protein-rich foods” (mainly dairy foods, eggs, legumes, soy products, and dried fruits)

Notably, breakfast cereals were not systematically and/or separately reported in most of the OMN, LOV, and VEG diets, except for few sparse data (see Supplementary Tables S1A,B, S2A,B and S3). It is likely that in some instances they might have been included into the “cereal” group. Due to the substantial lack of data, we arbitrarily added to all the diets the same breakfast cereal amounts of 40 g/day (Table 1), matching the European breakfast standard portion, as reported in ref. [44].

Table 1.

Daily intake (in g/day (Mean ± SD) of individual foods and food groups of the three diet types.

2.3. Data Handling and Statistical Analysis

We first calculated the daily average (AVG) intake (expressed as mean ± standard deviation, SD) of foods and of food groups, of OMN, LOV, and VEG diets in their EXP and REC separate reports (See Supplementary Table S1A,B, for OMN diets, Table S2A,B for LOV diets, and Table S3 for VEG diets). Original mean and median data were uniformly averaged. In addition, the EXP and REC data within each diet type were added up, in order to calculate the “Grand Mean” (±SD) of each individual food or food group, to be used in the design of the diets’ templates.

The differences between two data groups were tested using the t-test for unpaired data, while those among three data groups (i.e., in the comparison of selected food and food groups among OMN, LOV, and VEG diets) were tested by means of the One Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), followed by the post hoc Fisher’s test in the head-to-head data comparisons. The Statistica® Software (StatSoft, TIBCO Software Inc, version 7.1, Stanford Research Park, 3303 Hillview Ave, Palo Alto, California, USA) was used. A p value of <0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

3. Results

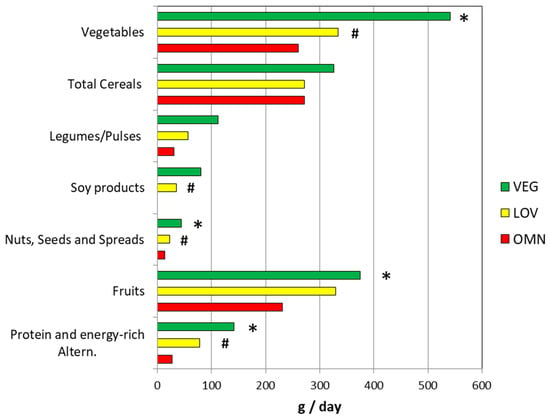

The total caloric intake of OMN (2201 ± 274 kcal/day), LOV (2194 ± 221), and VEG (2270 ± 252) diets was not different among the three diet types. By combining EXP and REC data within each diet type, in LOV diets, total dairy foods (247 ± 107 g/day) were lower (by ≈15%) than those in OMN diets (272 ± 95), albeit not significantly. In VEG diets, total vegetal foods (1526 ± 458) were ≈33% greater than in LOV diets (1199 ± 381, p <0.01) and ≈1-fold greater than that in OMN ones (840 ± 346, p < 0.00001). Total cereal foods were very similar in OMN (272 ± 122) and LOV (264 ± 122), but insignificantly greater (by +20–25%) in VEG diets (326 ± 103). Vegetables in VEG diets (541 ± 324) were greater than in LOV (335 ± 135, p = 0.01) and in OMN diets (260 ± 158, p < 0.0005).

The food group that includes starchy vegetables (potato, other tubers, corn, and quinoa) were not different among VEG (100 ± 55), LOV (94 ± 54) and OMN diets (84 ± 62). Legumes and pulses were modestly albeit insignificantly greater in both LOV (55 ± 25) and VEG diets (112 ± 137) than in OMN ones (31 ± 24). Soy products in OMN diets were not reported as such (being possibly included into the legume group), but reported in both LOV (35 ± 15) and VEG diets 80 ± 23 (p < 0.005 vs. LOV).

The “nuts, seeds, and spreads” food group in VEG diets (44 ± 24) was ≈3-fold greater than in OMN (14 ± 11, p < 0.0005), and ≈90% greater than in LOV diets (23 ± 12, p < 0.002). Total fruits in VEG diets (375 ± 147 g/day) tended to be ≈20% greater than in LOV (317 ± 131, NS), and ≈60% greater (p < 0.005) than in OMN diets (231 ± 123). Fruit intake in VEG diets (375 ± 147 g/day) was ≈14% greater than in LOV (330 ± 122, p = NS) and ≈60% greater than OMN diets (231 ± 123 p < 0.005).

The protein and energy-rich vegetal alternatives as a whole (i.e., the sum of vegetal oil, dairy vegetal substitutes, soy and soy-derived products, and other protein meat alternatives such as gluten and seitan) in VEG diets (132 ± 65) was greater than in both LOV (78 + 52, p < 0.001) and OMN diets (27 + 9, p = 0.00001). LOV diets were >2.5-fold% greater (p = 0.01) than in OMN ones.

The quantitative data of individual food as well as food group intakes are summarized in Table 1. Details about the levels of statistically significant differences are reported in the text.

4. Discussion

The aim of this survey was to construct general templates for the design of omnivorous, lacto-ovo-vegetarian, and vegan “standard” diets, based on available, population-based experimental data, combined with recommendations from (inter)national institutions and specific studies. Although there are several epidemiological data sources reporting food frequencies in peoples’ diets, as well as a number of position papers and recommendations from official agencies about diet design and counseling, to our knowledge, no publication has yet undertaken the complex task of proposing standard diet templates for some popular diet types based on objective data.

We focused our investigation on European countries and the USA. The number of contributions from European countries was consistent, yet not complete or uniform. For instance, many countries did not report either EXP or REC data. Many initially identified sources reported qualitative (i.e., related to nutrients) but not quantitative (i.e., food amounts) data, therefore they were not considered. Furthermore, some reports were not complete about the food list (see the Supplementary Tables S1–S3).

The combination of the two different data sources (EXP and REC) ended up in the definition of comprehensive, balanced food quantities, to be consumed daily by an adult subject of 70–75 kg with moderate (i.e., neither absent nor intensive) physical activity, and requiring a ≈2200 kcal diet. The three templates of OMN, LOV, and VEG diets ended up with a nearly identical daily total caloric intake, as otherwise expected from the search criteria. The mean values of the data could therefore be used for the proposal of a standard diet template of the OMN, LOV, and VEG diets.

The resulting mean values of individual food or food group daily use, obviously do not represent strict and rigid diet templates, as also indicated by the quite ample standard deviations of the data (Table 1). As anticipated in the Section 1, the variety of diets is virtually innumerable, reflecting individual preferences, food availability, tradition, economic issues, etc. Therefore, the “standard” food amounts here calculated for each of the three diet types represent only operational schemes, yet are potentially useful in the process of hypothetical, in silico, diet design.

The two types of data sources used in the templates’ development deserve a comment. While EXP data (i.e., the experimentally based ones) reflect objective data produced within a relatively ample time interval (≥2 decades), the REC (the recommendation ones) are more recent and indicate would-be, desirable targets, that may not actually be followed in everyday life. Therefore, the use of two different data sources reflects mixed models, a choice that can per se be questionable and time-dependent, and may presumably be subjected to modification in the (near) future. Another limitation of our work is that, despite a careful, strenuous investigation of published data through freely accessible databases, using search terms like diet, food intake, average daily diet, etc., we may have involuntarily missed some relevant data. Future studies may fill such a gap and update the data sources.

In regard to daily meat amounts, current trends and official positions suggest a much lower total intake than that here reported (Table 1), particularly that of bovine and pork meat, recommended in ref. [8] as 7 g/day and 7 g/day, respectively, and associated with a similar amount of white meat (29 g/day). The difference between recent trends and our results concerning meat intake might be explained, at least in part, by a time-related model effect, as discussed above. Such a gap indirectly suggests the need to update both the experimental data set to current values, and the recommendation ones, thus aligning them to the latest trends.

We report here which types of foods are, or would be, used in LOV and VEG diets, to replace either the egg and dairy ones in the former, or all animal-derived foods in the latter (see Figure 3 for a visual, quick inspection, and Table 1 for precise numerical data). Our data suggest that, in LOV diets, the exclusion of meat, fish, and egg, is not compensated by a dairy food intake greater than that of OMN diets, rather by more total vegetal foods and protein-rich vegetal alternatives. VEG diets on turn replace animal-derived proteins mainly with vegetables, nuts, seeds, and spreads, soy products and protein-rich vegetal alternatives. Although somehow expected, these general indications may be useful for a better quantitation and titration of the animal-food replacing items in the design of LOV and VEG diets, taking into consideration individual food preferences, food availability, tradition, etc. among different world peoples.

Figure 3.

This figure highlights the daily quantities of vegetal foods and food groups that can substitute the animal-derived foods of OMN diets in LOV and VEG diets. Green bars: VEG data; yellow bars: LOV data; red bars: OMN data. (*): Significant difference (p < 0.01 or less) between VEG from OMN diets. (#) Significant difference (p < 0.05 or less) between VEG and LOV diets (see Section 3 for precise levels of significance. The levels of the statistically significant differences are reported in detail in the text.

5. Conclusions

This overwiew is a synopsis of quantitative food amounts of omnivorous, lacto-ovo-vegetarian, and vegan diets, based on European and US data, adapted to a healthy, adult subject requiring ≈2200 kcal/day. The template(s) resulting from this work may be useful in the theoretical, in silico design of standard OMN, LOV, and VEG diets. Updated data collection and dietary recommendations are necessary to adjust current dietary habits, nutritional recommendations, and governments’ policies to the latest nutritional trends, based on scientific evidence(s) coming from human nutrition research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010257/s1, Table S1: (A) Omnivorous (OMN) Diet composition. Experimental data; (B) Omnivorous (OMN) Diet composition. Recommendation data; Table S2: (A) Lacto-Ovo-Vegetarian (LOV) Diet composition. Experimental data; (B) Lacto-Ovo-Vegetarian (LOV) Diet composition Recommendation data; Table S3: Vegetarian (VEG) Diet composition, of both the Experimental and the Recommendation data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T.; methodology, P.T. and A.L.; software, P.T.; validation, P.T. and A.L.; formal analysis, P.T. and A.L.; investigation, P.T.; resources, P.T. and A.L.; data curation, P.T. and A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T.; writing—review and editing, P.T. and A.L.; funding acquisition, A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript: OMN: omnivorous (diets); LOV: lacto-ovo-vegetarian (diets): VEG: vegan (diets);. Oz: ounce; NS: not statistically significant; AVG: average; SD: standard deviation; mL: milliliter; kcal: kilocalories; ANOVA: one-way analysis of variance.

References

- Cacau, L.T.; De Carli, E.; Martins de Carvalho, A.; Lotufo, P.A.; Moreno, L.A.; Martins Bensenor, I.; Marchioni, D.M. Development and Validation of an Index Based on EAT-Lancet Recommendations: The Planetary Health Diet Index. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Spajic, L.; Clark, M.A.; Poore, J.; Herforth, A.; Webb, P.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. The healthiness and sustainability of national and global food based dietary guidelines: Modelling study. Brit. Med. J. 2020, 370, m2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazac, R.; Hyyrynen, M.; Kaartinen, N.E.; Männistö, S.; Irz, X.; Hyytiäinen, K.; Tuomisto, H.L.; Lombardini, C. Exploring tradeoffs among diet quality and environmental impacts in self-selected diets: A population-based study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 1663–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A.; Finley, J.; Hess, J.M.; Ingram, J.; Miller, G.; Peters, C. Toward Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, K.; Willits-Smith, A.; Rose, D. Popular diets as selected by adults in the United States show wide variation in carbon footprints and diet quality. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 117, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooreman-Algoed, M.; Boone, L.; Dewulf, J.; Nachtergaele, P.; Taelman, S.E.; Lachat, C. Environmental sustainability and nutritional quality of different diets considering nutritional adequacy. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 176967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, H.; Johnston, C.; Wharton, C. Plant-Based Diets: Considerations for Environmental Impact, Protein Quality, and Exercise Performance. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Murray, C.J. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Healthy Diet. 29 April 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Gaby, A. A review of the fundamentals of diet. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2013, 2, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessi, D.S.; McCreery, C.V.; Zomorrodi, A.R. In silico dietary interventions using whole-body metabolic models reveal sex-specific and differential dietary risk profiles for metabolic syndrome. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1586750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A.; Smetana, S.; Heinz, V.; Hertzberg, J. Modeling obesity in complex food systems: Systematic review. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1027147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, E.; Kuijsten, A.; van Zanten, H.H.E.; Kaptijn, G.; Dofková, M.; Mistura, L.; D’Addezio, L.; Turrini, A.; Dubuisson, C.; Havard, S.; et al. Dietary choices and environmental impact in four European countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 1117827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martimianaki, G.; Peppa, E.; Valanou, E.; Papatesta, E.M.; Klinaki, E.; Trichopoulou, A. Today’s Mediterranean Diet in Greece: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Survey—HYDRIA (2013–2014). Nutrients 2022, 14, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, F.; Pellegrini, N.; Vannini, L.; Jeffery, I.B.; La Storia, A.; Laghi, L.; Serrazanetti, D.I.; Di Cagno, R.; Ferrocino, I.; Lazzi, C.; et al. High-level adherence to a Mediterranean diet: Beneficially impacts the gut microbiota and associated metabolome. Gut 2016, 65, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampaoli, S.; Krogh, V.; Grioni, S.; Palmieri, L.; Gulizia, M.M.; Stamler, J.; Vanuzzo, D. Eating behaviours of Italian adults: Results of the osservatorio epidemiologico cardiovascolare/health examination survey. Epidemiol. Prev. 2015, 39, 373–379. [Google Scholar]

- INRAN/SCAI. National Survey on Food Consumption in Italy INRAN-SCAI. ISTAT (National Statistical Institute). 2005–2006. Available online: https://www.crea.gov.it/web/alimenti-e-nutrizione/-/indagine-sui-consumi-ali-mentari (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Adamsson, V.; Reumark, A.; Fredriksson, I.B.; Hammarström, E.; Vessby, B.; Johansson, G.; Risérus, U. Effects of a healthy Nordic diet on cardiovascular risk factors in hypercholesterolaemic subjects: A randomized controlled trial (NORDIET). J. Intern. Med. 2011, 269, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulkerrins, I.; Medin, A.C.; Groufh-Jacobsen, S.; Margerison, C.; Larsson, C. Dietary intake among youth adhering to vegan, lacto-ovo-vegetarian, pescatarian or omnivorous diets in Sweden. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1528252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinnissen, C.S.; Ocké, M.C.; Buurma-Rethans, E.J.M.; van Rossum, C.T.M. Dietary Changes among Adults in The Netherlands in the Period 2007–2010 and 2012–2016. Results from Two Cross-Sectional National Food Consumption Surveys. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, I.; Wood, C.; Syam, N.; Rippin, H.; Dagless, S.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Amoutzopoulos, B.; Steer, T.; Key, T.J.; Papier, K. Assessing Performance of Contemporary Plant-Based Diets against the UK Dietary Guidelines: Findings from the Feeding the Future (FEED) Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithril, C.; Dragsted, L.O.; Meyer, C.; Tetens, I.; Biltoft-Jensen, A.; Astrup, A. Dietary composition and nutrient content of the New Nordic Diet. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 16, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French National Nutrition and Health Program’s Dietary Guidelines. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/france/previous-versions/en/ (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- French National Nutrition and Health Program 2011–2015. Ministry of Health. Available online: https://sante.gouv.fr (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- FAO. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines—Germany. Available online: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/regions/countries/germany/en/ (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- INRAN/CREA. Guidelines for a Healthy Diet (Linee Guida per Una Sana Alimentazione); 2017 Edition. Appendix A, Table A. pp. 1139–1145. Available online: https://www.crea.gov.it/web/alimenti-e-nutrizione/-/linee-guida-per-una-sana-alimentazione-2018 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Blomhoff, R.A.; Rikke, A.; Kristoffer, E.; Christensen, J.J.; Hanna, E.; Erkkola, M.; Gudanaviciene, I.; Halldórsson, Þ.I.; Høyer-Lund, A.; Lemming, E.; et al. Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023: Integrating Environmental Aspects; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-García, S.; Green, R.F.; Scheelbeek, P.F.; Harris, F.; Dangou, A.D. Dietary recommendations in Spain: Affordability and environmental sustainability? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 120125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS UK The Eatwell Guide: 5 A Day Guide. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/Live-well/eat-well/food-guidelines-and-food-labels/the-eatwell-guide/ (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- USDA. Dietary Guidelines Americans 2020–2025. Table 4.1 on Page 96, Chapter 1, and Appendix 1. Available online: https://www.DietaryGuidelines.gov (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Nordman, M.; Lassen, A.D.; Mogensen, L.; Trolle, E. Carbon Footprints of Different Dietary Patterns in Denmark; DTU, National Food Institute: Lyngby, Denmark, 2022; Available online: https://orbit.dtu.dk/en/publications/carbon-footprints-of-different-dietary-patterns-in-denmark/ (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Allès, B.; Baudry, J.; Méjean, C.; Touvier, M.; Péneau, S.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Comparison of Sociodemographic and Nutritional Characteristics between Self-Reported Vegetarians, Vegans, and Meat-Eaters from the NutriNet-Santé Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensink, G.B.; Barbosa, C.L.; Brettschneider, A.-K. Prevalence of persons following a vegetarian diet in Germany. J. Health Monit. 2016, 1, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menal Puey, S.; Morán del Ruste, M.; Marques-Lopes, I. Food and nutrient intake in Spanish vegetarians and vegans. Prog. Nutr. 2018, 20, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, E.; van Rossum, C.; Postma-Smeets, A.; Stafleu, A.; Wolvers, D.; van Dooren, C.; Toxopeus, I.; Buurma-Rethans, E.; Geurts, M.; Ocké, M. Development of healthy and sustainable food-based dietary guidelines for the Netherlands. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2419–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK NHS. The Eatwell Guide. The Vegetarian Diet. Available online: www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/how-to-eat-a-balanced-diet/the-vegetarian-diet/ (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Hess, J.M.; Comeau, M.E.; Swanson, K.; Burbank, M. Modeling Ovo-vegetarian, Lacto-vegetarian, Pescatarian, and Vegan USDA Food Patterns and Assessing Nutrient Adequacy for Lactation among Adult Females. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2023, 7, 102034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAYO Clinic. Nutrition and Healthy Eating. 2023. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-life-style/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/vegetarian-diet/art-20046446 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Elorinne, A.L.; Alfthan, G.; Erlund, I.; Kivimäki, H.; Paju, A.; Salminen, I.; Turpeinen, U.; Voutilainen, S.; Laakso, J. Food and Nutrient Intake and Nutritional Status of Finnish Vegans and Non-Vegetarians. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsen, M.C.; Rogers, G.; Miki, A.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Folta, S.C.; Economos, C.D.; Jacques, P.F.; Livingston, K.A.; McKeown, N.M. Theoretical Food and Nutrient Composition of Whole-Food Plant-Based and Vegan Diets Compared to Current Dietary Recommendations. Nutrients 2019, 11, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK NHS. The Eatwell Guide. 2022. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/how-to-eat-a-balanced-diet/the-vegan-diet/ (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Richter, M.; Boeing, H.; Grünewald-Funk, D.; Heseker, H.; Kroke, A.; Leschik-Bonnet, E.; Oberritter, H.; Strohm, D.; Watzl, B. for the German Nutrition Society (DGE). Vegan Diet. Position of the German Nutrition Society (DGE). Ernahr. Umsch. 2016, 63, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroni, L.; Goggi, S.; Battino, M. VegPlate: A Mediterranean-Based Food Guide for Italian Adult, Pregnant, and Lactating Vegetarians. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 2235–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carruba, M.O.; Ragni, M.; Ruocco, C.; Aliverti, S.; Silano, M.; Amico, A.; Vaccaro, C.M.; Marangoni, F.; Valerio, A.; Poli, A.; et al. Role of Portion Size in the Context of a Healthy, Balanced Diet: A Case Study of European Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.