Abstract

As a significant hydrocarbon-bearing sag in the Zhu I Depression of the Pearl River Mouth Basin, the Lufeng sag has long encountered exploration challenges owing to the dearth of comprehensive investigations on the source-to-sink system of the steep slope zone. To tackle this issue, this research utilizes paleogeomorphic reconstruction techniques to conduct a quantitative source-to-sink analysis and establish a hydrocarbon accumulation pattern in the steep slope zone of ductile deformation zones. The findings indicate that the longitudinal drainage systems developed during the intense rifting stage determine the proximal sedimentation. During the minor rifting stage, the area of the lacustrine basin contracted, and the pre-existing drainage systems converged into axial drainage systems. By the late rifting stage, the extent of the drainage system expands significantly, displaying distal sediment source characteristics. The tectono-geothermal regime governs the spatial scale of the source-to-sink system. Quantitative analysis reveals that the denudation and depositional areas in the ductile deformation zones notably exceed those in the brittle deformation zones, thereby creating favorable conditions for the large-scale development of sand bodies and hydrocarbon accumulation in the steep slope zone. These insights offer crucial guidance for future exploration in the steep slope zones of the fault basin.

1. Introduction

Fault basins, as globally significant hydrocarbon-bearing basins, account for approximately one-third of the world’s total hydrocarbon resources [1]. As hydrocarbon exploration progresses through its various stages, exploration objectives have progressively transitioned to deeper layers and complex steep slope zones [2]. The Lufeng Sag, situated in the eastern part of the Pearl River Mouth Basin, has achieved continuous large-scale oil and gas exploration successes since the 1980s. Currently, it has evolved into one of the core hydrocarbon-producing regions in the Zhu I Depression [3]. Notably, although exploration wells have verified the development of large fan deltas in the steep slope zone, commercial hydrocarbon discoveries in the Lufeng Sag are still concentrated in the slope belt of the subsag and the central anticlinal zone, with urgent breakthroughs needed for exploration in the steep slope zone [4,5]. Previous studies indicate that the Lufeng Sag, a hydrocarbon-rich subsag, contains two sets of Paleogene source rocks with the Wenchang Formation serving as the primary source rock and the Enping Formation as the secondary source rock [6,7]. Multiple secondary subsags have been recognized as potentially hydrocarbon-rich, with favorable sandstone reservoirs that provide a crucial foundation for hydrocarbon accumulation [8,9,10]. However, existing research on source-to-sink systems has primarily focused on static identification through seismic data, lack of discussion regarding the controlling effects of spatiotemporal evolution processes on the development patterns of sandy bodies in steep slope zones from the perspective of prototype basin types and basin-forming mechanisms on the development patterns of sandy bodies in steep slope zones.

To address this issue, integrated analysis and zonal differential characterization of the tectono-sedimentary features of the Lufeng Sag are of particular significance. Based on prototype basin restoration, Zhong Kai et al. proposed that magma underplating and geothermal mechanism differences are the core controlling factors for the strong lateral structural heterogeneity of the Lufeng Sag. Based on variations in geothermal mechanisms as well as structural geometry and kinematic characteristics of the main controlling faults, the steep slope zone can be categorized into ductile and brittle deformation zones. According to Walsh and Watterson (1991), fault connectivity can be classified as either “hard-linked” or “soft-linked” depending on whether fault surfaces are directly connected [11,12,13,14]. The ductile deformation zone typically exhibits soft-linked fault connections, leading to the formation of accommodation zones or transfer slopes [13,14]. This structural adjustment process is accompanied by significant changes in geomorphology, source-to-sink area, and drainage system migration within the steep slope zone [11,15]. This provides new theoretical perspectives for comprehending the development patterns of large-scale sandy bodies and hydrocarbon accumulation models in steep slope zones [16,17].

The steep slope zone of fault-depressed lacustrine basins, characterized by complex geomorphic conditions and frequent tectonic activity, not only facilitates the potential for multi-source sediment input into the lake but also leads to dynamic changes in sediment dispersal processes under such tectonic influences [18,19]. To break through exploration bottlenecks, this study employs paleogeomorphological restoration techniques for a quantitative investigation of source-to-sink systems, relying on multiple modeling software and prototype basin restoration methods. The research objective is to clarify the development patterns of large-scale high-quality reservoirs in steep slope zones and identify the structural areas most favorable for sand body enrichment, thus fundamentally resolving key exploration challenges. By restoring the paleogeomorphic characteristics across different geological periods, this work focuses on analyzing the different controlling factors of source-to-sink systems in various structural zones, providing a scientific basis for in-depth studies on sand body development patterns and hydrocarbon accumulation models. The findings are expected to contribute to theoretical and practical advancements in steep slope zone exploration.

2. Geological Setting

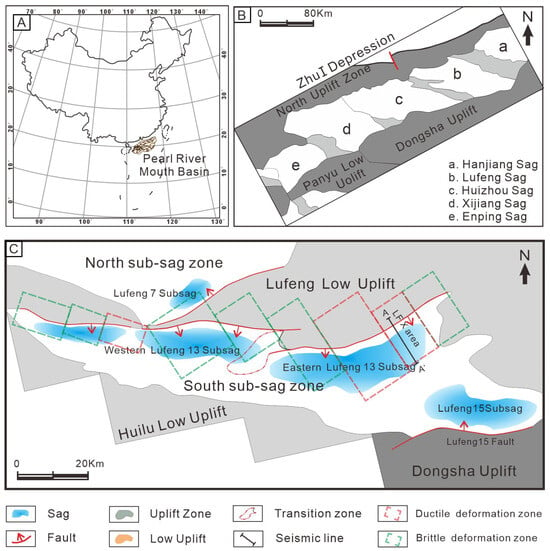

The Pearl River Mouth Basin, a Cenozoic extensional basin situated on the northern passive margin of the South China Sea, displays a NE–SW structural orientation that has been molded by multi-phase tectonic development. Its current structural framework is characterized by a “three uplifts and three sags” pattern. In the northern depression belt, the Zhu I Depression is delimited by NE–NEE trending boundary faults [20,21]. The Lufeng Sag, which is positioned in the northeastern region of the Zhu I Depression, shows structural zonation affected by the evolution of the stress field. During the early stage, NNW-oriented compression led to the formation of NEE-trending structures, whereas the near S-N stress in the late stage gave rise to EW-oriented structural elements. The sag is divided into northern and southern sub-sags by the Lufeng Mid-Low Bulge [22,23,24]. The southern sub-sag has emerged as the primary target for hydrocarbon exploration owing to its more favorable reservoir-seal assemblages [25,26,27] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structural unit division of Lufeng Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin: (A) Location of the Pearl River Mouth Basin in the South China Sea. (B) Internal structural unit of ZhuⅠdepression. (C) Structural unit, deformation zones, and seismic line location in the study area (modified from Wang et al., 2022, and Zhong et al., 2024a,b [16,17,28]).

Integrated geophysical data indicate notable tectonic–thermal coupling in the Lufeng Sag [16,17]. Seismic profiles document multi-phase magmatic underplating within the basement, correlating with anomalous geothermal gradients characterized by bending heat flow isotherms from deep-water to shallow-water domains. These geothermal anomalies align spatially consistent with gravity-magnetic anomaly zones, validating magmatic underplating as a crucial factor driving the geothermal evolution of the basin. Such thermo-tectonic interactions governed structural reactivation and depositional architecture, offering essential dynamics for hydrocarbon generation and migration.

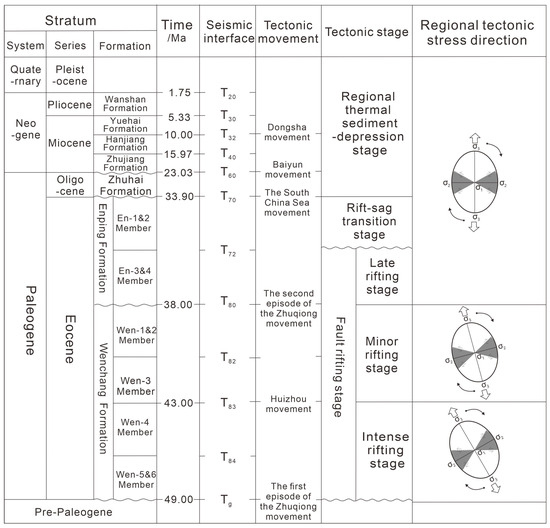

The tectonic evolution of the basin is demarcated by the T72 unconformity into a rifting phase and a post-rift thermal subsidence phase. The rifting phase can be further subdivided into three tectonic stages: the intense rifting stage corresponds to the Zhuqiong I Movement, during which the Lower Wenchang Formation was rapidly deposited; the minor rifting stage coincides with the Huizhou Movement, characterized by the contraction of the lacustrine basin and the reduction in sedimentation in the Upper Wenchang Formation; the late rifting stage is associated with the terminal rifting of the Zhuqiong II Movement, marked by the expansion of deposition in the Lower Enping Formation (Figure 2). In contrast, the post-rift thermal subsidence phase is predominantly characterized by uniform subsidence, resulting in the formation of regional caprocks essential for hydrocarbon preservation [29,30,31,32,33,34].

Figure 2.

Structural–stratigraphic framework of the Lufeng Sag in the Pearl River Mouth Basin (modified from Tang et al., 2023 [35]).

3. Data and Methods

The research on paleogeomorphology commenced in the 1950s and has now been extensively applied [36,37,38,39]. Nevertheless, the reconstruction of paleogeomorphology and paleodrainage systems in the steep slope zones of rift basins remains a pivotal challenge in sedimentological research. Current investigations into “sink” areas primarily concentrate on the static identification of depositional systems, emphasizing parameters such as sink area dimensions and the spatial separation between subsidence centers and sediment sources. Conversely, studies on “source” regions focus on the recognition of continental sediment transport pathways, including paleovalleys, fault-controlled troughs, and transfer zones. However, these methodologies are inherently limited to characterizing the spatial configuration of existing source-to-sink systems, without addressing their dynamic spatiotemporal evolution across geological timescales. Applying the “paleostructure–paleogeomorphology–paleodrainage” (three-paleo) coupling methodology, this study conducts paleogeomorphic reconstruction for six critical third-order sequences within the Wenchang-Enping Formations (T85–T72). This technical system transcends the limitations of traditional static approaches by enabling dynamic simulation of the spatiotemporal evolution of source-to-sink systems in rift basin steep slopes, offering novel insights for predicting sandstone distribution in such complex tectonic settings.

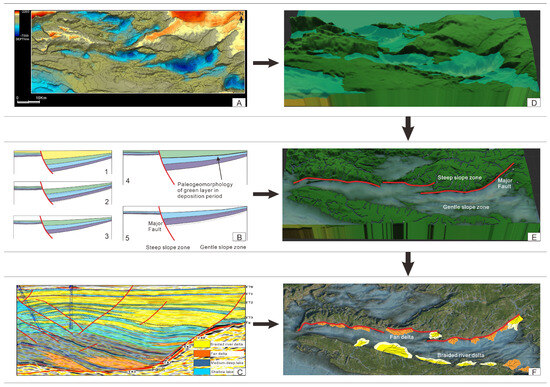

A systematic paleogeomorphic restoration workflow is established, relying on well data and high-resolution 3D seismic datasets provided by the Shenzhen Branch of CNOOC China Limited. The technical framework consists of three integrated phases:

- (1)

- Stratigraphic architecture analysis: 3D seismic interpretation using Petrel software (2018) is utilized to delineate the spatial distribution of progradational bodies and reconstruct the present-day structural framework for each stratigraphic interval (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Schematic diagram of three-paleo (paleostructure–paleogeomorphology–paleodrainage) coupling restoration for paleogeomorphology modeling: (A) Current stratigraphic architecture visualized using Petrel Software. (B) Approach for reconstructing the prototype basin with 3D Move Software: B1. Input data and establish the tectonic model. B2. Conduct decompaction, resulting in a thickness rebound of the underlying strata. B3. Restore faults based on the decompaction results to eliminate the fault influence. B4. Restore folds (i.e., perform layer flattening); B5. Conduct decompaction, fault restoration, and layer flattening layer by layer (modified from Lv et al., 2015; Lv et al., 2018 [40,41]). (C) Identification of the depositional system using Petrel Software. (D–F) 3D visualization framework for the paleogeomorphic reconstruction process implemented via World Machine Software (2.3.6_Professional).

Figure 3. Schematic diagram of three-paleo (paleostructure–paleogeomorphology–paleodrainage) coupling restoration for paleogeomorphology modeling: (A) Current stratigraphic architecture visualized using Petrel Software. (B) Approach for reconstructing the prototype basin with 3D Move Software: B1. Input data and establish the tectonic model. B2. Conduct decompaction, resulting in a thickness rebound of the underlying strata. B3. Restore faults based on the decompaction results to eliminate the fault influence. B4. Restore folds (i.e., perform layer flattening); B5. Conduct decompaction, fault restoration, and layer flattening layer by layer (modified from Lv et al., 2015; Lv et al., 2018 [40,41]). (C) Identification of the depositional system using Petrel Software. (D–F) 3D visualization framework for the paleogeomorphic reconstruction process implemented via World Machine Software (2.3.6_Professional). - (2)

- Reconstruction of prototype basin and paleodrainage: A quintessential modeling method is implemented through MOVE software (2018), incorporating erosion restoration, sedimentary backfilling, fault displacement correction, compaction compensation, and true thickness recovery (Figure 3B).

- (3)

- Restoration of paleogeomorphology: Restored paleostructural surfaces are input into World Machine for topographic modeling, coupling paleostructural patterns with provenance and progradational body parameters to achieve a synergistic characterization of the paleogeomorphic framework (Figure 3C).

Following the acquisition of paleogeomorphic features and source-to-sink developmental characteristics across different periods, quantitative identification of source-to-sink parameters was conducted. The area of the source region can be determined by the channel range obtained through paleogeomorphic restoration, while the extent of the depositional area is identified by defining the boundaries of sedimentary sand bodies using Petrel software. Image processing software has been widely applied in geological studies with high accuracy [42,43,44]. In this study, the Adobe Photoshop Quantification (PSQ) method was employed to quantitatively delineate source-to-sink areas. Specifically, the target regions (individual source or sink units) were selected within Adobe Photoshop, and their pixel counts were recorded. The entire study area was similarly delineated to obtain its total pixel count. Based on the proportional relationship between the area of a target region and its pixel count relative to the total area and total pixel count of the study area, the actual areas of each source-to-sink unit were calculated sequentially. The methodology for estimating drainage length followed a similar principle: by determining the ratio between the actual length of the study area and its corresponding length in the software, combined with the measured length of the river channel within the software, the actual channel length was derived. Additionally, the channel cross-sectional area was determined by identifying the entry point of the river channel into the basin using Petrel software and subsequently calculating its spatial extent.

4. Results

4.1. Reconstruction of Eocene Paleogeomorphology and Source-to-Sink System

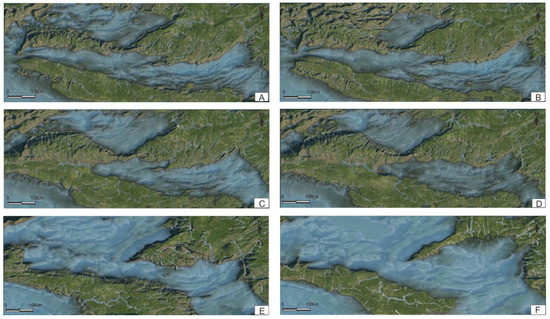

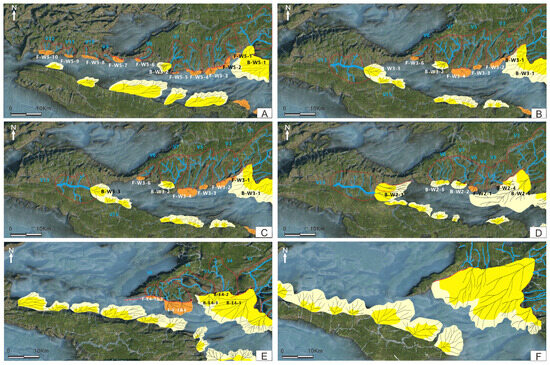

The source-to-sink system comprises three key components: source, transport pathway, and sink. In early international studies, the source-to-sink framework was predominantly applied to passive continental margins, wherein source refers to the terrestrial sediment source area within the continental interior, sink denotes the ultimate depositional zone in deep-water environments, and transport pathway represents transient sediment storage areas along the proximal margin, typically manifested as incised valleys or submarine canyons [45,46,47,48,49]. However, recent investigations by Chinese researchers have demonstrated the applicability of source-to-sink theory to rift basins, where source areas are constrained by boundary fault systems and hinterland uplift zones, transport pathways are dominated by fault-controlled troughs and relay ramps, and sink regions correspond to rapidly subsiding sub-basins or slope-break zones [50,51,52]. This comparative analysis underscores the universality and adaptability of source-to-sink theory across diverse tectonic settings [53,54,55]. Therefore, the source-to-sink approach demonstrates high applicability in the study area. Based on the “paleostructure–paleogeomorphology–paleodrainage” (three-paleo) coupling methodology, paleogeomorphic reconstructions were conducted for six critical third-order sequences within the Eocene (T85–T72) strata. During the intense rifting stage, the lacustrine basin exhibited a relatively large area and significant water depth (Figure 4A,B). In the minor rifting stage, the basin area contracted markedly (Figure 4C,D). By the late rifting stage and the rift-sag transition stage, the lacustrine basin re-expanded (Figure 4E,F). The paleogeomorphic reconstruction result exhibits a well-defined correspondence with the tectonic evolution and sedimentary history of the study area.

Figure 4.

Paleogeomorphological–Paleodrainage evolution of the steep slope zone in the Lufeng Sag during Eocene stratigraphic intervals (T85–T72): (A) Wen-6&5th Member; (B) Wen-4th Member; (C) Wen-3rd Member; (D) Wen-2&1st Member; (E) En-4th Member; (F) En-3rd Member.

The recognition that the provenance of rift basins is predominantly proximal has become a consensus in sedimentological research. Nevertheless, the specific proximity range of erosional areas in rift basins and whether this range varies with rift evolution remain ambiguous. Based on the identification of depositional systems and progradational bodies in three-dimensional seismic data, five sequences (T85–T72) from the steep slope zone of the Lufeng Sag were selected for source-to-sink system analysis. The results indicate that during the deposition of the upper Wenchang Formation (intense rifting phase), intense fault activity controlled the development of longitudinal drainage systems and watersheds through the differential reactivation of faults in the steep slope zone. High fault activity rates led to the rapid uplift of the footwall, giving rise to extensive fault triangular facets and small rounded watershed morphologies. During the deposition of the lower Wenchang Formation (minor rifting stage), the merging of multiple small channels resulted in a reduction in the number of channels, an extension of channel distances, and an increase in individual depositional areas. During the deposition of the Lower Enping Member (late rifting stage), the northward migration of slope-controlling faults decoupled shorelines from structural control. Further channel amalgamation formed large-scale oblique drainage systems (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Source-to-sink systems evolution of the steep slope zone in the Lufeng Sag during Eocene stratigraphic intervals (T85–T72): (A) Wen-6&5th Member and (B) Wen-4th Member: Fault activity was intense, dominated by longitudinal drainage systems with numerous short-distance channels and limited single depositional areas; (C) Wen-3rd Member and (D) Wen-2&1st Member: Fault activity decreased, with channel confluence reducing channel count while extending their lengths, resulting in expanded single depositional areas and shrinkage of lacustrine basin extent; (E) En-4th Member and (F) En-3rd Member: Northward migration of basin-controlling faults induced further channel confluence, forming large-scale oblique drainage systems. The blue lines represent paleo-drainage channels, and the areas within the red dotted lines are the source area. F is the fan delta, B is the braided river delta, W is the Wenchang Formation, and E is the Enping Formation.

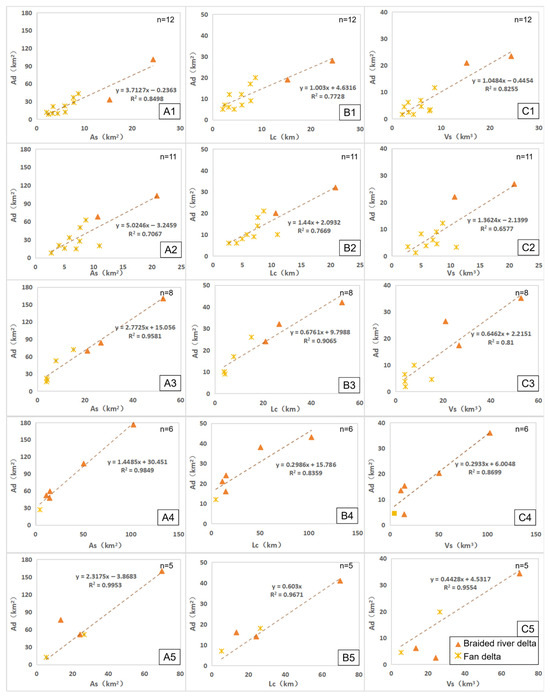

4.2. Quantitative Analysis of Source-to-Sink Systems in the Steep Slope Zone

To investigate the tectono-sedimentary coupling mechanisms and sandstone distribution patterns in the steep slope zone of the Lufeng Sag, comprehensive quantitative analyses were conducted on 72 identified fan bodies within five third-order sequences (T85-T72) (Due to the difficulty in distinguishing the boundaries of some fan bodies, adjacent bodies were recorded as a single data point, resulting in a total of 42 data). During the intense rifting phase of the Wenchang Formation, fan deltas predominantly developed, whereas braided river deltas were concentrated along the eastern slope zone and the middle transfer zone. The Enping Formation (from the rifting stage transition to the sag stage) witnessed large-scale braided river delta deposition. By employing the Adobe Photoshop Quantification (PSQ) method, the source area (As), sink area (Ad), channel distance (Lc), and channel cross-sectional areas were determined from 3D seismic data. Statistical comparisons among sequences indicated strong positive correlations (R2 ≥ 0.65) between the source area, channel distance, and the product of channel cross-sectional area and length (Vs) and the depositional area (Figure 6), demonstrating first-order controls of paleodrainage basin scale on sand bodies development in steep slope zones, with structural belts containing larger paleo-catchment area exhibiting higher reservoir potential.

Figure 6.

Quantitative coupling relationships of the source-to-sink system across Eocene stratigraphic intervals in the steep slope zone of the Lufeng Sag: (A1–A5) sequentially represent the relationships between source area (As) and sink area (Ad) in Wen-6&5th Member, Wen-4th Member, Wen-3rd Member, Wen-2&1st Member, and En-4th Member; (B1–B5) sequentially represent the relationships between channel distance (Lc) and sink area(Ad) in Wen-6&5th Member, Wen-4th Member, Wen-3rd Member, Wen-2&1st Member, and En-4th Member; (C1–C5) sequentially represent the relationships between the product of channel cross-sectional area and length (Vs) and sink area (Ad) in Wen-6&5th Member, Wen-4th Member, Wen-3rd Member, Wen-2&1st Member, and En-4th Member. Ad: sink area, As: source area, Lc: channel distance, Vs: the product of channel cross-sectional area and length, n: number of data.

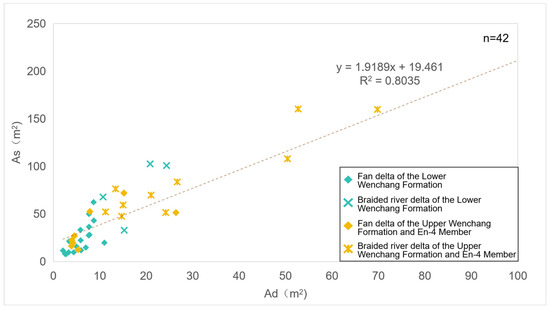

Based on a comprehensive analysis of 72 sand bodies and catchment areas across Eocene stratigraphic intervals in the Lufeng Sag, we observed that the depositional areas and denudation areas in the upper Wenchang Member and En-4th Member are generally larger than those in the lower Wenchang Formation. This disparity stems from two primary factors: (1) Intense fault activity during the early rifting stage constrained the development of longitudinal drainage systems and restricted the spatial distribution of fan bodies, resulting in smaller depositional areas in the lower Wenchang Formation compared to the later intervals. (2) Sedimentary facies differentiation—fan deltas dominate the lower Wenchang Formation, whereas braided river deltas (characterized by significantly greater areal extent) prevail in the upper Wenchang Formation and En-4th Member. To elucidate the quantitative source-to-sink development patterns specific to the fan deltas of the lower Wenchang Formation, targeted investigation of these distinct depositional systems is required (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Quantitative coupling relationship of source and sink areas in the Eocene steep slope zone of the Lufeng Sag (Sequences T85–T72), Ad: sink area, As: source area, n: number of data.

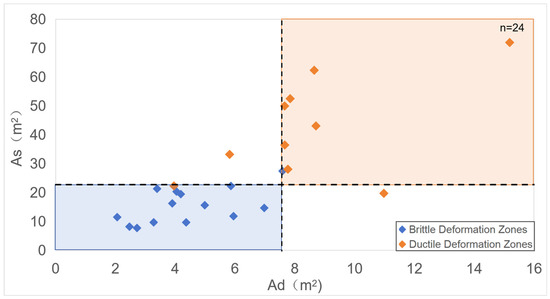

Taking into account the scale disparities between fan delta and braided river delta deposits, along with the influence of northward fault migration on sand body dimensions, specialized investigations were carried out on the fan deltas of the lower Wenchang Formation and their corresponding depositional and denudation areas. Based on the thermo-tectonic zoning framework established in prior studies for the Lufeng Sag, comparative analyses were conducted to differentiate the fan bodies in brittle deformation zones from those in ductile deformation zones. The results indicate that the ductile deformation zones (e.g., LFX area), situated within the paleo-tectonic transition zones of the lower Wenchang Formation, generally developed larger-scale drainage systems in comparison to the longitudinal drainage networks in intense rifting areas. Consequently, both the denudation areas and depositional areas in the ductile deformation zones of the steep slope belt are significantly larger than those in brittle deformation zones (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Comparison of source and sink areas in brittle vs. ductile deformation zones of the Lower Wenchang Formation in the steep slope zone of the Lufeng Sag, Ad: sink area, As: source area, n: number of data.

5. Discussion

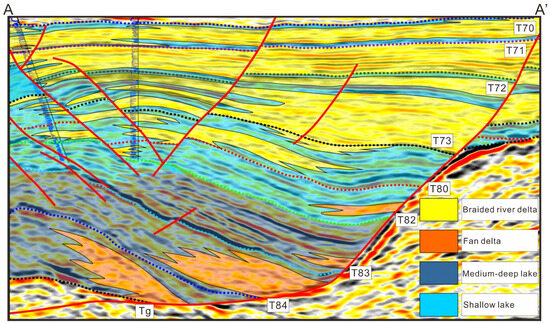

5.1. Characteristics of Sand Body Development in the Steep Slope Zone of Ductile Deformation Zone

The integration of paleogeomorphic reconstruction and source-to-sink quantitative analysis in the Lufeng Sag steep slope zone reveals a systematic coupling between tectonic evolution and sand body development. Ductile deformation zones consistently exhibit significantly larger sand body development features compared to brittle zones, primarily due to their capacity to maintain continuous sediment pathways under frequent tectonic adjustments. However, the specific influence of geothermal mechanisms on sand body distribution and migration within ductile deformation zones remains an underexplored factor. The structural classification of deformation zones proposed by Walsh and Watterson (1991) provides a foundational framework for interpreting these observations [12,14]. According to their model, ductile deformation zones are characterized by “soft-linked” fault connectivity, where faults are not fully connected but interact through distributed strain. This mechanism leads to the formation of accommodation zones or transfer slopes, which play a pivotal role in modulating the spatial distribution of drainage basins and the migration of drainage systems. Such structural adjustments directly govern sediment dispersal patterns and the scale of sand body systems in the steep slope zone. Notably, the LFX area represents a classic ductile deformation zone within the eastern Lufeng Sag, marked by high geothermal gradients. This aligns with the theoretical framework of soft-linked fault systems, further emphasizing the tectono-thermal coupling effects in shaping the sand body development evolution.

During the intense rifting stage, the study area experienced vigorous tectonic activity, resulting in the source-to-sink system being jointly controlled by pre-existing drainage networks and inherited paleotopography. In intra-sag regions, isolated small-scale proximal fan delta clastic deposits dominated due to the restricted influence of active tectonic boundaries. In contrast, ductile deformation zones—characterized by higher geothermal gradients and a more stable structural framework—hosted potential large-scale drainage systems and substantial sand body development. This disparity highlights the critical role of ductile deformation in accommodating and transmitting sedimentary fluxes during periods of intense tectonic extension. In the minor rifting stage, fault activity across the steep slope belt exhibited a homogenization trend, with reduced tectonic intensity and a more uniform distribution of structural deformation. However, within ductile deformation zones, relatively enhanced fault reactivation occurred, driven by localized stress adjustments. This reactivation led to a sedimentary environment transition dominated by lacustrine mudstone facies, as the structural stability of ductile zones diminished, favoring the deposition of finer-grained sediments over coarser clastic systems. By the rift reactivation stage, large-scale structural transfer zones and drainage systems were re-established in ductile deformation zones, acting as critical conduits for sediment delivery. These systems facilitated the development of deltaic complexes, ultimately restoring sand-rich characteristics in depositional areas (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Sand-rich depositional model of steep slope zone with typical ductile deformation characteristics in the LFX area of the eastern Lufeng Sag; the location of the seismic profile (A–A’) is shown in Figure 1.

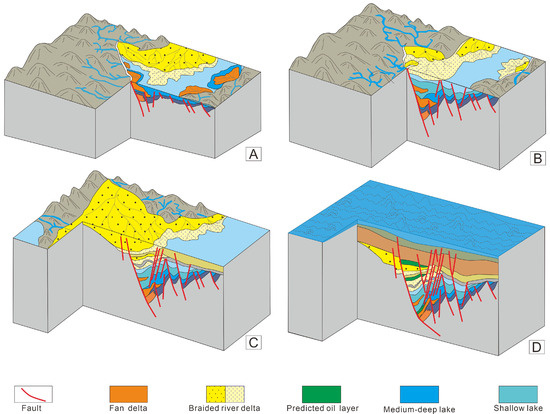

5.2. Hydrocarbon Accumulation Model in the Steep Slope Zone of Ductile Deformation Zone

The integration of paleogeomorphic reconstruction and quantitative source-to-sink system analysis has revealed crucial hydrocarbon accumulation advantages in the steep slope zones of ductile deformation belts within rift basins. These advantages are rooted in the dynamic coupling between tectonic evolution, sedimentological processes, and geothermal conditions. These advantages are rooted in the dynamic coupling between tectonic evolution, sedimentological processes, and geothermal conditions. During the intense rifting stage, ductile deformation zones, characterized by their structural resilience and capacity to sustain distributed strain, facilitated the formation of large-scale sand bodies. These sand bodies directly interfaced with lacustrine source rocks, establishing efficient and uninterrupted hydrocarbon migration pathways. Concurrently, the elevated geothermal gradients in ductile zones accelerated the thermal maturation of organic-rich lacustrine source rocks, providing essential geothermal driving forces for hydrocarbon generation (Figure 10A).

Figure 10.

Three-dimensional model of advantageous hydrocarbon accumulation of the steep slope zone in the ductile deformation area: (A) intense rifting stage; (B) minor rifting stage; (C) the rift-sag transition stage; (D) the sag stage.

In the subsequent stages of tectonic evolution, the interplay between structural adjustments and sedimentological responses further optimized the hydrocarbon accumulation framework. In the early minor rifting stage, fault activity in ductile zones remains relatively stable, whereas significant attenuation occurs in brittle zones. This leads to the reorganization of the stress field, which promotes the deposition of deep lacustrine mudstone caprocks. These fine-grained, low-permeability mudstones act as effective seals, preventing upward hydrocarbon leakage and preserving the integrity of underlying reservoirs (Figure 10B). As the late minor rifting stage advances, the continuous weakening of fault activity facilitates the widespread development of braided river delta systems, giving rise to large-scale contiguous reservoirs. These reservoirs are particularly advantageous for hydrocarbon accumulation due to their high permeability and ability to form multi-stage, stacked sand bodies that enhance reservoir thickness and continuity (Figure 10B). During the rift-sag transition period, the sediment source shifts from proximal to distal, resulting in multi-stage stacked braided river delta sand bodies with extensive spatial distribution (Figure 10C). Finally, in the sag stage, the basin undergoes a transition from lacustrine to marine sedimentation, where regional transgressive deposits offer effective seals for reservoir preservation (Figure 10D). Collectively, these structural-sedimentary advantages, combined with the geothermal-driven maturation of source rocks, create a highly favorable hydrocarbon accumulation framework in ductile deformation zones. This framework not only highlights the importance of tectonic zonation in reservoir prediction but also underscores the necessity of incorporating geothermal and sedimentological dynamics into exploration strategies for fault basins.

6. Conclusions

By integrating paleogeomorphic reconstruction with quantitative source-to-sink analysis, this study highlights the dominant role of the tectonic–geothermal coupling effects on the evolution of the paleogeomorphology and source-to-sink system. Ductile deformation zones, characterized by high geothermal gradients and soft-linked fault structures, regulate stress distribution and drainage reorganization across different tectonic stages, providing efficient sediment transport pathways that facilitate the development of large-scale, multi-phase stacked sand bodies.

- (1)

- During intense rifting phases, erosion and deposition areas in steep slope zones are limited, dominated by isolated small-scale proximal fan-delta clastic deposits. In contrast, ductile deformation zones exhibit more stable structural frameworks and soft-linked faults, supporting larger drainage systems and extensive sand body development, significantly surpassing those in brittle deformation zones. These sand bodies directly contact lacustrine source rocks in adjacent brittle zones, establishing efficient and continuous pathways for primary hydrocarbon migration.

- (2)

- In weak rifting phases, fault activity in ductile zones remains relatively stable, while brittle zones experience notable fault attenuation. This stress field reorganization promotes the deposition of deep-lake mudstones, which act as effective seals due to their fine-grained, low-permeability properties, preventing upward hydrocarbon leakage. As weak rifting progresses, reduced fault activity favors the widespread development of braided river delta systems, forming large-scale contiguous reservoirs. High permeability and multi-stage sand stacking enhance reservoir thickness and continuity.

- (3)

- During late rifting stages, large-scale structural transfer zones and drainage systems are re-established in ductile deformation zones, serving as critical sediment transport conduits. Sediment sources shift from proximal to distal areas, forming spatially extensive, multi-phase stacked braided river delta sand bodies. In the sag stage, the basin transitions from lacustrine to marine deposition, with regional transgressive sediments providing effective seals for reservoir preservation.

- (4)

- Through a detailed analysis of the source-to-sink system evolution in the Lufeng Sag, the sand body distribution and hydrocarbon accumulation patterns within ductile deformation zones controlled by tectono-geothermal mechanisms have been delineated. However, due to the limited spatial scope of the study area, the results may possess certain constraints. Future research conducted within a broader tectonic context would significantly enhance the understanding of hydrocarbon exploration potential in steep slope zones of fault basins.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z. and K.Z.; methodology, L.B. and S.Z.; software, L.B. and X.H.; validation, L.B. and Z.Z.; investigation, X.H.; resources, X.H.; data curation, L.B. and S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.B.; writing—review and editing, W.Z. and K.Z.; visualization, L.B. and Z.Z.; supervision, W.Z. and K.Z.; project administration, X.H. and K.Z.; funding acquisition, K.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the scientific research project from CNOOC (China) Limited Shenzhen Branch (Grant No.CCL2023SZPS0055) and by the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (Grant No.2025ZD1402701-01).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the insightful comments and constructive suggestions provided by the editor and anonymous reviewers regarding our manuscript. We are also deeply indebted to the experts from the Lufeng Exploration Department of CNOOC Shenzhen Branch for their professional guidance during the research process. In particular, we extend our heartfelt thanks to Cai Guofu for his invaluable and selfless instruction in mastering the practical application of relevant software, which has significantly enhanced the technical rigor and efficiency of our study.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xin Huang was employed by the Shenzhen Branch of CNOOC China Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from the Shenzhen Branch of CNOOC China Limited. The funder was not involved in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of this article; or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Mann, P.; Horn, M.; Cross, I. Emerging trends from 69 giant oil and gas fields discovered from 2000–2006. Present. April. 2007, 2, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Qu, H.; Chen, G.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, F.; Yang, H.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, M. Giant discoveries of oil and gas fields in global deepwaters in the past 40 years and the prospect of exploration. J. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2019, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, D.; Li, H.; Chang, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, Q. Differential Genetic Mechanisms of Deep High-Quality Reservoirs in the Paleogene Wenchang Formation in the Zhu-1 Depression, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Energies 2022, 15, 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Shu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Que, X.; She, Q.; Wang, Y. Geological characteristics and forming conditions of large and medium oilfields in Lufeng Sag of Eastern Pearl River Mouth Basin. J. Cent. South Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2017, 48, 2979–2989, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Lin, H.; Que, X.; He, Y.; Jia, L.; Xiao, Z.; Li, M. Geological Structure Characteristics of Central Anticline Zone in Lufeng 13 Subsag, Pearl River Mouth Basin and Its Control Effect of Hydrocarbon Accumulation. Acta Pet. Sin. 2019, 40, 56–66, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Lin, H.; Wang, X.; Qiu, X.; Que, X.; Li, M.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y. Geochemical Constraints on the Sedimentary Environment of Wenchang Formation in Pearl River Mouth Basin and Its Paleoenvironmental Implications. Geoscience 2022, 36, 118–129, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Peng, G.; Pang, X.; Xu, Z.; Luo, J.; Yu, S.; Li, H.; Hu, T.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y. Characteristics of Paleogene Whole Petroleum System and Orderly Distribution of Oil and Gas Reservoirs in South Lufeng Depression, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Earth Sci. 2022, 47, 2494–2508, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Xu, S.; Cai, Y.; Ma, X. Wrench related faults and their control on the tectonics and Eocene sedimentation in the L13–L15 sub-sag area, Pearl River Mouth basin, China. Mar. Geophys. Res. 2018, 39, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Huang, S.; Guo, G.; Chen, K.; Wang, S.; Ke, L.; Hu, Y. Tectonic and sedimentary evolution of Paleogene and resource potential in Northwestern Lufeng 13 Sag, Pearl River Mouth basin. China Offshore Oil Gas 2023, 35, 13–22, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C.; Zhou, J.; Wu, J.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, H.; Yin, B.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation of tight sandstone mechanical properties and fracability: An experimental study of reservoir sand− stones from Lufeng Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin, Northern South China Sea. Processes 2023, 11, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Densmore, A.; Gupta, S.; Allen, P.; Dawers, N. Transient landscapes at fault tips. J. Ofgeophysical Res. Earth Surf. 2007, 112, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.J.; Watterson, J. Geometric and kinematic coherence and scale effects in normal faultsystems. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1991, 56, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, P.H. Relay structures in a Lower Permian basement-involved extension system, EastGreenland. J. Struct. Geol. 1988, 10, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, D.C.P.; Sanderson, D.J. Geometry and development of relay ramps in normal faultsystems. AAPG Bull. 1994, 78, 147–165. [Google Scholar]

- Commins, D.; Gupta, S.; Cartwright, J. Deformed streams reveal growth and linkage of a normalfault array in the Canyonlands graben, Utah. Geology 2005, 33, 645–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, K.; Xiao, Z.; Zhu, W.; Huang, X.; Bian, L.; Wu, Q.; Feng, K. Tectnonic migration of prototype basins in Northwest Sub-sag of Lufeng Sag, the Pearl River Mouth Basin. Mar. Geol. Quat. Geol. 2025, 45, 168–177, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, K.; Li, H.; Liu, S.; Xiao, Z.; Bian, L.; Wu, D.; Feng, K. Prototype Basin Types and Segmental Differential Evolution of LF13 Subsag in the Pearl River Mouth Basin. China Offshore Oil Gas 2024, 36, 60–69, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Pierce, I.K.D.; Ai, M.; Luo, Q.; Li, C.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, P. Active tectonics and landform evolution in the Longxian-Baoji Fault Zone, Northeast Tibet, China, determined using combined ridge and stream profiles. Geomorphology 2022, 410, 108279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, X.; Yang, D. Source-to-sink analysis of a transtensional rift basin from syn-rift to uplift stages. J. Sediment. Res. 2019, 89, 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Cui, H.; Wu, P.; Sun, H. New development and outlook for oil and gas exploration in passive continental margin basins. Acta Pet. Sin. 2017, 38, 1099–1109, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, P.; Wang, W. Controlling Effect of Tectonic Transformation in Paleogene Wenchang Formation on Oil and Gas Accumulation in Zhu I Depression. Earth Sci. 2021, 46, 1797–1813, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y.; Niu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, X. Differences of hydrocarbon enrichment regularities and their main controlling factors between Paleogene and Neogene in Lufeng Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2019, 40, 41–52, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Zhang, X.; Lei, Y.; Qiu, X.; Yang, Y. Tectonic characteristics of Lufeng North area and the exploration direction of the Enping Formation. China Offshore Oil Gas 2020, 32, 44–53, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Fu, X.; Fan, M.; Wang, S.; Meng, L.; Du, W. Fault growth and linkage: Implications for trap integrity in the Qi’nan area of the Huanghua Depression in Bohai Bay Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2022, 145, 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Chen, D.; Chang, X.; Shu, L.; Wang, F. Controlling effect of tectonic-paleogeomorphology on deposition in the south of Lufeng sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2022, 6, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pang, X.; Pang, H.; Huo, X.; Ma, K.; Huang, S. Hydrocarbon accumulation model based on threshold combination control and favorable zone prediction for the lower Enping Formation, Southern Lufeng sag. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2022, 6, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Ma, K.; Huo, X.; Huang, S.; Wu, S.; Zhang, X. Crude Oil Source and Accumulation Models for the Wenchang Formation, Southern Lufeng Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin, (Offshore) China. Minerals 2023, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, G.; Chen, Y.; Hao, F.; Yang, X.; Hu, F.; Zhou, L.; Yi, Y.; Yang, G.; Wang, X.; et al. Formation and preservation of ultra-deep high-quality dolomite reservoirs under the coupling of sedimentation and diagenesis in the central Tarim Basin, NW China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2022, 149, 106084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, A.; Reemst, P.; Henstra, G.; Gozzard, S.; Ray, A. Rifting of the South China Sea: New perspectives. Pet. Geosci. 2010, 16, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Xia, B.; Lin, G.; Liu, B.; Yan, P.; Li, Z. The sedimentary and tectonic evolution of the basins in the north margin of the South China Sea and geodynamic setting. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2005, 25, 53. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Suo, Y.; Liu, X.; Dai, L.; Yu, S.; Zhao, S.; Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Cheng, S.; An, H. Basin dynamics and basin groups of the South China Sea. Mar. Geol. Quat. Geol. 2013, 32, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Shi, H.; Zhu, M.; Pang, X.; He, M.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, F. A discussion on the tectonic-stratigraphic framework and its origin mechanism in Pearl River Mouth Basin. China Offshore Oil Gas 2014, 26, 20–29, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhi, Z. Cenozoic faults characteristics and regional dynamic background of Panyu 4 sub-sag, Zhu I Depression. J. China Univ. Pet. 2015, 39, 1–9, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhong, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yu, W.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S. Characterization and genesis of the middle and late Eocene tectonic changes in Zhu 1 depression of Pearl River Mouth basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2016, 37, 779–785, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Peng, G.; Yu, Y.; Qiu, X.; Xiao, Z.; He, Y.; Lu, M.; Zhang, J. Fault growth and linkage in multiphase extension settings: A case from the Lufeng Sag, Pearl River Mouth Basin, South China Sea. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2023, 257, 105856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, T.R.; Anderson, N.L.; Franseen, E.K. Paleogeomorphology of the upper Arbuckle karst surface—Implications for reservoir and trap development in Kansas (abs.): American Association of Petroleum Geologists. Annu. Conv. Off. Program 1994, 3, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Troutman, T.J. ABSTRACT: Reservoir Characterization, Paleoenvironment, and Paleogeomorphology of the Mississippian Redwall Limestone Paleokarst, Hualapai Indian Reservation, Grand Canyon Area, Arizona. AAPG Bull. 2000, 84. [Google Scholar]

- House, M.A.; Wernicke, B.P.; Farley, K.A. Paleo-geomorphology of the Sierra Nevada, California, from (U-Th)/He ages in apatite. Am. J. Sci. 2001, 301, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breckenridge, R.M.; Othberg, K.L.; Bush, J.H. Stratigraphy and paleogeomorphology of Columbia River Basalt, eastern margin of the Columbia River plateau. Geol. Soc. Am. 1997, 29, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Z.; Wang, J. A method of paleogeomorphology restoration based on tectonic &sedimentary modeling: A case study from QHD29-2E area of Bohai Bay Basin, NE China. In Proceedings of the SEG International Exposition and Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–23 October 2015; SEG-2015-5854112. SEG: Houston, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Z.; Zhang, X.; Bian, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, T. Exploration Discoveries of Elusive Reservoirs Using Detailed Paleogeomorphology Reconstructions. J. Southwest Pet. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 40, 12–22, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto, S. Modal analysis of granitic rocks by a personal computer using image processing software “Adobe photoshopTM”. J. Mineral. Petrol. Econ. Geol. 1996, 91, 235–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, K.; Wu, S. Adobe photoshop quantification (PSQ) rather than point-counting: A rapid and precise method for quantifying rock textural data and porosities. Comput. Geosci. 2014, 69, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, L.; Liu, X.; Wu, N.; Wang, J.; Liang, Y.; Ni, X. Identification of High-Quality Transverse Transport Layer Based on Adobe Photoshop Quantification (PSQ) of Reservoir Bitumen: A Case Study of the Lower Cambrian in Bachu-Keping Area, Tarim Basin, China. Energies 2022, 15, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G. Interaction of rivers and oceans—Pleistocene petroleum potential. AAPG Bull. 1969, 53, 2421–2430. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, E.; Julian, M. Source-to-sink sediment transfers, environmental engineering and hazard mitigation in the steep Var River catchment, French Riviera, southeastern France. Geomorphology 1999, 31, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sømme, T.; Jackson, C.; Vaksdal, M. Source-to-sink analysis of ancient sedimentary systems using a subsurface case study from the Møre-Trøndelag area of southern Norway: Part 1–Depositional setting and fan evolution. Basin Res. 2013, 25, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sømme, T.; Jackson, C. Source-to-sink analysis of ancient sedimentary systems using a subsurface case study from the Møre-Trøndelag area of southern Norway: Part 2–sediment dispersal and forcing mechanisms. Basin Res. 2013, 25, 512–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sømme, T.; Hellan-Hansen, W.; Martinsen, O.; Thurmond, J. Relationships between morphological and sedimentological parameters in source-to-sink systems: A basis for predicting semi-quantitative characteristics in subsurface systems. Basin Res. 2009, 21, 361–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Yang, H.; Liu, J.; Peng, L.; Cai, Z.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y. Paleostructural geomorphology of the Paleozoic central uplift belt and its constraint on the development of depositional facies in the Tarim Basin. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 2009, 52, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Yang, H.; Liu, J.; Rui, Z.; Cai, Z.; Zhu, Y. Distribution and erosion of the Paleozoic tectonic unconformities in the Tarim Basin, Northwest China: Significance for the evolution of paleo-uplifts and tectonic geography during deformation. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 46, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Xia, Q.; Shi, H.; Zhou, X. Geomorphological evolution, source to sink system and basin analysis. Earth Sci. Front. 2015, 22, 9, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Zhu, X.; Xie, S.; Yang, K.; Zhang, M.; Qin, Y. Restoration methods of sedimentary paleogeomorphology and applications: A case study of the first member of Paleogene Shahejie Formation in Raoyang Sag. J. Palaeogeogr. (Chin. Ed.) 2023, 25, 1139–1155, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Guo, Q.; Wang, H. Source-to-Sink Comparative Study between Gas Reservoirs of the Ledong Submarine Channel and the Dongfang Submarine Fan in the Yinggehai Basin, South China Sea. Energies 2022, 15, 4298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wang, H.; Jiang, T.; Liu, E.; Chen, S.; Jiang, P. Sedimentary Characteristics of Lacustrine Beach-Bars and Their Formation in the Paleogene Weixinan Sag of Beibuwan Basin, Northern South China Sea. Energies 2022, 15, 3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.